«Conflict zone» redirects here. For the 2001 video game, see Conflict Zone.

«Warfare» redirects here. For the racehorse, see Warfare (horse).

War is an intense armed conflict[a] between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular or irregular military forces. Warfare refers to the common activities and characteristics of types of war, or of wars in general.[2] Total war is warfare that is not restricted to purely legitimate military targets, and can result in massive civilian or other non-combatant suffering and casualties.

While some war studies scholars consider war a universal and ancestral aspect of human nature,[3] others argue it is a result of specific socio-cultural, economic or ecological circumstances.[4]

Etymology

The English word war derives from the 11th-century Old English words wyrre and werre, from Old French werre (also guerre as in modern French), in turn from the Frankish *werra, ultimately deriving from the Proto-Germanic *werzō ‘mixture, confusion‘. The word is related to the Old Saxon werran, Old High German werran, and the modern German verwirren, meaning ‘to confuse, to perplex, to bring into confusion‘.[5]

History

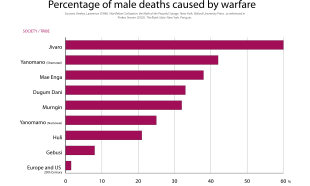

The percentages of men killed in war in eight tribal societies, and Europe and the U.S. in the 20th century. (Lawrence H. Keeley, archeologist)

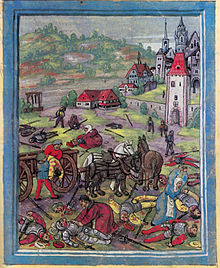

The earliest evidence of prehistoric warfare is a Mesolithic cemetery in Jebel Sahaba, which has been determined to be approximately 14,000 years old. About forty-five percent of the skeletons there displayed signs of violent death.[6] Since the rise of the state some 5,000 years ago,[7] military activity has occurred over much of the globe. The advent of gunpowder and the acceleration of technological advances led to modern warfare. Estimates for total deaths due to war vary wildly. For the period 3000 BCE until now stated estimates range from 145 million to 2 billion[8] In one estimate, primitive warfare prior to 3000 BCE has been thought to have claimed 400 million victims based on the assumption that it accounted for the 15.1% of all deaths.[9] For comparison, an estimated 1,680,000,000 people died from infectious diseases in the 20th century.[10]

In War Before Civilization, Lawrence H. Keeley, a professor at the University of Illinois, says approximately 90–95% of known societies throughout history engaged in at least occasional warfare,[11] and many fought constantly.[12]

Keeley describes several styles of primitive combat such as small raids, large raids, and massacres. All of these forms of warfare were used by primitive societies, a finding supported by other researchers.[13] Keeley explains that early war raids were not well organized, as the participants did not have any formal training. Scarcity of resources meant defensive works were not a cost-effective way to protect the society against enemy raids.[14]

William Rubinstein wrote «Pre-literate societies, even those organised in a relatively advanced way, were renowned for their studied cruelty.'»[15]

In Western Europe, since the late 18th century, more than 150 conflicts and about 600 battles have taken place.[16] During the 20th century, war resulted in a dramatic intensification of the pace of social changes, and was a crucial catalyst for the growth of left-wing politics.[17]

In 1947, in view of the rapidly increasingly destructive consequences of modern warfare, and with a particular concern for the consequences and costs of the newly developed atom bomb, Albert Einstein famously stated, «I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.»[18]

Mao Zedong urged the socialist camp not to fear nuclear war with the United States since, even if «half of mankind died, the other half would remain while imperialism would be razed to the ground and the whole world would become socialist.»[19]

A distinctive feature of war since 1945 is that combat has largely been a matter of civil wars and insurgencies.[20] The major exceptions were the Korean War, the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, the Iran–Iraq War, the Gulf War, the Eritrean–Ethiopian War, and the Russo-Ukrainian War.

American tanks moving in formation during the Gulf War.

The Human Security Report 2005 documented a significant decline in the number and severity of armed conflicts since the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s. However, the evidence examined in the 2008 edition of the Center for International Development and Conflict Management’s «Peace and Conflict» study indicated the overall decline in conflicts had stalled.[21]

Types of warfare

- Asymmetric warfare is a conflict between belligerents of drastically different levels of military capability or size.

- Biological warfare, or germ warfare, is the use of weaponized biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi.

- Chemical warfare involves the use of weaponized chemicals in combat. Poison gas as a chemical weapon was principally used during World War I, and resulted in over a million estimated casualties, including more than 100,000 civilians.[22]

- Cold warfare is an intense international rivalry without direct military conflict, but with a sustained threat of it, including high levels of military preparations, expenditures, and development, and may involve active conflicts by indirect means, such as economic warfare, political warfare, covert operations, espionage, cyberwarfare, or proxy wars.

- Conventional warfare is declared war between states in which nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons are not used or see limited deployment.

- Cyberwarfare involves the actions by a nation-state or international organization to attack and attempt to damage another nation’s information systems.

- Insurgency is a rebellion against authority, when those taking part in the rebellion are not recognized as belligerents (lawful combatants). An insurgency can be fought via counterinsurgency, and may also be opposed by measures to protect the population, and by political and economic actions of various kinds aimed at undermining the insurgents’ claims against the incumbent regime.

- Information warfare is the application of destructive force on a large scale against information assets and systems, against the computers and networks that support the four critical infrastructures (the power grid, communications, financial, and transportation).[23]

- Nuclear warfare is warfare in which nuclear weapons are the primary, or a major, method of achieving capitulation.

- Total war is warfare by any means possible, disregarding the laws of war, placing no limits on legitimate military targets, using weapons and tactics resulting in significant civilian casualties, or demanding a war effort requiring significant sacrifices by the friendly civilian population.

- Unconventional warfare, the opposite of conventional warfare, is an attempt to achieve military victory through acquiescence, capitulation, or clandestine support for one side of an existing conflict.

Aims

Entities contemplating going to war and entities considering whether to end a war may formulate war aims as an evaluation/propaganda tool. War aims may stand as a proxy for national-military resolve.[24]

Definition

Fried defines war aims as «the desired territorial, economic, military or other benefits expected following successful conclusion of a war».[25]

Classification

Tangible/intangible aims:

- Tangible war aims may involve (for example) the acquisition of territory (as in the German goal of Lebensraum in the first half of the 20th century) or the recognition of economic concessions (as in the Anglo-Dutch Wars).

- Intangible war aims – like the accumulation of credibility or reputation[26] – may have more tangible expression («conquest restores prestige, annexation increases power»).[27]

Explicit/implicit aims:

- Explicit war aims may involve published policy decisions.

- Implicit war aims[28] can take the form of minutes of discussion, memoranda and instructions.[29]

Positive/negative aims:

- «Positive war aims» cover tangible outcomes.

- «Negative war aims» forestall or prevent undesired outcomes.[30]

War aims can change in the course of conflict and may eventually morph into «peace conditions»[31] – the minimal conditions under which a state may cease to wage a particular war.

