We use different languages worldwide to communicate with each other. Every so often we wonder where a word came from. How did a particular word start being used as a common word worldwide and where did it actually originate from. So to find this out we will explore the world of languages and origin of words in this article. This article will cover websites which will let you know the origin of a word.

The study of origin of a word is known as Etymology. You will find that often there are popular tales behind the origin of a word. Most of these tales are just tales and not true, but knowing how the word came into being is equally interesting. So let’s look at these websites to know the origin of words below.

Online Etymology Dictionary

Online etymology dictionary explains you the origin of words and what they meant along with how they would have sounded years back. You would see a date beside each word. This date represents the earliest evidence of this word being used in some sort of written manuscript. Now you can either search for a word you are looking for by typing it in the search box given at the top of the page, otherwise you can browse the words alphabetically. The website has a huge collection of words in it. You can go through the words and find out there origins and meanings as well.

Word Origins by English Oxford Living Dictionaries

Word Origins by English Oxford Living Dictionaries is a good website to know about a words origin. You can check out origin of a word or a phrase. You can search for the word or a phrase you are looking for or can even browse the page to know origin of different words. The website apart from this has a dictionary, thesaurus, grammar helper, etc. As this app has a dictionary, it proves to be a good source for knowing the origin of a word. You can see trending words when you scroll down the page. You can also subscribe to the newsletter on this website to receive updates regarding new words, phrases, etc.

Wordorigins.org

The website Wordorigins.org will let you know the origin of words and phrases. The website has a big list of words which you can go through, or even search for a particular word that you are looking for. The website also has a blog and discussion forum where people can discuss there views. You can login and become a member of the website so you receive regular updates from the website. You can either start browsing words by going to the big list words tab, or by searching for a word. The big list of words is in alphabetical order and there are about 400 words in here. Each word has a interesting story or folklore related to it.

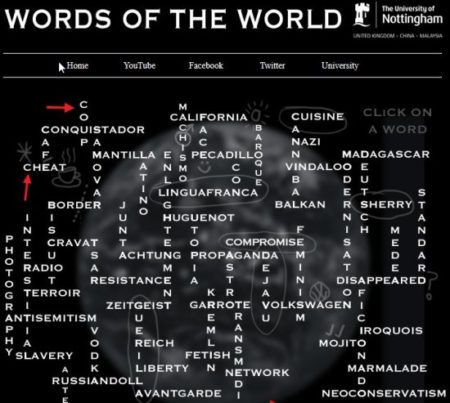

Words of the World

Words of the World is a website which lets you watch videos to let you know the origin of a word. The website explains which language a word originated from through a video. The home page of the website will have a list of words for which you can see a video explaining how the word originated. The words on the home page are given in the format as shown in the screenshot above, but they can also be turned into a neat list if you like. The website is supported by the University of Nottingham and thus is a trusted source.

Learning Nerd

Learning Nerd is another website which has a section on English etymology resources. The website lists references to origin of words like there are word origin dictionaries listed, words with Greek and Latin roots are under a different category, words originating from around the world can be found under international words, and then there is a section for miscellaneous words. You can also play etymology quizzes and listen to etymology podcasts as well. The website itself doesn’t have much information about word origins but will redirect you to another website for your word needs.

Learn That Word

Learn That Word is another website which lists root words and prefixes. The website is pretty basic and a list of words can be seen right on the first page. The words are listed alphabetically, so you can even jump to a word that you are looking for easily. The website will list the root word, its meaning, its place of origin, and then definition and examples. This can be seen in the screenshot above.

These are the websites I found which let you know the origin of a word. Go through them and let me know which one you liked most. If you think there is a website which could be included in this article then leave a comment below.

Download Article

Download Article

The origin of the meaning and sound of words (etymology) is a fascinating and rewarding subject. The previous sentence alone has words of Latin, Greek, Anglo-Saxon, and Germanic origins! Investigating the linguistic root and history of a word can be an enjoyable pastime or a full-fledged profession that’ll help you understand why we say the things we do and why we say them in the way we do. It can also improve your vocabulary, enhance your spelling, and give you lots of fun facts to share that’ll impress your friends and colleagues.

-

1

Find a good etymological dictionary. To start informally studying etymology, buy or gain access to an authoritative dictionary that includes the linguistic origins of words in its definitions. The easiest way to tell that it does is if it has, “etymological” in the title. However, it may still include etymologies even if it does not include this in the title. Check a definition to see if there is a section labeled “origin” or “etymology.”[1]

- The most respected print dictionaries for English’s etymology include An Etymological Dictionary of Modern English, A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the English Language, and The Oxford English Dictionary. The last also has an online subscription option.

- There is also a free, well-researched online dictionary that’s specifically dedicated to etymology, available here: http://www.etymonline.com/

-

2

Look for the roots. Etymologies seek the earliest origin of a word by tracing it back to its most basic components, that is, the simple words that were combined to create it in the first place. When you know the roots of a word, you can better understand how we arrived at the sound and meaning for the word that exist today.[2]

- For instance, the word “etymology” itself has Greek roots: “etymos,” which means, “true sense,” and “logia,” which means, “study of.”[3]

- Besides helping you to understand the origin of a word, knowing its roots can help you understand other words with similar roots. In the case of “etymology,” you’ll note that the root “logia,” which means “the study of,” appears in multiple other places in modern English, from “biology” to “astrology.”[4]

- Take note of any patterns you find, particularly if you’re working with the etymologies of multiple words. This will help streamline your studies.

