Not to be confused with Novell.

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the Italian: novella for «new», «news», or «short story of something new», itself from the Latin: novella, a singular noun use of the neuter plural of novellus, diminutive of novus, meaning «new».[1] Some novelists, including Nathaniel Hawthorne,[2] Herman Melville,[3] Ann Radcliffe,[4] John Cowper Powys,[5] preferred the term «romance» to describe their novels.

According to Margaret Doody, the novel has «a continuous and comprehensive history of about two thousand years», with its origins in the Ancient Greek and Roman novel, in Chivalric romance, and in the tradition of the Italian Renaissance novella.[6] The ancient romance form was revived by Romanticism, especially the historical romances of Walter Scott and the Gothic novel.[7] Some, including M. H. Abrams and Walter Scott, have argued that a novel is a fiction narrative that displays a realistic depiction of the state of a society, while the romance encompasses any fictitious narrative that emphasizes marvellous or uncommon incidents.[8][9][10]

Works of fiction that include marvellous or uncommon incidents are also novels, including The Lord of the Rings,[11] To Kill a Mockingbird,[12] and Frankenstein.[13] «Romances» are works of fiction whose main emphasis is on marvellous or unusual incidents, and should not be confused with the romance novel, a type of genre fiction that focuses on romantic love.

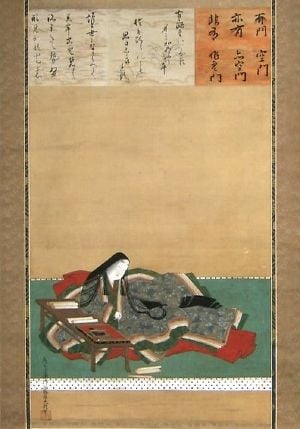

Murasaki Shikibu’s Tale of Genji, an early 11th-century Japanese text, has sometimes been described as the world’s first novel based on its early use of the experience of intimacy in a narrative form, but there is considerable debate over this — there were certainly long fictional prose works that preceded it. Spread of printed books in China led to the appearance of classical Chinese novels by the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and Qing dynasty (1616-1911). An early example from Europe was written in Muslim Spain by the Sufi writer Ibn Tufayl entitled Hayy ibn Yaqdhan.[14] Later developments occurred after the invention of the printing press. Miguel de Cervantes, author of Don Quixote (the first part of which was published in 1605), is frequently cited as the first significant European novelist of the modern era.[15] Literary historian Ian Watt, in The Rise of the Novel (1957), argued that the modern novel was born in the early 18th century.

Recent technological developments have led to many novels also being published in non-print media: this includes audio books, web novels, and ebooks. Another non-traditional fiction format can be found in some graphic novels. While these comic book versions of works of fiction have their origins in the 19th century, they have only become popular more recently.

Defining the genre[edit]

A novel is a long, fictional narrative. The novel in the modern era usually makes use of a literary prose style. The development of the prose novel at this time was encouraged by innovations in printing, and the introduction of cheap paper in the 15th century.

Several characteristics of a novel might include:

- Fictional narrative: Fictionality is most commonly cited as distinguishing novels from historiography. However this can be a problematic criterion. Throughout the early modern period authors of historical narratives would often include inventions rooted in traditional beliefs in order to embellish a passage of text or add credibility to an opinion. Historians would also invent and compose speeches for didactic purposes. Novels can, on the other hand, depict the social, political and personal realities of a place and period with clarity and detail not found in works of history. Several novels, for example Ông cố vấn written by Hữu Mai, were designed to be and defined as a «non-fiction» novel which purposefully recorded historical facts in the form of a novel.

- Literary prose: While prose rather than verse became the standard of the modern novel, the ancestors of the modern European novel include verse epics in the Romance language of southern France, especially those by Chrétien de Troyes (late 12th century), and in Middle English (Geoffrey Chaucer’s (c. 1343 – 1400) The Canterbury Tales).[16] Even in the 19th century, fictional narratives in verse, such as Lord Byron’s Don Juan (1824), Alexander Pushkin’s Yevgeniy Onegin (1833), and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh (1856), competed with prose novels. Vikram Seth’s The Golden Gate (1986), composed of 590 Onegin stanzas, is a more recent example of the verse novel.[17]

- Experience of intimacy: Both in 11th-century Japan and 15th-century Europe, prose fiction created intimate reading situations. Harold Bloom[18] characterizes Lady Murasaki’s use of intimacy and irony in The Tale of Genji as «having anticipated Cervantes as the first novelist.» On the other hand, verse epics, including the Odyssey and Aeneid, had been recited to select audiences, though this was a more intimate experience than the performance of plays in theaters. A new world of individualistic fashion, personal views, intimate feelings, secret anxieties, «conduct», and «gallantry» spread with novels and the associated prose-romance.

- Length: The novel is today the longest genre of narrative prose fiction, followed by the novella. However, in the 17th century, critics saw the romance as of epic length and the novel as its short rival. A precise definition of the differences in length between these types of fiction, is, however, not possible. The philosopher and literary critic György Lukács argued that the requirement of length is connected with the notion that a novel should encompass the totality of life.[19]

East Asian definition[edit]

East Asian countries, like China, Korea, Vietnam and Japan, use the word 小說 (pinyin: xiǎoshuō), which literally means «small talks», to refer works of fiction of whatever length.[20] In Chinese, Japanese and Korean cultures, the concept of novel as it is known in the Western/Anglophone world was and still is termed as «long length small talk» (長篇小說), novella as «medium length small talk» (中篇小說), and short stories as «short length small talk» (短篇小說). However, in Vietnamese culture, the term 小說 exclusively refers to 長篇小說 (long-length small talk), i.e. standard novel, while different terms are used to refer to novella and short stories.

Such terms originated from ancient Chinese classification of literature works into «small talks» (tales of daily life and trivial matters) and «great talks» («sacred» classic works of great thinkers like Confucius). In other words, ancient definition of «small talks» merely refer to trivial affairs, trivial facts, and can be different from the Western concept of novel. According to Lu Xun, the word «small talks» first appeared in the works of Zhuang Zhou, which coined such word. Later scholars also provided similar definition, such as Han dynasty historian Ban Gu categorized all the trivial stories and gossips collected by local government magistrates as «small talks». Hồ Nguyên Trừng classified his memoir collection Nam Ông mộng lục as «small talks» clearly with the meaning of «trivial facts» rather than the Western definition of novel. Such classification and also left strong legacy in several East Asian interpretations of Western definition of novel at the time when Western literature was first introduced to East Asian countries. For example, Thanh Lãng and Nhất Linh classified the epic poems such as The Tale of Kiều as «novel», while Trần Chánh Chiếu emphasized the «belongs to the commoners», «trivial daily talks» aspect in one of his work.[21][22][23][24][25]

Early novels[edit]

The earliest novels include classical Greek and Latin prose narratives from the first century BC to the second century AD, such as Chariton’s Callirhoe (mid 1st century), which is «arguably the earliest surviving Western novel»,[26] as well as Petronius’ Satyricon, Lucian’s True Story, Apuleius’ The Golden Ass, and the anonymous Aesop Romance and Alexander Romance. The style of these works was later adapted in later Byzantine novels such as Hysimine and Hysimines by Eustathios Makrembolites[27] Narrative forms were also developed in Classical Sanskrit in the 5th through 8th centuries, such as Vasavadatta by Subandhu, Daśakumāracarita and Avantisundarīkathā by Daṇḍin, Kadambari by Banabhatta.

Urbanization and the spread of printed books in Song Dynasty (960–1279) led China[citation needed] to the evolution of oral storytelling into fictional novels by the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Parallel European developments did not occur until after the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1439, and the rise of the publishing industry over a century later allowed for similar opportunities.[28] The modern European novel is often said to have begun with Don Quixote in 1605.[15]

Medieval period 1100–1500[edit]

Chivalric romances[edit]

Romance or chivalric romance is a type of narrative in prose or verse popular in the aristocratic circles of High Medieval and Early Modern Europe. They were marvel-filled adventures, often of a knight-errant with heroic qualities, who undertakes a quest, yet it is «the emphasis on heterosexual love and courtly manners distinguishes it from the chanson de geste and other kinds of epic, which involve heroism.»[29] In later romances, particularly those of French origin, there is a marked tendency to emphasize themes of courtly love.

Originally, romance literature was written in Old French, Anglo-Norman and Occitan, later, in English, Italian and German. During the early 13th century, romances were increasingly written as prose.

