Concepts are defined as abstract ideas. They are understood to be the fundamental building blocks underlying principles, thoughts and beliefs.[1]

They play an important role in all aspects of cognition.[2][3] As such, concepts are studied by several disciplines, such as linguistics, psychology, and philosophy, and these disciplines are interested in the logical and psychological structure of concepts, and how they are put together to form thoughts and sentences. The study of concepts has served as an important flagship of an emerging interdisciplinary approach called cognitive science.[4]

In contemporary philosophy, there are at least three prevailing ways to understand what a concept is:[5]

- Concepts as mental representations, where concepts are entities that exist in the mind (mental objects)

- Concepts as abilities, where concepts are abilities peculiar to cognitive agents (mental states)

- Concepts as Fregean senses, where concepts are abstract objects, as opposed to mental objects and mental states

Concepts can be organized into a hierarchy, higher levels of which are termed «superordinate» and lower levels termed «subordinate». Additionally, there is the «basic» or «middle» level at which people will most readily categorize a concept.[6] For example, a basic-level concept would be «chair», with its superordinate, «furniture», and its subordinate, «easy chair».

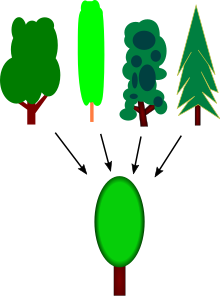

A representation of the concept of a tree. The four upper images of trees can be roughly quantified into an overall generalization of the idea of a tree, pictured in the lower image.

Concepts may be exact, or inexact.[7]

When the mind makes a generalization such as the concept of tree, it extracts similarities from numerous examples; the simplification enables higher-level thinking.

A concept is instantiated (reified) by all of its actual or potential instances, whether these are things in the real world or other ideas.

Concepts are studied as components of human cognition in the cognitive science disciplines of linguistics, psychology, and philosophy, where an ongoing debate asks whether all cognition must occur through concepts. Concepts are regularly formalized in mathematics, computer science, databases and artificial intelligence. Examples of specific high-level conceptual classes in these fields include classes, schema or categories. In informal use the word concept often just means any idea.

Ontology of concepts[edit]

A central question in the study of concepts is the question of what they are. Philosophers construe this question as one about the ontology of concepts—what kind of things they are. The ontology of concepts determines the answer to other questions, such as how to integrate concepts into a wider theory of the mind, what functions are allowed or disallowed by a concept’s ontology, etc. There are two main views of the ontology of concepts: (1) Concepts are abstract objects, and (2) concepts are mental representations.[8]

Concepts as mental representations[edit]

The psychological view of concepts[edit]

Within the framework of the representational theory of mind, the structural position of concepts can be understood as follows: Concepts serve as the building blocks of what are called mental representations (colloquially understood as ideas in the mind). Mental representations, in turn, are the building blocks of what are called propositional attitudes (colloquially understood as the stances or perspectives we take towards ideas, be it «believing», «doubting», «wondering», «accepting», etc.). And these propositional attitudes, in turn, are the building blocks of our understanding of thoughts that populate everyday life, as well as folk psychology. In this way, we have an analysis that ties our common everyday understanding of thoughts down to the scientific and philosophical understanding of concepts.[9]

The physicalist view of concepts[edit]

In a physicalist theory of mind, a concept is a mental representation, which the brain uses to denote a class of things in the world. This is to say that it is literally, a symbol or group of symbols together made from the physical material of the brain.[10][11] Concepts are mental representations that allow us to draw appropriate inferences about the type of entities we encounter in our everyday lives.[11] Concepts do not encompass all mental representations, but are merely a subset of them.[10] The use of concepts is necessary to cognitive processes such as categorization, memory, decision making, learning, and inference.[12]

Concepts are thought to be stored in long term cortical memory,[13] in contrast to episodic memory of the particular objects and events which they abstract, which are stored in hippocampus. Evidence for this separation comes from hippocampal damaged patients such as patient HM. The abstraction from the day’s hippocampal events and objects into cortical concepts is often considered to be the computation underlying (some stages of) sleep and dreaming. Many people (beginning with Aristotle) report memories of dreams which appear to mix the day’s events with analogous or related historical concepts and memories, and suggest that they were being sorted or organized into more abstract concepts. («Sort» is itself another word for concept, and «sorting» thus means to organize into concepts.)

Concepts as abstract objects[edit]

The semantic view of concepts suggests that concepts are abstract objects. In this view, concepts are abstract objects of a category out of a human’s mind rather than some mental representations.[8]

There is debate as to the relationship between concepts and natural language.[5] However, it is necessary at least to begin by understanding that the concept «dog» is philosophically distinct from the things in the world grouped by this concept—or the reference class or extension.[10] Concepts that can be equated to a single word are called «lexical concepts».[5]

The study of concepts and conceptual structure falls into the disciplines of linguistics, philosophy, psychology, and cognitive science.[11]

In the simplest terms, a concept is a name or label that regards or treats an abstraction as if it had concrete or material existence, such as a person, a place, or a thing. It may represent a natural object that exists in the real world like a tree, an animal, a stone, etc. It may also name an artificial (man-made) object like a chair, computer, house, etc. Abstract ideas and knowledge domains such as freedom, equality, science, happiness, etc., are also symbolized by concepts. It is important to realize that a concept is merely a symbol, a representation of the abstraction. The word is not to be mistaken for the thing. For example, the word «moon» (a concept) is not the large, bright, shape-changing object up in the sky, but only represents that celestial object. Concepts are created (named) to describe, explain and capture reality as it is known and understood.

A priori concepts[edit]

Kant maintained the view that human minds possess pure or a priori concepts. Instead of being abstracted from individual perceptions, like empirical concepts, they originate in the mind itself. He called these concepts categories, in the sense of the word that means predicate, attribute, characteristic, or quality. But these pure categories are predicates of things in general, not of a particular thing. According to Kant, there are twelve categories that constitute the understanding of phenomenal objects. Each category is that one predicate which is common to multiple empirical concepts. In order to explain how an a priori concept can relate to individual phenomena, in a manner analogous to an a posteriori concept, Kant employed the technical concept of the schema. He held that the account of the concept as an abstraction of experience is only partly correct. He called those concepts that result from abstraction «a posteriori concepts» (meaning concepts that arise out of experience). An empirical or an a posteriori concept is a general representation (Vorstellung) or non-specific thought of that which is common to several specific perceived objects (Logic, I, 1., §1, Note 1)

A concept is a common feature or characteristic. Kant investigated the way that empirical a posteriori concepts are created.

The logical acts of the understanding by which concepts are generated as to their form are:

- comparison, i.e., the likening of mental images to one another in relation to the unity of consciousness;

- reflection, i.e., the going back over different mental images, how they can be comprehended in one consciousness; and finally

- abstraction or the segregation of everything else by which the mental images differ …

In order to make our mental images into concepts, one must thus be able to compare, reflect, and abstract, for these three logical operations of the understanding are essential and general conditions of generating any concept whatever. For example, I see a fir, a willow, and a linden. In firstly comparing these objects, I notice that they are different from one another in respect of trunk, branches, leaves, and the like; further, however, I reflect only on what they have in common, the trunk, the branches, the leaves themselves, and abstract from their size, shape, and so forth; thus I gain a concept of a tree.