Advertisement

- For instance, the word “etymology” itself has Greek roots: “etymos,” which means, “true sense,” and “logia,” which means, “study of.”[3]

-

3

Trace the word’s journey into English. Etymology traces not only the word’s origins but also how its meanings and spellings have developed over time. Sometimes that means that a word has traveled through more than one language on its journey into modern English.[5]

- Etymological dictionaries will usually present this trajectory in reverse-chronological order, starting with the most recent usage and showing where each iteration came from in turn.

- If we return to the word “etymology,” it entered into Old English as ethimolegia («facts of the origin and development of a word»), from Old French etimologie, ethimologie, from Latin etymologia, from Greek etymologia («analysis of a word to find its true origin»). So, it appeared in the written record of 3 languages (Greek, Latin, and French) before it entered into English.

-

4

Understand the dates. Most etymologies will include dates in their origins of words. These represent the first time a particular word appeared in a document written in English. (Keep in mind that a word may well have existed in spoken English a long time before that, but this is the date of the first written record of it that has survived.)[6]

- For example, “etymology” entered English in the 14th century but did not take on its modern spelling and definition until the 1640s.[7]

- For example, “etymology” entered English in the 14th century but did not take on its modern spelling and definition until the 1640s.[7]

-

5

Check the examples and sources. Thorough etymological dictionaries will often include documentary sources for each iteration of a word and/or examples of how a word has been used in context over time, usually through a phrase or sentence from a written document in English. This provides concrete historical evidence for the word’s origins while giving you insight into how its meaning has changed.

- For instance, the word “queen” comes from the Middle English “quene,” which can be seen in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, and the Old English “cwen,” which appears in Beowulf.[8]

- For instance, the word “queen” comes from the Middle English “quene,” which can be seen in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, and the Old English “cwen,” which appears in Beowulf.[8]

Advertisement

-

1

Look up words you’re curious about. Now that you know what to look for, start studying the etymology of those words that make you wonder, “Where did this come from?” It’s an entertaining way to get to know the historical meaning behind the things you say, and you’ll often be surprised about where they come from.

- It’s also edifying to look up those words that seem so normal that you’ve taken their origins for granted. For instance, if you study the etymology of a familiar word like “nostril,” you’ll find that it comes from Old English “nosu” (nose) and “pyrel” or “thrill” (hole). It’s literally a “nose hole.” You’ll also note that “pyrel” and “thrill” once sounded alike in English, which shows how far the language has developed phonically. That also means that the word “nostril” is surprisingly related to the word “thrilling.”

-

2

Follow up on surprising word origins. If what you find when you look into the etymology of a particular word does not make obvious sense today, do some research to figure out why its original meaning is what it is. If you’re writing a paper on etymology, briefly discuss these origins and why they are unexpected.

- For instance, you may wonder where a word like “disaster” came from. When you look it up, you’ll find that its Greek roots are the negative prefix “dis” and “astron” (star). So, it’s earliest meaning was something like “bad star.” This might be surprising until you consider Greek astrology and their strong belief that celestial bodies exerted control over our lives on Earth.[9]

- For instance, you may wonder where a word like “disaster” came from. When you look it up, you’ll find that its Greek roots are the negative prefix “dis” and “astron” (star). So, it’s earliest meaning was something like “bad star.” This might be surprising until you consider Greek astrology and their strong belief that celestial bodies exerted control over our lives on Earth.[9]

-

3

Recognize related words. Now that you know the origin of a particular word, you can use it to identify words with similar histories and therefore with related sounds and meanings.[10]

- In the case of etymology, there are not a lot of related words, but you can see that “etymological,” “etymologically,” and “etymologist” are all closely related forms. In the case of a word like “autopsy” with the Greek root “autos” (meaning, “self”), there’ll be a whole host of related words, from “autonomy” (self-governing) to “automobile” (self-moving) to “automatic” (self-acting).[11]

- In the case of etymology, there are not a lot of related words, but you can see that “etymological,” “etymologically,” and “etymologist” are all closely related forms. In the case of a word like “autopsy” with the Greek root “autos” (meaning, “self”), there’ll be a whole host of related words, from “autonomy” (self-governing) to “automobile” (self-moving) to “automatic” (self-acting).[11]

Advertisement

-

1

Get an etymology app. You can make studying etymology part of your daily routine by downloading a related app on one or more of your devices. That way, you can carry your hobby with you wherever you go. These apps can also help you understand how words have evolved from their origins and provide you with new perspectives.

- Etymology Explorer gives you engaging visual maps of word origins that are complete with full definitions, linguistic histories, and links to related words.[12]

- WordBook is a comprehensive dictionary app with a significant etymological component that provides the word origins and links to related words for thousands of entries.

- Etymology Explorer gives you engaging visual maps of word origins that are complete with full definitions, linguistic histories, and links to related words.[12]

-

2

Take a related MOOC. Sometimes there are free Massive Online Courses available on etymology. They’re taught by qualified professors at top universities and colleges, so you’re getting a dose of higher education on word history at no charge![13]

- The Open University has a free online course available on the history of the English Language that you can take at your own pace. It explores etymology alongside lexicography.[14]

- The Open University has a free online course available on the history of the English Language that you can take at your own pace. It explores etymology alongside lexicography.[14]

-

3

Go to the library. Search your local library’s online catalog for textbooks, dictionaries, studies, and other resources related to etymology. That way, you can expand your knowledge of the complex subject without paying lots of money to build your own collection of etymology books since academic books tend to be expensive.

- University libraries will probably have more etymology-related resources available than public libraries.

- This is also a great opportunity to delve into specific types of etymology that may interest you. For instance, you can get an etymology book associated with a specific language or dialect or with a particular field, like geography or medicine.

-

4

Do Internet research. A quick Internet search can yield tons of results about the etymologies of various words. You might even find some interesting discussion threads on the topic. You could also post a question to a forum site, like Quora, for more information.

- If you’re looking for more academic results, try using a site like Google Scholar.

-

5

Follow a related blog or podcast. There are many popular blogs and podcasts where you can read and listen to stories about etymology. Both offer a fun and informative way to keep up your hobby of studying etymology.

- For blogs, try the Oxford Etymologist, The Etyman Language Blog, or Omniglot Blog.

- For podcasts, try The Allusionist, Lexicon Valley, or The History of English.

Advertisement

-

1

Take a course for credit. Many colleges and universities offer traditional and online courses related to etymology. There will not be a broad array of related courses available, but there is likely to be one or two at most higher education institutions. The best place to look for classes related to etymology are in the Classics, English, and Linguistics departments.

- Keep in mind that you will have to be enrolled at a college or university in order to take a course through them. Most courses taken for credit will require you to be accepted as a student through a formal application process and to pay a tuition fee.

-

2

Apply for a linguistics degree program. No colleges or universities currently offer degrees specifically in etymology. However, many higher ed institutions do have Linguistics Departments that offer bachelor’s, master’s, and/or doctoral degrees. Getting a degree in Linguistics is the best preparation you can have for becoming a professional word historian.[15]

- The QS World University Rankings publishes an annual list of the top international programs in Linguistics according to their strengths in research and reputation along with their student and faculty ratio and diversity.[16]

- The QS World University Rankings publishes an annual list of the top international programs in Linguistics according to their strengths in research and reputation along with their student and faculty ratio and diversity.[16]

-

3

Get a related job or internship. Study etymology in a hands-on way. There isn’t too much call for professional etymologists these days. However, if you’d like to pursue a career in word history, the best way to go about it is to seek an editorial position with a quality dictionary, like the Oxford English Dictionary.[17]

- Dictionaries require constant updates to word definitions and etymologies, which means they always need new editorial staff. Search for job openings at dictionaries that interest you. They could be anything from the Oxford English Dictionary to Dictionary.com.

Advertisement

Add New Question

-

Question

Why is it important to know the etymology of words?

Katherine Demby is an Academic Consultant based in New York City. Katherine specializes in tutoring for the LSAT, GRE, SAT, ACT, and academic subjects for high school and college students. She holds a BA in History and Political Science from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a JD from Yale Law School. Katherine is also a freelance writer and editor.

Academic Tutor

Expert Answer

Besides the fact that it’s super interesting, knowledge of etymology will make it much easier to identify words you don’t know. It’s especially helpful when it comes to standardized tests, and reading.

-

Question

What’s the easiest way to find where a word comes from?

Katherine Demby is an Academic Consultant based in New York City. Katherine specializes in tutoring for the LSAT, GRE, SAT, ACT, and academic subjects for high school and college students. She holds a BA in History and Political Science from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a JD from Yale Law School. Katherine is also a freelance writer and editor.

Academic Tutor

Expert Answer

Look it up in an etymological dictionary! You can buy a hardcover copy, or you can just hop online and search a digital dictionary. That’s going to be the fastest way.

-

Question

What should I start studying first if I want to learn etymology?

Katherine Demby is an Academic Consultant based in New York City. Katherine specializes in tutoring for the LSAT, GRE, SAT, ACT, and academic subjects for high school and college students. She holds a BA in History and Political Science from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a JD from Yale Law School. Katherine is also a freelance writer and editor.

Academic Tutor

Expert Answer

Start by working through the super common prefixes and suffixes. Once you’ve identified one, you can make inferences about other words with the same prefix or suffix. For example, matri- comes from the Latin word mater, which means «mother.» So, once you know that you can immediately figure certain things out about maternity, matricide, matrimony, or matriarchal. They’re all related to motherhood or women!

See more answers

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

Video

-

Read! The more you read, the more words you see. When you learn and see these words used, you will recognize other words that look similar or are used similarly. This can be a great starting point for another quick etymology study.

