Depiction of a scene from Shakespeare’s play Richard III

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance: a play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on radio or television.[1] Considered as a genre of poetry in general, the dramatic mode has been contrasted with the epic and the lyrical modes ever since Aristotle’s Poetics (c. 335 BC)—the earliest work of dramatic theory.[2]

The term «drama» comes from a Greek word meaning «deed» or «act» (Classical Greek: δρᾶμα, drâma), which is derived from «I do» (Classical Greek: δράω, dráō). The two masks associated with drama represent the traditional generic division between comedy and tragedy.

In English (as was the analogous case in many other European languages), the word play or game (translating the Anglo-Saxon pleġan or Latin ludus) was the standard term for dramas until William Shakespeare’s time—just as its creator was a play-maker rather than a dramatist and the building was a play-house rather than a theatre.[3]

The use of «drama» in a more narrow sense to designate a specific type of play dates from the modern era. «Drama» in this sense refers to a play that is neither a comedy nor a tragedy—for example, Zola’s Thérèse Raquin (1873) or Chekhov’s Ivanov (1887). It is this narrower sense that the film and television industries, along with film studies, adopted to describe «drama» as a genre within their respective media. The term «radio drama» has been used in both senses—originally transmitted in a live performance. It may also be used to refer to the more high-brow and serious end of the dramatic output of radio.[4]

The enactment of drama in theatre, performed by actors on a stage before an audience, presupposes collaborative modes of production and a collective form of reception. The structure of dramatic texts, unlike other forms of literature, is directly influenced by this collaborative production and collective reception.[5]

Mime is a form of drama where the action of a story is told only through the movement of the body. Drama can be combined with music: the dramatic text in opera is generally sung throughout; as for in some ballets dance «expresses or imitates emotion, character, and narrative action».[6] Musicals include both spoken dialogue and songs; and some forms of drama have incidental music or musical accompaniment underscoring the dialogue (melodrama and Japanese Nō, for example).[7] Closet drama is a form that is intended to be read, rather than performed.[8] In improvisation, the drama does not pre-exist the moment of performance; performers devise a dramatic script spontaneously before an audience.[9]

History of Western drama[edit]

Classical Greek drama[edit]

Western drama originates in classical Greece.[10] The theatrical culture of the city-state of Athens produced three genres of drama: tragedy, comedy, and the satyr play. Their origins remain obscure, though by the 5th century BC, they were institutionalised in competitions held as part of festivities celebrating the god Dionysus.[11] Historians know the names of many ancient Greek dramatists, not least Thespis, who is credited with the innovation of an actor («hypokrites«) who speaks (rather than sings) and impersonates a character (rather than speaking in his own person), while interacting with the chorus and its leader («coryphaeus«), who were a traditional part of the performance of non-dramatic poetry (dithyrambic, lyric and epic).[12]

Only a small fraction of the work of five dramatists, however, has survived to this day: we have a small number of complete texts by the tragedians Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, and the comic writers Aristophanes and, from the late 4th century, Menander.[13] Aeschylus’ historical tragedy The Persians is the oldest surviving drama, although when it won first prize at the City Dionysia competition in 472 BC, he had been writing plays for more than 25 years.[14] The competition («agon«) for tragedies may have begun as early as 534 BC; official records («didaskaliai«) begin from 501 BC when the satyr play was introduced.[15] Tragic dramatists were required to present a tetralogy of plays (though the individual works were not necessarily connected by story or theme), which usually consisted of three tragedies and one satyr play (though exceptions were made, as with Euripides’ Alcestis in 438 BC). Comedy was officially recognized with a prize in the competition from 487 to 486 BC.

Five comic dramatists competed at the City Dionysia (though during the Peloponnesian War this may have been reduced to three), each offering a single comedy.[16] Ancient Greek comedy is traditionally divided between «old comedy» (5th century BC), «middle comedy» (4th century BC) and «new comedy» (late 4th century to 2nd BC).[17]

Classical Roman drama[edit]

An ivory statuette of a Roman actor of tragedy, 1st century CE.

Following the expansion of the Roman Republic (509–27 BC) into several Greek territories between 270 and 240 BC, Rome encountered Greek drama.[18] From the later years of the republic and by means of the Roman Empire (27 BC–476 AD), theatre spread west across Europe, around the Mediterranean and reached England; Roman theatre was more varied, extensive and sophisticated than that of any culture before it.[19]

While Greek drama continued to be performed throughout the Roman period, the year 240 BC marks the beginning of regular Roman drama.[20] From the beginning of the empire, however, interest in full-length drama declined in favour of a broader variety of theatrical entertainments.[21] The first important works of Roman literature were the tragedies and comedies that Livius Andronicus wrote from 240 BC.[22] Five years later, Gnaeus Naevius also began to write drama.[22] No plays from either writer have survived. While both dramatists composed in both genres, Andronicus was most appreciated for his tragedies and Naevius for his comedies; their successors tended to specialise in one or the other, which led to a separation of the subsequent development of each type of drama.[22]

By the beginning of the 2nd century BC, drama was firmly established in Rome and a guild of writers (collegium poetarum) had been formed.[23] The Roman comedies that have survived are all fabula palliata (comedies based on Greek subjects) and come from two dramatists: Titus Maccius Plautus (Plautus) and Publius Terentius Afer (Terence).[24] In re-working the Greek originals, the Roman comic dramatists abolished the role of the chorus in dividing the drama into episodes and introduced musical accompaniment to its dialogue (between one-third of the dialogue in the comedies of Plautus and two-thirds in those of Terence).[25] The action of all scenes is set in the exterior location of a street and its complications often follow from eavesdropping.[25]

Plautus, the more popular of the two, wrote between 205 and 184 BC and twenty of his comedies survive, of which his farces are best known; he was admired for the wit of his dialogue and his use of a variety of poetic meters.[26] All of the six comedies that Terence wrote between 166 and 160 BC have survived; the complexity of his plots, in which he often combined several Greek originals, was sometimes denounced, but his double-plots enabled a sophisticated presentation of contrasting human behaviour.[26] No early Roman tragedy survives, though it was highly regarded in its day; historians know of three early tragedians—Quintus Ennius, Marcus Pacuvius, and Lucius Accius.[25]

From the time of the empire, the work of two tragedians survives—one is an unknown author, while the other is the Stoic philosopher Seneca.[27] Nine of Seneca’s tragedies survive, all of which are fabula crepidata (tragedies adapted from Greek originals); his Phaedra, for example, was based on Euripides’ Hippolytus.[28] Historians do not know who wrote the only extant example of the fabula praetexta (tragedies based on Roman subjects), Octavia, but in former times it was mistakenly attributed to Seneca due to his appearance as a character in the tragedy.[27]

Medieval[edit]

Beginning in the early Middle Ages, churches staged dramatised versions of biblical events, known as liturgical dramas, to enliven annual celebrations.[29] The earliest example is the Easter trope Whom do you Seek? (Quem-Quaeritis) (c. 925).[30] Two groups would sing responsively in Latin, though no impersonation of characters was involved. By the 11th century, it had spread through Europe to Russia, Scandinavia, and Italy; excluding Islamic-era Spain.

In the 10th century, Hrosvitha wrote six plays in Latin modeled on Terence’s comedies, but which treated religious subjects.[31] Her plays are the first known to be composed by a female dramatist and the first identifiable Western drama of the post-Classical era.[31] Later, Hildegard of Bingen wrote a musical drama, Ordo Virtutum (c. 1155).[31]

One of the most famous of the early secular plays is the courtly pastoral Robin and Marion, written in the 13th century in French by Adam de la Halle.[32] The Interlude of the Student and the Girl (c. 1300), one of the earliest known in English, seems to be the closest in tone and form to the contemporaneous French farces, such as The Boy and the Blind Man.[33]

Many plays survive from France and Germany in the late Middle Ages, when some type of religious drama was performed in nearly every European country. Many of these plays contained comedy, devils, villains, and clowns.[34] In England, trade guilds began to perform vernacular «mystery plays,» which were composed of long cycles of many playlets or «pageants,» of which four are extant: York (48 plays), Chester (24), Wakefield (32) and the so-called «N-Town» (42). The Second Shepherds’ Play from the Wakefield cycle is a farcical story of a stolen sheep that its protagonist, Mak, tries to pass off as his new-born child asleep in a crib; it ends when the shepherds from whom he has stolen are summoned to the Nativity of Jesus.[35]

Morality plays (a modern term) emerged as a distinct dramatic form around 1400 and flourished in the early Elizabethan era in England. Characters were often used to represent different ethical ideals. Everyman, for example, includes such figures as Good Deeds, Knowledge and Strength, and this characterisation reinforces the conflict between good and evil for the audience. The Castle of Perseverance (c. 1400–1425) depicts an archetypal figure’s progress from birth through to death. Horestes (c. 1567), a late «hybrid morality» and one of the earliest examples of an English revenge play, brings together the classical story of Orestes with a Vice from the medieval allegorical tradition, alternating comic, slapstick scenes with serious, tragic ones.[36] Also important in this period were the folk dramas of the Mummers Play, performed during the Christmas season. Court masques were particularly popular during the reign of Henry VIII.[37]

Elizabethan and Jacobean[edit]

One of the great flowerings of drama in England occurred in the 16th and 17th centuries. Many of these plays were written in verse, particularly iambic pentameter. In addition to Shakespeare, such authors as Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Middleton, and Ben Jonson were prominent playwrights during this period. As in the medieval period, historical plays celebrated the lives of past kings, enhancing the image of the Tudor monarchy. Authors of this period drew some of their storylines from Greek mythology and Roman mythology or from the plays of eminent Roman playwrights such as Plautus and Terence.

