Word is the principal and

basic unit of the language system, the largest on the morphologic and

the smallest on the syntactic plane of linguistic analysis.

According

to the number of morphemes words can be classified into monomorphic

and polymorphic. Monomorphic or root-words consist of only one

root-morpheme, e.g. small, dog, make, give, etc. All polymorphic word

fall into two subgroups: derived words and compound words –

according to the number of root-morphemes they have. Derived words

are composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational

morphemes, e.g. acceptable, outdo, disagreeable, etc. Compound words

are those which contain at least two root-morphemes, the number of

derivational morphemes being insignificant.

There can be both root- and

derivational morphemes in compounds as in pen-holder,

light-mindedness, or only root-morphemes as in lamp-shade, eye-ball,

etc.

The

term morpheme

is derived from Greek

morphe

“form ”+ -eme.

The Greek suffix –eme

has been adopted by linguistic to denote the smallest unit or the

minimum distinctive

feature.

The morpheme is the smallest

meaningful unit of form. A form in these cases a recurring discrete

unit of speech. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts

of words, not independently, although a word may consist of single

morpheme.

The

root-morpheme

is the lexical nucleus of the word; it has a very general and

abstract lexical meaning common to a set of semantically related

words constituting one word-cluster, e.g. (to) teach,

teacher, teaching.

Besides the lexical meaning root-morphemes possess all other types of

meaning proper to morphemes except the part-of-speech meaning which

is not found in roots.

Affixational

morphemes

include inflectional affixes or inflections and derivational affixes.

Inflections

carry only grammatical meaning and are thus relevant only for the

formation of word-forms. Derivational

affixes

are relevant for building various types of words. They are lexically

always dependent on the root which they modify. They possess the same

types of meaning as found in roots, most of them have the

part-of-speech meaning which makes them structurally the important

part of the word as they condition the lexico-grammatical class the

word belongs to. Due to this component of their meaning the

derivational affixes are classified into affixes building different

parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives or adverbs.

Roots

and derivational affixes are generally easily distinguished and the

difference between them is clearly felt as, e.g., in the words

helpless,

handy, blackness, Londoner, refill,

etc.: the root-morphemes help-,

hand-, black-, London-, fill-,

are understood as the lexical centers of the words, and –less,

-y, -ness, -er, re-

are

felt as morphemes dependent on these roots.

Distinction is also made of

free and bound morphemes.

Free

morphemes

coincide with word-forms of independently functioning words. It is

obvious that free morphemes can be found only among roots, so the

morpheme boy-

in the word boy

is a free morpheme; in the word undesirable

there is only one free morpheme desire-;

the word pen-holder

has two free morphemes pen-

and

hold-.

It follows that bound

morphemes

are those that do not coincide with separate word- forms,

consequently all derivational morphemes, such as –ness,

-able, -er

are bound. Root-morphemes may be both free and bound. The morphemes

theor-

in the words theory,

theoretical, or

horr-

in the words horror,

horrible, horrify; Angl- in

Anglo-Saxon; Afr-

in Afro-Asian

are all bound roots as there are no identical word-forms.

The

stem

is defined as that part of the word which remains unchanged

throughout its paradigm, thus the stem which appears in the paradigm

(to) ask

( ), asks,

asked, asking is

ask-;

the

stem of the word singer

(

), singer’s,

singers, singers’ is

singer-.

It is the stem of the word that takes the inflections which shape the

word grammatically as one or another part of speech.

Simple

stems are

semantically non-motivated and do not constitute a pattern on analogy

with which new stems may be modeled.

Simple

stems are generally monomorphic and phonetically identical with the

root morpheme.

Retain, receive, horrible, pocket, motion, etc.

should be regarded as simple, non- motivated stems.

Derived

stems – root

and derivational affix.

Compound

stems are

made up of two IC’s, both of which are themselves stems, for

example match-box,

driving-suit, pen-holder,

etc. It is built by joining of two stems, one of which is simple, the

other derived.

Bound

stem – is

not harmonious to a separate word.

To

study the motivation of the word the method of immediate ultimate

consistent is used. It is based on bannery opposition – each state

of segmentation involves 2 components words brake into.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

WORD STRUCTURE IN MODERN ENGLISH

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of morphemes. Allomorphs.

II. Structural types of words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of stems. Derivational types of words.

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of Morphemes. Allomorphs.

There are two levels of approach to the study of word- structure: the level of morphemic analysis and the level of derivational or word-formation analysis.

Word is the principal and basic unit of the language system, the largest on the morphologic and the smallest on the syntactic plane of linguistic analysis.

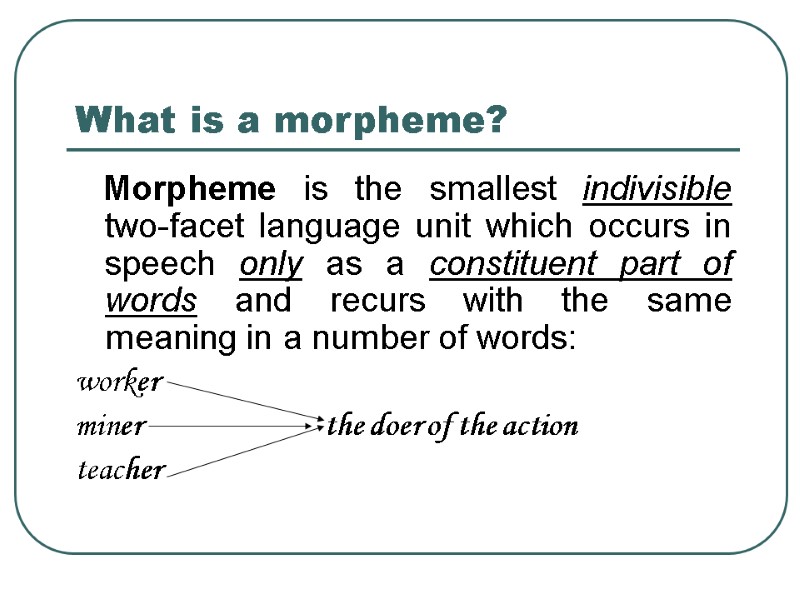

It has been universally acknowledged that a great many words have a composite nature and are made up of morphemes, the basic units on the morphemic level, which are defined as the smallest indivisible two-facet language units.

