Etymological Meaning of Education

The word education is derived from the Latin word “educare” which means to bring up. Another Latin word “educere”, means to bring forth. Therefore education to bring forth as well as bring up. According to Varro “Educit obstertrix, educate, nutrix, institute, pedagogues, docet, magister” i.e. “the mid-wife brings forth, the nurse brings up, the tutor trains, and the master teaches”. Accordingly education does not mean only the acquisition of knowledge but it is the development of attitudes and skills.

Some theorists give a different explanation of the word “educate”. They say ‘e’ means out of and duco means to lead’ i.e. to educate means to lead forth or “to extract out” the best in man. This explanation presumes that all knowledge is inherent in children. Only methods are to be found out to tap their brains and the knowledge will automatically flow. Addison supports this view believing that education, “when it works upon a noble mind draws out to view every latent virtue and perfection”. We also support this theory, I mean an all round sketch of the best in the child and man — body, mind and spirit”. These two views of education can be accepted with a pinch of salt. We cannot ‘draw out’ anything unless we put in something before. The child is not like an artesian well, where we put a funnel and water will gush out. He is like a bank, where something must be put before, we expect to draw out. It may be that once or twice a bright and quick child may give a promise of talents, but is not always true. “Unless knowledge and experience is given to the child we cannot draw out the best in him.”

Historically, Philosophers have, from ancient times, given their views on education. Socrates (470-399 B.C.) was one of the first to do so. Socrates preferred to describe education by comparing it with his mother’s profession. Education is Midwifery. A teacher, like a midwife, only helps the mother to give birth. The teacher is not the mother. So also, the pupil himself “conceives” the idea, (Called concept”) and the teacher only helps.

But a teacher is not like a Sculptor, who carves out a block of stone entirely by himself, leaving the stone passive. The student is not passive, like a stone, so teacher cannot be compared to a sculptor.

This idea was repeated by Aquinas (1225-1274 A.D.) who, in reply to famous question: ‘Can one man teach another?” answered: yes, provided that the student goes through a process of thought which is similar (analogical) to that of his teacher.

Other thinkers are divided over the problem of whether the mind contains “Innate ideas” which the teacher must help to bring out, or whether the mind is a blank Slate (“Tabula Rasa”) upon which the teacher writes, while the student remains passive. Or, in other words (as Socrates would say) whether a Teacher is a Midwife or a Sculptor.

The truth is in the middle: there must be, in Education, an internal element (Mind) and an external element (data form the senses) and both play an indispensable part in education.

Seen in Latin as educatio, linked to the use of the verb ‘to educate’ as educāre, to express a principle of directing or guiding, associated with educĕre, interpreted as ‘revealing’ or ‘exposing’ to the outside, composed of the prefix ex-, indicating ‘to take out’ or ‘to externalize’, and ducĕre, for the action of ‘to conduce’ (in Latin conducĕre, governed by the prefix con-, in terms of union or totality), evidencing reference in the Indo-European *deuk-, for ‘to lead’, carrying or guiding, whose influence is manifested in duke (from the French duc, in reference to the Latin forms dux, ducis), to produce (over the Latin in producĕre) or even in seduce (defined by the Latin seducĕre). A clear idea is expressed: to promote the intellectual and cultural development of the individual and, at the same time, to encourage the learning of new concepts and skills.

As a general rule, all educational processes are carried out by a professional educator, as described in the Latin educātor. This person is responsible for instilling knowledge and skills in schools. The other essential way of learning is based on being self-taught, or an autodidact, a term found in the French autodidacte from the Greek origin word autodídaktos.

In the ancient world, there were no schools as we know them today. In the case of Athens, there were spaces for reflection and debate (for example, Plato’s Academy or Aristotle’s Lyceum).

In the Sparta Polis children received an education with a strong military style, since discipline was hard and behavior was molded through physical exercise

In Roman civilization there was an educational model based on the trivium (it included rhetorical, grammatical and dialectical knowledge) and the quadrivium (music, astronomy, arithmetic and geometry). It was in this historical period that the teacher-student relationship was consolidated, but only for the privileged sector of society (the common people were on the margins of education and the social elites were educated in a balancing knowledge, art and physical exercise).

During the Middle Ages the only cultural centers were linked to the church (in the monasteries there were libraries and in them the scribes copied the different texts). During the Middle Ages the first universities appeared in cities such as Bologna, Paris, Oxford or Salamanca, as well as the first municipal schools to care for orphaned children (for example, in the city of Valencia in 1410 the Imperial College of Orphaned Children of San Vicente Ferrer was founded).

It was from the period of the Enlightenment in the 18th century when the first public education centers appeared, free and mandatory for the entire young population. The European absolute monarchs promoted the first public schools to educate the people (for example, the Prussian school followed the Spartan model and encouraged discipline and authoritarian regime in order to make the population docile and easily manipulated).

Schools as state-regulated educational institutions developed throughout the nineteenth century along with the expansion of capitalism.

We might as well start at the beginning. What is this whole thing that we call “Education” – especially today?

The word Education has two Latin roots: Educere & Educare:

Educere means to draw out, to lead forth

Educare means to nourish, to bring up

These two roots, and therefore the understandings of the word “Education” are at the root of the divide between those who think education is all about doing something to/for the student (i.e. someone has to draw the thing that is inside of the student out), or if it is something the student does themselves (in the right nourishing environment – like a plant). The battle, one might say, between teaching and learning, who is responsible for that teaching or learning, and how both happen.

The scholar who converted me to the idea that throughout our schooling in fact we learn, rather than that we are taught, per se, is the French Philosopher Jacques Rancière, in his book: The Ignorant Schoolmaster (a web search should deliver a PDF). It tells of a well-regarded French-speaking Professor, Joseph Jacotot who finds his courses in high demand by some Flemish speaking local students, but having no way to “teach” them since he knew no Flemish. Their conundrum was solved when Jacotot chanced upon a bilingual magazine, which he then instructed the Flemish speaking students to use to learn French by comparing the translations in this magazine.

To his amazement, after some months of somehow teaching themselves French they were able to write essays about on the academic texts he assigned them in French, and quite respectable French too. He had expected ” horrendous barbarisms” but instead the students, without any explanations made about this language that many would agree is fairly complicated, had managed to “understand and resolve the difficulties of the language” on their own.

In brief, Rancière brings the whole notion of “Schooling”, in which the teacher knows and the student does not, and in which the teacher therefore has to explain things to the student in order for her or him to understand, into question. It also brings into question the fact that everything that the student has to learn can be precisely and conclusively laid out in a curriculum, in a specific order, so that the student can avoid wasting time on non-essential knowledge or trying to learn things in the wrong order. He had not, after all, had to explain French grammar or conjugation to these Flemish speakers; he had not guided them on what to learn first and what to learn next; they had not passed a series of tests along the way; no. Instead, they appear only to have been driven by their own will, and in the end by necessity. Was it possible, then, that we were all capable of learning anything if only we were compelled by circumstances to learn?