The shift from verse to prose dates from the early 13th century. The Prose Lancelot or Vulgate Cycle includes passages from that period. This collection indirectly led to Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur of the early 1470s. Prose became increasingly attractive because it enabled writers to associate popular stories with serious histories traditionally composed in prose, and could also be more easily translated.[30]

Popular literature also drew on themes of romance, but with ironic, satiric or burlesque intent. Romances reworked legends, fairy tales, and history, but by about 1600 they were out of fashion, and Miguel de Cervantes famously burlesqued them in Don Quixote (1605). Still, the modern image of the medieval is more influenced by the romance than by any other medieval genre, and the word «medieval» evokes knights, distressed damsels, dragons, and such tropes.[31]

The novella[edit]

The term «novel» originates from the production of short stories, or novella that remained part of a European oral culture of storytelling into the late 19th century. Fairy tales, jokes, and humorous stories designed to make a point in a conversation, and the exemplum a priest would insert in a sermon belong into this tradition. Written collections of such stories circulated in a wide range of products from practical compilations of examples designed for the use of clerics to compilations of various stories such as Boccaccio’s Decameron (1354) and Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (1386–1400). The Decameron was a compilation of one hundred novelle told by ten people—seven women and three men—fleeing the Black Death by escaping from Florence to the Fiesole hills, in 1348.

Renaissance period: 1500–1700[edit]

1474: The customer in the copyist’s shop with a book he wants to have copied. This illustration of the first printed German Melusine looked back to the market of manuscripts.

The modern distinction between history and fiction did not exist in the early sixteenth century and the grossest improbabilities pervade many historical accounts found in the early modern print market. William Caxton’s 1485 edition of Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (1471) was sold as a true history, though the story unfolded in a series of magical incidents and historical improbabilities. Sir John Mandeville’s Voyages, written in the 14th century, but circulated in printed editions throughout the 18th century,[32] was filled with natural wonders, which were accepted as fact, like the one-footed Ethiopians who use their extremity as an umbrella against the desert sun. Both works eventually came to be viewed as works of fiction.

In the 16th and 17th centuries two factors led to the separation of history and fiction. The invention of printing immediately created a new market of comparatively cheap entertainment and knowledge in the form of chapbooks. The more elegant production of this genre by 17th- and 18th-century authors were belles lettres—that is, a market that would be neither low nor academic. The second major development was the first best-seller of modern fiction, the Spanish Amadis de Gaula, by García Montalvo. However, it was not accepted as an example of belles lettres. The Amadis eventually became the archetypical romance, in contrast with the modern novel which began to be developed in the 17th century.

Chapbooks[edit]

A chapbook is an early type of popular literature printed in early modern Europe. Produced cheaply, chapbooks were commonly small, paper-covered booklets, usually printed on a single sheet folded into books of 8, 12, 16 and 24 pages. They were often illustrated with crude woodcuts, which sometimes bore no relation to the text. When illustrations were included in chapbooks, they were considered popular prints. The tradition arose in the 16th century, as soon as printed books became affordable, and rose to its height during the 17th and 18th centuries. Many different kinds of ephemera and popular or folk literature were published as chapbooks, such as almanacs, children’s literature, folk tales, nursery rhymes, pamphlets, poetry, and political and religious tracts.[33]

The term «chapbook» for this type of literature was coined in the 19th century. The corresponding French and German terms are bibliothèque bleue (blue book) and Volksbuch, respectively.[34][35][36] The principal historical subject matter of chapbooks was abridgements of ancient historians, popular medieval histories of knights, stories of comical heroes, religious legends, and collections of jests and fables.[37] The new printed books reached the households of urban citizens and country merchants who visited the cities as traders. Cheap printed histories were, in the 17th and 18th centuries, especially popular among apprentices and younger urban readers of both sexes.[38]

The early modern market, from the 1530s and 1540s, divided into low chapbooks and high market expensive, fashionable, elegant belles lettres. The Amadis and Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel were important publications with respect to this divide. Both books specifically addressed the new customers of popular histories, rather than readers of belles lettres. The Amadis was a multi–volume fictional history of style, that aroused a debate about style and elegance as it became the first best-seller of popular fiction. On the other hand, Gargantua and Pantagruel, while it adopted the form of modern popular history, in fact satirized that genre’s stylistic achievements. The division, between low and high literature, became especially visible with books that appeared on both the popular and belles lettres markets in the course of the 17th and 18th centuries: low chapbooks included abridgments of books such as Don Quixote.

The term «chapbook» is also in use for present-day publications, commonly short, inexpensive booklets.[33]

Heroic romances[edit]

Heroic Romance is a genre of imaginative literature, which flourished in the 17th century, principally in France.

The beginnings of modern fiction in France took a pseudo-bucolic form, and the celebrated L’Astrée, (1610) of Honore d’Urfe (1568–1625), which is the earliest French novel, is properly styled a pastoral. Although its action was, in the main, languid and sentimental, there was a side of the Astree which encouraged that extravagant love of glory, that spirit of » panache», which was now rising to its height in France. That spirit it was which animated Marin le Roy de Gomberville (1603–1674), who was the inventor of what have since been known as the Heroical Romances. In these there was experienced a violent recrudescence of the old medieval elements of romance, the impossible valour devoted to a pursuit of the impossible beauty, but the whole clothed in the language and feeling and atmosphere of the age in which the books were written. In order to give point to the chivalrous actions of the heroes, it was always hinted that they were well-known public characters of the day in a romantic disguise.

Satirical romances[edit]

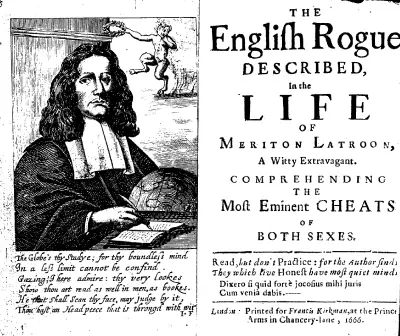

Stories of witty cheats were an integral part of the European novella with its tradition of fabliaux. Significant examples include Till Eulenspiegel (1510), Lazarillo de Tormes (1554), Grimmelshausen’s Simplicissimus Teutsch (1666–1668) and in England Richard Head’s The English Rogue (1665). The tradition that developed with these titles focused on a hero and his life. The adventures led to satirical encounters with the real world with the hero either becoming the pitiable victim or the rogue who exploited the vices of those he met.

A second tradition of satirical romances can be traced back to Heinrich Wittenwiler’s Ring (c. 1410) and to François Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel (1532–1564), which parodied and satirized heroic romances, and did this mostly by dragging them into the low realm of the burlesque. Don Quixote modified the satire of romances: its hero lost contact with reality by reading too many romances in the Amadisian tradition.

Other important works of the tradition are Paul Scarron’s Roman Comique (1651–57), the anonymous French Rozelli with its satire on Europe’s religions, Alain-René Lesage’s Gil Blas (1715–1735), Henry Fielding’s Joseph Andrews (1742) and Tom Jones (1749), and Denis Diderot’s Jacques the Fatalist (1773, printed posthumously in 1796).[39]

Histories[edit]

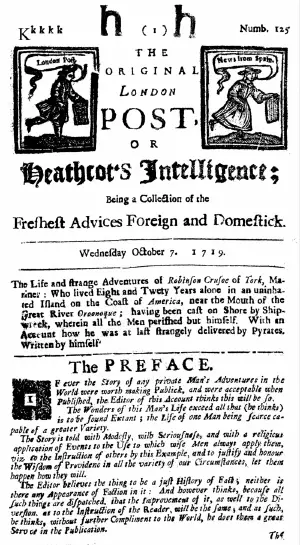

1719 newspaper reprint of Robinson Crusoe

A market of literature in the modern sense of the word, that is a separate market for fiction and poetry, did not exist until the late seventeenth century. All books were sold under the rubric of «History and politicks» in the early 18th century, including pamphlets, memoirs, travel literature, political analysis, serious histories, romances, poetry, and novels.

That fictional histories shared the same space with academic histories and modern journalism had been criticized by historians since the end of the Middle Ages: fictions were «lies» and therefore hardly justifiable at all. The climate, however, changed in the 1670s.

The romance format of the quasi–historical works of Madame d’Aulnoy, César Vichard de Saint-Réal,[40] Gatien de Courtilz de Sandras,[41] and Anne-Marguerite Petit du Noyer, allowed the publication of histories that dared not risk an unambiguous assertion of their truth. The literary market-place of the late 17th and early 18th century employed a simple pattern of options whereby fictions could reach out into the sphere of true histories. This permitted its authors to claim they had published fiction, not truth, if they ever faced allegations of libel.