The term morpheme is derived from Greek morphe “form ”+ -eme. The Greek suffix –eme has been adopted by linguistic to denote the smallest unit or the minimum distinctive feature.

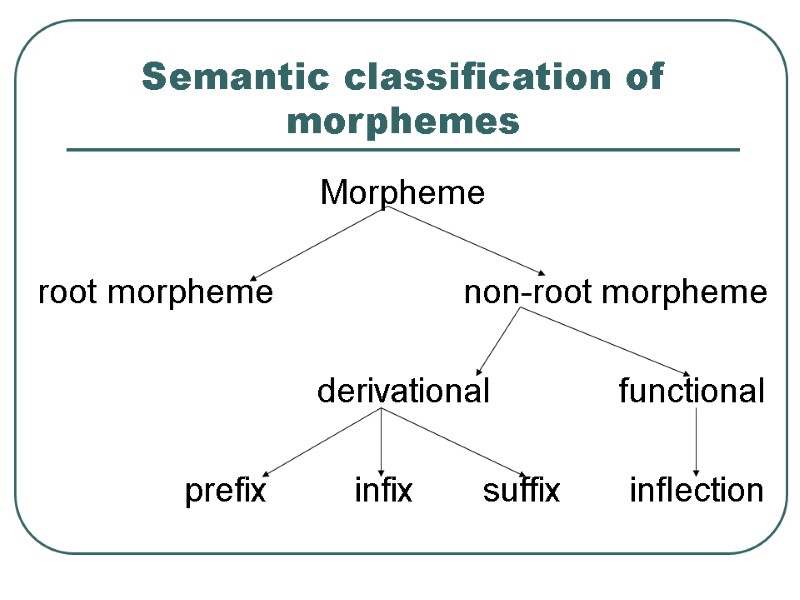

The morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of form. A form in these cases a recurring discrete unit of speech. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words, not independently, although a word may consist of single morpheme. Even a cursory examination of the morphemic structure of English words reveals that they are composed of morphemes of different types: root-morphemes and affixational morphemes. Words that consist of a root and an affix are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word building known as affixation (or derivation).

The root-morpheme is the lexical nucleus of the word; it has a very general and abstract lexical meaning common to a set of semantically related words constituting one word-cluster, e.g. (to) teach, teacher, teaching. Besides the lexical meaning root-morphemes possess all other types of meaning proper to morphemes except the part-of-speech meaning which is not found in roots.

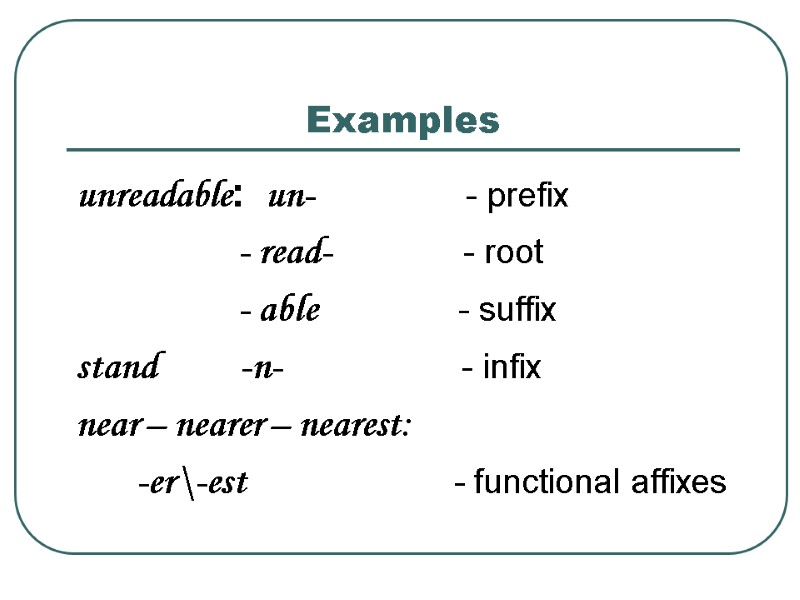

Affixational morphemes include inflectional affixes or inflections and derivational affixes. Inflections carry only grammatical meaning and are thus relevant only for the formation of word-forms. Derivational affixes are relevant for building various types of words. They are lexically always dependent on the root which they modify. They possess the same types of meaning as found in roots, but unlike root-morphemes most of them have the part-of-speech meaning which makes them structurally the important part of the word as they condition the lexico-grammatical class the word belongs to. Due to this component of their meaning the derivational affixes are classified into affixes building different parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives or adverbs.

Roots and derivational affixes are generally easily distinguished and the difference between them is clearly felt as, e.g., in the words helpless, handy, blackness, Londoner, refill, etc.: the root-morphemes help-, hand-, black-, London-, fill-, are understood as the lexical centers of the words, and –less, -y, -ness, -er, re- are felt as morphemes dependent on these roots.

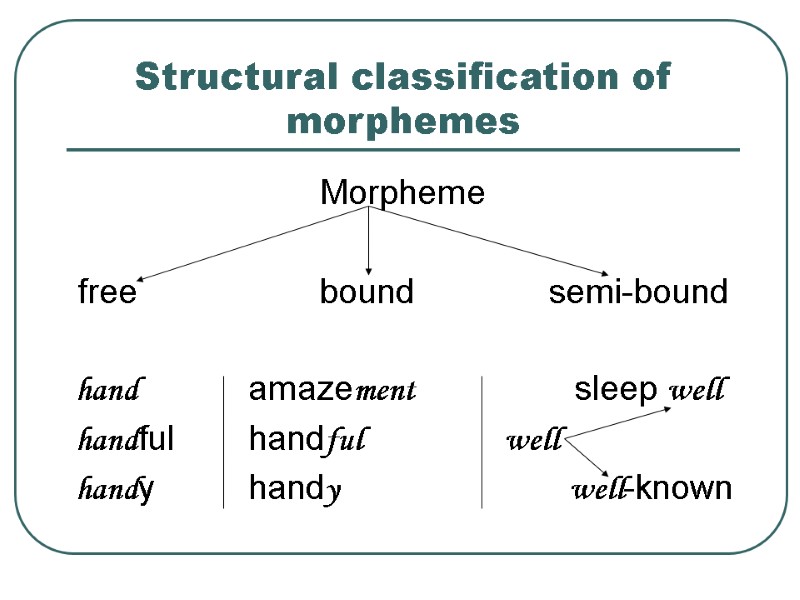

Distinction is also made of free and bound morphemes.

