Скачать материал

Скачать материал

- Сейчас обучается 396 человек из 63 регионов

- Сейчас обучается 268 человек из 64 регионов

Описание презентации по отдельным слайдам:

-

1 слайд

GRAMMATICAL MEANING

OF THE WORD -

2 слайд

1. The problem of word definition.

2. The notion of the word-form.

3. The notion of «grammatical meaning».

4. Types of grammatical meaning.

5. The notion of «grammatical category».

6. The notion of «opposition».3

-

3 слайд

1.The Problem of Word Definition

The word is considered to be the central (though not the only) linguistic unit of language.

3 -

4 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

In the written language words are clearly identified by spaces between them.

3

-

5 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

In the spoken language the problem cannot be solved this way.

↓

If we listen to an unfamiliar language, we find it difficult to divide up the speech into single words.3

-

6 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

Approaches

to the problem of word definition:

the word is a semantic unit, a unit of meaning;

the word is a marked phonological unit;

the word is an indivisible unit.3

-

7 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

Semantic definition of the word:

“…a unit of a particular meaning with a particular complex of sounds capable of a particular grammatical employment».

↓

The word is a linguistic unit that has a single meaning.3

-

8 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

BUT:

heavy smoker ≠ heavy and

smoker

criminal lawyer;

the King of England’s hat.3

-

9 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

The problem:

the word is not always a single unit.

3

-

10 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

A phonological criterion

that stuff that’s tough

a nice cakean ice cake

grey day Grade A

↓3

-

11 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

It is hard to distinguish the real meaning without a proper context.

3 -

12 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

The word as an indivisible unit

“The word is a minimum free form“

(L. Bloomfield)

↓

The word is the smallest unit of speech that can occur in isolation.3

-

13 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

BUT:

a or the3

-

14 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

Thus,

the word is a linguistic unit larger than a morpheme but smaller than a phrase.3

-

15 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

In this case the word can be defined as:

• An orthographic word (something written with white spaces at both ends but no white space in the middle).

3

-

16 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

• A phonological word (something pronounced as a single unit).

3

-

17 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

• A lexical item, or lexeme, (a dictionary word).

3

-

18 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

• A grammatical word-form (GWF) (or morphosyntactic word) (any one of the several forms which a lexical item may assume for grammatical purposes).

3

-

19 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

The item ice cream is:

two orthographic words,

but

— a single phonological word (it is pronounced as a unit),

— a single lexical item (it has its own entry in a dictionary),

— a single GWF (indeed, it hardly has another form unless you think the plural ice cream is good English).3

-

20 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

The singular dog and the plural dogs:

— a single orthographic word,

— a single phonological word,

a single GWF,

but they both

— represent the same lexical item (only one entry in the dictionary).3

-

21 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

???

take, takes, took, taken, is taking:3

-

22 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

take, takes, took, taken and is taking:

— five orthographic words,

— five phonological words,

five GWFs (at least),

but only

— one lexical item.3

-

23 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

???

the contraction hasn’t3

-

24 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

The contraction hasn’t is:

— a single orthographic word,

a single phonological word,

— two lexical items (have and not),

— two GWFs (has and not).3

-

25 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

???

The phrasal verb make up (as in She made up her face)3

-

26 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

The phrasal verb make up (as in She made up her face):

— two orthographic words,

— two phonological words,

— one lexical item (because of its unpredictable meaning, it must be entered separately in the dictionary).

— has several GWFs (make up, makes up, made up, making up).3

-

27 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

???

make up

(She made up a story)3

-

28 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

make up (She made up a story):

— a different lexical item from the preceding one (a separate dictionary entry is required),

but

— this lexical item exhibits the same orthographic, phonological and grammatical forms as the first.3

-

29 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

So,

the word is not a clearly definable linguistic unit.3

-

30 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

For the sake of linguistic description, we will proceed from the following statements:

— the word is a meaningful unit differentiating word-groups at the upper level and integrating morphemes at the lower level;3

-

31 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

— the word is the main expressive unit of human language, which ensures the thought-forming function of language;

3

-

32 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

the word It is also the basic nominative unit of language with the help of which the naming function of language is realized;

3

-

33 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

in the structure of language the word belongs to the upper stage of the morphological level;

3

-

34 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

the word is a unit of the sphere of «language» and it exists only through its speech actualization;

3

-

35 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

one of the most characteristic features of the word is its indivisibility.

3

-

36 слайд

The Problem of Word Definition

the word is a bilateral entity

concept

WORD = ———————

sound image3

-

37 слайд

2. The Notion of the Word -Form

The term «word-form“ shows that the word is a carrier of grammatical information.

E.g.: speaks — the present tense third

person singular

speak, spoke, is speaking

↓

Here the relational property of grammatical meaning is revealed.3

-

38 слайд

The Notion of the Word -Form

Grammatical meanings of a word-form are very abstract and general.

They are peculiar of a whole class of words, unite it so that each word of the class expresses the corresponding grammatical meaning together with its individual, concrete semantics.3

-

39 слайд

The Notion of the Word -Form

E.g.:

the meaning of the plural is rendered by the regular plural suffix –(e)s, phonemic interchange and a few lexeme-bound suffixes.3

-

40 слайд

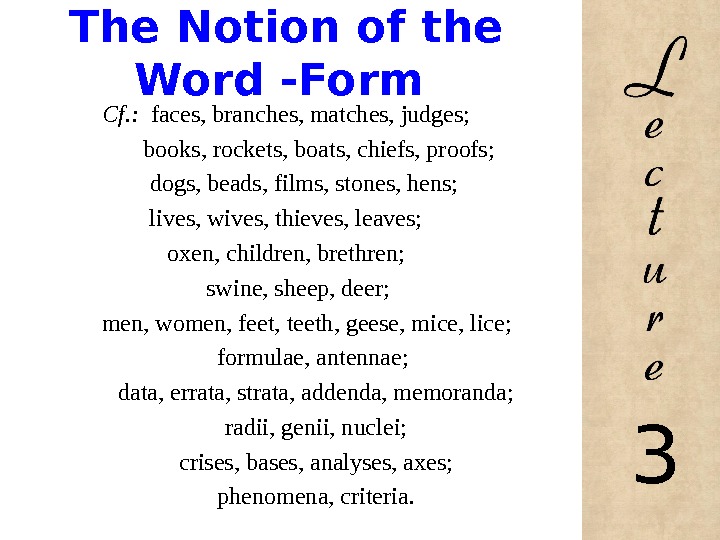

The Notion of the Word -Form

Due to the generalized character of the plural, we say that different groups of nouns «take» this form with strictly defined variations in the mode of expression.

The variations can be of more systemic (phonological conditioning) and less systemic (etymological conditioning) nature.3

-

41 слайд

The Notion of the Word -Form

Cf.: faces, branches, matches, judges;

books, rockets, boats, chiefs, proofs;

dogs, beads, films, stones, hens;

lives, wives, thieves, leaves;

oxen, children, brethren;

swine, sheep, deer;

men, women, feet, teeth, geese, mice, lice;

formulae, antennae;

data, errata, strata, addenda, memoranda;

radii, genii, nuclei;

crises, bases, analyses, axes;

phenomena, criteria.3

-

42 слайд

The Notion of the Word -Form

The lexical meaning of the word is irrelevant for the detection of the type of the word-form.

3

-

43 слайд

The Notion of the Word -Form

A word-form may be analytical by structure. In this case it is equivalent to one word as it expresses one unified content of a word, both from the point of view of grammatical and lexical meaning.

E.g.: has spoken3

-

44 слайд

The Notion of the Word -Form

Words (as well as morphemes) are directly observable units by nature as they are characterized by a definite material structure of their own.

They can be registered and enumerated in any language.

3

-

45 слайд

The Notion of the Word -Form

The system of morphological units is a closed system. It means that all its items are on the surface and can be embraced in an inventory of forms.

3

-

46 слайд

The Notion of the Word -Form

Every word is a unit of grammar as a part of speech.

