Here’s an evolutionary talking point: Two new studies quantify parts of the mechanism by which frequently used words change slowly over many millennia whereas rarely used words more rapidly take on new forms.

In fact, frequency of word usage exerts a “lawlike” influence on the rapidity of language evolution, the research teams conclude in the Oct. 11 Nature. This discovery offers a new tool for retracing the history of major language families, reconstructing ancient tongues, and predicting which words will undergo future alterations.

“We expect all languages to diverge initially in the least frequently used parts of their vocabulary,” says evolutionary biologist Mark Pagel of the University of Reading in England.

Pagel’s group focused on Indo-European languages. Some words for the same meanings differ strikingly across the more than 100 languages and dialects of that family, while others take similar forms.

The researchers first determined 200 basic vocabulary meanings in 87 Indo-European languages spoken during the past 6,000 to 10,000 years. They then applied a statistical technique to modern-language data in order to estimate the spoken frequencies of the corresponding words in English, Spanish, Russian, and Greek.

Among those 200 meanings, commonly used words—such as who or night, and terms for numbers—evolved slowly and sounded similar in different languages. Such words undergo no more than one wholesale shift to a new form every 10,000 years, the scientists propose.

Subscribe to Science News

Get great science journalism, from the most trusted source, delivered to your doorstep.

In contrast, less frequently used words—such as dirty, turn, and guts—evolved more rapidly and sounded different across languages. These types of words change forms up to nine times every 10,000 years, according to the investigators.

In the second new study, Harvard University genomics graduate student Erez Lieberman and his coworkers measured the rate at which English verbs have become regular—using the suffix “ed” to signify past tense—over the past 1,200 years. That linguistic period begins with Old English, includes Middle English around 800 years ago, and ends with English as it is spoken today.

The team compiled a list of 177 irregular verbs in Old English. Of that number, 145 remained irregular in Middle English and 98 are still irregular today.

The researchers then calculated the frequency of each verb’s usage in Modern English and estimated frequencies for the two older tongues. They determined that an irregular verb used 100 times as often as another in daily conversation takes 10 times as long to become regular as the less-spoken verb does.

If current trends continue, only 83 of the 177 verbs studied will be irregular in 500 years, the researchers predict. They predict that the next irregular verb to regularize will be wed, meaning that just-married couples will no longer be “newly wed” but will have blissfully “wedded.”

“Our results indicate that languages can evolve in such an orderly fashion that simple mathematical descriptions capture their behavior,” Lieberman says. “A language’s irregularities reveal the mechanisms shaping its evolution.”

The use of sophisticated statistical methods to quantify how words evolve on the basis of the frequency of their use “is an important step forward,” remarks psycholinguist W. Tecumseh Fitch of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland.

From the Nature Index

Paid Content

LECTURE 1

1.1.Lexicology as a branch of linguistics. Its interrelations with other sciences

1.2.The word as the fundamental object of lexicology. The morphological structure of the English word

1.3.Inner structure of the word composition. Word building. The morpheme and its types. Affixation

1.1.Lexicology as a branch of linguistics. Its interrelations with other sciences. Lexicology (from Gr lexis “word” and logos “learning”) is a part of linguistics dealing with the vocabulary of a language and the properties of words as the main units of the language. It also studies all kinds of semantic grouping and semantic relations: synonymy, antonymy, hyponymy, semantic fields, etc.

In this connection, the term vocabulary is used to denote a system formed by the sum total of all the words and word equivalents that the language possesses. The term word denotes the basic unit of a given language resulting from the association of a particular meaning with a particular group of sounds capable of a particular grammatical employment. A word therefore is at the same time a semantic, grammatical and phonological unit. So, the subject-matter of lexicology is the word, its morphemic structure, history and meaning.

There are several branches of lexicology. The general study of words and vocabulary, irrespective of the specific features of any particular language, is known as general lexicology. Linguistic phenomena and properties common to all languages are referred to as language universals. Special lexicology focuses on the description of the peculiarities in the vocabulary of a given language. A branch of study called contrastive lexicology provides a theoretical foundation on which the vocabularies of different languages can be compared and described, the correlation between the vocabularies of two or more languages being the scientific priority.

Vocabulary studies include such aspects of research as etymology, semasiology and onomasiology.

The evolution of a vocabulary forms the object of historical lexicology or etymology (from Gr. etymon “true, real”), discussing the origin of various words, their change and development, examining the linguistic and extra-linguistic forces that modify their structure, meaning and usage.

Semasiology (from Gr. semasia “signification”) is a branch of linguistics whose subject-matter is the study of word meaning and the classification of changes in the signification of words or forms, viewed as normal and vital factors of any linguistic development. It is the most relevant to polysemy and homonymy.

Onomasiology is the study of the principles and regularities of the signification of things / notions by lexical and lexico-phraseological means of a given language. It has its special value in studying dialects, bearing an obvious relevance to synonymity.

Descriptive lexicology deals with the vocabulary of a language at a given stage of its evolution. It studies the functions of words and their specific structure as a characteristic inherent in the system. In the English language the above science is oriented towards the English word and its morphological and semantic structures, researching the interdependence between these two aspects. These structures are identified and distinguished by contrasting the nature and arrangement of their elements.

Within the framework of lexicology, both synchronic (Gr syn “together”, “with” and chronos “time”) and diachronic or historical (Gr dia “through”) approaches to the language suggested by the Swiss philologist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) are effectively realized. Language is the reality of thought, and thought develops together with the development of a society, thus the language and its vocabulary should be studied in the light of social history. Every new phenomenon in a human society in general, which is of any importance for communication, finds a reflection in the corresponding vocabulary. A word is considered to be a generalized reflection of reality; therefore, it is impossible to understand its development if one is ignorant of the changes in socio-political or everyday life, manners and culture, science of a linguoculture it serves to reflect. These extra-linguistic forces influencing the evolution of words are taken into the priority consideration in modern lexicology.

With regard to special lexicology the synchronic approach is concerned with the vocabulary of a language as it exists at a certain time (e.g., a course in Modern English Lexicology). The diachronic approach in terms of special lexicology deals with the changes and the development of the vocabulary in the course of time. It is special historical lexicology that deals with the evolution of vocabulary units as time goes by.

The two approaches should not be contrasted, as they are interdependent since every linguistic structure and system actually exists in a state of constant development so that the synchronic state of a language system is a result of a long process of linguistic evolution.

As every word is a unity of semantic, phonetic and grammatical elements, the word is studied not only in lexicology, but in other branches of linguistics, too, lexicology being closely connected with general linguistics, the history of the language, phonetics, stylistics, and grammar.