English Restoration comedy[edit]

Restoration comedy refers to English comedies written and performed in England during the Restoration period from 1660 to 1710. Comedy of manners is used as a synonym of Restoration comedy.[38] After public theatre had been banned by the Puritan regime, the re-opening of the theatres in 1660 with the Restoration of Charles II signalled a renaissance of English drama.[39] Restoration comedy is known for its sexual explicitness, urbane, cosmopolitan wit, up-to-the-minute topical writing, and crowded and bustling plots. Its dramatists stole freely from the contemporary French and Spanish stage, from English Jacobean and Caroline plays, and even from Greek and Roman classical comedies, combining the various plotlines in adventurous ways. Resulting differences of tone in a single play were appreciated rather than frowned on, as the audience prized «variety» within as well as between plays. Restoration comedy peaked twice. The genre came to spectacular maturity in the mid-1670s with an extravaganza of aristocratic comedies. Twenty lean years followed this short golden age, although the achievement of the first professional female playwright, Aphra Behn, in the 1680s is an important exception. In the mid-1690s, a brief second Restoration comedy renaissance arose, aimed at a wider audience. The comedies of the golden 1670s and 1690s peak times are significantly different from each other.

The unsentimental or «hard» comedies of John Dryden, William Wycherley, and George Etherege reflected the atmosphere at Court and celebrated with frankness an aristocratic macho lifestyle of unremitting sexual intrigue and conquest. The Earl of Rochester, real-life Restoration rake, courtier and poet, is flatteringly portrayed in Etherege’s The Man of Mode (1676) as a riotous, witty, intellectual, and sexually irresistible aristocrat, a template for posterity’s idea of the glamorous Restoration rake (actually never a very common character in Restoration comedy). The single play that does most to support the charge of obscenity levelled then and now at Restoration comedy is probably Wycherley’s masterpiece The Country Wife (1675), whose title contains a lewd pun and whose notorious «china scene» is a series of sustained double entendres.[40]

During the second wave of Restoration comedy in the 1690s, the «softer» comedies of William Congreve and John Vanbrugh set out to appeal to more socially diverse audience with a strong middle-class element, as well as to female spectators. The comic focus shifts from young lovers outwitting the older generation to the vicissitudes of marital relations. In Congreve’s Love for Love (1695) and The Way of the World (1700), the give-and-take set pieces of couples testing their attraction for one another have mutated into witty prenuptial debates on the eve of marriage, as in the latter’s famous «Proviso» scene. Vanbrugh’s The Provoked Wife (1697) has a light touch and more humanly recognisable characters, while The Relapse (1696) has been admired for its throwaway wit and the characterisation of Lord Foppington, an extravagant and affected burlesque fop with a dark side.[41] The tolerance for Restoration comedy even in its modified form was running out by the end of the 17th century, as public opinion turned to respectability and seriousness even faster than the playwrights did.[42] At the much-anticipated all-star première in 1700 of The Way of the World, Congreve’s first comedy for five years, the audience showed only moderate enthusiasm for that subtle and almost melancholy work. The comedy of sex and wit was about to be replaced by sentimental comedy and the drama of exemplary morality.

Modern and postmodern[edit]

The pivotal and innovative contributions of the 19th-century Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen and the 20th-century German theatre practitioner Bertolt Brecht dominate modern drama; each inspired a tradition of imitators, which include many of the greatest playwrights of the modern era.[43] The works of both playwrights are, in their different ways, both modernist and realist, incorporating formal experimentation, meta-theatricality, and social critique.[44] In terms of the traditional theoretical discourse of genre, Ibsen’s work has been described as the culmination of «liberal tragedy», while Brecht’s has been aligned with an historicised comedy.[45]

Other important playwrights of the modern era include Antonin Artaud, August Strindberg, Anton Chekhov, Frank Wedekind, Maurice Maeterlinck, Federico García Lorca, Eugene O’Neill, Luigi Pirandello, George Bernard Shaw, Ernst Toller, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, Jean Genet, Eugène Ionesco, Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Dario Fo, Heiner Müller, and Caryl Churchill.

Opera[edit]

Western opera is a dramatic art form that arose during the Renaissance[46] in an attempt to revive the classical Greek drama in which dialogue, dance, and song were combined. Being strongly intertwined with western classical music, the opera has undergone enormous changes in the past four centuries and it is an important form of theatre until this day. Noteworthy is the major influence of the German 19th-century composer Richard Wagner on the opera tradition. In his view, there was no proper balance between music and theatre in the operas of his time, because the music seemed to be more important than the dramatic aspects in these works. To restore the connection with the classical drama, he entirely renewed the operatic form to emphasize the equal importance of music and drama in works that he called «music dramas».

Chinese opera has seen a more conservative development over a somewhat longer period of time.

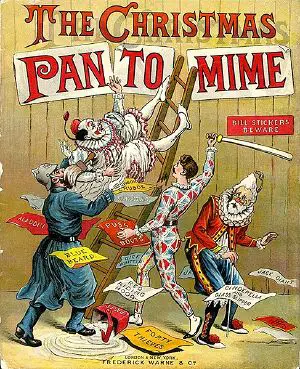

Pantomime[edit]

Pantomime (informally panto),[47] is a type of musical comedy stage production, designed for family entertainment. It was developed in England and is still performed throughout the United Kingdom, generally during the Christmas and New Year season and, to a lesser extent, in other English-speaking countries. Modern pantomime includes songs, gags, slapstick comedy and dancing, employs gender-crossing actors, and combines topical humour with a story loosely based on a well-known fairy tale, fable or folk tale.[48][49] It is a participatory form of theatre, in which the audience is expected to sing along with certain parts of the music and shout out phrases to the performers.

These stories follow in the tradition of fables and folk tales. Usually, there is a lesson learned, and with some help from the audience, the hero/heroine saves the day. This kind of play uses stock characters seen in masque and again commedia dell’arte, these characters include the villain (doctore), the clown/servant (Arlechino/Harlequin/buttons), the lovers etc. These plays usually have an emphasis on moral dilemmas, and good always triumphs over evil, this kind of play is also very entertaining making it a very effective way of reaching many people.

Pantomime has a long theatrical history in Western culture dating back to classical theatre. It developed partly from the 16th century commedia dell’arte tradition of Italy, as well as other European and British stage traditions, such as 17th-century masques and music hall.[48] An important part of the pantomime, until the late 19th century, was the harlequinade.[50] Outside Britain the word «pantomime» is usually used to mean miming, rather than the theatrical form discussed here.[51]

Mime[edit]

Mime is a theatrical medium where the action of a story is told through the movement of the body, without the use of speech. Performance of mime occurred in Ancient Greece, and the word is taken from a single masked dancer called Pantomimus, although their performances were not necessarily silent.[52] In Medieval Europe, early forms of mime, such as mummer plays and later dumbshows, evolved. In the early nineteenth century Paris, Jean-Gaspard Deburau solidified the many attributes that we have come to know in modern times, including the silent figure in whiteface.[53]

Jacques Copeau, strongly influenced by Commedia dell’arte and Japanese Noh theatre, used masks in the training of his actors. Étienne Decroux, a pupil of his, was highly influenced by this and started exploring and developing the possibilities of mime and refined corporeal mime into a highly sculptural form, taking it outside of the realms of naturalism. Jacques Lecoq contributed significantly to the development of mime and physical theatre with his training methods.[54]

Ballet[edit]

While some ballet emphasises «the lines and patterns of movement itself» dramatic dance «expresses or imitates emotion, character, and narrative action».[6] Such ballets are theatrical works that have characters and «tell a story»,[55] Dance movements in ballet «are often closely related to everyday forms of physical expression, [so that] there is an expressive quality inherent in nearly all dancing», and this is used to convey both action and emotions; mime is also used.[55] Examples include Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, which tells the story of Odette, a princess turned into a swan by an evil sorcerer’s curse, Sergei Prokofiev’s ballet Romeo and Juliet, based on Shakespeare’s famous play, and Igor Stravinsky’s Petrushka, which tells the story of the loves and jealousies of three puppets.

