2.1. Morphology: definition.

The

notion of morpheme.

Morphology

(Gr. morphe – form, and logos – word) is a branch of grammar that

concerns itself with the internal structure of words and

peculiarities of their grammatical categories and their semantics.

The study

of Modern English morphology consists of four main items,

(1) general

study of morphemes and types of word-form derivation,

(2) the system of parts of

speech,

(3) the

study of each separate part of speech, the grammatical categories

connected with it, and its syntactical functions.

The

morpheme

may be defined as an elementary meaningful segmental component of the

word. It is built up by phonemes and is indivisible into smaller

segments as regards its significative function.

Example:

writers

can be divided into three morphemes:

(1) writ-,

expressing the basic lexical meaning of the word,

(2) —er-,

expressing the idea of agent performing the action indicated by the

root of the verb,

(3) —s,

indicating number, that is, showing that more than one person of the

type indicated is meant.

Two or more

morphemes may sound the same but be basically different, that is,

they may be homonyms.

Thus the -er

morpheme indicating the doer of an action as in writer

has a homonym — the morpheme -er

denoting the comparative degree of adjectives and adverbs, as in

longer.

There may

be zero

morphemes,

that is, the absence of a morpheme may indicate a certain meaning.

Thus, if we compare the words book

and books,

both derived from the stem book-,

we may say that while books

is characterised by the –s

morpheme indicating a plural form, book

is characterised by the zero morpheme indicating a singular form.

Traditional

classification of morphemes is based on the two basic criteria:

-

positional

– the location of the marginal

morphemes

(периферийные

морфемы)

in relation to the central

ones

(центральные

морфемы) -

semantic/functional

– the correlative contribution (соотносительный

вклад)

of the morphemes to the general meaning of the word.

According

to this classification, morphemes are divided into:

-

root-morphemes

(roots)

– express the concrete, ‘material’ (насыщенная

конкретным

содержанием,

вещественная)

part of the meaning of the word.

The roots

of notional words are classical lexical

morphemes.

-

affixal

morphemes (affixes) – express

the specificational (спецификационная)

part of the meaning of the word.

This

specification can have lexico-semantic (лексическая)

and grammatico-semantic (грамматическая)

character.

The affixal

morphemes include:

1) prefixes

2) suffixes

Prefixes

and lexical suffixes have word-building functions, and form the stem

of the word together with the root.

3)

inflexions

(флексия)/grammatical

suffix

(Blokh)

The

morpheme serves to derive a grammatical form; it has no lexical

meaning of its own and expresses different morphological categories.

The

abstract complete morphemic model of the common English word is the

following: prefix + root + lexical suffix + inflection/grammatical

suffix.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

WORD STRUCTURE IN MODERN ENGLISH

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of morphemes. Allomorphs.

II. Structural types of words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of stems. Derivational types of words.

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of Morphemes. Allomorphs.

There are two levels of approach to the study of word- structure: the level of morphemic analysis and the level of derivational or word-formation analysis.

Word is the principal and basic unit of the language system, the largest on the morphologic and the smallest on the syntactic plane of linguistic analysis.

It has been universally acknowledged that a great many words have a composite nature and are made up of morphemes, the basic units on the morphemic level, which are defined as the smallest indivisible two-facet language units.

The term morpheme is derived from Greek morphe “form ”+ -eme. The Greek suffix –eme has been adopted by linguistic to denote the smallest unit or the minimum distinctive feature.

The morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of form. A form in these cases a recurring discrete unit of speech. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words, not independently, although a word may consist of single morpheme. Even a cursory examination of the morphemic structure of English words reveals that they are composed of morphemes of different types: root-morphemes and affixational morphemes. Words that consist of a root and an affix are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word building known as affixation (or derivation).

The root-morpheme is the lexical nucleus of the word; it has a very general and abstract lexical meaning common to a set of semantically related words constituting one word-cluster, e.g. (to) teach, teacher, teaching. Besides the lexical meaning root-morphemes possess all other types of meaning proper to morphemes except the part-of-speech meaning which is not found in roots.