According to S. Ullmann, lexicology forms next to phonology, the second basic division of linguistic science (the third is syntax). Consequently, the interaction between vocabulary and grammar is evident in morphology and syntax. Grammar reflects the specific lexical meaning and the capacity of words to be combined in human actual speech. The lexical meaning of the word, in its turn, is frequently signaled by the grammatical context in which it occurs. Thus, morphological indicators help to differentiate the variant meanings of the word (e.g., plural forms that serve to create special lexical meaning: colors, customs, etc.; two kinds of pluralization: brother → brethren — brothers; cloth → cloths — clothes). There are numerous instances when the syntactic position of the word changes both its

function and lexical meaning (e.g., an adjective and a noun element of the same group can change places: library school — school library).

The interrelation between lexicology and phonetics becomes obvious if we think of the fact that the word as the basis unit in lexicological study cannot exist without its sound form, which is the object of study in phonology. Words consist of phonemes that are devoid of meaning of their own, but forming morphemes they serve to distinguish between meanings. The meaning of the word is determined by several phonological features: a) qualitative and quantitative character of phonemes (e.g. dog-dock, pot-port); b) fixed sequence of phonemes (e.g. pot-top, nest-sent-tens); 3) the position of stress (e.g. insult (verb) and insult (noun)).

Summarizing, lexicology is the branch of linguistics concerned with the study of words as individual items and dealing with both formal and semantic aspects of words; and although it is concerned predominantly with an in-depth description of lexemes, it gives a close attention to a vocabulary in its totality, the social communicative essence of a language as a synergetic system being a study focus.

1.2. The word as the fundamental object of lexicology. The morphological structure of the English word. A word is a fundamental unit of a language. The real nature of a word and the term itself has always been one of the most ambiguous issues in almost every branch of linguistics. To use it as a term in the description of language, we must be sure what we mean by it. To illustrate the point here, let us count the words in the following sentence: You can’t tie a bow with the rope in the bow of a boat. Probably the most straightforward answer to this is to say that there are 14. However, the orthographic perspective taken by itself, of course, ignores the meaning of the words, and as soon as we invoke meanings we at least are talking about different words bow, to start with.

Being a central element of any language system, the word is a focus for the problems of phonology, lexicology, syntax, morphology, stylistics and also for a number of other language and speech sciences.

Within the framework of linguistics the word has acquired definitions from the syntactic, semantic, phonological points of view as well as a definition combining various approaches. Thus, it has been syntactically defined as “the minimum sentence” by H.Sweet and much later as “the minimum independent unit of utterance” by L.Bloomfield.

E. Sapir concentrates on the syntactic and semantic aspects calling the word

“one of the smallest completely satisfying bits of isolated meaning, into which the sentence resolves itself”.

A purely semantic treatment is observed in S. Ullmann’s explanation of words as meaningful segments that are ultimately composed of meaningful units.

The prominent French linguist A. Meillet combines the semantic, phonological and grammatical criteria: “A word is defined by the association of a given meaning with a given group of sounds susceptible of a given grammatical employment”.

Our native school of linguistics understands the word as a dialectical doublefacet unit of form and content, reflecting human notions, and in this sense being considered as a form of their existence. Notions fixed in word meanings are formed as generalized and approximately correct reflections of reality, thus, signifying them words objectivize reality and conceptual worlds in their content.

So, the word is a basic unit of a language resulting from the association of a given meaning with a given cluster of sounds susceptible of a certain grammatical employment.

Taking into consideration the above, let us consider the nature of the word. First, the word is a unit of speech which serves the purposes of human communication. Thus, the word can be defined as a unit of communication.

Secondly, the word can be perceived as the total of the sounds which comprise it.

Third, the word, viewed structurally, possesses several characteristics.

a)The modern approach to the word as a double-facet unit is based on distinguishing between the external and the internal structures of the word. By the external structure of the word we mean its morphological structure. For example, in the word post-impressionists the following morphemes can be distinguished: the prefixes post-, im-, the root –press-, the noun-forming suffixes -ion, -ist, and the grammatical suffix of plurality -s. All these morphemes constitute the external structure of the word post-impressionists.

The internal structure of the word, or its meaning, is nowadays commonly referred to as the word’s semantic structure. This is the word’s main aspect. Words can serve the purposes of human communication solely due to their meanings.

b)Another structural aspect of the word is its unity. The word possesses both its external (or formal) unity and semantic unity. The formal unity of the word is sometimes inaccurately interpreted as indivisibility. The example of postimpressionists has already shown that the word is not, strictly speaking, indivisible, though permanently linked. The formal unity of the word can best be illustrated by comparing a word and a word-group comprising identical constituents. The difference between a blackbird and a black bird is best explained by their relationship with the grammatical system of the language. The word blackbird, which is characterized by unity, possesses a single grammatical framing: blackbirds. The first constituent black is not subject to any grammatical changes. In the word-group a black bird each constituent can acquire grammatical forms of its own: the blackest birds I’ve ever seen. Other words can be inserted between the components which is impossible so far as the word is concerned as it would violate its unity: a black night bird.

The same example may be used to illustrate what we mean by semantic unity. In the word-group a black bird each of the meaningful words conveys a separate concept: bird – a kind of living creature; black – a color. The word blackbird conveys only one concept: the type of bird. This is one of the main features of any

word: it always conveys one concept, no matter how many component morphemes it may have in its external structure.

c) A further structural feature of the word is its susceptibility to grammatical employment. In speech most words can be used in different grammatical forms in which their interrelations are realized.

So, the formal/structural properties of the word are 1) isolatability (words can function in isolation, can make a sentence of their own under certain circumstances); 2) inseparability/unity (words are characterized by some integrity, e.g. a light – alight (with admiration); 3) a certain freedom of distribution (exposition in the sentence can be different); 4) susceptibility to grammatical employment; 5) a word as one of the fundamental units of the language is a double facet unit of form (its external structure) and meaning (its internal/semantic structure).

To sum it up, a word is the smallest naming unit of a language with a more or less free distribution used for the purposes of human communication, materially representing a group of sounds, possessing a meaning, susceptible to grammatical employment and characterized by formal and semantic unity.

There are 4 basic kinds of words: 1)orthographic words – words distinguished from each other by their spelling; 2) phonological words – distinguished from each other by their pronunciation; 3) word-forms which are grammatical variants; 4) words as items of meaning, the headwords of dictionary entries, called lexemes. A lexeme is a group of words united by the common lexical meaning, but having different grammatical forms. The base forms of such words, represented either by one orthographic word or a sequence of words called multi-word lexemes which have to be considered as single lexemes (e.g. phrasal verbs, some compounds) may be termed citation forms of lexemes (sing, talk, head etc), from which other word forms are considered to be derived.

Any language is a system of systems consisting of two subsystems: 1) the system of words’ possible lexical meanings; 2) the system of words’ grammatical forms. The former is called the semantic structure of the word; the latter is its paradigm latent to every part of speech (e.g. a noun has a 4 member paradigm, an adjective – a 3 member one, etc)

As for the main lexicological problems, two of these have already been highlighted. The problem of word-building is associated with prevailing morphological word-structures and with the processes of coining new words. Semantics is the study of meaning. Modern approaches to this problem are characterized by two different levels of study: syntagmatic and paradigmatic.

