The findings discussed in Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children have been cited more than 8,000 times, according to Google Scholar.

Chelsea Beck/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Chelsea Beck/NPR

The findings discussed in Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children have been cited more than 8,000 times, according to Google Scholar.

Chelsea Beck/NPR

Did you know that kids growing up in poverty hear 30 million fewer words by age 3? Chances are, if you’re the type of person who reads a newspaper or listens to NPR, you’ve heard that statistic before.

Since 1992, this finding has, with unusual power, shaped the way educators, parents and policymakers think about educating poor children.

But did you know that the number comes from just one study, begun almost 40 years ago, with just 42 families? That some people argue it contained a built-in racial bias? Or that others, including the authors of a new study that calls itself a «failed replication,» say it’s just wrong?

NPR talked to eight researchers to explore this controversy. All of them say they share the goal of helping poor kids achieve their highest potential in school.

But on the issue of how to define either the problem, or the solution, there are, well, very big gaps.

With all that in mind, here are six things to know about the 30 million word gap.

1. The original study had just 42 families.

During the War on Poverty in the 1960s, Betty Hart, a former preschool teacher, entered graduate school in child psychology at the University of Kansas, working with Todd Risley as her adviser.

The two began their research with preschool students in the low-income Juniper Gardens section of Kansas City, Kan., explains Dale Walker of the University of Kansas, who counts Hart as a colleague and mentor. «They definitely worked out of their personal concern and experience with young children.»

Seeing differences between poor and middle-class children by the age of 3, Hart and Risley decided to look for roots even earlier in children’s lives.

Beginning in 1982, they followed up on birth announcements in the newspaper to recruit families with infants as research subjects.

They eventually chose 42 families at four levels of income and education, from «welfare» to «professional class.» All of the «welfare» families and 7 out of 10 of the «working class» families were black, while 9 out of 10 of the «professional» families were white — this will be important later.

Starting when the babies were 7 to 9 months old, the researchers visited each house for one hour, once a month, for 2 1/2 years. They showed up generally in the late afternoon, with a cassette recorder, a clipboard and a stopwatch and tried to fade into the background. They were there to record the number of words spoken around the children, as well as the quality and types of interaction (for example, a question versus a command), and the growth in words produced by the children themselves.

2. The study has been cited over 8,000 times.

After 1,200 hours of recordings were collected, the real work began. Transcribing and checking each moment, with their elaborate system of coding, took 16 hours for every hour of tape, Dale Walker explains.

Hart and Risley’s study wasn’t published until 1992, while their book, Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children, came out in 1995.

From there, it really caught fire. These findings have been cited more than 8,000 times, according to Google Scholar. The book remains one of its publisher’s bestsellers more than 20 years later. There is a national research network of over 150 scholars aligned with Hart and Risley and focusing on young children’s home environment.

And the impact of this work spread far beyond the ivory tower. «It’s had enormous policy implications,» says Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, a developmental psychologist at Temple University and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Something about that figure, 30 million words, held people’s attention. Not only was it big, it seemed actionable.

Speech — unlike books or housing or health care — is free. If we could somehow get poor parents to speak to their children more, could it make a huge difference in fixing stubborn inequities in society?

The «word gap» drove expanded federal investments in Head Start and Early Head Start. Hart and Risley’s work inspired early intervention programs, including the citywide effort Providence Talks in Rhode Island, the Boston-based Reach Out and Read, and the Clinton Foundation’s Too Small To Fail.

Both researchers are now deceased. But in Kansas City, where it all began, Dale Walker and others work on research and interventions at the Juniper Gardens Children’s Project.

3. Thirty million words is probably an exaggeration. Maybe the gap is 4 million. Maybe it’s even smaller.

That eye-popping figure is one of the reasons the study has been so sticky over time. But newer studies have found very different numbers.

Since Hart and Risley’s study was published, critics have taken issue with how the data was collected and interpreted.

«Their study is commendable in many ways, but they just got it wrong,» says Paul Nation, an expert in vocabulary acquisition at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

Nation primarily takes issue with the idea that you can estimate vocabulary growth from small samples of speech, particularly when the samples don’t contain the same number of words.

He is one of many to have pointed out that the low-income families in their sample may have been intimidated into silence by the presence of a researcher, especially someone of another race. Educated parents, though, might be more likely to show off by talking more when an observer is present.

Modern technology can get around this observer effect. A nonprofit called LENA manufactures a tiny digital recording device that can be worn by children as young as 2 months old. Software then estimates speech and turn-taking.

While not invisible, it’s a lot less intrusive than having a person sitting in the room. Directly inspired by Hart and Risley, LENA is used in school-based and home-based interventions dedicated to closing the word gap in more than 20 states.

Using LENA, scientists published a near-replication of the Hart and Risley study in 2017, only this study had 329 families, nearly 8 times more, and 49,765 hours of recording, from children 2 months to 4 years.

Their conclusion? The «word gap» between high-income and low-income groups was about 4 million by the time the children turned 4, not 30 million by age 3. Only if you compared the most talkative 2 percent with quietest 2 percent of families did you get a gap nearly as wide as Hart and Risley’s, says LENA’s senior director of research, Jill Gilkerson.

Another just-published study calls itself a «failed replication» of Hart and Risley.

The researchers analyzed field recordings from five different poor and working-class communities. They found that the amount of speech children heard varied from one place to another.

The lowest-income children recorded in South Baltimore heard 1.7 times as many words per hour as did Hart and Risley’s «welfare» group. And in the «Black Belt,» an area in rural Alabama, poor children heard three times as many words as Hart and Risley’s «welfare» group.

The wide variation «unsettles the notion that income alone determines how many words children hear,» lead author Douglas Sperry tells NPR.

4. Some people take issue with the whole idea of a «gap»

Sperry and his co-authors fall into a camp that criticizes the «word gap» concept as racially and culturally loaded in a way that ultimately hurts the children whom early intervention programs ostensibly trying to help.

«To look at income alone obscures real questions about the cultural mismatch between children of color and mainstream European children and their teachers as they enter schools,» says Sperry. In other words, it’s not necessarily that poor children aren’t ready for school; it’s that schools and teachers are not ready for these children.

Marjorie Faulstich Orellana, a professor of education at the University of California, Los Angeles, has called attention to the «word wealth» experienced by children who grow up learning a different language or even a different dialect than the dominant standard English spoken in school. This would describe not only recent immigrants, but also anyone whose background isn’t white, educated and middle or upper class. When they get to school, they must learn to «code switch» between two ways of speaking.