Affixational morphemes include inflectional affixes or inflections and derivational affixes. Inflections carry only grammatical meaning and are thus relevant only for the formation of word-forms. Derivational affixes are relevant for building various types of words. They are lexically always dependent on the root which they modify. They possess the same types of meaning as found in roots, but unlike root-morphemes most of them have the part-of-speech meaning which makes them structurally the important part of the word as they condition the lexico-grammatical class the word belongs to. Due to this component of their meaning the derivational affixes are classified into affixes building different parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives or adverbs.

Roots and derivational affixes are generally easily distinguished and the difference between them is clearly felt as, e.g., in the words helpless, handy, blackness, Londoner, refill, etc.: the root-morphemes help-, hand-, black-, London-, fill-, are understood as the lexical centers of the words, and –less, -y, -ness, -er, re- are felt as morphemes dependent on these roots.

Distinction is also made of free and bound morphemes.

Free morphemes coincide with word-forms of independently functioning words. It is obvious that free morphemes can be found only among roots, so the morpheme boy- in the word boy is a free morpheme; in the word undesirable there is only one free morpheme desire-; the word pen-holder has two free morphemes pen- and hold-. It follows that bound morphemes are those that do not coincide with separate word- forms, consequently all derivational morphemes, such as –ness, -able, -er are bound. Root-morphemes may be both free and bound. The morphemes theor- in the words theory, theoretical, or horr- in the words horror, horrible, horrify; Angl- in Anglo-Saxon; Afr- in Afro-Asian are all bound roots as there are no identical word-forms.

It should also be noted that morphemes may have different phonemic shapes. In the word-cluster please , pleasing , pleasure , pleasant the phonemic shapes of the word stand in complementary distribution or in alternation with each other. All the representations of the given morpheme, that manifest alternation are called allomorphs/or morphemic variants/ of that morpheme.

The combining form allo- from Greek allos “other” is used in linguistic terminology to denote elements of a group whose members together consistute a structural unit of the language (allophones, allomorphs). Thus, for example, -ion/ -tion/ -sion/ -ation are the positional variants of the same suffix, they do not differ in meaning or function but show a slight difference in sound form depending on the final phoneme of the preceding stem. They are considered as variants of one and the same morpheme and called its allomorphs.

Allomorph is defined as a positional variant of a morpheme occurring in a specific environment and so characterized by complementary description.

Complementary distribution is said to take place, when two linguistic variants cannot appear in the same environment.

Different morphemes are characterized by contrastive distribution, i.e. if they occur in the same environment they signal different meanings. The suffixes –able and –ed, for instance, are different morphemes, not allomorphs, because adjectives in –able mean “ capable of beings”.

Allomorphs will also occur among prefixes. Their form then depends on the initials of the stem with which they will assimilate.

Two or more sound forms of a stem existing under conditions of complementary distribution may also be regarded as allomorphs, as, for instance, in long a: length n.

II. Structural types of words.

The morphological analysis of word- structure on the morphemic level aims at splitting the word into its constituent morphemes – the basic units at this level of analysis – and at determining their number and types. The four types (root words, derived words, compound, shortenings) represent the main structural types of Modern English words, and conversion, derivation and composition the most productive ways of word building.

According to the number of morphemes words can be classified into monomorphic and polymorphic. Monomorphic or root-words consist of only one root-morpheme, e.g. small, dog, make, give, etc. All polymorphic word fall into two subgroups: derived words and compound words – according to the number of root-morphemes they have. Derived words are composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational morphemes, e.g. acceptable, outdo, disagreeable, etc. Compound words are those which contain at least two root-morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant. There can be both root- and derivational morphemes in compounds as in pen-holder, light-mindedness, or only root-morphemes as in lamp-shade, eye-ball, etc.

These structural types are not of equal importance. The clue to the correct understanding of their comparative value lies in a careful consideration of: 1)the importance of each type in the existing wordstock, and 2) their frequency value in actual speech. Frequency is by far the most important factor. According to the available word counts made in different parts of speech, we find that derived words numerically constitute the largest class of words in the existing wordstock; derived nouns comprise approximately 67% of the total number, adjectives about 86%, whereas compound nouns make about 15% and adjectives about 4%. Root words come to 18% in nouns, i.e. a trifle more than the number of compound words; adjectives root words come to approximately 12%.