On the syntagmatic level, the semantic structure of the word is analyzed in its linear relationships with neighboring words in connected speech. In other words, the semantic characteristics of the word are observed, described and studied on the basis of its typical contexts.

On the paradigmatic level, the word is studied in its relationships with other words in the vocabulary system. So, a word may be studied in comparison with other words of a similar meaning (e. g. work, n. – labor, n.; to refuse, v. – to reject v. – to decline, v.), of opposite meaning (e. g. busy, adj. – idle, adj.; to accept, v. –

to reject, v.), of different stylistic characteristics (e. g. man, n. – chap, n. – bloke, n.

— guy, n.). Consequently, the key problems of paradigmatic studies are synonymy, antonymy, and functional styles.

One further important objective of lexicological studies is the study of the vocabulary of a language as a system. Revising the issue, the vocabulary can be studied synchronically (at a given stage of its development), or diachronically (in the context of the processes through which it grew, developed and acquired its modern form). The opposition of the two approaches is nevertheless disputable as the vocabulary, as well as the word which is its fundamental unit, is not only what it is at this particular stage of the language development, but what it was centuries ago and has been throughout its history.

1.3. Inner structure of the word composition. Word building. The morpheme and its types. Morphemic analysis of words. Affixation. The word consists of morphemes. The term morpheme is derived from Greek morphe (form) + -eme. The Greek suffix -eme has been adopted by linguists to denote the smallest significant or distinctive unit. The morpheme may be defined as the smallest meaningful unit which has a sound form and meaning, occurring in speech only as a part of a word. In other words, a morpheme is an association of a given meaning with a given sound pattern. But unlike a word it is not autonomous. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words, not independently, although a word may consist of a single morpheme. Nor are they divisible into smaller meaningful units. That is why the morpheme may also be defined as the minimum double-facet (shape/meaning) meaningful language unit that can be subdivided into phonemes (the smallest single-facet distinctive units of language with no meaning of their own). So there are 3 lower levels of a language – a phoneme, a morpheme, a word.

Word building (word-formation) is the creation of new words from elements already existing in a particular language. Every language has its own patterns of word formation. Together with borrowing, word-building provides for enlarging and enriching the vocabulary of the language.

A form is considered to be free if it may stand alone without changing its meaning; if not, it is a bound form, so called because it is always bound to something else. For example, comparing the words sportive and elegant and their parts, we see that sport, sortive, elegant may occur alone as utterances, whereas eleg-, -ive, -ant are bound forms because they never occur alone. A word is, by L. Bloomfield’s definition, a minimum free form. A morpheme is said to be either bound or free. This statement should be taken with caution because some morphemes are capable of forming words without adding other morphemes, being homonymous to free forms.

Words are segmented into morphemes with the help of the method of morphemic analysis whose aim is to split the word into its constituent morphemes and to determine their number and types. This is most effectively accomplished by the procedure known as the analysis into immediate constituents (IC’s), first suggested by L. Bloomfield. The procedure consists of

several stages: 1) segmentation of words; 2) identification of morphs; 3) classification of morphemes.

The procedure generally used to segment words into the constituting morphemes is the method of Immediate and Ultimate Constituents. It is based on a binary principle, i.e. each stage of the procedure involves two components the word immediately breaks into. At each stage these two components are referred to as the Immediate Constituents (ICs) Each IC at the next stage of the analysis is in turn broken into two smaller meaningful elements. This analysis is completed when we arrive at constituents incapable of any further division, i.e. morphemes. In terms of the method employed these are referred to as the Ultimate Constituents (UCs).

The analysis of the morphemic structure of words reveals the ultimate meaningful constituents (UCs), their typical sequence and arrangement, but it does not show the way a word is constructed. The nature, type and arrangement of the ICs of the word are known as its derivative structure. Though the derivative structure of the word is closely connected with its morphemic structure and often coincides with it, it cardinally differs from it. The derivational level of the analysis aims at establishing correlations between different types of words, the structural and semantic patterns being focused on, enabling one to understand how new words appear in a language.

Coming back to the issue of word segmentability as the first stage of the analysis into immediate constituents, all English words fall into two large classes: 1) segmentable words, i.e. those allowing of segmentation into morphemes, e.g. information, unputdownable, silently and 2) non-segmentable words, i.e. those not allowing of such segmentation, e.g. boy, wife, call, etc.

There are three types of segmentation of words: complete, conditional and defective. Complete segmentability is characteristic of words whose the morphemic structure is transparent enough as their individual morphemes clearly stand out within the word lending themselves easily to isolation. Its constituent morphemes recur with the same meaning in many other words, e.g. establishment, agreement.

Conditional morphemic segmentability characterizes words whose segmentation into constituent morphemes is doubtful for semantic reasons. For instance, in words like retain, detain, or receive, deceive the sound-clusters [ri], [di], on the one hand, can be singled out quite easily due to their recurrence in a number of words, on the other hand, they sure have nothing in common with the phonetically identical morphemes re-. de- as found in words like rewrite, reorganize, decode, deurbanize; neither the sound-clusters [ri], [di] nor the soundclusters [-tein], [si:v] have any lexical or functional meaning of their own. Therefore, the morphemes making up words of conditional segmentability differ from morphemes making up words of complete segmentability in that the former do not reach the full status of morphemes for the semantic reason and that is why a special term is applied to them – pseudo-morphemes or quasi-morphemes.

Defective morphemic segmentability is the property of words whose unique morphemic components seldom or never recur in other words (e.g. in the words

cranberry, gooseberry, strawberry defective morphemic segmentability is obvious due to the fact that the morphemes cran-, goose-, straw- are unique morphemes).

Thus, on the level of morphemic analysis there are basically two types of elementary units: full morphemes and pseudo- (quasi-)morphemes, the former being genuine structural elements of the language system in the prime focus of linguistic attention. At the same time, a significant number of words of conditional and defective segmentability reveal a complex nature of the morphological system of the English language, representing various heterogeneous layers in its vocabulary.

The second stage of morphemic analysis is identification of morphs. The main criteria here are semantic and phonetic similarity. Morphs should have the same denotational meaning, but their phonemic shape can vary (e.g. please, pleasing, pleasure, pleasant or duke, ducal, duchess, duchy). Such phonetically conditioned positional morpheme variants are called allomorphs. They occur in a specific environment, being identical in meaning or function and characterized by complementary distribution.(e.g. the prefix in- (intransitive) can be represented by allomorphs il- (illiterate), im- (impossible), ir- (irregular)). Complementary distribution is said to take place when two linguistics variants cannot appear in the same environment (Not the same as contrastive distribution by which different morphemes are characterized, i.e. if they occur in the same environment, they signal different meanings (e.g. the suffixes -able (capable of being): measurable and -ed (a suffix of a resultant force): measured).

