Subjects>Jobs & Education>Education

Wiki User

∙ 10y ago

Best Answer

Copy

I don’t no and I would like to no please tell me.

Wiki User

∙ 10y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What is the modern word for hast?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

By

Last updated:

March 26, 2022

The English language is very much alive and growing, with more new words added to the dictionary every year. Today, we’re going to learn 25 brand-new English words that native speakers use all the time.

But before we get to that list, you may be wondering where new English words come from, and some quick tips to master them in the shortest time possible.

Contents

- Where Do New Words Come From?

- The Quickest Ways to Master New English Vocabulary

- Trendy English Words Worth Learning in 2022

-

- 1. To Chillax

- 2. Whatevs

- 3. Freegan

- 4. Hellacious

- 5. Awesomesauce

- 6. Cringe

- 7. Stan / To Stan

- 8. Sober-curious

- 9. B-day

- 10. Beardo

- 11. Sriracha

- 12. Ghost

- 13. EVOO

- 14. Manspread

- 15. Facepalm

- 16. Froyo

- 17. Hangry

- 18. Photobomb

- 19. Binge Watch

- 20. Fitspiration

- 21. Mansplain

- 22. Glamping

- 23. Side-eye

- 24. Fast Fashion

- 25. Staycation

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Where Do New Words Come From?

Every year, hundreds of new words are added to the English dictionary. Of course, not all new words make it into the dictionary. The ones that do are those that have been used frequently in a wide range of contexts and are found to be useful to English communication.

New English words may come from foreign words that have been adapted into the English language over time. For instance, if you love spicy food, you’ll be pleased to know that the word sriracha (a spicy chili and garlic sauce invented in Thailand) has been added to the dictionary.

Some new words are actually old words that have been given new or additional meanings. For example, ghost is no longer a word you only use around Halloween time, to refer to a spirit. It now has an additional meaning, which we’ll show you in our list below.

New slang words aren’t just old words used in new ways. New words may also be formed from the blending or shortening of certain words or phrases. For instance, a key ingredient in Italian cuisine is extra virgin olive oil—it’s a real tongue twister, but thankfully, it’s now been shortened to simply EVOO as you’ll see soon.

Or you can learn more about this right now, if you want a learn 12 of the twenty-five trendy words below via video.

The Quickest Ways to Master New English Vocabulary

- Make your own personal dictionary: One of the most effective ways to master English vocabulary is to create your own dictionary of words that are most important or difficult for you. Write down a list of new words you wish to learn and make notes about their meanings and usages.

Mastering new vocabulary takes time and practice, so be sure to keep your personal dictionary with you to reference and refresh your memory whenever you need to. This will help prevent you from forgetting words easily.

- Watch authentic English-language media. Watching, reading, or listening to authentic English-language content is a fantastic way to learn the words and phrases native speakers use every day in context.

Thankfully, there are many platforms with subtitled videos for you to choose from. FluentU, for example, is a language learning app and website based on authentic English-language videos. Each video has interactive subtitles that you can click on for example sentences, pronunciation, and more, which could help you expand your vocabulary and learn words in context.

- Talk to people: Another way to master new vocabulary is to use the words in real English conversations. The more you repeat the word, the more fluent you’ll become at using it. By talking to native English speakers, you’ll also pick up new vocabulary from them. Now that’s a bonus!

Here are some great tips to find English speaking partners no matter where you currently live.

Trendy English Words Worth Learning in 2022

1. To Chillax

If you blend (mix) the words chill (relaxed) and relax, you get the verb to chillax.

This word has become more and more common on the internet over the past couple of years, and it simply means to relax, to become calm or to take it easy.

Although people use it almost with the same meaning as to relax, I find chillax has more of a sarcastic meaning, as in “wow, calm down, this isn’t so serious, you’re overreacting.”

No matter the meaning it can have for different people, remember that this word is used in slang, so don’t go telling your boss or your teacher to chillax!

Hey man, just chillax! It’s just a horror movie, not the end of the world!

2. Whatevs

Whatevs is an informal word that means whatever.

I’ve normally seen it used in sentences in which the speaker wants to express irony and show they don’t care about what’s happening or being said.

You’ll normally see whatevs as a standalone interjection or at the end of sentences:

“I don’t love you anymore.”

“Whatevs… Bye!”

She didn’t give me the lipstick back, but whatevs.

3. Freegan

Freegans and freeganism have been popular for years, but it’s only recently that we’ve gotten a word to describe who and what they are.

Simply put, a freegan is a person who tries to buy a little as possible, uses discarded things and/or (especially) food, and recycles everything they can. They’re environmentally conscious and friendly, and they do their best to reduce waste.

Although this is a positive thing for the Earth, some people take it to the extreme. It’s because of this that the words freegan and freeganism are normally surrounded by negative connotations (associations, suggestions).

He became a freegan five years ago and hasn’t bought food ever since.

4. Hellacious

This word is a mix of the word hell and the suffix -cious, which is quite common in English (delicious, conscious, audacious, tenacious, etc.).

Hellacious can have different meanings, but it is normally used as an adjective meaning astonishing, remarkable or very difficult.

This word is obviously slang, so use it only in the appropriate contexts!

He got a hellacious amount of hate from his last post.

They got a hellacious time trying to leave the country in one piece.

5. Awesomesauce

Put together the words awesome and sauce and you will get awesomesauce, which basically has the same meaning as awesome with a pinch of even more awesomeness.

This slang word can be used in any informal situation, and it works like a normal adjective:

I’m reading an awesomesauce book about the influence of slang words in the English language. How am I doing?

6. Cringe

Have you ever heard someone say something so embarrassing you even felt sorry for them?

Have you been present in a situation where someone was acting so awkwardly (strangely, embarrassingly, gracelessly) that you wished you were not there?

If so, then you were cringing big time!

To cringe means to feel embarrassed and ashamed about what someone is doing or saying. You can even cringe at yourself, but let’s be honest here, we normally cringe at other people.

His mum was dancing with his best friend and he couldn’t help but cringe.

I cringe every time I read her lovey-dovey comments.

In more recent times, you can even use cringe instead of the adjective cringy to describe something that makes you cringe:

That outfit is so cringe.

7. Stan / To Stan

Stan can be used as a noun to describe a person and as a verb to describe an action.

A stan is a person who idolizes, loves to the point of obsession or is an overzealous (very devoted and loyal) celebrity fan.

To stan means to idolize, love obsessively or be an overzealous fan of a celebrity.

The slang word comes from the 2000 Eminem song titled “Stan,” which is about an obsessive fan whose love for a celebrity… well, let’s just say that it doesn’t end well.

Recently, this word has become much more common, and it can now be used in any context or situation where you want to say you love someone or something.

OMG (Oh My God)! I stan those clothes, Jenni!

I stan Katy. She’s my role model.

Sometimes, you might even see someone (usually online) say “we stan,” showing collective support (that is, support from everyone in the community).

8. Sober-curious

This word is wonderful in a terrible sort of way. You could even say it makes you cringe.