Creative drama[edit]

Creative drama includes dramatic activities and games used primarily in educational settings with children. Its roots in the United States began in the early 1900s. Winifred Ward is considered to be the founder of creative drama in education, establishing the first academic use of drama in Evanston, Illinois.[56]

Asian drama[edit]

India[edit]

The earliest form of Indian drama was the Sanskrit drama.[57] Between the 1st century AD and the 10th was a period of relative peace in the history of India during which hundreds of plays were written.[58] With the Islamic conquests that began in the 10th and 11th centuries, theatre was discouraged or forbidden entirely.[59] Later, in an attempt to re-assert indigenous values and ideas, village theatre was encouraged across the subcontinent, developing in various regional languages from the 15th to the 19th centuries.[60] The Bhakti movement was influential in performances in several regions. Apart from regional languages, Assam saw the rise of Vaishnavite drama in an artificially mixed literary language called Brajavali.[61] A distinct form of one-act plays called Ankia Naat developed in the works of Sankardev,[62] a particular presentation of which is called Bhaona.[63] Modern Indian theatre developed during the period of colonial rule under the British Empire, from the mid-19th century until the mid-20th.[64]

Sanskrit theatre[edit]

The earliest-surviving fragments of Sanskrit drama date from the 1st century AD.[65] The wealth of archeological evidence from earlier periods offers no indication of the existence of a tradition of theatre.[66] The ancient Vedas (hymns from between 1500 and 1000 BC that are among the earliest examples of literature in the world) contain no hint of it (although a small number are composed in a form of dialogue) and the rituals of the Vedic period do not appear to have developed into theatre.[66] The Mahābhāṣya by Patañjali contains the earliest reference to what may have been the seeds of Sanskrit drama.[67] This treatise on grammar from 140 BC provides a feasible date for the beginnings of theatre in India.[67]

The major source of evidence for Sanskrit theatre is A Treatise on Theatre (Nātyaśāstra), a compendium whose date of composition is uncertain (estimates range from 200 BC to 200 AD) and whose authorship is attributed to Bharata Muni. The Treatise is the most complete work of dramaturgy in the ancient world. It addresses acting, dance, music, dramatic construction, architecture, costuming, make-up, props, the organisation of companies, the audience, competitions, and offers a mythological account of the origin of theatre.[67]

Its drama is regarded as the highest achievement of Sanskrit literature.[68] It utilised stock characters, such as the hero (nayaka), heroine (nayika), or clown (vidusaka). Actors may have specialised in a particular type. It was patronized by the kings as well as village assemblies. Famous early playwrights include Bhasa, Kalidasa (famous for Vikrama and Urvashi, Malavika and Agnimitra, and The Recognition of Shakuntala), Śudraka (famous for The Little Clay Cart), Asvaghosa, Daṇḍin, and Emperor Harsha (famous for Nagananda, Ratnavali, and Priyadarsika). Śakuntalā (in English translation) influenced Goethe’s Faust (1808–1832).[68]

Mobile theatre[edit]

A distinct form of theatre has developed in India where the entire crew travels performing plays from place to place, with makeshift stages and equipment, particularly in the eastern parts of the country. Jatra (Bengali for «travel»), originating in the Vaishnavite movement of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu in Bengal, is a tradition that follows this format.[69] Vaishnavite plays in the neighbouring state of Assam, pioneered by Srimanta Sankardeva, takes the forms of Ankia Naat and Bhaona. These, along with Western influences, have inspired the development of modern mobile theatre, known in Assamese as Bhramyoman, in Assam.[70] Modern Bhramyoman stages everything from Hindu mythology to adaptations of Western classics and Hollywood movies,[71] and make use of modern techniques, such as live visual effects.[72] Assamese mobile theatre is estimated to be an industry worth a hundred million.[73] The self-contained nature of Bhramyoman, with all equipment and even the stage being carried by the troop itself, allows staging shows even in remote villages, giving wider reach. Pioneers of this industry include Achyut Lahkar, Brajanath Sarma etc.

Modern Indian drama[edit]

Rabindranath Tagore was a pioneering modern playwright who wrote plays noted for their exploration and questioning of nationalism, identity, spiritualism and material greed.[74] His plays are written in Bengali and include Chitra (Chitrangada, 1892), The King of the Dark Chamber (Raja, 1910), The Post Office (Dakghar, 1913), and Red Oleander (Raktakarabi, 1924).[74] Girish Karnad is a noted playwright, who has written a number of plays that use history and mythology, to critique and problematize ideas and ideals that are of contemporary relevance. Karnad’s numerous plays such as Tughlaq, Hayavadana, Taledanda, and Naga-Mandala are significant contributions to Indian drama. Vijay Tendulkar and Mahesh Dattani are amongst the major Indian playwrights of the 20th century. Mohan Rakesh in Hindi and Danish Iqbal in Urdu are considered architects of new age Drama. Mohan Rakesh’s Aadhe Adhoore and Danish Iqbal’s Dara Shikoh are considered modern classics.

China[edit]

Chinese theatre has a long and complex history. Today it is often called Chinese opera although this normally refers specifically to the popular form known as Beijing opera and Kunqu; there have been many other forms of theatre in China, such as zaju.

Japan[edit]

Japanese Nō drama is a serious dramatic form that combines drama, music, and dance into a complete aesthetic performance experience. It developed in the 14th and 15th centuries and has its own musical instruments and performance techniques, which were often handed down from father to son. The performers were generally male (for both male and female roles), although female amateurs also perform Nō dramas. Nō drama was supported by the government, and particularly the military, with many military commanders having their own troupes and sometimes performing themselves. It is still performed in Japan today.[75]

Kyōgen is the comic counterpart to Nō drama. It concentrates more on dialogue and less on music, although Nō instrumentalists sometimes appear also in Kyōgen. Kabuki drama, developed from the 17th century, is another comic form, which includes dance.

Modern theatrical and musical drama has also developed in Japan in forms such as shingeki and the Takarazuka Revue.

See also[edit]

- Antitheatricality

- Applied Drama

- Augustan drama

- Christian drama

- Closet drama

- Comedy drama

- Costume drama

- Crime drama

- Domestic drama

- Drama school

- Dramatic structure

- Dramatic theory

- Drama annotation

- Dramaturgy

- Entertainment

- Flash drama

- Folk play

- Heroic drama

- History of theatre

- Hyperdrama

- Legal drama

- Medical drama

- Melodrama

- Monodrama

- Mystery play

- One act play

- Political drama

- Soap opera

- Theatre awards

- Two-hander

- Verse drama and dramatic verse

- Well-made play

- Yakshagana

Notes[edit]

- ^ Elam (1980, 98).

- ^ Francis Fergusson writes that «a drama, as distinguished from a lyric, is not primarily a composition in the verbal medium; the words result, as one might put it, from the underlying structure of incident and character. As Aristotle remarks, ‘the poet, or «maker» should be the maker of plots rather than of verses; since he is a poet because he imitates, and what he imitates are actions'» (1949, 8).

- ^ Wickham (1959, 32–41; 1969, 133; 1981, 68–69). The sense of the creator of plays as a «maker» rather than a «writer» is preserved in the word playwright. The Theatre, one of the first purpose-built playhouses in London, was an intentional reference to the Latin term for that particular playhouse, rather than a term for the buildings in general (1967, 133). The word ‘dramatist’ «was at that time still unknown in the English language» (1981, 68).

- ^ Banham (1998, 894–900).

- ^ Pfister (1977, 11).

- ^ a b Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ^ See the entries for «opera», «musical theatre, American», «melodrama» and «Nō» in Banham (1998).

