«English nation» redirects here. For the country of the United Kingdom, see England.

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| United Kingdom: 37.6 million in England and Wales[1] |

|

| Significant English diaspora in | |

| United States | 25.2 million[2] (2020)a |

| Australia | 8.3 million[3] (2021)b |

| Canada | 6.3 million[4] (2016)c |

| South Africa | 40,000-1.6 million[5] (2011)d |

| New Zealand | 210,915[6] (2018)e |

| Argentina | 100,000[7] |

| Languages | |

| English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, traditionally Anglicanism, but also non-conformists and dissenters (see History of the Church of England), as well as other Protestants; also Roman Catholicism (see Catholic Emancipation); Islam (see Islam in England); Judaism and other faiths (see Religion in England) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

|

|

a English American, b English Australian, c English Canadian, d British diaspora in Africa, e English New Zealander |

The English people are an ethnic group and nation native to England, who speak the English language, a West Germanic language, and share a common history and culture.[8] The English identity began with the Anglo-Saxons, when they were known as the Angelcynn, meaning race or tribe of the Angles. Their ethnonym is derived from the Angles, one of the Germanic peoples who migrated to Great Britain around the 5th century AD.[9]

The English largely descend from two main historical population groups: the West Germanic tribes, including the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and Frisians who settled in Southern Britain following the withdrawal of the Romans, and the partially Romanised Celtic Britons who already lived there.[10][11][12][13] Collectively known as the Anglo-Saxons, they founded what was to become the Kingdom of England by the early 10th century, in response to the invasion and extensive settlement of Danes that began in the late 9th century.[14][15] This was followed by the Norman Conquest and limited settlement of Normans in England in the later 11th century.[16][17][18][10][19] Some definitions of English people include, while others exclude, people descended from later migration into England.[20]

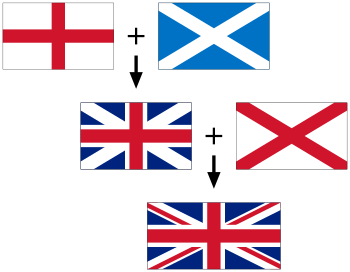

England is the largest and most populous country in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. In the Acts of Union 1707, the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland merged to become the Kingdom of Great Britain.[21] Over the years, English customs and identity have become fairly closely aligned with British customs and identity in general. The majority of people living in England are British citizens.

English nationality[edit]

England itself has no devolved government. The 1990s witnessed a rise in English self-awareness.[22] This is linked to the expressions of national self-awareness of the other British nations of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland which take their most solid form in the new devolved political arrangements within the United Kingdom – and the waning of a shared British national identity with the growing distance between the end of the British Empire and the present.[23][24][25]

Many recent immigrants to England have assumed a solely British identity, while others have developed dual or mixed identities.[26][27][28][29][30] Use of the word «English» to describe Britons from ethnic minorities in England is complicated by most non-white people in England identifying as British rather than English. In their 2004 Annual Population Survey, the Office for National Statistics compared the ethnic identities of British people with their perceived national identity. They found that while 58% of white people in England described their nationality as «English», non-white people were more likely to describe themselves as «British».[31]

Relationship to Britishness[edit]

It is unclear how many British people consider themselves English. The words «English» and «British» are often incorrectly used interchangeably, especially outside the UK. In his study of English identity, Krishan Kumar describes a common slip of the tongue in which people say «English, I mean British». He notes that this slip is normally made only by the English themselves and by foreigners: «Non-English members of the United Kingdom rarely say ‘British’ when they mean ‘English'». Kumar suggests that although this blurring is a sign of England’s dominant position with the UK, it is also «problematic for the English […] when it comes to conceiving of their national identity. It tells of the difficulty that most English people have of distinguishing themselves, in a collective way, from the other inhabitants of the British Isles».[32]

In 1965, the historian A. J. P. Taylor wrote,

When the Oxford History of England was launched a generation ago, «England» was still an all-embracing word. It meant indiscriminately England and Wales; Great Britain; the United Kingdom; and even the British Empire. Foreigners used it as the name of a Great Power and indeed continue to do so. Bonar Law, by origin a Scotch Canadian, was not ashamed to describe himself as «Prime Minister of England» […] Now terms have become more rigorous. The use of «England» except for a geographic area brings protests, especially from the Scotch.[33]

However, although Taylor believed this blurring effect was dying out, in his book The Isles: A History (1999), Norman Davies lists numerous examples in history books of «British» still being used to mean «English» and vice versa.[34]

In December 2010, Matthew Parris in The Spectator, analysing the use of «English» over «British», argued that English identity, rather than growing, had existed all along but has recently been unmasked from behind a veneer of Britishness.[35]

Historical and genetic origins[edit]

Replacement of Neolithic farmers by Bell Beaker populations[edit]

English people, like most Europeans, largely descend from three distinct lineages:[36] Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, descended from a Cro-Magnon population that arrived in Europe about 45,000 years ago;[37] Neolithic farmers who migrated from Anatolia during the Neolithic Revolution 9,000 years ago;[38] and Yamnaya Steppe pastoralists who expanded into Europe from the Pontic–Caspian steppe in the context of Indo-European migrations 5,000 years ago.[36]

Recent genetic studies have suggested that Britain’s Neolithic population was largely replaced by a population from North Continental Europe characterised by the Bell Beaker culture around 2400 BC, associated with the Yamnaya people from the Pontic-Caspian Steppe. This population lacked genetic affinity to some other Bell Beaker populations, such as the Iberian Bell Beakers, but appeared to be an offshoot of the Corded Ware single grave people, as developed in Western Europe.[39][40] It is currently unknown whether these Beaker peoples went on to develop Celtic languages in the British Isles, or whether later Celtic migrations introduced Celtic languages to Britain.[41]

The close genetic affinity of these Beaker people to Continental North Europeans means that British and Irish populations cluster genetically very closely with other Northwest European populations, regardless of how much Anglo-Saxon and Viking ancestry was introduced during the 1st millennium.[42][39]

Anglo-Saxons, Vikings and Normans[edit]

The influence of later invasions and migrations on the English population has been debated, as studies that sampled only modern DNA have produced uncertain results and have thus been subject to a large variety of interpretations.[43][44][45] More recently, however, ancient DNA has been used to provide a clearer picture of the genetic effects of these movements of people.

One 2016 study, using Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon era DNA found at grave sites in Cambridgeshire, calculated that ten modern day eastern English samples had 38% Anglo-Saxon ancestry on average, while ten Welsh and Scottish samples each had 30% Anglo-Saxon ancestry, with a large statistical spread in all cases. However, the authors noted that the similarity observed between the various sample groups was likely to be due to more recent internal migration.[46]

Another 2016 study conducted using evidence from burials found in northern England, found that a significant genetic difference was present in bodies from the Iron Age and the Roman period on the one hand, and the Anglo-Saxon period on the other. Samples from modern-day Wales were found to be similar to those from the Iron Age and Roman burials, while samples from much of modern England, East Anglia in particular, were closer to the Anglo-Saxon-era burial. This was found to demonstrate a «profound impact» from the Anglo-Saxon migrations on the modern English gene pool, though no specific percentages were given in the study.[12]

A third study combined the ancient data from both of the preceding studies and compared it to a large number of modern samples from across Britain and Ireland. This study found that modern southern, central and eastern English populations were of «a predominantly Anglo-Saxon-like ancestry» while those from northern and southwestern England had a greater degree of indigenous origin.[47]

A major 2020 study, which used DNA from Viking-era burials in various regions across Europe, found that modern English samples showed nearly equal contributions from a native British «North Atlantic» population and a Danish-like population. While much of the latter signature was attributed to the earlier settlement of the Anglo-Saxons, it was calculated that up to 6% of it could have come from Danish Vikings, with a further 4% contribution from a Norwegian-like source representing the Norwegian Vikings. The study also found an average 18% admixture from a source further south in Europe, which was interpreted as reflecting the legacy of French migration under the Normans.[48]

A landmark 2022 study titled «The Anglo-Saxon migration and the formation of the early English gene pool», found the English to be of plurality Anglo-Saxon-like ancestry, with heavy native Celtic Briton, and newly confirmed medieval French admixture. Significant regional variation was also observed.[49]

History of English people[edit]

«History of the English» redirects here. Not to be confused with History of English.