But we cannot fail to perceive that root-words occupy a predominant place. In English, according to the recent frequency counts, about 60% of the total number of nouns and 62% of the total number of adjectives in current use are root-words. Of the total number of adjectives and nouns, derived words comprise about 38% and 37% respectively while compound words comprise an insignificant 2% in nouns and 0.2% in adjectives. Thus it is the root-words that constitute the foundation and the backbone of the vocabulary and that are of paramount importance in speech. It should also be mentioned that root words are characterized by a high degree of collocability and a complex variety of meanings in contrast with words of other structural types whose semantic structures are much poorer. Root- words also serve as parent forms for all types of derived and compound words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

In most cases the morphemic structure of words is transparent enough and individual morphemes clearly stand out within the word. The segmentation of words is generally carried out according to the method of Immediate and Ultimate Constituents. This method is based on the binary principle, i.e. each stage of the procedure involves two components the word immediately breaks into. At each stage these two components are referred to as the Immediate Constituents. Each Immediate Constituent at the next stage of analysis is in turn broken into smaller meaningful elements. The analysis is completed when we arrive at constituents incapable of further division, i.e. morphemes. These are referred to Ultimate Constituents.

A synchronic morphological analysis is most effectively accomplished by the procedure known as the analysis into Immediate Constituents. ICs are the two meaningful parts forming a large linguistic unity.

The method is based on the fact that a word characterized by morphological divisibility is involved in certain structural correlations. To sum up: as we break the word we obtain at any level only ICs one of which is the stem of the given word. All the time the analysis is based on the patterns characteristic of the English vocabulary. As a pattern showing the interdependence of all the constituents segregated at various stages, we obtain the following formula:

un+ { [ ( gent- + -le ) + -man ] + -ly}

Breaking a word into its Immediate Constituents we observe in each cut the structural order of the constituents.

A diagram presenting the four cuts described looks as follows:

1. un- / gentlemanly

2. un- / gentleman / — ly

3. un- / gentle / — man / — ly

4. un- / gentl / — e / — man / — ly

A similar analysis on the word-formation level showing not only the morphemic constituents of the word but also the structural pattern on which it is built.

The analysis of word-structure at the morphemic level must proceed to the stage of Ultimate Constituents. For example, the noun friendliness is first segmented into the ICs: [frendlı-] recurring in the adjectives friendly-looking and friendly and [-nıs] found in a countless number of nouns, such as unhappiness, blackness, sameness, etc. the IC [-nıs] is at the same time an UC of the word, as it cannot be broken into any smaller elements possessing both sound-form and meaning. Any further division of –ness would give individual speech-sounds which denote nothing by themselves. The IC [frendlı-] is next broken into the ICs [-lı] and [frend-] which are both UCs of the word.

Morphemic analysis under the method of Ultimate Constituents may be carried out on the basis of two principles: the so-called root-principle and affix principle.

According to the affix principle the splitting of the word into its constituent morphemes is based on the identification of the affix within a set of words, e.g. the identification of the suffix –er leads to the segmentation of words singer, teacher, swimmer into the derivational morpheme – er and the roots teach- , sing-, drive-.

According to the root-principle, the segmentation of the word is based on the identification of the root-morpheme in a word-cluster, for example the identification of the root-morpheme agree- in the words agreeable, agreement, disagree.

As a rule, the application of these principles is sufficient for the morphemic segmentation of words.

However, the morphemic structure of words in a number of cases defies such analysis, as it is not always so transparent and simple as in the cases mentioned above. Sometimes not only the segmentation of words into morphemes, but the recognition of certain sound-clusters as morphemes become doubtful which naturally affects the classification of words. In words like retain, detain, contain or receive, deceive, conceive, perceive the sound-clusters [rı-], [dı-] seem to be singled quite easily, on the other hand, they undoubtedly have nothing in common with the phonetically identical prefixes re-, de- as found in words re-write, re-organize, de-organize, de-code. Moreover, neither the sound-cluster [rı-] or [dı-], nor the [-teın] or [-sı:v] possess any lexical or functional meaning of their own. Yet, these sound-clusters are felt as having a certain meaning because [rı-] distinguishes retain from detain and [-teın] distinguishes retain from receive.