She doesn’t disagree that «there’s variation in how much adults speak to children,» but, she tells NPR, there shouldn’t necessarily be a value judgment placed on that.

«Should adults direct lots of questions to children in ways that prepare them to answer questions in school?» she asks, calling that a «middle-class, mostly white practice.»

«There are other values, like using language to entertain or connect, rather than just have children perform their knowledge. How do we honor different families rather than have families change their values to align with school?»

Similarly, Sofia Bahena, an education professor at the University of Texas, San Antonio, says talking about «word gaps,» like «achievement gaps,» is an example of what she calls deficit thinking.

«We can talk about differences without resorting to deficit language by being mindful and respectful of those we are speaking or researching about,» she explains. «We can shift the question from ‘how can we fix these students?’ to ‘how can we best serve them?’ It doesn’t mean we don’t speak hard truths. But it does mean we try to ask more critical questions to have a deeper understanding of the issues.»

Jennifer Keys Adair at the University of Texas, Austin published a study last year of how the «word gap» rubber is meeting the road of schools.

She and her co-authors spoke with nearly 200 superintendents, administrators, teachers, parents and young children in mostly Spanish-speaking immigrant communities. The educators expressed the belief that the children in grades pre-K through third in this community could not handle learner-centered, project-based, hands-on learning because their vocabulary was too limited. And, the children in the study themselves echoed the belief that they needed to sit quietly and listen in order to learn.

Adair says the «word gap» has become a kind of code word. «We can say ‘vocabulary.’ We’re not going to say ‘poor’ and we’re not going to use ‘race,’ but it’s still a marker.»

5. The underlying desire to help kids is still pretty compelling, though

Walker says that Hart and Risley were happy to engage with their critics. «They valued that input and the give and take.» But, she says, they were sometimes «dismayed» at misinterpretations of their research, such as if people took ideas about the importance of an early start as justification for not trying to improve student outcomes later on in school.

Some boosters agree with critics that the «word gap» may need a reframing.

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, with her longtime collaborator Roberta Michnick Golinkoff and other researchers, wrote a scholarly critique of the Sperry study for the Brookings Institution.

«I am worried,» Hirsh-Pasek tells NPR, that downplaying the word gap will have «dangerous» consequences. «Whenever you send out a message that ‘Hey, this doesn’t matter,’ the policymakers are listening and say, ‘Hey, that’s great, we can divert the money.’ «

Sperry’s measures included «bystander talk» by multiple people in the room, including older siblings and other relatives. So did the LENA study. Hirsh-Pasek says the psychological research is clear that it’s the «dance» of interaction between caregiver and child that is crucial to learning speech.

While this point is fairly settled among developmental psychologists, anthropologists may dissent, says Douglas Sperry. In some cultures, such as the Mayans in Central America, addressing young children directly is uncommon, yet people still learn to talk, he notes.

Hirsh-Pasek does agree with the critics that framing the issue as a deficit is wrong. «I’m so sorry that the 30 million word gap was framed as a gap,» she says. «I like to talk about it as building a foundation rather than reducing a gap.»

But, she adds, the sheer volume of conversation directed at children, not just spoken in their presence, is fundamental to language learning and later success in school. All the cultural variation in the world «doesn’t negate the fact that when you look at the averages, there is a problem here.»

And what’s most important, says Hirsh-Pasek, is that interventions inspired by Hart and Risley are nudging parents in the right direction. «We have made changes and movement in kids, in whole communities.»

