A biker performing a dirt jump that, according to some interpretations, is the result of free will.

Free will is the notional capacity or ability to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.[1]

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, sin, and other judgements which apply only to actions that are freely chosen. It is also connected with the concepts of advice, persuasion, deliberation, and prohibition. Traditionally, only actions that are freely willed are seen as deserving credit or blame. Whether free will exists, what it is and the implications of whether it exists or not are some of the longest running debates of philosophy and religion. Some conceive of free will as the ability to act beyond the limits of external influences or wishes.

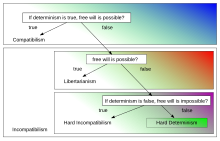

Some conceive free will to be the capacity to make choices undetermined by past events. Determinism suggests that only one course of events is possible, which is inconsistent with a libertarian model of free will.[2] Ancient Greek philosophy identified this issue,[3] which remains a major focus of philosophical debate. The view that conceives free will as incompatible with determinism is called incompatibilism and encompasses both metaphysical libertarianism (the claim that determinism is false and thus free will is at least possible) and hard determinism (the claim that determinism is true and thus free will is not possible). Incompatibilism also encompasses hard incompatibilism, which holds not only determinism but also indeterminism to be incompatible with free will and thus free will to be impossible whatever the case may be regarding determinism.

In contrast, compatibilists hold that free will is compatible with determinism. Some compatibilists even hold that determinism is necessary for free will, arguing that choice involves preference for one course of action over another, requiring a sense of how choices will turn out.[4][5] Compatibilists thus consider the debate between libertarians and hard determinists over free will vs. determinism a false dilemma.[6] Different compatibilists offer very different definitions of what «free will» means and consequently find different types of constraints to be relevant to the issue. Classical compatibilists considered free will nothing more than freedom of action, considering one free of will simply if, had one counterfactually wanted to do otherwise, one could have done otherwise without physical impediment. Contemporary compatibilists instead identify free will as a psychological capacity, such as to direct one’s behavior in a way responsive to reason, and there are still further different conceptions of free will, each with their own concerns, sharing only the common feature of not finding the possibility of determinism a threat to the possibility of free will.[7]

History of free will[edit]

The problem of free will has been identified in ancient Greek philosophical literature. The notion of compatibilist free will has been attributed to both Aristotle (fourth century BCE) and Epictetus (1st century CE); «it was the fact that nothing hindered us from doing or choosing something that made us have control over them».[3][8] According to Susanne Bobzien, the notion of incompatibilist free will is perhaps first identified in the works of Alexander of Aphrodisias (third century CE); «what makes us have control over things is the fact that we are causally undetermined in our decision and thus can freely decide between doing/choosing or not doing/choosing them».

The term «free will» (liberum arbitrium) was introduced by Christian philosophy (4th century CE). It has traditionally meant (until the Enlightenment proposed its own meanings) lack of necessity in human will,[9] so that «the will is free» meant «the will does not have to be such as it is». This requirement was universally embraced by both incompatibilists and compatibilists.[10]

Western philosophy[edit]

The underlying questions are whether we have control over our actions, and if so, what sort of control, and to what extent. These questions predate the early Greek stoics (for example, Chrysippus), and some modern philosophers lament the lack of progress over all these centuries.[11][12]

On one hand, humans have a strong sense of freedom, which leads them to believe that they have free will.[13][14] On the other hand, an intuitive feeling of free will could be mistaken.[15][16]

It is difficult to reconcile the intuitive evidence that conscious decisions are causally effective with the view that the physical world can be explained entirely by physical law.[17] The conflict between intuitively felt freedom and natural law arises when either causal closure or physical determinism (nomological determinism) is asserted. With causal closure, no physical event has a cause outside the physical domain, and with physical determinism, the future is determined entirely by preceding events (cause and effect).

The puzzle of reconciling ‘free will’ with a deterministic universe is known as the problem of free will or sometimes referred to as the dilemma of determinism.[18] This dilemma leads to a moral dilemma as well: the question of how to assign responsibility for actions if they are caused entirely by past events.[19][20]

Compatibilists maintain that mental reality is not of itself causally effective.[21][22] Classical compatibilists have addressed the dilemma of free will by arguing that free will holds as long as humans are not externally constrained or coerced.[23] Modern compatibilists make a distinction between freedom of will and freedom of action, that is, separating freedom of choice from the freedom to enact it.[24] Given that humans all experience a sense of free will, some modern compatibilists think it is necessary to accommodate this intuition.[25][26] Compatibilists often associate freedom of will with the ability to make rational decisions.

A different approach to the dilemma is that of incompatibilists, namely, that if the world is deterministic, then our feeling that we are free to choose an action is simply an illusion. Metaphysical libertarianism is the form of incompatibilism which posits that determinism is false and free will is possible (at least some people have free will).[27] This view is associated with non-materialist constructions,[15] including both traditional dualism, as well as models supporting more minimal criteria; such as the ability to consciously veto an action or competing desire.[28][29] Yet even with physical indeterminism, arguments have been made against libertarianism in that it is difficult to assign Origination (responsibility for «free» indeterministic choices).

Free will here is predominantly treated with respect to physical determinism in the strict sense of nomological determinism, although other forms of determinism are also relevant to free will.[30] For example, logical and theological determinism challenge metaphysical libertarianism with ideas of destiny and fate, and biological, cultural and psychological determinism feed the development of compatibilist models. Separate classes of compatibilism and incompatibilism may even be formed to represent these.[31]

Below are the classic arguments bearing upon the dilemma and its underpinnings.

Incompatibilism[edit]

Incompatibilism is the position that free will and determinism are logically incompatible, and that the major question regarding whether or not people have free will is thus whether or not their actions are determined. «Hard determinists», such as d’Holbach, are those incompatibilists who accept determinism and reject free will. In contrast, «metaphysical libertarians», such as Thomas Reid, Peter van Inwagen, and Robert Kane, are those incompatibilists who accept free will and deny determinism, holding the view that some form of indeterminism is true.[32] Another view is that of hard incompatibilists, which state that free will is incompatible with both determinism and indeterminism.[33]

Traditional arguments for incompatibilism are based on an «intuition pump»: if a person is like other mechanical things that are determined in their behavior such as a wind-up toy, a billiard ball, a puppet, or a robot, then people must not have free will.[32][34] This argument has been rejected by compatibilists such as Daniel Dennett on the grounds that, even if humans have something in common with these things, it remains possible and plausible that we are different from such objects in important ways.[35]

Another argument for incompatibilism is that of the «causal chain». Incompatibilism is key to the idealist theory of free will. Most incompatibilists reject the idea that freedom of action consists simply in «voluntary» behavior. They insist, rather, that free will means that someone must be the «ultimate» or «originating» cause of his actions. They must be causa sui, in the traditional phrase. Being responsible for one’s choices is the first cause of those choices, where first cause means that there is no antecedent cause of that cause. The argument, then, is that if a person has free will, then they are the ultimate cause of their actions. If determinism is true, then all of a person’s choices are caused by events and facts outside their control. So, if everything someone does is caused by events and facts outside their control, then they cannot be the ultimate cause of their actions. Therefore, they cannot have free will.[36][37][38] This argument has also been challenged by various compatibilist philosophers.[39][40]