Anglo-Saxon settlement[edit]

The first people to be called «English» were the Anglo-Saxons, a group of closely related Germanic tribes that began migrating to eastern and southern Great Britain, from southern Denmark and northern Germany, in the 5th century AD, after the Romans had withdrawn from Britain. The Anglo-Saxons gave their name to England («Engla land», meaning «Land of the Angles») and to the English.

The Anglo-Saxons arrived in a land that was already populated by people commonly referred to as the «Romano-British»—the descendants of the native Brittonic-speaking population that lived in the area of Britain under Roman rule during the 1st–5th centuries AD. The multi-ethnic nature of the Roman Empire meant that small numbers of other peoples may have also been present in England before the Anglo-Saxons arrived. There is archaeological evidence, for example, of an early North African presence in a Roman garrison at Aballava, now Burgh-by-Sands, in Cumbria: a 4th-century inscription says that the Roman military unit «Numerus Maurorum Aurelianorum» («unit of Aurelian Moors») from Mauretania (Morocco) was stationed there.[50] Although the Roman Empire incorporated peoples from far and wide, genetic studies suggest the Romans did not significantly mix into the British population.[51]

Southern Great Britain in AD 600 after the Anglo-Saxon settlement, showing England’s division into multiple petty kingdoms

The exact nature of the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons and their relationship with the Romano-British is a matter of debate. The traditional view is that a mass invasion by various Anglo-Saxon tribes largely displaced the indigenous British population in southern and eastern Great Britain (modern-day England with the exception of Cornwall). This is supported by the writings of Gildas, who gives the only contemporary historical account of the period, and describes the slaughter and starvation of native Britons by invading tribes (aduentus Saxonum).[52] Furthermore, the English language contains no more than a handful of words borrowed from Brittonic sources.[53]

This view was later re-evaluated by some archaeologists and historians, with a more small-scale migration being posited, possibly based around an elite of male warriors that took over the rule of the country and gradually acculturated the people living there.[54][55][56] Within this theory, two processes leading to Anglo-Saxonisation have been proposed. One is similar to culture changes observed in Russia, North Africa and parts of the Islamic world, where a politically and socially powerful minority culture becomes, over a rather short period, adopted by a settled majority. This process is usually termed «elite dominance».[57] The second process is explained through incentives, such as the Wergild outlined in the law code of Ine of Wessex which produced an incentive to become Anglo-Saxon or at least English speaking.[58] Historian Malcolm Todd writes, «It is much more likely that a large proportion of the British population remained in place and was progressively dominated by a Germanic aristocracy, in some cases marrying into it and leaving Celtic names in the, admittedly very dubious, early lists of Anglo-Saxon dynasties. But how we identify the surviving Britons in areas of predominantly Anglo-Saxon settlement, either archaeologically or linguistically, is still one of the deepest problems of early English history.»[59]

An emerging view is that the degree of population replacement by the Anglo-Saxons, and thus the degree of survival of the Romano-Britons, varied across England, and that as such the overall settlement of Britain by the Anglo-Saxons cannot be described by any one process in particular. Large-scale migration and population shift seems to be most applicable in the cases of eastern regions such as East Anglia and Lincolnshire,[60][61][62][63][64] while in parts of Northumbria, much of the native population likely remained in place as the incomers took over as elites.[65][66] In a study of place names in northeastern England and southern Scotland, Bethany Fox found that the migrants settled in large numbers in river valleys, such as those of the Tyne and the Tweed, with the Britons moving to the less fertile hill country and becoming acculturated over a longer period. Fox describes the process by which English came to dominate this region as «a synthesis of mass-migration and elite-takeover models.»[67]

Vikings and the Danelaw[edit]

Æthelred II (Old English: Æþelræd;[a] c. 966 – 23 April 1016), known as ‘the Unready’, was King of the English from 978 to 1013 and again from 1014 until his death.

From about 800 AD waves of Danish Viking assaults on the coastlines of the British Isles were gradually followed by a succession of Danish settlers in England. At first, the Vikings were very much considered a separate people from the English. This separation was enshrined when Alfred the Great signed the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum to establish the Danelaw, a division of England between English and Danish rule, with the Danes occupying northern and eastern England.[68]

However, Alfred’s successors subsequently won military victories against the Danes, incorporating much of the Danelaw into the nascent kingdom of England. Danish invasions continued into the 11th century, and there were both English and Danish kings in the period following the unification of England (for example, Æthelred II (978–1013 and 1014–1016) was English but Cnut (1016–1035) was Danish).

Gradually, the Danes in England came to be seen as ‘English’. They had a noticeable impact on the English language: many English words, such as anger, ball, egg, got, knife, take, and they, are of Old Norse origin,[69] and place names that end in -thwaite and -by are Scandinavian in origin.[70]

English unification[edit]

The English population was not politically unified until the 10th century. Before then, there were a number of petty kingdoms which gradually coalesced into a heptarchy of seven states, the most powerful of which were Mercia and Wessex. The English nation state began to form when the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms united against Danish Viking invasions, which began around 800 AD. Over the following century and a half England was for the most part a politically unified entity, and remained permanently so after 959.

The nation of England was formed in 937 by Æthelstan of Wessex after the Battle of Brunanburh,[71][72] as Wessex grew from a relatively small kingdom in the South West to become the founder of the Kingdom of the English, incorporating all Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and the Danelaw.[73]

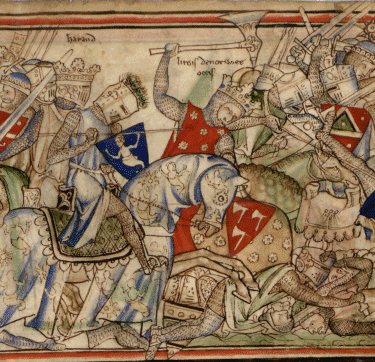

Norman and Angevin rule[edit]

The Norman conquest of England during 1066 brought Anglo-Saxon and Danish rule of England to an end, as the new French speaking Norman elite almost universally replaced the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy and church leaders. After the conquest, «English» normally included all natives of England, whether they were of Anglo-Saxon, Scandinavian or Celtic ancestry, to distinguish them from the Norman invaders, who were regarded as «Norman» even if born in England, for a generation or two after the Conquest.[74] The Norman dynasty ruled England for 87 years until the death of King Stephen in 1154, when the succession passed to Henry II, House of Plantagenet (based in France), and England became part of the Angevin Empire until 1214.