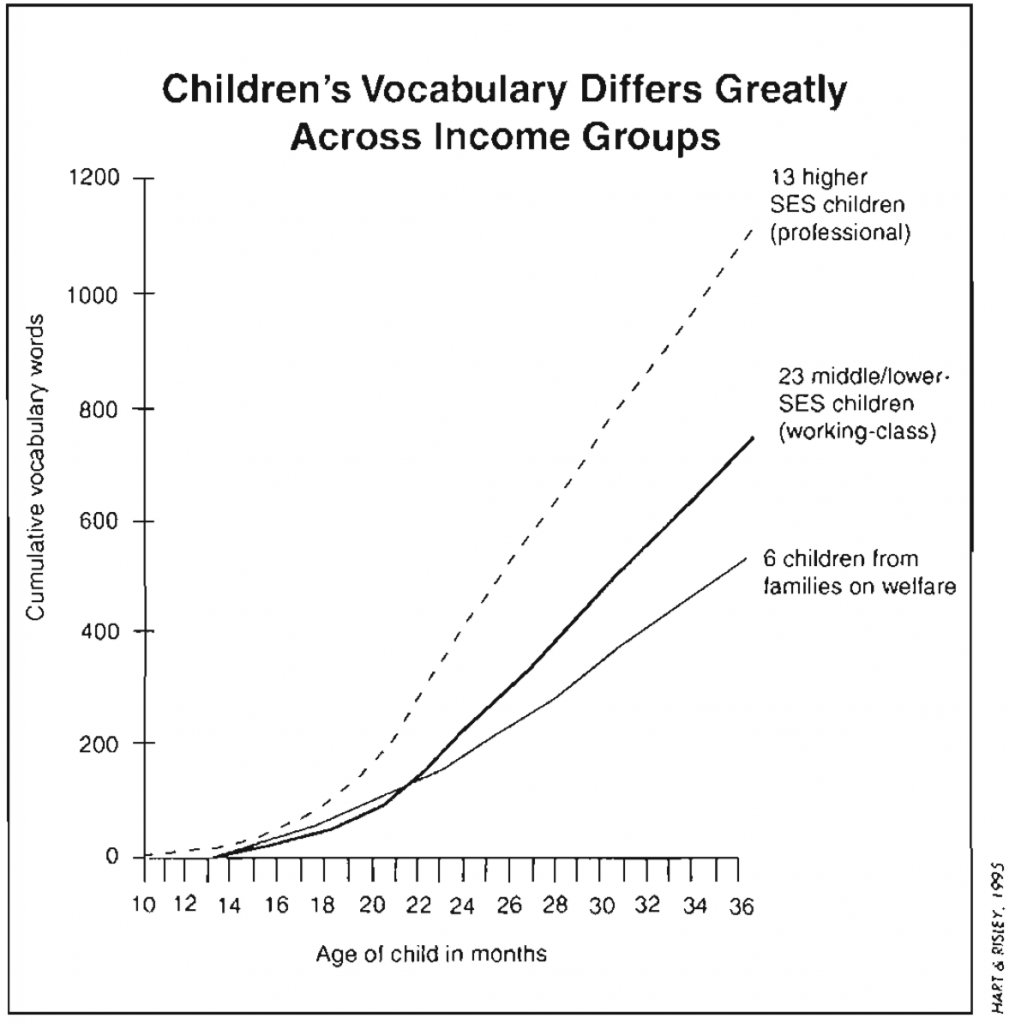

The term 30-million-word gap (often shortened to just word gap) was originally coined by Betty Hart and Todd R. Risley in their book Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children,[1] and subsequently reprinted in the article «The Early Catastrophe: The 30 Million Word Gap by Age 3».[2] In their study of 42 Midwestern families, Hart and Risley physically recorded an hour’s worth of language in each home once a month over 2½ years. Families were classified by socioeconomic status (SES) into «high» (professional), «middle/low» (working class) and «welfare» SES. They found that the average child in a professional family hears 2,153 words per waking hour, the average child in a working-class family hears 1,251 words per hour, and an average child in a welfare family only 616 words per hour. Extrapolating, they stated that, «in four years, an average child in a professional family would accumulate experience with almost 45 million words, an average child in a working-class family 26 million words, and an average child in a welfare family 13 million words.»[2]

The authors found a correlation between word exposure and the rate of vocabulary acquisition in the subject children. The recordings showed that high-SES toddlers spoke approximately two new words a day between their second and third birthdays, middle-/low-SES children one word per day, and welfare SES children 0.5 words per day. Spoken words are a measure of productive vocabulary. It is thought that during children’s vocabulary development the productive vocabulary mirrors their underlying receptive vocabulary growth.

The authors and subsequent researchers have posited that the word gap—or certainly the differing rates of vocabulary acquisition—partially explains the achievement gap in the United States, the persistent disparity in educational performance among subgroups of U.S. students, especially subgroups defined by socioeconomic status and race.[3]

History of language gap research[edit]

Before Hart & Risley[edit]

Prior to the 30-million-word-gap study, extensive research had noted strong institutional variation in student success on standardized tests. The initial attention to achievement gap started with a 1966 publication from the U.S. Department of Education titled «Equality of Educational Opportunity.» The publication begins the onset of achievement gap by acknowledging that there is a great disparity within educational outcomes as a result of inequitable institutions, especially those that were not seen as part of the purview of schools such as cultural, socioeconomic, and linguistic realities of students at home. The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) had further been used to census information that various studies used to show achievement gaps across a number of demographics. The idea of equity in education had also given rise to similar gap discourse around the world.

Hart & Risley’s contribution[edit]

Hart and Risley (2003) spent 2½ years observing 42 families for an hour each month to learn what typical home life was like for 1- and 2-year-old children. The families were grouped into 4 variables, upper SES, middle SES, lower SES and just a few that were on welfare. The middle- and low-SES families were grouped in the final analysis. They found that by age 3 children in welfare families had a vocabulary of 525 words where children in upper-SES families had vocabulary of 1,116 words. They also found that the children in upper-class families were learning vocabulary at a faster rate. The researchers suggested the reason for this difference is because the welfare children heard on average 616 words per hour where professional-family children heard on average 2,153 words per hour. Thus, proposing the 30-million-word gap. The achievement gap is explained as a result of the language gap, in that because children are lacking in their vocabulary and literary skills, they will not be as successful in academics. Hart and Risley argue this is an indispensable societal concern because it sets the child at a disadvantage for not being exposed to more vocabulary skills at a young age.

Socioeconomic status studies[edit]

Fernald, Marchman, and Weisleder (2013) conducted a study with 48 children from diverse backgrounds ages 18–24 months old. The families were divided into low SES (socioeconomic status) and high SES.[4] Their first goal was to track developmental changes in processing efficiency in relation to vocabulary learning. Their second goal was to examine difference in aspects of early language development in relation to their SES. Their results showed that children at the same age from the lower-class families had lower vocabulary scores when compared to children in higher class families. Fernald et al. (2013) also found that by 18 months old language processing and vocabulary disparities were already evident, and by 24 months old there was a 6-month gap between the SES groups in processing skills critical to language development.[4] Fernald et al. found fast reaction time as a child can translate into reaction time as an adult. Adults who have high reaction time tend to have better memories, reasoning abilities, language skills and are better able to learn new skills (fluid intelligence). Having better processing speed means having a stronger working memory, and a stronger working memory leads to a better cognitive competence. The authors express the importance of vocabulary knowledge because it sets a foundation for later literacy and language proficiency in preschool and that is predictive of academic success. Implications of long term developmental trajectories. Thus, the issue of the language gap and achievement gap are prevalent in our youth, which can be resolved by teaching families how to work and speak with their children.

Educational system studies[edit]

Sperry, Sperry, and Miller (2018) replicated Hart and Risley’s study and found that the number of word gaps varied within the same backgrounds of socio-economic status.[5] A longitudinal study observed families with their children in their homes and the researchers spoke to the participants as if they were a family friend. They used similar social classes as HR for comparison. Middle class, working class, lower class, poor «welfare» group. During the visit, three analyses were made and transcribed for research. The first was how many words the primary caregiver spoke to the child. The second was that the words spoken by all caregivers to the child showed social class alone did not determine either the composition of households or consequently the amount of a speech a child heard. Lastly, all ambient speech, like language addressed to other individuals but overheard by language learning children was considered. In the poor community sample when you took into consideration the ambient speech, or the words that primary caregivers said to extended family, the number of words a child hears increased by 54%, in the working class by 210%. This study was the first attempt to replicate Hart and Risley and their findings did not support the previous claims.[5] Given the variation within communities was greater than when simply comparing socioeconomic statuses.[5]

Garcia and Otheguy (2016) were interested in the origins and validity of the Language Gap, and how the preconceptions of it impact bilingual and bidialectical children, specifically from Latino and Black backgrounds.[6] They focused more so on how people talk about and understand language as a whole, especially within the education system. Their argument claims language is a semiotic process that involves sound, touch, and gestures and should be seen as a translanguaging-internalist perspective. She offers historical context to give insight to the creation of the Language Gap and the biases it may hold. They suggest it began when Brown vs The Board of Education (1954) and the Civil Rights Act (1964) made it illegal to judge based on one’s color or race; thus, exclusions needed to be made based on another trait. They build on Flores and Rosas’ (2017) idea of raciolinguistics that suggests a new way to separate whites and non-whites.[7] They continue to give historical context on the Achievement Gap in that it was a result of the No Child Left Behind Act (2001), despite its good intentions, it compared every race and background on a standardized test written in a White monolingual way.[6] Given the educational system functions on the dominant groups of society (i.e. white, Standardized English, middle-upper class), it ignores the linguistic and cultural practices of minorities. The theory here is that it is not that families of differing backgrounds are not adequate in teaching their children how to speak, but teach them a different linguistic culture at home than the one taught in schools.