Effects

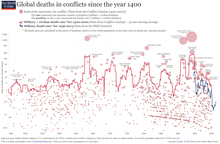

Global deaths in conflicts since the year 1400.[32]

Military and civilian casualties modern human history

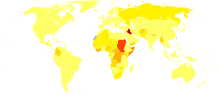

Disability-adjusted life year for war per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004[33]

no data

less than 100

100–200

200–600

600–1000

1000–1400

1400–1800

1800–2200

2200–2600

2600–3000

3000–8000

8000–8800

more than 8800

Throughout the course of human history, the average number of people dying from war has fluctuated relatively little, being about 1 to 10 people dying per 100,000. However, major wars over shorter periods have resulted in much higher casualty rates, with 100-200 casualties per 100,000 over a few years. While conventional wisdom holds that casualties have increased in recent times due to technological improvements in warfare, this is not generally true. For instance, the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) had about the same number of casualties per capita as World War I, although it was higher during World War II (WWII). That said, overall the number of casualties from war has not significantly increased in recent times. Quite to the contrary, on a global scale the time since WWII has been unusually peaceful.[34]

Largest by death toll

The deadliest war in history, in terms of the cumulative number of deaths since its start, is World War II, from 1939 to 1945, with 70–85 million deaths, followed by the Mongol conquests[35] at up to 60 million. As concerns a belligerent’s losses in proportion to its prewar population, the most destructive war in modern history may have been the Paraguayan War (see Paraguayan War casualties). In 2013 war resulted in 31,000 deaths, down from 72,000 deaths in 1990.[36] In 2003, Richard Smalley identified war as the sixth biggest problem (of ten) facing humanity for the next fifty years.[37] War usually results in significant deterioration of infrastructure and the ecosystem, a decrease in social spending, famine, large-scale emigration from the war zone, and often the mistreatment of prisoners of war or civilians.[38][39][40] For instance, of the nine million people who were on the territory of the Byelorussian SSR in 1941, some 1.6 million were killed by the Germans in actions away from battlefields, including about 700,000 prisoners of war, 500,000 Jews, and 320,000 people counted as partisans (the vast majority of whom were unarmed civilians).[41] Another byproduct of some wars is the prevalence of propaganda by some or all parties in the conflict,[42] and increased revenues by weapons manufacturers.[43]

Three of the ten most costly wars, in terms of loss of life, have been waged in the last century. These are the two World Wars, followed by the Second Sino-Japanese War (which is sometimes considered part of World War II, or as overlapping). Most of the others involved China or neighboring peoples. The death toll of World War II, being over 60 million, surpasses all other war-death-tolls.[44]

| Deaths (millions) |

Date | War |

|---|---|---|

| 70–85 | 1939–1945 | World War II (see World War II casualties) |

| 60 | 13th century | Mongol Conquests (see Mongol invasions and Tatar invasions)[45][46][47] |

| 40 | 1850–1864 | Taiping Rebellion (see Dungan Revolt)[48] |

| 39 | 1914–1918 | World War I (see World War I casualties)[49] |

| 36 | 755–763 | An Lushan Rebellion (death toll uncertain)[50] |

| 25 | 1616–1662 | Qing dynasty conquest of Ming dynasty[44] |

| 20 | 1937–1945 | Second Sino-Japanese War[51] |

| 20 | 1370–1405 | Conquests of Tamerlane[52][53] |

| 20.77 | 1862–1877 | Dungan Revolt[54][55] |

| 5–9 | 1917–1922 | Russian Civil War and Foreign Intervention[56] |

On military personnel

Military personnel subject to combat in war often suffer mental and physical injuries, including depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, disease, injury, and death.

In every war in which American soldiers have fought in, the chances of becoming a psychiatric casualty – of being debilitated for some period of time as a consequence of the stresses of military life – were greater than the chances of being killed by enemy fire.

— No More Heroes, Richard Gabriel[16]

Swank and Marchand’s World War II study found that after sixty days of continuous combat, 98% of all surviving military personnel will become psychiatric casualties. Psychiatric casualties manifest themselves in fatigue cases, confusional states, conversion hysteria, anxiety, obsessional and compulsive states, and character disorders.[57]

One-tenth of mobilised American men were hospitalised for mental disturbances between 1942 and 1945, and after thirty-five days of uninterrupted combat, 98% of them manifested psychiatric disturbances in varying degrees.

— 14–18: Understanding the Great War, Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau, Annette Becker[16]

Additionally, it has been estimated anywhere from 18% to 54% of Vietnam war veterans suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder.[57]

Based on 1860 census figures, 8% of all white American males aged 13 to 43 died in the American Civil War, including about 6% in the North and approximately 18% in the South.[58] The war remains the deadliest conflict in American history, resulting in the deaths of 620,000 military personnel. United States military casualties of war since 1775 have totaled over two million. Of the 60 million European military personnel who were mobilized in World War I, 8 million were killed, 7 million were permanently disabled, and 15 million were seriously injured.[59]

The remains of dead Crow Indians killed and scalped by Sioux c. 1874

During Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow, more French military personnel died of typhus than were killed by the Russians.[60] Of the 450,000 soldiers who crossed the Neman on 25 June 1812, less than 40,000 returned. More military personnel were killed from 1500 to 1914 by typhus than from military action.[61] In addition, if it were not for modern medical advances there would be thousands more dead from disease and infection. For instance, during the Seven Years’ War, the Royal Navy reported it conscripted 184,899 sailors, of whom 133,708 (72%) died of disease or were ‘missing’.[62]

It is estimated that between 1985 and 1994, 378,000 people per year died due to war.[63]

On civilians

Most wars have resulted in significant loss of life, along with destruction of infrastructure and resources (which may lead to famine, disease, and death in the civilian population). During the Thirty Years’ War in Europe, the population of the Holy Roman Empire was reduced by 15 to 40 percent.[64][65] Civilians in war zones may also be subject to war atrocities such as genocide, while survivors may suffer the psychological aftereffects of witnessing the destruction of war. War also results in lower quality of life and worse health outcomes. A medium-sized conflict with about 2,500 battle deaths reduces civilian life expectancy by one year and increases infant mortality by 10% and malnutrition by 3.3%. Additionally, about 1.8% of the population loses access to drinking water.[66]

Most estimates of World War II casualties indicate around 60 million people died, 40 million of whom were civilians.[67] Deaths in the Soviet Union were around 27 million.[68] Since a high proportion of those killed were young men who had not yet fathered any children, population growth in the postwar Soviet Union was much lower than it otherwise would have been.[69]

Economic

Once a war has ended, losing nations are sometimes required to pay war reparations to the victorious nations. In certain cases, land is ceded to the victorious nations. For example, the territory of Alsace-Lorraine has been traded between France and Germany on three different occasions.[70]

Typically, war becomes intertwined with the economy and many wars are partially or entirely based on economic reasons. Following World War II, consensus opinion for many years amongst economists and historians was that war can stimulate a country’s economy as evidenced by the U.S’s emergence from the Great Depression,[71] though modern economic analysis has thrown significant doubt on these views. In most cases, such as the wars of Louis XIV, the Franco-Prussian War, and World War I, warfare primarily results in damage to the economy of the countries involved. For example, Russia’s involvement in World War I took such a toll on the Russian economy that it almost collapsed and greatly contributed to the start of the Russian Revolution of 1917.[72]

World War II

World War II was the most financially costly conflict in history; its belligerents cumulatively spent about a trillion U.S. dollars on the war effort (as adjusted to 1940 prices).[73][74]

The Great Depression of the 1930s ended as nations increased their production of war materials.[75]

By the end of the war, 70% of European industrial infrastructure was destroyed.[76] Property damage in the Soviet Union inflicted by the Axis invasion was estimated at a value of 679 billion rubles. The combined damage consisted of complete or partial destruction of 1,710 cities and towns, 70,000 villages/hamlets, 2,508 church buildings, 31,850 industrial establishments, 40,000 mi (64,374 km) of railroad, 4100 railroad stations, 40,000 hospitals, 84,000 schools, and 43,000 public libraries.[77]

Theories of motivation

There are many theories about the motivations for war, but no consensus about which are most common.[78] Carl von Clausewitz said, ‘Every age has its own kind of war, its own limiting conditions, and its own peculiar preconceptions.’[79]

Psychoanalytic

Dutch psychoanalyst Joost Meerloo held that, «War is often…a mass discharge of accumulated internal rage (where)…the inner fears of mankind are discharged in mass destruction.»[80]

Other psychoanalysts such as E.F.M. Durban and John Bowlby have argued human beings are inherently violent.[81] This aggressiveness is fueled by displacement and projection where a person transfers his or her grievances into bias and hatred against other races, religions, nations or ideologies. By this theory, the nation state preserves order in the local society while creating an outlet for aggression through warfare.

