The Keyword Method is a mnemonic device designed to facilitate students’ learning of foreign vocabulary.

In this post, I explore the early origins of the keyword mnemonic method. Then, I explain what a keyword is. Next, I discuss how the keyword approach can be applied to acquire second language vocabulary. Finally, I consider the effectiveness and possible drawbacks of the keyword technique.

Defining mnemonic and “mnemonic devices”

The word mnemonic is derived from the Ancient Greek word μνημονικός (mnēmonikos), meaning of memory or relating to memory. There is also a clear link between the word mnemonic and Mnemosyne — the Greek goddess of memory in Greek mythology.

Essentially, mnemonic devices are learning strategies which serve to enhance the learning process and subsequent recall of information (Jurowski et al., 2015, p.4).

Levin (1980, p.10) points out that mnemonic techniques are generally applied to information that is hard to learn, remember or comprehend.

The Early Origins of the Keyword Method

In his excellent thesis on the Keyword Method, Joern Hauptmann (2004, p.84) writes that the origin of the keyword method is uncertain. However, Hauptmann (ibid.) claims that the first explicit mention of the method is from the middle of the 19th century by J. Bacon for the learning of French vocabulary.

By the mid-1970s, several cognitive psychologists revived fresh interest in the Keyword Method. At the forefront of such renewed interest were Richard Atkinson and Michael Raugh, who reported on the effectiveness of the Keyword Method. When they conducted an experiment into the learning and retention of a Russian vocabulary, Atkinson and Raugh (1975, p.126) described the Keyword Method as a “mnemonic procedure”. Other prominent researchers into the keyword mnemonic at that time include Michael Pressley and Joel R. Levin.

What is a keyword?

First of all, it’s important to define what a keyword is in the context of the Keyword Method.

Atkinson (1975, p.821) defines a keyword as:

… an English word that sounds like some part of the foreign word.

Atkinson (ibid.) goes on to mention that the keyword has no (lexical) relationship to the foreign word apart from the fact that it is similar in terms of sound.

Of course, when Atkinson refers to an “English word”, he really meant a native-language word or phrase. After all, speakers of any native tongue can use the Keyword Method.

Furthermore, when Atkinson (1975, p.821) writes “some part of the foreign word”, it’s useful to add that the keyword usually sounds like the beginning or all of the foreign word.

How does the Keyword Method work?

In question, then, is a two-step mnemonic method.

Step 1:

The first stage requires the subject to associate the spoken foreign word with the keyword.

This association is formed rapidly owing to acoustic similarity. Atkinson (1975, p.821) defined this likeness in sound as an acoustic link.

Step 2:

The second stage requires the subject to form a mental image linking the keyword and the English translation. This mental image is what Atkinson (ibid.) calls an imagery link.

An example of the Keyword Method in action

Levin (1980) illustrates the two steps above with the example of an American student who is attempting to learn the Spanish word carta. Carta means postal letter in English.

So, in the acoustic link stage, the student needs to generate a keyword that:

(a) is a familiar English word;

(b) sounds like a part (not necessarily all) of the foreign word;

(c) ideally, is picturable.

Hence, an obvious keyword for carta is cart (shopping trolley in British English).

In the imagery link stage, the student must form a visual image whereby both the keyword and English translation referents interact in some way. Hence, for carta, the student might visualise a shopping cart transporting a postal letter:

Source: Levin, 1980, p.27

Why is the Keyword Method so effective?

Having established how the Keyword Method works, here are two reasons why the method may be effective for language learners:

1. The chosen keyword does not have to be a single word

It’s interesting to note that the keyword does not have to be a single word (Atkinson, 1975, p.822).

Hence, there is a great deal of flexibility in the choice of keywords. This is due to the fact that any part of a foreign word may be used as the key sound. When it comes to selecting a keyword for a polysyllabic foreign word, it’s possible to use anything from a monosyllable to a longer word, or even a short phrase which “spans” the entire foreign word.

Back to Atkinson and Raugh (1975). The authors investigated the application of the Keyword Method to the acquisition of a Russian vocabulary among 52 Stanford university graduates. For the test vocabulary, the testing committee chose 38 keyword phrases rather than single keywords.

Without going too deeply into the statistics, Atkinson and Raugh (1975, p.131) discovered that the probability of learning a keyword-phrase item was roughly the same as the probability of learning a single-keyword item.

2. The keyword approach lends itself to bizarre and outrageous interactions in one’s mind

Levin (1980, p.14) isn’t so enthusiastic about the generation of unusual or ‘bizarre’ images when it comes to the effectiveness of a mnemonic system based on imagery:

There is no convincing support for the claim that «bizarre is better.»

However, the same author (ibid.) points to research which backs up the claim that “clearly visualised or vivid images are more memorable than weak ones”.

Personally, I think there’s a fine line between vividness and bizarreness. Can’t a vivid image be bizarre and vice versa?

And aren’t all visual images generated by users of the Keyword Method bizarre in some way, shape or form? Is the shopping cart with the postal letter really vivid without a single trace of bizarreness?

Shapiro and Waters (2005), who investigated the cognitive processes underlying the Keyword Method, seem to have warmed to the idea of bizarreness and outrageous visualisation. For the learning of the French word stylo, the authors propose the English keyword steel. One logical visual interaction that the student can play out in their mind is a large pen made of a steel girder.

Then, Shapiro and Waters (2005, p.130) state that this interaction “needs to be played out vividly in the student’s mind”. For instance, the student might envision a famous film star struggling to sign autographs with a huge steel girder which glimmers in the sunlight. The authors, referring to a claim made by psychologist Robert Salso (1998, in Shapiro and Waters, 2005) state that this interaction “may seem silly, but the more outrageous the interaction is, the more effective the method is”.