Various contemporary sources suggest that within 50 years of the invasion most of the Normans outside the royal court had switched to English, with Anglo-Norman remaining the prestige language of government and law largely out of social inertia. For example, Orderic Vitalis, a historian born in 1075 and the son of a Norman knight, said that he learned French only as a second language. Anglo-Norman continued to be used by the Plantagenet kings until Edward I came to the throne.[75] Over time the English language became more important even in the court, and the Normans were gradually assimilated, until, by the 14th century, both rulers and subjects regarded themselves as English and spoke the English language.[76]

Despite the assimilation of the Normans, the distinction between ‘English’ and ‘French’ survived in official documents long after it had fallen out of common use, in particular in the legal phrase Presentment of Englishry (a rule by which a hundred had to prove an unidentified murdered body found on their soil to be that of an Englishman, rather than a Norman, if they wanted to avoid a fine). This law was abolished in 1340.[77]

United Kingdom[edit]

Since the 18th century, England has been one part of a wider political entity covering all or part of the British Isles, which today is called the United Kingdom. Wales was annexed by England by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542, which incorporated Wales into the English state.[78] A new British identity was subsequently developed when James VI of Scotland became James I of England as well, and expressed the desire to be known as the monarch of Britain.[79]

In 1707, England formed a union with Scotland by passing an Act of Union in March 1707 that ratified the Treaty of Union. The Parliament of Scotland had previously passed its own Act of Union, so the Kingdom of Great Britain was born on 1 May 1707. In 1801, another Act of Union formed a union between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland, creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. In 1922, about two-thirds of the Irish population (those who lived in 26 of the 32 counties of Ireland), left the United Kingdom to form the Irish Free State. The remainder became the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, although this name was not introduced until 1927, after some years in which the term «United Kingdom» had been little used.[citation needed]

Throughout the history of the UK, the English have been dominant in population and in political weight. As a consequence, notions of ‘Englishness’ and ‘Britishness’ are often very similar. At the same time, after the Union of 1707, the English, along with the other peoples of the British Isles, have been encouraged to think of themselves as British rather than to identify themselves with the constituent nations.[80]

Immigration and assimilation[edit]

England has been the destination of varied numbers of migrants at different periods from the 17th century onwards. While some members of these groups seek to practise a form of pluralism, attempting to maintain a separate ethnic identity, others have assimilated and intermarried with the English. Since Oliver Cromwell’s resettlement of the Jews in 1656, there have been waves of Jewish immigration from Russia in the 19th century and from Germany in the 20th.[81]

After the French king Louis XIV declared Protestantism illegal in 1685 in the Edict of Fontainebleau, an estimated 50,000 Protestant Huguenots fled to England.[82] Due to sustained and sometimes mass emigration of the Irish, current estimates indicate that around 6 million people in the UK have at least one grandparent born in the Republic of Ireland.[83]

There has been a small black presence in England since the 16th century due to the slave trade,[84] and a small Indian presence since at least the 17th century because of the East India Company[85] and British Raj.[84] Black and Asian populations have only grown throughout the UK generally, as immigration from the British Empire and the subsequent Commonwealth of Nations was encouraged due to labour shortages during post World War II rebuilding.[86]

However, these groups are often still considered to be ethnic minorities and research has shown that black and Asian people in the UK are more likely to identify as British rather than with one of the state’s four constituent nations, including England.[87]

A nationally representative survey published in June 2021 found that a majority of respondents thought that being English was not dependent on race. 77% of white respondents in England agreed that «Being English is open to people of different ethnic backgrounds who identify as English», whereas 14% were of the view that «Only people who are white count as truly English». Amongst ethnic minority respondents, the equivalent figures were 68% and 19%.[88] Research has found that the proportion of people who consider being white to be a necessary component of Englishness has declined over time.[89]

Current national and political identity[edit]

The 1990s witnessed a resurgence of English national identity.[90] Survey data shows a rise in the number of people in England describing their national identity as English and a fall in the number describing themselves as British.[91] Today, black and minority ethnic people of England still generally identify as British rather than English to a greater extent than their white counterparts;[92] however, groups such as the Campaign for an English Parliament (CEP) suggest the emergence of a broader civic and multi-ethnic English nationhood.[93] Scholars and journalists have noted a rise in English self-consciousness, with increased use of the English flag, particularly at football matches where the Union flag was previously more commonly flown by fans.[94][95]

This perceived rise in English self-consciousness has generally been attributed to the devolution in the late 1990s of some powers to the Scottish Parliament and National Assembly for Wales.[90] In policy areas for which the devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have responsibility, the UK Parliament votes on laws that consequently only apply to England. Because the Westminster Parliament is composed of MPs from throughout the United Kingdom, this has given rise to the «West Lothian question», a reference to the situation in which MPs representing constituencies outside England can vote on matters affecting only England, but MPs cannot vote on the same matters in relation to the other parts of the UK.[96] Consequently, groups such as the CEP have called for the creation of a devolved English Parliament, claiming that there is now a discriminatory democratic deficit against the English. The establishment of an English parliament has also been backed by a number of Scottish and Welsh nationalists.[97][98] Writer Paul Johnson has suggested that like most dominant groups, the English have only demonstrated interest in their ethnic self-definition when they were feeling oppressed.[99]

John Curtice argues that «In the early years of devolution…there was little sign» of an English backlash against devolution for Scotland and Wales, but that more recently survey data shows tentative signs of «a form of English nationalism…beginning to emerge among the general public».[100] Michael Kenny, Richard English and Richard Hayton, meanwhile, argue that the resurgence in English nationalism predates devolution, being observable in the early 1990s, but that this resurgence does not necessarily have negative implications for the perception of the UK as a political union.[101] Others question whether devolution has led to a rise in English national identity at all, arguing that survey data fails to portray the complex nature of national identities, with many people considering themselves both English and British.[102]

Recent surveys of public opinion on the establishment of an English parliament have given widely varying conclusions. In the first five years of devolution for Scotland and Wales, support in England for the establishment of an English parliament was low at between 16 and 19%, according to successive British Social Attitudes Surveys.[103] A report, also based on the British Social Attitudes Survey, published in December 2010 suggests that only 29% of people in England support the establishment of an English parliament, though this figure had risen from 17% in 2007.[104]

One 2007 poll carried out for BBC Newsnight, however, found that 61 per cent would support such a parliament being established.[105] Krishan Kumar notes that support for measures to ensure that only English MPs can vote on legislation that applies only to England is generally higher than that for the establishment of an English parliament, although support for both varies depending on the timing of the opinion poll and the wording of the question.[106] Electoral support for English nationalist parties is also low, even though there is public support for many of the policies they espouse.[107] The English Democrats gained just 64,826 votes in the 2010 UK general election, accounting for 0.3 per cent of all votes cast in England.[108] Kumar argued in 2010 that «despite devolution and occasional bursts of English nationalism – more an expression of exasperation with the Scots or Northern Irish – the English remain on the whole satisfied with current constitutional arrangements».[109]

English diaspora[edit]

| Year | Country | Population | % of local population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Australia | 7,852,224 | 36.1[110] |

| 2016 | Canada | 6,320,085 | 18.3[111][112] |

| 2011 | Scotland | 459,486 | 8.68[113] |

| 2016 | United States[b] | 23,835,787 | 7.4[114] |

| 2018 | New Zealand | 72,204[c]–210,915[d] | 4.49[115] |

From the earliest times English people have left England to settle in other parts of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, but it is not possible to identify their numbers, as British censuses have historically not invited respondents to identify themselves as English.[116][failed verification] However, the census does record place of birth, revealing that 8.08% of Scotland’s population,[117] 3.66% of the population of Northern Ireland[118] and 20% of the Welsh population were born in England.[119] Similarly, the census of the Republic of Ireland does not collect information on ethnicity, but it does record that there are over 200,000 people living in Ireland who were born in England and Wales.[120]

English ethnic descent and emigrant communities are found primarily in the Western World, and in some places, settled in significant numbers. Substantial populations descended from English colonists and immigrants exist in the United States, Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand.[citation needed]

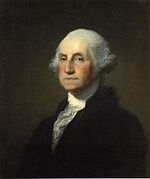

United States[edit]

In the 2016 American Community Survey, English Americans were 7.4% of the United States population, behind the German Americans (13.9%) and Irish Americans (10.0%).[114] However, demographers regard this as a serious undercount, as the index of inconsistency[clarification needed] is high, and many, if not most, people from English stock have a tendency (since the introduction of a new ‘American’ category in the 2000 census) to identify as simply Americans[122][123][124][125] or if of mixed European ancestry, identify with a more recent and differentiated ethnic group.[126]

Prior to this, in the 2000 census, 24,509,692 Americans described their ancestry as wholly or partly English. In addition, 1,035,133 recorded British ancestry.[127] This was a numerical decrease from the census in 1990 where 32,651,788 people or 13.1% of the population self-identified with English ancestry.[128]

In 1980, over 49 million (49,598,035) Americans claimed English ancestry, at the time around 26.34% of the total population and largest reported group which, even today, would make them the largest ethnic group in the United States.[129] Scots-Irish Americans are descendants of Lowland Scots and Northern English (specifically: County Durham, Cumberland, Northumberland and Westmorland) settlers who colonised Ireland during the Plantation of Ulster in the 17th century.

