The Worst Keith Richards Rolling Stones Subtitulada Inglés Español.mp3

02:41

3.53 MB

118.1K

The Rolling Stones Paint It Black Official Lyric Video.mp3

03:47

4.98 MB

449.1M

The Rolling Stones Anybody Seen My Baby OFFICIAL PROMO.mp3

04:29

5.90 MB

71.6M

Glastonbury 2013 The Rolling Stones In One Word.mp3

01:24

1.84 MB

15.6K

The Rolling Stones Worried About You OFFICIAL PROMO.mp3

05:17

6.95 MB

2.8M

The Rolling Stones Sympathy For The Devil Official Lyric Video.mp3

06:23

8.40 MB

130.7M

The Rolling Stones Living In A Ghost Town.mp3

04:00

5.26 MB

12.8M

The Rolling Stones Wild Horses Acoustic Lyric Video.mp3

05:49

7.66 MB

26.1M

Rolling Stones 1986 Dirty Work.mp3

40:04

52.73 MB

3.4K

The Rolling Stones Scarlet Goats Head Soup 2020 Lyric Video.mp3

03:45

4.94 MB

1.6M

The Rolling Stones Brown Sugar Live OFFICIAL.mp3

03:23

4.45 MB

8.4M

The Rolling Stones Mother S Little Helper Lyric Video.mp3

02:48

3.68 MB

2.5M

The Rolling Stones Happy Live 1972 Official.mp3

03:12

4.21 MB

859.3K

The Rolling Stones Country Honk Official Lyric Video.mp3

03:09

4.15 MB

173.2K

The Rolling Stones You Got Me Rocking OFFICIAL PROMO.mp3

03:39

4.80 MB

2.1M

Rolling Stone Keith Richards Uses A Yiddish Word To Express Himself.mp3

11

247.07 KB

6K

The Rolling Stones She S A Rainbow Official Lyric Video.mp3

04:13

5.55 MB

50.8M

The Rolling Stones Bob Wills Is Still The King Live OFFICIAL.mp3

03:43

4.89 MB

2.4M

The Rolling Stones Dead Flowers Live OFFICIAL.mp3

04:13

5.55 MB

4.4M

The Rolling Stones Bitch Lyrics.mp3

03:38

4.78 MB

67.3K

The Rolling Stones Highwire OFFICIAL PROMO.mp3

03:45

4.94 MB

559.3K

The Rolling Stones Live With Me Official Lyric Video.mp3

03:35

4.72 MB

181.9K

The Rolling Stones Angie OFFICIAL PROMO Version 1.mp3

04:40

6.14 MB

63.6M

The Rolling Stones I Can T Get No Satsfaction Live OFFICIAL.mp3

08:15

10.86 MB

10.8M

The Rolling Stones Beast Of Burden Live OFFICIAL.mp3

06:38

8.73 MB

3.9M

The Rolling Stones Sweet Virginia Live OFFICIAL.mp3

04:28

5.88 MB

5.7M

The Rolling Stones Monkey Man Official Lyric Video.mp3

04:13

5.55 MB

2M

The Rolling Stones Complicated Official Lyric Video.mp3

03:18

4.34 MB

108.4K

The Rolling Stones Sympathy For The Devil Official Video 4K.mp3

08:49

11.60 MB

54M

The Rolling Stones Undercover Of The Night OFFICIAL PROMO EXPLICIT.mp3

04:59

6.56 MB

2.3M

The Rolling Stones Let It Bleed Official Lyric Video.mp3

05:29

7.22 MB

658.4K

The Rolling Stones Sympathy For The Devil Live OFFICIAL.mp3

07:42

10.13 MB

30.2M

The Rolling Stones The Last Time Official Lyric Video.mp3

03:44

4.91 MB

1.2M

The Rolling Stones Perform You Can T Always Get What You Want One World Together At Home.mp3

05:38

7.41 MB

4.9M

The Rolling Stones She S So Cold OFFICIAL PROMO.mp3

04:00

5.26 MB

29M

The Rolling Stones Miss You.mp3

03:33

4.67 MB

73.4M

The Rolling Stones Gimme Shelter Word Of My Mouth Riddim.mp3

03:16

4.30 MB

780

The Rolling Stones All Down The Line Live OFFICIAL.mp3

04:16

5.62 MB

3M

The Rolling Stones Ride Em On Down.mp3

03:18

4.34 MB

37.9M

The Rolling Stones Play With Fire Official Lyric Video.mp3

02:17

3.01 MB

4.8M

Still Rolling Stones Lyric Video Lauren Daigle.mp3

04:12

5.53 MB

3.1M

The Rolling Stones Criss Cross.mp3

04:50

6.36 MB

2.5M

The Rolling Stones Beast Of Burden Lyrics.mp3

03:27

4.54 MB

2.1M

Wild Horses Rolling Stones Guitar Playalong Lesson Larry Lawver.mp3

05:54

7.76 MB

11.1K

The Rolling Stones Winter Lyrics.mp3

05:28

7.19 MB

234.2K

Muddy Waters The Rolling Stones Baby Please Don T Go Live At Checkerboard Lounge.mp3

10:56

14.39 MB

22.3M

The Rolling Stones Love Is Strong OFFICIAL PROMO.mp3

03:42

4.87 MB

18.6M

The Rolling Stones She S Like A Rainbow Lyric Video.mp3

04:12

5.53 MB

592

The Rolling Stones Miss You Official Lyric Video.mp3

04:49

6.34 MB

362K

The Rolling Stones You Can T Always Get What You Want Official Video 4K.mp3

04:29

5.90 MB

20.7M

|

The Rolling Stones |

|

|---|---|

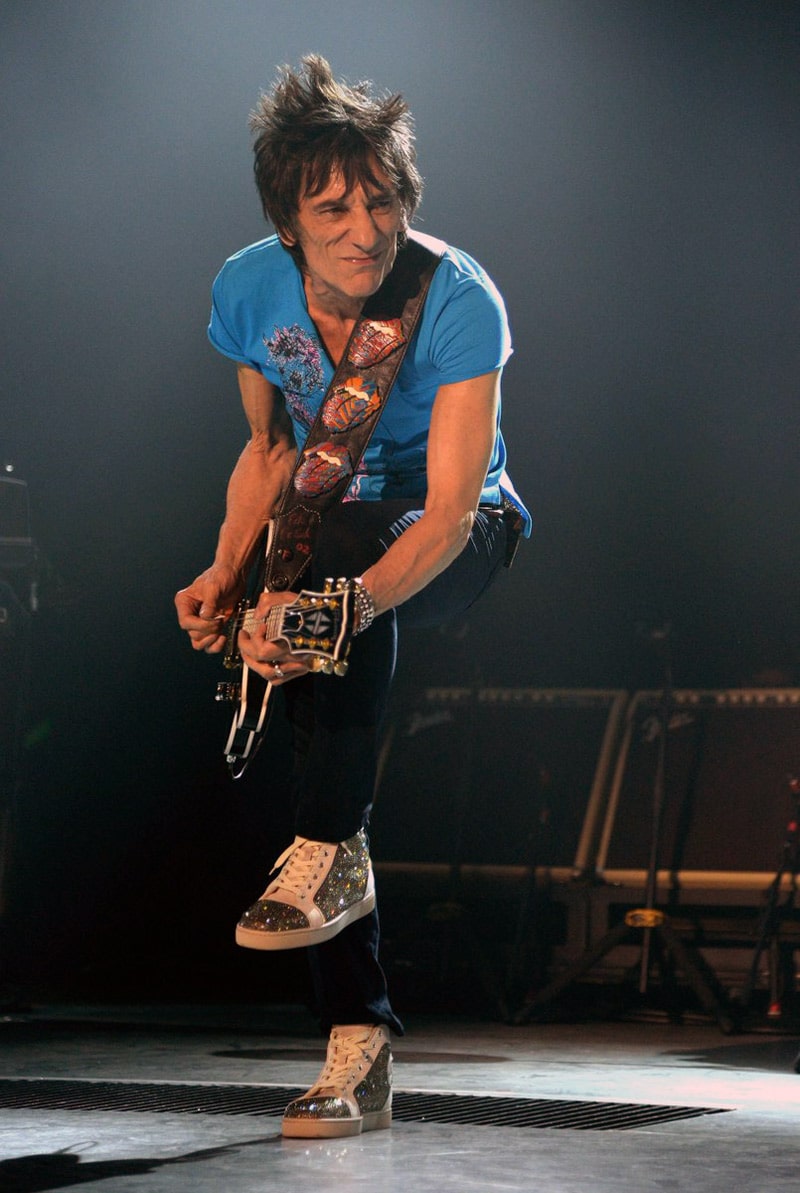

The Rolling Stones performing at Summerfest in Milwaukee in 2015. From left to right: Charlie Watts, Ronnie Wood, Mick Jagger, and Keith Richards. |