- ^ Manfred by Byron, for example, is a good example of a «dramatic poem.» See the entry on «Byron (George George)» in Banham (1998).

- ^ Some forms of improvisation, notably the Commedia dell’arte, improvise on the basis of ‘lazzi’ or rough outlines of scenic action (see Gordon (1983) and Duchartre (1929)). All forms of improvisation take their cue from their immediate response to one another, their characters’ situations (which are sometimes established in advance), and, often, their interaction with the audience. The classic formulations of improvisation in the theatre originated with Joan Littlewood and Keith Johnstone in the UK and Viola Spolin in the US; see Johnstone (1981) and Spolin (1963).

- ^ Brown (1998, 441), Cartledge (1997, 3–5), Goldhill (1997, 54), and Ley (2007, 206). Taxidou notes that «most scholars now call ‘Greek’ tragedy ‘Athenian’ tragedy, which is historically correct» (2004, 104). Brown writes that ancient Greek drama «was essentially the creation of classical Athens: all the dramatists who were later regarded as classics were active at Athens in the 5th and 4th centuries BC (the time of the Athenian democracy), and all the surviving plays date from this period» (1998, 441). «The dominant culture of Athens in the fifth century», Goldhill writes, «can be said to have invented theatre» (1997, 54).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 13–15) and Banham (1998, 441–447).

- ^ Banham (1998, 441–444). For more information on these ancient Greek dramatists, see the articles categorised under «Ancient Greek dramatists and playwrights» in Wikipedia.

- ^ The theory that Prometheus Bound was not written by Aeschylus would bring this number to six dramatists whose work survives.

- ^ Banham (1998,

and Brockett and Hildy (2003, 15–16).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 13, 15) and Banham (1998, 442).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 18) and Banham (1998, 444–445).

- ^ Banham (1998, 444–445).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 43).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 36, 47).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 43). For more information on the ancient Roman dramatists, see the articles categorised under «Ancient Roman dramatists and playwrights» in Wikipedia.

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 46–47).

- ^ a b c Brockett and Hildy (2003, 47).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 47–48).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 48–49).

- ^ a b c Brockett and Hildy (2003, 49).

- ^ a b Brockett and Hildy (2003, 48).

- ^ a b Brockett and Hildy (2003, 50).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 49–50).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 76, 78). Many churches would have only performed one or two liturgical dramas per year and a larger number never performed any at all.

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 76).

- ^ a b c Brockett and Hildy (2003, 77).

- ^ Wickham (1981, 191; 1987, 141).

- ^ Bevington (1962, 9, 11, 38, 45), Dillon (2006, 213), and Wickham (1976, 195; 1981, 189–190). In Early English Stages (1981), Wickham points to the existence of The Interlude of the Student and the Girl as evidence that the old-fashioned view that comedy began in England in the 1550s with Gammer Gurton’s Needle and Ralph Roister Doister is mistaken, ignoring as it does a rich tradition of medieval comic drama; see Wickham (1981, 178).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 86)

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 97).

- ^ Spivack (1958, 251–303), Bevington (1962, 58–61, 81–82, 87, 183), and Weimann (1978, 155).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 101–103).

- ^ George Henry Nettleton, Arthur British dramatists from Dryden to Sheridan p. 149

- ^ Hatch, Mary Jo (2009). The Three Faces of Leadership: Manager, Artist, Priest. John Wiley & Sons. p. 47.

- ^ The «China scene» from Wycherley’s play on YouTube

- ^ The Provoked Wife is something of a Restoration problem play in its attention to the subordinate legal position of married women and the complexities of «divorce» and separation, issues that had been highlighted in the mid-1690s by some notorious cases before the House of Lords.

- ^ Interconnected causes for this shift in taste were demographic change, the Glorious Revolution of 1688, William’s and Mary’s dislike of the theatre, and the lawsuits brought against playwrights by the Society for the Reformation of Manners (founded in 1692). When Jeremy Collier attacked Congreve and Vanbrugh in his Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage in 1698, he was confirming a shift in audience taste that had already taken place.

- ^ Williams (1993, 25–26) and Moi (2006, 17). Moi writes that «Ibsen is the most important playwright writing after Shakespeare. He is the founder of modern theater. His plays are world classics, staged on every continent, and studied in classrooms everywhere. In any given year, there are hundreds of Ibsen productions in the world.» Ibsenites include George Bernard Shaw and Arthur Miller; Brechtians include Dario Fo, Joan Littlewood, W. H. Auden Peter Weiss, Heiner Müller, Peter Hacks, Tony Kushner, Caryl Churchill, John Arden, Howard Brenton, Edward Bond, and David Hare.

- ^ Moi (2006, 1, 23–26). Taxidou writes: «It is probably historically more accurate, although methodologically less satisfactory, to read the Naturalist movement in the theatre in conjunction with the more anti-illusionist aesthetics of the theatres of the same period. These interlock and overlap in all sorts of complicated ways, even when they are vehemently denouncing each other (perhaps particularly when) in the favoured mode of the time, the manifesto» (2007, 58).

- ^ Williams (1966) and Wright (1989).

- ^ «opera | History & Facts». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ Lawner, p. 16

- ^ a b Reid-Walsh, Jacqueline. «Pantomime», The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature, Jack Zipes (ed.), Oxford University Press (2006), ISBN 9780195146561

- ^ Mayer (1969), p. 6

- ^ «The History of Pantomime», It’s-Behind-You.com, 2002, accessed 10 February 2013

- ^ Webster’s New World Dictionary, World Publishing Company, 2nd College Edition, 1980, p. 1027

- ^ Gutzwiller (2007).

- ^ Rémy (1954).

- ^ Callery (2001).

- ^ a b Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ^ Ehrlich (1974, 75–80).

- ^ Richmond, Swann, and Zarrilli (1993, 12).

- ^ Brandon (1997, 70) and Richmond (1998, 516).

- ^ Brandon (1997, 72) and Richmond (1998, 516).

- ^ Brandon (1997, 72), Richmond (1998, 516), and Richmond, Swann, and Zarrilli (1993, 12).

- ^ (Neog 1980, p. 246)

- ^ Neog, Maheswar (1975). Assamese Drama and Theatre: A Series of Two Lectures Delivered at the Indian School of Drama and Asian Theatre Centre, New Delhi, April 1962. Neog.

- ^ Neog, Maheswar (1984). Bhaona: The Ritual Play of Assam. Sangeet Natak Academy.

- ^ Richmond (1998, 516) and Richmond, Swann, and Zarrilli (1993, 13).

- ^ Brandon (1981, xvii) and Richmond (1998, 516–517).

- ^ a b Richmond (1998, 516).

- ^ a b c Richmond (1998, 517).

- ^ a b Brandon (1981, xvii).

- ^ Jatra South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, by Peter J. Claus, Sarah Diamond, Margaret Ann Mills. Published by Taylor & Francis, 2003. ISBN 0-415-93919-4. Page 307.

- ^ RAMESH MENON (15 February 1988). «Mobile theatre strikes deep roots in Assam». India Today. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ «Mobile theatre is successful because we stage plays in villages».

- ^ «Assamese theatre».

- ^ «Screen salute to mobile theatre pioneer – Veteran Ratna Ojha?s documenta Achyut Lahkar».

- ^ a b Banham (1998, 1051).

- ^ «Background to Noh-Kyogen». Archived from the original on 15 July 2005. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

Sources[edit]

- Banham, Martin, ed. 1998. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43437-8.

- Baumer, Rachel Van M., and James R. Brandon, eds. 1981. Sanskrit Theatre in Performance. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1993. ISBN 978-81-208-0772-3.

- Bevington, David M. 1962. From Mankind to Marlowe: Growth of Structure in the Popular Drama of Tudor England. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bhatta, S. Krishna. 1987. Indian English Drama: A Critical Study. New Delhi: Sterling.

- Brandon, James R. 1981. Introduction. In Baumer and Brandon (1981, xvii–xx).

- Brandon, James R., ed. 1997. The Cambridge Guide to Asian Theatre.’ 2nd, rev. ed. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. ISBN 978-0-521-58822-5.

- Brockett, Oscar G. and Franklin J. Hildy. 2003. History of the Theatre. Ninth edition, International edition. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-41050-2.

- Brown, Andrew. 1998. «Ancient Greece.» In The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Ed. Martin Banham. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. 441–447. ISBN 0-521-43437-8.

