The growth

of the E. vocabulary from internal sources – through word-formation

and semantic change – can be observed in all periods of history. In

the 15-17th

c. its role became more important though the influx of borrowings

from other languages continued. Word formation fell into 2 types:

Word derivation and word

composition.

The means of derivation used in

OE continued to be employed in later periods: Suffixation, the most

productive way: most of the OE product. Suffixes have survived, many

– added from internal and external sources.

Prefixation was less productive

in ME, but later, in Early NE its productivity grew again.

Many OE prefixes dropped out of

use: a-,tō-,on-,of-,ze-,or-. In some words the prefix fused with the

root:OE on-zinna > ME ginnen > NE begin. The negative prefixes

mis- & un- produced a great number of new words:ME mislayen,

misdemen(NE mislay, misjudge). OE un- was mainly used with nouns and

adjectives: Early NE: unhook, unload.

Also, foreign prefixes were

adopted by the English lang. as component parts of loan-words:re-,

de-, dis-. Sound interchanges and the shifting of word stress were

mainly employed as a means of word differentiation, rather than as a

word-building means.

47.

Spelling

changes in ME and NE. Rules of reading.

The most conspicuous feature of

Late ME texts in comparison with OE texts is the difference in

spelling. The written forms in ME resemble modern forms, though the

pronunciation was different.

— In ME the runic letters

passed out of use. Thorn “ђ” and the crossed d: “đ” were

replaced by the digraph –th-, which retained the same sound value:

[Ө] & [ð]; the rune “wynn” was displaced by “double u”:

-w-;the ligatures æ & œ fell into disuse.

— Many innovations reveal an

influence of the French scribal tradition. The digraphs ou, ie &

ch were adopted as new ways of indicating the sounds [u:], [e:] &

[t∫] : e.g. OE ūt, ME out [u:t]; O Fr double, ME double [duble].

— The letters j,k,v,q were

first used in imitation of French manuscripts.

— The two-fold use of –g- &

-c- owes its origin to French: these letters usually stood for [dz] &

[s] before front vowels & for [g]&[k] before back vowels: ME

gentil [dzen’til], mercy [mer’si] & good[go:d].

— A wider use of digraphs: -sh-

is introduced to indicate the new sibilant [∫]: ME ship(from OE

scip); -dz- to indicate [dz]: ME edge [‘edze], joye [‘dzoiə];

the digraph –wh- replaced –hw-: OE hwæt, ME what [hwat].

— Long sounds were shown by

double letters: ME book [bo:k]

— The introduction of the

digraph –gh- for [x]& [x’]: ME knight [knix’t] & ME he

[he:].

— Some replacements were made

to avoid confusion of resembling letters: “o” was employed to

indicate “u”: OE munuc > ME monk; lufu > love. The letter

“y” – an equivalent og “i” : very, my [mi:].

48.Development of the syntactic system in me and early ne.

The

evolution of English syntax was tied up with profound changes in

morphology: the decline of the inflectional system was accompanied by

the growth of the functional load of syntactic means of word

connection. The most obvious difference between OE syntax and the

syntax of ME and NE periods is that the word order became more strict

and the use of prepositions more extensive. The growth of the

literary forms of the language, the literary flourishing in Late ME

and especially in the age of the Renaissance the differentiation of

literary styles and the efforts made by 18th

c. scholars to develop a logical, elegant style — all contributed to

the improvement and perfection of English syntax. The structure of

the sentence and word phrase, on the one hand, became more

complicated , on the other hand- were stabilized and standardized.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

By Creating from Scratch

Many of the new words added to the ever-growing lexicon of the English language are just created from scratch, and often have little or no etymological pedigree. A good example is the word dog, etymologically unrelated to any other known word, which, in the late Middle Ages, suddenly and mysteriously displaced the Old English word hound (or hund) which had served for centuries. Some of the commonest words in the language arrived in a similarly inexplicable way (e.g. jaw, askance, tantrum, conundrum, bad, big, donkey, kick, slum, log, dodge, fuss, prod, hunch, freak, bludgeon, slang, puzzle, surf, pour, slouch, bash, etc).

Words like gadget, blimp, raunchy, scam, nifty, zit, clobber, boffin, gimmick, jazz and googol have all appeared in the last century or two with no apparent etymology, and are more recent examples of this kind of novel creation of words. Additionally, some words that have existed for centuries in regional dialects or as rarely used terms, suddenly enter into popular use for little or no apparent reason (e.g. scrounge and seep, both old but obscure English words, suddenly came into general use in the early 20th Century).

Sometimes, if infrequently, a «nonce word» (created «for the nonce», and not expected to be re-used or generalized) does become incorporated into the language. One example is James Joyce’s invention quark, which was later adopted by the physicist Murray Gell-Mann to name a new class of sub-atomic particle, and another is blurb, which dates back to 1907.

By Adoption or Borrowing

Loanwords, or borrowings, are words which are adopted into a native language from a different source language. Such borrowings have shaped the English language almost from its beginnings, as words were adopted from the classical languages as well as from successive wave of invasions (e.g. Vikings, Normans). Even by the 16th Century, long before the British Empire extended its capacious reach around the world, English had already adopted words from an estimated 50 other languages, and the vast majority of English words today are actually foreign borrowings of one sort or another.

Sometimes these adoptions have come by a circuitous route (e.g. the word orange originated with the Sanskrit naranj or naranga or narangaphalam or naragga, which became the Arabic naranjah and the Spanish naranja, entered English as a naranj, changed to a narange, then to an arange and finally an orange; the word garbage came to English originally from Latin, but only arrived via Old Italian, an Italian dialect and then Norman French). Sometimes the tortuous route and degrees of filtering through other languages can modify words so much that their original derivations are all but indiscernible (e.g. both coy and quiet come from the Latin word quietus; sordid and swarthy both come from the Latin sordere; entirety and integrity both derive from the Latin integritas; salary and sausage both originate with the Latin word sal; grammar and glamour are both descended from the same Greek word gramma; and gentle, gentile, genteel and jaunty all come from the Latin gentilis; etc).

Since the expansion of global trade, and particularly since British colonialism opened up rich new sources (see the page on Late Modern English), a huge number of words have been adopted into English from a great diversity of different languages. In a reverse process, many English words have also been adopted by other countries (see the section on Reverse Loanwords in English Today).

By Adding Prefixes and Suffixes

The ability to add affixes, whether prefixes (e.g. com-, con-, de-, ex-, inter-, pre-, pro-, re-, sub-, un-, etc) and suffixes (e.g. -al, -ence, -er, -ment, -ness, -ship, -tion, -ate, -ed, -ize, -able, -ful, -ous, -ive, -ly, -y, etc) makes English extremely flexible. This process, referred to as agglutination, is a simple way to completely alter or subtly revise the meanings of existing words, to create other parts of speech out of words (e.g. verbs from nouns, adverbs form adjectives, etc), or to create completely new words from new roots. There are very few rules in the addition of affixes in English, and Anglo-Saxon affixes can be attached to Latin or Greek roots, or vice versa. An extreme example is the word incomprehensibility, which is based on the simple root -hen- (original from Indo-European root word ghend- meaning to grasp or seize) with no less than 5 affixes: in- (not), com- (with), pre- (before), -ible (capable) and -ity (being).