|

| Background information | |

| Origin | London, England |

| Genres |

|

| Years active | 1962–present |

| Labels |

|

| Members |

|

| Past members |

|

| Website | rollingstones.com |

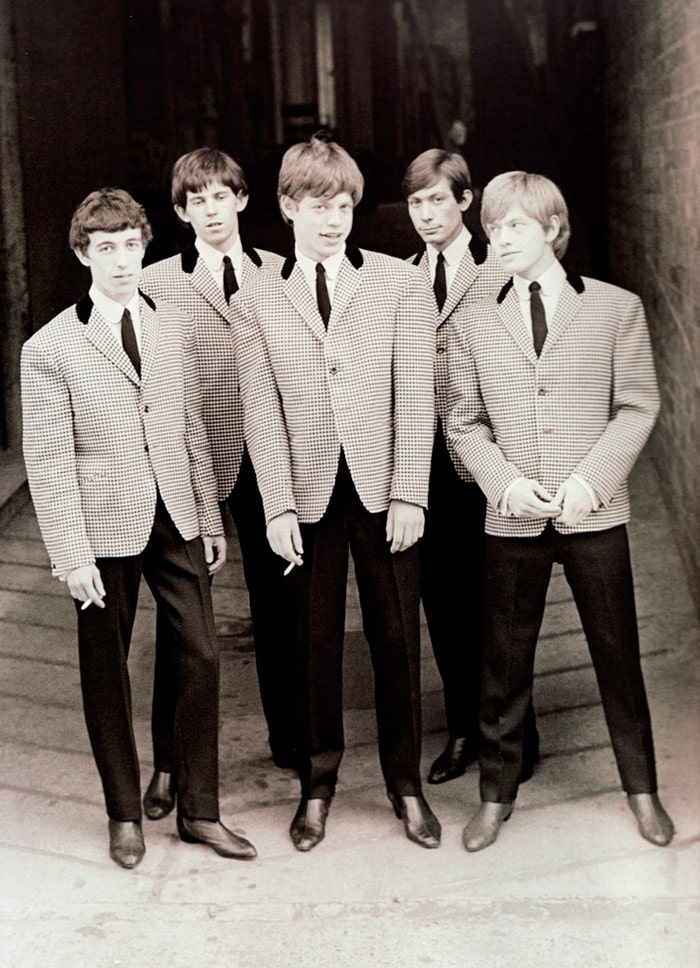

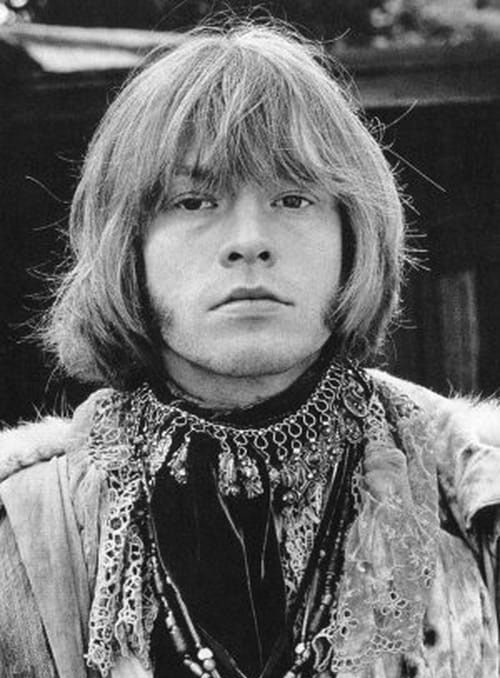

The Rolling Stones are an English rock band formed in London in 1962. Active for six decades, they are one of the most popular and enduring bands of the rock era. In the early 1960s, the Rolling Stones pioneered the gritty, rhythmically driven sound that came to define hard rock. Their first stable line-up consisted of vocalist Mick Jagger, multi-instrumentalist Brian Jones, guitarist Keith Richards, bassist Bill Wyman, and drummer Charlie Watts. During their formative years, Jones was the primary leader: he assembled the band, named it, and drove their sound and image. After Andrew Loog Oldham became the group’s manager in 1963, he encouraged them to write their own songs. Jagger and Richards became the primary creative force behind the band, alienating Jones, who had developed a drug addiction that interfered with his ability to contribute meaningfully.

Rooted in blues and early rock and roll, the Rolling Stones started out playing covers and were at the forefront of the British Invasion in 1964, becoming identified with the youthful and rebellious counterculture of the 1960s. They then found greater success with their own material, as «(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction» (1965), «Get Off of My Cloud» (1965), and «Paint It Black» (1966) became international number-one hits. Aftermath (1966) – their first entirely original album – is considered by The Daily Telegraph to be the most important of their formative records. In 1967, they had the double-sided hit «Ruby Tuesday»/»Let’s Spend the Night Together» and experimented with psychedelic rock on Their Satanic Majesties Request. They returned to their rhythm and blues roots with hit songs such as «Jumpin’ Jack Flash» (1968) and «Honky Tonk Women» (1969), and albums such as Beggars Banquet (1968), featuring «Sympathy for the Devil», and Let It Bleed (1969), featuring «You Can’t Always Get What You Want» and «Gimme Shelter». Let It Bleed was the first of five consecutive number-one albums in the UK.

Jones left the band shortly before his death in 1969, having been replaced by guitarist Mick Taylor. That year they were first introduced on stage as «The Greatest Rock and Roll Band in the World». Sticky Fingers (1971), which yielded «Brown Sugar» and included the first usage of their tongue and lips logo, was their first of eight consecutive number-one studio albums in the US. Exile on Main St. (1972), featuring «Tumbling Dice», and Goats Head Soup (1973), yielding the hit ballad «Angie», were also best sellers. Taylor was replaced by Ronnie Wood in 1974. The band continued to release successful albums, including their two largest sellers: Some Girls (1978), featuring «Miss You», and Tattoo You (1981), featuring «Start Me Up». Steel Wheels (1989) was widely considered a comeback album and was followed by Voodoo Lounge (1994), a worldwide number-one album. Both releases were promoted by large stadium and arena tours, as the Stones continued to be a huge concert attraction; by 2007 they had recorded the all-time highest-grossing concert tour three times, and as recently as 2021 they were the highest-earning live act of the year. From Wyman’s departure in 1993 to Watts’ death in 2021, the band continued as a four-piece core, with Darryl Jones playing bass on tour and on most studio recordings, while Steve Jordan became their touring drummer following Watts’ death. Their 2016 album, Blue & Lonesome, became their twelfth UK number-one album.

The Rolling Stones’ estimated record sales of 200 million make them one of the best-selling music artists of all time. The band has won three Grammy Awards and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. They were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1989 and the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2004. Billboard magazine and Rolling Stone have ranked the band as one of the greatest of all time.

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

Keith Richards and Mick Jagger became classmates and childhood friends in 1950 in Dartford, Kent.[1][2] The Jagger family moved to Wilmington, Kent, five miles (8.0 km) away, in 1954.[3] In the mid-1950s, Jagger formed a garage band with his friend Dick Taylor; the group mainly played material by Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Howlin’ Wolf, and Bo Diddley.[3] Jagger next met Richards on 17 October 1961 on platform two of Dartford railway station.[4] The Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters records Jagger was carrying revealed to Richards a shared interest. A musical partnership began shortly afterwards.[5][6] Richards and Taylor often met Jagger at his house. The meetings moved to Taylor’s house in late 1961, where Alan Etherington and Bob Beckwith joined the trio; the quintet called themselves the Blues Boys.[7]

In March 1962, the Blues Boys read about the Ealing Jazz Club in the newspaper Jazz News, which mentioned Alexis Korner’s rhythm and blues band, Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated. The Blues Boys sent a tape of their best recordings to Korner, who was impressed.[8] On 7 April, they visited the Ealing Jazz Club, where they met the members of Blues Incorporated, who included slide guitarist Brian Jones, keyboardist Ian Stewart, and drummer Charlie Watts.[8] After a meeting with Korner, Jagger and Richards started jamming with the group.[8]

Jones, having left Blues Incorporated, advertised for bandmates in Jazz Weekly the week of 2 May 1962.[9] Ian Stewart was among the first to respond to the ad.[9] In June, Jagger, Taylor, and Richards left Blues Incorporated to join Jones and Stewart.[9] The first rehearsal included guitarist Geoff Bradford and vocalist Brian Knight, both of whom decided not to join the band. They objected to playing the Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley songs preferred by Jagger and Richards.[10] That same month, the addition of the drummer Tony Chapman completed the line-up of Jagger, Richards, Jones, Stewart, and Taylor. According to Richards, Jones named the band during a phone call to Jazz News. When asked by a journalist for the band’s name, Jones saw a Muddy Waters LP lying on the floor; one of the tracks was «Rollin’ Stone».[11][12]

1962–1964: Building a following[edit]

The band played their first show billed as «the Rollin’ Stones» on 12 July 1962, at the Marquee Club in London.[13][14][15][a] At the time, the band consisted of Jones, Jagger, Richards, Stewart, and Taylor.[18] Bill Wyman auditioned for the role of bass guitarist at a pub in Chelsea on 7 December 1962 and was hired as a successor to Dick Taylor. The band were impressed by his instrument and amplifiers (including the Vox AC30).[19] The classic line-up of the Rolling Stones, with Charlie Watts on drums, played for the first time in public on Saturday, 12 January 1963 at the Ealing Jazz Club.[20] However, it was not until a gig there on 2 February 1963 that Watts became the Stones’ permanent drummer.[21]

The back room of what was the Crawdaddy Club in Richmond, London, where the Rolling Stones had their first residency, starting in February 1963

Shortly afterwards, the band began their first tour of the UK, performing Chicago blues and songs by Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley.[22] By 1963, they were finding their musical stride as well as popularity.[23] In 1964, they beat The Beatles as the number one United Kingdom band in two surveys.[24] The band’s name was changed shortly after their first gig to «The Rolling Stones».[25][26] The group’s then acting manager, Giorgio Gomelsky, secured a Sunday afternoon residency at the Crawdaddy Club in Richmond, London, in February 1963.[27]

In May 1963, the Rolling Stones signed Andrew Loog Oldham as their manager.[28] He had been directed to them by his previous clients, the Beatles.[15][29] Because Oldham was only nineteen and had not reached the age of majority—he was also younger than anyone in the band—he could not obtain an agent’s licence or sign any contracts without his mother co-signing.[29] By necessity he joined with booking agent Eric Easton[30] to secure record financing and assistance booking venues.[28] Gomelsky, who had no written agreement with the band, was not consulted.[31]