The Italian psychoanalyst Franco Fornari, a follower of Melanie Klein, thought war was the paranoid or projective «elaboration» of mourning.[82] Fornari thought war and violence develop out of our «love need»: our wish to preserve and defend the sacred object to which we are attached, namely our early mother and our fusion with her. For the adult, nations are the sacred objects that generate warfare. Fornari focused upon sacrifice as the essence of war: the astonishing willingness of human beings to die for their country, to give over their bodies to their nation.

Despite Fornari’s theory that man’s altruistic desire for self-sacrifice for a noble cause is a contributing factor towards war, few wars have originated from a desire for war among the general populace.[83] Far more often the general population has been reluctantly drawn into war by its rulers. One psychological theory that looks at the leaders is advanced by Maurice Walsh.[84] He argues the general populace is more neutral towards war and wars occur when leaders with a psychologically abnormal disregard for human life are placed into power. War is caused by leaders who seek war such as Napoleon and Hitler. Such leaders most often come to power in times of crisis when the populace opts for a decisive leader, who then leads the nation to war.

Naturally, the common people don’t want war; neither in Russia nor in England nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy or a fascist dictatorship or a Parliament or a Communist dictatorship. … the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country.

Evolutionary

Several theories concern the evolutionary origins of warfare. There are two main schools: One sees organized warfare as emerging in or after the Mesolithic as a result of complex social organization and greater population density and competition over resources; the other sees human warfare as a more ancient practice derived from common animal tendencies, such as territoriality and sexual competition.[86]

The latter school argues that since warlike behavior patterns are found in many primate species such as chimpanzees,[87] as well as in many ant species,[88] group conflict may be a general feature of animal social behavior. Some proponents of the idea argue that war, while innate, has been intensified greatly by developments of technology and social organization such as weaponry and states.[89]

Psychologist and linguist Steven Pinker argued that war-related behaviors may have been naturally selected in the ancestral environment due to the benefits of victory.[b] He also argued that in order to have credible deterrence against other groups (as well as on an individual level), it was important to have a reputation for retaliation, causing humans to develop instincts for revenge as well as for protecting a group’s (or an individual’s) reputation («honor»).[b]

Increasing population and constant warfare among the Maya city-states over resources may have contributed to the eventual collapse of the Maya civilization by AD 900.

Crofoot and Wrangham have argued that warfare, if defined as group interactions in which «coalitions attempt to aggressively dominate or kill members of other groups», is a characteristic of most human societies. Those in which it has been lacking «tend to be societies that were politically dominated by their neighbors».[91]

Ashley Montagu strongly denied universalistic instinctual arguments, arguing that social factors and childhood socialization are important in determining the nature and presence of warfare. Thus, he argues, warfare is not a universal human occurrence and appears to have been a historical invention, associated with certain types of human societies.[92] Montagu’s argument is supported by ethnographic research conducted in societies where the concept of aggression seems to be entirely absent, e.g. the Chewong and Semai of the Malay peninsula.[93] Bobbi S. Low has observed correlation between warfare and education, noting societies where warfare is commonplace encourage their children to be more aggressive.[94]

Economic

War can be seen as a growth of economic competition in a competitive international system. In this view wars begin as a pursuit of markets for natural resources and for wealth. War has also been linked to economic development by economic historians and development economists studying state-building and fiscal capacity.[95] While this theory has been applied to many conflicts, such counter arguments become less valid as the increasing mobility of capital and information level the distributions of wealth worldwide, or when considering that it is relative, not absolute, wealth differences that may fuel wars. There are those on the extreme right of the political spectrum who provide support, fascists in particular, by asserting a natural right of a strong nation to whatever the weak cannot hold by force.[96][97] Some centrist, capitalist, world leaders, including Presidents of the United States and U.S. Generals, expressed support for an economic view of war.

Marxist

The Marxist theory of war is quasi-economic in that it states all modern wars are caused by competition for resources and markets between great (imperialist) powers, claiming these wars are a natural result of capitalism. Marxist economists Karl Kautsky, Rosa Luxemburg, Rudolf Hilferding and Vladimir Lenin theorized that imperialism was the result of capitalist countries needing new markets. Expansion of the means of production is only possible if there is a corresponding growth in consumer demand. Since the workers in a capitalist economy would be unable to fill the demand, producers must expand into non-capitalist markets to find consumers for their goods, hence driving imperialism.[98]

Demographic

Demographic theories can be grouped into two classes, Malthusian and youth bulge theories:

Malthusian

Malthusian theories see expanding population and scarce resources as a source of violent conflict.

Pope Urban II in 1095, on the eve of the First Crusade, advocating Crusade as a solution to European overpopulation, said:

For this land which you now inhabit, shut in on all sides by the sea and the mountain peaks, is too narrow for your large population; it scarcely furnishes food enough for its cultivators. Hence it is that you murder and devour one another, that you wage wars, and that many among you perish in civil strife. Let hatred, therefore, depart from among you; let your quarrels end. Enter upon the road to the Holy Sepulchre; wrest that land from a wicked race, and subject it to yourselves.[99]

This is one of the earliest expressions of what has come to be called the Malthusian theory of war, in which wars are caused by expanding populations and limited resources. Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) wrote that populations always increase until they are limited by war, disease, or famine.[100]

The violent herder–farmer conflicts in Nigeria, Mali, Sudan and other countries in the Sahel region have been exacerbated by land degradation and population growth.[101][102][103]

Youth bulge

Median age by country. War reduces life expectancy. A youth bulge is evident for Africa, and to a lesser extent in some countries in West Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia and Central America.

According to Heinsohn, who proposed youth bulge theory in its most generalized form, a youth bulge occurs when 30 to 40 percent of the males of a nation belong to the «fighting age» cohorts from 15 to 29 years of age. It will follow periods with total fertility rates as high as 4–8 children per woman with a 15–29-year delay.[104][105]

Heinsohn saw both past «Christianist» European colonialism and imperialism, as well as today’s Islamist civil unrest and terrorism as results of high birth rates producing youth bulges.[106] Among prominent historical events that have been attributed to youth bulges are the role played by the historically large youth cohorts in the rebellion and revolution waves of early modern Europe, including the French Revolution of 1789,[107] and the effect of economic depression upon the largest German youth cohorts ever in explaining the rise of Nazism in Germany in the 1930s.[108] The 1994 Rwandan genocide has also been analyzed as following a massive youth bulge.[109]

Youth bulge theory has been subjected to statistical analysis by the World Bank,[110] Population Action International,[111] and the Berlin Institute for Population and Development.[112] Youth bulge theories have been criticized as leading to racial, gender and age discrimination.[113]

Cultural

Geoffrey Parker argues that what distinguishes the «Western way of war» based in Western Europe chiefly allows historians to explain its extraordinary success in conquering most of the world after 1500:

The Western way of war rests upon five principal foundations: technology, discipline, a highly aggressive military tradition, a remarkable capacity to innovate and to respond rapidly to the innovation of others and—from about 1500 onward—a unique system of war finance. The combination of all five provided a formula for military success….The outcome of wars has been determined less by technology, then by better war plans, the achievement of surprise, greater economic strength, and above all superior discipline. [114]

Parker argues that Western armies were stronger because they emphasized discipline, that is, «the ability of a formation to stand fast in the face of the enemy, where they’re attacking or being attacked, without giving way to the natural impulse of fear and panic.» Discipline came from drills and marching in formation, target practice, and creating small «artificial kinship groups: such as the company and the platoon, to enhance psychological cohesion and combat efficiency.[115]

Rationalist

U.S. soldiers directing artillery on enemy trucks in A Shau Valley, April 1968

Rationalism is an international relations theory or framework. Rationalism (and Neorealism (international relations)) operate under the assumption that states or international actors are rational, seek the best possible outcomes for themselves, and desire to avoid the costs of war.[116] Under one game theory approach, rationalist theories posit all actors can bargain, would be better off if war did not occur, and likewise seek to understand why war nonetheless reoccurs. Under another rationalist game theory without bargaining, the peace war game, optimal strategies can still be found that depend upon number of iterations played. In «Rationalist Explanations for War», James Fearon examined three rationalist explanations for why some countries engage in war:

- Issue indivisibilities

- Incentives to misrepresent or information asymmetry

- Commitment problems[116]

«Issue indivisibility» occurs when the two parties cannot avoid war by bargaining, because the thing over which they are fighting cannot be shared between them, but only owned entirely by one side or the other.