It follows that all these sound-clusters have a differential and a certain distributional meaning as their order arrangement point to the affixal status of re-, de-, con-, per- and makes one understand —tain and –ceive as roots. The differential and distributional meanings seem to give sufficient ground to recognize these sound-clusters as morphemes, but as they lack lexical meaning of their own, they are set apart from all other types of morphemes and are known in linguistic literature as pseudo- morphemes. Pseudo- morphemes of the same kind are also encountered in words like rusty-fusty.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of Stems. Derivational types of word.

The morphemic analysis of words only defines the constituent morphemes, determining their types and their meaning but does not reveal the hierarchy of the morphemes comprising the word. Words are no mere sum totals of morpheme, the latter reveal a definite, sometimes very complex interrelation. Morphemes are arranged according to certain rules, the arrangement differing in various types of words and particular groups within the same types. The pattern of morpheme arrangement underlies the classification of words into different types and enables one to understand how new words appear in the language. These relations within the word and the interrelations between different types and classes of words are known as derivative or word- formation relations.

The analysis of derivative relations aims at establishing a correlation between different types and the structural patterns words are built on. The basic unit at the derivational level is the stem.

The stem is defined as that part of the word which remains unchanged throughout its paradigm, thus the stem which appears in the paradigm (to) ask ( ), asks, asked, asking is ask-; thestem of the word singer ( ), singer’s, singers, singers’ is singer-. It is the stem of the word that takes the inflections which shape the word grammatically as one or another part of speech.

The structure of stems should be described in terms of IC’s analysis, which at this level aims at establishing the patterns of typical derivative relations within the stem and the derivative correlation between stems of different types.

There are three types of stems: simple, derived and compound.

Simple stems are semantically non-motivated and do not constitute a pattern on analogy with which new stems may be modeled. Simple stems are generally monomorphic and phonetically identical with the root morpheme. The derivational structure of stems does not always coincide with the result of morphemic analysis. Comparison proves that not all morphemes relevant at the morphemic level are relevant at the derivational level of analysis. It follows that bound morphemes and all types of pseudo- morphemes are irrelevant to the derivational structure of stems as they do not meet requirements of double opposition and derivative interrelations. So the stem of such words as retain, receive, horrible, pocket, motion, etc. should be regarded as simple, non- motivated stems.

Derived stems are built on stems of various structures though which they are motivated, i.e. derived stems are understood on the basis of the derivative relations between their IC’s and the correlated stems. The derived stems are mostly polymorphic in which case the segmentation results only in one IC that is itself a stem, the other IC being necessarily a derivational affix.

Derived stems are not necessarily polymorphic.

Compound stems are made up of two IC’s, both of which are themselves stems, for example match-box, driving-suit, pen-holder, etc. It is built by joining of two stems, one of which is simple, the other derived.

In more complex cases the result of the analysis at the two levels sometimes seems even to contracted one another.

The derivational types of words are classified according to the structure of their stems into simple, derived and compound words.

Derived words are those composed of one root- morpheme and one or more derivational morpheme.

Compound words contain at least two root- morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant.

Derivational compound is a word formed by a simultaneous process of composition and derivational.

Compound words proper are formed by joining together stems of word already available in the language.

Теги:

Word structure in modern english

Реферат

Английский

Просмотров: 27701

Найти в Wikkipedia статьи с фразой: Word structure in modern english

Chapter 6: Word Forms

What’s a word? It seems almost silly to ask such a simple question, but if you think about it, the question doesn’t have an obvious answer. A famous linguist named Ferdinand de Saussure said that a word is like a coin because it has two sides to it that can never be separated. One side of this metaphorical coin is the form of a word: the sounds (or letters) that combine to make the spoken or written word. The other side of the coin is the meaning of the word: the image or concept we have in our mind when we use the word. So a word is something that links a given form with a given meaning.

Linguists have also noticed that words behave in a way that other elements of mental grammar don’t because words are free. What does it mean for a word to be free? One observation that leads us to say that words are free is that they can appear in isolation, on their own. In ordinary conversation, we don’t often utter just a single word, but there are plenty of contexts in which a single word is indeed an entire utterance. Here are some examples:

What are you doing? Cooking.