Initially, Oldham tried applying the strategy used by Brian Epstein, the Beatles’ manager, and have the band members wear suits. He later changed his mind and imagined a band that contrasted with the Beatles, featuring unmatched clothing, long hair, and an unclean appearance. He wanted to make the Stones «a raunchy, gamy, unpredictable bunch of undesirables» and to «establish that the Stones were threatening, uncouth and animalistic».[32] Stewart left the official line-up, but remained road manager and touring keyboardist. Of Stewart’s decision, Oldham later said, «Well, he just doesn’t look the part, and six is too many for [fans] to remember the faces in the picture.»[33] Later, Oldham reduced the band members’ ages in publicity material to make them appear as teenagers.[34]

Decca Records, which had declined to sign a deal with the Beatles, gave the Rolling Stones a recording contract with favourable terms.[35] The band got three times a new act’s typical royalty rate, full artistic control of recordings, and ownership of the recording master tapes.[36][37] The deal also let the band use non-Decca recording studios. Regent Sound Studios, a mono facility equipped with egg boxes on the ceiling for sound treatment, became their preferred location.[38][39] Oldham, who had no recording experience but made himself the band’s producer, said Regent had a sound that «leaked, instrument-to-instrument, the right way» creating a «wall of noise» that worked well for the band.[37][40] Because of Regent’s low booking rates, the band could record for extended periods rather than the usual three-hour blocks common at other studios. All tracks on the first Rolling Stones album, The Rolling Stones, were recorded there.[41][42]

Oldham contrasted the Rolling Stones’ independence with the Beatles’ obligation to record in EMI’s studios, saying it made the Beatles appear as «mere mortals … sweating in the studio for the man».[43] He promoted the Rolling Stones as the nasty counterpoint to the Beatles, by having the band pose unsmiling on the cover of their first album. He also encouraged the press to use provocative headlines such as: «Would you let your daughter marry a Rolling Stone?»[44][45] By contrast, Wyman says, «Our reputation and image as the Bad Boys came later, completely there, accidentally. … [Oldham] never did engineer it. He simply exploited it exhaustively.»[46] In a 1972 interview, Wyman stated, «We were the first pop group to break away from the whole Cliff Richard thing where the bands did little dance steps, wore identical uniforms and had snappy patter.»[47]

A cover version of Chuck Berry’s «Come On» was the Rolling Stones’ first single, released on 7 June 1963. The band refused to play it at live gigs,[48] and Decca bought only one ad to promote the record. At Oldham’s direction, fan-club members bought copies at record shops polled by the charts,[49] helping «Come On» rise to number 21 on the UK Singles Chart.[50] Having a charting single gave the band entrée to play outside London, starting with a booking at the Outlook Club in Middlesbrough on 13 July, sharing the billing with the Hollies.[51][b] Later in 1963, Oldham and Easton arranged the band’s first big UK concert tour as a supporting act for American stars, including Bo Diddley, Little Richard, and the Everly Brothers. The tour gave the band the opportunity to hone their stagecraft.[37][53][54]

During the tour the band recorded their second single, a Lennon–McCartney-penned number entitled «I Wanna Be Your Man».[55][56] It reached number 13 on the UK charts.[57] The Beatles 1963 album, With the Beatles, includes their version of the song.[58] On 1 January 1964, the Stones’ were the first band to play on the BBC’s Top of the Pops, performing «I Wanna Be Your Man».[59] In January 1964 the band released a self-titled EP, which became their first number 1 record in the UK.[60] The third single by the Stones, Buddy Holly’s «Not Fade Away», reflecting Bo Diddley’s style, was released in February 1964 and reached number 3.[61]

Oldham saw little future for an act that gave up the chance to get significant songwriting royalties by only playing songs of what he described as «middle-aged blacks», and limiting their appeal to teenage audiences. Jagger and Richards decided to write songs together. Oldham described the first batch as «soppy and imitative».[62] Because the band’s songwriting developed slowly, songs on their first album The Rolling Stones (1964; issued in the US as England’s Newest Hit Makers), were primarily covers, with only one Jagger/Richards original—»Tell Me (You’re Coming Back)»—and two numbers credited to Nanker Phelge, the pen name used for songs written by the entire group.[63]

The Rolling Stones’ first US tour in June 1964 was «a disaster», according to Wyman. «When we arrived, we didn’t have a hit record [there] or anything going for us.»[64] When the band appeared on the variety show The Hollywood Palace, that week’s guest host, Dean Martin, mocked both their hair and their performance.[65] During the tour they recorded for two days at Chess Studios in Chicago, meeting many of their most important influences, including Muddy Waters.[66][67] These sessions included what would become the Rolling Stones’ first number 1 hit in the UK, their cover version of Bobby and Shirley Womack’s «It’s All Over Now».[68]

The Stones followed the Famous Flames, featuring James Brown, in the theatrical release of the 1964 film T.A.M.I. Show, which showcased American acts with British Invasion artists. According to Jagger, «We weren’t actually following James Brown because there was considerable time between the filming of each section. Nevertheless, he was still very annoyed about it …»[69] On 25 October the band appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show. Because of the pandemonium surrounding the Stones, Sullivan initially declined to rebook them.[70] However, he booked them for an appearances in 1966[71] and 1967.[72]

A second EP, Five by Five, was issued in the UK in August 1964.[73] In the US the EP was expanded into their second LP, 12 X 5, which was released in October during the tour.[74] The Rolling Stones’ fifth UK single, a cover of Willie Dixon’s «Little Red Rooster»—with «Off the Hook», credited to Nanker Phelge, as the B-side—was released in November 1964 and became their second number 1 hit in the UK.[61] The band’s US distributors, London Records, declined to release «Little Red Rooster» as a single. In December 1964, the distributor released the band’s first single with Jagger/Richards originals on both sides: «Heart of Stone», with «What a Shame» as the B-side; the single went to number 19 in the US.[75]

1965–1967: Height of fame[edit]

The Rolling Stones members Keith Richards, Bill Wyman, and Charlie Watts at Turku Airport in Turku, Finland, on 25 June 1965.

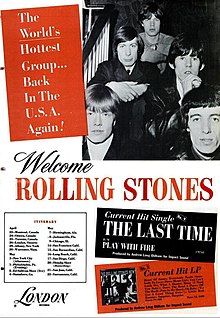

The band’s second UK LP, The Rolling Stones No. 2, was released in January 1965 and reached number 1 on the charts. The US version, released in February as The Rolling Stones, Now!, reached number 5. The album was recorded at Chess Studios in Chicago and RCA Studios in Los Angeles.[76] In January and February of that year, the band played 34 shows for around 100,000 people in Australia and New Zealand.[77] The single «The Last Time», released in February, was the first Jagger/Richards composition to reach number 1 on the UK charts;[61] it reached number 9 in the US. It was later identified by Richards as «the bridge into thinking about writing for the Stones. It gave us a level of confidence; a pathway of how to do it.»[78]

Their first international number 1 hit was «(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction», recorded in May 1965 during the band’s third North American tour. Richards recorded the guitar riff that drives the song with a fuzzbox as a scratch track to guide a horn section. Nevertheless, the final cut was without the planned horn overdubs. Issued in the summer of 1965, it was their fourth UK number 1 and their first in the US, where it spent four weeks at the top of the Billboard Hot 100. It was a worldwide commercial success for the band.[78][79] The US version of the LP Out of Our Heads, released in July 1965, also went to number 1; it included seven original songs, three Jagger/Richards numbers and four credited to Nanker Phelge.[80] Their second international number 1 single «Get Off of My Cloud» was released in the autumn of 1965,[81] followed by another US-only LP, December’s Children (And Everybody’s).[82]

A trade ad for the 1965 Rolling Stones’ North American tour

The album Aftermath, released in the late spring of 1966, was the first LP to be composed entirely of Jagger/Richards songs;[83] it reached number 1 in the UK and number 2 in the US.[84] In a 2018 retrospective, The Daily Telegraph considered Aftermath to be most important of the band’s formative records.[85] On this album, Jones’ contributions expanded beyond guitar and harmonica. To the Middle Eastern-influenced «Paint It Black»[c] he added sitar; to the ballad «Lady Jane» he added dulcimer, and to «Under My Thumb» he added marimbas.[86] Aftermath also contained «Goin’ Home», a nearly 12-minute song that included elements of jamming and improvisation.[87]

The Stones’ success on the British and American singles charts peaked during the 1960s.[88][89] «19th Nervous Breakdown»[90] was released in February 1966, and reached number 2 in the UK[91] and US charts;[92] «Paint It Black» reached number 1 in the UK and US in May 1966.[61][89] «Mother’s Little Helper», released in June 1966, reached number 8 in the US;[92] it was one of the first pop songs to discuss the issue of prescription drug abuse.[93][94] «Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?» was released in September 1966 and reached number 5 in the UK[95] and number 9 in the US.[92] It had a number of firsts for the group: it was the first Stones recording to feature brass horns, and the back-cover photo on the original US picture sleeve depicted the group satirically dressed in drag. The song was accompanied by one of the first official music videos, directed by Peter Whitehead.[96][97]

During their North American tour in June and July 1966, the Stones’ high-energy concerts proved highly successful with young people, while alienating local police who had the physically exhausting task of controlling the often rebellious crowds. According to the Stones historians Philippe Margotin and Jean-Michel Guesdon, the band’s notoriety «among the authorities and the establishment seems to have been inversely proportional to their popularity among young people». In an effort to capitalise on this, London released the live album Got Live If You Want It! in December.[98] The band’s first greatest hits album Big Hits (High Tide and Green Grass) was released in the UK in November 1966, a different version of which had been released in the US in March that year.[99]

January 1967 saw the release of Between the Buttons, which reached number 3 in the UK and number 2 in the US. It was Andrew Oldham’s last venture as the Rolling Stones’ producer. Allen Klein took over his role as the band’s manager in 1965. Richards recalled, «There was a new deal with Decca to be made … and he said he could do it.»[100] The US version included the double A-side single «Let’s Spend the Night Together» and «Ruby Tuesday»,[101] which went to number 1 in the US and number 3 in the UK. When the band went to New York to perform the numbers on The Ed Sullivan Show in January, they were ordered to change the lyrics of the refrain of «Let’s Spend the Night Together» to «let’s spend some time together».[102][103]