Similarly, Johnson (2015) draws on from Faltis (2006) socialization mismatch hypothesis that the culture of the schooling system that is based around middle to upper class, White, Standardized English principles do not match the language socialization of backgrounds that may not fit into these categories.[8] He argues the Language Gap was not a result of vocabulary or literary deficiency in a child, but rather not understanding the language socialization of different cultural backgrounds. He drew from a previous linguistic anthropologist Hymes (1972) term of «communicative competence» in that social expectations within a speech community shape the member’s use of language.[9] Thus, diverse backgrounds in language have a different set of expectations that a member conforms to. As language differs, so does the developmental process.[10] Johnson (2015) argues the Language Gap is not fair because it does not consider the various ways children use words and create meaning. Therefore, it is not the parents at fault leading their children to fall behind, but the school’s fault for not accommodating to children’s backgrounds. Thus, the Language Gap is not a result of a child’s capabilities to understand, but a result of how a linear function of language ignores the needs of the various ways to make meaning.

Criticisms[edit]

Hart and Risley’s research has been criticised by scholars. Paul Nation criticises the methodology,[11] noting that comparing the tokens (words produced) and number of types (number of different words) in unequal samples is not comparing vocabulary sizes. This is to say that the high socio-economic status samples naturally had a greater number of word types due to the greater number of tokens, because Hart and Risley extrapolated from tokens to an assumed greater number of types, but did not individually assess the number of types. The vocabulary sizes were cumulative, when it is possible that some new words produced were words that had been learnt in a previous month. In fact, Hart and Risley found no major differences in the quality of language produced between the different socio-economic groups.

Other critics theorize that the language and achievement gaps are not a result of the amount of words a child is exposed to, but rather alternative theories suggest it could derive from the disconnect of linguistic practices between home and school. Thus, judging academic success and linguistic capabilities from socioeconomic status may ignore bigger societal issues. The ongoing word gap discourse can be seen as a modern movement in educational discussion.

A recent replication of Hart and Risley’s study with more participants has found that the «word gap» may be closer to 4 million words,[12] not the oft-cited 30 million words previously proposed.

Hart and Risley’s research has also been criticised for its racial bias, with the majority of the welfare families and working-class families being African American.[citation needed]

Implications[edit]

[edit]

There are possible social implications to Hart and Risley’s theories of the issue of the Language Gap in society. The first possible implication is that this Language Gap is affecting youth’s success because they are not exposed to the same amount of vocabulary and literary skill as other kids from middle-upper classes.[2] Hart and Risely suggest that possible solutions include interventions on how to improve vocab and literary skills for caregivers in low SES. However, the second possible implication of this theory is that it ignores the fact that language and culture are taught differently. In stating other backgrounds cannot be as successful as the dominant groups in society, It reinstates the homogeneity of language, in that it proposes one «true» way of speaking.[6]

Garcia and Otheguy (2016) implies the Language and Achievement Gap derive from racist ideals that reinforce the idea that some cultures are seen as «disadvantaged». To place the blame on different backgrounds is to invalidate their way to make meaning just because they have different cultures. Thus, to not consider the responsibility of the schooling system is to promote the homogeneity of Standardized English and this notion that anyone who does not speak or understand it is inferior and prone to future failure. Garcia argues it delegitimizes backgrounds of families and their linguistic and cultural practices because it is not seen to be «successful» in the eyes of the education system.[6]

Political implications[edit]

Sperry, Sperry and Miller discussed some of the consequences of the original Hart and Risley (2003) article. The 30-million-word gap has received widespread media attention. In 2013 Bloomberg Philanthropies mayors challenge awarded providence Rhode Island its grand prize to «providence talks»—a project proposed to teach poor parents how to speak to their children with the aid of the LENA Device. The Clinton foundations «Too Small to Fail» initiative which hosted the White House Word Gap event in 2014, resulted in the US department of Health and Human services funding remedial efforts to address the Word Gap.[5]

In addition, Georgia has a policy «Talk with Me Baby» that is a public action strategy aimed at increasing the number of words children are exposed to in early childhood. «Talk With Me Baby» is a program that provides professional development of nurses, who will then coach new parents how they should talk to their children. This program is funded by Greater United Way of Atlanta.[13]

The University of Chicago, School of Medicine’s Thirty Million Words Initiative provides intervention for caregivers and teaches to show them how to optimize their talk with their kids. This program is funded by the PNC Foundation.[13]

Gap discourse[edit]

The Word Gap theory can be seen as part of a larger development in modern educational reform and movement: the Achievement Gap discourse. It is widely accepted and noted by scholars that ideas around individual outcome in schools varies based on various demographics. Explaining variations in achievement in schools across levels of demographics that may result in a gap in student achievement has become the primary problems public schools have to address. The Discourse is based on evidence and assumptions of why primarily poor students of color do not perform at the same levels as their more affluent White and certain Asian group counterparts—it creates language to how schools and communities can be organized more optimally to help students and schools produce more equitable and successful outcomes. The Achievement Gap also addresses a gender gap achievement, and standardized test score gaps broadly across countries, notably with standardized examinations on STEM subjects. The Discourse can also be seen as a turning away from traditional explanations of performance in school as individualistic, to the creation of cultural framework understanding to help explain what conventions hinder and produce successful students. Under performing, adequate yearly progress (AYP), highly qualified, below basic, and proficient are some terms used to mark good and bad aspects of schools, their teachers, and their students which in turn reifies the Achievement Gap theory. As a broader Discourse, it is an idea which is multimodally shared and accepted as common belief between parents, policy makers, teachers and students through various means according to James Paul Gee’s idea of Discourse in socio-linguistic analysis.[14]

The effects of the Achievement Gap Discourse cause several cultural phenomena—»cultural gate-keeping,» in which policy makers and education reformers decide and label students as more or less capable and worthy than others. Schools might be called under-performing, which can further affect the policy and financing prescribed by their districts, or even higher authorities.[14]

Using metric standards to understand the cause in Achievement Gap as a result of ineffective cultural practices also tends to place blame on the families unless there is ample socio-linguistic inquiry to individual family circumstance, which still often creates a Discourse against deemed underachieving students’ culture.