A third argument for incompatibilism was formulated by Carl Ginet in the 1960s and has received much attention in the modern literature. The simplified argument runs along these lines: if determinism is true, then we have no control over the events of the past that determined our present state and no control over the laws of nature. Since we can have no control over these matters, we also can have no control over the consequences of them. Since our present choices and acts, under determinism, are the necessary consequences of the past and the laws of nature, then we have no control over them and, hence, no free will. This is called the consequence argument.[41][42] Peter van Inwagen remarks that C.D. Broad had a version of the consequence argument as early as the 1930s.[43]

The difficulty of this argument for some compatibilists lies in the fact that it entails the impossibility that one could have chosen other than one has. For example, if Jane is a compatibilist and she has just sat down on the sofa, then she is committed to the claim that she could have remained standing, if she had so desired. But it follows from the consequence argument that, if Jane had remained standing, she would have either generated a contradiction, violated the laws of nature or changed the past. Hence, compatibilists are committed to the existence of «incredible abilities», according to Ginet and van Inwagen. One response to this argument is that it equivocates on the notions of abilities and necessities, or that the free will evoked to make any given choice is really an illusion and the choice had been made all along, oblivious to its «decider».[42] David Lewis suggests that compatibilists are only committed to the ability to do something otherwise if different circumstances had actually obtained in the past.[44]

Using T, F for «true» and «false» and ? for undecided, there are exactly nine positions regarding determinism/free will that consist of any two of these three possibilities:[45]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Determinism D | T | F | T | F | T | F | ? | ? | ? |

| Free will FW | F | T | T | F | ? | ? | F | T | ? |

Incompatibilism may occupy any of the nine positions except (5), (8) or (3), which last corresponds to soft determinism. Position (1) is hard determinism, and position (2) is libertarianism. The position (1) of hard determinism adds to the table the contention that D implies FW is untrue, and the position (2) of libertarianism adds the contention that FW implies D is untrue. Position (9) may be called hard incompatibilism if one interprets ? as meaning both concepts are of dubious value. Compatibilism itself may occupy any of the nine positions, that is, there is no logical contradiction between determinism and free will, and either or both may be true or false in principle. However, the most common meaning attached to compatibilism is that some form of determinism is true and yet we have some form of free will, position (3).[46]

Alex Rosenberg makes an extrapolation of physical determinism as inferred on the macroscopic scale by the behaviour of a set of dominoes to neural activity in the brain where; «If the brain is nothing but a complex physical object whose states are as much governed by physical laws as any other physical object, then what goes on in our heads is as fixed and determined by prior events as what goes on when one domino topples another in a long row of them.»[47] Physical determinism is currently disputed by prominent interpretations of quantum mechanics, and while not necessarily representative of intrinsic indeterminism in nature, fundamental limits of precision in measurement are inherent in the uncertainty principle.[48] The relevance of such prospective indeterminate activity to free will is, however, contested,[49] even when chaos theory is introduced to magnify the effects of such microscopic events.[29][50]

Below these positions are examined in more detail.[45]

Hard determinism[edit]

A simplified taxonomy of philosophical positions regarding free will and determinism

Determinism can be divided into causal, logical and theological determinism.[51] Corresponding to each of these different meanings, there arises a different problem for free will.[52] Hard determinism is the claim that determinism is true, and that it is incompatible with free will, so free will does not exist. Although hard determinism generally refers to nomological determinism (see causal determinism below), it can include all forms of determinism that necessitate the future in its entirety.[53] Relevant forms of determinism include:

- Causal determinism

- The idea that everything is caused by prior conditions, making it impossible for anything else to happen.[54] In its most common form, nomological (or scientific) determinism, future events are necessitated by past and present events combined with the laws of nature. Such determinism is sometimes illustrated by the thought experiment of Laplace’s demon. Imagine an entity that knows all facts about the past and the present, and knows all natural laws that govern the universe. If the laws of nature were determinate, then such an entity would be able to use this knowledge to foresee the future, down to the smallest detail.[55][56]

- Logical determinism

- The notion that all propositions, whether about the past, present or future, are either true or false. The problem of free will, in this context, is the problem of how choices can be free, given that what one does in the future is already determined as true or false in the present.[52]

- Theological determinism

- The idea that the future is already determined, either by a creator deity decreeing or knowing its outcome in advance.[57][58] The problem of free will, in this context, is the problem of how our actions can be free if there is a being who has determined them for us in advance, or if they are already set in time.

Other forms of determinism are more relevant to compatibilism, such as biological determinism, the idea that all behaviors, beliefs, and desires are fixed by our genetic endowment and our biochemical makeup, the latter of which is affected by both genes and environment, cultural determinism and psychological determinism.[52] Combinations and syntheses of determinist theses, such as bio-environmental determinism, are even more common.

Suggestions have been made that hard determinism need not maintain strict determinism, where something near to, like that informally known as adequate determinism, is perhaps more relevant.[30] Despite this, hard determinism has grown less popular in present times, given scientific suggestions that determinism is false – yet the intention of their position is sustained by hard incompatibilism.[27]

Metaphysical libertarianism[edit]

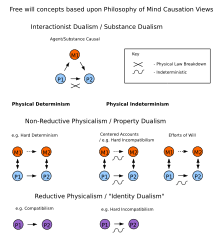

Various definitions of free will that have been proposed for Metaphysical Libertarianism (agent/substance causal,[59] centered accounts,[60] and efforts of will theory[29]), along with examples of other common free will positions (Compatibilism,[17] Hard Determinism,[61] and Hard Incompatibilism[33]). Red circles represent mental states; blue circles represent physical states; arrows describe causal interaction.

Metaphysical libertarianism is one philosophical view point under that of incompatibilism. Libertarianism holds onto a concept of free will that requires that the agent be able to take more than one possible course of action under a given set of circumstances.[62]

Accounts of libertarianism subdivide into non-physical theories and physical or naturalistic theories. Non-physical theories hold that the events in the brain that lead to the performance of actions do not have an entirely physical explanation, which requires that the world is not closed under physics. This includes interactionist dualism, which claims that some non-physical mind, will, or soul overrides physical causality. Physical determinism implies there is only one possible future and is therefore not compatible with libertarian free will. As consequent of incompatibilism, metaphysical libertarian explanations that do not involve dispensing with physicalism require physical indeterminism, such as probabilistic subatomic particle behavior – theory unknown to many of the early writers on free will. Incompatibilist theories can be categorised based on the type of indeterminism they require; uncaused events, non-deterministically caused events, and agent/substance-caused events.[59]

Non-causal theories[edit]

Non-causal accounts of incompatibilist free will do not require a free action to be caused by either an agent or a physical event. They either rely upon a world that is not causally closed, or physical indeterminism. Non-causal accounts often claim that each intentional action requires a choice or volition – a willing, trying, or endeavoring on behalf of the agent (such as the cognitive component of lifting one’s arm).[63][64] Such intentional actions are interpreted as free actions. It has been suggested, however, that such acting cannot be said to exercise control over anything in particular. According to non-causal accounts, the causation by the agent cannot be analysed in terms of causation by mental states or events, including desire, belief, intention of something in particular, but rather is considered a matter of spontaneity and creativity. The exercise of intent in such intentional actions is not that which determines their freedom – intentional actions are rather self-generating. The «actish feel» of some intentional actions do not «constitute that event’s activeness, or the agent’s exercise of active control», rather they «might be brought about by direct stimulation of someone’s brain, in the absence of any relevant desire or intention on the part of that person».[59] Another question raised by such non-causal theory, is how an agent acts upon reason, if the said intentional actions are spontaneous.