Sober-curious can be used to describe a person who questions their drinking habits or wants to try to change them because of health or mental reasons.

I’ve only seen it used in very specific contexts and always related to drinking habits and alcoholism, so hopefully, you won’t have to use it very often.

He’s sober-curious and wants to try to not drink for one week.

9. B-day

B-day is just an informal shortened version of the word birthday. You can see it written on social media quite a lot, especially when wishing someone a happy birthday:

Happy b-day, John! Hope you have an awesome one!

The way to pronounce this word is BEE-dey.

10. Beardo

A beardo is a person with a beard. Simple.

However, as often happens with other words like weirdo (an odd or eccentric person) it can have a pejorative (negative and unkind) meaning, especially if you put those two words together: weirdo beardo.

A weirdo beardo is a person with a beard who doesn’t have the best hygiene habits and is socially odd and awkward:

That weirdo beardo really needs a haircut!

11. Sriracha

If you love spicy food, you’ve probably heard of sriracha. It’s a Thai-inspired sauce made from a blend of hot chili peppers, garlic and spices that’s commonly used in cooking or as a dipping sauce.

Sriracha really adds a kick to your hamburger, but be sure you have a glass of water nearby!

12. Ghost

The meaning of the word ghost (when used as a noun) that most of us are familiar with is the spirit of a dead person, like the kind we often see appearing and disappearing in movies. Now the word ghost has a new, informal meaning that has to do with disappearing.

Used as a verb, to ghost means to suddenly cut off contact completely with someone (usually a romantic partner) by not answering their phone calls and text messages.

You’ll often hear it used in the past tense (ghosted)… since you don’t know you’ve been ghosted until it’s too late!

I haven’t heard from her in more than a week. She totally ghosted me.

13. EVOO

Try saying “extra virgin olive oil” a few times. This is a type of high-quality oil that makes Italian food so very delicious, and it’s quite a mouthful to say, isn’t it?

But no worries, now we can shorten it to EVOO with the first letters of those words. Ah there, isn’t that easier to say?

Remember to grab a bottle of EVOO on your way home. I’m making pasta tonight.

14. Manspread

Ever notice how some men sit with their legs so wide apart in public places that they take up more than one seat?

This behavior, commonly observed on public transportation such as trains and buses and in public waiting areas, is known as manspreading (man + spreading).

Wouldn’t it be nice if people would be more considerate about manspreading during busy times of the day?

15. Facepalm

Facepalm (you’ll also see it spelled as two words: face and palm) is a new word that describes the act of covering your face with your hand when you’re in difficult or uncomfortable situations. It’s a pretty natural thing to do when we’re feeling embarrassed, frustrated or very disappointed.

He had to facepalm when his boss pointed out typos in his report after he’d checked it three times.

16. Froyo

Here’s another new word that has to do with food: froyo. That’s right, it’s not hard to figure out that froyo is short for frozen yogurt, a cold dessert that’s similar to ice cream and a bit healthier.

On a hot day, you can call me up for a froyo any time.

17. Hangry

Have you ever been hangry? I know I have. Hangry (hungry + angry) is when you’re in a bad mood and feeling frustrated because you need to eat right now.

I haven’t eaten anything since breakfast. I’m hangry and you’re not going to like me very much.

18. Photobomb

Remember the time you posed for that perfect photo (or so you thought!) only to find that someone spoiled it by appearing in view when the photo was taken?

That’s a photobomb. The unintended person is a photobomber. They could be either a random stranger just walking by, or a prankster deliberately photobombing you.

You wouldn’t believe how hard it was to avoid photobombs when we were taking pictures at the beach.

19. Binge Watch

To binge watch is to watch many episodes of a TV series one after another without stopping. The word binge by itself means to overdo something.

I spent the whole weekend binge watching the TV series “Billions” with my roommate.

20. Fitspiration

Every end of the year, we take time out to plan our goals for the new year. What can we do? Eat healthier? Work out more? Get more fit? Yes, but we need inspiration!

So we look around and, yes, we have a new word for that.

Fitspiration (fitness + inspiration) refers to the people, pictures and social media posts that inspire us to keep pushing ourselves and staying committed to our fitness goals.

I was pretty impressed that my co-worker had stuck a picture of Chris Hemsworth on his office wall for fitspiration.

21. Mansplain

Similar to manspreading, the word mansplain (man + explain) refers to how some men explain things to a woman in a condescending (superior-seeming) way that sounds like he’s either better than her or he knows more than her.

Whenever he starts mansplaining, all the women in the room roll their eyes and stop paying attention.

22. Glamping

Those who don’t fancy camping in the outdoors with no proper facilities like toilets, etc. will be happy to know that there’s now a thing called glamping.

Glamping (glamorous + camping) refers to camping that comes with all of the modern facilities that you can think of like nice bathrooms, etc.

No, I won’t go camping with you. But if it’s glamping, I’m in.

23. Side-eye

Have you ever given someone a disapproving look with sideways glances of your eyes? This is called giving someone the side-eye to show you’re annoyed and don’t approve of them or their behavior.

I had good reason to give him the side-eye. He just kept yawning in front of me with his mouth open.

24. Fast Fashion

In the ever-changing world of fashion, the term fast fashion refers to the concept of big-name designers and manufacturers such as H&M, Esprit and Levi’s introducing the latest fashion trends to stores at affordable prices.

It seems she’s on a tight budget and can’t afford anything but fast fashion.

25. Staycation

Ever taken vacation days from work and have nowhere to go? Well, if you have no travel plans, then spend your vacation at home and have a staycation (stay + vacation).

I go see the world every chance I get. So everyone was surprised that I’m having a staycation this holiday.

So there you go, a list of exciting new words in English for you to start using today. Challenge yourself to master them all as quickly as possible. Remember, practice makes perfect. Happy practicing!

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Match the words and phrases with translations.

Match the words with their definitions.

the ability to move from place to place

the ability to produce original things, ideas, etc.

thinking about smth carefully before reaching a conclusion

the ability to understand and learn

not natural, made by humans

Match the words from the two columns to make collocations.

Choose the correct answer.

become a reality; cater for our needs; mow the lawn; vacuum the carpets; perform tasks; come to harm

I need a robot that can

because one of my chores is to keep the garden tidy.

There are many gadgets and machines on the market that already

, but scientists promise that future robots will satisfy even more of our demands.

Robots in factories are there to

that are dangerous or difficult for humans.

Floors in homes will never be dirty again once there are robots to

!

Should we trust robots to take on jobs where humans could

if they made a mistake?

Do you think that robotic doctors will ever

?

Choose the correct answer.

-We

to France soon!

-Have a good time!

-Thanks. I

you a postcard when I

in Paris.

-I think it

be great.

Choose the right words to complete the sentences.

-Where are you going to stay in Moscow?

-We’ve already booked a room. We

at the May Princess not far from the city centre.

-What are you going to do there?

-We

most of the sights of the city, if we

time! But I don’t think we

that.