He gives the example of the way in which children the world over learn their mother tongue; from Chinese to Lugbara to Silbo (one of a handful of whistling languages that are still in use), no one has to explain anything – they hear, they imitate, they make mistakes and self-correct, and they learn. As soon as they enter school, however, this ability to learn is suddenly assumed to vanish, and now everything has to be explained to them and they should learn by filling in the missing … and whatnot. Looking at all this Rancière arrives at a startling realisation:

The idea of Schooling is based on the assumption that the students are incapable of understanding without someone else explaining things to them – the belief that this incapacity exists sustains the practice of explaining things, even when there is no proof that this incapacity exists. As soon as it becomes clear that a child can in fact learn even without a teacher to explain things to them the explainer realises that they are not as central to the learning process as they thought. At that moment it becomes clear that it is in fact the explainer who needs the incapable for him or her to exist; the incapable does not always need the explainer.

Looking back on my own schooling, and perhaps readers will relate, it occurred to me that most of what I learnt I learnt on my own. Or rather, that even though a teacher may have introduced and explained certain concepts to me, learning only took place when I engaged my own mind and will to learn what s/he was trying to teach. If that teacher had not been there, and given that I had access to the books containing that information, the only necessary ingredient to my learning would have been my own will to put in the time to learn. This is NOT to say that the teacher is not necessary – they still have a role to play in facilitating or organising the learning; it is only to say that s/he is not as central to learning as they have come to be thought to be.

While we are on the subject, can we say that those who have never been in a school are really “uneducated”? After all they run successful businesses and can spot a good deal a lot better than the so-called educated. And what about those who dropped out of school but went on to teach themselves new skills, including supposedly complicated skills like programming – no teacher was involved – only necessity and the will to learn.

But moving on from them and back to us the educated (who I assume are the majority of those reading this): did we not continue to learn after we left school? Don’t we call that education as well? Or if we look at the process we undergo when we have to break in a new smartphone: by trial and error, asking, reading, discovery, past experience, we soon crack the phone. And this ability is not unique to us the educated – even the completely illiterate can figure out how to use a smart phone through a similar process.

What is my point?

My point is that our current schooling system, rooted as it is in the idea of Educere, has lost part of its meaning. Educere leads us to believe that something has to be done to or for the child in order for Education to occur, and ignores the fact that everyone has the innate ability to learn in response to the challenges their environment throws at them. Educare carries this sense by acknowledging and works with this innate ability, and is the way human beings learnt for millennia before the industrial revolution anyway. The Education system should really be more concerned with providing an environment in which this learning can be supported, rather than one in which it is dictated and policed.

I was completely aghast, for instance, when I heard an education expert recently say that the way to reform our education system was to introduce the teaching of creativity and curiosity at an early age – which is completely absurd, of course, because children – people in general – are naturally creative and curious – it is this being forced into the narrow tubing of schooling that convinces us that these are not desirable traits, and how we eventually abandon them.

The system of schooling that we have inherited served the dawn of industrialisation during which it was born very well: a steady supply of masses of human labour able to carry out repetitive tasks accurately, clerks to keep the accounts and write letters, and managers to ensure productivity and efficiency. In the present age these tasks have largely been mechanised, and instead humans are faced with addressing much more complex, evolving, and nuanced challenges: climate change; conflict; human rights abuses; (bad) governance; deepening inequality; and many other challenges that require collaborative and creative action, not simply a head full of facts and numbers.

One moment that stands out for me as I read Ranciere was observing myself learning all the different ways I could annotate the PDF I was reading; from highlighting only in yellow I graduated to highlighting in different colours; then I discovered I could insert notes; then I found out I could also underline text – and this could be a straight or a wiggly line; through necessity alone I learnt how to make more of reading a PDF, and I didn’t even to ask Mr. Google at any one time. For that matter I have never even attended a single school course on how to use a computer or MS word or send an email – all these I learnt through necessity, as many of us do.

All said and done: one might even argue that we have completely drifted away from the roots of the word itself. Our school system, and here I refer to the one in Uganda specifically, does not even try to draw out what is inside a child. We specify the precise form of what goes into the child, and then require them to give it right back as it is, and if they don’t they fail, drop out, and consider themselves failures henceforth.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a moment for us to look again at what this idea of education is about. What happens when the teacher and child cannot meet in a school? Does learning stop? Some say go online. But what about those without access? And even for those who have access, what is available online? Some say try homeschooling. But surely this is tantamount to saying “if they have no bread they should eat cake”? Without the necessary learning material, and given the differing capabilities of caretakers, besides that some would still have to attend to the business of making their living.

Next I will be looking more closely at the roots of the education system in many parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, and where these have gotten us today, before I dive into the interventions that are being explored by our government, as well as other players in the formal education space.

- Afrikaans: onderwys (af)

- Albanian: arsim (sq), edukim (sq) f

- Amharic: ትምህርት (təmhərt)

- Arabic: تَعْلِيم (ar) m (taʕlīm), تَرْبِيَة (ar) f (tarbiya)

- Aragonese: educación f

- Armenian: կրթություն (hy) (krtʿutʿyun), ուսում (hy) (usum)

- Aromanian: educatsie f

- Assamese: শিক্ষা (xikha)

- Asturian: educación f

- Azerbaijani: təhsil (az), tərbiyə (az), maarif, təlim (az)

- Bashkir: мәғариф (mäğarif)

- Basque: hezkuntza

- Belarusian: адука́цыя (be) f (adukácyja), асве́та f (asvjéta), асьве́та f (asʹvjéta), выхава́нне n (vyxavánnje), выхава́ньне n (vyxavánʹnje)

- Bengali: শিক্ষা (bn) (śikkha), তালিম (bn) (talim)

- Bokyi: kor n’ wed

- Breton: diorroadurez

- Bulgarian: образова́ние (bg) n (obrazovánie), възпита́ние (bg) n (vǎzpitánie)

- Burmese: ပညာ (my) (pa.nya), ပညာရေး (my) (pa.nyare:)

- Buryat: болбосорол (bolbosorol)

- Catalan: educació (ca) f

- Chechen: дешар (dešar)

- Cherokee: ᏗᏕᎶᏆᏍᏗ (dideloquasdi)

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 教育 (gaau3 juk6)

- Mandarin: 教育 (zh) (jiàoyù), 教學/教学 (zh) (jiàoxué), 教養/教养 (zh) (jiàoyǎng)

- Min Nan: 教育 (zh-min-nan) (kàu-io̍k)

- Wu: 教育 (jiau hhioq)

- Chuvash: вӗрентӳ (vĕrent̬ü)

- Cornish: adhyskans

- Corsican: please add this translation if you can

- Crimean Tatar: maarif, tasil

- Czech: vzdělávání (cs) n

- Danish: opdragelse (da) c, uddannelse c

- Dhivehi: please add this translation if you can

- Dutch: onderwijs (nl) n

- Esperanto: eduko (eo), edukado

- Estonian: haridus (et)

- Faroese: útbúgving f

- Finnish: kasvatus (fi), koulutus (fi), opetus (fi)

- French: éducation (fr) f, enseignement (fr)

- Friulian: please add this translation if you can

- Fula:

-

- Latin ekkitinol

- Adlam: 𞤫𞤳𞥆𞤭𞤼𞤭𞤲𞤮𞤤

- Galician: educación (gl) f

- Georgian: განათლება (ganatleba)

- German: Ausbildung (de) f, Erziehung (de) f, Schulung (de) f, Unterricht (de) m

- Greek: εκπαίδευση (el) f (ekpaídefsi)

- Ancient: παιδεία f (paideía)