In early 1967, Jagger, Richards, and Jones began to be hounded by authorities over their recreational drug use, after News of the World ran a three-part feature entitled «Pop Stars and Drugs: Facts That Will Shock You».[104] The series described alleged LSD parties hosted by the Moody Blues and attended by top stars including the Who’s Pete Townshend and Cream’s Ginger Baker, and described alleged admissions of drug use by leading pop musicians. The first article targeted Donovan (who was raided and charged soon after); the second instalment (published on 5 February) targeted the Rolling Stones.[105] A reporter who contributed to the story spent an evening at the exclusive London club Blaise’s, where a member of the Rolling Stones allegedly took several Benzedrine tablets, displayed a piece of hashish, and invited his companions back to his flat for a «smoke». The article claimed this was Mick Jagger, but it turned out to be a case of mistaken identity; the reporter had in fact been eavesdropping on Brian Jones. Two days after the article was published, Jagger filed a writ for libel against the News of the World.[106][105]

A week later, on 12 February, Sussex police, tipped off by the paper,[d] raided a party at Keith Richards’ home, Redlands. No arrests were made at the time, but Jagger, Richards, and their friend art dealer Robert Fraser were subsequently charged with drug offences. Andrew Oldham was afraid of being arrested and fled to America.[108][109] Richards said in 2003, «When we got busted at Redlands, it suddenly made us realize that this was a whole different ball game and that was when the fun stopped. Up until then it had been as though London existed in a beautiful space where you could do anything you wanted.»[110]

In March 1967, while awaiting the consequences of the police raid, Jagger, Richards, and Jones took a short trip to Morocco, accompanied by Marianne Faithfull, Jones’ girlfriend Anita Pallenberg, and other friends. During this trip the stormy relations between Jones and Pallenberg deteriorated to the point that she left Morocco with Richards.[111] Richards said later: «That was the final nail in the coffin with me and Brian. He’d never forgive me for that and I don’t blame him, but hell, shit happens.»[112] Richards and Pallenberg would remain a couple for twelve years. Despite these complications, the Rolling Stones toured Europe in March and April 1967. The tour included the band’s first performances in Poland, Greece, and Italy.[113] June 1967 saw the release of the US-only compilation album Flowers.[114]

On 10 May 1967, the day Jagger, Richards and Fraser were arraigned in connection with the Redlands charges, Jones’ house was raided by police. He was arrested and charged with possession of cannabis.[102] Three of the five Stones now faced drug charges. Jagger and Richards were tried at the end of June. Jagger received a three-month prison sentence for the possession of four amphetamine tablets; Richards was found guilty of allowing cannabis to be smoked on his property and sentenced to a year in prison.[115][116] Both Jagger and Richards were imprisoned at that point but were released on bail the next day, pending appeal.[117]

The Times ran the famous editorial entitled «Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel?», in which conservative editor William Rees-Mogg surprised his readers by his unusually critical discourse on the sentencing, pointing out that Jagger had been treated far more harshly for a minor first offence than «any purely anonymous young man».[118] While awaiting the appeal hearings, the band recorded a new single, «We Love You», as a thank you for their fans’ loyalty. It began with the sound of prison doors closing, and the accompanying music video included allusions to the trial of Oscar Wilde.[119][120][121] On 31 July, the appeals court overturned Richards’ conviction, and reduced Jagger’s sentence to a conditional discharge.[122] Jones’ trial took place in November 1967. In December, after appealing the original prison sentence, Jones received a £1,000 fine and was put on three years’ probation, with an order to seek professional help.[123]

In December 1967, the band released Their Satanic Majesties Request, which reached number 3 in the UK and number 2 in the US. It drew unfavourable reviews and was widely regarded as a poor imitation of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.[124][125] Satanic Majesties was recorded while Jagger, Richards, and Jones were awaiting their court cases. The band parted ways with Oldham during the sessions. The split was publicly amicable,[126] but in 2003 Jagger said: «The reason Andrew left was because he thought that we weren’t concentrating and that we were being childish. It was not a great moment really—and I would have thought it wasn’t a great moment for Andrew either. There were a lot of distractions and you always need someone to focus you at that point, that was Andrew’s job.»[102] Satanic Majesties became the first album the Rolling Stones produced on their own. Its psychedelic sound was complemented by the cover art, which featured a 3D photo by Michael Cooper, who had also photographed the cover of Sgt. Pepper. Bill Wyman wrote and sang a track on the album: «In Another Land», also released as a single, the first on which Jagger did not sing lead.[127]

1968–1972: Jones’ departure and death, «Greatest Rock and Roll Band in the World»[edit]

The band spent the first few months of 1968 working on material for their next album. Those sessions resulted in the song «Jumpin’ Jack Flash», released as a single in May. The subsequent album, Beggars Banquet, an eclectic mix of country and blues–inspired tunes, marked the band’s return to their rhythm and blues roots. It was also the beginning of their collaboration with producer Jimmy Miller. It featured the lead single «Street Fighting Man» (which addressed the political upheavals of May 1968) and «Sympathy for the Devil».[128][129] Controversy over the design of the album cover, which featured a public toilet with graffiti covering the wall behind it, delayed the album’s release for six months.[130] While the band had «absolute artistic control over their albums», Decca[131] was not enthused about the cover’s depiction of graffiti reading «John Loves Yoko» being included;[132] the album was released that December, with a different cover design.[133][e] It reached number 3 in the UK and number 5 in the US.

The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus, which originally began as an idea about «the new shape of the rock-and-roll concert tour», was filmed at the end of 1968.[15] It featured John Lennon, Yoko Ono, the Dirty Mac, the Who, Jethro Tull, Marianne Faithfull, and Taj Mahal. The footage was shelved for 28 years but was finally released officially in 1996,[135] with a DVD version released in October 2004.[136]

By the time of Beggars Banquet‘s release, Brian Jones was only sporadically contributing to the band. Jagger said that Jones was «not psychologically suited to this way of life».[137] His drug use had become a hindrance, and he was unable to obtain a US visa. Richards reported that in a June meeting with Jagger, Watts, and himself at Jones’ house, Jones admitted that he was unable to «go on the road again», and left the band saying, «I’ve left, and if I want to I can come back.»[6] On 3 July 1969, less than a month later, Jones drowned under mysterious circumstances in the swimming pool at his home, Cotchford Farm, in Hartfield, East Sussex.[138] The band auditioned several guitarists, including Paul Kossoff,[139] as a replacement for Jones, before settling on Mick Taylor, who was recommended to Jagger by John Mayall.[140]

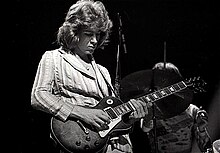

Mick Taylor is, in part, responsible for the Stones’ new sound in the early 1970s. Replacing Brian Jones in 1969, Taylor’s onstage debut with the band was in Hyde Park, London, on 5 July 1969, two days after Jones’ death.

The Rolling Stones were scheduled to play at a free concert for Blackhill Enterprises in London’s Hyde Park, two days after Jones’ death; they decided to go ahead with the show as a tribute to him. Jagger began by reading an excerpt from Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem Adonaïs, an elegy written on the death of his friend John Keats. They released thousands of butterflies in memory of Jones[102] before opening their set with «I’m Yours and I’m Hers», a Johnny Winter number.[141] The concert, their first with new guitarist Mick Taylor, was performed in front of an estimated 250,000 fans.[102] A Granada Television production team filmed the performance, which was broadcast on British television as The Stones in the Park.[142] Blackhill Enterprises stage manager Sam Cutler introduced the Rolling Stones onto the stage by announcing: «Let’s welcome the Greatest Rock and Roll Band in the World.»[141][143]

Cutler repeated the introduction throughout their 1969 US tour.[144][145] The show also included the concert debut of their fifth US number 1 single, «Honky Tonk Women», which had been released the previous day.[146][147] In September 1969 the band’s second greatest hits album Through the Past, Darkly (Big Hits Vol. 2) was released,[148] featuring a poem in dedication to Jones on the inside cover.[149]

The Stones’ last album of the sixties was Let It Bleed, which reached number 1 in the UK and number 3 in the US.[150] It featured «Gimme Shelter» with guest lead female vocals by Merry Clayton (sister of Sam Clayton, of the American rock band Little Feat).[151] Other tracks include «You Can’t Always Get What You Want» (with accompaniment by the London Bach Choir, who initially asked that their name be removed from the album’s credits after apparently being «horrified» by the content of some of its other material, but later withdrew this request), «Midnight Rambler», as well as a cover of Robert Johnson’s «Love in Vain». Jones and Taylor are both featured on the album.[152]

Just after the US tour ended, the band performed at the Altamont Free Concert at the Altamont Speedway, about fifty miles (80 km) east of San Francisco. The Hells Angels biker gang provided security. A fan, Meredith Hunter, was stabbed and beaten to death by the Angels after they realised he was armed.[153] Part of the tour, and the Altamont concert, was documented in Albert and David Maysles’ film Gimme Shelter. In response to the growing popularity of bootleg recordings (in particular Live’r Than You’ll Ever Be, recorded during the 1969 tour), the album Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! was released in 1970. Critic Lester Bangs declared it the best-ever live album.[154] It reached number 1 in the UK and number 6 in the US.[155]

At the end of the decade the band appeared on the BBC’s review of the sixties music scene Pop Go the Sixties, performing «Gimme Shelter», which was broadcast live on 31 December 1969. The following year, the band wanted out of contracts with both Klein and Decca, but still owed them a Jagger/Richards–credited single. To get back at the label and fulfil their final contractual obligation, the band came up with the track «Schoolboy Blues»—deliberately making it as crude as they could in hopes of making it unreleasable.[156]