U.S. Marines direct a concentration of fire at their opponents, Vietnam, 8 May 1968

«Information asymmetry with incentives to misrepresent» occurs when two countries have secrets about their individual capabilities, and do not agree on either: who would win a war between them, or the magnitude of state’s victory or loss. For instance, Geoffrey Blainey argues that war is a result of miscalculation of strength. He cites historical examples of war and demonstrates, «war is usually the outcome of a diplomatic crisis which cannot be solved because both sides have conflicting estimates of their bargaining power.»[117] Thirdly, bargaining may fail due to the states’ inability to make credible commitments.[118]

Within the rationalist tradition, some theorists have suggested that individuals engaged in war suffer a normal level of cognitive bias,[119] but are still «as rational as you and me».[120] According to philosopher Iain King, «Most instigators of conflict overrate their chances of success, while most participants underrate their chances of injury….»[121] King asserts that «Most catastrophic military decisions are rooted in GroupThink» which is faulty, but still rational.[122]

The rationalist theory focused around bargaining is currently under debate. The Iraq War proved to be an anomaly that undercuts the validity of applying rationalist theory to some wars.[123]

Political science

The statistical analysis of war was pioneered by Lewis Fry Richardson following World War I. More recent databases of wars and armed conflict have been assembled by the Correlates of War Project, Peter Brecke and the Uppsala Conflict Data Program.[124]

The following subsections consider causes of war from system, societal, and individual levels of analysis. This kind of division was first proposed by Kenneth Waltz in Man, the State, and War and has been often used by political scientists since then.[125]: 143

System-level

There are several different international relations theory schools. Supporters of realism in international relations argue that the motivation of states is the quest for security, and conflicts can arise from the inability to distinguish defense from offense, which is called the security dilemma.[125]: 145

Within the realist school as represented by scholars such as Henry Kissinger and Hans Morgenthau, and the neorealist school represented by scholars such as Kenneth Waltz and John Mearsheimer, two main sub-theories are:

- Balance of power theory: States have the goal of preventing a single state from becoming a hegemon, and war is the result of the would-be hegemon’s persistent attempts at power acquisition. In this view, an international system with more equal distribution of power is more stable, and «movements toward unipolarity are destabilizing.»[125]: 147 However, evidence has shown power polarity is not actually a major factor in the occurrence of wars.[125]: 147–48

- Power transition theory: Hegemons impose stabilizing conditions on the world order, but they eventually decline, and war occurs when a declining hegemon is challenged by another rising power or aims to preemptively suppress them.[125]: 148 On this view, unlike for balance-of-power theory, wars become more probable when power is more equally distributed. This «power preponderance» hypothesis has empirical support.[125]: 148

The two theories are not mutually exclusive and may be used to explain disparate events according to the circumstance.[125]: 148

Liberalism as it relates to international relations emphasizes factors such as trade, and its role in disincentivizing conflict which will damage economic relations. Realists[who?] respond that military force may sometimes be at least as effective as trade at achieving economic benefits, especially historically if not as much today.[125]: 149 Furthermore, trade relations which result in a high level of dependency may escalate tensions and lead to conflict.[125]: 150 Empirical data on the relationship of trade to peace are mixed, and moreover, some evidence suggests countries at war don’t necessarily trade less with each other.[125]: 150

Societal-level

- Diversionary theory, also known as the «scapegoat hypothesis», suggests the politically powerful may use war to as a diversion or to rally domestic popular support.[125]: 152 This is supported by literature showing out-group hostility enhances in-group bonding, and a significant domestic «rally effect» has been demonstrated when conflicts begin.[125]: 152–13 However, studies examining the increased use of force as a function of need for internal political support are more mixed.[125]: 152–53 U.S. war-time presidential popularity surveys taken during the presidencies of several recent U.S. leaders have supported diversionary theory.[126]

Individual-level

These theories suggest differences in people’s personalities, decision-making, emotions, belief systems, and biases are important in determining whether conflicts get out of hand.[125]: 157 For instance, it has been proposed that conflict is modulated by bounded rationality and various cognitive biases,[125]: 157 such as prospect theory.[127]

Ethics

The morality of war has been the subject of debate for thousands of years.[128]

The two principal aspects of ethics in war, according to the just war theory, are jus ad bellum and jus in bello.[129]

Jus ad bellum (right to war), dictates which unfriendly acts and circumstances justify a proper authority in declaring war on another nation. There are six main criteria for the declaration of a just war: first, any just war must be declared by a lawful authority; second, it must be a just and righteous cause, with sufficient gravity to merit large-scale violence; third, the just belligerent must have rightful intentions – namely, that they seek to advance good and curtail evil; fourth, a just belligerent must have a reasonable chance of success; fifth, the war must be a last resort; and sixth, the ends being sought must be proportional to means being used.[130][131]

Jus in bello (right in war), is the set of ethical rules when conducting war. The two main principles are proportionality and discrimination. Proportionality regards how much force is necessary and morally appropriate to the ends being sought and the injustice suffered.[132] The principle of discrimination determines who are the legitimate targets in a war, and specifically makes a separation between combatants, who it is permissible to kill, and non-combatants, who it is not.[132] Failure to follow these rules can result in the loss of legitimacy for the just-war-belligerent.[133]

In besieged Leningrad. «Hitler ordered that Moscow and Leningrad were to be razed to the ground; their inhabitants were to be annihilated or driven out by starvation. These intentions were part of the ‘General Plan East’.» – The Oxford Companion to World War II.[134]

The just war theory was foundational in the creation of the United Nations and in international law’s regulations on legitimate war.[128]

Lewis Coser, U.S. conflict theorist and sociologist, argued conflict provides a function and a process whereby a succession of new equilibriums are created. Thus, the struggle of opposing forces, rather than being disruptive, may be a means of balancing and maintaining a social structure or society.[135]

Limiting and stopping

Anti-war rally in Washington, D.C., 15 March 2003

Religious groups have long formally opposed or sought to limit war as in the Second Vatican Council document Gaudiem et Spes: «Any act of war aimed indiscriminately at the destruction of entire cities of extensive areas along with their population is a crime against God and man himself. It merits unequivocal and unhesitating condemnation.»[136]

Anti-war movements have existed for every major war in the 20th century, including, most prominently, World War I, World War II, and the Vietnam War. In the 21st century, worldwide anti-war movements occurred in response to the United States invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. Protests opposing the War in Afghanistan occurred in Europe, Asia, and the United States.

Pauses

During a war, brief pauses of violence may be called for, and further agreed to— ceasefire, temporary cessation, humanitarian pauses and corridors, days of tranquility, de-confliction arrangements.[137] There a number of disadvantages, obstacles and hesitations against implementing such pauses such as a humanitarian corridor.[138][139] Pauses in conflict can also be ill-advised, for reasons such as «delay of defeat» and the «weakening of credibility».[140] Natural causes for a pause may include events such as the 2019 coronavirus pandemic.[141][142]

See also

- Outline of war

- Grey-zone (international relations)

Notes

- ^ The term «armed conflict» is used instead of, or in addition to, the term «war» with the former being more general in scope. The International Committee of the Red Cross differentiates between international and non-international armed conflict in their definition, «International armed conflicts exist whenever there is resort to armed force between two or more States…. Non-international armed conflicts are protracted armed confrontations occurring between governmental armed forces and the forces of one or more armed groups, or between such groups arising on the territory of a State [party to the Geneva Conventions]. The armed confrontation must reach a minimum level of intensity and the parties involved in the conflict must show a minimum of organisation.»[1]

- ^ a b

The argument is made from pages 314 to 332 of The Blank Slate.[90] Relevant quotes include on p332 «The first step in understanding violence is to set aside our abhorrence of it long enough to examine why it can sometimes pay off in evolutionary terms.», «Natural selection is powered by competition, which means that the products of natural selection — survival machines, in Richard Dawkins metaphor — should, by default, do whatever helps them survive and reproduce.». On p323 «If an obstacle stands in the way of something an organism needs, it should neutralize the obstacle by disabling or eliminating it.», «Another human obstacle consists of men monopolozing women who could otherwise be taken as wives.», «The competition can be violent». On p324 «So people have invented, and perhaps evolved, an alternate defense: the advertised deterrence policy known as lex talionis, the law of retaliation, familiar from the biblical injunction «An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.» If you can credibly say to potential adversaries, «We won’t attack first, but if we are attacked, we will survive and strike back,» you removee Hobbes’s first two incentives for quarrel, gain and mistrust.». On p326 «Also necessary for vengeance to work as a deterrent is that the willingness to pursue it be made public, because the whole point of deterrence is to give would-be attackers second thoughts beforehand. And this brings us to Hobbes’s final reason for quarrel. Thirdly, glory — though a more accurate word would be «honor».»