- Burt, Daniel S. 2008.The Drama 100: A Ranking of the Greatest Plays of All Time. Facts on File ser. New York: Facts on File/Infobase. ISBN 978-0-8160-6073-3.

- Callery, Dympha. 2001. Through the Body: A Practical Guide to Physical Theatre. London: Nick Hern. ISBN 1-854-59630-6.

- Carlson, Marvin. 1993. Theories of the Theatre: A Historical and Critical Survey from the Greeks to the Present. Expanded ed. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8154-3.

- Cartledge, Paul. 1997. «‘Deep Plays’: Theatre as Process in Greek Civic Life.» In Easterling (1997c, 3–35).

- Chakraborty, Kaustav, ed. 2011. Indian English Drama. New Delhi: PHI Learning.

- Deshpande, G. P., ed. 2000. Modern Indian Drama: An Anthology. New Delhi: Sahitya Akedemi.

- Dillon, Janette. 2006. The Cambridge Introduction to Early English Theatre. Cambridge Introductions to Literature ser. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83474-2.

- Duchartre, Pierre Louis. 1929. The Italian Comedy. Unabridged republication. New York: Dover, 1966. ISBN 0-486-21679-9.

- Dukore, Bernard F., ed. 1974. Dramatic Theory and Criticism: Greeks to . Florence, Kentucky: Heinle & Heinle. ISBN 0-03-091152-4.

- Durant, Will & Ariel Durant. 1963 The Story of Civilization, Volume II: The Life of Greece. 11 vols. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Easterling, P. E. 1997a. «A Show for Dionysus.» In Easterling (1997c, 36–53).

- Easterling, P. E. 1997b. «Form and Performance.» In Easterling (1997c, 151–177).

- Easterling, P. E., ed. 1997c. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy. Cambridge Companions to Literature ser. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-42351-1.

- Ehrlich, Harriet W. 1974. «Creative Dramatics as a Classroom Teaching Technique.» Elementary English 51:1 (January):75–80.

- Elam, Keir. 1980. The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama. New Accents Ser. London and New York: Methuen. ISBN 0-416-72060-9.

- Fergusson, Francis. 1949. The Idea of a Theater: A Study of Ten Plays, The Art of Drama in a Changing Perspective. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton UP, 1968. ISBN 0-691-01288-1.

- Goldhill, Simon. 1997. «The Audience of Athenian Tragedy.» In Easterling (1997c, 54–68).

- Gordon, Mel. 1983. Lazzi: The Comic Routines of the Commedia dell’Arte. New York: Performing Arts Journal Publications. ISBN 0-933826-69-9.

- Gutzwiller, Kathryn. 2007. A Guide to Hellenistic Literature. London: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-23322-9.

- Harsh, Philip Whaley. 1944. A Handbook of Classical Drama. Stanford: Stanford UP; Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Johnstone, Keith. 1981. Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre Rev. ed. London: Methuen, 2007. ISBN 0-7136-8701-0.

- Ley, Graham. 2006. A Short Introduction to the Ancient Greek Theater. Rev. ed. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P. ISBN 0-226-47761-4.

- Neog, Maheswar (1980). Early History of the Vaiṣṇava Faith and Movement in Assam: Śaṅkaradeva and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass Publishe. ISBN 978-81-208-0007-6.

- O’Brien, Nick. 2010. Stanislavski In Practise. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415568432.

- O’Brien, Nick. 2007. The Theatricality of Greek Tragedy: Playing Space and Chorus. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P. ISBN 0-226-47757-6.

- Pandey, Sudhakar, and Freya Taraporewala, eds. 1999. Studies in Contemporary India. New Delhi: Prestige.

- Pfister, Manfred. 1977. The Theory and Analysis of Drama. Trans. John Halliday. European Studies in English Literature Ser. Cambridige: Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-521-42383-X.

- Rémy, Tristan. 1954. Jean-Gaspard Deburau. Paris: L’Arche.

- Rehm, Rush. 1992. Greek Tragic Theatre. Theatre Production Studies ser. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11894-8.

- Richmond, Farley. 1998. «India.» In Banham (1998, 516–525).

- Richmond, Farley P., Darius L. Swann, and Phillip B. Zarrilli, eds. 1993. Indian Theatre: Traditions of Performance. U of Hawaii P. ISBN 978-0-8248-1322-2.

- Spivack, Bernard. 1958. Shakespeare and the Allegory of Evil: The History of a Metaphor in Relation to his Major Villains. NY and London: Columbia UP. ISBN 0-231-01912-2.

- Spolin, Viola. 1967. Improvisation for the Theater. Third rev. ed Evanston, II Northwestern University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8101-4008-X.

- Taxidou, Olga. 2004. Tragedy, Modernity and Mourning. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP. ISBN 0-7486-1987-9.

- Wickham, Glynne. 1959. Early English Stages: 1300–1660. Vol. 1. London: Routledge.

- Wickham, Glynne. 1969. Shakespeare’s Dramatic Heritage: Collected Studies in Mediaeval, Tudor and Shakespearean Drama. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-710-06069-6.

- Wickham, Glynne, ed. 1976. English Moral Interludes. London: Dent. ISBN 0-874-71766-3.

- Wickham, Glynne. 1981. Early English Stages: 1300–1660. Vol. 3. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-710-00218-1.

- Wickham, Glynne. 1987. The Medieval Theatre. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-31248-5.

- Weimann, Robert. 1978. Shakespeare and the Popular Tradition in the Theater: Studies in the Social Dimension of Dramatic Form and Function. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3506-2.

- Weimann, Robert. 2000. Author’s Pen and Actor’s Voice: Playing and Writing in Shakespeare’s Theatre. Ed. Helen Higbee and William West. Cambridge Studies in Renaissance Literature and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78735-1.

External links[edit]

Look up drama in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Greek & Roman Mask Timeline

Drama definition in literature: A drama is defined as a piece of literature of which the intended purpose is to be performed in front of an audience.

What is Drama in Literature?

Drama meaning: A drama is a type of literature that is written for the purpose of being performed in front of an audience. This type of writing is written in the form of a script, and the story is told through the lines of the characters played by actors.

Example of Drama

The television show Grey’s Anatomy is considered to be a genre. This show is written with the intended purpose of actors performing the lines for their viewing audience.

Types of Drama in Literature

Comedy: A comedy is a type of drama that is written to be entertaining or amusing for the audience.

- The television show Seinfeld is considered a comedy. This sitcom follows the lives of four friends and the humorous situations they encounter together.

Tragedy: A tragedy is a type of drama that can be described as serious in nature and often includes a catastrophic ending.

- William Shakespeare’s famous play Romeo and Juliet is an example of a tragedy. In this play, two young children fall in love and feel the need to hide this from their parents due to their feuding families. However, their rash thinking leads them to their ultimate deaths.

Farce: A farce is a subcategory of comedy. Theses low comedies include ridiculous and slapstick comedic situations in order to create humor for the audience.

- The movie Dumb and Dumber is an example of a farce. This movie follows the story of two caricatures on a mission to return a briefcase to a beautiful lady. Throughout the film the two encounter several ridiculous and crude situations.

Melodrama: While it originally referred to dramas that included accompanying music, melodramas now refer to plays that include highly emotional situations in order to play on the feelings of the audience.

- The play Les parents terribles by Jean Cocteau is an example of a melodrama that involves several layers of over dramatic situations including cheating and suicide.

Musical Drama: Musical dramas refer to plays in which characters engage in dialogue but also include scenes in which the passion of the character is so great he expresses himself in song.

- Andrew Lloyd Weber’s The Phantom of the Opera is a well-known example of a musical drama that tells the story of obsession.

The Function of Drama

Dramas serve the function of entertainment for the audience. While reading a story is powerful, watching the story be performed by actors adds a level of realism to the work. In the age of binge watching, many people enjoy spending leisure time watching dramas specifically in the forms of movies or television.

Summary: What is a Drama in Literature?

Define drama in literature: In summation, a drama is a work of literature written for the intended purpose of being performed for an audience. Dramas are written in the form of a script and actors perform interpretations of the characters involved in order to tell the story the viewers versus reading a story in novel form.

Final Example:

The hit Grease by Jim Jacobs and Warren Casey, is an example of a musical drama. In this popular play and movie, viewers are taken through the story of high school love between two teens who are completely opposite outside the love they share for each other.

Contents

- 1 What is Drama in Literature?

- 2 Example of Drama

- 3 Types of Drama in Literature

- 4 The Function of Drama

- 5 Summary: What is a Drama in Literature?