Prefaces and title pages of seventeenth and early eighteenth century fiction acknowledged this pattern: histories could claim to be romances, but threaten to relate true events, as in the Roman à clef. Other works could, conversely, claim to be factual histories, yet earn the suspicion that they were wholly invented. A further differentiation was made between private and public history: Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe was, within this pattern, neither a «romance» nor a «novel». It smelled of romance, yet the preface stated that it should most certainly be read as a true private history.[42]

Cervantes and the modern novel[edit]

The rise of the modern novel as an alternative to the chivalric romance began with the publication of Miguel de Cervantes’ Novelas Exemplares (1613). It continued with Scarron’s Roman Comique (the first part of which appeared in 1651), whose heroes noted the rivalry between French romances and the new Spanish genre.[43]

Late 17th-century critics looked back on the history of prose fiction, proud of the generic shift that had taken place, leading towards the modern novel/novella.[44] The first perfect works in French were those of Scarron and Madame de La Fayette’s «Spanish history» Zayde (1670). The development finally led to her Princesse de Clèves (1678), the first novel with what would become characteristic French subject matter.[45][46]

Europe witnessed the generic shift in the titles of works in French published in Holland, which supplied the international market and English publishers exploited the novel/romance controversy in the 1670s and 1680s.[47] Contemporary critics listed the advantages of the new genre: brevity, a lack of ambition to produce epic poetry in prose; the style was fresh and plain; the focus was on modern life, and on heroes who were neither good nor bad.[48] The novel’s potential to become the medium of urban gossip and scandal fueled the rise of the novel/novella. Stories were offered as allegedly true recent histories, not for the sake of scandal but strictly for the moral lessons they gave. To prove this, fictionalized names were used with the true names in a separate key. The Mercure Gallant set the fashion in the 1670s.[49] Collections of letters and memoirs appeared, and were filled with the intriguing new subject matter and the epistolary novel grew from this and led to the first full blown example of scandalous fiction in Aphra Behn’s Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister (1684/ 1685/ 1687). Before the rise of the literary novel, reading novels had only been a form of entertainment.[50]

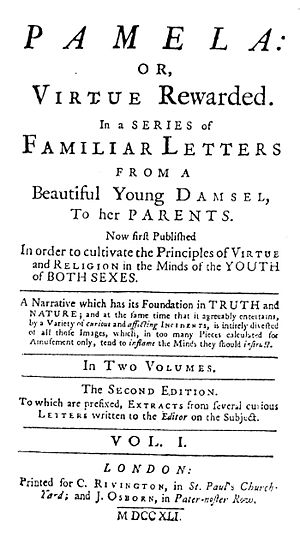

However, one of the earliest English novels, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719), has elements of the romance, unlike these novels, because of its exotic setting and story of survival in isolation. Crusoe lacks almost all of the elements found in these new novels: wit, a fast narration evolving around a group of young fashionable urban heroes, along with their intrigues, a scandalous moral, gallant talk to be imitated, and a brief, concise plot.[citation needed] The new developments did, however, lead to Eliza Haywood’s epic length novel, Love in Excess (1719/20) and to Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (1741).[citation needed] Some literary historians date the beginning of the English novel with Richardson’s Pamela, rather than Crusoe.[51]

18th-century novels[edit]

The idea of the «rise of the novel» in the 18th century is especially associated with Ian Watt’s influential study The Rise of the Novel (1957).[52][non-primary source needed] In Watt’s conception, a rise in fictional realism during the 18th century came to distinguish the novel from earlier prose narratives.[53]

Philosophical novel[edit]

The rising status of the novel in eighteenth century can be seen in the development of philosophical[54] and experimental novels.

Philosophical fiction was not exactly new. Plato’s dialogues were embedded in fictional narratives and his Republic is an early example of a Utopia. Ibn Tufail’s 12th century Philosophus Autodidacticus with its story of a human outcast surviving on an island, and the 13th century response by Ibn al-Nafis, Theologus Autodidactus are both didactic narrative works that can be thought of as early examples of a philosophical[55] and a theological novel,[56] respectively.

The tradition of works of fiction that were also philosophical texts continued with Thomas More’s Utopia (1516) and Tommaso Campanella’s City of the Sun (1602). However, the actual tradition of the philosophical novel came into being in the 1740s with new editions of More’s work under the title Utopia: or the happy republic; a philosophical romance (1743).[citation needed] Voltaire wrote in this genre in Micromegas: a comic romance, which is a biting satire on philosophy, ignorance, and the self-conceit of mankind (1752, English 1753). His Zadig (1747) and Candide (1759) became central texts of the French Enlightenment and of the modern novel.[citation needed]

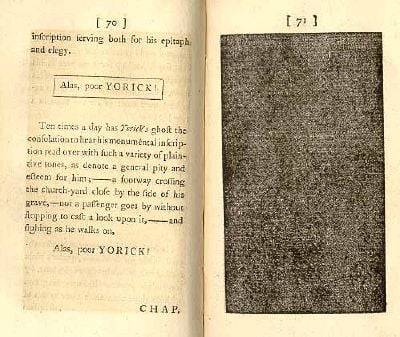

An example of the experimental novel is Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759–1767), with its rejection of continuous narration.[57] In it the author not only addresses readers in his preface but speaks directly to them in his fictional narrative. In addition to Sterne’s narrative experiments, there are visual experiments, such as a marbled page, a black page to express sorrow, and a page of lines to show the plot lines of the book. The novel as a whole focuses on the problems of language, with constant regard to John Locke’s theories in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.[58]

The romance genre in the 18th century[edit]

The rise of the word novel at the cost of its rival, the romance, remained a Spanish and English phenomenon, and though readers all over Western Europe had welcomed the novel(la) or short history as an alternative in the second half of the 17th century, only the English and the Spanish had openly discredited the romance.[citation needed]

But the change of taste was brief and Fénelon’s Telemachus [Les Aventures de Télémaque] (1699/1700) already exploited a nostalgia for the old romances with their heroism and professed virtue. Jane Barker explicitly advertised her Exilius as «A new Romance», «written after the Manner of Telemachus», in 1715.[59] Robinson Crusoe spoke of his own story as a «romance», though in the preface to the third volume, published in 1720, Defoe attacks all who said «that […] the Story is feign’d, that the Names are borrow’d, and that it is all a Romance; that there never were any such Man or Place».

The late 18th century brought an answer with the Romantic Movement’s readiness to reclaim the word romance, with the gothic romance, and the historical novels of Walter Scott. Robinson Crusoe now became a «novel» in this period, that is a work of the new realistic fiction created in the 18th century.[citation needed]

The sentimental novel[edit]

Sentimental novels relied on emotional responses, and feature scenes of distress and tenderness, and the plot is arranged to advance emotions rather than action. The result is a valorization of «fine feeling», displaying the characters as models of refined, sensitive emotional affect. The ability to display such feelings was thought at this time to show character and experience, and to help shape positive social life and relationships.[60]

An example of this genre is Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (1740), composed «to cultivate the Principles of Virtue and Religion in the Minds of the Youth of Both Sexes», which focuses on a potential victim, a heroine that has all the modern virtues and who is vulnerable because her low social status and her occupation as servant of a libertine who falls in love with her. She, however, ends in reforming her antagonist.[citation needed]

Male heroes adopted the new sentimental character traits in the 1760s. Laurence Sterne’s Yorick, the hero of the Sentimental Journey (1768) did so with an enormous amount of humour. Oliver Goldsmith’s Vicar of Wakefield (1766) and Henry Mackenzie’s Man of Feeling (1771) produced the far more serious role models.[citation needed]

These works inspired a sub- and counterculture of pornographic novels, for which Greek and Latin authors in translations had provided elegant models from the last century.[61] Pornography includes John Cleland’s Fanny Hill (1748), which offered an almost exact reversal of the plot of novels that emphasise virtue. The prostitute Fanny Hill learns to enjoy her work and establishes herself as a free and economically independent individual, in editions one could only expect to buy under the counter.[62]

Less virtuous protagonists can also be found in satirical novels, like Richard Head’s English Rogue (1665), that feature brothels, while women authors like Aphra Behn had offered their heroines alternative careers as precursors of the 19th-century femmes fatales.[63]

The genre evolves in the 1770s with, for example, Werther in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) realising that it is impossible for him to integrate into the new conformist society, and Pierre Choderlos de Laclos in Les Liaisons dangereuses (1782) showing a group of aristocrats playing games of intrigue and amorality.[citation needed].

[edit]

Changing cultural status[edit]

By around 1700, fiction was no longer a predominantly aristocratic entertainment, and printed books had soon gained the power to reach readers of almost all classes, though the reading habits differed and to follow fashions remained a privilege. Spain was a trendsetter into the 1630s but French authors superseded Cervantes, de Quevedo, and Alemán in the 1640s. As Huet was to note in 1670, the change was one of manners.[64] The new French works taught a new, on the surface freer, gallant exchange between the sexes as the essence of life at the French court.