The final stage of the procedure of the morphemic analysis is classification of morphemes. Morphemes can be classified from 6 points of view (POV).

1. Semantic POV: roots and affixes/non-roots. A root is the lexical nucleus of a word bearing the major individual meaning common to a set of semantically related words, constituting one word cluster/word-family (e.g. learn-learner- learned-learnable; heart-hearten, dishearten, hear-broken, hearty, kind-hearted etc.) with which no grammatical properties of the word are connected. In this respect, the peculiarity of English as a unique language is explained by its analytical language structure – morphemes are often homonymous with independent units (words). A morpheme that is homonymous with a word is called a root morpheme.

Here we have to mention the difference between a root and a stem. A root is the ultimate constituent which remains after the removal of all functional and derivational affixes and does not admit any further analysis. Unlike a root, a stem is that part of the word that remains unchanged throughout its paradigm (formal aspect). For instance, heart-hearts-to one’s heart’s content vs. hearty-heartier-the heartiest. It is the basic unit at the derivational level, taking the inflections which shape the word grammatically as a part of speech.

There are three types of stems: simple, derived and compound.

Simple stems are semantically non-motivated and do not constitute a pattern on analogy with which new stems may be modeled (e.g. pocket, motion, receive, etc.).

Simple stems are generally monomorphic and phonetically identical with the root morphemes (sell, grow, kink, etc.).

Derived stems are built on stems of various structures, they are motivated, i.e. derived stems are understood on the basis of the derivative relations between their immediate constituents and the correlated stems. Derived stems are mostly polymorphic (e.g. governments, unbelievable, etc.).

Compound stems are made up of two immediate constituents, both of which are themselves stems, e.g. match-box, pen-holder, ex-film-star, etc. It is built by joining two stems, one of which is simple, the other is derived.

The derivational types of words are classified according to the structure of their stems into simple, derived and compound words.

Derived words are those composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational morphemes.

Compound words have at least two root-morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant.

So, there are 4 structural types of words in English: 1) simple words (singleroot morphemes, e.g. agree, child, red, etc.); 2) derivatives (affixational derived words) consisting one or more affixes: enjoyable, childhood, unbelievable). Derived words are extremely numerous in the English vocabulary. Successfully competing with this structural type is the so-called root word which has only a root morpheme in its structure. This type is widely represented by a great number of words belonging to the original English stock or to earlier borrowings (house, room, book, work, port, street, table, etc.). In Modern English, it has been greatly enlarged by the type of word-building called conversion (e. g. to hand, v. formed from the noun hand; to can, v. from can, n.; to pale, v. from pale, adj.; a find, n. from to find, v.; etc.); 3) compound words consisting of two or more stems (e. g. dining-room, bluebell, mother-in-law, good-for-nothing, etc.). Words of this structural type are produced by the word-building process called composition; 4) derivational compounds in which phrase components are joined together by means of compounding and affixation (e.g. oval-shaped, strong-willed, care-free); 5) phrasal verbs as a result of a strong tendency of English to simplification (to put up with, to give up, to take for, etc.)

The morpheme, and therefore the affix, which is a type of morpheme, is generally defined as the smallest indivisible component of the word possessing a meaning of its own. Meanings of affixes are specific and considerably differ from those of root morphemes. Affixes have widely generalized meanings and refer the concept conveyed by the whole word to a certain category, which is all-embracing. So, the noun-forming suffix -er could be roughly defined as designating persons from the object of their occupation or labor (painter – the one who paints) or from their place of origin (southerner – the one living in the South). The adjectiveforming suffix -ful has the meaning of «full of», «characterized by» (beautiful, careful) whereas -ish may often imply insufficiency of quality (greenish – green, but not quite).

There are numerous derived words whose meanings can really be easily deduced from the meanings of their constituent parts. Yet, such cases represent only the first stage of semantic readjustment within derivatives. The constituent morphemes within derivatives do not always preserve their current meanings and are open to subtle and complicated semantic shifts (e.g. bookish: (1) given or devoted to reading or study; (2) more acquainted with books than with real life, i. e. possessing the quality of bookish learning).

The semantic distinctions of words produced from the same root by means of different affixes are also of considerable interest, both for language studies and research work. Compare: womanly (used in a complimentary manner about girls and women) – womanish (used to indicate an effeminate man and certainly implies criticism); starry (resembling stars) – starred (covered or decorated with stars).

There are a few roots in English which have developed a great combining ability in the position of the second element of a word and a very general meaning similar to that of an affix. These are semi-affixes because semantically, functionally, structurally and stylistically they behave more like affixes than like roots, determining the lexical and grammatical class the word belongs to (e.g. -man: cameraman, seaman; -land: Scotland, motherland; -like: ladylike, flowerlike; — worthy: trustworthy, praiseworthy; -proof: waterproof, bullet-proof, etc.)

2.Position POV: according to their position affixational morphemes fall into suffixes – derivational morphemes following the root and forming a new derivative in a different part of speech or a different word class (writer, rainy, magnify, etc.), infexes – affixes placed within the word (e.g. adapt-a-tion, assimil-a-tion, sta-n-d etc.), and prefixes – derivational morphemes that precede the root and modify the meaning (e.g. decipher, illegal, unhappy, etc.) The process of affixation itself consists in coining a new word by adding an affix or several affixes to a root morpheme. Suffixation is more productive than prefixation in Modern English.

3.Functional POV: from this perspective affixational morphemes include derivational morphemes as affixal morphemes that serve to make a new part of speech or create another word in the same one, modifying the lexical meaning of the root (e.g. to teach-teacher; possible-impossible), and functional morphemes, i.e. grammatical ones/inflections that serve to build grammatical forms, the paradigm of the word (e.g. has broken; oxen; clues), carrying only grammatical meaning and thus relevant only for the formation of words. Some functional morphemes have a dual character. They are called functional word-morphemes (FWM) – auxiliaries (e.g. is, are, have, will, etc). The main function of FWM is to build analytical structures.

As for word combinations, being two components expressing one idea (e.g. to give up – to refuse; to take in – to deceive) they are full fleshed words. Their function is to derive new words with new meanings. They behave like derivational morphemes with a functional form. They are called derivational word

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- Views from Understanding Evolution

- Open Access

- Published: 20 June 2008

Evolution: Education and Outreach

volume 1, pages 281–286 (2008)Cite this article

-

12k Accesses

-

3 Citations

-

18 Altmetric

-

Metrics details

Anyone who has ever tackled a Shakespeare play knows that English has changed substantially in the 400 years since Elizabeth I ruled England. In fact, Elizabethan English can seem like a completely different language from the one we speak today. Just try describing your mood with the Shakespearean terms allicholly and tetchy—you are more likely to get confused looks than sympathy for being unhappy and irritable. Four hundred years from now, English speakers will likely feel the same way about the language we speak today. Unless you are keeping up with the latest additions to the Oxford English Dictionary, you might already be behind the times: Do you know if you would be eligible to participate in a girlcott? Or whether you would want a job as a helmer? Or when it would be appropriate to wear a jandal?