References

- ^ «How is the Term «Armed Conflict» Defined in International Humanitarian Law?» (PDF). International Committee of the Red Cross. March 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ «Warfare». Cambridge Dictionary. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ Šmihula, Daniel (2013): The Use of Force in International Relations, p. 67, ISBN 978-80-224-1341-1.

- ^ James, Paul; Friedman, Jonathan (2006). Globalization and Violence, Vol. 3: Globalizing War and Intervention. London: Sage Publications. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ «war». Online Etymology Dictionary. 2010. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ Keeley, Lawrence H: War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage. p. 37.

- ^ Diamond, Jared, Guns, Germs and Steel

- ^ Eckhardt, William (1991). «War-related deaths since 3000 BC». Bulletin of Peace Proposals. 22 (4): 437–443. doi:10.1177/096701069102200410. S2CID 144946896.

- ^ Matthew White, ‘Primitive War’ Archived 14 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ David McCandless, ’20th Century Death’ Archived 17 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Review: War Before Civilization». Brneurosci.org. 4 September 2006. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ Spengler (4 July 2006). «The fraud of primitive authenticity». Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on 6 July 2006. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Martin, Debra L.; Harrod, Ryan P.; Pérez, Ventura R., eds. (2012). The Bioarchaeology of Violence. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ Keeley, Lawrence H: War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage. p. 55.

- ^ W. D. Rubinstein (2004). Genocide: A History. Pearson Longman. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-582-50601-5. Archived from the original on 8 August 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ a b c World War One – A New Kind of War | Part II Archived 27 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, From 14 – 18 Understanding the Great War, by Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau, Annette Becker

- ^ Kolko 1994, p. xvii–xviii: «War in this century became an essential precondition for the emergence of a numerically powerful Left, moving it from the margins to the very center of European politics during 1917–18 and of all world affairs after 1941».

- ^ «Albert Einstein: Man of Imagination». 1947. Archived from the original on 4 June 2010. Retrieved 3 February 2010. Nuclear Age Peace Foundation paper

- ^ «Instant Wisdom: Beyond the Little Red Book». Time. 20 September 1976. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ^ Robert J. Bunker and Pamela Ligouri Bunker, «The modern state in epochal transition: The significance of irregular warfare, state deconstruction, and the rise of new warfighting entities beyond neo-medievalism.» Small Wars & Insurgencies 27.2 (2016): 325–344.

- ^ Hewitt, Joseph, J. Wilkenfield and T. Gurr Peace and Conflict 2008, Paradigm Publishers, 2007

- ^ D. Hank Ellison (24 August 2007). Handbook of Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents, Second Edition. CRC Press. pp. 567–70. ISBN 978-0-8493-1434-6.

- ^ Lewis, Brian C. «Information Warfare». Federation of American Scientist. Archived from the original on 17 June 1997. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ Sullivan, Patricia (16 July 2012). «War Aims and War Outcomes». Who Wins?: Predicting Strategic Success and Failure in Armed Conflict. Oxford University Press, USA (published 2012). p. 17. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199878338.003.0003. ISBN 9780199878338. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

A state with greater military capacity than its adversary is more likely to prevail in wars with ‘total’ war aims—the overthrow of a foreign government or annexation of territory—than in wars with more limited objectives.

- ^ Fried, Marvin Benjamin (1 July 2014). Austro-Hungarian War Aims in the Balkans During World War I. Palgrave Macmillan (published 2014). p. 4. ISBN 9781137359018. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

War aims are the desired territorial, economic, military or other benefits expected following successful conclusion of a war.

- ^ Welch distinguishes: «tangible goods such as arms, wealth, and – provided they are strategically or economically valuable – territory and resources» from «intangible goods such as credibility and reputation» – Welch, David A. (10 August 1995). Justice and the Genesis of War. Cambridge Studies in International Relations. Cambridge University Press (published 1995). p. 17. ISBN 9780521558686. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ Fried, Marvin Benjamin (1 July 2014). Austro-Hungarian War Aims in the Balkans During World War I. Palgrave Macmillan (published 2014). p. 4. ISBN 9781137359018. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

Intangibles, such as prestige or power, can also represent war aims, though often (albeit not always) their achievement is framed within a more tangible context (e.g. conquest restores prestige, annexation increases power, etc.).

- ^ Compare:Katwala, Sunder (13 February 2005). «Churchill by Paul Addison». Books. The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Archived from the original on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

[Churchill] took office and declared he had ‘not become the King’s First Minister to oversee the liquidation of the British empire’. […] His view was that an Anglo-American English-speaking alliance would seek to preserve the empire, though ending it was among Roosevelt’s implicit war aims.

- ^ Compare Fried, Marvin Benjamin (1 July 2014). Austro-Hungarian War Aims in the Balkans During World War I. Palgrave Macmillan (published 2014). p. 4. ISBN 9781137359018. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

At times, war aims were explicitly stated internally or externally in a policy decision, while at other times […] the war aims were merely discussed but not published, remaining instead in the form of memoranda or instructions.

- ^ Fried, Marvin Benjamin (1 July 2015). «‘A Life and Death Question’: Austro-Hungarian War Aims in the First World War». In Afflerbach, Holger (ed.). The Purpose of the First World War: War Aims and Military Strategies. Schriften des Historischen Kollegs. Vol. 91. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH (published 2015). p. 118. ISBN 9783110443486. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

[T]he [Austrian] Foreign Ministry […] and the Military High Command […] were in agreement that political and military hegemony over Serbia and the Western Balkans was a vital war aim. The Hungarian Prime Minister István Count Tisza, by contrast, was more preoccupied with so-called ‘negative war aims’, notably warding off hostile Romanian, Italian, and even Bulgarian intervention.

- ^ Haase, Hugo (1932). «The Debate in the Reichstag on Internal Political Conditions, April 5–6, 1916». In Lutz, Ralph Haswell (ed.). Fall of the German Empire, 1914–1918. Hoover War Library publications. Stanford University Press. p. 233. ISBN 9780804723800. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

Gentlemen, when it comes time to formulate peace conditions, it is time to think of another thing than war aims.

- ^ Roser, Max (15 November 2017). «War and Peace». Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ «Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2004». World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ «War and Peace». Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ *The Cambridge History of China: Alien regimes and border states, 907–1368, 1994, p. 622, cited by White

*Matthew White (2011-11-07). The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History’s 100 Worst Atrocities. - ^ Murray, Christopher JL; Vos, Theo; Lopez, Alan D (17 December 2014). «Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013». Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ «Top Ten Problems of Humanity for Next 50 Years», Professor R. E. Smalley, Energy & NanoTechnology Conference, Rice University, 3 May 2003.

- ^ Tanton, John (2002). The Social Contract. p. 42.

- ^ Moore, John (1992). The pursuit of happiness. p. 304.

- ^ Baxter, Richard (2013). Humanizing the Laws of War. p. 344.

- ^ Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, Basic Books, 2010, p. 250.