3

-

47 слайд

The Notion of the Word -Form

Parts of speech are usually considered a lexico-grammatical categories since:

they show lexical groupings of words;

these groupings present generalized classes, each with a unified, abstract meaning of its own.3

-

48 слайд

3. The Notion of Grammatical Meaning

Notional words combine two meanings in their semantic structure:

lexical;

grammatical.3

-

49 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Meaning

Lexical meaning is the individual meaning of the word

E.g.: table — a definite piece of furniture with a flat top supported by one or more upright legs,

speak – to express thoughts aloud, using the voice.3

-

50 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Meaning

Grammatical (morphological) meaning is not individual.

↓

It is the meaning of the whole class or a subclass

E.g.: table (grammatical meaning of the class of nouns (thingness / substance) and the grammatical meaning of a subclass – countableness).3

-

51 слайд

?

What are grammatical meanings of:

— verbs;

adjectives;

adverbs?3

-

52 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Meaning

There are some classes of words that are devoid of any lexical meaning and possess the grammatical meaning only.

3

-

-

54 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Meaning

Function words

3

-

55 слайд

4.Types of Grammatical Meaning

The grammatical meaning may be:

explicit;

implicit.

3 -

56 слайд

Types of Grammatical Meaning

The implicit grammatical meaning is not expressed formallyE.g.: table (the meaning of inanimate object)

3

-

57 слайд

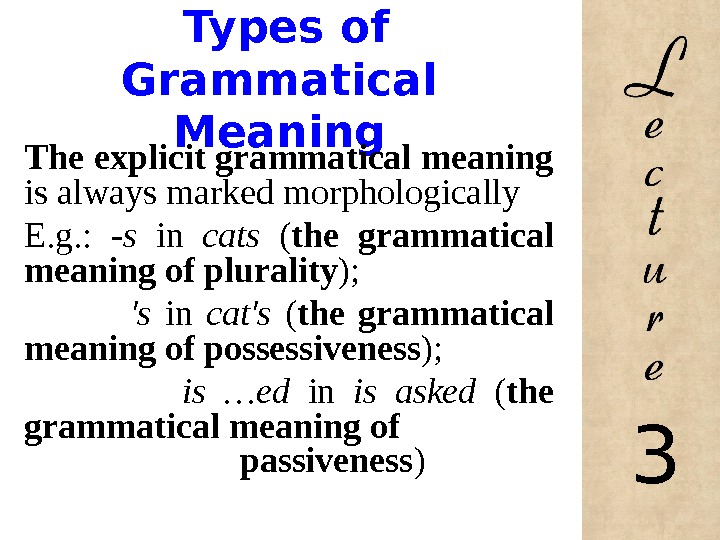

Types of Grammatical Meaning

The explicit grammatical meaning is always marked morphologically

E.g.: -s in cats (the grammatical meaning of plurality);

‘s in cat’s (the grammatical meaning of possessiveness);

is …ed in is asked (the grammatical meaning of passiveness)3

-

58 слайд

Types of Grammatical Meaning

Types of the implicit grammatical meaning:

general

dependent3

-

59 слайд

Types of Grammatical Meaning

general (the meaning of the whole word-class, of a part of speech)

E.g.: thingness of nouns3

-

60 слайд

Types of Grammatical Meaning

dependent (the meaning of a subclass within the same part of speech)

E.g.: the verb (transitivity/ intransitivity,

terminativeness / non-terminativeness,

stativeness / non-stativeness);

the noun (countableness / uncountableness,

animateness / inanimateness)3

-

61 слайд

Types of Grammatical Meaning

The dependent grammatical meaning influences the realization of grammatical categories restricting them to a subclass.

E.g.: the number category for the subclass of countable nouns;

the category of case for the subclass of animated nouns;

the category of voice for transitive verbs, etc.3

-

62 слайд

Types of Grammatical Meaning

3

-

63 слайд

5. The Notion of Grammatical Category

A grammatical category is a linguistic category which has the effect of modifying the forms of some class of words in a language.

3

-

64 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

Its structure displays two or more forms applied to a definite class of words and used in somewhat different grammatical circumstances.

↓↓3

-

65 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

Grammatical categories are made up by the unity of identical grammatical meanings that have the same form and meaning

E.g. singular : plural3

-

66 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

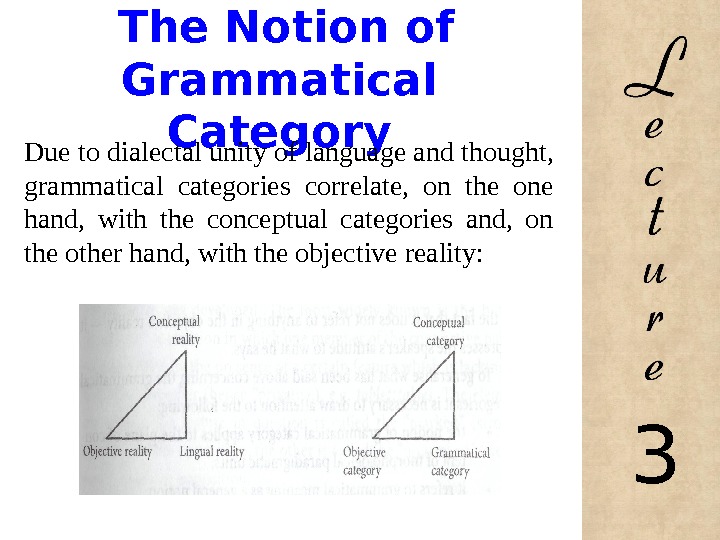

Due to dialectal unity of language and thought, grammatical categories correlate, on the one hand, with the conceptual categories and, on the other hand, with the objective reality:3

-

67 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

Thus,

grammatical categories are references of the corresponding objective categories.

E.g.: the objective category of time →

the grammatical category of tense,

the objective category of quantity → the grammatical category of number.3

-

68 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

Grammatical categories that have references in the objective reality are referential.

Objective correlate

↓

Lingual correlate3

-

69 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

Grammatical categories that do not correspond to anything in the objective reality and correlate only with conceptual matters are significational. They are few (e.g. the categories of mood and degree).

Conceptual correlate

↓

Lingual correlate3

-

70 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

Classifications of Gr. CategoriesAccording to the referent relation:

immanent;

— reflective.

3 -

71 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

Immanent gr. categories are:

1) innate for a given lexemic class, organically connected with its functional nature

E.g.: the number category of nouns,

the substantive-pronominal person

2) closed within a word-class

E.g.: the tense category of verbs,

the comparison of adjectives and adverbs3

-

72 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

Reflective gr. categories are of a secondary, derivative semantic value

E.g.: the number category of verbs,

the verbal person3

-

73 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

2. According to the changeability of the exposed feature

— unchangeable / derivational (constant feature categories)

E.g.: the gender category of nouns represented by the system of the 3rd person pronouns

— changeable / demutative (variable feature categories)

E.g.: the number category of nouns,

the degrees of comparison3

-

74 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

NB:

1. The notion of grammatical category applies to the plane of content of morphological paradigmatic units;3

-

75 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

2. It refers to grammatical meaning as a general notion;

3

-

76 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

3. It does not nominate things but expresses relations, that is why it has to be studied in terms of oppositions;

3

-

77 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

4. Grammatical categories of language represent a realization of universal categories produced by human thinking in a set of interrelated forms organized as oppositions;

3

-

78 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

5. Grammatical categories are not uniform, they vary in accordance with the part of speech they belong to and the meaning they express;

3

-

79 слайд

The Notion of Grammatical Category

6. The expression of grammatical categories in language is based upon close interrelation between their forms and the meaning they convey.

3

-

80 слайд

6. The Notion of Opposition

The concept of opposition is that it distinguishes something.

↓

3 -

81 слайд

The Notion of Opposition

One thing can be distinguished from another only if it can be contrasted with something else or opposed to it.3

-

82 слайд

The Notion of Opposition

Any grammatical category must be represented by at least two grammatical forms

E.g. the grammatical category of number: singular and plural forms.3

-

83 слайд

The Notion of Opposition

Thus,

the relation between two grammatical forms that differ in meaning and external signs is called opposition.3

-

84 слайд

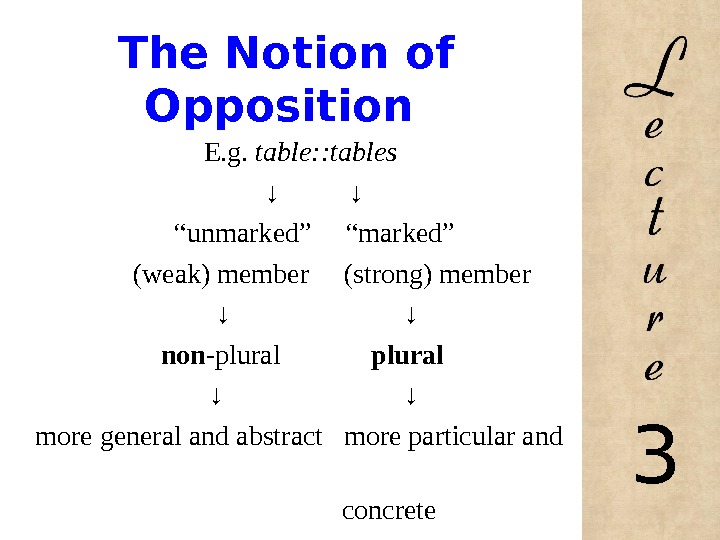

The Notion of Opposition

The most widely known opposition is the binary «privative» opposition.In it one member of the contrastive pair is characterized by the presence of a certain feature which the other member lacks

3

-

85 слайд

The Notion of Opposition

E.g. table::tables

↓ ↓

“unmarked” “marked”

(weak) member (strong) member

↓ ↓

non-plural plural

↓ ↓

more general and abstract more particular and

concrete

(used in a wider range of contexts)3

-

86 слайд

The Notion of Opposition

FYI:

Some scholars, however, hold the opinion that oppositions can be

gradual (different degree of a feature)

E.g.: big — bigger — biggest

equipollent (different positive features)

E.g.: am — is — are.3

-

87 слайд

The Notion of Opposition

NB:

A grammatical category is definable only on the basis of oppositions.3

-

88 слайд

The Notion of Opposition

Means of realization of grammatical categories:

synthetic (near — nearer);

analytical (beautiful — more beautiful).3

-

Найдите материал к любому уроку, указав свой предмет (категорию), класс, учебник и тему:

6 209 883 материала в базе

- Выберите категорию:

- Выберите учебник и тему

- Выберите класс:

-

Тип материала:

-

Все материалы

-

Статьи

-

Научные работы

-

Видеоуроки

-

Презентации

-

Конспекты

-

Тесты

-

Рабочие программы

-

Другие методич. материалы

-

Найти материалы

Другие материалы

- 27.12.2020

- 4748

- 2

- 27.12.2020

- 4947

- 11

- 27.12.2020

- 5785

- 13

- 27.12.2020

- 5022

- 9

- 27.12.2020

- 4057

- 1

- 27.12.2020

- 3882

- 0

- 27.12.2020

- 3905

- 1

- 27.12.2020

- 3300

- 4

Вам будут интересны эти курсы:

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Основы местного самоуправления и муниципальной службы»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация и предоставление туристских услуг»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Клиническая психология: организация реабилитационной работы в социальной сфере»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Организация практики студентов в соответствии с требованиями ФГОС педагогических направлений подготовки»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Этика делового общения»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Маркетинг в организации как средство привлечения новых клиентов»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Правовое регулирование рекламной и PR-деятельности»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Финансы предприятия: актуальные аспекты в оценке стоимости бизнеса»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Управление ресурсами информационных технологий»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация деятельности помощника-референта руководителя со знанием иностранных языков»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация деятельности секретаря руководителя со знанием английского языка»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Управление сервисами информационных технологий»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Эксплуатация и обслуживание общего имущества многоквартирного дома»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Техническая диагностика и контроль технического состояния автотранспортных средств»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация маркетинговой деятельности»

- Размер: 2.6 Mегабайта

- Количество слайдов: 89

2.1. Morphology: definition.

The

notion of morpheme.

Morphology

(Gr. morphe – form, and logos – word) is a branch of grammar that

concerns itself with the internal structure of words and

peculiarities of their grammatical categories and their semantics.

The study

of Modern English morphology consists of four main items,

(1) general

study of morphemes and types of word-form derivation,

(2) the system of parts of

speech,

(3) the

study of each separate part of speech, the grammatical categories

connected with it, and its syntactical functions.

The

morpheme

may be defined as an elementary meaningful segmental component of the

word. It is built up by phonemes and is indivisible into smaller

segments as regards its significative function.

Example:

writers

can be divided into three morphemes:

(1) writ-,

expressing the basic lexical meaning of the word,

(2) —er-,

expressing the idea of agent performing the action indicated by the

root of the verb,

(3) —s,

indicating number, that is, showing that more than one person of the

type indicated is meant.

Two or more

morphemes may sound the same but be basically different, that is,

they may be homonyms.

Thus the -er

morpheme indicating the doer of an action as in writer

has a homonym — the morpheme -er

denoting the comparative degree of adjectives and adverbs, as in

longer.

There may

be zero

morphemes,

that is, the absence of a morpheme may indicate a certain meaning.

Thus, if we compare the words book

and books,

both derived from the stem book-,

we may say that while books

is characterised by the –s

morpheme indicating a plural form, book

is characterised by the zero morpheme indicating a singular form.

Traditional

classification of morphemes is based on the two basic criteria:

-

positional

– the location of the marginal

morphemes

(периферийные

морфемы)

in relation to the central

ones

(центральные

морфемы) -

semantic/functional

– the correlative contribution (соотносительный

вклад)

of the morphemes to the general meaning of the word.

According

to this classification, morphemes are divided into:

-

root-morphemes

(roots)

– express the concrete, ‘material’ (насыщенная

конкретным

содержанием,

вещественная)

part of the meaning of the word.

The roots

of notional words are classical lexical

morphemes.

-

affixal

morphemes (affixes) – express

the specificational (спецификационная)

part of the meaning of the word.

This

specification can have lexico-semantic (лексическая)

and grammatico-semantic (грамматическая)

character.

The affixal

morphemes include:

1) prefixes

2) suffixes

Prefixes

and lexical suffixes have word-building functions, and form the stem

of the word together with the root.

3)

inflexions

(флексия)/grammatical

suffix

(Blokh)

The

morpheme serves to derive a grammatical form; it has no lexical

meaning of its own and expresses different morphological categories.

The

abstract complete morphemic model of the common English word is the

following: prefix + root + lexical suffix + inflection/grammatical

suffix.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

In linguistics, morphology ([1]) is the study of words, how they are formed, and their relationship to other words in the same language.[2][3] It analyzes the structure of words and parts of words such as stems, root words, prefixes, and suffixes. Morphology also looks at parts of speech, intonation and stress, and the ways context can change a word’s pronunciation and meaning. Morphology differs from morphological typology, which is the classification of languages based on their use of words,[4] and lexicology, which is the study of words and how they make up a language’s vocabulary.[5]

While words, along with clitics, are generally accepted as being the smallest units of syntax, in most languages, if not all, many words can be related to other words by rules that collectively describe the grammar for that language. For example, English speakers recognize that the words dog and dogs are closely related, differentiated only by the plurality morpheme «-s», only found bound to noun phrases. Speakers of English, a fusional language, recognize these relations from their innate knowledge of English’s rules of word formation. They infer intuitively that dog is to dogs as cat is to cats; and, in similar fashion, dog is to dog catcher as dish is to dishwasher. By contrast, Classical Chinese has very little morphology, using almost exclusively unbound morphemes («free» morphemes) and it relies on word order to convey meaning. (Most words in modern Standard Chinese [«Mandarin»], however, are compounds and most roots are bound.) These are understood as grammars that represent the morphology of the language. The rules understood by a speaker reflect specific patterns or regularities in the way words are formed from smaller units in the language they are using, and how those smaller units interact in speech. In this way, morphology is the branch of linguistics that studies patterns of word formation within and across languages and attempts to formulate rules that model the knowledge of the speakers of those languages.

Phonological and orthographic modifications between a base word and its origin may be partial to literacy skills. Studies have indicated that the presence of modification in phonology and orthography makes morphologically complex words harder to understand and that the absence of modification between a base word and its origin makes morphologically complex words easier to understand. Morphologically complex words are easier to comprehend when they include a base word.[6]

Polysynthetic languages, such as Chukchi, have words composed of many morphemes. For example, the Chukchi word «təmeyŋəlevtpəγtərkən», meaning «I have a fierce headache», is composed of eight morphemes t-ə-meyŋ-ə-levt-pəγt-ə-rkən that may be glossed. The morphology of such languages allows for each consonant and vowel to be understood as morphemes, while the grammar of the language indicates the usage and understanding of each morpheme.

The discipline that deals specifically with the sound changes occurring within morphemes is morphophonology.

HistoryEdit

The history of morphological analysis dates back to the ancient Indian linguist Pāṇini, who formulated the 3,959 rules of Sanskrit morphology in the text Aṣṭādhyāyī by using a constituency grammar. The Greco-Roman grammatical tradition also engaged in morphological analysis.[7] Studies in Arabic morphology, conducted by Marāḥ al-arwāḥ and Aḥmad b. ‘alī Mas’ūd, date back to at least 1200 CE.[8]

The linguistic term «morphology» was coined by August Schleicher in 1859.[a][9]

Fundamental conceptsEdit

Lexemes and word-formsEdit

The term «word» has no well-defined meaning.[10] Instead, two related terms are used in morphology: lexeme and word-form. Generally, a lexeme is a set of inflected word-forms that is often represented with the citation form in small capitals.[11] For instance, the lexeme eat contains the word-forms eat, eats, eaten, and ate. Eat and eats are thus considered different word-forms belonging to the same lexeme eat. Eat and Eater, on the other hand, are different lexemes, as they refer to two different concepts.

Prosodic word vs. morphological wordEdit

Here are examples from other languages of the failure of a single phonological word to coincide with a single morphological word form. In Latin, one way to express the concept of ‘NOUN-PHRASE1 and NOUN-PHRASE2‘ (as in «apples and oranges») is to suffix ‘-que’ to the second noun phrase: «apples oranges-and». An extreme level of the theoretical quandary posed by some phonological words is provided by the Kwak’wala language.[b] In Kwak’wala, as in a great many other languages, meaning relations between nouns, including possession and «semantic case», are formulated by affixes, instead of by independent «words». The three-word English phrase, «with his club», in which ‘with’ identifies its dependent noun phrase as an instrument and ‘his’ denotes a possession relation, would consist of two words or even one word in many languages. Unlike most other languages, Kwak’wala semantic affixes phonologically attach not to the lexeme they pertain to semantically but to the preceding lexeme. Consider the following example (in Kwak’wala, sentences begin with what corresponds to an English verb):[c]

kwixʔid-i-da

clubbed-PIVOT—DETERMINER

bəgwanəmai-χ-a

man-ACCUSATIVE—DETERMINER

q’asa-s-isi

otter-INSTRUMENTAL—3SG—POSSESSIVE

«the man clubbed the otter with his club.»

(Notation notes:

- accusative case marks an entity that something is done to.

- determiners are words such as «the», «this», and «that».

- the concept of «pivot» is a theoretical construct that is not relevant to this discussion.)

That is, to a speaker of Kwak’wala, the sentence does not contain the «words» ‘him-the-otter’ or ‘with-his-club’ Instead, the markers —i-da (PIVOT-‘the’), referring to «man», attaches not to the noun bəgwanəma («man») but to the verb; the markers —χ-a (ACCUSATIVE-‘the’), referring to otter, attach to bəgwanəma instead of to q’asa (‘otter’), etc. In other words, a speaker of Kwak’wala does not perceive the sentence to consist of these phonological words:

i-da-bəgwanəma

PIVOT-the-mani

s-isi-t’alwagwayu

with-hisi-club

A central publication on this topic is the volume edited by Dixon and Aikhenvald (2002), examining the mismatch between prosodic-phonological and grammatical definitions of «word» in various Amazonian, Australian Aboriginal, Caucasian, Eskimo, Indo-European, Native North American, West African, and sign languages. Apparently, a wide variety of languages make use of the hybrid linguistic unit clitic, possessing the grammatical features of independent words but the prosodic-phonological lack of freedom of bound morphemes. The intermediate status of clitics poses a considerable challenge to linguistic theory.[12]

Inflection vs. word formationEdit

Given the notion of a lexeme, it is possible to distinguish two kinds of morphological rules. Some morphological rules relate to different forms of the same lexeme, but other rules relate to different lexemes. Rules of the first kind are inflectional rules, but those of the second kind are rules of word formation.[13] The generation of the English plural dogs from dog is an inflectional rule, and compound phrases and words like dog catcher or dishwasher are examples of word formation. Informally, word formation rules form «new» words (more accurately, new lexemes), and inflection rules yield variant forms of the «same» word (lexeme).

The distinction between inflection and word formation is not at all clear-cut. There are many examples for which linguists fail to agree whether a given rule is inflection or word formation. The next section will attempt to clarify the distinction.

Word formation includes a process in which one combines two complete words, but inflection allows the combination of a suffix with a verb to change the latter’s form to that of the subject of the sentence. For example: in the present indefinite, ‘go’ is used with subject I/we/you/they and plural nouns, but third-person singular pronouns (he/she/it) and singular nouns causes ‘goes’ to be used. The ‘-es’ is therefore an inflectional marker that is used to match with its subject. A further difference is that in word formation, the resultant word may differ from its source word’s grammatical category, but in the process of inflection, the word never changes its grammatical category.

Types of word formationEdit

There is a further distinction between two primary kinds of morphological word formation: derivation and compounding. The latter is a process of word formation that involves combining complete word forms into a single compound form. Dog catcher, therefore, is a compound, as both dog and catcher are complete word forms in their own right but are subsequently treated as parts of one form. Derivation involves affixing bound (non-independent) forms to existing lexemes, but the addition of the affix derives a new lexeme. The word independent, for example, is derived from the word dependent by using the prefix in-, and dependent itself is derived from the verb depend. There is also word formation in the processes of clipping in which a portion of a word is removed to create a new one, blending in which two parts of different words are blended into one, acronyms in which each letter of the new word represents a specific word in the representation (NATO for North Atlantic Treaty Organization), borrowing in which words from one language are taken and used in another, and coinage in which a new word is created to represent a new object or concept.[14]

Paradigms and morphosyntaxEdit

A linguistic paradigm is the complete set of related word forms associated with a given lexeme. The familiar examples of paradigms are the conjugations of verbs and the declensions of nouns. Also, arranging the word forms of a lexeme into tables, by classifying them according to shared inflectional categories such as tense, aspect, mood, number, gender or case, organizes such. For example, the personal pronouns in English can be organized into tables by using the categories of person (first, second, third); number (singular vs. plural); gender (masculine, feminine, neuter); and case (nominative, oblique, genitive).

The inflectional categories used to group word forms into paradigms cannot be chosen arbitrarily but must be categories that are relevant to stating the syntactic rules of the language. Person and number are categories that can be used to define paradigms in English because the language has grammatical agreement rules, which require the verb in a sentence to appear in an inflectional form that matches the person and number of the subject. Therefore, the syntactic rules of English care about the difference between dog and dogs because the choice between both forms determines the form of the verb that is used. However, no syntactic rule shows the difference between dog and dog catcher, or dependent and independent. The first two are nouns, and the other two are adjectives.

An important difference between inflection and word formation is that inflected word forms of lexemes are organized into paradigms that are defined by the requirements of syntactic rules, and there are no corresponding syntactic rules for word formation.

The relationship between syntax and morphology, as well as how they interact, is called «morphosyntax»;[15][16] the term is also used to underline the fact that syntax and morphology are interrelated.[17] The study of morphosyntax concerns itself with inflection and paradigms, and some approaches to morphosyntax exclude from its domain the phenomena of word formation, compounding, and derivation.[15] Within morphosyntax fall the study of agreement and government.[15]

AllomorphyEdit

Above, morphological rules are described as analogies between word forms: dog is to dogs as cat is to cats and dish is to dishes. In this case, the analogy applies both to the form of the words and to their meaning. In each pair, the first word means «one of X», and the second «two or more of X», and the difference is always the plural form -s (or -es) affixed to the second word, which signals the key distinction between singular and plural entities.

One of the largest sources of complexity in morphology is that the one-to-one correspondence between meaning and form scarcely applies to every case in the language. In English, there are word form pairs like ox/oxen, goose/geese, and sheep/sheep whose difference between the singular and the plural is signaled in a way that departs from the regular pattern or is not signaled at all. Even cases regarded as regular, such as -s, are not so simple; the -s in dogs is not pronounced the same way as the -s in cats, and in plurals such as dishes, a vowel is added before the -s. Those cases, in which the same distinction is effected by alternative forms of a «word», constitute allomorphy.[18]

Phonological rules constrain the sounds that can appear next to each other in a language, and morphological rules, when applied blindly, would often violate phonological rules by resulting in sound sequences that are prohibited in the language in question. For example, to form the plural of dish by simply appending an -s to the end of the word would result in the form *[dɪʃs], which is not permitted by the phonotactics of English. To «rescue» the word, a vowel sound is inserted between the root and the plural marker, and [dɪʃɪz] results. Similar rules apply to the pronunciation of the -s in dogs and cats: it depends on the quality (voiced vs. unvoiced) of the final preceding phoneme.

Lexical morphologyEdit

Lexical morphology is the branch of morphology that deals with the lexicon that, morphologically conceived, is the collection of lexemes in a language. As such, it concerns itself primarily with word formation: derivation and compounding.

ModelsEdit

There are three principal approaches to morphology and each tries to capture the distinctions above in different ways:

- Morpheme-based morphology, which makes use of an item-and-arrangement approach.

- Lexeme-based morphology, which normally makes use of an item-and-process approach.

- Word-based morphology, which normally makes use of a word-and-paradigm approach.

While the associations indicated between the concepts in each item in that list are very strong, they are not absolute.

Morpheme-based morphologyEdit

Morpheme-based morphology tree of the word «independently»

In morpheme-based morphology, word forms are analyzed as arrangements of morphemes. A morpheme is defined as the minimal meaningful unit of a language. In a word such as independently, the morphemes are said to be in-, de-, pend, -ent, and -ly; pend is the (bound) root and the other morphemes are, in this case, derivational affixes.[d] In words such as dogs, dog is the root and the -s is an inflectional morpheme. In its simplest and most naïve form, this way of analyzing word forms, called «item-and-arrangement», treats words as if they were made of morphemes put after each other («concatenated») like beads on a string. More recent and sophisticated approaches, such as distributed morphology, seek to maintain the idea of the morpheme while accommodating non-concatenated, analogical, and other processes that have proven problematic for item-and-arrangement theories and similar approaches.

Morpheme-based morphology presumes three basic axioms:[19]

- Baudouin’s «single morpheme» hypothesis: Roots and affixes have the same status as morphemes.

- Bloomfield’s «sign base» morpheme hypothesis: As morphemes, they are dualistic signs, since they have both (phonological) form and meaning.

- Bloomfield’s «lexical morpheme» hypothesis: morphemes, affixes and roots alike are stored in the lexicon.

Morpheme-based morphology comes in two flavours, one Bloomfieldian[20] and one Hockettian.[21] For Bloomfield, the morpheme was the minimal form with meaning, but did not have meaning itself.[clarification needed] For Hockett, morphemes are «meaning elements», not «form elements». For him, there is a morpheme plural using allomorphs such as -s, -en and -ren. Within much morpheme-based morphological theory, the two views are mixed in unsystematic ways so a writer may refer to «the morpheme plural» and «the morpheme -s» in the same sentence.

Lexeme-based morphologyEdit

Lexeme-based morphology usually takes what is called an item-and-process approach. Instead of analyzing a word form as a set of morphemes arranged in sequence, a word form is said to be the result of applying rules that alter a word-form or stem in order to produce a new one. An inflectional rule takes a stem, changes it as is required by the rule, and outputs a word form;[22] a derivational rule takes a stem, changes it as per its own requirements, and outputs a derived stem; a compounding rule takes word forms, and similarly outputs a compound stem.

Word-based morphologyEdit

Word-based morphology is (usually) a word-and-paradigm approach. The theory takes paradigms as a central notion. Instead of stating rules to combine morphemes into word forms or to generate word forms from stems, word-based morphology states generalizations that hold between the forms of inflectional paradigms. The major point behind this approach is that many such generalizations are hard to state with either of the other approaches. Word-and-paradigm approaches are also well-suited to capturing purely morphological phenomena, such as morphomes. Examples to show the effectiveness of word-based approaches are usually drawn from fusional languages, where a given «piece» of a word, which a morpheme-based theory would call an inflectional morpheme, corresponds to a combination of grammatical categories, for example, «third-person plural». Morpheme-based theories usually have no problems with this situation since one says that a given morpheme has two categories. Item-and-process theories, on the other hand, often break down in cases like these because they all too often assume that there will be two separate rules here, one for third person, and the other for plural, but the distinction between them turns out to be artificial. The approaches treat these as whole words that are related to each other by analogical rules. Words can be categorized based on the pattern they fit into. This applies both to existing words and to new ones. Application of a pattern different from the one that has been used historically can give rise to a new word, such as older replacing elder (where older follows the normal pattern of adjectival superlatives) and cows replacing kine (where cows fits the regular pattern of plural formation).

Morphological typologyEdit

In the 19th century, philologists devised a now classic classification of languages according to their morphology. Some languages are isolating, and have little to no morphology; others are agglutinative whose words tend to have many easily separable morphemes; others yet are inflectional or fusional because their inflectional morphemes are «fused» together. That leads to one bound morpheme conveying multiple pieces of information. A standard example of an isolating language is Chinese. An agglutinative language is Turkish. Latin and Greek are prototypical inflectional or fusional languages.

It is clear that this classification is not at all clearcut, and many languages (Latin and Greek among them) do not neatly fit any one of these types, and some fit in more than one way. A continuum of complex morphology of language may be adopted.

The three models of morphology stem from attempts to analyze languages that more or less match different categories in this typology. The item-and-arrangement approach fits very naturally with agglutinative languages. The item-and-process and word-and-paradigm approaches usually address fusional languages.

As there is very little fusion involved in word formation, classical typology mostly applies to inflectional morphology. Depending on the preferred way of expressing non-inflectional notions, languages may be classified as synthetic (using word formation) or analytic (using syntactic phrases).

ExamplesEdit

Pingelapese is a Micronesian language spoken on the Pingelap atoll and on two of the eastern Caroline Islands, called the high island of Pohnpei. Similar to other languages, words in Pingelapese can take different forms to add to or even change its meaning. Verbal suffixes are morphemes added at the end of a word to change its form. Prefixes are those that are added at the front. For example, the Pingelapese suffix –kin means ‘with’ or ‘at.’ It is added at the end of a verb.

- ius = to use → ius-kin = to use with

- mwahu = to be good → mwahu-kin = to be good at

sa- is an example of a verbal prefix. It is added to the beginning of a word and means ‘not.’

- pwung = to be correct → sa-pwung = to be incorrect

There are also directional suffixes that when added to the root word give the listener a better idea of where the subject is headed. The verb alu means to walk. A directional suffix can be used to give more detail.

