The One Word

Why is it the it has so much power and can do so much? One word can save people, it can make you shead a tear and wish for it. It can make you strive for a harder goal and succeed. When you give up and lose it you stop and die alittle but then you think of all the good things that you are letting go, then it comes back even stronger than ever. This one word can have you saying ‘yes I can do it! ‘ And then you run head first. This small litte four letter word can bring the scaredest of kittens in a the world to become the strongest lion any were else. This word has saved and will save millions of people, never lose it for it will be the most vouluable thing you have. This one word is hope, hope can lead a nation. Hope can make you fight for what you need, hope will leave you the best person you can ever be. My time is lost for it but your time has just only begun do not give up your hope!

Wednesday, September 19, 2012

“In effect the single word is a new reading process; like electricity — instant and continuous.”

A really perfect poem has an infinitely small vocabulary.

—Jack Spicer, “Second letter to Federico García Lorca”

Writing in 1961, at the founding of the Oulipo (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle) movement, Raymond Queneau and François Le Lionnais, two of France’s most significant postwar literary experimentalists, wondered to one another “how few words can make a poem?”

According to Le Lionnais, this question would preoccupy the two until Queneau’s death 15 years later. Even in 1976, they doubted that a poem could be constructed from fewer than several words. Perhaps because their backgrounds were not primarily in experimental poetry or postwar art (Le Lionnais was a mathematician and Queneau primarily an editor and novelist), the two oddly overlooked concrete poetry, a form of visual poetry that uses the arrangement of words to convey meaning. The two also seemed unaware of the work of Aram Saroyan, whose mid-1960s poems explored and broke the limits proposed by Queneau and Le Lionnais.

Though the Oulipo’s founders may have been underinformed about concrete poetry, their skepticism is telling: Setting aside concrete poetry in the 1950s, it was not until the 1960s with the contemporaneous emergence of pop art, minimalism, and conceptual art that a single word or letter could be recognized as a poem.

The one-word poem may in fact have rapidly reached the height of its popularity in late 1967 with the final issue of Ian Hamilton Finlay’s journal Poor. Old. Tired. Horse. In July of that year, Finlay wrote to Saroyan — then only 24, but a leading practitioner of the form — that he intended to put together an entire issue of P.O.T.H. devoted to one-word poems:

the idea being that the poem consists of one word and a title. These are to be thought of as 2 straight lines, which make a corner (the poems will have form); while the paradox of these corners is, that they are open in all directions. This is because we can’t have whole-world poems (we haven’t got one), but at the same time we should not despair of something with corners, such as making them, and opening them up.

As can immediately be discerned from Finlay’s letter, the rubric “one-word poem” is slightly misleading. All of the poems included in the issue featured a title, and most of the titles were longer than a single word. Following Finlay’s lead, I too consider as one-word poems not merely a single word in isolation on the page, but a single word repeated per poem or per page (or other unit of publication) that is repeated (in whole or in part) as a series. This expansive definition would include many notable concrete poems — for instance, Eugen Gomringer’s “silencio” or Finlay’s “ajar” or Mary Ellen Solt’s “Zinnia” — and my own rough estimate is that perhaps as many as 10 percent of concrete poems are primarily constructed of a single word. Saroyan, however, understood himself to be writing not as a concrete poet, but as a minimal poet.

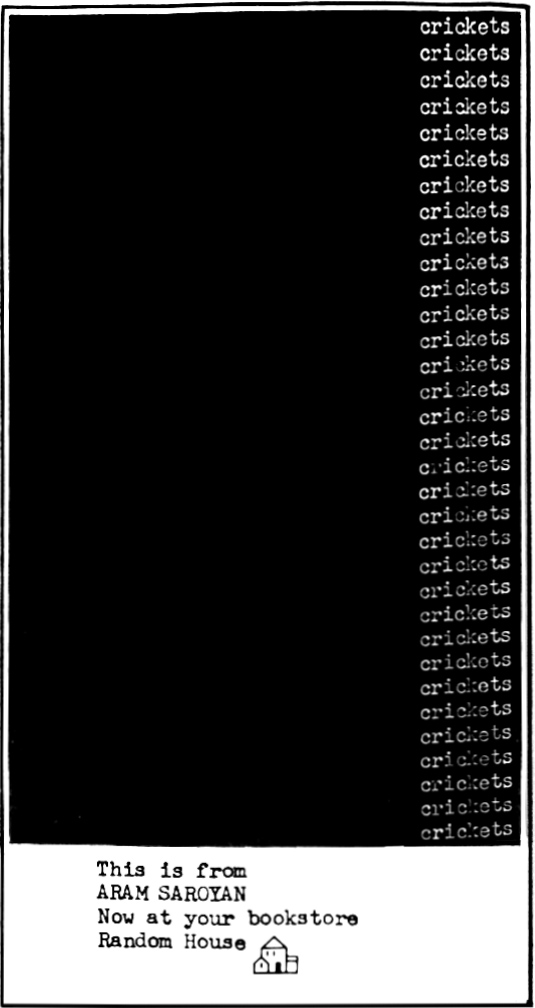

Perhaps the greatest influence on Saroyan’s minimal poems was Louis Zukofsky, to whom Saroyan had been introduced by another strong influence, Robert Creeley, in 1964. Creeley’s poems also became more minimal in the late 1960s, but never so minimal as a single word or a single word repeated. Zukofsky provided the epigraph for Saroyan’s journal Lines, and he may have partially inspired Saroyan’s “lighght,” as well as his “crickets / crickets / crickets . . .” Saroyan wrote three distinctly different cricket poems, two of which were recorded for LP.