Read the text and fill in the gaps transforming the words

entertain, grow, communicate, circle, excite, base

The Internet

Part 1

Modern Technology has had a great effect on the lives of people and their

habits. Today, all over the world the Internet has undergone a phenomenal

. It has become a very important data-gathering and

source. The Net

the globe. Young people spend a lot of time on their computers because it’s

and they have found in the Net new ways of meeting one of the

human needs: the desire to communicate with other people.

Read the text and fill in the gaps transforming the words

change, print, meet, normal, success, busy

The Internet

Part 2

What is the practical side of it?

People can

electronic messages. The Internet has replaced a post office,

, and

-place. Most companies have their own websites; others exist only on the Internet. They are

called “dot com” companies. Some of the most

Net businessmen are teenagers who are still at school. For example, Tom Hadfield, 16, started a football results website called soccer-net, and it became a great

.

Homonymy in modern English

Автор: учитель английского языка

Ермилова Елена Александровна

Introduction

Homonyms

are the words different in meaning, but similar in sound.

Homonyms

are used in stilistics as members of stylistic figures called puns.

The

meaning of homonymy is very actual in our days. The appearance of new,

homonymic meanings is one of the main trends in development of Modern English,

especially in its colloquial layer, which, in its turn at high degree is supported

by development of modern informational technologies and simplification of alive

speech.

The

abundance of homonyms is also closely connected with such a characteristic

feature of the English language as the phonetic identity of word and stem or, in

other words, the predominance of free forms among the most frequent roots. It

is quite obvious that if the frequency of words stands in some inverse

relationship to their length, the monosyllabic words will be the most frequent.

Moreover, as the most frequent words are also highly polysemantic, it is only

natural that they develop meanings, which in the coarse of time may deviate

very far from the central one.

In

general, homonymy is intentionally sought to provoke positive, negative or

awkward connotations. Concerning the selection of initials, homonymy with

shortened words serves the purpose of manipulation. The demotivated process of

a shortened word hereby leads to re-motivation. The form is homonymously

identical with an already lexicalized linguistic unit, which makes it easier to

pronounce or recall, thus standing out from the majority of acronyms. This

homonymous unit has a secondary semantic relation to the linguistic unit.

Homonymy of names functions as personified metaphor with the result

that the homonymous name leads to abstraction. The resultant new word

coincides in its phonological realization with an existing word in English.

However, there is no logical connection between the meaning of the acronym and

the meaning of the already existing word, which explains a great part of the

humor it produces.

In the coarse of time the number of homonyms on the whole increases,

although occasionally the conflict of homonyms ends in word loss.

The Object is – lexical

figures.

The Subject is – homonymy

in modern English.

The aim is —to

study homonymy in modern English.

The tasks of the work:

1) to give the determination to homonymy

2) to examine the classification of homonyms

3) to examine distinguishing homonymy and polysemy

4) to learn the literature on the subject

This work consists of: introduction, two chapters and bibliography.

Chapter Ι Homonymy as learning of homonyms

1. Determination of homonymy

Two or more words identical in sound

and spelling but different in meaning, distribution and in many cases origin

are called homonyms. The term is derived from Greek “homonymous”

(homos – “the same” and onoma – “name”) and thus expresses very well the

sameness of name combined with the difference in meaning.

Modern

English is exceptionally rich in homonymous words and word-forms. It is held

that languages where short words abound have more homonyms than those where

longer words are prevalent. Therefore it is sometimes suggested that abundance

of homonyms in Modern English is to be accounted for by the monosyllabic

structure of the commonly used English words.

Not

only words but other linguistic units may be homonymous. Here, however, we are

concerned with the homonymy of words and word-forms only, so we shall not touch

upon the problem of homonymous affixes or homonymous phrases When analyzing

different cases of homonymy we find that some words are homonymous in all their

forms, i.e. we observe full homonymy of the paradigms of two or more different

words as, e.g., in seal a sea animal and seal—a design printed on paper by

means of a stamp’.[3,p144] The paradigm «seal, seal’s, seals, seals'»

is identical for both of them and gives no indication of whether it is seal (1)

or seal (2) that we are analyzing. In other cases, e.g. seal—a sea animal’ and

(to) seal (3)—’to close tightly, we see that although some individual

word-forms are homonymous, the whole of the paradigm is not identical. Compare,

for instance, the-paradigms:

1.

(to)seal-seal-seal’s-seals-seals’

2.

seal-seals-sealed-sealing, etc.

1

Professor O. Jespersen calculated that there are roughly four times as many

monosyllabic as polysyllabic homonyms. It is easily observed that only some of

the word-forms (e.g. seal, seals, etc.) are homonymous, whereas others (e.g.

sealed, sealing) are not. In such cases we cannot speak of homonymous words but

only of homonymy of individual word-forms or of partial homonymy. This is true

of a number of other cases, e.g. compare find [faind], found [faund], found

[faund] and found [faund], founded [‘faundidj, founded [faundid]; know [nou],

knows [nouz], knew [nju:], and no [nou]; nose [nouz], noses [nouziz]; new

[nju:] in which partial homonymy is observed.

From the examples of homonymy discussed above it

follows that the bulk of full homonyms are to be found within the same parts of

speech (e.g. seal(1) n—seal(2) n), partial homonymy as a rule is observed in word-forms

belonging to different parts of speech (e.g. seal n—seal v). This is not to say

that partial homonymy is impossible within one part of speech. For instance in

the case of the two verbs Me [lai]—’to be in a horizontal or resting

position’—lies [laiz]—lay [lei]—lain [lein] and lie [lai]—’to make an untrue

statement’—lies [laiz]—lied [laid]—lied [laid] we also find partial homonymy as

only two word-forms [lai], [laiz] are homonymous, all other forms of the two

verbs are different. Cases of full homonymy may be found in different parts of

speech as, e.g., for [for]—preposition, for [fo:]—conjunction and four [fo:]

—numeral, as these parts of speech have no other word-forms.

2. Classification of homonyms

The

most widely accepted classification is that recognizing homonyms proper,

homophones and homographs.

Homonyms proper

Homonyms proper are words, as I have already mentioned, identical in

pronunciation and spelling, like fast and liver above. Other

examples are: back n ‘part of the body’ – back adv ‘away from the

front’ – back v ‘go back’; ball n ‘a gathering of people for

dancing’ – ball n ‘round object used in games’; bark n ‘the noise

made by dog’ – bark v ‘to utter sharp explosive cries’ – bark n

‘the skin of a tree’ – bark n

‘a

sailing ship’; base n ‘bottom’ – base v ‘build or place upon’ – base

a ‘mean’; bay n ‘part of the sea or lake filling wide-mouth opening of

land’ – bay n ‘recess in a house or room’ – bay v ‘bark’ – bay

n ‘the European laurel’.

The

important point is that homonyms are distinct words: not different meanings

within one word.

Homophones

Homophones are words of the same sound but of different spelling and meaning:

air –

hair; arms – alms; buy – by; him – hymn; knight – night; not – knot; or – oar;

piece – peace; rain – reign; scent – cent; steel – steal; storey – story; write

– right and many others.