Americans of English heritage are often seen, and identify, as simply «American» due to the many historic cultural ties between England and the U.S. and their influence on the country’s population. Relative to ethnic groups of other European origins, this may be due to the early establishment of English settlements; as well as to non-English groups having emigrated in order to establish significant communities.[130]

Canada[edit]

In the Canada 2016 Census, ‘English’ was the most common ethnic origin (ethnic origin refers to the ethnic or cultural group(s) to which the respondent’s ancestors belong[131]) recorded by respondents; 6,320,085 people or 18.3% of the population self-identified themselves as wholly or partly English.[111][112] On the other hand, people identifying as Canadian but not English may have previously identified as English before the option of identifying as Canadian was available.[132]

Australia[edit]

From the beginning of the colonial era until the mid-20th century, the vast majority of settlers to Australia were from the British Isles, with the English being the dominant group. Among the leading ancestries, increases in Australian, Irish and German ancestries and decreases in English, Scottish and Welsh ancestries appear to reflect such shifts in perception or reporting. These reporting shifts at least partly resulted from changes in the design of the census question, in particular the introduction of a tick box format in 2001.[133] English Australians have more often come from the south than the north of England.[134]

Australians of English descent, are both the single largest ethnic group in Australia and the largest ‘ancestry’ identity in the Australian census.[135] In the 2016 census, 7.8 million or 36.1% of the population identified as «English» or a combination including English, a numerical increase from 7.2 million over the 2011 census figure. The census also documented 907,572 residents or 3.9% of Australia as being born in England, and are the largest overseas-born population.[110]

New Zealand[edit]

English ancestry is the largest single ancestry New Zealanders share. Several million New Zealanders are estimated to have some English ancestry[136] From 1840, the English comprised the largest single group among New Zealand’s overseas-born, consistently being over 50 percent of the total population.[137]

Despite this, after the early 1850s, the English-born slowly fell from being a majority of the colonial population. In the 1851 census, 50.5% of the total population were born in England, this proportion fell to 36.5% (1861) and 24.3% by 1881.[137]

In the most recent Census in 2013, there were 215,589 English-born representing 21.5% of all overseas-born residents or 5 percent of the total population and is still the most-common birthplace outside New Zealand.[138]

Argentina[edit]

English settlers arrived in Buenos Aires in 1806 (then a Spanish colony) in small numbers, mostly as businessmen, when Argentina was an emerging nation and the settlers were welcomed for the stability they brought to commercial life. As the 19th century progressed, more English families arrived, and many bought land to develop the potential of the Argentine pampas for the large-scale growing of crops. The English founded banks, developed the export trade in crops and animal products and imported the luxuries that the growing Argentine middle classes sought.[139]

As well as those who went to Argentina as industrialists and major landowners, others went as railway engineers, civil engineers and to work in banking and commerce. Others went to become whalers, missionaries and simply to seek out a future. English families sent second and younger sons, or what were described as the black sheep of the family, to Argentina to make their fortunes in cattle and wheat. English settlers introduced football to Argentina. Some English families owned sugar plantations.[citation needed]

Culture[edit]

The culture of England is sometimes difficult to separate clearly from the culture of the United Kingdom,[140] so influential has English culture been on the cultures of the British Isles and, on the other hand, given the extent to which other cultures have influenced life in England.

Religion[edit]

The established religion of the realm is the Church of England, whose titular head is Charles III although the worldwide Anglican Communion is overseen by the General Synod of its bishops under the authority of Parliament. 26 of the church’s 42 bishops are Lords Spiritual, representing the church in the House of Lords. In 2010, the Church of England counted 25 million baptised members out of the 41 million Christians in Great Britain’s population of about 60 million;[141][142] around the same time, it also claimed to baptise one in eight newborn children.[143] Generally, anyone in England may marry or be buried at their local parish church, whether or not they have been baptised in the church.[144] Actual attendance has declined steadily since 1890,[145] with around one million, or 10% of the baptised population attending Sunday services on a regular basis (defined as once a month or more) and three million -roughly 15%- joining Christmas Eve and Christmas services.[146][147]

Saint George is recognised as the patron saint of England, and the flag of England consists of his cross. Before Edward III, the patron saint was St Edmund; and St Alban is also honoured as England’s first martyr.

A survey carried out in the end of 2008 by Ipsos MORI on behalf of The Catholic Agency For Overseas Development found the population of England and Wales to be 47.0% affiliated with the Church of England, which is also the state church, 9.6% with the Roman Catholic Church and 8.7% were other Christians, mainly Free church Protestants and Eastern Orthodox Christians. 4.8% were Muslim, 3.4% were members of other religions, 5.3% were agnostics, 6.8% were atheists and 15.0% were not sure about their religious affiliation or refused to answer to the question.[148]

Religious observance of St George’s Day (23 April) changes when it is too close to Easter. According to the Church of England’s calendar, when St George’s Day falls between Palm Sunday and the Second Sunday of Easter inclusive, it is moved to the Monday after the Second Sunday of Easter.[149]

Language[edit]

Map showing phonological variation within England of the vowel in bath, grass, and dance:

‘a’ [ä]

‘aa’ [æː]

‘ah’ [ɑː]

anomalies

English people traditionally speak the English language, a member of the West Germanic language family. The modern English language evolved from Middle English (the form of language in use by the English people from the 12th to the 15th century); Middle English was influenced lexically by Norman-French, Old French and Latin. In the Middle English period Latin was the language of administration and the nobility spoke Norman French. Middle English was itself derived from the Old English of the Anglo-Saxon period; in the Northern and Eastern parts of England the language of Danish settlers had influenced the language, a fact still evident in Northern English dialects.

There were once many different dialects of modern English in England, which were recorded in projects such as the English Dialect Dictionary (late 19th century) and the Survey of English Dialects (mid 20th century), but many of these have passed out of common usage as Standard English has become more widespread through education, the media and socio-economic pressures.[150]

Cornish, a Celtic language, is one of three existing Brittonic languages; its usage has been revived in Cornwall. Historically, another Brittonic Celtic language, Cumbric, was spoken in Cumbria in North West England, but it died out in the 11th century although traces of it can still be found in the Cumbrian dialect. Early Modern English began in the late 15th century with the introduction of the printing press to London and the Great Vowel Shift. Through the worldwide influence of the British Empire, English spread around the world from the 17th to mid-20th centuries. Through newspapers, books, the telegraph, the telephone, phonograph records, radio, satellite television, broadcasters (such as the BBC) and the Internet, as well as the emergence of the United States as a global superpower, Modern English has become the international language of business, science, communication, sports, aviation, and diplomacy.

Literature[edit]

Geoffrey Chaucer (; c. 1340s – 25 October 1400) was an English poet and author. Widely seen as the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages, he is best known for The Canterbury Tales.

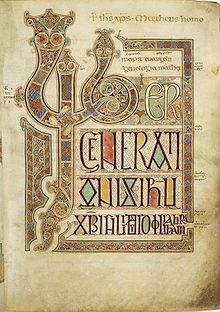

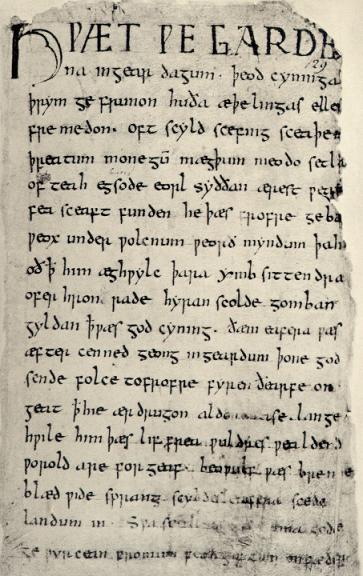

English literature begins with Anglo-Saxon literature, which was written in Old English and produced epic works such as Beowulf and the fragmentary The Battle of Maldon, The Seafarer and The Wanderer. For many years, Latin and French were the preferred literary languages of England, but in the medieval period there was a flourishing of literature in Middle English; Geoffrey Chaucer is the most famous writer of this period.