- Gujarati: શિક્ષણ (śikṣaṇ), કેળવણી (keḷvaṇī)

- Hausa: please add this translation if you can

- Hawaiian: hoʻonaʻauao

- Hebrew: חִנּוּךְ חינוך (he) m (khinúkh)

- Hindi: शिक्षा (hi) f (śikṣā), तालीम (hi) f (tālīm)

- Hungarian: nevelés (hu), oktatás (hu)

- Icelandic: menntun f

- Ido: eduko (io), edukado (io)

- Igbo: mmuta

- Indonesian: pendidikan (id)

- Interlingua: please add this translation if you can

- Irish: oideachas (ga) m, léann m

- Italian: istruzione (it) f, educazione (it) f

- Japanese: 教育 (ja) (きょういく, kyōiku)

- Javanese: pawiatan

- Kalmyk: сурһуль (surğulĭ)

- Kannada: ಶಿಕ್ಷಣ (kn) (śikṣaṇa)

- Kazakh: оқу (kk) (oqu), ағарту (ağartu), білім беру (bılım beru)

- Khmer: ការសិក្សា (kaa səksaa)

- Kikuyu: gĩthomo class 7

- Korean: 교육(敎育) (ko) (gyoyuk)

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: پەروەردە (ckb) f (perwerde), زانیاری (zanyarî)

- Northern Kurdish: perwerde (ku) f

- Kyrgyz: билим берүү (bilim berüü), агартуу (ky) (agartuu), окутум (okutum)

- Lao: ການສຶກສາ (lo) (kān sưk sā)

- Latgalian: please add this translation if you can

- Latin: cultus (la) m, disciplina f

- Latvian: audzināšana f, izglītība f

- Lithuanian: auklėjimas m, ugdymas m, lavinimas m

- Luxembourgish: Erzéiung f, Educatioun f, Ausbildung f

- Macedonian: образование n (obrazovanie), воспитание n (vospitanie)

- Malay: pendidikan (ms), pelajaran

- Malayalam: വിദ്യാഭ്യാസം (ml) (vidyābhyāsaṃ)

- Maltese: edukazzjoni f

- Manx: edjaghys m

- Maori: akoranga matauranga, mātauranga (mi)

- Marathi: शिक्षण (śikṣaṇ)

- Mirandese: please add this translation if you can

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: боловсрол (mn) (bolovsrol), сурган хүмүүжил (surgan xümüüžil)

- Mongolian: ᠪᠣᠯᠪᠠᠰᠤᠷᠠᠯ (bolbasural), ᠰᠤᠷᠭᠠᠨ

ᠬᠦᠮᠦᠵᠢᠯ (surɣan kümüǰil)

- Navajo: íhooʼaah

- Nepali: शिक्षा (ne) (śikṣā)

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: utdannelse (no), utdanning (no) m or f, oppdragelse m

- Nynorsk: utdanning f, utdaning

- Occitan: educacion (oc) f

- Oriya: ଶିକ୍ଷା (or) (śikṣa)

- Pashto: زده کړه (ps) f (zdákṛa), تعليمات m pl (ta’limãt), تربيه (ps) f (tarbiyá), معارف m (ma’āréf)

- Persian: آموزش (fa) (âmuzeš), معرفت (fa) (ma’refat), تعلیم (fa) (ta’lim)

- Plautdietsch: Belia f

- Polish: edukacja (pl) f, oświata (pl) f, kształcenie (pl) n

- Portuguese: educação (pt) f, ensino (pt) m

- Punjabi: ਸਿੱਖਿਆ (pa) (sikkhiā)

- Rajasthani: please add this translation if you can

- Romanian: educație (ro) f, educare (ro) f

- Romansch: furmaziun f

- Russian: образова́ние (ru) n (obrazovánije), обуче́ние (ru) n (obučénije), воспита́ние (ru) n (vospitánije), просвеще́ние (ru) n (prosveščénije)

- Sanskrit: शिक्ष (sa) f (śikṣa), शिक्षा (sa) f (śikṣā)

- Scots: eddication

- Scottish Gaelic: foghlaim m, teagasg m

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: образова́ње n, васпи́та̄ње n, одгајивање n, про̏света f, про̏свјета f

- Roman: obrazovánje (sh) n, vaspítānje (sh) n, odgajivanje n, prȍsveta, prȍsvjeta (sh) f

- Sicilian: aducazzioni f

- Sindhi: تعليم (sd)

- Sinhalese: අධ්යාපනය (si) (adhyāpanaya)

- Slovak: vzdelávanie n

- Slovene: izobraževanje n

- Somali: please add this translation if you can

- Spanish: educación (es) f

- Swahili: elimu (sw)

- Swedish: utbildning (sv) c, undervisning (sv) c

- Tagalog: katuruan (tl), edukasyon (tl)

- Tajik: маориф (tg) (maorif), омузиш (omuziš), таълим (tg) (taʾlim)

- Tamil: கல்வி (ta) (kalvi)

- Tatar: мәгърифәт (tt) (mäğrifät)

- Telugu: విద్య (te) (vidya)

- Thai: การศึกษา (th) (gaan-sʉ̀k-sǎa)

- Tibetan: སློབ་གསོ (slob gso)

- Tigrinya: ትምህርቲ (təmhərti)

- Turkish: eğitim (tr)

- Turkmen: bilim (tk), magaryf, terbiýeleýiş

- Ukrainian: осві́та (uk) f (osvíta), вихова́ння (uk) n (vyxovánnja)

- Urdu: تعلیم (ur) (ta’līm), معرفت (ur) f (ma’rifat)

- Uyghur: مائارىپ (ma’arip), ئوقۇش (oqush)

- Uzbek: maorif (uz), tahsil (uz), maʻrifat

- Vietnamese: giáo dục (vi) (教育), dạy dỗ (vi), giáo dưỡng (vi) (教養)

- Vilamovian: aojsbildung

- Volapük: dugäl (vo), dugälav (vo) (pedagogy), benodugäl (vo), benodugälam (vo)

- Walloon: please add this translation if you can

- Welsh: addysg (cy) f

- West Frisian: ûnderwiis

- Yakut: үөрэҕирии (üöreğirii)

- Yiddish: בילדונג f (bildung), חינוך m or m (khinekh) (Jewish education)

- Zhuang: gyauyuz

Education Meaning of Education— The root of Word education is derived from Latin words Educare, Educere, and Educatum. Word educare means to nourish, to bring up. The word educere means to lead froth, to draw out. … Shiksha word derived from “Shah” meaning to “control or to discipline”.

Related Posts:

- What are some examples of demographic factors?

— The common variables that are gathered in… (Read More) - What are the 3 important goals of education?

— Chapter 1. The Real Goals of Educationbe… (Read More) - What is the main goal of education?

— “To us, the ultimate goal of education… (Read More) - What is the concept of education?

— Concepts of education are beliefs about what… (Read More) - What is the true definition of education?

— noun. the act or process of imparting… (Read More) - What is the best definition of education?

— 1a : the action or process of… (Read More) - What are the advantages of education?

