Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry.[1] In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include oral literature, much of which has been transcribed.[2] Literature is a method of recording, preserving, and transmitting knowledge and entertainment, and can also have a social, psychological, spiritual, or political role.

Literature, as an art form, can also include works in various non-fiction genres, such as biography, diaries, memoir, letters, and essays. Within its broad definition, literature includes non-fictional books, articles or other printed information on a particular subject.[3][4]

Etymologically, the term derives from Latin literatura/litteratura «learning, a writing, grammar,» originally «writing formed with letters,» from litera/littera «letter».[5] In spite of this, the term has also been applied to spoken or sung texts.[6][7] Literature is often referred to synecdochically as «writing,» and poetically as «the craft of writing» or simply «the craft.» Syd Field described his discipline, screenwriting, as «a craft that occasionally rises to the level of art.»[8]

Developments in print technology have allowed an ever-growing distribution and proliferation of written works, which now includes electronic literature.

Definitions[edit]

Definitions of literature have varied over time.[9] In Western Europe, prior to the 18th century, literature denoted all books and writing. Literature can be seen as returning to older, more inclusive notions, so that cultural studies, for instance, include, in addition to canonical works, popular and minority genres. The word is also used in reference to non-written works: to «oral literature» and «the literature of preliterate culture».

A value judgment definition of literature considers it as consisting solely of high quality writing that forms part of the belles-lettres («fine writing») tradition.[10] An example of this is in the (1910–11) Encyclopædia Britannica that classified literature as «the best expression of the best thought reduced to writing».[11]

History[edit]

Oral literature[edit]

The use of the term «literature» here is a little problematic because of its origins in the Latin littera, “letter,” essentially writing. Alternatives such as «oral forms» and «oral genres» have been suggested but the word literature is widely used.[12]

Australian Aboriginal culture has thrived on oral traditions and oral histories passed down through tens of thousands of years.

In a study published in February 2020, new evidence showed that both Budj Bim and Tower Hill volcanoes erupted between 34,000 and 40,000 years ago.[13] Significantly, this is a «minimum age constraint for human presence in Victoria», and also could be interpreted as evidence for the oral histories of the Gunditjmara people, an Aboriginal Australian people of south-western Victoria, which tell of volcanic eruptions being some of the oldest oral traditions in existence.[14] An axe found underneath volcanic ash in 1947 had already proven that humans inhabited the region before the eruption of Tower Hill.[13]

Oral literature is an ancient human tradition found in «all corners of the world».[15] Modern archaeology has been unveiling evidence of the human efforts to preserve and transmit arts and knowledge that depended completely or partially on an oral tradition, across various cultures:

The Judeo-Christian Bible reveals its oral traditional roots; medieval European manuscripts are penned by performing scribes; geometric vases from archaic Greece mirror Homer’s oral style. (…) Indeed, if these final decades of the millennium have taught us anything, it must be that oral tradition never was the other we accused it of being; it never was the primitive, preliminary technology of communication we thought it to be. Rather, if the whole truth is told, oral tradition stands out as the single most dominant communicative technology of our species as both a historical fact and, in many areas still, a contemporary reality.[15]

The earliest poetry is believed to have been recited or sung, employed as a way of remembering history, genealogy, and law.[16]

In Asia, the transmission of folklore, mythologies as well as scriptures in ancient India, in different Indian religions, was by oral tradition, preserved with precision with the help of elaborate mnemonic techniques.[17]

The early Buddhist texts are also generally believed to be of oral tradition, with the first by comparing inconsistencies in the transmitted versions of literature from various oral societies such as the Greek, Serbia and other cultures, then noting that the Vedic literature is too consistent and vast to have been composed and transmitted orally across generations, without being written down.[18] According to Goody, the Vedic texts likely involved both a written and oral tradition, calling it a «parallel products of a literate society».[19]

All ancient Greek literature was to some degree oral in nature, and the earliest literature was completely so.[20] Homer’s epic poetry, states Michael Gagarin, was largely composed, performed and transmitted orally.[21] As folklores and legends were performed in front of distant audiences, the singers would substitute the names in the stories with local characters or rulers to give the stories a local flavor and thus connect with the audience, but making the historicity embedded in the oral tradition as unreliable.[22] The lack of surviving texts about the Greek and Roman religious traditions have led scholars to presume that these were ritualistic and transmitted as oral traditions, but some scholars disagree that the complex rituals in the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations were an exclusive product of an oral tradition.[23]

Writing systems are not known to have existed among Native North Americans before contact with Europeans. Oral storytelling traditions flourished in a context without the use of writing to record and preserve history, scientific knowledge, and social practices.[24] While some stories were told for amusement and leisure, most functioned as practical lessons from tribal experience applied to immediate moral, social, psychological, and environmental issues.[25] Stories fuse fictional, supernatural, or otherwise exaggerated characters and circumstances with real emotions and morals as a means of teaching. Plots often reflect real life situations and may be aimed at particular people known by the story’s audience. In this way, social pressure could be exerted without directly causing embarrassment or social exclusion.[26] For example, rather than yelling, Inuit parents might deter their children from wandering too close to the water’s edge by telling a story about a sea monster with a pouch for children within its reach.[27]

See also African literature#Oral literature

Oratory[edit]

Oratory or the art of public speaking «was for long considered a literary art».[3] From Ancient Greece to the late 19th century, rhetoric played a central role in Western education in training orators, lawyers, counselors, historians, statesmen, and poets.[28][note 1]

Writing[edit]

Around the 4th millennium BC, the complexity of trade and administration in Mesopotamia outgrew human memory, and writing became a more dependable method of recording and presenting transactions in a permanent form.[30] Though in both ancient Egypt and Mesoamerica, writing may have already emerged because of the need to record historical and environmental events. Subsequent innovations included more uniform, predictable, legal systems, sacred texts, and the origins of modern practices of scientific inquiry and knowledge-consolidation, all largely reliant on portable and easily reproducible forms of writing.

Early written literature[edit]

Ancient Egyptian literature,[31] along with Sumerian literature, are considered the world’s oldest literatures.[32] The primary genres of the literature of ancient Egypt—didactic texts, hymns and prayers, and tales—were written almost entirely in verse;[33] By the Old Kingdom (26th century BC to 22nd century BC), literary works included funerary texts, epistles and letters, hymns and poems, and commemorative autobiographical texts recounting the careers of prominent administrative officials. It was not until the early Middle Kingdom (21st century BC to 17th century BC) that a narrative Egyptian literature was created.[34]

Many works of early periods, even in narrative form, had a covert moral or didactic purpose, such as the Sanskrit Panchatantra.200 BC – 300 AD, based on older oral tradition.[35][36] Drama and satire also developed as urban culture provided a larger public audience, and later readership, for literary production. Lyric poetry (as opposed to epic poetry) was often the speciality of courts and aristocratic circles, particularly in East Asia where songs were collected by the Chinese aristocracy as poems, the most notable being the Shijing or Book of Songs (1046–c.600 BC).[37][38][39]

In ancient China, early literature was primarily focused on philosophy, historiography, military science, agriculture, and poetry. China, the origin of modern paper making and woodblock printing, produced the world’s first print cultures.[40] Much of Chinese literature originates with the Hundred Schools of Thought period that occurred during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (769‒269 BC).[41] The most important of these include the Classics of Confucianism, of Daoism, of Mohism, of Legalism, as well as works of military science (e.g. Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, c.5th century BC)) and Chinese history (e.g. Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian, c.94 BC). Ancient Chinese literature had a heavy emphasis on historiography, with often very detailed court records. An exemplary piece of narrative history of ancient China was the Zuo Zhuan, which was compiled no later than 389 BC, and attributed to the blind 5th-century BC historian Zuo Qiuming.[42]

In ancient India, literature originated from stories that were originally orally transmitted. Early genres included drama, fables, sutras and epic poetry. Sanskrit literature begins with the Vedas, dating back to 1500–1000 BC, and continues with the Sanskrit Epics of Iron Age India.[43][44] The Vedas are among the oldest sacred texts. The Samhitas (vedic collections) date to roughly 1500–1000 BC, and the «circum-Vedic» texts, as well as the redaction of the Samhitas, date to c. 1000‒500 BC, resulting in a Vedic period, spanning the mid-2nd to mid 1st millennium BC, or the Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age.[45] The period between approximately the 6th to 1st centuries BC saw the composition and redaction of the two most influential Indian epics, the Mahabharata[46][47] and the Ramayana,[48] with subsequent redaction progressing down to the 4th century AD. Other major literary works are Ramcharitmanas[49] & Krishnacharitmanas.

The earliest known Greek writings are Mycenaean (c.1600–1100 BC), written in the Linear B syllabary on clay tablets. These documents contain prosaic records largely concerned with trade (lists, inventories, receipts, etc.); no real literature has been discovered.[50][51] Michael Ventris and John Chadwick, the original decipherers of Linear B, state that literature almost certainly existed in Mycenaean Greece,[51] but it was either not written down or, if it was, it was on parchment or wooden tablets, which did not survive the destruction of the Mycenaean palaces in the twelfth century BC.[51]

Homer’s epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are central works of ancient Greek literature. It is generally accepted that the poems were composed at some point around the late eighth or early seventh century BC.[52] Modern scholars consider these accounts legendary.[53][54][55] Most researchers believe that the poems were originally transmitted orally.[56] From antiquity until the present day, the influence of Homeric epic on Western civilization has been great, inspiring many of its most famous works of literature, music, art and film.[57] The Homeric epics were the greatest influence on ancient Greek culture and education; to Plato, Homer was simply the one who «has taught Greece» – ten Hellada pepaideuken.[58][59] Hesiod’s Works and Days (c.700 BC) and Theogony are some of the earliest, and most influential, of ancient Greek literature. Classical Greek genres included philosophy, poetry, historiography, comedies and dramas. Plato (428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) and Aristotle (384–322 BC) authored philosophical texts that are the foundation of Western philosophy, Sappho (c. 630 – c. 570 BC) and Pindar were influential lyric poets, and Herodotus (c. 484 – c. 425 BC) and Thucydides were early Greek historians. Although drama was popular in ancient Greece, of the hundreds of tragedies written and performed during the classical age, only a limited number of plays by three authors still exist: Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. The plays of Aristophanes (c. 446 – c. 386 BC) provide the only real examples of a genre of comic drama known as Old Comedy, the earliest form of Greek Comedy, and are in fact used to define the genre.[60]

The Hebrew religious text, the Torah, is widely seen as a product of the Persian period (539–333 BC, probably 450–350 BC).[61] This consensus echoes a traditional Jewish view which gives Ezra, the leader of the Jewish community on its return from Babylon, a pivotal role in its promulgation.[62] This represents a major source of Christianity’s Bible, which has had a major influence on Western literature.[63]

The beginning of Roman literature dates to 240 BC, when a Roman audience saw a Latin version of a Greek play.[64] Literature in Latin would flourish for the next six centuries, and includes essays, histories, poems, plays, and other writings.

The Qur’an (610 AD to 632 AD),[65] the main holy book of Islam, had a significant influence on the Arab language, and marked the beginning of Islamic literature. Muslims believe it was transcribed in the Arabic dialect of the Quraysh, the tribe of Muhammad.[26][66] As Islam spread, the Quran had the effect of unifying and standardizing Arabic.[26]

Theological works in Latin were the dominant form of literature in Europe typically found in libraries during the Middle Ages. Western Vernacular literature includes the Poetic Edda and the sagas, or heroic epics, of Iceland, the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf, and the German Song of Hildebrandt. A later form of medieval fiction was the romance, an adventurous and sometimes magical narrative with strong popular appeal.[67]

Controversial, religious, political and instructional literature proliferated during the European Renaissance as a result of the Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press[68] around 1440, while the Medieval romance developed into the novel,[69]

Publishing[edit]

Publishing became possible with the invention of writing but became more practical with the invention of printing. Prior to printing, distributed works were copied manually, by scribes.

The Chinese inventor Bi Sheng made movable type of earthenware c. 1045. Then c.1450, Johannes Gutenberg independently invented movable type in Europe. This invention gradually made books less expensive to produce and more widely available.

Early printed books, single sheets, and images created before 1501 in Europe are known as incunables or incunabula. «A man born in 1453, the year of the fall of Constantinople, could look back from his fiftieth year on a lifetime in which about eight million books had been printed, more perhaps than all the scribes of Europe had produced since Constantine founded his city in A.D. 330.»[70]

Eventually, printing enabled other forms of publishing besides books. The history of modern newspaper publishing started in Germany in 1609, with publishing of magazines following in 1663.

University discipline[edit]

In England[edit]

In England in the late 1820s, growing political and social awareness, «particularly among the utilitarians and Benthamites, promoted the possibility of including courses in English literary study in the newly formed London University». This further developed into the idea of the study of literature being «the ideal carrier for the propagation of the humanist cultural myth of a well educated, culturally harmonious nation».[71]

America[edit]

Women and literature[edit]

The widespread education of women was not common until the nineteenth century, and because of this literature until recently was mostly male dominated.[72]

George Sand was an idea. She has a unique place in our age.

Others are great men … she was a great woman.

Victor Hugo, Les funérailles de George Sand[73]

There were few English-language women poets whose names are remembered until the twentieth century. In the nineteenth century some names that stand out are Emily Brontë, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Emily Dickinson (see American poetry). But while generally women are absent from the European cannon of Romantic literature, there is one notable exception, the French novelist and memoirist Amantine Dupin (1804 – 1876) best known by her pen name George Sand.[74][75] One of the more popular writers in Europe in her lifetime,[76] being more renowned than both Victor Hugo and Honoré de Balzac in England in the 1830s and 1840s,[77] Sand is recognised as one of the most notable writers of the European Romantic era. Jane Austen (1775 – 1817) is the first major English woman novelist, while Aphra Behn is an early female dramatist.

Nobel Prizes in Literature have been awarded between 1901 and 2020 to 117 individuals: 101 men and 16 women. Selma Lagerlöf (1858 – 1940) was the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, which she was awarded in 1909. Additionally, she was the first woman to be granted a membership in The Swedish Academy in 1914.[78]

Feminist scholars have since the twentieth century sought expand the literary canon to include more women writers.

