Loyalty is a devotion and faithfulness to a nation, cause, philosophy, country, group, or person.[1] Philosophers disagree on what can be an object of loyalty, as some argue that loyalty is strictly interpersonal and only another human being can be the object of loyalty. The definition of loyalty in law and political science is the fidelity of an individual to a nation, either one’s nation of birth, or one’s declared home nation by oath (naturalization).

Historical concepts[edit]

Western world[edit]

Classical tragedy is often based on a conflict arising from dual loyalty.

Euthyphro, one of Plato’s early dialogues, is based on the ethical dilemma arising from

Euthyphro intending to lay manslaughter charges against his own father, who had caused the death of a slave through negligence.

In the Gospel of Matthew 6:24, Jesus states, «No one can serve two masters. Either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and mammon». This relates to the authority of a master over his servants (as per Ephesians 6:5), who, according to Biblical law, owe undivided loyalty to their master (as per Leviticus 25:44–46).[2]

On the other hand, the «Render unto Caesar» of the synoptic gospels acknowledges the possibility of distinct loyalties (secular and religious) without conflict, but if loyalty to man conflicts with loyalty to God, the latter takes precedence.[3]

The Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition defines loyalty as «allegiance to the sovereign or established government of one’s country» and also «personal devotion and reverence to the sovereign and royal family». It traces the word «loyalty» to the 15th century, noting that then it primarily referred to fidelity in service, in love, or to an oath that one has made. The meaning that the Britannica gives as primary, it attributes to a shift during the 16th century, noting that the origin of the word is in the Old French «loialte», that is in turn rooted in the Latin «lex», meaning «law». One who is loyal, in the feudal sense of fealty, is one who is lawful (as opposed to an outlaw), who has full legal rights as a consequence of faithful allegiance to a feudal lord. Hence the 1911 Britannica derived its (early 20th century) primary meaning of loyalty to a monarch.[4][5]

East Asia[edit]

(Zhong)[clarification needed] Often cited as one of the many virtues of Confucianism, meaning to do the best you can do for others.

«Loyalty» is the most important and frequently emphasized virtue in Bushido. In combination with six other virtues, which are Righteousness (義 gi?), Courage (勇 yū?), Benevolence, (仁 jin?), Respect (礼 rei?), Sincerity (誠 makoto?), and Honour (名誉 meiyo?), it formed the Bushido code: «It is somehow implanted in their chromosomal makeup to be loyal».[6]

Modern concepts[edit]

Josiah Royce presented a different definition of the concept in his 1908 book The Philosophy of Loyalty. According to Royce, loyalty is a virtue, indeed a primary virtue, «the heart of all the virtues, the central duty amongst all the duties». Royce presents loyalty, which he defines at length, as the basic moral principle from which all other principles can be derived.[7] The short definition that he gives of the idea is that loyalty is «the willing and practical and thoroughgoing devotion of a person to a cause».[8][7][9] Loyalty is thoroughgoing in that it is not merely a casual interest but a wholehearted commitment to a cause.[10]

Royce’s view of loyalty was challenged by Ladd in the article on «Loyalty» in the first edition of the Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1967).

Ralls (1968) observes that Ladd’s article is the Macmillan Encyclopaedia‘s only article on a virtue, and praises it for its «magnificent» declaration by Ladd that «a loyal Nazi is a contradiction in terms».[11]

Ladd asserts that, contrary to Royce, causes to which one is loyal are interpersonal, not impersonal or suprapersonal.[12] He states that Royce’s view has «the ethical defect of postulating duties over and above our individual duties to men and groups of men. The individual is submerged and lost in this superperson for its tends to dissolve our specific duties to others into ‘superhuman’ good». Ronald F. Duska, the Lamont Post Chair of Ethics and the Professions at The American College, extends Ladd’s objection, saying that it is a perversion of ethics and virtue for one’s self-will to be identified with anything, as Royce would have it. Even if one were identifying one’s self-will with God, to be worthy of such loyalty God would have to be the summum bonum, the perfect manifestation of good.

Ladd himself characterizes loyalty as interpersonal, i.e., a relationship between a lord and vassal, parent and child, or two good friends. Duska states that doing so leads to a problem that Ladd overlooks. Loyalty may certainly be between two persons, but it may also be from a person to a group of people. Examples of this, which are unequivocally considered to be instances of loyalty, are loyalty by a person to his or her family, to a team that he or she is a member or fan of, or to his or her country. The problem with this that Duska identifies is that it then becomes unclear whether there is a strict interpersonal relationship involved, and whether Ladd’s contention that loyalty is interpersonal—not suprapersonal—is an adequate description.[13]

Ladd considers loyalty from two perspectives: its proper object and its moral value.[14]

John Kleinig, professor of philosophy at City University of New York, observes that over the years the idea has been treated by writers from Aeschylus through John Galsworthy to Joseph Conrad, by psychologists, psychiatrists, sociologists, scholars of religion, political economists, scholars of business and marketing, and—most particularly—by political theorists, who deal with it in terms of loyalty oaths and patriotism. As a philosophical concept, loyalty was largely untreated by philosophers until the work of Josiah Royce, the «grand exception» in Kleinig’s words.[8] John Ladd, professor of philosophy at Brown University, writing in the Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy in 1967, observes that by that time the subject had received «scant attention in philosophical literature». This he attributed to «odious» associations that the subject had with nationalism, including Nazism, and with the metaphysics of idealism, which he characterized as «obsolete». However, he argued that such associations were faulty and that the notion of loyalty is «an essential ingredient in any civilized and humane system of morals».[14] Kleinig observes that from the 1980s onwards, the subject gained attention, with philosophers variously relating it to professional ethics, whistleblowing, friendship, and virtue theory.[8]

Additional aspects enumerated by Kleinig include the exclusionary nature of loyalty and its subjects.[8]

The proper object of loyalty[edit]

Ladd and others, including Milton R. Konvitz[year needed] and Marcia W. Baron (1984),[12] disagree amongst themselves as to the proper object of loyalty—what it is possible to be loyal to, in other words. Ladd, as stated, considers loyalty to be interpersonal, and that the object of loyalty is always a person. In the Encyclopaedia of the History of Ideas, Konvitz states that the objects of loyalty encompass principles, causes, ideas, ideals, religions, ideologies, nations, governments, parties, leaders, families, friends, regions, racial groups, and «anyone or anything to which one’s heart can become attached or devoted».[15] Baron agrees with Ladd, inasmuch as loyalty is «to certain people or to a group of people, not loyalty to an ideal or cause». She argues in her monograph, The Moral Status of Loyalty, that «[w]hen we speak of causes (or ideals) we are more apt to say that people are committed to them or devoted to them than that they are loyal to them». Kleinig agrees with Baron, noting that a person’s earliest and strongest loyalties are almost always to people, and that only later do people arrive at abstract notions like values, causes, and ideals. He disagrees, however, with the notion that loyalties are restricted solely to personal attachments, considering it «incorrect (as a matter of logic)».[16] Loyalty to people and abstract notions such as causes or ideals is considered an evolutionary tactic, as there is a greater chance of survival and procreation if animals belong to loyal packs.[17]

In his combined works, Immanuel Kant constructed the basis for an ethical law by the concept of duty.[18] Kant began his ethical theory by arguing that the only virtue that can be unqualifiedly good is a good will. No other virtue has this status because every other virtue can be used to achieve immoral ends (for example, the virtue of loyalty is not good if one is loyal to an evil person). The good will is unique in that it is always good and maintains its moral value even when it fails to achieve its moral intentions.[19] Kant regarded the good will as a single moral principle that freely chooses to use the other virtues for moral ends.[20]

Multiplicity, disloyalty, and whether loyalty is exclusionary[edit]

Stephen Nathanson, professor of philosophy at Northeastern University, states that loyalty can be either exclusionary or non-exclusionary; and can be single or multiple. Exclusionary loyalty excludes loyalties to other people or groups; whereas non-exclusionary loyalty does not. People may have single loyalties, to just one person, group, or thing, or multiple loyalties to multiple objects. Multiple loyalties can constitute a disloyalty to an object if one of those loyalties is exclusionary, excluding one of the others. However, Nathanson observes, this is a special case. In the general case, the existence of multiple loyalties does not cause a disloyalty. One can, for example, be loyal to one’s friends, or one’s family, and still, without contradiction, be loyal to one’s religion, or profession.