— Those who get an education have higher… (Read More)

| Schools |

|---|

|

|

| Education |

| History of education |

| Pedagogy |

| Teaching |

| Homeschooling |

| Preschool education |

| Child care center |

| Kindergarten |

| Primary education |

| Elementary school |

| Secondary education |

| Middle school |

| Comprehensive school |

| Grammar school |

| Gymnasium |

| High school |

| Preparatory school |

| Public school |

| Tertiary education |

| College |

| Community college |

| Liberal arts college |

| University |

Education encompasses teaching and learning specific skills, and also something less tangible but more profound: the imparting of knowledge, positive judgment and well-developed wisdom. Education has as one of its fundamental aspects the imparting of culture from generation to generation (see socialization), yet it more refers to the formal process of teaching and learning found in the school environment.

Education means «to draw out,» facilitating the realization of self-potential and latent talents of an individual. It is an application of pedagogy, a body of theoretical and applied research relating to teaching and learning and draws on many disciplines such as psychology, philosophy, computer science, linguistics, neuroscience, sociology and anthropology.

Many theories of education have been developed, all with the goal of understanding how the young people of a society can acquire knowledge (learning), and how those who have knowledge and information that is of value to the rest of society can impart it to them (teaching). Fundamentally, though, education aims to nurture a young person’s growth into mature adulthood, allowing them to achieve mastery in whichever area they have interest and talent, so that they can fulfill their individual potential, relate to others in society as good citizens, and exercise creative and loving dominion over their environment.

Etymology

The word «education» has its roots in proto-Indian-European languages, in the word deuk. The word came into Latin in the two forms: educare, meaning «to nourish» or «to raise,» and educatus, which translates as education. In Middle English it was educaten, before changing into its current form.[1]

Education history

A depiction of the world’s oldest university, the University of Bologna, Italy

Education started as the natural response of early civilizations to the struggle of surviving and thriving as a culture. Adults trained the young of their society in the knowledge and skills they would need to master and eventually pass on. The evolution of culture, and human beings as a species depended on this practice of transmitting knowledge. In pre-literate societies this was achieved orally and through imitation. Story-telling continued from one generation to the next. Oral language developed into written symbols and letters. The depth and breadth of knowledge that could be preserved and passed soon increased exponentially. When cultures began to extend their knowledge beyond the basic skills of communicating, trading, gathering food, religious practices, and so forth, formal education, and schooling, eventually followed.

Many of the first educational systems were based in religious schooling. The nation of Israel in c. 1300 B.C.E., was one of the first to create a system of schooling with adoption of the Torah. In India, The Gurukul system of education supported traditional Hindu residential schools of learning; typically the teacher’s house or a monastery where the teacher imparted knowledge of Religion, Scriptures, Philosophy, Literature, Warfare, Statecraft, Medicine, Astrology, and History (the Sanskrit word «Itihaas» means History). Unlike in many regions of the world, education in China began not with organized religions, but based upon the reading of classical Chinese texts, which developed during Western Zhou period. This system of education was further developed by the early Chinese state, which depended upon literate, educated officials for operation of the empire, and an imperial examination system was established in the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E.-220) for evaluating and selecting officials. This merit-based system gave rise to schools that taught the classics and continued in use for 2,000 years.

Perhaps the most significant influence on the Western schooling system was Ancient Greece. Such thinkers as Socrates, Aristotle and Plato along with many others, introduced ideas such as rational thought, scientific inquiry, humanism and naturalism. Yet, like the rest of the world, religious institutions played a large factor as well. Modern systems of education in Europe derive their origins from the schools of medieval period. Most schools during this era were founded upon religious principles with the sole purpose of training the clergy. Many of the earliest universities, such as the University of Paris, founded in 1150 had a Christian basis. In addition to this, a number of secular universities existed, such as the University of Bologna, founded in 1088.

Education philosophy

John Locke’s seminal work Some Thoughts Concerning Education was written in 1693 and still reflects traditional education priorities

The philosophy of education is the study of the purpose, nature and ideal content of education. Related topics include knowledge itself, the nature of the knowing mind and the human subject, problems of authority, and the relationship between education and society. At least since Locke’s time, the philosophy of education has been linked to theories of developmental psychology and human development.

Fundamental purposes that have been proposed for education include:

- The enterprise of civil society depends on educating young people to become responsible, thoughtful and enterprising citizens. This is an intricate, challenging task requiring deep understanding of ethical principles, moral values, political theory, aesthetics, and economics, not to mention an understanding of who children are, in themselves and in society.

- Progress in every practical field depends on having capacities that schooling can educate. Education is thus a means to foster the individual’s, society’s, and even humanity’s future development and prosperity. Emphasis is often put on economic success in this regard.

- One’s individual development and the capacity to fulfill one’s own purposes can depend on an adequate preparation in childhood. Education can thus attempt to give a firm foundation for the achievement of personal fulfillment. The better the foundation that is built, the more successful the child will be. Simple basics in education can carry a child far.

A central tenet of education typically includes “the imparting of knowledge.” At a very basic level, this purpose ultimately deals with the nature, origin and scope of knowledge. The branch of philosophy that addresses these and related issues is known as epistemology. This area of study often focuses on analyzing the nature and variety of knowledge and how it relates to similar notions such as truth and belief.

While the term, knowledge, is often used to convey this general purpose of education, it can also be viewed as part of a continuum of knowing that ranges from very specific data to the highest levels. Seen in this light, the continuum may be thought to consist of a general hierarchy of overlapping levels of knowing. Students must be able to connect new information to a piece of old information to be better able to learn, understand, and retain information. This continuum may include notions such as data, information, knowledge, wisdom, and realization.

Education systems

Schooling occurs when society or a group or an individual sets up a curriculum to educate people, usually the young. Schooling can become systematic and thorough. Sometimes education systems can be used to promote doctrines or ideals as well as knowledge, and this can lead to abuse of the system.

Preschool education

Preschool education is the provision of education that focuses on educating children from the ages of infancy until six years old. The term preschool educational includes such programs as nursery school, day care, or kindergarten, which are occasionally used interchangeably, yet are distinct entities.

The philosophy of early childhood education is largely child-centered education. Therefore, there is a focus on the importance of play. Play provides children with the opportunity to actively explore, manipulate, and interact with their environment. Playing with products made especially for the preschool children helps a child in building self confidence, encourages independent learning and clears his concepts. For the development of their fine and large or gross motor movements, for the growth of the child’s eye-hand coordination, it is extremely important for him to ‘play’ with the natural things around him. It encourages children to investigate, create, discover and motivate them to take risks and add to their understanding of the world. It challenges children to achieve new levels of understanding of events, people and the environment by interacting with concrete materials.[2] Hands-on activities create authentic experiences in which children begin to feel a sense of mastery over their world and a sense of belonging and understanding of what is going on in their environment. This philosophy follows with Piaget’s ideals that children should actively participate in their world and various environments so as to ensure they are not ‘passive’ learners but ‘little scientists’ who are actively engaged.[3]

Primary education

Primary School in «open air». Teacher (priest) with class from the outskirts of Bucharest, around 1842.

Primary or elementary education consists of the first years of formal, structured education that occur during childhood. Kindergarten is usually the first stage in primary education, as in most jurisdictions it is compulsory, but it is also often associated with preschool education. In most countries, it is compulsory for children to receive primary education (though in many jurisdictions it is permissible for parents to provide it). Primary education generally begins when children are four to eight years of age. The division between primary and secondary education is somewhat arbitrary, but it generally occurs at about eleven or twelve years of age (adolescence); some educational systems have separate middle schools with the transition to the final stage of secondary education taking place at around the age of fourteen.