Free morphemes coincide with word-forms of independently functioning words. It is obvious that free morphemes can be found only among roots, so the morpheme boy- in the word boy is a free morpheme; in the word undesirable there is only one free morpheme desire-; the word pen-holder has two free morphemes pen- and hold-. It follows that bound morphemes are those that do not coincide with separate word- forms, consequently all derivational morphemes, such as –ness, -able, -er are bound. Root-morphemes may be both free and bound. The morphemes theor- in the words theory, theoretical, or horr- in the words horror, horrible, horrify; Angl- in Anglo-Saxon; Afr- in Afro-Asian are all bound roots as there are no identical word-forms.

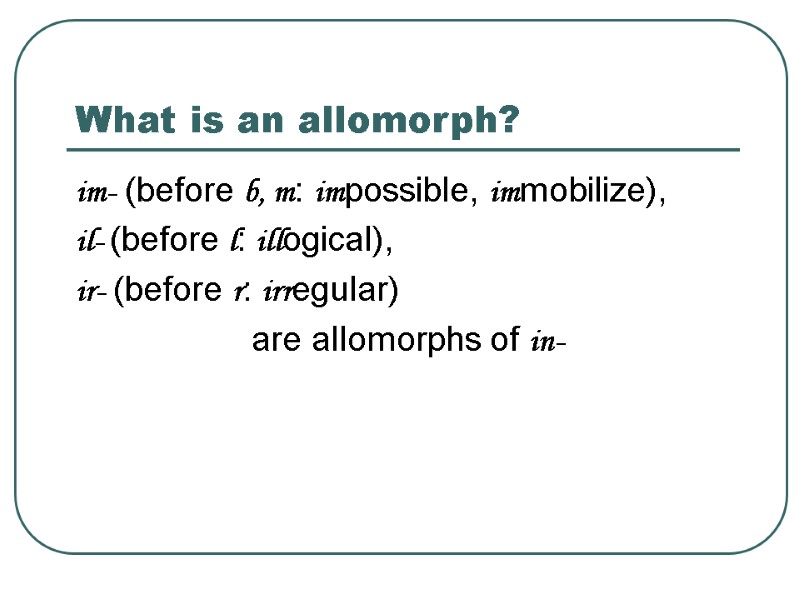

It should also be noted that morphemes may have different phonemic shapes. In the word-cluster please , pleasing , pleasure , pleasant the phonemic shapes of the word stand in complementary distribution or in alternation with each other. All the representations of the given morpheme, that manifest alternation are called allomorphs/or morphemic variants/ of that morpheme.

The combining form allo- from Greek allos “other” is used in linguistic terminology to denote elements of a group whose members together consistute a structural unit of the language (allophones, allomorphs). Thus, for example, -ion/ -tion/ -sion/ -ation are the positional variants of the same suffix, they do not differ in meaning or function but show a slight difference in sound form depending on the final phoneme of the preceding stem. They are considered as variants of one and the same morpheme and called its allomorphs.

Allomorph is defined as a positional variant of a morpheme occurring in a specific environment and so characterized by complementary description.

Complementary distribution is said to take place, when two linguistic variants cannot appear in the same environment.

Different morphemes are characterized by contrastive distribution, i.e. if they occur in the same environment they signal different meanings. The suffixes –able and –ed, for instance, are different morphemes, not allomorphs, because adjectives in –able mean “ capable of beings”.

Allomorphs will also occur among prefixes. Their form then depends on the initials of the stem with which they will assimilate.

Two or more sound forms of a stem existing under conditions of complementary distribution may also be regarded as allomorphs, as, for instance, in long a: length n.

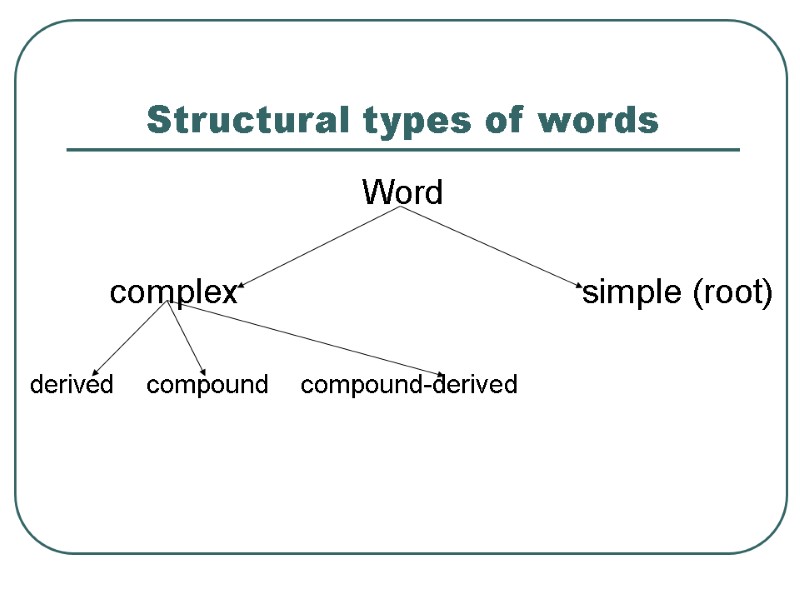

II. Structural types of words.

The morphological analysis of word- structure on the morphemic level aims at splitting the word into its constituent morphemes – the basic units at this level of analysis – and at determining their number and types. The four types (root words, derived words, compound, shortenings) represent the main structural types of Modern English words, and conversion, derivation and composition the most productive ways of word building.

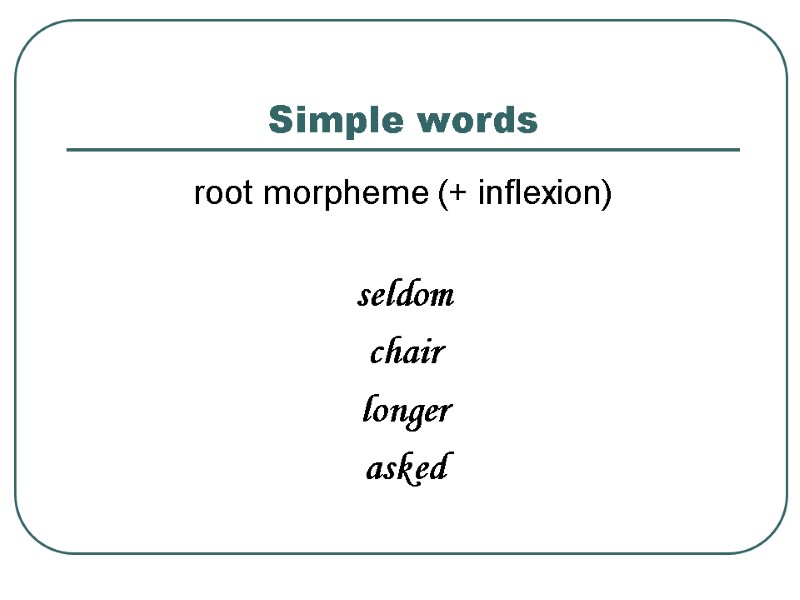

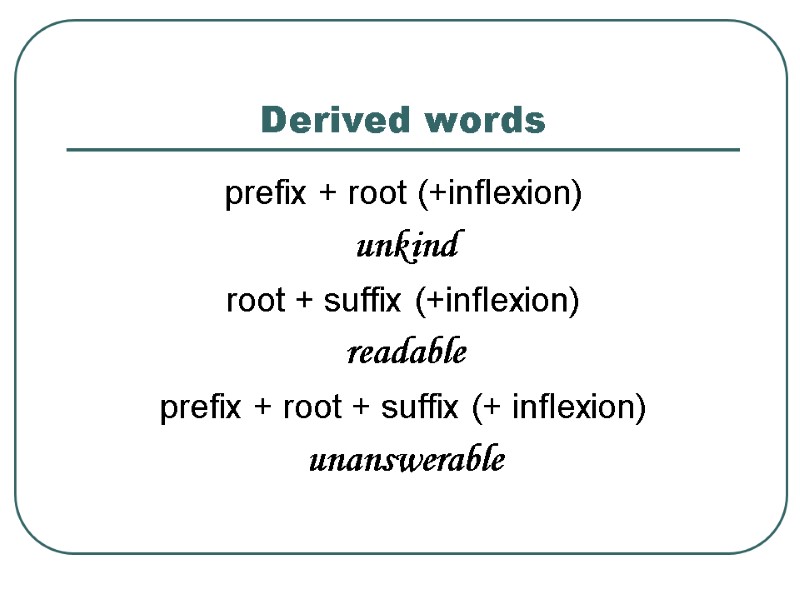

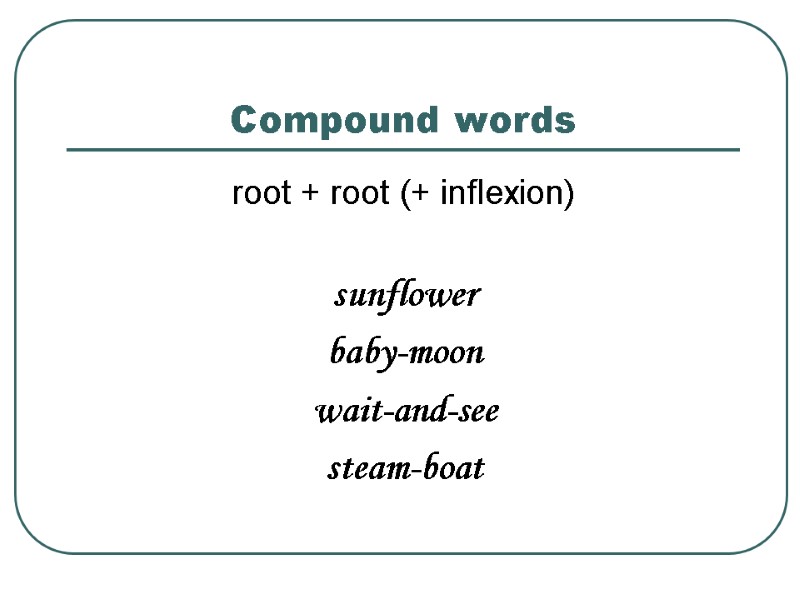

According to the number of morphemes words can be classified into monomorphic and polymorphic. Monomorphic or root-words consist of only one root-morpheme, e.g. small, dog, make, give, etc. All polymorphic word fall into two subgroups: derived words and compound words – according to the number of root-morphemes they have. Derived words are composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational morphemes, e.g. acceptable, outdo, disagreeable, etc. Compound words are those which contain at least two root-morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant. There can be both root- and derivational morphemes in compounds as in pen-holder, light-mindedness, or only root-morphemes as in lamp-shade, eye-ball, etc.

These structural types are not of equal importance. The clue to the correct understanding of their comparative value lies in a careful consideration of: 1)the importance of each type in the existing wordstock, and 2) their frequency value in actual speech. Frequency is by far the most important factor. According to the available word counts made in different parts of speech, we find that derived words numerically constitute the largest class of words in the existing wordstock; derived nouns comprise approximately 67% of the total number, adjectives about 86%, whereas compound nouns make about 15% and adjectives about 4%. Root words come to 18% in nouns, i.e. a trifle more than the number of compound words; adjectives root words come to approximately 12%.