However, the sheer variety and number of possible affixes in English can lead to some confusion. For instance, there is no single standard method for something as basic as making a noun into an adjective (-able, -al, -ous and -y are just some of the possibilities). There are at least nine different negation prefixes (a-, anti-, dis-, il-, im-, in-, ir-, non- and un-), and it is almost impossible for a non-native speaker to predict which is to be used with which root word. To make matters worse, some apparently negative forms do not even negate the meanings of their roots (e.g. flammable and inflammable, habitable and inhabitable, ravel and unravel).

Some affix additions are surprisingly recent. Officialdom and boredom joined the ancient word kingdom as recently as the 20th Century, and apolitical as the negation of political did not appear until 1952. Adding affixes remains the simplest and perhaps the commonest method of creating new words.

By Truncation or Clipping

Some words arise simply as shortened forms of longer words (exam, gym, lab, bus, van, vet, fridge, bra, wig, curio, pram, taxi, rifle, canter, phone and burger are some obvious and well-used examples). Perhaps less obvious is the derivation of words like mob (from the Latin phrase mobile vulgus, meaning a fickle crowd), goodbye (a shortening of God-be-with-you) and hello (a shortened form of the Old English for “whole be thou”).

Leaving aside the common English practice of contracting multiple words like do not, you are, there will and that would into the single words don’t, you’re, there’ll and that’d, there are many other examples where multiple words or phrases have been contracted into single words (e.g. daisy was once a flower called day’s eye; shepherd was sheep herd; lord was originally loaf-ward; fortnight was fourteen-night; etc).

Acronyms are another example of this technique. While most acronyms (e.g. USA, IMF, OPEC, etc) remain as just a series of initial letters, some have been formed into words (e.g. laser from light amplification by stimulated emmission of radiation, radar from radio detection and ranging); quasar from quasi-stellar radio source; scuba from self-contained underwater breathing apparatus; etc).

By Fusing or Compounding Existing Words

Like many languages, English allows the formation of compound words by fusing together shorter words (e.g. airport, seashore, fireplace, footwear, wristwatch, landmark, flowerpot, etc), although it is not taken to the extremes of German or Dutch where extremely long and unwieldy word chains are commonplace. The concatenation of words in English may even allow for different meanings depending on the order of combination (e.g. houseboat/boathouse, basketwork/workbasket, casebook/bookcase, etc).

The root words may be run together with no separation (as in the examples above), or they may be hyphenated (e.g. self-discipline, part-time, mother-in-law) or even left as separate words (e.g. fire hydrant, commander in chief), although the rules for such constructions are unclear at best.

During the English Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution, compounding classical elements of Greek and Latin (e.g. photograph, telephone, etc) was a very common method of English word formation, and the process continues even today. A large part of the scientific and technical lexicon of English consists of such classical compounds.

Sometimes words or phonemes are blended rather than combined whole, forming a «portmanteau word» with two meanings packed into one word, or with a meaning intermediate between the two constituent words (e.g. brunch, which blends breakfast and lunch; motel, which blends motor and hotel; electrocute, which blends electric and execute; smog, which blends smoke and fog; guesstimate, which blends guess and estimate; telethon, which blends telephone and marathon; chocoholic, which blends chocolate and alcoholic; etc). Lewis Carroll was perhaps the first to deliberately use this technique for literary effect, when he introduced new words like slithy, frumious, galumph, etc, in his poetry in the 19th Century.

By Changing the Meaning of Existing Words

The drift of word meanings over time often arises, often but not always due to catachresis (the misuse, either deliberate or accidental, of words). By some estimates, over half of all words adopted into English from Latin have changed their meaning in some way over time, often drastically. For example, smart originally meant sharp, cutting or painful; handsome merely meant easily-handled (and was generally derogatory); bully originally meant darling or sweetheart; sad meant full, satiated or satisfied; and insult meant to boast, brag or triumph in an insolent way. A more modern example is the changing meaning of gay from merry to homosexual (and, in some circles in more recent years, to stupid or bad).

Some words have changed their meanings many times. Nice originally meant stupid or foolish; then, for a time, it came to mean lascivious or wanton; it then went through a whole host of alternative meanings (including extravagant, elegant, strange, slothful, unmanly, luxurious, modest, slight, precise, thin, shy, discriminating and dainty), before settling down into its modern meaning of pleasant and agreeable in the late 18th Century. Conversely, silly originally meant blessed or happy, and then passed through intermediate meanings of pious, innocent, harmless, pitiable, feeble and feeble-minded, before finally ending up as foolish or stupid. Buxom originally meant obedient to God in Middle English, but it passed through phases of meaning humble and submissive, obliging and courteous, ready and willing, bright and lively, and healthy and vigorous, before settling on its current very specific meaning relating to a plump and well-endowed woman.

Some words have become much more specific than their original meanings. For instance, starve originally just mean to die, but is now much more specific; a forest was originally any land used for hunting, regardless of whether it was covered in trees; deer once referred to any animal, not just the specific animal we now associate with the word; girl was once a young person of either sex; and meat originally covered all kinds of food (as in the phrase “meat and drink”).

Some words came to mean almost the complete opposite of their original meanings. For instance, counterfeit used to mean a legitimate copy; brave once implied cowardice; crafty was originally a term of praise; cute used to mean bow-legged; enthusiasm and zeal were both once disparaging words; manufacture originally meant to make by hand; awful meant deserving of awe; egregious originally connoted eminent or admirable; artificial was a positive description meaning full of skilful artifice; etc.

A related category is where an existing word comes to be used with another grammatical function, often a different part of speech, a process known as functional shift. Examples include: the creation of the nouns a commute, a bore and a swim from the original verbs to commute, to bore and to swim; the creation of the verbs to bottle, to catalogue and to text from the original nouns bottle, catalogue and text; the creation of the verbs to dirty, to empty and to dry from the original adjectives dirty, empty and dry, etc. Modern language purists often condemn such developments, although they have occurred throughout the history of English, and in some cases may even reclaim the original sense of a word (e.g. impact was originally introduced as a verb, then established itself predominantly as a noun, and has only recently begun to be used a verb once more).

By Errors

According to the “Oxford English Dictionary”, there are at least 350 words in English dictionaries (most of them thankfully quite obscure) that owe their existence purely to typographical errors or other misrenderings.

There are many more words, often in quite common use, that have arisen over time due to mishearings (e.g. shamefaced from the original shamefast, penthouse from pentice, sweetheart from sweetard, buttonhole from button-hold, etc).

Mrs. Mapalprop, a character in Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s 1775 play «The Rivals», was famous for her «malapropisms» like illiterate, reprehend, etc, but these never gained common currency. Likewise, it seems unlikely that «Bushisms» (named for US President Bush’s unfortunate tendency to mangle the language) like misunderestimate, or Sarah Palin’s refudiate will ever become part of the everyday language, although there are many who would argue that they deserve to.

Many misused words (as opposed to newly-coined words) have, for better or worse, become so widely used in their new context that they may be considered to be generally accepted, particularly in the USA, although many strict grammarians insist on their distinctness (e.g. alternate to mean alternative, momentarily to mean presently, disinterested to mean uninterested, i.e. to mean e.g., flaunt to mean flout, historic to mean historical, imply to mean infer, etc).

