- Top Definitions

- Quiz

- Related Content

- Examples

- British

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

[ voh-kab-yuh-ler-ee ]

/ voʊˈkæb yəˌlɛr i /

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

noun, plural vo·cab·u·lar·ies.

the stock of words used by or known to a particular people or group of persons: His French vocabulary is rather limited. The scientific vocabulary is constantly growing.

a list or collection of the words or phrases of a language, technical field, etc., usually arranged in alphabetical order and defined: Study the vocabulary in the fourth chapter.

the words of a language.

any collection of signs or symbols constituting a means or system of nonverbal communication: vocabulary of a computer.

any more or less specific group of forms characteristic of an artist, a style of art, architecture, or the like.

QUIZ

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE COMMON GRAMMAR DEBATES?

There are grammar debates that never die; and the ones highlighted in the questions in this quiz are sure to rile everyone up once again. Do you know how to answer the questions that cause some of the greatest grammar debates?

Which sentence is correct?

Origin of vocabulary

1525–35; <Medieval Latin vocābulārium, noun use of neuter of vocābulārius of words, equivalent to Latin vocābul(um) vocable + -ārius-ary

OTHER WORDS FROM vocabulary

vo·cab·u·lar·ied, adjective

Words nearby vocabulary

VOA, vo-ag, voc., vocab., vocable, vocabulary, vocabulary entry, vocal, vocal cords, vocal folds, vocal fry

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

Words related to vocabulary

dictionary, glossary, jargon, terminology, cant, lexicon, palaver, phraseology, thesaurus, wordbook, words, word-hoard, word stock

How to use vocabulary in a sentence

-

They have oddly expansive vocabularies and eminently quotable catchphrases, one of which — “Be Excellent to Each Other” — was posted on the marquee on my local movie theater when the pandemic shut it down in March.

-

Instead, the teen wrote tens of thousands of articles in English with a put-on Scottish accent, ignoring actual Scots grammar and vocabulary.

-

You speak in the voice and register that belongs to your old self—well-enunciated, resonant, its statements infiltrated by a formal, lawyerly vocabulary.

-

You know, so much of learning vocabulary is just word-definition, word-definition, word-definition.

-

The slightly modified version of Gödel’s scheme presented by Ernest Nagel and James Newman in their 1958 book, Gödel’s Proof, begins with 12 elementary symbols that serve as the vocabulary for expressing a set of basic axioms.

-

My Arabic is limited to a vocabulary of my favorite foods, such as “I love chicken and rice.”

-

In an uncanny way, that describes the precise definition of the hipster, when the term first appeared in the American vocabulary.

-

Here, the vocabulary of fast food for many young Brazilians is temaki (hand rolls) instead of burgers and fries.

-

Without the freedom to act on moral values, there is not even a vocabulary for public virtue.

-

Off camera, Rooney was growing up fast, ditching school and developing an impressive vocabulary of curse words.

-

I hope you are able to bear the brunt of the battle, for my vocabulary will scarcely carry me through ten words.

-

This word, as well as the one last-named, is very expressive in the vocabulary of the vulgar.

-

The strength, the originality, the true raison d’être of the Provençal speech resides in its rich vocabulary.

-

We remark elsewhere the lack of independence in the dialect of Avignon, that its vocabulary alone gives it life.

-

But in Scotland you will hear the people using numbers of modern French words, which are no part of the English vocabulary.

British Dictionary definitions for vocabulary

noun plural -laries

a listing, either selective or exhaustive, containing the words and phrases of a language, with meanings or translations into another language; glossary

the aggregate of words in the use or comprehension of a specified person, class, profession, etc

all the words contained in a language

a range or system of symbols, qualities, or techniques constituting a means of communication or expression, as any of the arts or craftsa wide vocabulary of textures and colours

Word Origin for vocabulary

C16: from Medieval Latin vocābulārium, from vocābulārius concerning words, from Latin vocābulum vocable

Collins English Dictionary — Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition

© William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins

Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

«Vocab» redirects here. For the song by Fugees, see Vocab (song).

A vocabulary is a set of familiar words within a person’s language. A vocabulary, usually developed with age, serves as a useful and fundamental tool for communication and acquiring knowledge. Acquiring an extensive vocabulary is one of the largest challenges in learning a second language.

Definition and usage[edit]

Vocabulary is commonly defined as «all the words known and used by a particular person».[1]

Productive and receptive knowledge[edit]

The first major change distinction that must be made when evaluating word knowledge is whether the knowledge is productive (also called achieve or active) or receptive (also called receive or passive); even within those opposing categories, there is often no clear distinction. Words that are generally understood when heard or read or seen constitute a person’s receptive vocabulary. These words may range from well known to barely known (see degree of knowledge below). A person’s receptive vocabulary is usually the larger of the two. For example, although a young child may not yet be able to speak, write, or sign, they may be able to follow simple commands and appear to understand a good portion of the language to which they are exposed. In this case, the child’s receptive vocabulary is likely tens, if not hundreds of words, but their active vocabulary is zero. When that child learns to speak or sign, however, the child’s active vocabulary begins to increase. It is also possible for the productive vocabulary to be larger than the receptive vocabulary, for example in a second-language learner who has learned words through study rather than exposure, and can produce them, but has difficulty recognizing them in conversation.

Productive vocabulary, therefore, generally refers to words that can be produced within an appropriate context and match the intended meaning of the speaker or signer. As with receptive vocabulary, however, there are many degrees at which a particular word may be considered part of an active vocabulary. Knowing how to pronounce, sign, or write a word does not necessarily mean that the word that has been used correctly or accurately reflects the intended message; but it does reflect a minimal amount of productive knowledge.

Degree of knowledge[edit]

Within the receptive–productive distinction lies a range of abilities that are often referred to as degree of knowledge. This simply indicates that a word gradually enters a person’s vocabulary over a period of time as more aspects of word knowledge are learnt. Roughly, these stages could be described as:

- Never encountered the word.

- Heard the word, but cannot define it.

- Recognizes the word due to context or tone of voice.

- Able to use the word and understand the general and/or intended meaning, but cannot clearly explain it.

- Fluent with the word – its use and definition.

Depth of knowledge[edit]

The differing degrees of word knowledge imply a greater depth of knowledge, but the process is more complex than that. There are many facets to knowing a word, some of which are not hierarchical so their acquisition does not necessarily follow a linear progression suggested by degree of knowledge. Several frameworks of word knowledge have been proposed to better operationalise this concept. One such framework includes nine facets:

- orthography – written form

- phonology – spoken form

- reference – meaning

- semantics – concept and reference

- register – appropriacy of use or register

- collocation – lexical neighbours

- word associations

- syntax – grammatical function

- morphology – word parts

Definition of word[edit]

Words can be defined in various ways, and estimates of vocabulary size differ depending on the definition used. The most common definition is that of a lemma (the inflected or dictionary form; this includes walk, but not walks, walked or walking). Most of the time lemmas do not include proper nouns (names of people, places, companies, etc.). Another definition often used in research of vocabulary size is that of word family. These are all the words that can be derived from a ground word (e.g., the words effortless, effortlessly, effortful, effortfully are all part of the word family effort). Estimates of vocabulary size range from as high as 200 thousand to as low as 10 thousand, depending on the definition used.[2]

Types of vocabulary[edit]

Listed in order of most ample to most limited:[3][4]

Reading vocabulary[edit]

A person’s reading vocabulary is all the words recognized when reading. This class of vocabulary is generally the most ample, as new words are more commonly encountered when reading than when listening.

Listening vocabulary[edit]

A person’s listening vocabulary comprises the words recognized when listening to speech. Cues such as the speaker’s tone and gestures, the topic of discussion, and the conversation’s social context may convey the meaning of an unfamiliar word.

Speaking vocabulary[edit]

A person’s speaking vocabulary comprises the words used in speech and is generally a subset of the listening vocabulary. Due to the spontaneous nature of speech, words are often misused slightly and unintentionally, but facial expressions and tone of voice can compensate for this misuse.

Writing vocabulary[edit]

The written word appears in registers as different as formal essays and social media feeds. While many written words rarely appear in speech, a person’s written vocabulary is generally limited by preference and context: a writer may prefer one synonym over another, and they will be unlikely to use technical vocabulary relating to a subject in which they have no interest or knowledge.

Final vocabulary[edit]

The American philosopher Richard Rorty characterized a person’s «final vocabulary» as follows:

All human beings carry about a set of words which they employ to justify their actions, their beliefs, and their lives. These are the words in which we formulate praise of our friends and contempt for our enemies, our long-term projects, our deepest self-doubts and our highest hopes… I shall call these words a person’s «final vocabulary». Those words are as far as he can go with language; beyond them is only helpless passivity or a resort to force. (Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity p. 73)[5]

Focal vocabulary[edit]

Focal vocabulary is a specialized set of terms and distinctions that is particularly important to a certain group: those with a particular focus of experience or activity. A lexicon, or vocabulary, is a language’s dictionary: its set of names for things, events, and ideas. Some linguists believe that lexicon influences people’s perception of things, the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis. For example, the Nuer of Sudan have an elaborate vocabulary to describe cattle. The Nuer have dozens of names for cattle because of the cattle’s particular histories, economies, and environments[clarification needed]. This kind of comparison has elicited some linguistic controversy, as with the number of «Eskimo words for snow». English speakers with relevant specialised knowledge can also display elaborate and precise vocabularies for snow and cattle when the need arises.[6][7]

Vocabulary growth[edit]

During its infancy, a child instinctively builds a vocabulary. Infants imitate words that they hear and then associate those words with objects and actions. This is the listening vocabulary. The speaking vocabulary follows, as a child’s thoughts become more reliant on their ability to self-express without relying on gestures or babbling. Once the reading and writing vocabularies start to develop, through questions and education, the child starts to discover the anomalies and irregularities of language.

In first grade, a child who can read learns about twice as many words as one who cannot. Generally, this gap does not narrow later. This results in a wide range of vocabulary by age five or six, when an English-speaking child will have learned about 1500 words.[8]

Vocabulary grows throughout one’s life. Between the ages of 20 and 60, people learn about 6,000 more lemmas, or one every other day.[9] An average 20-year-old knows 42,000 lemmas coming from 11,100 word families.[9] People expand their vocabularies by e.g. reading, playing word games, and participating in vocabulary-related programs. Exposure to traditional print media teaches correct spelling and vocabulary, while exposure to text messaging leads to more relaxed word acceptability constraints.[10]

Importance[edit]

- An extensive vocabulary aids expression and communication.

- Vocabulary size has been directly linked to reading comprehension.[11]

- Linguistic vocabulary is synonymous with thinking vocabulary.[11]

- A person may be judged by others based on their vocabulary.

- Wilkins (1972) said, «Without grammar, very little can be conveyed; without vocabulary, nothing can be conveyed.»[12]

Vocabulary size[edit]

Native-language vocabulary[edit]

Estimating average vocabulary size poses various difficulties and limitations due to the different definitions and methods employed such as what is the word, what is to know a word, what sample dictionaries were used, how tests were conducted, and so on.[9][13][14][15] Native speakers’ vocabularies also vary widely within a language, and are dependent on the level of the speaker’s education.

As a result, estimates vary from 10,000-17,000 word families[13][16] or 17,000-42,000 dictionary words for young adult native speakers of English.[9][14]

A 2016 study shows that 20-year-old English native speakers recognize on average 42,000 lemmas, ranging from 27,100 for the lowest 5% of the population to 51,700 lemmas for the highest 5%. These lemmas come from 6,100 word families in the lowest 5% of the population and 14,900 word families in the highest 5%. 60-year-olds know on average 6,000 lemmas more.