-

Try looking up all sorts of words, from the anatomical («wrist, bicep, knee, digit» etc) to the zany such as slang words (but be aware that some, if they are too new, may not yet have made it into the dictionary).

Advertisement

-

Since etymology is not a perfect science, not all etymologies of a given word will be the same. Some of their roots and histories may even be disputed. Check out more than one etymological definition to see how different etymologists have interpreted a word’s history.

-

The internet contains many false etymologies and origins, so be sure that you’re doing research using an authoritative dictionary. An example is CANOE — the Committee to Assign Naval Origins to Everything (not a real committee!) — which gives an entirely spurious explanation as to the origins of «brass monkey weather.»

-

Because our written record of languages is incomplete and many languages do not have a written record, etymology is not a perfect science. It can only attempt to recreate the history of words based on the limited evidence that we have available.

Advertisement

References

About This Article

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 112,952 times.

Reader Success Stories

-

Simone Kaplan

May 14, 2019

«I am currently studying for a spelling bee. This helped me learn language patterns. Thank you very much!»

Did this article help you?

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow’s weekly email newsletter

Subscribe

You’re all set!

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«Etymologies» redirects here. For the work by Isidore of Seville, see Etymologiae.

Etymology ( ET-im-OL-ə-jee[1]) is the study of the origin and evolution of a word’s semantic meaning across time, including its constituent morphemes and phonemes.[2][3] It is a subfield of historical linguistics, and draws upon comparative semantics, morphology, semiotics, and phonetics.

For languages with a long written history, etymologists make use of texts, and texts about the language, to gather knowledge about how words were used during earlier periods, how they developed in meaning and form, or when and how they entered the language. Etymologists also apply the methods of comparative linguistics to reconstruct information about forms that are too old for any direct information to be available. By analyzing related languages with a technique known as the comparative method, linguists can make inferences about their shared parent language and its vocabulary. In this way, word roots in many European languages, for example, can be traced all the way back to the origin of the Indo-European language family.

Even though etymological research originated from the philological tradition, much current etymological research is done on language families where little or no early documentation is available, such as Uralic and Austronesian.

Etymology[edit]

The word etymology derives from the Greek word ἐτυμολογία (etumología), itself from ἔτυμον (étumon), meaning «true sense or sense of a truth», and the suffix -logia, denoting «the study of».[4][5]

The term etymon refers to a word or morpheme (e.g., stem[6] or root[7]) from which a later word or morpheme derives. For example, the Latin word candidus, which means «white», is the etymon of English candid. Relationships are often less transparent, however. English place names such as Winchester, Gloucester, Tadcaster share in different modern forms a suffixed etymon that was once meaningful, Latin castrum ‘fort’.

Diagram showing relationships between etymologically related words

Methods[edit]

Etymologists apply a number of methods to study the origins of words, some of which are:

- Philological research. Changes in the form and meaning of the word can be traced with the aid of older texts, if such are available.

- Making use of dialectological data. The form or meaning of the word might show variations between dialects, which may yield clues about its earlier history.

- The comparative method. By a systematic comparison of related languages, etymologists may often be able to detect which words derive from their common ancestor language and which were instead later borrowed from another language.

- The study of semantic change. Etymologists must often make hypotheses about changes in the meaning of particular words. Such hypotheses are tested against the general knowledge of semantic shifts. For example, the assumption of a particular change of meaning may be substantiated by showing that the same type of change has occurred in other languages as well.

Types of word origins[edit]

Etymological theory recognizes that words originate through a limited number of basic mechanisms, the most important of which are language change, borrowing (i.e., the adoption of «loanwords» from other languages); word formation such as derivation and compounding; and onomatopoeia and sound symbolism (i.e., the creation of imitative words such as «click» or «grunt»).

While the origin of newly emerged words is often more or less transparent, it tends to become obscured through time due to sound change or semantic change. Due to sound change, it is not readily obvious that the English word set is related to the word sit (the former is originally a causative formation of the latter). It is even less obvious that bless is related to blood (the former was originally a derivative with the meaning «to mark with blood»).

Semantic change may also occur. For example, the English word bead originally meant «prayer». It acquired its modern meaning through the practice of counting the recitation of prayers by using beads.

History[edit]

The search for meaningful origins for familiar or strange words is far older than the modern understanding of linguistic evolution and the relationships of languages, which began no earlier than the 18th century. From Antiquity through the 17th century, from Pāṇini to Pindar to Sir Thomas Browne, etymology had been a form of witty wordplay, in which the supposed origins of words were creatively imagined to satisfy contemporary requirements; for example, the Greek poet Pindar (born in approximately 522 BCE) employed inventive etymologies to flatter his patrons. Plutarch employed etymologies insecurely based on fancied resemblances in sounds. Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae was an encyclopedic tracing of «first things» that remained uncritically in use in Europe until the sixteenth century. Etymologicum genuinum is a grammatical encyclopedia edited at Constantinople in the ninth century, one of several similar Byzantine works. The thirteenth-century Legenda Aurea, as written by Jacobus de Varagine, begins each vita of a saint with a fanciful excursus in the form of an etymology.[8]

Ancient Sanskrit[edit]

The Sanskrit linguists and grammarians of ancient India were the first to make a comprehensive analysis of linguistics and etymology. The study of Sanskrit etymology has provided Western scholars with the basis of historical linguistics and modern etymology. Four of the most famous Sanskrit linguists are:

- Yaska (c. 6th–5th centuries BCE)

- Pāṇini (c. 520–460 BCE)

- Kātyāyana (6th-4th centuries BCE)

- Patañjali (2nd century BCE)

These linguists were not the earliest Sanskrit grammarians, however. They followed a line of ancient grammarians of Sanskrit who lived several centuries earlier like Sakatayana of whom very little is known. The earliest of attested etymologies can be found in Vedic literature in the philosophical explanations of the Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads.

The analyses of Sanskrit grammar done by the previously mentioned linguists involved extensive studies on the etymology (called Nirukta or Vyutpatti in Sanskrit) of Sanskrit words, because the ancient Indians considered sound and speech itself to be sacred and, for them, the words of the sacred Vedas contained deep encoding of the mysteries of the soul and God.

Ancient Greco-Roman[edit]

One of the earliest philosophical texts of the Classical Greek period to address etymology was the Socratic dialogue Cratylus (c. 360 BCE) by Plato. During much of the dialogue, Socrates makes guesses as to the origins of many words, including the names of the gods. In his Odes Pindar spins complimentary etymologies to flatter his patrons. Plutarch (Life of Numa Pompilius) spins an etymology for pontifex, while explicitly dismissing the obvious, and actual «bridge-builder»:

The priests, called Pontifices…. have the name of Pontifices from potens, powerful because they attend the service of the gods, who have power and command overall. Others make the word refer to exceptions of impossible cases; the priests were to perform all the duties possible; if anything lays beyond their power, the exception was not to be cavilled. The most common opinion is the most absurd, which derives this word from pons, and assigns the priests the title of bridge-makers. The sacrifices performed on the bridge were amongst the most sacred and ancient, and the keeping and repairing of the bridge attached, like any other public sacred office, to the priesthood.

Medieval[edit]

Isidore of Seville compiled a volume of etymologies to illuminate the triumph of religion. Each saint’s legend in Jacobus de Varagine’s Legenda Aurea begins with an etymological discourse on the saint’s name:

Lucy is said of light, and light is beauty in beholding, after that S. Ambrose saith: The nature of light is such, she is gracious in beholding, she spreadeth over all without lying down, she passeth in going right without crooking by right long line; and it is without dilation of tarrying, and therefore it is showed the blessed Lucy hath beauty of virginity without any corruption; essence of charity without disordinate love; rightful going and devotion to God, without squaring out of the way; right long line by continual work without negligence of slothful tarrying. In Lucy is said, the way of light.[9]

Modern era[edit]

Etymology in the modern sense emerged in the late 18th-century European academia, within the context of the wider «Age of Enlightenment,» although preceded by 17th century pioneers such as Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn, Gerardus Vossius, Stephen Skinner, Elisha Coles, and William Wotton. The first known systematic attempt to prove the relationship between two languages on the basis of similarity of grammar and lexicon was made in 1770 by the Hungarian, János Sajnovics, when he attempted to demonstrate the relationship between Sami and Hungarian (work that was later extended to the whole Finno-Ugric language family in 1799 by his fellow countryman, Samuel Gyarmathi).[10]

The origin of modern historical linguistics is often traced to Sir William Jones, a Welsh philologist living in India, who in 1782 observed the genetic relationship between Sanskrit, Greek and Latin. Jones published his The Sanscrit Language in 1786, laying the foundation for the field of Indo-European linguistics.[11]

The study of etymology in Germanic philology was introduced by Rasmus Christian Rask in the early 19th century and elevated to a high standard with the German Dictionary of the Brothers Grimm. The successes of the comparative approach culminated in the Neogrammarian school of the late 19th century. Still in the 19th century, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche used etymological strategies (principally and most famously in On the Genealogy of Morals, but also elsewhere) to argue that moral values have definite historical (specifically, cultural) origins where modulations in meaning regarding certain concepts (such as «good» and «evil») show how these ideas had changed over time—according to which value-system appropriated them. This strategy gained popularity in the 20th century, and philosophers, such as Jacques Derrida, have used etymologies to indicate former meanings of words to de-center the «violent hierarchies» of Western philosophy.

Notable etymologists[edit]

- Ernest Klein (1899-1983), Hungarian-born Romanian-Canadian linguist, etymologist

- Marko Snoj (born 1959), Indo-Europeanist, Slavist, Albanologist, lexicographer, and etymologist

- Anatoly Liberman (born 1937), linguist, medievalist, etymologist, poet, translator of poetry and literary critic

- Michael Quinion (born c. 1943)

See also[edit]

- Examples

- Etymological dictionary

- Lists of etymologies

- Place name origins

- Fallacies

- Bongo-Bongo – Name for an imaginary language in linguistics

- Etymological fallacy – Fallacy that a word’s history defines its meaning

- False cognate – Words that look or sound alike, but are not related

- False etymology – Popular, but false belief about word origins

- Folk etymology – Replacement of an unfamiliar linguistic form by a more familiar one