In

the sentence The play-wright on my right thinks it right that some

conventional rite should symbolize the right of every man to write as he

pleases the sound complex [rait] is a noun, an adjective, an adverb and a

verb, has four different spellings and six different meanings. The difference

may be confined to the use of a capital letter as in bill and Bill, in the

following example:

“How

much is my milk bill?”

“Excuse

me, Madam, but my name is John.”

On

the other hand, whole sentences may be homophonic: The sons raise meat – The

sun’s rays meet. To understand these one needs a wider context. If you hear

the second in the course of a lecture in optics, you will understand it without

thinking of the possibility of the first.

Homographs

Homographs are words different in sound and in meaning but accidentally

identical in spelling: bow [bou] – bow [bau]; lead [li:d] – lead [led]; row

[rou] – row [rau]; sewer [‘soue] – sewer [sjue]; tear [tie] – tear [tee]; wind [wind] – wind [waind] and many

more.

It

has been often argued that homographs constitute a phenomenon that should be

kept apart from homonymy, as the object of linguistics is sound language. This

viewpoint can hardly be accepted. Because of the effects of education and

culture written English is a generalized national form of expression. An

average speaker does not separate the written and oral form. On the contrary he

is more likely to analyze the words in terms of letters than in terms of

phonemes with which he is less familiar. That is why a linguist must take into

consideration both the spelling and the pronunciation of words when analyzing

cases of identity of form and diversity of content. [10, p12]

Modern

English has a very extensive vocabulary; the number of words according to the

dictionary data is no less than 400, 000.A question naturally arises whether

this enormous word-stock is composed of separate independent lexical units, or

may it perhaps be regarded as a certain structured system made up of numerous

interdependent and interrelated sub-systems or groups of words. This problem

may be viewed in terms of the possible ways of classifying vocabulary items.

Words can be classified in various ways. Here, however, we are concerned only

with the semantic classification of words which gives us a better insight into

some aspects of the Modern English word-stock. Attempts to study the inner

structure of the vocabulary revealed that in spite of its heterogeneity the

English word-stock may be analyzed into numerous sub-systems the members of

which have some features in common, thus distinguishing them from the members

of other lexical sub-systems. Classification into monosynaptic and polysemantic

words is based on the number of meanings the word possesses. More detailed

semantic classifications are generally based on the semantic similarity (or

polarity) of words or their component morphemes. Below we give a brief survey

of some of these lexical groups of current use both in theoretical

investigation and practical class-room teaching.

Accordingly, Professor A.I. Smirnitsky classifieds homonyms into two large

classes:

a)

full homonyms

b)

partial homonyms

Full

homonyms

Full

lexical homonyms are words, which represent the same category of parts of

speech and have the same paradigm.

Match

n – a game, a contest

Match

n – a short piece of wood used for producing fire

Wren

n – a member of the Women’s Royal Naval Service

Wren

n – a bird

Partial

homonyms

Partial homonyms are subdivided into three subgroups:

A.

Simple lexico-grammatical partial homonyms are words, which belong to the same

category of parts of speech. Their paradigms have only one identical form, but

it is never the same form, as will be soon from the examples:

(to)

found v

found v (past indef., past part. of to find)

(to)

lay v

lay v (past indef. of to lie)

(to)

bound v

bound v (past indef., past part. of to bind)

B.

Complex lexico-grammatical partial homonyms are words of different categories

of parts of speech, which have identical form in their paradigms.

Rose

n

Rose

v (past indef. of to rise)

Maid

n

Made

v (past indef., past part. of to make)

Left

adj

Left

v (past indef., past part. of to leave)

Bean

n

Been

v (past part. of to be)

One

num

Won v

(past indef., past part. of to win)

C.

Partial lexical homonyms are words of the same category of parts of speech

which are identical only in their corresponding forms.

to

lie (lay, lain) v

to

lie (lied, lied) v

to

hang (hung, hung) v

to

hang (hanged, hanged) v

to

can (canned, canned)

(I)

can (could)

Chapter

ΙΙ Problems of Homonymy

1. Polysemy and homonymy: etymological

and semantic criteria

Words

borrowed from other languages may through phonetic convergence become

homonymous. Old Norse has and French race are homonymous in Modern English (cf.

race1 [reis]—’running’ and race [reis] ‘a distinct ethnical stock’). There are

four homonymic words in Modern English: sound —’healthy’ was already in Old

English homonymous with sound—’a narrow passage of water’, though

etymologically they are unrelated. Then two more homonymous words appeared in

the English language, one comes from Old French son (L. sonus) and denotes

‘that which is or may be heard’ and the other from the French sunder the

surgeon’s probe. One of the most debatable problems in semasiology is the

demarcation line between homonymy and polysemy, i.e. between different meanings

of one word and the meanings of two homonymous words. [15,p55]

If

homonymy is viewed diachronically then all cases of sound convergence of two

or, more words may be safely regarded as cases of homonymy as, e.g., sound i,

sound2, sound-e, and sound4 which can be traced back to four etymologically

different words. The transition from polysemy to homonymy is a gradual

process, so it is hardly possible to point out the precise stage at which

divergent semantic development tears asunder all ties of etymological kinship

and results in the appearance of two separate words. In the case of flower,

flour, e.g., it is mainly the resultant divergence of graphic forms that gives

us grounds to assert that the two meanings which originally made up the

semantic structure of one word are now apprehended as belonging to two

different words.

Synchronically

the differentiation between homonymy and polysemy is wholly based on the

semantic criterion. It is usually held that if a connection between the various

meanings is apprehended by the speaker, these are to be considered as making up

the semantic structure of a polysemantic word, otherwise it is a case of

homonymy, not polysemy.

Thus

the semantic criterion implies that the difference between polysemy and

homonymy is actually reduced to the differentiation between related and unrelated

meanings. This traditional semantic criterion does not seem to be reliable,

firstly, because various meanings of the same word and the meanings of two or

more different words may be equally apprehended by the speaker as

synchronically unrelated. For instance, the meaning ‘a change in the form of a

noun or pronoun’ which is usually listed in dictionaries as one of the meanings

of case!—’something that has happened’, ‘a question decided in a court of law’

seems to be just as unrelated to the meanings of this word as to the meaning of

case2 —’a box, a container’, etc

Secondly

in the discussion of lexico-grammatical homonymy it was pointed out that some

of the mean of homonyms arising from conversion (e.g. seal in—seal 3 v; paper

n—paper v) are related, so this criterion cannot be applied to a large group of

homonymous word-forms in Modern English. This criterion proves insufficient in

the synchronic analysis of a number of other borderline cases, e.g.

brother—brothers— ‘sons of the same parent’ and brethren—’fellow members of a

religious society’. The meanings may be apprehended as related and then we can

speak of polysemy pointing out that the difference in the morphological

structure of the plural form reflects the difference of meaning. Otherwise we may

regard this as a case of partial lexical homonymy. The same is true of such

cases as hang—hung—hung—’to support or be supported from above’ and

hang—hanged—hanged—’to put a person to death by hanging’ all of which are

traditionally regarded as different meanings of one polysemantic word.