Secondary education

In most contemporary educational systems of the world, secondary education consists of the second years of formal education that occur during adolescence. It is characterized by transition from the typically compulsory, comprehensive primary education for minors to the optional, selective tertiary, «post-secondary,» or «higher» education (e.g., university, vocational school) for adults. Depending on the system, schools for this period or a part of it may be called secondary or high schools, gymnasiums, lyceums, middle schools, colleges, or vocational schools. The exact meaning of any of these varies between the systems. The exact boundary between primary and secondary education varies from country to country and even within them, but is generally around the seventh to the tenth year of education. Secondary education occurs mainly during the teenage years. In the United States and Canada primary and secondary education together are sometimes referred to as K-12 education. The purpose of secondary education can be to give common knowledge, to prepare for either higher education or vocational education, or to train directly to a profession.

Higher education

Higher education, also called tertiary, third stage or post secondary education, often known as academia, is the non-compulsory educational level following the completion of a school providing a secondary education, such as a high school, secondary school, or gymnasium. Tertiary education is normally taken to include undergraduate and postgraduate education, as well as vocational education and training. Colleges and universities are the main institutions that provide tertiary education (sometimes known collectively as tertiary institutions). Examples of institutions that provide post-secondary education are community colleges (Junior colleges as they are sometimes referred to in parts of Asia and Africa), vocational schools, trade or technology schools, colleges, and universities. They are sometimes known collectively as tertiary or post-secondary institutions. Tertiary education generally results in the receipt of certificates, diplomas, or academic degrees. Higher education includes teaching, research and social services activities of universities, and within the realm of teaching, it includes both the undergraduate level (sometimes referred to as tertiary education) and the graduate (or postgraduate) level (sometimes referred to as graduate school).

In most developed countries a high proportion of the population (up to 50 percent) now enter higher education at some time in their lives. Higher education is therefore very important to national economies, both as a significant industry in its own right, and as a source of trained and educated personnel for the rest of the economy. However, countries that are increasingly becoming more industrialized, such as those in Africa, Asia and South America, are more frequently using technology and vocational institutions to developed a more skilled work-force.

Adult education

Lifelong, or adult, education has become widespread in many countries. However, education is still seen by many as something aimed at children, and adult education is often branded as adult learning or lifelong learning. Adult education takes on many forms, from formal class-based learning to self-directed learning.

Lending libraries provide inexpensive informal access to books and other self-instructional materials. The rise in computer ownership and internet access has given both adults and children greater access to both formal and informal education.

In Scandinavia a unique approach to learning termed folkbildning has long been recognized as contributing to adult education through the use of learning circles. In Africa, government and international organizations have established institutes to help train adults in new skills so that they are to perform new jobs or utilize new technologies and skills in existing markets, such as agriculture.[4]

Alternative education

Alternative education, also known as non-traditional education or educational alternative, is a broad term which may be used to refer to all forms of education outside of traditional education (for all age groups and levels of education). This may include both forms of education designed for students with special needs (ranging from teenage pregnancy to intellectual disability) and forms of education designed for a general audience which employ alternative educational philosophies and/or methods.

Alternatives of the latter type are often the result of education reform and are rooted in various philosophies that are commonly fundamentally different from those of traditional compulsory education. While some have strong political, scholarly, or philosophical orientations, others are more informal associations of teachers and students dissatisfied with certain aspects of traditional education. These alternatives, which include charter schools, alternative schools, independent schools, and home-based learning vary widely, but often emphasize the value of small class size, close relationships between students and teachers, and a sense of community.

Education technology

Technology is an increasingly influential factor in education. Computers and mobile phones are being widely used in developed countries both to complement established education practices and develop new ways of learning such as online education (a type of distance education). This gives students the opportunity to choose what they are interested in learning. The proliferation of computers also means the increase of programming and blogging. Technology offers powerful learning tools that demand new skills and understandings of students, including Multimedia literacy, and provides new ways to engage students, such as classroom management software.

Technology is being used more not only in administrative duties in education but also in the instruction of students. The use of technologies such as PowerPoint and interactive whiteboard is capturing the attention of students in the classroom. Technology is also being used in the assessment of students. One example is the Audience Response System (ARS), which allows immediate feedback tests and classroom discussions.

The use of computers and the Internet is still in its infancy in developing countries due to limited infrastructure and the attendant high costs of access. Usually, various technologies are used in combination rather than as the sole delivery mechanism. For example, the Kothmale Community Radio Internet uses both radio broadcasts and computer and Internet technologies to facilitate the sharing of information and provide educational opportunities in a rural community in Sri Lanka.[5]

Education psychology

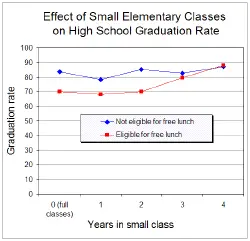

A class size experiment in the United States found that attending small classes for 3 or more years in the early grades increased high school graduation of students from low income families.[6]

Educational psychology is the study of how humans learn in educational settings, the effectiveness of educational interventions, the psychology of teaching, and the social psychology of schools as organizations. Although the terms «educational psychology» and «school psychology» are often used interchangeably, researchers and theorists are likely to be identified as educational psychologists, whereas practitioners in schools or school-related settings are identified as school psychologists. Educational psychology is concerned with the processes of educational attainment in the general population and in sub-populations such as gifted children and those with specific learning disabilities.

There was a great deal of work done on learning styles over the last two decades of twentieth century. Rita Stafford Dunn and Kenneth J. Dunn focused on identifying relevant stimuli that may influence learning and manipulating the school environment.[7] Howard Gardner identified individual talents or aptitudes in his theory of multiple intelligences.[8] Based on the works of Carl Jung, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and Keirsey’s Temperament Sorter focused on understanding how people’s personality affects the way they interact personally, and how this affects the way individuals respond to each other within the learning environment[9].

Education can be physically divided into many different learning «modes» based on the senses, with the following four learning modalities being most important:[10]

- Kinesthetic learning based on manipulating objects and engaging in activities.

- Visual learning based on observation and seeing what is being learned.

- Auditory learning based on listening to instructions/information.

- Tactile learning based on drawing or writing notes and hands-on activities.

Depending on their preferred learning modality, different teaching techniques have different levels of effectiveness. Effective teaching of all students requires a variety of teaching methods which cover all four learning modalities.

Educational psychology also takes into consideration elements of Developmental psychology as it greatly impacts an individual’s cognitive, social and personality development:

- Cognitive Development — primarily concerned with the ways in which infants and children acquire and advance their cognitive abilities. Major topics in cognitive development are the study of language acquisition and the development of perceptual-motor skills.

- Social development — focuses on the nature and causes of human social behavior, with an emphasis on how people think about each other and how they relate to each other.

- Personality development — an individual’s personality is a collection of emotional, thought, and behavioral patterns unique to a person that is consistent over time. Many personality theorists regard personality as a combination of various «traits,» that determine how an individual responds to various situations.