It is clear that languages change. In an article in this issue, Venditti and Pagel (2008) take that notion one step further. They explain that languages do not simply change over time, but instead evolve in a process that parallels biological evolution. Venditti and Pagel take methods designed for analyzing the rates of evolution of new species and use them to learn more about the rates at which new languages form. Here, we will dig into the idea of linguistic evolution and see exactly how it is similar to and different from biological evolution.

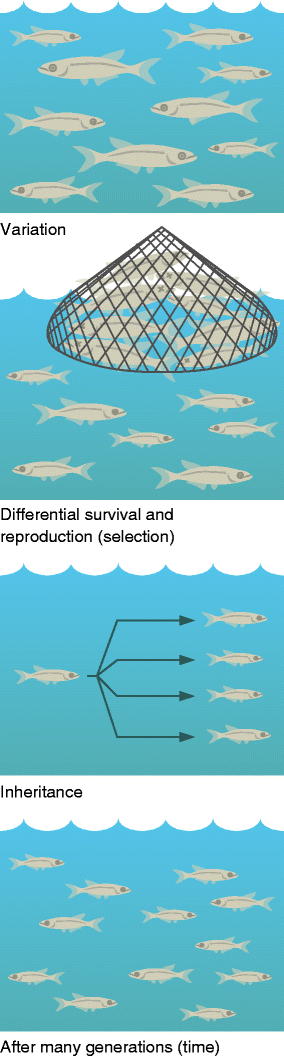

The essence of biological evolution at the level of the individual organism is variation, inheritance, differential survival and reproduction, and time. Individuals within a population vary in the traits they have. Many of those traits are genetically encoded—and so are heritable. If individuals with particular traits happen to leave behind more offspring, those traits will be over-represented in the next generation. Over many generations, this process can lead to major evolutionary change. So, for example, if fish within a population vary in body size, if body size is influenced by heritable genes, and if larger fish are less likely to reproduce (perhaps because they tend to get caught in fishing nets), the fish population will evolve smaller body sizes over time (Fig. 1). The same basic process is at work whether we are talking about the evolution of fish body size, the evolution of bacterial antibiotic resistance, or the evolution of human lactose tolerance.

An example of natural selection operating on a fish population. The preferential netting of large fish causes the fish population to evolve smaller body sizes. Illustration adapted with permission from the Understanding Evolution website

Full size image

These ingredients—which you can remember with the handy mnemonic VIST (variation, inheritance, selection, and time; Understanding Evolution. Focus on the Fundamentals 2006)—inevitably lead to evolution via natural selection. The same concepts apply to languages, but in a slightly modified form:

-

Variation: In biological evolution, variation usually takes the form of physiological, anatomical, or behavioral traits and comes about as the result of random mutation. For example, a mutation could cause an individual fish to have a slightly smaller body size than other individuals in the population. In linguistic evolution, variation takes the form of new words, pronunciations, and grammatical structures and may come about as the result of human invention. For example, people arriving on an uninhabited island may find that they need a word for an unfamiliar plant species and simply make one up.

-

Inheritance: Biological traits are encoded in DNA. They are usually passed on from parent to offspring—though some organisms (e.g., bacteria) can also directly pass bits of DNA, and the traits they encode, back and forth to one another. Linguistic variation, on the other hand, is “inherited” through learning. Children are likely to learn linguistic traits from their parents and others around them. Just as red-furred squirrels are likely to have red-furred offspring, parents who speak with a southern drawl are likely to have children who speak with a southern drawl. Linguistic “inheritance,” though, is much fuzzier and more flexible than biological inheritance. Like bacteria slipping stretches of DNA to one another, human learning allows people to share new words, pronunciations, and grammatical structures with each other directly—even if the two people are not closely related and originally spoke different languages.

-

Selection: As selection acts on organisms, individuals with particular traits are more likely to successfully reproduce than others. Those advantageous traits might be anything from having coloration that blends into the environment better to producing a particularly far-reaching mating call. Correspondingly, individuals with certain disadvantageous traits (e.g., not being able to use a key amino acid) do not leave behind as many offspring. In linguistic evolution, selection takes a slightly different form. Some words or structures may be more memorable or useful and, hence, may be more likely to “reproduce”—i.e., be passed on to others. For example, today the words blog and bandwidth are more likely to be shared than a word like calash (the folding hood of a horse-drawn buggy).

-

Time. Over time, both biological and linguistic evolution can produce major changes—whether that means the radiation of new clades of terrestrial vertebrates after the dinosaur extinction or the development of new dialects as people discovered and settled on the Pacific Islands.

Because languages experience variation, inheritance, and selection over long periods of time, they can evolve in a process that parallels biological natural selection. However, the differences described above change the process in a few key ways:

-

In biological evolution, new variation is introduced via a process of random mutation—that is, mutations occur without regard to what would be useful to the organism. So, for example, a population of plants living in an area affected by climate change cannot produce new drought-tolerant mutants just because they would be helpful. In linguistic evolution, on the other hand, a person can invent a new word that would be particularly handy in the current situation, introduce it to the language, and begin to pass that word on to other people. This is not to suggest that all linguistic innovation is deliberate. New words and linguistic structures can arise in many ways. Nonetheless, the possibility of such intentionality can shift the direction of linguistic evolution in a manner not possible in biological evolution.

-

Horizontal transfer—the process of passing genes (or in this case, linguistic elements) to individuals other than offspring—may be more common in linguistic evolution than it is in biological evolution. For most organisms with which we are familiar, the units of inheritance (genes) are passed mainly from parent to offspring. But in languages, the units of inheritance (e.g., words) can be easily shared with almost anyone. For example, English now includes many words picked up from other languages—like the word shampoo which was probably passed to English from Hindi in the 1700s or earlier (The Oxford English Dictionary 1989). Given the ease with which words can be shared across languages, horizontal transfer at this level is surprisingly infrequent; languages maintain their integrity despite the possibility of a foreign onslaught (Pagel and Mace 2004). Nevertheless, by regularly introducing new variation to languages, the process of horizontal transfer allows linguistic evolutionary change to occur more quickly.

-

In biological evolution, advantageous traits provide a reproductive boost to individual organisms. So fish with small body sizes leave behind more offspring in heavily netted areas, and the small body size trait spreads for this reason. In linguistic evolution, however, words may, but need not, provide any particular survival or reproductive advantage to their users in order to proliferate. Words like blog and bandwidth may be spreading like wildfire but probably are not doing much for the reproductive capabilities of those of us who use them. This disconnect between linguistic variation and reproductive advantage helps decouple linguistic and biological evolution.