The column version of “crickets” would go on to become a signature poem of Saroyan’s, as evidenced by a 1968 Paris Review advertisement that found Saroyan at the peak of his fame. The column of “crickets” (like “not a cricket”) should be listened to in order to be appreciated fully. In the 1967 recording, the one word is repeated by Saroyan for 80 seconds, and it evokes that of which it speaks by onomatopoeia.

According to the author, the poem “was written in the spring of 1965 in an apartment building on East 45th in New York City, proving that crickets are powerful creatures, capable of penetrating New York City itself.” Interestingly, Saroyan repeats the word “crickets” about 33 times per minute — not far off from the 30 chirps per minute produced by the North American field cricket. (The speed at which a cricket chirps is determined by species and temperature — it is even possible, following Dolbear’s Law, to determine the temperature outdoors by counting the frequency of cricket chirps.)

The poem may well have been influenced by a poem from Zukofsky’s “All,” first published in 1965. Zukofsky’s poem — a mere 19 words in 16 lines — begins with “Crickets’ / thickets” and ends with “are crickets’ / air.” Saroyan in fact recalls visiting Zukofsky with Clark Coolidge in New York City not long after the column of crickets had been published in Lines six in November 1966, he tells me: “Louis mentioned the poem right away, saying something like ‘Alright, but what about’ and here he switched into mellifluous recitation — ‘crickets’ / thickets // light, delight.’ He didn’t go on long but it was clear I had gone too far for his tastes.”

Saroyan’s isolation of the single word had powerful effects: It denarrativized and decontextualized language, and it placed the word in stark relief.

Saroyan’s other two contemporaneous cricket poems play on the sonic and visual properties of the word in other ways. Also a single column, “crickets / crickess / cricksss . . .” removes one letter from the word for eight lines and then re-adds a letter for each line. The word “cricket” disappears and reappears visually among the additional s’s. Saroyan’s “not a cricket,” by contrast, plays with a sonic and semantic paralipsis:

Although it was not written specifically for The Dial-a-Poem Poets, that recording is crucial to understanding the poem. Saroyan reads the poem slowly as if it were a radio or telephone announcement of the time, and “ticks a / clock” sounds very much like “six o’clock” (perhaps in reference to the iconic chimes of Big Ben that have been broadcast worldwide daily by the BBC at six o’clock since 1924). Although “ticks a” half-rhymes with “cricket,” it is not the same word, as in the other “crickets” poems. Moreover, the poem plays a trick similar to Magritte’s “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” or George Lakoff’s “Don’t Think of an Elephant”— it negatively conjures something, as if to suggest a cricket doesn’t make a sound like a clock. Or perhaps there is a silence so deep that only a clock can be heard.

“crickets” and “not a cricket” can be usefully compared to another contemporaneous poem by Saroyan: simply the word “tick” centered on two facing pages. Like the crickets poems, it is onomatopoeic, and in fact may sound more like a clock than the conventional English “tick-tock” or the French “tic-tac” (the Italian candy, introduced in 1969, is said to have taken its name from the sound of the candies rattling in their container). A clock does not have two sounds that alternate every other second; it has one.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Ih5WSAu002du002dMw

“Tick” in this context will bring a clock to mind for most readers, but here again the lack of context could be suggestive. Tick as a noun might suggest two insects. Or it might suggest another meaning of “tick” as a verb, such as to tick something off a list. Saroyan’s use of the facing pages is ingenious, however, and indicates the tick as a unit of time, although the poem (as Saroyan suggested was his intent with the minimal poems) may not involve any durational reading process, as one might see both ticks stereoscopically at once. The poem originally appeared in the experimental literary magazine 0 To 9 and would not have been possible to include in Saroyan’s three main books of minimal poetry, as these all had poems printed on the right-hand pages only. Saroyan’s isolation of the single word had powerful effects: It denarrativized and decontextualized language, and it placed the word, typically a noun, in stark relief. In a letter which accompanied the poem, Saroyan wrote to artist Vito Acconci in September 1967 that

I’ve discovered that the best work I can do now is to collect single words that happen to strike me and to type each one out in the center of a page. The one word isn’t “mine” but the one word in the center of the page is. Electric poems I call them (in case anyone starts throwing Concrete at me)—meaning that isolated of the reading process—or that process rendered by the isolation instant—each single word is structure as “instant, simultaneous, and multiple” as electricity and/or the Present. In effect the single word is a new reading process; like electricity—instant and continuous.

Saroyan’s version of minimal writing energized Vito Acconci to turn in the opposite direction, toward a maximal style that likewise can present extreme difficulties of interpretation. Acconci’s late-60s writing included in 0 To 9 especially emphasizes the contrasting styles. “tick . . . tick” is in fact embedded within a long and elaborate Acconci poem called “ON” that took up much of issue three of 0 To 9. Acconci describes his all-or-nothing reaction to Saroyan’s poems:

In the late Sixties, when I called myself a poet, Aram was the poet I envied. Because you couldn’t be sure if he was fooling or if he had really gotten to all there is to get. Because while the rest of us tried to be verbs, like everybody told us to do, he had the nerve to stop at nouns. Because he took a deep breath and willed himself into the self-confidence of naming. Because it wasn’t “nouns,” it was “noun,” only one noun, because he boiled it all down to one. Because then he let himself go, he let himself stutter, he let the one go and let the one double and go out of focus: while the rest of us ran for our lives all over the place and over the page, his noun shimmered and breathed and trembled and moved—shh! softly, softly—from within.

As Acconci well knew, many of the one-word poems were the result of felicitous typos or language appropriated from the ambient surroundings; and in fact, in many cases Saroyan’s method of appropriating text and sound was similar to Acconci’s, although Saroyan worked in smaller units. But Acconci also ascribed to Saroyan’s writing a powerful interiority because he attempted to avoid such interiority in his own dense, informatic writing of the late 1960s and early 70s.

Many of Saroyan’s poems have a more interesting media history than is generally recognized. Saroyan’s most famous one-word poem, “lighght,” for instance, became famous (or infamous) several years after it was in written in the fall of 1965, and was first published as a 24″ × 36″ poster by Brice Marden in early 1966. As part of a set of five Electric Poems posters, lighght (the title is italicized when it is considered as an artwork) was printed in yellow, as if to suggest sunlight. Around the same time, it was printed in red in Saroyan’s self-published “Works,” which contained 24 minimal poems.

It was not until 1970 that the poem was to gain widespread notoriety, when Congressman William Scherle decried the poem on the floor of Congress, noting that the National Endowment for the Arts had spent $107 per letter on the poem. In retrospect, the controversy over “lighght” was an opening salvo in the battle over NEA funding that continues to this day. As in the reaction to so many works of avant-garde and minimal art, the resistance to this work lay in the supposed lack of skill or effort to create it.

Although he had not yet read Marshall McLuhan when he wrote the poem, Saroyan drew on McLuhan in offering a reading of the poem: “Why only a single word—and a misspelled word at that? Let me stick with McLuhan, who wrote that the electric-television era of communication has three fundamental characteristics: (1) It is instant. 2) It is simultaneous. 3) It is multiple,” he wrote in an account of the controversy for Mother Jones. “A one-word poem is, in its own way, a structure that embodies all of McLuhan’s essential characteristics and hence reflects the unique reality of the time during which it was made.”

“A one-word poem is, in its own way, a structure that embodies all of McLuhan’s essential characteristics and hence reflects the unique reality of the time during which it was made.”

Saroyan seems to allude to the opening pages of “Understanding Media” in which McLuhan claims, “The electric light is pure information,” and that “the ‘message’ of any medium or technology is the change of scale or pace or pattern that it introduces in human affairs.” McLuhan’s media-deterministic account of television and global telecommunication is in many respects a good fit for a defense of minimalism, particularly given that McLuhan emphasizes scale and speed as important components of communication and expression.

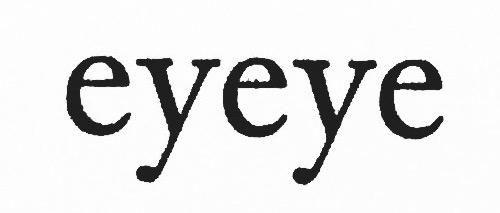

But “lighght” may not be as void of content as it first appears. The poem may look like a felicitous typo (like “eyeye”), but the poem was not the result of an accident. One possible inspiration for the poem might even have been Zukofsky’s “crickets’ / thickets // light / delight.” In the version of that poem published in 1965, the words “light” and “delight” align vertically so that if one were to delete the “deli,” the result could be “lighght.” Saroyan himself has suggested some possible implications of his poem, claiming, as he does in his collection of essays and reviews, “Door to the River,” that the effect of the poem is “to render light itself more palpable, as if the word holds the phenomenon.” A number of commentators have noted that the poem evokes vibrating light waves. “Light” can be a noun, verb, or adjective in English. The extra “gh” is unpronounceable and intangible. Or perhaps one might elongate the word and stretch out the i sound. In practice, I’ve generally heard the poem read aloud as a list of letters, L-I-G-H-G-H-T, rather than as a single syllable — thus turning the poem into seven syllables.

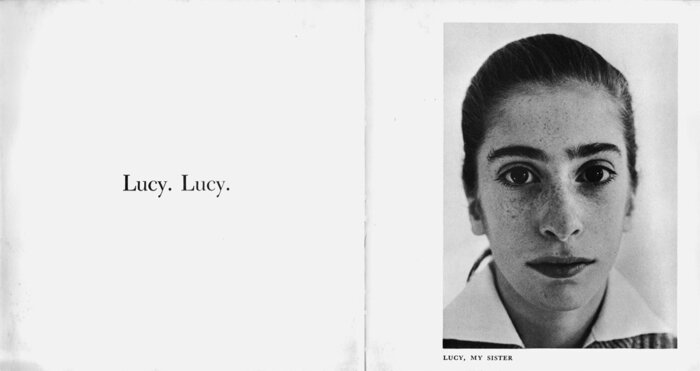

Saroyan conceived his one-word poems as being fundamentally photographic, as his 1970 “Words & Photographs” made more clear than the earlier minimal books. Having worked as photographer Richard Avedon’s assistant as a high school student, Saroyan in this book juxtaposed verso poems with recto photographs. Like much of Saroyan’s later work, “Words & Photographs” is largely autobiographical and begins with photographs of his family. The first image/poem in the book is of his sister, whose name, Lucy, is cognate with “light.” The back-cover text seemingly alludes to this when it claims: “The combination of photo and poem is at times haunting and cryptic, at times witty, and always lucid.” Unlike his more austere earlier one-word poems, the poems in “Words & Photographs”are each punctuated with periods, as if to create a one-to-one mimetic correspondence of word and image. In common with many one-word poems, the text is effectively metonymic — metaphor and narrative are precluded. The centered text on the left page symmetrically mirrors the image on the right, and the repetition gives the sense of an infinite echo.

“lighght” may look like a felicitous typo but the poem was not the result of an accident.

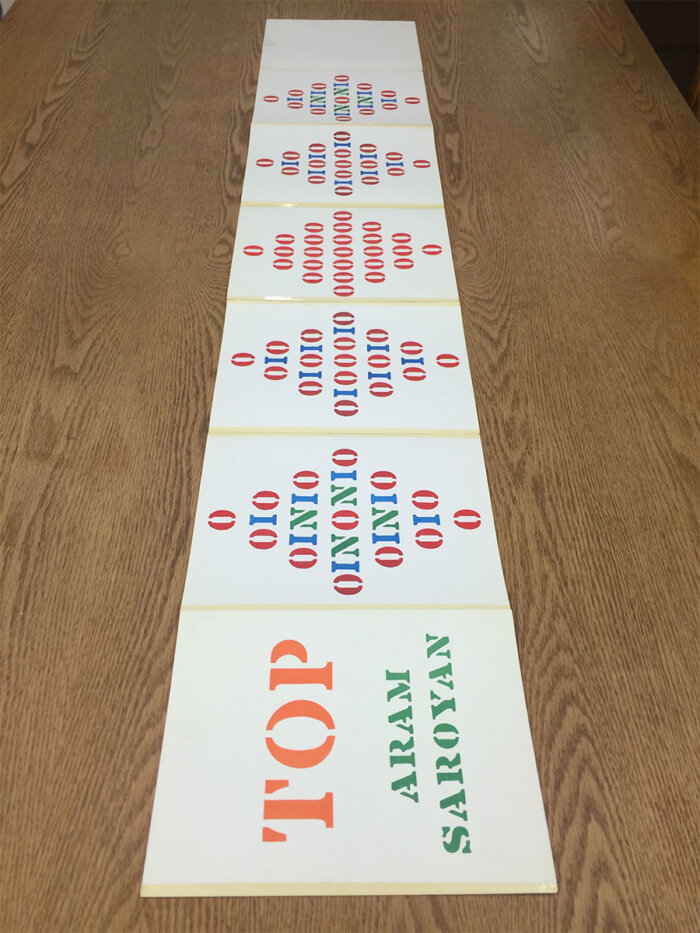

Not all of Saroyan’s minimal poems were so austerely black and white as they are in his early books or in “Complete Minimal Poems.” Produced in the summer of 1965, “TOP”(spoiler alert) consists of the title and a single word that can be difficult to distinguish at first (and thus “TOP”seems to qualify as a one-word poem, according to Finlay’s definition). The one word, which never appears all at once on any single panel, is simply “GOING.”

“TOP” is almost a work of op art in its deployment of the diamond shape of a spinning top. Its use of the stencil form gives the panels an almost militaristic sensibility, and a number of the panels contain only O’s and I’s, which in the stencil format can easily be seen as zeros and ones, suggesting binary code. The spatial deployment of letters and colors in “TOP” is ingenious: The center panel of the front (or top) side consists only of red O’s (or zeros), as if to suggest that the top has reached maximum speed and has become blurred in our vision. I included a spoiler alert above because I think “TOP” should be read with fresh eyes in order to be appreciated, as there is generally a delay between a reader’s apprehension of the letterforms on the page and recognition of the specific word. The poem can’t help but invoke the cliché of “going, going, gone,” and even if it only takes 30 seconds to cognize “going,” that delay will almost surely be a component of a reading process that all too soon will be gone.

Toward the end of Saroyan’s minimal phase, in late 1967 and early 1968, his writing became sparser and more conceptual. “©1968”— or “Ream” — is merely a blank 500-page ream of paper. It might also be read as a one-word poem whose one word is implied but never directly stated. As a farewell to minimal poetry, the gesture could hardly be more perfect. “©1968,” about which Craig Dworkin writes extensively in “No Medium,” a book comprising readings of ostensibly “blank” works, adopts the standard medium of the typewriter, while seemingly rejecting content altogether. The scale of the ream is infinitely out of proportion to its contents — and yet “©1968”can be understood as a sculptural object as well as a work of conceptual literature. The title makes the object Saroyan’s intellectual property, and yet there is nothing to protect. The author’s assertion of rights mocks an entire system of authorship at the same time that it reinscribes it by including only the author’s name and copyright. The blank pages could be the potential work of everyone and no one — except for the simple assertion of Saroyan’s role.

Saroyan’s minimal poems offer a loving parody of both fame and the graphomania that often accompanies literary fame. At the same time that Saroyan was assembling his three main collections of minimal poems, a remarkable cultural development was taking place, as documented by Roger Gastman in “Wall Writers”:

while you can’t tell exactly when graffiti started, we’re able to put a fairly accurate date on when it changed in a way that would transform city life, public transit, public art, and ultimately visual art the world over. In Philadelphia and New York City, roughly contemporaneous with the 1967 Summer of Love, was when graffiti began to change: The idea became to write your name or moniker all over the city, in a stylish way, again and again and again, with a goal of street fame and self-expression. That same basic idea basically defines modern graffiti.

There is no direct relation between Saroyan’s practices and those of graffiti writers, nor is there any indication that Saroyan was aware of graffiti at the time. But a loose comparison can be suggestive: Both Saroyan and the graffiti writers were engaged in more or less noncommercial art practices. The book “Aram Saroyan,” not unlike a graffiti tag, established his name within a subculture — in part by refusing The Great American Novel type of book that might be expected of the son of a famous writer whose fame had faded, but whose life remained defined by an extreme dedication to his writing.

Saroyan’s minimal poems offer a loving parody of both fame and the graphomania that often accompanies literary fame.

The younger Saroyan had seen up close the effects of fame all his life, and in the spring of 1967, the interview of Jack Kerouac that he conducted, with Ted Berrigan and Duncan McNaughton, offered a particularly strong cautionary tale. Not long after, Saroyan auditioned for the lead role in Mike Nichols’s “The Graduate,” but walked away in order to pursue his writing. The minimal poems were, in their way, the ultimate renunciation of the role of author as oracle and performer. For Dworkin, Saroyan’s early books can be read “as scenes in a sorry family drama,” and yet “each of these early books asserts Aram Saroyan’s own right to be identified with the typewriter, however long the shadow cast by his celebrity father’s own identification with the machine.” “[F]or all their whimsical irony,” Dworkin concludes, “the critiques [these books] wager are bought at the cost of insisting on literary value, not negating it.”

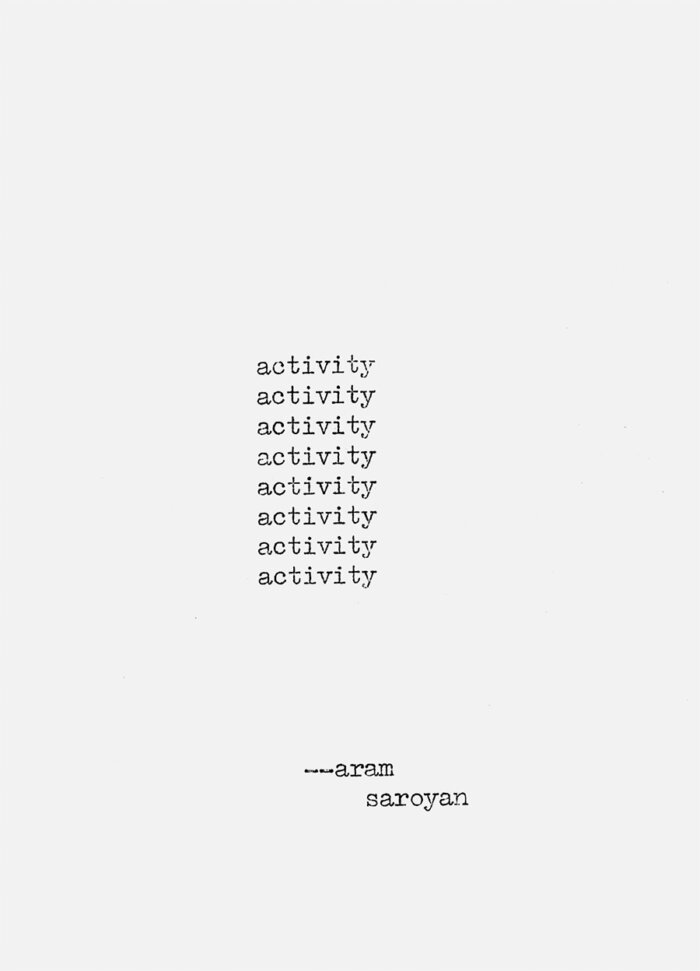

A little-known 1971 poem (not collected in “The Complete Minimal Poems”) gives a good sense for how the one-word poem can be both banal and profound. The poem is simply the eight letters of the word “activity” repeated eight times (possibly vaguely evoking the Beatles’ song “Eight Days a Week”). Like the obsessive repetitive emptiness of Vito Acconci’s “Read This Word” or Hanne Darboven’s “Words,” the poem goes nowhere and everywhere.

Life itself can be described as an activity — or it could be described as the sum of our activities. “Activity” is a measure of vitality, but “activities” in the plural can suggest a routinization or lack of differentiation, as in a sentence like “I can hardly keep up with all of my child’s activities.” The repeated “activity” invites metonymic substitution: The poem could be rewritten as “writing / sleeping / smoking / seeing,” etc. — although for me the poem would seem to ask to be readself-reflexively as a commentary on the activity of writing.

As someone who writes and who studies writers, I often wonder why writers write so much. In many cases, the activity itself must give satisfaction, since conventional utilitarian considerations cannot possibly pertain. In other cases, the activity must seem like an onerous burden. The one-word poem inverts the graphomanic impulse — but it also plunges us into an abyss of linguistic vagueness, jolting us from a passivity in which we suppress the mysteriousness of language: where letters disappear into words and words disappear into sentences and sentences disappear into books and books consume their authors. Here, for the active reader, that process might be reversible.

Paul Stephens is the editor of the journal Convolution, and the author of “The Poetics of Information Overload: From Gertrude Stein to Conceptual Writing” and “absence of clutter: minimal writing as art and literature,” from which this article is adapted.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

One Word is Too Often Profaned

ONE word is too often profaned

For me to profane it,

One feeling too falsely disdain’d

For thee to disdain it.

One hope is too like despair

For prudence to smother,

And pity from thee more dear

Than that from another.I can give not what men call love;

But wilt thou accept not

The worship the heart lifts above

And the Heavens reject not:

The desire of the moth for the star,

Of the night for the morrow,

The devotion to something afar

From the sphere of our sorrow?

Published in Posthumous Poems, 1824.

«One Word Is Too Often Profaned» is a poem by Percy Bysshe Shelley, written in 1822 and published in 1824 (see 1822 in poetry).

Background[edit]

The poem was intended for Jane Williams. It expresses Shelley’s deep and genuine devotion for her.

Shelley met Jane Williams and her lover, Edward Ellerker Williams, in Pisa sometime in 1821. The Williams befriended Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley, and they all frequently met Lord Byron, who also lived in Pisa at that time.

Shelley developed a very strong affection towards Jane Williams and addressed a number of poems to her. In most of these poems, Shelley projects his love for Jane in a spiritual and devotional manner. This poem is an example of that. Shelley’s affection towards Jane was known to Edward Williams and also to Mary Shelley. But since Shelley always projected this relationship in a platonic manner, Williams and Mary Shelley were not afflicted by jealousy regarding this relationship. In fact, Mary Shelley was quite fond of Jane and Edward Williams, and Shelley enjoyed Edward’s company too. Shelley and Edward Williams drowned while on a boating trip on 8 July 1822.[1]

Shelley wrote a number of poems devoted to Jane including With a Guitar, To Jane, One Word is Too Often Profaned, To Jane: The Invitation, To Jane: The Recollection and To Jane: The Keen Stars Were Twinkling.[2]

In One Word is Too Often Profaned, Shelley rejects the use of the word Love to describe his relationship with Jane. He says that this word has been so often profaned or misused that he will not use it to describe this relationship. He then goes on to say that the usage of this word may be rejected by Jane herself and that his feelings for her are too pure to be falsely disdained.

He uses the word pity and states that the feeling of pity from Jane is more dear than love from any other woman. At this point he starts elevating Jane’s stature to something larger than other women of the world. Shelley chooses to employ the word worship to describe his devotion towards Jane. He states that the feeling of worship that he feels towards Jane is something that is uplifting and is also moral (and the heavens reject not).

He describes the nature of his devotion: it is the devotion of a moth for a star or what the night feels towards the next morning. He describes his devotion as something that lies beyond worldly existence and strife (the sphere of our sorrow).

Shelley uses the sentence I can give not what men call love which shows that he himself is not averse to the use of the word love but because it has been misused often by men everywhere to describe ordinary and worldly feelings, he will not use this word for Jane.

The metrical feet used in the poem are a mixture of anapests and iambs. The first line of each couplet contains three accents and the second line contains two.[3]

This poem has at times been printed with the titles To — and Love.

The poem was published in London in 1824 in the collection Posthumous Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley by John and Henry L. Hunt.

References[edit]

- ^ Symonds, John Addington. «Percy Bysshe Shelley». Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Shelley, Percy B. «Complete Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley». Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Fowler, J.H (1904). Notes to Palgrave’s Golden Treasury of Songs and Lyrics. London: Macmillan and co. OCLC 68137444.

Sources[edit]

- Fowler, John Henry. Notes to Palgrave’s Golden Treasury of Songs and Lyrics. Books I-IV. London: Macmillan and Company, 1904.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. The Selected Poetry and Prose of Shelley. Ware, Hertfordshire, UK: The Wordsworth *Poetry Library, 2002.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. The Complete Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley. New York: The Modern Library, 1994.

External links[edit]

- LibriVox audiorecording, Track 20, Shelley: Selected Poems and Prose.

- Posthumous Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley. 1824.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, poet to ‘One Word Is Too Often Profaned’, belonged to the younger generation of the Romantic poets. The son of a Tory squire, he was born in 1792. He was educated at Eton and Oxford, whence, however, he was soon expelled for publishing a pamphlet on The Necessity of Atheism.

An ill-advised marriage with a mere school-girl, Harriet Westbrook, led to an open rupture with his family, and Shelley found himself adrift. After the tragic death of his young wife, he married Mary, the daughter of William Godwin, whose influence on his mind was already immense. This second union proved a very happy one, for in Mary he had an intellectual companion and emotional support amid all the trouble arising from quarrels with his relatives, lawsuits about his property and his children, and his own highly strung temperament and fragile health. In 1818 he left England for Italy and in 1822 was drowned while sailing across the Bay of Spezzia.

Summary

The poem, ‘One Word Is Too Often Profaned’, is a short one, and was addressed to Jane Williams, like the poem called “To A Lady, With A Guitar”. It expresses Shelley’s genuine and deep devotion to Jane Williams with whom he had a special kind of relationship. Jane Williams exercised a considerable influence on Shelley, and the story of their relationship makes interesting reading. In the poem, he elevates her to a high position and offers her his worship.

Desmond King-Hele has the following comment to offer on this poem: “This poem is one of those anthologists” darlings so damaging to Shelley’s reputation. Continual reprinting in anthologies has quite mummified it” – deadened it; taken away its life and soul – boredom is the stock response on meeting it again. The poem has a glossy finish to deter scratches, but the ill-mannered cur who does scratch finds little beneath the surface gloss.

‘One Word Is Too Often Profaned’ is a conceit, like most seventeenth-century love-poems, and may provoke the ‘tetchy’ rebuke, “More matter with less art”. What this critic means to say is that, though on the surface the poem appears to be shining and attractive, there is very little matter or meaning in it. One is inclined to agree with this judgment, because the poem is really a trifle except for the line “The desire of the moth for the star” which is often applied to Shelley’s unattainable and impossible ideals.

Analysis of One Word Is Too Often Profaned

One word is too often profaned

For me to profane it,

Shelley means to say that the word “love” is so often misused and abused that it cannot be further abused by his making use of it. The word “love” has been cheapened and vulgarized by being constantly used.

One feeling too falsely disdain’d

For thee to disdain it.

The feeling of worship that a lover offers has often been rejected on false grounds. So false were the grounds on which this offer of worship has often been rejected, that she, Jane Williams, should not reject Shelley’s offer.

One hope is too like despair

For prudence to smother,

Although Shelley hopes that Jane Williams would respond to his sentiment, yet the hope seems to be illusory. His hope is very much like hopelessness, and therefore there is no need for his better judgment to crush his hope. His better judgement tells him that he cannot get the response which he desires. But there is no need for his better judgement to intervene because the hope that he entertains is itself very akin to hopelessness.

And pity from thee more dear

Than that from another.

Shelley says that a feeling of pity from Jane Williams would be more precious to him than the feeling of love from another woman. He has such a high opinion of Jane Williams that even sympathy from her would give him greater happiness than love from another woman. (The word “that” in line 8 stands for love).

I can give not what men call love;

But wilt thou accept not

The worship the heart lifts above

And the Heavens reject not:

The desire of the moth for the star,

Of the night for the morrow,

The devotion to something afar

From the sphere of our sorrow?

Shelley says that he cannot offer to her what is generally known as love, because the word “love” has been cheapened and vulgarized. But he can offer to her the feeling of worship which has an uplifting effect upon him and which even God does not reject. His reverence for her may be compared to the impossible desire of the moth for the star. He impatiently longs for her just as the night is impatient to be followed by the day. Living as he does in a world of sorrow, he offers to her his heartfelt devotion, and he asks her whether she will accept it.

For the month of May, Harriet will feature blog posts from the archive, along with a brief introduction. This week’s post, «Play and Imagination: On the One-Word Poem» by Orlando White, was originally published in November 2015.

There are many reasons people turn to poetry in times of crisis. For some, poetry brings comfort, offering solace and inspiration in a world that can feel bleak and unforgiving. But a poem can also be playful, bringing us pleasure and the thrill of discovery, even laughter. Seen in this light, poetry offers a different, though hardly less important kind of comfort. In what follows, the poet Orlando White delves into the playfulness of poetry through his close reading of a one word poem. White suggests that to write such a poem is to be like a child creating their first written word, «using the crayon to draw what a word might look like, and creating language outside the boundaries of standard writing.» As White notes, «to write means to link the brain, the eyes, the hands simultaneously,» to reimagine language and capture «the feeling of surprise and curiosity» it inspires.

—Harriet Editor

The process of writing a one-word poem on the page involves playfulness, along with the willingness to take risks with imagination—much like a toddler who scribbles letters for the first time on paper, using the crayon to draw what a word might look like, and creating language outside the boundaries of standard writing. In a way, to think like a child who is creating his first word on paper is to engage in a true act of writing. Because to write means to link the brain, the eyes, the hands simultaneously: it’s that coordination of the poet’s artistic vision and creative action, which can reveal a word’s identity through its image. In that moment, the poet writes mum in cursive and watches its shape flow like a wave across the page, or gig, to notice how the lower loop of g shapes itself into an earlobe. Through this practice, the poet guides his hand through a graphological meditation which then becomes an artistic mediation between self and page. This is when he reimagines language, reimagines the relationship of writing and experience to move toward a literary moment. Much like that moment when discovering a new word like “nefelibata,” that feeling of surprise and curiosity one has toward its spelling and meaning.

Let’s look at a one-word poem that is meant to be seen rather than read, a poem that’s meant to be viewed as image rather than text. In the poem “eye” by Aram Saroyan, he adds an additional “y” and “e” to the word to enact a sense of play and inventiveness. And in a way by adding extra letters the word visually becomes what it means:

At first glance this one-word poem appears disorienting; it takes a second for our eyes to adjust to it. Perhaps it’s because as viewers the extra y and e skew our perception a little. So we find ourselves scanning the word back and forth as if in a REM (Rapid Eye Movement) state. But what makes this poem effective too is its play on a palindrome. A palindrome is a word or sentence that reads the same forward and backward. Some examples are “toot,” “minim,” “never odd or even,” or “draw o coward.” In his one-word poem, Saroyan gets us to understand his interaction with language. His use of a palindrome gets us, as readers, to look closely at language, to literally eye the word, but then he adds those extra letters and suddenly the poem becomes visible as an image. In Ian Daly’s essay, “You Call That Poetry?!” Saroyan says, “I got intrigued by the look of individual words; the word ‘guarantee,’ for instance, looks to me a bit like a South American insect.” The one-word poem gets us to think about the word as picture and reminds us, as poets, that to develop the mind’s eye we must open ourselves up to seeing language and to feel the energy of a letter. The origin of the A, for example, derives from a pictogram dating back to the 11th century in the Middle East. The A is an ox-head, and if you rotate it until its stems point upward you will see the ox’s muzzle in the area between the apex and crossbar. Once we are aware that the letter is a picture, it’s up to us, as writers, to imagine the ox ploughing the field of the page, getting it ready for us to plant and expand our imagination.

Originally Published: May 29th, 2020

Poet Orlando White is from Tólikan, Arizona. He is Diné of the Naaneesht’ézhi Tábaahí and born for the Naakai Diné’e. White earned a BFA from the Institute of American Indian Arts and an MFA from Brown University. He is the author of LETTERRS (2015) and Bone Light (2009), a collection of…

Another unacclaimed one letter poem suggests to Gumman that the Guinness Book of Records may be wrong. He has come across a poem by the avant-garde Canadian poet, publisher, and bookseller jwcurry (John Curry) which consists of the letter “i” where the tittle is a thumbprint. And he applies his forensic textual analysis to that poem. “The curry piece,” Bob Gumman explains, “charmingly turns a standard, thoroughly un-unique letter i into the very essence of individuality by giving it a thumbprint.”

One of Aram Saroyan’s most famous poems was the unconventionally spelled word “lighght” in the centre of a blank page. This poem was featured in The American Literary Anthology and, like all poems in the volume, received a $500 cash award from the National Endowment for the Arts, then just five years old. The NEA was created in 1965, the same year the poem was written. Some prominent American politicians objected to the per-word amount of the award, complaining that the word was not a real poem and was not even spelled correctly. This was the NEA’s first major controversy. Years after it was written the American President, Ronald Reagan, was still making pejorative allusions to “lighght.” For more information on the poem and on the controversy, see the relevant links below.

The Scottish poet Edwin Morgan (1920-2010) published a hand-made booklet in which he reprinted nine one-word poems which were first published in the final issue of Poor. Old. Tired. Horse. no. 27 (c.1967). Ian Hamilton Finlay had requested from his contributors poems which “consist of one word, with a title of any length, these two elements forming, as it were, a corner which would then contain the meaning”. He wrote to the Austrian poet Ernst Jandl, “The kind of poem I would most like is a serious one, for many people have sent examples which are only briefly witty, and the form is capable of more than that. After all, one has the whole title to move around in.” These poems by Edwin Morgan are otherwise uncollected, though three (‘glasgow’, ‘morning’ and ‘blue’) are included in Atoms of Delight: an anthology of Scottish haiku and short poems (2000). Ian Hamilton Finlay produced his own book, Grains of Salt: 14 One-word Poems, in which the poems accompany linocuts of nautical subjects.

Geof Huth has coined a term to describe one version of the one word poem – PWOERMD – any one-word poem, such as Aram Saroyan’s famous ‘lighght’ or Jonathan Brannen’s ‘pigeoneon’ . (This word is a veritable pwoermd itself, since the “pw” at its beginning mirrors the “md” at the end, leaving the pseudo-archai-poetic “oer” in the middle of the word.)

poem + word (w/ the letters from each word alternated to produce the neologism)

This is what Ron Sillman has to say about Geoff Huth: “Huth, if you read his work or his website, is the most serious theorist of visual poetry I’ve ever seen. He is, in a sense, exactly what the genre needs, a systematic thinker and a goad, someone who will – by example if nothing else – prod others to try harder, do better.”

In what may be a mockery of the one word poem, and particularly the fame or notoriety that attended “lighght”, Dave Morice in 1972 published Matchbook, a magazine of one word poems, costing five cents a copy. Each issue was printed on one-inch square pages stapled inside of matchbooks donated by local businesses. Edited by the fictional Joyce Holland, each issue featured nine one-word poems submitted by contributors. Here are some of the contributions :-

apocatastasis (Allen Ginsberg)

borken (Keith Abbott)

cerealism (Fletcher Copp)

cosmicpolitan (Morty Sklar)

embooshed (Cinda Wormley)

gulp (Pat Paulsen)

Joyce (Andrei Codrescu)

meeeeeeeeeeeeee (Duane Ackerson)

puppylust (P.J. Casteel)

sixamtoninepm (Kit Robinson)

underwhere (Carol DeLugach)

zoombie (Sheila Heldenbrand)

The longest submission was whahavyagotthasgudtareedare by Trudi Katchmar which appeared as a foldout.

When Ian Hamilton Finlay (above) makes serious claims for the one word poem or when Geof Huth creates a theoretical underpinning for the form, they are both going further than I am prepared to concede. But there is a certain, almost perverse, fascination in the one word poem. What do you think? Is it fun, fundamental and flourishing, or is it just folly? Comment below.

Two One Letter Poems

Aram Saroyan

***

jwcurry

***

Four One Word Poems by Aram Saroyan

Aram Saroyan

***

Aram Saroyan

***

Aram Saroyan

***

(If you have difficulty viewing this image, it reads:- morni,ng)

Aram Saroyan

***

Two One Word Poems by Orlando White

balance

water

A One Word Haiku by Cor van den Heuvel

Four One Word Poems by Edwin Morgan

A Far Cool Beautiful Thing, Vanishing blue The Dear Green Plaice Glasgow Homage to Zukofsky the Dangerous Glory morning

Five One Word Poems by Ian Hamilton Finlay

The Cloud’s Anchor

swallow

***

The Boat’s Blueprint

water

***

A Patch for a Rip-tide

sail

***

A Grey Shore Between Day and Night

dusk

***

A Last Word

rudder

More One Word Poems

One-Word Poem

Motherless.

David R. Slavitt

***

The Last Breath of a Famous Philosopher

Why . . .

Douglas A. Mackey

***

The Lover Writes a One-Word Poem

You!

Gavin Ewart

***

8.06pm June 10 1970

poem

Tom Raworth

***

M SS NG

Thiiief!

George Swede

***

graveyarduskilldeer

George Swede

***

UTTER

John Bryam

***

pigeoneon

Jonathan Brannen

***

laugnage

Jonathan Brannen

***

eadacheadacheadach

Glenn Ingersoll

***

th’air

Greg Wolos

***

ccoommiittee.

Geof Huth

***

cant’

Crag Hill

LINKS

A Poetry Foundation article on the story behind the poem “lighght” by Aram Saroyan.

The Paris Review account of the Saroyan poem

The Scottish Poetry Library Page on Edwin Morgan.

Bob Grumman on MNMLST POETRY

Bob Murdoch on very brief poems

Geof Huth on Visual Poetry Today