These three elements of development continue throughout the entire educational process, but are viewed and approached differently at different ages and educational levels. During the first levels of education, playing games is used to foster social interaction and skills, basic language and mathematical skills are used to lay the foundation for cognitive skills, while arts and crafts are employed to develop creativity and personal thinking. Later on in the educational system, more emphasis is placed on the cognitive skills, learning more complex esoteric educational skills and lessons.

Sociology of education

The sociology of education is the study of how social institutions and forces affect educational processes and outcomes, and vice versa. By many, education is understood to be a means of overcoming handicaps, achieving greater equality and acquiring wealth and status for all. Learners may be motivated by aspirations for progress and betterment. The purpose of education can be to develop every individual to their full potential. However, according to some sociologists, a key problem is that the educational needs of individuals and marginalized groups may be at odds with existing social processes, such as maintaining social stability through the reproduction of inequality. The understanding of the goals and means of educational socialization processes differs according to the sociological paradigm used. The sociology of education is based in three differing theories of perspectives: Structural functionalists, conflict theory, and structure and agency.

Structural functionalism

Structural functionalists believe that society tends towards equilibrium and social order. They see society like a human body, where key institutions work like the body’s organs to keep the society/body healthy and well.[11] Social health means the same as social order, and is guaranteed when nearly everyone accepts the general moral values of their society. Hence structural functionalists believe the purpose of key institutions, such as education, is to socialize young members of society. Socialization is the process by which the new generation learns the knowledge, attitudes and values that they will need as productive citizens. Although this purpose is stated in the formal curriculum, it is mainly achieved through «the hidden curriculum,»[12] a subtler, but nonetheless powerful, indoctrination of the norms and values of the wider society. Students learn these values because their behavior at school is regulated until they gradually internalize them and so accept them.

Education must, however perform another function to keep society running smoothly. As various jobs in society become vacant, they must be filled with the appropriate people. Therefore the other purpose of education is to sort and rank individuals for placement in the labor market. Those with the greatest achievement will be trained for the most important jobs in society and in reward, be given the highest incomes. Those who achieve the least, will be given the least demanding jobs, and hence the least income.

Conflict Theory

The perspective of conflict theory, contrary to the structural functionalist perspective, believes that society is full of vying social groups who have different aspirations, different access to life chances and gain different social rewards.[13] Relations in society, in this view, are mainly based on exploitation, oppression, domination, and subordination. This is a considerably more cynical picture of society than the previous idea that most people accept continuing inequality. Some conflict theorists believe education is controlled by the state which is controlled by those with the power, and its purpose is to reproduce the inequalities already existing in society as well as legitimize ‘acceptable’ ideas which actually work to reinforce the privileged positions of the dominant group. [13] Connell and White state that the education system is as much an arbiter of social privilege as a transmitter of knowledge.[14]

Education achieves its purpose by maintaining the status quo, where lower class children become lower class adults, and middle and upper class children become middle and upper class adults. This cycle occurs because the dominant group has, over time, closely aligned education with middle class values and aspirations, thus alienating people of other classes.[14] Many teachers assume that students will have particular middle class experiences at home, and for some children this assumption isn’t necessarily true. Some children are expected to help their parents after school and carry considerable domestic responsibilities in their often single-parent home.[15] The demands of this domestic labor often make it difficult for them to find time to do all their homework and thus affects their performance at school.

Structure and Agency

This theory of social reproduction has been significantly theorized by Pierre Bourdieu. However Bourdieu as a social theorist has always been concerned with the dichotomy between the objective and subjective, or to put it another way, between structure and agency. Bourdieu has therefore built his theoretical framework around the important concepts of habitus, field and cultural capital. These concepts are based on the idea that objective structures determine the probability of individuals’ life chances, through the mechanism of the habitus, where individuals internalize these structures. However, the habitus is also formed by, for example, an individual’s position in various fields, their family and their everyday experiences. Therefore one’s class position does not determine one’s life chances although it does play an important part alongside other factors.

Bourdieu employed the concept of cultural capital to explore the differences in outcomes for students from different classes in the French educational system. He explored the tension between the conservative reproduction and the innovative production of knowledge and experience.[16] He found that this tension is intensified by considerations of which particular cultural past and present is to be conserved and reproduced in schools. Bourdieu argues that it is the culture of the dominant groups, and therefore their cultural capital, which is embodied in schools, and that this leads to social reproduction.[16]

The cultural capital of the dominant group, in the form of practices and relation to culture, is assumed by the school to be the natural and only proper type of cultural capital and is therefore legitimated. It thus demands “uniformly of all its students that they should have what it does not give.”[17]. This legitimate cultural capital allows students who possess it to gain educational capital in the form of qualifications. Those students of less privileged classes are therefore disadvantaged. To gain qualifications they must acquire legitimate cultural capital, by exchanging their own (usually working-class) cultural capital.[18] This process of exchange is not a straight forward one, due to the class ethos of the less privileged students. Class ethos is described as the particular dispositions towards, and subjective expectations of, school and culture. It is in part determined by the objective chances of that class.[19] This means, that not only is it harder for children to succeed in school due to the fact that they must learn a new way of ‘being’, or relating to the world, and especially, a new way of relating to and using language, but they must also act against their instincts and expectations. The subjective expectations influenced by the objective structures located in the school, perpetuate social reproduction by encouraging less-privileged students to eliminate themselves from the system, so that fewer and fewer are to be found as one progresses through the levels of the system. The process of social reproduction is neither perfect nor complete,[16] but still, only a small number of less-privileged students make it all the way to the top. For the majority of these students who do succeed at school, they have had to internalize the values of the dominant classes and take them as their own, to the detriment of their original habitus and cultural values.

Therefore Bourdieu’s perspective reveals how objective structures play a large role in determining the achievement of individuals at school, but allows for the exercise of an individual’s agency to overcome these obstacles, although this choice is not without its penalties.

Challenges in Education

The goal of education is fourfold: the social purpose, intellectual purpose, economic purpose, and political/civic purpose. Current education issues include which teaching method(s) are most effective, how to determine what knowledge should be taught, which knowledge is most relevant, and how well the pupil will retain incoming knowledge.

There are a number of highly controversial issues in education. Should some knowledge be forgotten? Should classes be segregated by gender? What should be taught? There are also some philosophies, for example Transcendentalism, that would probably reject conventional education in the belief that knowledge should be gained through more direct personal experience.

Educational progressives or advocates of unschooling often believe that grades do not necessarily reveal the strengths and weaknesses of a student, and that there is an unfortunate lack of youth voice in the educational process. Some feel the current grading system lowers students’ self-confidence, as students may receive poor marks due to factors outside their control. Such factors include poverty, child abuse, and prejudiced or incompetent teachers.

By contrast, many advocates of a more traditional or «back to basics» approach believe that the direction of reform needs to be the opposite. Students are not inspired or challenged to achieve success because of the dumbing down of the curriculum and the replacement of the «canon» with inferior material. They believe that self-confidence arises not from removing hurdles such as grading, but by making them fair and encouraging students to gain pride from knowing they can jump over these hurdles. On the one hand, Albert Einstein, the most famous physicist of the twentieth century, who is credited with helping us understand the universe better, was not a model school student. He was uninterested in what was being taught, and he did not attend classes all the time. On the other hand, his gifts eventually shone through and added to the sum of human knowledge.