Amid contractual disputes with Klein, they formed their own record company, Rolling Stones Records. Sticky Fingers, released in March 1971, the band’s first album on their own label, featured an elaborate cover designed by Andy Warhol.[157] It was an Andy Warhol photograph of a man from the waist down in tight jeans featuring a functioning zipper.[158] When unzipped, it revealed the subject’s underwear.[159] In some markets an alternate cover was released because of the perceived offensive nature of the original at the time.[160]

Sticky Fingers‘ cover was the first to feature the logo of Rolling Stones Records, which effectively became the band’s logo. It consisted of a pair of lips with a lapping tongue. Designer John Pasche created the logo, following a suggestion by Jagger to copy the stuck-out tongue of the Hindu goddess Kali.[161] Critic Sean Egan has said of the logo,

Without using the Stones’ name, it instantly conjures them, or at least Jagger, as well as a certain lasciviousness that is the Stones’ own … It quickly and deservedly became the most famous logo in the history of popular music.[162]

The tongue and lips design was part of a package that in 2003 VH1 named the best album cover ever.[161] The logo has remained on all the Stones’ post-1970 albums and singles, in addition to their merchandise and stage sets.[163] The album contains one of their best-known hits, «Brown Sugar», and the country-influenced «Dead Flowers». «Brown Sugar» and «Wild Horses» were recorded at Alabama’s Muscle Shoals Sound Studio after the 1969 American tour.[164] The album continued the band’s immersion into heavily blues-influenced compositions; is noted for its «loose, ramshackle ambience»;[165] and marked Mick Taylor’s first full album with the band.[166][167] Sticky Fingers reached number 1 in both the UK and the US.[168]

In 1968, the Stones, acting on a suggestion by pianist Ian Stewart, put a control room in a van and created the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio so they would not be limited to the standard 9–5 operating hours of most recording studios.[169] The band lent the mobile studio to other artists,[169][170] including Led Zeppelin, who used it to record Led Zeppelin III (1970)[171] and Led Zeppelin IV (1971).[169][171] Deep Purple immortalised the mobile studio itself in the song «Smoke on the Water» with the line «the Rolling truck Stones thing just outside, making our music there».[172]

Following the release of Sticky Fingers, the Rolling Stones left England after receiving advice from their financial manager Prince Rupert Loewenstein. He recommended they go into tax exile before the start of the next financial year. The band had learned that they had not paid taxes for seven years, despite being assured that their taxes were taken care of; and the UK government was owed a relative fortune.[173] The Stones moved to the South of France, where Richards rented the Villa Nellcôte and sublet rooms to band members and their entourage.

Using the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio, they held recording sessions in the basement. They completed the new tracks, along with material dating as far back as 1969, at Sunset Studios in Los Angeles. The resulting double album, Exile on Main St., was released in May 1972, and reached number one in both the UK and the US.[174] Given an A+ grade by critic Robert Christgau[175] and disparaged by Lester Bangs—who reversed his opinion within months—Exile is now accepted as one of the Stones’ best albums.[176] The films Cocksucker Blues (never officially released) and Ladies and Gentlemen: The Rolling Stones (released in 1974) document the subsequent highly publicised 1972 North American Tour.[177]

The band’s double compilation, Hot Rocks 1964–1971, was released in 1971; it reached number 3 in the UK[178] and number 4 in the US.[179] It is certified Diamond in the US, having sold over 6 million copies, being certified 12× Platinum for being a double album, and spent over 347 weeks on the Billboard album chart.[180] In 1974, Bill Wyman was the first band member to release solo material, his album Monkey Grip.[181]

1972–1977: Critical fluctuations and Ronnie Wood[edit]

In 1972, members of the band set up a complex financial structure to reduce the amount of their taxes.[182][183] Their holding company, Promogroup, has offices in both the Netherlands and the Caribbean.[182][183] The Netherlands was chosen because it does not directly tax royalty payments. The band have been tax exiles ever since, meaning they can no longer use Britain as their main residence. Due to the arrangements with the holding company, the band has reportedly paid a tax of just 1.6% on their total earnings of £242 million over the past 20 years.[182][183]

In November 1972, the band began recording sessions in Kingston, Jamaica, for the album Goats Head Soup; it was released in 1973 and reached number 1 in both the UK and US.[184] The album, which contained the worldwide hit «Angie», was the first in a string of commercially successful, but critically tepidly received, studio albums.[185] The sessions for Goats Head Soup also produced unused material, most notably an early version of the popular ballad «Waiting on a Friend», which was not released until the Tattoo You LP nine years later.[186]

Another legal battle over drugs, dating back to their stay in France, interrupted the making of Goats Head Soup. Authorities had issued a warrant for Richards’ arrest, and the other band members had to return briefly to France for questioning.[187] This, along with Jagger’s 1967 and 1970 convictions on drug charges, complicated the band’s plans for their Pacific tour in early 1973: they were denied permission to play in Japan and almost banned from Australia. A European tour followed in September and October 1973, which bypassed France, coming, as it did, after Richards’ recent arrest in England on drug charges.[188]

The 1974 album It’s Only Rock ‘n Roll was recorded in the Musicland Studios in Munich, Germany; it reached number 2 in the UK and number 1 in the US.[189] Miller was not invited to return as the album’s producer because his «contribution level had dropped».[189] Jagger and Richards, credited as «the Glimmer Twins», produced the album.[190] Both the album and the single of the same name were hits.[191][192][193]

Near the end of 1974, Taylor began to lose patience after years of feeling like a «junior citizen in the band of jaded veterans».[194] The band’s situation made normal functioning complicated, with members living in different countries,[195] and legal barriers restricting where they could tour.[196] In addition, drug use was starting to affect Taylor’s and Richards’ productivity, and Taylor felt some of his own creative contributions were going unrecognised.[197] At the end of 1974, Taylor quit the Rolling Stones.[198] Taylor said in 1980, «I wanted to broaden my scope as a guitarist and do something else … I wasn’t really composing songs or writing at that time. I was just beginning to write, and that influenced my decision … There are some people who can just ride along from crest to crest; they can ride along somebody else’s success. And there are some people for whom that’s not enough. It really wasn’t enough for me.»[199]

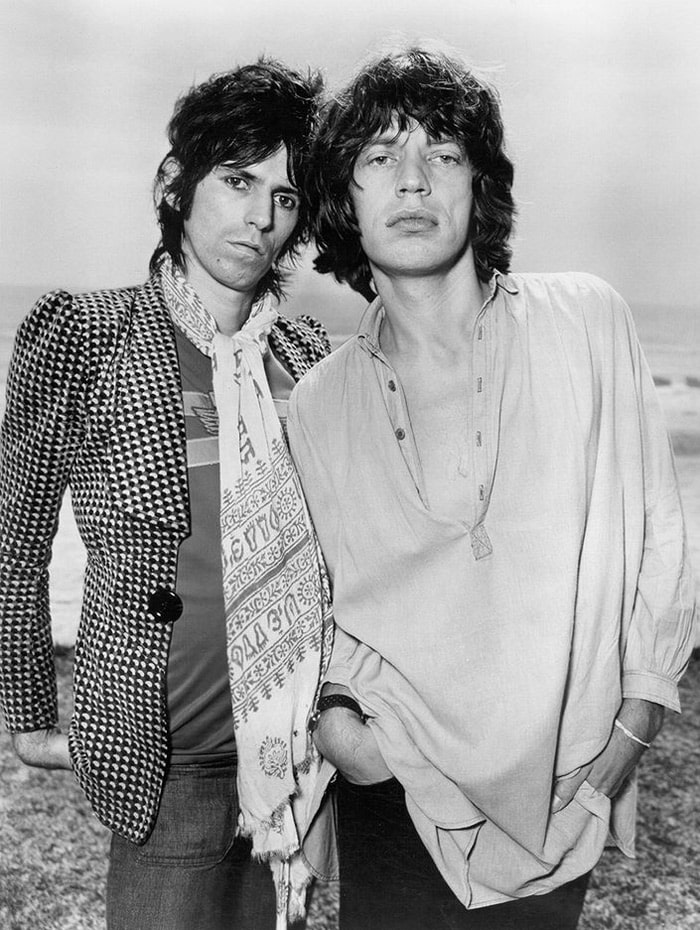

Ronnie Wood (left) on his first tour with the Rolling Stones, taken with Mick Jagger (right) in Chicago, 1975

The Stones needed a new guitarist, and the recording sessions in Munich for the next album, Black and Blue (1976) (number 2 in the UK, number 1 in the US), provided an opportunity for some guitarists hoping to join the band to work while trying out. Guitarists as stylistically disparate as Peter Frampton and Jeff Beck were auditioned, as well as Robert A. Johnson and Shuggie Otis. Both Beck and Irish blues rock guitarist Rory Gallagher later claimed they had played without realising they were being auditioned. American session players Wayne Perkins and Harvey Mandel also tried out, but Richards and Jagger preferred for the band to remain purely British. When Ronnie Wood auditioned, everyone agreed he was the right choice.[200] He had already recorded and played live with Richards, and had contributed to the recording and writing of the track «It’s Only Rock ‘n Roll». He had declined Jagger’s earlier offer to join the Stones, because of his commitment to Faces, saying «that’s what’s really important to me».[201] Faces’ lead singer Rod Stewart went so far as to say he would take bets that Wood would not join the Stones.[201]

In 1975, Wood officially joined the Rolling Stones for their upcoming Tour of the Americas, which was a contributing factor in the disbandment of Faces. Unlike the other band members, however, Wood was a salaried employee, which remained the case until the early 1990s, when he finally joined the Stones’ business partnership.[202]

The 1975 Tour of the Americas kicked off in New York City with the band performing on a flatbed trailer being pulled down Broadway. The tour featured stage props including a giant phallus and a rope on which Jagger swung out over the audience. In June of that year, the Stones’ Decca catalogue was purchased by Klein’s ABKCO label.[203][204] In August 1976, the Stones played Knebworth in England in front of 200,000—their largest audience to date—and finished their set at 7 a.m.[205] Jagger had booked live recording sessions at the El Mocambo, a club in Toronto, to produce a long-overdue live album, 1977’s Love You Live,[206] the first Stones live album since Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out![207] It reached No. 3 in the UK and No. 5 in the US.[206]

Richards’ addiction to heroin delayed his arrival in Toronto; the other members had already arrived. On 24 February 1977, when Richards and his family flew in from London, they were temporarily detained by Canadian customs after Richards was found in possession of a burnt spoon and hash residue. Three days later, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, armed with an arrest warrant for Anita Pallenberg, discovered 22 grams (0.78 oz) of heroin in Richards’ room.[208] He was charged with importing narcotics into Canada, an offence that carried a minimum seven-year sentence.[209] The Crown prosecutor later conceded that Richards had procured the drugs after his arrival.[210]

Despite the incident, the band played two shows in Toronto, only to cause more controversy when Margaret Trudeau, then-wife of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, was seen partying with the band after one show. The band’s shows were not advertised to the public. Instead, the El Mocambo had been booked for the entire week by April Wine for a recording session. 1050 CHUM, a local radio station, ran a contest for free tickets to see April Wine. Contest winners who selected tickets for Friday or Saturday night were surprised to find the Rolling Stones playing.[211]

On 4 March, Richards’ partner Anita Pallenberg pleaded guilty to drug possession and incurred a fine in connection with the original airport incident.[211] The drug case against Richards dragged on for over a year. Ultimately, he received a suspended sentence and was ordered to play two charity concerts to benefit the Canadian institute for the blind in Oshawa;[210] both shows featured the Rolling Stones and the New Barbarians, a group that Wood had put together to promote his latest solo album, which Richards also joined. This episode strengthened Richards’ resolve to stop using heroin.[102] It also ended his relationship with Pallenberg, which had become strained since the death of their third child, Tara. Pallenberg was unable to curb her heroin addiction as Richards struggled to get clean.[212] While Richards was settling his legal and personal problems, Jagger continued his jet-set lifestyle. He was a regular at New York’s Studio 54 disco club, often in the company of model Jerry Hall. His marriage to Bianca Jagger ended in 1977, although they had long been estranged.[213]

Although the Rolling Stones remained popular through the early 1970s, music critics had begun to grow dismissive of the band’s output, and record sales failed to meet expectations.[81] By the mid-1970s, after punk rock became influential, many people had begun to view the Rolling Stones as an outdated band.[214]

1978–1982: Commercial peak[edit]

The group’s fortunes changed in 1978, after the band released Some Girls, which included the hit single «Miss You», the country ballad «Far Away Eyes», «Beast of Burden», and «Shattered». In part as a response to punk, many songs, particularly «Respectable», were fast, basic, guitar-driven rock and roll,[215] and the album’s success re-established the Rolling Stones’ immense popularity among young people. It reached number 2 in the UK and number 1 in the US.[216] Following the 1978 US Tour, the band guested on the first show of the fourth season of the TV series Saturday Night Live. Following the success of Some Girls, the band released their next album, Emotional Rescue, in mid-1980.[217] During recording sessions for the album, a rift between Jagger and Richards slowly developed. Richards wanted to tour in the summer or autumn of 1980 to promote the new album. Much to his disappointment, Jagger declined.[217] Emotional Rescue hit the top of the charts on both sides of the Atlantic[218] and the title track reached number 3 in the US.[217]

The Rolling Stones performing in December 1981

In early 1981, the group reconvened and decided to tour the US that year, leaving little time to write and record a new album, as well as to rehearse for the tour. That year’s resulting album, Tattoo You, featured a number of outtakes from other recording sessions, including lead single «Start Me Up», which reached number 2[219] in the US and ranked number 22 on Billboard’s Hot 100 year-end chart. Two songs («Waiting on a Friend» (US number 13) and «Tops») featured Mick Taylor’s unused rhythm guitar tracks, while jazz saxophonist Sonny Rollins played on «Slave», «Neighbours», and «Waiting on a Friend».[220] The album reached number 2 in the UK and number 1 in the US.[221]

The Rolling Stones reached number 20 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1982 with «Hang Fire». Their 1981 American Tour was their biggest, longest, and most colourful production to date. It was the highest-grossing tour of that year.[222] It included a concert at Chicago’s Checkerboard Lounge with Muddy Waters, in one of his last performances before his death in 1983.[223] Some of the shows were recorded. This resulted in the 1982 live album Still Life (American Concert 1981) which reached number 4 in the UK and number 5 in the US,[224] and the 1983 Hal Ashby concert film Let’s Spend the Night Together, filmed at Sun Devil Stadium in Tempe, Arizona and the Brendan Byrne Arena in the Meadowlands, New Jersey.[225]

In mid-1982, to commemorate their 20th anniversary, the Rolling Stones took their American stage show to Europe. The European tour was their first in six years and used a similar format to the American tour. The band were joined by former Allman Brothers Band keyboardist Chuck Leavell, who continues to perform and record with them. By the end of the year, the Stones had signed a new four-album recording deal with a new label, CBS Records, for a reported $50 million, then the biggest record deal in history.[227]

1983–1988: Band turmoil and solo projects[edit]

Before leaving Atlantic, the Rolling Stones released Undercover in late 1983. It reached number 3 in the UK and number 4 in the US.[228] Despite good reviews and the peak Top Ten position of the title track, the record sold below expectations and there was no tour to support it. Subsequently, the Stones’ new marketer/distributor CBS Records took over distributing their Atlantic catalogue.[227]

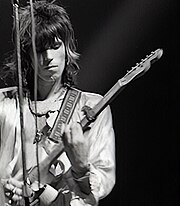

Richards and Wood during a Stones concert in Turin, Italy, in 1982

By this time, the Jagger/Richards rift had grown significantly. To Richards’ annoyance, Jagger signed a solo deal with CBS Records and spent much of 1984 writing songs for his first album. He also declared his growing lack of interest in the Rolling Stones.[229] By 1985, Jagger was spending more time on solo recordings. Much of the material on 1986’s Dirty Work was generated by Richards, with more contributions from Wood than on previous Rolling Stones albums. It was recorded in Paris, and Jagger was often absent from the studio, leaving Richards to keep the recording sessions moving forward.[230]

In June 1985, Jagger teamed up with David Bowie for «Dancing in the Street», which was recorded for the Live Aid charity movement.[231] This was one of Jagger’s first solo performances, and the song reached number 1 in the UK, and number 7 in the US.[232][92] In December 1985, Ian Stewart died of a heart attack.[233] The Rolling Stones played a private tribute concert for him at London’s 100 Club in February 1986.[233] Two days later they were presented with a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.[234]

Dirty Work was released in March 1986 to mixed reviews, reaching number 4 in both the US and UK.[235] It was the Stones first album for CBS with an outside producer, Steve Lillywhite.[236] With relations between Richards and Jagger at an all-time low, Jagger refused to tour to promote the album and instead undertook a solo tour, where he performed some Rolling Stones songs.[237][238] As a result of their animosity, the Stones almost broke up.[237] Jagger’s solo records, She’s the Boss (1985), which reached number 6 in the UK and number 13 in the US, and Primitive Cool (1987), which reached number 26 in the UK and number 41 in the US, met with moderate commercial success. In 1988, with the Rolling Stones mostly inactive, Richards released his first solo album, Talk Is Cheap, which reached number 37[239] in the UK and No. 24 in the US.[240] It was well received by fans and critics, and was certified Gold in the US.[241] Richards has subsequently referred to this late-80s period, when the two were recording solo albums with no obvious reunion of the Stones in sight, as «World War III».[242][243] The following year, 25×5: The Continuing Adventures of the Rolling Stones, a documentary spanning the band’s career, was released for their 25th anniversary.[244]

1989–1999: Comeback and record-breaking tours[edit]

The band’s 1994 album Voodoo Lounge was certified multi-platinum and its award (left) is displayed at the Museo del Rock in Madrid; Richards (right) performs onstage in Rio de Janeiro during the tour accompanying the album.

In early 1989, the Stones, including Mick Taylor and Ronnie Wood, as well as Brian Jones and Ian Stewart (posthumously), were inducted into the American Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[81] Jagger and Richards set aside their animosity and went to work on a new Rolling Stones album, Steel Wheels. Heralded as a return to form, it included the singles «Mixed Emotions» (US number 5), «Rock and a Hard Place» (US number 23) and «Almost Hear You Sigh». The album also included «Continental Drift», which the Rolling Stones recorded in Tangier, Morocco, in 1989, with the Master Musicians of Jajouka led by Bachir Attar, coordinated by Tony King and Cherie Nutting. Nigel Finch produced the BBC documentary film The Rolling Stones in Morocco.[245] The album reached number 2 in the UK and number 3 in the US.[246]

The Steel Wheels/Urban Jungle Tour was the band’s first world tour in seven years and their biggest stage production to date. Opening acts included Living Colour and Guns N’ Roses. Recordings from the tour include the 1991 concert album Flashpoint, which reached number 6 in the UK and number 16 in the US,[247] and the concert film Live at the Max released in 1991.[248] The tour was Bill Wyman’s last. After years of deliberation he decided to leave the band, although his departure was not made official until January 1993.[249] He then published Stone Alone, an autobiography based on scrapbooks and diaries he had kept since the band’s early days. A few years later he formed Bill Wyman’s Rhythm Kings and began recording and touring again.[250]

After the successes of the Steel Wheels/Urban Jungle tours, the band took a break. Watts released two jazz albums; Wood recorded his fifth solo album, the first in 11 years, called Slide On This; Wyman released his fourth solo album; Richards released his second solo album in late 1992, Main Offender, and did a small tour, including big concerts in Spain and Argentina.[251][252] Jagger got good reviews and sales with his third solo album, Wandering Spirit, which reached number 12 in the UK[253] and number 11 in the US.[254] The album sold more than two million copies worldwide, being certified Gold in the US.[241]

After Wyman’s departure, the Rolling Stones’ new distributor/record label, Virgin Records, remastered and repackaged the band’s back catalogue from Sticky Fingers to Steel Wheels, except for the three live albums. They issued another hits compilation in 1993 entitled Jump Back, which reached number 16 in the UK and number 30 in the US.[255] By 1993, the Stones were ready to start recording another studio album. Charlie Watts recruited bassist Darryl Jones, a former sideman of Miles Davis, and Sting, as Wyman’s replacement for 1994’s Voodoo Lounge. Jones continues to perform with the band as their touring and session bassist. The album met with positive reviews and strong sales, going double platinum in the US. Reviewers took note and credited the album’s «traditionalist» sounds to the Rolling Stones’ new producer Don Was.[256] Voodoo Lounge won the Grammy Award for Best Rock Album at the 1995 Grammy Awards.[257] It reached number 1 in the UK and number 2 in the US.[258]

The accompanying Voodoo Lounge Tour lasted into the following year and grossed $320 million, becoming the world’s highest-grossing tour at the time.[259] Mostly acoustic numbers from various concerts and rehearsals made up Stripped which reached number 9 in the UK and the US.[260] It featured a cover of Bob Dylan’s «Like a Rolling Stone», as well as infrequently played songs such as «Shine a Light»,[261] «Sweet Virginia»,[261] and «The Spider and the Fly».[262] On 8 September 1994, the Stones performed their new song «Love Is Strong» and «Start Me Up» at the 1994 MTV Video Music Awards at Radio City Music Hall in New York.[263] The band received the Lifetime Achievement Award at the ceremony.[263]

Jagger in Chile during the Voodoo Lounge Tour

The Rolling Stones were the first major recording artists to broadcast a concert over the Internet; a 20-minute video was broadcast on 18 November 1994 using the Mbone at 10 frames per second. The broadcast, engineered by Thinking Pictures and financed by Sun Microsystems, was one of the first demonstrations of streaming video; while it was not a true webcast, it introduced many to the technology.[264]

The Rolling Stones ended the 1990s with the album Bridges to Babylon, released in 1997 to mixed reviews.[265] It reached number 6 in the UK and number 3 in the US.[266] The video of the single «Anybody Seen My Baby?» featured Angelina Jolie as guest[267] and was given steady rotation on both MTV and VH1.[268] Sales were roughly equal to those of previous records (about 1.2 million copies sold in the US). The subsequent Bridges to Babylon Tour, which crossed Europe, North America, and other destinations, proved that the band remained a strong live attraction. Once again, a live album was recorded during the tour, No Security; only this time all but two songs («Live With Me» and «The Last Time») were previously unreleased on live albums. The album reached number 67 in the UK[269] and number 34 in the US.[270] In 1999, the Rolling Stones staged the No Security Tour in the US and continued the Bridges to Babylon tour in Europe.[271]

2000–2011: A Bigger Bang and continued success[edit]

In late 2001, Mick Jagger released his fourth solo album, Goddess in the Doorway. It met with mixed reviews;[272] it reached number 44 in the UK[273] and number 39 in the US. A month after the September 11 attacks, Jagger, Richards, and a backing band took part in The Concert for New York City, performing «Salt of the Earth» and «Miss You».[274] In 2002, the Stones released Forty Licks, a greatest hits double album, to mark forty years as a band. The collection contained four new songs recorded with the core band of Jagger, Richards, Watts, Wood, Leavell, and Jones. The album has sold more than 7 million copies worldwide. It reached number 2 in both the US and UK.[275] The same year, Q magazine named the Rolling Stones one of the 50 Bands To See Before You Die.[276] The Stones headlined the Molson Canadian Rocks for Toronto concert in Toronto, Canada, to help the city—which they had used for rehearsals since the Voodoo Lounge tour—recover from the 2003 SARS epidemic; an estimated 490,000 people attended the concert.[277]

On 9 November 2003, the band played their first concert in Hong Kong, as part of the Harbour Fest celebration, in support of its SARS-affected economy. The same month, the band licensed the exclusive rights to sell the new four-DVD boxed set Four Flicks, recorded on their recent world tour, to the US Best Buy chain of stores. In response, some Canadian and US music retail chains (including HMV Canada and Circuit City) pulled Rolling Stones CDs and related merchandise from their shelves and replaced it with signs explaining why.[278] In 2004, a double live album of the Licks Tour, Live Licks, was released and certified gold in the US.[241] It reached number 2 in both the UK and US.[279] In November 2004, the Rolling Stones were among the inaugural inductees into the UK Music Hall of Fame.[280]

The band’s first new album in almost eight years, A Bigger Bang, was released on 6 September 2005 to positive reviews, including a glowing write-up in Rolling Stone magazine.[281] The album reached number 2 in the UK and number 3 in the US.[282] The single «Streets of Love» reached the top 15 in the UK.[283] The album included the political «Sweet Neo Con», Jagger’s criticism of American Neoconservatism.[284] Richards was initially worried about a political backlash in the US,[284] but did not object to the lyrics, saying «I just didn’t want it to become some peripheral distractions/political storm in a tea-cup sort of thing.»[285] The subsequent A Bigger Bang Tour began in August 2005, and included North America, South America, and East Asia. In February 2006, the group played the half-time show of Super Bowl XL in Detroit, Michigan. By the end of 2005, the Bigger Bang tour had set a record of $162 million in gross receipts, breaking the North American mark set by the band in 1994. On 18 February 2006, the band played a free concert to over one million people at the Copacabana beach in Rio de Janeiro—one of the largest rock concerts of all time.[286]

After performances in Japan, China, Australia, and New Zealand in March and April 2006, the Stones’ tour took a scheduled break before proceeding to Europe. During the break, Keith Richards was hospitalised in New Zealand for cranial surgery after a fall from a tree on Fiji, where he had been on holiday. The incident led to a six-week delay in launching the European leg of the tour.[287][288] In June 2006, it was reported that Ronnie Wood was continuing his alcohol abuse rehabilitation programme,[289][290] but this did not affect the rearranged European tour schedule. Mick Jagger’s throat problems forced the cancellation of three shows and the rescheduling of several others that fall.[291] The Stones returned to North America for concerts in September 2006, and returned to Europe on 5 June 2007. By November 2006, the Bigger Bang tour had been declared the highest-grossing tour of all time.[292]

Martin Scorsese filmed the Stones performances at New York City’s Beacon Theatre on 29 October and 1 November 2006 for the documentary film, Shine a Light, released in 2008. The film features guest appearances by Buddy Guy, Jack White, and Christina Aguilera.[293] An accompanying soundtrack, also titled Shine a Light, was released in April 2008 and reached number 2 in the UK and number 11 in the US.[294] The album’s debut at number 2 on the UK charts was the highest position for a Rolling Stones concert album since Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! The Rolling Stones in Concert in 1970. At the Beacon Theatre show, music executive Ahmet Ertegun fell and later died from his injuries.[295]

The Rolling Stones in 2008 (from left to right: Watts, Wood, Richards, Jagger) at the Berlin Film Festival’s world premiere of Martin Scorsese’s documentary film Shine a Light

The band toured Europe throughout June and August 2007. 12 June 2007 saw the release of the band’s second four-disc DVD set: The Biggest Bang, a seven-hour film featuring their shows in Austin, Rio de Janeiro, Saitama, Shanghai, and Buenos Aires, along with extras. On 10 June 2007, the band performed their first gig at a festival in 30 years,[f] at the Isle of Wight Festival, to a crowd of 65,000, and were joined onstage by Amy Winehouse.[296] On 26 August 2007, they played their last concert of the Bigger Bang tour at the O2 Arena in London. At the conclusion of the tour, the band had grossed a record-setting $558 million[297] and were listed in the 2007 edition of Guinness World Records.[298] On 12 November 2007, ABKCO released Rolled Gold: The Very Best of the Rolling Stones, a double-CD remake of the 1975 compilation Rolled Gold.[299] In July 2008, the Rolling Stones left EMI to sign with Vivendi’s Universal Music, taking with them their catalogue stretching back to Sticky Fingers. New music released by the band while under this contract was to be issued through Universal’s Polydor label.[300]

During the autumn, Jagger and Richards worked with producer Don Was to add new vocals and guitar parts to ten unfinished songs from the Exile on Main St. sessions. Jagger and Mick Taylor also recorded a session together in London, where Taylor added a new guitar track to what would be the expanded album’s single, «Plundered My Soul».[301] On 17 April 2010, the band released a limited edition 7-inch vinyl single of the previously unreleased track «Plundered My Soul», as part of Record Store Day. The track, part of the group’s 2010 re-issue of Exile on Main St., was combined with «All Down the Line» as its B-side.[302] The band appeared at the Cannes Festival for the premiere of the documentary Stones in Exile (directed by Stephen Kijak[303]) about the recording of the album Exile on Main St.[303] On 23 May, the re-issue of Exile on Main St. reached number 1 on the UK charts, almost 38 years to the week after it first occupied that position. The band became the first act to see a classic work return to number 1 decades after it was first released.[304] In the US, the album re-entered the charts at number 2.[305]

Loewenstein proposed to the band that they wind down their recording and touring activity and sell off their assets. The band disagreed, and that year Loewenstein parted from the band[306] after four decades as their manager, later writing the memoir A Prince Among Stones.[307] Joyce Smyth, a lawyer who had long been working for the Stones, took over as their full-time manager in 2010.[308][309] Smyth would go on to win Top Manager in the 2019 Billboard Live Music Awards.[310]

In October 2010, the Stones released Ladies and Gentlemen: The Rolling Stones to cinemas and later to DVD. A digitally remastered version of the film was shown in select cinemas across the United States. Although originally released to cinemas in 1974, it had never been available for home release, apart from bootleg recordings.[311] In October 2011, the Stones released The Rolling Stones: Some Girls Live In Texas ’78 to cinemas. A digitally remastered version of the film was shown in select cinemas across the US. This live performance was recorded during one show in Ft. Worth, Texas, in support of their 1978 US Tour and their album Some Girls. The film was released (on DVD/Blu-ray Disc) on 15 November 2011.[312] On 21 November, the band reissued Some Girls as a 2-CD deluxe edition. The second CD included twelve previously unreleased tracks (except «So Young», which was a B-side to «Out of Tears») from the sessions, with mostly newly recorded vocals by Jagger.[313]

2012–2016: 50th anniversary, documentary and Blue & Lonesome[edit]

The 50 & Counting tour stage (left) had lips that were capable of being both inflated and deflated throughout the show. The following year, the band played Hyde Park (right) for the first time since 1969; Mick Taylor performed with the band for the first time since 1974.