Despite these differences, biological evolution and language evolution are similar enough that many of the same concepts and tools can be applied to both situations. We have seen that languages can evolve via natural selection; they can also evolve via drift as biological systems do. Evolution via genetic drift works much like evolution via natural selection, but with one key difference: differential survival and reproduction (the selection step described above) are caused, not by advantageous or disadvantageous traits, but by random chance. Some individuals happen to leave more offspring in the next generation than do others—but not because of a special ability to resist predation, get nourishment, or attract mates—because they simply got lucky. Though drift operates via random chance, it can still end up causing major evolutionary change. Some traits can drift out of a population entirely, others can spread and become “fixed” (possessed by all members of the population).

The same process operates on languages. Imagine a group of people shipwrecked on an island. Some of them tend to use the word zero and others tend to use the word naught to refer to the same thing. After many, many generations on the island, zero falls into disuse and out of the language entirely—not because it is hard to remember or ineffective—but because people just happened to use naught more frequently. In this case, the word zero goes extinct in the island dialect through the process of linguistic drift.

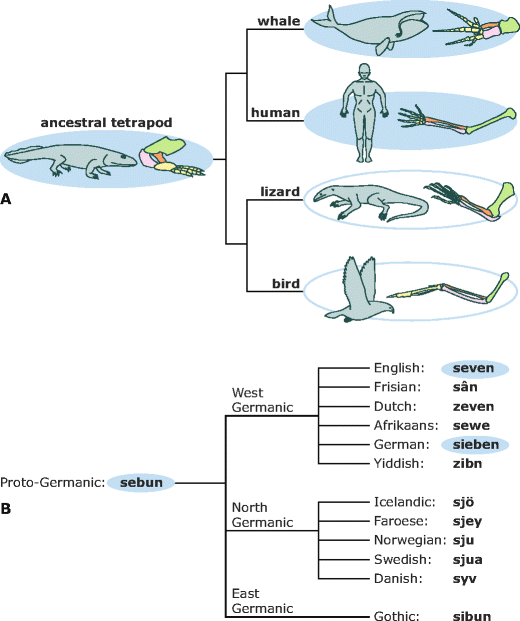

Even technical, genetic concepts can be fruitfully applied to linguistic evolution. For example, biologists have found that some sorts of genes do not evolve much—even through many speciation events and over many millions of years. Housekeeping genes are involved in the basic jobs that keep cells functioning and alive. Because they are so important and are turned on all the time, such genes evolve very slowly and are similar even among distantly related species. Linguistics has its own equivalents to housekeeping genes. “Workhorse” words that get used all the time—like numerals and the pronouns I, you, he, and she—evolve very slowly (Pagel et al. 2007). Just consider the words seven (in English) and sieben (in German). They are remarkably similar even though much of the rest of our vocabularies have diverged—as will be readily apparent to any English speaker who tries to navigate via the traffic signs in Berlin.

The words seven and sieben are an example of what linguists would call cognates and what evolutionary biologists would call homologies. These are words whose similarities can be chalked up to common ancestry. The bones in your arm and the bones in a whale’s fin are homologous (Fig. 2). They share the same basic layout because humans and whales share a common ancestor who passed that bone arrangement on to each of us. In the same way, the words seven and sieben are similar because they both descended from one word in a common ancestral language, West Germanic, which had begun to evolve by about 300 BC (Robinson 1994). West Germanic, in turn, evolved from an even older language—Proto-Germanic. Linguists have reconstructed the Proto-Germanic ancestor of seven and sieben to be something like sebun (Ringe 2006)—much as evolutionary biologists have pieced together different lines of evidence to figure out what the ancestor of humans and whales must have looked like.

Phylogenies illustrating the concept of homology. a The bones in a whale’s fin and a human’s hand are homologous. Both sets of bones are descended from the same structure in a common ancestor. Illustration adapted with permission from the Understanding Evolution website. b The words seven in English and sieben in German are homologous. They are both descended from the same word in their common ancestral language. Language phylogeny adapted from Campbell (2004)

Full size image

In biological evolution, homologous structures can be used to reconstruct phylogenies—the branching trees that depict the evolutionary relationships among organisms. As you might guess, cognates (linguistic homologies) are used to reconstruct the relationships among languages. The study of punctuated language evolution described by Venditti and Pagel in this issue is based on this principle (Atkinson et al. 2008). The researchers collected hundreds of words from different language families—for example, the word for two from 95 different Bantu languages—determined which were homologous to one another, and used this information to construct a family tree of the language group.

Venditti and Pagel used concepts and tools borrowed directly from evolutionary biology to illuminate our linguistic history—revealing that the early development of a new dialect can be a turbulent time, with many words changing all at once. Though they focused on language change, the same evolutionary concepts and tools can be applied to any system that involves variation, some form of inheritance, differential survival and reproduction, and time for the cycle to repeat itself over and over. This means that much cultural information—cuisines, folk art styles, religious traditions—can also be examined in an evolutionary light.

Consider the Lemba, a tribe from southern Africa. Unlike their neighboring tribes, the Lemba’s traditions include male circumcision and dietary restrictions like those of the Jewish faith—a group whose ethnic roots are planted several thousand miles away. Taking an evolutionary perspective might lead us to wonder if the similarities between Lemba and Jewish traditions are homologous or analogous—that is, did the traditions descend, with slight modification, from the same practice in some historical group of people, or did they arise separately? Several lines of evidence suggest that these traditions are homologous: Other oral traditions of the Lemba (like the idea that they migrated to South Africa from the Middle East) are consistent with Jewish ancestry—and, perhaps most convincingly, geneticists have found that many Lemba men carry genetic sequences on their Y chromosomes that are typical of Jewish populations (Spurdle and Jenkins 1996). Some Lemba do seem to have ethnic roots in Jewish populations and probably brought their slowly evolving cultural traditions with them when they left the Middle East.

The Jewish ancestry of Lemba cultural traditions illustrates one final point about biological, cultural, and linguistic evolution. Since they are inherited in different ways, the paths traced by these different forms of evolution—even within the same group of people—need not be identical. Evolutionary analyses of Lemba genes and cultural traditions identify ancestral roots in Jewish populations. The Lemba languages, on the other hand, are more closely related to Bantu languages, like Xhosa (which uses tongue clicks), than they are to Hebrew. Linguistically, the Lemba are solidly South African, even while the paths of their cultural and genetic histories lead to different continents. However informative any one of these evolutionary histories may be, it can only provide a glimpse of the immense diversity inherent in any human population.

Give Me an Example of That

Want more examples of homologies? Check this out:

-

Striking similarities. We have seen that homologies can crop up in surprising places. The words you use to count to ten are homologous to numerals in other languages, just as your finger bones are homologous to bones in the wings, paws, and fins of many other species. But that is not all. The concept of homology can be applied to the genes in your DNA and even aspects of behavior. This short article from the Understanding Evolution website takes a look at five examples of homology, including structural, genetic, and behavioral examples: http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/homology_01.