The situation changed again from 1660s into the 1690s when works by French authors were published in Holland out of the reach of French censors.[65] Dutch publishing houses pirated fashionable books from France and created a new market of political and scandalous fiction. This led to a market of European rather than French fashions in the early 18th century.[66]

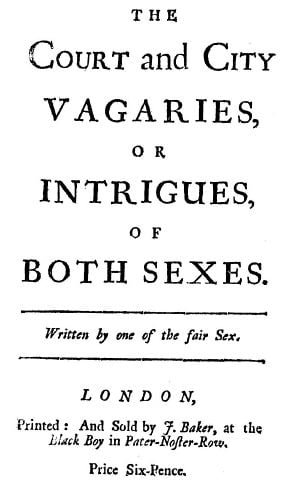

Intimate short stories: The Court and City Vagaries (1711).

By the 1680s fashionable political European novels had inspired a second wave of private scandalous publications and generated new productions of local importance. Women authors reported on politics and on their private love affairs in The Hague and in London. German students imitated them to boast of their private amours in fiction.[67] The London, the anonymous international market of the Netherlands, publishers in Hamburg and Leipzig generated new public spheres.[68] Once private individuals, such as students in university towns and daughters of London’s upper class began to write novels based on questionable reputations, the public began to call for a reformation of manners.[69]

An important development in Britain, at the beginning of the century, was that new journals like The Spectator and The Tatler reviewed novels. In Germany Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s Briefe, die neuste Literatur betreffend (1758) appeared in the middle of the century with reviews of art and fiction. By the 1780s such reviews played had an important role in introducing new works of fiction to the public.

Influenced by the new journals, reform became the main goal of the second generation of eighteenth century novelists. The Spectator Number 10 had stated that the aim was now «to enliven morality with wit, and to temper wit with morality […] to bring philosophy out of the closets and libraries, schools and colleges, to dwell in clubs and assemblies, at tea-tables and coffeehouses»). Constructive criticism of novels had until then been rare.[70] The first treatise on the history of the novel was a preface to Marie de La Fayette’s novel Zayde (1670).

A much later development was the introduction of novels into school and later university curricula.[when?]

The acceptance of novels as literature[edit]

The French churchman and scholar Pierre Daniel Huet’s Traitté de l’origine des romans (1670) laid the ground for a greater acceptance of the novel as literature, that is comparable to the classics, in the early 18th century. The theologian had not only dared to praise fictions, but he had also explained techniques of theological interpretation of fiction, which was a novelty. Furthermore, readers of novels and romances could gain insight not only into their own culture, but also that of distant, exotic countries.[citation needed]

When the decades around 1700 saw the appearance of new editions of the classical authors Petronius, Lucian, and Heliodorus of Emesa.[71] the publishers equipped them with prefaces that referred to Huet’s treatise. and the canon it had established. Also exotic works of Middle Eastern fiction entered the market that gave insight into Islamic culture. The Book of One Thousand and One Nights was first published in Europe from 1704 to 1715 in French, and then translated immediately into English and German, and was seen as a contribution to Huet’s history of romances.[72]

The English, Select Collection of Novels in six volumes (1720–22), is a milestone in this development of the novel’s prestige. It included Huet’s Treatise, along with the European tradition of the modern novel of the day: that is, novella from Machiavelli’s to Marie de La Fayette’s masterpieces. Aphra Behn’s novels had appeared in the 1680s but became classics when reprinted in collections. Fénelon’s Telemachus (1699/1700) became a classic three years after its publication. New authors entering the market were now ready to use their personal names rather than pseudonyms, including Eliza Haywood, who in 1719 following in the footsteps of Aphra Behn used her name with unprecedented pride.

19th-century novels[edit]

Romanticism[edit]

The very word romanticism is connected to the idea of romance, and the romance genre experienced a revival, at the end of the 18th century, with gothic fiction, that began in 1764 with Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, subtitled (in its second edition) «A Gothic Story».[73] Subsequent important gothic works are Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and ‘Monk’ Lewis’s The Monk (1795).

The new romances challenged the idea that the novel involved a realistic depiction of life, and destabilized the difference the critics had been trying to establish, between serious classical art and popular fiction. Gothic romances exploited the grotesque,[74] and some critics thought that their subject matter deserved less credit than the worst medieval tales of Arthurian knighthood.[75]

The authors of this new type of fiction were accused of exploiting all available topics to thrill, arouse, or horrify their audience. These new romantic novelists, however, claimed that they were exploring the entire realm of fictionality. And psychological interpreters, in the early 19th century, read these works as encounters with the deeper hidden truth of the human imagination: this included sexuality, anxieties, and insatiable desires. Under such readings, novels were described as exploring deeper human motives, and it was suggested that such artistic freedom would reveal what had not previously been openly visible.

The romances of de Sade, Les 120 Journées de Sodome (1785), Poe’s Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1840), Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (1818), and E.T.A. Hoffmann, Die Elixiere des Teufels (1815), would later attract 20th-century psychoanalysts and supply the images for 20th- and 21st-century horror films, love romances, fantasy novels, role-playing computer games, and the surrealists.

The historical romance was also important at this time. But, while earlier writers of these romances paid little attention to historical reality, Walter Scott’s historical novel Waverley (1814) broke with this tradition, and he invented «the true historical novel».[76] At the same time he was influenced by gothic romance, and had collaborated in 1801 with ‘Monk’ Lewis on Tales of Wonder.[76] With his Waverley novels Scott «hoped to do for the Scottish border» what Goethe and other German poets «had done for the Middle Ages, «and make its past live again in modern romance».[77] Scott’s novels «are in the mode he himself defined as romance, ‘the interest of which turns upon marvelous and uncommon incidents'».[78] He used his imagination to re-evaluate history by rendering things, incidents and protagonists in the way only the novelist could do. His work remained historical fiction, yet it questioned existing historical perceptions. The use of historical research was an important tool: Scott, the novelist, resorted to documentary sources as any historian would have done, but as a romantic he gave his subject a deeper imaginative and emotional significance.[78] By combining research with «marvelous and uncommon incidents», Scott attracted a far wider market than any historian could, and was the most famous novelist of his generation, throughout Europe.[76]

The Victorian period: 1837–1901[edit]

In the 19th century the relationship between authors, publishers, and readers, changed. Authors originally had only received payment for their manuscript, however, changes in copyright laws, which began in 18th and continued into the 19th century[79] promised royalties on all future editions. Another change in the 19th century was that novelists began to read their works in theaters, halls, and bookshops.[80] Also during the nineteenth century the market for popular fiction grew, and competed with works of literature. New institutions like the circulating library created a new market with a mass reading public.[81]

Another difference was that novels began to deal with more difficult subjects, including current political and social issues, that were being discussed in newspapers and magazines. The idea of social responsibility became a key subject, whether of the citizen, or of the artist, with the theoretical debate concentrating on questions around the moral soundness of the modern novel.[82] Questions about artistic integrity, as well as aesthetics, including, for example. the idea of «art for art’s sake», proposed by writers like Oscar Wilde and Algernon Charles Swinburne, were also important.[83]

Major British writers such as Charles Dickens[84] and Thomas Hardy[85] were influenced by the romance genre tradition of the novel, which had been revitalized during the Romantic period. The Brontë sisters were notable mid-19th-century authors in this tradition, with Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre and Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights.[86] Publishing at the very end of the 19th century, Joseph Conrad has been called «a supreme ‘romancer.'»[87] In America «the romance … proved to be a serious, flexible, and successful medium for the exploration of philosophical ideas and attitudes.» Notable examples include Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, and Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick.[88]

A number of European novelists were similarly influenced during this period by the earlier romance tradition, along with the Romanticism, including Victor Hugo, with novels like The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) and Les Misérables (1862), and Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov with A Hero of Our Time (1840).

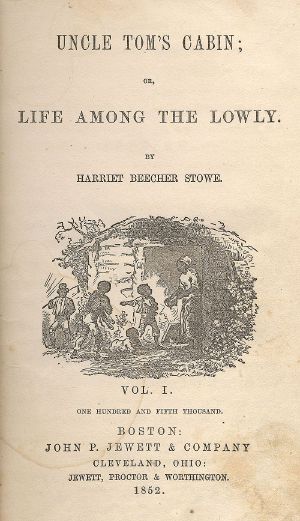

Many 19th-century authors dealt with significant social matters.[89] Émile Zola’s novels depicted the world of the working classes, which Marx and Engels’s non-fiction explores. In the United States slavery and racism became topics of far broader public debate thanks to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), which dramatizes topics that had previously been discussed mainly in the abstract. Charles Dickens’ novels led his readers into contemporary workhouses, and provided first-hand accounts of child labor. The treatment of the subject of war changed with Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1868/69), where he questions the facts provided by historians. Similarly the treatment of crime is very different in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866), where the point of view is that of a criminal. Women authors had dominated fiction from the 1640s into the early 18th century, but few before George Eliot so openly questioned the role, education, and status of women in society, as she did.