Some non-causal explanations involve invoking panpsychism, the theory that a quality of mind is associated with all particles, and pervades the entire universe, in both animate and inanimate entities.

Event-causal theories[edit]

Event-causal accounts of incompatibilist free will typically rely upon physicalist models of mind (like those of the compatibilist), yet they presuppose physical indeterminism, in which certain indeterministic events are said to be caused by the agent. A number of event-causal accounts of free will have been created, referenced here as deliberative indeterminism, centred accounts, and efforts of will theory.[59] The first two accounts do not require free will to be a fundamental constituent of the universe. Ordinary randomness is appealed to as supplying the «elbow room» that libertarians believe necessary. A first common objection to event-causal accounts is that the indeterminism could be destructive and could therefore diminish control by the agent rather than provide it (related to the problem of origination). A second common objection to these models is that it is questionable whether such indeterminism could add any value to deliberation over that which is already present in a deterministic world.

Deliberative indeterminism asserts that the indeterminism is confined to an earlier stage in the decision process.[65][66] This is intended to provide an indeterminate set of possibilities to choose from, while not risking the introduction of luck (random decision making). The selection process is deterministic, although it may be based on earlier preferences established by the same process. Deliberative indeterminism has been referenced by Daniel Dennett[67] and John Martin Fischer.[68] An obvious objection to such a view is that an agent cannot be assigned ownership over their decisions (or preferences used to make those decisions) to any greater degree than that of a compatibilist model.

Centred accounts propose that for any given decision between two possibilities, the strength of reason will be considered for each option, yet there is still a probability the weaker candidate will be chosen.[60][69][70][71][72][73][74] An obvious objection to such a view is that decisions are explicitly left up to chance, and origination or responsibility cannot be assigned for any given decision.

Efforts of will theory is related to the role of will power in decision making. It suggests that the indeterminacy of agent volition processes could map to the indeterminacy of certain physical events – and the outcomes of these events could therefore be considered caused by the agent. Models of volition have been constructed in which it is seen as a particular kind of complex, high-level process with an element of physical indeterminism. An example of this approach is that of Robert Kane, where he hypothesizes that «in each case, the indeterminism is functioning as a hindrance or obstacle to her realizing one of her purposes – a hindrance or obstacle in the form of resistance within her will which must be overcome by effort.»[29] According to Robert Kane such «ultimate responsibility» is a required condition for free will.[75] An important factor in such a theory is that the agent cannot be reduced to physical neuronal events, but rather mental processes are said to provide an equally valid account of the determination of outcome as their physical processes (see non-reductive physicalism).

Although at the time quantum mechanics (and physical indeterminism) was only in the initial stages of acceptance, in his book Miracles: A preliminary study C.S. Lewis stated the logical possibility that if the physical world were proved indeterministic this would provide an entry point to describe an action of a non-physical entity on physical reality.[76] Indeterministic physical models (particularly those involving quantum indeterminacy) introduce random occurrences at an atomic or subatomic level. These events might affect brain activity, and could seemingly allow incompatibilist free will if the apparent indeterminacy of some mental processes (for instance, subjective perceptions of control in conscious volition) map to the underlying indeterminacy of the physical construct. This relationship, however, requires a causative role over probabilities that is questionable,[77] and it is far from established that brain activity responsible for human action can be affected by such events. Secondarily, these incompatibilist models are dependent upon the relationship between action and conscious volition, as studied in the neuroscience of free will. It is evident that observation may disturb the outcome of the observation itself, rendering limited our ability to identify causality.[48] Niels Bohr, one of the main architects of quantum theory, suggested, however, that no connection could be made between indeterminism of nature and freedom of will.[49]

Agent/substance-causal theories[edit]

Agent/substance-causal accounts of incompatibilist free will rely upon substance dualism in their description of mind. The agent is assumed power to intervene in the physical world.[78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85]

Agent (substance)-causal accounts have been suggested by both George Berkeley[86] and Thomas Reid.[87] It is required that what the agent causes is not causally determined by prior events. It is also required that the agent’s causing of that event is not causally determined by prior events. A number of problems have been identified with this view. Firstly, it is difficult to establish the reason for any given choice by the agent, which suggests they may be random or determined by luck (without an underlying basis for the free will decision). Secondly, it has been questioned whether physical events can be caused by an external substance or mind – a common problem associated with interactionalist dualism.

Hard incompatibilism[edit]

Hard incompatibilism is the idea that free will cannot exist, whether the world is deterministic or not. Derk Pereboom has defended hard incompatibilism, identifying a variety of positions where free will is irrelevant to indeterminism/determinism, among them the following:

-

- Determinism (D) is true, D does not imply we lack free will (F), but in fact we do lack F.

- D is true, D does not imply we lack F, but in fact we don’t know if we have F.

- D is true, and we do have F.

- D is true, we have F, and F implies D.

- D is unproven, but we have F.

- D isn’t true, we do have F, and would have F even if D were true.

- D isn’t true, we don’t have F, but F is compatible with D.

-

-

-

-

- Derk Pereboom, Living without Free Will,[33] p. xvi.

-

-

-

Pereboom calls positions 3 and 4 soft determinism, position 1 a form of hard determinism, position 6 a form of classical libertarianism, and any position that includes having F as compatibilism.

John Locke denied that the phrase «free will» made any sense (compare with theological noncognitivism, a similar stance on the existence of God). He also took the view that the truth of determinism was irrelevant. He believed that the defining feature of voluntary behavior was that individuals have the ability to postpone a decision long enough to reflect or deliberate upon the consequences of a choice: «…the will in truth, signifies nothing but a power, or ability, to prefer or choose».[88]

The contemporary philosopher Galen Strawson agrees with Locke that the truth or falsity of determinism is irrelevant to the

problem.[89] He argues that the notion of free will leads to an infinite regress and is therefore senseless.

According to Strawson, if one is responsible for what one does in a given situation, then one must be responsible for the way one is in certain mental respects. But it is impossible for one to be responsible for the way one is in any respect. This is because to be responsible in some situation S, one must have been responsible for the way one was at S−1. To be responsible for the way one was at S−1, one must have been responsible for the way one was at S−2, and so on. At some point in the chain, there must have been an act of origination of a new causal chain. But this is impossible. Man cannot create himself or his mental states ex nihilo. This argument entails that free will itself is absurd, but not that it is incompatible with determinism. Strawson calls his own view «pessimism» but it can be classified as hard incompatibilism.[89]

Causal determinism[edit]

Causal determinism is the concept that events within a given paradigm are bound by causality in such a way that any state (of an object or event) is completely determined by prior states. Causal determinism proposes that there is an unbroken chain of prior occurrences stretching back to the origin of the universe. Causal determinists believe that there is nothing uncaused or self-caused. The most common form of causal determinism is nomological determinism (or scientific determinism), the notion that the past and the present dictate the future entirely and necessarily by rigid natural laws, that every occurrence results inevitably from prior events. Quantum mechanics poses a serious challenge to this view.

Fundamental debate continues over whether the physical universe is likely to be deterministic. Although the scientific method cannot be used to rule out indeterminism with respect to violations of causal closure, it can be used to identify indeterminism in natural law. Interpretations of quantum mechanics at present are both deterministic and indeterministic, and are being constrained by ongoing experimentation.[90]

Destiny and fate[edit]

Destiny or fate is a predetermined course of events. It may be conceived as a predetermined future, whether in general or of an individual. It is a concept based on the belief that there is a fixed natural order to the cosmos.