Educalingo cookies are used to personalize ads and get web traffic statistics. We also share information about the use of the site with our social media, advertising and analytics partners.

Download the app

educalingo

Comedy has always been more challenging for me than drama.

Kelli Berglund

ETYMOLOGY OF THE WORD DRAMA

From Late Latin: a play, from Greek: something performed, from drān to do.

Etymology is the study of the origin of words and their changes in structure and significance.

PRONUNCIATION OF DRAMA

GRAMMATICAL CATEGORY OF DRAMA

Drama is a noun.

A noun is a type of word the meaning of which determines reality. Nouns provide the names for all things: people, objects, sensations, feelings, etc.

WHAT DOES DRAMA MEAN IN ENGLISH?

Drama

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance. The term comes from a Greek word meaning «action», which is derived from the verb meaning «to do» or «to act». The enactment of drama in theatre, performed by actors on a stage before an audience, presupposes collaborative modes of production and a collective form of reception. The structure of dramatic texts, unlike other forms of literature, is directly influenced by this collaborative production and collective reception. The early modern tragedy Hamlet by Shakespeare and the classical Athenian tragedy Oedipus the King by Sophocles are among the masterpieces of the art of drama. A modern example is Long Day’s Journey into Night by Eugene O’Neill. The two masks associated with drama represent the traditional generic division between comedy and tragedy. They are symbols of the ancient Greek Muses, Thalia and Melpomene. Thalia was the Muse of comedy, while Melpomene was the Muse of tragedy.

Definition of drama in the English dictionary

The first definition of drama in the dictionary is a work to be performed by actors on stage, radio, or television; play. Other definition of drama is the genre of literature represented by works intended for the stage. Drama is also the art of the writing and production of plays.

WORDS THAT RHYME WITH DRAMA

Synonyms and antonyms of drama in the English dictionary of synonyms

SYNONYMS OF «DRAMA»

The following words have a similar or identical meaning as «drama» and belong to the same grammatical category.

Translation of «drama» into 25 languages

TRANSLATION OF DRAMA

Find out the translation of drama to 25 languages with our English multilingual translator.

The translations of drama from English to other languages presented in this section have been obtained through automatic statistical translation; where the essential translation unit is the word «drama» in English.

Translator English — Chinese

戏剧

1,325 millions of speakers

Translator English — Spanish

drama

570 millions of speakers

English

drama

510 millions of speakers

Translator English — Hindi

नाटक

380 millions of speakers

Translator English — Arabic

دراما

280 millions of speakers

Translator English — Russian

драма

278 millions of speakers

Translator English — Portuguese

drama

270 millions of speakers

Translator English — Bengali

নাটক

260 millions of speakers

Translator English — French

drame

220 millions of speakers

Translator English — Malay

Drama

190 millions of speakers

Translator English — German

Drama

180 millions of speakers

Translator English — Japanese

劇

130 millions of speakers

Translator English — Korean

극

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Javanese

Drama

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Vietnamese

kịch

80 millions of speakers

Translator English — Tamil

நாடகம்

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Marathi

नाटक

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Turkish

dram

70 millions of speakers

Translator English — Italian

dramma

65 millions of speakers

Translator English — Polish

dramat

50 millions of speakers

Translator English — Ukrainian

драма

40 millions of speakers

Translator English — Romanian

dramă

30 millions of speakers

Translator English — Greek

δράμα

15 millions of speakers

Translator English — Afrikaans

drama

14 millions of speakers

Translator English — Swedish

skådespel

10 millions of speakers

Translator English — Norwegian

drama

5 millions of speakers

Trends of use of drama

TENDENCIES OF USE OF THE TERM «DRAMA»

The term «drama» is very widely used and occupies the 3.336 position in our list of most widely used terms in the English dictionary.

FREQUENCY

Very widely used

The map shown above gives the frequency of use of the term «drama» in the different countries.

Principal search tendencies and common uses of drama

List of principal searches undertaken by users to access our English online dictionary and most widely used expressions with the word «drama».

FREQUENCY OF USE OF THE TERM «DRAMA» OVER TIME

The graph expresses the annual evolution of the frequency of use of the word «drama» during the past 500 years. Its implementation is based on analysing how often the term «drama» appears in digitalised printed sources in English between the year 1500 and the present day.

Examples of use in the English literature, quotes and news about drama

10 QUOTES WITH «DRAMA»

Famous quotes and sentences with the word drama.

Comedy, drama, Westerns, sci-fi… it’s all fine if the story’s compelling and the character is interesting to me. I do like action a lot.

For some reason, comedy just comes easily to me, and I feel like I can do it. I don’t have any doubt. When I work on drama, there’s always a sense of ‘Did I find this person’s truth at the bottom of this?’ And it’s hard to tell sometimes.

A cosmic war is like a ritual drama in which participants act out on Earth a battle they believe is actually taking place in the heavens.

I always enjoyed participating in artistic endeavors, and I remember in high school participating in chorus, drama and singing madrigals, mainly because they were an easy A. I loved being in plays and musicals too, but you didn’t really get credit for those.

Comedy has always been more challenging for me than drama.

I think if you turn down the volume on the good comedy, you should not even know if it’s a comedy or not. It should look like a drama.

I wasn’t good at examinations, but I went to a very good secondary school — Bolton-on-Dearne — with wonderful teachers, who taught me drama and encouraged me in every way.

When I left drama school, there were dozens of rep theatres you could apply to where you got a good training.

Comedy has to be so much cleaner than drama. You can’t layer it in the way you can a dramatic performance. Which is why it’s more difficult than drama — you don’t have so many tricks.

When your playing drama, and you’re in the moment, and you can nail the emotion that is called for, it just feels like a smooth thing. It’s so great. There is nothing like getting a laugh, though.

10 ENGLISH BOOKS RELATING TO «DRAMA»

Discover the use of drama in the following bibliographical selection. Books relating to drama and brief extracts from same to provide context of its use in English literature.

Raina Telgemeier, the NEW YORK TIMES bestselling author of the Eisner Award winner, SMILE, brings us her next full-color graphic novel . . . DRAMA! Callie loves theater.

2

Drama: A Guide to the Study of Plays

This book introduces the elements of drama and the principles behind the reading and study of plays — classical and modern.

3

Drama: Between Poetry and Performance

This book will appeal both to the professional and academic audience in drama and performance studies, as well as to a wider audience of theatregoers interested in the relationship between writing and performance.

4

Current Approaches in Drama Therapy

This second edition of Current Approaches in Drama Therapy offers a revised and updated comprehensive compilation of the primary drama therapy methods and models that are being utilized and taught in the United States and Canada, including …

David Read Johnson, Renee Emunah, 2009

5

Drama Ministry: Practical Help for Making Drama a Vital Part …

The CD-ROM included with this book provides a video demonstration of directing techniques. Whether you’re a drama director, part of a drama team, or a pastor interested in developing drama ministry in your church, this book is a must.

6

Modern Drama: Defining the Field

The contributors examine varied topics such as the analysis of periodicity; the articulation of social, political, and cultural production in theatre; the re-evaluation of texts, performances, and canons; and demonstrations of how …

Richard Paul Knowles, William B. Worthen, Joanne Tompkins, 2003

The expected Wagnerian voltage is here: in his thinking about myths such as Oedipus, his theories about operatic goals and musical possibilities, his contempt for musical politics, his exaltation of feeling and fantasy, his reflections …

8

The Drama of Scripture: Finding Our Place in the Biblical Story

Surveys the grand story line and theology of the Bible, demonstrating how the biblical story forms the foundation of a Christian worldview.

Craig G. Bartholomew, Michael W. Goheen, 2004

The writing of this book has afforded him pleasure in his leisure moments, and that pleasure would be much increased if he knew that the perusal of it would create any bond of sympathy between himself and the angling community in general.

10

Girls’ Life Guide to a Drama-Free Life

Presents a guide for girls on handling realtionships and social situations, including advice about school, friends, dating, body image, parents, siblings, and bullying.

Sarah Wassner Flynn, 2010

10 NEWS ITEMS WHICH INCLUDE THE TERM «DRAMA»

Find out what the national and international press are talking about and how the term drama is used in the context of the following news items.