Branch Out

Visit the Understanding Evolution website to explore ideas related to key concepts from this article.

-

The concept of VIST—variation, inheritance, selection, and time—can help us understand long-term change in many different situations: from the shift in body size in a population of heavily netted fish to the divergence of languages. Even within biology proper, this concept operates at many different levels. The cell lineages within an individual organism evolve through this process, as some lineages out-compete others and may inappropriately take over—much to the detriment of the individual made up of those cells. In the same way, large clades of species may evolve, with some groups becoming particularly diverse simply because they have traits that make them prone to speciation. Learn more online: http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/selectionhierarchy_01.

-

We have seen that biological and cultural evolution operate through many of the same processes but that they need not parallel one another exactly. In many cases, these two sorts of evolution even prod one another in new directions. The biological evolution of humans’ ability to digest milk as adults (lactose tolerance), the biological evolution of wild aurochs into domesticated cattle, and the cultural evolution of dairying skills are historically intertwined—as well as fascinating and relevant to your students’ everyday lives. Learn more online: http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/news/070401_lactose.

Dig Deeper

Visit Understanding Evolution online to find out even more about some of the concepts addressed here.

-

How natural selection works: http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/evo_25

-

How genetic drift works: http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/samplingerror_01

In the Classroom

The broad applicability of the VIST concept can help your students recognize both the logic that underlies evolutionary theory and the power of the theory for helping us understand many different sorts of phenomena. High school students can analyze different evolutionary situations and identify the components of VIST within them. For example, you could challenge your students to read the following articles and they identify and explain the variation, inheritance, selection, and time that underlie the central evolutionary phenomena in each:

-

From the origin of life to the future of biotech. The artificial selection of useful RNA molecules: http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/ellington_01

-

Evolution within. The evolution of cancer cells within an individual patient: http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/news/071001_cancer

-

Angling for evolutionary answers. The evolution of smaller body sizes in fish as the result of human fishing practices: http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/conover_01

Students at lower levels, who might not yet be ready to integrate variation, inheritance, selection, and time, can develop understandings of individual VIST components. Learn more about this teaching approach:

-

Focus on the fundamentals. http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evosite/Lessons/IFundamentals.php#

References

-

Atkinson SD, Meade A, Venditti C, Greenhill SJ, Pagel M. Languages evolve in punctuational bursts. Science 2008;319:588.

Article

CASGoogle Scholar

-

Campbell L. Historical linguistics. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press; 2004.

-

Pagel M, Mace R. The cultural wealth of nations. Nature 2004;428:275–8.

Article

CASGoogle Scholar

-

Pagel M, Atkinson QD, Meade A. Frequency of word-use predicts rates of lexical evolution throughout Indo-European history. Nature 2007;449:717–20.

Article

CASGoogle Scholar

-

Ringe DA. From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Book

Google Scholar

-

Robinson OW. Old English and its closest relatives. London: Routledge; 1994.

Google Scholar

-

Spurdle AB, Jenkins T. The origins of the Lemba “Black Jews” of southern Africa: evidence from p12F2 and other Y-chromosome markers. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:1126–33.

PubMed Central

CASGoogle Scholar

-

The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. Oxford University Press. Available at: http://dictionary.oed.com/cgi/entry/50221828 (accessed April 11, 2008).

-

Understanding Evolution. Focus on the fundamentals 2006. Available at: http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evosite/Lessons/IFundamentals.php (accessed April 11, 2008).

-

Venditti C, Pagel M. Speciation and bursts of evolution. Evolution: education and outreach 2008; doi:10.1007/s12052-008-0049-4.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge Mark Pagel and Judy Scotchmoor for helpful comments on earlier drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

-

University of California Museum of Paleontology, 1101 Valley Life Sciences Building, Berkeley, CA, 94720-4780, USA

Anastasia Thanukos

Authors

- Anastasia Thanukos

You can also search for this author in

PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to

Anastasia Thanukos.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0

), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thanukos, A. A Look at Linguistic Evolution.

Evo Edu Outreach 1, 281–286 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-008-0058-3

Download citation

-

Received: 25 April 2008

-

Accepted: 28 April 2008

-

Published: 20 June 2008

-

Issue Date: July 2008

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-008-0058-3

Keywords

- Linguistic evolution

- Natural selection

- Genetic drift

- Homology

- Phylogenies

- Teaching

By John McWhorter, Ph.D., Columbia University

Language is a tool we use on a daily basis to communicate with each other. But as significant as language is to us, it hasn’t always been this way. Language has been evolving over the years, and with it, the meanings of words that come so naturally to us today.

(Image: aga7ta/Shutterstock)

Semantics, or the meaning of words, have been changing ever since the first language began to be spoken, and have evolved into what they mean now, when there are more than 6,000 existing languages on record. Not surprisingly, there have been a number of processes that have contributed to these changes, although admittedly, some have had much more profound impacts than others.

Semantic Drift

Semantic drift is the simple phenomenon by which the correspondence between a word and the real-world entity or process that it is connected to, tends to undergo a shift over time. This drift can take place in a number of directions, often seeming completely random, although there is almost always a logical connection from point to point.

For instance, the word silly very plainly means foolish to us today. What is surprising is the fact that in Old English, it meant that one was blessed. In fact, the word derives its roots from the same place as the German word, selig, which means blessed. So, selig and silly were cognates, both meaning blessed.

Mementos of English in which silly meant blessed can be found dating as late as 1400. From here, the words started to drift in meaning. One who was blessed was likely to be innocent, which is why by the Middle Ages, silly began to mean innocent.

Here, one starts to see the drift taking place in different directions. One who was innocent tended to elicit compassion, which slowly began to blur the fine line between eliciting compassion and seeming weak. With time, the fine line between being weak and being foolish further began to get blurred. As a result, step by step, a word that used to mean blessed came by to mean foolish, and at no point did anyone notice a major shift in language, which actually happened over generations.

Similarly, the word nice went through a semantic drift. In older sources, nice used to mean fine. Then, as time passed by, nice, which should have meant subdivided finely, began to get perceived differently, which made the word mean what it does today.

When we hear nicety, our mind immediately moves to think of the object of description as nice. What that really meant was something fine. Nicety meant a finer distinction, something more specific. As the meaning of the words have evolved, the usage of some words has changed, which is why nicety is used the way it is today.

This is how languages evolve: when these phenomena occur to all or most of the words in a language, the language itself goes through a shift. One can notice a lot of differences in the first language that was used and the 6,000 or so new languages that exist now. The differences have appeared in the new languages as well.

Learn More about how language changes.

Semantic Narrowing

Another phenomenon that can be commonly seen in languages and the changing meaning of words is semantic narrowing. This happens when words begin to develop more specific, more particular meanings than the ones that they started out with.

An evident example of a word that went through such a process is meat. In Old English, meat referred to any and all items of food. It could also mean something sweet, any sweet that existed at the time. As time passed, meat gradually began to refer only to animal flesh.