- -da = ‘up’ → aluh-da = to walk up

- -di = ‘down’ → aluh-di = to walk down

- -eng = ‘away from speaker and listener’ → aluh-eng = to walk away

Directional suffixes are not limited to motion verbs. When added to non-motion verbs, their meanings are a figurative one. The following table gives some examples of directional suffixes and their possible meanings.[23]

| Directional suffix | Motion verb | Non-motion verb |

|---|---|---|

| -da | up | Onset of a state |

| -di | down | Action has been completed |

| -la | away from | Change has caused the start of a new state |

| -doa | towards | Action continued to a certain point in time |

| -sang | from | Comparative |

See alsoEdit

- Morphome (linguistics)

FootnotesEdit

- ^ Für die lere von der wortform wäle ich das wort « morphologie», nach dem vorgange der naturwißenschaften […] (Standard High German «Für die Lehre von der Wortform wähle ich das Wort «Morphologie», nach dem Vorgange der Naturwissenschaften […]», «For the science of word-formation, I choose the term «morphology»….»

- ^ Formerly known as Kwakiutl, Kwak’wala belongs to the Northern branch of the Wakashan language family. «Kwakiutl» is still used to refer to the tribe itself, along with other terms.

- ^ Example taken from Foley (1998) using a modified transcription. This phenomenon of Kwak’wala was reported by Jacobsen as cited in van Valin & LaPolla (1997).

- ^ The existence of words like appendix and pending in English does not mean that the English word depend is analyzed into a derivational prefix de- and a root pend. While all those were indeed once related to each other by morphological rules, that was only the case in Latin, not in English. English borrowed such words from French and Latin but not the morphological rules that allowed Latin speakers to combine de- and the verb pendere ‘to hang’ into the derivative dependere.

ReferencesEdit

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- ^ Anderson, Stephen R. (n.d.). «Morphology». Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science. Macmillan Reference, Ltd., Yale University. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Aronoff, Mark; Fudeman, Kirsten (n.d.). «Morphology and Morphological Analysis» (PDF). What is Morphology?. Blackwell Publishing. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Brown, Dunstan (December 2012) [2010]. «Morphological Typology» (PDF). In Jae Jung Song (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Typology. pp. 487–503. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199281251.013.0023. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Sankin, A.A. (1979) [1966]. «I. Introduction» (PDF). In Ginzburg, R.S.; Khidekel, S.S.; Knyazeva, G. Y.; Sankin, A.A. (eds.). A Course in Modern English Lexicology (Revised and Enlarged, Second ed.). Moscow: VYSŠAJA ŠKOLA. p. 7. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Wilson-Fowler, E.B., & Apel, K. (2015). «Influence of Morphological Awareness on College Students’ Literacy Skills: A path Analytic Approach». Journal of Literacy Research. 47 (3): 405–32. doi:10.1177/1086296×15619730. S2CID 142149285.

- ^ Beard, Robert (1995). Lexeme-Morpheme Base Morphology: A General Theory of Inflection and Word Formation. Albany: NY: State University of New York Press. pp. 2, 3. ISBN 0-7914-2471-5.

- ^ Åkesson 2001.

- ^ Schleicher, August (1859). «Zur Morphologie der Sprache». Mémoires de l’Académie Impériale des Sciences de St.-Pétersbourg. VII°. Vol. I, N.7. St. Petersburg. p. 35.

- ^ Haspelmath & Sims 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Haspelmath & Sims 2002, p. 16.

- ^ Word : a cross-linguistic typology. Robert M. W. Dixon, A. I︠U︡. Aĭkhenvalʹd. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 978-0-511-48624-1. OCLC 704513339.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Anderson, Stephen R. (1992). A-Morphous Morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 74, 75. ISBN 9780521378666.

- ^ Plag, Ingo (2003). «Word Formation in English» (PDF). Library of Congress. Cambridge. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- ^ a b c

Dufter and Stark (2017) Introduction — 2 Syntax and morphosyntax: some basic notions in Dufter, Andreas, and Stark, Elisabeth (eds., 2017) Manual of Romance Morphosyntax and Syntax, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG - ^ Emily M. Bender (2013) Linguistic Fundamentals for Natural Language Processing: 100 Essentials from Morphology and Syntax, ch.4 Morphosyntax, p.35, Morgan & Claypool Publishers

- ^ Van Valin, R. D., van Valin Jr, R. D., van Valin Jr, R. D., LaPolla, R. J., & LaPolla, R. J. (1997) Syntax: Structure, meaning, and function, p.2, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Haspelmath, Martin; Sims, Andrea D. (2002). Understanding Morphology. London: Arnold. ISBN 0-340-76026-5.

- ^ Beard 1995.

- ^ Bloomfield 1933.

- ^ Hockett 1947.

- ^ Bybee, Joan L. (1985). Morphology: A Study of the Relation Between Meaning and Form. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 11, 13.

- ^ Hattori, Ryoko (2012). Preverbal Particles in Pingelapese. pp. 31–33.

Further readingEdit

- Aronoff, Mark (1993). Morphology by Itself. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262510721.

- Aronoff, Mark (2009). «Morphology: an interview with Mark Aronoff» (PDF). ReVEL. 7 (12). ISSN 1678-8931. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06..

- Åkesson, Joyce (2001). Arabic morphology and phonology: based on the Marāḥ al-arwāḥ by Aḥmad b. ʻAlī b. Masʻūd. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 9789004120280.

- Bauer, Laurie (2003). Introducing linguistic morphology (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: SGeorgetown University Press. ISBN 0-87840-343-4.

- Bauer, Laurie (2004). A glossary of morphology. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Bloomfield, Leonard (1933). Language. New York: Henry Holt. OCLC 760588323.

- Bubenik, Vit (1999). An introduction to the study of morphology. LINCOM coursebooks in linguistics, 07. Muenchen: LINCOM Europa. ISBN 3-89586-570-2.

- Dixon, R. M. W.; Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y., eds. (2007). Word: A cross-linguistic typology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Foley, William A (1998). Symmetrical Voice Systems and Precategoriality in Philippine Languages (Speech). Voice and Grammatical Functions in Austronesian. University of Sydney. Archived from the original on 2006-09-25.

- Hockett, Charles F. (1947). «Problems of morphemic analysis». Language. 23 (4): 321–343. doi:10.2307/410295. JSTOR 410295.

- Fabrega, Antonio; Scalise, Sergio (2012). Morphology: from Data to Theory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Katamba, Francis (1993). Morphology. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-10356-5.

- Korsakov, Andrey Konstantinovich (1969). «The use of tenses in English». In Korsakov, Andrey Konstantinovich (ed.). Structure of Modern English pt. 1.

- Kishorjit, N; Vidya Raj, RK; Nirmal, Y; Sivaji, B. (December 2012). Manipuri Morpheme Identification (PDF) (Speech). Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on South and Southeast Asian Natural Language Processing (SANLP). Mumbai: COLING.

- Matthews, Peter (1991). Morphology (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42256-6.

- Mel’čuk, Igor A (1993). Cours de morphologie générale (in French). Montreal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

- Mel’čuk, Igor A (2006). Aspects of the theory of morphology. Berlin: Mouton.

- Scalise, Sergio (1983). Generative Morphology. Dordrecht: Foris.

- Singh, Rajendra; Starosta, Stanley, eds. (2003). Explorations in Seamless Morphology. SAGE. ISBN 0-7619-9594-3.

- Spencer, Andrew (1991). Morphological theory: an introduction to word structure in generative grammar. Blackwell textbooks in linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-16144-9.

- Spencer, Andrew; Zwicky, Arnold M., eds. (1998). The handbook of morphology. Blackwell handbooks in linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-18544-5.

- Stump, Gregory T. (2001). Inflectional morphology: a theory of paradigm structure. Cambridge studies in linguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78047-0.

- van Valin, Robert D.; LaPolla, Randy (1997). Syntax : Structure, Meaning And Function. Cambridge University Press.

External linksEdit

- Lecture 7 Morphology in Linguistics 001 by Mark Liberman, ling.upenn.edu

- Intro to Linguistics – Morphology by Jirka Hana, ufal.mff.cuni.cz

- Morphology by Stephen R. Anderson, part of Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science, cowgill.ling.yale.edu

- Introduction to Linguistic Theory — Morphology: The Words of Language by Adam Szczegielniak, scholar.harvard.edu

- LIGN120: Introduction to Morphology by Farrell Ackerman and Henry Beecher, grammar.ucsd.edu

- Morphological analysis by P.J.Hancox, cs.bham.ac.uk

- The content on this page originated on Wikipedia and is yet to be significantly improved. Contributors are invited to replace and add material to make this an original article.

This article is about the linguistic field of morphology. For other uses of the term morphology, please see morphology (disambiguation).

In linguistics, morphology is the study of word structure. While words are generally accepted as being the smallest units of syntax, it is clear that in most (if not all) languages, words can be related to other words by rules. For example, English speakers recognize that the words dog, dogs and dog-catcher are closely related. English speakers recognize these relations by virtue of the unconscious linguistic knowledge they have of the rules of word-formation processes in English. Therefore, these speakers intuit that dog is to dogs just as cat is to cats, or encyclopædia is to encyclopædias; similarly, dog is to dog-catcher as dish is to dishwasher. The rules comprehended by the speaker in each case reflect specific patterns (or regularities) in the way words are formed from smaller units and how those smaller units interact in speech. In this way, morphology is the branch of linguistics that studies such patterns of word-formation across and within languages, and attempts to explicate formal rules reflective of the knowledge of the speakers of those languages.

History

The history of morphological analysis dates back to the ancient Indian linguist Pāṇini who formulated the 3,959 rules of Sanskrit morphology in the text Aṣṭādhyāyī. The Graeco-Roman grammatical tradition also engaged in morphological analysis.

The term morphology was coined by August Schleicher in 1859: Für die Lehre von der Wortform wähle ich das Wort «Morphologie» («for the science of word formation, I choose the term ‘morphology'», Mémoires Acad. Impériale 7/1/7, 35). It derives from the Greek words μορφή («form») and λόγος («explanation, account»).

Fundamental concepts

Lexemes and word forms

The term «word» is ambiguous in common usage. To take up again the example of dog vs. dogs, there is one sense in which these two are the same «word» (they are both nouns that refer to the same kind of animal, differing only in number), and another sense in which they are different words (they can’t generally be used in the same sentences without altering other words to fit; for example, the verbs is and are in The dog is happy and The dogs are happy).

The distinction between these two senses of «word» is arguably the most important one in morphology. The first sense of «word,» the one in which dog and dogs are «the same word,» is called lexeme. The second sense is called word-form. We thus say that dog and dogs are different forms of the same lexeme. Dog and dog-catcher, on the other hand, are different lexemes; for example, they refer to two different kinds of entities. The form of a word that is chosen conventionally to represent the canonical form of a word is called a lemma, or citation form.

Inflection vs. word-formation

Given the notion of a lexeme, it is possible to distinguish two kinds of morphological rules. Some morphological rules relate different forms of the same lexeme; while other rules relate two different lexemes. Rules of the first kind are called inflectional rules, while those of the second kind are called word-formation. The English plural, as illustrated by dog and dogs, is an inflectional rule; compounds like dog-catcher or dishwasher provide an example of a word-formation rule. Informally, word-formation rules form «new words» (that is, new lexemes), while inflection rules yield variant forms of the «same» word (lexeme).

There is a further distinction between two kinds of word-formation: derivation and compounding. Compounding is a process of word-formation that involves combining complete word-forms into a single compound form; dog-catcher is therefore a compound, because both dog and catcher are complete word-forms in their own right before the compounding process was applied, and are subsequently treated as one form. Derivation involves affixing bound (non-independent) forms to existing lexemes, whereby the addition of the affix derives a new lexeme. One example of derivation is clear in this case: the word independent is derived from the word dependent by prefixing it with the derivational prefix in-, while dependent itself is derived from dépendant, the French present participle of dépendre which means «to hang down» (and is also a cognate of the English verb depend).

The distinction between inflection and word-formation is not at all clear-cut. There are many examples where linguists fail to agree whether a given rule is inflection or word-formation. The next section will attempt to clarify this distinction.

Paradigms and morphosyntax

A paradigm is the complete set of related word-forms associated with a given lexeme. The familiar examples of paradigms are the conjugations of verbs, and the declensions of nouns. Accordingly, the word-forms of a lexeme may be arranged conveniently into tables, by classifying them according to shared inflectional categories such as tense, aspect, mood, number, gender or case. For example, the personal pronouns in English can be organized into tables, using the categories of person, number, gender and case.

The inflectional categories used to group word-forms into paradigms cannot be chosen arbitrarily; they must be grammatical categories that are relevant to stating the syntactic rules of the language. For example, person and number are grammatical categories that can be used to define paradigms in English, because English has grammatical agreement rules that require the verb in a sentence to appear in an inflectional form that matches the person and number of the subject. In other words, the syntactic rules of English care about the difference between dog and dogs, because the choice between these two forms determines which form of the verb is to be used. In contrast, however, no syntactic rule of English cares about the difference between dog and dog-catcher, or dependent and independent. The first two are just nouns, and the second two just adjectives, and they generally behave like any other noun or adjective behaves.

An important difference between inflection and word-formation is that inflected word-forms of lexemes are organized into paradigms, which are defined by the requirements of syntactic rules, whereas the rules of word-formation are not restricted by any corresponding requirements of syntax. Inflection is therefore said to be relevant to syntax, and word-formation not so. The part of morphology that covers the relationship between syntax and morphology is called morphosyntax, and it concerns itself with inflection and paradigms, but not with word-formation or compounding.

Allomorphy and morphophonology

In the exposition above, morphological rules are described as analogies between word-forms: dog is to dogs as cat is to cats, and as dish is to dishes. In this case, the analogy applies both to the form of the words and to their meaning: in each pair, the first word means «one of X», while the second «two or more of X», and the difference is always the plural form -s affixed to the second word, signaling the key distinction between singular and plural entities.

One of the largest sources of complexity in morphology is that this one-to-one correspondence between meaning and form scarcely applies to every case in the language. In English, we have word form pairs like ox/oxen, goose/geese, and sheep/sheep, where the difference between the singular and the plural is signaled in a way that departs from the regular pattern, or is not signaled at all. Even cases considered «regular», with the final -s, are not so simple; the -s in dogs is not pronounced the same way as the -s in cats, and in a plural like dishes, an «extra» vowel appears before the -s. These cases, where the same distinction is effected by alternative changes to the form of a word, are called allomorphy.

There are several kinds of allomorphy. One is pure allomorphy, where the allomorphs are just arbitrary. Other, more extreme cases of allomorphy are called suppletion, where two forms related by a morphological rule cannot be explained as being related on a phonological basis: for example, the past of go is went, which is a suppletive form.

On the other hand, other kinds of allomorphy are due to the interaction between morphology and phonology. Phonological rules constrain which sounds can appear next to each other in a language, and morphological rules, when applied blindly, would often violate phonological rules, by resulting in sound sequences that are prohibited in the language in question. For example, to form the plural of dish by simply appending an -s to the end of the word would result in the form *[dɪʃs], which is not permitted by the phonotactics of English. In order to «rescue» the word, a vowel sound is inserted between the root and the plural marker, and [dɪʃəz] results. This is an example of vowel epenthesis in English. Similar rules apply to the pronunciation of the -s in dogs and cats: it depends on the quality (voiced vs. unvoiced) of the final preceding phoneme.

The study of allomorphy that results from the interaction of morphology and phonology is called morphophonology. Many morphophonological rules fall under the category of sandhi.

Lexical morphology

Lexical morphology is the branch of morphology that deals with the lexicon, which, morphologically conceived, is the collection of lexemes in a language. As such, it concerns itself primarily with word-formation: derivation and compounding.

Models of morphology

There are three principal approaches to morphology, which each try to capture the distinctions above in different ways. These are,

- Morpheme-based morphology, which makes use of an Item-and-Arrangement approach.

- Lexeme-based morphology, which normally makes use of an Item-and-Process approach.

- Word-based morphology, which normally makes use of a Word-and-Paradigm approach.

Note that while the associations indicated between the concepts in each item in that list is very strong, it is not absolute.

Morpheme-based morphology

In morpheme-based morphology, word-forms are analyzed as sequences of morphemes. A morpheme is defined as the minimal meaningful unit of a language. In a word like independently, we say that the morphemes are in-, depend, -ent, and ly; depend is the root and the other morphemes are, in this case, derivational affixes.[1] In a word like dogs, we say that dog is the root, and that -s is an inflectional morpheme. This way of analyzing word-forms as if they were made of morphemes put after each other like beads on a string, is called Item-and-Arrangement.

The morpheme-based approach is the first one that beginners to morphology usually think of, and which laymen tend to find the most obvious. This is so to such an extent that very often beginners think that morphemes are an inevitable, fundamental notion of morphology, and many five-minute explanations of morphology are, in fact, five-minute explanations of morpheme-based morphology. This is, however, not so. The fundamental idea of morphology is that the words of a language are related to each other by different kinds of rules. Analyzing words as sequences of morphemes is a way of describing these relations, but is not the only way. In actual academic linguistics, morpheme-based morphology certainly has many adherents, but is by no means the dominant approach.

Applying a strictly morpheme-based model quickly leads to complications when one tries to analyze many forms of allomorphy. For example, the word dogs is easily broken into the root dog and the plural morpheme -s. The same analysis is straightforward for oxen, assuming the stem ox and a suppletive plural morpheme -en. How then would the same analysis «split up» the word geese into a root and a plural morpheme? In the same manner, how to split sheep?

Theorists wishing to maintain a strict morpheme-based approach often preserve the idea in cases like these by saying that geese is goose followed by a null morpheme (a morpheme that has no phonological content), and that the vowel change in the stem is a morphophonological rule. Also, morpheme-based analyses commonly posit null morphemes even in the absence of any allomorphy. For example, if the plural noun dogs is analyzed as a root dog followed by a plural morpheme -s, then one might analyze the singular dog as the root dog followed by a null morpheme for the singular.

Lexeme-based morphology

Lexeme-based morphology is (usually) an Item-and-Process approach. Instead of analyzing a word-form as a set of morphemes arranged in sequence, a word-form is said to be the result of applying rules that alter a word-form or stem in order to produce a new one. An inflectional rule takes a stem, changes it as is required by the rule, and outputs a word-form; a derivational rule takes a stem, changes it as per its own requirements, and outputs a derived stem; a compounding rule takes word-forms, and similarly outputs a compound stem.

The Item-and-Process approach bypasses the difficulties inherent in the Item-and-Arrangement approaches. Faced with a plural like geese, one is not required to assume a null morpheme: while the plural of dog is formed by affixing -s, the plural of goose is formed simply by altering the vowel in the stem.

Word-based morphology

Word-based morphology is a (usually) Word-and-Paradigm approach. This theory takes paradigms as a central notion. Instead of stating rules to combine morphemes into word-forms, or to generate word-forms from stems, word-based morphology states generalizations that hold between the forms of inflectional paradigms. The major point behind this approach is that many such generalizations are hard to state with either of the other approaches. The examples are usually drawn from fusional languages, where a given «piece» of a word, which a morpheme-based theory would call an inflectional morpheme, corresponds to a combination of grammatical categories, for example, «third person plural.» Morpheme-based theories usually have no problems with this situation, since one just says that a given morpheme has two categories. Item-and-Process theories, on the other hand, often break down in cases like these, because they all too often assume that there will be two separate rules here, one for third person, and the other for plural, but the distinction between them turns out to be artificial. Word-and-Paradigm approaches treat these as whole words that are related to each other by analogical rules. Words can be categorized based on the pattern they fit into. This applies both to existing words and to new ones. Application of a pattern different than the one that has been used historically can give rise to a new word, such as older replacing elder (where older follows the normal pattern of adjectival superlatives) and cows replacing kine (where cows fits the regular pattern of plural formation). While a Word-and-Paradigm approach can explain this easily, other approaches have difficulty with phenomena such as this.

Morphological typology

- For more information, see: Morphological typology.

In the 19th century, philologists devised a now classic classification of languages according to their morphology. According to this typology, some languages are isolating, and have little to no morphology; others are agglutinative, and their words tend to have lots of easily-separable morphemes; while others yet are fusional, because their inflectional morphemes are said to be «fused» together. The classic example of an isolating language is Chinese; the classic example of an agglutinative language is Turkish; both Latin and Greek are classic examples of fusional languages.

Considering the variability of the world’s languages, it becomes clear that this classification is not at all clear-cut, and many languages do not neatly fit any one of these types. However, examined against the light of the three general models of morphology described above, it is also clear that the classification is very much biased towards a morpheme-based conception of morphology. It makes direct use of the notion of morpheme in the definition of agglutinative and fusional languages. It describes the latter as having separate morphemes «fused» together (which often does correspond to the history of the language, but not to its synchronic reality).

The three models of morphology stem from attempts to analyze languages that more or less match different categories in this typology. The Item-and-Arrangement approach fits very naturally with agglutinative languages; while the Item-and-Process and Word-and-Paradigm approaches usually address fusional languages.

The reader should also note that the classical typology also mostly applies to inflectional morphology. There is very little fusion going on with word-formation. Languages may be classified as synthetic or analytic in their word formation, depending on the preferred way of expressing notions that are not inflectional: either by using word-formation (synthetic), or by using syntactic phrases (analytic).

Footnotes

- ↑ The existence of words like appendix and pending in English does not mean that the English word depend is analyzed into a derivational prefix de- and a root pend. While all those were indeed once related to each other by morphological rules, this was so only in Latin, not in English. English borrowed the words from French and Latin, but not the morphological rules that allowed Latin speakers to combine de- and the verb pendere ‘to hang’ into the derivative dependere.

See also

- Cranberry word

- Noun

- Verb

- Syntax

- Phonology

- Grammar

- Linguistics

Bibliography

- Anderson, Stephen R. (1992). A-Morphous Morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bauer, Laurie. (2003). Introducing linguistic morphology (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 0-878-40343-4.

- Bauer, Laurie. (2004). A glossary of morphology. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

- Bubenik, Vit. (1999). An introduction to the study of morphology. LINCON coursebooks in linguistics, 07. Muenchen: LINCOM Europa. ISBN 3-89586-570-2.

- Haspelmath, Martin. (2002). Understanding morphology. London: Arnold (co-published by Oxford University Press). ISBN 0-340-76025-7 (hb); ISBN 0-340-76206-5 (pbk).

- Katamba F & Stonham J (2006) Morphology. Basingstoke: Palgrave. 2nd edition. ISBN 1403916440.

- Matthews, Peter. (1991). Morphology (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41043-6 (hb). ISBN 0-521-42256-6 (pbk).

- Mel’čuk, Igor A. (1993-2000). Cours de morphologie générale, vol. 1-5. Montreal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

- Mel’čuk, Igor A. (2006). Aspects of the theory of morphology. Berlin: Mouton.

- Scalise, Sergio (1983). Generative Morphology, Dordrecht, Foris.

- Singh, Rajendra and Stanley Starosta (eds). (2003). Explorations in Seamless Morphology. SAGE Publications. ISBN 0-761-99594-3 (hb).

- Spencer, Andrew. (1991). Morphological theory: an introduction to word structure in generative grammar. No. 2 in Blackwell textbooks in linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-16143-0 (hb); ISBN 0-631-16144-9 (pb)

- Spencer, Andrew, & Zwicky, Arnold M. (Eds.) (1998). The handbook of morphology. Blackwell handbooks in linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-18544-5.

- Stump, Gregory T. (2001). Inflectional morphology: a theory of paradigm structure. No. 93 in Cambridge studies in linguistics. Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 0-521-78047-0 (hb).