A&E Picks Up 1990s L.A. Crime Drama ‘The Infamous’ To Pilot

A&E Network has picked up The Infamous, a hip-hop crime drama set in Los Angeles to be written and executive produced by Joshua Zetumer, … «Deadline, Jul 15»

Peter Moffat’s new BBC1 drama to star Sophie Okonedo and Adrian …

The casting makes the six-part drama a rarity in BBC1 primetime for having two black actors in the lead roles. It comes as the corporation … «The Guardian, Jul 15»

Howard Beck: ‘Unprecedented’ DeAndre Jordan Drama ‘A Bad Look …

The Los Angeles Clippers are lobbying to lure center DeAndre Jordan back and stop the star big man from signing with the Dallas Mavericks, … «Bleacher Report, Jul 15»

Buxton Fringe Festival: Ashrow Theatre return with wartime drama …

Buxton Fringe is an open arts festival with a variety of performances and displays including dance, drama, music, comedy, film, poetry and … «Derby Telegraph, Jul 15»

Rijiju row: Real drama behind Air India’s VIP woes and how it may …

The Minister of Civil Aviation has already offered an unconditional apology for Air India’s abominable conduct in preferring VIP passengers over … «Firstpost, Jul 15»

Dal Shabet’s Jiyul to star as lead in Korean-Chinese web drama series

Dal Shabet’s Jiyul has been cast for a role in upcoming web drama series called ‘Yotaek’ alongside actor Gao Yu, who is part of the Chinese … «allkpop, Jul 15»

The drama of reality TV

But what really happens behind the scenes? Enter UnReal. A scripted drama set behind-the-scenes of a fictitious, Bachelor-esque dating show, … «Sydney Morning Herald, Jul 15»

House narrowly votes to renew No Child Left Behind after drama

The House on Wednesday voted to reauthorize the No Child Left Behind law, resurrecting a bill that Republican leaders were forced to pull … «The Hill, Jul 15»

Editors Emmy slugfest: Which shows will get last two Drama Series …

But this year, the TV academy is expanding the field for Best Drama and Best Comedy to seven nominees – more if the 2% rule takes effect. «GoldDerby, Jul 15»

Statesman Editorial: Note to West Ada trustees: Downplay drama …

The last thing any school district needs is a fresh supply of manufactured drama, especially when there already is such a thin margin of error in … «The Idaho Statesman, Jul 15»

REFERENCE

« EDUCALINGO. Drama [online]. Available <https://educalingo.com/en/dic-en/drama>. Apr 2023 ».

Download the educalingo app

Discover all that is hidden in the words on

Other forms: dramas

Drama is highly emotional. It can happen on stage, like a performance of «Hamlet,» or in a gaggle of 7th grade girls, breathlessly dissecting why so-and-so broke up with what’s-her-name.

The word drama comes directly from Greek, meaning «action» or «a play.» Which is no surprise, since ancient Athens was a hotbed of dramatic theater. The earliest recorded actor was a Greek named Thespis, and actors today are still called «thespians» in his honor. Drama doesn’t always take place on the stage, though. You can use the word, sometimes with a roll of the eyes, to describe behavior or a reaction to a situation that appears a little overly emotional.

Definitions of drama

-

noun

a dramatic work intended for performance by actors on a stage

-

noun

the literary genre of works intended for the theater

see moresee less-

types:

- show 15 types…

- hide 15 types…

-

closet drama

drama more suitable for reading that for performing

-

comedy

light and humorous drama with a happy ending

-

tragedy

drama in which the protagonist is overcome by some superior force or circumstance; excites terror or pity

-

Kabuki, kabuki

a traditional form of Japanese drama characterized by highly stylized movement and song and using only male performers

-

black comedy

comedy that uses black humor

-

commedia dell’arte

Italian comedy of the 16th to 18th centuries improvised from standardized situations and stock characters

-

dark comedy

a comedy characterized by grim or satiric humor; a comedy having gloomy or disturbing elements

-

farce, farce comedy, travesty

a comedy characterized by broad satire and improbable situations

-

high comedy

a sophisticated comedy; often satirizing genteel society

-

low comedy

a comedy characterized by slapstick and burlesque

-

melodrama

an extravagant comedy in which action is more salient than characterization

-

seriocomedy, tragicomedy

a comedy with serious elements or overtones

-

tragicomedy

a dramatic composition involving elements of both tragedy and comedy usually with the tragic predominating

-

sitcom, situation comedy

a humorous drama based on situations that might arise in day-to-day life

-

slapstick

a boisterous comedy with chases and collisions and practical jokes

-

type of:

-

genre, literary genre, writing style

a style of expressing yourself in writing

-

noun

the quality of being arresting or highly emotional

-

noun

an episode that is turbulent or highly emotional

-

synonyms:

dramatic event

see moresee less-

types:

-

night terror

an emotional episode (usually in young children) in which the person awakens in terror with feelings of anxiety and fear but is unable to remember any incident that might have provoked those feelings

-

type of:

-

episode

a happening that is distinctive in a series of related events

-

night terror

DISCLAIMER: These example sentences appear in various news sources and books to reflect the usage of the word ‘drama’.

Views expressed in the examples do not represent the opinion of Vocabulary.com or its editors.

Send us feedback

EDITOR’S CHOICE

Look up drama for the last time

Close your vocabulary gaps with personalized learning that focuses on teaching the

words you need to know.

Sign up now (it’s free!)

Whether you’re a teacher or a learner, Vocabulary.com can put you or your class on the path to systematic vocabulary improvement.

Get started

| Literature |

|---|

| Major forms |

| Epic • Romance • Novel • Novella • Tragedy • Comedy • Drama • Folklore |

| Media |

| Play • Book |

| Techniques |

| Prose • Poetry |

| Discussion |

| Criticism • Theory |

The term drama comes from a Greek word meaning «action» (Classical Greek: δράμα, dráma), which is derived from «to do» (Classical Greek: δράω, dráō). The enactment of drama in theater, performed by actors on a stage before an audience, is a widely used art form that is found in virtually all cultures.

The two masks associated with drama represent the traditional generic division between comedy and tragedy. They are symbols of the ancient Greek Muses, Thalia and Melpomene. Thalia was the Muse of comedy (the laughing face), while Melpomene was the Muse of tragedy (the weeping face).

The use of «drama» in the narrow sense to designate a specific type of play dates from Nineteenth-century theatre. Drama in this sense refers to a play that is neither a comedy nor a tragedy, such as Émile Zola’s Thérèse Raquin (1873) or Anton Chekhov’s Ivanov (1887). It is this narrow sense that the film and television industry and film studies adopted to describe «drama» as a genre within their respective media.

Theories of drama date back to the work of the Ancient Greek philosophers. Plato, in a famous passage in «The Republic,» wrote that he would outlaw drama from his ideal state because the actor encouraged citizens to imitate their actions on stage. In his «Poetics,» Aristotle famously argued that tragedy leads to catharsis, allowing the viewer to purge unwanted emotional affect, and serving the greater social good.

History of Western drama

| History of Western theatre |

|---|

| Greek • Roman • Medieval • Commedia dell’arte • English Early Modern • Spanish Golden Age • Neoclassical • Restoration • Augustan • Weimar • Romanticism • Melodrama • Naturalism • Realism • Modernism • Postmodern 19th century • 20th century |

Classical Athenian drama

| Classical Athenian drama |

|---|

| Tragedy • Comedy • Satyr play Aeschylus • Sophocles • Euripides • Aristophanes • Menander |

Western drama originates in classical Greece. The theatrical culture of the city-state of Athens produced three genres of drama: tragedy, comedy, and the satyr play. Their origins remain obscure, though by the fifth century B.C.E. they were institutionalized in competitions held as part of festivities celebrating the god Dionysus.[1] Historians know the names of many ancient Greek dramatists, not least Thespis, who is credited with the innovation of an actor («hypokrites«) who speaks (rather than sings) and impersonates a character (rather than speaking in his own person), while interacting with the chorus and its leader («coryphaeus«), who were a traditional part of the performance of non-dramatic poetry (dithyrambic, lyric and epic).[2] Only a small fraction of the work of five dramatists, however, has survived to this day: we have a small number of complete texts by the tragedians Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, and the comic writers Aristophanes and, from the late fourth century, Menander.[3] Aeschylus’ historical tragedy The Persians is the oldest surviving drama, although when it won first prize at the City Dionysia competition in 472 B.C.E., he had been writing plays for more than 25 years.[4] The competition («agon«) for tragedies may have begun as early as 534 B.C.E.; official records («didaskaliai«) begin from 501 B.C.E., when the satyr play was introduced.[5] Tragic dramatists were required to present a tetralogy of plays (though the individual works were not necessarily connected by story or theme), which usually consisted of three tragedies and one satyr play (though exceptions were made, as with Euripides’ Alcestis in 438 B.C.E.). Comedy was officially recognized with a prize in the competition from 487-486 B.C.E. Five comic dramatists competed at the City Dionysia (though during the Peloponnesian War this may have been reduced to three), each offering a single comedy.[6] Ancient Greek comedy is traditionally divided between «old comedy» (5th century B.C.E.), «middle comedy» (fourth century B.C.E.) and «new comedy» (late fourth century to second B.C.E.).[7]

The Tenants of Classicism

The expression classicism as it applies to drama implies notions of order, clarity, moral purpose and good taste. Many of these notions are directly inspired by the works of Aristotle and Horace and by classical Greek and Roman masterpieces.