Some old form of language generally tends to linger on the fringes of usage, which can be seen in this example, the word sweetmeat is now used to refer to fruits and candies. Although one may wonder about the usage of meat in the context if the etymology is not known, we do not spend too long thinking about it, as this is how the language has evolved to be used.

(Image: Vorobyeva/Shutterstock)

Semantic Broadening

On the other hand, as a sort of converse process to semantic narrowing, is the process of semantic broadening, which is the process through which the usage of words begins to become more general than it used to be. A commonly cited example of this phenomenon is the Old English word bird, which was earlier and originally brid, which actually only referred to young birds, similar in usage to the way birdie is today. The word which was used to refer to birds in general, on the other hand, was fugol. German speakers will identify this word and its resemblance to the German Vogel. Again, this example stands as testimony to the fact that German and English were much more closely related in the past than they are now.

Gradually, brid, the Old English word for bird semantically broadened in meaning to refer to all birds, as it is today, and fugol transformed over time to fowl, which today, is used in reference to game birds, or is at times a lesser used, stylistic usage in reference to birds.

This is a transcript from the video series The Story of Human Language. Watch it now, on The Great Courses Plus.

Tracing Back to the Roots

When we look at the vocabulary that is used today, it is easy to see how a lot of it is the result of evolution over a number of years, a result of words passing over millions of mouths over many, many years.

Proto-Indo-European language, and the fact that it is the biggest language family to exist, is perhaps the reason why linguists are able to see so many different processes in language and find connections between languages.

Learn More about the Indo-European language family.

Commonly Asked Questions about Semantic Changes:

Q: Why do semantic changes occur?

Although there is no set reason for which the meanings of words change, semantic changes occur when the usage of words gradually changes as a language gets spoken generation after generation.

Q: What are the various kinds of semantic changes?

Any process by which the meanings of words undergo a shift over time is a semantic change, such as semantic drift, semantic broadening, or semantic narrowing.

Q: What is semantic broadening?

Semantic broadening is the process in which the meaning of a word evolves over time to represent a more general concept or thing than it did originally.

Keep Reading

Wily Words: How Languages Mix on the Level of Words

The Social Context that Shapes our Talk

Language Evolution: How One Language Became Five Languages

People in general have no difficulty coping the new words. We can very quickly understand a new word in our language (a neologism) and accept the use of different forms of that new word. This ability must derive in part from the fact that there is a lot of regularity in the word-formation process in our language.

In some aspects the study of the processes whereby new words come into being language like English seems relatively straightforward. This apparent simplicity however masks a number of controversial issues. Despite the disagreement of scholars in the area, there don´t seem to be a regular process involved.

These processes have been at work in the language for some time and many words in daily use today were, at one time, considered barbaric misuses of the language.

What is Coinage?

Coinage is a common process of word-formation in English and it is the invention of totally new terms. The most typical sources are invented trade names for one company´s product which become general terms (without initial capital letters) for any version of that product.

For example: aspirin, nylon, zipper and the more recent examples kleenex, teflon.

This words tend to become everyday words in our language.

What is Borrowing?

Borrowing is one of the most common sources of getting new words in English. That is the taking over of words from other languages. Throughout history the English language has adopted a vast number of loan words from other languages. For example:

- Alcohol (Arabic)

- Boss (Dutch)

- Croissant (French)

- Piano (Italian)

- Pretzel (German)

- Robot (Czech)

- Zebra (Bantu)

Etc…

A special type of borrowing is the loan translation or calque. In this process, there is a direct translation of the elements of a word into the borrowing language. For example: Superman, Loan Translation of Übermensch, German.

What is Compounding?

The combining process of words is technically known as compounding, which is very common in English and German. Obvious English examples would be:

- Bookcase

- Fingerprint

- Sunburn

- Wallpaper

- Textbook

- Wastebasket

- Waterbed

What is Blending?

The combining separate forms to produce a single new term, is also present in the process of blending. Blending, takes only the beginning of one word and joining it to the end of the other word. For instance, if you wish to refer to the combined effects of smoke and fog, there´s the term smog. The recent phenomenon of fund rising on television that feels like a marathon, is typically called a telethon, and if you´re extremely crazy about video, you may be called a videot.

What is Clipping?

Clipping is the process in which the element of reduction which is noticeable in blending is even more apparent. This occurs when a word of more than one syllable is reduced to a shorter form, often in casual speech. For example, the term gasoline is still in use but the term gas, the clipped form is used more frequently. Examples

- Chem.

- Gym

- Math

- Prof

- Typo

What is Backformation?

Backformation is a very specialized type of reduction process. Typically a word of one type, usually noun, is reduced to form another word of a different type, usually verb. A good example of backformation is the process whereby the noun television first came into ude and then the term televise is created form it.

More examples:

- Donation – Donate

- Option – Opt

- Emotion – Emote

- Enthusiasm – Enthuse

- Babysit – Babysitter

What is Conversion?

Conversion is a change in the function of a word, as for example, when a noun comes to be used as a verb without any reduction. Other labels of this very common process are “category change” and “functional shift”. A number of nouns such as paper, butter, bottle, vacation and so on, can via the process of conversion come to be used as verbs as in the following examples:

- My brother is papering my bedroom.

- Did you buttered this toast?

- We bottled the home brew last night.

What is an Acronym?

Some new words known as acronyms are formed with the initial letters of a set of other words. Examples:

- Compact Disk – CD

- Video Cassette Recorder – VCR

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration – NASA

- The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization – UNESCO

- Personal Identification Number –PIN

- Women against rape – WAR

What is Derivation?

Derivation is the most common word formation process and it accomplished by means of a large number of small bits of the English language which are not usually given separate listings in dictionaries. These small bits are called affixes. Examples:

- Unhappy

- Misrepresent

- Prejudge

- Joyful

- Careless

- Happiness

Prefixes and Suffixes

In the preceding group of words, it should be obvious that some affixes have to be added to the beginning of a word. These are called prefixes: unreliable. The other affix forms are called suffixes and are added at the end of the word: foolishness.

Infixes

One of the characteristics of English words is that any modifications to them occur at the beginning or the end; mix can have something added at the beginning re-mix or at the end, mixes, mixer, but never in the middle, called infixes.

Activities – WORDS AND WORD FORMATION PROCESSES

Activity 1

Identify the word formation process involved in the following sentences:

- My little cousin wants to be a footballer

- Rebecca parties every weekend

- I will have a croissant for breakfast.

- Does somebody know where is my bra?

- My family is vacationing in New Zealand

- I will babysit my little sister this weekend

- Would you give me your blackberry PIN?

- She seems really unhappy about her parents’ decision.

- I always have kleenex in my car.

10. A carjacking was reported this evening.

(To check your answers, please go to home and check the link: Activities Keyword)

*You may require checking other sources