But we cannot fail to perceive that root-words occupy a predominant place. In English, according to the recent frequency counts, about 60% of the total number of nouns and 62% of the total number of adjectives in current use are root-words. Of the total number of adjectives and nouns, derived words comprise about 38% and 37% respectively while compound words comprise an insignificant 2% in nouns and 0.2% in adjectives. Thus it is the root-words that constitute the foundation and the backbone of the vocabulary and that are of paramount importance in speech. It should also be mentioned that root words are characterized by a high degree of collocability and a complex variety of meanings in contrast with words of other structural types whose semantic structures are much poorer. Root- words also serve as parent forms for all types of derived and compound words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

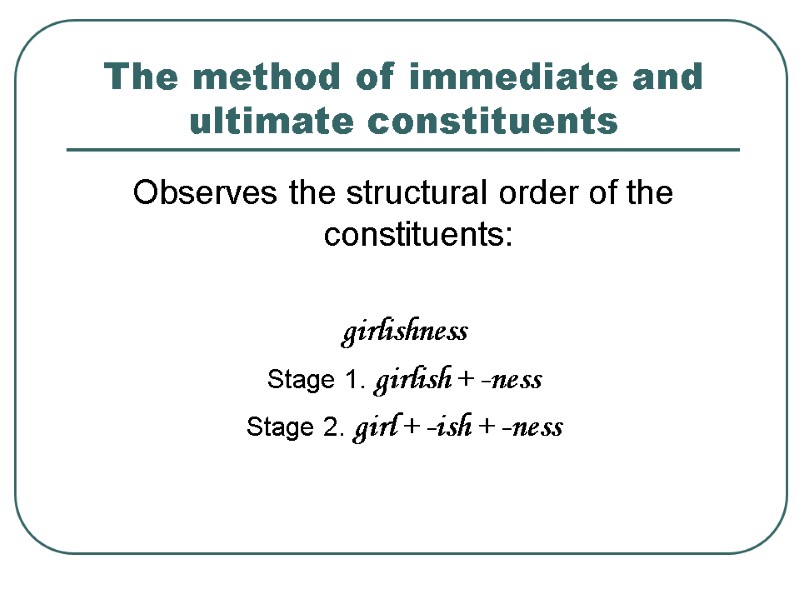

In most cases the morphemic structure of words is transparent enough and individual morphemes clearly stand out within the word. The segmentation of words is generally carried out according to the method of Immediate and Ultimate Constituents. This method is based on the binary principle, i.e. each stage of the procedure involves two components the word immediately breaks into. At each stage these two components are referred to as the Immediate Constituents. Each Immediate Constituent at the next stage of analysis is in turn broken into smaller meaningful elements. The analysis is completed when we arrive at constituents incapable of further division, i.e. morphemes. These are referred to Ultimate Constituents.

A synchronic morphological analysis is most effectively accomplished by the procedure known as the analysis into Immediate Constituents. ICs are the two meaningful parts forming a large linguistic unity.

The method is based on the fact that a word characterized by morphological divisibility is involved in certain structural correlations. To sum up: as we break the word we obtain at any level only ICs one of which is the stem of the given word. All the time the analysis is based on the patterns characteristic of the English vocabulary. As a pattern showing the interdependence of all the constituents segregated at various stages, we obtain the following formula:

un+ { [ ( gent- + -le ) + -man ] + -ly}

Breaking a word into its Immediate Constituents we observe in each cut the structural order of the constituents.

A diagram presenting the four cuts described looks as follows:

1. un- / gentlemanly

2. un- / gentleman / — ly

3. un- / gentle / — man / — ly

4. un- / gentl / — e / — man / — ly

A similar analysis on the word-formation level showing not only the morphemic constituents of the word but also the structural pattern on which it is built.

The analysis of word-structure at the morphemic level must proceed to the stage of Ultimate Constituents. For example, the noun friendliness is first segmented into the ICs: [frendlı-] recurring in the adjectives friendly-looking and friendly and [-nıs] found in a countless number of nouns, such as unhappiness, blackness, sameness, etc. the IC [-nıs] is at the same time an UC of the word, as it cannot be broken into any smaller elements possessing both sound-form and meaning. Any further division of –ness would give individual speech-sounds which denote nothing by themselves. The IC [frendlı-] is next broken into the ICs [-lı] and [frend-] which are both UCs of the word.

Morphemic analysis under the method of Ultimate Constituents may be carried out on the basis of two principles: the so-called root-principle and affix principle.

According to the affix principle the splitting of the word into its constituent morphemes is based on the identification of the affix within a set of words, e.g. the identification of the suffix –er leads to the segmentation of words singer, teacher, swimmer into the derivational morpheme – er and the roots teach- , sing-, drive-.

According to the root-principle, the segmentation of the word is based on the identification of the root-morpheme in a word-cluster, for example the identification of the root-morpheme agree- in the words agreeable, agreement, disagree.

As a rule, the application of these principles is sufficient for the morphemic segmentation of words.

However, the morphemic structure of words in a number of cases defies such analysis, as it is not always so transparent and simple as in the cases mentioned above. Sometimes not only the segmentation of words into morphemes, but the recognition of certain sound-clusters as morphemes become doubtful which naturally affects the classification of words. In words like retain, detain, contain or receive, deceive, conceive, perceive the sound-clusters [rı-], [dı-] seem to be singled quite easily, on the other hand, they undoubtedly have nothing in common with the phonetically identical prefixes re-, de- as found in words re-write, re-organize, de-organize, de-code. Moreover, neither the sound-cluster [rı-] or [dı-], nor the [-teın] or [-sı:v] possess any lexical or functional meaning of their own. Yet, these sound-clusters are felt as having a certain meaning because [rı-] distinguishes retain from detain and [-teın] distinguishes retain from receive.

It follows that all these sound-clusters have a differential and a certain distributional meaning as their order arrangement point to the affixal status of re-, de-, con-, per- and makes one understand —tain and –ceive as roots. The differential and distributional meanings seem to give sufficient ground to recognize these sound-clusters as morphemes, but as they lack lexical meaning of their own, they are set apart from all other types of morphemes and are known in linguistic literature as pseudo- morphemes. Pseudo- morphemes of the same kind are also encountered in words like rusty-fusty.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of Stems. Derivational types of word.