It

is sometimes argued that the difference between related and unrelated meanings

may be observed in the manner in which the meanings of polysemantic words are

as a rule relatable. It is observed that different meanings of one word have

certain stable relationships which are not to be found between the meanings of

two homonymous words. A clearly perceptible connection, e.g., can be seen in

all metaphoric or metonymic meanings of one word (e.g., foot of the man— foot

of the mountain, loud voice—loud colors, etc.,1 cf. also deep well and deep

knowledge, etc.).

Such

semantic relationships are commonly found in the meanings of one word and are

considered to be indicative’ of polysemy. It is also suggested that the

semantic connection may be described in terms of such features as, e.g., form

and function (cf. horn of an animal and horn as an instrument), process and

result (to run—’move with quick steps’ and a run—act of running).

Similar

relationships, however, are observed between the meanings of two homonymic

words, e.g. to run and a run in the stocking.

Moreover

in the synchronic analysis of polysemantic words we often find meanings that

cannot be related in any way, as, e.g., the meanings of the word case discussed

above. Thus the semantic criterion proves not only untenable in theory but also

rather vague and because of this impossible in practice as it cannot be used in

discriminating between several meanings of one word and the meanings of two

different words.

A

more objective criterion of distribution suggested by some linguists is

criteria: undoubtedly helpful, but mainly increase-distribution of lexico —

grammatical and grammatical homonymy. When homonymic words of Context, belong

to different parts of speech they differ not only in their semantic structure,

but also in their syntactic function and consequently in their distribution. In

the homonymic pair paper n—(to) paper v the noun may be preceded by the article

and followed by a verb; (to) paper can never be found in identical

distribution. This formal criterion can be used to discriminate not only

lexico-grammatical but also grammatical homonyms, but it often fails the

linguists in cases of lexical homonymy, not differentiated by means of

spelling.

Homonyms

differing in graphic form, e.g. such lexical homonyms as knight—night or

flower—flour, are easily perceived to be two different lexical units as any

formal difference of words is felt as indicative of the existence of two

separate lexical units. Conversely lexical homonyms identical both in

pronunciation and spelling are often apprehended as different meanings of one

word. It is often argued that the context in which the words are used suffices

to perceive the borderline between homonymous words, e.g. the meaning of case

in several cases of robbery can be easily differentiated from the meaning of

case2 in a jewel case, a glass case. This however is true of different meanings

of the same word as recorded in dictionaries, e.g. of case as can be seen by

comparing the case will be tried in the law-court and the possessive case of

the noun. Thus, the context serves to differentiate meanings but is of little

help in distinguishing between homonymy and polysemy. Consequently we have to

admit that no formal means have as yet been found to differentiate between

several meanings of one word and the meanings of its homonyms. We must take

into consideration the note that in the discussion of the problems of polysemy

and homonymy we proceeded from the assumption that the word is the basic unit

of language.

1

It should be pointed out that there is another approach to the concept of the

basic language unit which makes the problem of differentiation between polysemy

and homonymy irrelevant.

Some

linguists hold that the basic and elementary units at the semantic level of

language are the lexico-semantic variants of the word, i.e. individual

word-meanings. In that case, naturally, we can speak only of homonymy of

individual lexico-semantic variants, as polysemy is by definition, at least on

the synchronic plane, the co-existence of several meanings in the semantic

structure of the word. The criticism of this viewpoint cannot be discussed

within the framework different semantic structure. The problem of homonymy is

mainly the problem of differentiation between two different semantic structures

of identically sounding words.

2.

Homonymy of words and homonymy of individual word-forms may be regarded as full

and partial homonymy. Cases of full homonymy are generally observed in words

belonging to the same part of speech. Partial homonymy is usually to be found

in word-forms of different parts of speech.

3.

Homonymous words and word-forms may be classified by the type of meaning that

serves to differentiate between identical sound-forms. Lexical homonyms differ

in lexical meaning, lexico-grammatical in both lexical and grammatical meaning,

whereas grammatical homonyms are those that differ in grammatical meaning only.

4.

Lexico-grammatical homonyms are not homogeneous. Homonyms arising from conversion

have some related lexical meanings in their semantic structure. Though some

individual meanings may be related the whole of the semantic structure of

homonyms is essentially different.

5.

If the graphic form of homonyms is taken into account, they are classified on

the basis of the three aspects — sound-form, graphic form and meaning — into

three big groups: homographs (identical graphic form), homophones (identical

sound-form) and perfect homonyms (identical sound- and graphic form).

6.

The two main sources of homonymy are:

1)

diverging meaning development of one polysemantic word, and

2)

convergent sound development of two or more different words. The latter is the

most potent factor in the creation of homonyms.

7.

The most debatable problem of homonymy is the demarcation line between homonymy

and polysemy, i.e. between different meanings of one word and the meanings of

two or more phonemically different words.

8.

The criteria used in the synchronic analysis of homonymy are:

1)

the semantic criterion of related or unrelated meanings;

2)

the criterion of spelling;

3)

the criterion of distribution, and

4)

the criterion of context.

In

grammatical and lexico-grammatical homonymy the reliable criterion is the

criterion of distribution. In lexical homonymy there are cases when none of the

criteria enumerated above is of any avail. In such cases the demarcation line

between polysemy and homonymy is rather fluid.’

9.

The problem of discriminating between polysemy and homonymy in theoretical

linguistics is closely connected with the problem of the basic unit at the

semantic level of analysis.

In

applied linguistics this problem is of the greatest importance in lexicography

and also in machine translation.

During

several scores of years the problem of distinction of polysemy and homonymy in

a language was constantly arising the interest of lexicologists is in many

countries.

2. Distinguishing homonymy from

polysemy

The

synchronic treatment of English homonyms brings to the forefront a set of

problems of paramount importance for different branches of applied linguistics:

lexicography, foreign language teaching and information retrieval. These

problems are: the criteria distinguishing homonymy from polysemy, the

formulation of rules for recognizing different meanings of the same homonym in

terms of distribution, and the description of difference between patterned and

non-patterned homonymy. It is necessary to emphasize that all these problems

are connected with difficulties created by homonymy in understanding the

message by the reader or listener, not with formulating one’s thoughts; they

exist for the speaker though in so far as he must construct his speech in a way

that would prevent all possible misunderstanding.

All three problems are so closely

interwoven that it is difficult to separate them. So we shall discuss them as

they appear for various practical purposes. For a lexicographer it is a problem

of establishing word boundaries. It is easy enough to see that match, as

in safety matches, is a separate word from the verb match ‘to

suit’. But he must know whether one is justified in taking into one entry match,

as in football match, and match in meet one’s match ‘one’s

equal’.

On the synchronic level, when

the difference in etymology is irrelevant, the problem of establishing the

criterion for the distinction between different words identical in sound form,

and different meanings of the same word becomes hard to solve. Nevertheless the

problem cannot be dropped altogether as upon an efficient arrangement of

dictionary entries depends the amount of time spent by readers in looking up a

word: a lexicographer will either save or waste his readers’ time and effort.