Although often used interchangeably, the words «fate» and «destiny» have distinct connotations.

Fate generally implies there is a set course that cannot be deviated from, and over which one has no control. Fate is related to determinism, but makes no specific claim of physical determinism. Even with physical indeterminism an event could still be fated externally (see for instance theological determinism). Destiny likewise is related to determinism, but makes no specific claim of physical determinism. Even with physical indeterminism an event could still be destined to occur.

Destiny implies there is a set course that cannot be deviated from, but does not of itself make any claim with respect to the setting of that course (i.e., it does not necessarily conflict with incompatibilist free will). Free will if existent could be the mechanism by which that destined outcome is chosen (determined to represent destiny).[91]

Logical determinism[edit]

Discussion regarding destiny does not necessitate the existence of supernatural powers. Logical determinism or determinateness is the notion that all propositions, whether about the past, present, or future, are either true or false. This creates a unique problem for free will given that propositions about the future already have a truth value in the present (that is it is already determined as either true or false), and is referred to as the problem of future contingents.

Omniscience[edit]

Omniscience is the capacity to know everything that there is to know (included in which are all future events), and is a property often attributed to a creator deity. Omniscience implies the existence of destiny. Some authors have claimed that free will cannot coexist with omniscience. One argument asserts that an omniscient creator not only implies destiny but a form of high level predeterminism such as hard theological determinism or predestination – that they have independently fixed all events and outcomes in the universe in advance. In such a case, even if an individual could have influence over their lower level physical system, their choices in regard to this cannot be their own, as is the case with libertarian free will. Omniscience features as an incompatible-properties argument for the existence of God, known as the argument from free will, and is closely related to other such arguments, for example the incompatibility of omnipotence with a good creator deity (i.e. if a deity knew what they were going to choose, then they are responsible for letting them choose it).

Predeterminism[edit]

Predeterminism is the idea that all events are determined in advance.[92][93] Predeterminism is the philosophy that all events of history, past, present and future, have been decided or are known (by God, fate, or some other force), including human actions. Predeterminism is frequently taken to mean that human actions cannot interfere with (or have no bearing on) the outcomes of a pre-determined course of events, and that one’s destiny was established externally (for example, exclusively by a creator deity). The concept of predeterminism is often argued by invoking causal determinism, implying that there is an unbroken chain of prior occurrences stretching back to the origin of the universe. In the case of predeterminism, this chain of events has been pre-established, and human actions cannot interfere with the outcomes of this pre-established chain. Predeterminism can be used to mean such pre-established causal determinism, in which case it is categorised as a specific type of determinism.[92][94] It can also be used interchangeably with causal determinism – in the context of its capacity to determine future events.[92][95] Despite this, predeterminism is often considered as independent of causal determinism.[96][97] The term predeterminism is also frequently used in the context of biology and heredity, in which case it represents a form of biological determinism.[98]

The term predeterminism suggests not just a determining of all events, but the prior and deliberately conscious determining of all events (therefore done, presumably, by a conscious being). While determinism usually refers to a naturalistically explainable causality of events, predeterminism seems by definition to suggest a person or a «someone» who is controlling or planning the causality of events before they occur and who then perhaps resides beyond the natural, causal universe. Predestination asserts that a supremely powerful being has indeed fixed all events and outcomes in the universe in advance, and is a famous doctrine of the Calvinists in Christian theology. Predestination is often considered a form of hard theological determinism.

Predeterminism has therefore been compared to fatalism.[99] Fatalism is the idea that everything is fated to happen, so that humans have no control over their future.

Theological determinism[edit]

Theological determinism is a form of determinism stating that all events that happen are pre-ordained, or predestined to happen, by a monotheistic deity, or that they are destined to occur given its omniscience. Two forms of theological determinism exist, here referenced as strong and weak theological determinism.[100]

- The first one, strong theological determinism, is based on the concept of a creator deity dictating all events in history: «everything that happens has been predestined to happen by an omniscient, omnipotent divinity.»[101]

- The second form, weak theological determinism, is based on the concept of divine foreknowledge – «because God’s omniscience is perfect, what God knows about the future will inevitably happen, which means, consequently, that the future is already fixed.»[102]

There exist slight variations on the above categorisation. Some claim that theological determinism requires predestination of all events and outcomes by the divinity (that is, they do not classify the weaker version as ‘theological determinism’ unless libertarian free will is assumed to be denied as a consequence), or that the weaker version does not constitute ‘theological determinism’ at all.[53] Theological determinism can also be seen as a form of causal determinism, in which the antecedent conditions are the nature and will of God.[54] With respect to free will and the classification of theological compatibilism/incompatibilism below, «theological determinism is the thesis that God exists and has infallible knowledge of all true propositions including propositions about our future actions,» more minimal criteria designed to encapsulate all forms of theological determinism.[30]

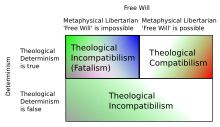

A simplified taxonomy of philosophical positions regarding free will and theological determinism[31]

There are various implications for metaphysical libertarian free will as consequent of theological determinism and its philosophical interpretation.

- Strong theological determinism is not compatible with metaphysical libertarian free will, and is a form of hard theological determinism (equivalent to theological fatalism below). It claims that free will does not exist, and God has absolute control over a person’s actions. Hard theological determinism is similar in implication to hard determinism, although it does not invalidate compatibilist free will.[31] Hard theological determinism is a form of theological incompatibilism (see figure, top left).

- Weak theological determinism is either compatible or incompatible with metaphysical libertarian free will depending upon one’s philosophical interpretation of omniscience – and as such is interpreted as either a form of hard theological determinism (known as theological fatalism), or as soft theological determinism (terminology used for clarity only). Soft theological determinism claims that humans have free will to choose their actions, holding that God, while knowing their actions before they happen, does not affect the outcome. God’s providence is «compatible» with voluntary choice. Soft theological determinism is known as theological compatibilism (see figure, top right). A rejection of theological determinism (or divine foreknowledge) is classified as theological incompatibilism also (see figure, bottom), and is relevant to a more general discussion of free will.[31]

The basic argument for theological fatalism in the case of weak theological determinism is as follows:

- Assume divine foreknowledge or omniscience

- Infallible foreknowledge implies destiny (it is known for certain what one will do)

- Destiny eliminates alternate possibility (one cannot do otherwise)

- Assert incompatibility with metaphysical libertarian free will

This argument is very often accepted as a basis for theological incompatibilism: denying either libertarian free will or divine foreknowledge (omniscience) and therefore theological determinism. On the other hand, theological compatibilism must attempt to find problems with it. The formal version of the argument rests on a number of premises, many of which have received some degree of contention. Theological compatibilist responses have included:

- Deny the truth value of future contingents, although this denies foreknowledge and therefore theological determinism.

- Assert differences in non-temporal knowledge (space-time independence), an approach taken for example by Boethius,[103] Thomas Aquinas,[104] and C.S. Lewis.[105]

- Deny the Principle of Alternate Possibilities: «If you cannot do otherwise when you do an act, you do not act freely.» For example, a human observer could in principle have a machine that could detect what will happen in the future, but the existence of this machine or their use of it has no influence on the outcomes of events.[106]

In the definition of compatibilism and incompatibilism, the literature often fails to distinguish between physical determinism and higher level forms of determinism (predeterminism, theological determinism, etc.) As such, hard determinism with respect to theological determinism (or «Hard Theological Determinism» above) might be classified as hard incompatibilism with respect to physical determinism (if no claim was made regarding the internal causality or determinism of the universe), or even compatibilism (if freedom from the constraint of determinism was not considered necessary for free will), if not hard determinism itself. By the same principle, metaphysical libertarianism (a form of incompatibilism with respect to physical determinism) might be classified as compatibilism with respect to theological determinism (if it was assumed such free will events were pre-ordained and therefore were destined to occur, but of which whose outcomes were not «predestined» or determined by God). If hard theological determinism is accepted (if it was assumed instead that such outcomes were predestined by God), then metaphysical libertarianism is not, however, possible, and would require reclassification (as hard incompatibilism for example, given that the universe is still assumed to be indeterministic – although the classification of hard determinism is technically valid also).[53]

Mind–body problem[edit]

The idea of free will is one aspect of the mind–body problem, that is, consideration of the relation between mind (for example, consciousness, memory, and judgment) and body (for example, the human brain and nervous system). Philosophical models of mind are divided into physical and non-physical expositions.

Cartesian dualism holds that the mind is a nonphysical substance, the seat of consciousness and intelligence, and is not identical with physical states of the brain or body. It is suggested that although the two worlds do interact, each retains some measure of autonomy. Under cartesian dualism external mind is responsible for bodily action, although unconscious brain activity is often caused by external events (for example, the instantaneous reaction to being burned).[107] Cartesian dualism implies that the physical world is not deterministic – and in which external mind controls (at least some) physical events, providing an interpretation of incompatibilist free will. Stemming from Cartesian dualism, a formulation sometimes called interactionalist dualism suggests a two-way interaction, that some physical events cause some mental acts and some mental acts cause some physical events. One modern vision of the possible separation of mind and body is the «three-world» formulation of Popper.[108] Cartesian dualism and Popper’s three worlds are two forms of what is called epistemological pluralism, that is the notion that different epistemological methodologies are necessary to attain a full description of the world. Other forms of epistemological pluralist dualism include psychophysical parallelism and epiphenomenalism. Epistemological pluralism is one view in which the mind-body problem is not reducible to the concepts of the natural sciences.

A contrasting approach is called physicalism. Physicalism is a philosophical theory holding that everything that exists is no more extensive than its physical properties; that is, that there are no non-physical substances (for example physically independent minds). Physicalism can be reductive or non-reductive. Reductive physicalism is grounded in the idea that everything in the world can actually be reduced analytically to its fundamental physical, or material, basis. Alternatively, non-reductive physicalism asserts that mental properties form a separate ontological class to physical properties: that mental states (such as qualia) are not ontologically reducible to physical states. Although one might suppose that mental states and neurological states are different in kind, that does not rule out the possibility that mental states are correlated with neurological states. In one such construction, anomalous monism, mental events supervene on physical events, describing the emergence of mental properties correlated with physical properties – implying causal reducibility. Non-reductive physicalism is therefore often categorised as property dualism rather than monism, yet other types of property dualism do not adhere to the causal reducibility of mental states (see epiphenomenalism).

Incompatibilism requires a distinction between the mental and the physical, being a commentary on the incompatibility of (determined) physical reality and one’s presumably distinct experience of will. Secondarily, metaphysical libertarian free will must assert influence on physical reality, and where mind is responsible for such influence (as opposed to ordinary system randomness), it must be distinct from body to accomplish this. Both substance and property dualism offer such a distinction, and those particular models thereof that are not causally inert with respect to the physical world provide a basis for illustrating incompatibilist free will (i.e. interactionalist dualism and non-reductive physicalism).

It has been noted that the laws of physics have yet to resolve the hard problem of consciousness:[109] «Solving the hard problem of consciousness involves determining how physiological processes such as ions flowing across the nerve membrane cause us to have experiences.»[110] According to some, «Intricately related to the hard problem of consciousness, the hard problem of free will represents the core problem of conscious free will: Does conscious volition impact the material world?»[15] Others however argue that «consciousness plays a far smaller role in human life than Western culture has tended to believe.»[111]

Compatibilism[edit]

Compatibilists maintain that determinism is compatible with free will. They believe freedom can be present or absent in a situation for reasons that have nothing to do with metaphysics. For instance, courts of law make judgments about whether individuals are acting under their own free will under certain circumstances without bringing in metaphysics. Similarly, political liberty is a non-metaphysical concept.[citation needed] Likewise, some compatibilists define free will as freedom to act according to one’s determined motives without hindrance from other individuals. So for example Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics,[112] and the Stoic Chrysippus.[113]

In contrast, the incompatibilist positions are concerned with a sort of «metaphysically free will», which compatibilists claim has never been coherently defined. Compatibilists argue that determinism does not matter; though they disagree among themselves about what, in turn, does matter. To be a compatibilist, one need not endorse any particular conception of free will, but only deny that determinism is at odds with free will.[114]

Although there are various impediments to exercising one’s choices, free will does not imply freedom of action. Freedom of choice (freedom to select one’s will) is logically separate from freedom to implement that choice (freedom to enact one’s will), although not all writers observe this distinction.[24] Nonetheless, some philosophers have defined free will as the absence of various impediments. Some «modern compatibilists», such as Harry Frankfurt and Daniel Dennett, argue free will is simply freely choosing to do what constraints allow one to do. In other words, a coerced agent’s choices can still be free if such coercion coincides with the agent’s personal intentions and desires.[35][115]

Free will as lack of physical restraint[edit]

Most «classical compatibilists», such as Thomas Hobbes, claim that a person is acting on the person’s own will only when it is the desire of that person to do the act, and also possible for the person to be able to do otherwise, if the person had decided to. Hobbes sometimes attributes such compatibilist freedom to each individual and not to some abstract notion of will, asserting, for example, that «no liberty can be inferred to the will, desire, or inclination, but the liberty of the man; which consisteth in this, that he finds no stop, in doing what he has the will, desire, or inclination to doe [sic].»[116] In articulating this crucial proviso, David Hume writes, «this hypothetical liberty is universally allowed to belong to every one who is not a prisoner and in chains.»[117] Similarly, Voltaire, in his Dictionnaire philosophique, claimed that «Liberty then is only and can be only the power to do what one will.» He asked, «would you have everything at the pleasure of a million blind caprices?» For him, free will or liberty is «only the power of acting, what is this power? It is the effect of the constitution and present state of our organs.»

Free will as a psychological state[edit]

Compatibilism often regards the agent free as virtue of their reason. Some explanations of free will focus on the internal causality of the mind with respect to higher-order brain processing – the interaction between conscious and unconscious brain activity.[118] Likewise, some modern compatibilists in psychology have tried to revive traditionally accepted struggles of free will with the formation of character.[119] Compatibilist free will has also been attributed to our natural sense of agency, where one must believe they are an agent in order to function and develop a theory of mind.[120][121]

The notion of levels of decision is presented in a different manner by Frankfurt.[115] Frankfurt argues for a version of compatibilism called the «hierarchical mesh». The idea is that an individual can have conflicting desires at a first-order level and also have a desire about the various first-order desires (a second-order desire) to the effect that one of the desires prevails over the others. A person’s will is identified with their effective first-order desire, that is, the one they act on, and this will is free if it was the desire the person wanted to act upon, that is, the person’s second-order desire was effective. So, for example, there are «wanton addicts», «unwilling addicts» and «willing addicts». All three groups may have the conflicting first-order desires to want to take the drug they are addicted to and to not want to take it.