Education has always been and will most likely continue to be a contentious issue across the world. Like many complex issues, it is doubtful that there is one definitive answer. Rather, a mosaic approach that takes into consideration the national and regional culture the school is located in as well as remaining focused on what is best for the children being instructed, as is done in some areas, will remain the best path for educators and officials alike.

Developing countries

In developing countries, the number and seriousness of the problems faced are naturally greater. People are sometimes unaware of the importance of education, and there is economic pressure from those parents who prioritize their children’s making money in the short term over any long-term benefits of education. Recent studies on child labor and poverty have suggested that when poor families reach a certain economic threshold where families are able to provide for their basic needs, parents return their children to school. This has been found to be true, once the threshold has been breached, even if the potential economic value of the children’s work has increased since their return to school. Teachers are often paid less than other similar professions.

India is developing technologies that skip land based phone and internet lines. Instead, India launched EDUSAT, an education satellite that can reach more of the country at a greatly reduced cost. There is also an initiative to develop cheap laptop computers to be sold at cost, which will enable developing countries to give their children a digital education, and to close the digital divide across the world.

In Africa, NEPAD has launched an «e-school programme» to provide all 600,000 primary and high schools with computer equipment, learning materials and internet access within 10 years. Private groups, like the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, are working to give more individuals opportunities to receive education in developing countries through such programs as the Perpetual Education Fund.

Internationalization

Education is becoming increasingly international. Not only are the materials becoming more influenced by the rich international environment, but exchanges among students at all levels are also playing an increasingly important role. In Europe, for example, the Socrates-Erasmus Program stimulates exchanges across European universities. Also, the Soros Foundation provides many opportunities for students from central Asia and eastern Europe. Some scholars argue that, regardless of whether one system is considered better or worse than another, experiencing a different way of education can often be considered to be the most important, enriching element of an international learning experience.[20]

Notes

- ↑ educate The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ↑ Jane Healy, Your Child’s Growing Mind: Brain Development and Learning From Birth to Adolescence (Broadway 2004, ISBN 0767916158).

- ↑ Carol Garhart Mooney, Theories of Childhood: An Introduction to Dewey, Montessori, Erikson, Piaget & Vygotsky (Redleaf Press, 2000, ISBN 188483485X).

- ↑ «Ethiopia: Higher and Vocational Education since 1975» Encyclopedia of the Nations, 1991. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ↑ Daniel Taghioff, Seeds of Consensus—The Potential Role for Information and Communication Technologies in Development.Seminar in Advanced Methodologies and Professional Practice, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, April 2001. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ↑ J. D. Finn, S. B. Gerber, and J. Boyd-Zaharias, «Small classes in the early grades, academic achievement, and graduating from high school,» Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, (2005):214-233.

- ↑ Rita Stafford Dunn and Kenneth J. Dunn, Teaching Students Through Their Individual Learning Styles: A Practical Approach (Prentice Hall College Div, 1978, ISBN 0879098082).

- ↑ Howard Gardner, Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons in Theory and Practice (New York: Basic Books, 2006, ISBN 0465047688).

- ↑ Naomi L. Quenk, Essentials of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Assessment (Essentials of Psychological Assessment) (Wiley, 1999, ISBN 0471332399).

- ↑ Madison Michell, Kinesthetic, Visual, Auditory, Tactile, Oh My! What Are Learning Modalities and How Can You Incorporate Them in the Classroom? Edmentum, September 25, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ↑ J. Bessant and R. Watts, Sociology Australia (Allen & Unwin, 2002, ISBN 1865086126).

- ↑ G. Harper, “Society, culture, socialization and the individual” in C. Stafford and B. Furze, (eds). Society and Change, (Melbourne: Macmillan Education Australia, 1997)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 B. Furze and P. Healy, “Understanding society and change” in C. Stafford and B. Furze. (eds.) Society and Change, (Melbourne: Macmillan Education Australia, 1997).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 R. W. Connell and V. White, «Child poverty and educational action» in D. Edgar, D. Keane, and P. McDonald (eds), Child Poverty (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1989).

- ↑ B. Wilson and J. Wyn, Shaping Futures: Youth Action for Livelihood (Allen & Unwin, 1987, ISBN 004302002X).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 R. Harker, “Education and Cultural Capital” in R. Harker, C. Mahar, and C. Wilkes, (eds). An Introduction to the Work of Pierre Bourdieu: the Practice of Theory (Macmillan Press, 1990, ISBN 0312049323).

- ↑ D. Swartz, “Pierre Bourdieu: The Cultural Transmission of Social Inequality,” in D. Robbins. Pierre Bourdieu Volume II. (London: Sage Publications, 2000), 207-217.

- ↑ R. Harker, “On Reproduction, Habitus and Education” in D. Robbins, (1984), 164-176.

- ↑ K. Gorder, “Understanding School Knowledge: a critical appraisal of Basil Bernstein and Pierre Bourdieu” in D. Robbins, (1980), 218-233.

- ↑ H.F.W. Dubois, G. Padovano, & G. Stew, «Improving international nurse training: an American–Italian case study.» International Nursing Review 53(2) (2006): 110–116.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Benei, Veronique. Manufacturing Citizenship: Education and Nationalism in Europe, South Asian and China. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 978-0415364881

- Bessant, J. and R. Watts. Sociology Australia. Allen & Unwin, 2002. ISBN 1865086126

- Bifulco, Robert and Helen Ladd, «Institutional Change and Coproduction of Public Services: The Effect of Charter Schools on Parental Involvement.» Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory (Oct 2006): 552-576.

- Bourdieu, Pierre and Jean Claude Passeron. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. Sage Publications, 1990. ISBN 978-0803983205

- Buddin, Richard and Ron Zimmer, «Student achievement in charter schools:A complex picture.» Journal of Policy Analysis and Management (2005): 351-371.

- Dharampal. The Beautiful Tree: Indigenous Indian Education in the Eighteenth Century. Other India Press, 2000 (original 1983).

- Dubois, H.F.W., G. Padovano, & G. Stew. Improving international nurse training: an American–Italian case study. International Nursing Review 53(2) (2006): 110–116.

- Dunn, Rita Stafford, and Kenneth J. Dunn. Teaching Students Through Their Individual Learning Styles: A Practical Approach. Prentice Hall College Div, 1978. ISBN 0879098082

- Edgar, D., D. Keane, and P. McDonald (eds). Child Poverty. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1989.

- Finn, J.D., S. B. Gerber, and J. Boyd-Zaharias, «Small classes in the early grades, academic achievement, and graduating from high school,» Journal of Educational Psychology 97 (2005): 214-233.

- Gardner, Howard. Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons in Theory and Practice. New York: Basic Books, 2006. ISBN 0465047688

- Gollnick, Donna M. and Philip C. Chinn. Multicultural Education in a Pluralistic Society & Exploring Diversity Package. Prentice Hall, 2005. ISBN 978-0131555181

- Harker, Richard, Cheleen Mahar, and Chris Wilkes. An Introduction to the Work of Pierre Bourdieu: The Practice of Theory. Palgrave Macmillan, 1990. ISBN 0333524764

- Healy, Jane. Your Child’s Growing Mind: Brain Development and Learning From Birth to Adolescence, third ed., Broadway, 2004. ISBN 0767916158

- Li Yi. The Structure and Evolution of Chinese Social Stratification. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2005. ISBN 0761833315

- Lucas, J. L., M. A. Blazek, & A. B. Raley. «The lack of representation of educational psychology and school psychology in introductory psychology textbooks.» Educational Psychology 25 (2005): 347-351.