Other dimensions[edit]

In addition to number and exclusion as just outlined, Nathanson enumerates five other «dimensions» that loyalty can vary along: basis, strength, scope, legitimacy, and attitude.[21]

Loyalties differ in basis according to their foundations. They may be constructed upon the basis of unalterable facts that constitute a personal connection between the subject and the object of the loyalty, such as biological ties or place of birth (a notion of natural allegiance propounded by Socrates in his political theory). Alternatively, they may be constructed from personal choice and evaluation of criteria with a full degree of freedom. The degree of control that one has is not necessarily simple; Nathanson points out that whilst one has no choice as to one’s parents or relatives, one can choose to desert them.[21]

Loyalties differ in strength. They can range from supreme loyalties, that override all other considerations, to merely presumptive loyalties, that affect one’s presumptions, providing but one motivation for action that is weighed against other motivations. Nathanson observes that strength of loyalty is often interrelated with basis. «Blood is thicker than water», states an aphorism, explaining that loyalties that have biological ties as their bases are generally stronger.[21]

Loyalties differ in scope. They range from loyalties with limited scope, that require few actions of the subject, to loyalties with broad or even unlimited scopes, which require many actions, or indeed to do whatever may be necessary in support of the loyalty. Loyalty to one’s job, for example, may require no more action than simple punctuality and performance of the tasks that the job requires. Loyalty to a family member can, in contrast, have a very broad effect upon one’s actions, requiring considerable personal sacrifice. Extreme patriotic loyalty may impose an unlimited scope of duties. Scope encompasses an element of constraint. Where two or more loyalties conflict, their scopes determine what weight to give to the alternative courses of action required by each loyalty.[21]

Loyalties differ in legitimacy. This is of particular relevance to the conflicts among multiple loyalties. People with one loyalty can hold that another, conflicting, loyalty is either legitimate or illegitimate. In the extreme view, one that Nathanson ascribes to religious extremists and xenophobes for examples, all loyalties bar one’s own are considered illegitimate. The xenophobe does not regard the loyalties of foreigners to their countries as legitimate while the religious extremist does not acknowledge the legitimacy of other religions. At the other end of the spectrum, past the middle ground of considering some loyalties as legitimate and others not, according to cases, or plain and simple indifference to other people’s loyalties, is the positive regard of other people’s loyalties.[21]

Finally, loyalties differ in the attitude that the subjects of the loyalties have towards other people. (Note that this dimension of loyalty concerns the subjects of the loyalty, whereas legitimacy, above, concerns the loyalties themselves.) People may have one of a range of possible attitudes towards others who do not share their loyalties, with hate and disdain at one end, indifference in the middle, and concern and positive feeling at the other.[21]

In relation to other subjects[edit]

Patriotism[edit]

Nathanson observes that loyalty is often directly equated to patriotism. He states, that this is, however, not actually the case, arguing that whilst patriots exhibit loyalty, it is not conversely the case that all loyal persons are patriots. He provides the example of a mercenary soldier, who exhibits loyalty to the people or country that pays him. Nathanson points to the difference in motivations between a loyal mercenary and a patriot. A mercenary may well be motivated by a sense of professionalism or a belief in the sanctity of contracts. A patriot, in contrast, may be motivated by affection, concern, identification, and a willingness to sacrifice.[21]

Nathanson contends that patriotic loyalty is not always a virtue. A loyal person can, in general be relied upon, and hence people view loyalty as virtuous. Nathanson argues that loyalty can, however, be given to persons or causes that are unworthy. Moreover, loyalty can lead patriots to support policies that are immoral and inhumane. Thus, Nathanson argues, patriotic loyalty can sometimes rather be a vice than a virtue, when its consequences exceed the boundaries of what is otherwise morally desirable. Such loyalties, in Nathanson’s view, are erroneously unlimited in their scopes, and fail to acknowledge boundaries of morality.[21]

Employment[edit]

The faithless servant doctrine is a doctrine under the laws of a number of states in the United States, and most notably New York State law, pursuant to which an employee who acts unfaithfully towards his employer must forfeit all of the compensation he received during the period of his disloyalty.[22][23][24][25][26]

Whistleblowing[edit]

Several scholars, including Duska, discuss loyalty in the context of whistleblowing. Wim Vandekerckhove of the University of Greenwich points out that in the late 20th century saw the rise of a notion of a bidirectional loyalty—between employees and their employer. (Previous thinking had encompassed the idea that employees are loyal to an employer, but not that an employer need be loyal to employees.) The ethics of whistleblowing thus encompass a conflicting multiplicity of loyalties, where the traditional loyalty of the employee to the employer conflicts with the loyalty of the employee to his or her community, which the employer’s business practices may be adversely affecting. Vandekerckhove reports that different scholars resolve the conflict in different ways, some of which he, himself, does not find to be satisfactory. Duska resolves the conflict by asserting that there is really only one proper object of loyalty in such instances, the community, a position that Vandekerckhove counters by arguing that businesses are in need of employee loyalty.

John Corvino, associate professor of philosophy at Wayne State University takes a different tack, arguing that loyalty can sometimes be a vice, not a virtue, and that «loyalty is only a virtue to the extent that the object of loyalty is good» (similar to Nathanson). Vandekerckhove calls this argument «interesting» but «too vague» in its description of how tolerant an employee should be of an employer’s shortcomings. Vandekerckhove suggests that Duska and Corvino combine, however, to point in a direction that makes it possible to resolve the conflict of loyalties in the context of whistleblowing, by clarifying the objects of those loyalties.[5]

Marketing[edit]

Businesses seek to become the objects of loyalty in order to retain customers. Brand loyalty is a consumer’s preference for a particular brand and a commitment to repeatedly purchase that brand.[27] Loyalty programs offer rewards to repeat customers in exchange for being able to keep track of consumer preferences and buying habits.[28]

One similar concept is fan loyalty, an allegiance to and abiding interest in a sports team, fictional character, or fictional series. Devoted sports fans continue to remain fans even in the face of a string of losing seasons.[29]

In the Bible[edit]

Attempting to serve two masters leads to «double-mindedness» (James 4:8), undermining loyalty to a cause. The Bible also speaks of loyal ones, which would be those who follow the Bible with absolute loyalty, as in «Precious in the eyes of God is the death of his loyal ones» (Psalms 116:15). Most Jewish and Christian authors view the binding of Isaac (Genesis 22), in which Abraham was called by God to offer his son Isaac as a burnt offering, as a test of Abraham’s loyalty.[30] Joseph’s faithfulness to his master Potiphar and his rejection of Potiphar’s wife’s advances (Genesis 39) have also been called an example of the virtue of loyalty.[31]

Misplaced[edit]

Misplaced or mistaken loyalty refers to loyalty placed in other persons or organisations where that loyalty is not acknowledged or respected, is betrayed, or taken advantage of. It can also mean loyalty to a malignant or misguided cause.

Social psychology provides a partial explanation for the phenomenon in the way «the norm of social commitment directs us to honor our agreements…People usually stick to the deal even though it has changed for the worse».[32] Humanists point out that «man inherits the capacity for loyalty, but not the use to which he shall put it…may unselfishly devote himself to what is petty or vile, as he may to what is generous and noble».[33]

In animals[edit]

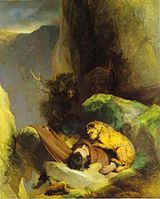

Animals as pets may display a sense of loyalty to humans. Famous cases include Greyfriars Bobby, a Skye terrier who attended his master’s grave for fourteen years; Hachiko, a dog who returned to the place he used to meet his master every day for nine years after his death;[34] and Foxie, the spaniel belonging to Charles Gough, who stayed by her dead master’s side for three months on Helvellyn in the Lake District in 1805 (although it is possible that Foxie had eaten Gough’s body).[35]

In the Mahabharata, the righteous King Yudhishthira appears at the gates of Heaven at the end of his life with a stray dog he had picked up along the way as a companion, having previously lost his brothers and his wife to death. The god Indra is prepared to admit him to Heaven, but refuses to admit the dog, so Yudhishthira refuses to abandon the dog, and prepares to turn away from the gates of Heaven. Then the dog is revealed[by whom?] to be the manifestation of Dharma, the god of righteousness and justice, and who turned out to be his deified self. Yudhishthira enters heaven in the company of his dog, the god of righteousness.[36][37] Yudhishthira is known by the epithet Dharmaputra, the lord of righteous duty.

See also[edit]

Wikiquote has quotations related to Loyalty.

- Filial piety

- Pietas

References[edit]

- ^ «Loyalty definition and meaning — Collins English Dictionary». Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ White, Edward J. (2000). The Law in the Scriptures: With Explanations of the Law Terms and Legal References in Both the Old and the New Testaments. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. p. 295. ISBN 978-1-58477-076-3.