What are you cooking? Soup.

How does it taste? Delicious.

Can I have some? No.

Each of those single words is perfectly grammatical standing in isolation as the answer to a question.

Another reason we say that words are free is that they’re moveable: they can occupy a whole variety of different positions in a sentence. Look at these examples:

Penny is making soup.

Soup is delicious.

I love to eat soup when it’s cold outside.

The word soup can appear as the last word in a sentence, as the first word, or in the middle of a sentence. It’s free to be moved around.

The other important observation we can make about words is that they’re inseparable: We can’t break them up by putting other pieces inside them. For example, in the sentence,

Penny cooked some carrots.

The word carrot has a bit of information added to the end of it to show that there’s more than one carrot. But that bit of information can’t go just anywhere: it can’t interrupt the word carrot:

*Penny cooked some car-s-rot.

This might seem like a trivial observation – of course, you can’t break words up into bits! – but if we look at a word that’s a little more complex than carrots we see that it’s an important insight. What about:

Penny bought two vegetable peelers.

That’s fine, but it’s totally impossible to say:

*Penny bought two vegetables peeler.

even though she probably uses the peeler to peel multiple vegetables. It’s not that a plural -s can’t go on the end of the word vegetable; it’s that the word vegetable peeler is a single word (even though we spell it with a space between the two parts of it). And because it’s a single word, it’s inseparable, so we can’t add anything else into the middle of it.

So we’ve seen that a word is a free form that has a meaning. But you’ve probably already noticed that there are other forms that have meaning and some of them seem to be smaller than whole words. A morpheme is the smallest form that has meaning. Some morphemes are free: they can appear in isolation. (This means that some words are also morphemes.) But some morphemes can only ever appear when they’re attached to something else; these are called bound morphemes.

Let’s go back to that simple sentence,

Penny cooked some carrots.

It’s quite straightforward to say that this sentence has four words in it. We can make the observations we just discussed above to check for isolation, moveability, and inseparability to provide evidence that each of Penny, cooked, some, and carrots is a word. But there are more than four units of meaning in the sentence.

Penny cook-ed some carrot-s.

The word cooked is made up of the word cook plus another small form that tells us that the cooking happened in the past. And the word carrots is made up of carrot plus a bit that tells us that there’s more than one carrot.

That little bit that’s spelled –ed (and pronounced a few different ways depending on the environment) has a consistent meaning in English: past tense. We can easily think of several other examples where that form has that meaning, like walked, baked, cleaned, kicked, kissed. This –ed unit appears consistently in this form and consistently has this meaning, but it never appears in isolation: it’s always attached at the end of a word. It’s a bound morpheme. For example, if someone tells you, “I need you to walk the dog,” it’s not grammatical to answer “-ed” to indicate that you already walked the dog.

Likewise, the bit that’s spelled –s or –es (and pronounced a few different ways) has a consistent meaning in many different words, like carrots, bananas, books, skates, cars, dishes, and many others. Like –ed, it is not free: it can’t appear in isolation. It’s a bound morpheme too.

If a word is made up of just one morpheme, like banana, swim, hungry, then we say that it’s morphologically simple, or monomorphemic.

But many words have more than one morpheme in them: they’re morphologically complex or polymorphemic. In English, polymorphemic words are usually made up of a root plus one or more affixes. The root morpheme is the single morpheme that determines the core meaning of the word. In most cases in English, the root is a morpheme that could be free. The affixes are bound morphemes. English has affixes that attach to the end of a root; these are called suffixes, like in books, teaching, happier, hopeful, singer. And English also has affixes that attach to the beginning of a word, called prefixes, like in unzip, reheat, disagree, impossible.

Some languages have bound morphemes that go into the middle of a word; these are called infixes. Here are some examples from Tagalog (a language with about 24 million speakers, most of them in the Philippines).

| [takbuh] | run | [tumakbuh] | ran |

| [lakad] | walk | [lumakad] | walked |

| [bili] | buy | [bumili] | bought |

| [kain] | eat | [kumain] | ate |

It might seem like the existence of infixes is a problem for our claim above that words are inseparable. But languages that allow infixation do so in a systematic way — the infix can’t be dropped just anywhere in the word. In Tagalog, the position of the infix depends on the organization of the syllables in the word.