[9]

According to another, earlier 1995 study junior-high students would be able to recognize the meanings of about 10,000–12,000 words, whereas for college students this number grows up to about 12,000–17,000 and for elderly adults up to about 17,000 or more.[17]

For native speakers of German, average absolute vocabulary sizes range from 5,900 lemmas in first grade to 73,000 for adults.[18]

Foreign-language vocabulary[edit]

The effects of vocabulary size on language comprehension[edit]

The knowledge of the 3000 most frequent English word families or the 5000 most frequent words provides 95% vocabulary coverage of spoken discourse.[19]

For minimal reading comprehension a threshold of 3,000 word families (5,000 lexical items) was suggested[20][21] and for reading for pleasure 5,000 word families (8,000 lexical items) are required.[22] An «optimal» threshold of 8,000 word families yields the coverage of 98% (including proper nouns).[21]

Second language vocabulary acquisition[edit]

Learning vocabulary is one of the first steps in learning a second language, but a learner never finishes vocabulary acquisition. Whether in one’s native language or a second language, the acquisition of new vocabulary is an ongoing process. There are many techniques that help one acquire new vocabulary.

Memorization[edit]

Although memorization can be seen as tedious or boring, associating one word in the native language with the corresponding word in the second language until memorized is considered one of the best methods of vocabulary acquisition. By the time students reach adulthood, they generally have gathered a number of personalized memorization methods. Although many argue that memorization does not typically require the complex cognitive processing that increases retention (Sagarra and Alba, 2006),[23] it does typically require a large amount of repetition, and spaced repetition with flashcards is an established method for memorization, particularly used for vocabulary acquisition in computer-assisted language learning. Other methods typically require more time and longer to recall.

Some words cannot be easily linked through association or other methods. When a word in the second language is phonologically or visually similar to a word in the native language, one often assumes they also share similar meanings. Though this is frequently the case, it is not always true. When faced with a false friend, memorization and repetition are the keys to mastery. If a second language learner relies solely on word associations to learn new vocabulary, that person will have a very difficult time mastering false friends. When large amounts of vocabulary must be acquired in a limited amount of time, when the learner needs to recall information quickly, when words represent abstract concepts or are difficult to picture in a mental image, or when discriminating between false friends, rote memorization is the method to use. A neural network model of novel word learning across orthographies, accounting for L1-specific memorization abilities of L2-learners has recently been introduced (Hadzibeganovic and Cannas, 2009).[24]

The keyword method[edit]

One way of learning vocabulary is to use mnemonic devices or to create associations between words, this is known as the «keyword method» (Sagarra and Alba, 2006).[23] It also takes a long time to implement — and takes a long time to recollect — but because it makes a few new strange ideas connect it may help in learning.[23] Also it presumably does not conflict with Paivio’s dual coding system[25] because it uses visual and verbal mental faculties. However, this is still best used for words that represent concrete things, as abstract concepts are more difficult to remember.[23]

Word lists[edit]

Several word lists have been developed to provide people with a limited vocabulary for rapid language proficiency or for effective communication. These include Basic English (850 words), Special English (1,500 words), General Service List (2,000 words), and Academic Word List. Some learner’s dictionaries have developed defining vocabularies which contain only most common and basic words. As a result, word definitions in such dictionaries can be understood even by learners with a limited vocabulary.[26][27][28] Some publishers produce dictionaries based on word frequency[29] or thematic groups.[30][31][32]

The Swadesh list was made for investigation in linguistics.

See also[edit]

- Differences between American and British English (vocabulary)

- Language proficiency: The ability of an individual to speak or perform in an acquired language

- Lexicon

- Longest word in English: Many of the longest words in the English language

- Mental lexicon

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Cambridge Advanced Learners Dictionary

- ^ Brysbaert M, Stevens M, Mandera P and Keuleers E (2016) How Many Words Do We Know? Practical Estimates of Vocabulary Size Dependent on Word Definition, the Degree of Language Input and the Participant’s Age. Front. Psychol. 7:1116. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01116 [1]

- ^ Barnhart, Clarence L. (1968).

- ^ The World Book Dictionary. Clarence L. Barnhart. 1968 Edition. Published by Thorndike-Barnhart, Chicago, Illinois.

- ^ «Final vocabulary». OpenLearn. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Miller (1989)

- ^ Lenkeit

- ^ «Vocabulary». Sebastian Wren, Ph.D. BalancedReading.com http://www.balancedreading.com/vocabulary.html

- ^ a b c d e Brysbaert, Marc; Stevens, Michaël; Mandera, Paweł; Keuleers, Emmanuel (29 July 2016). «How Many Words Do We Know? Practical Estimates of Vocabulary Size Dependent on Word Definition, the Degree of Language Input and the Participant’s Age». Frontiers in Psychology. 7: 1116. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01116. PMC 4965448. PMID 27524974.

- ^ Joan H. Lee (2011). What does txting do 2 language: The influences of exposure to messaging and print media on acceptability constraints (PDF) (Master’s thesis). University of Calgary. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- «Texting affects ability to interpret words». University of Calgary. 17 February 2012. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012.

- ^ a b Stahl, Steven A. Vocabulary Development. Cambridge: Brookline Books, 1999. p. 3. «The Cognitive Foundations of Learning to Read: A Framework», Southwest Educational Development Laboratory, [2], p. 14.

- ^ Wilkins, David A. (1972). Linguistics in Language Teaching. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 111.

- ^ a b Goulden, Robin; Nation, Paul; Read, John (1 December 1990). «How Large Can a Receptive Vocabulary Be?» (PDF). Applied Linguistics. 11 (4): 341–363. doi:10.1093/applin/11.4.341.

- ^ a b D’Anna, Catherine; Zechmeister, Eugene; Hall, James (1 March 1991). «Toward a meaningful definition of vocabulary size». Journal of Literacy Research. 23 (1): 109–122. doi:10.1080/10862969109547729. S2CID 122864817.

- ^ Nation, I. S. P. (1993). «Using dictionaries to estimate vocabulary size: essential, but rarely followed, procedures» (PDF). Language Testing. 10 (1): 27–40. doi:10.1177/026553229301000102. S2CID 145331394.

- ^ Milton, James; Treffers-Daller, Jeanine (29 January 2013). «Vocabulary size revisited: the link between vocabulary size and academic achievement». Applied Linguistics Review. 4 (1): 151–172. doi:10.1515/applirev-2013-0007. S2CID 59930869.

- ^ Zechmeister, Eugene; Chronis, Andrea; Cull, William; D’Anna, Catherine; Healy, Noreen (1 June 1995). «Growth of a functionally important lexicon». Journal of Literacy Research. 27 (2): 201–212. doi:10.1080/10862969509547878. S2CID 145149827.

- ^

- ^ Adolphs, Svenja; Schmitt, Norbert (2003). «Lexical Coverage of Spoken Discourse» (PDF). Applied Linguistics. 24 (4): 425–438. doi:10.1093/applin/24.4.425.

- ^ Laufer, Batia (1992). «How Much Lexis is Necessary for Reading Comprehension?». In Bejoint, H.; Arnaud, P. (eds.). Vocabulary and Applied Linguistics. Macmillan. pp. 126–132.

- ^ a b Laufer, Batia; Ravenhorst-Kalovski, Geke C. (April 2010). «Lexical threshold revisited: Lexical text coverage, learners’ vocabulary size and reading comprehension» (PDF). Reading in a Foreign Language. 22 (1): 15–30.

- ^ Hirsh, D.; Nation, I.S.P. (1992). «What vocabulary size is needed to read unsimplified texts for pleasure?» (PDF). Reading in a Foreign Language. 8 (2): 689–696.

- ^ a b c d Sagarra, Nuria and Alba, Matthew. (2006). «The Key Is in the Keyword: L2 Vocabulary Learning Methods With Beginning Learners of Spanish». The Modern Language Journal, 90, ii. pp. 228–243.

- ^ Hadzibeganovic, Tarik; Cannas, Sergio A (2009). «A Tsallis’ statistics-based neural network model for novel word learning». Physica A. 388 (5): 732–746. Bibcode:2009PhyA..388..732H. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2008.10.042.

- ^ Paivio, A. (1986). Mental Representations: A Dual Coding Approach. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Bogaards, Paul (July 2010). «The evolution of learners’ dictionaries and Merriam-Webster’s Advanced Learner’s English Dictionary» (PDF). Kernerman Dictionary News (18): 6–15.

- ^ «The Oxford 3000». Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries.

- ^ «Clear Definitions». Macmillan Dictionary.

- ^ Routledge Frequency Dictionaries

- ^ (in German) Langenscheidt Grundwortschatz

- ^ (in German) Langenscheidt Grund- und Aufbauwortschatz

- ^ (in German) Hueber Grundwortschatz

References[edit]

- Barnhart, Clarence Lewis (ed.) (1968). The World Book Dictionary. Chicago: Thorndike-Barnhart, OCLC 437494

- Brysbaert M, Stevens M, Mandera P and Keuleers E (2016) How Many Words Do We Know? Practical Estimates of Vocabulary Size Dependent on Word Definition, the Degree of Language Input and the Participant’s Age. Front. Psychol. 7:1116. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01116.

- Flynn, James Robert (2008). Where have all the liberals gone? : race, class, and ideals in America. Cambridge University Press; 1st edition. ISBN 978-0-521-49431-1 OCLC 231580885

- Lenkeit, Roberta Edwards (2007) Introducing cultural anthropology Boston: McGraw-Hill (3rd. ed.) OCLC 64230435

- Liu, Na; Nation, I. S. P. (1985). «Factors affecting guessing vocabulary in context» (PDF). RELC Journal. 16: 33–42. doi:10.1177/003368828501600103. S2CID 145695274.

- Miller, Barbara D. (1999). Cultural Anthropology(4th ed.) Boston: Allyn and Bacon, p. 315 OCLC 39101950

- Schonell, Sir Fred Joyce, Ivor G. Meddleton and B. A. Shaw, A study of the oral vocabulary of adults : an investigation into the spoken vocabulary of the Australian worker, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1956. OCLC 606593777

- West, Michael (1953). A general service list of English words, with semantic frequencies and a supplementary word-list for the writing of popular science and technology London, New York: Longman, Green OCLC 318957

External links[edit]

Look up vocabulary in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Bibliography on vocabulary I.S.P. Nation’s extensive collection of research on vocabulary.

- Vocabulary Acquisition Research Group Archive An bibliographic database on vocabulary acquisition at Swansea University.

Vocabulary (from the Latin for «name,» also called wordstock, lexicon, and lexis) refers to all the words in a language that are understood by a particular person or group of people. There are two main types of vocabulary: active and passive. An active vocabulary consists of the words we understand and use in everyday speaking and writing. Passive vocabulary is made up of words that we may recognize but don’t generally use in the course of normal communication.

Vocabulary Acquisition

«By age 2, spoken vocabulary usually exceeds 200 words. Three-year-olds have an active vocabulary of at least 2,000 words, and some have far more. By 5, the figure is well over 4,000. The suggestion is that they are learning, on average, three or four new words a day.»—From «How Language Works» by David Crystal

Measuring Vocabulary

Exactly how many words are there in the English language? There’s no real answer to that question. In order to reach a plausible total, there must be a consensus as to what constitutes actual vocabulary.

Editors of the 1989 edition of the Oxford English Dictionary reported that the reference work contained upwards of 500,000 definitions. The average dictionary clocks it at about 100,000 entries. When you add it all up along with lists of geographical, zoological, botanical, and other specialized jargon, an imperfect but credible total for the number of words and word-like forms in present-day English is in excess of a billion words.