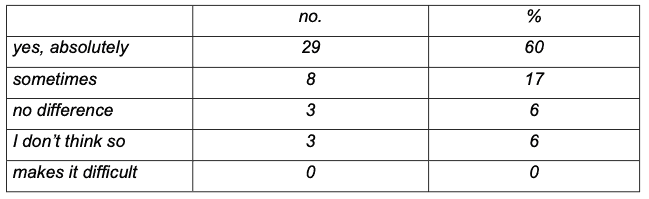

Hauptmann’s thesis is particularly illuminating when it comes to the relationship between the concept of bizarreness and the keyword technique. In a survey, he asked 48 students “The keywords and the images are frequently rather silly and far-fetched (bizarre). Are you of the (subjective) opinion that this helps learning/retention?”

The results were conclusive:

Source: Hauptmann, 2004, p.66

A decisive majority of the learners were of the opinion that bizarreness assisted in their learning of vocabulary.

Several of Hauptmann’s subjects also showed a preference for strange and funny links when the author interviewed them:

Interview 1 (Hauptmann, p.184)

J= interview

M + F = participants

Interview 2 (Hauptmann, p.189)

What are the possible drawbacks of the Keyword Method?

Let’s take a look at some of the possible drawbacks of the keyword technique, as put forward by prominent researchers in the field of mnemonics.

1. They keyword mnemonic method might not be all it’s cracked up to be when it comes to backward recall

In her article on the keyword strategy, Dr Fiona McPherson, a cognitive psychologist specialising in practical applications of memory research, sheds light on the value of Keyword in regard to forward and backward recall. McPherson makes explicit reference to the recall of the Spanish word carta.

According to McPherson:

The value of the keyword mnemonic is of course, in forward recall — that is … you learned that carta meant letter. When you see the word carta, the keyword mnemonic will help you remember that it means letter.

Nevertheless, McPherson questions the usefulness of the keyword mnemonic when it comes to recalling the Spanish word for letter.

McPherson responds to the challenge of backward recall by referring to a study (Pressley et al, 1980) which considered the question of forward and backward recall. The keyword mnemonic outperformed other memory strategies for forward recall (remembering the English word when given the Spanish). However, the Keyword Method didn’t prove to be better nor worse than the other strategies when it came to backward recall (i.e. recalling the Spanish word).

Overall, the biggest challenge is generating the (unfamiliar) Spanish word from the keyword. This task is much tougher than recalling the (familiar) keyword from the Spanish.

2. Research studies suggest that subjects perform better if an experimenter/teacher provides keywords

In the discussion section of their research study into the acquisition of a Russian vocabulary, Atkinson and Raugh (1975, p.131) ask an important question: Should the experimenter supply the keyword or can the subject generate his own more effectively?

To answer this question, the authors chose to refer to an unpublished Russian vocabulary learning experiment, similar to their own one. Essentially, all subjects were given instruction in the Keyword Method. During the experiment, half of the items were presented for study with a keyword, whereas the other items did not come with a keyword (i.e. subjects had to generate their own keyword).

In that unpublished experiment, the subjects fared better on the keyword supplied items. Generally, instruction in the keyword technique was beneficial, and even more so if the experimenter also provided the keywords. Given that Atkinson and Raugh’s subjects hadn’t received previous training in Russian, the authors conclude that beginners benefit most from keyword supplied items (Atkinson and Raugh, 1985, p.131). Naturally, then, keyword supplied items may be less useful to those who are more experienced with both the target language and the method itself.

All in all, lower level language learners who are intent on becoming more independent in their language learning journey might be better off keeping vocabulary notebooks or resorting to good old-fashioned rote memorisation.

3. Learners may need extended training with the keyword mnemonic method

If subjects in research studies and experiments prefer to lean on their experimenters for keywords (see 2 above), it might be tempting to assume that learners need more protracted training with the keyword mnemonic technique.

It seems that many of the experimental studies of the Keyword Method incorporated training that was too short. For instance, Hall (1988) only spent a total of three hours over a span of four weeks instructing learners in the use of the keyword technique. Frankly, this is not enough time.

Atkinson (1975, p.398) himself concedes that “students should be coached by an expert until they are proficient in the skill.”

4. The Keyword Method may be less effective when it comes to learning abstract nouns, verbs and adjectives in the target language

Dr Fiona McPherson highlights that:

The weight of the evidence is probably against the view that the [keyword] mnemonic should be restricted to concrete words, but it may well be more difficult to come up with good, concrete images for abstract words.

Unfortunately, researchers tend to use concrete words (which are easily imageable). Very few studies have compared both concrete and abstract words.

Hauptmann (2004, p.63) writes that it is possible to make use of a technique whereby the keyword sounds like the target (abstract) word. For the target word unconscious, the author proposes the keyword Conan, as in Conan the barbarian (Arnold Schwarzenegger in a film). This leads to the image that Conan hits a learner unconscious. Despite such frivolity with the keyword mnemonic method, the fact remains that the learner would have to expend a great deal of cognitive effort to recall a single abstract word.

Atkinson (1975), who along with members of the Slavic Languages Department at Stanford, developed a vocabulary-learning program designed to supplement the second-year course in Russian. It’s telling that, during interviews held at the end of the program, students reported that the Keyword Method worked least well for adjectives. Of course, there is a greater possibility that adjectives are abstract in nature.

5. It’s not always possible to come up with a phonetically similar keyword

I’ve already established that the keyword should be phonetically similar, although not necessarily identical, to the target word in the second language.

It’s safe to assume that it’s easier to apply the Keyword Method when two languages are from the same language group, as with English and German (both West Germanic languages). Even though they’re not from the same language group, French and English also have a great deal in common in a phonetic sense.