The Elizabethan era is sometimes described as the golden age of English literature with writers such as William Shakespeare, Thomas Nashe, Edmund Spenser, Sir Philip Sidney, Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson.

Other famous English writers include Jane Austen, Arnold Bennett, Rupert Brooke, Agatha Christie, Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy, A. E. Housman, George Orwell and the Lake Poets.

Due to the expansion of English into a world language during the British Empire, literature is now written in English across the world.[citation needed]

In 2003 the BBC carried out a UK survey entitled The Big Read in order to find the «nation’s best-loved novel» of all time, with works by English novelists J. R. R. Tolkien, Jane Austen, Philip Pullman, Douglas Adams and J. K. Rowling making up the top five on the list.[151]

See also[edit]

- English diaspora

- British people

- List of English people

- Old English (Ireland)

- Celtic peoples

- Culture of England

- English art

- Architecture of England

- English folklore

- English nationalism

- Manx people

- Genetic history of Europe

- European ethnic groups

- Immigration to the United Kingdom (1922-present day)

- Population of England (historical estimates)

- 100% English (Channel 4 TV programme, 2006)

- Social history of the United Kingdom (1945–present)

- White British

Language:

- Anglicisation

- English language

- English-speaking world

- Old English

- Middle English

- Early Modern English

- Cumbric language

- Cornish language

- Brythonic language

Diaspora:

- British diaspora in Africa

- Anglo-Burmese

- Metis people

- Anglo-Indian

- Anglo-Irish

- Anglo-Scot

- English American

- English Argentine

- English Australian

- English Brazilian

- English Chilean

- English Canadian

- New Zealand European

Notes[edit]

- ^ Different spellings of this king’s name most commonly found in modern texts are «Ethelred» and «Æthelred» (or «Aethelred»), the latter being closer to the original Old English form Æþelræd.

- ^ American Community Survey.

- ^ Those who self-identified as English ethnic group

- ^ 210915 listed their birthplace as England.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Ethnicity and National Identity in England and Wales». www.ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. 11 December 2012. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

The 2011 England and Wales census reports that in England and Wales 32.4 million people associated themselves with an English identity alone and 37.6 million identified themselves with an English identity either on its own or combined with other identities, being 57.7% and 67.1% respectively of the population of England and Wales.

- ^ «Table B04006 — People Reporting Ancestry — 2020 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates». United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ «2021 Australia, Census All persons QuickStats | Australian Bureau of Statistics».

- ^ «Census Profile, 2016 Census». Statistics Canada. 8 February 2017. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ Census 2011: Census in brief (PDF). Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. 2012. p. 26. ISBN 9780621413885. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2015. The number of people who described themselves as white in terms of population group and specified their first language as English in South Africa’s 2011 Census was 1,603,575. The total white population with a first language specified was 4,461,409 and the total population was 51,770,560.

- ^ «2018 Census population and dwelling counts». Stats NZ. 23 September 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Chavez, Lydia (23 June 1985). «Fare of the country; Teatime: A bit of Britain in Argentina». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- ^ Cole, Jeffrey (2011). Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-302-6. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ «English». Online Etymology Dictionary. Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ a b Leslie, Stephen; Winney, Bruce; Hellenthal, Garrett; Davison, Dan; Boumertit, Abdelhamid; Day, Tammy; Hutnik, Katarzyna; Royrvik, Ellen C.; Cunliffe, Barry; Lawson, Daniel J.; Falush, Daniel; Freeman, Colin; Pirinen, Matti; Myers, Simon; Robinson, Mark; Donnelly, Peter; Bodmer, Walter (19 March 2015). «The fine scale genetic structure of the British population». Nature. 519 (7543): 309–314. Bibcode:2015Natur.519..309.. doi:10.1038/nature14230. PMC 4632200. PMID 25788095.

- ^ Schiffels, Stephan; Haak, Wolfgang; Paajanen, Pirita; Llamas, Bastien; Popescu, Elizabeth; Loe, Louise; Clarke, Rachel; Lyons, Alice; Mortimer, Richard; Sayer, Duncan; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Cooper, Alan; Durbin, Richard (19 January 2016). «Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon genomes from East England reveal British migration history». Nature Communications. 7: 10408. Bibcode:2016NatCo…710408S. doi:10.1038/ncomms10408. PMC 4735688. PMID 26783965.

- ^ a b Martiniano, R., Caffell, A., Holst, M. et al. Genomic signals of migration and continuity in Britain before the Anglo-Saxons. Nat Commun 7, 10326 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10326 Archived 21 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Michael E. Weale, Deborah A. Weiss, Rolf F. Jager, Neil Bradman, Mark G. Thomas, Y Chromosome Evidence for Anglo-Saxon Mass Migration, Molecular Biology and Evolution, Volume 19, Issue 7, July 2002, Pages 1008–1021, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004160 Archived 21 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Brix, Lise (20 February 2017). «New study reignites debate over Viking settlements in England». sciencenordic.com (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ Kershaw, Jane; Røyrvik, Ellen C. (December 2016). «The ‘People of the British Isles’ project and Viking settlement in England». Antiquity. 90 (354): 1670–1680. doi:10.15184/aqy.2016.193. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 52266574.

- ^ Campbell. The Anglo-Saxon State. p. 10

- ^ Ward-Perkins, Bryan (2000). «Why did the Anglo-Saxons not become more British?». The English Historical Review. 115 (462): 513–33. doi:10.1093/ehr/115.462.513.

- ^ Hills, C. (2003) Origins of the English Duckworth, London. ISBN 0-7156-3191-8, p. 67

- ^ Higham, Nicholas J., and Martin J. Ryan. The Anglo-Saxon World. Yale University Press, 2013. pp. 7–19

- ^ «Chambers – Search Chambers». Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

the citizens or inhabitants of, or people born in, England, considered as a group

- ^ «Act of Union 1707». parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 21 September 2010. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ Kumar 2003, pp. 262–290.

- ^ Kumar 2003, pp. 1–18.

- ^ «English nationalism ‘threat to UK’«. BBC. 9 January 2000. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021.

- ^ «The English question Handle with care». The Economist. 1 November 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2008.

- ^ Condor, Gibson & Abell 2006.

- ^ Frith, Maxine (8 January 2004). «Ethnic minorities feel strong sense of identity with Britain, report reveals». The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011.

- ^ Hussain, Asifa; Millar, William Lockley (2006). Multicultural Nationalism. Oxford University Press. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0-19-928071-1. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Campbell, Dennis (18 June 2006). «Asian recruits boost England fan army». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016.

- ^ «National Identity and Community in England» (2006) Institute of Governance Briefing No.7. [1] Archived 15 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «78 per cent of Bangladeshis said they were British, while only 5 per cent said they were English, Scottish or Welsh», and the largest percentage of non-whites to identify as English were the people who described their ethnicity as «Mixed» (37%).’Identity’, National Statistics, 21 February 2006

- ^ Kumar 2003, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Taylor, A. J. P. (1965, English History, 1914–1945 Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. v

- ^ Davies, Norman (1999). The Isles: A History. Macmillan Publishing. ISBN 978-0333692837.[page needed]

- ^ Parris, Matthew (18 December 2010). «With a shrug of the shoulders, England is becoming a nation once again». The Spectator.

- ^ a b Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fu, Qiaomei (11 June 2015). «Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe». Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- ^ Curry, Andrew (August 2019). «The first Europeans weren’t who you might think». National Geographic.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (21 February 2017). «Thousands of horsemen may have swept into Bronze Age Europe, transforming the local population». Science.