The Rolling Stones celebrated their 50th anniversary in the summer of 2012 by releasing the book The Rolling Stones: 50.[314] A new take on the band’s lip-and-tongue logo, designed by Shepard Fairey, was also revealed and used during the celebrations.[315] Jagger’s brother Chris performed a gig at The Rolling Stones Museum in Slovenia, in conjunction with the celebrations.[316]

The documentary Crossfire Hurricane, directed by Brett Morgen, was released in October 2012. He conducted approximately fifty hours of interviews for the film, including extensive interviews with Wyman and Taylor.[317] This was the first official career-spanning documentary since 25×5: The Continuing Adventures of the Rolling Stones, filmed for their 25th anniversary in 1989.[244] A new compilation album, GRRR!, was released on 12 November. Available in four different formats, it included two new tracks, «Doom and Gloom» and «One More Shot», recorded at Studio Guillaume Tell in Paris, France, in the last few weeks of August 2012.[318] The album went on to sell over two million copies worldwide.[283] The music video for «Doom and Gloom», featuring Noomi Rapace, was released on 20 November.[319][320]

In November 2012, the Stones began their 50 & Counting… tour at London’s O2 Arena, where they were joined by Jeff Beck.[321] At their second show, in London, Eric Clapton and Florence Welch joined the group onstage.[322] The third anniversary concert took place on 8 December at the Barclays Center, Brooklyn, New York.[322] The last two dates were at the Prudential Center in Newark, New Jersey, on 13 and 15 December. Bruce Springsteen and blues–rock band the Black Keys joined the band on the final night.[322][323] The stage on this tour was designed so that the lips could «inflate and deflate during different parts of the show.»[324] The band also played two songs at 12-12-12: The Concert for Sandy Relief.[325]

The Stones played nineteen shows in the US in spring 2013 with various guest stars, including Katy Perry[326] and Taylor Swift,[327] before returning to the UK. In June, the band performed at the 2013 Glastonbury Festival.[328] They returned to Hyde Park in July[g] and performed the same set list as their 1969 concert at the venue.[330] Hyde Park Live, a live album recorded at the two Hyde Park gigs on 6 and 13 July, was released exclusively as a digital download through iTunes later that month.[331] An award-winning[332] live DVD, Sweet Summer Sun: Live in Hyde Park, was released on 11 November.[333]

In February 2014, the band embarked on their 14 On Fire tour, scheduled for the Middle East, Asia, Australia, and Europe and to go until the summer.[334] On 17 March, Jagger’s long-time partner L’Wren Scott died suddenly, resulting in the cancellation and rescheduling of the opening tour dates to October.[335] On 4 June, the Rolling Stones performed for the first time in Israel. Haaretz described the concert as being «Historic with a capital H».[336] In a 2015 interview with Jagger, when asked if retirement crosses his mind he stated, «Nah, not in the moment. I’m thinking about what the next tour is. I’m not thinking about retirement. I’m planning the next set of tours, so the answer is really, ‘No, not really.‘«[337]

The Stones in Cuba in March 2016. A spokesman for the band called it «the first open air concert in Cuba by a British rock band».[338]

The Stones embarked on their Latin American tour in February 2016.[339] On 25 March, the band played a bonus show, a free open-air concert in Havana, Cuba, which was attended by an estimated 500,000 concert-goers.[338] In June of that year, the Rolling Stones released Totally Stripped, an expanded and reconceived edition of Stripped, in multiple formats.[340][341] Their concert on 25 March 2016 in Cuba was commemorated in the film Havana Moon. It premiered on 23 September for one night only in more than a thousand theatres worldwide.[342][343] The film Olé Olé Olé: A Trip Across Latin America, a documentary of their 2016 Latin America tour,[344] premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival on 16 September 2016;[345] it came out on DVD and Blu-ray on 26 May 2017.[345][346] The Stones performed at the Desert Trip festival held in Indio, California, playing two nights, 7 and 14 October, the same nights as Bob Dylan.[347]

The band released Blue & Lonesome on 2 December 2016. The album consisted of 12 blues covers of artists such as Howlin’ Wolf, Jimmy Reed, and Little Walter.[348][349] Recording took place in British Grove Studios, London, in December 2015, and featured Eric Clapton on two tracks.[350] The album reached number 1 in the UK, the second-highest opening sales week for an album that year.[351] It also debuted at number 4 on the Billboard 200.[352]

2017–present: No Filter Tour, Jagger’s surgery, new album and Watts’ death[edit]

In July 2017, the Toronto Sun reported that the Stones were getting ready to record their first album of original material in more than a decade,[353] but as of 2021 it had not been released and was further delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[354] On Air, a collection of 18 recordings the band performed on the BBC between 1963 and 1965, was released in December 2017. The album featured eight songs the band had never recorded or released commercially.[355]

In May 2017, the No Filter Tour was announced, with fourteen shows in twelve different venues across Europe in September and October of the same year.[356] It was later extended to go from May to July 2018, adding fourteen new dates across the UK and Europe, making it the band’s first UK tour since 2006.[357] In November 2018, the Stones announced plans to bring the No Filter Tour to US stadiums in 2019, with 13 shows set to run from April to June.[358] In March 2019, it was announced that Jagger would be undergoing heart valve replacement surgery, forcing the band to postpone the 17-date North American leg of their No Filter Tour.[359] On 4 April 2019, it was announced that Jagger had completed his heart valve procedure in New York, was recovering (in hospital) after a successful operation, and could be released in the following few days.[360] On 16 May, the Rolling Stones announced that the No Filter Tour would resume on 21 June with the 17 postponed dates rescheduled up to the end of August.[361] In March 2020, the No Filter Tour was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[362]

The Rolling Stones—featuring Jagger, Richards, Watts, and Wood at their homes—were one of the headline acts on Global Citizen’s One World: Together at Home on-line and on-screen concert on 18 April 2020, a global event featuring dozens of artists and comedians to support frontline healthcare workers and the World Health Organization during the COVID-19 pandemic.[363] On 23 April, Jagger announced through his Facebook page the release (the same day at 5pm BST) of the single «Living in a Ghost Town», a new Rolling Stones song recorded in London and Los Angeles in 2019 and finished in isolation (part of the new material that the band were recording in the studio before the COVID-19 lockdown), a song that the band «thought would resonate through the times we’re living in» and their first original one since 2012.[364] The song reached number 1 on the German Singles Chart, the first time the Stones had reached the top spot in 52 years, and making them the oldest artists ever to do so.[365]

The Rolling Stones performing at BST Hyde Park 2022.

The band’s 1973 album Goats Head Soup was reissued on 4 September 2020 and featured previously unreleased outtakes: such as «Criss Cross», which was released as a single and music video on 9 July 2020; «Scarlet», featuring Jimmy Page; and «All the Rage».[366] On 11 September 2020, the album topped the UK Albums Chart as the Rolling Stones became the first band to top the chart across six different decades.[367]

In August 2021, it was announced that Watts would undergo an unspecified medical procedure and would not perform on the remainder of the No Filter tour; the longtime Stones associate Steve Jordan filled in as drummer.[368][369] Watts died on 24 August 2021, at the age of 80, in a London hospital with his family around him.[370][371] For 10 days, the contents of the Rolling Stones’ official website were replaced with a picture of Watts, in his memory.[372] On 27 August, the band’s social media accounts shared a montage of pictures and videos of Watts.[373] Going forward, the Rolling Stones would show pictures and videos of Watts at the beginning of each concert on the No Filter Tour. The short segment is roughly a minute long and plays a simple drum track by Watts.[374] They became the highest-earning live act of 2021, surpassing Taylor Swift; since 2018 the two have traded the top two spots.[375][376] The band began a new tour in 2022, with Jordan on drums.[377]

Following reports in February 2023 that former Beatles Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr would appear on their yet-named new album,[378] representatives for the band confirmed that McCartney will appear but stated that Starr would not. This will mark the first time that McCartney and the Stones have collaborated on a studio album.[379]

Musical development[edit]

A copy of «Micawber», Keith Richards’ signature Telecaster model, in the Fender Guitar Factory Museum

The Rolling Stones have assimilated various musical genres into their own collective sound. Throughout the band’s career, their musical contributions have been marked by a continual reference to and reliance on musical styles including blues, psychedelia, R&B, country, folk, reggae, dance, and world music—exemplified by Jones’ collaboration with the Master Musicians of Jajouka—as well as traditional English styles that use stringed instruments such as harps. Brian Jones experimented with the use of non-traditional instruments, such as the sitar and slide guitar, in their early days.[380][381] The group started out covering early rock ‘n’ roll and blues songs, and have never stopped playing live or recording cover songs.[382]