However, how useful is the Keyword Method for speakers of English trying to attain a Slavic language vocabulary, and vice versa?

When it comes to the acquisition of a Russian vocabulary, Atkinson and Raugh (1975, p.132) hint at “Poor performance on a given item in the keyword condition” due to either a poor acoustic link, weak imagery link or both. Therefore, the authors’ subjects did have some difficulties due to phonetically ineffective keywords.

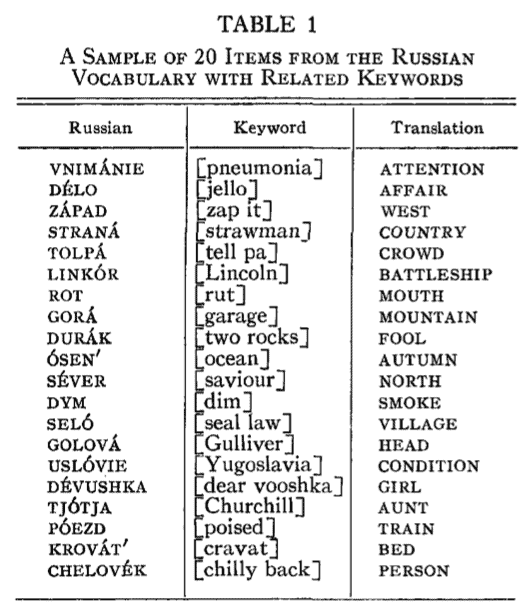

In fact, let’s check out a sample of items from the Russian vocabulary with related keywords (in Atkinson and Raugh, 1975, p.128):

I don’t have to be an expert in Russian to state that some of the keywords are phonetically dissimilar to their mother tongue equivalents. For instance, chelovek is certainly not phonetically akin to the keyword chilly back.

My brief experience with applying the Keyword Method to the learning of Polish vocabulary

Some time ago, I attempted to learn car parts in the Polish language using the keyword mnemonic technique.

It was a fruitless task because so many combinations of letters in Polish are phonetically dissimilar to those you’d find in English.

For example, the Polish word for bumper is zderzak. I’m still racking my brains as to how to come up with a remotely viable keyword item in English that sounds like either zde or rzak.

I also think that one is immediately drawn to associating the first syllable of the target language word with a potential keyword. Certainly, I found it difficult to look further than the first syllable when trying to acquire Polish vocabulary for car parts.

Conclusion

Just because I listed more disadvantages of the keyword mnemonic method than advantages, it doesn’t mean that this strategy is ineffective.

I may have adopted a pessimistic tone when it comes to the acquisition of Polish vocabulary. However, it requires a great deal of persistence, practice and patience to apply the Keyword Method even when phonetic dissimilarities between the target word and the keyword cause frustration.

The keyword strategy, as McPherson states, is “probably best used selectively, perhaps for particularly difficult items”. This sentiment is also shared by Pavičić Takač (2008, p.80).

All in all, the Keyword Method does not guarantee long-term vocabulary retention (Pavičić Takač, 2008, p.80). The language learner and language teacher should put their eclectic hats on. This is because the keyword strategy perhaps should go hand in hand with other language learning strategies, such as vocabulary notebooks. The Keyword Method, alone, cannot reveal a word’s most salient contextual, syntactic, lexical and grammatical features. This is why I store all of my language learning information in a Word-Phrase Table.

References

Atkinson, R.C., (1975). Mnemotechnics in second-language learning. American Psychologist, 30(8), 821–828.

Atkinson, R.C, and Raugh, M.R. (1975). An Application of the Mnemonic Keyword Method to the Acquisition of a Russian Vocabulary, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 104 (2), 126-133

Hall, J.W. (1988). On the utility of the keyword mnemonic for vocabulary learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 554-562.

Hauptmann, J., (2004). ‘The Effect of the Integrated Keyword Method on Vocabulary Retention and Motivation’, PhD thesis, University of Leicester, Leicester

Jurowski, K., Jurowska, A., and Krzeczkowska, M. (2015). Comprehensive review of mnemonic devices and their applications: State of the art, International e-Journal of Science: Medicine and Education, 9 (3), 4-9

Levin, J.R., (1980). The Mnemonic ‘80s: Keywords in the Classroom, Wisconsin Univ.Madison. Research and Development Center for Individualized Schooling, Theoretical Paper No.86, 1-57

McPherson, F. (no date). ‘Using the keyword method to learn vocabulary’. Available at:

https://www.mempowered.com/mnemonics/language/using-keyword-method-learn-vocabulary

Pavičić Takač, V. (2008). Vocabulary Learning Strategies and Foreign Language Acquisition, Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters Ltd

Shapiro, A.M., and Waters, D.L. (2005). An investigation of the cognitive processes underlying the keyword method of foreign vocabulary learning, Language Teaching Research, 9(2), pp.129-146

In the mid-seventies, Raugh and Atkinson had remarkable results using the keyword method to teach Russian vocabulary to college students. While later studies have not tended to find such dramatic results, nevertheless, a large number of studies have demonstrated an advantage in using the keyword mnemonic to learn vocabulary.

Some researchers have become huge fans of the strategy. Others have suggested a number of limitations. Let’s look at these.

Remembering for the long term

The keyword method is undeniably an effective method for accelerating learning of suitable material. Nor is there any doubt that it improves immediate recall. Which can be useful in itself. However, what people want is long-term recall, and it is there that the advantages of the keyword method are most contentious1.

While many studies have found good remembering a week or two after learning using the keyword mnemonic, others have found that remembering is no better one or two weeks later whether people have used the keyword mnemonic or another strategy. Some have found it worse.