- ^ a b Novembre, John; Johnson, Toby; Bryc, Katarzyna; Kutalik, Zoltán; Boyko, Adam R.; Auton, Adam; Indap, Amit; King, Karen S.; Bergmann, Sven; Nelson, Matthew R.; Stephens, Matthew; Bustamante, Carlos D. (2008). «Genes mirror geography within Europe». Nature. 456 (7218): 98–101. Bibcode:2008Natur.456…98N. doi:10.1038/nature07331. PMC 2735096. PMID 18758442.

- ^ «Dutch Beakers: Like no other Beakers». 19 January 2019. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (21 February 2018). «Ancient Britons ‘replaced’ by newcomers». BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 March 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ Athanasiadis, G.; Cheng, J. Y.; Vilhjalmsson, B. J.; Jorgensen, F. G.; Als, T. D.; Le Hellard, S.; Espeseth, T.; Sullivan, P. F.; Hultman, C. M.; Kjaergaard, P. C.; Schierup, M. H.; Mailund, T. (2016). «Nationwide Genomic Study in Denmark Reveals Remarkable Population Homogeneity». Genetics. 204 (2): 711–722. doi:10.1534/genetics.116.189241. PMC 5068857. PMID 27535931.

- ^ Weale, Michael E.; Weiss, Deborah A.; Jager, Rolf F.; Bradman, Neil; Thomas, Mark G. (1 July 2002). «Y Chromosome Evidence for Anglo-Saxon Mass Migration». Molecular Biology and Evolution. 19 (7): 1008–1021. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004160. PMID 12082121. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020 – via academic.oup.com.

- ^ «A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Stephen (2006). The Origins of the British: A Genetic Detective Story. London: Constable and Robinson. ISBN 978-1-84529-158-7.

- ^ Schiffels, S. et al. (2016) Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon genomes from East England reveal British migration history Archived 17 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Nature Communications 7, Article number:10408 doi:10.1038/ncomms10408

- ^ Ross P. Byrne, Rui Martiniano, Lara M. Cassidy, Matthew Carrigan, Garrett Hellenthal, Orla Hardiman, Daniel G. Bradley, Russell McLaughlin: «Insular Celtic population structure and genomic footprints of migration» (2018)

- ^ Margaryan, A., Lawson, D.J., Sikora, M. et al. Population genomics of the Viking world. Nature 585, 390–396 (2020) See Supplementary Note 11 in particular

- ^ Gretzinger; Sayer; Justeau; et al. (21 September 2022). «The Anglo-Saxon migration and the formation of the early English gene pool». Nature. 610 (7930): 112–119. Bibcode:2022Natur.610..112G. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05247-2. PMC 9534755. PMID 36131019.

- ^ The archaeology of black Britain Archived 24 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Channel 4. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ Eva Botkin-Kowacki, ‘Where did the British come from? Ancient DNA holds clues. Archived 15 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine’ (20/01/16), The Christian Science Monitor

- ^ Wise, Gildas the (1899). «The Ruin of Britain». Tertullian.org. pp. 4–252. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ celtpn Archived 6 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine However the names of some towns, cities, rivers etc. do have Brittonic or pre-Brittonic origins, becoming more frequent towards the west of Britain.

- ^ «Britain BC: Life in Britain and Ireland before the Romans» by Francis Pryor, p. 122. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-00-712693-X.

- ^ Ward-Perkins, Bryan. «Why did the Anglo-Saxons not become more British?.» The English Historical Review 115.462 (2000): page 523

- ^ Higham, Nicholas J. and Ryan, Martin J. «The Anglo-Saxon World» (Yale University Press, 2013)

- ^ Ward-Perkins, Bryan. «Why did the Anglo-Saxons not become more British?.» The English Historical Review 115.462 (2000): 513–533.

- ^ Ingham, Richard (19 July 2006). «Anglo-Saxons wanted genetic supremacy». Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Todd, Malcolm. «Anglo-Saxon Origins: The Reality of the Myth» Archived 24 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, in Cameron, Keith. «The nation: myth or reality?». Intellect Books, 1994. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ Stefan Burmeister, Archaeology and Migration (2000): » … immigration in the nucleus of the Anglo-Saxon settlement does not seem aptly described in terms of the ‘elite-dominance model.’ To all appearances, the settlement was carried out by small, agriculture-oriented kinship groups. This process corresponds more closely to a classic settler model. The absence of early evidence of a socially demarcated elite underscores the supposition that such an elite did not play a substantial role. Rich burials such as are well known from Denmark have no counterparts in England until the 6th century. At best, the elite-dominance model might apply in the peripheral areas of the settlement territory, where an immigration predominantly comprised of men and the existence of hybrid cultural forms might support it.»

- ^ Dark, Ken R. (2003). «Large-scale population movements into and from Britain south of Hadrian’s Wall in the fourth to sixth centuries AD» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Toby F. Martin, The Cruciform Brooch and Anglo-Saxon England, Boydell and Brewer Press (2015), pp. 174-178

- ^ Catherine Hills, «The Anglo-Saxon Migration: An Archaeological Case Study of Disruption,» in Migrations and Disruptions, ed. Brenda J. Baker and Takeyuki Tsuda, pp. 45-48

- ^ Coates, Richard. «Celtic whispers: revisiting the problems of the relation between Brittonic and Old English». Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Härke, Heinrich. «Anglo-Saxon Immigration and Ethnogenesis.» Medieval Archaeology 55.1 (2011): 1–28.

- ^ Kortlandt, Frederik (2018). «Relative Chronology» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Fox, Bethany. «The P-Celtic Place Names of North-East England and South-East Scotland». Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ The Age of Athelstan by Paul Hill (2004), Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-2566-8

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary Archived 4 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine by Douglas Harper (2001), List of sources used Archived 8 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 July 2006.

- ^ The Adventure of English, Melvyn Bragg, 2003. p. 22.

- ^ «Athelstan (c.895–939): Historic Figures». Bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 February 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2006.

- ^ The Battle of Brunanburh, 937AD Archived 11 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine by h2g2, BBC website. Retrieved 30 October 2006.

- ^ A. L. Rowse, The Story of Britain, Artus 1979 ISBN 0-297-83311-1

- ^ OED, 2nd edition, s.v. ‘English’.

- ^ «England—Plantagenet Kings». Heritage History. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010.

- ^ «BBC — History — British History in depth: The Ages of English». BBC. Archived from the original on 26 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ OED, s.v. ‘Englishry’.

- ^ «Liberation of Ireland». Iol.ie. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 23 June 2006.

- ^ A History of Britain: The British Wars 1603–1776 by Simon Schama, BBC Worldwide. ISBN 0-563-53747-7.

- ^ The English, Jeremy Paxman 1998[page needed]

- ^ «EJP — In Depth — On Anglo Jewry». 14 July 2006. Archived from the original on 14 July 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ «Meredith on the Guillet — Thoreau Genealogy». Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- ^ More Britons applying for Irish passports Archived 5 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Owen Bowcott, The Guardian, 13 September 2006. Retrieved 9 January 2006.

- ^ a b Black Presence Archived 24 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Asian and Black History in Britain, 1500–1850: UK government website. Retrieved 21 July 2006.

- ^ Fisher, Michael Herbert (2006), Counterflows to Colonialism: Indian Traveller and Settler in Britain 1600–1857, Orient Blackswan, pp. 111–9, 129–30, 140, 154–6, 160–8, 172, 181, ISBN 978-81-7824-154-8

- ^ Postwar immigration Archived 22 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine The National Archives Accessed October 2006

- ^ «Ethnic minorities more likely to feel British than white people, says research». Evening Standard. 18 February 2007. Archived from the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ «English identity open to all, regardless of race, finds poll – and Three Lions is the symbol that unites us». British Future. 9 June 2021. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Alexander, Inigo (30 June 2019). «Now 90% of England agrees: being English is not about colour». The Observer. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ a b «British identity: Waning». The Economist. 25 January 2007. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ «When British isn’t always best». The Guardian. London. 24 January 2007. Archived from the original on 23 December 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ Jones, Richard Wyn; Lodge, Guy; Jeffery, Charlie; Gottfried, Glenn; Scully, Roger; Henderson, Ailsa; Wincott, Daniel (July 2013). England and its Two Unions: The Anatomy of a Nation and its Discontents (PDF). Institute for Public Policy Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Kenny, M (2014). The politics of English Nationhood. Oxford University Press. pp. 192–193. ISBN 978-0198778721.