Likewise, the sum of a person’s vocabulary is more than just the total number of words he or she knows. It also takes into account what people have experienced, reflected on, and either incorporated or rejected. As a result, the measure of vocabulary is fluid rather than fixed.

The English Language’s Appropriated Vocabulary

«English, probably more so than any language on earth, has a stunningly bastard vocabulary,» notes David Wolman, a frequent writer on language, Contributing editor at Outside, and longtime contributor at Wired. He estimates that between 80 and 90% of all the words in the Oxford English Dictionary are derived from other languages. «Old English, lest we forget,» he points out, «was already an amalgam of Germanic tongues, Celtic, and Latin, with pinches of Scandinavian and Old French influence as well.»

According to Ammon Shea, the author of several books on obscure words, «the vocabulary of English is currently 70 to 80% composed of words of Greek and Latin origin, but it is certainly not a Romance language, it is a Germanic one.» Proof for this, he explains can be found in the fact that while it’s relatively simple to construct a sentence without using words of Latin origin, «it’s pretty much impossible to make one that has no words from Old English.»

English Vocabulary by Region

- Canadian English Vocabulary: Canadian English vocabulary tends to be closer to American English than British. The languages of both American and British settlers remained intact for the most part when settlers came to Canada. Some language variations have resulted from contact with Canada’s Aboriginal languages and with French settlers. While there are relatively few Canadian words for things that have other names in other dialects, there is enough differentiation to qualify Canadian English as a unique, identifiable dialect of North American English at the lexical level.

- British English and American English: These days, there are many more American words and expressions in British English than ever before. Although there is a two-way exchange, the directional flow of borrowing favors the route from American to Britain. As a result, speakers of British English generally tend to be familiar with more Americanisms than speakers of American English are of Britishisms.

- Australian English: «Australian English is set apart from other dialects thanks to its abundance of highly colloquial words and expressions. Regional colloquialisms in Australia often take the form of shortening a word, and then adding a suffix such as -ie or -o. For example, a «truckie» is a truck driver; a «milko» is a milkman; «Oz» is short for Australia, and an «Aussie» is an Australian.

The Lighter Side of Vocabulary

«I was with a girl once. Wasn’t a squaw, but she was purty. She had yellow hair, like, uh… oh, like something.»

«Like hair bobbed from a ray of sunlight?»

«Yeah, yeah. Like that. Boy, you talk good.»

«You can hide things in vocabulary.»

—Garret Dillahunt as Ed Miller and Paul Schneider as Dick Liddil in «The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford»

Related Resources

- Common Word Roots

- Introduction to Etymology

- Lexical Competence

- Lexicalization

- Lexicogrammar

- The 3 Best Sites to Learn a New Word Every Day

Vocabulary-Building Exercises and Quizzes

- Vocabulary Quiz #1: Defining Words in Context

- Vocabulary Quiz on the «I Have a Dream» Speech by Martin Luther King, Jr.

Sources

- Crystal, David. «How Language Works: How Babies Babble, Words Change Meaning, and Languages Live or Die.» Harry N. Abrams, 2006

- Wolman, David. «Righting the Mother Tongue: From Olde English to Email, the Tangled Story of English Spelling,» Smithsonian. October 7, 2008

- McWhorter, John. «The Power of Babel: A Natural History of Language.» Harper Perennial, 2001

- Samuels, S. Jay. «What Research Has to Say About Vocabulary Instruction.» International Reading Association, 2008

- McArthur, Tom. «The Oxford Companion to the English Language.» Oxford University Press, 1992

- Wolman, David. «Righting the Mother Tongue: From Olde English to Email, the Tangled Story of English Spelling.» Harper, 2010

- Shea, Ammon. «Bad English: A History of Linguistic Aggravation.» TarcherPerigee, 2014

- Boberg, Charles. «The English Language in Canada: Status, History and Comparative Analysis.» Cambridge University Press, 2010

- Kövecses, Zoltán. «American English: An Introduction.» Broadview Press, 2000

- Wells, John Christopher. «Accents of English: The British Isles.» Cambridge University Press, 1986

- McCarthy, Michel; O’Dell, Felicity. «English Vocabulary in Use: Upper-Intermediate,» Second Edition. Cambridge University Press, 2001

2. Etymology. Etymological structure of the English Vocabulary.

1.

Etymology

is a

branch of lexicology studying the origin of words. Etymologically, the

English vocabulary is divided into native and loan words, or borrowed words.

A native word is a word which belongs to the original English word stock and

is known from the earliest available manuscripts of the Old English period. A

borrowed word is a word taken over from another language and modified

according to the standards of the English language.

2.

3.

The

etymological linguistic analysis showed that the borrowed stock of words is

larger than the native stock of words. In fact native words comprise only 30%

of the total number of words in the English vocabulary. A native word is a

word which belongs to the original English stock, which belongs to

Anglo-Saxon origin.

4.

5.

Many

linguists consider foreign influence plays the most important role in the

history of the English language. But the grammar and phonetic system are very

stable (unchangeable) and are not often influenced by other languages.

Besides when we speak about the role of native and borrowed words in the

English language we must not take into consideration only the number of them

but their semantic, stylistic character, their word building ability,

frequency value, collocability (valency) and the productivity of their word

building patterns. If we approach the study of the role of native borrowed

words from this point of view we see, though the native words are not

numerous they play an important role in the English language. They have high

frequency value, great word-forming power, wide collocability, many meanings

and they are stylistically neutral.

6.

Almost

all words of native origin belong to very important semantic groups. They

include most of the auxiliary and model verbs: shall, will, should, must,

can, may; pronouns: I, he, my, your, his, who, whose; prepositions: in, out,

on, under, for, of; numerals: one two three, four, five, six, etc;

conjunctions: and, but, till, as etc; words denoting parts of body: head,

hand, arm, back, foot, eye etc; members of a family: father, mother, brother,

son, wife; natural phenomena and planets: snow, rain, wind, sun, moon,

animals: horse, cow, sheep, cat; common actions: do, make, go, come, hear,

see, eat, speak, talk etc. All these words are very frequent words, we use

them every day in our speech. Many words of native origin possess large

clusters of derived and compound words in the present-day language.

7.

Such

affixes of native origin as er, -ness, -ish, -ed, un, -mis, -dom, -hood, -ly,

-over, -out, -under, — are of native origin.

Этимология — это ветвь лексикологии,

изучающая происхождение слов. Этимологически, английский словарь разделен на

родные и заемные слова или заимствованные слова. Родное слово — это слово,

которое принадлежит оригинальному английскому языку и известно из самых

ранних доступных рукописей древнеанглийского периода. Заимствованное слово —

это слово, взятое с другого языка и измененное в соответствии со стандартами

английского языка.

Этимологический лингвистический анализ показал, что заимствованный

запас слов больше, чем собственный запас слов. Фактически, родные слова

составляют только 30% от общего числа слов в английской лексике. Родным

словом является слово, которое принадлежит оригинальному английскому запасу,

принадлежащему англо-саксонскому происхождению.

Многие лингвисты считают, что иностранное влияние играет самую важную

роль в истории английского языка. Но грамматика и фонетическая система очень

стабильны (неизменяемы), и на них часто не влияют другие языки. Кроме того,

когда мы говорим о роли родных и заимствованных слов в английском языке, мы

не должны принимать во внимание только их число, но их семантический,

стилистический характер, их способность к построению, частотность,

способность колликации (валентность) и производительность их. Шаблоны

словообразования. Если мы подходим к изучению роли коренных заимствованных

слов с этой точки зрения, мы видим, хотя родные слова не многочисленны, они

играют важную роль на английском языке. Они имеют высокую частотную ценность,

большую словообразующую силу, широкую совместимость, много значений, и они

стилистически нейтральны.

Почти все слова родного происхождения принадлежат к очень

важным семантическим группам. Они включают большинство вспомогательных и

модельных глаголов: они должны, должны, должны, должны, могут; Местоимения:

Я, он, мой, ваш, его, кто, чей; Предлоги: in, out, on, under, for, of; Цифры:

одна два три, четыре, пять, шесть и т. Д .; Союзы: и, но, до, как и т. Д .;

Слова, обозначающие части тела: голова, рука, рука, спина, стопа, глаз и т. Д

.; Члены семьи: отец, мать, брат, сын, жена; Природные явления и планеты:

снег, дождь, ветер, солнце, луна, животные: лошадь, корова, овца, кошка; Общие

действия: делать, делать, идти, приходить, слышать, видеть, есть, говорить,

говорить и т. Д. Все эти слова — очень частые слова, мы используем их каждый

день в нашей речи. Многие слова родного происхождения обладают большими

кластерами производных и сложных слов на современном языке.

Такие аффиксы родного происхождения, как er, -ness, -ish, -ed, un,

-mis, -dom, -hood, -ly, -over, -out, -under, — имеют коренное происхождение.

1.Etymological structure of the English vocabulary.

2 Native word-stems (man, pan).

3. Borrowings from latin (fanaticus — fan).

4. Scandinavian borrowings (sky) – 9th-10th century.

5. Borrowings from French (beggar, fiancé) -Norman Conquest, 11th

century.

6.Borrowings from other languages (European, Oriental — feng shui,

American Indians).

1.Этимологическая структура английской

лексики.

2 Родные словосочетания (человек, кастрюля).

3. Заимствования из латинского (fanaticus — fan).

4. Скандинавские заимствования (небо) — 9-10

в.

5. Заимствования с французского (нищий,

жених) во время завоевания Нормана, 11 век.

6.Заимствования с других языков (европейские,

восточные — фэн-шуй, американские индейцев)

1.

Words of native origin

The origin of English words.

The most characteristic feature of English is its mixed

character. While it is wrong to speak of the mixed character of the language

as a whole, the composite nature of the English vocabulary cannot be denied.

1.

Native

words — words of Anglo-Saxon origin brought to the British Isles from the

continent in the 5th century by the Germanic tribes — the Angles, the Saxons

and the Jutes.

2.

Native words are subdivided into two groups:

1) words of the Common Indo-European word stock

2) words of the Common Germanic origin

3.Words of the Indo-European stock have cognates (parallels) in

different Indo-European languages: Greek, Latin, French, Italian, Polish,

Russian and others: father (OE fder, Gothic fadar, Swedish fader,

German Vater, Greek patйr, Latin pбter, French pere, Persian pedжr, Sanscrit pitr)

4.Words

of the Common Germanic stock have cognates only in the Germanic group: in

German, Norwegian, Dutch, Icelandic, etc.: to sing (OE singan, Gothic

siggwan, German singen)

5. Numerically the Germanic group is larger. Thematically these

two groups do not differ very much. Words of both groups denote parts of the

human body, animals, plants, phenomena of nature, physical properties, basic

actions, etc. Terms of kinship, the most frequent verbs and the majority of

numerals belong to the Common Indo-European word stock. Many adverbs and

pronouns are of Germanic origin.

6.Native words constitute about 30 percent of the English

vocabulary, but they make up 80 percent of the 500 most frequent words.

Almost all native words belong to very important semantic groups. They

include most of the auxiliary and modal verbs (shall, will, should, would,

must, can, may), pronouns (I, you, he, my, your, his, who, whose),

prepositions (in, out, on, under), numerals (one, two, three, four, etc),

conjunctions (and, but, till, as), articles.

7.Besides high frequency value words of the native word stock

are characterised by the following features:

— simple structure (they are often monosyllabic)

— developed polysemy

— great word-building power

— an ability to enter a great number of phraseological units

— a wide range of lexical and grammatical valency

— stability

8.Notional words of Anglo-Saxon origin:

— parts of the body: head, hand, arm, back;

— members of the family and closest relatives: father, mother,

brother, son, wife;

— natural phenomena and planets: snow, rain, wind, frost, sun,

moon, star;

— animals: horse, cow, sheep, cat;

— qualities and properties: old, young, cold, hot, heavy, light,

dark, white, long;

— common actions: do, make, go, come, see, hear, eat.