Children’s literature[edit]

A separate genre of children’s literature only began to emerge in the eighteenth century, with the development of the concept of childhood.[80]: x–xi The earliest of these books were educational books, books on conduct, and simple ABCs—often decorated with animals, plants, and anthropomorphic letters.[81]

Aesthetics[edit]

Literary theory[edit]

A fundamental question of literary theory is «what is literature?» – although many contemporary theorists and literary scholars believe either that «literature» cannot be defined or that it can refer to any use of language.[82]

Literary fiction[edit]

Literary fiction is a term used to describe fiction that explores any facet of the human condition, and may involve social commentary. It is often regarded as having more artistic merit than genre fiction, especially the most commercially oriented types, but this has been contested in recent years, with the serious study of genre fiction within universities.[83]

The following, by the award-winning British author William Boyd on the short story, might be applied to all prose fiction:

[short stories] seem to answer something very deep in our nature as if, for the duration of its telling, something special has been created, some essence of our experience extrapolated, some temporary sense has been made of our common, turbulent journey towards the grave and oblivion.[84]

The very best in literature is annually recognized by the Nobel Prize in Literature, which is awarded to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, produced «in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction» (original Swedish: den som inom litteraturen har producerat det mest framstående verket i en idealisk riktning).[85][86]

The value of imaginative literature[edit]

Some researchers suggest that literary fiction can play a role in an individual’s psychological development.[87] Psychologists have also been using literature as a therapeutic tool.[88][89] Psychologist Hogan argues for the value of the time and emotion that a person devotes to understanding a character’s situation in literature;[90] that it can unite a large community by provoking universal emotions, as well as allowing readers access to different cultures, and new emotional experiences.[91] One study, for example, suggested that the presence of familiar cultural values in literary texts played an important impact on the performance of minority students.[92]

Psychologist Maslow’s ideas help literary critics understand how characters in literature reflect their personal culture and the history.[93] The theory suggests that literature helps an individual’s struggle for self-fulfillment.[94][95]

The influence of religious texts[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2020) |

Religion has had a major influence on literature, through works like the Vedas, the Torah, the Bible,[96]

and the Qur’an.[97][98][99]

The King James Version of the Bible has been called «the most influential version of the most influential book in the world, in what is now its most influential language», «the most important book in English religion and culture», and «the most celebrated book in the English-speaking world»[citation needed] — principally because of its literary style and widespread distribution. Prominent atheist figures such as the late Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins have praised the King James Version as being «a giant step in the maturing of English literature» and «a great work of literature», respectively, with Dawkins then adding, «A native speaker of English who has never read a word of the King James Bible is verging on the barbarian».[100][101]

Societies in which preaching has great importance, and those in which religious structures and authorities have a near-monopoly of reading and writing and/or a censorship role, may impart a religious gloss to much of the literature those societies produce or retain — as for example in the European Middle Ages. The traditions of close study of religious texts has furthered the development of techniques and theories in literary studies.

Types[edit]

Poetry[edit]

Poetry has traditionally been distinguished from prose by its greater use of the aesthetic qualities of language, including musical devices such as assonance, alliteration, rhyme, and rhythm, and by being set in lines and verses rather than paragraphs, and more recently its use of other typographical elements.[102][103][104] This distinction is complicated by various hybrid forms such as sound poetry, concrete poetry and prose poem,[105] and more generally by the fact that prose possesses rhythm.[106] Abram Lipsky refers to it as an «open secret» that «prose is not distinguished from poetry by lack of rhythm».[107]

Prior to the 19th century, poetry was commonly understood to be something set in metrical lines: «any kind of subject consisting of Rhythm or Verses».[102] Possibly as a result of Aristotle’s influence (his Poetics), «poetry» before the 19th century was usually less a technical designation for verse than a normative category of fictive or rhetorical art.[clarification needed][108] As a form it may pre-date literacy, with the earliest works being composed within and sustained by an oral tradition;[109][110] hence it constitutes the earliest example of literature.

Prose[edit]

As noted above, prose generally makes far less use of the aesthetic qualities of language than poetry.[103][104][111] However, developments in modern literature, including free verse and prose poetry have tended to blur the differences, and American poet T.S. Eliot suggested that while: «the distinction between verse and prose is clear, the distinction between poetry and prose is obscure».[112] There are verse novels, a type of narrative poetry in which a novel-length narrative is told through the medium of poetry rather than prose. Eugene Onegin (1831) by Alexander Pushkin is the most famous example.[113]

On the historical development of prose, Richard Graff notes that «[In the case of ancient Greece] recent scholarship has emphasized the fact that formal prose was a comparatively late development, an «invention» properly associated with the classical period».[114]

Latin was a major influence on the development of prose in many European countries. Especially important was the great Roman orator Cicero.[115] It was the lingua franca among literate Europeans until quite recent times, and the great works of Descartes (1596 – 1650), Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626), and Baruch Spinoza (1632 – 1677) were published in Latin. Among the last important books written primarily in Latin prose were the works of Swedenborg (d. 1772), Linnaeus (d. 1778), Euler (d. 1783), Gauss (d. 1855), and Isaac Newton (d. 1727).

Novel[edit]

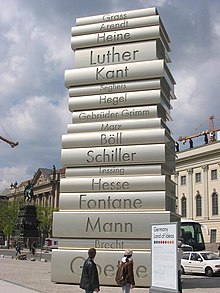

Sculpture in Berlin depicting a stack of books on which are inscribed the names of great German writers

A novel is a long fictional prose narrative. In English, the term emerged from the Romance languages in the late 15th century, with the meaning of «news»; it came to indicate something new, without a distinction between fact or fiction.[116] The romance is a closely related long prose narrative. Walter Scott defined it as «a fictitious narrative in prose or verse; the interest of which turns upon marvelous and uncommon incidents», whereas in the novel «the events are accommodated to the ordinary train of human events and the modern state of society».[117] Other European languages do not distinguish between romance and novel: «a novel is le roman, der Roman, il romanzo«,[118] indicates the proximity of the forms.[119]

Although there are many historical prototypes, so-called «novels before the novel»,[120] the modern novel form emerges late in cultural history—roughly during the eighteenth century.[121] Initially subject to much criticism, the novel has acquired a dominant position amongst literary forms, both popularly and critically.[119][122][123]

Novella[edit]

The publisher Melville House classifies the novella as «too short to be a novel, too long to be a short story».[124] Publishers and literary award societies typically consider a novella to be between 17,000 and 40,000 words.[125]

Short story[edit]

A dilemma in defining the «short story» as a literary form is how to, or whether one should, distinguish it from any short narrative and its contested origin,[126] that include the Bible, and Edgar Allan Poe.[127]

Graphic novel[edit]

Graphic novels and comic books present stories told in a combination of artwork, dialogue, and text.

Electronic literature[edit]

Electronic literature is a literary genre consisting of works created exclusively on and for digital devices.

Nonfiction[edit]

Common literary examples of nonfiction include, the essay; travel literature and nature writing; biography, autobiography and memoir; journalism; letters; journals; history, philosophy, economics; scientific, and technical writings.[4][128]

Nonfiction can fall within the broad category of literature as «any collection of written work», but some works fall within the narrower definition «by virtue of the excellence of their writing, their originality and their general aesthetic and artistic merits».[129]

Drama[edit]

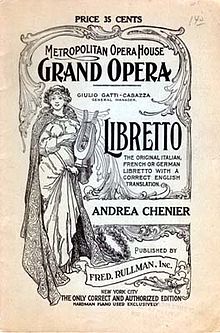

Drama is literature intended for performance.[130] The form is combined with music and dance in opera and musical theatre (see libretto). A play is a written dramatic work by a playwright that is intended for performance in a theatre; it comprises chiefly dialogue between characters. A closet drama, by contrast, is written to be read rather than to be performed; the meaning of which can be realized fully on the page.[131] Nearly all drama took verse form until comparatively recently.