The first group, wanton addicts, have no second-order desire not to take the drug. The second group, «unwilling addicts», have a second-order desire not to take the drug, while the third group, «willing addicts», have a second-order desire to take it. According to Frankfurt, the members of the first group are devoid of will and therefore are no longer persons. The members of the second group freely desire not to take the drug, but their will is overcome by the addiction. Finally, the members of the third group willingly take the drug they are addicted to. Frankfurt’s theory can ramify to any number of levels. Critics of the theory point out that there is no certainty that conflicts will not arise even at the higher-order levels of desire and preference.[122] Others argue that Frankfurt offers no adequate explanation of how the various levels in the hierarchy mesh together.[123]

Free will as unpredictability[edit]

In Elbow Room, Dennett presents an argument for a compatibilist theory of free will, which he further elaborated in the book Freedom Evolves.[124] The basic reasoning is that, if one excludes God, an infinitely powerful demon, and other such possibilities, then because of chaos and epistemic limits on the precision of our knowledge of the current state of the world, the future is ill-defined for all finite beings. The only well-defined things are «expectations». The ability to do «otherwise» only makes sense when dealing with these expectations, and not with some unknown and unknowable future.

According to Dennett, because individuals have the ability to act differently from what anyone expects, free will can exist.[124] Incompatibilists claim the problem with this idea is that we may be mere «automata responding in predictable ways to stimuli in our environment». Therefore, all of our actions are controlled by forces outside ourselves, or by random chance.[125] More sophisticated analyses of compatibilist free will have been offered, as have other critiques.[114]

In the philosophy of decision theory, a fundamental question is: From the standpoint of statistical outcomes, to what extent do the choices of a conscious being have the ability to influence the future? Newcomb’s paradox and other philosophical problems pose questions about free will and predictable outcomes of choices.

The physical mind[edit]

Compatibilist models of free will often consider deterministic relationships as discoverable in the physical world (including the brain). Cognitive naturalism[126] is a physicalist approach to studying human cognition and consciousness in which the mind is simply part of nature, perhaps merely a feature of many very complex self-programming feedback systems (for example, neural networks and cognitive robots), and so must be studied by the methods of empirical science, such as the behavioral and cognitive sciences (i.e. neuroscience and cognitive psychology).[107][127] Cognitive naturalism stresses the role of neurological sciences. Overall brain health, substance dependence, depression, and various personality disorders clearly influence mental activity, and their impact upon volition is also important.[118] For example, an addict may experience a conscious desire to escape addiction, but be unable to do so. The «will» is disconnected from the freedom to act. This situation is related to an abnormal production and distribution of dopamine in the brain.[128] The neuroscience of free will places restrictions on both compatibilist and incompatibilist free will conceptions.

Compatibilist models adhere to models of mind in which mental activity (such as deliberation) can be reduced to physical activity without any change in physical outcome. Although compatibilism is generally aligned to (or is at least compatible with) physicalism, some compatibilist models describe the natural occurrences of deterministic deliberation in the brain in terms of the first person perspective of the conscious agent performing the deliberation.[15] Such an approach has been considered a form of identity dualism. A description of «how conscious experience might affect brains» has been provided in which «the experience of conscious free will is the first-person perspective of the neural correlates of choosing.»[15]

Recently,[when?] Claudio Costa developed a neocompatibilist theory based on the causal theory of action that is complementary to classical compatibilism. According to him, physical, psychological and rational restrictions can interfere at different levels of the causal chain that would naturally lead to action. Correspondingly, there can be physical restrictions to the body, psychological restrictions to the decision, and rational restrictions to the formation of reasons (desires plus beliefs) that should lead to what we would call a reasonable action. The last two are usually called «restrictions of free will». The restriction at the level of reasons is particularly important since it can be motivated by external reasons that are insufficiently conscious to the agent. One example was the collective suicide led by Jim Jones. The suicidal agents were not conscious that their free will have been manipulated by external, even if ungrounded, reasons.[129]

Non-naturalism[edit]

Alternatives to strictly naturalist physics, such as mind–body dualism positing a mind or soul existing apart from one’s body while perceiving, thinking, choosing freely, and as a result acting independently on the body, include both traditional religious metaphysics and less common newer compatibilist concepts.[130] Also consistent with both autonomy and Darwinism,[131] they allow for free personal agency based on practical reasons within the laws of physics.[132] While less popular among 21st-century philosophers, non-naturalist compatibilism is present in most if not almost all religions.[133]

Other views[edit]

Some philosophers’ views are difficult to categorize as either compatibilist or incompatibilist, hard determinist or libertarian. For example, Ted Honderich holds the view that «determinism is true, compatibilism and incompatibilism are both false» and the real problem lies elsewhere. Honderich maintains that determinism is true because quantum phenomena are not events or things that can be located in space and time, but are abstract entities. Further, even if they were micro-level events, they do not seem to have any relevance to how the world is at the macroscopic level. He maintains that incompatibilism is false because, even if indeterminism is true, incompatibilists have not provided, and cannot provide, an adequate account of origination. He rejects compatibilism because it, like incompatibilism, assumes a single, fundamental notion of freedom. There are really two notions of freedom: voluntary action and origination. Both notions are required to explain freedom of will and responsibility. Both determinism and indeterminism are threats to such freedom. To abandon these notions of freedom would be to abandon moral responsibility. On the one side, we have our intuitions; on the other, the scientific facts. The «new» problem is how to resolve this conflict.[134]

Free will as an illusion[edit]

Spinoza thought that there is no free will.

- «Experience teaches us no less clearly than reason, that men believe themselves free, simply because they are conscious of their actions, and unconscious of the causes whereby those actions are determined.» Baruch Spinoza, Ethics[135]

David Hume discussed the possibility that the entire debate about free will is nothing more than a merely «verbal» issue. He suggested that it might be accounted for by «a false sensation or seeming experience» (a velleity), which is associated with many of our actions when we perform them. On reflection, we realize that they were necessary and determined all along.[136]

Arthur Schopenhauer claimed that phenomena do not have freedom of the will, but the will as noumenon is not subordinate to the laws of necessity (causality) and is thus free.

According to Arthur Schopenhauer, the actions of humans, as phenomena, are subject to the principle of sufficient reason and thus liable to necessity. Thus, he argues, humans do not possess free will as conventionally understood. However, the will [urging, craving, striving, wanting, and desiring], as the noumenon underlying the phenomenal world, is in itself groundless: that is, not subject to time, space, and causality (the forms that governs the world of appearance). Thus, the will, in itself and outside of appearance, is free. Schopenhauer discussed the puzzle of free will and moral responsibility in The World as Will and Representation, Book 2, Sec. 23:

But the fact is overlooked that the individual, the person, is not will as thing-in-itself, but is phenomenon of the will, is as such determined, and has entered the form of the phenomenon, the principle of sufficient reason. Hence we get the strange fact that everyone considers himself to be a priori quite free, even in his individual actions, and imagines he can at any moment enter upon a different way of life… But a posteriori through experience, he finds to his astonishment that he is not free, but liable to necessity; that notwithstanding all his resolutions and reflections he does not change his conduct, and that from the beginning to the end of his life he must bear the same character that he himself condemns, and, as it were, must play to the end the part he has taken upon himself.[137]