Actual solutions

differ. It is a wildly spread practice in English lexicography to combine in

one entry words of identical phonetic form showing similarity of lexical

meaning or, in other words, revealing a lexical invariant, even if they belong

to different parts of speech. In our country a different trend has settled.

Polysemy characterizes words that have more than one meaning — any dictionary

search will reveal that most words are polysemes — word itself has 12

significant senses, according to WordNet. This means that the word,

word, is used in texts scanned by lexicographers to represent twelve different

concepts.

The point is that words are

not meanings, although they can have many meanings. Lexicographers make a

clear distinction between different words by writing separate entries for each

of them, whether or not they are spelled the same way. The dictionary of Fred

W. Riggs has 5 entries for the form, bow — this shows that

lexicographers recognize this form (spelling) as a way of representing five

different words. Three of them are pronounced bo and two bau, which identifies two

homophones in this set of five homographs, each of which is a polyseme, capable

of representing more than one concept. To summarize: bow is a word-form that

stands for two different homophones and, as a homograph, represents five

different words.

Moreover, the form bow

is polysemic and can represent more than 20 concepts (its various meanings or

senses). By gratuitously putting meaning in its definition of a homograph, WordNet

can mislead readers who might think that a word is a homonym because it has

several meanings — but having one word represent more than one concept is

normal — just consider term as an example: it can not only refer to the

designator of a concept, but also the duration of something, like the school

year or a politician’s hold on office, a legal stipulation, one’s standing in a

relationship (on good terms) and many other notions — more than 17 are

identified in the dictionary edited be Fred W. Riggs. By contrast, homonyms are

different words and each of them (as a polyseme) can have multiple meanings.

To make their definitions precise, lexicographers need

criteria to distinguish different words from each other even though they are

spelled the same way. This usually hinges on etymology and, sometimes, parts of

speech. One might, for example, think that that firm ‘steadfast’ and firm

‘business unit’ are two senses of one word (polyseme). Not so! Lexicographers

class them as different words because the first evolved from a Latin stem

meaning throne or chair, and the latter from a different root in Italian

meaning signature.

Dictionaries are not uniform in their treatment of the

different grammatical forms of a word. In some of them, the adjective firm

(securely) is handled as a different word from the noun firm (to settle)

even though they have the same etymology. Fred W. Riggs isn’t persuaded such

differences justify treating grammatical classes (adjectives, nouns, and verbs)

of a word-form that belongs to a single lexeme as different words — the

precise meaning of lexeme is 1. WordNet is a Lexical Database for

English prepared by the Cognitive Science Laboratory at Princeton University.

explained below. The relevant point here is that deciding

whether or not a form identifies one or more than one lexeme does not hinge on meanings.

There is agreement that a word-form represents different words when they

evolved from separate roots, and some lexicographers treat each grammatical use

of a lexeme (noun, verb, adjective) as though it were a different word.

The etymological criterion may lead to distortion of the

present day situation. The English vocabulary of today is not a replica of the

Old English vocabulary with some additions from borrowing. It is in many

respects a different system, and this system will not be revealed if the

lexicographers guided by etymological criteria only.

A more or less simple, if not very rigorous, procedure

based on purely synchronic data may be prompted by analysis of dictionary

definitions. It may be called explanatory transformation. It is based on

the assumption that if different senses rendered by the same phonetic complex

can be defined with the help of an identical kernel word-group, they may be

considered sufficiently near to be regarded as variants of the same word; if

not, they are homonyms.

Consider the following set of examples:

1.

A child’s voice is heard.1

2.

His voice…was…annoyingly well-bred.2

3.

The voice-voicelessness

distinction…sets up some English consonants in opposed pairs…

4.

In the voice contrast of active and

passive…the active is the unmarked form.

The first variant (voice1) may be

defined as ‘sound uttered in speaking or singing as characteristic of a

particular person’, voice2 as ‘mode of uttering sounds in

speaking or singing’, voice3 as ‘the vibration of the vocal chords

in sounds uttered’. So far all the definitions contain one and the same kernel

element rendering the invariant common basis of their meaning. It is, however,

impossible to use the same kernel element for the meaning present in the fourth

example. The corresponding definition is: “Voice – that form of the verb that

expresses the relation of the subject to the action”. This failure to satisfy

the same explanation formula sets the fourth meaning apart. It may then be

considered a homonym to the polysemantic word embracing the first three

variants. The procedure described may remain helpful when the items considered

belong to different parts of speech; the verb voice may mean, for

example, ‘to utter a sound by the aid of the vocal chords’.

This brings us to the problem of patterned homonymy,

i.e. of the invariant lexical meaning present in homonyms that have developed

from one common source and belong to various parts of speech.

Is a lexicographer justified in placing the verb voice

with the above meaning into the same entry with the first three variants of

the noun? The same question arises with respect to after or before

– preposition, conjunction and adverb.

English lexicographers think it quite possible for one

and the same word to function as different parts of speech. Such pairs as act

n – act v; back n — back v; drive n – drive v;

the above mentioned after and before and the like, are all

treated as one word functioning as different parts of speech. This point of

view was severely criticized. It was argued that one and the same word could

not belong to different parts of speech simultaneously, because this would

contradict the definition of the word as a system of forms.

This viewpoint is not faultless

either; if one follows it consistently, one should regard as separate words all

cases when words are countable nouns in one meaning and uncountable in another,

when verbs can be used transitively and intransitively, etc. In this case hair1

‘all the hair that grows on a person’s head’ will be one word, an uncountable

noun; whereas ‘a single thread of hair’ will be

denoted by another word (hair2)

which, being countable, and thus different in paradigm, cannot be considered

the same word. It would be tedious to enumerate all the absurdities that will

result from choosing this path. A dictionary arranged on these lines would

require very much space in printing and could occasion much wasted time in use.

The conclusion therefore is that efficiency in lexicographic work is secured by

a rigorous application of etymological criteria combined with formalized

procedures of establishing a lexical invariant suggested by synchronic

linguistic methods.

As to those concerned with

teaching of English as a foreign language, they are also keenly interested in

patterned homonymy. The most frequently used words constitute the greatest

amount of difficulty, as may be summed up by the following jocular example: I

think that this “that” is a conjunction but that that “that” that that man used

as pronoun.

A correct understanding of this

peculiarity of contemporary English should be instilled in the pupils from the

very beginning, and they should be taught to find their way in sentences where

several words have their homonyms in other parts of speech, as in Jespersen’s

example: Will change of air cure love? To show the scope of the problem

for the elementary stage a list of homonyms that should be classified as

patterned is given below:

Above, prp, adv, a; act,

n, v; after, prp, adv, cj; age, n, v; back, n, adv, v; ball,

n, v; bank, n, v; before, prp, adv, cj; besides, prp, adv;

bill, n, v; bloom, n, v; box, n, v. The other examples

are: by, can, close, country, course, cross, direct, draw, drive, even,

faint, flat, fly, for, game, general, hard, hide, hold, home, just, kind, last,

leave, left, lie, light, like, little, lot, major, march, may, mean, might,

mind, miss, part, plain, plane, plate, right, round, sharp, sound, spare,

spell, spring, square, stage, stamp, try, type, volume, watch, well, will.

