Not to be confused with Seoul.

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief of «an immaterial aspect or essence of a living being», generally applied to humans, called the soul.[1] In lay terms the soul is the spiritual essence of a person, which includes our identity, personality, and memories that is believed to be able to survive our physical death.

Etymology[edit]

The Modern English noun soul is derived from Old English sāwol, sāwel. The earliest attestations reported in the Oxford English Dictionary are from the 8th century. In King Alfred’s translation of De Consolatione Philosophiae, it is used to refer to the immaterial, spiritual, or thinking aspect of a person, as contrasted with the person’s physical body; in the Vespasian Psalter 77.50, it means «life» or «animate existence».

The Old English word is cognate with other historical Germanic terms for the same idea, including Old Frisian sēle, sēl (which could also mean «salvation», or «solemn oath»), Gothic saiwala, Old High German sēula, sēla, Old Saxon sēola, and Old Norse sāla. Present-day cognates include Dutch ziel and German Seele.[2]

Religious views[edit]

In Judaism and in some Christian denominations, only human beings have immortal souls (although immortality is disputed within Judaism and the concept of immortality was most likely influenced by Plato).[3] For example, Thomas Aquinas, borrowing directly from Aristotle’s On the Soul, attributed «soul» (anima) to all organisms but argued that only human souls are immortal.[4] Other religions (most notably Hinduism and Jainism) believe that all living things from the smallest bacterium to the largest of mammals are the souls themselves (Atman, jiva) and have their physical representative (the body) in the world. The actual self is the soul, while the body is only a mechanism to experience the karma of that life. Thus if one sees a tiger then there is a self-conscious identity residing in it (the soul), and a physical representative (the whole body of the tiger, which is observable) in the world. Some teach that even non-biological entities (such as rivers and mountains) possess souls. This belief is called animism.[5]

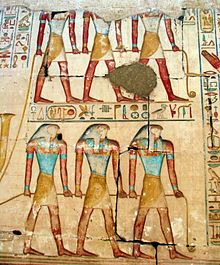

Ancient Near East[edit]

In the ancient Egyptian religion, an individual was believed to be made up of various elements, some physical and some spiritual. Similar ideas are found in ancient Assyrian and Babylonian religion. The Kuttamuwa stele, a funeral stele for an 8th-century BCE royal official from Sam’al, describes Kuttamuwa requesting that his mourners commemorate his life and his afterlife with feasts «for my soul that is in this stele». It is one of the earliest references to a soul as a separate entity from the body. The 800-pound (360 kg) basalt stele is 3 ft (0.91 m) tall and 2 ft (0.61 m) wide. It was uncovered in the third season of excavations by the Neubauer Expedition of the Oriental Institute in Chicago, Illinois.[6]

Baháʼí Faith[edit]

The Baháʼí Faith affirms that «the soul is a sign of God, a heavenly gem whose reality the most learned of men hath failed to grasp, and whose mystery no mind, however acute, can ever hope to unravel».[7] Bahá’u’lláh stated that the soul not only continues to live after the physical death of the human body, but is, in fact, immortal.[8] Heaven can be seen partly as the soul’s state of nearness to God; and hell as a state of remoteness from God. Each state follows as a natural consequence of individual efforts, or the lack thereof, to develop spiritually.[9] Bahá’u’lláh taught that individuals have no existence prior to their life here on earth and the soul’s evolution is always towards God and away from the material world.[9]

Christianity[edit]

According to some Christian eschatology, when people die, their souls will be judged by God and determined to go to Heaven or to Hades awaiting a resurrection. The oldest existing branches of Christianity, the Catholic Church and the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox churches, adhere to this view, as well as many Protestant denominations. Some Protestant Christians understand the soul as «life,” and believe that the dead have no conscious existence until after the resurrection (Christian conditionalism). Some Protestant Christians believe that the souls and bodies of the unrighteous will be destroyed in Hell rather than suffering eternally (annihilationism). Believers will inherit eternal life either in Heaven, or in a Kingdom of God on earth, and enjoy eternal fellowship with God. Other Christians reject the punishment of the soul.

Paul the Apostle used ψυχή (psychē) and πνεῦμα (pneuma) specifically to distinguish between the Jewish notions of נפש (nephesh) and רוח ruah (spirit)[10] (also in the Septuagint, e.g. Genesis 1:2 רוּחַ אֱלֹהִים = πνεῦμα θεοῦ = spiritus Dei = «the Spirit of God»).

Christians generally believe in the existence and eternal, infinite nature of the soul.[11]

Origin of the soul[edit]

The «origin of the soul» has provided a vexing question in Christianity. The major theories put forward include soul creationism, traducianism, and pre-existence. According to soul creationism, God creates each individual soul directly, either at the moment of conception or some later time. According to traducianism, the soul comes from the parents by natural generation. According to the preexistence theory, the soul exists before the moment of conception. There have been differing thoughts regarding whether human embryos have souls from conception, or whether there is a point between conception and birth where the fetus acquires a soul, consciousness, and/or personhood. Stances in this question might play a role in judgements on the morality of abortion.[12][13][14]

Trichotomy of the soul[edit]

Augustine (354-430), one of western Christianity’s most influential early Christian thinkers, described the soul as «a special substance, endowed with reason, adapted to rule the body». Some Christians espouse a trichotomic view of humans, which characterizes humans as consisting of a body (soma), soul (psyche), and spirit (pneuma).[15] However, the majority of modern Bible scholars point out how the concepts of «spirit» and of «soul» are used interchangeably in many biblical passages, and so hold to dichotomy: the view that each human comprises a body and a soul. Paul said that the «body wars against» the soul, «For the word of God is living and active and sharper than any two-edged sword, and piercing as far as the division of soul and spirit» (Heb 4:12 NASB), and that «I buffet my body», to keep it under control.

Views of various denominations[edit]

- Roman Catholicism

The present Catechism of the Catholic Church states that the term soul

- “refers to the innermost aspect of [persons], that which is of greatest value in [them], that by which [they are] most especially in God’s image: ‘soul’ signifies the spiritual principle in [humanity]”.[16]

All souls living and dead will be judged by Jesus Christ when he comes back to earth. The Catholic Church teaches that the existence of each individual soul is dependent wholly upon God:

- «The doctrine of the faith affirms that the spiritual and immortal soul is created immediately by God.»[17]

- Protestantism

Protestants generally believe in the soul’s existence and immortality, but fall into two major camps about what this means in terms of an afterlife. Some, following John Calvin, believe that the soul persists as consciousness after death.[18] Others, following Martin Luther, believe that the soul dies with the body, and is unconscious («sleeps») until the resurrection of the dead.[19][20]

- Adventism

Various new religious movements deriving from Adventism — including Christadelphians,[21] Seventh-day Adventists,[22][23] and Jehovah’s Witnesses[24][25] — similarly believe that the dead do not possess a soul separate from the body and are unconscious until the resurrection.

- Latter-day Saints (‘Mormonism’)

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints teaches that the spirit and body together constitute the Soul of Man (Mankind). «The spirit and the body are the soul of man.»[26] Latter-day Saints believe that the soul is the union of a pre-existing, God-made spirit[27][28][29] and a temporal body, which is formed by physical conception on earth.

After death, the spirit continues to live and progress in the Spirit world until the resurrection, when it is reunited with the body that once housed it. This reuniting of body and spirit results in a perfect soul that is immortal, and eternal, and capable of receiving a fulness of joy.[30][31]

Latter-day Saint cosmology also describes «intelligences» as the essence of consciousness or agency. These are co-eternal with God, and animate the spirits.[32] The union of a newly-created spirit body with an eternally-existing intelligence constitutes a «spirit birth»[citation needed] and justifies God’s title «Father of our spirits».[33][34][35]

Confucianism[edit]

Some Confucian traditions contrast a spiritual soul with a corporeal soul.[36]

Hinduism[edit]

Ātman is a Sanskrit word that means inner self or soul.[37][38][39] In Hindu philosophy, especially in the Vedanta school of Hinduism, Ātman is the first principle,[40] the true self of an individual beyond identification with phenomena, the essence of an individual. In order to attain liberation (moksha), a human being must acquire self-knowledge (atma jnana), which is to realize that one’s true self (Ātman) is identical with the transcendent self Brahman according to Advaita Vedanta.[38][41]

The six orthodox schools of Hinduism believe that there is Ātman (self, essence) in every being.[42]

In Hinduism and Jainism, a jiva (Sanskrit: जीव, jīva, alternative spelling jiwa; Hindi: जीव, jīv, alternative spelling jeev) is a living being, or any entity imbued with a life force.[43]

The concept of jiva in Jainism is similar to atman in Hinduism. However, some Hindu traditions differentiate between the two concepts, with jiva considered as individual self, while atman as that which is universal unchanging self that is present in all living beings and everything else as the metaphysical Brahman.[44][45][46] The latter is sometimes referred to as jiva-atman (a soul in a living body).[44]

Islam[edit]

The Quran, the holy book of Islam, uses two words to refer to the soul: rūḥ (translated as spirit, consciousness, pneuma or «soul») and nafs (translated as self, ego, psyche or «soul»),[47][48] cognates of the Hebrew nefesh and ruach. The two terms are frequently used interchangeably, though rūḥ is more often used to denote the divine spirit or «the breath of life», while nafs designates one’s disposition or characteristics.[49] In Islamic philosophy, the immortal rūḥ «drives» the mortal nafs, which comprises temporal desires and perceptions necessary for living.[citation needed]

Two of the passages in the Quran that mention the rûh occur in chapters 17 («The Night Journey») and 39 («The Troops»):

And they ask you, [O Muhammad], about the Rûh. Say, «The Rûh is of the affair of my Lord. And mankind has not been given of knowledge except a little.

Allah takes the souls at the time of their death, and those that do not die [He takes] during their sleep. Then He keeps those for which He has decreed death and releases the others for a specified term. Indeed in that are signs for a people who give thought..

Jainism[edit]

In Jainism, every living being, from plant or bacterium to human, has a soul and the concept forms the very basis of Jainism. According to Jainism, there is no beginning or end to the existence of soul. It is eternal in nature and changes its form until it attains liberation.

In Jainism, jiva is the immortal essence or soul of a living organism (human, animal, fish or plant etc.) which survives physical death.[50] The concept of Ajiva in Jainism means «not soul», and represents matter (including body), time, space, non-motion and motion.[50] In Jainism, a Jiva is either samsari (mundane, caught in cycle of rebirths) or mukta (liberated).[51][52]

According to this belief until the time the soul is liberated from the saṃsāra (cycle of repeated birth and death), it gets attached to one of these bodies based on the karma (actions) of the individual soul. Irrespective of which state the soul is in, it has got the same attributes and qualities. The difference between the liberated and non-liberated souls is that the qualities and attributes are manifested completely in case of siddha (liberated soul) as they have overcome all the karmic bondages whereas in case of non-liberated souls they are partially exhibited. Souls who rise victorious over wicked emotions while still remaining within physical bodies are referred to as arihants.[53]

Concerning the Jain view of the soul, Virchand Gandhi said

the soul lives its own life, not for the purpose of the body, but the body lives for the purpose of the soul. If we believe that the soul is to be controlled by the body then soul misses its power.[54]

Judaism[edit]

The Hebrew terms נפש nefesh (literally «living being»), רוח ruach (literally «wind»), נשמה neshamah (literally «breath»), חיה chayah (literally «life») and יחידה yechidah (literally «singularity») are used to describe the soul or spirit.[55]

In Judaism the soul is believed to be given by God to Adam as mentioned in Genesis,

Then the LORD God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living being.

- —Genesis 2:7

Judaism relates the quality of one’s soul to one’s performance of the commandments (mitzvot) and reaching higher levels of understanding, and thus closeness to God. A person with such closeness is called a tzadik. Therefore, Judaism embraces the commemoration of the day of one’s death, nahala/Yahrtzeit and not the birthday[56] as a festivity of remembrance, for only toward the end of life’s struggles, tests and challenges could human souls be judged and credited for righteousness.[57] Judaism places great importance on the study of the souls.[58]

Kabbalah and other mystic traditions go into greater detail into the nature of the soul. Kabbalah separates the soul into five elements, corresponding to the five worlds:[59]

- Nefesh, related to natural instinct.

- Ruach, related to intellect and the awareness of God.

- Neshamah, related to emotion and morality.

- Chayah, considered a part of God, as it were.

- Yechidah. This aspect is essentially one with God.

Kabbalah also proposed a concept of reincarnation, the gilgul. (See also nefesh habehamit the «animal soul».)[citation needed]

Some Jewish traditions assert that the soul is housed in the luz bone, though traditions disagree as to whether it is the atlas at the top of the spine, or the sacrum at bottom of the spine.[citation needed]

Scientology[edit]

The Scientology view is that a person does not have a soul, it is a soul. It is the belief of the religion that they do not have the power to force adherents’ conclusions.[60] Therefore, a person is immortal, and may be reincarnated if they wish. Scientologists view that one’s future happiness and immortality, as guided by their spirituality, is influenced by how they live and act during their time on earth.[60] The Scientology term for the soul is «thetan», derived from the Greek word «theta», symbolizing thought. Scientology counselling (called auditing) addresses the soul to improve abilities, both worldly and spiritual. The ideologies surrounding this understanding align with those of the five major world religions.[60]

Shamanism[edit]

Soul dualism (also called «multiple souls» or «dualistic pluralism») is a common belief in Shamanism,[61][62][63] and is essential in the universal and central concept of «soul flight» (also called «soul journey», «out-of-body experience», «ecstasy», or «astral projection»).[64][63][65][66][67] It is the belief that humans have two or more souls, generally termed the «body soul» (or «life soul») and the «free soul». The former is linked to bodily functions and awareness when awake, while the latter can freely wander during sleep or trance states.[62][65][66][67][68] In some cases, there are a plethora of soul types with different functions.[69][70]

Soul dualism and multiple souls are prominent in the traditional animistic beliefs of the Austronesian peoples,[71][72] the Chinese people (hún and pò),[73] the Tibetan people,[61] most African peoples,[74] most Native North Americans,[74][69] ancient South Asian peoples,[63] Northern Eurasian peoples,[67][75] and in Ancient Egyptians (the ka and ba).[74]

The belief in soul dualism is found throughout most Austronesian shamanistic traditions. The reconstructed Proto-Austronesian word for the «body soul» is *nawa («breath», «life», or «vital spirit»). It is located somewhere in the abdominal cavity, often in the liver or the heart (Proto-Austronesian *qaCay).[71][72] The «free soul» is located in the head. Its names are usually derived from Proto-Austronesian *qaNiCu («ghost», «spirit [of the dead]»), which also apply to other non-human nature spirits. The «free soul» is also referred to in names that literally mean «twin» or «double», from Proto-Austronesian *duSa («two»).[76][77] A virtuous person is said to be one whose souls are in harmony with each other, while an evil person is one whose souls are in conflict.[78]

The «free soul» is said to leave the body and journey to the spirit world during sleep, trance-like states, delirium, insanity, and death. The duality is also seen in the healing traditions of Austronesian shamans, where illnesses are regarded as a «soul loss» and thus to heal the sick, one must «return» the «free soul» (which may have been stolen by an evil spirit or got lost in the spirit world) into the body. If the «free soul» can not be returned, the afflicted person dies or goes permanently insane.[79]

In some ethnic groups, there can also be more than two souls. Like among the Tagbanwa people, where a person is said to have six souls – the «free soul» (which is regarded as the «true» soul) and five secondary souls with various functions.[71]

Several Inuit groups believe that a person has more than one type of soul. One is associated with respiration, the other can accompany the body as a shadow.[80] In some cases, it is connected to shamanistic beliefs among the various Inuit groups.[69] Also Caribou Inuit groups believed in several types of souls.[81]

The shaman heals within the spiritual dimension by returning ‘lost’ parts of the human soul from wherever they have gone. The shaman also cleanses excess negative energies, which confuse or pollute the soul.

Shinto[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2021) |

Shinto distinguishes between the souls of living persons (tamashii) and those of dead persons (mitama), each of which may have different aspects or sub-souls.

Sikhism[edit]

Sikhism considers soul (atma) to be part of God (Waheguru). Various hymns are cited from the holy book Guru Granth Sahib (SGGS) that suggests this belief. «God is in the Soul and the Soul is in the God.»[82] The same concept is repeated at various pages of the SGGS. For example: «The soul is divine; divine is the soul. Worship Him with love.»[83] and «The soul is the Lord, and the Lord is the soul; contemplating the Shabad, the Lord is found.»[84]

The atma or soul according to Sikhism is an entity or «spiritual spark» or «light» in the human body — because of which the body can sustain life. On the departure of this entity from the body, the body becomes lifeless – no amount of manipulations to the body can make the person make any physical actions. The soul is the «driver» in the body. It is the roohu or spirit or atma, the presence of which makes the physical body alive.

Many[quantify] religious and philosophical traditions support the view that the soul is the ethereal substance – a spirit; a non-material spark – particular to a unique living being. Such traditions often consider the soul both immortal and innately aware of its immortal nature, as well as the true basis for sentience in each living being. The concept of the soul has strong links with notions of an afterlife, but opinions may vary wildly even within a given religion as to what happens to the soul after death. Many within these religions and philosophies see the soul as immaterial, while others consider it possibly material.

Taoism[edit]

According to Chinese traditions, every person has two types of soul called hun and po (魂 and 魄), which are respectively yang and yin. Taoism believes in ten souls, sanhunqipo (三魂七魄) «three hun and seven po«.[85] A living being that loses any of them is said to have mental illness or unconsciousness, while a dead soul may reincarnate to a disability, lower desire realms, or may even be unable to reincarnate.

Zoroastrianism[edit]

Other religious beliefs and views[edit]

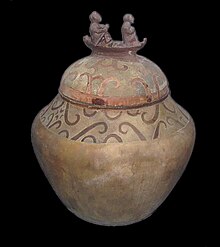

Charon (Greek) who guides dead souls to the Underworld. 4th century BCE.

In theological reference to the soul, the terms «life» and «death» are viewed as emphatically more definitive than the common concepts of «biological life» and «biological death». Because the soul is said to be transcendent of the material existence, and is said to have (potentially) eternal life, the death of the soul is likewise said to be an eternal death. Thus, in the concept of divine judgment, God is commonly said to have options with regard to the dispensation of souls, ranging from Heaven (i.e., angels) to hell (i.e., demons), with various concepts in between. Typically both Heaven and hell are said to be eternal, or at least far beyond a typical human concept of lifespan and time.

According to Louis Ginzberg, the soul of Adam is the image of God.[86] Every soul of human also escapes from the body every night, rises up to heaven, and fetches new life thence for the body of man.[87]

Spirituality, New Age, and new religions[edit]

Brahma Kumaris[edit]

In Brahma Kumaris, human souls are believed to be incorporeal and eternal. God is considered to be the Supreme Soul, with maximum degrees of spiritual qualities, such as peace, love and purity.[88]

Theosophy[edit]

In Helena Blavatsky’s Theosophy, the soul is the field of our psychological activity (thinking, emotions, memory, desires, will, and so on) as well as of the so-called paranormal or psychic phenomena (extrasensory perception, out-of-body experiences, etc.). However, the soul is not the highest, but a middle dimension of human beings. Higher than the soul is the spirit, which is considered to be the real self; the source of everything we call «good»—happiness, wisdom, love, compassion, harmony, peace, etc. While the spirit is eternal and incorruptible, the soul is not. The soul acts as a link between the material body and the spiritual self, and therefore shares some characteristics of both. The soul can be attracted either towards the spiritual or towards the material realm, being thus the «battlefield» of good and evil. It is only when the soul is attracted towards the spiritual and merges with the Self that it becomes eternal and divine.

Anthroposophy[edit]

Rudolf Steiner claimed classical trichotomic stages of soul development, which interpenetrated one another in consciousness:[89]

- The «sentient soul», centering on sensations, drives, and passions, with strong conative (will) and emotional components;

- The «intellectual» or «mind soul», internalizing and reflecting on outer experience, with strong affective (feeling) and cognitive (thinking) components; and

- The «consciousness soul», in search of universal, objective truths.

Miscellaneous[edit]

In Surat Shabda Yoga, the soul is considered to be an exact replica and spark of the Divine. The purpose of Surat Shabd Yoga is to realize one’s True Self as soul (Self-Realisation), True Essence (Spirit-Realisation) and True Divinity (God-Realisation) while living in the physical body.

Similarly, the spiritual teacher Meher Baba held that «Atma, or the soul, is in reality identical with Paramatma the Oversoul – which is one, infinite, and eternal…[and] [t]he sole purpose of creation is for the soul to enjoy the infinite state of the Oversoul consciously.»[90]

Eckankar, founded by Paul Twitchell in 1965, defines Soul as the true self; the inner, most sacred part of each person.[91]

G.I. Gurdjieff taught that humans are not born with immortal souls but could develop them through certain efforts.[92]

Philosophical views[edit]

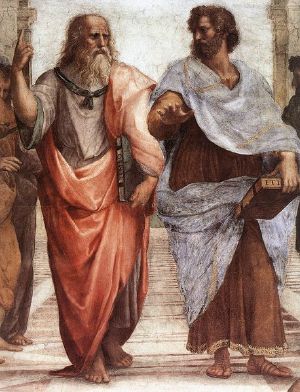

Greek philosophers, such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, understood that the soul (ψυχή psykhḗ) must have a logical faculty, the exercise of which was the most divine of human actions. At his defense trial, Socrates even summarized his teachings as nothing other than an exhortation for his fellow Athenians to excel in matters of the psyche since all bodily goods are dependent on such excellence (Apology 30a–b). Aristotle reasoned that a man’s body and soul were his matter and form respectively: the body is a collection of elements and the soul is the essence.

Soul or psyche (Ancient Greek: ψυχή psykhḗ, of ψύχειν psýkhein, «to breathe», cf. Latin ‘anima’) comprises the mental abilities of a living being: reason, character, free will, feeling, consciousness, qualia, memory, perception, thinking, etc. Depending on the philosophical system, a soul can either be mortal or immortal.[93] The ancient Greeks used the word «ensouled» to represent the concept of being «alive», indicating that the earliest surviving western philosophical view believed that the soul was that which gave the body life.[94] The soul was considered the incorporeal or spiritual «breath» that animates (from the Latin, anima, cf. «animal») the living organism.

Francis M. Cornford quotes Pindar by saying that the soul sleeps while the limbs are active, but when one is sleeping, the soul is active and reveals «an award of joy or sorrow drawing near» in dreams.[95]

Erwin Rohde writes that an early pre-Pythagorean belief presented the soul as lifeless when it departed the body, and that it retired into Hades with no hope of returning to a body.[96]

Plato was the first thinker in antiquity to combine the various functions of the soul into one coherent conception: the soul is that which moves things (i.e., that which gives life, on the view that life is self-motion) by means of its thoughts, requiring that it be both a mover and a thinker.[97]

Socrates and Plato[edit]

Drawing on the words of his teacher Socrates, Plato considered the psyche to be the essence of a person, being that which decides how we behave. He considered this essence to be an incorporeal, eternal occupant of our being. Plato said that even after death, the soul exists and is able to think. He believed that as bodies die, the soul is continually reborn (metempsychosis) in subsequent bodies. However, Aristotle believed that only one part of the soul was immortal, namely the intellect (logos). The Platonic soul consists of three parts:[98]

- the logos, or logistikon (mind, nous, or reason)

- the thymos, or thumetikon (emotion, spiritedness, or masculine)

- the eros, or epithumetikon (appetitive, desire, or feminine)

The parts are located in different regions of the body:

- logos is located in the head, is related to reason and regulates the other part.

- thymos is located near the chest region and is related to anger.

- eros is located in the stomach and is related to one’s desires.

Plato also compares the three parts of the soul or psyche to a societal caste system. According to Plato’s theory, the three-part soul is essentially the same thing as a state’s class system because, to function well, each part must contribute so that the whole functions well. Logos keeps the other functions of the soul regulated.

The soul is at the heart of Plato’s philosophy. Francis Cornford described the twin pillars of Platonism as being the theory of the Forms, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the doctrine of the immortality of the soul.[99] Indeed, Plato was the first person in the history of philosophy to believe that the soul was both the source of life and the mind. In Plato’s dialogues, we find the soul playing many disparate roles.[100] Among other things, Plato believes that the soul is what gives life to the body (which was articulated most of all in the Laws and Phaedrus) in terms of self-motion: to be alive is to be capable of moving yourself; the soul is a self-mover. He also thinks that the soul is the bearer of moral properties (i.e., when I am virtuous, it is my soul that is virtuous as opposed to, say, my body). The soul is also the mind: it is that which thinks in us.

We see this casual oscillation between different roles of the soul in many dialogues. First of all, in the Republic:

Is there any function of the soul that you could not accomplish with anything else, such as taking care of something (epimeleisthai), ruling, and deliberating, and other such things? Could we correctly assign these things to anything besides the soul, and say that they are characteristic (idia) of it?

No, to nothing else.

What about living? Will we deny that this is a function of the soul?