It has been suggested that, although the keyword may be a good retrieval cue initially, over time earlier associations may regain their strength and make it harder to retrieve the keyword image. This seems very reasonable to me — any keyword is, by its nature, an easily retrieved, familiar word; therefore, it will already have a host of associations. When you’re tested immediately after learning the keyword, this new link will of course be fresh in your mind, and easily retrieved. But as time goes on, and the advantage of recency is lost, what is there to make the new link stronger than the other, existing, links? Absolutely nothing — unless you strengthen it. How? By repetition.

Note that it is not the keyword itself that fails to be remembered. It is the image. The weakness then, is in the link between keyword and image. (For example, the Tagalog word araw, meaning sun, is given the keyword arrow; when tested, araw easily recalls the keyword arrow, but the image connecting arrow with sun is gone). This is the link you must strengthen.

The question of the relative forgetting curves of the keyword mnemonic and other learning strategies is chiefly a matter of theoretical interest — I don’t think any researcher would deny that repetition is always necessary. But the “magic” of the keyword mnemonic, as espoused by some mnemonic enthusiasts, downplays this necessity. For practical purposes, it is merely sufficient to remember that, for long-term learning, you must strengthen this link between keyword and image (or sentence) through repeated retrieval (but probably not nearly as often as the repetition needed to “fix” meaningless information that has no such mnemonic aid).

One final point should be made. If the material to be learned is mastered to the same standard, the durability of the memory — how long it is remembered for — will, it appears, be the same, regardless of the method used to learn it2.

Are some keyword mnemonics easier to remember than others?

A number of factors may affect the strength of a keyword mnemonic. One that’s often suggested is whether or not the mnemonic is supplied to the student, or thought up by them. Intuitively, we feel that a mnemonic you’ve thought up yourself will be stronger than one that is given to you.

One study that compared the effectiveness of keywords provided versus keywords that are self-generated, found that participants who were required to make up their own keywords performed much worse than those who were given keywords3. This doesn’t answer the question of the relative durability, but it does point to how much more difficult the task of generating keywords is. This has been confirmed in other studies.

The quality of the keyword mnemonic may affect its durability. Mnemonics that emphasize distinctiveness, that increase the vividness and concreteness of the word to be learned, are remembered less well over time than mnemonics that emphasize relational and semantic information (which is why the emphasis in recent times is on making interactive images or sentences, in which the keyword and definition interact in some way). Having bizarre images seems to help remembering immediately after learning (when there is a mix of bizarre and less unusual images), but doesn’t seem to help particularly over the long term.

The advantage of a semantic connection may be seen in the following example, taken from an experimental study3. Students in a free control condition (those told to use their own methods to remember), almost all used a keyword-type technique to learn some items. Unlike those in the keyword group, the keywords chosen by these subjects typically had some semantic connection as well. (The use of somewhat arbitrary keywords is characteristic of the strategy as originally conceived by Atkinson). Thus, for the Spanish word pestana, meaning eyelash, several people used the phrase paste on as a link, reflecting an existing association (pasting on false eyelashes). The keyword supplied to the keyword group, on the other hand, was pest, which has no obvious connection to eyelash. (It is also worth noting that verbal links were more commonly used by control subjects, rather than mental images.)

It has been suggested that keywords that are semantically as well as acoustically related to the word to be learned might prove more durable.

Controlled presentation

For experimental reasons, the information to be learned is usually presented at a fixed rate, item by item. There is some suggestion that an unpaced situation, where people are simply presented with all the information to be learned and given a set time to study it, allows better learning, most particularly for the repetition strategy. The performance of rote repetition may have been made poorer by constraining it in this way in some experimental studies.

An unpaced study time is of course the more normal situation.

The importance of one-to-one instruction and the need for practice

What is clear from the research is that instruction in the technique is vitally important. Most particularly, the superiority of the keyword mnemonic tends to be found only when the students have been treated individually, not when they have been instructed as a group. At least, this is true for adults and adolescents, but not, interestingly, for children. Children can benefit from group instruction in the technique. Why this is, is not clear. However, I would speculate that it may have something to do with older students having already developed their own strategies and ideas. More individually-oriented instruction might be needed to counteract this depository of knowledge.

It might also be that children are given more direction in the using of the technique. That is, they are given the keywords; the images may be described to them, and even drawn. Clearly this is much simpler than being required to think up your own keywords, create your own links.

It does seem clear that durable keyword images require quite a lot of practice to create. It has been suggested that initially people tend to simply focus on creating distinctive images. It may only be with extensive practice that you become able to reliably create images that effectively integrate the relational qualities of the bits of information.

Some words benefit more from the keyword mnemonic

It has been suggested that the keyword mnemonic works effectively only on concrete words. For the most part, researchers only use concrete words (which are easily imageable). Studies which have compared the two are rare. The weight of the evidence is probably against the view that the mnemonic should be restricted to concrete words, but it may well be more difficult to come up with good, concrete images for abstract words. However, verbal mnemonics (a sentence can link the keyword with the definition) don’t suffer the same drawback.

In experimental studies, the words are usually vetted to make sure they’re not “easy” to learn because of obvious acoustic or graphic similarities with familiar words. The implication of this for real world learning, is that there is no reason to think that such words require a keyword mnemonic.

How important is the image?

Most research has focused on using an image to link the keyword with the definition. One study which compared the using of an image with the use of a sentence (in a study of children’s learning of Spanish words) found no difference (the sentence mnemonic in fact scored higher, but the difference was not significant)4.

Is the keyword mnemonic of greater benefit to less able students?

Several researchers have suggested that the keyword mnemonic might be of greater benefit to less able students, that the keyword mnemonic may be a means by which differences in learning ability might be equalised. One study that failed to find any superiority in the keyword mnemonic among college students, pointed to the high SAT scores of their students. They suggested that those studies which have found a keyword superiority using college students, have used students who were less verbally able5.

What seems likely, is that teaching the keyword mnemonic to more able students has less impact than teaching it to less able students, because the more able students already have a variety of effective strategies that they use. It is worth noting that, just because students are instructed to use a particular strategy, that doesn’t mean that they will. In one experimental study, for example, when subjects were asked about the strategies they used, 17 out of the 40 control subjects (instructed to use their own methods) used the keyword method for at least some items, while every keyword subject used the keyword method for at least seven items (implying they didn’t always). In that study, it was found that, for the control subjects, the probability of recalling keyword-elaborated items was .81 vs .45 for other items; while for the keyword group, the probability of recall for keyword-elaborated items was .80 vs .16 for those items for which they didn’t use a keyword mnemonic6.

Comparing the keyword mnemonic to other strategies

As a general rule, experimental studies into the effectiveness of the keyword mnemonic have compared it to, most often, rote repetition, or, less often, “trying your hardest to remember” (i.e., your own methods). It is not overwhelmingly surprising that the keyword mnemonic should be superior to rote repetition, and the study quoted just above reveals why comparisons with “free” controls might show inconsistent (and uninformative) results.

Studies which have directly compared the keyword method to other elaborative strategies are more helpful.

A number of studies have compared the keyword strategy against the context method of learning vocabulary (much loved by teachers; students experience the word to be learned in several different meaningful contexts). Theory suggests that the context method should encourage multiple connections to the target word, and is thus expected to be a highly effective strategy. However, the studies have found that the keyword method produces better learning than the context method.

It has been suggested that students might benefit more from the context method if they had to work out the meaning of the word themselves, from the context. However, a study which explored this possibility, found that participants using the context method performed significantly worse than those using the keyword mnemonic5. This was true even when subjects were given a test that would be thought to give an advantage to the context method — namely, subjects being required to produce meaningful sentences with the target words.

The same researchers later pursued the possibility that the context method might, nevertheless, prove superior in long-term recall — benefiting from the multiple connections / retrieval paths to the target word. In an experiment where both keyword and context groups learned the words until they had mastered them, recall was no better for the context group than it was for the keyword group, when tested one week later (on the other hand, it was no worse either)2.

Two more recent studies have confirmed the superiority of the keyword mnemonic over the context method7.

Another study looked at the question of whether a combined keyword – repetition strategy (in which subjects were told to use repetition as well as imagery when linking the keyword to the English translation of the word to be learned) was better than the keyword strategy on its own. They failed to find any benefit to using repetition on top of the imagery8.

Given the procedures used, I can see why this might occur. Imagine you’re trying to learn that carta is Spanish for letter. The obvious keyword is cart. Accordingly, you form an image of a cart full of letters. However, having constructed this image, you are now told to repeat the salient words “carta — letter” over and over to yourself. It’s not hard to see that many people might completely lose track of the image while they are doing this. Thus the repetition component of the strategy would not be so much augmenting the imagery link, as replacing it. Repetition of the link you are supposed to be augmenting (a cart full of letters) might be more useful (in fact, I personally would repeat to myself: “carta – letter; a cart full of letters”).

Backward recall

The value of the keyword mnemonic is of course, in forward recall — that is, in the above example, you learned that carta meant letter. When you see the word carta, the keyword mnemonic will help you remember that it means letter. But if you are asked for the Spanish for letter, how helpful will the keyword mnemonic be then?

A study that looked at this question found that the keyword mnemonic was no worse for backward recall than the other strategies they employed8. On the other hand, it was no better, either — and this despite being superior for forward recall (remembering the English when given the Spanish). The failure of the method was not due to any difficulty in recalling the keyword itself. Remember, the English meaning and the keyword are tied together in the mnemonic image, so it is not surprising that remembering the keyword given the English was as high as remembering the English given the keyword. But the problem is, of course, that generating the (unfamiliar) Spanish word from the keyword is much harder than remembering the (familiar) keyword from the Spanish.

Using the keyword mnemonic to remember gender

One other aspect of vocabulary learning for many languages is that of gender. The keyword mnemonic has successfully been used to remember the gender of nouns, by incorporating a gender tag in the image9. This may be as simple as including a man or a woman (or some particular object, when the language also contains a neutral gender), or you could use some other code — for example, if learning German, you could use the image of a deer for the masculine gender.

Why should the keyword mnemonic be an effective strategy?

Let’s think about the basic principles of how memory works.

The strength of memory codes, and thus the ease with which they can be found, is a function largely of repetition. Quite simply, the more often you experience something (a word, an event, a person, whatever), the stronger and more easily recalled your memory for that thing will be.

This is why the most basic memory strategy — the simplest, and the first learned — is rote repetition.

Repetition is how we hold items in working memory, that is, “in mind”. When we are told a phone number and have to remember it long enough to either dial it or write it down, most of us repeat it frantically.

Spaced repetition — repetition at intervals of time — is how we cement most of our memory codes in our long-term memory store. If you make no deliberate attempt to learn a phone number, yet use it often, you will inevitably come to know it (how many repetitions that will take is a matter of individual variability).

But most of us come to realize that repetition is not, on its own, the most effective strategy, and when we deliberately wish to learn something, we generally incorporate other, more elaborative, strategies.

Why do we do that? If memory codes are strengthened by repetition, why isn’t it enough to simply repeat?

Well, it is. Repetition IS enough. But it’s boring. That’s point one.

Point two is that making memory codes more easily found (which is after all the point of the exercise) is not solely achieved by making the memory codes stronger. Also important is making lots of connections. Memory codes are held in a network. We find a particular one by following a trail of linked codes. Clearly, the more trails lead to the code you’re looking for, the more likely you are to find it.