- ^ Dying and Death: Inter-disciplinary Perspectives. p. 153, Asa Kasher (2007)

- ^ Chew, Emry (2012). Arming the Periphery. p. 49.

- ^ a b McFarlane, Alan: The Savage Wars of Peace: England, Japan and the Malthusian Trap, Blackwell 2003, ISBN 0-631-18117-2,

ISBN 978-0-631-18117-0 – cited by White Archived 20 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Ping-ti Ho, «An Estimate of the Total Population of Sung-Chin China», in Études Song, Series 1, No 1, (1970) pp. 33–53.

- ^ «Mongol Conquests». Users.erols.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ «The world’s worst massacres Whole Earth Review». 1987. Archived from the original on 17 May 2003. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ «Taiping Rebellion – Britannica Concise». Britannica. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ Michael Duffy (22 August 2009). «Military Casualties of World War One». Firstworldwar.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ «Selected Death Tolls for Wars, Massacres and Atrocities Before the 20th Century». Users.erols.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ «Nuclear Power: The End of the War Against Japan». BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ «Timur Lenk (1369–1405)». Users.erols.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ Matthew White’s website Archived 20 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine (a compilation of scholarly death toll estimates)

- ^ 曹树基. 《中国人口史》 (in Chinese). Vol. 5《清时期》. p. 635.[full citation needed]

- ^ 路伟东. «同治光绪年间陕西人口的损失» (in Chinese).[full citation needed]

- ^ «Russian Civil War». Spartacus-Educational.com. Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ a b Lt. Col. Dave Grossman (1996). On Killing – The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War & Society. Little, Brown & Co.

- ^ Maris Vinovskis (28 September 1990). Toward a Social History of the American Civil War: Exploratory Essays. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39559-5. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ Kitchen, Martin (2000), The Treaty of Versailles and its Consequences Archived 12 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, New York: Longman

- ^ The Historical Impact of Epidemic Typhus. Joseph M. Conlon.

- ^ War and Pestilence. TIME.

- ^ A. S. Turberville (2006). Johnson’s England: An Account of the Life & Manners of His Age. p. 53. ISBN 1-4067-2726-1

- ^ Obermeyer Z, Murray CJ, Gakidou E (June 2008). «Fifty years of violent war deaths from Vietnam to Bosnia: analysis of data from the world health survey programme». BMJ. 336 (7659): 1482–86. doi:10.1136/bmj.a137. PMC 2440905. PMID 18566045.

- ^ The Thirty Years War (1618–48) Archived 20 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Alan McFarlane, The Savage Wars of Peace: England, Japan and the Malthusian Trap (2003)

- ^ History of Europe – Demographics Archived 23 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Davenport, Christian; Mokleiv Nygård, Håvard; Fjelde, Hanne; Armstrong, David (2019). «The Consequences of Contention: Understanding the Aftereffects of Political Conflict and Violence». Annual Review of Political Science. 22: 361–377. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-050317-064057.

- ^ «World War II Fatalities». Archived from the original on 22 April 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2007.

- ^ «Leaders mourn Soviet wartime dead». BBC News. 9 May 2005. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ^ Hosking, Geoffrey A. (2006). Rulers And Victims: The Russians in the Soviet Union. Harvard University Press. pp. 242–. ISBN 978-0-674-02178-5. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ «Alsace-Lorraine». Encyclopædia Britannica (Online ed.). Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ Higgs, Robert (March 1992). «Wartime Prosperity? A Reassessment of the U.S. Economy in the 1940s» (PDF). The Journal of Economic History. 52 (1): 41–60. doi:10.1017/S0022050700010251. S2CID 154484756. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ Gatrell, Peter (2014). Russia’s First World War : A Social and Economic History. Hoboken, New Jersey: Routledge. p. 270. ISBN 9781317881391.

- ^ Mayer, E. (2000). «World War II course lecture notes». Emayzine.com. Victorville, California: Victor Valley College. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ^ Coleman, P. (1999) «Cost of the War,» World War II Resource Guide (Gardena, California: The American War Library)

- ^ «Great Depression and World War II, 1929–1945». Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ^ Marc Pilisuk; Jennifer Achord Rountree (2008). Who Benefits from Global Violence and War: Uncovering a Destructive System. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-0-275-99435-8. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ The New York Times, 9 February 1946, Volume 95, Number 32158.

- ^ Levy, Jack S. (1989). Tetlock, Philip E.; Husbands, Jo L.; Jervis, Robert; Stern, Paul C.; Tilly, Charles (eds.). «The Causes of War: A Review of Theories and Evidence» (PDF). Behavior, Society and Nuclear War. I: 295. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ Clausewitz, Carl Von (1976), On War (Princeton University Press) p. 593

- ^

| A. M. Meerloo, M.D. The Rape of the Mind (2009) p. 134, Progressive Press, ISBN 978-1-61577-376-3 - ^ Durbin, E.F.L. and John Bowlby. Personal Aggressiveness and War 1939.

- ^ (Fornari 1975)

- ^ Blanning, T.C.W. «The Origin of Great Wars.» The Origins of the French Revolutionary Wars. p. 5

- ^ Walsh, Maurice N. War and the Human Race. 1971.

- ^ «In an interview with Gilbert in Göring’s jail cell during the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials (18 April 1946)». 18 April 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ Peter Meyer. Social Evolution in Franz M. Wuketits and Christoph Antweiler (eds.) Handbook of Evolution The Evolution of Human Societies and Cultures Wiley-VCH Verlag

- ^ O’Connell, Sanjida (7 January 2004). «Apes of war…is it in our genes?». The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2010. Analysis of chimpanzee war behavior

- ^ Anderson, Kenneth (1996). «Warrior Ants: The Enduring Threat of the Small War and the Land-mine». SSRN 935783. Scholarly comparisons between human and ant wars

- ^ Johan M.G. van der Dennen. 1995. The Origin of War: Evolution of a Male-Coalitional Reproductive Strategy. Origin Press, Groningen, 1995 chapters 1 & 2

- ^ Pinker, Steven (2002). The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. London: The Penguin Group. p. 314-332. ISBN 0-713-99256-5.

- ^ Mind the Gap: Tracing the Origins of Human Universals By Peter M. Kappeler, Joan B. Silk, 2009, Chapter 8, «Intergroup Aggression in Primates and Humans; The Case for a Unified Theory», Margaret C. Crofoot and Richard W. Wrangham

- ^ Montagu, Ashley (1976), The Nature of Human Aggression (Oxford University Press)

- ^ Howell, Signe and Roy Willis, eds. (1989) Societies at Peace: Anthropological Perspectives. London: Routledge

- ^ «An Evolutionary Perspective on War» Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Bobbi S. Low, published in Behavior, Culture, and Conflict in World Politics, The University of Michigan Press, p. 22

- ^ Johnson, Noel D.; Koyama, Mark (April 2017). «States and economic growth: Capacity and constraints». Explorations in Economic History. 64: 1–20. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2016.11.002.

- ^ Roger Griffin and Matthew Feldman, eds., Fascism: Fascism and Culture, New York: Routledge, 2004.

- ^ Hawkins, Mike. Social Darwinism in European and American Thought, 1860–1945: Nature as Model and Nature as Threat, Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- ^ O’Callaghan, Einde (25 October 2007). «The Marxist Theory of Imperialism and its Critics». Marxists Internet Archive. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ Safire, William (2004). Lend me your ears: great speeches in history. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-393-05931-1.

- ^ Waugh, David (2000). Geography: an integrated approach. Nelson Thornes. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-17-444706-1.