- Mooney, Carol Garhart. Theories of Childhood: An Introduction to Dewey, Montessori, Erikson, Piaget & Vygotsky. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf Press, 2000. ISBN 188483485X

- Quenk, Naomi L. Essentials of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Assessment (Essentials of Psychological Assessment). Wiley, 1999. ISBN 0471332399

- Sargent, M. The New Sociology for Australians, Third Ed. Melbourne: Longman Chesire, 1994.

- Schofield, K. “The Purposes of Education.” Queensland State Education, 2010 (original 1999).

- Shih, Timothy, K. Shih and Jason C. Hung, Eds. Future Directions in Distance Learning and Communication Technologies. IGI Global, 2006. ISBN 978-1599043760

- Siljander, Pauli. Systemaattinen johdatus kasvatustieteeseen. Otava, 2002.

- Stafford, C., and Furze, B. (eds.). Society and Change. Melbourne: Macmillan Education Australia.

- Wilson, B., and J. Wyn. Shaping Futures: Youth Action for Livelihood. Allen & Unwin, 1987. ISBN 004302002X

External links

All links retrieved July 12, 2019.

- Lys Anzia, «Educate a Woman, You Educate a Nation» — South Africa Aims to Improve its Education for Girls WNN — Women News Network, August 28, 2007.

- World Bank Education

- UNESCO — International Institute for Educational Planning

- The Encyclopedia of Informal Education

| General subfields of the Social Sciences |

|---|

| Anthropology | Communication | Economics | Education |

| Linguistics | Law | Psychology | Social work | Sociology |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Education history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Education»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Asked by: Oliver Nitzsche

Score: 4.6/5

(18 votes)

Education is a conscious and deliberate effort to create an atmosphere of learning and the learning process so that learners are actively developing the potential for him to have the spiritual strength of religious, self-control, personality, intelligence, noble character, and the skills needed themselves and society.

What is education different authors?

Education is characterized as a learning cycle for the person to achieve information and comprehension of the higher explicit items and explicit. The information acquired officially coming about an individual has an example of thought and conduct as per the training they have acquired. Huge Indonesian Dictionary (1991)

What is the best definition for education?

Education is the process of facilitating learning, or the acquisition of knowledge, skills, values, morals, beliefs, and habits. Educational methods include teaching, training, storytelling, discussion and directed research. … A right to education has been recognized by some governments and the United Nations.

What are the different definitions of education?

Education is defined as the process of gaining knowledge. An example of education is attending college and studying. … The process of training and developing the knowledge, skill, mind, character, etc., esp. by formal schooling; teaching; training.

What is the definition of education according to Aristotle?

Aristotle’s definition of education is the same as that of his teachers, that is, the “the creation of a sound mind in a sound body”. Thus to him the aim of education was the welfare of the individuals so as to bring happiness in their lives.

31 related questions found

What is Plato’s definition of education?

Abstract. Plato regards education as a means to achieve justice, both individual justice and social justice. According to Plato, individual justice can be obtained when each individual develops his or her ability to the fullest. In this sense, justice means excellence.

What are the 7 philosophy of education?

These include Essentialism, Perennialism, Progressivism, Social Reconstructionism, Existentialism, Behaviorism, Constructivism, Conservatism, and Humanism.

What is the current definition of education?

Education is both the act of teaching knowledge to others and the act of receiving knowledge from someone else. Education also refers to the knowledge received through schooling or instruction and to the institution of teaching as a whole. Education has a few other senses as a noun.

What is the modern definition of education?

Education is the imparting and acquiring of knowledge through teaching and learning, especially at a school or similar institution. … Formal education refers to the process by which teachers instruct students in courses of study within institutions.

Who is the father of education?

Known as the “father of American education,” Horace Mann (1796–1859), a major force behind establishing unified school systems, worked to establish a varied curriculum that excluded sectarian instruction.

What is the important of education?

Proper and good education is very important for all of us. It facilitates quality learning all through the life among people of any age group, cast, creed, religion and region. It is the process of achieving knowledge, values, skills, beliefs, and moral habits.

What is the main purpose of education?

The main purpose of education is the integral development of a person. In addition, it is a source of its obvious benefits for a fuller and better life. Education can contribute to the betterment of society as a whole. It develops a society in which people are aware of their rights and duties.

Why do we need education?

It helps people become better citizens, get a better-paid job, shows the difference between good and bad. Education shows us the importance of hard work and, at the same time, helps us grow and develop. Thus, we are able to shape a better society to live in by knowing and respecting rights, laws, and regulations.

What are the characteristics of education?

Characteristics of education (A) Formal Education Highlights (i) Planned with a particular end in view. (ii) Limited to a specific period. (iii) Well-defined and systematic curriculum (iv) Givenby specially qualified teachers. (v) Includes activities outside the classroom (vi) Observesstrict discipline.

Who is an educated person?

An educated person is one who has undergone a process of learning that results in enhanced mental capability to function effectively in familiar and novel situations in personal and intellectual life.

What are the characteristics of modern education?

Important Characteristics Of Modern Learners

- Easily distracted. Modern learners have a lot on their proverbial plates. …

- Social learners. Without a doubt, modern learners are more social than any previous generation. …

- Crave constant knowledge. …

- Always on-the-go. …

- Independent. …

- Impatient. …

- Overworked.

What is the importance of modern education?

Modern education allows students to do a lot more than just learning and help them become more social and interactive. Cocurricular activities, recreational activities, drama and art in education help students to become creative, industrious as well as patient.

What is the modern aim of education?

The objective of modern education was to inculcate values in students such as equality, secularism, education for all, and environmental protection, etc.

What is the origin of education?

Education Meaning of Education- The root of Word education is derived from Latin words Educare, Educere, and Educatum. Word educare means to nourish, to bring up. The word educere means to lead froth, to draw out. The latine “educatum”, which itself is composed of two terms, “E” and “Duco”.

What are the 3 types of education?

There are three main types of education, namely, Formal, Informal and Non-formal. Each of these types is discussed below.

What is the root word of educated?

Craft (1984) noted that there are two different Latin roots of the English word «education.» They are «educare,» which means to train or to mold, and «educere,» meaning to lead out.

What are the 10 philosophy of education?

These include Essentialism, Perennialism, Progressivism, Social Reconstructionism, Existentialism, Behaviorism, Constructivism, Conservatism, and Humanism.

What are the 5 major philosophies of education?

There are five philosophies of education that focus on teachers and students; essentialism, perennialism, progressivism, social reconstructionism, and existentialism. Essentialism is what is used in today’s classrooms and was helped by William Bagley in the 1930s.

What are some examples of teaching philosophy?

(1) The teacher’s role is to act as a guide. (2) Students must have access to hands-on activities. (3) Students should be able to have choices and let their curiosity direct their learning. (4) Students need the opportunity to practice skills in a safe environment.

What are Plato’s main ideas?

Plato believed that reality is divided into two parts: the ideal and the phenomena. The ideal is the perfect reality of existence. The phenomena are the physical world that we experience; it is a flawed echo of the perfect, ideal model that exists outside of space and time. Plato calls the perfect ideal the Forms.