The morphemic analysis of words only defines the constituent morphemes, determining their types and their meaning but does not reveal the hierarchy of the morphemes comprising the word. Words are no mere sum totals of morpheme, the latter reveal a definite, sometimes very complex interrelation. Morphemes are arranged according to certain rules, the arrangement differing in various types of words and particular groups within the same types. The pattern of morpheme arrangement underlies the classification of words into different types and enables one to understand how new words appear in the language. These relations within the word and the interrelations between different types and classes of words are known as derivative or word- formation relations.

The analysis of derivative relations aims at establishing a correlation between different types and the structural patterns words are built on. The basic unit at the derivational level is the stem.

The stem is defined as that part of the word which remains unchanged throughout its paradigm, thus the stem which appears in the paradigm (to) ask ( ), asks, asked, asking is ask-; thestem of the word singer ( ), singer’s, singers, singers’ is singer-. It is the stem of the word that takes the inflections which shape the word grammatically as one or another part of speech.

The structure of stems should be described in terms of IC’s analysis, which at this level aims at establishing the patterns of typical derivative relations within the stem and the derivative correlation between stems of different types.

There are three types of stems: simple, derived and compound.

Simple stems are semantically non-motivated and do not constitute a pattern on analogy with which new stems may be modeled. Simple stems are generally monomorphic and phonetically identical with the root morpheme. The derivational structure of stems does not always coincide with the result of morphemic analysis. Comparison proves that not all morphemes relevant at the morphemic level are relevant at the derivational level of analysis. It follows that bound morphemes and all types of pseudo- morphemes are irrelevant to the derivational structure of stems as they do not meet requirements of double opposition and derivative interrelations. So the stem of such words as retain, receive, horrible, pocket, motion, etc. should be regarded as simple, non- motivated stems.

Derived stems are built on stems of various structures though which they are motivated, i.e. derived stems are understood on the basis of the derivative relations between their IC’s and the correlated stems. The derived stems are mostly polymorphic in which case the segmentation results only in one IC that is itself a stem, the other IC being necessarily a derivational affix.

Derived stems are not necessarily polymorphic.

Compound stems are made up of two IC’s, both of which are themselves stems, for example match-box, driving-suit, pen-holder, etc. It is built by joining of two stems, one of which is simple, the other derived.

In more complex cases the result of the analysis at the two levels sometimes seems even to contracted one another.

The derivational types of words are classified according to the structure of their stems into simple, derived and compound words.

Derived words are those composed of one root- morpheme and one or more derivational morpheme.

Compound words contain at least two root- morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant.

Derivational compound is a word formed by a simultaneous process of composition and derivational.

Compound words proper are formed by joining together stems of word already available in the language.

MODERN ENGLISH LEXICOLOGY Morphological Structure of the English Word

Problems for discussion Methods of word-structure analysis Distinction between “morpheme”, “morph”, “allomorph” Structural classification of morphemes Semantic classification of morphemes Structural types of words

Which methods are used to observe structural composition of words? Morphemic analysis Morphological analysis Method of Immediate and Ultimate Constituents

Morphemic analysis Segments a word into morphemes to determine their number and types: girlishness one root morpheme (-girl-) + two suffixes (-ish; -ness)

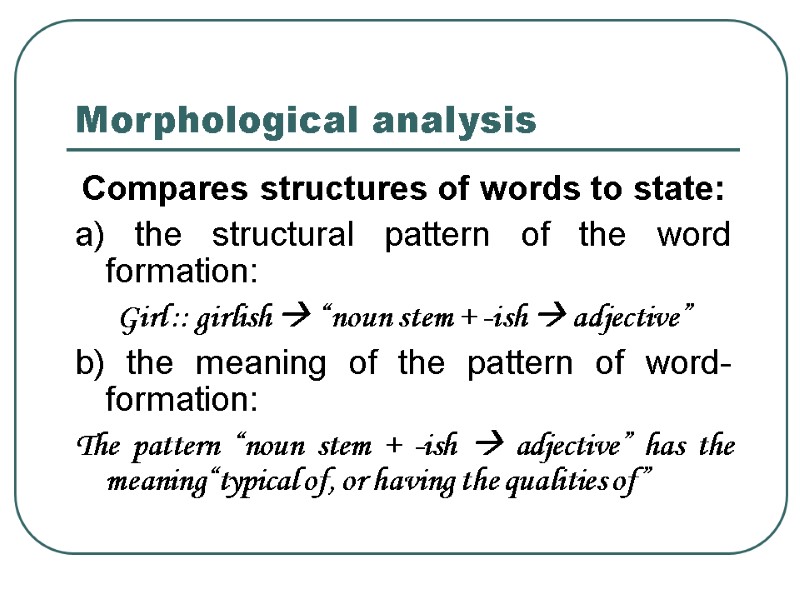

Morphological analysis Compares structures of words to state: a) the structural pattern of the word formation: Girl :: girlish “noun stem + -ish adjective” b) the meaning of the pattern of word-formation: The pattern “noun stem + -ish adjective” has the meaning“typical of, or having the qualities of”

The method of immediate and ultimate constituents Observes the structural order of the constituents: girlishness Stage 1. girlish + -ness Stage 2. girl + -ish + -ness

What is a morpheme? Morpheme is the smallest indivisible two-facet language unit which occurs in speech only as a constituent part of words and recurs with the same meaning in a number of words: worker miner the doer of the action teacher

What is a morph? A morph is a single realization of a morpheme.

What is an allomorph? im- (before b, m: impossible, immobilize), il- (before l: illogical), ir- (before r: irregular) are allomorphs of in-

Structural classification of morphemes Morpheme free bound semi-bound hand amazement sleep well handful handful well handy handy well-known

Semantic classification of morphemes Morpheme root morpheme non-root morpheme derivational functional prefix infix suffix inflection

Examples unreadable: un- — prefix — read- — root — able — suffix stand -n- — infix near – nearer – nearest: -er-est — functional affixes

Structural types of words Word complex simple (root) derived compound compound-derived

Simple words root morpheme (+ inflexion) seldom chair longer asked

Derived words prefix + root (+inflexion) unkind root + suffix (+inflexion) readable prefix + root + suffix (+ inflexion) unanswerable

Compound words root + root (+ inflexion) sunflower baby-moon wait-and-see steam-boat

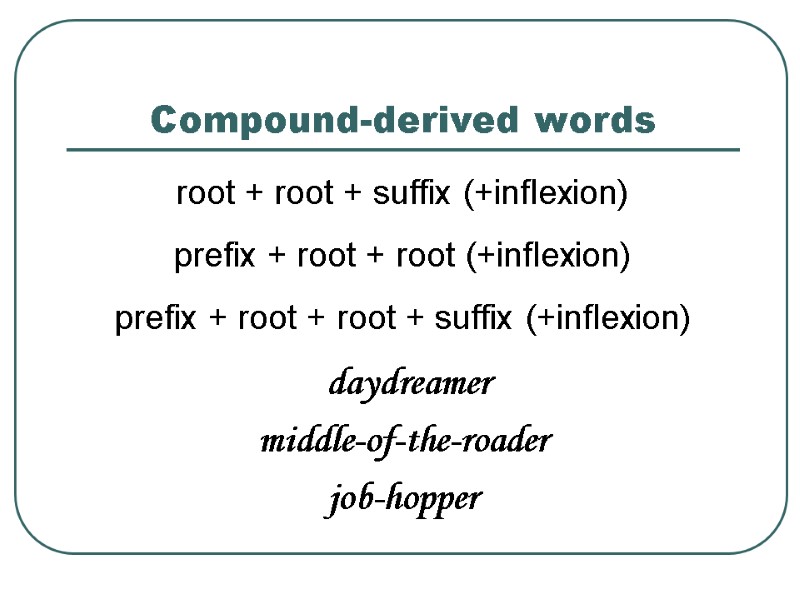

Compound-derived words root + root + suffix (+inflexion) prefix + root + root (+inflexion) prefix + root + root + suffix (+inflexion) daydreamer middle-of-the-roader job-hopper

Identifying a Word. Morphological Structure of the Word Lecture 5 5.1.Problems of the Definition of the Word 5.2. Lexical and Grammatical Words 5.3. Morphological Structure of the Word 5.4. Types of Morphemic Segmentability The Problems of the Definition A word has many different aspects: 1) phonological, as it has a sound form; 2) morphological, as it is a certain arrangement of morphemes; 3) syntactic, as it may occur in different word forms and signal different meanings. The Problems of the Definition A word is defined as: minimum free form (L. Bloomfield) association of a given meaning with a given group of sounds susceptible of a given grammatical employment (A. Meillet) The Problems of the Definition A word is an autonomous unit of the language in which a particular meaning is associated with a particular sound complex capable of a particular grammatical employment and able to form a sentence by itself. The Problems of the Definition Orthographically words may be spelt differently: teapot, tea-pot, tea pot. Words are written separately, but not all words fit this category, e.g. will not – two words; cannot – one word. There may be found different forms but different forms are not necessarily regarded as different words, e.g. teach, teaches, taught, teaching; nice, nicer, nicest – are not separate words. The Problems of the Definition Some words can have the same forms but completely different and unrelated meanings, e.g. fair. The existence of idioms and phrasal verbs seems to upset attempts to define words in any formal way, e.g. to kick the bucket – “to die”, to put off – “to postpone”. The Problems of the Definition A lexeme is the abstract unit which underlies some of the variants we have observed in connection with 'words'. Thus, teach is the lexeme which underlies some of the variants teach, teaches, taught, teaching which are the word-forms. The Problems of the Definition The term lexeme is also connected with more than one word-form expressed by such lexical items as: Multi-word verbs, e.g., to catch up with; Phrasal verbs, e.g., to clear up, to switch off; Idioms, e.g., kick the bucket. Lexical and Grammatical Words Lexical words are full words or content words. They include nouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs and belong to the open classes of words. They carry a higher information content and are syntactically structured by the grammatical words. LW form an open class of words because they are subject to diachronic change, changes in form and meaning over a period of time. Lexical and Grammatical Words Nouns A noun is a naming word. It gives the name to a person, place, thing, etc. Most nouns possess the category of number and have a plural form (-s/ -es). Some words make their plural forms in a different way. Others never change their singular forms to make their plurals. Some nouns never occur without the plural marker. Lexical and Grammatical Words Adjectives Adjectives denote a property or quality of an object. All adjectives fall into two groups: gradable and non-gradable. Gradable adjectives take grammatical forms and represent degrees of comparison: positive, comparative, superlative. Adjectives in English may appear either before a noun or after a verb, e.g. juicy apple, get wet, be happy. Not all adjectives appear in both positions. Lexical and Grammatical Words Verbs There are two classes of verbs – lexical and auxiliary verbs. Lexical verbs denote actions or states. Each verb has five associated grammatical words, e.g., ask – asks – asked – asking – asked; go – goes – went – going – gone. Verbs like ask are regular, they form the majority of verbs in English. Irregular verbs like go have different forms. Lexical and Grammatical Words Adverbs Two classes of adverbs – degree and general. Degree adverbs are a small group of words like quite, far, very, more, and most. They always appear with either an adjective or a general adverb, e.g. She drives very well. His story is quite interesting. General adverbs form a large class and may appear without a degree adverb, e.g. He cooks well. Adverbs denote degree, manner, place, time. Adverbs have no inflected forms, they take comparisons like adjectives. Lexical and Grammatical Words Grammatical words comprise a small class of words that includes pronouns, auxiliary verbs, determiners, prepositions, conjunctions. They are also known as functional words, or empty words. Grammatical words constitute a closed class, i.e. they do not accept new members. Lexical and Grammatical Words Pronouns are words that take the place of nouns, noun phrases. Different types: personal (I, we, she), demonstrative (this, those), possessive (mine, yours), interrogative (whom, whose, which), etc. Auxiliary verbs such as have, do, did, will determine the mood, tense, or aspect of another verb in a verb phrase. Conjunctions serve to connect words, phrases, clauses, or sentences, e.g. and, but, for, or, nor, yet, so. Lexical and Grammatical Words Determiners introduce nouns; they are articles (a, an, the), quantifiers (some, much). Prepositions are words that show the relationship between a noun or pronoun and other words in a sentence. They indicate locations in time or space (at, in), agency (by), comparison (like, as . . . as), direction (to, toward, through), place (at, by, on), possession (of), purpose (for), source (from, out of), and time (at, before, on), etc. Morphological Structure Words consist of morphemes. A morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of speech, which cannot be split up into smaller segments. A morpheme is not autonomous. Morphemes occur in speech as constituent parts of words, not independently. Morphological Structure A word may consist of a single morpheme or contain several, e.g. shelf (one morpheme), indisputable (3 morphemes) – in-disput-able. The morpheme in can be found in words insignificant, inexpensive; the morpheme able – in words excusable, reliable; the morpheme dispute – in such words as disputing, disputes. Morphological Structure Some morphemes have only one phonological form, while others may have a number of variants which are known as allomorph. Pronounce: please, pleasing, pleasure, pleasant. The representations of the given morpheme are called allomorphs or morphemic variants. Morphological Structure An allomorph is a positional variant of a morpheme occurring in a specific environment and characterized by complementary distribution. Cows, cats, pigs, horses, sheep, oxen, mice Allomorphs occur among prefixes. The morpheme in may have the following phonological forms: im occurs before bilabials – impossible; ir occurs before r – irregular; il occurs before 1 – illegal; in occurs before other consonants and vowels – inability, indirect. Morphological Structure Semantically morphemes fall into root- morphemes and non-root morphemes. The root-morphemes are the lexical centers of the words, as the basic constituent part of a word without which the word is inconceivable. Morphological Structure Words hairless, lofty, darkness, refill – the root morphemes are hair, loft, dark, fill The root-morpheme is the lexical nucleus of a word; it has an individual lexical meaning shared by no other morpheme of the language. The root-morpheme is the morpheme common to a set of words making up a wordcluster, e.g. dance in to dance, dancer, dancing. Morphological Structure Non-root morphemes include inflectional morphemes (inflections) and derivational morphemes (affixes). Morphological Structure Inflections carry only grammatical meaning, they build different forms of one and the same word, e.g. cheap, cheaper, cheapest. Affixes supply the stem with components of lexical and lexicogrammatical meaning. They are classified into prefixes and suffixes, e.g. chain – unchain, broad - broaden. Morphological Structure A suffix is a derivational morpheme following the stem and forming a new derivative in a different part of speech or a different word class, e.g., -en, -y, less in hearten, hearty, heartless. A prefix is a derivational morpheme standing before the root and modifying meaning, e.g., to hearten - to dishearten. Morphological Structure Structurally morphemes fall into free morphemes, bound morphemes, semi-free (semi-bound morphemes). Morphological Structure A free morpheme is defined as one that can occur by itself as a whole word, e.g. cloudy – cloud, excusable – excuse. A great number of root morphemes are free morphemes, e.g. child in the words childhood, children, childish is naturally qualified as a free morpheme because it coincides with one of the forms of the noun child. Morphological Structure A bound morpheme is attached to another and is a constituent part of a word. Bound morphemes are of two types: inflectional morphemes and derivational ones. Inflectional morphemes: watch – watches, look – looked, etc. Derivational morphemes are affixes, e.g. ness, -ship, -ize, dis-, de- in the words like happiness, relationship, to displease, to demoralize. Morphological Structure Semi-free or semi-bound morphemes can function in a morphemic sequence both as an affix and as a free morpheme, e.g. half-ready, seaman, womanlike. Morphological Structure According to the number of morphemes words fall into monomorphic and polymorphic. Monomorphic or root-words consist of only one root-morpheme, e.g. long, car, make, drive, etc. Morphological Structure All polymorphic words according to the number of root-morphemes are classified into two subgroups: monoradical or root words and polyradical words, i.e. words which consist of two or more roots. Morphemic Segmentability As far as the complexity of the morphemic structure of the word is concerned all English words fall into two large classes: segmentable words, those allowing of further morphemic segmentation, e.g., quickly, fearless, agreement; non-segmentable words, e.g., house, girl, cat, woman. Morphemic Segmentability The main aim of the morphemic analysis is to split a word into its constituent morphemes, determine their number and type. It's called the method of immediate and ultimate constituents. Morphemic Segmentability DISAGREEMENT DISAGREE DIS AGREE MENT Morphemic Segmentability There are three types of morphemic segmentability: complete, conditional and defective. Morphemic Segmentability Complete segmentability: the individual morphemes are clearly singled out within the word and can easily be isolated. The constituent morphemes are met in other words with the same meaning, e.g. speechless – two morphemes: speech and less. Speech → speech, speeches, less → nameless, useless. Morphemic Segmentability Conditional segmentability: the segmentation into the constituent morphemes is doubtful for some semantic reasons, e.g. retain, contain, detain. The words can be split into the following re–tain, con–tain, de–tain. The constituent part -tain unites these three verbs, but we cannot trace the common meaning in each verb, consequently we cannot regard -tain as a morpheme. Morphemic Segmentability Similarly we may find re-, con-, de- in other verbs (recall, remind, consist, confuse, delay, defeat), but each group of words does not share a common meaning. Such morphemes are called pseudo-morphemes or quasimorphemes. Morphemic Segmentability Defective segmentability is the property of words whose constituent morphemes are seldom or never met in other words. A unique morpheme is isolated and understood as meaningful because the constituent morphemes display a more or less clear denotational meaning. cranberry → two morphemes: cran and berry. The morpheme -berry occurs in strawberry, blackberry, etc. Cran does not recur in any other English word, thus, this morpheme is unique. Thank you for your attention. Don’t forget to get ready for the seminar.