The Achievement Gap Discourse initiated with two primary modes in American educational studies: Achievement Gap among races, and gap among socioeconomic status (SES). The gap Discourse does not typically extend across generations or other forms of demographics that have been studied, and further study of Achievement Gap among different dimensions faces the initial stigmatization as a result of the gap Discourse in various studies around the turn of the 21st century, pin-headed by the 30-million-word gap. Among critics are many linguists, anthropologists, and social discipline specialists, as well as organizations such as the Linguistic Society of America.[10]

The achievement gap became an especially strong interest for study in the turn of the century, and the early 2000s when a plethora of studies looked at factors such as standardized test scores, presence in class, GPA, enrollment, and dropout rates in secondary and post-secondary education. The problem came in the analyses of the studies which were criticized for looking at race and socioeconomic explanations to explain educational outcome without taking into account others such as S. J. Lee, 2005, Pang, Kiang, & Pak, 2004, and Rothstein 2004 which provided broad postulations as to why race and SES accounted for varied success.[15][16][17] President George W. Bush’s administration’s No Child Left Behind rhetoric of 2001 and 2002 left researchers limited to the type of research they could conduct for educational equity due to a need to appease policy makers among educational stakeholders. According to Roderick L Carey, Word Gap researcher, the NCLB «mandated objective and quantitative ‘scientifically based’ research, which left little room for qualitative research agendas that unpack contextual factors that add nuance to the understandings of how high-stakes accountability is felt and lived by students, teachers, and their families.»[14] The rhetoric also posed ideas that placed responsibility of achievement in institutions on their most proximal function oriented members, shifting responsibility to achieve positive outcomes on high-stakes standardized tests nearly entirely on teachers and schools, whilst the difference in achievement was largely believed to be due to factors outside of the classroom. Various studies culminated to suggest general and vague underlying problems within specific communities which caused deficit in learning outcomes under this context.

Among these studies, Hart and Risley stumbled upon the idea of word gap when working with youth who used cochlear implants, to form their idea: they hypothesized exposure to spoken word might explain an achievement gap in standardized test scores, then used standardized testing data on language as well as an in depth study to conclude their 30-million-word-gap publication.

Additional information[edit]

Word Gap internationally[edit]

The Oxford Word Gap is used to describe the word gap found between races and socioeconomic classes in the United Kingdom.[14] The report study «Why Closing the Word Gap Matters: Oxford Language Report» details out statistics collected in primary and secondary schools in the United Kingdom, along the same ideas as the American Word Gap idea, citing Hart and Risley (2003) in the report. It was published in 2018, so all of its implications are yet to be seen.

A great number of states have paid attention to Achievement Gap across hundreds of criteria including demographics, access to language and economic resources and race around the world: notably in the United Kingdom, France, South Africa as named in one comparative analysis.[18] UNESCO has held strongly in its principles the importance on aspects of educational equity, and other educational movements similar to that of the United States Word Gap are numerous throughout Europe and some other members of UNESCO.[19] Europe also has its own varied standards on the ideas of multilingual competence per state, which stress the apprehension and exposure to secondary language vocabulary in students of all ages.

Other word gaps[edit]

The word gap has largely been defined to mean the idea of the observed gap between the spoken and read language in the specific context of American education reform in the context of Hart and Risley; however, other proposed ideas or active research have used it to describe differences in access to language varieties experienced in public settings, such as signage in Orellana, 2017’s Another Type of Word Gap, as well as other linguistic resources such as using media for language acquisition.[20]

References[edit]

- ^ Hart, Betty; Risley, Todd R. (1995). Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children. P.H. Brookes. ISBN 9781557661975.

- ^ a b c Hart, Betty; Risley, Todd (2003). «The early catastrophe: The 30 million word gap by age 3» (PDF). American Educator: 4–9. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ Strauss, Valerie (16 February 2015). «The famous ‘word gap’ doesn’t hurt only the young. It affects many educators, too». Washington Post. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ a b Fernald, Anne; Marchman, Virginia A; Weisleder, Adriana (2013). «SES differences in language processing skill and vocabulary are evident at 18 months». Developmental Science. 16 (2): 234–48. doi:10.1111/desc.12019. PMC 3582035. PMID 23432833.

- ^ a b c d Sperry, Douglas E; Sperry, Linda L; Miller, Peggy J (2018). «Reexamining the Verbal Environments of Children from Different Socioeconomic Backgrounds». Child Development. 90 (4): 1303–1318. doi:10.1111/cdev.13072. PMID 29707767.

- ^ a b c d García, Ofelia; Otheguy, Ricardo (2016). «Interrogating the Language Gap of Young Bilingual and Bidialectal Students». International Multilingual Research Journal. 11 (1): 52–65. doi:10.1080/19313152.2016.1258190. S2CID 151553999.

- ^ Flores, Nelson; Rosa, Jonathan (2015). «Undoing Appropriateness: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and Language Diversity in Education». Harvard Educational Review. 85 (2): 149–71. doi:10.17763/0017-8055.85.2.149.

- ^ Faltis, C.F. (2005), Teaching English Language Learners in Elementary School Communities , Pearson, London.

- ^ Hymes, D. (1972), “On communicative competence”, in Pride, J.B. and Holmes, J. (Eds),Sociolinguistics , Penguin, London, pp. 269-285.

- ^ a b Johnson, Eric J (2015). «Debunking the ‘language gap’«. Journal for Multicultural Education. 9 (1): 42–50. doi:10.1108/jme-12-2014-0044.

- ^ Nation, I.S.P. «A brief critique of Hart, B. & Risley, T. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing» (PDF).