Native words are highly polysemantic, stylistically neutral,

enter a number of phraseological units. We see that the role

of native words in the language is great. Many authors use native words more

than foreign ones. Thus Shakespeare used 90% native words and 10% foreign

words. Swift used 75% native words.

1. Слова родного происхождения

Происхождение английских слов.

Наиболее характерной чертой английского

является его смешанный характер. Хотя ошибочно говорить о смешанном характере

языка в целом, несоответствующий характер английского словаря нельзя

отрицать.

1. Родные слова — слова англосаксонского

происхождения, привезенные на Британские острова с континента в 5 веке

германскими племенами — англами, саксами и ютами.

2.Родные слова подразделяются на две группы:

1) слова общего индоевропейского словарного

запаса

2) слова общего германского происхождения

3.Слова индоевропейского фонда имеют родственные (параллели) в разных

индоевропейских языках: греческий, латинский, французский, итальянский,

польский, русский и другие: отец (СА f fder, готический

фадар, шведский фейдер, немецкий фатер, греческий Patrr,

латинский pbter, французский pere,

персидский педжр, Sanscrit pitr)

4.Слова общегерманского происхождения имеют

родственные отношения только в германской группе: на немецком, норвежском,

голландском, исландском и т. д .: петь (СА singan,

готический сиггван, немецкий singen)

5.Численно германская группа больше.

Тематически эти две группы не очень сильно отличаются. Слова обеих групп

обозначают части человеческого тела, животных, растений, явления природы,

физические свойства, основные действия и т. Д. Сроки родства, самые частые

глаголы и большинство цифр относятся к общему индоевропейскому слову. Многие

наречия и местоимения имеют германское происхождение.

6.Родные слова составляют около 30 процентов

английской лексики, но они составляют 80 процентов из 500 наиболее часто

встречающихся слов. Почти все родные слова принадлежат к очень важным

семантическим группам. Они включают в себя большинство вспомогательных и

модальных глаголов (должно, должно, должно, должно, должно быть, может),

местоимения (я, вы, он, мой, ваш, его, кто, чей), предлоги (в, На, внизу),

цифры (один, два, три, четыре и т. Д.), Союзы (и, но, до, как), артикли.

7.Помимо высокочастотных значений слова

исходного словарного запаса характеризуются следующими особенностями:

— простая структура (они часто односложные)

— развитая полисемия

— отличная сила слова

— способность вводить большое количество

фразеологических единиц

— широкий диапазон лексической и

грамматической валентности

— стабильность

8.Условные слова англосаксонского

происхождения:

— части тела: голова, рука, рука, спина;

— члены семьи и ближайшие родственники: отец,

мать, брат, сын, жена;

— природные явления и планеты: снег, дождь,

ветер, мороз, солнце, луна, звезда;

— животные: лошадь, корова, овца, кошка;

— качества и свойства: старые, молодые,

холодные, горячие, тяжелые, светлые, темные, белые, длинные;

— общие действия: делать, делать, идти,

приезжать, видеть, слышать, есть.

Родные слова очень многозначны,

стилистически нейтральны, входят в число фразеологических единиц. Мы видим, что роль родных слов в языке велика. Многие авторы

используют родные слова больше, чем иностранные. Таким образом, Shekespear

использовал 90% родных слов и 10% иностранных слов. Swift использовал 75%

родных слов.

Borrowings enter the language in two ways: though oral

speech (by immediate contact between the people) and though written speech

(by indirect contact though books). Words borrowed orally (inch, mill,

street, map) are usually short and they undergo more change in the act of

adopter. Written borrowings (communique, belles — letters naivete,

psychology, pagoda etc) are often rather long and they are unknown to many

people, speaking English

Заимствования входят в язык двумя способами:

через устную речь (непосредственным контактом между людьми) и через

письменную речь (косвенным контактом, через книги). Слова, заимствованные

устно (дюймы, мельница, улица, карта), обычно коротки, и они подвергаются

большему изменению в акте усыновителя. Письменные заимствования (коммуна,

стиль переписки беллас — письма , психология, пагода и т. Д.) Часто довольно

длинные, и они неизвестны многим людям, говорящим по-английски

Borrowed words have been called “the milestones of

philology” — said O. Jeperson — because they permit us (show us ) to fix approximately

the dates of linguistic changes. They show us the course of civilization and

give us information of the nations”.

Заимствованные слова были названы «вехами

филологии», — сказал О. Джеперсон, — потому что они позволяют нам (показать)

приблизить даты лингвистических изменений. Они показывают нам курс

цивилизации и дают нам информацию о народах ».

The well-known linguist Shuchard said “No language is entirely

pure”, that all the languages are mixed. Borrowed words enter the language as

a result of influence of two main causes or factors; linguistic and

extra-linguistic. Economic, cultural, industrial, political relations of speakers

of the language with other countries refer to extra-linguistic factors. The

historical development of England also influenced the language. Due to the

great influence of the Roman civilization Latin was for a long time used in

England as the language of learning and religion. Old Norse of the

Scandinavian tribes was the language of the conquerors (9th, 10th and 11th

centuries). French (Norman dialect) was the language of the other conquerors

who brought with them a lot new notions of a higher social system, developed

fuedalizm. It was the language of upper classes, of official documents and

school (11th-14th centuries). These factors are

extra-linguistic ones.

Известный лингвист Шухард сказал: «Нет языка

в чистоте», что все языки смешаны. Заимствованные слова входят в язык в

результате влияния двух основных причин или факторов; Лингвистической и

внеязыковой. Экономические, культурные, промышленные, политические отношения

носителей языка с другими странами относятся к экстралингвистическим

факторам. Историческое развитие Англии также повлияло на язык. Из-за большого

влияния римской цивилизации латынь долгое время использовалась в Англии как

язык обучения и религии. Древнескандинавские скандинавские племена были

языком завоевателей (9-10-11 столетий). Французский (норманнский диалект) был

языком других завоевателей, которые принесли с собой много новых

представлений о высшей социальной системе, развили фьюдализм. Это был язык

высших классов, официальных документов и школы (11-14 с). Эти факторы являются

экстралингвистическими.

The absence of equivalent words in the language to express

new subjects or phenomena makes people borrow words. Eg. football,

volleyball, midshipman in Russian; to economize the linguistic means, i.e. to

use a foreign word instead of long native expressions and others is called

linguistic cause.

The closer the two interacting languages are in structure

the easier it is for words of one language to penetrate into the other. The

fact that Scandinavian borrowings have penetrated into such grammatical

classes as prepositions and pronouns (they, them, their, both, same, till)

can only be attributed to a similarity in the structure of the two languages.

.

Отсутствие эквивалентных слов в языке для

выражения новых предметов или явлений заставляет людей заимствовать слова.

Ex. Слова футбол, волейбол, мичман на русском языке; Чтобы экономить

лингвистические средства, то есть использовать иностранное слово вместо

длинных родных выражений, а другие называются лингвистическими причинами.

Чем ближе эти два взаимодействующих языка

находятся в структуре, тем легче для слов одного языка проникать в другой.

Тот факт, что скандинавские заимствования проникли в такие грамматические

классы, как предлоги и местоимения (они, их, их, оба, то же, до), могут быть

отнесены только к сходству в структуре этих двух языков.

Слайд 1

Lecture 3. Etymological Characteristics of the English Vocabulary.

1.

The Origin of English Words.

2. Words of Native

Origin.

3. Borrowed Words.

4. Causes and

Ways of Borrowing.

5. Criteria of Borrowing

6. Assimilation of Borrowings.

7. Etymological Doublets.

8. Influence of Borrowings.

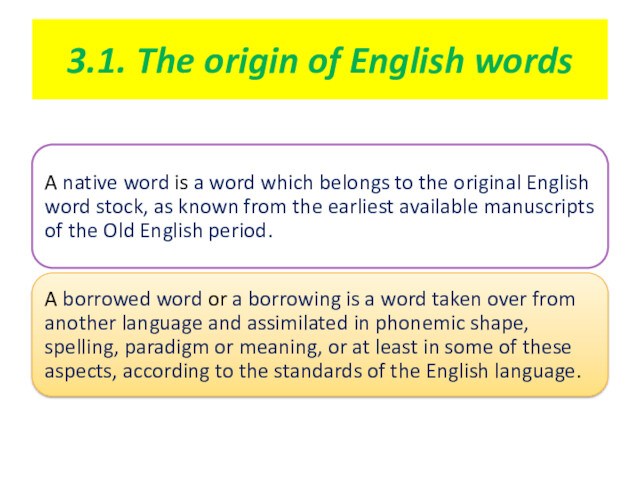

Слайд 2

3.1. The origin of English words

Слайд 3

Source of Borrowing and Origin of Word

Слайд 4

3.2. Words of native origin

Native words constitute up

to 30 % of the English vocabulary

They are

the most frequently used words as they constitute 80 %

of the 500 most frequent words compiled by Thorndyke and Longe (The Teachers’ Wordbook of 30,000 words. New York, 1959).

Слайд 5

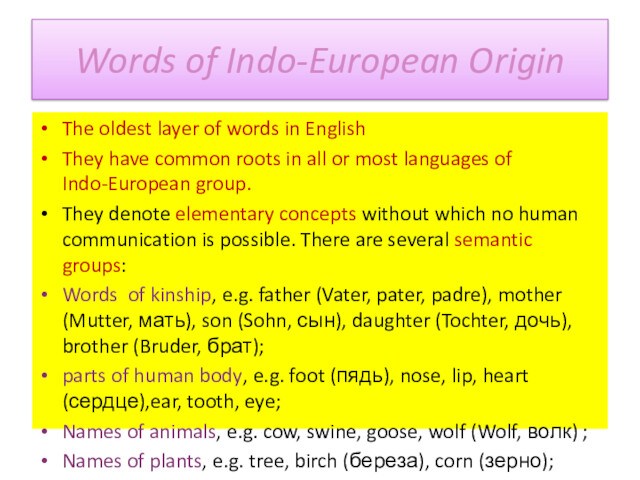

Words of Indo-European Origin

The oldest layer of words

in English

They have common roots in all or

most languages of Indo-European group.

They denote elementary concepts without

which no human communication is possible. There are several semantic groups:

Words of kinship, e.g. father (Vater, pater, padre), mother (Mutter, мать), son (Sohn, сын), daughter (Tochter, дочь), brother (Bruder, брат);

parts of human body, e.g. foot (пядь), nose, lip, heart (сердце),ear, tooth, eye;

Names of animals, e.g. cow, swine, goose, wolf (Wolf, волк) ;

Names of plants, e.g. tree, birch (береза), corn (зерно);

Слайд 6

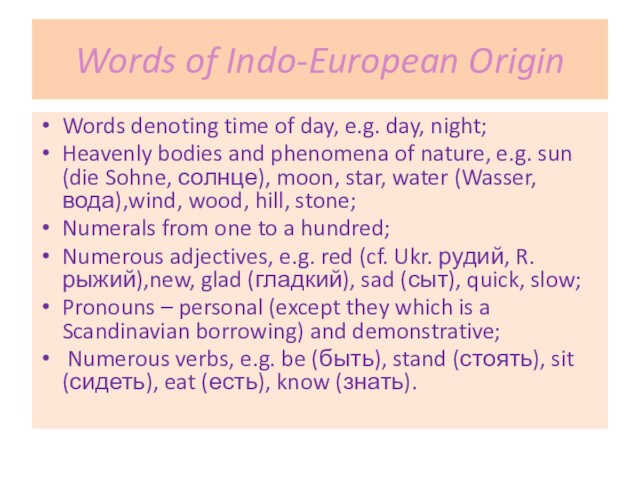

Words of Indo-European Origin

Words denoting time of day,

e.g. day, night;

Heavenly bodies and phenomena of nature, e.g.

sun (die Sohne, солнце), moon, star, water (Wasser, вода),wind, wood,

hill, stone;

Numerals from one to a hundred;

Numerous adjectives, e.g. red (cf. Ukr. рудий, R. рыжий),new, glad (гладкий), sad (сыт), quick, slow;

Pronouns – personal (except they which is a Scandinavian borrowing) and demonstrative;

Numerous verbs, e.g. be (быть), stand (стоять), sit (сидеть), eat (есть), know (знать).