A. morpheme

The smallest meaningful unit in a language. A morpheme cannot be divided without altering or destroying its meaning. For example, the English word kind is a morpheme. If the d is removed, it changes to kin, which has a different meaning. Some words consist of one morpheme, e.g. kind, others of more than one. For example, the English word unkindness consists of three morphemes: the STEM1 kind, the negative prefix un-, and the noun-forming suffix -ness. Morphemes can have grammatical functions. For example, in English the –s in she talks is a grammatical morpheme which shows that the verb is the third-person singular present-tense form.

B. allomorph

any of the different forms of a MORPHEME. For example, in English the plural morpheme is often shown in writing by adding -s to the end of a word, e.g. cat /kæt/ – cats /kæts/. Sometimes this plural morpheme is pronounced /z/, e.g. dog /díg/ – dogs /dígz/, and sometimes it is pronounced /Iz/, e.g. class /klæs/ – classes /`klæsız/. /s/, /z/, and /Iz/ all have the same grammatical function in these examples, they all show plural; they are all allomorphs of the plural morpheme.

C. root

also base form

a MORPHEME which is the basic part of a word and which may, in many languages, occur on its own (e.g. English: man, hold, cold, rhythm). Roots may be joined to other roots (e.g. English: house _ hold → household) and/or take AFFIXes (e.g. manly, coldness) or COMBINING FORMs (e.g. biorhythm).

D. base form

another term for ROOT OR STEM1.

For example, the English word helpful has the base form help.

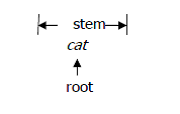

E. stem1

also base form

that part of a word to which an inflectional AFFIX is or can be added. For example, in English the inflectional affix -s can be added to the stem work to form the plural works in the works of Shakespeare. The stem of a word may be:

a. a simple stem consisting of only one morpheme (ROOT), e.g. work

b. a root plus a derivational affix, e.g. work _ -er _ worker

c. two or more roots, e.g. work _ shop _ workshop.

Thus we can have work _ -s _ works, (work _ -er) _ workers, or

(work _ shop) _ -s _ workshops.

F. Stem versus roots

STEM and ROOT are used to refer to the ‘base’ of a word. The part to which affixes attach. The distinction between them is based on the distinction between inflectional and derivational.

Consider a word like ‘kickers’, it contains two suffixes, one derivational (-er), the other inflectional (-s). strip both affixes off and you are left with kick, which we call a ROOT. Add back on the derivational suffix –er and you get kicker, we call the STEM.

More generally, a root is any single morpheme which is not an affix. Normally, you can find a root by removing all the affixes (both derivational and inflectional) from a word. The stem of a word, on other hand, is found by removing all the inflectional affixes, but leaving any derivational affixes in place.

A root is always a single morpheme. A stem on the other hand, may consists of more than one morpheme. Many stems, like cat consists of only a single root. The stem and the root are identical.

other stems consists of two or more roots, as in view-point. Neither view nor point is an affix and both are single morphemes. So they are both considered to be roots.

a stem containing more than one root is called a COMPOUND STEM or simply a COMPOUND; the process of forming such stems is called COMPOUNDING.

Compounding may, in some cases, involve derivational affixes too, as in rabble-rouser-r; this stem consists of two roots plus a derivational suffix.

and stem may contain more than one derivational affix, as in interlinearizer (a type of computer program that is used by linguists for inserting interlinear word-by-word or morpheme-by-morpheme glosses in a text)

thus, a stem consist of one or more roots, plus zero or more derivational affixes. A root, in contrast, is always a single morpheme.

All stems serve as the base to which inflectional affixes attach. So, for example, all the nouns mentioned above have plural forms.

a. cat-s

b. kicker-s

c. viewpoint-s

d. rabble-rouser-s

e. interlinearizer-s

virtually all roots are also stems and the simplest stems (those consisting of only one morpheme) are also roots.