By Back-Formation

Some words are “back-formed”, where a new word is formed by removing an actual, or often just a supposed or incorrectly identified, affix. A good example of back-formation is the old word pease, which was mistakenly assumed to be a plural, and thus led to the creation of a new “singular” word, pea. Similarly, asset was back-formed from the singular noun assets (originally from the Anglo-Norman asetz).

More often, though, a new word for a different part of speech is derived form an older form (e.g. laze from lazy, beg from beggar, greed from greedy, rove from rover, burgle from burglar, edit from editor, difficult from difficulty, resurrect from resurrection, insert from insertion, project from projection, grovel from groveling, sidle from sideling or sidelong, etc).

By Imitation of Sounds

Words may be formed by the deliberate imitation of sounds they describe (onomatopoeia). Often this kind of onomatopoeic formation is surprisingly ancient, and Old English literature is usually described as highly onomatopoeic, alliterative and percussive. Sometimes, the imitation may have originally occurred in a source language, and only later borrowed into English, and by its very nature sound imitation tends to result in similar cognates in several languages. Some philologists have suggested that the first human languages developed as imitations of natural sounds (so-called «bow-wow theories»), and imitative abilities certainly seem to have played some role in the evolution of language.

Examples include boo, bow-wow, tweet, boom, tinkle, rattle, buzz, click, hiss, bang, plop, cuckoo, quack, beep, etc, but there are many many more. Some words, like squirm for example, are not strictly onomatopoeic but are nevertheless imitative to some extent (e.g like a worm)

By Transfer of Proper Nouns

A surprising number of words have been created by the transfer of the proper names of people, places and things into words which then become part of the generalized vocabulary of the language, also known as eponyms. Examples include maverick (after the American cattleman, Samuel Augustus Maverick); saxophone (after the Belgian musical-instrument maker, Adolphe Sax); quisling (after the pro-Nazi Norwegian leader, Vidkun Quisling); sandwich (after the fourth Earl of Sandwich); silhouette (after the French finance minister, Etienne de Silhouette); kafkaesque (after the Czech novelist, Franz Kafka); quixotic (after the romantic, impractical hero of a Cervantes novel); boycott (after Charles Boycott, the shunned Irish land agent for an absentee landlord); etc. Other common eponyms include biro, bloomers, boffin, chauvinism, diesel, galvanize, guillotine, leotard, lesbian, lynch, marathon, mesmerize, svengali, mentor, odyssey, atlas, sadism, shrapnel, spartan, teddy, wellington, etc, as well as some less obvious ones like panic, maudlin, dunce, bugger, currant, tawdry, doily and hooligan.

Many terms for political, philosophical or religious doctrines are based on the names of their founders or chief exponents (e.g. Marxism, Aristotelianism, Platonic, stoic, Christianity, etc). Similarly, many scientific terms and units of measurement are named after their inventors (e.g. ampere, angstrom, joule, watt, etc).> Increasingly, in the 20th Century, specific brand names have become generalized descriptions (e.g. hoover, kleenex, xerox, aspirin, google, etc).

Sometimes, portmanteau words (see Fusing and Compounding Words above) may be produced by joining together proper nouns with common nouns, such as in the case of gerrymandering, a word combining the politically-contrived re-districting practices of Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry with the salamander-shaped outline one of the districts he created.

In this section

In linguistics (particularly morphology and lexicology), word formation refers to the ways in which new words are formed on the basis of other words or morphemes. This is also known as derivational morphology.

Word formation can denote either a state or a process, and it can be viewed either diachronically (through different periods in history) or synchronically (at one particular period in time).

In The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, David Crystal writes about word formations:

«Most English vocabulary arises by making new lexemes out of old ones — either by adding an affix to previously existing forms, altering their word class, or combining them to produce compounds. These processes of construction are of interest to grammarians as well as lexicologists. … but the importance of word-formation to the development of the lexicon is second to none. … After all, almost any lexeme, whether Anglo-Saxon or foreign, can be given an affix, change its word class, or help make a compound. Alongside the Anglo-Saxon root in kingly, for example, we have the French root in royally and the Latin root in regally. There is no elitism here. The processes of affixation, conversion, and compounding are all great levelers.»

Processes of Word Formation

Ingo Plag explains the process of word formation in Word-Formation in English:

«Apart from the processes that attach something to a base (affixation) and processes that do not alter the base (conversion), there are processes involving the deletion of material. … English Christian names, for example, can be shortened by deleting parts of the base word (see (11a)), a process also occasionally encountered with words that are not personal names (see (11b)). This type of word formation is called truncation, with the term clipping also being used.»

(11a) Ron (-Aaron)

(11a) Liz (-Elizabeth)

(11a) Mike (-Michael)

(11a) Trish (-Patricia)

(11b) condo (-condominium)

(11b) demo (-demonstration)

(11b) disco (-discotheque)

(11b) lab (-laboratory)

«Sometimes truncation and affixation can occur together, as with formations expressing intimacy or smallness, so-called diminutives:»

(12) Mandy (-Amanda)

(12) Andy (-Andrew)

(12) Charlie (-Charles)

(12) Patty (-Patricia)

(12) Robbie (-Roberta)

«We also find so-called blends, which are amalgamations of parts of different words, such as smog (smoke/fog) or modem (modulator/demodulator). Blends based on orthography are called acronyms, which are coined by combining the initial letters of compounds or phrases into a pronounceable new word (NATO, UNESCO, etc.) Simple abbreviations like UK or USA are also quite common.»

Academic Studies of Word-Formation

In the preface to the Handbook of Word-Formation, Pavol Stekauer and Rochelle Lieber write:

«Following years of complete or partial neglect of issues concerning word formation (by which we mean primarily derivation, compounding, and conversion), the year 1960 marked a revival—some might even say a resurrection—of this important field of linguistic study. While written in completely different theoretical frameworks (structuralist vs. transformationalist), both Marchand’s Categories and Types of Present-Day English Word-Formation in Europe and Lee’s Grammar of English Nominalizations instigated systematic research in the field. As a result, a large number of seminal works emerged over the next decades, making the scope of word-formation research broader and deeper, thus contributing to better understanding of this exciting area of human language.»

In «Introduction: Unravelling the Cognitive in Word Formation.» Cognitive Perspectives on Word Formation, Alexander Onysko and Sascha Michel explain:

«[R]ecent voices stressing the importance of investigating word formation in the light of cognitive processes can be interpreted from two general perspectives. First of all, they indicate that a structural approach to the architecture of words and a cognitive view are not incompatible. On the contrary, both perspectives try to work out regularities in language. What sets them apart is the basic vision of how language is encapsulated in the mind and the ensuing choice of terminology in the description of the processes. … [C]ognitive linguistics concedes closely to the self-organizing nature of humans and their language, whereas generative-structuralist perspectives represent external boundaries as given in the institutionalized order of human interaction.»

Birth and Death Rates of Words

In their report «Statistical Laws Governing Fluctuations in Word Use from Word Birth to Word Death,» Alexander M. Petersen, Joel Tenenbaum, Shlomo Havlin, and H. Eugene Stanley conclude:

«Just as a new species can be born into an environment, a word can emerge in a language. Evolutionary selection laws can apply pressure on the sustainability of new words since there are limited resources (topics, books, etc.) for the use of words. Along the same lines, old words can be driven to extinction when cultural and technological factors limit the use of a word, in analogy to the environmental factors that can change the survival capacity of a living species by altering its ability to survive and reproduce.»