Слайд 7

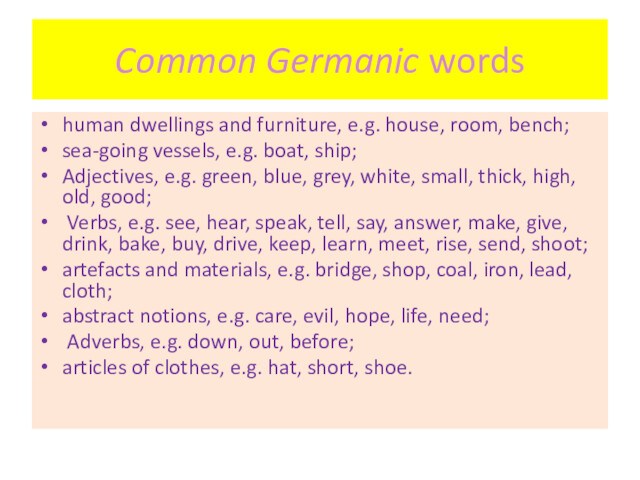

Common Germanic words

German, Norwegian, Dutch, Icelandic.

They represent

words of roots common to all or most Germanic

languages.

The main semantic groups are:

parts of human body, e.g.

head, hand, arm, finger, bone;

plants, e.g. oak, fir, grass;

animals, e.g. bear, fox, calf;

natural phenomena, e.g. rain, frost, storm, flood, ice;

periods of time and seasons of the year, e.g. time, week, winter, spring, summer;

landscape features, e.g. sea, land, ground, earth;

Слайд 8

Common Germanic words

human dwellings and furniture, e.g. house,

room, bench;

sea-going vessels, e.g. boat, ship;

Adjectives, e.g. green, blue,

grey, white, small, thick, high, old, good;

Verbs, e.g. see,

hear, speak, tell, say, answer, make, give, drink, bake, buy, drive, keep, learn, meet, rise, send, shoot;

artefacts and materials, e.g. bridge, shop, coal, iron, lead, cloth;

abstract notions, e.g. care, evil, hope, life, need;

Adverbs, e.g. down, out, before;

articles of clothes, e.g. hat, short, shoe.

Слайд 9

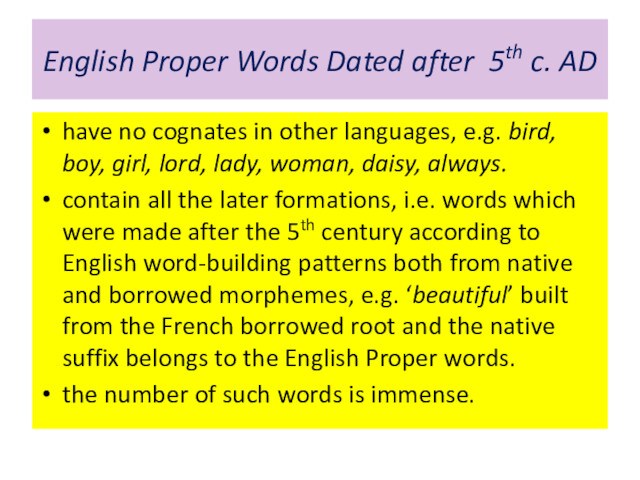

English Proper Words Dated after 5th c. AD

have

no cognates in other languages, e.g. bird, boy, girl,

lord, lady, woman, daisy, always.

contain all the later formations,

i.e. words which were made after the 5th century according to English word-building patterns both from native and borrowed morphemes, e.g. ‘beautiful’ built from the French borrowed root and the native suffix belongs to the English Proper words.

the number of such words is immense.

Слайд 10

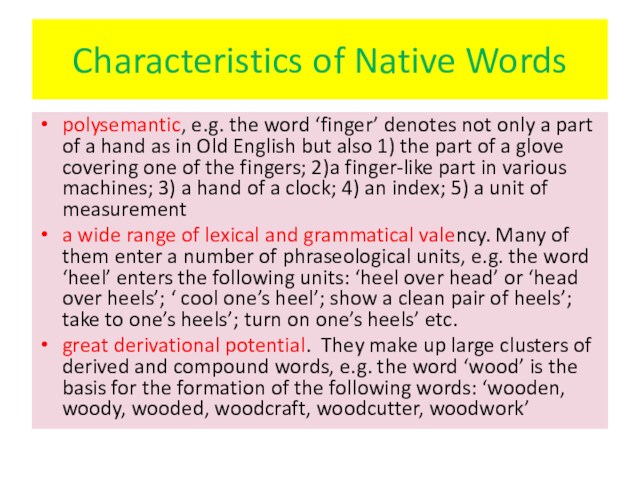

Characteristics of Native Words

polysemantic, e.g. the word ‘finger’

denotes not only a part of a hand as

in Old English but also 1) the part of a

glove covering one of the fingers; 2)a finger-like part in various machines; 3) a hand of a clock; 4) an index; 5) a unit of measurement

a wide range of lexical and grammatical valency. Many of them enter a number of phraseological units, e.g. the word ‘heel’ enters the following units: ‘heel over head’ or ‘head over heels’; ‘ cool one’s heel’; show a clean pair of heels’; take to one’s heels’; turn on one’s heels’ etc.

great derivational potential. They make up large clusters of derived and compound words, e.g. the word ‘wood’ is the basis for the formation of the following words: ‘wooden, woody, wooded, woodcraft, woodcutter, woodwork’

Слайд 11

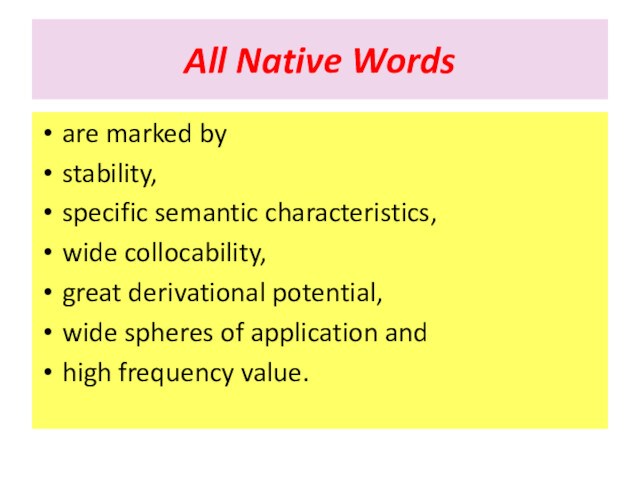

All Native Words

are marked by

stability,

specific semantic

characteristics,

wide collocability,

great derivational potential,

wide spheres of

application and

high frequency value.

Слайд 12

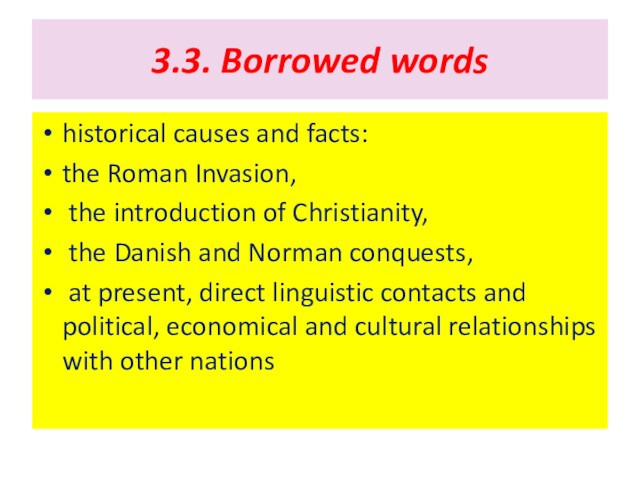

3.3. Borrowed words

historical causes and facts:

the Roman Invasion,

the introduction of Christianity,

the Danish and Norman conquests,

at present, direct linguistic contacts and political, economical and

cultural relationships with other nations

Слайд 13

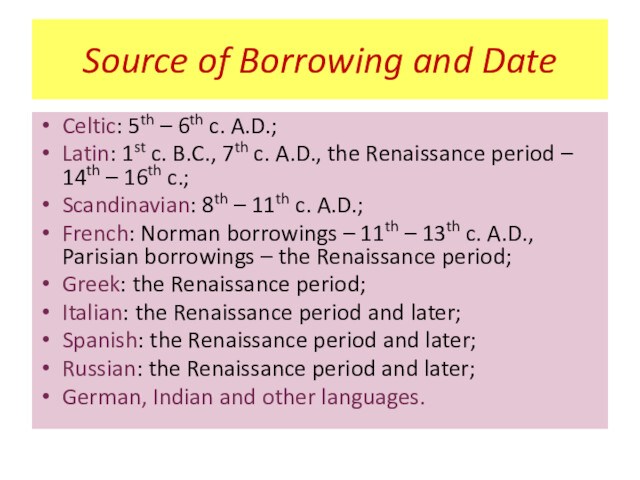

Source of Borrowing and Date

Celtic: 5th – 6th

c. A.D.;

Latin: 1st c. B.C., 7th c. A.D., the

Renaissance period – 14th – 16th c.;

Scandinavian: 8th – 11th

c. A.D.;

French: Norman borrowings – 11th – 13th c. A.D., Parisian borrowings – the Renaissance period;

Greek: the Renaissance period;

Italian: the Renaissance period and later;

Spanish: the Renaissance period and later;

Russian: the Renaissance period and later;

German, Indian and other languages.

Слайд 14

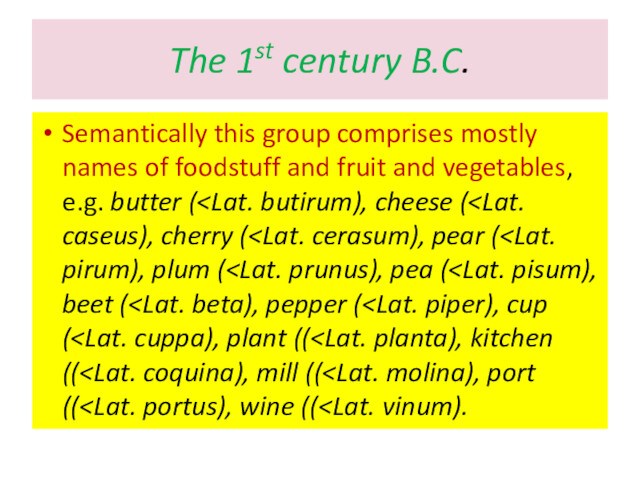

The 1st century B.C.

Semantically this group comprises mostly

names of foodstuff and fruit and vegetables, e.g. butter

(

pirum), plum (

Слайд 15

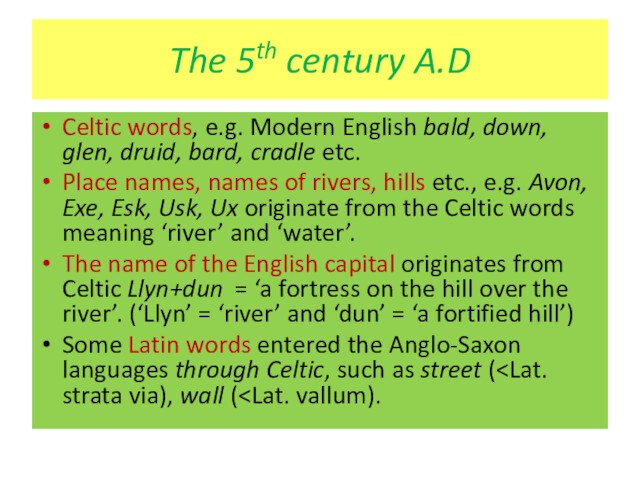

The 5th century A.D

Celtic words, e.g. Modern English

bald, down, glen, druid, bard, cradle etc.

Place names,

names of rivers, hills etc., e.g. Avon, Exe, Esk, Usk,

Ux originate from the Celtic words meaning ‘river’ and ‘water’.

The name of the English capital originates from Celtic Llyn+dun = ‘a fortress on the hill over the river’. (‘Llyn’ = ‘river’ and ‘dun’ = ‘a fortified hill’)

Some Latin words entered the Anglo-Saxon languages through Celtic, such as street (

Слайд 16

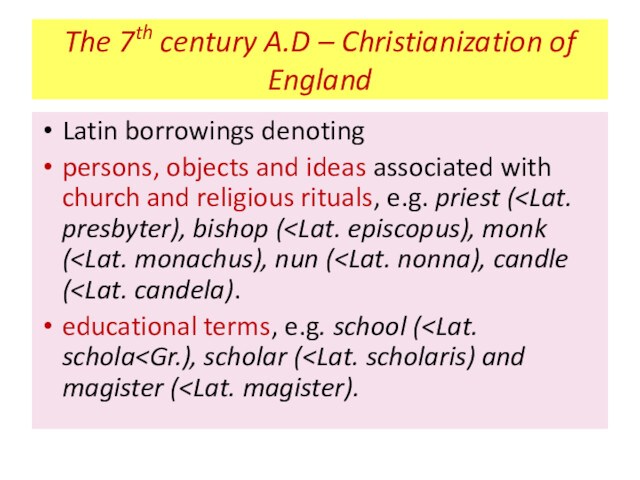

The 7th century A.D – Christianization of England

Latin

borrowings denoting

persons, objects and ideas associated with church and

religious rituals, e.g. priest (

(

educational terms, e.g. school (

Слайд 17

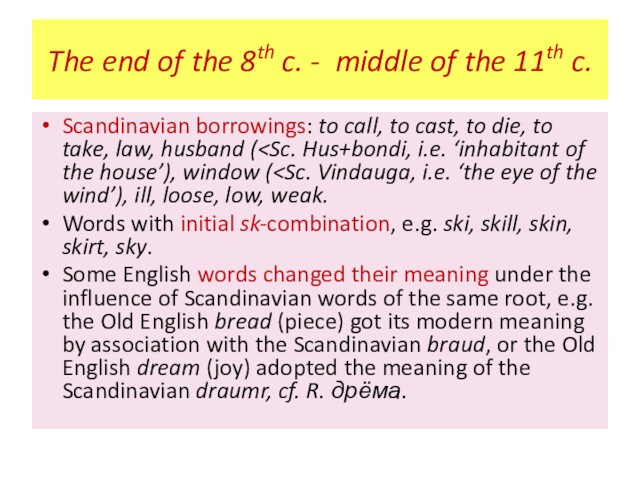

The end of the 8th c. — middle

of the 11th c.

Scandinavian borrowings: to call, to cast,

to die, to take, law, husband (

of the house’), window (

Words with initial sk-combination, e.g. ski, skill, skin, skirt, sky.

Some English words changed their meaning under the influence of Scandinavian words of the same root, e.g. the Old English bread (piece) got its modern meaning by association with the Scandinavian braud, or the Old English dream (joy) adopted the meaning of the Scandinavian draumr, cf. R. дрёма.

Слайд 18

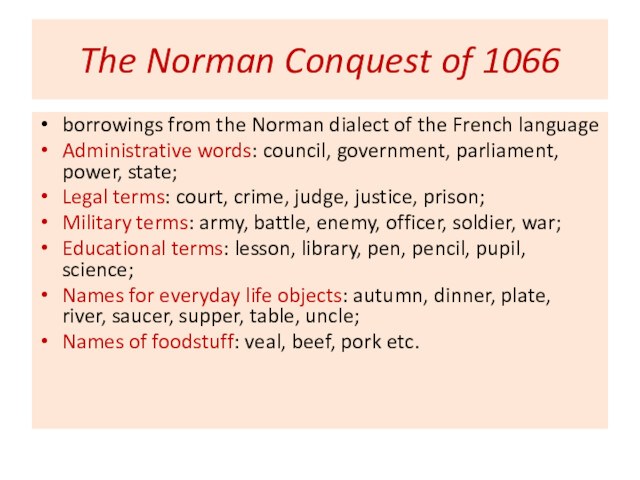

The Norman Conquest of 1066

borrowings from the Norman

dialect of the French language

Administrative words: council, government, parliament,

power, state;

Legal terms: court, crime, judge, justice, prison;

Military terms: army,

battle, enemy, officer, soldier, war;

Educational terms: lesson, library, pen, pencil, pupil, science;

Names for everyday life objects: autumn, dinner, plate, river, saucer, supper, table, uncle;

Names of foodstuff: veal, beef, pork etc.

Слайд 19

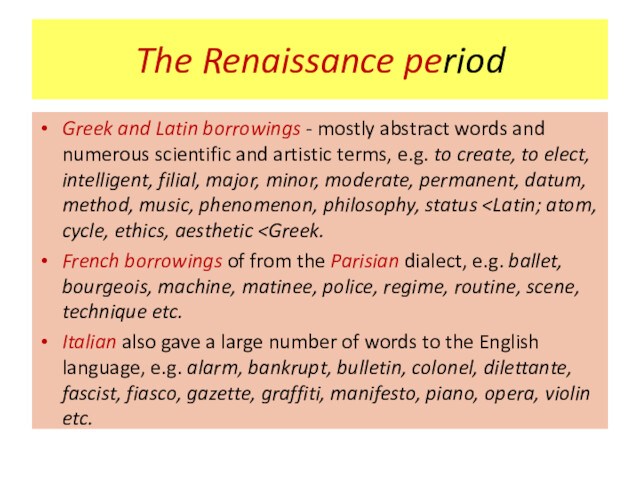

The Renaissance period

Greek and Latin borrowings — mostly

abstract words and numerous scientific and artistic terms, e.g.

to create, to elect, intelligent, filial, major, minor, moderate, permanent,

datum, method, music, phenomenon, philosophy, status

French borrowings of from the Parisian dialect, e.g. ballet, bourgeois, machine, matinee, police, regime, routine, scene, technique etc.

Italian also gave a large number of words to the English language, e.g. alarm, bankrupt, bulletin, colonel, dilettante, fascist, fiasco, gazette, graffiti, manifesto, piano, opera, violin etc.

Слайд 21

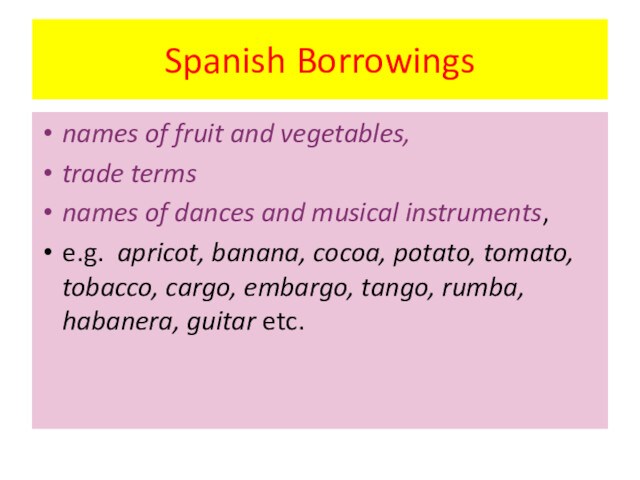

Spanish Borrowings

names of fruit and vegetables,

trade terms

names of dances and musical instruments,

e.g. apricot, banana, cocoa,

potato, tomato, tobacco, cargo, embargo, tango, rumba, habanera, guitar etc.

Слайд 22

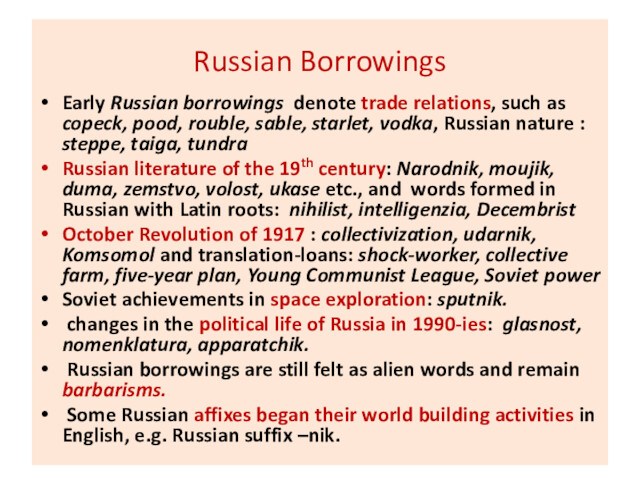

Russian Borrowings

Early Russian borrowings denote trade relations, such

as copeck, pood, rouble, sable, starlet, vodka, Russian nature

: steppe, taiga, tundra

Russian literature of the 19th century: Narodnik,

moujik, duma, zemstvo, volost, ukase etc., and words formed in Russian with Latin roots: nihilist, intelligenzia, Decembrist

October Revolution of 1917 : collectivization, udarnik, Komsomol and translation-loans: shock-worker, collective farm, five-year plan, Young Communist League, Soviet power

Soviet achievements in space exploration: sputnik.

changes in the political life of Russia in 1990-ies: glasnost, nomenklatura, apparatchik.

Russian borrowings are still felt as alien words and remain barbarisms.

Some Russian affixes began their world building activities in English, e.g. Russian suffix –nik.