Elaborative strategies — mnemonic strategies, organizational strategies — work on this aspect. They are designed to increase the number of links (connections) a memory code has. Thus, when we note that lamprey is an “eel-like aquatic vertebrate with sucker mouth”, we will probably make links with eels, with fish, with the sea. If we recall that Henry I was said to have died from a surfeit of lampreys, we have made another link. Which in turn might bring in yet another link, that Ngaio Marsh once wrote a mystery entitled “A surfeit of lampreys”. And if you’ve read the book, this will be a good link, being itself rich in links. (As the earlier link would be if you happen to be knowledgeable about Henry I).

On the other hand, in the absence of any knowledge about lampreys, you could have made a mnemonic link with the word “lamp”, and imagined an eel-like fish with lamps in its eyes, or balanced on its head.

So, both types of elaborative strategy have the same goal — to increase the number of connections. But mnemonic links are weaker in the sense that they are arbitrary. Their value comes in those circumstances when either you lack the knowledge to make meaningful connections, or there is in fact no meaningful connection to be made (this is why mnemonics are so popular for vocabulary learning, and for the learning of lists and other ordered information).

Where does that leave us?

- Memory codes are made stronger by repetition

- Repetition is enough on it’s own to make a strong memory code

- Achieving enough repetitions, however, is a lengthy and often boring process

- Memory codes are also made easier to find by increasing the number of links they have to other memory codes

- Elaborative strategies work on this principle of making connections with existing codes

- Some elaborative strategies make meaningful connections between memory codes — these are stronger

- Mnemonic strategies make connections that are not meaningful

- Mnemonic strategies are most useful in situations where there are no meaningful connections to be made, or you lack the knowledge to make meaningful connections

Mnemonic strategies have therefore had particular success in the learning of other languages. However, if you can make a meaningful connection, that will be more effective. For example, in Spanish the word surgir means to appear, spout, arise. If you connect this to the word surge, from the Latin surgere, to rise, then you have a meaningful connection, and you won’t, it is clear, have much trouble when you come across the word. However, if your English vocabulary does not include the word surge, you might make instead a mnemonic connection, such as surgir sounds like sugar, so you make a mental image involving spouting sugar. Now, imagine each of these situations. Imagine you don’t come across the word again for a month. When you do, which of these connections is more likely to bring forth the correct meaning?

But of course, it is not always possible to make meaningful connections.

The thing to remember however, is that you haven’t overcome the need for repetition. These strategies are adjuncts. The basic principle must always be remembered: Memory codes are made stronger by repetition. Links are made stronger by repetition. If you don’t practice the mnemonic, it won’t be remembered. The same is true for any connection, but meaningful connections are inherently stronger, so they don’t need as many repetitions.

I would also note that the experimental research invariably involves very limited numbers of words to be learned. While this is entirely understandable, it does raise the question of the extent to which these findings are applicable to real world learning situations. If you are learning a new language, you are going to have to learn at least 2000 new words. Does the keyword mnemonic hold up in those circumstances? The keyword mnemonic has been used in real world situations (intensive language courses), but these are not experimental situations, and we must be wary of the conclusions we draw from them. The keyword strategy does take time and effort to implement, and may well have disadvantages if used to excess. Some words lend themselves to other techniques. At least for more experienced students (who will have a number of effective strategies, and are capable of applying them appropriately) the keyword strategy is probably best used selectively, perhaps for particularly difficult items.

The keyword method is an important tool in my personal language learning toolbox, so I want to share it with you.

How does the keyword method work?

Let’s go step-by-step through an example where a native English speaker wants to learn a German word. The German word for parachute is Fallschirm.

- Pronounce the foreign language word “Fallschirm”. Click here to hear the pronunciation on Leo.org.

- Find a similar sounding keyword or phrase in your own language: Fallschirm sounds a bit like “fall chimp” (a falling chimpanzee). So “falling chimp” becomes my keyword.

- Create an image in your mind, in which you visually connect the keyword (which represents the foreign language word) with its meaning: Imagine a falling chimp who just fell off a cliff. Luckily, he opened his parachute, and is now safely sailing to the ground.

How to recall the meaning when being presented with the foreign language word?

- When you see or hear the word “Fallschirm”, you are likely able to recall the keyword “falling chimp”.

- This in turn should trigger the scene where the chimp fell off a cliff, but was able to open its parachute, and safely sailed to the ground. 🙂 Ah – Fallschirm means parachute.

What is a good keyword?

- A good keyword should have as much sound overlap with the foreign word as possible. So “fall chimp” is better than “fall” or “chimp” alone.

- The keyword should easily lend itself to an image. Compare “fall chimp” with the keyword “false”. “False” is more difficult to visualize, so it is a worse keyword.

- The best keywords have an acoustic and a semantic relationship with the word you want to learn. Again, a “falling chimp” can be easily related to a parachute because parachutes help to slow down falling objects. However, in many cases, it is difficult to come up with a keyword with a related meaning, so don’t get too caught up with this point! It is more important that a keyword is acoustically similar and easily visualized.

How to create a good image?

Make sure that you form an interactive mental image to create a strong visual link between the key word and its meaning. The keyword and its meaning should do something with each other, and not just stand next to each other. In the example above, the chimp opens the parachute and uses it to sail to the ground. The chimp and the parachute interact with each other.

The History of the Keyword Method

Richard C. Atkinson and Michael R. Raugh, who in 1975 published several articles on using the method to learn foreign language vocabulary, coined the term keyword method.

In particular, they conducted experiments in which they had native English speaking subjects learn Spanish and Russian vocabulary using the keyword method. Subjects heard Spanish/Russian words and had to write down their English meaning. The keyword group remembered the meanings for a lot more words compared to the control group. This kind of vocabulary knowledge is called receptive knowledge, that is, you see/hear a word in a foreign language (FL) and are able to recall the meaning in your native language (NL). They also did one experiment where subjects had to produce the Spanish word, given the English equivalent (native language to foreign language) and found the keyword method outperformed rote memorization.

Atkinson and Raugh’s initial experiments with the keyword mnemonic sparked a frenzy of research, which has lasted to this day. For receptive vocabulary learning, the keyword mnemonic has almost always been found to be superior to most control strategies. For productive vocabulary learning, the results are more mixed. Some experiments found the keyword method worked better than other methods, while others suggested that for example retrieval practice is a better method for productive vocabulary learning (i.e. FL- to-NL learning). Some researchers pointed out that the effectiveness of the method for FL-to-NL learning depends a lot on the acoustic overlap between the keyword and the foreign language word.

Personally, I have found the method very helpful for both, productive and receptive vocabulary learning, when used together with pronunciation practice. If you know how to pronounce a foreign language word, the keyword is likely going to be enough to produce the correct pronunciation (given the meaning in your own language). However, if you have never practiced a word before, the keyword won’t be enough to correctly pronounce (or even spell a word). For receptive vocabulary learning it is clear cut to me: The keyword method is the most effective technique I know of.

You have read this far; perhaps my new book might be very helpful for you: It is a practical guide with easy-to-follow examples to help you improve memory and learning. The book contains a whole chapter on vocabulary learning – and much more. Read a sample on Amazon:

Which role does the keyword mnemonic play in my personal arsenal?

Generally, I use spaced retrieval practice with a computer flash card program as my main method to learn new vocabulary. For most words, creating flash cards and testing myself using the automatic scheduling provided by the software work fine, but there are quite a few tough nuts I keep forgetting.

For those, I use the keyword method, which in nearly all cases allows me to memorize my “tough nuts” with confidence. Why don’t I use it for all words? It takes more time and effort to come up with a good keyword and an interactive image than just creating a flash card alone.

At the end of the day, if you want to be an effective language learner, one size doesn’t fit all. For info on other techniques and flash card programs, also read my post Six Tips for More Effective Foreign Language Learning.

I recommend that you try the keyword method. Besides being effective, it is a lot of fun. Just don’t rely on it as your only method, and don’t believe anyone who tells you that with this method you don’t have to practice recalling vocabulary.

In a future post, I am going to describe how to best use the keyword mnemonic for memorizing other information.

Bibliography:

- Atkinson, R. C. 1975. “Mnemotechniques in Second Language Learning.” American Psychologist 30: 821–828.

- Beaton, Alan A, Michael M Gruneberg, Christopher Hyde, Alex Shuffle, and Robert N Sykes. 2005. “Facilitation of Receptive and Productive Foreign Vocabulary Learning Using the Keyword Method: The Role of Image Quality.” Memory (Hove, England) 13 (5) (July): 458–471. doi:10.1080/09658210444000395.

- Fritz, Catherine O., Peter E. Morris, Mandy Acton, Anna R. Voelkel, and Ruth Etkind. 2007. “Comparing and Combining Retrieval Practice and the Keyword Mnemonic for Foreign Vocabulary Learning.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 21 (4): 499–526. doi:10.1002/acp.1287.

- Raugh, Michael R., and Richard C. Atkinson. 1975. “A Mnemonic Method for Learning a Second-Language Vocabulary.” Journal of Educational Psychology 67 (1) (February): 1–16. doi:10.1037/h0078665.

- Van Hell, Janet G., and Andrea Candia Mahn. 1997. “Keyword Mnemonics Versus Rote Rehearsal: Learning Concrete and Abstract Foreign Words by Experienced and Inexperienced Learners.” Language Learning 47 (3) (September): 507–46.

FREE guide of my top productivity hacks for subscribers to my free newsletter

VLearn

independent learning platform on word knowledge and vocabulary building strategies

Mnemonic strategies

Mnemonics strategies are also known as memory strategies. They involve relating words to prior knowledge by using imagery or grouping.

Keyword Method

Keyword method is used when learners relate the target word with their native language. For example, as tuxedo sounds similar to the words 踢死兔 in Cantonese, learners may visualize the word in such a way —

More examples as contributed by speakers of Putonghua/Mandarin:

| English words | Meanings in Chinese | Keywords in Chinese | |

| 1. | ambulance | 救護車 | 俺不能死 |

| 2. | ponderous | 肥胖的 | 胖的要死 |

| 3. | pest | 害蟲 | 拍死它 |

| 4. | ambition | 雄心 | 俺必勝 |

| 5. | agony | 痛苦 | 愛過你 |

| 6. | hermit | 隱士 | 何處覓他 |

| 7. | strong | 強壯 | 死壯 |

| 8. | sting | 蟄 | 死盯 |

| 9. | flee | 逃跑 | 飛離 |

| 10. | morbid | 病態 | 毛病 |

| 11. | tantrum | 脾氣發作 | 太蠢 |

| 12. | bachelor | 學士/單身漢 | 白吃了 |

| 13. | temper | 脾氣 | 太潑 |

| 14. | addict | 上癮 | 愛得嗑它 |

| 15. | economy | 經濟 | 依靠農民 |

Privacy Policy | Disclaimer

Copyright © 2014. All Rights Reserved. Faculty of Education. The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

A keyword mnemonic is an elaborative rehearsal strategy used to help encode information more effectively so that you can easily memorize and recall it. This approach has often been researched and has been shown to be an effective way to teach foreign language vocabulary as well as many other subjects and types of information.

A keyword mnemonic involves two steps.

- First, a keyword that sounds somewhat similar is chosen.

- Second, the learner forms a mental image of that keyword being connected to the new word or piece of information.

An Example

In order to learn the Spanish word for grass, which is pasto, first think of the word pasta (the keyword I’ve chosen) and then imagine pasta noodles growing up out of the grass. When you are asked what the Spanish word for grass is, that should trigger the image of pasta growing up out of the grass and then help you recall the word pasto.

How Effective Are Keyword Mnemonics?

Foreign Language Acquisition

Several studies have been conducted on the use of keyword mnemonics in foreign language acquisition. The learning and recollection of foreign language vocabulary have been repeatedly demonstrated to be superior with the use of the keyword mnemonics method as compared to other methods of study.

Science and History

An interesting study focused on using keyword mnemonics to teach science and history to eighth-grade students. The students were randomly assigned to one of four groups where they practiced one of the following strategies- free study, pegword, a method of loci and keyword. Their task in these groups was to learn specific uses for different types of metal alloys. After testing, the students in the keyword method group performed significantly better than the students in each of the other three groups.

The researchers also wanted to test if the students were able to effectively apply the mnemonic strategy to a different area of information. The students were given Revolutionary War facts to learn, and once again, those in the keyword strategy group significantly outperformed the other students in their ability to recall the information.

Keyword Mnemonics With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Early Dementia

Minimal research, if any, has been conducted on using the keyword mnemonic method to improve recall in people with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage dementia.

There have, however, been studies conducted on the use of mnemonic strategies in general for those with mild cognitive impairment. These studies have shown that mnemonic methods can improve the ability to learn and recall information, as well as the activity levels in the hippocampus, of people with MCI.

Verywell Health uses only high-quality sources, including peer-reviewed studies, to support the facts within our articles. Read our editorial process to learn more about how we fact-check and keep our content accurate, reliable, and trustworthy.

-

Anari FK, Sajjadi M, Sadighi F. The magic of mnemonics for vocabulary learning of a second language. Int J Lang Linguist. 2015; 3(1-1): 1-6. doi:10.11648/j.ijll.s.2015030101.11

-

Richmond AS, Cummings R, Klapp M. Transfer of the method of loci, pegword, and keyword mnemonics in the eighth-grade classroom. Researcher. 2008;21(3).

-

Hampstead BM, Stringer AY, Stilla RF, Sathian K. Mnemonic strategy training increases neocortical activation in healthy older adults and patients with mild cognitive impairment. Int J Psychophysiol. 2020;154:27-36. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2019.04.011

Additional Reading

By Esther Heerema, MSW

Esther Heerema, MSW, shares practical tips gained from working with hundreds of people whose lives are touched by Alzheimer’s disease and other kinds of dementia.

Thanks for your feedback!

Keyword method — Schlüsselwortmethode

The keyword method , substitute word method or keyword method is a mnemonic method to learn vocabulary efficiently and over the long term.

construction

The memory or the memory technique is based on the association of the old with the new. In addition, the brain can remember images and impressive ideas better than abstract learning material. The keyword method is based on various brain-friendly principles:

- New vocabulary is linked to existing knowledge.

- Abstract and unknown material is transformed into easily imaginable images.

- There is a mental processing and a conscious confrontation with the new knowledge.

functionality

A word from the mother tongue that sounds similar to the vocabulary being learned is the key word. An image is created in the mind from the key word and the meaning of the word. However, the keywords can come from any other language, even from the target language itself.

Examples

- engl. mice — mice

- Many mice nibble on a large cob of corn. (Corn is the key word)

- franz. chien — dog

- A dog is racing downhill on skis. (Ski is the key word)

- engl. bile — Galle

- an angry man who is overflowing with bile rages around with an ax in his hand. (Hatchet is the key word)

effectiveness

The keyword method has been tested in several studies. According to Atkinson and Raugh (1975), the more similar the language to be learned is to the mother tongue, the greater the effectiveness of the method. They had American students study 40 Russian vocabulary each for three days. On the fourth day, all 120 words were asked again. The group that had learned using the keyword or substitute word method remembered 72% of the vocabulary compared to 46% in the control group. Even with an unannounced test after 43 days, the memory performance was significantly higher at 43% than in the control group at 28%. In similar studies with Spanish words, Atkinson and Raugh (1975) found even more pronounced differences (88% in the keyword group versus 28% in the control group). More recent studies by Lawson et al. Hogben 1998 confirmed the effectiveness of the substitute word method in learning vocabulary. The method also proved to be effective for learning facts (Brigham and Brigham 1998, Dretzke and Levin 1990, Levin et al. 1983 and 1983).

Memorize entire dictionaries

The memory grandmaster Yip Swe Choi memorized an entire dictionary ( Mandarin , English ) with over 58,000 entries and more than 1,700 pages using the keyword method . He can not only say the corresponding translation for each word from one of the two languages, but also knows the exact definition in the national language, the page number and the place on the page where the word is.

Choi also used the loci method for this memory performance . He has a mental route with over 58,000 points on which he stores the respective vocabulary.

literature

- Gunther Karsten: Success Memory , Munich 2002, ISBN 3-442-39035-4 , 177 ff.

- Werner Metzig, Martin Schuster: Learning to learn , Springer Berlin Heidelberg New York 2006, ISBN 3-540-26030-7 , 74ff

- Oliver Geisselhart and Helmut Lange: «Schieb das Schaf», Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-86882-258-8

See also

- Brandspruch

Weblinks

- Dr. Jörn Hauptmann, The Effects of the integrated Keyword Method on Vocabulary Retention and Motivation — Dissertation on the effects of the keyword method

- Information on the keyword method of the initiative learn-today

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Esther-Heerema-MSW-1000-e5257556bb40418ebee7e4b1c7a99420.jpg)