- Malapropism – Misuse of a word

- Pseudoscientific language comparison – Form of pseudo-scholarship

- Linguistic studies and concepts

- Diachrony and synchrony – Complementary viewpoints in linguistic analysis

- Surface analysis (surface etymology)

- Historical linguistics – Study of language change over time

- Lexicology – Linguistic discipline studying words

- Philology – Study of language in oral and written historical sources

- Proto-language – Common ancestor of a language family

- Toponymy – Branch of onomastics in linguistics, study of place names

- Wörter und Sachen – science school of linguistics

- Diachrony and synchrony – Complementary viewpoints in linguistic analysis

- Processes of word formation

- Cognate – Words inherited by different languages

- Epeolatry

- Neologism – Newly coined term not accepted into mainstream language

- Phono-semantic matching – Type of multi-source neologism

- Semantic change – Evolution of a word’s meaning

- Suppletion – a word having inflected forms from multiple unrelated stems

Notes[edit]

- ^ The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) ISBN 0-19-861263-X – p. 633 «Etymology /ˌɛtɪˈmɒlədʒi/ the study of the class in words and the way their meanings have changed throughout time».

- ^ Etymology: The history of a word or word element, including its origins and derivation

- ^ «Etymology». www.etymonline.com.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «etymology». Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ ἐτυμολογία, ἔτυμον. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ According to Ghil’ad Zuckermann, the ultimate etymon of the English word machine is the Proto-Indo-European stem *māgh «be able to», see p. 174, Zuckermann, Ghil’ad (2003). Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403917232.

- ^ According to Ghil’ad Zuckermann, the co-etymon of the Israeli word glida «ice cream» is the Hebrew root gld «clot», see p. 132, Zuckermann, Ghil’ad (2003). Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403917232.

- ^ Jacobus; Tracy, Larissa (2003). Women of the Gilte Legende: A Selection of Middle English Saints Lives. DS Brewer. ISBN 9780859917711.

- ^ «Medieval Sourcebook: The Golden Legend: Volume 2 (full text)».

- ^ Szemerényi 1996:6

- ^ LIBRARY, SHEILA TERRY/SCIENCE PHOTO. «Sir William Jones, British philologist — Stock Image — H410/0115». Science Photo Library.

References[edit]

- Alfred Bammesberger. English Etymology. Heidelberg: Carl Winter, 1984.

- Philip Durkin. «Etymology», in Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, 2nd edn. Ed. Keith Brown. Vol. 4. Oxford: Elsevier, 2006, pp. 260–7.

- Philip Durkin. The Oxford Guide to Etymology. Oxford/NY: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- William B. Lockwood. An Informal Introduction to English Etymology. Montreux, London: Minerva Press, 1995.

- Yakov Malkiel. Etymology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Alan S. C. Ross. Etymology, with a special reference to English. Fair Lawn, N.J.: Essential Books; London: Deutsch, 1958.

- Michael Samuels. Linguistic Evolution: With Special Reference to English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972.

- Bo Svensén. «Etymology», chap. 19 of A Handbook of Lexicography: The Theory and Practice of Dictionary-Making. Cambridge/NY: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Walther von Wartburg. Problems and Methods in Linguistics, rev. edn. with the collaboration of Stephen Ullmann. Trans. Joyce M. H. Reid. Oxford: Blackwell, 1969.

External links[edit]

Look up etymology in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Media related to Etymology at Wikimedia Commons

- Etymology at Curlie.

- List of etymologies of words in 90+ languages.

- Online Etymology Dictionary.

Where do new words come from? How do you figure out their histories?

An etymology is the history of a linguistic form, such as a word; the same term is also used for the study

of word histories. A dictionary etymology tells us what is known of an English word before it became the word entered

in that dictionary. If the word was created in English, the etymology shows, to whatever extent is not already

obvious from the shape of the word, what materials were used to form it. If the word was borrowed into English,

the etymology traces the borrowing process backward from the point at which the word entered English to the

earliest records of the ancestral language. Where it is relevant, an etymology notes words from other languages that

are related («akin») to the word in the dictionary entry, but that are not in the direct line of borrowing.

How New Words are Formed

An etymologist, a specialist in the study of etymology, must know a good deal about the history of English

and also about the relationships of sound and meaning and their changes over time that underline the reconstruction

of the Indo-European language family. Knowledge is also needed of the various processes by which words are created

within Modern English; the most important processes are listed below.

Borrowing

A majority of the words used in English today are of foreign origin. English still derives much of its vocabulary

from Latin and Greek, but we have also borrowed words from nearly all of the languages in Europe. In the modern

period of linguistic acquisitiveness, English has found vocabulary opportunities even farther afield. From the

period of the Renaissance voyages through the days when the sun never set upon the British Empire and up to

the present, a steady stream of new words has flowed into the language to match the new objects and

experiences English speakers have encountered all over the globe. Over 120 languages are on record as sources

of present-day English vocabulary.

Shortening or Clipping

Clipping (or truncation) is a process whereby an appreciable chunk of an existing word is omitted,

leaving what is sometimes called a stump word. When it is the end of a word that is lopped off, the process

is called back-clipping: thus examination was docked to create exam and gymnasium

was shortened to form gym. Less common in English are fore-clippings, in which the beginning of a

word is dropped: thus phone from telephone. Very occasionally, we see a sort of fore-and-aft

clipping, such as flu, from influenza.

Functional Shift

A functional shift is the process by which an existing word or form comes to be used with another

grammatical function (often a different part of speech); an example of a functional shift would be the development

of the noun commute from the verb commute.

Back-formation

Back-formation occurs when a real or supposed affix (that is, a prefix or suffix) is removed from a word to

create a new one. For example, the original name for a type of fruit was cherise, but some thought that word

sounded plural, so they began to use what they believed to be a singular form, cherry, and a new word was

born. The creation of the the verb enthuse from the noun enthusiasm is also an example of a

back-formation.

Blends

A blend is a word made by combining other words or parts of words in such a way that they overlap (as

motel from motor plus hotel) or one is infixed into the other (as chortle from

snort plus chuckle — the -ort- of the first being surrounded by the ch-…-le

of the second). The term blend is also sometimes used to describe words like brunch, from

breakfast plus lunch, in which pieces of the word are joined but there is no actual overlap. The

essential feature of a blend in either case is that there be no point at which you can break the word with everything

to the left of the breaking being a morpheme (a separately meaningful, conventionally combinable element) and

everything to the right being a morpheme, and with the meaning of the blend-word being a function of the meaning of

these morphemes. Thus, birdcage and psychohistory are not blends, but are instead compounds.

Acronymic Formations

An acronym is a word formed from the initial letters of a phrase. Some acronymic terms still clearly show their

alphabetic origins (consider FBI), but others are pronounced like words instead of as a succession of

letter names: thus NASA and NATO are pronounced as two syllable words. If the form is written

lowercase, there is no longer any formal clue that the word began life as an acronym: thus radar (‘radio

detecting and ranging’). Sometimes a form wavers between the two treatments: CAT scan pronounced either like

cat or C-A-T.

NOTE: No origin is more pleasing to the general reader than an acronymic one. Although acronymic etymologies are

perennially popular, many of them are based more in creative fancy than in fact. For an example of such an alleged

acronymic etymology, see the article on posh.

Transfer of Personal or Place Names

Over time, names of people, places, or things may become generalized vocabulary words. Thus did forsythia

develop from the name of botanist William Forsyth, silhouette from the name of Étienne de Silhouette, a

parsimonious French controller general of finances, and denim from serge de Nîmes (a fabric made

in Nîmes, France).

Imitation of Sounds

Words can also be created by onomatopoeia, the naming of things by a more or less exact reproduction of the

sound associated with it. Words such as buzz, hiss, guffaw, whiz, and

pop) are of imitative origin.

Folk Etymology

Folk etymology, also known as popular etymology, is the process whereby a word is altered so as to

resemble at least partially a more familiar word or words. Sometimes the process seems intended to «make sense of» a

borrowed foreign word using native resources: for example, the Late Latin febrigugia (a plant with medicinal

properties, etymologically ‘fever expeller’) was modified into English as feverfew.

Combining Word Elements

Also available to one who feels the need for a new word to name a new thing or express a new idea is the very

considerable store of prefixes, suffixes, and combining forms that already exist in English. Some of these are native

and others are borrowed from French, but the largest number have been taken directly from Latin or Greek, and they

have been combined in may different ways often without any special regard for matching two elements from the same

original language. The combination of these word elements has produced many scientific and technical terms of Modern

English.

Literary and Creative Coinages

Once in a while, a word is created spontaneously out of the creative play of sheer imagination. Words such as

boondoggle and googol are examples of such creative coinages, but most such inventive brand-new

words do not gain sufficiently widespread use to gain dictionary entry unless their coiner is well known enough so

his or her writings are read, quoted, and imitated. British author Lewis Carroll was renowned for coinages such

as jabberwocky, galumph, and runcible, but most such new words are destined to pass in

and out of existence with very little notice from most users of English.

An etymologist tracing the history of a dictionary entry must review the etymologies at existing main entries and

prepare such etymologies as are required for the main entries being added to the new edition. In the course of the

former activity, adjustments must sometimes be made either to incorporate a useful piece of information that has

been previously overlooked or to review the account of the word’s origin in light of new evidence. Such evidence

may be unearthed by the etymologist or may be the product of published research by other scholars. In writing new

etymologies, the etymologist must, of course, be alive to the possible languages from which a new term may have

been created or borrowed, and must be prepared to research and analyze a wide range of documented evidence and

published sources in tracing a word’s history. The etymologist must sift theories, often-conflicting theories of

greater or lesser likelihood, and try to evaluate the evidence conservatively but fairly to arrive at the soundest

possible etymology that the available information permits.

When all attempts to provide a satisfactory etymology have failed, an etymologist may have to declare that a word’s

origin is unknown. The label «origin unknown» in an etymology seldom means that the etymologist is unaware of various

speculations about the origin of a term, but instead usually means that no single theory conceived by the etymologist

or proposed by others is well enough backed by evidence to include in a serious work of reference, even when qualified

by «probably» or «perhaps.»