That absolutely is.[101]

The Phaedo most famously caused problems to scholars who were trying to make sense of this aspect of Plato’s theory of the soul, such as Sarah Broadie[102] and Dorothea Frede.[103]

More-recent scholarship has overturned this accusation by arguing that part of the novelty of Plato’s theory of the soul is that it was the first to unite the different features and powers of the soul that became commonplace in later ancient and medieval philosophy.[97] For Plato, the soul moves things by means of its thoughts, as one scholar puts it, and accordingly, the soul is both a mover (i.e., the principle of life, where life is conceived of as self-motion) and a thinker.[97]

Aristotle[edit]

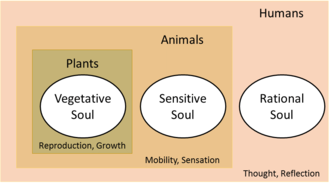

The structure of the souls of plants, animals, and humans, according to Aristotle, with Bios, Zoê, and Psūchê

Aristotle (384–322 BCE) defined the soul, or Psūchê (ψυχή), as the «first actuality» of a naturally organized body,[104] and argued against its separate existence from the physical body. In Aristotle’s view, the primary activity, or full actualization, of a living thing constitutes its soul. For example, the full actualization of an eye, as an independent organism, is to see (its purpose or final cause).[105] Another example is that the full actualization of a human being would be living a fully functional human life in accordance with reason (which he considered to be a faculty unique to humanity).[106] For Aristotle, the soul is the organization of the form and matter of a natural being which allows it to strive for its full actualization. This organization between form and matter is necessary for any activity, or functionality, to be possible in a natural being. Using an artifact (non-natural being) as an example, a house is a building for human habituation, but for a house to be actualized requires the material (wood, nails, bricks, etc.) necessary for its actuality (i.e. being a fully functional house). However, this does not imply that a house has a soul. In regards to artifacts, the source of motion that is required for their full actualization is outside of themselves (for example, a builder builds a house). In natural beings, this source of motion is contained within the being itself.[107] Aristotle elaborates on this point when he addresses the faculties of the soul.

The various faculties of the soul, such as nutrition, movement (peculiar to animals), reason (peculiar to humans), sensation (special, common, and incidental) and so forth, when exercised, constitute the «second» actuality, or fulfillment, of the capacity to be alive. For example, someone who falls asleep, as opposed to someone who falls dead, can wake up and live their life, while the latter can no longer do so.

Aristotle identified three hierarchical levels of natural beings: plants, animals, and people, having three different degrees of soul: Bios (life), Zoë (animate life), and Psuchë (self-conscious life). For these groups, he identified three corresponding levels of soul, or biological activity: the nutritive activity of growth, sustenance and reproduction which all life shares (Bios); the self-willed motive activity and sensory faculties, which only animals and people have in common (Zoë); and finally «reason», of which people alone are capable (Pseuchë).

Aristotle’s discussion of the soul is in his work, De Anima (On the Soul). Although mostly seen as opposing Plato in regard to the immortality of the soul, a controversy can be found in relation to the fifth chapter of the third book: in this text both interpretations can be argued for, soul as a whole can be deemed mortal, and a part called «active intellect» or «active mind» is immortal and eternal.[108] Advocates exist for both sides of the controversy, but it has been understood that there will be permanent disagreement about its final conclusions, as no other Aristotelian text contains this specific point, and this part of De Anima is obscure.[109] Further, Aristotle states that the soul helps humans find the truth, and understanding the true purpose or role of the soul is extremely difficult.[110]

Avicenna and Ibn al-Nafis[edit]

Following Aristotle, Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and Ibn al-Nafis, an Arab physician, further elaborated upon the Aristotelian understanding of the soul and developed their own theories on the soul. They both made a distinction between the soul and the spirit, and the Avicennian doctrine on the nature of the soul was influential among the Scholastics. Some of Avicenna’s views on the soul include the idea that the immortality of the soul is a consequence of its nature, and not a purpose for it to fulfill. In his theory of «The Ten Intellects», he viewed the human soul as the tenth and final intellect.[111][112]

While he was imprisoned, Avicenna wrote his famous «Floating man» thought experiment to demonstrate human self-awareness and the substantial nature of the soul.[113] He told his readers to imagine themselves suspended in the air, isolated from all sensations, which includes no sensory contact with even their own bodies. He argues that in this scenario one would still have self-consciousness. He thus concludes that the idea of the self is not logically dependent on any physical thing, and that the soul should not be seen in relative terms, but as a primary given, a substance. This argument was later refined and simplified by René Descartes in epistemic terms, when he stated: «I can abstract from the supposition of all external things, but not from the supposition of my own consciousness.»[114]

Avicenna generally supported Aristotle’s idea of the soul originating from the heart, whereas Ibn al-Nafis rejected this idea and instead argued that the soul «is related to the entirety and not to one or a few organs». He further criticized Aristotle’s idea whereby every unique soul requires the existence of a unique source, in this case the heart. Al-Nafis concluded that «the soul is related primarily neither to the spirit nor to any organ, but rather to the entire matter whose temperament is prepared to receive that soul,» and he defined the soul as nothing other than «what a human indicates by saying «I».[115]

Thomas Aquinas[edit]

Following Aristotle (whom he referred to as «the Philosopher») and Avicenna, Thomas Aquinas (1225–74) understood the soul to be the first actuality of the living body. Consequent to this, he distinguished three orders of life: plants, which feed and grow; animals, which add sensation to the operations of plants; and humans, which add intellect to the operations of animals.

Concerning the human soul, his epistemological theory required that, since the knower becomes what he knows, the soul is definitely not corporeal—if it is corporeal when it knows what some corporeal thing is, that thing would come to be within it.[116] Therefore, the soul has an operation which does not rely on a body organ, and therefore the soul can exist without a body. Furthermore, since the rational soul of human beings is a subsistent form and not something made of matter and form, it cannot be destroyed in any natural process.[117] The full argument for the immortality of the soul and Aquinas’ elaboration of Aristotelian theory is found in Question 75 of the First Part of the Summa Theologica.

Aquinas affirmed in the doctrine of the divine effusion of the soul, the particular judgement of the soul after the separation from a dead body, and the final Resurrection of the flesh. He recalled two canons of the 4th-century De Ecclesiasticis Dogmatibus for which «the rational soul is not engendered by coition» (canon XIV)[118] and «is one and the same soul in man, that both gives life to the body by being united to it, and orders itself by its own reasoning.»[119] Moreover, he believed in a unique and tripartite soul, within which are distinctively present a nutritive, a sensitive and intellectual soul. The latter is created by God and is taken solely by human beings, includes the other two types of soul and makes the sensitive soul incorruptible.[120]

Immanuel Kant[edit]

In his discussions of rational psychology, Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) identified the soul as the «I» in the strictest sense, and argued that the existence of inner experience can neither be proved nor disproved.

We cannot prove a priori the immateriality of the soul, but rather only so much: that all properties and actions of the soul cannot be recognized from materiality.

It is from the «I», or soul, that Kant proposes transcendental rationalization, but cautions that such rationalization can only determine the limits of knowledge if it is to remain practical.[121]

Philosophy of mind[edit]

Gilbert Ryle’s ghost in the machine argument, which is a rejection of Descartes’s mind–body dualism, can provide a contemporary understanding of the soul/mind, and the problem concerning its connection to the brain/body.[122]

Psychology[edit]

Soul belief prominently figues in Otto Rank’s work recovering the importance of immortality in the psychology of primitive, classical and modern interest in life and death. Rank’s work directly opposed the «scientific» psychology that concedes the possibility of the soul’s existence and postulates it as an object of research without really admitting that it exists. «Just as religion represents a psychological commentary on the social evolution of man, various psychologies represent our current attitudes toward spiritual belief. In the animistic era, psychologizing was a creating of the soul; in the religious era, it was a representing of the soul to one’s self; in our era of natural science it is a knowing of the individual soul.» [123] Rank’s «Seelenglaube» translates to «Soul Belief». Rank’s work had a significant influence on Ernest Becker’s understanding of a universal interest in immortality. In Denial of Death, Becker describes «soul» in terms of Kierkegaard’s use of «self» when he says, «what we call schizophrenia is an attempt by the symbolic self to deny the limitations of the finite body.»[124]

† Kierkegaard’s use of «self» may be a bit confusing. He uses it to include

the symbolic self and the physical body. It is a synonym really for «total

personality» that goes beyond the person to include what we would now call

the «soul» or the «ground of being» out of which the created person sprang.

Science[edit]

According to Julien Musolino, the vast majority of scientists hold that the mind is a complex machine that operates on the same physical laws as all other objects in the universe.[125] According to Musolino, there is currently no scientific evidence whatsoever to support the existence of the soul.[125]

The search for the soul, however, is seen to have been instrumental in driving the understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the human body, particularly in the fields of cardiovascular and neurology.[126] In the two dominant conflicting concepts of the soul – one seeing it to be spiritual and immortal, and the other seeing it to be material and mortal, both have described the soul as being located in a particular organ or as pervading the whole body.[126]

Neuroscience[edit]

Neuroscience as an interdisciplinary field, and its branch of cognitive neuroscience particularly, operates under the ontological assumption of physicalism. In other words, it assumes that only the fundamental phenomena studied by physics exist. Thus, neuroscience seeks to understand mental phenomena within the framework according to which human thought and behavior are caused solely by physical processes taking place inside the brain, and it operates by the way of reductionism by seeking an explanation for the mind in terms of brain activity.[127][128]

To study the mind in terms of the brain several methods of functional neuroimaging are used to study the neuroanatomical correlates of various cognitive processes that constitute the mind. The evidence from brain imaging indicates that all processes of the mind have physical correlates in brain function.[129] However, such correlational studies cannot determine whether neural activity plays a causal role in the occurrence of these cognitive processes (correlation does not imply causation) and they cannot determine if the neural activity is either necessary or sufficient for such processes to occur. Identification of causation, and of necessary and sufficient conditions requires explicit experimental manipulation of that activity. If manipulation of brain activity changes consciousness, then a causal role for that brain activity can be inferred.[130][131] Two of the most common types of manipulation experiments are loss-of-function and gain-of-function experiments. In a loss-of-function (also called «necessity») experiment, a part of the nervous system is diminished or removed in an attempt to determine if it is necessary for a certain process to occur, and in a gain-of-function (also called «sufficiency») experiment, an aspect of the nervous system is increased relative to normal.[132] Manipulations of brain activity can be performed with direct electrical brain stimulation, magnetic brain stimulation using transcranial magnetic stimulation, psychopharmacological manipulation, optogenetic manipulation, and by studying the symptoms of brain damage (case studies) and lesions. In addition, neuroscientists are also investigating how the mind develops with the development of the brain.[133]

Physics[edit]

Physicist Sean M. Carroll has written that the idea of a soul is incompatible with quantum field theory (QFT). He writes that for a soul to exist: «Not only is new physics required, but dramatically new physics. Within QFT, there can’t be a new collection of ‘spirit particles’ and ‘spirit forces’ that interact with our regular atoms, because we would have detected them in existing experiments.»[134]

Quantum indeterminism has been invoked as an explanatory mechanism for possible soul/brain interaction, but neuroscientist Peter Clarke found errors with this viewpoint, noting there is no evidence that such processes play a role in brain function; Clarke concluded that a Cartesian soul has no basis from quantum physics.[135][need quotation to verify]

Parapsychology[edit]

Some parapsychologists have attempted to establish, by scientific experiment, whether a soul separate from the brain exists, as is more commonly defined in religion rather than as a synonym of psyche or mind. Milbourne Christopher (1979) and Mary Roach (2010) have argued that none of the attempts by parapsychologists have yet succeeded.[136][137]

Weight of the soul[edit]

In 1901 Duncan MacDougall conducted an experiment in which he made weight measurements of patients as they died. He claimed that there was weight loss of varying amounts at the time of death; he concluded the soul weighed 21 grams, based on measurements of a single patient and discarding conflicting results.[138][139] The physicist Robert L. Park wrote that MacDougall’s experiments «are not regarded today as having any scientific merit» and the psychologist Bruce Hood wrote that «because the weight loss was not reliable or replicable, his findings were unscientific.»[140][141]

See also[edit]

- Ancient Egyptian concept of the soul

- Being

- Chinese room

- Ekam

- History of the location of the soul

- Kami

- Knowledge argument

- Metaphysical naturalism

- Mind–body problem

- Nafs in Islam

- Nishimta in Mandaeism

- The Over-Soul (essay)

- Paramatman (or oversoul)

- Philosophical zombie

- Open individualism

- Qualia

- Self

- Self-awareness

- Shade (mythology)

- Soul dualism

- Soul flight

- Spirit (vital essence) (seen as a synonym of soul)

- Substance dualism

- Vitalism

- Vertiginous question

References[edit]

- ^ «soul». Britannica. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «soul, n.» OED Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ «Immortality of the Soul». www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Peter Eardley and Carl Still, Aquinas: A Guide for the Perplexed (London: Continuum, 2010), pp. 34–35

- ^ «Soul», The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–07. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ «Found: An Ancient Monument to the Soul». The New York Times. 17 November 2008. Archived from the original on 24 April 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

In a mountainous kingdom in what is now southeastern Turkey, there lived in the eighth century B.C. a royal official, Kuttamuwa, who oversaw the completion of an inscribed stone monument, or stele, to be erected upon his death. The words instructed mourners to commemorate his life and afterlife with feasts «for my soul that is in this stele.»

- ^ Bahá’u’lláh (1976). Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh. Wilmette, Illinois: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 158–63. ISBN 978-0-87743-187-9. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Bahá’u’lláh (1976). Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh. Wilmette, Illinois: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 155–58. ISBN 978-0-87743-187-9. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ a b Taherzadeh, Adib (1976). The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, Volume 1. Oxford: George Ronald. ISBN 978-0-85398-270-8. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Αρχιμ. Βλάχος, Ιερόθεος (30 September 1985). «Κεφάλαιο Γ’» (PDF). Ορθόδοξη Ψυχοθεραπεία (in Greek). Εδεσσα. p. Τι είναι η ψυχή. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Harari, Yuval N. (2017). Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (1st US ed.). New York: Harper. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-06-246431-6. OCLC 951507538.

- ^ ««Do Embryos Have Souls?», Father Tadeusz Pacholczyk, PhD, Catholic Education Resource Center». Catholiceducation.org. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Matthew Syed (12 May 2008). «Embryos have souls? What nonsense». The Times. UK. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ «The Soul of the Embryo: An Enquiry into the Status of the Human Embryo in the Christian Tradition», by David Albert Jones, Continuum Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-8264-6296-1

- ^ «Soul». newadvent.org. 1 July 1912. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

In St. Paul we find a more technical phraseology employed with great consistency. Psyche is now appropriated to the purely natural life; pneuma to the life of supernatural religion, the principle of which is the Holy Spirit, dwelling and operating in the heart. The opposition of flesh and spirit is accentuated afresh (Romans 1:18, etc.). This Pauline system, presented to a world already prepossessed in favour of a quasi-Platonic Dualism, occasioned one of the earliest widespread forms of error among Christian writers – the doctrine of the Trichotomy. According to this, man, perfect man (teleios) consists of three parts: body, soul, spirit (soma, psyche, pneuma).

- ^ «paragraph 363». Catechism of the Catholic Church. Retrieved 1 March 2023 – via Vatican.va.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «paragraph 382». Catechism of the Catholic Church. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011 – via Vatican.va.

- ^ Helm, Paul (2006). John Calvin’s Ideas. p. 129.

The Immortality of the Soul: As we saw when discussing Calvin’s Christology, Calvin is a substance dualist.

- ^ Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W.; Settis, Salvatore (2010). The Classical Tradition. p. 480.

On several occasions, Luther mentioned contemptuously that the Council Fathers had decreed the soul immortal.

- ^ Marius, Richard (1999). Martin Luther: The Christian between God and death. p. 429.

Luther, believing in soul sleep at death, held here that in the moment of resurrection … the righteous will rise to meet Christ in the air, the ungodly will remain on earth for judgment, …

- ^ «Birmingham Amended Statement of Faith». Archived from the original on 16 February 2014.

- ^ «Soul Sleep | Adventist Review». adventistreview.org. 3 September 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ beckettj. «What Is Your Soul, According to the Bible?». Adventist.org. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ «Do you have an immortal soul?». The Watchtower. 15 July 2007. p. 3. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014.

- ^ What Does the Bible Really Teach?. p. 211.

- ^ «88:15». Doctrine and Covenants. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints – via Google Books.

And the spirit and the body is the soul of man.

- ^ «6:51». Moses. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 23 February 2016 – via churchofjesuschrist.org.

- ^ «12:9». Hebrews. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 23 February 2016 – via churchofjesuschrist.org.

- ^ «131:7–8». Doctrine and Covenants. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints – via churchofjesuschrist.org.

Joseph Smith goes so far as to say that these spirits are made of a finer matter that we cannot see in our current state

- ^ «Alma». Book of Mormon. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 5:15; 11:43–45; 40:23; 41:2.

- ^ «93:33–34». Doctrine and Covenants – via churchofjesuschrist.org.

- ^ «93:29–30». Doctrine and Covenants. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints – via churchofjesuschrist.org.

- ^ «Chapter 37: Joseph F. Smith». Teachings of Presidents of the Church. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2011. pp. 331–338.

- ^ «Spirit». Guide to the Scriptures. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 7 April 2014 – via churchofjesuschrist.org.

- ^

«Chapter 41: The Postmortal Spirit World». Gospel Principles. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 23 February 2016 – via churchofjesuschrist.org. - ^

Boot, W.J. (2014). «3: Spirits, Gods and Heaven in Confucian thought». In Huang, Chun-chieh; Tucker, John Allen (eds.). Dao Companion to Japanese Confucian Philosophy. Dao Companions to Chinese Philosophy. Vol. 5. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 83. ISBN 9789048129218. Retrieved 27 April 2019.[…] Confucius combines qi with the divine and the essential, and the corporeal soul with ghosts, opposes the two (as yang against yin, spiritual soul against corporal soul) and explains that after death the first will rise up, and the second will return to the earth, while the flesh and bones will disintegrate.

- ^ [a] Atman Archived 23 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Dictionaries, Oxford University Press (2012), Quote: «1. real self of the individual; 2. a person’s soul»;

[b] John Bowker (2000), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-280094-7, See entry for Atman;

[c] WJ Johnson (2009), A Dictionary of Hinduism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-861025-0, See entry for Atman (self). - ^ a b David Lorenzen (2004), The Hindu World (Editors: Sushil Mittal and Gene Thursby), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-21527-7, pp. 208–09, Quote: «Advaita and nirguni movements, on the other hand, stress an interior mysticism in which the devotee seeks to discover the identity of individual soul (atman) with the universal ground of being (brahman) or to find god within himself».

- ^ Chad Meister (2010), The Oxford Handbook of Religious Diversity, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-534013-6, p. 63; Quote: «Even though Buddhism explicitly rejected the Hindu ideas of Atman («soul») and Brahman, Hinduism treats Sakyamuni Buddha as one of the ten avatars of Vishnu.»

- ^ Deussen, Paul and Geden, A.S. The Philosophy of the Upanishads. Cosimo Classics (1 June 2010). p. 86. ISBN 1-61640-240-7.

- ^ Richard King (1995), Early Advaita Vedanta and Buddhism, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-2513-8, p. 64, Quote: «Atman as the innermost essence or soul of man, and Brahman as the innermost essence and support of the universe. (…) Thus we can see in the Upanishads, a tendency towards a convergence of microcosm and macrocosm, culminating in the equating of atman with Brahman».

- ^ K. N. Jayatilleke (2010), Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge, ISBN 978-81-208-0619-1, pp. 246–49, from note 385 onwards; Steven Collins (1994), Religion and Practical Reason (Editors: Frank Reynolds, David Tracy), State Univ of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-2217-5, p. 64; «Central to Buddhist soteriology is the doctrine of not-self (Pali: anattā, Sanskrit: anātman, the opposed doctrine of ātman is central to Brahmanical thought). Put very briefly, this is the [Buddhist] doctrine that human beings have no soul, no self, no unchanging essence.»; Edward Roer (Translator), Shankara’s Introduction, p. 2, at Google Books to Brihad Aranyaka Upanishad, pp. 2–4; Katie Javanaud (2013), Is The Buddhist ‘No-Self’ Doctrine Compatible With Pursuing Nirvana? Archived 6 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Philosophy Now

- ^ Matthew Hall (2011). Plants as Persons: A Philosophical Botany. State University of New York Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-4384-3430-8.

- ^ a b Jean Varenne (1989). Yoga and the Hindu Tradition. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 45–47. ISBN 978-81-208-0543-9.

- ^ Michael Myers (2013). Brahman: A Comparative Theology. Routledge. pp. 140–43. ISBN 978-1-136-83565-0.

- ^ McLean, George F.; Meynell, Hugo Anthony (1988). The Philosophy of Person: Solidarity and Cultural Creativity, Jozef Tischner and George McClean, 1994, p. 32. ISBN 9780819169266.

- ^ Deuraseh, Nurdeen; Abu Talib, Mansor (2005). «Mental health in Islamic medical tradition». The International Medical Journal. 4 (2): 76–79.

- ^ Bragazzi, NL; Khabbache, H; et al. (2018). «Neurotheology of Islam and Higher Consciousness States». Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy. 14 (2): 315–21.

- ^ Th. Emil Homerin (2006). «Soul». In Jane Dammen McAuliffe (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. Vol. 5. Brill.

- ^ a b J Jaini (1940). Outlines of Jainism. Cambridge University Press. pp. xxii–xxiii.

- ^ Jaini, Jagmandar-lāl (1927), Gommatsara Jiva-kanda, p. 54 Alt URL

- ^ Sarao, K.T.S.; Long, Jeffery D., eds. (2017). «Jīva (Jainism)». Buddhism and Jainism. Encyclopedia of Indian Religions. Springer Netherlands. p. 594. doi:10.1007/978-94-024-0852-2_100397. ISBN 978-94-024-0851-5.

- ^ Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001). Aspects of Jaina religion (3 ed.). Bharatiya Jnanpith. pp. 15–16. ISBN 81-263-0626-2.

- ^ «Forgotten Gandhi, Virchand Gandhi (1864–1901) – Advocate of Universal Brotherhood». All Famous Quotes. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- ^ Zohar, Rayah Mehemna, Terumah 158b. See Leibowitz, Aryeh (2018). The Neshamah: A Study of the Human Soul. Feldheim Publishers. pp. 27, 110. ISBN 1-68025-338-7

- ^ The only person mentioned in the Torah celebrating birthday (party) is the wicked pharaoh of Egypt Genesis 40:20–22.

- ^ «About Jewish Birthdays». Judaism 101. Aish.com. Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ «Soul». jewishencyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016.

- ^ «Nurturing The Human Soul—From Cradle To Grave». Chizuk Shaya: Dvar Torah Resource. 6 January 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ a b c «Views on Heaven or Hell, Individuals as Eternal Spiritual Beings: Official Church of Scientology». Official Church of Scientology: What is Scientology?. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ a b Sumegi, Angela (2008). Dreamworlds of Shamanism and Tibetan Buddhism: The Third Place. SUNY Press. p. 16. ISBN 9780791478264.

- ^ a b Bock, Nona J.T. (2005). Shamanic techniques: their use and effectiveness in the practice of psychotherapy (PDF) (MSc). University of Wisconsin-Stout.

- ^ a b c Drobin, Ulf (2016). «Introduction». In Jackson, Peter (ed.). Horizons of Shamanism (PDF). Stockholm University Press. pp. xiv–xvii. ISBN 978-91-7635-024-9.

- ^ Hoppál, Mihály (2007). Shamans and Traditions. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 17–26. ISBN 978-963-05-8521-7.

- ^ a b Winkelman, Michael James (2016). «Shamanism and the Brain». In Niki, Kasumi-Clements (ed.). Religion: Mental Religion. Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 355–372. ISBN 9780028663609.

- ^ a b Winkelman, Michael (2002). «Shamanic universals and evolutionary psychology». Journal of Ritual Studies. 16 (2): 63–76. JSTOR 44364143.

- ^ a b c Hoppál, Mihály. «Nature worship in Siberian shamanism».

- ^ «Great Basin Indian». Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2007.

- ^ a b c Merkur, Daniel (1985). Becoming Half Hidden / Shamanism and Initiation among the Inuit. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. pp. 61, 222–223, 226, 240. ISBN 91-22-00752-0.

- ^ Kulmar, Tarmo [in Estonian]. «Conceptions of soul in old-Estonian religion».

- ^ a b c Tan, Michael L. (2008). Revisiting Usog, Pasma, Kulam. University of the Philippines Press. ISBN 9789715425704.

- ^ a b Clifford Sather (2018). «A work of love: Awareness and expressions of emotion in a Borneo healing ritual». In James J. Fox (ed.). Expressions of Austronesian Thought and Emotions. ANU Press. pp. 57–63. ISBN 9781760461928.

- ^ Harrell, Stevan (1979). «The Concept of Soul in Chinese Folk Religion». The Journal of Asian Studies. 38 (3): 519–528. doi:10.2307/2053785. JSTOR 2053785. S2CID 162507447.

- ^ a b c McClelland, Norman C. (2010). Encyclopedia of Reincarnation and Karma. McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 251, 258. ISBN 978-0-7864-4851-7.

- ^ Hoppál, Mihály (1994). Sámánok. Lelkek és jelképek [«Shamans / Souls and symbols»]. Budapest: Helikon Kiadó. p. 225. ISBN 963-208-298-2.

- ^ Yu, Jose Vidamor B. (2000). Inculturation of Filipino-Chinese Culture Mentality. Interreligious and Intercultural Investigations. Vol. 3. Editrice Pontifica Universita Gregoriana. pp. 148–149. ISBN 9788876528484.

- ^ Robert Blust; Stephen Trussel. «*du». Austronesian Comparative Dictionary. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ Leonardo N. Mercado (1991). «Soul and Spirit in Filipino Thought». Philippine Studies. 39 (3): 287–302. JSTOR 42633258.

- ^ Zeus A. Salazar (2007). «Faith healing in the Philippines: An historical perspective» (PDF). Asian Studies. 43 (2v): 1–15.

- ^ Kleivan & Sonne 1985, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Gabus 1970, p. 211.

- ^ SGGS, M 1, p. 1153.

- ^ SGGS, M 4, p. 1325.

- ^ SGGS, M 1, p. 1030.

- ^ «Encyclopedia of Death and Dying (2008)». Deathreference.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews Vol I, Chapter II: Adam Archived 1 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine (Translated by Henrietta Szold) Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

Citation: God had fashioned his (Adam’s) soul with particular care. She is the image of God, and as God fills the world, so the soul fills the human body; as God sees all things, and is seen by none, so the soul sees, but cannot be seen; as God guides the world, so the soul guides the body; as God in His holiness is pure, so is the soul; and as God dwells in secret, so doth the soul. - ^ Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews Vol I, Chapter II: The Soul of Man Archived 1 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine (Translated by Henrietta Szold) Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

- ^ Ramsay, Tamasin (September 2010). Custodians of Purity An Ethnography of the Brahma Kumaris (Thesis). Monash University. p. 105.

- ^ Creeger, Rudolf Steiner; translated by Catherine E. (1994). Theosophy: an introduction to the spiritual processes in human life and in the cosmos (3rd ed.). Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press. pp. 42–46. ISBN 978-0-88010-373-2.

- ^ Baba, Meher. (1987). Discourses. Myrtle Beach, SC: Sheriar Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-880619-09-4.

- ^ Klemp, H. (2009). The call of soul. Minneapolis, MN: Eckankar

- ^ Gurdjieff, George Ivanovitch (25 February 1999). Life is real only then, when ‘I am’. London. ISBN 978-0-14-019585-9. OCLC 41073474.

- ^ «Soul (noun)». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 1 December 2016. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Lorenz, Hendrik (2009). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2009 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Francis M. Cornford, Greek Religious Thought, p. 64, referring to Pindar, Fragment 131.

- ^ Erwin Rohde, Psyche, 1928.

- ^ a b c Campbell, Douglas (2021). «Self‐Motion and Cognition: Plato’s Theory of the Soul». The Southern Journal of Philosophy. 59: 523–544.

- ^ Jones, David (2009). The Gift of Logos: Essays in Continental Philosophy. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-1-4438-1825-4. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Cornford, Francis (1941). The Republic of Plato. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. xxv.

- ^ Campbell, Douglas (2021). «Self‐Motion and Cognition: Plato’s Theory of the Soul». The Southern Journal of Philosophy. 59: 523–544

- ^ Plato, Republic, Book 1, 353d. Translation found in Campbell 2021: 523.

- ^ Broadie, Sarah. 2001. “Soul and Body in Plato and Descartes.” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 101: 295–308.

- ^ Frede, Dorothea. 1978. «The Final Proof of the Immortality of the Soul in Plato’s Phaedo 102a–107a». Phronesis, 23.1: 27–41.

- ^ Aristotle. On The Soul. p. 412b5.

- ^ Aristotle. Physics. Book VIII, Chapter 5, pp. 256a5–22.

- ^ Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Book I, Chapter 7, pp. 1098a7–17.

- ^ Aristotle. Physics. Book III, Chapter 1, pp. 201a10–25.

- ^ Aristotle. On The Soul. Book III, Chapter 5, pp. 430a24–25.

- ^ Shields, Christopher (2011). «supplement: The Active Mind of De Anima iii 5)». Aristotle’s Psychology. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Smith, J. S. (Trans) (1973). Introduction to Aristotle. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 155–59.

- ^ Nahyan A.G. Fancy (2006), «Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288)», pp. 209–10 (Electronic Theses and Dissertations, University of Notre Dame).

- ^ «Arabic and Islamic Psychology and Philosophy of Mind». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 29 May 2012.

- ^ «Floating Man – The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia». www.artandpopularculture.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ Seyyed Hossein Nasr and Oliver Leaman (1996), History of Islamic Philosophy, p. 315, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-13159-6.

- ^ Nahyan A.G. Fancy (2006). Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, University of Notre Dame (Thesis). University of Notre Dame. pp. 209–210. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015.

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas. «Quaestiones Disputatae de Veritate» (in Latin). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas. «Super Boetium De Trinitate» (in Latin). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Cited in «Summa Th. 1:118:2, Objection 4».

- ^ Summa Theologiae of St Thomas Aquinas — Pars I — Quaestio 76 — Article 3. Whether besides the intellectual soul there are in man other souls essentially different from one another?. Translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. 1920. Full citation of the canon: Nor do we say that there are two souls in one man, as James and other Syrians write; one, animal, by which the body is animated, and which is mingled with the blood; the other, spiritual, which obeys the reason; but we say that it is one and the same soul in man, that both gives life to the body by being united to it, and orders itself by its own reasoning.

- ^ Summa th. , Pars I, Quaestion 76, Article 3, Reply to Objection 1.

- ^

Immanuel Kant proposed the existence of certain mathematical truths (2+2 = 4)m that are not tied to matter, or soul.

Bishop, Paul (2000). Synchronicity and Intellectual Intuition in Kant, Swedenborg, and Jung. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. pp. 262–67. ISBN 978-0-7734-7593-9.

- ^ Ryle, Gilbert (1949). The Concept of Mind. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Rank, Otto (1950). Psychology and the Soul, Otto Rank’s Seelenglaube und Psychologie, translated by William D. Turner. Philadelphia. p. 11.

- ^ *Becker, Ernest (1973). The Denial of Death. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 76. ISBN 0-684-83240-2.

- ^ a b Musolino, Julien (2015). The Soul Fallacy: What Science Shows We Gain from Letting Go of Our Soul Beliefs. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. pp. 21–38. ISBN 978-1-61614-962-8.

- ^ a b Santoro, G; Wood, MD; Merlo, L; Anastasi, GP; Tomasello, F; Germanò, A (October 2009). «The anatomic location of the soul from the heart, through the brain, to the whole body, and beyond: a journey through Western history, science, and philosophy». Neurosurgery. 65 (4): 633–43, discussion 643. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000349750.22332.6A. PMID 19834368. S2CID 27566267.

- ^ O. Carter Snead. «Cognitive Neuroscience and the Future of Punishment Archived 5 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine» (2010).

- ^ Kandel, ER; Schwartz JH; Jessell TM; Siegelbaum SA; Hudspeth AJ. «Principles of Neural Science, Fifth Edition» (2012).

- ^ Andrea Eugenio Cavanna, Andrea Nani, Hal Blumenfeld, Steven Laureys. «Neuroimaging of Consciousness» (2013).

- ^ Farah, Martha J.; Murphy, Nancey (February 2009). «Neuroscience and the Soul». Science. 323 (5918): 1168. doi:10.1126/science.323.5918.1168a. PMID 19251609. S2CID 6636610.

- ^ Max Velmans, Susan Schneider. «The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness» (2008). p. 560.

- ^ Matt Carter, Jennifer C. Shieh. «Guide to Research Techniques in Neuroscience» (2009).

- ^ Squire, L. et al. «Fundamental Neuroscience, 4th edition» (2012). Chapter 43.

- ^ Carroll, Sean M. (2011). «Physics and the Immortality of the Soul» Archived 6 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Scientific American. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- ^

Clarke, Peter. (2014). Neuroscience, Quantum Indeterminism and the Cartesian Soul Archived 10 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Brain and cognition 84: 109–17. - ^ Milbourne Christopher. (1979). Search for the Soul: An Insider’s Report on the Continuing Quest by Psychics and Scientists for Evidence of Life After Death. Thomas Y. Crowell, Publishers.

- ^ Mary Roach. (2010). Spook: Science Tackles the Afterlife. Canongate Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84767-080-9

- ^ MacDougall, Duncan (1907). «The Soul: Hypothesis Concerning Soul Substance Together with Experimental Evidence of the Existence of Such Substance». American Medicine. New Series. 2: 240–43.