The earliest form of which there exists substantial knowledge is Greek drama. This developed as a performance associated with religious and civic festivals, typically enacting or developing upon well-known historical, or mythological themes,

In the twentieth century scripts written for non-stage media have been added to this form, including radio, television and film.

Law[edit]

Law and literature[edit]

The law and literature movement focuses on the interdisciplinary connection between law and literature.

Copyright[edit]

Copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive right to make copies of a creative work, usually for a limited time.[132][133][134][135][136] The creative work may be in a literary, artistic, educational, or musical form. Copyright is intended to protect the original expression of an idea in the form of a creative work, but not the idea itself.[137][138][139]

United Kingdom[edit]

Literary works have been protected by copyright law from unauthorized reproduction since at least 1710.[140] Literary works are defined by copyright law to mean «any work, other than a dramatic or musical work, which is written, spoken or sung, and accordingly includes (a) a table or compilation (other than a database), (b) a computer program, (c) preparatory design material for a computer program, and (d) a database.»[141]

Literary works are all works of literature; that is all works expressed in print or writing (other than dramatic or musical works).[142]

United States[edit]

The copyright law of the United States has a long and complicated history, dating back to colonial times. It was established as federal law with the Copyright Act of 1790. This act was updated many times, including a major revision in 1976.

European Union[edit]

The copyright law of the European Union is the copyright law applicable within the European Union. Copyright law is largely harmonized in the Union, although country to country differences exist. The body of law was implemented in the EU through a number of directives, which the member states need to enact into their national law. The main copyright directives are the Copyright Term Directive, the Information Society Directive and the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market. Copyright in the Union is furthermore dependent on international conventions to which the European Union is a member (such as the TRIPS Agreement and conventions to which all Member States are parties (such as the Berne Convention)).

Copyright in communist countries[edit]

Copyright in Japan[edit]

Japan was a party to the original Berne convention in 1899, so its copyright law is in sync with most international regulations. The convention protected copyrighted works for 50 years after the author’s death (or 50 years after publication for unknown authors and corporations). However, in 2004 Japan extended the copyright term to 70 years for cinematographic works. At the end of 2018, as a result of the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations, the 70 year term was applied to all works.[143] This new term is not applied retroactively; works that had entered the public domain between 1999 and 2018 by expiration would remain in the public domain.

Censorship[edit]

Censorship of literature is employed by states, religious organizations, educational institutions, etc., to control what can be portrayed, spoken, performed, or written.[144] Generally such bodies attempt to ban works for political reasons, or because they deal with other controversial matters such as race, or sex.[145]

A notorious example of censorship is James Joyce’s novel Ulysses, which has been described by Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov as a «divine work of art» and the greatest masterpiece of 20th century prose.[146] It was banned in the United States from 1921 until 1933 on the grounds of obscenity. Nowadays it is a central literary text in English literature courses, throughout the world.[147]

Awards[edit]

There are numerous awards recognizing achievement and contribution in literature. Given the diversity of the field, awards are typically limited in scope, usually on: form, genre, language, nationality and output (e.g. for first-time writers or debut novels).[148]

The Nobel Prize in Literature was one of the six Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895,[149] and is awarded to an author on the basis of their body of work, rather than to, or for, a particular work itself.[note 2] Other literary prizes for which all nationalities are eligible include: the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, the Man Booker International Prize, Pulitzer Prize, Hugo Award, Guardian First Book Award and the Franz Kafka Prize.

See also[edit]

- Outline of literature

- Index of literature articles

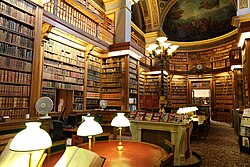

- Library

- Literary agent

- Literary element

- Literary magazine

- Reading

- Rhetorical modes

- Science fiction § As serious literature

- Vernacular literature

Notes[edit]

- ^ The definition of rhetoric is a controversial subject within the field and has given rise to philological battles over its meaning in Ancient Greece.[29]

- ^ However, in some instances a work has been cited in the explanation of why the award was given.

References[edit]

- ^ «Literature: definition». Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ Goody, Jack. «Oral literature». Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2020.; see also Homer.

- ^ a b Rexroth, Kenneth. «literature | Definition, Characteristics, Genres, Types, & Facts». Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ a b OED

- ^ «literature (n.)». Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ Meyer, Jim (1997). «What is Literature? A Definition Based on Prototypes». Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics and University of North Dakota Session. 41 (1). Retrieved 11 February 2014.[dead link]

- ^ Finnegan, Ruth (1974). «How Oral Is Oral Literature?». Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 37 (1): 52–64. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00094842. JSTOR 614104. S2CID 190730645. (subscription required)

- ^ Field, Syd (29 November 2005). «Introduction». Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. Delta. ISBN 978038533903.

- ^ Leitch et al., The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 28

- ^ Eagleton 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Biswas, Critique of Poetics, 538

- ^ «Oral literature». Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ a b Johnson, Sian (26 February 2020). «Study dates Victorian volcano that buried a human-made axe». ABC News. Archived from the original on 8 September 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Matchan, Erin L.; Phillips, David; Jourdan, Fred; Oostingh, Korien (2020). «Early human occupation of southeastern Australia: New insights from 40Ar/39Ar dating of young volcanoes». Geology. 48 (4): 390–394. Bibcode:2020Geo….48..390M. doi:10.1130/G47166.1. ISSN 0091-7613. S2CID 214357121.

- ^ a b John Miles Foley. «What’s in a Sign» (1999). E. Anne MacKay (ed.). Signs of Orality. BRILL Academic. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-9004112735.

- ^ Francis, Norbert (2017). Bilingual and multicultural perspectives on poetry, music and narrative Archived 10 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine: The science of art. Lanham MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- ^ Donald S. Lopez Jr. (1995). «Authority and Orality in the Mahāyāna» (PDF). Numen. Brill Academic. 42 (1): 21–47. doi:10.1163/1568527952598800. hdl:2027.42/43799. JSTOR 3270278. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ «Buddhism — The Pali canon (Tipitaka) | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ Ong, Walter J. (2002). Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-28128-7.

- ^ Reece, Steve. «Orality and Literacy: Ancient Greek Literature as Oral Literature,» in David Schenker and Martin Hose (eds.), Companion to Greek Literature (Oxford: Blackwell, 2015) 43-57. Ancient_Greek_Literature_as_Oral_Literature Archived 1 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Michael Gagarin (1999). E. Anne MacKay (ed.). Signs of Orality. BRILL Academic. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-9004112735.

- ^ Wolfgang Kullmann (1999). E. Anne MacKay (ed.). Signs of Orality. BRILL Academic. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-9004112735.

- ^ John Scheid (2006). Clifford Ando and Jörg Rüpke (ed.). Religion and Law in Classical and Christian Rome. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 17–28. ISBN 978-3-515-08854-1. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Kroeber, Karl, ed. (2004). Native American Storytelling: A Reader of Myths and Legends. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 1. ISBN 978-1-4051-1541-4.

- ^ Kroeber, Karl, ed. (2004). Native American Storytelling: A Reader of Myths and Legends. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 3. ISBN 978-1-4051-1541-4.

- ^ a b c Kroeber, Karl, ed. (2004). Native American Storytelling: A Reader of Myths and Legends. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 2. ISBN 978-1-4051-1541-4.

- ^ Doucleff, Michaeleen; Greenhalgh, Jane (13 March 2019). «How Inuit Parents Teach Kids To Control Their Anger». NPR. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ See, e.g., Thomas Conley, Rhetoric in the European Tradition (University of Chicago, 1991).

- ^ See, for instance Parlor, Burkean; Johnstone, Henry W. (1996). «On schiappa versus poulakos». Rhetoric Review. 14 (2): 438–440. doi:10.1080/07350199609389075.

- ^ Green, M.W. (1981). «The Construction and Implementation of the Cuneiform Writing System». Visible Language. 15 (4): 345–372.

- ^ Foster 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Black et al. The Literature of Ancient Sumer, xix

- ^ Foster 2001, p. 7.

- ^ Lichtheim, Miriam (1975). Ancient Egyptian Literature, vol 1. London, England: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02899-6.

- ^ Jacobs 1888, Introduction, page xv; Ryder 1925, Translator’s introduction, quoting Hertel: «the original work was composed in Kashmir, about 200 B.C. At this date, however, many of the individual stories were already ancient.»

- ^ Ryder 1925 Translator’s introduction: «The Panchatantra is a niti-shastra, or textbook of niti. The word niti means roughly «the wise conduct of life.» Western civilization must endure a certain shame in realizing that no precise equivalent of the term is found in English, French, Latin, or Greek. Many words are therefore necessary to explain what niti is, though the idea, once grasped, is clear, important, and satisfying.»

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 356.

- ^ Allan (1991), p. 39.

- ^ Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 (AD 127–200), Shipu xu 詩譜序.

- ^ A Hyatt Mayor, Prints and People, Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton, 1971, nos 1–4. ISBN 0-691-00326-2

- ^ «Chinese philosophy» Archived 2 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica, online

- ^ Lin, Liang-Hung; Ho, Yu-Ling (2009). «Confucian dynamism, culture and ethical changes in Chinese societies – a comparative study of China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong». The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 20 (11): 2402–2417. doi:10.1080/09585190903239757. ISSN 0958-5192. S2CID 153789769. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ see e.g. Radhakrishnan & Moore 1957, p. 3; Witzel, Michael, «Vedas and Upaniṣads«, in: Flood 2003, p. 68; MacDonell 2004, pp. 29–39; Sanskrit literature (2003) in Philip’s Encyclopedia. Accessed 2007-08-09

- ^ Sanujit Ghose (2011). «Religious Developments in Ancient India Archived 30 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine» in Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- ^ Gavin Flood sums up mainstream estimates, according to which the Rigveda was compiled from as early as 1500 BC over a period of several centuries. Flood 1996, p. 37

- ^ James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 399. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ T. R. S. Sharma; June Gaur; Sahitya Akademi (New Delhi, Inde). (2000). Ancient Indian Literature: An Anthology. Sahitya Akademi. p. 137. ISBN 978-81-260-0794-3. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ «Ramayana | Summary, Characters, & Facts». Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ Lutgendorf 1991, p. 1.

- ^ Chadwick, John (1967). The Decipherment of Linear B (Second ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-107-69176-6. «The glimpse we have suddenly been given of the account books of a long-forgotten people…»

- ^ a b c Ventris, Michael; Chadwick, John (1956). Documents in Mycenaean Greek. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. xxix. ISBN 978-1-107-50341-0. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ Croally, Neil; Hyde, Roy (2011). Classical Literature: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 26. ISBN 978-1136736629. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Wilson, Nigel (2013). Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. Routledge. p. 366. ISBN 978-1136788000. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Romilly, Jacqueline de (1985). A Short History of Greek Literature. University of Chicago Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0226143125. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Graziosi, Barbara (2002). Inventing Homer: The Early Reception of Epic. Cambridge University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0521809665. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Ahl, Frederick; Roisman, Hanna (1996). The Odyssey Re-formed. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801483356. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Latacz, Joachim (1996). Homer, His Art and His World. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472083534. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Too, Yun Lee (2010). The Idea of the Library in the Ancient World. OUP Oxford. p. 86. ISBN 978-0199577804. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ MacDonald, Dennis R. (1994). Christianizing Homer: The Odyssey, Plato, and the Acts of Andrew. Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0195358629. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Aristophanes: Butts K.J.Dover (ed), Oxford University Press 1970, Intro. p. x.

- ^ Frei 2001, p. 6.

- ^ Romer 2008, p. 2 and fn.3.

- ^ Riches, John (2000). The Bible: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-19-285343-1.

- ^ Duckworth, George Eckel. The nature of Roman comedy: a study in popular entertainment. Archived 4 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine University of Oklahoma Press, 1994. p. 3. Web. 15 October 2011.

- ^ Donner, Fred (2010). Muhammad and the Believers: at the Origins of Islam. London, England: Harvard University Press. pp. 153–154. ISBN 978-0-674-05097-6.

- ^ «الوثائقية تفتح ملف «اللغة العربية»«. الجزيرة الوثائقية (in Arabic). 8 September 2019. Archived from the original on 16 June 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ «Western literature — Medieval literature». Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. Cambridge University Press, 1980

- ^ Margaret Anne Doody, The True Story of the Novel. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996, rept. 1997, p. 1. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ Clapham, Michael, «Printing» in A History of Technology, Vol 2. From the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution, edd. Charles Singer et al. (Oxford 1957), p. 377. Cited from Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (Cambridge University, 1980).

- ^ «Court: Institutionalizing English Literature». oldsite.english.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ «Women and Literature». www.ibiblio.org. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Saturday Review. Saturday Review. 1876. pp. 771ff. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Hart, Kathleen (2004). Revolution and Women’s Autobiography in Nineteenth-century France. Rodopi. p. 91.

- ^ Lewis, Linda M. (2003). Germaine de Staël, George Sand, and the Victorian Woman Artist. University of Missouri Press. p. 48.

- ^ Eisler, Benita (8 June 2018). «‘George Sand’ Review: Monstre Sacré». WSJ. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ Thomson, Patricia (July 1972). «George Sand and English Reviewers: The First Twenty Years». Modern Language Review. 67 (3): 501–516. doi:10.2307/3726119. JSTOR 3726119.

- ^ Forsas-Scott, Helena (1997). Swedish Women’s Writing 1850-1995. London: The Athlone Press. p. 63. ISBN 0485910039.

- ^ …remains the most translated Italian book and, after the Bible, the most widely read… by Francelia Butler, Children’s Literature, Yale University Press, 1972.

- ^ Nikolajeva, María, ed. (1995). Aspects and Issues in the History of Children’s Literature. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-29614-7. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ •Lyons, Martyn. 2011. Books: a living history. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- ^ Sullivan, Patrick (1 January 2002). ««Reception Moments,» Modern Literary Theory, and the Teaching of Literature». Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. 45 (7): 568–577. JSTOR 40012241.

- ^ Matthew Schneider-Mayerson, «Popular Fiction Studies: The Advantages of a New Field». Studies in Popular Culture, Vol. 33, No. 1 (Fall 2010), pp. 21-3

- ^ Boyd, William. «A short history of the short story». Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ «The Nobel Prize in Literature». nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 13 July 2019.

- ^ John Sutherland (13 October 2007). «Ink and Spit». Guardian Unlimited Books. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 November 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ Oebel, Guido (2001). So-called «Alternative FLL-Approaches». Norderstedt: GRIN Verlag. ISBN 9783640187799. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ Makin, Michael; Kelly, Catriona; Shepher, David; de Rambures, Dominique (1989). Discontinuous Discourses in Modern Russian Literature. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 122. ISBN 9781349198511.

- ^ Cullingford, Cedric (1998). Children’s Literature and its Effects. London: A&C Black. p. 5. ISBN 0304700924.

- ^ Hogan 2011, p. 10.

- ^ Hogan 2011, p. 11.

- ^ Damon, William; Lerner, Richard; Renninger, Ann; Sigel, Irving (2006). Handbook of Child Psychology, Child Psychology in Practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 90. ISBN 0471272876.

- ^ Paris 1986, p. 61.

- ^ Paris 1986, p. 25.

- ^ Nezami, S.R.A. (February 2012). «The use of figures of speech as a literary device—a specific mode of expression in English literature». Language in India. 12 (2): 659–.[dead link]

- ^ Riches, John (3 January 2022) [2000]. «The Bible in high and popular culture». The Bible: a Very Short Introduction. Volume 14 in Very Short Introductions Series (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press (published 2021). p. 115. ISBN 9780198863335. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

In its various translations, [the Bible] has had a formative influence on the language, the literature, the art, the music of all the major European and North American cultures. It continues to influence popular culture in films, novels, and music.

- ^ «Islamic arts — Islamic literatures». Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Riches, John (2000). The Bible: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-19-285343-1.

- ^ «Hinduism — Vernacular literatures». Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ «When the King Saved God». Vanity Fair. 2011. Archived from the original on 24 December 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ «Why I want all our children to read the King James Bible». The Guardian. 20 May 2012. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ a b «poetry, n.» Oxford English Dictionary. OUP. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2014.(subscription required)

- ^ a b Preminger 1993, p. 938.

- ^ a b Preminger 1993, p. 939.

- ^ Preminger 1993, p. 981.

- ^ Preminger 1993, p. 979.

- ^ Lipsky, Abram (1908). «Rhythm in Prose». The Sewanee Review. 16 (3): 277–289. JSTOR 27530906. (subscription required)

- ^ Ross, «The Emergence of ‘Literature’: Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century», 398

- ^ Finnegan, Ruth H. (1977). Oral poetry: its nature, significance, and social context. Indiana University Press. p. 66.

- ^ Magoun, Francis P. Jr. (1953). «Oral-Formulaic Character of Anglo-Saxon Narrative Poetry». Speculum. 28 (3): 446–467. doi:10.2307/2847021. JSTOR 2847021. S2CID 162903356. (subscription required)

- ^ Alison Booth; Kelly J. Mays. «Glossary: P». LitWeb, the Norton Introduction to Literature Studyspace. Archived from the original on 18 March 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ Eliot T.S. ‘Poetry & Prose: The Chapbook. Poetry Bookshop: London, 1921.

- ^ For discussion of the basic categorical issues see The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993), s.v. ‘Narrative Poetry’.

- ^ Graff, Richard (2005). «Prose versus Poetry in Early Greek Theories of Style». Rhetorica. 23 (4): 303–335. doi:10.1525/rh.2005.23.4.303. JSTOR 10.1525/rh.2005.23.4.303. S2CID 144730853. (subscription required)

- ^ «Literature», Encyclopaedia Britannica. online

- ^ Sommerville, C. J. (1996). The News Revolution in England: Cultural Dynamics of Daily Information. Oxford: OUP. p. 18.

- ^ «Essay on Romance», Prose Works volume vi, p. 129, quoted in «Introduction» to Walter Scott’s Quentin Durward, ed. Susan Maning. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992, p. xxv. Romance should not be confused with Harlequin Romance.

- ^ Doody (1996), p. 15.

- ^ a b «The Novel». A Guide to the Study of Literature: A Companion Text for Core Studies 6, Landmarks of Literature. Brooklyn College. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ Goody 2006, p. 19.

- ^ Goody 2006, p. 20.

- ^ Goody 2006, p. 29.

- ^ Franco Moretti, ed. (2006). «The Novel in Search of Itself: A Historical Morphology». The Novel, Volume 2: Forms and Themes. Princeton: Princeton UP. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-691-04948-9.

- ^ Antrim, Taylor (2010). «In Praise of Short». The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ «What’s the definition of a «novella,» «novelette,» etc.?». Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. Archived from the original on 19 March 2009.

- ^ Boyd, William. «A short history of the short story». Prospect Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ Colibaba, Ştefan (2010). «The Nature of the Short Story: Attempts at Definition» (PDF). Synergy. 6 (2): 220–230. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ Susan B. Neuman; Linda B. Gambrell, eds. (2013). Quality Reading Instruction in the Age of Common Core Standards. International Reading Association. p. 46. ISBN 9780872074965. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ J. A. Cuddon, Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory,p. 472.

- ^ Elam, Kier (1980). The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama. London and New York: Methuen. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-416-72060-0.

- ^ Cody, Gabrielle H. (2007). The Columbia Encyclopedia of Modern Drama (Volume 1 ed.). New York City: Columbia University Press. p. 271.

- ^ «Definition of copyright». Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ «Definition of Copyright». Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ Nimmer on Copyright, vol. 2, § 8.01.

- ^ «Intellectual property», Black’s Law Dictionary, 10th ed. (2014).

- ^ «Understanding Copyright and Related Rights» (PDF). www.wipo.int. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ Stim, Rich (27 March 2013). «Copyright Basics FAQ». The Center for Internet and Society Fair Use Project. Stanford University. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Daniel A. Tysver. «Works Unprotected by Copyright Law». Bitlaw. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Lee A. Hollaar. «Legal Protection of Digital Information». p. Chapter 1: An Overview of Copyright, Section II.E. Ideas Versus Expression. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ The Statute of Anne 1710 and the Literary Copyright Act 1842 used the term «book». However, since 1911 the statutes have referred to literary works.

- ^ «Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988». legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ «University of London Press v. University Tutorial Press» [1916]

- ^ Agency for Cultural Affairs. 環太平洋パートナーシップ協定の法律) (PDF) (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ J. A, Cuddon, «Censorship», The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory (1977), (revised by C. E. Preston. Penguin Books, 1998, pp. 118-22.

- ^ «About Banned & Challenged Books». ala.org. 25 October 2016. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Nabokov, pp. 55, 57[full citation needed]

- ^ Ulysses has been called «the most prominent landmark in modernist literature», a work where life’s complexities are depicted with «unprecedented, and unequalled, linguistic and stylistic virtuosity». The New York Times guide to essential knowledge, 3d ed. (2011), p. 126.

- ^ John Stock; Kealey Rigden (15 October 2013). «Man Booker 2013: Top 25 literary prizes». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ «Facts on the Nobel Prize in Literature». Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

Bibliography[edit]

- A.R. Biswas (2005). Critique of Poetics (vol. 2). Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0377-1. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- Jeremy Black; Graham Cunningham; Eleanor Robson, eds. (2006). The literature of ancient Sumer. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-929633-0.

- Cain, William E.; Finke, Laurie A.; Johnson, Barbara E.; McGowan, John; Williams, Jeffrey J. (2001). Vincent B. Leitch (ed.). The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-97429-4.

- Eagleton, Terry (2008). Literary Theory: An Introduction (Anniversary, 2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-7921-8.

- Flood, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0.

- Hogan, P. Colm (2011). What Literature Teaches Us about Emotion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Foster, John Lawrence (2001), Ancient Egyptian Literature: An Anthology, Austin: University of Texas Press, p. xx, ISBN 978-0-292-72527-0

- Giraldi, William (2008). «The Novella’s Long Life» (PDF). The Southern Review: 793–801. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- Goody, Jack (2006). «From Oral to Written: An Anthropological Breakthrough in Storytelling». In Franco Moretti (ed.). The Novel, Volume 1: History, Geography, and Culture. Princeton: Princeton UP. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-691-04947-2.

- Paris, B.J. (1986). Third Force Psychology and the Study of Literature. Cranbury: Associated University Press.

- Preminger, Alex; et al. (1993). The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. US: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02123-2.

- Ross, Trevor (1996). «The Emergence of «Literature»: Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century.»» (PDF). ELH. 63 (2): 397–422. doi:10.1353/elh.1996.0019. S2CID 170813833. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

Further reading[edit]

- Bonheim, Helmut (1982). The Narrative Modes: Techniques of the Short Story. Cambridge: Brewer. An overview of several hundred short stories.

- Gillespie, Gerald (January 1967). «Novella, nouvelle, novella, short novel? — A review of terms». Neophilologus. 51 (1): 117–127. doi:10.1007/BF01511303. S2CID 162102536.

- Wheeler, L. Kip. «Periods of Literary History» (PDF). Carson-Newman University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 March 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2014. Brief summary of major periods in literary history of the Western tradition.

External links[edit]

- Project Gutenberg Online Library

- Internet Book List similar to IMDb but for books (archived 7 February 2007)

- Digital eBook Collection – Internet Archive

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions. - Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

Table of Contents

Hide

- WHAT IS LITERATURE?

- The meaning of literature.

- What are the two Major Types of Literature?

- What is the Function of Literature?

- What is the figure of speech in literature?

- what are the genres of Literature?

- Types of Drama

WHAT IS LITERATURE?

Literature doesn’t have a particular definition. The word literature is derived from the adjective “LITERATURE”, which means the ability to be able to read and write. It can also be defined as everything that is in print that gives instruction, information, and education to people in a broad sense.

The meaning of literature.

There is no particular definition of literature but literature simply mean the representation of life or literature is the mirror of life.

What are the two Major Types of Literature?

Literature is classified into two, below are types of literature;

- English literature: this is a type of literature from people who speak English as their native or their mother language. for example, literature directly from US can be classified as English literature, because it is from the origin.

- Literature in English: this can simply be explained as literature translated to English by people whose mother’s language isn’t English. for instance, literature from a country speaking a language other than English can be categorized as literature in English.

What is the Function of Literature?

- Literature educates

- Literature serves as a means of propagation of history

- Literature entertain

- Literature contributes to the use of language.

- Literature teaches morality.

- Literature stands as means of information.

What is the figure of speech in literature?

Below are the types of concepts used in literary appreciation.

1. Metaphor:

2. Simile:

3. Irony:

4. Litotes:

5. Allegory:

6. Alliteration:

7. Pun:

8. Apostrophe:

9. Oxymoron:

10. Onomatopoeia:

11. Personification:

12. Synecdoche:

13. Repetition:

14. Rhetorical question:

15. Sarcasm:

16. Diction:

17. Hyperbole:

18. Paradox:

19. Personification:

20. Synecdoche:

what are the genres of Literature?

We have three genres of literature, each of these genres has certain features that make it different from others. Below are three genres of literature;

- Prose.

- Poetry.

- Drama.

- prose: the word prose is derived from the Latin word “prorsus” which means “straight on” or “continuous”. It is also a piece of writing that goes straight forward and continues to the very end. The word prose is recognized by its use of a greater amount of words and sentences structures. The prose is made up of fictive and non-fictive work.

- poetry: this can be defined as the deployment of certain devices such as a figure of speech, feeling, rhyme and rhythm, stanzaic division, metre, subject matter in a body of words in order to express an idea.

- Drama: drama create or recreate human experience through acting. Drama is the representation of human action. Drama takes place anywhere such as, built stage, motor-park, and village square. The basic elements of drama are Plot, Character, Action, Scene, Setting, and Dialogue. The characters in a play are referred to as dramatists.

Types of Drama

Tragedy: Plays written that is based on an issue of religion, social or personal problem. In the tragedy genre, many events are crafted in a manner that is apparent to the characters. The most important thing is that it’s not a narrative because it focuses on the actions. In tragedies the protagonist has the burden of a fatal flaw. often, the protagonist displays arrogance or pride, and the story leads to an inevitable fall.

Comedy: Comedy demonstrates the concept of rebirth. Consequently, this kind of drama typically begins and end with laughter and joy. The characters in this show are portrayed in humorous and absurd ways.

Melodrama: Melodrama is a form of drama where external forces cause the issue and, sometimes, the main character is the victim in the circumstances. The good and the flawed characters are presented distinctly.

Tragicomedy: This kind of drama depicts the real life or scenario in a real manner. In this type of drama, the characters and plot aren’t judgmental and the ending is unpredictable. It is an amalgamation of comedy and tragedy.

Monologue: this is when a character makes a speech that is long to a mute audience on stage.

Are you filled? Comment below if we really add value to you. if you need our help follow this link, contact us and learn more.

Literature: A Depiction of Society

It might sound strange that what is literature’s relation with a society could be. However, literature is an integral part of any society and has a profound effect on ways and thinking of people of that society. Actually, society is the only subject matter of literature. It literally shapes a society and its beliefs. Students, who study literature, grow up to be the future of a country. Hence, it has an impact on a society and it moulds it.

According to different definitions of literature by authors, it literally does the depiction of society; therefore, we call it ‘mirror of society’. Writers use it effectively to point out the ill aspects of society that improve them. They also use it to highlight the positive aspects of a society to promote more goodwill in society.

The essays in literature often call out on the problems in a country and suggest solutions for it. Producers make films and write novels, and short stories to touch subjects like morals, mental illnesses, patriotism, etc. Through such writings, they relate all matters to society. Other genre can also present the picture of society. We should keep in mind that the picture illustrated by literature is not always true. Writers can present it to change the society in their own ways.

The Effects of Literature on a Society:

The effects of literature on a society can be both positive and negative. Because of this, the famous philosophers Aristotle and Plato have different opinions about its effect on society.

Plato was the one who started the idea of written dialogue. He was a moralist, and he did not approve of poetry because he deemed it immoral. He considered poetry as based on false ideas whereas the basis of philosophy came from reality and truth. Plato claims that, “poetry inspires undesirable emotions in society. According to him, poetry should be censored from adults and children for fear of lasting detrimental consequences” (Leitch & McGowan). He further explains it by saying, “Children have no ability to know what emotions should be tempered and which should be expressed as certain expressed emotions can have lasting consequences later in life”. He says, “Strong emotions of every kind must be avoided, in fear of them spiraling out of control and creating irreparable damage” (Leitch & McGowan). However, he did not agree with the type of poetry and wanted that to be changed. (read Plato’s attack on poetry)

Now Aristotle considers literature of all kinds to be an important part of children’s upbringing. Aristotle claims that, “poetry takes us closer to reality. He also mentioned in his writings that it teaches, warns, and shows us the consequences of bad deeds”. He was of the view that it is not necessary that poetry will arouse negative feelings. (Read Aristotle’s defense of poetry)

Therefore, the relation of literature with society is of utter importance. It might have a few negative impacts, through guided studying which we can avoid. Overall, it is the best way of passing information to the next generation and integral to learning.

- Top Definitions

- Quiz

- Related Content

- More About Literature

- Examples

- British

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

[ lit-er-uh-cher, -choor, li-truh— ]

/ ˈlɪt ər ə tʃər, -ˌtʃʊər, ˈlɪ trə- /

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

noun

writings in which expression and form, in connection with ideas of permanent and universal interest, are characteristic or essential features, as poetry, novels, history, biography, and essays.

the entire body of writings of a specific language, period, people, etc.: the literature of England.

the writings dealing with a particular subject: the literature of ornithology.

the profession of a writer or author.

any kind of printed material, as circulars, leaflets, or handbills: literature describing company products.

Archaic. polite learning; literary culture; appreciation of letters and books.

QUIZ

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE COMMON GRAMMAR DEBATES?

There are grammar debates that never die; and the ones highlighted in the questions in this quiz are sure to rile everyone up once again. Do you know how to answer the questions that cause some of the greatest grammar debates?

Which sentence is correct?

Origin of literature

First recorded in 1375–1425; late Middle English litterature, from Latin litterātūra “grammar;” see origin at literate, -ure

synonym study for literature

1. Literature, belles-lettres, letters refer to artistic writings worthy of being remembered. In the broadest sense, literature includes any type of writings on any subject: the literature of medicine; usually, however, it means the body of artistic writings of a country or period that are characterized by beauty of expression and form and by universality of intellectual and emotional appeal: English literature of the 16th century. Belles-lettres is a more specific term for writings of a light, elegant, or excessively refined character: His talent is not for scholarship but for belles-lettres. Letters (rare today outside of certain fixed phrases) refers to literature as a domain of study or creation: a man of letters.

OTHER WORDS FROM literature

pre·lit·er·a·ture, noun

Words nearby literature

literate, literati, literatim, literation, literator, literature, literatus, lith, litharge, lithe, lithemia

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

MORE ABOUT LITERATURE

What is literature?

Literature is writing that uses artistic expression and form and is considered to have merit or be important.

As an artistic term, literature refers to written works, such as novels, short stories, biographies, memories, essays, and poetry. However, songs, movies, TV shows, video games, and paintings are typically not considered to be literature because the final output is not text.

At the same time, literature is usually thought to only include works of art. Informative works like newspapers, scientific journals, religious texts, press releases, and spreadsheets are generally not considered to be literature.

Yet in scientific study, especially anthropology or history, the word literature is used more broadly to describe everything that a specific society or group has ever written. For example, a researcher may be studying “Persian literature,” which would include even mundane, non-artistic pieces of writing that was created by a citizen of the Persian empire, such as lists of food supplies.

Why is literature important?

The first records of the word literature come from around 1375. It ultimately comes from the Latin litterātūra, meaning “grammar” or “writing.”

What writings are considered literature is often debated. Average readers and literary experts often disagree on what counts as literature. Literary experts also disagree among themselves what is and isn’t literature. Usually, literature is defined as being “of interest” or having importance, which is obviously a subjective quality. Who gets to decide if a piece of writing is important? In the past, the answer was “people who can read.” In your own life, the literature you have studied has most likely been selected by an English teacher or a literature department at a college.

In everyday life, the word literature is most likely to be used when speaking academically or scholastically. Libraries and stores that sell books are less likely to use this broad, unhelpful term and are more likely to categorize written works using more specific words, like poetry, romance, or young adult fiction.

Did you know … ?

The oldest author whose name we know was Enheduanna, a Sumerian princess and high priestess who wrote poetry dedicated to the gods over 4,000 years ago. Her literature is the oldest written work we know of.

What are real-life examples of literature?

People have many different opinions on what kinds of literature they like to read.

Who says great literature is dead? pic.twitter.com/m7yeKBkTxh

— Stephen King (@StephenKing) April 11, 2018

Reading my twitter feed is still reading so that counts as literature right?

— karlie jones (@__karlie__) March 11, 2013

Quiz yourself!

Which of the following is NOT considered to be literature?

A. a nature poem

B. a science fiction novel

C. a murder mystery television show

D. a president’s autobiography

Words related to literature

article, biography, brochure, composition, drama, essay, history, information, leaflet, lore, novel, pamphlet, poetry, prose, research, story, abstract, belles-lettres, books, classics

How to use literature in a sentence

-

If you want to understand the flamboyant family of objects that make up our solar system—from puny, sputtering comets to tremendous, ringed planets—you could start by immersing yourself in the technical terms that fill the scientific literature.

-

Poway Unified anticipates bringing forward two new courses – ethnic studies and ethnic literature – to the school board for review, said Christine Paik, a spokeswoman for the district.

-

The book she completed after that trip, Coming of Age in Samoa, published in 1928, would be hailed as a classic in the literature on sexuality and adolescence.

-

He also told Chemistry World he envisages the robots eventually being able to analyze the scientific literature to better guide their experiments.

-

Research also suggests that reading literature may help increase empathy and understanding of others’ experiences, potentially spurring better real-world behavior.

-

The research literature, too, asks these questions, and not without reason.

-

She wanted to know what happened over five years, or even 10, but the scientific literature had little to offer.

-

The religion shaped all facets of life: art, medicine, literature, and even dynastic politics.

-

Speaking of the literature you love, the Bloomsbury writers crop up in your collection repeatedly.

-

Literature in the 14th century, Strohm points out, was an intimate, interactive affair.

-

All along the highways and by-paths of our literature we encounter much that pertains to this «queen of plants.»

-

There cannot be many persons in the world who keep up with the whole range of musical literature as he does.

-

In early English literature there was at one time a tendency to ascribe to Solomon various proverbs not in the Bible.

-

He was deeply versed in Saxon literature and published a work on the antiquity of the English church.

-

Such unromantic literature as Acts of Parliament had not, it may be supposed, up to this, formed part of my mental pabulum.

British Dictionary definitions for literature

literature

/ (ˈlɪtərɪtʃə, ˈlɪtrɪ-) /

noun

written material such as poetry, novels, essays, etc, esp works of imagination characterized by excellence of style and expression and by themes of general or enduring interest

the body of written work of a particular culture or peopleScandinavian literature

written or printed matter of a particular type or on a particular subjectscientific literature; the literature of the violin

printed material giving a particular type of informationsales literature

the art or profession of a writer

obsolete learning

Word Origin for literature

C14: from Latin litterātūra writing; see letter

Collins English Dictionary — Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition

© William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins

Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Literature (from the Latin Littera meaning ‘letters’ and referring to an acquaintance with the written word) is the written work of a specific culture, sub-culture, religion, philosophy or the study of such written work which may appear in poetry or in prose. Literature, in the west, originated in the southern Mesopotamia region of Sumer (c. 3200) in the city of Uruk and flourished in Egypt, later in Greece (the written word having been imported there from the Phoenicians) and from there, to Rome. Writing seems to have originated independently in China from divination practices and also independently in Mesoamerica and elsewhere.

The first author of literature in the world, known by name, was the high-priestess of Ur, Enheduanna (2285-2250 BCE) who wrote hymns in praise of the Sumerian goddess Inanna. Much of the early literature from Mesopotamia concerns the activities of the gods but, in time, humans came to be featured as the main characters in such poems as Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta and Lugalbanda and Mount Hurrum (c.2600-2000 BCE). For the purposes of study, Literature is divided into the categories of fiction or non-fiction today but these are often arbitrary decisions as ancient literature, as understood by those who wrote the tales down, as well as those who heard them spoken or sung pre-literacy, was not understood in the same way as it is in the modern-day.

The Truth in Literature