— Logic, §6

Embodied content[edit]

In cognitive linguistics, abstract concepts are transformations of concrete concepts derived from embodied experience. The mechanism of transformation is structural mapping, in which properties of two or more source domains are selectively mapped onto a blended space (Fauconnier & Turner, 1995; see conceptual blending). A common class of blends are metaphors. This theory contrasts with the rationalist view that concepts are perceptions (or recollections, in Plato’s term) of an independently existing world of ideas, in that it denies the existence of any such realm. It also contrasts with the empiricist view that concepts are abstract generalizations of individual experiences, because the contingent and bodily experience is preserved in a concept, and not abstracted away. While the perspective is compatible with Jamesian pragmatism, the notion of the transformation of embodied concepts through structural mapping makes a distinct contribution to the problem of concept formation.[citation needed]

Realist universal concepts[edit]

Platonist views of the mind construe concepts as abstract objects.[14] Plato was the starkest proponent of the realist thesis of universal concepts. By his view, concepts (and ideas in general) are innate ideas that were instantiations of a transcendental world of pure forms that lay behind the veil of the physical world. In this way, universals were explained as transcendent objects. Needless to say, this form of realism was tied deeply with Plato’s ontological projects. This remark on Plato is not of merely historical interest. For example, the view that numbers are Platonic objects was revived by Kurt Gödel as a result of certain puzzles that he took to arise from the phenomenological accounts.[15]

Sense and reference[edit]

Gottlob Frege, founder of the analytic tradition in philosophy, famously argued for the analysis of language in terms of sense and reference. For him, the sense of an expression in language describes a certain state of affairs in the world, namely, the way that some object is presented. Since many commentators view the notion of sense as identical to the notion of concept, and Frege regards senses as the linguistic representations of states of affairs in the world, it seems to follow that we may understand concepts as the manner in which we grasp the world. Accordingly, concepts (as senses) have an ontological status.[8]

Concepts in calculus[edit]

According to Carl Benjamin Boyer, in the introduction to his The History of the Calculus and its Conceptual Development, concepts in calculus do not refer to perceptions. As long as the concepts are useful and mutually compatible, they are accepted on their own. For example, the concepts of the derivative and the integral are not considered to refer to spatial or temporal perceptions of the external world of experience. Neither are they related in any way to mysterious limits in which quantities are on the verge of nascence or evanescence, that is, coming into or going out of existence. The abstract concepts are now considered to be totally autonomous, even though they originated from the process of abstracting or taking away qualities from perceptions until only the common, essential attributes remained.

Notable theories on the structure of concepts[edit]

Classical theory[edit]

The classical theory of concepts, also referred to as the empiricist theory of concepts,[10] is the oldest theory about the structure of concepts (it can be traced back to Aristotle[11]), and was prominently held until the 1970s.[11] The classical theory of concepts says that concepts have a definitional structure.[5] Adequate definitions of the kind required by this theory usually take the form of a list of features. These features must have two important qualities to provide a comprehensive definition.[11] Features entailed by the definition of a concept must be both necessary and sufficient for membership in the class of things covered by a particular concept.[11] A feature is considered necessary if every member of the denoted class has that feature. A feature is considered sufficient if something has all the parts required by the definition.[11] For example, the classic example bachelor is said to be defined by unmarried and man.[5] An entity is a bachelor (by this definition) if and only if it is both unmarried and a man. To check whether something is a member of the class, you compare its qualities to the features in the definition.[10] Another key part of this theory is that it obeys the law of the excluded middle, which means that there are no partial members of a class, you are either in or out.[11]

The classical theory persisted for so long unquestioned because it seemed intuitively correct and has great explanatory power. It can explain how concepts would be acquired, how we use them to categorize and how we use the structure of a concept to determine its referent class.[5] In fact, for many years it was one of the major activities in philosophy—concept analysis.[5] Concept analysis is the act of trying to articulate the necessary and sufficient conditions for the membership in the referent class of a concept.[citation needed] For example, Shoemaker’s classic «Time Without Change» explored whether the concept of the flow of time can include flows where no changes take place, though change is usually taken as a definition of time.[citation needed]

Arguments against the classical theory[edit]

Given that most later theories of concepts were born out of the rejection of some or all of the classical theory,[14] it seems appropriate to give an account of what might be wrong with this theory. In the 20th century, philosophers such as Wittgenstein and Rosch argued against the classical theory. There are six primary arguments[14] summarized as follows:

- It seems that there simply are no definitions—especially those based in sensory primitive concepts.[14]

- It seems as though there can be cases where our ignorance or error about a class means that we either don’t know the definition of a concept, or have incorrect notions about what a definition of a particular concept might entail.[14]

- Quine’s argument against analyticity in Two Dogmas of Empiricism also holds as an argument against definitions.[14]

- Some concepts have fuzzy membership. There are items for which it is vague whether or not they fall into (or out of) a particular referent class. This is not possible in the classical theory as everything has equal and full membership.[14]

- Experiments and research showed that assumptions of well defined concepts and categories might not be correct. Researcher Hampton[16]asked participants to differentiate whether items were in different categories. Hampton did not conclude that items were either clear and absolute members or non-members. Instead, Hampton found that some items were barely considered category members and others that were barely non-members. For example, participants considered sinks as barely members of kitchen utensil category, while sponges were considered barely non-members, with much disagreement among participants of the study. If concepts and categories were very well defined, such cases should be rare. Since then, many researches have discovered borderline members that are not clearly in or out of a category of concept.

- Rosch found typicality effects which cannot be explained by the classical theory of concepts, these sparked the prototype theory.[14] See below.

- Psychological experiments show no evidence for our using concepts as strict definitions.[14]

Prototype theory[edit]

Prototype theory came out of problems with the classical view of conceptual structure.[5] Prototype theory says that concepts specify properties that members of a class tend to possess, rather than must possess.[14] Wittgenstein, Rosch, Mervis, Berlin, Anglin, and Posner are a few of the key proponents and creators of this theory.[14][17] Wittgenstein describes the relationship between members of a class as family resemblances. There are not necessarily any necessary conditions for membership; a dog can still be a dog with only three legs.[11] This view is particularly supported by psychological experimental evidence for prototypicality effects.[11] Participants willingly and consistently rate objects in categories like ‘vegetable’ or ‘furniture’ as more or less typical of that class.[11][17] It seems that our categories are fuzzy psychologically, and so this structure has explanatory power.[11] We can judge an item’s membership of the referent class of a concept by comparing it to the typical member—the most central member of the concept. If it is similar enough in the relevant ways, it will be cognitively admitted as a member of the relevant class of entities.[11] Rosch suggests that every category is represented by a central exemplar which embodies all or the maximum possible number of features of a given category.[11] Lech, Gunturkun, and Suchan explain that categorization involves many areas of the brain. Some of these are: visual association areas, prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, and temporal lobe.

The Prototype perspective is proposed as an alternative view to the Classical approach. While the Classical theory requires an all-or-nothing membership in a group, prototypes allow for more fuzzy boundaries and are characterized by attributes.[18] Lakoff stresses that experience and cognition are critical to the function of language, and Labov’s experiment found that the function that an artifact contributed to what people categorized it as.[18] For example, a container holding mashed potatoes versus tea swayed people toward classifying them as a bowl and a cup, respectively. This experiment also illuminated the optimal dimensions of what the prototype for «cup» is.[18]

Prototypes also deal with the essence of things and to what extent they belong to a category. There have been a number of experiments dealing with questionnaires asking participants to rate something according to the extent to which it belongs to a category.[18] This question is contradictory to the Classical Theory because something is either a member of a category or is not.[18] This type of problem is paralleled in other areas of linguistics such as phonology, with an illogical question such as «is /i/ or /o/ a better vowel?» The Classical approach and Aristotelian categories may be a better descriptor in some cases.[18]

Theory-theory[edit]

Theory-theory is a reaction to the previous two theories and develops them further.[11] This theory postulates that categorization by concepts is something like scientific theorizing.[5] Concepts are not learned in isolation, but rather are learned as a part of our experiences with the world around us.[11] In this sense, concepts’ structure relies on their relationships to other concepts as mandated by a particular mental theory about the state of the world.[14] How this is supposed to work is a little less clear than in the previous two theories, but is still a prominent and notable theory.[14] This is supposed to explain some of the issues of ignorance and error that come up in prototype and classical theories as concepts that are structured around each other seem to account for errors such as whale as a fish (this misconception came from an incorrect theory about what a whale is like, combining with our theory of what a fish is).[14] When we learn that a whale is not a fish, we are recognizing that whales don’t in fact fit the theory we had about what makes something a fish. Theory-theory also postulates that people’s theories about the world are what inform their conceptual knowledge of the world. Therefore, analysing people’s theories can offer insights into their concepts. In this sense, «theory» means an individual’s mental explanation rather than scientific fact. This theory criticizes classical and prototype theory as relying too much on similarities and using them as a sufficient constraint. It suggests that theories or mental understandings contribute more to what has membership to a group rather than weighted similarities, and a cohesive category is formed more by what makes sense to the perceiver. Weights assigned to features have shown to fluctuate and vary depending on context and experimental task demonstrated by Tversky. For this reason, similarities between members may be collateral rather than causal.[19]