As the novel became a platform of modern debate, national literatures were developed that link the present with the past in the form of the historical novel. Alessandro Manzoni’s I Promessi Sposi (1827) did this for Italy, while novelists in Russia and the surrounding Slavonic countries, as well as Scandinavia, did likewise.

Along with this new appreciation of history, the future also became a topic for fiction. This had been done earlier in works like Samuel Madden’s Memoirs of the Twentieth Century (1733) and Mary Shelley’s The Last Man (1826), a work whose plot culminated in the catastrophic last days of a mankind extinguished by the plague. Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1887) and H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine (1895) were concerned with technological and biological developments. Industrialization, Darwin’s theory of evolution and Marx’s theory of class divisions shaped these works and turned historical processes into a subject of wide debate. Bellamy’s Looking Backward became the second best-selling book of the 19th century after Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.[90][91] Such works led to the development of a whole genre of popular science fiction as the 20th century approached.

20th century[edit]

Modernism and post-modernism[edit]

James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) had a major influence on modern novelists, in the way that it replaced the 18th- and 19th-century narrator with a text that attempted to record inner thoughts, or a «stream of consciousness». This term was first used by William James in 1890 and, along with the related term interior monologue, is used by modernists like Dorothy Richardson, Marcel Proust, Virginia Woolf, and William Faulkner.[92] Also in the 1920s expressionist Alfred Döblin went in a different direction with Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929), where interspersed non-fictional text fragments exist alongside the fictional material to create another new form of realism, which differs from that of stream-of-consciousness.

Later works like Samuel Beckett’s trilogy Molloy (1951), Malone Dies (1951) and The Unnamable (1953), as well as Julio Cortázar’s Rayuela (1963) and Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) all make use of the stream-of-consciousness technique. On the other hand, Robert Coover is an example of those authors who, in the 1960s, fragmented their stories and challenged time and sequentiality as fundamental structural concepts.

The 20th century novel deals with a wide range of subject matter. Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1928) focusses on a young German’s experiences of World War I. The Jazz Age is explored by American F. Scott Fitzgerald, and the Great Depression by fellow American John Steinbeck. Totalitarianism is the subject of British writer George Orwell’s most famous novels. Existentialism is the focus of two writers from France: Jean-Paul Sartre with Nausea (1938) and Albert Camus with The Stranger (1942). The counterculture of the 1960s, with its exploration of altered states of consciousness, led to revived interest in the mystical works of Hermann Hesse, such as Steppenwolf (1927), and produced iconic works of its own, for example Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. Novelists have also been interested in the subject of racial and gender identity in recent decades.[93] Jesse Kavadlo of Maryville University of St. Louis has described Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club (1996) as «a closeted feminist critique».[94] Virginia Woolf, Simone de Beauvoir, Doris Lessing, Elfriede Jelinek were feminist voices during this period.

Furthermore, the major political and military confrontations of the 20th and 21st centuries have also influenced novelists. The events of World War II, from a German perspective, are dealt with by Günter Grass’ The Tin Drum (1959) and an American by Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (1961). The subsequent Cold War influenced popular spy novels. Latin American self-awareness in the wake of the leftist revolutions of the 1960s and 1970s resulted in a «Latin American Boom», linked to the names of novelists Julio Cortázar, Mario Vargas Llosa, Carlos Fuentes and Gabriel García Márquez, along with the invention of a special brand of postmodern magic realism.

Another major 20th-century social event, the so-called sexual revolution is reflected in the modern novel.[95] D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover had to be published in Italy in 1928 with British censorship only lifting its ban as late as 1960. Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer (1934) created a comparable US scandal. Transgressive fiction from Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1955) to Michel Houellebecq’s Les Particules élémentaires (1998) pushed the boundaries, leading to the mainstream publication of explicitly erotic works such as Anne Desclos’ Story of O (1954) and Anaïs Nin’s Delta of Venus (1978).

In the second half of the 20th century, Postmodern authors subverted serious debate with playfulness, claiming that art could never be original, that it always plays with existing materials.[96] The idea that language is self-referential was already an accepted truth in the world of pulp fiction. A postmodernist re-reads popular literature as an essential cultural production. Novels from Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), to Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose (1980) and Foucault’s Pendulum (1989) made use of intertextual references.[97]

Genre fiction[edit]

While the reader of so-called serious literature will follow public discussions of novels, popular fiction production employs more direct and short-term marketing strategies by openly declaring a work’s genre. Popular novels are based entirely on the expectations for the particular genre, and this includes the creation of a series of novels with an identifiable brand name. e.g. the Sherlock Holmes series by Arthur Conan Doyle.

Popular literature holds a larger market share. Romance fiction had an estimated $1.375 billion share in the US book market in 2007. Inspirational literature/religious literature followed with $819 million, science fiction/fantasy with $700 million, mystery with $650 million and then classic literary fiction with $466 million.[98]

Genre literature might be seen as the successor of the early modern chapbook. Both fields share a focus on readers who are in search of accessible reading satisfaction.[99] The twentieth century love romance is a successor of the novels Madeleine de Scudéry, Marie de La Fayette, Aphra Behn, and Eliza Haywood wrote from the 1640s into the 1740s. The modern adventure novel goes back to Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) and its immediate successors. Modern pornography has no precedent in the chapbook market but originates in libertine and hedonistic belles lettres, of works like John Cleland’s Fanny Hill (1749) and similar eighteenth century novels. Ian Fleming’s James Bond is a descendant of the anonymous yet extremely sophisticated and stylish narrator who mixed his love affairs with his political missions in La Guerre d’Espagne (1707). Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon is influenced by Tolkien, as well as Arthurian literature, including its nineteenth century successors. Modern horror fiction also has no precedent on the market of chapbooks but goes back to the elitist market of early nineteenth century Romantic literature. Modern popular science fiction has an even shorter history, from the 1860s.

The authors of popular fiction tend to advertise that they have exploited a controversial topic and this is a major difference between them and so-called elitist literature. Dan Brown, for example, discusses, on his website, the question whether his Da Vinci Code is an anti-Christian novel.[100] And because authors of popular fiction have a fan community to serve, they can risk offending literary critics. However, the boundaries between popular and serious literature have blurred in recent years, with postmodernism and poststructuralism, as well as by adaptation of popular literary classics by the film and television industries.

Crime became a major subject of 20th and 21st century genre novelists and crime fiction reflects the realities of modern industrialized societies. Crime is both a personal and public subject: criminals each have their personal motivations; detectives, see their moral codes challenged. Patricia Highsmith’s thrillers became a medium of new psychological explorations. Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy (1985–1986) is an example of experimental postmodernist literature based on this genre.

Fantasy is another major area of commercial fiction, and a major example is J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (1954/55), a work originally written for young readers that became a major cultural artefact. Tolkien in fact revived the tradition of European epic literature in the tradition of Beowulf, the North Germanic Edda and the Arthurian Cycles.

Science fiction is another important type of genre fiction and has developed in a variety of ways, ranging from the early, technological adventure Jules Verne had made fashionable in the 1860s, to Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) about Western consumerism and technology. George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) deals with totalitarianism and surveillance, among other matters, while Stanisław Lem, Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke produced modern classics which focus on the interaction between humans and machines. The surreal novels of Philip K Dick such as The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch explore the nature of reality, reflecting the widespread recreational experimentation with drugs and cold-war paranoia of the 60’s and 70’s. Writers such as Ursula le Guin and Margaret Atwood explore feminist and broader social issues in their works. William Gibson, author of the cult classic Neuromancer (1984), is one of a new wave of authors who explore post-apocalyptic fantasies and virtual reality.

21st century[edit]

Non-traditional formats[edit]

A major development in this century has been novels published as ebooks, and the growth of web fiction, which is available primarily or solely on the Internet. A common type is the web serial: unlike most modern novels, web fiction novels are frequently published in parts over time. Ebooks are often published with a paper version. Audio books (a recording of a book reading) have also become common this century.

Another non-traditional format, popular in the 21st century, is the graphic novel. However, though a graphic novel may be «a fictional story that is presented in comic-strip format and published as a book»,[101] it can also refers to non-fiction and collections of short works.[102][103] While the term graphic novel was coined in the 1960s[104][105] there were precursors in the 19th century.[106] The author John Updike, when he spoke to the Bristol Literary Society in 1969, on «the death of the novel», declared that he saw «no intrinsic reason why a doubly talented artist might not arise and create a comic strip novel masterpiece».[107] A popular Japanese version of the graphic novel can be found in manga, and such works of fiction can be published in online versions.

Audiobooks have been available since the 1930s in schools and public libraries, and to a lesser extent in music shops. Since the 1980s this medium has become more widely available, including more recently online.[108]

Web fiction is especially popular in China, with revenues topping US$2.5 billion,[109] as well as in South Korea. Online literature such as web fiction inside China has over 500 million readers,[110] therefore, online literature in China plays a much more important role than in the United States and the rest of the world.[111] Most books are available online, where the most popular novels find millions of readers. Joara is S. Korea’s largest web novel platform with 140,000 writers, with an average of 2,400 serials per day and 420,000 works. The company posted 12.5 billion won in sales in 2015 as profits were generated from 2009. Its membership is 1.1 million, and it uses 8.6 million cases a day on average (2016).[112] Since Joara’s users have almost the same gender ratio, both fantasy and romance forms of genre fiction are in high demand.[113]

The development of ebooks and web novels has led to a rapid expansion of self-published works in recent years.[114] Some authors who self-publish can make more money than through a traditional publisher.[115]

However, despite the challenges from digital media print remains «the most popular book format among U.S. consumers, with more than 60 percent of adults having read a print book in the last twelve months».[116]

See also[edit]

- Chain novel

- Children’s literature; Young adult fiction

- Collage novel

- Gay literature

- Graphic novel

- Light novel

- Nautical fiction

- Novel in Scotland

- Proletarian novel

- Psychological novel

- Sociology of literature

- Social novel

- War novel

References[edit]

- ^ Britannica Online Encyclopedia [1] accessed 2 August 2009

- ^ The Scarlet Letter: A Romance

- ^ Melville described Moby Dick to his English publisher as «a romance of adventure, founded upon certain wild legends in the Southern Sperm Whale Fisheries,» and promised it would be done by the fall. Herman Melville in Horth, Lynn, ed. (1993). Correspondence. The Writings of Herman Melville. Vol. Fourteen. Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press and The Newberry Library. ISBN 0-8101-0995-6.

- ^ William Harmon & C, Hugh Holmam, A Handbook to Literature (7th edition), p. 237.

- ^ See A Glastonbury Romance.

- ^ Margaret Anne Doody, The True Story of the Novel. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996, rept. 1997, p. 1. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ J. A. Cuddon, Dictionary of Literary Terms & Literary Theory, ed., 4th edition, revised C. E. Preston. London: Penguin, 1999, pp. 76o-2.

- ^ M. H. Abrams, A Glossary of Literary Terms (7th edition), p. 192.

- ^ «Essay on Romance», Prose Works volume vi, p. 129, quoted in «Introduction» to Walter Scott’s Quentin Durward, ed. Susan Maning. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992, p. xxv.

- ^ See also, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s, «Preface» to The House of Seven Gables: A Romance, 1851. External link to the «Preface» below)

- ^ Grossman, Lev (8 January 2010). «All-TIME 100 Novels». TIME.

- ^ «To Kill a Mockingbird voted greatest novel of all time». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11.

- ^ «The 100 best novels: No 8 – Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1818)». The Guardian. 11 November 2013.

- ^ «Hayy ibn Yaqzan | Encyclopedia.com». www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2020-05-02.

- ^ a b Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia of Literature. Kathleen Kuiper, ed. 1995. Merriam-Webster, Springfield, Mass.

- ^ Doody (1996), pp. 18–3, 187.

- ^ Doody (1996), p. 187.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (2002). Genius: A Mosaic of One Hundred Exemplary Creative Minds. Fourth Estate. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-84115-398-8. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ György Lukács The Theory of the Novel. A historico-philosophical essay on the forms of great epic literature [first German edition 1920], transl. by Anna Bostock (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1971).

- ^ Artistic and Architectural Index—An archive of the Internet Archive of Fiction, archived on 2011-11-24

- ^ Đỗ Thu Hiền (2021) Definition of novel, biography and narrative prose in medieval Vietnam. Journal of Literature Researches, No. 6. In Vietnamese

- ^ Trần Nghĩa, Hán-Nôm Journal Issue 3 (32), 1997, Classification of Vietnamese novel in Hán script (in Vietnamese)

- ^ Lê Thanh Sơn. Modernization tendency in Tản Đà’s literature works, from the categorization aspecy UED Journal of Social Sciences, Humanities & Education, 2020 (in Vietnamese)

- ^ Lý Lan và chuyện «bé mọn» của thế giới đàn bà

- ^ Nhận thức thể loại của nhà văn Nam Bộ giai đoạn 1945 — 1954

- ^ Morgan, J. R. (2019). «Foreword to the 2008 edition». In Reardon, B. P. (ed.). Collected Ancient Greek Novels (3rd ed.). Oakland, CA: University of California Press. p. xvi. ISBN 978-0-520-30559-5.

- ^ John Robert Morgan, Richard Stoneman, Greek fiction: the Greek novel in context (Routledge, 1994), Gareth L. Schmeling, and Tim Whitmarsh (hrsg.) The Cambridge companion to the Greek and Roman novel (Cambridge University Press 2008).

- ^ «Printing press | History & Types».

- ^ «Chivalric romance», in Chris Baldick, ed., Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms, 3rd ed. (Oxford University Press, 2008).

- ^ See William Caxton’s preface to his 1485 edition.

- ^ C.S. Lewis, The Discarded Image, p. 9 ISBN 0-521-47735-2

- ^ The ESTC notes 29 editions published between 1496 and 1785 ESTC search result

- ^ a b «Chapbooks: Definition and Origins». Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ From chapmen, chap, a variety of peddler, which folks circulated such literature as part of their stock.

- ^ Spufford, Margaret (1984). The Great Reclothing of Rural England. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-0-907628-47-7.

- ^ Leitch, R. (1990). «‘Here Chapman Billies Take Their Stand’: A Pilot Study of Scottish Chapmen, Packmen and Pedlars». Proceedings of the Scottish Society of Antiquarians 120. pp. 173–88.

- ^ See Rainer Schöwerling, Chapbooks. Zur Literaturgeschichte des einfachen Lesers. Englische Konsumliteratur 1680–1840 (Frankfurt, 1980), Margaret Spufford, Small Books and Pleasant Histories. Pleasant Fiction and its Readership in Seventeenth-Century England (London, 1981) and Tessa Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety 1550–1640 (Cambridge, 1990).

- ^ See Johann Friedrich Riederer German satire on the widespread reading of novels and romances: «Satyra von den Liebes-Romanen», in: Die abentheuerliche Welt in einer Pickelheerings-Kappe, vol. 2 (Nürnberg, 1718) online edition

- ^ Compare also: Günter Berger, Der komisch-satirische Roman und seine Leser. Poetik, Funktion und Rezeption einer niederen Gattung im Frankreich des 17. Jahrhunderts (Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, 1984), Ellen Turner Gutiérrez The reception of the picaresque in the French, English, and German traditions (P. Lang, 1995), and Frank Palmeri, Satire, History, Novel: Narrative Forms, 1665–1815 (University of Delaware Press, 2003).

- ^ See his Dom Carlos, nouvelle histoire (Amsterdam, 1672) and the recent dissertation by Chantal Carasco, Saint-Réal, romancier de l’histoire: une cohérence esthéthique et morale (Nantes, 2005).

- ^ Jean Lombard, Courtilz de Sandras et la crise du roman à la fin du Grand Siècle (Paris: PUF, 1980).

- ^ Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe (London: William Taylor, 1719)

- ^ See Paul Scarron, The Comical Romance, Chapter XXI. «Which perhaps will not be found very Entertaining» (London, 1700) with its call for the new genre. online edition

- ^ See [Du Sieur,] «Sentimens sur l’histoire» in: Sentimens sur les lettres et sur l’histoire, avec des scruples sur le stile (Paris: C. Blageart, 1680) online edition and Camille Esmein’s Poétiques du roman. Scudéry, Huet, Du Plaisir et autres textes théoriques et critiques du XVIIe siècle sur le genre romanesque (Paris, 2004).

- ^ «La Princesse de Clèves NOVEL BY LA FAYETTE»,»www.britannica.com»,

- ^ «The Princess Of Cleves»,»www.espacefrancais.com»,

- ^ See Robert Ignatius Letellier, The English novel, 1660–1700: an annotated bibliography (Greenwood Publishing Group, 1997).

- ^ See the preface to The Secret History of Queen Zarah (Albigion, 1705)– the English version of Abbe Bellegarde, «Lettre à une Dame de la Cour, qui lui avoit demandé quelques Reflexions sur l’Histoire» in: Lettres curieuses de littérature et de morale (La Haye: Adrian Moetjens, 1702) online edition

- ^ DeJean, Joan. The Essence of Style: How the French Invented Fashion, Fine Food, Chic Cafés, Style, Sophistication, and Glamour (New York: Free Press, 2005).

- ^ Warner, William B. Preface From a Literary to a Cultural History of the Early Novel In: Licensing Entertainment – The Elevation of Novel Reading in Britain, 1684–1750 University of California Press, Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford: 1998.

- ^ Cevasco, George A. Pearl Buck and the Chinese Novel, p. 442. Asian Studies – Journal of Critical Perspectives on Asia, 1967, 5:3, pp. 437–51.

- ^ Ian Watt’s, The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding (London, 1957).

- ^ The Rise of the Novel (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1963), p. 10.

- ^ See Jonathan Irvine Israel, Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650–1750 (Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 591–599, Roger Pearson, The fables of reason: a study of Voltaire’s «Contes philosophiques» (Oxford University Press 1993), Dena Goodman, Criticism in action: Enlightenment experiments in political writing (Cornell University Press 1989), Robert Francis O’Reilly, The Artistry of Montesquieu’s Narrative Tales (University of Wisconsin., 1967), and René Pomeau and Jean Ehrard, De Fénelon à Voltaire (Flammarion, 1998).

- ^ Samar Attar, The Vital Roots of European Enlightenment: Ibn Tufayl’s Influence on Modern Western Thought, Lexington Books,[ISBN missing].

- ^ Muhsin Mahdi (1974), «The Theologus Autodidactus of Ibn at-Nafis by Max Meyerhof, Joseph Schacht»,

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica [2].

- ^ Griffin, Robert J. (1961). «Tristram Shandy and Language». College English. 23 (2): 108–12. doi:10.2307/372959. JSTOR 372959.

- ^ See the preface to her Exilius (London: E. Curll, 1715)

- ^ Richard Maxwell and Katie Trumpener, eds., The Cambridge Companion to Fiction in the Romantic Period (2008).

- ^ The elegant and clearly fashionable edition of The Works of Lucian (London: S. Briscoe/ J. Woodward/ J. Morphew, 1711), would thus include the story of «Lucian’s Ass», vol.1 pp. 114–43.

- ^ See Robert Darnton, The Forbidden Best-Sellers of Pre-Revolutionary France (New York: Norton, 1995), Lynn Hunt, The Invention of Pornography: Obscenity and the Origins of Modernity, 1500–1800 (New York: Zone, 1996), Inger Leemans, Het woord is aan de onderkant: radicale ideeën in Nederlandse pornografische romans 1670–1700 (Nijmegen: Vantilt, 2002), and Lisa Z. Sigel, Governing Pleasures: Pornography and Social Change in England, 1815–1914 (January: Scholarly Book Services Inc, 2002).

- ^ Aphra Behn’s Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister (1684/ 1685/ 1687)

- ^ Pierre Daniel Huet, The History of Romances, transl. by Stephen Lewis (London: J. Hooke/ T. Caldecott, 1715), pp. 138–140.

- ^ See for the following: Christiane Berkvens-Stevelinck, H. Bots, P.G. Hoftijzer (eds.), Le Magasin de L’univers: The Dutch Republic as the Centre of the European Book Trade: Papers Presented at the International Colloquium, Held at Wassenaar, 5–7 July 1990 (Leiden/ Boston, MA: Brill, 1992).

- ^ See also the article on Pierre Marteau for a profile of the European production of (not only) political scandal.

- ^ See George Ernst Reinwalds Academien- und Studenten-Spiegel (Berlin: J.A. Rüdiger, 1720), pp. 424–427 and the novels written by such «authors» as Celander, Sarcander, and Adamantes at the beginning of the 18th century.

- ^ Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry Into a Category of the Bourgeois Society [1962], translated by Thomas Burger (MIT Press, 1991).

- ^ See the Entertainments pp. 74–77, Jane Barker’s preface to her Exilius (London: E. Curll, 1715), and George Ernst Reinwalds Academien- und Studenten-Spiegel (Berlin: J.A. Rüdiger, 1720), pp. 424–27.

- ^ See Hugh Barr Nisbet, Claude Rawson (eds.), The Cambridge history of literary criticism, vol. IV (Cambridge University Press 1997); and Ernst Weber, Texte zur Romantheorie: (1626–1781), 2 vols. (München: Fink, 1974/ 1981) and the individual volumes of Dennis Poupard (et al.), Literature Criticism from 1400 to 1800: (Detroit, Mich.: Gale Research Co, 1984 ff.).

- ^ The Works of T. Petronius Arbiter […] second edition […] (London: S. Briscoe/ J. Woodward/ J. Morphew, 1710); The Works of Lucian,, 2 vols. (London: S. Briscoe/ J. Woodward/ J. Morphew, 1711). See The Adventures of Theagenes and Chariclia […], 2 vols. (London: W. Taylor/ E. Curll/ R. Gosling/ J. Hooke/ J. Browne/ J. Osborn, 1717),

- ^ August Bohse’s (alias Talander) «Preface» to the German edition. (Leipzig: J.L. Gleditsch/ M.G. Weidmann, 1710).

- ^ «The Castle of Otranto: The creepy tale that launched gothic fiction». BBC. 13 December 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ See Geoffrey Galt Harpham, On the Grotesque: Strategies of Contradiction in Art and Literature, 2nd ed. (Davies Group, Publishers, 2006).

- ^ See Gerald Ernest Paul Gillespie, Manfred Engel, and Bernard Dieterle, Romantic prose fiction (John Benjamin’s Publishing Company, 2008).

- ^ a b c The Bloomsbury Guide to English Literature, ed. Marion Wynne Davis. New York: Prentice Hall, 1990, p. 885.

- ^ The Bloomsbury Guide to English Literature, ed. Marion Wynne Davis, p. 884.

- ^ a b The Norton Anthology of English Literature, vol.2, 7th edition, ed. M.H. Abrams. New York: Norton, 2000, pp. 20–21.

- ^ See Mark Rose, Authors and Owners: The Invention of Copyright 3rd ed. (Harvard University Press, 1993) and Joseph Lowenstein, The Author’s Due: Printing and the Prehistory of Copyright (University of Chicago Press, 2002)

- ^ See Susan Esmann, «Die Autorenlesung – eine Form der Literaturvermittlung», Kritische Ausgabe 1/2007 PDF; 0,8 MB Archived 2009-02-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ See Richard Altick and Jonathan Rose, The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800–1900, 2nd ed. (Ohio State University Press, 1998) and William St. Clair, The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period (Cambridge: CUP, 2004).

- ^ See: James Engell, The committed word: Literature and Public Values (Penn State Press, 1999) and Edwin M. Eigner, George John Worth (ed.), Victorian criticism of the novel (Cambridge: CUP Archive, 1985).

- ^ Gene H. Bell-Villada, Art for Art’s Sake & Literary Life: How Politics and Markets Helped Shape the Ideology & Culture of Aestheticism, 1790–1990 (University of Nebraska Press, 1996).

- ^ Arthur C. Benson, «Charles Dickens». The North American Review, Vol. 195, No. 676 (Mar., 1912), pp. 381–91.

- ^ Jane Millgate, «Two Versions of Regional Romance: Scott’s The Bride of Lammermoor and Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles. Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900, Vol. 17, No. 4, Nineteenth Century (Autumn, 1977), pp. 729–38.

- ^ Lucasta Miller, The Brontë Myth. London: Vintage, 2002.

- ^ Dictionary of Literary Terms & Literary Theory, ed. J.A. Cuddon, 4th ed., revised C.E. Preston (1999), p. 761.

- ^ A Handbook of Literary Terms, 7th edition, ed. Harmon and Holman (1995), p. 450.

- ^ For the wider context of 19th-century encounters with history see: Hayden White, Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1977).

- ^ See Scott Donaldson and Ann Massa American Literature: Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries (David & Charles, 1978), p. 205.

- ^ Claire Parfait, The Publishing History of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 1852–2002 (Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2007).

- ^ See Erwin R. Steinberg (ed.) The Stream-of-consciousness technique in the modern novel (Port Washington, N.Y: Kennikat Press, 1979). On the extra-European usage of the technique see also: Elly Hagenaar/ Eide, Elisabeth, «Stream of consciousness and free indirect discourse in modern Chinese literature», Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 56 (1993), p. 621 and P.M. Nayak (ed.), The voyage inward: stream of consciousness in Indian English fiction (New Delhi: Bahri Publications, 1999).

- ^ See, for example, Susan Hopkins, Girl Heroes: The New Force In Popular Culture (Annandale NSW:, 2002).

- ^ Kavadlo, Jesse (Fall–Winter 2005). «The Fiction of Self-destruction: Chuck Palahniuk, Closet Moralist». Stirrings Still: The International Journal of Existential Literature. 2 (2): 7.

- ^ See: Charles Irving Glicksberg, The Sexual Revolution in Modern American Literature (Nijhoff, 1971) and his The Sexual Revolution in Modern English Literature (Martinus Nijhoff, 1973).

- ^ See for a first survey Brian McHale, Postmodernist Fiction (Routledge, 1987) and John Docker, Postmodernism and popular culture: a cultural history (Cambridge University Press, 1994).

- ^ See Gérard Genette, Palimpsests, trans. Channa Newman & Claude Doubinsky (Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press) and Graham Allan, Intertextuality (London/New York: Routledge, 2000); Linda Hutcheon, Narcissistic Narrative. The Metafictional Paradox (London: Routledge, 1984) and Patricia Waugh, Metafiction. The Theory and Practice of Self-conscious Fiction (London: Routledge 1988).

- ^ See the page Romance Literature Statistics: Overview Archived 2007-12-23 at the Wayback Machine (visited March 16, 2009) of Romance Writers of America Archived 2010-12-03 at the Wayback Machine homepage. The subpages offer further statistics for the years since 1998.

- ^ John J. Richetti Popular Fiction before Richardson. Narrative Patterns 1700–1739 (Oxford: OUP, 1969).

- ^ Dan Brown on his website visited February 3, 2009. Archived January 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «graphic novel». Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Goldsmith, Francisca (2005). Graphic Novels Now: Building, Managing, And Marketing a Dynamic Collection. American Library Association. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8389-0904-1.

- ^ Karp, Jesse; Kress, Rush (2011). Graphic Novels in Your School Library. American Library Association. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-0-8389-1089-4.

- ^ Schelly, Bill (2010). Founders of Comic Fandom: Profiles of 90 Publishers, Dealers, Collectors, Writers, Artists and Other Luminaries of the 1950s and 1960s. McFarland. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-7864-5762-5.

- ^ Madden, David; Bane, Charles; Flory, Sean M. (2006). A Primer of the Novel: For Readers and Writers. Scarecrow Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-4616-5597-8.

- ^ Coville, Jamie. «The History of Comic Books: Introduction and ‘The Platinum Age 1897–1938’«. TheComicBooks.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2003.

- ^ Gravett, Paul (2005). Graphic Novels: Stories To Change Your Life (1st ed.). Aurum Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-84513-068-8.

- ^ Matthew Rubery, ed. (2011). «Introduction». Audiobooks, Literature, and Sound Studies. Routledge. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-0-415-88352-8.

- ^ Cheung, Rachel (May 6, 2018). «China’s online publishing industry – where fortune favours the few, and sometimes the undeserving». South China Morning Post. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ «Chinese Web Novel: The New Trending Pastime Entertainment». Funwemake. 29 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ «Top Ten Languages Used in the Web». Internet World Stats. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ 승환, 이. «웹출판의 발전과 과제(The Development and Tasks of Web Publication)». scholar.dkyobobook.co.kr (78). doi:10.21732/skps.2017.78.97. Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- ^ 민정, 고(Ko MinJung). «한국 웹소설의 플랫폼 성장과 가능성(Platform Growth and Possibility of Korean Web Novels)». scholar.dkyobobook.co.kr. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

- ^ Watson, Amy (9 November 2020). «Number of International Standard Book Numbers (ISBNs) assigned to self-published books in the United States from 2010 to 2018». statista.

- ^ Pope, Bella Rose (9 September 2021). «Self-Publishing vs Traditional Publishing: How to Choose». Self-Publishing School.

- ^ Watson, Amy (10 September 2021). «U.S. book industry — statistics & facts». statista.

Further reading[edit]

Theories of the novel

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. About novel. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Ed. Michael Holquist. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin and London: University of Texas Press, 1981. [written during the 1930s]

- Burgess, Anthony. «novel: Definition, Elements, Examples, Types, & Facts». www.britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- Lukács, Georg (1971) [1916]. The Theory of the Novel. Translated by Anna Bostock. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Madden, David; Charles Bane; Sean M. Flory (2006) [1979]. A Primer of the Novel: For Readers and Writers (revised ed.). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5708-7. Updated edition of pioneering typology and history of over 50 genres; index of types and technique, and detailed chronology.

- McKeon, Michael, Theory of the Novel: A Historical Approach (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000).

Histories of the novel

- Armstrong, Nancy (1987). Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504179-8.

- Burgess, Anthony (1967). The Novel Now: A Student’s Guide to Contemporary Fiction. London: Faber.

- Davis, Lennard J. (1983). Factual Fictions: The Origins of the English Novel. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-05420-1.

- Doody, Margaret Anne (1996). The True Story of the Novel. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-2168-8.

- Gosse, Edmund William (1911). «Novel» . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 833–838.

- Heiserman, Arthur Ray. The Novel Before the Novel (Chicago, 1977) ISBN 0-226-32572-5

- McKeon, Michael (1987). The Origins of the English Novel, 1600–1740. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-3291-8.

- Mentz, Steve (2006). Romance for sale in early modern England: the rise of prose fiction. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-5469-9

- Moore, Steven (2013). The Novel: An Alternative History. Vol. 1, Beginnings to 1600: Continuum, 2010. Vol. 2, 1600–1800: Bloomsbury.

- Müller, Timo (2017). Handbook of the American Novel of the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries. Boston: de Gruyter.

- Price, Leah (2003). The Anthology and the Rise of the Novel: From Richardson to George Eliot. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53939-5. from Leah Price

- Relihan, Constance C. (ed.), Framing Elizabethan fictions: contemporary approaches to early modern narrative prose (Kent, Ohio/ London: Kent State University Press, 1996). ISBN 0-87338-551-9

- Roilos, Panagiotis, Amphoteroglossia: A Poetics of the Twelfth-Century Medieval Greek Novel (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2005).

- Rubens, Robert, «A hundred years of fiction: 1896 to 1996. (The English Novel in the Twentieth Century, part 12).» Contemporary Review, December 1996.

- Schmidt, Michael, The Novel: A Biography (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2014).

- Watt, Ian (1957). The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding. Berkeley: University of Los Angeles Press.

External links[edit]

Wikiquote has quotations related to Novel.

- The novel 1780-1832 at the British Library

- The novel 1832-1880 at the British Library

- The House of the Seven Gables with «Preface»

- «The 100 greatest novels of all time». The Telegraph. 2 March 2021. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

Adjective

She has suggested a novel approach to the problem.

Handheld computers are novel devices.

Recent Examples on the Web

Facilitating The Ability To Look Ahead Ultimately, heuristics are most novel because of their capacity to enable future projections.

—

For Refsnyder, who has made a career of spring roster spot battles as a non-roster invitee, being on a 40-man roster and having a secure big league job regardless of his spring performance is novel.

—

With a quality rating for each of the human decisions in hand, the researchers then developed a means to pinpoint exactly when a human decision during a game was novel, meaning it had not been recorded before in the history of the game.

—

The concept of cheese in dessert is not novel: Creamy mascarpone stars in classic tiramisu, and plenty of Italian cooks turn ricotta into doughnut-like fritters.

—

The program certainly was novel: Chopin’s E minor Piano Concerto in a Krzysztof Dombek/Kevin Kenner arrangement for just piano and strings, and Schubert’s B-flat major Piano Sonata in Heribert Breuer’s arrangement replacing the piano with wind trio (clarinet, bassoon and horn) and strings.

—

Arugula was so novel it is spelled arugola.

—

The good news is that none of these criticisms are particularly novel, so everyone who speaks for the franchise should be ready to answer these questions and more.

—

The fuel is novel for the aviation industry and could require a longer regulatory approval process, McMicking says.

—

Julie Anne Peters, a writer who pushed the boundaries of young-adult literature with novels that contained some of the genre’s first sensitive portrayals of gay love and transgender identity, died March 21 at her home in Wheat Ridge, Colo.

—

In the summer of 2021, Sittenfeld realized her notional screenplay should actually be a novel.

—

This issue is so much bigger than my fictional novel and personal desires.

—

But while Martel’s novel has a deep and sometimes tendentious concern with religion and philosophy, Chakrabarti’s adaptation engages with these questions only glancingly.

—

Soon, Microsoft, NVidia, Google, Disney, Unity Technology, Roblox Corporation, Amazon, Animoca Brands, Epic Games, Decentraland, and even Binance made a beeline for a piece of this novel technology.

—

Link deftly balances humor with a real sense of longing, making the tale a beautifully realistic love story — or at least as realistic as a story with a talking snake (and a cameo from a mystery novel-loving rat) can be.

—

Alderman’s novel also began as a seemingly simplistic empowerment fantasy before working its way toward thornier and ultimately more rewarding territory.

—

And with a few notable exceptions, the most beloved detective games tend to be visual novels.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘novel.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

What Does Novel Mean?

You’ve likely come across the word novel, but what exactly does it mean?

According to Britannica.com, a novel can be defined as a fictitious prose narrative of considerable length (aka a hefty word count) with a certain complexity that deals imaginatively with human experience. This is usually through a connected sequence of events involving individuals in a specific setting.

A simpler definition of this noun states that a novel is a long written story about imaginary people and events.