Sources

- Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Onysko, Alexander, and Sascha Michel. “Introduction: Unravelling the Cognitive in Word Formation.” Cognitive Perspectives on Word Formation, 2010, pp. 1–26., doi:10.1515/9783110223606.1.

- Petersen, Alexander M., et al. “Statistical Laws Governing Fluctuations in Word Use from Word Birth to Word Death.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 15 Mar. 2012, www.nature.com/articles/srep00313.

- Plag, Ingo. Word-Formation in English. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Stekauer, Pavol, and Rochelle Lieber. Handbook of Word-Formation. Springer, 2005.

Слайд 1LECTURE 4

WORD STRUCTURE AND WORD FORMATION

www.philology.bsu.by/кафедры/кафедра английского языкознания/учебные материалы/кафедра английского языкознания/папки

преподавателей/Толстоухова В.Ф.

LEXICOLOGY COURSE

Слайд 2The questions under consideration

1. Morpheme. Allomorph

2. Word Structure

3. Immediate Constituents Analysis

4.

Affixation

5. Conversion

6. Word-Composition

6.1. Properties of compounds

7. Other Types of Word Formation

Слайд 3Word-formation (definition)

Word-formation is the branch of lexicology that studies

the derivative

structure of existing words and

the patterns on which a language builds new words.

It is a certain principle of classification of lexicon and

one of the main ways of enriching the vocabulary.

Слайд 4Word-formation is studied

synchronically

Scholars investigate the existing system of the types

of word-formation

Diachronically

Scholars investigate the history of word-formation

Слайд 51. Morpheme. Allomorph

The smallest unit of language that carries information about

meaning or function is the morpheme.

(Greek morphe «form»

+ -eme «the smallest distinctive unit»)

Слайд 6Examples of morphemes

BUILD+ER

build (with the meaning of «construct»)

-er (which indicates that

the entire word functions as a noun with the meaning «one who builds»).

HOUSE+S

house (with the meaning of «dwelling»)

-s (with the meaning «more than one»)

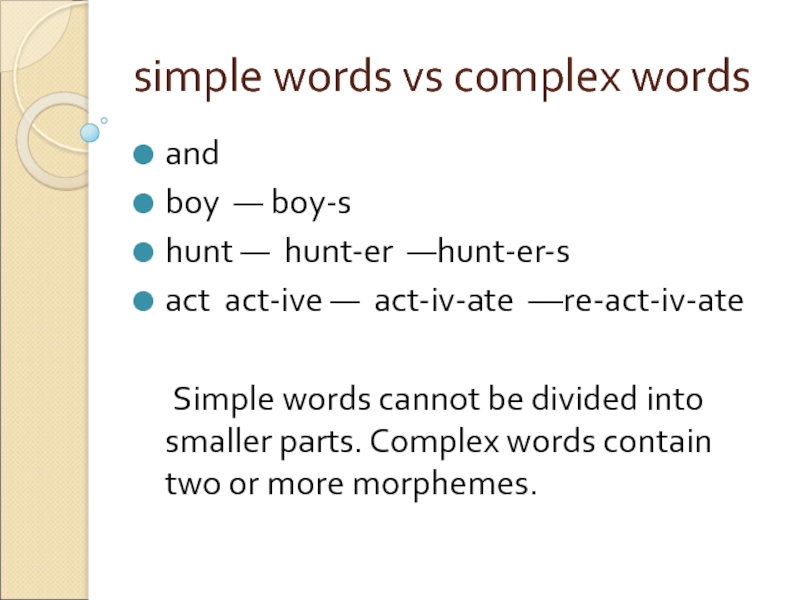

Слайд 7simple words vs complex words

and

boy — boy-s

hunt — hunt-er

—hunt-er-s

act act-ive — act-iv-ate ––re-act-iv-ate

Simple words cannot be divided into smaller parts. Complex words contain two or more morphemes.

Слайд 8morphemes are two-facet language units

A morpheme is a meaning and a

stretch of sound joined together.

It is the minimum meaningful language unit.

Слайд 9Structure of morphemes

free morpheme

(can be a word by itself,

coincides with the stem or a word-form)

bound morpheme

(must be attached to another element,

only can be a part of a word )

Слайд 10allomorphs (from Greek allos «other»)

All the representatives of the given

morpheme are called allomorphs of that morpheme.

An allomorph is a positional variant of that or this morpheme occurring in a specific environment.

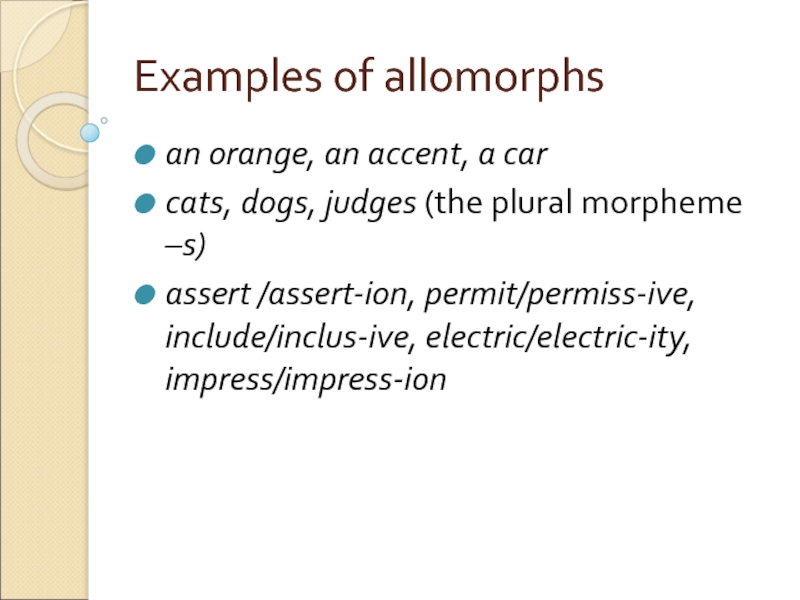

Слайд 11Examples of allomorphs

an orange, an accent, a car

cats, dogs, judges

(the plural morpheme –s)

assert /assert-ion, permit/permiss-ive, include/inclus-ive, electric/electric-ity, impress/impress-ion

Слайд 122. Word Structure

Words that can be divided have two or more

parts:

a root

affixes (a prefix, a suffix )

inflection

Слайд 13Word Structure

A root constitutes the core of the word and carries

the major component of its meaning. It has more specific and definite meaning

Affixes are morphemes that modify the meaning of the root. An affix added before the root is called a prefix (un-ending); an affix added after the root is called a suffix (kind-ness).

Слайд 14Examples of word structure

un-work-able

govern-ment

fright-en-ing

re-play

A word may have one or more affixes

of either kind, or several of both kinds.

Слайд 15A base

A base is the form to which an affix

is added. In many cases, the base is also the root. In other cases, however, the base can be larger than a root.

Blackened

Blacken (verbal base) +ed

Blacken

Black (not only the root for the entire word but also the base for) +en

Слайд 16suffixes vs inflections

Suffixes can form a new part of speech,

e.g.: beauty — beautiful. They can also change the meaning of the root, e.g.: black — blackish.

Inflections are morphemes used to change grammar forms of the word, e.g.: work — works — worked—working. English is not a highly inflected language.

Слайд 17Four structural types of words in English

simple (root) words consist

of one root morpheme and an inflexion (boy, warm, law, tables, tenth);

derived words consist of one root morpheme, one or several affixes and an inflexion (unmanageable, lawful);

compound words consist of two or more root morphemes and an inflexion (boyfriend, outlaw);

compound-derived words consist of two or more root morphemes, one or more affixes and an inflexion (left-handed, warm-hearted, blue-eyed).

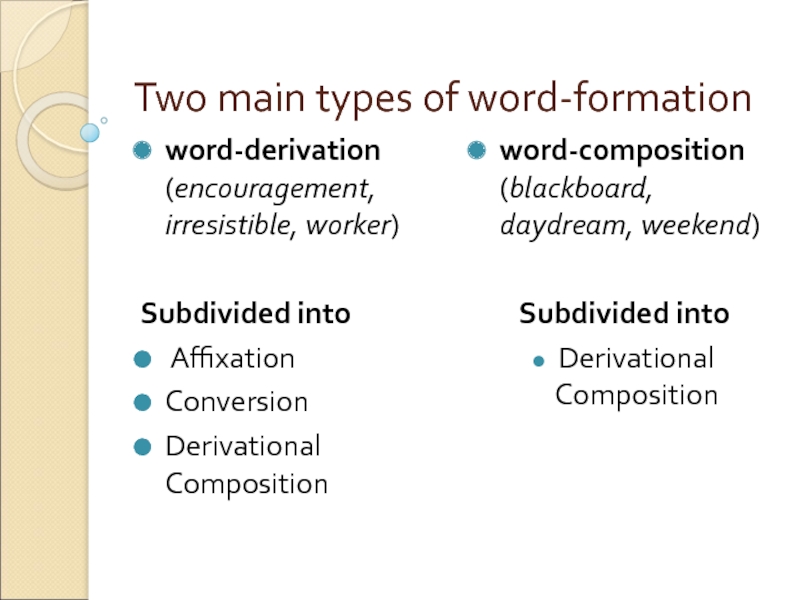

Слайд 18Two main types of word-formation

word-derivation (encouragement, irresistible, worker)

Subdivided into

Affixation

Conversion

Derivational Composition

word-composition (blackboard, daydream, weekend)

Subdivided into

Derivational Composition

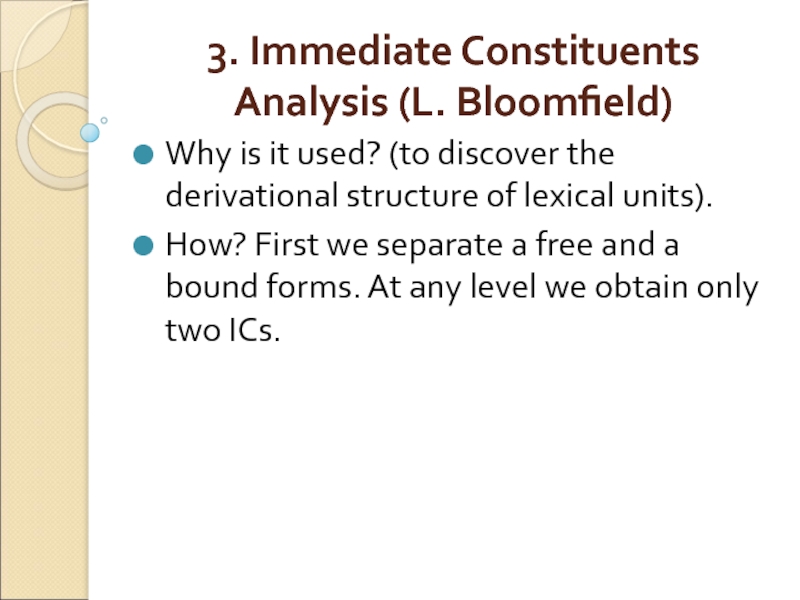

Слайд 193. Immediate Constituents Analysis (L. Bloomfield)

Why is it used? (to

discover the derivational structure of lexical units).

How? First we separate a free and a bound forms. At any level we obtain only two ICs.

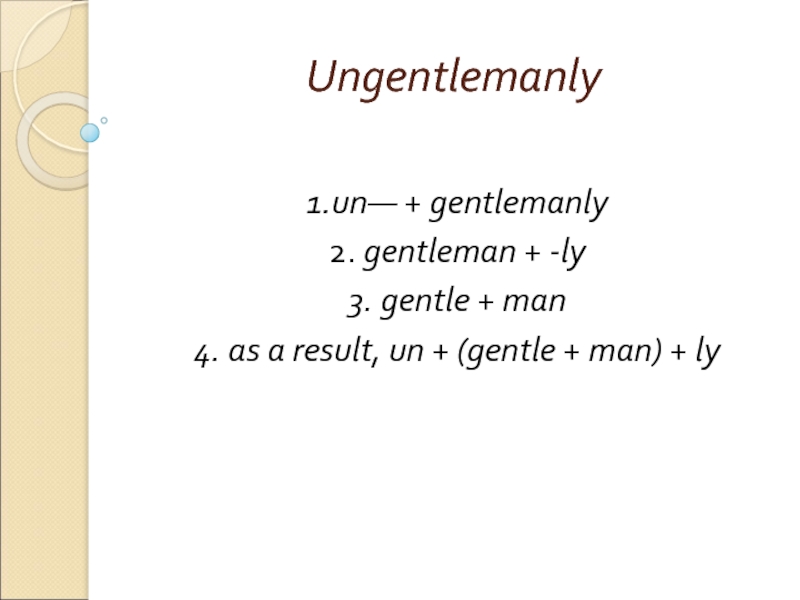

Слайд 20Ungentlemanly

1.un— + gentlemanly

2. gentleman + -ly

3. gentle + man

4.

as a result, un + (gentle + man) + ly

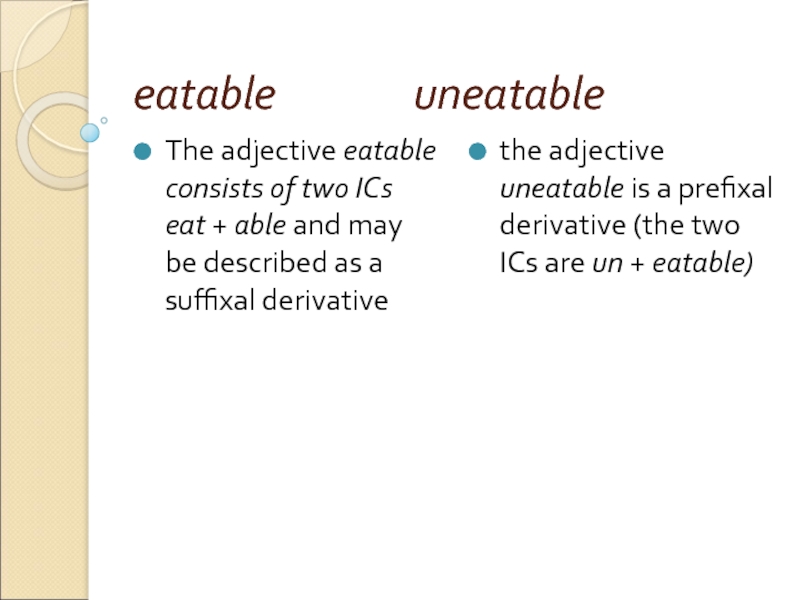

Слайд 21eatable uneatable

The adjective eatable consists of two ICs eat + able

and may be described as a suffixal derivative

the adjective uneatable is a prefixal derivative (the two ICs are un + eatable)

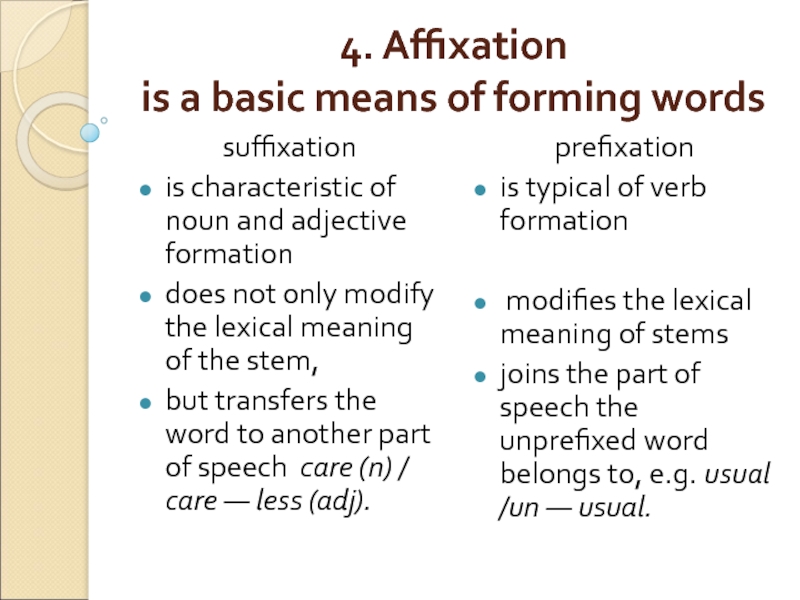

Слайд 224. Affixation

is a basic means of forming words

suffixation

is characteristic of

noun and adjective formation

does not only modify the lexical meaning of the stem,

but transfers the word to another part of speech care (n) / care — less (adj).

prefixation

is typical of verb formation

modifies the lexical meaning of stems

joins the part of speech the unprefixed word belongs to, e.g. usual /un — usual.

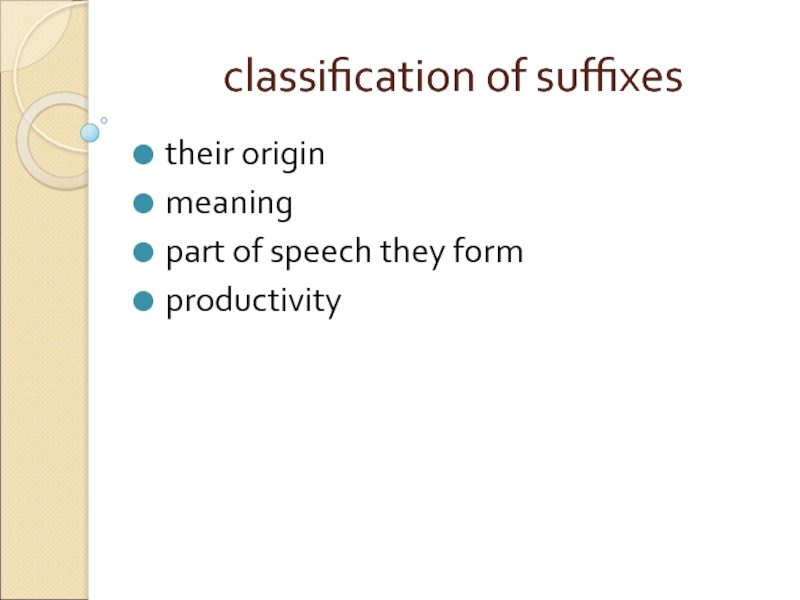

Слайд 23classification of suffixes

their origin

meaning

part of speech they form

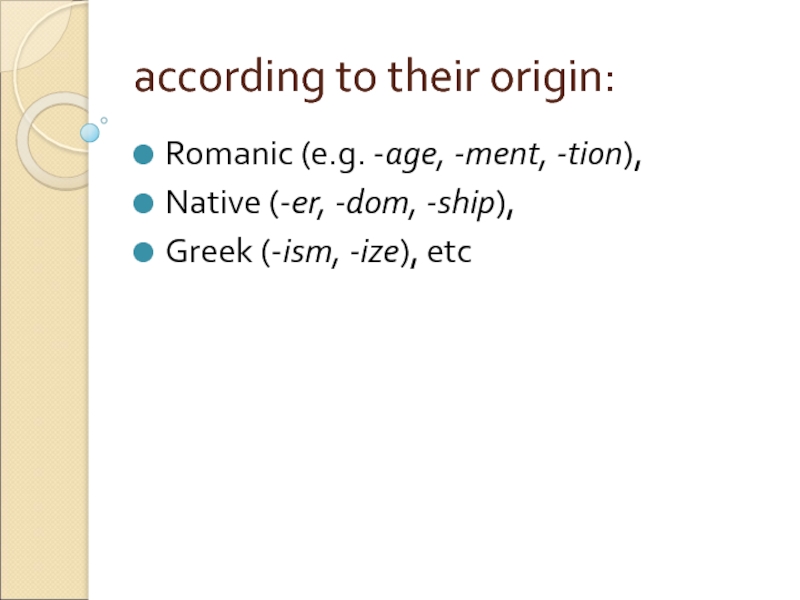

Слайд 24according to their origin:

Romanic (e.g. -age, -ment, -tion),

Native (-er, -dom,

-ship),

Greek (-ism, -ize), etc

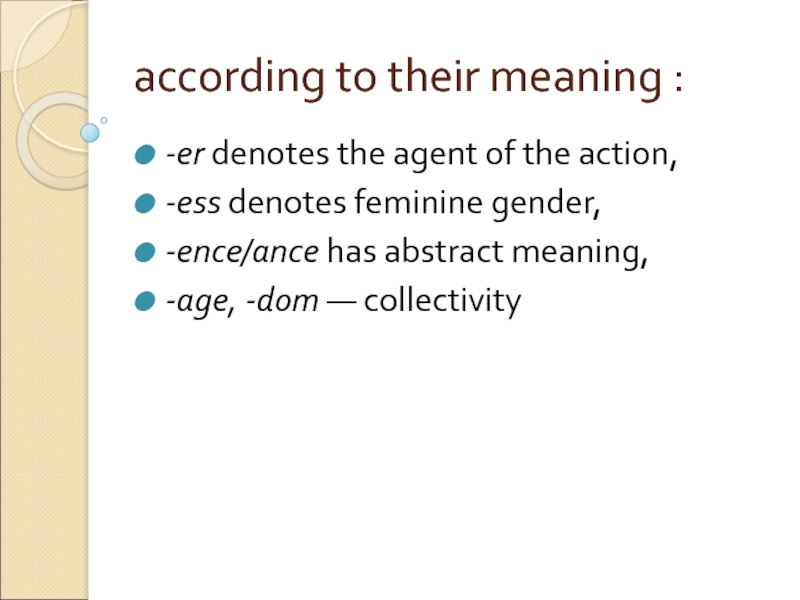

Слайд 25according to their meaning :

-er denotes the agent of the action,

-ess denotes feminine gender,

-ence/ance has abstract meaning,

-age, -dom — collectivity

Слайд 26according to their part of speech they form :

noun suffixes -er,

-ness, -ment;

adjective-forming suffixes -ish, -ful, -less, -y;

verb-suffixes -en, -fy,

Слайд 27according to their productivity :

What is productivity? It is the relative

freedom with which they can combine with bases of the appropriate category

productive suffixes are -er, -ly, -ness, -ie, -let,

non-productive (-dom, -th)

semi-productive (-eer, -ward).

Слайд 28Classification of Prefixes

their origin

meaning

productivity

Слайд 29according to their origin:

Native, e.g. un-;

Romanic, e.g. in-;

Greek,

e.g. sym-;

Слайд 30according to meaning

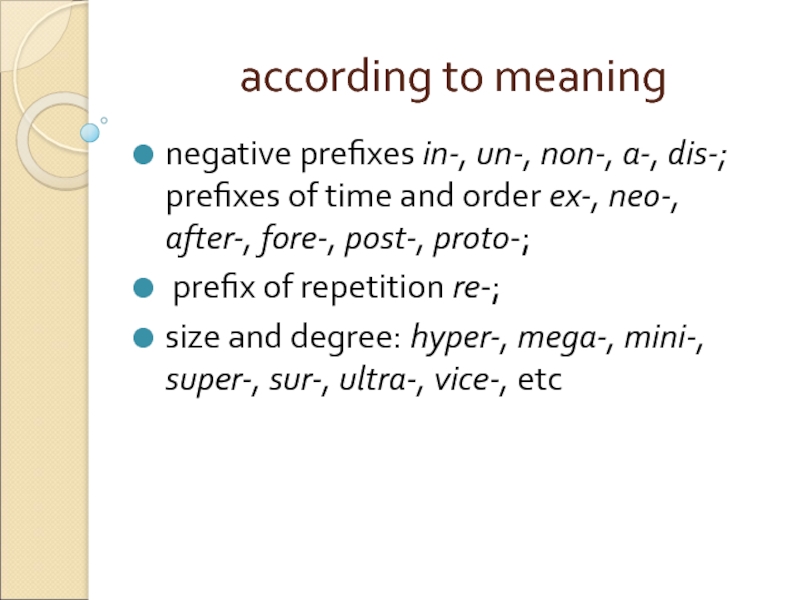

negative prefixes in-, un-, поп-, a-, dis-; prefixes of

time and order ex-, neo-, after-, fore-, post-, proto-;

prefix of repetition re-;

size and degree: hyper-, mega-, mini-, super-, sur-, ultra-, vice-, etc

Слайд 31according to productivity

What is productivity? It is the ability to

make new words:

e.g. un- is highly productive.

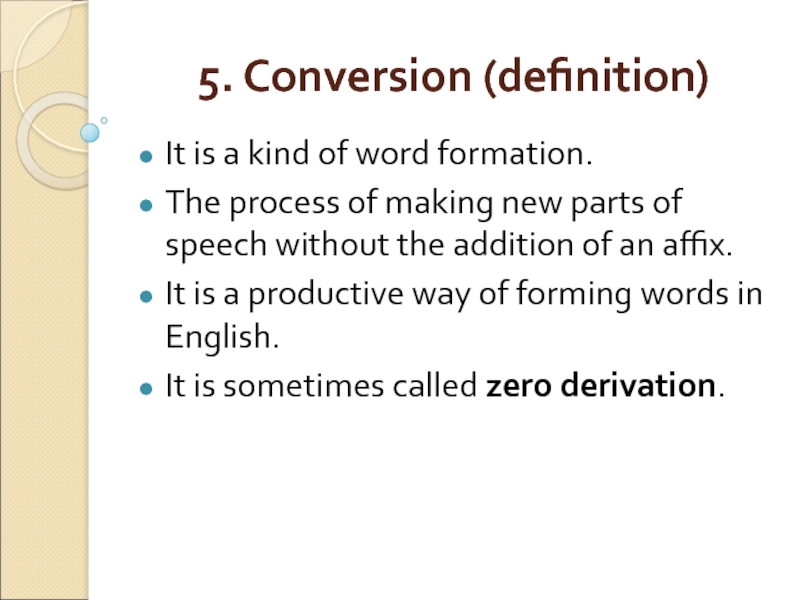

Слайд 325. Conversion (definition)

It is a kind of word formation.

The process of

making new parts of speech without the addition of an affix.

It is a productive way of forming words in English.

It is sometimes called zero derivation.

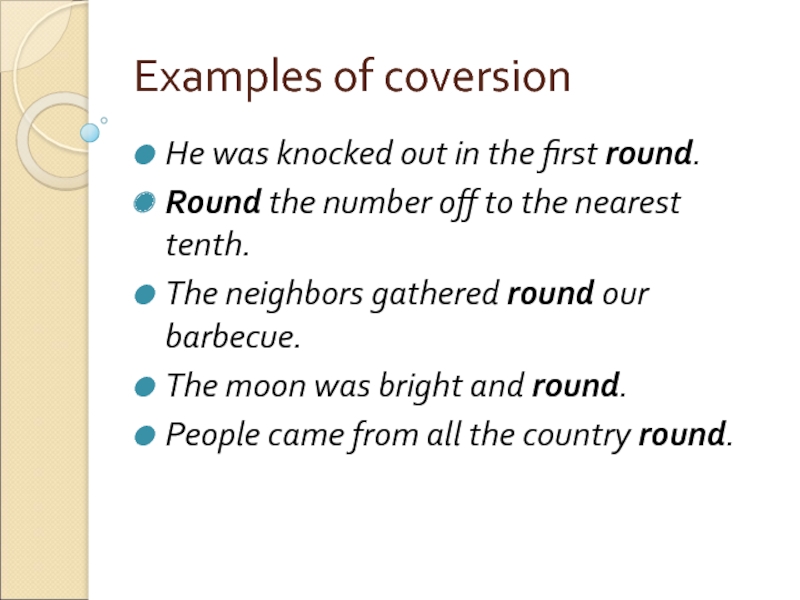

Слайд 33Examples of coversion

He was knocked out in the first round.

Round

the number off to the nearest tenth.

The neighbors gathered round our barbecue.

The moon was bright and round.

People came from all the country round.

Слайд 34Conversion

Prof. Smirnitsky A. I. in his works on the English language

treats conversion as a morphological way of forming words.

Other linguists (H. Marchand, V.N. Yartseva, Yu.A. Zhluktenko, A.Y. Zagoruiko, I.V. Arnold) treat conversion as a combined morphological and syntactic way of word-building, as a new word appears not in isolation but in a definite environment of other words.

Слайд 35The three most common types of conversion

verbs derived from nouns

(to butter, to ship),

nouns derived from verbs (a survey, a call),

verbs derived from adjectives (to empty).

Слайд 36Less common types of conversion

nouns from:

adjectives (a bitter, the

poor, a final),

from phrases, e.g. a down-and-out,

verbs from prepositions (up the price, out e.g. diplomats were outed from the country; Truth will out. — Истина станет известной)

Слайд 37Verbs converted from nouns

instrumental use of the object, e.g. screw

— to screw, eye — to eye;

action characteristic of the object, e.g. ape — to ape;

acquisition: fish — to fish;

deprivation of the object, e.g. dust — to dust

Слайд 38Nouns converted from verbs

instance of an action, e.g. to move

— a move;

word — agent of an action, e.g. to bore — a bore;

place of an action, e.g. to walk — a walk;

result of the action, e.g. to cut — a cut

Слайд 396.Word-Composition

Word-composition is the combination of two or more existing words to

create a new word

e.g. campsite (N+N), bluebird (A+N), whitewash (A+V), in-laws (P+N), jumpsuit (V+N).

Слайд 40Word-Composition

In most compounds the rightmost morpheme determines the category of the

entire word,

e.g. greenhouse is a noun because its rightmost component is a noun, spoonfeed is a verb because feed also belongs to this category, and

nationwide is an adjective just as wide is.

Слайд 416.1. Properties of compounds

How can compounds in English be written? —

Differently:

as single words,

with an intervening hyphen,

as separate words.

Слайд 42endocentric compounds

If a compound denotes a subtype of the concept

denoted by its head it is called endocentric.

Thus, cat food is a type of food, sky blue is a type of blue

airplane, steamboat, policeman, bathtowel

Слайд 43exocentric compounds

If the meaning of the compound does not follow

from the meanings of its parts it is said to be exocentric

e.g. redneck is a person and not a type of neck;

walkman is a type of portable radio.

Слайд 44Classification of compounds according to the principle

1) of the parts

of speech compound words represent:

nouns: night-gown, waterfall, looking-glass;

verbs: to honeymoon, to outgrow;

adjectives: peace-loving, hard-working, pennywise;

adverbs: downstairs, lip-deep;

prepositions: within, into, onto;

numerals: thirty-seven;

Слайд 45Classification of compounds according to the principle

2.of the means of composition

used to link the two ICs together:

neutral — formed by joining together two stems without connecting elements (juxtaposition), e.g. scarecrow, goldfish, crybaby;

morphological — components are joined by a linking element, i.e. vowels ‘o’ and ‘i’ or the consonant ‘s’, e.g. videophone, tragicomic, handicraft, craftsman, microchip;

syntactical — the components are joined by means of form-word stems, e.g. man-of-war, forget-me-not, bread-and-butter, face-to-face;

Слайд 467. Other Types of Word Formation

back-formation or disaffixation (baby-sitter —

to baby-sit). Back-formation is a process that creates a new word by removing a real or supposed affix from another word in the language.

sound interchange (speak — speech, blood — bleed), and sound imitation (walkie-talkie, brag rags, to giggle);

distinctive change (‘conduct — to con ‘duct, ‘increase — to in crease, ‘subject — to subject);

Слайд 47Other Types of Word Formation

blending: these are words that are created

from parts of two already existing items, usually the first part of one and the final part of the other:

brunch from breakfast and lunch,

smog from smoke and fog

clipping is a process that shortens a polysyllabic word by deleting one or more syllables: prof for professor, burger for hamburger.

Слайд 48Other Types of Word Formation

acronymy: NATO, NASA, WAC, UNESCO. Acronyms are

formed by taking the initial letters of the words in a phrase and pronouncing them as a word. (names of organizations and in terminology).

NASA stands for National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NA TO — North Atlantic Treaty Organization

Слайд 49Other Types of Word Formation

onomatopoeia, i.e. formations of words from sounds

that resemble those associated with the object or action to be named, or that seem suggestive of its qualities.

e.g. hiss, buzz, meow, cock-a-doodle-doo, and cuckoo

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the geological formation, see Word Formation. For the study of the origin and historical development of words, see Etymology.

In linguistics, word formation is an ambiguous term[1] that can refer to either:

- the processes through which words can change[2] (i.e. morphology), or

- the creation of new lexemes in a particular language

Morphological[edit]

A common method of word formation is the attachment of inflectional or derivational affixes.

Derivation[edit]

Examples include:

- the words governor, government, governable, misgovern, ex-governor, and ungovernable are all derived from the base word (to) govern[3]

Inflection[edit]

Inflection is modifying a word for the purpose of fitting it into the grammatical structure of a sentence.[4] For example:

- manages and managed are inflected from the base word (to) manage[1]

- worked is inflected from the verb (to) work

- talks, talked, and talking are inflected from the base (to) talk[3]

Nonmorphological[edit]

Abbreviation[edit]

Examples includes:

- etc. from et caetera

Acronyms & Initialisms[edit]

An acronym is a word formed from the first letters of other words.[5] For example:

- NASA is the acronym for National Aeronautics and Space Administration

- IJAL (pronounced /aidʒæl/) is the acronym for International Journal of American Linguistics

Acronyms are usually written entirely in capital letters, though some words originating as acronyms, like radar, are now treated as common nouns.[6]

Initialisms are similar to acronyms, but where the letters are pronounced as a series of letters. For example:

- ATM for Automated Teller Machine

- SIA for Singapore International Airlines[1]

Back-formation[edit]

In linguistics, back-formation is the process of forming a new word by removing actual affixes, or parts of the word that is re-analyzed as an affix, from other words to create a base.[3] Examples include:

- the verb headhunt is a back-formation of headhunter

- the verb edit is formed from the noun editor[3]

- the word televise is a back-formation of television

The process is motivated by analogy: edit is to editor as act is to actor. This process leads to a lot of denominal verbs.

The productivity of back-formation is limited, with the most productive forms of back-formation being hypocoristics.[3]

Blending[edit]

A lexical blend is a complex word typically made of two word fragments. For example:

- smog is a blend of smoke and fog

- brunch is a blend of breakfast and lunch.[5]

- stagflation is a blend of stagnation and inflation[1]

- chunnel is a blend of channel and tunnel,[1] referring to the Channel Tunnel

Although blending is listed under the Nonmorphological heading, there are debates as to how far blending is a matter of morphology.[1]

Compounding[edit]

Compounding is the processing of combining two bases, where each base may be a fully-fledged word. For example:

- desktop is formed by combining desk and top

- railway is formed by combining rail and way

- firefighter is formed by combining fire and fighter[3]

Compounding is a topic relevant to syntax, semantics, and morphology.[2]

Word formation vs. Semantic change[edit]

There are processes for forming new dictionary items which are not considered under the umbrella of word formation.[1] One specific example is semantic change, which is a change in a single word’s meaning. The boundary between word formation and semantic change can be difficult to define as a new use of an old word can be seen as a new word derived from an old one and identical to it in form.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Bauer, L. (1 January 2006). «Word Formation». Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics (Second Edition). Elsevier: 632–633. doi:10.1016/b0-08-044854-2/04235-8. ISBN 9780080448541. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ a b Baker, Anne; Hengeveld, Kees (2012). Linguistics. Malden, MA.: John Wiley & Sons. p. 23. ISBN 978-0631230366.

- ^ a b c d e f Katamba, F. (1 January 2006). «Back-Formation». Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics (Second Edition): 642–645. doi:10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/00108-5. ISBN 9780080448541.

- ^ Linguistics : the basics. Anne, July 8- Baker, Kees Hengeveld. Malden, MA.: John Wiley & Sons. 2012. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-631-23035-9. OCLC 748812931.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Aronoff, Mark (1983). «A Decade of Morphology and Word Formation». Annual Review of Anthropology. 12: 360. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.12.100183.002035.

- ^ Carstairs-McCarthy, Andrew (2018). An Introduction to English Morphology: Words and Their Structure (2nd ed.). Edinburgh University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-4744-2896-5.

See also[edit]

- Neologism