According to the tenants of classicism, a play should follow the Three Unities:

- Unity of place : the setting should not change. In practice, this lead to the frequent «Castle, interior.» Battles take place off stage.

- Unity of time: ideally the entire play should take place in 24 hours.

- Unity of action: there should be one central story and all secondary plots should be linked to it.

Although based on classical examples, the unities of place and time were seen as essential for the spectator’s complete absorption into the dramatic action; wildly dispersed settings or the break in time was considered detrimental to creating the theatrical illusion. Sometimes grouped with the unity of action is the notion that no character should appear unexpectedly late in the drama.

Roman drama

Following the expansion of the Roman Republic (509-27 B.C.E.) into several Greek territories between 270-240 B.C.E., Rome encountered Greek drama.[8] From the later years of the republic and by means of the Roman Empire (27 B.C.E.-476 C.E.), theater spread west across Europe, around the Mediterranean and reached England; Roman theater was more varied, extensive and sophisticated than that of any culture before it.[9] While Greek drama continued to be performed throughout the Roman period, the year 240 B.C.E. marks the beginning of regular Roman drama.[10] From the beginning of the empire, however, interest in full-length drama declined in favor of a broader variety of theatrical entertainments.[11] The first important works of Roman literature were the tragedies and comedies that Livius Andronicus wrote from 240 B.C.E.[12] Five years later, Gnaeus Naevius also began to write drama.[12] No plays from either writer have survived. While both dramatists composed in both genres, Andronicus was most appreciated for his tragedies and Naevius for his comedies; their successors tended to specialize in one or the other, which led to a separation of the subsequent development of each type of drama.[12] By the beginning of the second century B.C.E., drama was firmly established in Rome and a guild of writers (collegium poetarum) had been formed.[13] The Roman comedies that have survived are all fabula palliata (comedies based on Greek subjects) and come from two dramatists: Titus Maccius Plautus (Plautus) and Publius Terentius Afer (Terence).[14] In re-working the Greek originals, the Roman comic dramatists abolished the role of the chorus in dividing the drama into episodes and introduced musical accompaniment to its dialogue (between one-third of the dialogue in the comedies of Plautus and two-thirds in those of Terence).[15] The action of all scenes is set in the exterior location of a street and its complications often follow from eavesdropping.[15] Plautus, the more popular of the two, wrote between 205-184 B.C.E. and 20 of his comedies survive, of which his farces are best known; he was admired for the wit of his dialogue and his use of a variety of poetic meters.[16] All of the six comedies that Terence wrote between 166-160 B.C.E. have survived; the complexity of his plots, in which he often combined several Greek originals, was sometimes denounced, but his double-plots enabled a sophisticated presentation of contrasting human behavior.[16] No early Roman tragedy survives, though it was highly-regarded in its day; historians know of three early tragedians—Quintus Ennius, Marcus Pacuvius and Lucius Accius.[15] From the time of the empire, the work of two tragedians survives—one is an unknown author, while the other is the Stoic philosopher Seneca.[17] Nine of Seneca’s tragedies survive, all of which are fabula crepidata (tragedies adapted from Greek originals); his Phaedra, for example, was based on Euripides’ Hippolytus.[18] Historians do not know who wrote the only extant example of the fabula praetexta (tragedies based on Roman subjects), Octavia, but in former times it was mistakenly attributed to Seneca due to his appearance as a character in the tragedy.[17]

Medieval and Renaissance drama

In the Middle Ages, drama in the vernacular languages of Europe may have emerged from religious enactments of the liturgy. Mystery plays were presented on the porch of the cathedrals or by strolling players on feast days.

Renaissance theater derived from several medieval theater traditions, such as the mystery plays that formed a part of religious festivals in England and other parts of Europe during the Middle Ages. The mystery plays were complex retellings of legends based on biblical themes, originally performed in churches but later becoming more linked to the secular celebrations that grew up around religious festivals. Other sources include the morality plays that evolved out of the mysteries, and the «University drama» that attempted to recreate Greek tragedy. The Italian tradition of Commedia dell’arte as well as the elaborate masques frequently presented at court came to play roles in the shaping of public theater. Miracle and mystery plays, along with moralities and interludes, later evolved into more elaborate forms of drama, such as was seen on the Elizabethan stages.

Elizabethan and Jacobean

One of the great flowerings of drama in England occurred in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Many of these plays were written in verse, particularly iambic pentameter. In addition to Shakespeare, such authors as Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Middleton, and Ben Jonson were prominent playwrights during this period. As in the medieval period, historical plays celebrated the lives of past kings, enhancing the image of the Tudor monarchy. Authors of this period drew some of their storylines from Greek mythology and Roman mythology or from the plays of eminent Roman playwrights such as Plautus and Terence.

William Shakespeare

Shakespeare’s plays are considered by many to be the pinnacle of the dramatic arts. His early plays were mainly comedies and histories, genres he raised to the peak of sophistication by the end of the sixteenth century. In his following phase he wrote mainly tragedies, including Hamlet, King Lear, Macbeth, and Othello. The plays are often regarded as the summit of Shakespeare’s art and among the greatest tragedies ever written. In 1623, two of his former theatrical colleagues published the First Folio, a collected edition of his dramatic works that included all but two of the plays now recognized as Shakespeare’s.

Shakespeare’s canon has achieved a unique standing in Western literature, amounting to a humanistic scripture. His insight in human character and motivation and his luminous, boundary-defying diction have influenced writers for centuries. Some of the more notable authors and poets so influenced are Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, Charles Dickens, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Herman Melville, and William Faulkner. According to Harold Bloom, Shakespeare «has been universally judged to be a more adequate representer of the universe of fact than anyone else, before or since.»[19]

Seventeenth century French Neo-classicism

While the Puritans were shutting down theaters in England, one of the greatest flowerings of drama was taking place in France. By the 1660s, neo-classicism had emerged as the dominant trend in French theater. French neo-classicism represented an updated version of Greek and Roman classical theater. The key theoretical work on theater from this period was François Hedelin, abbé d’Aubignac’s «Pratique du théâtre» (1657), and the dictates of this work reveal to what degree «French classicism» was willing to modify the rules of classical tragedy to maintain the unities and decorum (d’Aubignac for example saw the tragedies of Oedipus and Antigone as unsuitable for the contemporary stage).

Although Pierre Corneille continued to produce tragedies to the end of his life, the works of Jean Racine from the late 1660s on totally eclipsed the late plays of the elder dramatist. Racine’s tragedies—inspired by Greek myths, Euripides, Sophocles and Seneca—condensed their plot into a tight set of passionate and duty-bound conflicts between a small group of noble characters, and concentrated on these characters’ conflicts and the geometry of their unfulfilled desires and hatreds. Racine’s poetic skill was in the representation of pathos and amorous passion (like Phèdre’s love for her stepson) and his impact was such that emotional crisis would be the dominant mode of tragedy to the end of the century. Racine’s two late plays («Esther» and «Athalie») opened new doors to biblical subject matter and to the use of theater in the education of young women.

Tragedy in the last two decades of the century and the first years of the eighteenth century was dominated by productions of classics from Pierre Corneille and Racine, but on the whole the public’s enthusiasm for tragedy had greatly diminished: theatrical tragedy paled beside the dark economic and demographic problems at the end of the century and the «comedy of manners» (see below) had incorporated many of the moral goals of tragedy. Other later century tragedians include: Claude Boyer, Michel Le Clerc, Jacques Pradon, Jean Galbert de Campistron, Jean de la Chapelle, Antoine d’Aubigny de la Fosse, l’abbé Charles-Claude Geneste, Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon.