|

|

|

| Area | 30,370,000 km2 (11,730,000 sq mi) (2nd) |

|---|---|

| Population | 1,393,676,444[1][2] (2021; 2nd) |

| Population density | 46.1/km2 (119.4/sq mi) (2021) |

| GDP (PPP) | $8.05 trillion (2022 est; 4th)[3] |

| GDP (nominal) | $2.96 trillion (2022 est; 5th)[4] |

| GDP per capita | $2,180 (Nominal; 2022 est; 6th)[5] |

| Religions |

|

| Demonym | African |

| Countries | 54+2*+5** (*disputed) (**territories) |

| Dependencies |

External (5)

Internal (6+1 disputed)

|

| Languages | 1250–3000 native languages |

| Time zones | UTC-1 to UTC+4 |

| Largest cities | Largest urban areas:

|

The size of Africa compared to the other continents

Africa is the world’s second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both aspects. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth’s land area and 6% of its total surface area.[7] With 1.4 billion people[1][2] as of 2021, it accounts for about 18% of the world’s human population. Africa’s population is the youngest amongst all the continents;[8][9] the median age in 2012 was 19.7, when the worldwide median age was 30.4.[10] Despite a wide range of natural resources, Africa is the least wealthy continent per capita and second-least wealthy by total wealth, behind Oceania. Scholars have attributed this to different factors including geography, climate, tribalism,[11] colonialism, the Cold War,[12][13] neocolonialism, lack of democracy, and corruption.[11] Despite this low concentration of wealth, recent economic expansion and the large and young population make Africa an important economic market in the broader global context.

The continent is surrounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, the Isthmus of Suez and the Red Sea to the northeast, the Indian Ocean to the southeast and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. The continent includes Madagascar and various archipelagos. It contains 54 fully recognised sovereign states, eight territories and two de facto independent states with limited or no recognition. Algeria is Africa’s largest country by area, and Nigeria is its largest by population. African nations cooperate through the establishment of the African Union, which is headquartered in Addis Ababa.

Africa straddles the equator and the prime meridian. It is the only continent to stretch from the northern temperate to the southern temperate zones.[14] The majority of the continent and its countries are in the Northern Hemisphere, with a substantial portion and number of countries in the Southern Hemisphere. Most of the continent lies in the tropics, except for a large part of Western Sahara, Algeria, Libya and Egypt, the northern tip of Mauritania, and the entire territories of Morocco, Ceuta, Melilla, and Tunisia which in turn are located above the tropic of Cancer, in the northern temperate zone. In the other extreme of the continent, southern Namibia, southern Botswana, great parts of South Africa, the entire territories of Lesotho and Eswatini and the southern tips of Mozambique and Madagascar are located below the tropic of Capricorn, in the southern temperate zone.

Africa is highly biodiverse; it is the continent with the largest number of megafauna species, as it was least affected by the extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna. However, Africa also is heavily affected by a wide range of environmental issues, including desertification, deforestation, water scarcity and pollution. These entrenched environmental concerns are expected to worsen as climate change impacts Africa. The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has identified Africa as the continent most vulnerable to climate change.[15][16]

The history of Africa is long, complex, and has often been under-appreciated by the global historical community.[17] Africa, particularly Eastern Africa, is widely accepted as the place of origin of humans and the Hominidae clade (great apes). The earliest hominids and their ancestors have been dated to around 7 million years ago, including Sahelanthropus tchadensis, Australopithecus africanus, A. afarensis, Homo erectus, H. habilis and H. ergaster—the earliest Homo sapiens (modern human) remains, found in Ethiopia, South Africa, and Morocco, date to circa 233,000, 259,000, and 300,000 years ago respectively, and Homo sapiens is believed to have originated in Africa around 350,000–260,000 years ago.[a] Africa is also considered by anthropologists to be the most genetically diverse continent as a result of being the longest inhabited.[24][25][26]

Early human civilizations, such as Ancient Egypt and Carthage emerged in North Africa. Following a subsequent long and complex history of civilizations, migration and trade, Africa hosts a large diversity of ethnicities, cultures and languages. The last 400 years have witnessed an increasing European influence on the continent. Starting in the 16th century, this was driven by trade, including the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, which created large African diaspora populations in the Americas. From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, European nations colonized almost all of Africa, reaching a point when only Ethiopia and Liberia were independent polities.[27] Most present states in Africa emerged from a process of decolonisation following World War II.

Etymology

The totality of Africa seen by the Apollo 17 crew

Afri was a Latin name used to refer to the inhabitants of then-known northern Africa to the west of the Nile river, and in its widest sense referred to all lands south of the Mediterranean (Ancient Libya).[28][29] This name seems to have originally referred to a native Libyan tribe, an ancestor of modern Berbers; see Terence for discussion. The name had usually been connected with the Phoenician word ʿafar meaning «dust»,[30] but a 1981 hypothesis[31] has asserted that it stems from the Berber word ifri (plural ifran) meaning «cave», in reference to cave dwellers.[32] The same word[32] may be found in the name of the Banu Ifran from Algeria and Tripolitania, a Berber tribe originally from Yafran (also known as Ifrane) in northwestern Libya,[33] as well as the city of Ifrane in Morocco.

Under Roman rule, Carthage became the capital of the province it then named Africa Proconsularis, following its defeat of the Carthaginians in the Third Punic War in 146 BCE, which also included the coastal part of modern Libya.[34] The Latin suffix -ica can sometimes be used to denote a land (e.g., in Celtica from Celtae, as used by Julius Caesar). The later Muslim region of Ifriqiya, following its conquest of the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire’s Exarchatus Africae, also preserved a form of the name.

According to the Romans, Africa lies to the west of Egypt, while «Asia» was used to refer to Anatolia and lands to the east. A definite line was drawn between the two continents by the geographer Ptolemy (85–165 CE), indicating Alexandria along the Prime Meridian and making the isthmus of Suez and the Red Sea the boundary between Asia and Africa. As Europeans came to understand the real extent of the continent, the idea of «Africa» expanded with their knowledge.

Other etymological hypotheses have been postulated for the ancient name «Africa»:

- The 1st-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (Ant. 1.15) asserted that it was named for Epher, grandson of Abraham according to Gen. 25:4, whose descendants, he claimed, had invaded Libya.

- Isidore of Seville in his 7th-century Etymologiae XIV.5.2. suggests «Africa comes from the Latin aprica, meaning «sunny».

- Massey, in 1881, stated that Africa is derived from the Egyptian af-rui-ka, meaning «to turn toward the opening of the Ka.» The Ka is the energetic double of every person and the «opening of the Ka» refers to a womb or birthplace. Africa would be, for the Egyptians, «the birthplace.»[35]

- Michèle Fruyt in 1976 proposed[36] linking the Latin word with africus «south wind», which would be of Umbrian origin and mean originally «rainy wind».

- Robert R. Stieglitz of Rutgers University in 1984 proposed: «The name Africa, derived from the Latin *Aphir-ic-a, is cognate to Hebrew Ophir [‘rich’].»[37]

- Ibn Khallikan and some other historians claim that the name of Africa came from a Himyarite king called Afrikin ibn Kais ibn Saifi also called «Afrikus son of Abraham» who subdued Ifriqiya.[38][39][40]

- Arabic afrīqā (feminine noun) and ifrīqiyā, now usually pronounced afrīqiyā (feminine) ‘Africa’, from ‘afara [‘ = ‘ain, not ’alif] ‘to be dusty’ from ‘afar ‘dust, powder’ and ‘afir ‘dried, dried up by the sun, withered’ and ‘affara ‘to dry in the sun on hot sand’ or ‘to sprinkle with dust’.[41]

- Possibly Phoenician faraqa in the sense of ‘colony, separation’.[42]

History

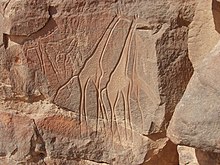

Prehistory

Africa is considered by most paleoanthropologists to be the oldest inhabited territory on Earth, with the Human species originating from the continent.[43] During the mid-20th century, anthropologists discovered many fossils and evidence of human occupation perhaps as early as 7 million years ago (BP=before present). Fossil remains of several species of early apelike humans thought to have evolved into modern man, such as Australopithecus afarensis radiometrically dated to approximately 3.9–3.0 million years BP,[44] Paranthropus boisei (c. 2.3–1.4 million years BP)[45] and Homo ergaster (c. 1.9 million–600,000 years BP) have been discovered.[7]

After the evolution of Homo sapiens approximately 350,000 to 260,000 years BP in Africa,[19][20][21][22] the continent was mainly populated by groups of hunter-gatherers.[46][47] These first modern humans left Africa and populated the rest of the globe during the Out of Africa II migration dated to approximately 50,000 years BP, exiting the continent either across Bab-el-Mandeb over the Red Sea,[48][49] the Strait of Gibraltar in Morocco,[50][51] or the Isthmus of Suez in Egypt.[52]

Other migrations of modern humans within the African continent have been dated to that time, with evidence of early human settlement found in Southern Africa, Southeast Africa, North Africa, and the Sahara.[53]

Emergence of civilization

The size of the Sahara has historically been extremely variable, with its area rapidly fluctuating and at times disappearing depending on global climatic conditions.[54] At the end of the Ice ages, estimated to have been around 10,500 BCE, the Sahara had again become a green fertile valley, and its African populations returned from the interior and coastal highlands in sub-Saharan Africa, with rock art paintings depicting a fertile Sahara and large populations discovered in Tassili n’Ajjer dating back perhaps 10 millennia.[55] However, the warming and drying climate meant that by 5000 BCE, the Sahara region was becoming increasingly dry and hostile. Around 3500 BCE, due to a tilt in the earth’s orbit, the Sahara experienced a period of rapid desertification.[56] The population trekked out of the Sahara region towards the Nile Valley below the Second Cataract where they made permanent or semi-permanent settlements. A major climatic recession occurred, lessening the heavy and persistent rains in Central and Eastern Africa. Since this time, dry conditions have prevailed in Eastern Africa and, increasingly during the last 200 years, in Ethiopia.

The domestication of cattle in Africa preceded agriculture and seems to have existed alongside hunter-gatherer cultures. It is speculated that by 6000 BCE, cattle were domesticated in North Africa.[57] In the Sahara-Nile complex, people domesticated many animals, including the donkey and a small screw-horned goat which was common from Algeria to Nubia.

Between 10,000 and 9,000 BCE, pottery was independently invented in the region of Mali in the savannah of West Africa.[58][59]

In the steppes and savannahs of the Sahara and Sahel in Northern West Africa, people possibly ancestral to modern Nilo-Saharan and Mandé cultures started to collect wild millet,[60] around 8000 to 6000 BCE. Later, gourds, watermelons, castor beans, and cotton were also collected.[61] Sorghum was first domesticated in Eastern Sudan around 4000 BCE, in one of the earliest instances of agriculture in human history. Its cultivation would gradually spread across Africa, before spreading to India around 2000 BCE.[62]

Sorghum was first domesticated in the[clarification needed]. They also started making pottery and built stone settlements (e.g., Tichitt, Oualata). Fishing, using bone-tipped harpoons, became a major activity in the numerous streams and lakes formed from the increased rains.[63] In West Africa, the wet phase ushered in an expanding rainforest and wooded savanna from Senegal to Cameroon. Between 9,000 and 5,000 BCE, Niger–Congo speakers domesticated the oil palm and raffia palm. Black-eyed peas and voandzeia (African groundnuts), were domesticated, followed by okra and kola nuts. Since most of the plants grew in the forest, the Niger–Congo speakers invented polished stone axes for clearing forest.[64]

Around 4000 BCE, the Saharan climate started to become drier at an exceedingly fast pace.[65] This climate change caused lakes and rivers to shrink significantly and caused increasing desertification. This, in turn, decreased the amount of land conducive to settlements and encouraged migrations of farming communities to the more tropical climate of West Africa.[65] During the first millennium BCE, a reduction in wild grain populations related to changing climate conditions facilitated the expansion of farming communities and the rapid adoption of rice cultivation around the Niger River.[66][67]

By the first millennium BCE, ironworking had been introduced in Northern Africa. Around that time it also became established in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, either through independent invention there or diffusion from the north[68][69] and vanished under unknown circumstances around 500 CE, having lasted approximately 2,000 years,[70] and by 500 BCE, metalworking began to become commonplace in West Africa. Ironworking was fully established by roughly 500 BCE in many areas of East and West Africa, although other regions didn’t begin ironworking until the early centuries CE. Copper objects from Egypt, North Africa, Nubia, and Ethiopia dating from around 500 BCE have been excavated in West Africa, suggesting that Trans-Saharan trade networks had been established by this date.[65]

Early civilizations

At about 3300 BCE, the historical record opens in Northern Africa with the rise of literacy in the Pharaonic civilization of ancient Egypt.[71] One of the world’s earliest and longest-lasting civilizations, the Egyptian state continued, with varying levels of influence over other areas, until 343 BCE.[72][73] Egyptian influence reached deep into modern-day Libya and Nubia, and, according to Martin Bernal, as far north as Crete.[74]

An independent centre of civilization with trading links to Phoenicia was established by Phoenicians from Tyre on the north-west African coast at Carthage.[75][76][77]

European exploration of Africa began with the ancient Greeks and Romans.[78][79] In 332 BCE, Alexander the Great was welcomed as a liberator in Persian-occupied Egypt. He founded Alexandria in Egypt, which would become the prosperous capital of the Ptolemaic dynasty after his death.[80]

The Ezana Stone records King Ezana’s conversion to Christianity and his subjugation of various neighboring peoples, including Meroë.

Following the conquest of North Africa’s Mediterranean coastline by the Roman Empire, the area was integrated economically and culturally into the Roman system. Roman settlement occurred in modern Tunisia and elsewhere along the coast. The first Roman emperor native to North Africa was Septimius Severus, born in Leptis Magna in present-day Libya—his mother was Italian Roman and his father was Punic.[81]

Christianity spread across these areas at an early date, from Judaea via Egypt and beyond the borders of the Roman world into Nubia;[82] by 340 CE at the latest, it had become the state religion of the Aksumite Empire. Syro-Greek missionaries, who arrived by way of the Red Sea, were responsible for this theological development.[83]

In the early 7th century, the newly formed Arabian Islamic Caliphate expanded into Egypt, and then into North Africa. In a short while, the local Berber elite had been integrated into Muslim Arab tribes. When the Umayyad capital Damascus fell in the 8th century, the Islamic centre of the Mediterranean shifted from Syria to Qayrawan in North Africa. Islamic North Africa had become diverse, and a hub for mystics, scholars, jurists, and philosophers. During the above-mentioned period, Islam spread to sub-Saharan Africa, mainly through trade routes and migration.[84]

In West Africa, Dhar Tichitt and Oualata in present-day Mauritania figure prominently among the early urban centers, dated to 2,000 BCE. About 500 stone settlements litter the region in the former savannah of the Sahara. Its inhabitants fished and grew millet. It has been found by Augustin Holl that the Soninke of the Mandé peoples were likely responsible for constructing such settlements. Around 300 BCE, the region became more desiccated and the settlements began to decline, most likely relocating to Koumbi Saleh.[85] Architectural evidence and the comparison of pottery styles suggest that Dhar Tichitt was related to the subsequent Ghana Empire. Djenné-Djenno (in present-day Mali) was settled around 300 BCE, and the town grew to house a sizable Iron Age population, as evidenced by crowded cemeteries. Living structures were made of sun-dried mud. By 250 BCE, Djenné-Djenno had become a large, thriving market town.[86][87]

Farther south, in central Nigeria, around 1,500 BCE, the Nok culture developed on the Jos Plateau. It was a highly centralized community. The Nok people produced lifelike representations in terracotta, including human heads and human figures, elephants, and other animals. By 500 BCE, and possibly earlier, they were smelting iron. By 200 CE, the Nok culture had vanished.[69] and vanished under unknown circumstances around 500 CE, having lasted approximately 2,000 years. Based on stylistic similarities with the Nok terracottas, the bronze figurines of the Yoruba kingdom of Ife and those of the Bini kingdom of Benin are suggested to be continuations of the traditions of the earlier Nok culture.[88][70]

Ninth to eighteenth centuries

The intricate 9th-century bronzes from Igbo-Ukwu, in Nigeria displayed a level of technical accomplishment that was notably more advanced than European bronze casting of the same period.[89]

Pre-colonial Africa possessed perhaps as many as 10,000 different states and polities[90] characterized by many different sorts of political organization and rule. These included small family groups of hunter-gatherers such as the San people of southern Africa; larger, more structured groups such as the family clan groupings of the Bantu-speaking peoples of central, southern, and eastern Africa; heavily structured clan groups in the Horn of Africa; the large Sahelian kingdoms; and autonomous city-states and kingdoms such as those of the Akan; Edo, Yoruba, and Igbo people in West Africa; and the Swahili coastal trading towns of Southeast Africa.

By the ninth century CE, a string of dynastic states, including the earliest Hausa states, stretched across the sub-Saharan savannah from the western regions to central Sudan. The most powerful of these states were Ghana, Gao, and the Kanem-Bornu Empire. Ghana declined in the eleventh century, but was succeeded by the Mali Empire which consolidated much of western Sudan in the thirteenth century. Kanem accepted Islam in the eleventh century.

In the forested regions of the West African coast, independent kingdoms grew with little influence from the Muslim north. The Kingdom of Nri was established around the ninth century and was one of the first. It is also one of the oldest kingdoms in present-day Nigeria and was ruled by the Eze Nri. The Nri kingdom is famous for its elaborate bronzes, found at the town of Igbo-Ukwu. The bronzes have been dated from as far back as the ninth century.[91]

The Kingdom of Ife, historically the first of these Yoruba city-states or kingdoms, established government under a priestly oba (‘king’ or ‘ruler’ in the Yoruba language), called the Ooni of Ife. Ife was noted as a major religious and cultural centre in West Africa, and for its unique naturalistic tradition of bronze sculpture. The Ife model of government was adapted at the Oyo Empire, where its obas or kings, called the Alaafins of Oyo, once controlled a large number of other Yoruba and non-Yoruba city-states and kingdoms; the Fon Kingdom of Dahomey was one of the non-Yoruba domains under Oyo control.

The Almoravids were a Berber dynasty from the Sahara that spread over a wide area of northwestern Africa and the Iberian peninsula during the eleventh century.[92] The Banu Hilal and Banu Ma’qil were a collection of Arab Bedouin tribes from the Arabian Peninsula who migrated westwards via Egypt between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries. Their migration resulted in the fusion of the Arabs and Berbers, where the locals were Arabized,[93] and Arab culture absorbed elements of the local culture, under the unifying framework of Islam.[94]

Following the breakup of Mali, a local leader named Sonni Ali (1464–1492) founded the Songhai Empire in the region of middle Niger and the western Sudan and took control of the trans-Saharan trade. Sonni Ali seized Timbuktu in 1468 and Jenne in 1473, building his regime on trade revenues and the cooperation of Muslim merchants. His successor Askia Mohammad I (1493–1528) made Islam the official religion, built mosques, and brought to Gao Muslim scholars, including al-Maghili (d.1504), the founder of an important tradition of Sudanic African Muslim scholarship.[95] By the eleventh century, some Hausa states – such as Kano, jigawa, Katsina, and Gobir – had developed into walled towns engaging in trade, servicing caravans, and the manufacture of goods. Until the fifteenth century, these small states were on the periphery of the major Sudanic empires of the era, paying tribute to Songhai to the west and Kanem-Borno to the east.

Height of the slave trade

Major slave trading regions of Africa, 15th–19th centuries.

Slavery had long been practiced in Africa.[96][97] Between the 15th and the 19th centuries, the Atlantic slave trade took an estimated 7–12 million slaves to the New World.[98][99][100] In addition, more than 1 million Europeans were captured by Barbary pirates and sold as slaves in North Africa between the 16th and 19th centuries.[101]

In West Africa, the decline of the Atlantic slave trade in the 1820s caused dramatic economic shifts in local polities. The gradual decline of slave-trading, prompted by a lack of demand for slaves in the New World, increasing anti-slavery legislation in Europe and America, and the British Royal Navy’s increasing presence off the West African coast, obliged African states to adopt new economies. Between 1808 and 1860, the British West Africa Squadron seized approximately 1,600 slave ships and freed 150,000 Africans who were aboard.[102]

Action was also taken against African leaders who refused to agree to British treaties to outlaw the trade, for example against «the usurping King of Lagos», deposed in 1851. Anti-slavery treaties were signed with over 50 African rulers.[103] The largest powers of West Africa (the Asante Confederacy, the Kingdom of Dahomey, and the Oyo Empire) adopted different ways of adapting to the shift. Asante and Dahomey concentrated on the development of «legitimate commerce» in the form of palm oil, cocoa, timber and gold, forming the bedrock of West Africa’s modern export trade. The Oyo Empire, unable to adapt, collapsed into civil wars.[104]

Colonialism

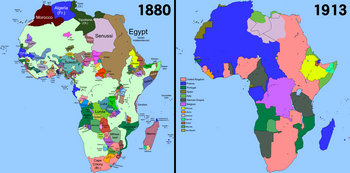

Comparison of Africa in the years 1880 and 1913

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, the Conquest of Africa or the Rape of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonization of most of Africa by seven Western European powers during an era known as New Imperialism (between 1833 and 1914). The 10 percent of Africa that was under formal European control in 1870 increased to almost 90 percent by 1914, with only Liberia and Ethiopia remaining independent.[105]

The Berlin Conference of 1884, which regulated European colonization and trade in Africa, is usually accepted as the beginning.[106] In the last quarter of the 19th century, there were considerable political rivalries between the European empires, which provided the impetus for the Scramble.[107] The later years of the 19th century saw a transition from «informal imperialism» – military influence and economic dominance – to direct rule.[108]

Most of Africa was decolonised during the Cold War. The imperial boundaries and economic systems imposed by the Scramble still affect the politics and economy of Africa today.[109]

Independence struggles

Imperial rule by Europeans would continue until after the conclusion of World War II, when almost all remaining colonial territories gradually obtained formal independence. Independence movements in Africa gained momentum following World War II, which left the major European powers weakened. In 1951, Libya, a former Italian colony, gained independence. In 1956, Tunisia and Morocco won their independence from France.[110] Ghana followed suit the next year (March 1957),[111] becoming the first of the sub-Saharan colonies to be granted independence. Most of the rest of the continent became independent over the next decade.

Portugal’s overseas presence in sub-Saharan Africa (most notably in Angola, Cape Verde, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, and São Tomé and Príncipe) lasted from the 16th century to 1975, after the Estado Novo regime was overthrown in a military coup in Lisbon. Rhodesia unilaterally declared independence from the United Kingdom in 1965, under the white minority government of Ian Smith, but was not internationally recognized as an independent state (as Zimbabwe) until 1980, when black nationalists gained power after a bitter guerrilla war. Although South Africa was one of the first African countries to gain independence, the state remained under the control of the country’s white minority through a system of racial segregation known as apartheid until 1994.

Post-colonial Africa

Today, Africa contains 54 sovereign countries, most of which have borders that were drawn during the era of European colonialism. Since independence, African states have frequently been hampered by instability, corruption, violence, and authoritarianism. The vast majority of African states are republics that operate under some form of the presidential system of rule. However, few of them have been able to sustain democratic governments on a permanent basis—per the criteria laid out by Lührmann et al. (2018), only Botswana and Mauritius have been consistently democratic for the entirety of their post-colonial history. Most African countries have experienced several coups or periods of military dictatorship. Between 1990 and 2018, though, the continent as a whole has trended towards more democratic governance.[112]

Upon independence an overwhelming majority of Africans lived in extreme poverty. The continent suffered from the lack of infrastructural or industrial development under colonial rule, along with political instability. With limited financial resources or access to global markets, relatively stable countries such as Kenya still experienced only very slow economic development. Only a handful of African countries succeeded in obtaining rapid economic growth prior to 1990. Exceptions include Libya and Equatorial Guinea, both of which possess large oil reserves.

Instability throughout the continent after decolonization resulted primarily from marginalization of ethnic groups, and corruption. In pursuit of personal political gain, many leaders deliberately promoted ethnic conflicts, some of which had originated during the colonial period, such as from the grouping of multiple unrelated ethnic groups into a single colony, the splitting of a distinct ethnic group between multiple colonies, or existing conflicts being exacerbated by colonial rule (for instance, the preferential treatment given to ethnic Hutus over Tutsis in Rwanda during German and Belgian rule).

Faced with increasingly frequent and severe violence, military rule was widely accepted by the population of many countries as means to maintain order, and during the 1970s and 1980s a majority of African countries were controlled by military dictatorships. Territorial disputes between nations and rebellions by groups seeking independence were also common in independent African states. The most devastating of these was the Nigerian Civil War, fought between government forces and an Igbo separatist republic, which resulted in a famine that killed 1–2 million people. Two civil wars in Sudan, the first lasting from 1955 to 1972 and the second from 1983 to 2005, collectively killed around 3 million. Both were fought primarily on ethnic and religious lines.

Cold War conflicts between the United States and the Soviet Union also contributed to instability. Both the Soviet Union and the United States offered considerable incentives to African political and military leaders who aligned themselves with the superpowers’ foreign policy. As an example, during the Angolan Civil War, the Soviet and Cuban aligned MPLA and the American aligned UNITA received the vast majority of their military and political support from these countries. Many African countries became highly dependent on foreign aid. The sudden loss of both Soviet and American aid at the end of the Cold War and fall of the USSR resulted in severe economic and political turmoil in the countries most dependent on foreign support.

There was a major famine in Ethiopia between 1983 and 1985, killing up to 1.2 million people, which most historians attribute primarily to the forced relocation of farmworkers and seizure of grain by communist Derg government, further exacerbated by the civil war.[113][114][115][116] In 1994 a genocide in Rwanda resulted in up to 800,000 deaths, added to a severe refugee crisis and fueled the rise of militia groups in neighboring countries. This contributed to the outbreak of the first and second Congo Wars, which were the most devastating military conflicts in modern Africa, with up to 5.5 million deaths,[117] making it by far the deadliest conflict in modern African history and one of the costliest wars in human history.[118]

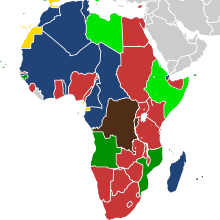

-

Africa’s wars and conflicts, 1980–96

Major Wars/Conflict (>100,000 casualties)

Minor Wars/Conflict

Other Conflicts

-

Political map of Africa in 2021

Various conflicts between various insurgent groups and governments continue. Since 2003 there has been an ongoing conflict in Darfur (Sudan) which peaked in intensity from 2003 to 2005 with notable spikes in violence in 2007 and 2013–15, killing around 300,000 people total. The Boko Haram Insurgency primarily within Nigeria (with considerable fighting in Niger, Chad, and Cameroon as well) has killed around 350,000 people since 2009. Most African conflicts have been reduced to low-intensity conflicts as of 2022. However, the Tigray War which began in 2020 has killed an estimated 300,000–500,000 people, primarily due to famine.

Overall though, violence across Africa has greatly declined in the 21st century, with the end of civil wars in Angola, Sierra Leone, and Algeria in 2002, Liberia in 2003, and Sudan and Burundi in 2005. The Second Congo War, which involved 9 countries and several insurgent groups, ended in 2003. This decline in violence coincided with many countries abandoning communist-style command economies and opening up for market reforms, which over the course of the 1990s and 2000s promoted the establishment of permanent, peaceful trade between neighboring countries (see Capitalist peace).

Improved stability and economic reforms have led to a great increase in foreign investment into many African nations, mainly from China,[119] which further spurred economic growth. Between 2000 and 2014, annual GDP growth in sub-Saharan Africa averaged 5.02%, doubling its total GDP from $811 Billion to $1.63 Trillion (Constant 2015 USD).[120] North Africa experienced comparable growth rates.[121] A significant part of this growth can also be attributed to the facilitated diffusion of information technologies and specifically the mobile telephone.[122] While several individual countries have maintained high growth rates, since 2014 overall growth has considerably slowed, primarily as a result of falling commodity prices, continued lack of industrialization, and epidemics of Ebola and COVID-19.[123][124]

Geology, geography, ecology, and environment

Africa is the largest of the three great southward projections from the largest landmass of the Earth. Separated from Europe by the Mediterranean Sea, it is joined to Asia at its northeast extremity by the Isthmus of Suez (transected by the Suez Canal), 163 km (101 mi) wide.[125] (Geopolitically, Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula east of the Suez Canal is often considered part of Africa, as well.)[126]

The coastline is 26,000 km (16,000 mi) long, and the absence of deep indentations of the shore is illustrated by the fact that Europe, which covers only 10,400,000 km2 (4,000,000 sq mi) – about a third of the surface of Africa – has a coastline of 32,000 km (20,000 mi).[127] From the most northerly point, Ras ben Sakka in Tunisia (37°21′ N), to the most southerly point, Cape Agulhas in South Africa (34°51’15» S), is a distance of approximately 8,000 km (5,000 mi).[128] Cape Verde, 17°33’22» W, the westernmost point, is a distance of approximately 7,400 km (4,600 mi) to Ras Hafun, 51°27’52» E, the most easterly projection that neighbours Cape Guardafui, the tip of the Horn of Africa.[127]

Africa’s largest country is Algeria, and its smallest country is Seychelles, an archipelago off the east coast.[129] The smallest nation on the continental mainland is The Gambia.

African plate

Today, the African Plate is moving over Earth’s surface at a speed of 0.292° ± 0.007° per million years, relative to the «average» Earth (NNR-MORVEL56)

Climate

The climate of Africa ranges from tropical to subarctic on its highest peaks. Its northern half is primarily desert, or arid, while its central and southern areas contain both savanna plains and dense jungle (rainforest) regions. In between, there is a convergence, where vegetation patterns such as sahel and steppe dominate. Africa is the hottest continent on Earth and 60% of the entire land surface consists of drylands and deserts.[132] The record for the highest-ever recorded temperature, in Libya in 1922 (58 °C (136 °F)), was discredited in 2013.[133][134]

Ecology and biodiversity

The main biomes in Africa.

Africa has over 3,000 protected areas, with 198 marine protected areas, 50 biosphere reserves, and 80 wetlands reserves. Significant habitat destruction, increases in human population and poaching are reducing Africa’s biological diversity and arable land. Human encroachment, civil unrest and the introduction of non-native species threaten biodiversity in Africa. This has been exacerbated by administrative problems, inadequate personnel and funding problems.[132]

Deforestation is affecting Africa at twice the world rate, according to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).[135] According to the University of Pennsylvania African Studies Center, 31% of Africa’s pasture lands and 19% of its forests and woodlands are classified as degraded, and Africa is losing over four million hectares of forest per year, which is twice the average deforestation rate for the rest of the world.[132] Some sources claim that approximately 90% of the original, virgin forests in West Africa have been destroyed.[136] Over 90% of Madagascar’s original forests have been destroyed since the arrival of humans 2000 years ago.[137] About 65% of Africa’s agricultural land suffers from soil degradation.[138]

Environmental issues

Water

Africa Water Precipitation

Water in Africa is an important issue encompassing the sources, distribution and economic uses of the water resources on the continent. Overall, Africa has about 9% of the world’s fresh water resources and 16% of the world’s population.[141][142] Among its rivers are the Congo, Nile, Zambezi, Niger and Lake Victoria, considered the world’s second largest lake. Yet the continent is the second driest in the world, with millions of Africans still suffering from water shortages throughout the year.[143]

These shortages are attributed to problems of uneven distribution, population boom and poor management of existing supplies. Sometimes there are smaller numbers of people residing where there is large amount of water. For example, 30 percent of the continent’s water lies in the Congo basin inhabited by only 10 percent of Africa’s population.[144][143] There is significant variation in the rainfall patterns observed in different places and time. There is also high evaporation rates in some parts of the region resulting in lower percentages of precipitation in such places.[145][144] However, there is very significant inter-and intra-annual variability of all climate and water resources characteristics, so while some regions have sufficient water,[142] sub-Saharan Africa faces numerous water-related challenges that constrain economic growth and threaten the livelihoods of its people.[142] African agriculture is mostly based on rain-fed farming, and less than 10% of cultivated land in the continent is irrigated.[141][142] The impact of climate change and variability is thus very pronounced.[142] The main source of electricity is hydropower, which contributes significantly to the current installed capacity for energy.[142] The Kainji Dam is a typical hydropower resource generating electricity for all the large cities in Nigeria as well as their neighbouring country, Niger.[146] Hence, the continuous investment in the last decade, which has increased the amount of power generated.[142]

Climate change

Climate change in Africa is an increasingly serious threat as Africa is among the most vulnerable continents to the effects of climate change.[147][148][149] Some sources even classify Africa as «the most vulnerable continent on Earth».[150][151] This vulnerability is driven by a range of factors that include weak adaptive capacity, high dependence on ecosystem goods for livelihoods, and less developed agricultural production systems.[152] The risks of climate change on agricultural production, food security, water resources and ecosystem services will likely have increasingly severe consequences on lives and sustainable development prospects in Africa.[153] With high confidence, it was projected by the IPCC in 2007 that in many African countries and regions, agricultural production and food security would probably be severely compromised by climate change and climate variability.[154] Managing this risk requires an integration of mitigation and adaptation strategies in the management of ecosystem goods and services, and the agriculture production systems in Africa.[155]

Over the coming decades, warming from climate change is expected across almost all the Earth’s surface, and global mean rainfall will increase.[156] Currently, Africa is warming faster than the rest of the world on average. Large portions of the continent may become uninhabitable as a result of the rapid effects of climate change, which would have disastrous effects on human health, food security, and poverty.[157][158][159] Regional effects on rainfall in the tropics are expected to be much more spatially variable and the sign of change at any one location is often less certain, although changes are expected. Consistent with this, observed surface temperatures have generally increased over Africa since the late 19th century to the early 21st century by about 1 °C, but locally as much as 3 °C for minimum temperature in the Sahel at the end of the dry season.[160] Observed precipitation trends indicate spatial and temporal discrepancies as expected.[161][148] The observed changes in temperature and precipitation vary regionally.[162][161]

Fauna

Africa boasts perhaps the world’s largest combination of density and «range of freedom» of wild animal populations and diversity, with wild populations of large carnivores (such as lions, hyenas, and cheetahs) and herbivores (such as buffalo, elephants, camels, and giraffes) ranging freely on primarily open non-private plains. It is also home to a variety of «jungle» animals including snakes and primates and aquatic life such as crocodiles and amphibians. In addition, Africa has the largest number of megafauna species, as it was least affected by the extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna.

Politics

African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union consisting of 55 member states. The union was formed, with Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, as its headquarters, on 26 June 2001. The union was officially established on 9 July 2002[163] as a successor to the Organisation of African Unity (OAU). In July 2004, the African Union’s Pan-African Parliament (PAP) was relocated to Midrand, in South Africa, but the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights remained in Addis Ababa.

The African Union, not to be confused with the AU Commission, is formed by the Constitutive Act of the African Union, which aims to transform the African Economic Community, a federated commonwealth, into a state under established international conventions. The African Union has a parliamentary government, known as the African Union Government, consisting of legislative, judicial and executive organs. It is led by the African Union President and Head of State, who is also the President of the Pan-African Parliament. A person becomes AU President by being elected to the PAP, and subsequently gaining majority support in the PAP. The powers and authority of the President of the African Parliament derive from the Constitutive Act and the Protocol of the Pan-African Parliament, as well as the inheritance of presidential authority stipulated by African treaties and by international treaties, including those subordinating the Secretary General of the OAU Secretariat (AU Commission) to the PAP. The government of the AU consists of all-union, regional, state, and municipal authorities, as well as hundreds of institutions, that together manage the day-to-day affairs of the institution.

Extensive human rights abuses still occur in several parts of Africa, often under the oversight of the state. Most of such violations occur for political reasons, often as a side effect of civil war. Countries where major human rights violations have been reported in recent times include the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Sudan, Zimbabwe, and Ivory Coast.

Boundary conflicts

African states have made great efforts to respect interstate borders as inviolate for a long time. For example, the Organization of African Unity (OAU), which was established in 1963 and replaced by the African Union in 2002, set the respect for the territorial integrity of each state as one of its principles in OAU Charter.[164] Indeed, compared with the formation of European states, there have been fewer interstate conflicts in Africa for changing the borders, which has influenced the state formation there and has enabled some states to survive that might have been defeated and absorbed by others.[165] Yet interstate conflicts have played out by support for proxy armies or rebel movements. Many states have experienced civil wars: including Rwanda, Sudan, Angola, Sierra Leone, Congo, Liberia, Ethiopia and Somalia.[166]

Economy

Although it has abundant natural resources, Africa remains the world’s poorest and least-developed continent (other than Antarctica), the result of a variety of causes that may include corrupt governments that have often committed serious human rights violations, failed central planning, high levels of illiteracy, low self-esteem, lack of access to foreign capital, legacies of colonialism, the slave trade, and the Cold War, and frequent tribal and military conflict (ranging from guerrilla warfare to genocide).[167] Its total nominal GDP remains behind that of the United States, China, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom, India and France. According to the United Nations’ Human Development Report in 2003, the bottom 24 ranked nations (151st to 175th) were all African.[168]

Poverty, illiteracy, malnutrition and inadequate water supply and sanitation, as well as poor health, affect a large proportion of the people who reside in the African continent. In August 2008, the World Bank[169] announced revised global poverty estimates based on a new international poverty line of $1.25 per day (versus the previous measure of $1.00). 81% of the sub-Saharan African population was living on less than $2.50 (PPP) per day in 2005, compared with 86% for India.[170]

Sub-Saharan Africa is the least successful region of the world in reducing poverty ($1.25 per day); some 50% of the population living in poverty in 1981 (200 million people), a figure that rose to 58% in 1996 before dropping to 50% in 2005 (380 million people). The average poor person in sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to live on only 70 cents per day, and was poorer in 2003 than in 1973,[171] indicating increasing poverty in some areas. Some of it is attributed to unsuccessful economic liberalization programmes spearheaded by foreign companies and governments, but other studies have cited bad domestic government policies more than external factors.[172][173]

Africa is now at risk of being in debt once again, particularly in sub-Saharan African countries. The last debt crisis in 2005 was resolved with help from the heavily indebted poor countries scheme (HIPC). The HIPC resulted in some positive and negative effects on the economy in Africa. About ten years after the 2005 debt crisis in sub-Saharan Africa was resolved, Zambia fell back into debt. A small reason was due to the fall in copper prices in 2011, but the bigger reason was that a large amount of the money Zambia borrowed was wasted or pocketed by the elite.[174]

From 1995 to 2005, Africa’s rate of economic growth increased, averaging 5% in 2005. Some countries experienced still higher growth rates, notably Angola, Sudan and Equatorial Guinea, all of which had recently begun extracting their petroleum reserves or had expanded their oil extraction capacity.

In a recently published analysis based on World Values Survey data, the Austrian political scientist Arno Tausch maintained that several African countries, most notably Ghana, perform quite well on scales of mass support for democracy and the market economy.[175]

| Rank | Country | GDP (nominal, Peak Year) millions of USD |

Peak Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 568,499 | 2014 | |

| 2 | 475,231 | 2022 | |

| 3 | 458,708 | 2011 | |

| 4 | 213,810 | 2014 | |

| 5 | 156,083 | 2023 | |

| 6 | 145,712 | 2014 | |

| 7 | 142,867 | 2021 | |

| 8 | 118,130 | 2023 | |

| 9 | 92,542 | 2012 | |

| 10 | 85,421 | 2023 |

| Rank | Country | GDP (PPP, Peak Year) millions of USD |

Peak Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,803,584 | 2023 | |

| 2 | 1,372,624 | 2023 | |

| 3 | 990,030 | 2023 | |

| 4 | 620,971 | 2023 | |

| 5 | 393,847 | 2023 | |

| 6 | 387,233 | 2023 | |

| 7 | 341,999 | 2023 | |

| 8 | 265,631 | 2023 | |

| 9 | 229,471 | 2023 | |

| 10 | 228,031 | 2023 |

Tausch’s global value comparison based on the World Values Survey derived the following factor analytical scales: 1. The non-violent and law-abiding society 2. Democracy movement 3. Climate of personal non-violence 4. Trust in institutions 5. Happiness, good health 6. No redistributive religious fundamentalism 7. Accepting the market 8. Feminism 9. Involvement in politics 10. Optimism and engagement 11. No welfare mentality, acceptancy of the Calvinist work ethics. The spread in the performance of African countries with complete data, Tausch concluded «is really amazing». While one should be especially hopeful about the development of future democracy and the market economy in Ghana, the article suggests pessimistic tendencies for Egypt and Algeria, and especially for Africa’s leading economy, South Africa. High Human Inequality, as measured by the UNDP’s Human Development Report’s Index of Human Inequality, further impairs the development of human security. Tausch also maintains that the certain recent optimism, corresponding to economic and human rights data, emerging from Africa, is reflected in the development of a civil society.

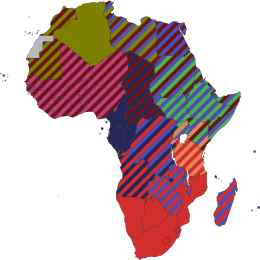

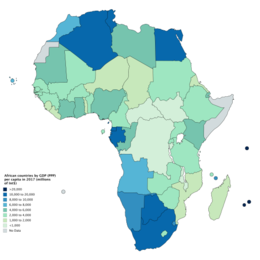

African countries by GDP (PPP) per capita in 2020

The continent is believed to hold 90% of the world’s cobalt, 90% of its platinum, 50% of its gold, 98% of its chromium, 70% of its tantalite,[176] 64% of its manganese and one-third of its uranium.[177] The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has 70% of the world’s coltan, a mineral used in the production of tantalum capacitors for electronic devices such as cell phones. The DRC also has more than 30% of the world’s diamond reserves.[178] Guinea is the world’s largest exporter of bauxite.[179] As the growth in Africa has been driven mainly by services and not manufacturing or agriculture, it has been growth without jobs and without reduction in poverty levels. In fact, the food security crisis of 2008 which took place on the heels of the global financial crisis pushed 100 million people into food insecurity.[180]

In recent years, the People’s Republic of China has built increasingly stronger ties with African nations and is Africa’s largest trading partner. In 2007, Chinese companies invested a total of US$1 billion in Africa.[119]

A Harvard University study led by professor Calestous Juma showed that Africa could feed itself by making the transition from importer to self-sufficiency. «African agriculture is at the crossroads; we have come to the end of a century of policies that favoured Africa’s export of raw materials and importation of food. Africa is starting to focus on agricultural innovation as its new engine for regional trade and prosperity.»[181]

Demographics

Africa’s population has rapidly increased over the last 40 years, and is consequently relatively young. In some African states, more than half the population is under 25 years of age.[182] The total number of people in Africa increased from 229 million in 1950 to 630 million in 1990.[183] As of 2021, the population of Africa is estimated at 1.4 billion [1][2]. Africa’s total population surpassing other continents is fairly recent; African population surpassed Europe in the 1990s, while the Americas was overtaken sometime around the year 2000; Africa’s rapid population growth is expected to overtake the only two nations currently larger than its population, at roughly the same time – India and China’s 1.4 billion people each will swap ranking around the year 2022.[184] This increase in number of babies born in Africa compared to the rest of the world is expected to reach approximately 37% in the year 2050, an increase of 21% since 1990 alone.[185]

Speakers of Bantu languages (part of the Niger–Congo family) are the majority in southern, central and southeast Africa. The Bantu-speaking peoples from the Sahel progressively expanded over most of sub-Saharan Africa.[186] But there are also several Nilotic groups in South Sudan and East Africa, the mixed Swahili people on the Swahili Coast, and a few remaining indigenous Khoisan («San» or «Bushmen») and Pygmy peoples in Southern and Central Africa, respectively. Bantu-speaking Africans also predominate in Gabon and Equatorial Guinea, and are found in parts of southern Cameroon. In the Kalahari Desert of Southern Africa, the distinct people known as the Bushmen (also «San», closely related to, but distinct from «Hottentots») have long been present. The San are physically distinct from other Africans and are the indigenous people of southern Africa. Pygmies are the pre-Bantu indigenous peoples of central Africa.[187]

The peoples of West Africa primarily speak Niger–Congo languages, belonging mostly to its non-Bantu branches, though some Nilo-Saharan and Afro-Asiatic speaking groups are also found. The Niger–Congo-speaking Yoruba, Igbo, Fulani, Akan, and Wolof ethnic groups are the largest and most influential. In the central Sahara, Mandinka or Mande groups are most significant. Chadic-speaking groups, including the Hausa, are found in more northerly parts of the region nearest to the Sahara, and Nilo-Saharan communities, such as the Songhai, Kanuri and Zarma, are found in the eastern parts of West Africa bordering Central Africa.

| Map of Africa indicating Human Development Index (2018). | ||

|

The peoples of North Africa consist of three main indigenous groups: Berbers in the northwest, Egyptians in the northeast, and Nilo-Saharan-speaking peoples in the east. The Arabs who arrived in the 7th century CE introduced the Arabic language and Islam to North Africa. The Semitic Phoenicians (who founded Carthage) and Hyksos, the Indo-Iranian Alans, the Indo- European Greeks, Romans, and Vandals settled in North Africa as well. Significant Berber communities remain within Morocco and Algeria in the 21st century, while, to a lesser extent, Berber speakers are also present in some regions of Tunisia and Libya.[188] The Berber-speaking Tuareg and other often-nomadic peoples are the principal inhabitants of the Saharan interior of North Africa. In Mauritania, there is a small but near-extinct Berber community in the north and Niger–Congo-speaking peoples in the south, though in both regions Arabic and Arab culture predominates. In Sudan, although Arabic and Arab culture predominate, it is mostly inhabited by groups that originally spoke Nilo-Saharan, such as the Nubians, Fur, Masalit and Zaghawa, who, over the centuries, have variously intermixed with migrants from the Arabian peninsula. Small communities of Afro-Asiatic-speaking Beja nomads can also be found in Egypt and Sudan.[189]

In the Horn of Africa, some Ethiopian and Eritrean groups (like the Amhara and Tigrayans, collectively known as Habesha) speak languages from the Semitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family, while the Oromo and Somali speak languages from the Cushitic branch of Afro-Asiatic.

Prior to the decolonization movements of the post-World War II era, Europeans were represented in every part of Africa.[190] Decolonization during the 1960s and 1970s often resulted in the mass emigration of white settlers – especially from Algeria and Morocco (1.6 million pieds-noirs in North Africa),[191] Kenya, Congo,[192] Rhodesia, Mozambique and Angola.[193] Between 1975 and 1977, over a million colonials returned to Portugal alone.[194] Nevertheless, white Africans remain an important minority in many African states, particularly Zimbabwe, Namibia, Réunion, and South Africa.[195] The country with the largest white African population is South Africa.[196] Dutch and British diasporas represent the largest communities of European ancestry on the continent today.[197]

European colonization also brought sizable groups of Asians, particularly from the Indian subcontinent, to British colonies. Large Indian communities are found in South Africa, and smaller ones are present in Kenya, Tanzania, and some other southern and southeast African countries. The large Indian community in Uganda was expelled by the dictator Idi Amin in 1972, though many have since returned. The islands in the Indian Ocean are also populated primarily by people of Asian origin, often mixed with Africans and Europeans. The Malagasy people of Madagascar are an Austronesian people, but those along the coast are generally mixed with Bantu, Arab, Indian and European origins. Malay and Indian ancestries are also important components in the group of people known in South Africa as Cape Coloureds (people with origins in two or more races and continents). During the 20th century, small but economically important communities of Lebanese and Chinese[119] have also developed in the larger coastal cities of West and East Africa, respectively.[198]

Religion

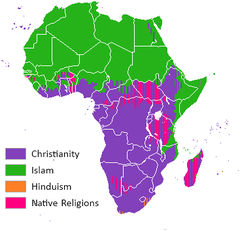

A map showing religious distribution in Africa

While Africans profess a wide variety of religious beliefs, the majority of the people respect African religions or parts of them. However, in formal surveys or census, most people will identify with major religions that came from outside the continent, mainly through colonisation. There are several reasons for this, the main one being the colonial idea that African religious beliefs and practices are not good enough. Religious beliefs and statistics on religious affiliation are difficult to come by since they are often a sensitive topic for governments with mixed religious populations.[199][200] According to the World Book Encyclopedia, Islam and Christianity are the two largest religions in Africa. According to Encyclopædia Britannica, 45% of the population are Christians, 40% are Muslims, and 10% follow traditional religions.[citation needed] A small number of Africans are Hindu, Buddhist, Confucianist, Baháʼí, or Jewish. There is also a minority of people in Africa who are irreligious.

Languages

By most estimates, well over a thousand languages (UNESCO has estimated around two thousand) are spoken in Africa.[201] Most are of African origin, though some are of European or Asian origin. Africa is the most multilingual continent in the world, and it is not rare for individuals to fluently speak not only multiple African languages, but one or more European ones as well.[further explanation needed] There are four major language families indigenous to Africa:

A simplistic view of language families spoken in Africa

- The Afroasiatic languages are a language family of about 240 languages and 285 million people widespread throughout the Horn of Africa, North Africa, the Sahel, and Southwest Asia.

- The Nilo-Saharan language family consists of more than a hundred languages spoken by 30 million people. Nilo-Saharan languages are spoken by ethnic groups in Chad, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, Sudan, South Sudan, Uganda, and northern Tanzania.

- The Niger-Congo language family covers much of sub-Saharan Africa. In terms of number of languages, it is the largest language family in Africa and perhaps one of the largest in the world.

- The Khoisan languages number about fifty and are spoken in Southern Africa by approximately 400,000 people.[202] Many of the Khoisan languages are endangered. The Khoi and San peoples are considered the original inhabitants of this part of Africa.

Following the end of colonialism, nearly all African countries adopted official languages that originated outside the continent, although several countries also granted legal recognition to indigenous languages (such as Swahili, Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa). In numerous countries, English and French (see African French) are used for communication in the public sphere such as government, commerce, education and the media. Arabic, Portuguese, Afrikaans and Spanish are examples of languages that trace their origin to outside of Africa, and that are used by millions of Africans today, both in the public and private spheres. Italian is spoken by some in former Italian colonies in Africa. German is spoken in Namibia, as it was a former German protectorate.

Health

Prevalence of HIV/AIDS in Africa, total (% of population ages 15–49), in 2011 (World Bank)

over 15%

5–15%

2–5%

1–2%

0.5-1%

0.1–0.5%

not available

More than 85% of individuals in Africa use traditional medicine as an alternative to often expensive allopathic medical health care and costly pharmaceutical products. The Organization of African Unity (OAU) Heads of State and Government declared the 2000s decade as the African Decade on African traditional medicine in an effort to promote The WHO African Region’s adopted resolution for institutionalizing traditional medicine in health care systems across the continent.[203] Public policy makers in the region are challenged with consideration of the importance of traditional/indigenous health systems and whether their coexistence with the modern medical and health sub-sector would improve the equitability and accessibility of health care distribution, the health status of populations, and the social-economic development of nations within sub-Saharan Africa.[204]

AIDS in post-colonial Africa is a prevalent issue. Although the continent is home to about 15.2 percent of the world’s population,[205] more than two-thirds of the total infected worldwide – some 35 million people – were Africans, of whom 15 million have already died.[206] Sub-Saharan Africa alone accounted for an estimated 69 percent of all people living with HIV[207] and 70 percent of all AIDS deaths in 2011.[208] In the countries of sub-Saharan Africa most affected, AIDS has raised death rates and lowered life expectancy among adults between the ages of 20 and 49 by about twenty years.[206] Furthermore, the life expectancy in many parts of Africa is declining, largely as a result of the HIV/AIDS epidemic with life-expectancy in some countries reaching as low as thirty-four years.[209]

Culture

Some aspects of traditional African cultures have become less practised in recent years as a result of neglect and suppression by colonial and post-colonial regimes. For example, African customs were discouraged, and African languages were prohibited in mission schools.[210] Leopold II of Belgium attempted to «civilize» Africans by discouraging polygamy and witchcraft.[210]

Obidoh Freeborn posits that colonialism is one element that has created the character of modern African art.[211] According to authors Douglas Fraser and Herbert M. Cole, «The precipitous alterations in the power structure wrought by colonialism were quickly followed by drastic iconographic changes in the art.»[212] Fraser and Cole assert that, in Igboland, some art objects «lack the vigor and careful craftsmanship of the earlier art objects that served traditional functions.[212] Author Chika Okeke-Agulu states that «the racist infrastructure of British imperial enterprise forced upon the political and cultural guardians of empire a denial and suppression of an emergent sovereign Africa and modernist art.»[213] Editors F. Abiola Irele and Simon Gikandi comment that the current identity of African literature had its genesis in the «traumatic encounter between Africa and Europe.»[214] On the other hand, Mhoze Chikowero believes that Africans deployed music, dance, spirituality, and other performative cultures to (re)assert themselves as active agents and indigenous intellectuals, to unmake their colonial marginalization and reshape their own destinies.»[215]

There is now a resurgence in the attempts to rediscover and revalue African traditional cultures, under such movements as the African Renaissance, led by Thabo Mbeki, Afrocentrism, led by a group of scholars, including Molefi Asante, as well as the increasing recognition of traditional spiritualism through decriminalization of Vodou and other forms of spirituality.

As of March 2023, 98 African properties are listed by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites. Among these proprieties, 54 are cultural sites, 39 are natural sites and 5 are mixed sites. The List Of World Heritage in Danger includes 15 African sites.[216]

Visual art

Nok figure (5th century BCE-5th century CE)

African art describes the modern and historical paintings, sculptures, installations, and other visual culture from native or indigenous Africans and the African continent. The definition may also include the art of the African diasporas, such as: African-American, Caribbean or art in South American societies inspired by African traditions. Despite this diversity, there are unifying artistic themes present when considering the totality of the visual culture from the continent of Africa.[217]

Pottery, metalwork, sculpture, architecture, textile art and fiber art are important visual art forms across Africa and may be included in the study of African art. The term «African art» does not usually include the art of the North African areas along the Mediterranean coast, as such areas had long been part of different traditions. For more than a millennium, the art of such areas had formed part of Berber or Islamic art, although with many particular local characteristics.

The Art of Ethiopia, with a long Christian tradition, is also different from that of most of Africa, where the Traditional African religion (with Islam in the north) was dominant until the 20th century.[218] African art includes prehistoric and ancient art, the Islamic art of West Africa, the Christian art of East Africa, and the traditional artifacts of these and other regions. Much African sculpture was historically in wood and other natural materials that have not survived from earlier than a few centuries ago, although rare older pottery and metal figures can be found some areas.[219] Some of the earliest decorative objects, such as shell beads and evidence of paint, have been discovered in Africa, dating to the Middle Stone Age.[220][221][222] Masks are important elements in the art of many peoples, along with human figures, and are often highly Stylized. There is a vast variety of styles, often varying within the same context of origin and depending on the use of the object, but wide regional trends are apparent; sculpture is most common among «groups of settled cultivators in the areas drained by the Niger and Congo rivers» in West Africa.[223] Direct images of deities are relatively infrequent, but masks in particular are or were often made for ritual ceremonies. Since the late 19th century there has been an increasing amount of African art in Western collections, the finest pieces of which are displayed as part of the history of colonization.

African art has had an important influence on European Modernist art,[224] which was inspired by their interest in abstract depiction. It was this appreciation of African sculpture that has been attributed to the very concept of «African art», as seen by European and American artists and art historians.[225]

West African cultures developed bronze casting for reliefs, like the famous Benin Bronzes, to decorate palaces and for highly naturalistic royal heads from around the Bini town of Benin City, Edo State, as well as in terracotta or metal, from the 12th–14th centuries. Akan gold weights are a form of small metal sculptures produced over the period 1400–1900; some apparently represent proverbs, contributing a narrative element rare in African sculpture; and royal regalia included impressive gold sculptured elements.[226] Many West African figures are used in religious rituals and are often coated with materials placed on them for ceremonial offerings. The Mande-speaking peoples of the same region make pieces from wood with broad, flat surfaces and arms and legs shaped like cylinders. In Central Africa, however, the main distinguishing characteristics include heart-shaped faces that are curved inward and display patterns of circles and dots.

Architecture

Like other aspects of the culture of Africa, the architecture of Africa is exceptionally diverse. Throughout the history of Africa, Africans have developed their own local architectural traditions. In some cases, broader regional styles can be identified, such as the Sudano-Sahelian architecture of West Africa. A common theme in traditional African architecture is the use of fractal scaling: small parts of the structure tend to look similar to larger parts, such as a circular village made of circular houses.[227]

African architecture in some areas has been influenced by external cultures for centuries, according to available evidence. Western architecture has influenced coastal areas since the late 15th century and is now an important source of inspiration for many larger buildings, particularly in major cities.

African architecture uses a wide range of materials, including thatch, stick/wood, mud, mudbrick, rammed earth, and stone. These material preferences vary by region: North Africa for stone and rammed earth, the Horn of Africa for stone and mortar, West Africa for mud/adobe, Central Africa for thatch/wood and more perishable materials, Southeast and Southern Africa for stone and thatch/wood.

Cinema

Cinema of Africa is both the history and present of the making or screening of films on the African continent, and also refers to the persons involved in this form of audiovisual culture. It dates back to the early 20th century, when film reels were the primary cinematic technology in use. During the colonial era, African life was shown only by the work of white, colonial, Western filmmakers, who depicted Africans in a negative fashion, as exotic «others».[228] As there are more than 50 countries with audiovisual traditions, there is no one single ‘African cinema’. Both historically and culturally, there are major regional differences between North African and sub-Saharan cinemas, and between the cinemas of different countries.[228]

The cinema of Tunisia and the cinema of Egypt are among the oldest in the world. Pioneers Auguste and Louis Lumière screened their films in Alexandria, Cairo, Tunis, Soussa and Hammam-Lif in 1896.[229][230] Albert Samama Chikly is often cited as the first producer of indigenous African cinema, screening his own short documentaries in the casino of Tunis as early as December 1905.[231] Alongside his daughter Haydée Tamzali, Chikly would go on to produce important early milestones such as 1924’s The Girl from Carthage. In 1935 the MISR film studio in Cairo began producing mostly formulaic comedies and musicals, but also films like Kamal Selim’s The Will (1939). Egyptian cinema flourished in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, considered its Golden Age.[232] Youssef Chahine’s seminal Cairo Station (1958) laid a foundation for Arab film.[233]

Music

A musician from South Africa

Given the vastness of the African continent, its music is diverse, with regions and nations having many distinct musical traditions. African music includes the genres amapiano, Jùjú, Fuji, Afrobeat, Highlife, Makossa, Kizomba, and others. African music also uses a large variety of instruments across the continent. The music and dance of the African diaspora, formed to varying degrees on African musical traditions, include American music like Dixieland jazz, blues, jazz, and many Caribbean genres, such as calypso (see kaiso) and soca. Latin American music genres such as cumbia, salsa music, son cubano, rumba, conga, bomba, samba and zouk were founded on the music of enslaved Africans, and have in turn influenced African popular music.[234]

Like the music of Asia, India and the Middle East, it is a highly rhythmic music. The complex rhythmic patterns often involving one rhythm played against another to create a polyrhythm. The most common polyrhythm plays three beats on top of two, like a triplet played against straight notes. Sub-Saharan African music traditions frequently rely on percussion instruments of many varieties, including xylophones, djembes, drums, and tone-producing instruments such as the mbira or «thumb piano.»[234][235]

Dance

African dance refers to the various dance styles of sub-Saharan Africa. These dances are closely connected with the traditional rhythms and music traditions of the region. Music and dancing is an integral part of many traditional African societies. Songs and dances facilitate teaching and promoting social values, celebrating special events and major life milestones, performing oral history and other recitations, and spiritual experiences.[236] African dance utilizes the concepts of polyrhythm and total body articulation.[237] African dances are a collective activity performed in large groups, with significant interaction between dancers and onlookers in the majority of styles.[238]

Sports

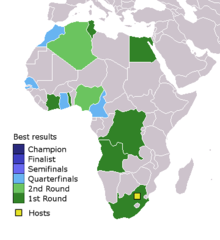

Best results of African men’s national football teams at the FIFA World Cup

Fifty-four African countries have football teams in the Confederation of African Football. Egypt has won the African Cup seven times, and a record-making three times in a row. Cameroon, Nigeria, Morocco, Senegal, Ghana, and Algeria have advanced to the knockout stage of recent FIFA World Cups. Morocco made history at the 2022 World Cup in Qatar as the first African nation to reach the semi-finals of the FIFA Men’s World Cup. South Africa hosted the 2010 World Cup tournament, becoming the first African country to do so.

The top clubs in each African football league play the CAF Champions League, while lower-ranked clubs compete in CAF Confederation Cup.

In recent years, the continent has made major progress in terms of state-of-the-art basketball facilities which have been built in cites as diverse as Cairo, Dakar, Johannesburg, Kigali, Luanda and Rades.[239] The number of African basketball players who drafted into the NBA has experienced major growth in the 2010s.[240]

Cricket is popular in some African nations. South Africa and Zimbabwe have Test status, while Kenya is the leading non-test team and previously had One-Day International cricket (ODI) status (from 10 October 1997, until 30 January 2014). The three countries jointly hosted the 2003 Cricket World Cup. Namibia is the other African country to have played in a World Cup. Morocco in northern Africa has also hosted the 2002 Morocco Cup, but the national team has never qualified for a major tournament.

Rugby is popular in several southern African nations. Namibia and Zimbabwe both have appeared on multiple occasions at the Rugby World Cup, while South Africa is the joint-most successful national team (alongside New Zealand) at the Rugby World Cup, having won the tournament on 3 occasions, in 1995, 2007, and 2019.[241]

Territories and regions

The countries in this table are categorized according to the scheme for geographic subregions used by the United Nations, and data included are per sources in cross-referenced articles. Where they differ, provisos are clearly indicated.

| Arms | Flag | Name of region[b] and territory, with flag |

Area (km2) |

Population[242] | Year | Density (per km2) |

Capital | Name(s) in official language(s) | ISO 3166-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Africa | |||||||||

| Algeria | 2,381,740 | 46,731,000 | 2022 | 17.7 | Algiers | الجزائر (al-Jazāʾir) / Algérie | DZA | ||

| Canary Islands (Spain)[c] | 7,492 | 2,154,905 | 2017 | 226 | Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Santa Cruz de Tenerife |

Canarias | IC | ||

| Ceuta (Spain)[d] | 20 | 85,107 | 2017 | 3,575 | — | Ceuta/Sebta/سَبْتَة (Sabtah) | EA | ||

| Egypt[e] | 1,001,450 | 82,868,000 | 2012 | 83 | Cairo | مِصر (Miṣr) | EGY | ||

| Libya | 1,759,540 | 6,310,434 | 2009 | 4 | Tripoli | ليبيا (Lībiyā) | LBY | ||

| Madeira (Portugal)[f] | 797 | 245,000 | 2001 | 307 | Funchal | Madeira | PRT-30 | ||

| Melilla (Spain)[g] | 12 | 85,116 | 2017 | 5,534 | — | Melilla/Mlilt/مليلية | EA | ||

| Morocco | 446,550 | 35,740,000 | 2017 | 78 | Rabat | المغرب (al-maḡrib)/ⵍⵎⵖⵔⵉⴱ (lmeɣrib)/Maroc | MAR | ||

| Tunisia | 163,610 | 10,486,339 | 2009 | 64 | Tunis | تونس (Tūnis)/Tunest/Tunisie | TUN | ||

| Western Sahara[h] | 266,000 | 405,210 | 2009 | 2 | El Aaiún | الصحراء الغربية (aṣ-Ṣaḥrā’ al-Gharbiyyah)/Taneẓroft Tutrimt/Sáhara Occidental | ESH | ||

| East Africa | |||||||||

| Burundi | 27,830 | 8,988,091 | 2009 | 323 | Gitega | Uburundi/Burundi/Burundi | BDI | ||

| Comoros | 2,170 | 752,438 | 2009 | 347 | Moroni | Komori/Comores/جزر القمر (Juzur al-Qumur) | COM | ||

| Djibouti | 23,000 | 828,324 | 2015 | 22 | Djibouti | Yibuuti/جيبوتي (Jībūtī)/Djibouti/Jabuuti | DJI | ||

| Eritrea | 121,320 | 5,647,168 | 2009 | 47 | Asmara | Eritrea | ERI | ||

| Ethiopia | 1,127,127 | 84,320,987 | 2012 | 75 | Addis Ababa | ኢትዮጵያ (Ītyōṗṗyā)/Itiyoophiyaa/ኢትዮጵያ/Itoophiyaa/Itoobiya/ኢትዮጵያ | ETH | ||

| French Southern Territories (France) | 439,781 | 100 | 2019 | — | Saint Pierre | Terres australes et antarctiques françaises | FRA-TF | ||

| Kenya | 582,650 | 39,002,772 | 2009 | 66 | Nairobi | Kenya | KEN | ||

| Madagascar | 587,040 | 20,653,556 | 2009 | 35 | Antananarivo | Madagasikara/Madagascar | MDG | ||

| Malawi | 118,480 | 14,268,711 | 2009 | 120 | Lilongwe | Malaŵi/Malaŵi | MWI | ||

| Mauritius | 2,040 | 1,284,264 | 2009 | 630 | Port Louis | Maurice/Moris | MUS | ||

| Mayotte (France) | 374 | 223,765 | 2009 | 490 | Mamoudzou | Mayotte/Maore/Maiôty | MYT | ||

| Mozambique | 801,590 | 21,669,278 | 2009 | 27 | Maputo | Moçambique/Mozambiki/Msumbiji/Muzambhiki | MOZ | ||

| Réunion (France) | 2,512 | 743,981 | 2002 | 296 | Saint Denis | La Réunion | FRA-RE | ||

| Rwanda | 26,338 | 10,473,282 | 2009 | 398 | Kigali | Rwanda | RWA | ||

| Seychelles | 455 | 87,476 | 2009 | 192 | Victoria | Seychelles/Sesel | SYC | ||

| Somalia | 637,657 | 9,832,017 | 2009 | 15 | Mogadishu | 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖 (Soomaaliya) /الصومال (aṣ-Ṣūmāl) | SOM | ||

| Somaliland | 176,120 | 5,708,180 | 2021 | 25 | Hargeisa | Soomaaliland/صوماليلاند (Ṣūmālīlānd) | |||

| South Sudan | 619,745 | 8,260,490 | 2008 | 13 | Juba | South Sudan | SSD | ||

| Sudan | 1,861,484 | 30,894,000 | 2008 | 17 | Khartoum | Sudan/السودان (as-Sūdān) | SDN | ||

| Tanzania | 945,087 | 44,929,002 | 2009 | 43 | Dodoma | Tanzania/Tanzania | TZA | ||

| Uganda | 236,040 | 32,369,558 | 2009 | 137 | Kampala | Uganda/Yuganda | UGA | ||

| Zambia | 752,614 | 11,862,740 | 2009 | 16 | Lusaka | Zambia | ZMB | ||

| Zimbabwe | 390,580 | 11,392,629 | 2009 | 29 | Harare | Zimbabwe | ZWE | ||

| Central Africa | |||||||||

| Angola | 1,246,700 | 12,799,293 | 2009 | 10 | Luanda | Angola | AGO | ||

| Cameroon | 475,440 | 18,879,301 | 2009 | 40 | Yaoundé | Cameroun/Kamerun | CMR | ||

| Central African Republic | 622,984 | 4,511,488 | 2009 | 7 | Bangui | Ködörösêse tî Bêafrîka/République centrafricaine | CAF | ||

| Chad | 1,284,000 | 10,329,208 | 2009 | 8 | N’Djamena | تشاد (Tšād)/Tchad | TCD | ||

| Republic of the Congo | 342,000 | 4,012,809 | 2009 | 12 | Brazzaville | Congo/Kôngo/Kongó | COG | ||