For the most part all these words

are cases of patterned lexico-grammatical homonymy taken from the minimum

vocabulary of the elementary stage: the above homonyms mostly differ within

each group grammatically but possess some lexical invariant. That is to say, act

v follows the standard four-part system of forms with a base form act,

an s-form (act-s), a Past Indefinite Tense form (acted) and an

ing-form (acting) and takes up all syntactic functions of verbs, whereas

act n can have two forms, act (sing.) and act (pl.). Semantically

both contain the most generalized component rendering the notion of doing

something.

Recent investigations have shown

that it is quite possible to establish and to formalize the differences in

environment, either syntactical or lexical, serving to signal which of the

several inherent values is to be ascribed to the variable in a given context.

An example of distributional analysis will help to make this point clear.

The distribution of a

lexico-semantic variant of a word may be represented as a list of structural

patterns in which it occurs and the data on its combining power. Some of the

most typical structural patterns for a verb are: N + V + N; N + V + Prp + N; N

+ V + A; N + V + adv; N + V + to + V and some others. Patterns for nouns are

far less studied, but for the present case one very typical example will

suffice. This is the structure: article + A + N.

In the following

extract from “A Taste of Honey” by Shelagh Delaney the morpheme laugh

occurs three times: I can’t stand people who laugh at other people. They’d

get a bigger laugh, if they laughed at themselves.

We recognize laugh

used first and last here as a verb, because the formula is N + laugh +

prp + N and so the pattern is in both cases N + V + prp + N. In the beginning

of the second sentence laugh is a noun and the pattern is article +

A + N.

This elementary example

can give a very general idea of the procedure which can be used for solving

more complicated problems.

We may sum up our

discussion by pointing out that whereas distinction between polysemy homonymy

is relevant and important for lexicography it is not relevant for the practice

of either human or machine translation. The reason for this is that different

variants of a polysemantic word are not less conditioned by context then

lexical homonyms. In both cases the identification of the necessary meaning is

based on the corresponding distribution that can signal it and must be present

in the memory either of the pupil or the machine. The distinction between

patterned and non-patterned homonymy, greatly underrated until now, is of far

greater importance. In non-patterned homonymy every unit is to be learned

separately both from the lexical and grammatical points of view. In patterned

homonymy when one knows the lexical meaning of a given word in one part of

speech, one can accurately predict the meaning when the same sound complex

occurs in some other part of speech, provided, of coarse, that there is

sufficient context to guide one.

Conclusion

We

have come to conclusion that:

1.Homonyms

are the words identical in sound and spelling, but different in meaning.

Modern

English is exceptionally rich in homonymous words and word-forms. It is held

that languages where short words abound have more homonyms than those where

longer words are prevalent. Therefore it is sometimes suggested that abundance

of homonyms in Modern English is to be accounted for by the monosyllabic

structure of the commonly used English words.

2.Homonyms

are classifiable into:

-homophones

— homographs

— homonyms proper

Homophones

are the words of the same sound but of different spelling and meaning.

Homographs

are words different in sound and in meaning, but accidentally identical in

spelling.

Homonyms

proper are words identical in pronunciation and spelling.

3. Synchronically the differentiation

between homonymy and polysemy is wholly based on the semantic criterion. It is

usually held that if a connection between the various meanings is apprehended

by the speaker, these are to be considered as making up the semantic structure

of a polysemantic word, otherwise it is a case of homonymy, not polysemy.

Thus

the semantic criterion implies that the difference between polysemy and

homonymy is actually reduced to the differentiation between related and

unrelated meanings. This traditional semantic criterion does not seem to be

reliable, firstly, because various meanings of the same word and the meanings

of two or more different words may be equally apprehended by the speaker as

synchronically unrelated.

4.Having

learned the literature , we have come to conclusion that great contribution to

lexicology was brought by: Akhmanova O.S, Potter S., Smirnitsky A.I.

Bibliography

1 Abayev

V.I. Homonyms T. O’qituvchi 1981 p. 29

2. Akhmanova

O.S. Lexicology: Theory and Method. M. 1972 p. 59

3.Arakin English Russian Dictionary

M.Russky Yazyk 1978 p. 119

4. Arnold

I.V. The English Word M. High School 1986 p. 143

5. Bloomsbury Dictionary of New Words. M. 1996 p.276

6. Buranov, Muminov

Readings on Modern English Lexicology T. O’qituvchi 1985 p. 47

7. Burchfield R.W.

The English Language. Lnd. ,1985 p.47

8. Canon G.

Historical Changes and English Wordformation: New Vocabulary items. N.Y., 1986.

p.284

9. Dubenets E.M.

Modern English Lexicology (Course of Lectures) M., Moscow State Teacher

Training University Publishers 2004 p. 31

10. Ginzburg

R.S. et al. A Course in Modern English Lexicology. M., 1979 p. 82

11 .Halliday

M.A.K. Language as Social Semiotics. Social Interpretation of Language and

Meaning. Lnd., 1979.p.53

12. Hornby

The Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English. Lnd. 1974 p. 111

13 . Howard

Ph. New words for Old. Lnd., 1980. p.311

14. Jespersen.

Linguistics. London, 1983, p. 412

15. Jespersen

,Otto. Growth and Structure of the English Language. Oxford, 1982 p. 249

16. Longman

Lexicon of Contemporary English. Longman. 1981p.23

17. Maurer

D.W. , High F.C. New Words — Where do they come from and where do they go.

American Speech., 1982.p.171

18. Potter

S. Modern Linguistics. Lnd., 1957 p. 54

19. Schlauch,

Margaret. The English Language in Modern Times. Warszava, 1965. p.342

20. Sheard,

John. The Words we Use. N.Y..,1954.p.3

21. Smirnitsky A.I.

Homonyms in English M.1977 p. 90

22. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English. Oxford 1964, p.147

23. Aпресян Ю.Д.Лексическая семантика. Омонимические

средства языка. М.1974. 46c.

24. Арнольд

И.В. Лексикология современного английского языка.М. Высшая школа 1959.- 212c.

25. Беляева

Т.М., Потапова И.А. Английский язык за пределами Англии. Л. Изд-во ЛГУ 150c.

26. Виноградов

В. В. Лексикология и лексикография. Избранные труды. М.

1977- .122c

Along with everyday and familiar vocabulary, there is a passive vocabulary, which includes archaisms, historicism and neologisms.

Archaism is an obsolete word that has been replaced by a synonym in modern speech.

The archaisms include words and expressions that are outdated and are not used in modern speech because they have corresponding synonyms or, on the other hand, archaisms include words that have no synonyms because the concepts expressed by these words have ceased to play any role in the modern life of society.

In English lexicology, archaisms, which are the words that have finally emerged from a language that are marked «old» are denoted by the term «obsolete words». Their meanings are understandable, but they are almost never used. It is unlikely that today we will hear the following words: ere, hither, thither.

The reason for the appearance of archaisms is in the development of the language and in the updating of its dictionary.

The research work presents usage of archaisms in the English speech and literature. We have analysed the usage of archaisms in the work of one of the most popular authors of the XIV century.

The purposeis to study the different types of archaisms, and to reveal the percent of words which underwent changes in its composition after the passage of seven centuries in «The Canterbury Tales».

Archaisms are divided into the following types: linguistic, lexico-semantic, grammatical, morphological, poetic and lexical.

The term «Linguistic archaism» means that the subject still exists, but it is already called by another word: valley, unlucky, by chance. The long-term meanings of words have disappeared from the lexico-semantic and new ones came in exchange. F/E fairbeautiful fairblack maidgirl. They are hard to hear. According to Irina Vladimirovna Arnold, a linguist, grammatical archaisms are the forms of words that are not currently used because of changes in the grammatical structure of the language. In modern English, grammatical archaisms are, for example, the words with the suffix -en moved to -es, horse — horses, however, you can still find the previous form in the words children and oxen. Morphological archaisms are outdated forms of the word, such as:

* singular third person verbs ending in “th” (doth, hath, heareth, etc.)

* abbreviated forms (tis, twas, twill, etc.).

Archaisms used to make a speech of high solemnity, pathetic tone are considered as poetic. Here are some examples: billow, hallowed, fare, aught.

Let us consider in more detail the group of lexical archaisms.

This is a category of outdated vocabulary, resulting from the separation of the dictionary. Lexical archaisms belong to the book vocabulary, in modern language they are interrelated with synonyms.

Lexical archaisms are also divided into various subgroups: lexico-phonetic and word-building.

Word-building archaisms include obsolete words which are occupied the wordsthat are synonymous with the same root, but differ from them by affix, affixes, or by the absence of them. Lexico-phonetic archaisms are archaisms that differ from modern variants of English words only by the presence of additional sounds.

Archaisms and historicisms are often used in works of art, when you need to create a certain color in the image of antiquity. In the texts of historical novels, short stories in order to recreate the historical color of the era. Also, it is necessary to mention the style of business documents. The function of archaisms in this style of speech could be conventionally called a terminological function. Many English laws have not changed in the last 600 years. Naturally, therefore, in the language of English law there is a large number of archaisms. The language of various legal documents, business letters, contracts, agreements, etc., trying to get as close as possible to the language of laws, is replete with archaisms. Archaisms are also used to convey the comic tone of speech, can also perform a satirical function and display the peculiarities of foreign speech.

Being interested in the question of the distribution of words which underwent changes in its composition in the work of English literature of the 14th century, I decided to study the percentage of such words. For the subjects of the study I took the words that have undergone phonetic change which are yellow in the text, changes in their morphemic composition which are green in the text and those that have undergone both phon etic and word-building changes in their composition which are blue. For example, the chapters by Geoffrey Chauser from «The Canterbury Tales» were taken. I have analized 97 lines, chapters from 11 to 14.

bathe— word-building archaisms.

ther — lexico-phonetic archaisms.

compaigne — archaisms that have undergone a double change in their composition.

Chapter 14

445: A good wif was ther of biside bathe,

446: But she was somdel deef, and that was scathe.

447: Of clooth—makyng she hadde swich an haunt,

448: She passed hem of ypres and of gaunt.

449: In al the parisshewif ne was thernoon

450: That to the offrynge biforehiresholde goon;

451: And if ther dide, certeyn so wrooth was she,

452: That she was out of alle charitee.

453: Hir coverchiefs ful fyne weren of ground;

454: I dorste swere they weyeden ten pound

455: That on a sonday weren upon hir heed.

456: Hir hosen weren of fyn scarlet reed,

457: Ful streite yteyd, and shoes ful moyste and newe.

458: Boold was hir face, and fair, and reed of hewe.

459: She was a worthy womman al hir lyve:

460: Housbondes at chirche dore she hadde fyve,

461: Withouten oothercompaignye in youthe, —

462: But therof nedeth nat to speke as nowthe.

463: And thries hadde she been at jerusalem;

464: She hadde passed many a straunge strem;

465: At rome she

hadde

been, and at boloigne,

466: In galice at seint-jame, and at coloigne.

467: She koude muchel of wandrynge by the weye.

468: Gat-tothed was she, soothly for to seye.

469: Upon an amblere esily she sat,

470: Ywympled wel, and on hir heed an hat

471: As brood as is a bokeler or a targe;

472: A foot-mantel aboute hir hipes large,

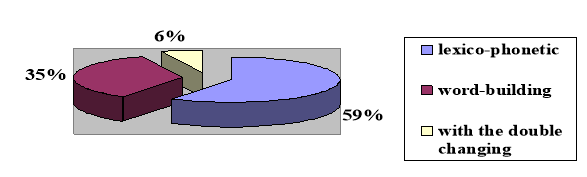

After analyzing the distribution of various types of lexical archaisms, we obtained the following results:

Percentage chart of types of lexical archaisms:

Here are some examples of words which were used by Geoffrey Chaucer in «The Canterbury Tales» in chapters from 11 to 14 but they are obsolete right now.

Table 1

|

An archaism |

A modern word |

Translation |

|

Hadde |

Had |

Имел |

|

Hem |

Them |

Их |

|

Koude |

Could |

Мог |

|

Londoun |

London |

Лондон |

|

Alle |

All |

Все |

|

Olde |

Old |

Старый |

|

Boold |

Bold |

Лысый |

|

Sonday |

Sunday |

Воскресенье |

|

Newe |

New |

Новый |

|

Hir |

Her |

Ее |

|

Compaignye |

Company |

Компания |

Having done the research, we discovered that the most frequently encountered group of archaisms are phonetic archaisms. Geoffrey Chaucer’s work «The Canterbury Tales» contains 59 % of the phonetic archaisms of all that we have reviewed. 35 % is a group of word-building archaisms, and 6 % are archaisms, which have undergone a double change in their composition.

Despite the fact that the work contains a huge number of obsolete words, it is not so difficult to read. This is due to the fact that many words have historically similar roots, so we can freely translate the Old English work in modern English.

References:

- English-Russian dictionary, 2000/ V.K.Muller — M., Diamant, Zolotoi Vek.

- Бабич, Г. Н. LEXICOLOGY: A CURRENT GUIDE.2017/ Г. Н. Бабич — М.: ФЛИНТА: Наука. – URL:https://rucont.ru/efd/244047 (дата обращения 23.02.2019)

- URL: http://yakov.works/libr_min/24_ch/os/er_01.htm ( дата обращения 20.02.2019)

- URL: http://allrefs.net/c57/3qv72/p4/ ( дата обращения 21.02.2019)

- URL: http://textarchive.ru/c-2756206-p5.html ( дата обращения 20.02.2019)

- URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archaism ( дата обращения 22.02.2019)

- URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Canterbury_Tales ( дата обращения 22.02.2019)

- URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geoffrey_Chaucer ( дата обращения 22.02.2019)

Основные термины (генерируются автоматически): URL, CURRENT, LEXICOLOGY, дата, обращение.