- ^ Sharma, Urmila; Sharma, S.K. (1998). «Christian political thought». Western Political Thought. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. pp. 220 et seq. ISBN 978-81-7156-683-9.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Loyalty». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 80.

- ^ a b Vandekerckhove, Wim (2006). Whistleblowing and organizational social responsibility: a global assessment. Corporate social responsibility series. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 127 et seq. ISBN 978-0-7546-4750-8.

- ^ Hurst, G. Cameron (October 1990). «Death, Honor, and Loyality [sic]: The Bushidō Ideal». Philosophy East and West. 40 (4): 511–527. doi:10.2307/1399355. ISSN 0031-8221. JSTOR 1399355.

- ^ a b Thilly, Frank (1908). «Review of The Philosophy of Loyalty«. Philosophical Review. 17. doi:10.2307/2177218. JSTOR 2177218.

reprinted as Thilly, Frank (2000). «Review of The Philosophy of Loyalty«. In Randall E. Auxier (ed.). Critical responses to Josiah Royce, 1885–1916. History of American Thought. Vol. 1. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-85506-833-9. - ^ a b c d Kleinig, John (21 August 2007). «Loyalty». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Martin, Mike W. (1994). Virtuous giving: philanthropy, voluntary service, and caring. Indiana University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-253-33677-4.

- ^ Mullin, Richard P. (2005). «Josiah Royce’s Philosophy of Loyalty as the Basis for Democratic Ethics». In Leszek Koczanowicz; Beth J. Singer (eds.). Democracy and the post-totalitarian experience. Value inquiry book series: Studies in pragmatism and values. Vol. 167. Rodopi. pp. 183–84. ISBN 978-90-420-1635-4.

- ^ Ralls, Anthony (January 1968). «Review of The Encyclopedia of Philosophy«. The Philosophical Quarterly. 18 (70): 77–79. doi:10.2307/2218041. JSTOR 2218042.

- ^ a b Baron, Marcia (1984). The moral status of loyalty. CSEP module series in applied ethics. Kendall/Hunt Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-8403-3423-7.

- ^ Duska, Ronald F. (2007). «Whistleblowing and Employee Loyalty». Contemporary reflections on business ethics. Vol. 23. Springer. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-4020-4983-5.

- ^ a b Ladd, John (1967). «Loyalty». In Paul Edwards (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Vol. 5. Macmillan. p. 97.

- ^ Konvitz 1973, p. 108.

- ^ Kleinig, John (1996). The ethics of policing. Cambridge studies in philosophy and public policy. Cambridge University Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-521-48433-6.

- ^ «The Power of Tribes in Evolution». Breed Bites. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 23 January 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Blackburn, Simon (2008). «Morality». Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy (Second edition revised ed.). p. 240.

- ^ Benn, Piers (1998). Ethics. UCL Press. pp. 101–2. ISBN 1-85728-453-4.

- ^ Guyer, Paul (2011). «Chapter 8: Kantian Perfectionism». In Jost, Lawrence; Wuerth, Julian (eds.). Perfecting Virtue: New Essays on Kantian Ethics and Virtue Ethics. Cambridge University Press. p. 194. ISBN 9781139494359.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nathanson, Stephen (1993). Patriotism, morality, and peace. New Feminist Perspective Series. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 106–09. ISBN 978-0-8476-7800-6.

- ^ Glynn, Timothy P.; Arnow-Richman, Rachel S.; Sullivan, Charles A. (2019). Employment Law: Private Ordering and Its Limitations. Wolters Kluwer Law & Business. ISBN 9781543801064 – via Google Books.

- ^ Annual Institute on Employment Law. Vol. 2. Practising Law Institute. 2004 – via Google Books.

- ^ New York Jurisprudence 2d. Vol. 52. West Group. 2009 – via Google Books.

- ^ Labor Cases. Vol. 158. Commerce Clearing House. 2009 – via Google Books.

- ^ Ellie Kaufman (19 May 2018). «Met Opera sues former conductor for $5.8 million over sexual misconduct allegations». CNN.

- ^ Dick Alan S.; Basu Kunal (1994). «Customer Loyalty: Toward an Integrated Conceptual Framework». Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 22 (2): 99–113. doi:10.1177/0092070394222001. S2CID 55369763.

- ^ Sharp Byron; Sharp Anne (1997). «Loyalty Programs and Their Impact on Repeat-Purchase Loyalty Patterns» (PDF). International Journal of Research in Marketing. 14 (5): 473–86. doi:10.1016/s0167-8116(97)00022-0.

- ^ Conrad, Mark (2011). The Business of Sports: A Primer for Journalists (2 ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415876520.

- ^ Berman, Louis A., The Akedah: The Binding of Isaac. (Rowman & Littlefield, 1997; ISBN 1-56821-899-0.)

- ^ William J. Bennett, The Book of Virtues: A Treasury of Great Moral Stories (Simon & Schuster, 1995; ISBN 0-684-83577-0), p. 665.

- ^ Eliot R. Smith and Diane M. Mackie, Social Psychology (2007) p. 390

- ^ Arthur James Balfour, Theism and Humanism (2000) p. 65

- ^ Katharine Rogers (2010), First Friend, ISBN 978-1450208734

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (15 March 2003). «The Romantics and the Myth of Charles Gough». The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ^

Mahabharata, book 17, ch. 3 - ^ Bennett, supra, pp. 684–85

Further reading[edit]

- Alford, C. Fred (2002). «Implications of Whistleblower Ethics for Ethical Theory». Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8780-4.

- Axinn, Sydney (1997). «Loyalty». In Patricia H. Werhane; R. Edward Freeman (eds.). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Business Ethics. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 388–390.

- Connor, James (25 July 2007). The Sociology of Loyalty (1st ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-71367-0.

- Corvino, John (November 2002). «Loyalty in Business?». Journal of Business Ethics. 41 (1–2): 179–185. doi:10.1023/A:1021370727220. ISSN 0167-4544. S2CID 154177012.

- Ewin, R. Edward (October 1992). «Loyalty and Virtues». The Philosophical Quarterly. 42 (169): 403–419. doi:10.2307/2220283. JSTOR 2220283.

- Kim Dae-jung (June 1999). «Loyalty, Filial Piety in Changing Times».

- Konvitz, Milton R. (1973). «Loyalty». In Philip P. Wiener (ed.). Encyclopedia of the History of Ideas. Vol. III. New York: Scribner’s. p. 108.

- Mullin, Richard P. (10 May 2007). «Josiah Royce’s Philosophy of Loyalty as the Basis for Ethics». The Soul of Classical American Philosophy: The Ethical and Spiritual Insights of William James, Josiah Royce, and Charles Sanders Peirce. SUNY Press. p. 2007. ISBN 978-0-7914-7109-8.

- Nitobe, Inazō (1975). «The Duty of Loyalty». In Charles Lucas (ed.). Bushido: The Warrior’s Code. History and Philosophy Series. Vol. 303. Black Belt Communications. ISBN 978-0-89750-031-9.

- Royce, Josiah (1908). The Philosophy of Loyalty. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- William Ritchie Sorley (1908). «Review of The Philosophy of Loyalty«. The Hibbert Journal. 7.

Reprinted as William Ritchie Sorley (2000). «Review of The Philosophy of Loyalty«. In Randall E. Auxier (ed.). Critical Responses to Josiah Royce, 1885–1916. History of American Thought. Vol. 1. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-85506-833-9. - White, Howard B. (1956). «Royce’s Philosophy of Loyalty». The Journal of Philosophy. 53 (3): 99–103. doi:10.2307/2022080. JSTOR 2022080.

: the quality or state or an instance of being loyal

the loyalty of the team’s fans

Synonyms

Choose the Right Synonym for loyalty

allegiance suggests an adherence like that of citizens to their country.

fealty implies a fidelity acknowledged by the individual and as compelling as a sworn vow.

loyalty implies a faithfulness that is steadfast in the face of any temptation to renounce, desert, or betray.

valued the loyalty of his friends

devotion stresses zeal and service amounting to self-dedication.

a painter’s devotion to her art

piety stresses fidelity to obligations regarded as natural and fundamental.

Example Sentences

the loyalty of the team’s fans

there was no denying that dog’s loyalty to his master

Recent Examples on the Web

Fittingly, the man without a true loyalty passed on a plane, leaving this world while in the air — and leaving his children up in the air, too, about who at long last would take over his empire.

—

Another similarity to fascism related to this preference for loyalty over training is the targeted sidelining of experts and outright rejection of contradictory viewpoints.

—

Speaking to reporters ahead of Trump’s remarks Tuesday night, Lake made clear her loyalty was unflinching.

—

Fan support can sometimes demonstrate loyalty to a show that Nielsen ratings don’t.

—

Among the loyalty-inspiring aspects of Tim Hortons is its annual Roll Up To Win contest.

—

Bolden-Hardge told the court that the Franchise Tax Board and other state government departments had altered their loyalty oaths without any adverse consequences.

—

By the end of the episode, Logan likely regains Roman’s loyalty, but also loses faith from Kerry — some faith, anyway.

—

From the late 1980s through the aughts, no company defined prep or inspired the kind of customer loyalty that J. Crew did.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘loyalty.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Etymology

alteration of Middle English leawte, lewte, from Anglo-French lealté, leauté, from leal, leial loyal

First Known Use

15th century, in the meaning defined above

Time Traveler

The first known use of loyalty was

in the 15th century

Dictionary Entries Near loyalty

Cite this Entry

“Loyalty.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/loyalty. Accessed 14 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on loyalty

Last Updated:

12 Apr 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

лояльность, верность, преданность

существительное ↓

- верность, преданность

- лояльность; благонадёжность

loyalty certificate — свидетельство о благонадежности

loyalty oath — амер. «присяга в благонадёжности»; подписка о непринадлежности к подрывным организациям

loyalty purge — амер. чистка государственных учреждений от заподозренных в нелояльном отношении к американскому образу жизни

loyalty test — амер. «проверка лояльности» (государственных служащих)

- pl. родственные чувства; привязанность

tribal loyalties — чувства, связывающие членов одного племени, племенная связь

Мои примеры

Словосочетания

the loyalty of the team’s fans — преданность поклонников команды

a politician with unswerving loyalty to the President — политик, непоколебимо пренданный президенту

under the cloak of loyalty — под маской лояльности

to make a declaration of loyalty to the king — дать клятву верности королю

display of loyalty — демонстрация лояльности

loyalty to one’s friends — верность своим друзьям

to demonstrate / show loyalty — выказывать преданность

to swear loyalty — клясться в верности

to command loyalty — быть лояльным

oath of loyalty / allegiance — присяга на верность

loyalty rebate — скидка за приверженность

loyalty status — степень приверженности

Примеры с переводом

Loyalty was her most admirable quality.

Верность была её самым восхитительным качеством.

They felt no loyalty to a losing team.

Они не чувствовали преданности по отношению к проигрывающей команде.

His loyalty to the Sovereign had something antique and touching in it.

В его преданности монарху было что-то старинное и трогательное.

He was baronetized for his loyalty to the country.

За свою преданность стране он получил титул баронета.

You can build customer loyalty, receive recognition and make a memorable impression with a simple three or four line handwritten note.

Вы можете завоевать доверие клиента, получить признание и произвести запоминающееся впечатление, если напишете послание в 3-4 строчки от руки.

He had an unconditional loyalty to his family.

Он был безусловно предан своей семье.

She has a strong sense of loyalty.

Она обладает сильным чувством лояльности.

ещё 9 примеров свернуть

Примеры, ожидающие перевода

They profess loyalty to the king.

He pledged his loyalty to the king and queen.

…“fealty” is a bookish synonym for “loyalty”…

Для того чтобы добавить вариант перевода, кликните по иконке ☰, напротив примера.

Возможные однокоренные слова

disloyalty — нелояльность, неверность, предательство, вероломство

loyalties — верность, преданность, родственные чувства, привязанность, приверженность

Формы слова

noun

ед. ч.(singular): loyalty

мн. ч.(plural): loyalties

Loyalty, in general use, is a devotion and faithfulness to a nation, cause, philosophy, country, group, or person. Philosophers disagree on what can be an object of loyalty, as some argue that loyalty is strictly interpersonal and only another human being can be the object of loyalty. The definition of loyalty in law and political science is the fidelity of an individual to a nation, either one’s nation of birth, or one’s declared home nation by oath.

Historical concepts

Western world

Further information: Semper fidelis, In Treue fest, Fidelity, and Tryggvi

Classical tragedy is often based on a conflict arising from dual loyalty. Euthyphro, one of Plato’s early dialogues, is based on the ethical dilemma arising from Euthyphro intending to lay manslaughter charges against his own father, who had caused the death of a slave through negligence.

In the Gospel of Matthew 6:24, Jesus states, “No one can serve two masters. Either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and mammon”. This relates to the authority of a master over his servants (as per Ephesians 6:5), who, according to Biblical law, owe undivided loyalty to their master (as per Leviticus 25:44–46). On the other hand, the “Render unto Caesar” of the synoptic gospels acknowledges the possibility of distinct loyalties (secular and religious) without conflict, but if loyalty to man conflicts with loyalty to God, the latter takes precedence.

The Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition defines loyalty as “allegiance to the sovereign or established government of one’s country” and also “personal devotion and reverence to the sovereign and royal family”. It traces the word “loyalty” to the 15th century, noting that then it primarily referred to fidelity in service, in love, or to an oath that one has made. The meaning that the Britannica gives as primary, it attributes to a shift during the 16th century, noting that the origin of the word is in the Old French “loialte”, that is in turn rooted in the Latin “lex”, meaning “law”. One who is loyal, in the feudal sense of fealty, is one who is lawful (as opposed to an outlaw), who has full legal rights as a consequence of faithful allegiance to a feudal lord. Hence the 1911 Britannica derived its (early 20th century) primary meaning of loyalty to a monarch.

East Asia

(Zhong) Often cited as one of the many virtues of Confucianism, meaning to do the best you can do for others.

“Loyalty” is the most important and frequently emphasized virtue in Bushido. In combination with six other virtues, which are Righteousness (義 gi?), Courage (勇 yū?), Benevolence, (仁 jin?), Respect (礼 rei?), Sincerity (誠 makoto?), and Honour (名誉 meiyo?), it formed the Bushido code: “It is somehow implanted in their chromosomal makeup to be loyal”.

Faith

Modern concepts

Josiah Royce presented a different definition of the concept in his 1908 book The Philosophy of Loyalty. According to Royce, loyalty is a virtue, indeed a primary virtue, “the heart of all the virtues, the central duty amongst all the duties”. Royce presents loyalty, which he defines at length, as the basic moral principle from which all other principles can be derived. The short definition that he gives of the idea is that loyalty is “the willing and practical and thoroughgoing devotion of a person to a cause”. Loyalty is thoroughgoing in that it is not merely a casual interest but a wholehearted commitment to a cause.

Royce’s view of loyalty was challenged by Ladd in the article on “Loyalty” in the first edition of the Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1967).

Ralls (1968) observes that Ladd’s article is the Macmillan Encyclopaedia‘s only article on a virtue, and praises it for its “magnificent” declaration by Ladd that “a loyal Nazi is a contradiction in terms”. Ladd asserts that, contrary to Royce, causes to which one is loyal are interpersonal, not impersonal or suprapersonal. He states that Royce’s view has “the ethical defect of postulating duties over and above our individual duties to men and groups of men. The individual is submerged and lost in this superperson for its tends to dissolve our specific duties to others into ‘superhuman’ good”. Ronald F. Duska, the Lamont Post Chair of Ethics and the Professions at The American College, extends Ladd’s objection, saying that it is a perversion of ethics and virtue for one’s self-will to be identified with anything, as Royce would have it. Even if one were identifying one’s self-will with God, to be worthy of such loyalty God would have to be the summum bonum, the perfect manifestation of good.

Ladd himself characterizes loyalty as interpersonal, i.e., a relationship between a lord and vassal, parent and child, or two good friends. Duska states that doing so leads to a problem that Ladd overlooks. Loyalty may certainly be between two persons, but it may also be from a person to a group of people. Examples of this, which are unequivocally considered to be instances of loyalty, are loyalty by a person to his or her family, to a team that he or she is a member or fan of, or to his or her country. The problem with this that Duska identifies is that it then becomes unclear whether there is a strict interpersonal relationship involved, and whether Ladd’s contention that loyalty is interpersonal—not suprapersonal—is an adequate description.

Ladd considers loyalty from two perspectives: its proper object and its moral value.

John Kleinig, professor of philosophy at City University of New York, observes that over the years the idea has been treated by writers from Aeschylus through John Galsworthy to Joseph Conrad, by psychologists, psychiatrists, sociologists, scholars of religion, political economists, scholars of business and marketing, and—most particularly—by political theorists, who deal with it in terms of loyalty oaths and patriotism. As a philosophical concept, loyalty was largely untreated by philosophers until the work of Josiah Royce, the “grand exception” in Kleinig’s words. John Ladd, professor of philosophy at Brown University, writing in the Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy in 1967, observes that by that time the subject had received “scant attention in philosophical literature”. This he attributed to “odious” associations that the subject had with nationalism, including Nazism, and with the metaphysics of idealism, which he characterized as “obsolete”. However, he argued that such associations were faulty and that the notion of loyalty is “an essential ingredient in any civilized and humane system of morals”. Kleinig observes that from the 1980s onwards, the subject gained attention, with philosophers variously relating it to professional ethics, whistleblowing, friendship, and virtue theory.

Additional aspects enumerated by Kleinig include the exclusionary nature of loyalty and its subjects.

The proper object of loyalty

Ladd and others, including Milton R. Konvitz and Marcia W. Baron (1984), disagree amongst themselves as to the proper object of loyalty—what it is possible to be loyal to, in other words. Ladd, as stated, considers loyalty to be interpersonal, and that the object of loyalty is always a person. In the Encyclopaedia of the History of Ideas, Konvitz states that the objects of loyalty encompass principles, causes, ideas, ideals, religions, ideologies, nations, governments, parties, leaders, families, friends, regions, racial groups, and “anyone or anything to which one’s heart can become attached or devoted”. Baron agrees with Ladd, inasmuch as loyalty is “to certain people or to a group of people, not loyalty to an ideal or cause”. She argues in her monograph, The Moral Status of Loyalty, that “[w]hen we speak of causes (or ideals) we are more apt to say that people are committed to them or devoted to them than that they are loyal to them”. Kleinig agrees with Baron, noting that a person’s earliest and strongest loyalties are almost always to people, and that only later do people arrive at abstract notions like values, causes, and ideals. He disagrees, however, with the notion that loyalties are restricted solely to personal attachments, considering it “incorrect (as a matter of logic)”. Loyalty to people and abstract notions such as causes or ideals is considered an evolutionary tactic, as there is a greater chance of survival and procreation if animals belong to loyal packs.

Multiplicity, disloyalty, and whether loyalty is exclusionary

Stephen Nathanson, professor of philosophy at Northeastern University, states that loyalty can be either exclusionary or non-exclusionary; and can be single or multiple. Exclusionary loyalty excludes loyalties to other people or groups; whereas non-exclusionary loyalty does not. People may have single loyalties, to just one person, group, or thing, or multiple loyalties to multiple objects. Multiple loyalties can constitute a disloyalty to an object if one of those loyalties is exclusionary, excluding one of the others. However, Nathanson observes, this is a special case. In the general case, the existence of multiple loyalties does not cause a disloyalty. One can, for example, be loyal to one’s friends, or one’s family, and still, without contradiction, be loyal to one’s religion, or profession.

Other dimensions

In addition to number and exclusion as just outlined, Nathanson enumerates five other “dimensions” that loyalty can vary along: basis, strength, scope, legitimacy, and attitude.

Loyalties differ in basis according to their foundations. They may be constructed upon the basis of unalterable facts that constitute a personal connection between the subject and the object of the loyalty, such as biological ties or place of birth (a notion of natural allegiance propounded by Socrates in his political theory). Alternatively, they may be constructed from personal choice and evaluation of criteria with a full degree of freedom. The degree of control that one has is not necessarily simple; Nathanson points out that whilst one has no choice as to one’s parents or relatives, one can choose to desert them.

Loyalties differ in strength. They can range from supreme loyalties, that override all other considerations, to merely presumptive loyalties, that affect one’s presumptions, providing but one motivation for action that is weighed against other motivations. Nathanson observes that strength of loyalty is often interrelated with basis. “Blood is thicker than water”, states an aphorism, explaining that loyalties that have biological ties as their bases are generally stronger.

Loyalties differ in scope. They range from loyalties with limited scope, that require few actions of the subject, to loyalties with broad or even unlimited scopes, which require many actions, or indeed to do whatever may be necessary in support of the loyalty. Loyalty to one’s job, for example, may require no more action than simple punctuality and performance of the tasks that the job requires. Loyalty to a family member can, in contrast, have a very broad effect upon one’s actions, requiring considerable personal sacrifice. Extreme patriotic loyalty may impose an unlimited scope of duties. Scope encompasses an element of constraint. Where two or more loyalties conflict, their scopes determine what weight to give to the alternative courses of action required by each loyalty.

Loyalties differ in legitimacy. This is of particular relevance to the conflicts among multiple loyalties. People with one loyalty can hold that another, conflicting, loyalty is either legitimate or illegitimate. In the extreme view, one that Nathanson ascribes to religious extremists and xenophobes for examples, all loyalties bar one’s own are considered illegitimate. The xenophobe does not regard the loyalties of foreigners to their countries as legitimate while the religious extremist does not acknowledge the legitimacy of other religions. At the other end of the spectrum, past the middle ground of considering some loyalties as legitimate and others not, according to cases, or plain and simple indifference to other people’s loyalties, is the positive regard of other people’s loyalties.

Finally, loyalties differ in the attitude that the subjects of the loyalties have towards other people. (Note that this dimension of loyalty concerns the subjects of the loyalty, whereas legitimacy, above, concerns the loyalties themselves.) People may have one of a range of possible attitudes towards others who do not share their loyalties, with hate and disdain at one end, indifference in the middle, and concern and positive feeling at the other.

In relation to other subjects

Patriotism

Main article: Patriotism

Nathanson observes that loyalty is often directly equated to patriotism. He states, that this is, however, not actually the case, arguing that whilst patriots exhibit loyalty, it is not conversely the case that all loyal persons are patriots. He provides the example of a mercenary soldier, who exhibits loyalty to the people or country that pays him. Nathanson points to the difference in motivations between a loyal mercenary and a patriot. A mercenary may well be motivated by a sense of professionalism or a belief in the sanctity of contracts. A patriot, in contrast, may be motivated by affection, concern, identification, and a willingness to sacrifice.

Nathanson contends that patriotic loyalty is not always a virtue. A loyal person can, in general be relied upon, and hence people view loyalty as virtuous. Nathanson argues that loyalty can, however, be given to persons or causes that are unworthy. Moreover, loyalty can lead patriots to support policies that are immoral and inhumane. Thus, Nathanson argues, patriotic loyalty can sometimes rather be a vice than a virtue, when its consequences exceed the boundaries of what is otherwise morally desirable. Such loyalties, in Nathanson’s view, are erroneously unlimited in their scopes, and fail to acknowledge boundaries of morality.

Employment

The faithless servant doctrine is a doctrine under the laws of a number of states in the United States, and most notably New York State law, pursuant to which an employee who acts unfaithfully towards his employer must forfeit all of the compensation he received during the period of his disloyalty.

Whistleblowing

Main article: Whistleblowing

Several scholars, including Duska, discuss loyalty in the context of whistleblowing. Wim Vandekerckhove of the University of Greenwich points out that in the late 20th century saw the rise of a notion of a bidirectional loyalty—between employees and their employer. (Previous thinking had encompassed the idea that employees are loyal to an employer, but not that an employer need be loyal to employees.) The ethics of whistleblowing thus encompass a conflicting multiplicity of loyalties, where the traditional loyalty of the employee to the employer conflicts with the loyalty of the employee to his or her community, which the employer’s business practices may be adversely affecting. Vandekerckhove reports that different scholars resolve the conflict in different ways, some of which he, himself, does not find to be satisfactory. Duska resolves the conflict by asserting that there is really only one proper object of loyalty in such instances, the community, a position that Vandekerckhove counters by arguing that businesses are in need of employee loyalty.

John Corvino, associate professor of philosophy at Wayne State University takes a different tack, arguing that loyalty can sometimes be a vice, not a virtue, and that “loyalty is only a virtue to the extent that the object of loyalty is good” (similar to Nathanson). Vandekerckhove calls this argument “interesting” but “too vague” in its description of how tolerant an employee should be of an employer’s shortcomings. Vandekerckhove suggests that Duska and Corvino combine, however, to point in a direction that makes it possible to resolve the conflict of loyalties in the context of whistleblowing, by clarifying the objects of those loyalties.

Marketing

Main article: Loyalty business model

Businesses seek to become the objects of loyalty in order to retain customers. Brand loyalty is a consumer’s preference for a particular brand and a commitment to repeatedly purchase that brand. Loyalty programs offer rewards to repeat customers in exchange for being able to keep track of consumer preferences and buying habits.

One similar concept is fan loyalty, an allegiance to and abiding interest in a sports team, fictional character, or fictional series. Devoted sports fans continue to remain fans even in the face of a string of losing seasons.

In the Bible

Attempting to serve two masters leads to “double-mindedness” (James 4:8), undermining loyalty to a cause. The Bible also speaks of loyal ones, which would be those who follow the Bible with absolute loyalty, as in “Precious in the eyes of God is the death of his loyal ones” (Psalms 116:15). Most Jewish and Christian authors view the binding of Isaac (Genesis 22), in which Abraham was called by God to offer his son Isaac as a burnt offering, as a test of Abraham’s loyalty. Joseph’s faithfulness to his master Potiphar and his rejection of Potiphar’s wife’s advances (Genesis 39) have also been called an example of the virtue of loyalty.

Misplaced

Main article: Misplaced loyalty

Misplaced or mistaken loyalty refers to loyalty placed in other persons or organisations where that loyalty is not acknowledged or respected, is betrayed, or taken advantage of. It can also mean loyalty to a malignant or misguided cause.

Social psychology provides a partial explanation for the phenomenon in the way “the norm of social commitment directs us to honor our agreements…People usually stick to the deal even though it has changed for the worse”. Humanists point out that “man inherits the capacity for loyalty, but not the use to which he shall put it…may unselfishly devote himself to what is petty or vile, as he may to what is generous and noble”.

Loyalty Dog

In animals

Animals as pets may display a sense of loyalty to humans. Famous cases include Greyfriars Bobby, a Skye terrier who attended his master’s grave for fourteen years; Hachiko, a dog who returned to the place he used to meet his master every day for nine years after his death; and Foxie, the spaniel belonging to Charles Gough, who stayed by her dead master’s side for three months on Helvellyn in the Lake District in 1805 (although it is possible that Foxie had eaten Gough’s body).

In the Mahabharata, the righteous King Yudhishthira appears at the gates of Heaven at the end of his life with a stray dog he had picked up along the way as a companion, having previously lost his brothers and his wife to death. The god Indra is prepared to admit him to Heaven, but refuses to admit the dog, so Yudhishthira refuses to abandon the dog, and prepares to turn away from the gates of Heaven. Then the dog is revealed to be the manifestation of Dharma, the god of righteousness and justice, and who turned out to be his deified self. Yudhishthira enters heaven in the company of his dog, the god of righteousness. Yudhishthira is known by the epithet Dharmaputra, the lord of righteous duty.

Adapted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

-

1

loyalty

ве́рность, пре́данность; лоя́льность

Англо-русский словарь Мюллера > loyalty

-

2

loyalty

Персональный Сократ > loyalty

-

3

loyalty

Politics english-russian dictionary > loyalty

-

4

loyalty

сущ.

1)

общ.

приверженность; верность, преданность; привязанность; лояльность

Syn:

Ant:

See:

See:

3)

соц.

терпение, смирение, согласие

*

See:

* * *

Англо-русский экономический словарь > loyalty

-

5

loyalty

1. n верность, преданность

2. n лояльность; благонадёжность

loyalty oath — «присяга в благонадёжности»; подписка о непринадлежности к подрывным организациям

3. n родственные чувства; привязанность

tribal loyalties — чувства, связывающие членов одного племени, племенная связь

Синонимический ряд:

1. fidelity (noun) adherence; adhesion; allegiance; ardor; constancy; faithfulness; fealty; fidelity; homage; patriotism; piety; steadfastness

2. love (noun) affection; attachment; bond; devotion; fondness; love; tie

Антонимический ряд:

English-Russian base dictionary > loyalty

-

6

loyalty

[ˈlɔɪəltɪ]

brand loyalty приверженность торговой марке consumer loyalty приверженность потребителя loyalty верность, преданность; лояльность loyalty верность loyalty лояльность, верность loyalty лояльность loyalty преданность loyalty соблюдение законов

English-Russian short dictionary > loyalty

-

7

loyalty

ˈlɔɪəltɪ сущ. верность, преданность;

лояльность (to) to command loyalty ≈ быть лояльным to demonstrate, show loyalty ≈ выказывать преданность to swear loyalty ≈ клясться в верности deep-rooted, strong, unquestioned, unshakable loyalty ≈ непоколебимая, не вызывающая сомнений верность party loyalty ≈ верность партии unswerving loyalty to one’s friends ≈ непреклонная верность своим друзьям Syn: allegiance

верность, преданность лояльность;

благонадежность — * certificate свидетельство благонадежности — * oath (американизм) «присяга в благонадежности»;

подписка о непринадлежности к подрывным организациям — * purge( американизм) чистка государственных учреждений от заподозренных в нелояльном отношении к американскому образу жизни — * test (американизм) «проверка лояльности» (государственных служащих) родственные чувства;

привязанность — tribal loyalties чувства, связывающие членов одного племени, племенная связь

brand ~ приверженность торговой марке

consumer ~ приверженность потребителя

loyalty верность, преданность;

лояльность ~ верность ~ лояльность, верность ~ лояльность ~ преданность ~ соблюдение законовБольшой англо-русский и русско-английский словарь > loyalty

-

8

loyalty

n

верность, преданность, лояльность

English-russian dctionary of diplomacy > loyalty

-

9

loyalty

[‘lɔɪəltɪ]

сущ.

1) верность, преданность

deep-rooted / strong / unquestioned / unshakable loyalty — непоколебимая, не вызывающая сомнений верность

to demonstrate / show loyalty — выказывать преданность

Syn:

Англо-русский современный словарь > loyalty

-

10

loyalty

[ʹlɔıəltı]

1. верность, преданность

2. лояльность; благонадёжность

loyalty oath — «присяга в благонадёжности»; подписка о непринадлежности к подрывным организациям

loyalty purge — чистка государственных учреждений от заподозренных в нелояльном отношении к американскому образу жизни

3.

родственные чувства; привязанность

tribal loyalties — чувства, связывающие членов одного племени, племенная связь

НБАРС > loyalty

-

11

loyalty

Англо-русский синонимический словарь > loyalty

-

12

loyalty

English-Russian big medical dictionary > loyalty

-

13

loyalty

Patent terms dictionary > loyalty

-

14

loyalty

English-russian dctionary of contemporary Economics > loyalty

-

15

loyalty

лояльность; приверженность; верность

♦ brand loyalty лояльность по отношению к определенной марке товара

Англо-русский словарь по рекламе > loyalty

-

16

loyalty

лояльность; уважение к властям и верность действующим законам.

* * *

сущ.

лояльность; уважение к властям и верность действующим законам.

Англо-русский словарь по социологии > loyalty

-

17

loyalty

Англо-русский словарь по экономике и финансам > loyalty

-

18

loyalty

ве́рность ж, пре́данность ж, лоя́льность ж

The Americanisms. English-Russian dictionary. > loyalty

-

19

loyalty

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > loyalty

-

20

loyalty

[`lɔɪ(ə)ltɪ]

верность, преданность; лояльность

Англо-русский большой универсальный переводческий словарь > loyalty

Страницы

- Следующая →

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

См. также в других словарях:

-

loyalty — loy‧al‧ty [ˈlɔɪəlti] noun [uncountable] MARKETING the fact of being loyal to a particular product: loyalty to • He has noticed a falloff in loyalty to particular brands of car. ˈbrand ˌloyalty MARKETING the degree to which people regularly buy a… … Financial and business terms

-

Loyalty — Loyalty … Википедия

-

Loyalty — Loy al*ty, n. [Cf. F. loyaut[ e]. See {Loyal}, and cf. {Legality}.] The state or quality of being loyal; fidelity to a superior, or to duty, love, etc. [1913 Webster] He had such loyalty to the king as the law required. Clarendon. [1913 Webster]… … The Collaborative International Dictionary of English

-

loyalty — c.1400, from O.Fr. loialté, leauté loyalty, fidelity; legitimacy; honesty; good quality (Mod.Fr. loyauté), from loial (see LOYAL (Cf. loyal)). Earlier leaute (mid 13c.), from the older French form. Loyalty oath first attested 1852 … Etymology dictionary

-

Loyalty — (spr. Leuältl), Inselgruppe des Westlichen Polynesiens, zwischen Neu Caledonien u. den Neuen Hebriden; sie wurde 1803 entdeckt, 1827 von D Urville untersucht; die drei größten Inseln der Gruppe sind: Britannia, Chabrol u. Holgan … Pierer’s Universal-Lexikon

-

loyalty — I noun adherence, adherency, allegiance, attachment, bond, compliance, constancy, dedication, dependability, devotedness, devotion, duty, faithfulness, fealty, fidelitas, fidelity, fides, good faith, group feeling, incorruptibility, obedience,… … Law dictionary

-

loyalty — *fidelity, allegiance, fealty, devotion, piety Analogous words: trueness or truth, faithfulness, constancy, staunchness, steadfastness (see corresponding adjectives at FAITHFUL): *attachment, affection, love Antonyms: disloyalty Contrasted words … New Dictionary of Synonyms

-

loyalty — [n] faithfulness, dependability adherence, allegiance, ardor, attachment, bond, conscientiousness, constancy, devotedness, devotion, duty, earnestness, faith, fealty, fidelity, homage, honesty, honor, incorruptibility, integrity, inviolability,… … New thesaurus

-

loyalty — ► NOUN (pl. loyalties) 1) the state of being loyal. 2) a strong feeling of support or allegiance … English terms dictionary

-

loyalty — [loi′əltē] n. pl. loyalties [ME loyaulte < OFr loialte] quality, state, or instance of being loyal; faithfulness or faithful adherence to a person, government, cause, duty, etc. SYN. ALLEGIANCE … English World dictionary

-

Loyalty — For other uses, see Loyalty (disambiguation). Loyalty is faithfulness or a devotion to a person, country, group, or cause (Philosophers disagree as to what things one can be loyal to. Some, as explained in more detail below, argue that one can be … Wikipedia

English[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- lealty (archaic, Scotland)

- loialty (archaic)

- loyaltie (obsolete)

Etymology[edit]

From Middle English loialte, borrowed from Old French loialte, loiauté (Modern loyauté) from loial + -té.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ˈlɔɪəlti/

- Hyphenation: loy‧al‧ty

Noun[edit]

loyalty (countable and uncountable, plural loyalties)

- The state of being loyal; fidelity.

-

brand loyalty

-

- Faithfulness or devotion to some person, cause or nation.

-

He showed loyalty to his local football club after successive relegations.

-

2021 January 5, Luttig, J. Michael, Twitter[1], archived from the original on 05 January 2021; republished as Washington Post[2], January 5, 2021:

-

The only responsibility and power of the Vice President under the Constitution is to faithfully count the electoral college votes as they have been cast.

The Constitution does not empower the Vice President to alter in any way the votes that have been cast, either by rejecting certain of them or otherwise.

How the Vice President discharges this constitutional obligation is not a question of his loyalty to the President any more than it would be a test of a President’s loyalty to his Vice President

whether the President assented to the impeachment and prosecution of his Vice President for the commission of high crimes while in office.

No President and no Vice President would—or should—consider either event as a test of political loyalty of one to the other.

And if either did, he would have to accept that political loyalty must yield to constitutional obligation.

Neither the President nor the Vice President has any higher loyalty than to the Constitution.

-

-

Synonyms[edit]

- trueness

Antonyms[edit]

- disloyalty

Derived terms[edit]

- loyalty card

Translations[edit]

the state of being loyal; fidelity

- Albanian: besnikëri (sq) f

- Arabic: وَفَاء m (wafāʔ), إِخْلَاص (ar) m (ʔiḵlāṣ)

- Armenian: հավատարմություն (hy) (havatarmutʿyun)

- Asturian: llealtá f

- Azerbaijani: vəfa (az), sədaqət (az), sadiqlik

- Belarusian: ве́рнасць f (vjérnascʹ), лая́льнасць f (lajálʹnascʹ), адда́насць f (addánascʹ)

- Bulgarian: вя́рност (bg) f (vjárnost), лоя́лност (bg) f (lojálnost), пре́даност (bg) f (prédanost)

- Burmese: သစ္စာ (my) (sacca)

- Catalan: lleialtat (ca) f

- Chinese:

- Mandarin: 忠誠/忠诚 (zh) (zhōngchéng), 忠心 (zh) (zhōngxīn)

- Czech: věrnost f

- Danish: loyalitet c

- Dutch: trouw (nl) m, loyaliteit (nl) f

- Esperanto: fideleco

- Estonian: ustavus, lojaalsus

- Finnish: lojaalius (fi), uskollisuus (fi), luotettavuus (fi)

- French: loyauté (fr) f

- Friulian: lealtât f

- Galician: lealdade (gl) f

- Georgian: ერთგულება (ertguleba), თავდადება (tavdadeba), ლოიალურობა (loialuroba)

- German: Treue (de) f, Loyalität (de) f

- Hebrew: נֶאֱמָנוּת (he) f (ne’emanút)

- Hindi: निष्ठा (hi) f (niṣṭhā), वफ़ा f (vafā)

- Hungarian: hűség (hu)

- Indonesian: kesetiaan (id)

- Irish: dílseacht f

- Italian: lealtà (it) f

- Japanese: 忠誠心 (ちゅうせいしん, chūseishin), 忠誠 (ja) (ちゅうせい, chūsei), 忠義 (ja) (ちゅうぎ, chūgi)

- Kazakh: адалдық (adaldyq)

- Khmer: ចិត្តភក្តី (cət phĕəʼktəy), ភក្តីភាព (phĕəʼkdəyphiəp)

- Korean: 충실 (chungsil), 충성 (ko) (chungseong), 충성심 (chungseongsim)

- Kurdish:

- Northern Kurdish: dilsozî (ku), sozdarî (ku), wefa (ku), sedaqet (ku)

- Kyrgyz: берилгендик (ky) (berilgendik)

- Latin: fides f

- Latvian: lojalitāte (lv) f, uzticība f

- Lithuanian: ištikimybė f, lojalumas m

- Macedonian: верност f (vernost), лојалност f (lojalnost)

- Malay: kesetiaan

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: lojalitet m

- Nynorsk: lojalitet m

- Occitan: leialtat (oc) f

- Old English: trēow f

- Pashto: وفا f (wafã), وفاداري f (wafādārí)

- Persian: وفاداری (fa) (vafâdâri), وفا (fa) (vafâ)

- Polish: lojalność (pl) f, wierność (pl) f

- Portuguese: lealdade (pt) f

- Romanian: loialitate (ro) f

- Russian: ве́рность (ru) f (vérnostʹ), лоя́льность (ru) f (lojálʹnostʹ), пре́данность (ru) f (prédannostʹ)

- Scots: lealty

- Scottish Gaelic: dìlseachd f

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: ве́рно̄ст f, вје́рно̄ст f, о̏да̄но̄ст f

- Roman: vérnōst (sh) f, vjérnōst (sh) f, ȍdānōst (sh) f

- Sicilian: lialtà f, lialtati f

- Slovak: vernosť f

- Slovene: vdanost f, zvestoba (sl) f

- Spanish: lealtad (es) f

- Swedish: lojalitet (sv) c, trofasthet (sv) c

- Tajik: вафодорӣ (vafodorī), вафо (tg) (vafo)

- Thai: ความซื่อสัตย์ (th) (kwaam-sʉ̂ʉ-sàt), ความซื่อ (th) (kwaam-sʉ̂ʉ), ความภักดี (kwaam-pák-dii)

- Turkish: sadakat (tr), vefa (tr)

- Turkmen: wepalylyk

- Ukrainian: ві́рність f (vírnistʹ), лоя́льність f (lojálʹnistʹ), ві́дданість f (víddanistʹ)

- Urdu: وفا f (vafā), وفاداری f (vafādārī)

- Uyghur: ۋاپادارلىق (wapadarliq), سادىقلىق (sadiqliq)

- Uzbek: sadoqat (uz), vafo (uz), sodiqlik (uz), vafodorlik (uz)

- Vietnamese: lòng trung thành

- Welsh: gwrogaeth f

faithfulness or devotion to some person, cause or nation

- Chinese:

- Mandarin: 诚信 (zh) (chéngxìn), 忠信 (zh) (zhōngxìn), 丹心 (zh) (dānxīn)

- Danish: loyalitet c

- Finnish: lojaalius (fi), uskollisuus (fi)

- French: loyauté (fr) f

- Georgian: ერთგულება (ertguleba)

- German: Treue (de) f, Loyalität (de) f

- Irish: dílseacht f

- Italian: lealtà (it) f

- Korean: 충성 (ko) (chungseong)

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: lojalitet m

- Nynorsk: lojalitet m

- Old English: trēow f

- Polish: lojalność (pl) f

- Portuguese: lealdade (pt) f

- Russian: ве́рность (ru) f (vérnostʹ), лоя́льность (ru) f (lojálʹnostʹ)

- Scottish Gaelic: dìlseachd f

- Spanish: lealtad (es) m

- Swedish: lojalitet (sv) c, trofasthet (sv) c

- Thai: please add this translation if you can

Translations to be checked

- Georgian: (please verify) ლოიალობა (loialoba)

See also[edit]

- allegiance

- fealty

- fidelity

Content

- What is Loyalty:

- Loyalty as value

- Loyalty phrases

- Loyalty and fidelity

- Brand loyalty

What is Loyalty:

Known as loyalty to the character of a loyal person, thing or animal. The term of loyalty expresses a feeling of respect and fidelity towards a person, commitment, community, organizations, moral principles, among others.

The term loyalty comes from the Latin «Legalis» which means “respect for the law”.

The term loyal is an adjective used to identify a faithful individual based on their actions or behavior. That is why a loyal person is one who is characterized by being dedicated, and compliant and even when circumstances are adverse, as well as defending what he believes in, for example: a project.

Loyalty is synonymous with nobility, rectitude, honesty, honesty, among other moral and ethical values that allow to develop strong social and / or friendship relationships where a very solid bond of trust is created, and respect is automatically generated in individuals.

Nevertheless, the opposite of loyalty is treason, It is the fault that a person commits by virtue of the breach of his word or infidelity. Lack of loyalty describes a person who cheats on his peers, family, and exposes his own good repute.

See also: Raise crows and they will put out your eyes.

Loyalty is a characteristic that is not only present between individuals, but also between animals, especially dogs, cats and horses. All this, in gratitude for the affection and protection that human beings offer him.

The term of loyalty can be placed in different contexts such as work, friendship relationships, love affairs, among others, but loyalty should not be confused with patriotism since not all loyal people are patriotic, because patriotism is love of the country while that loyalty to the homeland is a feeling that many countries should awaken to citizens.

The word loyalty translated into English is loyalty.

See also Homeland.

Loyalty as value

Loyalty as a value is a virtue that unfolds in our conscience, in the commitment to defend and be faithful to what we believe and in whom we believe. Loyalty is a virtue that consists of obedience to the rules of fidelity, honor, gratitude and respect for something or someone, whether it be towards a person, animal, government, community, among others.

In reference to this point, some philosophers maintain that an individual can be loyal to a set of things, while others maintain that one is only loyal to another person since this term refers exclusively to interpersonal relationships.

However, in a friendship it is not enough only the value of loyalty but also sincerity, respect, honesty, love, among other values must be present.

See also Values.

Loyalty phrases

- «Love and loyalty run deeper than blood.» Richelle mead

- «Where there is loyalty, weapons are useless.» Paulo Coelho

- “You don’t earn loyalty in a day. You earn it day by day. » Jeffrey Gitomer.

- “Loyalty is a trademark. Those who have it, give it away for free. » Ellen J. Barrier.

Loyalty and fidelity

First of all, loyalty and fidelity are two values necessary for strong relationships. However, both terms are not seen as synonyms, since some authors indicate that loyalty is part of loyalty.

Loyalty is a value that consists of respect, obedience, care and defense of what is believed and in whom it is believed, it can be to a cause, project, or person. For its part, fidelity is the power or virtue of fulfilling promises, despite changes in ideas, convictions or contexts. As such, fidelity is the ability not to cheat, and not betray the other people around you, so you do not break your given word.

Brand loyalty

In the world of marketing, brand loyalty indicates the continuous purchases of a product or service as a result of the value, emotional bond and trust between company — client. For this, it is essential that the products have an influence on the lives of customers, so that they are the brand ambassadors themselves.

However, to achieve loyalty it is necessary to use a set of strategies, especially communication by the seller or company, being dispensable the use of advertising to show the product and / or service which through social networks is very easy, safe and fast. Also, create an interaction between the client and the company to achieve communication and knowledge of the strengths and weaknesses of the product, which allows its improvement to achieve full customer satisfaction.

Meaning loyalty

What does loyalty mean? Here you find 8 meanings of the word loyalty. You can also add a definition of loyalty yourself

1 |

0 c. 1400, from Old French loialte, leaute «loyalty, fidelity; legitimacy; honesty; good quality» (Modern French loyauté), from loial (see loyal). The Medieval Latin word was legalitas. The e [..]

|

2 |

0 loyaltyfaithfulness or consistency.

|

3 |

0 loyaltythe quality of being loyal feelings of allegiance commitment: the act of binding yourself (intellectually or emotionally) to a course of action; &quot;his long commitment to public service& [..]

|

4 |

0 loyaltythe level of solidarity, faithfulness or allegiance to a group or individual.

|

5 |

0 loyaltybeing faithful.

|

6 |

0 loyaltyfidelitas

|

7 |

0 loyaltyDedication or commitment shown by employees to Organizations or institutions where they Work.

|

8 |

0 loyaltyFrom the English word, which was originally borrowed from Old French loiauté, a derivative of loial "loyal", itself derived from Latin legalis "legal".

|

Dictionary.university is a dictionary written by people like you and me.

Please help and add a word. All sort of words are welcome!

Add meaning

For other uses, see Loyalty (disambiguation).

Loyalty is faithfulness or a devotion to a person, country, group, or cause (Philosophers disagree as to what things one can be loyal to. Some, as explained in more detail below, argue that one can be loyal to a broad range of things, whilst others argue that it is only possible for loyalty to be to another person and that it is strictly interpersonal.)

There are many aspects to loyalty. John Kleinig, professor of Philosophy at City University of New York, observes that over the years the idea has been treated by creative writers from Aeschylus through John Galsworthy to Conrad, by psychologists, psychiatrists, sociologists, scholars of religion, political economists, scholars of business and marketing, and — most particularly — by political theorists, who deal with it in terms of loyalty oaths and patriotism. As a philosophical concept, loyalty was largely untreated by philosophers until the work of Josiah Royce, the «grand exception» in Kleinig’s words.[1] John Ladd, professor of Philosophy at Brown University writing in the Macmillan Encyclopaedia of Philosophy in 1967, observes that by that time the subject had received «scant attention in philosophical literature». This he attributed to «odious» associations that the subject had with nationalism, including the nationalism of Nazism, and with the metaphysics of idealism, which he characterized as «obsolete». He argued that such associations were, however, faulty, and that the notion of loyalty is «an essential ingredient in any civilized and humane system of morals».[2] Kleinig observes that from the 1980s onwards, the subject gained attention, with philosophers variously relating it to (amongst other things) professional ethics, whistleblowing, friendship, and virtue theory.[1]

Contents

- 1 Early concepts

- 1.1 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica

- 1.2 Biblical and Christian views

- 2 Josiah Royce’s conception

- 3 Misplaced loyalty

- 4 Concepts from the mid-20th century onwards

- 4.1 The proper object of loyalty

- 4.2 Multiplicity, disloyalty, and whether loyalty is exclusionary

- 4.3 Other dimensions

- 5 In relation to other subjects

- 5.1 Patriotism

- 5.2 Whistleblowing

- 5.3 Marketing

- 6 In the Bible

- 7 In animals

- 8 References

- 9 Further reading

Early concepts

1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica

The Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition defines loyalty as «allegiance to the sovereign or established government of one’s country» and also «personal devotion and reverence to the sovereign and royal family». It traces the word «loyalty» to the 15th century, noting that then it primarily referred to fidelity in service, in love, or to an oath that one has made. The meaning that the Britannica gives as primary, it attributes to a shift during the 16th century, noting that the origin of the word is in the Old French «loialte», that is in turn rooted in the Latin «lex», meaning «law». One who is loyal, in the feudal sense of fealty, is one who is lawful (as opposed to an outlaw), who has full legal rights as a consequence of faithful allegiance to a feudal lord. Hence the 1911 Britannica derived its (early 20th century) primary meaning of loyalty to a monarch.[3] This definition of loyalty based upon the word’s etymology is echoed by Vandekerckhove, when he relates loyalty and whistleblowing (more on which below).[4]

Biblical and Christian views

In the Christian Bible, Jesus states «Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and unto God the things that are God’s.» However, it acknowledges a limit to the scope of that authority. There is a sphere beyond the political sphere, in the Christian view, and where loyalty to authority conflicts with loyalty to God, the latter takes precedence.[5] Moreover, Christianity rejects the notion of dual loyalty. In the Gospel of Matthew 6:24, Jesus states «No one can serve two masters. Either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and mammon». This relates to the authority of a master over his servants (as per Ephesians 6:5), who according to (Biblical) law owe undivided loyalty to their master (as per Leviticus 25:44–46).[6]

Josiah Royce’s conception