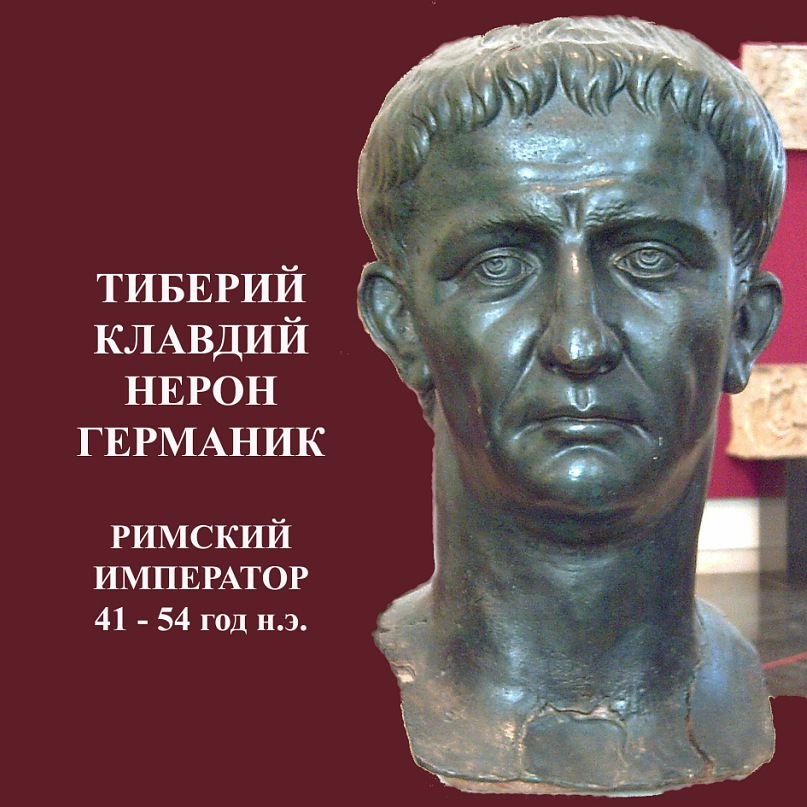

Клавдий до того, как стать императором, находился в стороне от государственных дел, ревностно занимался науками, в частности историей Рима и этрусков.

В период правления Клавдия по его личному почину был проведен ряд прогрессивных мероприятий, например, даровано полное гражданство внеиталийским общинам, что сыграло существенную роль в романизации провинций; внесены изменения в наследственное, брачное и рабское право; государственная казна возвращена в управление квесторов и др. В его время были основаны многочисленные колонии, проложены дороги и возведены технические сооружения, например, шлюз для отвода воды из Фуцинского озера и новая гавань в Остии. В этот же период к Римской империи были присоединены Южная Британия и Мавритания.

Впервые название «Лондиниум» встречается в описаниях Тацита в 61 году, но весьма возможно, что это лишь видоизмененное на римский лад кельтское название Лин-дин (Llyn-din), которое можно перевести приблизительно как «озерная крепость». Место, где возник город, было болотистым. Во время прилива воды Темзы покрывали его целиком, действительно образуя огромное озеро, над которым поднимался невысокий глинистый холм, да несколько небольших островов.

Внизу — пример типичной планировки римского города,

к «Лондиниуму» не имеющий отношения, так как в Лондоне,

по существу, не возможно вести раскопки.

Очень меня насторожило сообщение, что Клавдий «ревностно занимался историей римлян и этрусков». Дело в том, что первый Рим, построенный по наущению этрусских жрецов, был квадратным, и именно эта планировка считалась идеальной. Может быть, Квадрат прошел через всю историю Римской империи?

Как бы то ни было, через реку Темзу было необходимо построить мост, а вокруг этого места и начал естестсвенно разрастаться город «Лондиниум» сначала защищенный земляными стенами, а потом и каменными.

Вокруг «Лондиниума» была возведена одна стена, затем земляная насыпь, а в 4 веке появляется и каменная стена. По площади эта огороженная территория практически полностью повторяет очертания современного центра Лондона – района Сити. Уже в 51 году в истории встречаются упоминания о «Лондиниуме», как торговом центре всей Британии.

Римляне успели проложить почти по всей Британии 2 000 миль или 3 218 км (английская миля=1609 м) высококачественных дорог, к строительству которых они подходили очень основательно. Они проводили тщательные геодезические и землемерные работы (!) и добивались почти идеально прямых путей от одного населённого пункта к другому, причём, эти населённые пункты могли отстоять друг от друга на десятки, а то и сотни километров.Сначала строители вымеряли маршрут, затем прорывали вдоль него две параллельные канавы на заданном расстоянии друг от друга. Затем выбирали грунт между канавами до скального основания, либо до более твёрдого слоя почвы (глубина выемки грунта могла составлять до 1,5 м). А затем в получившуюся траншею укладывали слой необработанных камней, на него — слой щебня, скреплённого связующим раствором, затем слой сцементированных ещё более мелких обломков битого камня, и, наконец, мостили дорогу крупными булыжниками. «Римские» дороги — не просто утоптанный и укатанный грунт. Это сложные инженерные сооружения, по качеству и долговечности значительно превосходящие всё, что строится сегодня!

Для истории Лондона римский период имел большое значение. Уже тогда сочетание хороших сухопутных дорог (поднятых над уровнем земли на насыпях) и крупной водной артерии — Темзы — сделало город важнейшим торговым центром не только Британии, но и всей северной Европы, во многом определив его дальнейшее развитие.

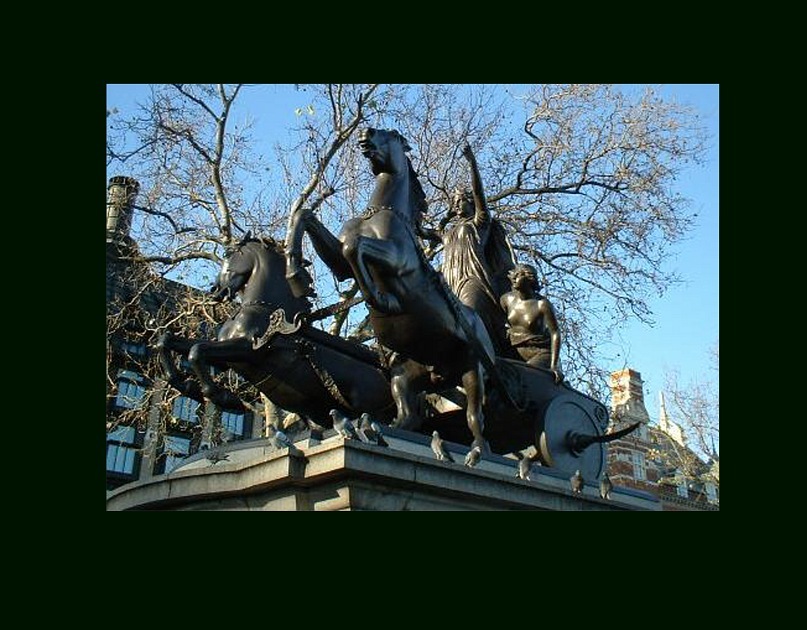

установленная в Лондоне на берегу Темзы в XIX веке.

Думаете, столь отдаленное прошлое укутано плотной дымкой временной? Ничего подобного. Главное — в другом: мимо древних свидетельств равнодушно не проходить. Останавливаемся, замерев: перед нами — конная группа «Боудикка», пытающаяся затянуть прохожих в глубину времен. Предложенным условиям подчиняемся…

Вот как описывает эту бесстрашную воительницу — кельтскую царицу — римский хроникер: «Она была женщиной огромного роста и крепкого сложения с громким и жестким голосом. Масса длинных рыжих волос спадала с ее плеч до самых колен. Она была облачена в разноцветное одеяние, носила толстое ожерелье на шее и потрясала длинным копьем, а войска встречали ее почтительным молчанием».

Как указывают римские источники, в войске Боудикки было больше женщин, столь же страшных в сражении, как и мужчины. Кельтские женщины-воительницы оказались очень жестокими и не брали пленных. Колесницы, на которых они носились по полю битвы, были легки и быстры — превосходны. Римские солдаты, впервые встретившись в бою с этими разъяренными фуриями, «словно окаменев, подставляли свои неподвижные тела под сыплющиеся на них удары».

Под 61 годом н.э. в хронологической таблице истории Великобритании отмечено неудачное восстание царицы икенов (одного из кельтских племен) Боудикки. Царица была побеждена и убита римским наместником Светонием Паулином.

Думаете, столь отдаленное прошлое укутано плотной дымкой временной? Ничего подобного. Главное — в другом: мимо древних свидетельств равнодушно не проходить. Останавливаемся, замерев: перед нами — конная группа «Боудикка», пытающаяся затянуть прохожих в глубину времен. Предложенным условиям подчиняемся: мимо монумента не прходим…

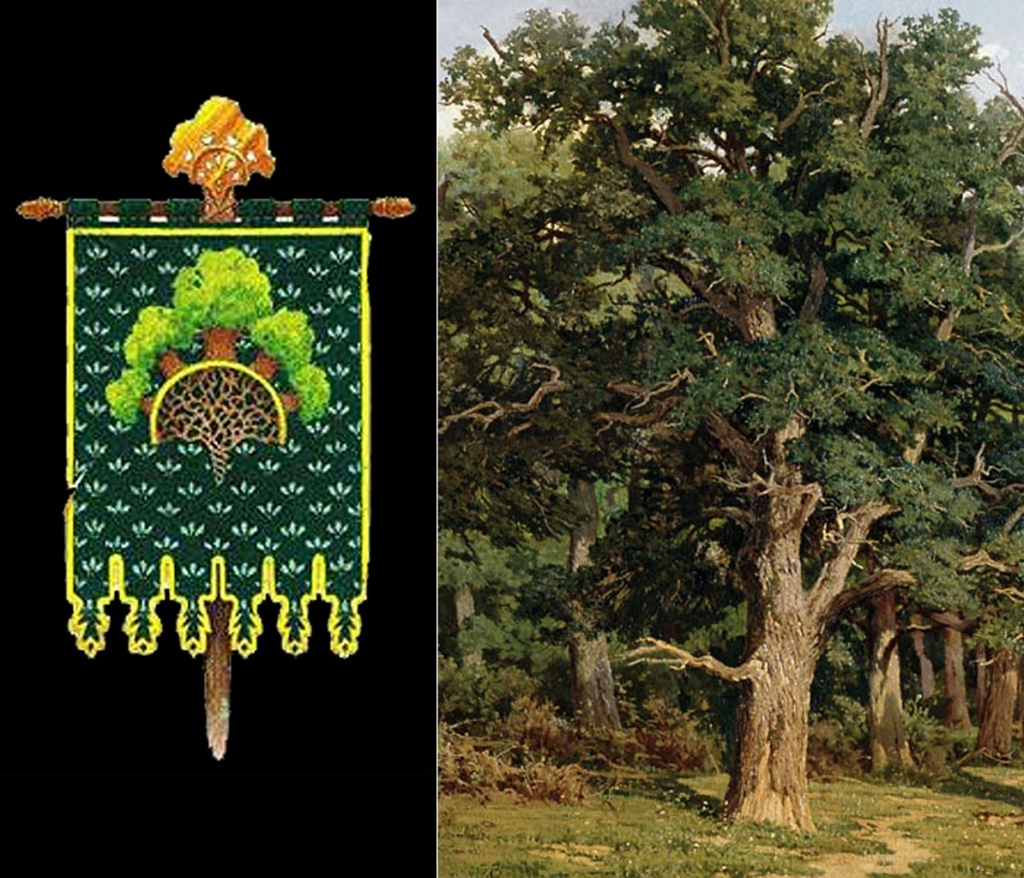

«Портрет» Дуба — Священного древа друидов

Юлий Цезарь первым из просвещенных европейцев узнал о кельтских жрецах – друидах. Друид — «Человек Дуба». Каждый друид — член ордена «Первых Посвященных». Созданные ими магические системы настолько основательны, что человечество до сих пор продолжает удивляться глубине их познаний древних могущественных сил Природы.

Великий Цезарь дважды вторгался в Британию, однако задерживаться там не стал. Лишь дань собрал и вернулся в любимую им Галлию. Ни крепости не построил, ни гарнизона не оставил. Не понравился великому полководцу гигантский, дождливый и мрачный остров?

И после него никого из завоевателей остров не привлекал. Впрочем, понять можно: ведь хлеб там почти не сеют, лишь скот разводят. А немногочисленные жители обитают в примитивных хижинах, покрытых камышом или папоротником, словно улья пчелиные. При видимой бедности острова, как мужчины, так и женщины щеголяют в золотых украшениях – кольцах и браслетах с янтарем и агатом… Значит, есть какой-то секрет… Даже легионеры, страшившиеся идти в поход за пределы известного им мира, призадумывались.

Отсутствие письменной традиции затрудняет изучение Кельтской культуры, тем не менее что-то стало известным, благодаря изустной передаче знаний от поколения к поколению.

«В эпоху сооружения мегалитов, — пишет Кэрол Кэрнак,в своей книге «Кельтская астрология «, — самые ранние из которых построены около 7000лет назад, люди выбрали на небе 36 созвездий, которые Солнце и не проходит в прямом смысле слова, но про которые считалось, что они оказывают значительное влияние на духовную и материальную жизнь человека. Поэтому год разделили на 36 периодов приблизительно по 10 дней каждый». Каждому из 36 созвездий кельтские астрологи приписали свою легенду. Каждая символически, в краткой форме описывала основные склонности психологического порядка и главные направления судьбы того, кто, будучи рожден в тот или иной период, испытывает на себе влияние соответствующих сил. Кроме того, с каждым из этих знаков ассоциировалось какое-нибудь дерево — нам известно, какое важное значение придавали лесу в друидском обществе. Каждый знак вступает в свои отношения с остальными 35 знаками: дружба или враждебность, равнодушие или страстное влечение, — и все в соответствии с широчайшей и тонко разработанной гаммой психологических отношений.

В 43 году римляне развернули наступление, применяя баллисты против племён, вооруженных лишь луками и пращами. Кельты сдались. Клавдий счел, что наконец-то он прибавил к Римской империи провинцию Британия.

КЕЛЬТЫ смирились со своей участью?

КЕЛЬТЫ понимали, что все начавшееся должно закончиться,

следуя по прямой и обратной Спирали Времен?

Или живущие в слаборазвитой цивилизации КЕЛЬТЫ верили,

что, набравшись сил, они вернут свой Мир,

опираясь на свою — высочайшую — культуру?

Нет ответов. Не будем спешить…

установленная на берегу Темзы возле Вестминстерского дворца

В 61 году новой эры произошло восстание в Норфолке под предводительством царицы Боудикки — жены Прасутага, вождя кельтского племени иценов. Он занял денег у императора Нерона, а перед смертью назначил его наследником своих земель вместе с двумя своими юными дочерьми. После смерти Прасутага в 60 году Нерон потребовал немедленной выплаты долгов, а когда выяснилось, что платить кельтам нечем, их земли были захвачены.Боудикку подвергли публичной порке, а обеих дочерей отдали на потеху римским солдатам.

Воспользовавшись отсутствием главной римской армии, находившейся в это время в Уэльсе, оскорбленная царица кельтов Боудикка подняла восстание, которое быстро распространилось на большую часть острова. Было истреблено до 70 000 римских колонистов и романизированных кельтов. Боудика захватила и сожгла римский город Лондиниум.

Потрясённые римляне соединили свои отряды и встретили армию Боудикки в центре Британии, где, благодаря превосходной организованности, римлянам удалось нанести тяжкое поражение превосходящим силам противника. Согласно римским источникам, на поле битвы было убито 80 000 бриттов, а потери римлян составили лишь 400 солдат. По устоявшемуся мнению, битва произошла на месте современного вокзала Кингс-Кросс. При отступлении в огромный лес к северо-востоку от Лондона, ныне известный как Эппинг Форест, кельтская царица и ее дочери приняли яд, чтобы избежать плена.

установленная на берегу Темзы возле Вестминстерского дворца

Вот как описывает эту бесстрашную воительницу — кельтскую царицу — римский хроникер: «Она была женщиной огромного роста и крепкого сложения с громким и жестким голосом. Масса длинных рыжих волос спадала с ее плеч до самых колен. Она была облачена в разноцветное одеяние, носила толстое ожерелье на шее и потрясала длинным копьем, а войска встречали ее почтительным молчанием».

Как указывают римские источники, в войске Боудикки было больше женщин, столь же страшных в сражении, как и мужчины. Кельтские женщины-воительницы оказались очень жестокими и не брали пленных. Колесницы, на которых они носились по полю битвы, были легки и быстры — превосходны. Римские солдаты, впервые встретившись в бою с этими разъяренными фуриями, «словно окаменев, подставляли свои неподвижные тела под сыплющиеся на них удары».

установленная в Лондоне на берегу Темзы

Имя царицы иценов происходит от кельтского слова bouda — победа. Слово boudīko значило у кельтов «победоносный». В настоящее время считается правильным произношение этого имени как Боудикка (по правилам валлийского и ирландского языков, наиболее близких к кельтскому).

История восстания Боудики дошла до наших дней. И хотя ничего выдающегося ей не удалось совершить, ровно как и выиграть решающие сражение или освободить свой народ от власти Рима, она осталась в памяти британцев как символ борьбы за свободу, что пришел в нынешний день из далекого прошлого.

В XIX веке, в период правления британской королевы Виктории, фигура Боудикки была окружена своеобразным романтическим культом — не в последнюю очередь потому, что её имя значит «победа» (как и имя Виктория).

Римляне отстроили сожженный Боудиккой «Лондиниум». Первые постройки возникли на холме Корн-хилл, далее город распространился и на лежащий западнее холм Сент-Пол-Хилл. Кварталы близ центра были застроены кирпичными и каменными домами, располагавшимися торцами к улицам, как того требовала прямоугольная планиметрия. Дома были весьма комфортабельны: в раскопках обнаружены не только фрагменты росписей и мозаик, но и остатки ванных комнат и устройств воздушного отопления.

Вначале город находился под защитой небольшого форта, расположенного северо-западнее поселения. Следы его прямоугольной планировки, обычной для римского военного лагеря, сохраняют направления современных улиц южнее Грипплс-Гейт.

С 98 по 117 год Римским императором был Траян (Ма́рк, У́льпий, Не́рва, Трая́н) — идеальный правитель в глазах рабовладельческой знати. Он вел непрерывные завоевательные войны — победоносные.

Принято считать, что к 100 году новой эры Римская империя достигла наивысшего могущества. Тогда же началось распространение христианства.

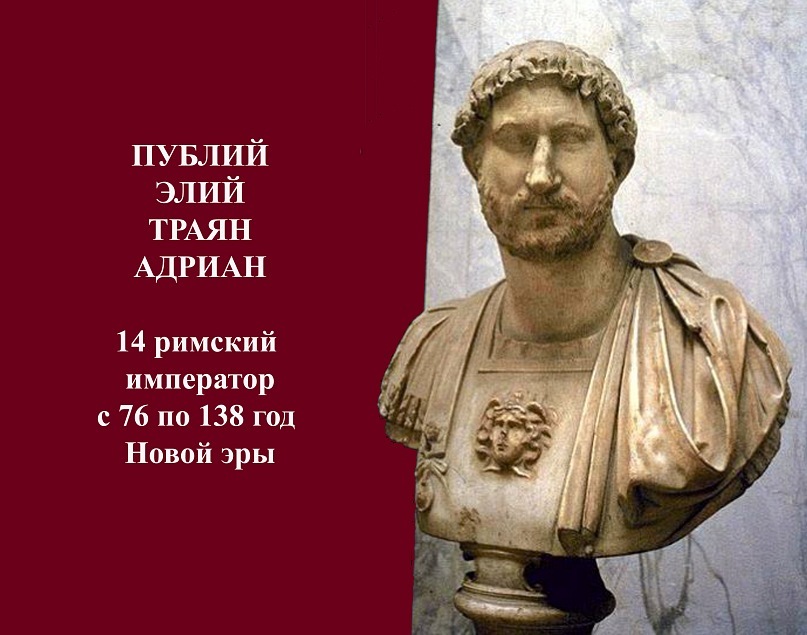

В 117-138 годы правит император Адриан (Публий, Элий, Траян, Адриан). При нем происходит усиление императорской власти и централизация государственных учреждений. Главное внимание Четырнадцатый император уделяет защите безопасности границ своей империи.

Вал Адриана («Стена Адриана») — укрепление из камня и торфа, построенное между 122 и 126 годами поперёк острова Британия для предотвращения набегов каледонцев с севера, и для защиты провинции Британии к югу от стены. Длина вала — 117 км, ширина — 3 м, высота — 5-6 м. На востоке это была каменная стена, на западе — дерновый вал. По всей длине вала через определенные промежутки стояли наблюдательные башни, а за ними располагалось 16 фортов, с обеих сторон шли рвы.

После того как был построен еще один вал — Антонина, за «Стеной Адриана» никто не следил, и она постепенно разрушалась. В 209 году император Андроник Север приказал укрепить вал Адриана, установив по нему границу римских владений.

Какое-то особое мироощущение нужно иметь,

чтобы идти по Земле бесконечными путями…

Расширяя границы своего государства?

О всеобщем мире и покое мечтая?

Основное внимание император Адриан отдавал экономическому развитию провинций. По всей стране строились театры, библиотеки, города украшались множеством статуй. В Риме сооружен мавзолей Адриана, так называемый замок Святого Ангела, построена знаменитая вилла в Тибуре, проведен канал от Стимфало в Коринф.

Адриан высоко ценил греческую культуру, поощряя искусства, поэзию, философию. Он создал совет при своей особе. Италию разделил на 4 части с четырьмя императорскими консулами, на государственные должности назначал только римлян. Последним крупным мероприятием Адриана стала кодификация римского права, проведённая совместно с юристом Сальвием Юлианом.

В 138 году император сильно заболел. Страдая от болезни, он принял сильную дозу лекарства и умер в Британии — в Байях, оставив наследником усыновленного им Антонина Пия. Перед смертью император написал себе эпитафию…

Трепетная душа, нежная странница

Гость и друг в человеческом теле,

Где ты сейчас скитаешься,

Ослабленная, продрогшая, беззащитная,

Неспособная играть, как прежде?

Император Адриан играл в своем Театре, возводя на сцене

абсолютно прекрасную греческую архитектуру и с ее помощью разговаривая с Вечностью,что открывалась перед ним Безграничность просторов, бесконечностью времен.

В 150-е годы был построен еще один вал — Антонина. За «Стеной Адриана» перестали следить, и она постепенно разрушалась.

В 209 году император Андроник Север приказал укрепить вал Адриана, установив по нему границу римских владений. Пикты несколько раз пробивали в валу проходы, и римляне в конце концов в 385 году оставили его разрушаться.

По мере того, как Римская империя приходила в упадок и ее легионы становились слабее, вокруг «Лондиниума» возводились все более мощные укрепления. Во II веке было начато продолжавшееся несколько десятилетий строительство стены вокруг города. Сложенная из кентского известняка и имевшая толщину около 3 метров, она многие столетия подновлялась и дополнялась, сохраняя свои общие очертания и значение важнейшего элемента в структуре города.

В IV веке «Лондиниум» стал все чаще подвергаться набегам варваров из Северной Европы. Торговля пришла в упадок, население уменьшалось. Наконец, в 410 году император Гонорий отозвал римские легионы из Британии и «Лондиниум» на многие десятилетия был заброшен.

Римляне сидели в Британии четыреста лет. Очень долго. Но в конце концов вынуждены были уйти. По простой причине: многие века они захватывали и колонизировали другие народы и земли. Теперь к стенам Вечного Города подступали вестготы.

Римляне уходили из Британии постепенно. И после того, как последний римский легион покинул Остров в 407 году, в Британии осталось немало римлян. Остались легионеры, владевшие землей, пожалованной за хорошую службу, те, что обзавелись в Британии семьей, купцы. Ассимилировавшиеся представители аристократии римской, связанные супружескими узами с аристократией кельтской, породили новый правящий класс — британскую знать.

Но были и такие, кто приветствовал уход захватчиков. Ведь очаги антиримского сопротивления тлели в Британии все четыреста лет оккупации. Главы кланов постоянно поднимали мятежи и восстания. И хотя легионы стояли на Валу Антонина, тем не менее во многих районах власть Рима практически отсутствовала. А когда римлян поубавилось, кланы незамедлительно кинулись друг на друга. Началась долгая и упорная борьба за власть и господство.

Отсутствие римских легионов и воцарившийся хаос тут же привлекли внимание соседей. На западных побережьях замелькали паруса ирландских пиратов, в те времена именовавшихся скоттами. А с севера, форсируя покинутые римлянами Валы Антонина и Адриана, хлынули на юг неистребимые пикты.

Сторонники проримской ориентации несколько раз обращались за помощью к Империи, но в ответ слышали одно: «Провинция Британия Империю не интересует. Британия — территория самоуправляемая и независимая, так что должна сама разрешать свои проблемы. Помощь от Рима не придет. У Рима много других, более важных дел».

Все закончилось, господа,

ибо всегда все, когда-либо начавшееся,

когда-нибудь непременно заканчивается…

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A tablet from c. 65 AD, reading «Londinio Mogontio»- «In London, to Mogontius»

The name of London is derived from a word first attested, in Latinised form, as Londinium. By the first century CE, this was a commercial centre in Roman Britain.

The etymology of the name is uncertain. There is a long history of mythicising etymologies, such as the twelfth-century Historia Regum Britanniae asserting that the city’s name is derived from the name of King Lud who once controlled the city. However, in recent times a series of alternative theories have also been proposed. As of 2017, the trend in scholarly publications supports derivation from a Brittonic form *Londonjon, which would itself have been of Celtic origin.[1][2]

Attested forms[edit]

Richard Coates, in the 1998 article where he published his own theory of the etymology, lists all the known occurrences of the name up to around the year 900, in Greek, Latin, British and Anglo-Saxon.[3] Most of the older sources begin with Londin- (Λονδίνιον, Londino, Londinium etc.), though there are some in Lundin-. Later examples are mostly Lundon- or London-, and all the Anglo-Saxon examples have Lunden- with various terminations. He observes that the modern spelling with <o> derives from a medieval writing habit of avoiding <u> between letters composed of minims.

The earliest written mention of London occurs in a letter discovered in London in 2016. Dated AD 65–80, it reads Londinio Mogontio which translates to «In London, to Mogontius».[4][5][6][7] Mogontio, Mogontiacum is also the Celtic name of the German city Mainz.

Phonology[edit]

Coates (1998) asserts that «It is quite clear that these vowel letters in the earliest forms [viz., Londinium, Lundinium], both <o> and <u>, represent phonemically long vowel sounds». He observes that the ending in Latin sources before 600 is always -inium, which points to a British double termination -in-jo-n.

However, it has long been observed that the proposed Common Brittonic name *Londinjon cannot give either the known Anglo-Saxon form Lunden, or the Welsh form Llundein. Following regular sound changes in the two languages, the Welsh name would have been *Lunnen or similar, and Old English would be *Lynden via i-mutation.[8]

Coates (1998) tentatively accepts the argument by Jackson (1938)[9] that the British form was -on-jo-n, with the change to -inium unexplained. Coates speculates further that the first -i- could have arisen by metathesis of the -i- in the last syllable of his own suggested etymon (see below).

Peter Schrijver (2013) by way of explaining the medieval forms Lunden and Llundein considers two possibilities:

- In the local dialect of Lowland British Celtic, which later became extinct, -ond- became -und- regularly, and -ī- became -ei-, leading to Lundeinjon, later Lundein. The Welsh and English forms were then borrowed from this. This hypothesis requires that the Latin form have a long ī: Londīnium.

- The early British Latin dialect probably developed similarly as the dialect of Gaul (the ancestor of Old French). In particular, Latin stressed short i developed first into close-mid /e/, then diphthongised to /ei/. The combination -ond- also developed regularly into -und- in pre-Old French. Thus, he concludes, the remaining Romans of Britain would have pronounced the name as Lundeiniu, later Lundein, from which the Welsh and English forms were then borrowed. This hypothesis requires that the Latin form have a short i: Londinium.

Schrijver therefore concludes that the name of Londinium underwent phonological changes in a local dialect (either British Celtic or British Latin) and that the recorded medieval forms in Welsh and Anglo-Saxon would have been derived from that dialectal pronunciation.

Proposed etymologies[edit]

Celtic[edit]

Coates says (p. 211) that «The earliest non-mythic speculation … centred on the possibility of deriving London from Welsh Llyn din, supposedly ‘lake fort’. But llyn derives from British *lind-, which is incompatible with all the early attestations.[3] Another suggestion, published in The Geographical Journal in 1899, is that the area of London was previously settled by Belgae who named their outposts after townships in Gallia Belgica. Some of these Belgic toponyms have been attributed to the namesake of London including Limé, Douvrend, and Londinières.[10]

H. D’Arbois de Jubainville suggested in 1899 that the name meant Londino’s fortress.[11] But Coates argues that there is no such personal name recorded, and that D’Arbois’ suggested etymology for it (from Celtic *londo-, ‘fierce’) would have a short vowel. Coates notes that this theory was repeated by linguistics up to the 1960s, and more recently still in less specialist works. It was revived in 2013 by Peter Schrijver, who suggested that the sense of the proto-Indo-European root *lendh— (‘sink, cause to sink’), which gave rise to the Celtic noun *londos (‘a subduing’), survived in Celtic. Combined with the Celtic suffix *-injo— (used to form singular nouns from collective ones), this could explain a Celtic form *londinjon ‘place that floods (periodically, tidally)’. This, in Schrijver’s reading, would more readily explain all the Latin, Welsh, and English forms.[1] Similar approaches to Schrijver’s have been taken by Theodora Bynon, who in 2016 supported a similar Celtic etymology, while demonstrating that the place-name was borrowed into the West Germanic ancestor-language of Old English, not into Old English itself.[2]

Coates (1998) proposes a Common Brittonic form of either *Lōondonjon or *Lōnidonjon, which would have become *Lūndonjon and hence Lūndein or Lūndyn. An advantage of the form *Lōnidonjon is that it could account for Latin Londinium by metathesis to *Lōnodinjon. The etymology of this *Lōondonjon would however lie in pre-Celtic Old European hydronymy, from a hydronym *Plowonida, which would have been applied to the Thames where it becomes too wide to ford, in the vicinity of London. The settlement on its banks would then be named from the hydronym with the suffix -on-jon, giving *Plowonidonjon and Insular Celtic *Lowonidonjon. According to this approach, the name of the river itself would be derived from the Indo-European roots *plew- «to flow, swim; boat» and *nejd- «to flow», found in various river names around Europe. Coates does admit that compound names are comparatively rare for rivers in the Indo-European area, but they are not entirely unknown.[3] Lacey Wallace describes the derivation as «somewhat tenuous».[12]

Non-Celtic[edit]

Among the first scientific explanations was one by Giovanni Alessio in 1951.[3][13] He proposed a Ligurian rather than a Celtic origin, with a root *lond-/lont- meaning ‘mud’ or ‘marsh’. Coates’ major criticisms are that this does not have the required long vowel (an alternative form Alessio proposes, *lōna, has the long vowel, but lacks the required consonant), and that there is no evidence of Ligurian in Britain.

Jean-Gabriel Gigot in a 1974 article discusses the toponym of Saint-Martin-de-Londres, a commune in the French Hérault département. Gigot derives this Londres from a Germanic root *lohna, and argues that the British toponym may also be from that source.[14] But a Germanic etymology is rejected by most specialists.[15]

Historical and popular suggestions[edit]

The earliest account of the toponym’s derivation can be attributed to Geoffrey of Monmouth. In Historia Regum Britanniae, the name is described as originating from King Lud, who seized the city Trinovantum and ordered it to be renamed in his honour as Kaerlud. This eventually developed into Karelundein and then London. However, Geoffrey’s work contains many fanciful suppositions about place-name derivation and the suggestion has no basis in linguistics.[16]

Other fanciful theories over the years have been:

- William Camden reportedly suggested that the name might come from Brythonic lhwn (modern Welsh Llwyn), meaning «grove», and «town». Thus, giving the origin as Lhwn Town, translating to «city in the grove».[17]

- John Jackson, writing in the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1792,[18] challenges the Llyn din theory (see below) on geographical grounds, and suggests instead a derivation from Glynn din – presumably intended as ‘valley city’.

- Some British Israelites claimed that the Anglo-Saxons, assumed to be descendants of the Tribe of Dan, named their settlement lan-dan, meaning «abode of Dan» in Hebrew.[19]

- An unsigned article in The Cambro Briton for 1821[20] supports the suggestion of Luna din (‘moon fortress’), and also mentions in passing the possibility of Llong din (‘ship fortress’).

- Several theories were discussed in the pages of Notes and Queries on 27 December 1851,[21] including Luandun (supposedly «city of the moon», a reference to the temple of Diana supposed to have stood on the site of St Paul’s Cathedral), and Lan Dian or Llan Dian («temple of Diana»). Another correspondent dismissed these, and reiterated the common Llyn din theory.

- In The Cymry of ’76 (1855),[22] Alexander Jones says that the Welsh name derives from Llyn Dain, meaning ‘pool of the Thames’.

- An 1887 Handbook for Travellers[23] asserts that «The etymology of London is the same as that of Lincoln» (Latin Lindum).

- The general Henri-Nicolas Frey, in his 1894 book Annamites et extrême-occidentaux: recherches sur l’origine des langues,[24] emphasises the similarity between the name of the city and the two Vietnamese words lœun and dœun which can both mean «low, inferior, muddy».

- Edward P. Cheney, in his 1904 book A Short History of England (p. 18), attributes the origin of the name to dun: «Elevated and easily defensible spots were chosen [in pre-Roman times], earthworks thrown up, always in a circular form, and palisades placed upon these. Such a fortification was called a dun, and London and the names of many other places still preserve that termination in varying forms.»

- A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare (1918)[25] mentions a variant on Geoffrey’s suggestion being Lud’s town, although refutes it saying that the origin of the name was most likely Saxon.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Peter Schrijver, Language Contact and the Origins of the Germanic Languages, Routledge Studies in Linguistics, 13 (New York: Routledge, 2014), p. 57.

- ^ a b Theodora Bynon, ‘London’s Name’, Transactions of the Philological Society, 114:3 (2016), 281–97, doi: 10.1111/1467-968X.12064.

- ^ a b c d Coates, Richard (1998). «A new explanation of the name of London». Transactions of the Philological Society. 96 (2): 203–229. doi:10.1111/1467-968X.00027.

- ^ «Earliest written reference to London found», on Current Archaeology, 1 June 2016. Retrieved on 26 January 2018.

- ^ «UK’s oldest hand-written document ‘at Roman London dig'», on BBC News, 1 June 2016. Retrieved on 26 January 2018.

- ^ «Oldest handwritten documents in UK unearthed in London dig», in The Guardian, 1 June 2016. Retrieved on 26 January 2018.

- ^ «Oldest reference to Roman London found in new tube station entrance», on IanVisits, 1 June 2016. Retrieved on 2022-11-27.

- ^ Peter Schrijver, Language Contact and the Origins of the Germanic Languages (2013), p. 57.

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth H. (1938). «Nennius and the 28 cities of Britain». Antiquity. 12: 44–55. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00013405. S2CID 163506021.

- ^ «The Geographical Journal». The Geographical Journal. 1899.

- ^ D’Arbois de Jubainville, H (1899). La Civilisation des Celtes et celle de l’épopée homérique (in French). Paris: Albert Fontemoing.

- ^ Wallace, Lacey (2015). The Origin of Roman London. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 9781107047570.

- ^ Alessio, Giovanni (1951). «L’origine du nom de Londres». Actes et Mémoires du troisième congrès international de toponymie et d’anthroponymie (in French). Louvain: Instituut voor naamkunde. pp. 223–224.

- ^ Gigot, Jean-Gabriel (1974). «Notes sur le toponyme «Londres» (Hérault)». Revue international d’onomastique. 26: 284–292. doi:10.3406/rio.1974.2193. S2CID 249329873.

- ^ Ernest Nègre, Toponymie générale de la France, Librairie Droz, Genève, p. 1494 [1]

- ^ Legends of London’s Origins

- ^ Prickett, Frederick (1842). «The history and antiquities of Highgate, Middlesex»: 4.

- ^ Jackson, John (1792). «Conjecture on the Etymology of London». The Gentleman’s Magazine. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

- ^ Gold, David L (1979). «English words of supposed Hebrew origin in George Crabb’s «English Synonymes»«. American Speech. Duke University Press. 51 (1): 61–64. doi:10.2307/454531. JSTOR 454531.

- ^ «Etymology of ‘London’«. The Cambro Briton: 42–43. 1821.

- ^ «Notes and Queries». 1852.

- ^ Jones, Alexander (1855). The Cymry of ’76. New York: Sheldon, Lamport. p. 132.

etymology of london.

- ^ Baedeker, Karl (1887). London and Its Environs: Handbook for Travellers. K. Baedeker. p. 60.

- ^ Henry, Frey (1894). Annamites et extrême-occidentaux: recherches sur l’origine des langues. Hachette et Cie.

- ^ Furness, Horace Howard, ed. (1918). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare. J B Lippincott & co. ISBN 0-486-21187-8.

Exercise

1.

Complete the

sentences using “which”, “who”, “whose”, “whom”,

“where”:

1.

The name “Londinium” is derived from the Celtic word Llyn-din, …

means literally “river place”. 2. The official head of the UK is

the Queen, … reigns but doesn’t rule. 3. Yesterday I met a

friend of mine … wife is an English teacher. 4. The Thames, …

has always been the part of London history, is often called Father

of London. 5. Many people think that Big Ben was named after Sir

Benjamin Hall, a British civil engineer, … was put in charge of

the Clock Tower, but this is questionable. 6. Do you know a

restaurant … we can have a really good meal? 7. I don’t know the

name of the woman to … I spoke on the phone. 8. A mountaineer is a

person … ambition is to climb Everest. 8. The building … was

destroyed in the fire has now been rebuilt.

*Exercise

2.

Mark

the border between the sentences where the conjunction is left out.

Read the sentences paying attention to the intonation.

Model:

The people I talked to during my trip were very friendly. →

The

people [who]

I talked to during my trip were very friendly.

1.

The book he read yesterday was about history of London. 2. The

museum we wanted to visit was shut when we got there. 3. Are these

the keys you were looking for? 4. The man I was sitting next to on

the plane talked all the time. 5. Everything they said was true. 6.

The woman I wanted to see was away. 7. What’s the name of the film

you are going to see? 8. It was the most boring film I‘ve ever

seen.

Exercise

3. Use the Present or the Future Indefinite Tense. § 8.2.

Model:

I (to help) you when I (to be) free. → I’ll

help

you when

I am

free.

1.

It (to take) you ten minutes if you (to take) a taxi. 2. I (to know)

something about London after I (to make) a trip there. 3. If you (to

want) to see all these places, you must stay here for a week. 4.

When you (to cross) the street in London, look first to the right

because of the traffic rules. 5. As soon as you (to turn) the corner

you (to see) the Russian Embassy right in front of you. 6. Let’s

wait till the green light (to be) on. 7. When you (to get off) the

bus, I (to be) there. 8. We (to meet) before he (to leave) for

London. 9. I (to ask) a policeman in the street if I (to be) lost.

**Exercise

4.

Use

the verbs in brackets in the correct tense form (Active or Passive).

Translate the text.

An Old Legend

The

six ravens (to keep) in the Tower of London now for centuries. They

used to come in from Essex for food scraps when the Tower (to use)

as a palace. Over the years people (to think) that if the ravens

ever left the Tower, the monarchy would fall. So Charles II (to

decree) that six ravens should always (to keep) in the Tower and

should (to pay) a wage from the treasury. In those times the White

Tower was home to the Royal Observatory, and when the King (to tell)

that the ravens got in the way of the observations, he (to move) the

astronomer instead. Since then, the Observatory (to be situated) in

Greenwich, and three pairs of breeding ravens (to be) a permanent

feature of the Tower, cared for by the Raven Master. Sometimes they

(to live) as long as 25 years, but their wings (to clip) so they

can’t fly away, and when a raven (to die), another raven (to

bring) from Essex.

Exercise

5.

Translate

the sentences paying attention to the phrasal verbs.

1.

He kept

on

talking after everybody asked him to stop. 2. I don’t think he

killed those men. Somebody set

him up.

3. A new parliamentary committee was set

up

yesterday. 4. Keep your back straight when you pick

up

something heavy. 5. What time are you going to pick

me up?

6. It’s possible to pick

up

enough English in three weeks before your trip to London. 7. Meg

dropped

in

yesterday after dinner. 8. Jimmie isn’t on the team any more. He

dropped

out.

9. My sister gets

away

with everything! 10. Natasha doesn’t get

on

with her co-workers. 11. The bus was full, so it was difficult both

to

get on and

to get off.

*Exercise

6.

Insert

the phrasal verbs from exercise 5.

1.

… your English! 2. Though he has been told not to smoke at the

office, he … smoking every half-hour. 3. I didn’t do anything

wrong. They … me …! 4. A school based on absolutely new

principles … 5 years ago by this outstanding educationist. 5.

Let’s …on Julie since we’re driving by her house. 6. It’s

difficult to get a good job if you …of high school. 7. Could you

…me … at the airport tomorrow and …at Harrods’s? 8. The

train is leaving. Quick, …! 9. The gangsters … with a murder.

10. Do you … with your neighbors? 11. We’ll have to … to

change for Bus No. 5.

Exercise

7.

Match

the modal verbs and their meanings. § 10.

(b)

physical

or mental

ability

/disability (a) probability

(c)

impossibility

(d) possibility

in a

particular situation (e)

politeness (f)

-

He

can

play tennis well and speak Chinese. -

I

haven’t

been able to

sleep recently. -

It’s

cloudy; it may

/might

rain in the evening. -

May

/ can

I take your book? -

Could

you leave me a message, please? -

We

have just had lunch. You can’t

(cannot) be

hungry. -

She

wasn’t at home when I phoned but I was

able to

contact her at her office.

Exercise

8. Complete

the sentences

using “can, can’t, could, couldn’t”.

1.

I’m afraid I … come to your party next week. 2. When Tim was 16,

he was a fast runner. He … run 100 metres in 11 seconds. 3. “Are

you in a hurry?” “No, I’ve got plenty of time. I … wait”.

4. I was feeling sick yesterday. I … eat anything. 5. Can you

speak up a bit? I … hear you very well. 6. “You look tired”.

“Yes, I … sleep last night”. 7. … you be so kind to tell me

the time, please?

*Exercise

9. Use “can” if possible; otherwise use “be able to”. §

10.1.

1.

George has traveled a lot. He … speak three languages. 2. Martin

is an eccentric. I’ve never … understand him. 3. Tom might …

come tomorrow. 4. Sandra … drive but she hasn’t got a car. 5.

I’m very busy on Friday but I … meet you on Saturday morning. 6.

Ask Catherine about your problem. She might … help you. 7. I would

like to … swim well. 8. She used to … dance very well but she …

not do it now.

*Exercise

10.

Paraphrase

using “couldn’t” (in the negative sentence) or “was / were

able to” (in the affirmative sentence). § 10.1.

1.

Everybody managed

to

escape from the fire. 2. Jack and Paul played tennis yesterday; Jack

played very well but in the end Paul managed to beat him. 3. I

looked everywhere for the book but I didn’t manage to find it. 4.

Tom managed to finish his work that afternoon. 5. I had forgotten to

bring my camera so I didn’t manage to take any pictures. 6. They

didn’t want to come with us and nobody managed to persuade

(убеждать)

them. 7. Ann had given us good directions, so we managed to get

there in time.

Exercise

11. Paraphrase using “may or might” according to the structures.

§

10.2.

-

He

may / might be in his office.Present

He

may / might be doing the task.Continuous

He

may / might have (not) done it.Past

1.

Perhaps Margaret is busy.

-

Perhaps

she didn’t know about it. -

Perhaps

she is working now. -

Perhaps

she wants to be alone. -

Perhaps

she was ill yesterday. -

Perhaps

she went home early. -

Perhaps

she is having lunch. -

Perhaps

she didn’t see you. -

Perhaps

she didn’t leave you a message.

Exercise

12. Match the modal verbs and their meanings. § 10.3.

logical

necessity (b)

moral

or social

obligation

/duty (a) personal

obligation (c)

advice or

expectation or plan (e)

opinion

(d)

absence

of necessity (f) probability (g)

-

You

must

work hard in order to pass the exam successfully. -

Peter

is tall and strong, he must

be a good sportsman. -

In

Britain schoolchildren have

to wear

uniform. -

The

delegation is

to

arrive on Monday. -

You

should

eat more fruit and vegetables. -

We

needn’t

hurry. We’ve got plenty of time. -

I

ought

to

pay our debts.

*Exercise

13. Put in “must or cannot”. § 10.

1.

You’ve been travelling all day. You … be

tired. 2.

That restaurant … be very good. It’s always full of people. 3.

That restaurant … be very good. It’s always empty. 4. It rained

every day during their holiday, so they … have had a very nice

time. 5. You got here very quickly. You … have walked very fast.

6. Congratulations on passing your exam. You … be very pleased. 7.

Jim is a hard worker. – You … be joking. He is very lazy.

*Exercise

14. Put

in “must or have to”. § 10.3, 10.4.

1.

She

is a really nice person. You …

meet

her. 2. You

…

turn

left here because of the traffic system. 3. My

eyesight isn’t very good. I … wear glasses for reading. 4. I

haven’t phoned Ann for ages. I … phone her tonight. 5. Last

night Nick became ill suddenly. We … call a doctor. 6. When you

come to London again, you … come and see us. 7. I’m sorry I

couldn’t come yesterday. I … work late. 8. Caroline may … go

away next week. 9. I … get up early tomorrow. There are a lot of

things I want to do.

Exercise

15.

Write

a sentence with “should

or

shouldn’t”

+ one of the following:

go

to bed so late; look for another job; put some pictures on he walls;

take a photograph; use her car so much.

§

10.7.

1.

My salary is very low. – You … .

2.

Jack always has difficulty getting up. He … .

3.

What a beautiful view! You … .

4.

Sue drives everywhere. She never walks. She … .

5.

Bill’s room isn’t very interesting. He … .

Exercise

16. Paraphrase using “be to”. § 10.5.

Model

1: I expect

her to come and help. → She is

to come

and help.

Model

2: It was

planned that we should wait for them at the door. → We were

to wait for

them at the door.

1.

The lecture is supposed to begin at 12 o’clock. 2. It was arranged

that he should meet her at the station. 3. The tourists expected the

guide to show them around the Tower of London. 4. It is planned that

she will wait for them at the entrance. 5. The train is supposed to

arrive on time. 6. I expected you to leave me a message. 7. It was

arranged that all the students would take part in the conference.

**Exercise

17.

Complete

the sentences using “could, must, was to, had to, might,

shouldn’t, will be able to, needn’t, ought to”. §10.

1.

Ted isn’t at work today, he …

be ill. 2.

My grandfather was a very clever man. He … speak five languages.

3. You look tired. You …

work so hard. 4. It was raining hard and we … wait until it

stopped. 5.

You … buy the tickets now, you can book them in advance. 6. As

they had agreed before, Tom … wait for his girlfriend at the

entrance. 7. Children … take care of their parents. 8. I hope he …

speak English well next year. 9. Where are you going for your

holidays? – I haven’t decided yet. I … go to London.

*Exercise

18. Define

the functions of the numbered forms of the Infinitive used in the

text and mark them in the table. Entitle the text. § 11.1.

In

1050 King Edward the Confessor, a very religious man, started to

build (1) a great

church, called Westminster Abbey. To

keep (2) a close

eye on its construction, Edward also built a new home between the

abbey and the river – the Palace of Westminster. It took fifteen

years to erect

(3) the abbey, but its creator couldn’t be happy to

have finished (4)

it because soon after the consecration (освящение)

he died and was buried there.

In

the 1200s King Henry III decided to

pull down (5)

Edward’s abbey and began building the more beautiful one after the

Gothic style then prevailing in France – the church we see today.

To visit

(6) Westminster Abbey is worthwhile if you are interested in British

history. It is the chief church of England, and since 1308 every

king or queen has been crowned there, except for two: Edward V who

was murdered in the Tower of London in 1483, and Edward VII who

abdicated in 1936.

According

to a tradition, the Coronation Chair, carved from oak, is to

be used (7) for

the ceremony of crowning every monarch. Besides, Westminster Abbey

has burial places of many monarchs and great men; Geoffrey Chaucer

was the first poet to

be buried (8)

there in 1400. Isaac Newton’s monument is one of the most

interesting in Westminster Abbey, it is known to

have been executed

(9) in 1731 by the sculptor Michael Rysbrack in white and grey

marble.

The

abbey has also been the place of royal weddings. In 1947 Princess

Elizabeth (the future Queen) was married there to the Duke of

Edinburgh; the marriage took place in the early post-war years, and

Elizabeth still required ration coupons (талоны)

to buy

(10) the material for her gown. The last wedding in April 2011, when

Prince William, Elizabeth’s grandson, was married to Miss

Catherine Middleton, was probably the grandest wedding to

be performed (11)

in Westminster Abbey and to

be televised (12)

all over the world.

|

Forms Functions |

Indefinite Active |

Perfect Active |

Indefinite Passive |

Perfect Passive |

|

Subject |

||||

|

Part |

1 |

|||

|

Object |

||||

|

Attribute |

||||

|

Adverbial |

Exercise

19. Complete

the sentences using Active Infinitive or Passive Infinitive. §

11.1.

1.

Marie Tussaud managed (to create /to be created) her first wax

figure, of Voltaire, in 1777, when she was 16. 2. This guide book is

worth (to buy /to be bought) if you want to visit all the places of

interest. 3. The children were delighted (to have brought /to have

been brought) to the circus. 4. Sorry not (to have noticed /to have

been noticed) you. 5. I am glad (to have invited / to have been

invited) to stay with them in their country-house. 6. Diplomacy is

the art (to say /to be said) the nastiest things in the nicest way.

7. Jane ought (to have taught /to have been taught) two foreign

languages. Why wasn’t she, I wonder? 8. Nature has many secrets

(to discover /to be discovered) yet.

*Exercise

20. Paraphrase

using the appropriate form of the Infinitive.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

1

2

London The name Londinium appeared in theTachins works, but most probably, it was a Romans name that was changed into the Celtic name Llyn-din which is translated as a lake fortress.

3

Moscow One legend mentions two bibles names Mosoha, Nojas grandson, and the son of Jafeta and his wife Kva. So we can suppose that the word has come from two elements Mosk(h) and Kva. Thats why it seems attractive to think that this word may have also come from English words — «moss» and «quiet» – there are two elements as in the legend.

4

Manchester, Chichester, Dorchester, Colchester, Newcastle, Castletown. Directly or indirectly, they go back to the English words: Castle,Caster,Chester. These words have come from the Latin wordcastra(camp).

5

Winchester This name is of a complex structure and hybrid origin. On a place of that city there was a small town Kaer-Gvent(«Belgorod» or White city). The Romans have altered the name into Castrum because it was more convenient for them to pronounce it. This name is of a complex structure and hybrid origin. On a place of that city there was a small town Kaer-Gvent(«Belgorod» or White city). The Romans have altered the name into Castrum because it was more convenient for them to pronounce it. Then this town got the Canterbury from the English word Bury – a small city. In the V-th century of our era the name was changed to Winchester. Then this town got the Canterbury from the English word Bury – a small city. In the V-th century of our era the name was changed to Winchester.

6

Everton comes from the English word Ton — town Blackburn comes from the word Burn» — a stream Liverpool comes from the word Pool — a pond Oxford comes from the English word Ford – ford Edinburgh comes from the word Burgh — a small city Marlborough comes from the word Borough- a small city

7

Albion — is the poetic name of Great Britain This name has come from the Latin word albus-white. Latin word albus-white. It was given because of the cretaceous rocks at the coast of Dover. It was given because of the cretaceous rocks at the coast of Dover.

8

Bloomsbury– Блумзбери, район в центральной части Лондона назван по искаженному имени первого владельца земельного участка Блемунда (Blemund). Во многом Блумсбери напоминает знаменитый Латинский квартал Парижа. Находясь в центре Лондона – к северу от Ковент- Гардена и Сохо – район является пристанищем университетов, музеев, издательств, букинистических магазинов и библиотек. Именно здесь располагаются Британский музей – гордость Соединенного Королевства, Лондонский университет и Королевская академия драматического искусства.

9

Buckingham Palace, the main Royal residence in London, was built in 1703 and named after its first owner Duke Buckingham.

10

Royal Albert Hall of Arts and Sciences Лондонский королевский Альберт-Холл искусств и наук — учреждение культуры, концертный зал, мемориал в память принца-консорта Альберта, построенный при королеве Виктории. Расположен в Южном Кенсингтоне, одном из районов Лондона.Альбертакоролеве Виктории Южном Кенсингтоне Лондона Принц Альберт, супруг королевы Виктории, умер от тифозной лихорадки в возрасте 42 лет 14 декабря 1861 года.

11

Bodleian Library Bodleian – Бодлианская библиотека Оксфордского университета и вторая по значению в Великобритании после Британской библиотеки. Основана в 1598 Библиотека носит имя сэра Томаса Бодли ( ) известного собирателя старинных манускриптов, состоявшего на дипломатической службе королевы Елизаветы. В 1410 году библиотека перешла в полное распоряжение университета, в 1450 году библиотека переехала в новые, более обширные помещения, которые сохранились по сей день. При первых Тюдорах университет обнищал, Эдуард VI экспроприировал его книжные собрания, даже сами книжные шкафы были распроданы. В 1602 году Томас Бодли не только восстановил библиотеку, но и помог ей занять новые помещения.

12

The word «gorod» can be divided into two English words: «Go» and «Road» The word «derevnya» can be divided into the English words: Deer» (a deer, or any animal with horns) andOwn» (the property to own)Deer» (a deer, or any animal with horns) andOwn» (the property to own) The word «selo» can be composed of two English words: See (look through) and Low»See (look through) and Low»

The city of London has one of the longest and richest histories in the modern world. Despite having continuous settlement for centuries, very little is known about the word’s origin. Many historians believe that the city’s current name comes from Londinium, a name that was given to the city when the Romans established it in 43 AD. The suffix «-inium» is thought to have been common among the Romans. Other names used included Londinio, Londiniesi, and Londiniensium. There is, however, heated debate on the reason why the Romans settled for them. The subject has led to the emergence of several theories that aim at solving the puzzle. A theory from William Camden suggested that the name was derived from “Lon” formerly «Llyn,» a Welsh word that translates to «grove» and «don» which was once «dun» meaning fort. His theory relies on links to the pre-roman Celtic occupation of Wales. Some scholars have also suggested that the word London could be a combination of the Celtic words Lin, which means «pool» and “dun,” which means «Fortress.» Those supporting the Celtic theories point to city names such as Dublin which is considered Celtic for dark pool and Lincoln which was initially known as Lindon in Celtic. The name changed to Lincoln after the fortress settlement as converted to a Colonia. Richard Coates argues that the original name was derived from the pre-Celtic name Plowonida, an Indo-European compound word. He argues that the name translated to swim river or boat river (Thames River). As the name of a place, it meant «the wide river area» where swimming and the use of a boat were the only means of crossing. According to his theory, the Celts that later occupied the area were unable to pronounce the “p” hence the river became known as Lownida while the settlement was called Lownedonjon. The settlement’s name was then converter to Londinium by the Romans. A theory from Geoffrey Monmouth, suggests that the word London relates to the etymology of Britain, which is derived from Brutus. He states that London was founded as the «New Troy» by the Trojan Aeneas who was the great-grandfather of Brutus. A tribe known as the Trinovantes later inherited the legacy. He suggests that the settlement which at one point called Trinovantum was rebuilt by King Lud. Lud later got buried under the Ludgate which is where it gets its name. The city’s name then became Caer-Lud which translates to the fortress of Lud and later evolved to Kaer Llundain and eventually London. Roman control over the city ended in 410. Germanic tribes called Anglo-Saxons later occupied the area. Alfred the Great settled in the ancient Roman city and enhanced its defenses in 886. The settlement got renamed to Lundenburh which translated to fortified London. The city gradually grew around the site and, Westminster, which was the religious center. Names like Lunden, Lundin, Londoun, and Londen began to emerge after the Norman Conquest. Centuries later the name changed to London. Today London serves as the capital of England and the UK as well as the country’s leading financial hub. Celtic Theories

Pre-Celtic Theories

Mythical Theories

Post-Roman Domination and Modern London