Schopenhauer elaborated on the topic in Book IV of the same work and in even greater depth in his later essay On the Freedom of the Will. In this work, he stated, «You can do what you will, but in any given moment of your life you can will only one definite thing and absolutely nothing other than that one thing.»[138]

In his book Free Will, philosopher and neuroscientist Sam Harris argues that free will is an illusion, stating that «thoughts and intentions emerge from background causes of which we are unaware and over which we exert no conscious control.»[139]

Free will as «moral imagination»[edit]

Rudolf Steiner, who collaborated in a complete edition of Arthur Schopenhauer’s work,[140] wrote The Philosophy of Freedom, which focuses on the problem of free will. Steiner (1861–1925) initially divides this into the two aspects of freedom: freedom of thought and freedom of action. The controllable and uncontrollable aspects of decision making thereby are made logically separable, as pointed out in the introduction. This separation of will from action has a very long history, going back at least as far as Stoicism and the teachings of Chrysippus (279–206 BCE), who separated external antecedent causes from the internal disposition receiving this cause.[141]

Steiner then argues that inner freedom is achieved when we integrate our sensory impressions, which reflect the outer appearance of the world, with our thoughts, which lend coherence to these impressions and thereby disclose to us an understandable world. Acknowledging the many influences on our choices, he nevertheless points out that they do not preclude freedom unless we fail to recognise them. Steiner argues that outer freedom is attained by permeating our deeds with moral imagination. «Moral» in this case refers to action that is willed, while «imagination» refers to the mental capacity to envision conditions that do not already hold. Both of these functions are necessarily conditions for freedom. Steiner aims to show that these two aspects of inner and outer freedom are integral to one another, and that true freedom is only achieved when they are united.[142]

Free will as a pragmatically useful concept[edit]

William James’ views were ambivalent. While he believed in free will on «ethical grounds», he did not believe that there was evidence for it on scientific grounds, nor did his own introspections support it.[143] Ultimately he believed that the problem of free will was a metaphysical issue and, therefore, could not be settled by science. Moreover, he did not accept incompatibilism as formulated below; he did not believe that the indeterminism of human actions was a prerequisite of moral responsibility. In his work Pragmatism, he wrote that «instinct and utility between them can safely be trusted to carry on the social business of punishment and praise» regardless of metaphysical theories.[144] He did believe that indeterminism is important as a «doctrine of relief» – it allows for the view that, although the world may be in many respects a bad place, it may, through individuals’ actions, become a better one. Determinism, he argued, undermines meliorism – the idea that progress is a real concept leading to improvement in the world.[144]

Free will and views of causality[edit]

In 1739, David Hume in his A Treatise of Human Nature approached free will via the notion of causality. It was his position that causality was a mental construct used to explain the repeated association of events, and that one must examine more closely the relation between things regularly succeeding one another (descriptions of regularity in nature) and things that result in other things (things that cause or necessitate other things).[145] According to Hume, ‘causation’ is on weak grounds: «Once we realise that ‘A must bring about B’ is tantamount merely to ‘Due to their constant conjunction, we are psychologically certain that B will follow A,’ then we are left with a very weak notion of necessity.»[146]

This empiricist view was often denied by trying to prove the so-called apriority of causal law (i.e. that it precedes all experience and is rooted in the construction of the perceivable world):

- Kant’s proof in Critique of Pure Reason (which referenced time and time ordering of causes and effects)[147]

- Schopenhauer’s proof from The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason (which referenced the so-called intellectuality of representations, that is, in other words, objects and qualia perceived with senses)[148]

In the 1780s Immanuel Kant suggested at a minimum our decision processes with moral implications lie outside the reach of everyday causality, and lie outside the rules governing material objects.[149] «There is a sharp difference between moral judgments and judgments of fact… Moral judgments… must be a priori judgments.»[150]

Freeman introduces what he calls «circular causality» to «allow for the contribution of self-organizing dynamics», the «formation of macroscopic population dynamics that shapes the patterns of activity of the contributing individuals», applicable to «interactions between neurons and neural masses… and between the behaving animal and its environment».[151] In this view, mind and neurological functions are tightly coupled in a situation where feedback between collective actions (mind) and individual subsystems (for example, neurons and their synapses) jointly decide upon the behaviour of both.

Free will according to Thomas Aquinas[edit]

Thirteenth century philosopher Thomas Aquinas viewed humans as pre-programmed (by virtue of being human) to seek certain goals, but able to choose between routes to achieve these goals (our Aristotelian telos). His view has been associated with both compatibilism and libertarianism.[152][153]

In facing choices, he argued that humans are governed by intellect, will, and passions. The will is «the primary mover of all the powers of the soul… and it is also the efficient cause of motion in the body.»[154] Choice falls into five stages: (i) intellectual consideration of whether an objective is desirable, (ii) intellectual consideration of means of attaining the objective, (iii) will arrives at an intent to pursue the objective, (iv) will and intellect jointly decide upon choice of means (v) will elects execution.[155] Free will enters as follows: Free will is an «appetitive power», that is, not a cognitive power of intellect (the term «appetite» from Aquinas’s definition «includes all forms of internal inclination»).[156] He states that judgment «concludes and terminates counsel. Now counsel is terminated, first, by the judgment of reason; secondly, by the acceptation of the appetite [that is, the free-will].»[157]

A compatibilist interpretation of Aquinas’s view is defended thus: «Free-will is the cause of its own movement, because by his free-will man moves himself to act. But it does not of necessity belong to liberty that what is free should be the first cause of itself, as neither for one thing to be cause of another need it be the first cause. God, therefore, is the first cause, Who moves causes both natural and voluntary. And just as by moving natural causes He does not prevent their acts being natural, so by moving voluntary causes He does not deprive their actions of being voluntary: but rather is He the cause of this very thing in them; for He operates in each thing according to its own nature.»[158][159]

Free will as a pseudo-problem[edit]

Historically, most of the philosophical effort invested in resolving the dilemma has taken the form of close examination of definitions and ambiguities in the concepts designated by «free», «freedom», «will», «choice» and so forth. Defining ‘free will’ often revolves around the meaning of phrases like «ability to do otherwise» or «alternative possibilities». This emphasis upon words has led some philosophers to claim the problem is merely verbal and thus a pseudo-problem.[160] In response, others point out the complexity of decision making and the importance of nuances in the terminology.[citation needed]

Eastern philosophy[edit]

Buddhist philosophy[edit]

Buddhism accepts both freedom and determinism (or something similar to it), but in spite of its focus towards the human agency, rejects the western concept of a total agent from external sources.[161] According to the Buddha, «There is free action, there is retribution, but I see no agent that passes out from one set of momentary elements into another one, except the [connection] of those elements.»[161] Buddhists believe in neither absolute free will, nor determinism. It preaches a middle doctrine, named pratītyasamutpāda in Sanskrit, often translated as «dependent origination», «dependent arising» or «conditioned genesis». It teaches that every volition is a conditioned action as a result of ignorance. In part, it states that free will is inherently conditioned and not «free» to begin with. It is also part of the theory of karma in Buddhism. The concept of karma in Buddhism is different from the notion of karma in Hinduism. In Buddhism, the idea of karma is much less deterministic. The Buddhist notion of karma is primarily focused on the cause and effect of moral actions in this life, while in Hinduism the concept of karma is more often connected with determining one’s destiny in future lives.