- ^ «How much does the soul weights?». Live Science. December 2012. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016.

- ^ Park, Robert L. (2009). Superstition: Belief in the Age of Science. Princeton University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-691-13355-3

- ^ Hood, Bruce. (2009). Supersense: From Superstition to Religion – The Brain Science of Belief. Constable. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-84901-030-6

Further reading[edit]

- Batchelor, Stephen. (1998). Buddhism Without Beliefs. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Bellarmine, Robert (1902). «Sermon 47: The Value of the Soul.» . Sermons from the Latins. Benziger Brothers.

- Bremmer, Jan (1983). The Early Greek Concept of the Soul. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-03131-6. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- Chalmers, David. J. (1996). The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory, New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Christopher, Milbourne. (1979). Search for the Soul: An Insider’s Report on the Continuing Quest By Psychics & Scientists For Evidence of Life After Death. Thomas Y. Crowell, Publishers.

- Clarke, Peter (2014). «Neuroscience, Quantum Indeterminism and the Cartesian Soul». Brain and Cognition. 84 (1): 109–17. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2013.11.008. PMID 24355546. S2CID 895046.

- Hood, Bruce. (2009). Supersense: From Superstition to Religion – The Brain Science of Belief. Constable. ISBN 978-1-84901-030-6

- McGraw, John J. (2004). Brain & Belief: An Exploration of the Human Soul. Aegis Press.

- Martin, Michael; Augustine, Keith. (2015). The Myth of an Afterlife: The Case against Life After Death. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-8677-3

- Park, Robert L. (2009). Superstition: Belief in the Age of Science. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13355-3

- Rohde, Erwin. (1925). Psyche: The Cult of Souls and Belief in Immortality Among the Greeks, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., Ltd.

- Ryle, Gilbert. (1949) The Concept of Mind, London: Hutchinson.

- Spenard, Michael (2011) «Dueling with Dualism: the forlorn quest for the immaterial soul», essay. An historical account of mind-body duality and a comprehensive conceptual and empirical critique on the position. ISBN 978-0-578-08288-2

- Swinburne, Richard. (1997). The Evolution of the Soul. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Leibowitz, Aryeh. (2018). The Neshama: A Study of the Human Soul. Feldheim Publishers. ISBN 1-68025-338-7

- Kleivan, Inge; Sonne, B. (1985). «Arctic peoples». Eskimos. Greenland and Canada. Institute of Religious Iconography. Iconography of religions. Leiden, The Netherland): State University Groningen, via E.J. Brill. section VIII, fascicle 2. ISBN 90-04-07160-1.

- Gabus, Jean (1970). A karibu eszkimók (in Hungarian). Budapest: Gondolat Kiadó. Translation of the original: Gabus, Jean (1944). Vie et coutumes des Esquimaux Caribous. Libraire Payot Lausanne.

External links[edit]

Wikiquote has quotations related to Soul.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Soul.

- Quantum Theory Won’t Save The Soul

- What Science Really Says About the Soul by Stephen Cave

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Ancient Theories of the Soul

- The soul in Judaism at Chabad.org

- The Old Testament Concept of the Soul by Heinrich J. Vogel]

- Body, Soul and Spirit Article in the Journal of Biblical Accuracy

- Is Another Human Living Inside You?

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). «Soul» . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- «The Soul», BBC Radio 4 discussion with Richard Sorabji, Ruth Padel and Martin Palmer (In Our Time, 6 June 2002)

Table of Contents

- What is the origin of the word soul?

- What does the word soul mean in Hebrew?

- Is the spirit and soul the same?

- What is opposite of Soul?

- What word means beautiful inside and out?

- Is Gorgeous better than beautiful?

- What’s another word for ravishing?

- What does it mean to ravage a woman?

- What is a ravenous person?

- What is monotonous work?

The Modern English word soul, derived from Old English sáwol, sáwel which means immortal principle in man, was first attested in the 8th century poem Beowulf v. 2820 and in the Vespasian Psalter 77.

What does the word soul mean in Hebrew?

nephesh

Is the spirit and soul the same?

While the two words are often used interchangeably, the primary distinction between soul and spirit in man is that the soul is the animate life, or the seat of the senses, desires, affections, and appetites. The spirit is that part of us that connects, or refuses to connect, to God.

What is opposite of Soul?

soul. Antonyms: soullessness, irrationality, unintellectuality, deadness, unfeelingness, spiritlessness, coldness, mind-issues, nonentity, nullity. Synonyms: spirit, vital principle, life, reason, intellect, vitality, fire, leader, inspirer, energy, courage, fervor, affection, feeling, being, person, man.

What word means beautiful inside and out?

alluring, appealing, attractive, charming, comely, delightful, drop-dead (slang) exquisite, fair, fine, glamorous, good-looking, gorgeous, graceful, handsome, lovely, pleasing, radiant, ravishing, stunning (informal) Antonyms. awful, bad, hideous, repulsive, terrible, ugly, unattractive, unpleasant, unsightly.

Is Gorgeous better than beautiful?

Beautiful is an adjective used to describe someone or something that is aesthetically pleasing. That person or item can please the mind, senses, and the eyes too. Gorgeous, on the other hand, refers to something or someone who is strikingly stunning, magnificent, good-looking, or wonderful from the outside.

What’s another word for ravishing?

Ravishing Synonyms – WordHippo Thesaurus….What is another word for ravishing?

| beautiful | lovely |

|---|---|

| attractive | striking |

| bewitching | captivating |

| charming | enticing |

| gorgeous | knockout |

What does it mean to ravage a woman?

To ravage is to pillage, sack, or devastate. The only time “ravaging” is properly used is in phrases like “when the pirates had finished ravaging the town, they turned to ravishing the women.” Which brings us to “ravish”: meaning to rape, or rob violently. … If a woman smashes your apartment up, she ravages it.

What is a ravenous person?

Ravenous, ravening, voracious suggest a greediness for food and usually intense hunger. Ravenous implies extreme hunger, or a famished condition: ravenous wild beasts. … Voracious implies craving or eating a great deal of food: a voracious child; a voracious appetite.

What is monotonous work?

Something that is monotonous is very boring because it has a regular, repeated pattern which never changes. It’s monotonous work, like most factory jobs. The food may get a bit monotonous, but there’ll be enough of it. Synonyms: tedious, boring, dull, repetitive More Synonyms of monotonous.

A depiction of an angel and a demon fighting for a man’s soul as God watches above.

In many religious and philosophical systems, the word «soul» denotes the inner essence of a being comprising its locus of sapience (self-awareness) and metaphysical identity. Souls are usually described as immortal (surviving death in an afterlife) and incorporeal (without bodily form); however, some consider souls to have a material component, and have even tried to establish the mass (or weight) of the soul. Additionally, while souls are often described as immortal they are not necessarily eternal or indestructible, as is commonly assumed.[1]

Throughout history, the belief in the existence of a soul has been a common feature in most of the world’s religions and cultures,[2] although some major religions (notably Buddhism) reject the notion of an eternal soul.[3] Those not belonging to an organized religion still often believe in the existence of souls although some cultures posit more than one soul in each person (see below). The metaphysical concept of a soul is often linked with ideas such as reincarnation, heaven, and hell.

The word «soul» can also refer to a type of modern music (see Soul Music).

Etymology

The modern English word soul derives from the Old English sáwol, sáwel, which itself comes from the Old High German sêula, sêla. The Germanic word is a translation of the Greek psychē (ψυχή- «life, spirit, consciousness») by missionaries such as Ulfila, apostle to the Goths (fourth century C.E.).

Definition

There is no universal agreement on the nature, origin, or purpose of the soul although there is much consensus that life, as we know it, does involve some deeper animating force inherent in all living beings (or at least in humans). In fact, the concept of an intrinsic life-force in all organisms has been a pervasive cross-cultural human belief.[4] Many preliterate cultures embraced notions of animism and shamanism postulating early ideas of the soul. Over time, philosophical reflection on the nature of the soul/spirit, and their relationship to the material world became more refined and sophisticated. In particular, the ancient Greeks and Hindu philosophers, for example, eventually distinguished different aspects of the soul, or alternatively, asserted the non-dualism of the cosmic soul.

Greek philosophers used many words for soul such as thymos, ker/kardie, phren/phrenes, menos, noos, and psyche.[5] Eventually, the Greeks differentiated between soul and spirit (psychē and pneuma respectively) and suggested that «aliveness» and the soul were conceptually linked.