- ^ Kumar 2003, p. 262.

- ^ Hoyle, Ben (8 June 2006). «St George unfurls his flag (made in China) once again». The Times. London. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ^ «The West Lothian Question». BBC News. 1 June 1998. Archived from the original on 26 January 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ «Fresh call for English Parliament». BBC News. 24 October 2006. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ «Welsh nod for English Parliament». BBC News. 20 December 2006. Archived from the original on 10 August 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ Paul Johnson is quoted by Kumar (Kumar 2003, p. 266)

- ^ Curtice, John (February 2010). «Is an English backlash emerging? Reactions to devolution ten years on» (PDF). Institute for Public Policy Research. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Kenny, Michael; English, Richard; Hayton, Richard (February 2008). «Beyond the constitution? Englishness in a post-devolved Britain». Institute for Public Policy Research. p. 3. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Condor, Gibson & Abell 2006, p. 128.

- ^ Hazell, Robert (2006). «The English Question». Publius. 36 (1): 37–56. doi:10.1093/publius/pjj012.

- ^ Ormston, Rachel; Curtice, John (December 2010). «Resentment or contentment? Attitudes towards the Union ten years on» (PDF). National Centre for Social Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ «‘Most’ support English parliament». BBC. 16 January 2007. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ Kumar 2010, p. 484.

- ^ Copus, Colin (2009). «English national parties in post-devolution UK». British Politics. 4 (3): 363–385. doi:10.1057/bp.2009.12. S2CID 153712090.

- ^ «Full England scoreboard». Election 2010. BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 February 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ Kumar 2010, p. 478.

- ^ a b Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia Archived 7 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine — Ancestry 2016

- ^ a b Census Profile, 2016 Census Archived 19 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine — Ethnic origin population

- ^ a b Focus on Geography Series Archived 21 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine — 2016 Census

- ^ 2011 Census for Scotland Standard Outputs Archived 12 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Accessed 5 September 2014

- ^ a b SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES more information Archived 27 December 1996 at the Wayback Machine — 2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates

- ^ «2018 Census totals by topic» (Microsoft Excel spreadsheet). Statistics New Zealand. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ Scotland’s Census 2001: Supporting Information (PDF; see p. 43) Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Scottish Census Results Online Browser. Retrieved 16 November 2007. Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Key Statistics Report, p. 10. Archived 27 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Country of Birth: Proportion Born in Wales Falling Archived 24 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, National Statistics, 8 January 2004.

- ^ «Table 19 Enumerated population classified by usual residence and sex» (PDF). Webcitation.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2009. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ An examination of the English ancestry of George Washington, setting forth the evidence to connect him with the Washingtons of Sulgrave and Brington. Boston, Printed for the New England historic genealogical society. 1889. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sharing the Dream: White Males in a Multicultural America Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine By Dominic J. Pulera.

- ^ Reynolds Farley, ‘The New Census Question about Ancestry: What Did It Tell Us?’, Demography, Vol. 28, No. 3 (August 1991), pp. 414, 421.

- ^ Stanley Lieberson and Lawrence Santi, ‘The Use of Nativity Data to Estimate Ethnic Characteristics and Patterns’, Social Science Research, Vol. 14, No. 1 (1985), pp. 44-6.

- ^ Stanley Lieberson and Mary C. Waters, ‘Ethnic Groups in Flux: The Changing Ethnic Responses of American Whites’, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 487, No. 79 (September 1986), pp. 82-86.

- ^ Mary C. Waters, Ethnic Options: Choosing Identities in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), p. 36.

- ^ US Census 2000 data Archived 18 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, table PHC-T-43.

- ^ «1990 Census of Population Detailed Ancestry Groups for States» (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 18 September 1992. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 July 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ «Table 2: Persons Who Reported at Least One Specific Ancestry Group for the United States: 1980» (PDF). 1980 United States Census. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ From many strands: ethnic and racial groups in contemporary América Archived 10 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine by Stanley Lieberson

- ^ «Ethnic Origin». 2001 Census. Statistics Canada. 4 November 2002. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ According to Canada’s Ethnocultural Mosaic, 2006 Census Archived 25 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, (p. 7) «…the presence of the Canadian example has led to an increase in Canadian being reported and has had an impact on the counts of other groups, especially for French, English, Irish and Scottish. People who previously reported these origins in the census had the tendency to now report Canadian.»

- ^ Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of (3 June 2003). «Chapter — Population characteristics: Ancestry of Australia’s population». Abs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ J. Jupp, The English in Australia, Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 103

- ^ «Census 2016: Summary of result – Population by states and territories, 2011 and 2016 Census». Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ «English — Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand». 20 September 2008. Archived from the original on 20 September 2008.

- ^ a b Bueltmann, Tanja; Gleeson, David T.; MacRaild, Donald M. (2010). Locating the English Diaspora 1500-2010. ISBN 9781846318191. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ «Birthplace (detailed) For the census usually resident population count 2001, 2006, and 2013 Censuses Table 11» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ «Emigration of Scots, English and Welsh-speaking people to Argentina in the nineteenth century». British Settlers in Argentina—studies in 19th and 20th century emigration. Archived from the original on 30 January 2008. Retrieved 8 January 2008.

- ^ Carr, Raymond (2003). «The invention of Great Britain: A review of The Making of English Identity by Krishnan Kumar». The Spectator. UK. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011.

- ^ Gledhill, Ruth (15 February 2007). «Catholics set to pass Anglicans as leading UK church». The Times. London. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ «How many Catholics are there in Britain?». BBC. London. 15 September 2010. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ «2009 Church Statistics» (PDF). Church of England. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ See the pages linked from «Life Events». Church of England. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2018..

- ^ Bowler, Peter J. (2001). Reconciling science and religion: the debate in early-twentieth-century Britain. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 194..

- ^ «Facts and Stats». Church of England. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ «Research and Statistics». Church of England. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012..

- ^ «Understanding the 21st Century Catholic Community» (PDF). CAFOD, Ipsos MORI. November 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ Pocklington, David (24 April 2019). «St George’s Day: Church and State». Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ Wolfgang Vierick (1964), Der English Dialect Survey und der Linguistic Survey of Scotland — Arbeitsmethoden und bisherige Ergebnisse, Zeitschrift für Mundartforschung 31, 333-335 in Shorrocks, Graham (1999). A Grammar of the Dialect of the Bolton Area, Part 1. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. p. 58. ISBN 3-631-33066-9.

- ^ «The Big Read — Top 100 Books». BBC. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

Sources[edit]

- «Expert Links: English Family History and Genealogy». Price and Associates: Professional Genealogy and Family History Services. Archived from the original on 10 December 2012.

- Condor, Susan; Gibson, Stephen; Abell, Jackie (2006). «English identity and ethnic diversity in the context of UK constitutional change» (PDF). Ethnicities. 6 (2): 123–158. doi:10.1177/1468796806063748. S2CID 145498328. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2011.

- Fox, Kate (2004). Watching the English. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-81886-2.

- Kumar, Krishan (2003). The Making of English National Identity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77736-0.

- Kumar, Krishan (2010). «Negotiating English identity: Englishness, Britishness and the future of the United Kingdom». Nations and Nationalism. 16 (3): 469–487. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8129.2010.00442.x.

- Paxman, Jeremy (1999). The English. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-14-026723-5.