Published on: 02 July 2020

What’s in a word? For author and linguist Patrick Skipworth, the hidden histories in our everyday conversation inspired him to write a book all about the many weird and wonderful languages we use.

Every word contains a hidden story about the people who first spoke it and the place it originated from. For linguists, peeling back these layers to reveal the secrets inside is one of the thrills of studying languages. It can be a window on the past, present and future, and can sometimes succeed where historical sources fail. In Literally: Amazing Words and Where They Come From, I took a closer look at the stories behind twelve English words. I aimed to cover as diverse a group of topics and origins as I could in just a dozen words, from scientific history to the many places and languages English has had contact with through colonialism. In each case, the story of the word has been depicted in a magical style by illustrator Nicholas Stevenson to communicate the origin through imagery.

Accuracy is essential when working on a children’s book, so how can we be sure of these etymologies, some of which point back thousands of years? For English, the OED and its skilled lexicographers are a good place to start, or you could try Once Upon A Word by Jess Zafarris for an engaging etymological dictionary. But how are these origins understood in the first place?

Some historical sources can direct us straight to the origin of a word. Eponyms, words with their origins in people’s, places’ or things’ names, can be a fascinating area to use this approach. Often the subject in question is well documented – after all, they were well known enough to have their name become a word in itself. ‘Sideburns’ is a fun example. We can confidently say it arises from the national sensation which was the American Civil War general Ambrose Burnside’s impressive facial hair, and we can see linguistic mischief at play in the switching around of ‘burn’ and ‘side’ to match the ‘side-whiskers’ also popular at the time. Sometimes the origin story is clear: Mausolus was an ancient Greek ruler who built an enormous mausoleum; Ned Ludd smashed textile machinery and inspired the Luddite movement; and John Duns led a philosophical group of ‘dunces’, who were ridiculed by Protestants centuries later.

Some eponyms present stories that are harder to unravel. The journey from Étienne de Silhouette, 18th-century French finance minister, to ‘silhouette’ in English connects pre-Revolution politics, economics and artistic trends – it’s still not entirely agreed how the word entered into common usage.

Historical records can also point us to the creation of words. Many linguistic innovations are hard to track because they arise organically, but new words are thought up deliberately all the time too, particularly in science and technology. ‘Vaccination’ was coined by British doctor Edward Jenner when developing his smallpox vaccine from the milder cowpox disease. The virus’s scientific name was variolae vaccinae, ultimately from Latin vaccinus ‘from a cow’. It’s intriguing to watch a word take on a life of its own, and to think whether Jenner considered that vaccinus would spread around the world (look at Japanese wakuchin ‘vaccine’, for example).

But sometimes the historical record isn’t enough for us to follow the threads back to the origin of the word, and this is where the most interesting etymological tool comes into play: reconstruction. We know that groups of languages can be related and share a common origin. French and Italian, for example, have remarkably similar grammatical features and basic vocabulary. Following this idea backwards, we can ‘reconstruct’ language when we don’t have a historical record. When applied correctly, this powerful tool can reveal lost histories. It’s also the methodology (the ‘comparative method’) which gives us the most significant chunk of etymologies for many languages, in particular fundamental vocabulary such as numbers or pronouns with origins far off in the past thousands of years ago, before written records existed.

How can I find the origin of a word?

Firstly, you’ll need some languages and historical records. That’s because you’ll be working backwards from your chosen word and ‘undoing’ all the linguistic changes as they happen in reverse, and the simplest way to find these changes is to compare related languages and historical sources from different times and places. Eventually you’ll return to a ‘proto-language’ – an unrecorded language that must theoretically have existed to lead to the recorded languages we do have.

How will my word have changed over time?

Usually these are sound changes. For example, a particular sound might change if it occurs between two particular consonants, or in a particular syllable position. The helpful thing about sound changes is that experiment has shown that they eventually occur everywhere – as long as the conditions are correct no word gets left out. So if a sound change happens once (or ideally a few times to be sure) at around the same time, then we can apply it in reverse to other words too. If we see ‘up’ changing to ‘op’ and ‘cup’ to ‘cop’, it would be reasonable to reconstruct ‘pup’ as the origin of ‘pop’. This simple idea is the key to reconstruction.

It’s through reconstruction that we can look at languages across the globe and show connections going back thousands of years. Take numbers, for example. By applying sound changes in reverse we can connect English five, Dutch vijf, Latin quinque, Russian pjat, Armenian hing, Hindi paanch, as well as ‘fist’, ‘punch’ (the drink), ‘Pentecost’ and many others to a proto-form, *penkwe (reconstructed words are indicated with an asterisk). Entire vocabularies containing hundreds of words from proto-languages (along with grammar) have been reconstructed this way.

For Literally, I am grateful for the support of a former colleague at Leiden University in the Netherlands where I studied linguistics. Linguistics is all about sharing research and knowledge – no individual alone could be expected to hold the amount of data and theory needed to study languages. It’s this sharing of information that leads to important discoveries, and it’s never too late to start studying languages and join the conversation.

Follow Patrick on Twitter here.