- ^ «In Mali, waning fortunes of Fulani herders play into Islamist hands». Reuters. 20 November 2016. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^ «How Climate Change Is Spurring Land Conflict in Nigeria». Time. 28 June 2018. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^ «The Deadliest Conflict You’ve Never Heard of». Foreign Policy. 23 January 2019. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^ Helgerson, John L. (2002): «The National Security Implications of Global Demographic Trends»[1] Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Heinsohn, G. (2006): «Demography and War» (online) Archived 12 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Heinsohn, G. (2005): «Population, Conquest and Terror in the 21st Century» (online) Archived 13 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jack A. Goldstone (4 March 1993). Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08267-0. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ Moller, Herbert (1968): ‘Youth as a Force in the Modern World’, Comparative Studies in Society and History 10: 238–60; 240–44

- ^ Diessenbacher, Hartmut (1994): Kriege der Zukunft: Die Bevölkerungsexplosion gefährdet den Frieden. Muenchen: Hanser 1998; see also (criticizing youth bulge theory) Marc Sommers (2006): «Fearing Africa´s Young Men: The Case of Rwanda.» The World Bank: Social Development Papers – Conflict Prevention and Reconstruction, Paper No. 32, January 2006 [2] Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Urdal, Henrik (2004): «The Devil in the Demographics: The Effect of Youth Bulges on Domestic Armed Conflict,» [3],

- ^ Population Action International: «The Security Demographic: Population and Civil Conflict after the Cold War»[4] Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kröhnert, Steffen (2004): «Warum entstehen Kriege? Welchen Einfluss haben demografische Veränderungen auf die Entstehung von Konflikten?» [5] Archived 4 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hendrixson, Anne: «Angry Young Men, Veiled Young Women: Constructing a New Population Threat» [6] Archived 30 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Geoffrey Parker, “Introduction” in Parker, ed. The Cambridge illustrated history of warfare (Cambridge University Press 1995) pp 2-11, online

- ^ Parker, :Introduction: pp 2, 3.

- ^ a b Fearon, James D. (Summer 1995). «Rationalist Explanations for War». International Organization. 49 (3): 379–414. doi:10.1017/s0020818300033324. JSTOR 2706903. S2CID 38573183.

- ^ Geoffrey Blainey (1988). Causes of War (3rd ed.). p. 114. ISBN 9780029035917. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ Powell, Robert (2002). «Bargaining Theory and International Conflict». Annual Review of Political Science. 5: 1–30. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.5.092601.141138.

- ^ Chris Cramer, ‘Civil War is Not a Stupid Thing’, ISBN 978-1850658214

- ^ From point 10 of Modern Conflict is Not What You Think (article) Archived 22 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 16 December 2014.

- ^ Quote from Iain King, in Modern Conflict is Not What You Think Archived 22 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Point 6 in Modern Conflict is Not What You Think Archived 22 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lake, David A. (November 2010). «Two Cheers for Bargaining Theory: Assessing Rationalist Explanations of the Iraq War». International Security. 35 (3): 7–52. doi:10.1162/isec_a_00029. S2CID 1096131.

- ^ «Uppsala Conflict Data Program — About». Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Levy, Jack S. (June 1998). «The Causes of War and the Conditions of Peace». Annual Review of Political Science. 1: 139–65. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.1.1.139.

- ^ «Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy (p. 19)». 2001. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2010. More recently studies (Lebow 2008, Lindemann 2010) demonstrated that striving for self-esteem (i.e. virile self images), and recognition as a Great Power or non-recognition (exclusion and punishment of great powers, denying traumatic historical events) is a principal cause of international conflict and war.

- ^ Levy, Jack S. (March 1997). «Prospect Theory, Rational Choice, and International Relations» (PDF). International Studies Quarterly. 41 (1): 87–112. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00034. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- ^ a b DeForrest, Mark Edward. «Conclusion». JUST WAR THEORY AND THE RECENT U.S. AIR STRIKES AGAINST IRAQ. Gonzaga Journal of International Law. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ Lazar, Seth (21 March 2020). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «War». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas. «Part II, Question 40». The Summa Theologica. Benziger Bros. edition, 1947. Archived from the original on 12 February 2002. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ Mosley, Alexander. «The Jus Ad Bellum Convention». Just War Theory. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 16 April 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ a b Moseley, Alexander. «The Principles of Jus in Bello». Just War Theory. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 16 April 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ Codevilla, Seabury, Angelo, Paul (1989). War: Ends and Means. New York, NY: Basic Books. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-465-09067-9.

- ^ Ian Dear, Michael Richard Daniell Foot (2001). The Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford University Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-19-860446-7

- ^ Ankony, Robert C., «Sociological and Criminological Theory: Brief of Theorists, Theories, and Terms,» CFM Research, Jul. 2012.

- ^ «PASTORAL CONSTITUTION ON THE CHURCH IN THE MODERN WORLD GAUDIUM ET SPES PROMULGATED BY HIS HOLINESS, POPE PAUL VI ON DECEMBER 7, 1965 Archived 11 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine»

- ^ Glossary of Terms: Pauses During Conflict (PDF), United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, June 2011, archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2022, retrieved 6 March 2022

- ^ «Why humanitarians wary of «humanitarian corridors»«. The New Humanitarian. 19 March 2012. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Reindorp, Nicola; Wiles, Peter (June 2001). «Humanitarian Coordination: Lessons from Recent Field Experience» (PDF). Overseas Development Institute, London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022 – via UNHCR.

- ^ Nemeth, Maj Lisa A. (2009). «The Use of Pauses in Coercion: An Examination in Theory» (PDF). Monograph. School of Advanced Military Studies, United States Army Command and General Staff College. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2022.

- ^ Laura Wise, Sanja Badanjak, Christine Bell and Fiona Knäussel (2021). «Pandemic Pauses: Understanding Ceasefires in a Time of Covid-19» (PDF). politicalsettlements.org. Political Settlements Research Programme. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Drexler, Madeline (10 September 2021). «When a Virus Strikes, Can the World Pause Its Wars? –». The Wire Science. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

Bibliography

- Barzilai, Gad (1996). Wars, Internal Conflicts and Political Order: A Jewish Democracy in the Middle East. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Beer, Francis A. (1974). How Much War in History: Definitions, Estimates, Extrapolations, and Trends. Beverly Hills: SAGE.

- Beer, Francis A. (1981). Peace against War: The Ecology of International Violence. San Francisco: W.H.Freeman.

- Beer, Francis A. (2001). Meanings of War and Peace. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

- Blainey, Geoffrey (1973). The Causes of War. Simon and Schuster.

- Butler, Smedley (1935). War is a Racket.

- Chagnon, N. (1983). The Yanomamo. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Clausewitz, Carl Von (1976). On War, Princeton University Press

- Codevilla, Angelo (2005). No Victory, No Peace. Rowman and Littlefield

- Codevilla, Angelo; Seabury, Paul (2006). War: Ends and Means (2 ed.). Potomac Books.

- Fog, Agner (2017). Warlike and Peaceful Societies: The Interaction of Genes and Culture. Open Book Publishers. doi:10.11647/OBP.0128. ISBN 978-1-78374-403-9.

- Fornari, Franco (1974). The Psychoanalysis of War. Translated by Pfeifer, Alenka. NY: Doubleday Anchor Press. ISBN 9780385043472.

- Fry, Douglas (2004). «Conclusion: Learning from Peaceful Societies». In Kemp, Graham (ed.). Keeping the Peace. Routledge. pp. 185–204.

- Fry, Douglas (2005). The Human Potential for Peace: An Anthropological Challenge to Assumptions about War and Violence. Oxford University Press.

- Fry, Douglas (2009). Beyond War. Oxford University Press.

- Gat, Azar (2006). War in Human Civilization. Oxford University Press.

- Heinsohn, Gunnar (2003). Söhne und Weltmacht: Terror im Aufstieg und Fall der Nationen [Sons and Imperial Power: Terror and the Rise and Fall of Nations] (PDF) (in German). Orell Füssl. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Howell, Signe; Willis, Roy (1990). Societies at Peace: Anthropological Perspectives. London: Routledge.

- James, Paul; Friedman, Jonathan (2006). Globalization and Violence, Vol. 3: Globalizing War and Intervention. London: Sage Publications. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- James, Paul; Sharma, RR (2006). Globalization and Violence, Vol. 4: Transnational Conflict. London: Sage Publications. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Keegan, John (1994). A History of Warfare. Pimlico.

- Keeley, Lawrence (1996). War Before Civilization, Oxford University Press.