- Young, Robert J.C. (2008). The Idea of English Ethnicity. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4051-0129-5.

- Diaspora

- Bueltmann, Tanja; Gleeson, David T.; MacRaild, Donald M., eds. (2012). Locating the English Diaspora, 1500–2010. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 9781781387061.

External links[edit]

Quotations related to English people at Wikiquote

The English people (from the adjective in _an. Englisc) are a nation and ethnic group native to England who predominantly speak English. The English identity as a people is of early origin, when they were known in Old English as the «Anglecynn». The largest single population of English people reside in England, a constituent country of the United Kingdom. They are believed to be a mixture of different groups that have settled in what became England, such as the Brythons (including Romano-Britons), Anglo-Saxons, Danish Vikings, BretonsBrittany and the Angevins: Province and Empire, 1158-1203 [http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=NmXW4heYJGAC&pg=PA11&lpg=PA11&dq=bretons+southern+england+normans&source=web&ots=56IbqcCQvT&sig=6lAlnfoKh3gAngFXMRhuUR3nU4g&hl=en] ] , and Normans. More recent migrations to England include peoples from a variety of different regions of Great Britain and Ireland and many other countries, mostly from Wales, Scotland, Ireland, and Commonwealth countries. Some of these more recent migrants have assumed a solely British or English identity, and others have developed dual or hyphenated identities. [«Ethnic minorities feel strong sense of identity with Britain, report reveals» Maxine Frith «The Independent» 8 January 2004. [http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/this-britain/ethnic-minorities-feel-strong-sense-of-identity-with-britain-report-reveals-578503.html] ] [Hussain, Asifa and Millar, William Lockley (2006) «Multicultural Nationalism» Oxford university Press p149-150 [http://books.google.com/books?id=d2Hv2QMMVrQC&pg=PA149&lpg=PA149&dq=English+identity+Pakistani+British&source=web&ots=vK18u7nyNp&sig=mbDfLkCfSSRAXuOIyKbDnTcadJs&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=9&ct=result] ] [CONDOR Susan; GIBSON Stephen; ABELL Jackie. (2006) «English identity and ethnic diversity in the context of UK constitutional change» «Ethnicities» 6:123-158 [http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=17946417 abstract] ] [«Asian recruits boost England fan army» by Dennis Campbell, «Te Guardian» 18 June 2006. [http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2006/jun/18/worldcup2006.sport] ] [«National Identity and Community in England» (2006) «Institute of Governance» Briefing No.7. [http://www.institute-of-governance.org/forum/Leverhulme/briefing_pdfs/IoG_Briefing_07.pdf] ]

Definitions

Writing about the English people may be complicated because England has historically been settled by waves of invaders and immigrants at different periods in history, and has also spread its influence, and its populace, worldwide. Hence, the term can refer to the English ethnic group that shares a belief in their common descent from a mass migration of Germanic peoples (usually referred to as Anglo-Saxons) during the sub-Roman period. Historian Catherine Hills describes what she calls the «national origin myth» of the English::The arrival of the Anglo-Saxons … is still perceived as an important and interesting event because it is believed to have been a key factor in the identity of the present inhabitants of the British Isles, involving migration on such a scale as to permanently change the population of south-east Britain, and making the English a distinct and different people from the Celtic Irish, Welsh and Scots…..this is an example of a national origin myth… and shows why there are seldom simple answers to questions about origins. [Hills, Catherine (2003) «The Origins of the English» p. 18. Duckworth Debates in Archaeology. Duckworth. London. ISBN 0 7156 3191 8]

English people can be viewed in a variety of different ways, but the broadest concept comprises anyone who considers themselves English and are considered English by most other people.

English nationality

Although there is no longer any official definition of English nationality, the term «the English people» can be used to discuss the English as a «nation», using the «OED»‘s definition of «nation» as a group united by factors that include «language, culture, history, or occupation of the same territory», rather than ancestral ties alone. [«Nation», sense 1. «The Oxford English Dictionary», 2nd edtn., 1989′.]

The concept of an ‘English nation’ is older than that of the ‘British nation’ and the 1990s witnessed a revival in English self-consciousness.Krishan Kumar, «The Rise of English National Identity» (Cambridge University Press, 1997), pp. 262-290.] This is linked to the expressions of national self-awareness of the other British nations of Wales and Scotland — which take their most solid form in the new devolved political arrangements within the United Kingdom — and the waning of a shared British national identity as the British Empire fades into history. [ [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/uk/596703.stm English nationalism ‘threat to UK’] , BBC, Sunday, 9 January, 2000] [ [http://www.economist.com/world/britain/displaystory.cfm?story_id=10064563 The English question Handle with care] , the Economist 1 November 2007] Krishan Kumar. [http://assets.cambridge.org/97805217/71887/sample/9780521771887ws.pdf The Making of English National Identity] , Cambridge University Press, 2003]

While expressions of English national identity can involve beliefs in common descent, most political English nationalists do not consider Englishness to be a form of kinship. For example, the English Democrats Party states that «We do not claim Englishness to be purely ethnic or purely cultural, but it is a complex mix of the two. We firmly believe Englishness is a state of mind», [ [http://www.englishdemocrats.org.uk/faq.php English Democrats FAQ] ] while the Campaign for an English Parliament says, «The people of England includes everyone who considers this ancient land to be their home and future regardless of ethnicity, race, religion or culture». [ [http://www.thecep.org.uk/introduction.shtml ‘Introduction’, «The Campaign for an English Parliament»] ] In an article for «The Guardian», novelist Andrea Levy (born in London to Jamaican parents) calls England a separate country «without any doubt» and asserts that she is «English. Born and bred, as the saying goes. (As far as I can remember, it is born and bred and not born-and-bred-with-a-very-long-line-of-white-ancestors-directly-descended-from-Anglo-Saxons.)» Arguing that «England has never been an exclusive club, but rather a hybrid nation», she writes that «Englishness must never be allowed to attach itself to ethnicity. The majority of English people are white, but some are not … Let England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland be nations that are plural and inclusive.» [Andrea Levy, [http://books.guardian.co.uk/departments/politicsphilosophyandsociety/story/0,6000,138282,00.html «This is my England»] , «The Guardian», February 19, 2000.]

However, this use of the word «English» is complicated by the fact that most non-white people in England identify as British rather than English. In their 2004 Annual Population Survey, the Office of National Statistics compared the «ethnic» identities of British people with their perceived «national» identity. They found that while 58% of white people described their nationality as «English», the vast majority of non-white people called themselves «British». For example, «78 per cent of Bangladeshis said they were British, while only 5 per cent said they were English, Scottish or Welsh», and the largest percentage of non-whites to identify as English were the people who described their ethnicity as «Mixed» (37%). [ [http://www.statistics.gov.uk/cci/nugget.asp?id=459 ‘Identity’, «National Statistics», 21 Feb, 2006] ]

English origins

It is difficult to clearly define the origins of the English people, owing to the close interactions between the English and their neighbours in the British Isles, and the waves of immigration that have added to England’s population at different periods. The conventional view of English origins is that the English are primarily descended from the Anglo-Saxons and other Germanic tribes that migrated to Great Britain following the end of the Roman occupation of Britain, with assimilation of later migrants such as the Vikings and Normans. This version of history is considered by some historians and geneticists as simplistic or even incorrect (see below). However, the notion of the Anglo-Saxon English has traditionally been important in defining English identity and distinguishing the English from their Celtic neighbours, such as the Scots, Welsh and Irish. Furthermore, the idea of an English Anglo-Saxon origin is important to those who see differences between people with long-standing English ancestry and people whose ancestors arrived much more recently, an attitude expressed succinctly by a character in Sarah Kane’s play «Blasted» who boasts «I’m not an import», contrasting himself with the children of immigrants: «they have their kids, call them English, they’re not English, born in England don’t make you English». [Sarah Kane, «Complete Plays» (19**), p. 41.]