- ^ Gilkerson, Jill; Richards, Jeffrey A.; Warren, Steven F.; Montgomery, Judith K.; Greenwood, Charles R.; Kimbrough Oller, D.; Hansen, John H. L.; Paul, Terrance D. (2017). «Mapping the Early Language Environment Using All-Day Recordings and Automated Analysis». American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 26 (2): 248–265. doi:10.1044/2016_ajslp-15-0169. PMC 6195063. PMID 28418456.

- ^ a b Shankar, M. (2014) Empowering our children by bridging the word gap. The White House President Barack Obama retrieved from: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2014/06/25/empowering-our-children-bridging-word-gap

- ^ a b c d Carey, Roderick L (2013). «A Cultural Analysis of the Achievement Gap Discourse». Urban Education. 49 (4): 440–68. doi:10.1177/0042085913507459. S2CID 144133493.

- ^ Pang, V. O., Kiang, P. N., & Pak, Y. K. (2004). Asian Pacific American students: Challenging a biased educational system. In J. A. Banks & C. A. M. Banks (Eds.), Handbook of research on multicultural education (2nd ed., pp. 542-563). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- ^ Perry, T. (2003). Up from the parched earth: Toward a theory of African American achievement. In T. Perry, C. Steele, & A. G. Hilliard III (Eds.), Young, gifted and Black: Promoting high achievement among African-American students (pp. 1-108). Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- ^ Lee, S. J. (2005). Up against whiteness: Race, school and immigrant youth. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- ^ Fulcher, Taylor J. (2015). «A Comparative Analysis of the Racial and Class Achievement Gap in Schooling in the United States, France, and South Africa». Senior Honors Projects, 2010-2019 (Thesis). Senior Honors Projects. 108.[page needed]

- ^ May, Stephen (2014). «Language rights and language policy: Addressing the gap(s) between principles and practices». Current Issues in Language Planning. 16 (4): 355–9. doi:10.1080/14664208.2014.979649.

- ^ Orellana, Marjorie Faulstich; Education, ContributorProfessor of; UCLA (2016-05-19). «A Different Kind of Word Gap». HuffPost. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

By Lyndsey Gresehover

As an English/Language Arts and Reading teacher and blogger for almost two decades, the word gap is a fretful phrase that I hear all too often in education. But the real question is … does it really exist?

What is the word gap?

This idea came from a study done in the 1990s by two psychologists, Betty Hart and Todd Risley, where language data was collected on 42 families of low, middle, and upper-socioeconomic levels. The study arguably showed that there was a 30 million word gap between upper- and lower-class families. According to the study, this meant upper-class families spent more time speaking and reading to their children than lower-class families.

There have been other similar studies that have taken place since then that show the word gap not to be as much as 30 million words. However, there is also a more recent study which was shared in the journal Child Development that failed to replicate what Hart and Risley determined. This investigation found that there was not a correlation between socioeconomic level and the amount of words a child hears.

What is the problem with the word gap?

There are real differences in outcomes between students of higher SES and lower SES, the latter of which is very often connected to race. The challenge, though, is that a phrase like word gap—and the language of achievement gap more generally—is that, to many, it implies that poorer students of color have a deficit of ability and potential compared to their white or more well-to-do peers. Gap language overlooks the fact that many of the differences in academic success are due to systemic racism, inequality, and a lack of opportunity.

How should we think about the word gap now?

It’s important to take into consideration both sides of this argument, but it’s more important to address the issue at hand. As educators, we have to keep in mind that there is quite a bit of competition when it comes to a child choosing between reading, and for example, watching Youtube. In the 21st century, kids are used to having instant gratification due to all of the electronics and technology that they have access to. If they aren’t getting this rather quickly when they start reading, they tend to put the book down and move on. This is where teachers come in to play.

Research shows that reading aloud with kids helps to expand their vocabulary (Reading Rockets). In my own experience as a teacher and a mother, I have consistently seen students use words that they have heard me read to them when reading together in class. It’s necessary to recognize that students bring in different levels of knowledge that we must build on so that all students benefit from literacy and reading in general. Oral reading can help children to hear the context in which the words were said and therefore allow them to reiterate this in their own conversations.

Tips and activities to inspire kids to read more

If we want our students to read more, we have to find books that not only are on our students’ reading level, but also are of interest to them. Although it can be tough for teachers, particularly at the secondary level when you may have well over 100 kids, it’s imperative that we get to know our students. Are they involved in any extracurricular activities? Do they play sports? What kind of music do they like? Having a strong understanding of their likes and dislikes will be a great way to assist students in finding books that they will actually want to read.

One way I get to know my students is by having them complete a student survey during the first week of school. The survey not only asks questions about their likes/dislikes and what subjects they do well in, but it also asks about their extracurricular activities and how much time they spend doing these activities. I also include questions asking if they have internet access at home, as well as how comfortable they are sending emails, attaching documents in emails, etc. This gives me a broader picture of the student, in general.

As teachers, we have to market reading in a way that will make students want to do it. One way this has been done in my classroom is to have a weekly contest. Students who finish a book and pass an AR (Accelerated Reader) test, add the book to their reading list. The student who reads the most from each class will be announced on the school’s newscast. For those that don’t have a school reading assessment program, students can still keep track of the books they read on a reading log. To show their understanding of the material, have students pick a couple activities off of a choice board to complete.

Which brings us to a couple other reading comprehension activities that are engaging for students:

- Choice boards: Giving students options is always a plus in their opinions. That gives them some control, and we all know they love being in charge! Here’s an example of one that I have used in my classroom.

- Literature circles: These are interactive and include a variety of important reading standards. It makes reading more “social.” Here’s how I run them in my classroom.

- Escape rooms: Have students complete an escape room based on a few of the main areas addressed in the book they read. I make digital escape rooms because they’re free and take less prep. A digital escape can literally be created in no time at all. See how here.

- Let students be the teacher: Allow them to teach a lesson on what they have learned in their reading. Edpuzzle is a great tool that allows students to create lessons that incorporate videos, questions, and even their own voice.

I surveyed a variety of students and asked what makes them want to read. Here are some of their responses:

- Don’t pressure me to read. Let me enjoy doing it without constantly feeling like I HAVE to.

- I like to find books that aren’t about anything stressful. This is why I like fantasy books because they aren’t real. They take you to another place.

- I like to read books that relate to what I want to do in life.

It’s interesting to get students’ opinions on this topic. It was pretty impressive to see what their thoughts were. I used their feedback to work with our school librarian on finding books based on the interests they shared. A lot of my students are currently into dystopian literature, so I try to have a variety of this genre in our classroom library. Some of their current favorites are Among the Hidden series by Margaret Peterson Haddix, as well as the Divergent series by Veronica Roth.

Fantasy is another popular genre, so I try to have access to the Legend series by Marie Lu and the Percy Jackson series by Rick Riordan. Five Feet Apart by Rachel Lippincott, On the Come Up by Angie Thomas, and The Sun is also a Star by Nicola Yoon are additional young adult novels that were student favorites this year. Of course, my personal favorites that happen to be historical fiction are Number the Stars by Lois Lowry and Refugee by Alan Gratz.

Whether you agree or disagree with the word gap, our focus has to be on what’s best for our students: reading in general, word gap or not.

As educators, we must attempt to meet students where they are. Get to know them, and then determine what the next steps should be. Depending on the age/grade level of students, we have to promote reading in a way that will capture their interests and hopefully turn reading into something they want to do, rather than something they feel like they have to do.

Lyndsey Gresehover is a middle school ELA teacher and blogger at Lit with Lyns. Her Instagram account is @litwithlyns.

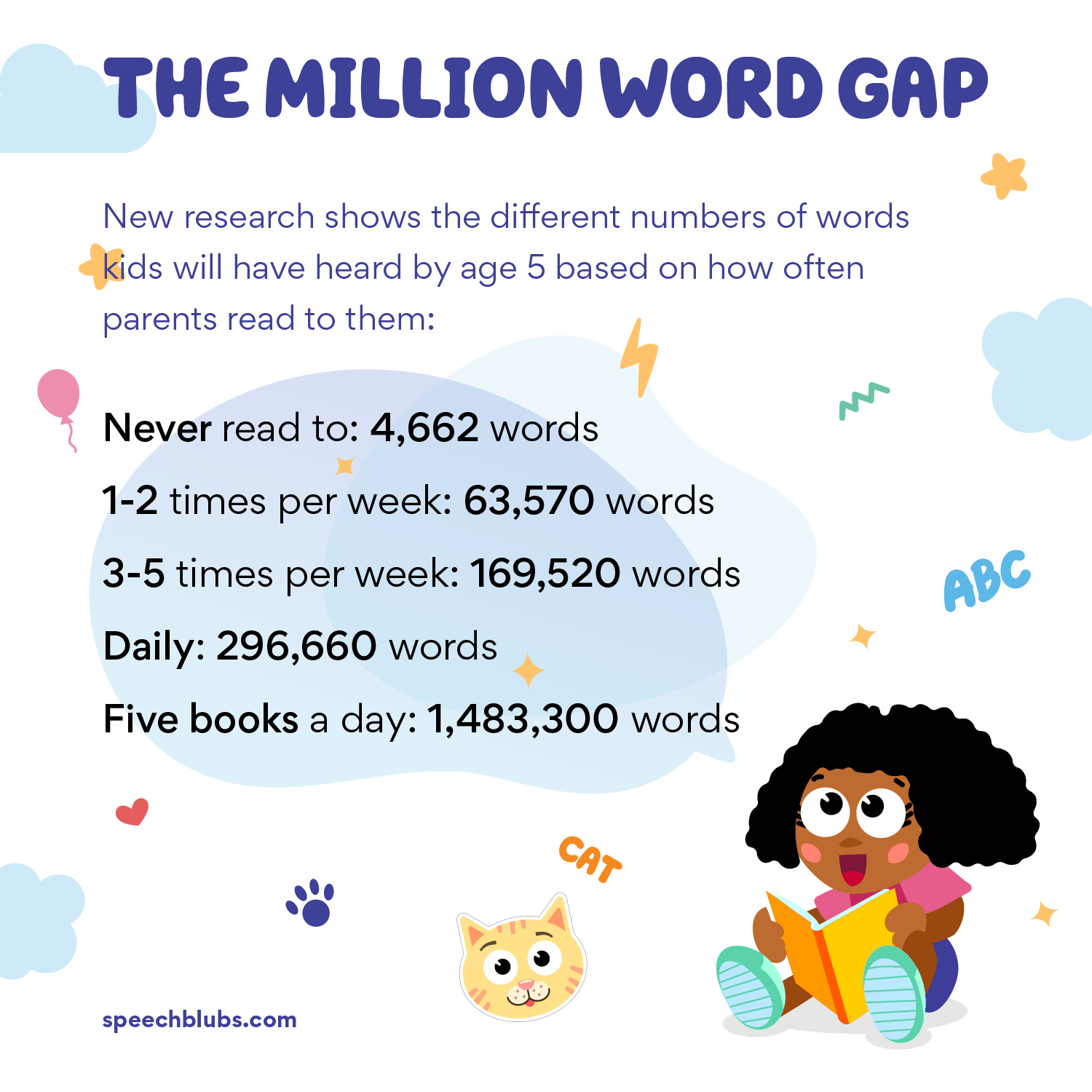

Young children whose parents read them five books a day enter kindergarten having heard about 1.4 million more words than kids who were never read to, a new study found.

This “million word gap” could be one key in explaining differences in vocabulary and reading development, said Jessica Logan, lead author of the study and assistant professor of educational studies at The Ohio State University.

Even kids who are read only one book a day will hear about 290,000 more words by age 5 than those who don’t regularly read books with a parent or caregiver.

“Kids who hear more vocabulary words are going to be better prepared to see those words in print when they enter school,” said Logan, a member of Ohio State’s Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy.

The study appears online in the Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics and will be published in a future print edition.

Logan said the idea for this research came from one of her earlier studies, which found that about one-fourth of children in a national sample were never read to and another fourth were seldom read to (once or twice weekly).

“The fact that we had so many parents who said they never or seldom read to their kids was pretty shocking to us. We wanted to figure out what that might mean for their kids,” Logan said.

The researchers collaborated with the Columbus Metropolitan Library, which identified the 100 most circulated books for both board books (targeting infants and toddlers) and picture books (targeting preschoolers).

Logan and her colleagues randomly selected 30 books from both lists and counted how many words were in each book. They found that board books contained an average of 140 words, while picture books contained an average of 228 words.

With that information, the researchers calculated how many words a child would hear from birth through his or her 5th birthday at different levels of reading. They assumed that kids would be read board books through their 3rd birthday and picture books the next two years, and that every reading session (except for one category) would include one book.

They also assumed that parents who reported never reading to their kids actually read one book to their children every other month.

Based on these calculations, here’s how many words kids would have heard by the time they were 5 years old: Never read to, 4,662 words; 1-2 times per week, 63,570 words; 3-5 times per week, 169,520 words; daily, 296,660 words; and five books a day, 1,483,300 words.

“The word gap of more than 1 million words between children raised in a literacy-rich environment and those who were never read to is striking,” Logan said.

The word gap examined in this research isn’t the only type kids may face.

A controversial 1992 study suggested that children growing up in poverty hear about 30 million fewer words in conversation by age 3 than those from more privileged backgrounds. Other studies since then suggest this 30 million word gap may be much smaller or even non-existent, Logan said.

The vocabulary word gap in this study is different from the conversational word gap and may have different implications for children, she said.

“This isn’t about everyday communication. The words kids hear in books are going to be much more complex, difficult words than they hear just talking to their parents and others in the home,” she said.

For instance, a children’s book may be about penguins in Antarctica – introducing words and concepts that are unlikely to come up in everyday conversation.

“The words kids hear from books may have special importance in learning to read,” she said.

Logan said the million word gap found in this study is likely to be conservative. Parents will often talk about the book they’re reading with their children or add elements if they have read the story many times.

This “extra-textual” talk will reinforce new vocabulary words that kids are hearing and may introduce even more words.

The results of this study highlight the importance of reading to children.

“Exposure to vocabulary is good for all kids. Parents can get access to books that are appropriate for their children at the local library,” Logan said.

Logan’s co-authors on the study were Laura Justice, professor of educational studies and director of the Crane Center at Ohio State; Leydi Johana Chaparro-Moreno, graduate student in educational studies at Ohio State; and Melike Yumuş of Başkent University in Turkey.

Feb 10, 2022 A million words. That is a lot of vocabulary. That is how many fewer words children will hear by kindergarten if they are not exposed to books.

The benefits of reading to kids are fairly well known, but the importance of reading to them can be understood with the following statistic:

Young children whose parents read them five books a day enter kindergarten having heard about 1.4 million more words than kids whose parents never read to them.

Ohio State’s Crane Center for Early Childhood Research

The difference in expressive and receptive vocabulary skills in young children easily explain this million-word gap. It also contributes to kids’ reading difficulties and poor vocabulary use.

`

`

So what if your child just doesn’t want to read five books a day? The study further states that “even kids who are only read one book a day will hear about 290,000 more words by age 5 than those who don’t regularly read books with a parent or caregiver.” This means that reading only one book a day makes a huge difference in your child’s educational journey.

It makes sense that the more words that children see before entering kindergarten, the higher the success rate of reading and writing skills. This happens when they have prior knowledge of the words, and it’s not the first time they are being introduced to them. The more you expose your children to and explain concepts, the easier they are to understand and to place into their long-term memory.

So, How Many Words?

According to a recent study that will be published in the Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, here’s the number of words kids will hear by the time they are 5-years-old:

- Never read to: 4,662 words

- 1-2 times per week: 63,570 words

- 3-5 times per week: 169,520 words

- Read daily: 296,660 words

- Read five books a day: 1,483,300 words

The jump in words between the “never read to” and “5 books a day” is astounding. I have to admit, I never realized the amount of word exposure children get with just five books a day. Granted, I did know how important reading is from a young age, but my goodness! The research is overwhelming!

The Importance of Reading to Kids

A controversial 1992 study suggested that children growing up in poverty hear about 30 million fewer words in conversation by age 3 than those from more privileged backgrounds. This study went on to state that children who are raised with professional parents hear, on average, 45 million words, and an average child in the working-class hears 26 million words. Children whose families are on welfare hear around 13 million words. Other studies since then have suggested this 30 million word gap may be much smaller or even non-existent.

Another study showed that 86-98% of the words in a child’s vocabulary were also found in their parents’ vocabulary. So, what does this tell us? Kids listen to what we say. Whether we are talking to them or not, they will pick up on vocabulary words.

What’s the Difference between Conversation and Books?

As a speech pathologist, I get parents who ask me, “well, I’m talking to him, isn’t that enough?” The short answer is, no . . . it’s not. The reason for this is because the vocabulary in books is more advanced and specific compared to what we use in conversation with our toddlers.

For example, my daughter’s favorite group for about 3 months of her life was a book about spiders. Yes, I know . . . gross. This book had words like “arachnid,” “abdomen,” “jaws,” and “lush forests.” I had never used those words in general conversations with her. When she stopped wanting to read this book and moved on to Moana (thankfully), she would randomly ask me about the abdomen of a spider. I was amazed that she remembered. Flash forward a little further and the movie, Beetlejuice was on TV. A spider is shown in the beginning and she said, “look, mommy, arachnid.”

This leads me to another point . . . just because your child doesn’t say the word right away, doesn’t mean they don’t understand and retain the information. Sometimes children learn after many repetitions of words in order for it to “sink in.” It was about a month after we stopped reading the spider book that my daughter was repeating words from it and was able to generalize the information to a movie.

Boost Your Child’s Speech Development!

Improve language & communication skills with fun learning!

A Speech Therapist’s Experience

I worked as an early intervention therapist for about five years. During that time, I had a wide range of families from different economic backgrounds. One of the children I worked with was a 2-year-old little girl whose family only spoke Spanish. She went to an English language preschool and wasn’t learning either language successfully.

When giving family education at the end of the session, I asked about reading books. I knew they didn’t have any as their income level was probably considered below poverty level. I, with the help of an interpreter, reinforced the importance of reading at least 2 books a day to the little girl to help expose her to language. The mom did take her to the library to pick out two books for our next session.

The little girl LOVED it. In fact, she kept giving me the books over and over again to read. We continued to do this at the end of every session and she began speaking. By the time she turned three and was aged-out of early intervention, she was speaking in short phrases.

I know we are busy as parents and it’s hard to budget that time. I can tell you what works for me. We started reading to our daughter when she was around 9-months-old, and we read as many books as possible until she finished her night time bottle. We still read to her before she goes to bed. She now picks her books, which makes it more fun for her.

Start incorporating reading into your night time routine! Kids thrive on routines and will eventually get the hang of it. Pick books or topics that you know they are interested in reading.

Get started with Speech Blubs

Cancel anytime, hassle-free!