In Buddhism it is taught that the idea of absolute freedom of choice (that is that any human being could be completely free to make any choice) is unwise, because it denies the reality of one’s physical needs and circumstances. Equally incorrect is the idea that humans have no choice in life or that their lives are pre-determined. To deny freedom would be to deny the efforts of Buddhists to make moral progress (through our capacity to freely choose compassionate action). Pubbekatahetuvada, the belief that all happiness and suffering arise from previous actions, is considered a wrong view according to Buddhist doctrines. Because Buddhists also reject agenthood, the traditional compatibilist strategies are closed to them as well. Instead, the Buddhist philosophical strategy is to examine the metaphysics of causality. Ancient India had many heated arguments about the nature of causality with Jains, Nyayists, Samkhyists, Cārvākans, and Buddhists all taking slightly different lines. In many ways, the Buddhist position is closer to a theory of «conditionality» (idappaccayatā) than a theory of «causality», especially as it is expounded by Nagarjuna in the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā.[161]

Hindu philosophy[edit]

The six orthodox (astika) schools of thought in Hindu philosophy do not agree with each other entirely on the question of free will. For the Samkhya, for instance, matter is without any freedom, and soul lacks any ability to control the unfolding of matter. The only real freedom (kaivalya) consists in realizing the ultimate separateness of matter and self.[162] For the Yoga school, only Ishvara is truly free, and its freedom is also distinct from all feelings, thoughts, actions, or wills, and is thus not at all a freedom of will. The metaphysics of the Nyaya and Vaisheshika schools strongly suggest a belief in determinism, but do not seem to make explicit claims about determinism or free will.[163]

A quotation from Swami Vivekananda, a Vedantist, offers a good example of the worry about free will in the Hindu tradition.

Therefore we see at once that there cannot be any such thing as free-will; the very words are a contradiction, because will is what we know, and everything that we know is within our universe, and everything within our universe is moulded by conditions of time, space and causality. … To acquire freedom we have to get beyond the limitations of this universe; it cannot be found here.[164]

However, the preceding quote has often been misinterpreted as Vivekananda implying that everything is predetermined. What Vivekananda actually meant by lack of free will was that the will was not «free» because it was heavily influenced by the law of cause and effect – «The will is not free, it is a phenomenon bound by cause and effect, but there is something behind the will which is free.»[164] Vivekananda never said things were absolutely determined and placed emphasis on the power of conscious choice to alter one’s past karma: «It is the coward and the fool who says this is his fate. But it is the strong man who stands up and says I will make my own fate.»[164]

Scientific approaches[edit]

Science has contributed to the free will problem in at least three ways. First, physics has addressed the question of whether nature is deterministic, which is viewed as crucial by incompatibilists (compatibilists, however, view it as irrelevant). Second, although free will can be defined in various ways, all of them involve aspects of the way people make decisions and initiate actions, which have been studied extensively by neuroscientists. Some of the experimental observations are widely viewed as implying that free will does not exist or is an illusion (but many philosophers see this as a misunderstanding). Third, psychologists have studied the beliefs that the majority of ordinary people hold about free will and its role in assigning moral responsibility.

From an anthropological perspective, free will can be regarded as an explanation for human behavior that justifies a socially sanctioned system of rewards and punishments. Under this definition, free will may be described as a political ideology. In a society where people are taught to believe that humans have free will, free will may be described as a political doctrine.

Quantum physics[edit]

Early scientific thought often portrayed the universe as deterministic – for example in the thought of Democritus or the Cārvākans – and some thinkers claimed that the simple process of gathering sufficient information would allow them to predict future events with perfect accuracy. Modern science, on the other hand, is a mixture of deterministic and stochastic theories.[165] Quantum mechanics predicts events only in terms of probabilities, casting doubt on whether the universe is deterministic at all, although evolution of the universal state vector is completely deterministic. Current physical theories cannot resolve the question of whether determinism is true of the world, being very far from a potential theory of everything, and open to many different interpretations.[166][167]

Assuming that an indeterministic interpretation of quantum mechanics is correct, one may still object that such indeterminism is for all practical purposes confined to microscopic phenomena.[168] This is not always the case: many macroscopic phenomena are based on quantum effects. For instance, some hardware random number generators work by amplifying quantum effects into practically usable signals. A more significant question is whether the indeterminism of quantum mechanics allows for the traditional idea of free will (based on a perception of free will). If a person’s action is, however, only a result of complete quantum randomness, mental processes as experienced have no influence on the probabilistic outcomes (such as volition).[29] According to many interpretations, non-determinism enables free will to exist,[169] while others assert the opposite (because the action was not controllable by the physical being who claims to possess the free will).[170]

Genetics[edit]

Like physicists, biologists have frequently addressed questions related to free will. One of the most heated debates in biology is that of «nature versus nurture», concerning the relative importance of genetics and biology as compared to culture and environment in human behavior.[171] The view of many researchers is that many human behaviors can be explained in terms of humans’ brains, genes, and evolutionary histories.[172][173][174] This point of view raises the fear that such attribution makes it impossible to hold others responsible for their actions. Steven Pinker’s view is that fear of determinism in the context of «genetics» and «evolution» is a mistake, that it is «a confusion of explanation with exculpation«. Responsibility does not require that behavior be uncaused, as long as behavior responds to praise and blame.[175] Moreover, it is not certain that environmental determination is any less threatening to free will than genetic determination.[176]

Neuroscience and neurophilosophy[edit]

It has become possible to study the living brain, and researchers can now watch the brain’s decision-making process at work. A seminal experiment in this field was conducted by Benjamin Libet in the 1980s, in which he asked each subject to choose a random moment to flick their wrist while he measured the associated activity in their brain; in particular, the build-up of electrical signal called the readiness potential (after German Bereitschaftspotential, which was discovered by Kornhuber & Deecke in 1965.[177]). Although it was well known that the readiness potential reliably preceded the physical action, Libet asked whether it could be recorded before the conscious intention to move. To determine when subjects felt the intention to move, he asked them to watch the second hand of a clock. After making a movement, the volunteer reported the time on the clock when they first felt the conscious intention to move; this became known as Libet’s W time.[178]

Libet found that the unconscious brain activity of the readiness potential leading up to subjects’ movements began approximately half a second before the subject was aware of a conscious intention to move.[178][179]

These studies of the timing between actions and the conscious decision bear upon the role of the brain in understanding free will. A subject’s declaration of intention to move a finger appears after the brain has begun to implement the action, suggesting to some that unconsciously the brain has made the decision before the conscious mental act to do so. Some believe the implication is that free will was not involved in the decision and is an illusion. The first of these experiments reported the brain registered activity related to the move about 0.2 s before movement onset.[180] However, these authors also found that awareness of action was anticipatory to activity in the muscle underlying the movement; the entire process resulting in action involves more steps than just the onset of brain activity. The bearing of these results upon notions of free will appears complex.[181][182]

Some argue that placing the question of free will in the context of motor control is too narrow. The objection is that the time scales involved in motor control are very short, and motor control involves a great deal of unconscious action, with much physical movement entirely unconscious. On that basis «…free will cannot be squeezed into time frames of 150–350 ms; free will is a longer term phenomenon» and free will is a higher level activity that «cannot be captured in a description of neural activity or of muscle activation…»[183] The bearing of timing experiments upon free will is still under discussion.

More studies have since been conducted, including some that try to:

- support Libet’s original findings

- suggest that the cancelling or «veto» of an action may first arise subconsciously as well

- explain the underlying brain structures involved

- suggest models that explain the relationship between conscious intention and action