Слайд 23

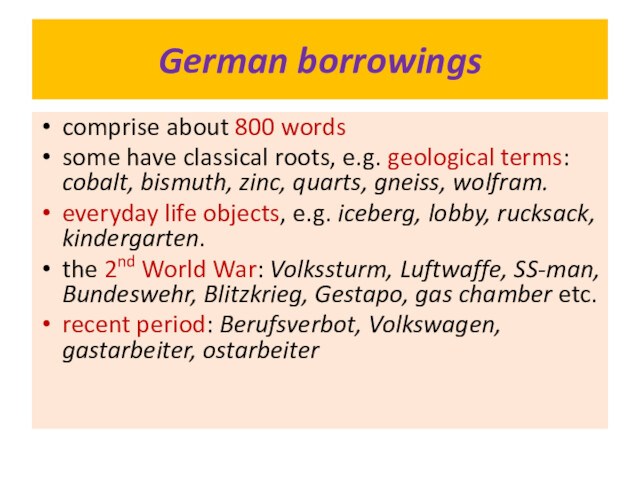

German borrowings

comprise about 800 words

some have classical roots,

e.g. geological terms: cobalt, bismuth, zinc, quarts, gneiss, wolfram.

everyday life objects, e.g. iceberg, lobby, rucksack, kindergarten.

the 2nd

World War: Volkssturm, Luftwaffe, SS-man, Bundeswehr, Blitzkrieg, Gestapo, gas chamber etc.

recent period: Berufsverbot, Volkswagen, gastarbeiter, ostarbeiter

Слайд 24

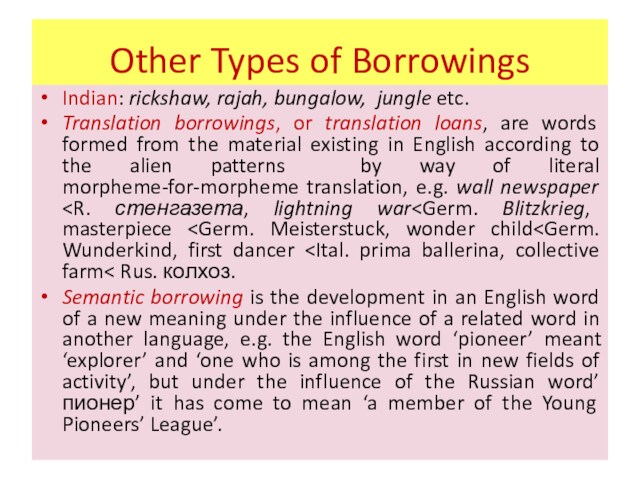

Other Types of Borrowings

Indian: rickshaw, rajah, bungalow, jungle

etc.

Translation borrowings, or translation loans, are words formed from

the material existing in English according to the alien patterns

by way of literal morpheme-for-morpheme translation, e.g. wall newspaper

Semantic borrowing is the development in an English word of a new meaning under the influence of a related word in another language, e.g. the English word ‘pioneer’ meant ‘explorer’ and ‘one who is among the first in new fields of activity’, but under the influence of the Russian word’пионер’ it has come to mean ‘a member of the Young Pioneers’ League’.

Слайд 25

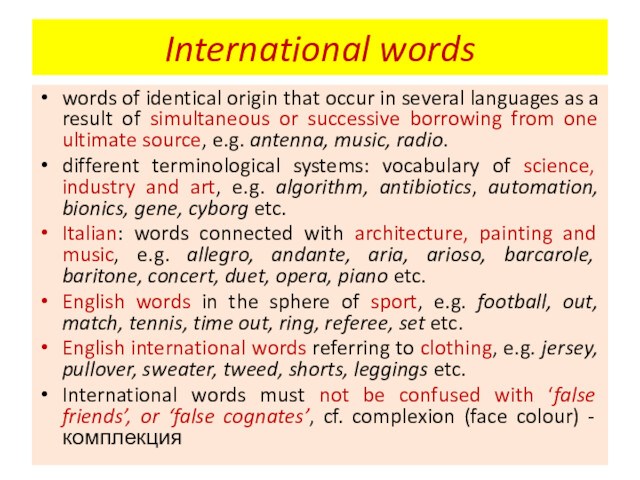

International words

words of identical origin that occur in

several languages as a result of simultaneous or successive

borrowing from one ultimate source, e.g. antenna, music, radio.

different

terminological systems: vocabulary of science, industry and art, e.g. algorithm, antibiotics, automation, bionics, gene, cyborg etc.

Italian: words connected with architecture, painting and music, e.g. allegro, andante, aria, arioso, barcarole, baritone, concert, duet, opera, piano etc.

English words in the sphere of sport, e.g. football, out, match, tennis, time out, ring, referee, set etc.

English international words referring to clothing, e.g. jersey, pullover, sweater, tweed, shorts, leggings etc.

International words must not be confused with ‘false friends’, or ‘false cognates’, cf. complexion (face colour) — комплекция

Слайд 26

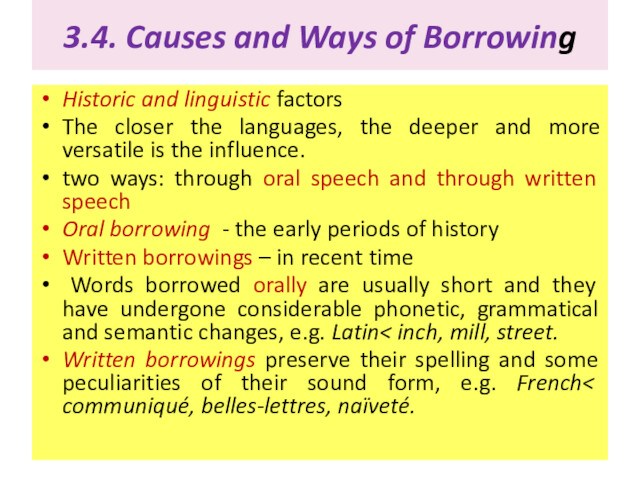

3.4. Causes and Ways of Borrowing

Historic and linguistic

factors

The closer the languages, the deeper and more versatile

is the influence.

two ways: through oral speech and through written

speech

Oral borrowing — the early periods of history

Written borrowings – in recent time

Words borrowed orally are usually short and they have undergone considerable phonetic, grammatical and semantic changes, e.g. Latin< inch, mill, street.

Written borrowings preserve their spelling and some peculiarities of their sound form, e.g. French< communiqué, belles-lettres, naïveté.

Слайд 27

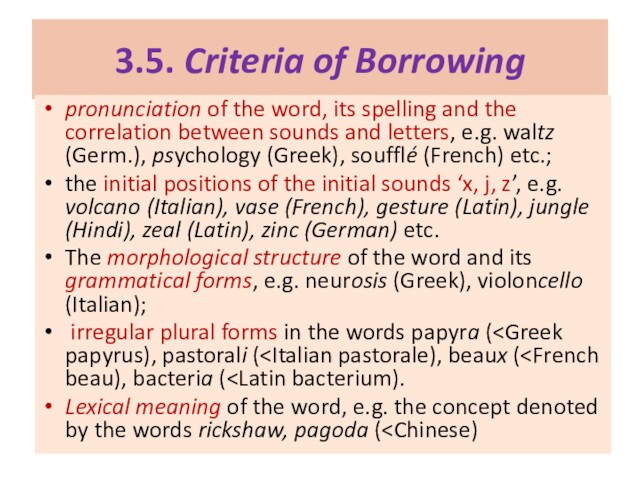

3.5. Criteria of Borrowing

pronunciation of the word, its

spelling and the correlation between sounds and letters, e.g.

waltz (Germ.), psychology (Greek), soufflé (French) etc.;

the initial positions

of the initial sounds ‘x, j, z’, e.g. volcano (Italian), vase (French), gesture (Latin), jungle (Hindi), zeal (Latin), zinc (German) etc.

The morphological structure of the word and its grammatical forms, e.g. neurosis (Greek), violoncello (Italian);

irregular plural forms in the words papyra (

Lexical meaning of the word, e.g. the concept denoted by the words rickshaw, pagoda (

Слайд 28

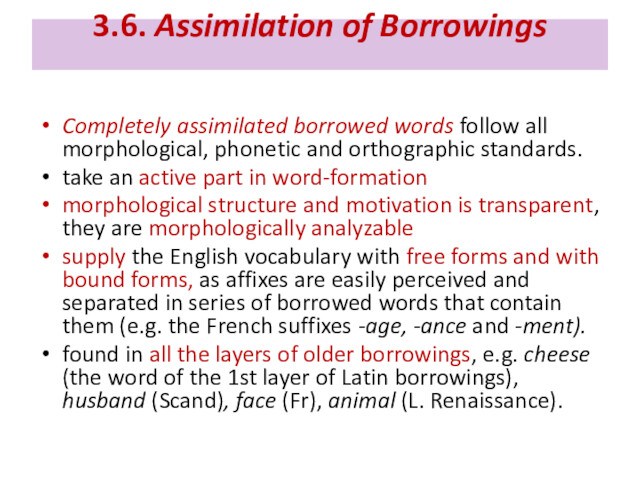

3.6. Assimilation of Borrowings

Completely assimilated borrowed words follow

all morphological, phonetic and orthographic standards.

take an active

part in word-formation

morphological structure and motivation is transparent, they

are morphologically analyzable

supply the English vocabulary with free forms and with bound forms, as affixes are easily perceived and separated in series of borrowed words that contain them (e.g. the French suffixes -age, -ance and -ment).

found in all the layers of older borrowings, e.g. cheese (the word of the 1st layer of Latin borrowings), husband (Scand), face (Fr), animal (L. Renaissance).

Слайд 29

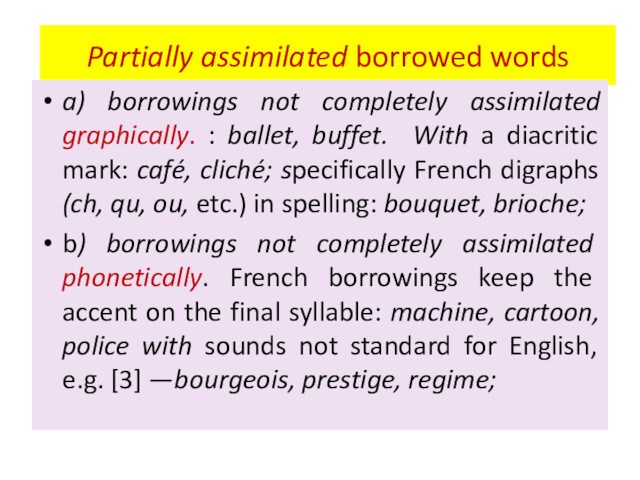

Partially assimilated borrowed words

a) borrowings not completely assimilated

graphically. : ballet, buffet. With a diacritic mark: café,

cliché; specifically French digraphs (ch, qu, ou, etc.) in spelling:

bouquet, brioche;

b) borrowings not completely assimilated phonetically. French borrowings keep the accent on the final syllable: machine, cartoon, police with sounds not standard for English, e.g. [3] —bourgeois, prestige, regime;

Слайд 30

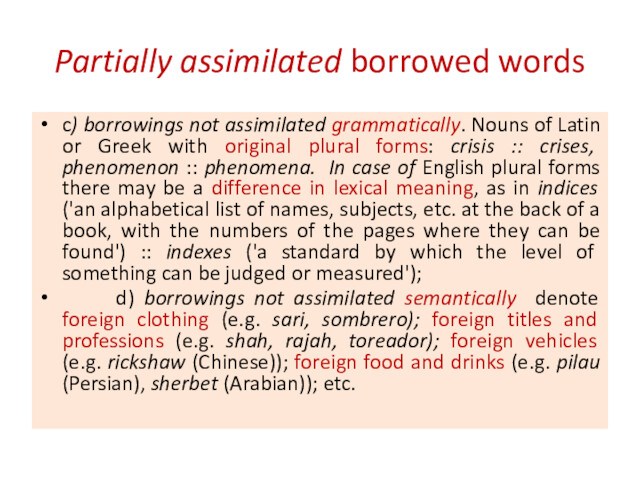

Partially assimilated borrowed words

c) borrowings not assimilated grammatically.

Nouns of Latin or Greek with original plural forms:

crisis :: crises, phenomenon :: phenomena. In case of English

plural forms there may be a difference in lexical meaning, as in indices (‘an alphabetical list of names, subjects, etc. at the back of a book, with the numbers of the pages where they can be found’) :: indexes (‘a standard by which the level of something can be judged or measured’);

d) borrowings not assimilated semantically denote foreign clothing (e.g. sari, sombrero); foreign titles and professions (e.g. shah, rajah, toreador); foreign vehicles (e.g. rickshaw (Chinese)); foreign food and drinks (e.g. pilau (Persian), sherbet (Arabian)); etc.

Слайд 31

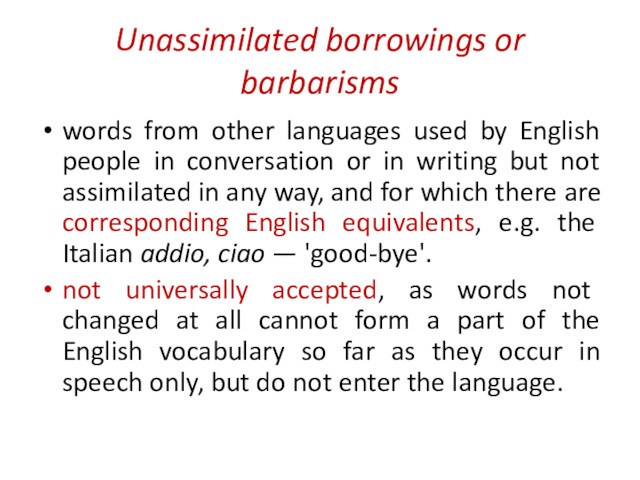

Unassimilated borrowings or barbarisms

words from other languages used

by English people in conversation or in writing but

not assimilated in any way, and for which there are

corresponding English equivalents, e.g. the Italian addio, ciao — ‘good-bye’.

not universally accepted, as words not changed at all cannot form a part of the English vocabulary so far as they occur in speech only, but do not enter the language.

Слайд 32

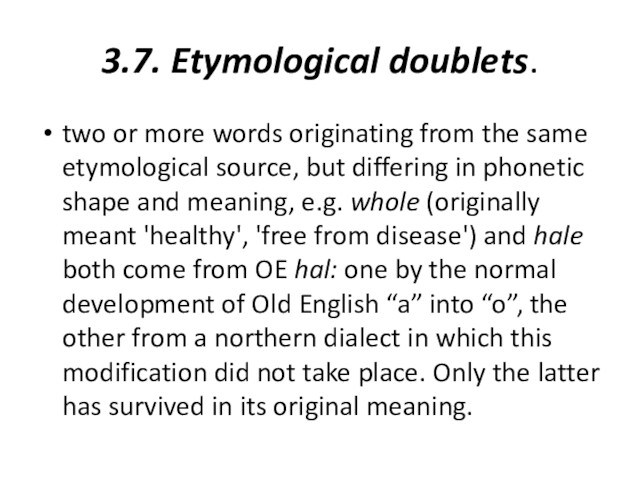

3.7. Etymological doublets.

two or more words originating

from the same etymological source, but differing in phonetic

shape and meaning, e.g. whole (originally meant ‘healthy’, ‘free from

disease’) and hale both come from OE hal: one by the normal development of Old English “a” into “o”, the other from a northern dialect in which this modification did not take place. Only the latter has survived in its original meaning.

Слайд 33

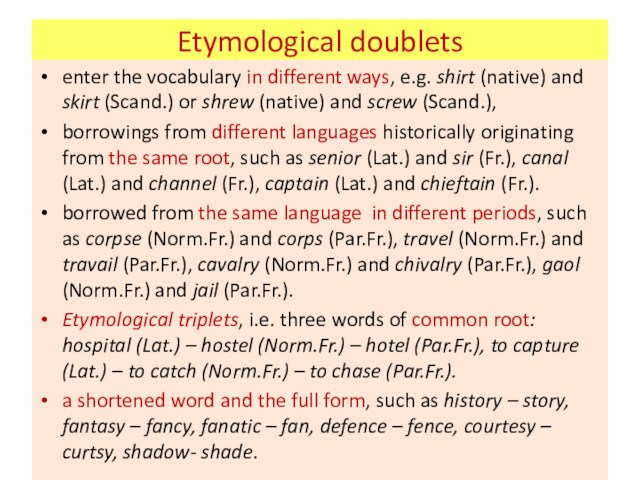

Etymological doublets

enter the vocabulary in different ways, e.g.

shirt (native) and skirt (Scand.) or shrew (native) and

screw (Scand.),

borrowings from different languages historically originating from the

same root, such as senior (Lat.) and sir (Fr.), canal (Lat.) and channel (Fr.), captain (Lat.) and chieftain (Fr.).

borrowed from the same language in different periods, such as corpse (Norm.Fr.) and corps (Par.Fr.), travel (Norm.Fr.) and travail (Par.Fr.), cavalry (Norm.Fr.) and chivalry (Par.Fr.), gaol (Norm.Fr.) and jail (Par.Fr.).

Etymological triplets, i.e. three words of common root: hospital (Lat.) – hostel (Norm.Fr.) – hotel (Par.Fr.), to capture (Lat.) – to catch (Norm.Fr.) – to chase (Par.Fr.).

a shortened word and the full form, such as history – story, fantasy – fancy, fanatic – fan, defence – fence, courtesy – curtsy, shadow- shade.

Слайд 34

3.8. Influence of borrowings

1) the phonetic structure of

English words and the sound system;

2) the word-structure

and the system of word-building;

3) the semantic structure of English

words;

4) the lexical territorial divergence.

Слайд 35

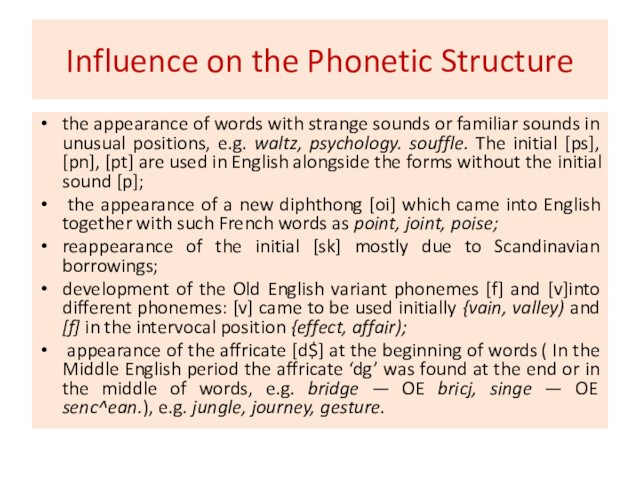

Influence on the Phonetic Structure

the appearance of words

with strange sounds or familiar sounds in unusual positions,

e.g. waltz, psychology. souffle. The initial [ps], [pn], [pt] are

used in English alongside the forms without the initial sound [p];

the appearance of a new diphthong [oi] which came into English together with such French words as point, joint, poise;

reappearance of the initial [sk] mostly due to Scandinavian borrowings;

development of the Old English variant phonemes [f] and [v]into different phonemes: [v] came to be used initially {vain, valley) and [f] in the intervocal position {effect, affair);

appearance of the affricate [d$] at the beginning of words ( In the Middle English period the affricate ‘dg’ was found at the end or in the middle of words, e.g. bridge — OE bricj, singe — OE senc^ean.), e.g. jungle, journey, gesture.

Слайд 36

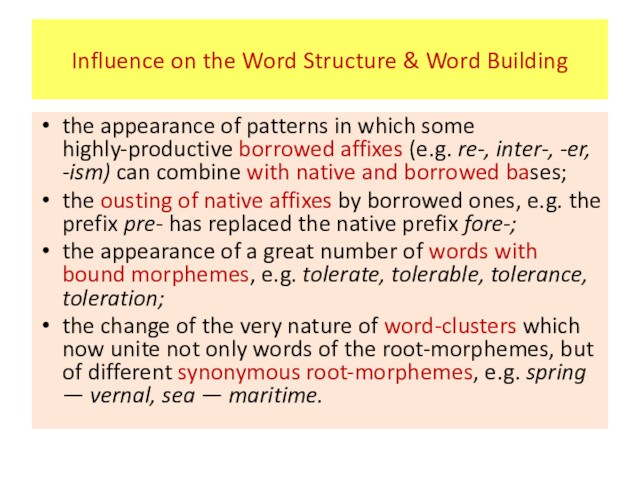

Influence on the Word Structure & Word Building

the

appearance of patterns in which some highly-productive borrowed affixes

(e.g. re-, inter-, -er, -ism) can combine with native and

borrowed bases;

the ousting of native affixes by borrowed ones, e.g. the prefix pre- has replaced the native prefix fore-;

the appearance of a great number of words with bound morphemes, e.g. tolerate, tolerable, tolerance, toleration;

the change of the very nature of word-clusters which now unite not only words of the root-morphemes, but of different synonymous root-morphemes, e.g. spring — vernal, sea — maritime.

Слайд 37

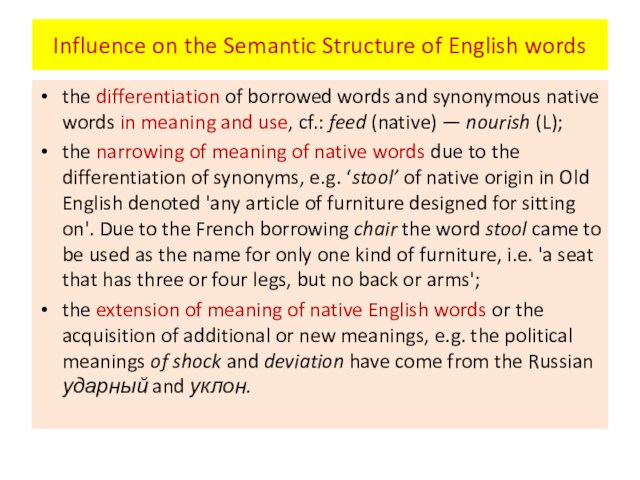

Influence on the Semantic Structure of English words

the

differentiation of borrowed words and synonymous native

words in meaning

and use, cf.: feed (native) — nourish (L);

the narrowing of

meaning of native words due to the differentiation of synonyms, e.g. ‘stool’ of native origin in Old English denoted ‘any article of furniture designed for sitting on’. Due to the French borrowing chair the word stool came to be used as the name for only one kind of furniture, i.e. ‘a seat that has three or four legs, but no back or arms’;

the extension of meaning of native English words or the acquisition of additional or new meanings, e.g. the political meanings of shock and deviation have come from the Russian ударный and уклон.

Слайд 38

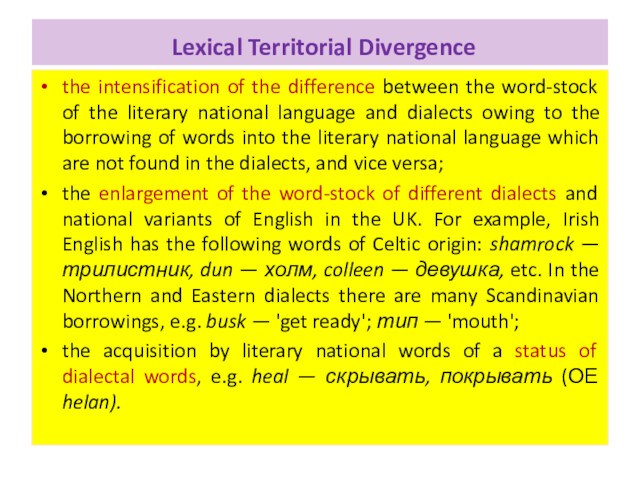

Lexical Territorial Divergence

the intensification of the difference

between the word-stock of the literary national language and

dialects owing to the borrowing of words into the literary

national language which are not found in the dialects, and vice versa;

the enlargement of the word-stock of different dialects and national variants of English in the UK. For example, Irish English has the following words of Celtic origin: shamrock — трилистник, dun — холм, colleen — девушка, etc. In the Northern and Eastern dialects there are many Scandinavian borrowings, e.g. busk — ‘get ready’; тип — ‘mouth’;

the acquisition by literary national words of a status of dialectal words, e.g. heal — скрывать, покрывать (ОЕ helan).