Ideasthesia[edit]

According to the theory of ideasthesia (or «sensing concepts»), activation of a concept may be the main mechanism responsible for the creation of phenomenal experiences. Therefore, understanding how the brain processes concepts may be central to solving the mystery of how conscious experiences (or qualia) emerge within a physical system e.g., the sourness of the sour taste of lemon.[20] This question is also known as the hard problem of consciousness.[21][22] Research on ideasthesia emerged from research on synesthesia where it was noted that a synesthetic experience requires first an activation of a concept of the inducer.[23] Later research expanded these results into everyday perception.[24]

There is a lot of discussion on the most effective theory in concepts. Another theory is semantic pointers, which use perceptual and motor representations and these representations are like symbols.[25]

Etymology[edit]

The term «concept» is traced back to 1554–60 (Latin conceptum – «something conceived»).[26]

See also[edit]

- Abstraction

- Categorization

- Class (philosophy)

- Conceptualism

- Concept and object

- Concept map

- Conceptual blending

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual history

- Conceptual model

- Conversation theory

- Definitionism

- Formal concept analysis

- Fuzzy concept

- Hypostatic abstraction

- Idea

- Ideasthesia

- Noesis

- Notion (philosophy)

- Object (philosophy)

- Process of concept formation

- Schema (Kant)

- Intuitive statistics

References[edit]

- ^ Goguen, Joseph (2005). «What is a Concept?». Conceptual Structures: Common Semantics for Sharing Knowledge. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3596. pp. 52–77. doi:10.1007/11524564_4. ISBN 978-3-540-27783-5.

- ^ Chapter 1 of Laurence and Margolis’ book called Concepts: Core Readings. ISBN 9780262631938

- ^ Carey, S. (1991). Knowledge Acquisition: Enrichment or Conceptual Change? In S. Carey and R. Gelman (Eds.), The Epigenesis of Mind: Essays on Biology and Cognition (pp. 257–291). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- ^ «Cognitive Science | Brain and Cognitive Sciences».

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Eric Margolis; Stephen Lawrence. «Concepts». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab at Stanford University. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ Eysenck. M. W., (2012) Fundamentals of Cognition (2nd) Psychology Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Joseph Goguen «»The logic of inexact concepts», Synthese 19 (3/4): 325–373 (1969).

- ^ a b c Margolis, Eric; Laurence, Stephen (2007). «The Ontology of Concepts—Abstract Objects or Mental Representations?». Noûs. 41 (4): 561–593. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.188.9995. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0068.2007.00663.x.

- ^ Jerry Fodor, Concepts: Where Cognitive Science Went Wrong

- ^ a b c d e Carey, Susan (2009). The Origin of Concepts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536763-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Murphy, Gregory (2002). The Big Book of Concepts. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ISBN 978-0-262-13409-5.

- ^ McCarthy, Gabby (2018) «Introduction to Metaphysics». pg. 35

- ^ Eysenck. M. W., (2012) Fundamentals of Cognition (2nd) Psychology Taylor & Francis

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Stephen Lawrence; Eric Margolis (1999). Concepts and Cognitive Science. in Concepts: Core Readings: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. pp. 3–83. ISBN 978-0-262-13353-1.

- ^ ‘Godel’s Rationalism’, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Hampton, J.A. (1979). «Polymorphous concepts in semantic memory». Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 18 (4): 441–461. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(79)90246-9.

- ^ a b Brown, Roger (1978). A New Paradigm of Reference. Academic Press Inc. pp. 159–166. ISBN 978-0-12-497750-1.

- ^ a b c d e f TAYLOR, John R. (1989). Linguistic Categorization: Prototypes In Linguistic Theory.

- ^ Murphy, Gregory L.; Medin, Douglas L. (1985). «The role of theories in conceptual coherence». Psychological Review. 92 (3): 289–316. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.92.3.289. ISSN 0033-295X. PMID 4023146.

- ^ Mroczko-Wä…Sowicz, Aleksandra; Nikoliä‡, Danko (2014). «Semantic mechanisms may be responsible for developing synesthesia». Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8: 509. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00509. PMC 4137691. PMID 25191239.

- ^ Stevan Harnad (1995). Why and How We Are Not Zombies. Journal of Consciousness Studies 1: 164–167.

- ^ David Chalmers (1995). Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies 2 (3): 200–219.

- ^ Nikolić, D. (2009) Is synaesthesia actually ideaesthesia? An inquiry into the nature of the phenomenon. Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Synaesthesia, Science & Art, Granada, Spain, April 26–29, 2009.

- ^ Gómez Milán, E., Iborra, O., de Córdoba, M.J., Juárez-Ramos V., Rodríguez Artacho, M.A., Rubio, J.L. (2013) The Kiki-Bouba effect: A case of personification and ideaesthesia. The Journal of Consciousness Studies. 20(1–2): pp. 84–102.

- ^ Blouw, Peter; Solodkin, Eugene; Thagard, Paul; Eliasmith, Chris (2016). «Concepts as Semantic Pointers: A Framework and Computational Model». Cognitive Science. 40 (5): 1128–1162. doi:10.1111/cogs.12265. PMID 26235459.

- ^ «Homework Help and Textbook Solutions | bartleby». Archived from the original on 2008-07-06. Retrieved 2011-11-25.The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition.

Further reading[edit]

- Armstrong, S. L., Gleitman, L. R., & Gleitman, H. (1999). what some concepts might not be. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, Concepts (pp. 225–261). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Carey, S. (1999). knowledge acquisition: enrichment or conceptual change? In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 459–489). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Fodor, J. A., Garrett, M. F., Walker, E. C., & Parkes, C. H. (1999). against definitions. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 491–513). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Fodor, Jerry; Lepore, Ernest (1996). «The red herring and the pet fish: Why concepts still can’t be prototypes». Cognition. 58 (2): 253–270. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(95)00694-X. PMID 8820389. S2CID 15356470.

- Hume, D. (1739). book one part one: of the understanding of ideas, their origin, composition, connexion, abstraction etc. In D. Hume, a treatise of human nature. England.

- Murphy, G. (2004). Chapter 2. In G. Murphy, a big book of concepts (pp. 11 – 41). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Murphy, G., & Medin, D. (1999). the role of theories in conceptual coherence. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 425–459). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Prinz, Jesse J. (2002). Furnishing the Mind. doi:10.7551/mitpress/3169.001.0001. ISBN 9780262281935.

- Putnam, H. (1999). is semantics possible? In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 177–189). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Quine, W. (1999). two dogmas of empiricism. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 153–171). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Rey, G. (1999). Concepts and Stereotypes. In E. Margolis, & S. Laurence (Eds.), Concepts: Core Readings (pp. 279–301). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Rosch, E. (1977). Classification of real-world objects: Origins and representations in cognition. In P. Johnson-Laird, & P. Wason, Thinking: Readings in Cognitive Science (pp. 212–223). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rosch, E. (1999). Principles of Categorization. In E. Margolis, & S. Laurence (Eds.), Concepts: Core Readings (pp. 189–206). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Schneider, Susan (2011). «Concepts: A Pragmatist Theory». The Language of Thought. pp. 159–182. doi:10.7551/mitpress/9780262015578.003.0071. ISBN 9780262015578.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1999). philosophical investigations: sections 65–78. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 171–175). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- The History of Calculus and its Conceptual Development, Carl Benjamin Boyer, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-60509-4

- The Writings of William James, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-39188-4

- Logic, Immanuel Kant, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-25650-2

- A System of Logic, John Stuart Mill, University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 1-4102-0252-6

- Parerga and Paralipomena, Arthur Schopenhauer, Volume I, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-824508-4

- Kant’s Metaphysic of Experience, H. J. Paton, London: Allen & Unwin, 1936

- Conceptual Integration Networks. Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner, 1998. Cognitive Science. Volume 22, number 2 (April–June 1998), pp. 133–187.

- The Portable Nietzsche, Penguin Books, 1982, ISBN 0-14-015062-5

- Stephen Laurence and Eric Margolis «Concepts and Cognitive Science». In Concepts: Core Readings, MIT Press pp. 3–81, 1999.

- Hjørland, Birger (2009). «Concept theory». Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 60 (8): 1519–1536. doi:10.1002/asi.21082.

- Georgij Yu. Somov (2010). Concepts and Senses in Visual Art: Through the example of analysis of some works by Bruegel the Elder. Semiotica 182 (1/4), 475–506.

- Daltrozzo J, Vion-Dury J, Schön D. (2010). Music and Concepts. Horizons in Neuroscience Research 4: 157–167.

External links[edit]

Look up concept in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Concept at PhilPapers

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «Concepts». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Concept at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- «Concept». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- «Theory–Theory of Concepts». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- «Classical Theory of Concepts». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Blending and Conceptual Integration

- Concepts. A Critical Approach, by Andy Blunden

- Conceptual Science and Mathematical Permutations

- Concept Mobiles Latest concepts

- v:Conceptualize: A Wikiversity Learning Project

- Concept simultaneously translated in several languages and meanings

- TED-Ed Lesson on ideasthesia (sensing concepts)

English word concept comes from Latin capio (I capture, seize, take. I take in, understand. I take on.), Latin con-

Detailed word origin of concept

| Dictionary entry | Language | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| capio | Latin (lat) | I capture, seize, take. I take in, understand. I take on. |

| con- | Latin (lat) | Used in compounds to indicate a being or bringing together of several objects. Used in compounds to indicate the completeness, perfecting of any act, and thus gives intensity to the signification of the simple word. |

| concipio | Latin (lat) | I adopt. I contain or hold. I derive (from). I devise or conceive. I grasp. I receive or catch. |

| concept | English (eng) | (programming) In generic programming, a description of supported operations on a type, including their syntax and semantics.. Abstract and general idea; an abstraction. Understanding retained in the mind, from experience, reasoning and/or imagination; a generalization (generic, basic form), or abstraction (mental impression), of a particular set of instances or occurrences (specific, though […] |

Words with the same origin as concept

A concept (substantive term: conception) is a cognitive unit of meaning—an abstract idea or a mental symbol sometimes defined as a «unit of knowledge,» built from other units which act as a concept’s characteristics. A concept is typically associated with a corresponding representation in a language or symbology; however, some concepts do not have a linguistic representation, which can make them more difficult to understand depending on a person’s native language[1], such as a single meaning of a term.

There are prevailing theories in contemporary philosophy which attempt to explain the nature of concepts. The representational theory of mind proposes that concepts are mental representations, while the semantic theory of concepts (originating with Frege’s distinction between concept and object) holds that they are abstract objects.[2] Ideas are taken to be concepts, although abstract concepts do not necessarily appear to the mind as images, while some ideas appear to.[3] Many philosophers consider concepts to be a fundamental ontological category of being.

The term «concept» is traced back to 1554–60 (Latin conceptum — «something conceived»),[citation needed] but what is today termed «the classical theory of concepts» is the theory of Aristotle on the definition of terms.[citation needed] The meaning of «concept» is explored in mainstream information science,[4] [5] cognitive science, metaphysics, and philosophy of mind. In computer and information science contexts, especially, the term ‘concept’ is often used in unclear or inconsistent ways.[6]

Contents

- 1 Origin and acquisition of concepts

- 1.1 A posteriori abstractions

- 1.2 A priori concepts

- 2 Conceptual structure

- 3 One possible and likely structure

- 4 The dual nature of concepts

- 5 Conceptual content

- 5.1 Content as pragmatic role

- 5.2 Embodied content

- 6 Philosophical implications

- 6.1 Concepts and metaphilosophy

- 6.2 Concepts in epistemology

- 6.3 Ontology of concepts

- 7 Concepts in empirical investigations

- 8 See also

- 9 References

- 10 Publications

- 11 External links

Origin and acquisition of concepts

A posteriori abstractions

John Locke’s description of a general idea corresponds to a description of a concept. According to Locke, a general idea is created by abstracting, drawing away, or removing the uncommon characteristic or characteristics from several particular ideas. The remaining common characteristic is that which is similar to all of the different individuals. For example, the abstract general idea or concept that is designated by the word «red» is that characteristic which is common to apples, cherries, and blood. The abstract general idea or concept that is signified by the word «dog» is the collection of those characteristics which are common to Airedales, Collies, and Chihuahuas.

In the same tradition as Locke, John Stuart Mill stated that general conceptions are formed through abstraction. A general conception is the common element among the many images of members of a class. «…[W]hen we form a set of phenomena into a class, that is, when we compare them with one another to ascertain in what they agree, some general conception is implied in this mental operation» (A System of Logic, Book IV, Ch. II). Mill did not believe that concepts exist in the mind before the act of abstraction. «It is not a law of our intellect, that, in comparing things with each other and taking note of their agreement, we merely recognize as realized in the outward world something that we already had in our minds. The conception originally found its way to us as the result of such a comparison. It was obtained (in metaphysical phrase) by abstraction from individual things» (Ibid.).

For Schopenhauer, empirical concepts «…are mere abstractions from what is known through intuitive perception, and they have arisen from our arbitrarily thinking away or dropping of some qualities and our retention of others.» (Parerga and Paralipomena, Vol. I, «Sketch of a History of the Ideal and the Real»). In his On the Will in Nature, «Physiology and Pathology,» Schopenhauer said that a concept is «drawn off from previous images … by putting off their differences. This concept is then no longer intuitively perceptible, but is denoted and fixed merely by words.» Nietzsche, who was heavily influenced by Schopenhauer, wrote: «Every concept originates through our equating what is unequal. No leaf ever wholly equals another, and the concept ‘leaf’ is formed through an arbitrary abstraction from these individual differences, through forgetting the distinctions…»[7]

By contrast to the above philosophers, Immanuel Kant held that the account of the concept as an abstraction of experience is only partly correct. He called those concepts that result of abstraction «a posteriori concepts» (meaning concepts that arise out of experience). An empirical or an a posteriori concept is a general representation (Vorstellung) or non-specific thought of that which is common to several specific perceived objects (Logic, I, 1., §1, Note 1).

A concept is a common feature or characteristic. Kant investigated the way that empirical a posteriori concepts are created.

The logical acts of the understanding by which concepts are generated as to their form are:

- comparison, i.e., the likening of mental images to one another in relation to the unity of consciousness;

- reflection, i.e., the going back over different mental images, how they can be comprehended in one consciousness; and finally

- abstraction or the segregation of everything else by which the mental images differ …

In order to make our mental images into concepts, one must thus be able to compare, reflect, and abstract, for these three logical operations of the understanding are essential and general conditions of generating any concept whatever. For example, I see a fir, a willow, and a linden. In firstly comparing these objects, I notice that they are different from one another in respect of trunk, branches, leaves, and the like; further, however, I reflect only on what they have in common, the trunk, the branches, the leaves themselves, and abstract from their size, shape, and so forth; thus I gain a concept of a tree.

— Logic, §6

Kant’s description of the making of a concept has been paraphrased as «…to conceive is essentially to think in abstraction what is common to a plurality of possible instances…» (H.J. Paton, Kant’s Metaphysics of Experience, I, 250). In his discussion of Kant, Christopher Janaway wrote: «…generic concepts are formed by abstraction from more than one species.»[8]

A priori concepts

Kant declared that human minds possess pure or a priori concepts. Instead of being abstracted from individual perceptions, like empirical concepts, they originate in the mind itself. He called these concepts categories, in the sense of the word that means predicate, attribute, characteristic, or quality. But these pure categories are predicates of things in general, not of a particular thing. According to Kant, there are 12 categories that constitute the understanding of phenomenal objects. Each category is that one predicate which is common to multiple empirical concepts. In order to explain how an a priori concept can relate to individual phenomena, in a manner analogous to an a posteriori concept, Kant employed the technical concept of the schema.

Conceptual structure

It seems intuitively obvious that concepts must have some kind of structure. Up until recently, the dominant view of conceptual structure was a containment model, associated with the classical view of concepts. According to this model, a concept is endowed with certain necessary and sufficient conditions in their description which unequivocally determine an extension. The containment model allows for no degrees; a thing is either in, or out, of the concept’s extension. By contrast, the inferential model understands conceptual structure to be determined in a graded manner, according to the tendency of the concept to be used in certain kinds of inferences. As a result, concepts do not have a kind of structure that is in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions; all conditions are contingent (Margolis:5).

However, some theorists claim that primitive concepts lack any structure at all. For instance, Jerry Fodor presents his Asymmetric Dependence Theory as a way of showing how a primitive concept’s content is determined by a reliable relationship between the information in mental contents and the world. These sorts of claims are referred to as «atomistic», because the primitive concept is treated as if it were a genuine atom.

One possible and likely structure

Concepts are formed by people’s (or other) minds while reflecting upon their environment, subject to their sensory organs/sensors and the way such minds are in contact with their immediate and distant environment. The location of concepts is therefore assumed to be within the mind of such an organism/mechanism, more specifically in their head or equivalent place deemed to be the organ used for thinking (system of nerves or equivalent). However Concepts can be expressed in language and externalised by writing or other means such as Wikipedia. Others hold different views, such as Carl Jung, who holds that concepts may be attributed to space other than within the inside boundaries of any body or mass or material formation of living creatures. In fact some people even assume that inanimate object also have such property as «a concept» within their own solid structure.

The dual nature of concepts

Clearly, the location of concepts is not decided for good yet, but it looks certain that they are related to the external world or the environment, of which of course such a living and «thinking» creature is a part of. Thus a concept is started from outside, in the relation of conception, hence the subject is subjected to an object and has a concept of that object in a black box usually referred to as the mind. Such a content of the mind is then related to the original object that is reflected in and by the mind (for short) and it is also given another form to enable the creature to communicate about his/her/its experience of that object. In case of humans, it is usually a symbol or sign, maybe that of a language which is then also related to the external object and the internal concept in the triangle of meaning (which is the same as the triangle of reference). Do not forget that as we speak of existence as inseparable from space and time, such a relationship is established in time, meaning that whoever has a concept of whatever object with whichever name will have the three inputs synchronized. And should he be not alone at that location, he/she etc. will also check that what/whom he sees as existing is real, «objective», and not «subjective» (prone to various errors) through a dialog with the members of his/her race or community.

Conceptual content

Content as pragmatic role

Embodied content

In cognitive linguistics, abstract concepts are transformations of concrete concepts derived from embodied experience. The mechanism of transformation is structural mapping, in which properties of two or more source domains are selectively mapped onto a blended space (Fauconnier & Turner, 1995; see conceptual blending). A common class of blends are metaphors. This theory contrasts with the rationalist view that concepts are perceptions (or recollections, in Plato’s term) of an independently existing world of ideas, in that it denies the existence of any such realm. It also contrasts with the empiricist view that concepts are abstract generalizations of individual experiences, because the contingent and bodily experience is preserved in a concept, and not abstracted away. While the perspective is compatible with Jamesian pragmatism (above), the notion of the transformation of embodied concepts through structural mapping makes a distinct contribution to the problem of concept formation.

Philosophical implications

Concepts and metaphilosophy

A long and well-established tradition philosophy posits that philosophy itself is nothing more than conceptual analysis. This view has its proponents in contemporary literature as well as historical. According to Deleuze and Guattari’s What Is Philosophy? (1991), philosophy is the activity of creating concepts. This creative activity differs from previous definitions of philosophy as simple reasoning, communication or contemplation of universals. Concepts are specific to philosophy: science creates «functions», and art «sensations». A concept is always signed: thus, Descartes’ Cogito or Kant’s «transcendental». It is a singularity, not universal, and connects itself with others concepts, on a «plane of immanence» traced by a particular philosophy. Concepts can jump from one plane of immanence to another, combining with other concepts and therefore engaging in a «becoming-Other.»

Concepts in epistemology

For more details on this topic, see List of concepts in science.

Concepts are vital to the development of scientific knowledge. For example, it would be difficult to imagine physics without concepts like: energy, force, or acceleration. Concepts help to integrate apparently unrelated observations and phenomena into viable hypotheses and theories, the basic ingredients of science. The concept map is a tool that is used to help researchers visualize the inter-relationships between various concepts.

Ontology of concepts

Although the mainstream literature in cognitive science regards the concept as a kind of mental particular, it has been suggested by some theorists that concepts are real things (Margolis:8). In most radical form, the realist about concepts attempts to show that the supposedly mental processes are not mental at all; rather, they are abstract entities, which are just as real as any mundane object.

Plato was the starkest proponent of the realist thesis of universal concepts. By his view, concepts (and ideas in general) are innate ideas that were instantiations of a transcendental world of pure forms that lay behind the veil of the physical world. In this way, universals were explained as transcendent objects. Needless to say this form of realism was tied deeply with Plato’s ontological projects. This remark on Plato is not of merely historical interest. For example, the view that numbers are Platonic objects was revived by Kurt Gödel as a result of certain puzzles that he took to arise from the phenomenological accounts.[9]

Gottlob Frege, founder of the analytic tradition in philosophy, famously argued for the analysis of language in terms of sense and reference. For him, the sense of an expression in language describes a certain state of affairs in the world, namely, the way that some object is presented. Since many commentators view the notion of sense as identical to the notion of concept, and Frege regards senses as the linguistic representations of states of affairs in the world, it seems to follow that we may understand concepts as the manner in which we grasp the world. Accordingly, concepts (as senses) have an ontological status (Morgolis:7).

According to Carl Benjamin Boyer, in the introduction to his The History of the Calculus and its Conceptual Development, concepts in calculus do not refer to perceptions. As long as the concepts are useful and mutually compatible, they are accepted on their own. For example, the concepts of the derivative and the integral are not considered to refer to spatial or temporal perceptions of the external world of experience. Neither are they related in any way to mysterious limits in which quantities are on the verge of nascence or evanescence, that is, coming into or going out of appearance or existence. The abstract concepts are now considered to be totally autonomous, even though they originated from the process of abstracting or taking away qualities from perceptions until only the common, essential attributes remained.

Concepts in empirical investigations

Concepts, as abstract units of meaning, play a key role in the development and testing of theories. For example, a simple relational hypothesis can be viewed as either a conceptual hypothesis (where the abstract concepts form the meaning) or an operationalized hypothesis, which is situated in the real world by rules of interpretation. For example, take the simple hypothesis Education increases Income. The abstract notion of education and income (concepts) could have many meanings.

A conceptual hypothesis cannot be tested. They need to be converted into operational hypothesis or the abstract meaning of education must be derived or operationalized to something in the real world that can be measured. Education could be measured by “years of school completed” or “highest degree completed” etc. Income could be measured by “hourly rate of pay” or “yearly salary”, etc. The system of concepts or conceptual framework can take on many levels of complexity. When the conceptual framework is very complex and incorporates causality or explanation they are generally referred to as a theory.

The noted philosopher of science Carl Gustav Hempel says this more eloquently: “An adequate empirical interpretation turns a theoretical system into a testable theory: The hypothesis whose constituent terms have been interpreted become capable of test by reference to observable phenomena. Frequently the interpreted hypothesis will be derivative hypotheses of the theory; but their confirmation or disconfirmation by empirical data will then immediately strengthen or weaken also the primitive hypotheses from which they were derived.”[10]

Hempel provides a useful metaphor that describes the relationship between the conceptual framework and the framework as it is observed and perhaps tested (interpreted framework): “The whole system floats, as it were, above the plane of observation and is anchored to it by rules of interpretation. These might be viewed as strings which are not part of the network but link certain points of the latter with specific places in the plane of observation. By virtue of those interpretative connections, the network can function as a scientific theory”.[11]

See also

- Abstraction

- Categorization

- Class (philosophy)

- Concept and object

- Concept car

- Concept learning

- Concept map

- Concept single

- Conceptual art

- Conceptual blending

- Conceptual clustering

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual history (also termed: ‘History of concepts’ or ‘Begriffsgeschichte’)

- Conceptual model

- Conveyed concept

- Definitionism

- Formal concept analysis

- Fuzzy concept

- Hypostatic abstraction

- Idea

- Meme

- Notion (philosophy)

- Object (philosophy)

- Philosophy

- Recept

- Schema (Kant)

- Social construction

- Symbol grounding problem

References

- ^ Lston-Güttler, Kerrie E., and John N. Williams. «First Language Polysemy Affects Second Language Meaning Interpretation: Evidence for Activation of First Language Concepts during Second Language Reading.» Second Language Research 24.2 (2008). Second Language Research. Web. <http://slr.sagepub.com/content/24/2/167.abstract>.

- ^ The Ontology of Concepts—Abstract Objects or Mental Representations?, Eric Margolis and Stephen Laurence

- ^ Cambribdge Dictionary of Philosophy, ed. Audi

- ^ Stock, W.G. (2010). Concepts and semantic relations in information science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(10), 1951-1969.

- ^ Hjørland, B. (2009). Concept Theory. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(8), 1519–1536

- ^ Smith, B. (2004). Beyond Concepts, or: Ontology as Reality Representation, Formal Ontology and Information Systems. Proceedings of the Third International Conference (FOIS 2004), Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2004, 73–84.

- ^ «On Truth and Lie in an Extra–Moral Sense,» The Portable Nietzsche, p. 46

- ^ Christopher Janaway, Self and World in Schopenhauer’s Philosophy, Ch. 3, p. 112, Oxford, 2003, ISBN 0-19-825003-7

- ^ ‘Godel’s Rationalism’, Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Hempel, C. G. (1952). Fundamentals of concept formation in empirical science. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, p. 35.

- ^ Hempel, C. G. (1952). Fundamentals of concept formation in empirical science. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, p. 36.

A concept is a system of general ideas targeting the multilateral treatment/interpretation of economic, social, legal, scientific, technical and other problems, and reflecting the manner of perception or the multitude of opinions, ideas regarding problems associated with to the development of one or several fields or sectors as a whole.

Publications

- The History of Calculus and its Conceptual Development, Carl Benjamin Boyer, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-60509-4

- The Writings of William James, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-39188-4

- Logic, Immanuel Kant, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-25650-2

- A System of Logic, John Stuart Mill, University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 1-4102-0252-6

- Parerga and Paralipomena, Arthur Schopenhauer, Volume I, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-824508-4

- What is Philosophy?, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari

- Kant’s Metaphysic of Experience, H. J. Paton, London: Allen & Unwin, 1936

- Conceptual Integration Networks. Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner, 1998. Cognitive Science. Volume 22, number 2 (April–June 1998), pages 133-187.

- The Portable Nietzsche, Penguin Books, 1982, ISBN 0-14-015062-5

- Stephen Laurence and Eric Margolis «Concepts and Cognitive Science». In Concepts: Core Readings, MIT Press pp. 3–81, 1999.

- Birger Hjørland. (2009). Concept Theory. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(8), 1519–1536

- Georgij Yu. Somov (2010). Concepts and Senses in Visual Art: Through the example of analysis of some works by Bruegel the Elder. Semiotica 182 (1/4), 475–506.

- Daltrozzo J, Vion-Dury J, Schön D. (2010). Music and Concepts. Horizons in Neuroscience Research 4: 157-167. [1]

External links

- E. Margolis and S. Lawrence (2006), Concepts entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Blending and Conceptual Integration

- Conceptual Science and Mathematical Permutations

- Concept Mobiles Latest concepts

- v:Conceptualize: A Wikiversity Learning Project

- Concept simultaneously translated in several languages and meanings

- Product Research and Conceptualization

| v · d · ePhilosophy of language | |

|---|---|

| Philosophers |

Plato (Cratylus) • Confucius • Xun Zi • Aristotle • Stoics • Pyrrhonists • Scholasticism • Ibn Rushd • Ibn Khaldun • Thomas Hobbes • Gottfried Leibniz • Johann Herder • Wilhelm von Humboldt • Fritz Mauthner • Paul Ricœur • Ferdinand de Saussure • Gottlob Frege • Franz Boas • Paul Tillich • Edward Sapir • Leonard Bloomfield • Zhuangzi • Henri Bergson • Ludwig Wittgenstein (Philosophical Investigations • Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus) • Bertrand Russell • Rudolf Carnap • Jacques Derrida (Of Grammatology • Limited Inc) • Benjamin Lee Whorf • Gustav Bergmann • J. L. Austin • Noam Chomsky • Hans-Georg Gadamer • Saul Kripke • Alfred Jules Ayer • Donald Davidson • Paul Grice • Gilbert Ryle • P. F. Strawson |

| Theories |

Causal theory of reference • Contrast theory of meaning • Contrastivism • Conventionalism • Cratylism • Deconstruction • Descriptivist theory of names • Direct reference theory • Dramatism • Expressivism • Linguistic determinism • Logical atomism • Logical positivism • Mediated reference theory • Nominalism • Non-cognitivism • Phallogocentrism • Quietism • Relevance theory • Semantic externalism • Semantic holism • Structuralism • Supposition theory • Symbiosism • Theological noncognitivism • Theory of descriptions • Verification theory |

| Concepts |

Ambiguity • Linguistic relativity • Meaning • Language • Truthbearer • Proposition • Use–mention distinction • Concept • Categories • Set • Class • Intension • Logical form • Metalanguage • Mental representation • Principle of compositionality • Property • Sign • Sense and reference • Speech act • Symbol • Entity • Sentence • Statement • more… |

| Related articles |

Analytic philosophy • Language • Philosophy of information • Philosophical logic • Linguistics • Pragmatics • Rhetoric • Semantics • Formal semantics • Semiotics |

|

Category · Task Force · Discussion |

| v · d · ePhilosophy of mind | |

|---|---|

| Philosophers |

Austin · Bain · Bergson · Bhattacharya · Block · Broad · Dennett · Dharmakirti · Davidson · Descartes · Goldman · Heidegger · Husserl · James · Kierkegaard · Leibniz · Merleau-Ponty · Minsky · Moore · Nagel · Popper · Rorty · Ryle · Searle · Spinoza · Turing · Vasubandhu · Wittgenstein · Zhuangzi · more… |

| Theories |

Behaviourism · Biological naturalism · Dualism · Eliminative materialism · Emergent materialism · Epiphenomenalism · Functionalism · Identity theory · Interactionism · Materialism · Mind-body problem · Monism · Naïve realism · Neutral monism · Phenomenalism · Phenomenology (Existential phenomenology) · Physicalism · Pragmatism · Property dualism · Representational theory of mind · Solipsism · Substance dualism |

| Concepts |

Abstract object · Artificial intelligence · Chinese room · Cognition · Concept · Concept and object · Consciousness · Idea · Identity · Ingenuity · Intelligence · Intentionality · Introspection · Intuition · Language of thought · Materialism · Mental event · Mental image · Mental process · Mental property · Mental representation · Mind · Mind-body dichotomy · Pain · Problem of other minds · Propositional attitude · Qualia · Tabula rasa · Understanding · more… |

| Related articles |

Metaphysics · Philosophy of artificial intelligence · Philosophy of information · Philosophy of perception · Philosophy of self |

|

Portal · Category · Task Force · Discussion |

КОНЦЕПТ (от лат. conceptus — собрание, восприятие, зачатие) — акт “схватывания” смыслов вещи (проблемы) в единстве речевого высказывания. Термин “концепт” введен в философию Абеляром в связи с анализом проблемы универсалий, потребовавшим расщепления языка и речи. Принцип “схватывания” прослеживается с ранней патристики, поскольку он связан с идеей неопределимости вещи, превосходящей рамки понятия, модальным характером знания, при котором приоритетным оказывалось знание диалектическое (формой его организации был диспут), и комментарием, которого требовало все сотворенное, рассчитанное на понимание и выраженное в произведении. Акт понимания не мог разворачиваться в линейной последовательности рассуждения, единицей которого было предложение, он требовал полноты смыслового выражения в целостном процессе произнесения. Высказывание становится единицей речевого общения. Речь была охарактеризована как сущность, обладающая субъектностью, смыслоразделительной функцией и смысловым единством. Она стояла в тесной связи с идеями творения, воплощения Слова и интенции, присущей субъекту как его активное начало и полагавшей акт обозначения и его результат — значение внутри обозначаемого. Это — не диахронический процесс звуковой последовательности, а синхронический процесс выявления смыслов, требующий по меньшей мере двух участников речевого акта — говорящего и слушающего, вопрошающего и отвечающего, чтобы быть вместе и понятым и услышанным. Обращенность к “другому” (имманентный план бытия) предполагала одновременную обращенность к трансцендентному источнику слова — Богу, потому речь, произносимая при “Боге свидетеле”, всегда предполагалась как жертвенная речь. Высказанная речь, по Абеляру, воспринимается как “концепт в душе слушателя” (Абеляр П. Диалектика. — В кн.: Он же. Теологические трактаты. М., 1995, с. 121). Концепт, в отличие от формы “схватывания” в понятии (intellectus), которое связано с формами рассудка, есть производное возвышенного духа (ума), который способен творчески воспроизводить, или собирать (concipere) смыслы и помыслы как универсальное, представляющее собой связь вещей и речей, и который включает в себя рассудок как свою часть. Концепт как высказывающая речь, т. о., не тождествен понятию.

Многие (в т. ч. современные) исследователи не заметили введения нового термина для обозначения смысла высказыва нпя, потому в большинстве философских словарей и энциклопедий концепт отождествляется с понятием. Между тем концепт и понятие необходимо четко различать друг от друга.

Понятие есть объективное единство различных моментов предмета понятия, которое создано на основании правил рассудка или систематичности знаний. Оно неперсонально, непосредственно связано со знаковыми и значимыми структурами языка, выполняющего функции становления определенной мысли, независимо от общения. Это итог, ступени или моменты познания.

Концепт формируется речью (введением этого термина прежде единое Слово жестко разделилось на язык и речь). Речь осуществляется не в сфере грамматики (грамматика включена в нее как часть), ав пространстве души с ее ритмами, энергией, жестикуляцией, интонацией, бесконечными уточнениями, составляющими смысл комментаторства. Концепт предельно субъектен. Изменяя душу индивида, обдумывающего вещь, он при своем формировании предполагает другого субъекта (слушателя, читателя), актуализируя смыслы в ответах на его вопросы, что и рождает диспут. Обращенность к слушателю всегда предполагала одновременную обращенность к трансцендентному источнику речи — Богу. Память и воображение — неотторжимые свойства концепта, направленного, с одной стороны, на понимание здесь и теперь; с другой стороны — концепт синтезирует в себе три способности души и как акт памяти ориентирован в прошлое, как акт воображения — в будущее, как акт суждения — в настоящее. Глгьберт Порретанский на основании идеи концепта образует понятие конкретного целого и вводит идею сингулярности (см. Средневековая западноевропейская философия). У Фомы Аквинского концепт есть внутреннее постижение вещи в уме, выраженное через знак, через единство идеального и материально-феноменального. Иоанн Дунс Скот определяет концепт как мыслимое сущее, которому присуща “этовость”, понятая как внутренний принцип вещи. Начиная с 14 в., с возникновением онтологического предположения об однозначности бытия (см. Эквивокаи/ш}, идея концепта стала исчезать. В Новое время, характеризующееся научным способом познания, концепт полностью был замещен понятием как наиболее адекватным постижением истинности вещи, представленной как объект и не требующей обсуждения. Однако необходимость в нем постоянно давала о себе знать. На разнообразные формы “схватывания” обратил внимание Кант, затем Шеллинг, определяя их через фигуры творчества.

В 20 в. идеи концепта прослеживаются в персоналистских философиях, во главу угла ставящих идею произведения (Μ. Μ. Бахтин, В. С. Библер). В качестве термина концепт присутствует в постмодернистской философии. Ж. Делёз и Ф. Гваттари обратили внимание на то, что философы “недостаточно занимались природой концепта как философской реальности”. Они сделали попытку выделить три этапа развития концепта: посткантианская энциклопедия концепта, связывающая его сотворение с чистой субъективностью; педагогика концепта, анализирующая условия творчества как факторы единичных моментов, и профессионально-коммерческая подготовка (Делёз Ж., Гваттари Ф. Что такое философия? М., 1998, с. 22). Делёз и Гваттари, правда, не столько разъясняют различие между понятием и концептом (распро

страняя его на всякую философию — “от Платона до Бергсона”), сколько подчеркивают недостаточность понятия и вскрывают моменты, где понятие перерастает само себя. Средневековью в поэтапном делении развития концепта места не нашлось, между тем идею концепта вновь вызвала к жизни именно обращенность к идее творчества, которое “всегда единично, и концепт как собственно философское творение всегда есть нечто единичное”, и к связанной с творчеством идее речи, представленной в “устойчивых сгустках смысла” и открытой Средневековьем. Эти два момента роднят понимание концепта в средневековой и постмодернистской философии. Однако сама речь (соответственно концепт) наполнена иным содержанием. В отличие от Средневековья, она ориентирована не на двуосмысленное собеседование (с Творцом и со слушателем-ответчиком), предполагающее трансцендентный и имманентный планы бытия, а только на имманентное с его “бесконечными переменностями”. Речь рассматривается как игра ассоциаций и интерпретаций, уничтожающая любой текст (дело касается прежде всего священных текстов) и превращающая его в объект властных претензий. Концепт в постмодернистском понимании есть поле распространенных в пространстве суггестивных знаков. Поскольку в речи к тому же просматриваются объективно-языковые формы выражения, то терминологически концепт от понятия трудно отличим, становясь двусмысленным термином.

Лит.: Бахтин М. М. Эстетика словесного творчества. М„ 1975; Библер В. С. От наукоучения к логике культуры. Два философских введения в XXI век. М., 1991; Неретина С. С. Верующий разум. К истории средневековой философии. Архангельск, 1995; Она же. Слово и текст в средневековой культуре. Концептуализм Петра Абеляра. М., 1996; Делёз Ж. Различие и повторение. СПб., 19%;ДелезЖ., Гваттари Ф. Что такое философия? М., 1998.

С. С. Неретина

Новая философская энциклопедия: В 4 тт. М.: Мысль.

Под редакцией В. С. Стёпина.

2001.

Educalingo cookies are used to personalize ads and get web traffic statistics. We also share information about the use of the site with our social media, advertising and analytics partners.

Download the app

educalingo

‘District 9’, ‘Elysium’ and ‘Chappie’ were all born out of some visual concept first. ‘Chappie’ is the imagery, because I think I’m a visual person first, of this ridiculous robot character. It’s much more comedy based and in an unusual setting.

Neill Blomkamp

ETYMOLOGY OF THE WORD CONCEPT

From Latin conceptum something received or conceived, from concipere to take in, conceive.

Etymology is the study of the origin of words and their changes in structure and significance.

PRONUNCIATION OF CONCEPT

GRAMMATICAL CATEGORY OF CONCEPT

Concept is a noun.

A noun is a type of word the meaning of which determines reality. Nouns provide the names for all things: people, objects, sensations, feelings, etc.

WHAT DOES CONCEPT MEAN IN ENGLISH?

Concept

In metaphysics, and especially ontology, a concept is a fundamental category of existence. In contemporary philosophy, there are at least three prevailing ways to understand what a concept is: ▪ Concepts as mental representations, where concepts are entities that exist in the brain. ▪ Concepts as abilities, where concepts are abilities peculiar to cognitive agents. ▪ Concepts as abstract objects, where objects are the constituents of propositions that mediate between thought, language, and referents.

Definition of concept in the English dictionary

The first definition of concept in the dictionary is an idea, esp an abstract idea. Other definition of concept is a general idea or notion that corresponds to some class of entities and that consists of the characteristic or essential features of the class. Concept is also the conjunction of all the characteristic features of something.

WORDS THAT RHYME WITH CONCEPT

Synonyms and antonyms of concept in the English dictionary of synonyms

SYNONYMS OF «CONCEPT»

The following words have a similar or identical meaning as «concept» and belong to the same grammatical category.

Translation of «concept» into 25 languages

TRANSLATION OF CONCEPT

Find out the translation of concept to 25 languages with our English multilingual translator.

The translations of concept from English to other languages presented in this section have been obtained through automatic statistical translation; where the essential translation unit is the word «concept» in English.

Translator English — Chinese

观念

1,325 millions of speakers

Translator English — Spanish

concepto

570 millions of speakers

English

concept

510 millions of speakers

Translator English — Hindi

अवधारणा

380 millions of speakers

Translator English — Arabic

مفهوم

280 millions of speakers

Translator English — Russian

концепция

278 millions of speakers

Translator English — Portuguese

conceito

270 millions of speakers

Translator English — Bengali

ধারণা

260 millions of speakers

Translator English — French

concept

220 millions of speakers

Translator English — Malay

Konsep

190 millions of speakers

Translator English — German

Konzept

180 millions of speakers

Translator English — Japanese

概念

130 millions of speakers

Translator English — Korean

개념

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Javanese

Konsep

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Vietnamese

khái niệm

80 millions of speakers

Translator English — Tamil

கருத்து

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Marathi

संकल्पना

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Turkish

kavram

70 millions of speakers

Translator English — Italian

concetto

65 millions of speakers

Translator English — Polish

pojęcie

50 millions of speakers

Translator English — Ukrainian

концепція

40 millions of speakers

Translator English — Romanian

conceptul

30 millions of speakers

Translator English — Greek

έννοια

15 millions of speakers

Translator English — Afrikaans

konsep

14 millions of speakers

Translator English — Swedish

koncept

10 millions of speakers

Translator English — Norwegian

konsept

5 millions of speakers

Trends of use of concept

TENDENCIES OF USE OF THE TERM «CONCEPT»

The term «concept» is very widely used and occupies the 3.018 position in our list of most widely used terms in the English dictionary.

FREQUENCY

Very widely used

The map shown above gives the frequency of use of the term «concept» in the different countries.

Principal search tendencies and common uses of concept

List of principal searches undertaken by users to access our English online dictionary and most widely used expressions with the word «concept».

FREQUENCY OF USE OF THE TERM «CONCEPT» OVER TIME

The graph expresses the annual evolution of the frequency of use of the word «concept» during the past 500 years. Its implementation is based on analysing how often the term «concept» appears in digitalised printed sources in English between the year 1500 and the present day.

Examples of use in the English literature, quotes and news about concept

10 QUOTES WITH «CONCEPT»

Famous quotes and sentences with the word concept.

I think the durability of the sedan as well as its worldwide appeal argues well for it as a concept that resonates with people’s ideas about how their lives are oriented. They understand the difference between an area for powertrain, an area for people, and an area for their stuff.

One of the biggest mistakes that people make when they think about memes is they try to extend on the analogy with genes. That’s not how it works. It works by realizing the concept of a replicator.

‘District 9’, ‘Elysium’ and ‘Chappie’ were all born out of some visual concept first. ‘Chappie’ is the imagery, because I think I’m a visual person first, of this ridiculous robot character. It’s much more comedy based and in an unusual setting.

I wondered how they would top the Pirates and skeletons and moonlight, because that’s a pretty cool concept.

For some reason, the concept of writing with swing chords was intimidating.

One concept corrupts and confuses the others. I am not speaking of the Evil whose limited sphere is ethics; I am speaking of the infinite.

War today is such a more visible thing. We see it on television, on CNN. In 1914, war was a concept.

The whole concept behind ‘Forty Chances’ is really a mindset: If everybody thought they had to put themselves out of business in 40 years, you had 40 chances to succeed in what your primary goals are, you would probably be more urgent and you would be forced to change quicker.

Freud taught us that it wasn’t God that imposed judgment on us and made us feel guilty when we stepped out of line. Instead, it was the superego — that idealized concept of what a good person is supposed to be and do — given to us by our parents, that condemned us for what had been hitherto regarded as ungodly behavior.

If I had a personal wish for the new ideas in this new book it would be that every parent, every counselor, every teacher, every professor, every sports coach that deals with young people would understand the three circle concept.

10 ENGLISH BOOKS RELATING TO «CONCEPT»

Discover the use of concept in the following bibliographical selection. Books relating to concept and brief extracts from same to provide context of its use in English literature.

1

The Concept of the Political: Expanded Edition

In addition to analysis by Leo Strauss and a foreword by Tracy B. Strong placing Schmitt’s work into contemporary context, this expanded edition also includes a translation of Schmitt’s 1929 lecture “The Age of Neutralizations and …

2

The Concept of Representation

Contents — Introduction; The Problem of Thomas Hobbes; Formalistic Views of Representation; ‘Standing For’ — Descriptive Representation; ‘Standing For’ — Symbolic Representation; Representing as ‘Acting For’ — The Analogies; The Mandate …

Hanna Fenichel Pitkin, 1967

3

The Dastgah Concept in Persian Music

In this book Hormoz Farhat has unravelled the art of the dastgah by analysing their intervallic structure, melodic patterns, modulations, and improvisations, and by examining the composed pieces which have become a part of the classical …

The Concept of Law is one of the most influential texts in English-language jurisprudence. 50 years after its first publication its relevance has not diminished and in this third edition, Leslie Green adds an introduction that places the …

HLA Hart, Herbert Lionel Adolphus Hart, Joseph Raz, 2012

5

Product Concept Design: A Review of the Conceptual Design of …

The book will be bought by designers and managers in industry, as well as lecturers in design and design engineering and their students.

Turkka Kalervo Keinonen, Roope Takala, 2010

6

Concept of the Corporation

The themes this volume addresses go far beyond the business corporation, into a consideration of the dynamics of the so-called corporate state itself.

7

High Concept: Movies and Marketing in Hollywood

Justin Wyatt describes how box office success, always important in Hollywood, became paramount in the era in which major film studios passed into the hands of media conglomerates concerned more with the economics of filmmaking than …

This now-classic work challenges what Ryle calls philosophy’s «official theory,» the Cartesians «myth» of the separation of mind and matter.

This is a strong and significant book, a far-ranging, insightful, and incisive exploration of the concept of utopia.

10

A Hierarchical Concept of Ecosystems

The authors of this book argue that previous attempts to define the concept have been derived from particular viewpoints to the exclusion of others equally possible.

10 NEWS ITEMS WHICH INCLUDE THE TERM «CONCEPT»

Find out what the national and international press are talking about and how the term concept is used in the context of the following news items.

Photos Of The Microsoft Lumia 940 Concept Surface

But a concept design of the Microsoft Lumia 940 has popped up, showcasing the handset like never before. Designer Jonas Daehnert, who is … «International Business Times, Jul 15»

Photo: Check out this new Ohio State football concept uniform

Remember, these are concept designs, meaning Ohio State won’t actually be wearing them. However, if the Buckeyes did wear something like … «Big Ten Network, Jul 15»

‘Hands-Free Tinder’ concept app selects dates who get your heart …

In the video above, the Apple Watch concept app uses the device’s heart-rate monitoring feature: You simply look at the photo on your Watch, … «Mashable, Jul 15»

Principal accused of indecently assaulting student

Symonds had been a teacher at the Concept School since 2004 and head of school since 2012, according to the district attorney’s office. «The News Journal, Jul 15»

New sports bar concept to open in Clarksville in 2016

Bubba’s 33 is a new concept from Texas Roadhouse, the closest of which is currently in Greenwood, Ind. The new restaurant will feature more … «WDRB, Jul 15»

Concept allows Hartford community to propose, vote on city projects