- Keen, David (2012). Useful Enemies: When Waging Wars Is More Important Than Winning Them. Yale University Press.

- Kelly, Raymond C. (2000). Warless Societies and the Origin of War, University of Michigan Press.

- Kemp, Graham; Fry, Douglas (2004). Keeping the Peace. New York: Routledge.

- Kolko, Gabriel (1994). Century of War: Politics, Conflicts, and Society since 1914. New York, NY: The New Press.

- Lebow, Richard Ned (2008). A Cultural Theory of International Relations. Cambridge University Press.

- Lindemann, Thomas (2010). Causes of War. The Struggle for Recognition. Colchester, ECPR Press

- Maniscalco, Fabio (2007). World heritage and war: linee guida per interventi a salvaguardia dei beni culturali nelle aree a rischio bellico. Massa. ISBN 978-88-87835-89-2. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- McIntosh, Jane (2002). A Peaceful Realm: The Rise and Fall of the Indus Civilization. Oxford, UK: Westview Press.

- Metz, Steven and Cuccia, Philip R. (2011). Defining War for the 21st Century, Archived 30 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College. ISBN 978-1-58487-472-0

- Montagu, Ashley (1978). Learning Nonaggression. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Otterbein, Keith (2004). How War Began. College Station TX: Texas A&M University Press.

- Parker, Geoffrey, ed. (2008) The Cambridge Illustrated History of Warfare: The Triumph of the West (Cambridge University Press, 1995, revised 2008) online

- Pauketat, Timothy (2005). North American Archaeology. Blackwell Publishing.

- Small, Melvin; Singer, Joel David (1982). Resort to arms: international and civil wars, 1816–1980. Sage Publications. ISBN 978-0-8039-1776-7. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- Smith, David Livingstone (February 2009). The Most Dangerous Animal: Human Nature and the Origins of War. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-53744-9. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- Sponsel, Leslie; Gregor, Thomas (1994). Anthropology of Peace and Nonviolence. Lynne Rienner Publishing.

- Strachan, Hew (2013). The Direction of War. Cambridge University Press.

- Turchin, P. (2005). War and Peace and War: Life Cycles of Imperial Nations. NY: Pi Press.

- Van Creveld, Martin. The Art of War: War and Military Thought London: Cassell, Wellington House

- Wade, Nicholas (2006). Before the Dawn, New York: Penguin.

- Walzer, Michael (1977). Just and Unjust Wars. Basic Books.

External links

- An Interactive map of all the battles fought around the world in the last 4,000 years

- Timeline of wars on Histropedia

War zone safety travel guide from Wikivoyage

Noun

They fought a war over the disputed territory.

A war broke out when the colonists demanded their independence.

We need to resolve our conflicts without resorting to war.

People behave differently during a time of war.

The taking of American hostages was seen as an act of war by the United States.

the budget wars in Washington

See More

Recent Examples on the Web

The somber holiday honors those from U.K. and Commonwealth nations who died in wars.

—

Subscribe to our channel for the latest updates on Russia’s war in Ukraine.

—

In the long war between NIMBYs (not-in-my-backyard residents) and YIMBYs (yes-in-my-backyard residents) and what should be developed in certain people’s neighborhoods, critics are saying this marks a new low.

—

French President Emmanuel Macron arrived in China Wednesday and swiftly warned Chinese leader Xi Jinping not to boost support for Russia in its war against Ukraine, amid growing Western concerns over Beijing’s deepening economic and political ties with Moscow.

—

Russia briefly occupied the city early in the war.

—

The straits play a key role in the war between Russia and Ukraine due to the proximity to both countries, Foreign Policy reported.

—

The battle for Bakhmut, a coal-mining hub in Ukraine’s Donetsk region, has become a pivotal battlefield in the broader war for both Russia and Ukraine.

—

Here are a dozen mosquito repellent plants worth having in your yard, that are not only pretty, but that can help in the constant war against bug bites.

—

The series refuses to reduce its warring factions to ideological simplicity, instead embracing the moral complexity of each side and painting its characters in shades of gray.

—

The 16th main installment takes place in a medieval fantasy world, one where warring nations fight among themselves for dwindling resources.

—

On the prospects for peace talks, the warring nations continued to talk past one another, each setting preconditions that the other would call capitulation.

—

The hurdles come as separate agreements brokered last summer by Turkey and the U.N. to keep supplies moving from the warring nations and reduce soaring food prices are up for renewal next month.

—

The warring nations are both major global suppliers of wheat, barley, sunflower oil and other affordable food products that developing nations depend on.

—

The country split in 2014 between warring factions in the east and west.

—

For the past decade, the group has lived away from Mali due to ongoing violence between the warring northern and southern factions in the country.

—

Matamoros is home to warring factions of the Gulf drug cartel.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘war.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Translingual[edit]

Symbol[edit]

war

- (international standards) ISO 639-2 & ISO 639-3 language code for Waray.

English[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- warre (obsolete)

- warr (obsolete)

Etymology[edit]

From Middle English werre, from Late Old English werre, wyrre (“armed conflict”) from Old Northern French werre (compare modern French guerre), from Medieval Latin werra, from Frankish *werru (“confusion; quarrel”), from Proto-Indo-European *wers- (“to mix up, confuse, beat, thresh”). Displaced native Old English ġewinn.

Related to Old High German werra (“confusion, strife, quarrel”) and German verwirren (“to confuse”), Old Saxon werran (“to confuse, perplex”), Dutch war (“confusion, disarray”), West Frisian war (“defense, self-defense, struggle», also «confusion”),

Old English wyrsa, wiersa (“worse”), Old Norse verri (“worse, orig. confounded, mixed up”), Italian guerra (“war”). There may be a connection with worse and wurst.

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Received Pronunciation) IPA(key): /wɔː/

- (General American) IPA(key): /wɔɹ/

- Homophones: wore, wor (some dialects)

- Rhymes: -ɔː(ɹ)

- (obsolete or Philippine) IPA(key): /wɑɹ/

Noun[edit]

war (countable and uncountable, plural wars)

- (uncountable) Organized, large-scale, armed conflict between countries or between national, ethnic, or other sizeable groups, usually but not always involving active engagement of military forces.

-

1611, The Holy Bible, […] (King James Version), London: […] Robert Barker, […], →OCLC, Exodus 1:10:

-

Come on, let vs deale wisely with them, lest they multiply, and it come to passe that when there falleth out any warre, they ioyne also vnto our enemies, and fight against vs, and so get them vp out of the land.

-

- 1854, Prince George, letter to his wife from Crimea:

- War is indeed a fearful thing and the more I see it the more dreadful it appears.

- 1864 Sept. 12, William Tecumseh Sherman, letter to the mayor of Atlanta & al.:

- You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our Country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out… You might as well appeal against the thunder-storm as against these terrible hardships of war.

- 1879 June 19, William Tecumseh Sherman, speech to the Michigan Military Academy:

- I’ve been where you are now and I know just how you feel. It’s entirely natural that there should beat in the breast of every one of you a hope and desire that some day you can use the skill you have acquired here. Suppress it! You don’t know the horrible aspects of war. I’ve been through two wars and I know. I’ve seen cities and homes in ashes. I’ve seen thousands of men lying on the ground, their dead faces looking up at the skies. I tell you, war is hell!

- 1907, Edward Porter Alexander, Military Memoirs of a Confederate, p. 302:

- Here Lee and Longstreet stood during most of the fighting [at Fredericksburg], and it is told that, on one of the Federal repulses from Marye’s Hill, Lee put his hand upon Longstreet’s arm and said, «It is well that war is so terrible, or we would grow too fond of it.»

-

1922, Henry Ford; Samuel Crowther, chapter 17, in My Life and Work, Garden City, New York: Garden City Publishing Company, Inc., →OCLC:

-

Nobody can deny that war is a profitable business for those who like that kind of money. War is an orgy of money, just as it is an orgy of blood.

-

- 1935, Smedley Butler, War Is a Racket, pp. 1 & 7: