Management (or managing) is the administration of organizations, whether they are a business, a nonprofit organization, or a government body. It is the art and science of managing resources of the business.

Management includes the activities of setting the strategy of an organization and coordinating the efforts of its employees (or of volunteers) to accomplish its objectives through the application of available resources, such as financial, natural, technological, and human resources. «Run the business»[1] and «Change the business» are two concepts that are used in management to differentiate between the continued delivery of goods or services and adapting of goods or services to meet the changing needs of customers — see trend. The term «management» may also refer to those people who manage an organization—managers.

Some people study management at colleges or universities; major degrees in management includes the Bachelor of Commerce (B.Com.), Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA.), Master of Business Administration (MBA.), Master in Management (MSM or MIM) and, for the public sector, the Master of Public Administration (MPA) degree. Individuals who aim to become management specialists or experts, management researchers, or professors may complete the Doctor of Management (DM), the Doctor of Business Administration (DBA), or the PhD in Business Administration or Management. In the past few decades, there has been a movement for evidence-based management.[2]

Larger organizations generally have three hierarchical levels of managers,[3] in a pyramid structure:

- Senior managers such as members of a board of directors and a chief executive officer (CEO) or a president of an organization sets the strategic goals and policy of the organization and make decisions on how the overall organization will operate. Senior managers are generally executive-level professionals who provide direction to middle management, and directly or indirectly report to them.

- Middle managers such as branch managers, regional managers, department managers, and section managers, who provide direction to the front-line managers. They communicate the strategic goals and policy of senior management to the front-line managers.

- Line managers such as supervisors and front-line team leaders, oversee the work of regular employees (or volunteers, in some voluntary organizations) and provide direction on their work. Line managers often perform the managerial functions that are traditionally considered as the core of management. Despite the name, they are usually considered part of the workforce and not part of the organization’s management class.

In smaller organizations, a manager may have a much wider scope and may perform several roles or even all of the roles commonly observed in a large organization.

Social scientists study management as an academic discipline, investigating areas such as social organization, organizational adaptation, and organizational leadership.[4]

Etymology[edit]

The English verb «manage» has its roots by the XV century French verb ‘mesnager’, which often referred in equestrian language «to hold in hand the reins of a horse».[5] Also the Italian term maneggiare (to handle, especially tools or a horse) is possible. In Spanish, manejar can also mean to rule the horses.[6] These three terms derive from the two Latin words manus (hand) and agere (to act).

The French word for housekeeping, ménagerie, derived from ménager («to keep house»; compare ménage for «household»), also encompasses taking care of domestic animals. Ménagerie is the French translation of Xenophon’s famous book Oeconomicus[7] (Greek: Οἰκονομικός) on household matters and husbandry. The French word mesnagement (or ménagement) influenced the semantic development of the English word management in the 17th and 18th centuries.[8]

Definitions[edit]

Views on the definition and scope of management include:

- Henri Fayol (1841–1925) stated: «to manage is to forecast and to plan, to organise, to command, to co-ordinate and to control».[9]

- Fredmund Malik (1944– ) defines management as «the transformation of resources into utility».[10]

- Management is included[by whom?] as one of the factors of production – along with machines, materials and money.

- Ghislain Deslandes defines management as «a vulnerable force, under pressure to achieve results and endowed with the triple power of constraint, imitation and imagination, operating on subjective, interpersonal, institutional and environmental levels».[11]

- Peter Drucker (1909–2005) saw the basic task of management as twofold: marketing and innovation. Nevertheless, innovation is also linked to marketing (product innovation is a central strategic marketing issue).[citation needed] Drucker identifies marketing as a key essence for business success, but management and marketing are generally understood[by whom?] as two different branches of business administration knowledge.

Theoretical scope[edit]

Management involves identifying the mission, objective, procedures, rules and manipulation[12] of the human capital of an enterprise to contribute to the success of the enterprise.[13] Scholars have focused on the management of individual,[14] organizational,[15] and inter-organizational relationships. This implies effective communication: an enterprise environment (as opposed to a physical or mechanical mechanism) implies human motivation and implies some sort of successful progress or system outcome.[16] As such, management is not the manipulation of a mechanism (machine or automated program), not the herding of animals, and can occur either in a legal or in an illegal enterprise or environment. From an individual’s perspective, management does not need to be seen solely from an enterprise point of view, because management is an essential[quantify] function in improving one’s life and relationships.[17] Management is therefore everywhere[18] and it has a wider range of application.[clarification needed] Communication and a positive endeavor are two main aspects of it either through enterprise or through independent pursuit.[citation needed] Plans, measurements, motivational psychological tools, goals, and economic measures (profit, etc.) may or may not be necessary components for there to be management. At first, one views management functionally, such as measuring quantity, adjusting plans, and meeting goals,[citation needed] but this applies even in situations where planning does not take place. From this perspective, Henri Fayol (1841–1925)[19][page needed] considers management to consist of five functions:

- planning (forecasting)

- organizing

- commanding

- coordinating

- controlling

In another way of thinking, Mary Parker Follett (1868–1933), allegedly defined management as «the art of getting things done through people».[20] She described management as a philosophy.[21][need quotation to verify]

Critics,[which?] however, find this definition useful but far too narrow. The phrase «management is what managers do» occurs widely,[22] suggesting the difficulty of defining management without circularity, the shifting nature of definitions[citation needed] and the connection of managerial practices with the existence of a managerial cadre or of a class.

One habit of thought regards management as equivalent to «business administration» and thus excludes management in places outside commerce, as for example in charities and in the public sector. More broadly, every organization must «manage» its work, people, processes, technology, etc. to maximize effectiveness.[citation needed] Nonetheless, many people refer to university departments that teach management as «business schools». Some such institutions (such as the Harvard Business School) use that name, while others (such as the Yale School of Management) employ the broader term «management».

English-speakers may also use the term «management» or «the management» as a collective word describing the managers of an organization, for example of a corporation.[23]

Historically this use of the term often contrasted with the term «labor» – referring to those being managed.[24]

But in the present era[when?] the concept of management is identified[by whom?] in the wide areas[which?] and its frontiers have been pushed[by whom?] to a broader range.[citation needed] Apart from profitable organizations, even non-profit organizations apply management concepts. The concept and its uses are not constrained[by whom?]. Management as a whole is the process of planning, organizing, directing, leading and controlling.[25]

Levels[edit]

A common management structure of organizations includes three management levels: first-level, middle-level, and top-level managers. First-line managers are the lowest level of management and manage the work of non-managerial individuals who are directly involved with the production or creation of the organization’s products. First-line managers are often called supervisors, but may also be called line managers, office managers, or even foremen. Middle managers include all levels of management between the first-line level and the top level of the organization. These managers manage the work of first-line managers and may have titles such as department head, project leader, plant manager, or division manager. Top managers are responsible for making organization-wide decisions and establishing the plans and goals that affect the entire organization. These individuals typically have titles such as executive vice president, president, managing director, chief operating officer, chief executive officer, or chairman of the board.

These managers are classified in a hierarchy of authority, and perform different tasks. In many organizations, the number of managers in every level resembles a pyramid. Each level is explained below in specifications of their different responsibilities and likely job titles.[26]

Top management[edit]

The top or senior layer of management is a small group which consists of the board of directors (including non-executive directors, executive directors and independent directors), president, vice-president, CEOs and other members of the C-level executives. Different organizations have various members in their C-suite, which may include a chief financial officer, chief technology officer, and so on. They are responsible for controlling and overseeing the operations of the entire organization. They set a «tone at the top» and develop strategic plans, company policies, and make decisions on the overall direction of the organization. In addition, top-level managers play a significant role in the mobilization of outside resources. Senior managers are accountable to the shareholders, the general public and to public bodies that oversee corporations and similar organizations. Some members of the senior management may serve as the public face of the organization, and they may make speeches to introduce new strategies or appear in marketing.

The board of directors is typically primarily composed of non-executives who owe a fiduciary duty to shareholders and are not closely involved in the day-to-day activities of the organization, although this varies depending on the type (e.g., public versus private), size and culture of the organization. These directors are theoretically liable for breaches of that duty and typically insured under directors and officers liability insurance. Fortune 500 directors are estimated to spend 4.4 hours per week on board duties, and median compensation was $212,512 in 2010. The board sets corporate strategy, makes major decisions such as major acquisitions,[27] and hires, evaluates, and fires the top-level manager (chief executive officer or CEO). The CEO typically hires other positions. However, board involvement in the hiring of other positions such as the chief financial officer (CFO) has increased.[28] In 2013, a survey of over 160 CEOs and directors of public and private companies found that the top weaknesses of CEOs were «mentoring skills» and «board engagement», and 10% of companies never evaluated the CEO.[29] The board may also have certain employees (e.g., internal auditors) report to them or directly hire independent contractors; for example, the board (through the audit committee) typically selects the auditor.

Helpful skills of top management vary by the type of organization but typically include[30] a broad understanding of competition, world economies, and politics. In addition, the CEO is responsible for implementing and determining (within the board’s framework) the broad policies of the organization. Executive management accomplishes the day-to-day details, including: instructions for preparation of department budgets, procedures, schedules; appointment of middle level executives such as department managers; coordination of departments; media and governmental relations; and shareholder communication.

Middle management[edit]

Consist of general managers, branch managers and department managers. They are accountable to the top management for their department’s function. They devote more time to organizational and directional functions. Their roles can be emphasized as executing organizational plans in conformance with the company’s policies and the objectives of the top management, they define and discuss information and policies from top management to lower management, and most importantly they inspire and provide guidance to lower-level managers towards better performance.

Middle management is the midway management of a categorized organization, being secondary to the senior management but above the deepest levels of operational members. An operational manager may be well-thought-out by middle management or may be categorized as non-management operate, liable to the policy of the specific organization. The efficiency of the middle level is vital in any organization since they bridge the gap between top level and bottom level staffs.

Their functions include:

- Design and implement effective group and inter-group work and information systems.

- Define and monitor group-level performance indicators.

- Diagnose and resolve problems within and among workgroups.

- Design and implement reward systems that support cooperative behavior. They also make decisions and share ideas with top managers.

Line management[edit]

Line managers include supervisors, section leaders, forepersons and team leaders. They focus on controlling and directing regular employees. They are usually responsible for assigning employees’ tasks, guiding and supervising employees on day-to-day activities, ensuring the quality and quantity of production and/or service, making recommendations and suggestions to employees on their work, and channeling employee concerns that they cannot resolve to mid-level managers or other administrators. First-level or «front line» managers also act as role models for their employees. In some types of work, front line managers may also do some of the same tasks that employees do, at least some of the time. For example, in some restaurants, the front line managers will also serve customers during a very busy period of the day. In general, line managers are considered part of the workforce and not part of the organization’s proper management despite performing traditional management functions.

Front-line managers typically provide:

- Training for new employees

- Basic supervision

- Motivation

- Performance feedback and guidance

Some front-line managers may also provide career planning for employees who aim to rise within the organization.

Training and education[edit]

Colleges and universities around the world offers bachelor’s degrees, graduate degrees, diplomas and certificates in management; generally within their colleges of business, business schools or faculty of management but also in other related departments. In the 2010s era, there has been an increase in online management education and training in the form of electronic educational technology (also called e-learning). Online education has increased the accessibility of management training to people who do not live near a college or university, or who cannot afford to travel to a city where such training is available.

Requirement[edit]

While some professions require academic credentials in order to work in the profession (e.g., law, medicine, engineering, which require, respectively the Bachelor of Law, Doctor of Medicine and Bachelor of Engineering degrees), management and administration positions do not necessarily require the completion of academic degrees. Some well-known senior executives in the US who did not complete a degree include Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg. However, many managers and executives have completed some type of business or management training, such as a Bachelor of Commerce or a Master of Business Administration degree. Some major organizations, including companies, non-profit organizations and governments, require applicants to managerial or executive positions to hold at minimum bachelor’s degree in a field related to administration or management, or in the case of business jobs, a Bachelor of Commerce or a similar degree.

Undergraduate[edit]

At the undergraduate level, the most common business programs are the Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA) and Bachelor of Commerce (B.Com.).

These typically comprise a four-year program designed to give students an overview of the role of managers in planning and directing within an organization.

Course topics include accounting, financial management, statistics, marketing, strategy, and other related areas.

There are many other undergraduate degrees that include the study of management, such as Bachelor of Arts degrees with a major in business administration or management and Bachelor of Public Administration (B.P.A), a degree designed for individuals aiming to work as bureaucrats in the government jobs.

Many colleges and universities also offer certificates and diplomas in business administration or management, which typically require one to two years of full-time study.

Note that to manage technological areas, one often needs an undergraduate degree in a STEM area.

Graduate[edit]

At the graduate level students aiming at careers as managers or executives may choose to specialize in major subareas of management or business administration such as entrepreneurship, human resources, international business, organizational behavior, organizational theory, strategic management,[31] accounting, corporate finance, entertainment, global management, healthcare management, investment management, sustainability and real estate.

A Master of Business Administration (MBA) is the most popular professional degree at the master’s level and can be obtained from many universities in the United States. MBA programs provide further education in management and leadership for graduate students. Other master’s degrees in business and management include Master of Management (MM) and the Master of Science (M.Sc.) in business administration or management, which is typically taken by students aiming to become researchers or professors.

There are also specialized master’s degrees in administration for individuals aiming at careers outside of business, such as the Master of Public Administration (MPA) degree (also offered as a Master of Arts in Public Administration in some universities), for students aiming to become managers or executives in the public service and the Master of Health Administration, for students aiming to become managers or executives in the health care and hospital sector.

Management doctorates are the most advanced terminal degrees in the field of business and management. Most individuals obtaining management doctorates take the programs to obtain the training in research methods, statistical analysis and writing academic papers that they will need to seek careers as researchers, senior consultants and/or professors in business administration or management. There are three main types of management doctorates: the Doctor of Management (D.M.), the Doctor of Business Administration (D.B.A.), and the Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Business Administration or Management. In the 2010s, doctorates in business administration and management are available with many specializations.

Good practices[edit]

While management trends can change so fast, the long-term trend in management has been defined by a market embracing diversity and a rising service industry. Managers are currently being trained to encourage greater equality for minorities and women in the workplace, by offering increased flexibility in working hours, better retraining, and innovative (and usually industry-specific) performance markers. Managers destined for the service sector are being trained to use unique measurement techniques, better worker support and more charismatic leadership styles.[32] Human resources finds itself increasingly working with management in a training capacity to help collect management data on the success (or failure) of management actions with employees.[33]

Good practices identified for managers include «walking the shop floor»,[34] and, especially for managers who are new in post, identifying and achieving some «quick wins» which demonstrate visible success in establishing appropriate objectives.[35] Leadership writer John Kotter uses the phrase «Short-Term Wins» to express the same idea.[36] As in all work, achieving an appropriate work-life balance for self and others is an important management practice.[37]

Evidence-based management[edit]

Evidence-based management is an emerging movement to use the current, best evidence in management and decision-making. It is part of the larger movement towards evidence-based practices. Evidence-based management entails managerial decisions and organizational practices informed by the best available evidence.[38] As with other evidence-based practice, this is based on the three principles of: 1) published peer-reviewed (often in management or social science journals) research evidence that bears on whether and why a particular management practice works; 2) judgement and experience from contextual management practice, to understand the organization and interpersonal dynamics in a situation and determine the risks and benefits of available actions; and 3) the preferences and values of those affected.[39][40]

History[edit]

Some see management as a late-modern (in the sense of late modernity) conceptualization.[41] On those terms it cannot have a pre-modern history – only harbingers (such as stewards). Others, however, detect management-like thought among ancient Sumerian traders and the builders of the pyramids of ancient Egypt. Slave-owners through the centuries faced the problems of exploiting/motivating a dependent but sometimes unenthusiastic or recalcitrant workforce, but many pre-industrial enterprises, given their small scale, did not feel compelled to face the issues of management systematically. However, innovations such as the spread of Arabic numerals (5th to 15th centuries) and the codification of double-entry book-keeping (1494) provided tools for management assessment, planning and control.

- An organisation is more stable if members have the right to express their differences and solve their conflicts within it.

- While one person can begin an organisation, «it is lasting when it is left in the care of many and when many desire to maintain it».

- A weak manager can follow a strong one, but not another weak one, and maintain authority.

- A manager seeking to change an established organization «should retain at least a shadow of the ancient customs».

With the changing workplaces of industrial revolutions in the 18th and 19th centuries, military theory and practice contributed approaches to managing the newly popular factories.[42]

Given the scale of most commercial operations and the lack of mechanized record-keeping and recording before the industrial revolution, it made sense for most owners of enterprises in those times to carry out management functions by and for themselves. But with growing size and complexity of organizations, a distinction between owners (individuals, industrial dynasties or groups of shareholders) and day-to-day managers (independent specialists in planning and control) gradually became more common.

Early writing[edit]

The field of management originated in ancient China,[43] including possibly the first highly centralized bureaucratic state, and the earliest (by the second century BC) example of an administration based on merit through testing.[44] Some theorists have cited ancient military texts as providing lessons for civilian managers. For example, Chinese general Sun Tzu in his 6th-century BC work The Art of War recommends[citation needed] (when re-phrased in modern terminology) being aware of and acting on strengths and weaknesses of both a manager’s organization and a foe’s.[45][need quotation to verify] The writings of influential Chinese Legalist philosopher Shen Buhai may be considered[by whom?] to embody a rare premodern example of abstract theory of administration.[46][47] American philosopher Herrlee G. Creel and other scholars find the influence of Chinese administration in Europe by the 12th century.[48][49][50][51] Thomas Taylor Meadows, Britain’s consul in Guangzhou, argued in his Desultory Notes on the Government and People of China (1847) that «the long duration of the Chinese empire is solely and altogether owing to the good government which consists in the advancement of men of talent and merit only,» and that the British must reform their civil service by making the institution meritocratic.[52] Influenced by the ancient Chinese imperial examination, the Northcote–Trevelyan Report of 1854 recommended that recruitment should be on the basis of merit determined through competitive examination, candidates should have a solid general education to enable inter-departmental transfers, and promotion should be through achievement rather than «preferment, patronage, or purchase».[53][52] This led to implementation of Her Majesty’s Civil Service as a systematic, meritocratic civil service bureaucracy.[54] Like the British, the development of French bureaucracy was influenced by the Chinese system. Voltaire claimed that the Chinese had «perfected moral science» and François Quesnay advocated an economic and political system modeled after that of the Chinese.[55] French civil service examinations adopted in the late 19th century were also heavily based on general cultural studies. These features have been likened to the earlier Chinese model.[56]

Various ancient and medieval civilizations produced «mirrors for princes» books, which aimed to advise new monarchs on how to govern. Plato described job specialization in 350 BC, and Alfarabi listed several leadership traits in AD 900.[57] Other examples include the Indian Arthashastra by Chanakya (written around 300 BC), and The Prince by Italian author

Niccolò Machiavelli (c. 1515).[58]

Written in 1776 by Adam Smith, a Scottish moral philosopher, The Wealth of Nations discussed efficient organization of work through division of labour.[58]

Smith described how changes in processes could boost productivity in the manufacture of pins. While individuals could produce 200 pins per day, Smith analyzed the steps involved in manufacture and, with 10 specialists, enabled production of 48,000 pins per day.[58][need quotation to verify]

19th century[edit]

Classical economists such as Adam Smith (1723–1790) and John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) provided a theoretical background to resource allocation, production (economics), and pricing issues. About the same time, innovators like Eli Whitney (1765–1825), James Watt (1736–1819), and Matthew Boulton (1728–1809) developed elements of technical production such as standardization, quality-control procedures, cost-accounting, interchangeability of parts, and work-planning. Many of these aspects of management existed in the pre-1861 slave-based sector of the US economy. That environment saw 4 million people, as the contemporary usages had it, «managed» in profitable quasi-mass production[59]

before wage slavery eclipsed chattel slavery.

Salaried managers as an identifiable group first became prominent in the late 19th century.[60] As large corporations began to overshadow small family businesses the need for personnel management positions became more necessary.[61] Businesses grew into large corporations and the need for clerks, bookkeepers, secretaries and managers expanded. The demand for trained managers led college and university administrators to consider and move forward with plans to create the first schools of business on their campuses.

20th century[edit]

At the turn of the twentieth century the need for skilled and trained managers had become increasingly apparent. The demand occurred as personnel departments began to expand rapidly. In 1915, less than one in twenty manufacturing firms had a dedicated personnel department. By 1929 that number had grown to over one-third.[62] Formal management education became standardized at colleges and universities.[63] Colleges and universities capitalized on the needs of corporations by forming business schools and corporate placement departments.[64] This shift toward formal business education marked the creation of a corporate elite in the US.

By about 1900 one finds managers trying to place their theories on what they regarded as a thoroughly scientific basis (see scientism for perceived limitations of this belief). Examples include Henry R. Towne’s Science of management in the 1890s, Frederick Winslow Taylor’s The Principles of Scientific Management (1911), Lillian Gilbreth’s Psychology of Management (1914),[65] Frank and Lillian Gilbreth’s Applied motion study (1917), and Henry L. Gantt’s charts (1910s). J. Duncan wrote the first college management textbook in 1911. In 1912 Yoichi Ueno introduced Taylorism to Japan and became the first management consultant of the «Japanese management style». His son Ichiro Ueno pioneered Japanese quality assurance.

The first comprehensive theories of management appeared around 1920.[citation needed] The Harvard Business School offered the first Master of Business Administration degree (MBA) in 1921. People like Henri Fayol (1841–1925) and Alexander Church (1866–1936) described the various branches of management and their inter-relationships. In the early 20th century, people like Ordway Tead (1891–1973), Walter Scott (1869–1955) and J. Mooney applied the principles of psychology to management. Other writers, such as Elton Mayo (1880–1949), Mary Parker Follett (1868–1933), Chester Barnard (1886–1961), Max Weber (1864–1920), who saw what he called the «administrator» as bureaucrat,[66] Rensis Likert (1903–1981), and Chris Argyris (born 1923) approached the phenomenon of management from a sociological perspective.

The 1930s and 1940s saw the development of a militarization trend in management in parts of Eurasia – both the NKVD (in the Soviet Union) and the SS (in the Greater Germanic Reich), for example, managed labor camps as industrial enterprises using slave labor supervised by uniformed cadres.[67][68]

Military habits persisted in some management circles.[69]

Peter Drucker (1909–2005) wrote one of the earliest books on applied management: Concept of the Corporation (published in 1946). It resulted from Alfred Sloan (chairman of General Motors until 1956) commissioning a study of the organisation. Drucker went on to write 39 books, many in the same vein.

H. Dodge, Ronald Fisher (1890–1962), and Thornton C. Fry introduced statistical techniques into management-studies. In the 1940s, Patrick Blackett worked in the development of the applied-mathematics science of operations research, initially for military operations. Operations research, sometimes known as «management science» (but distinct from Taylor’s scientific management), attempts to take a scientific approach to solving decision-problems, and can apply directly to multiple management problems, particularly in the areas of logistics and operations.

Some of the later 20th-century developments include the theory of constraints (introduced in 1984), management by objectives (systematised in 1954), re-engineering (early 1990s), Six Sigma (1986), management by walking around (1970s), the Viable system model (1972), and various information-technology-driven theories such as agile software development (so-named from 2001), as well as group-management theories such as Cog’s Ladder (1972) and the notion of «thriving on chaos»[70] (1987).

As the general recognition of managers as a class solidified during the 20th century and gave perceived practitioners of the art/science of management a certain amount of prestige, so the way opened for popularised systems of management ideas to peddle their wares. In this context many management fads may have had more to do with pop psychology than with scientific theories of management.

Business management[when?] includes the following branches:[citation needed]

- financial management

- human resource management

- Management cybernetics

- information technology management (responsible for management information systems )

- marketing management

- operations management and production management

- strategic management

21st century[edit]

In the 21st century observers find it increasingly difficult to subdivide management into functional categories in this way. More and more processes simultaneously involve several categories. Instead, one tends to think in terms of the various processes, tasks, and objects subject to management.[citation needed]

Branches of management theory also exist relating to nonprofits and to government: such as public administration, public management, and educational management. Further, management programs related to civil-society organizations have also spawned programs in nonprofit management and social entrepreneurship.

Note that many of the assumptions made by management have come under attack from business-ethics viewpoints, critical management studies, and anti-corporate activism.

As one consequence, workplace democracy (sometimes referred to as Workers’ self-management) has become both more common and more advocated, in some places distributing all management functions among workers, each of whom takes on a portion of the work. However, these models predate any current political issue, and may occur more naturally than does a command hierarchy. All management embraces to some degree a democratic principle—in that in the long term, the majority of workers must support management. Otherwise, they leave to find other work or go on strike. Despite the move toward workplace democracy, command-and-control organization structures remain commonplace as de facto organization structures. Indeed, the entrenched nature of command-and-control is evident in the way that recent[when?] layoffs have been conducted with management ranks affected far less than employees at the lower levels.[citation needed] In some cases, management has even rewarded itself with bonuses after laying off lower-level workers.[71]

According to leadership-academic Manfred F.R. Kets de Vries, a contemporary senior-management team will almost inevitably have some personality disorders.[72]

Nature of work[edit]

In profitable organizations, management’s primary function is the satisfaction of a range of stakeholders. This typically involves making a profit (for the shareholders), creating valued products at a reasonable cost (for customers), and providing great employment opportunities for employees. In case of nonprofit management, one of the main functions is, keeping the faith of donors. In most models of management and governance, shareholders vote for the board of directors, and the board then hires senior management. Some organizations have experimented with other methods (such as employee-voting models) of selecting or reviewing managers, but this is rare.

Topics[edit]

Basics[edit]

According to Fayol, management operates through five basic functions: planning, organizing, commanding, coordinating and controlling.

- Planning: Deciding what needs to happen in the future and generating plans for action (deciding in advance).

- Organizing (or staffing): Making sure the human and nonhuman resources are put into place.[73]

- Commanding (or leading): Determining what must be done in a situation and getting people to do it.

- Coordinating: Creating a structure through which an organization’s goals can be accomplished.

- Controlling: Checking progress against plans.

Basic roles[edit]

- Interpersonal: roles that involve coordination and interaction with employees.

Figurehead, leader, liaison

- Informational: roles that involve handling, sharing, and analyzing information.

Nerve centre, disseminator, spokesperson

- Decision: roles that require decision-making.

Entrepreneur, negotiator, allocator, disturbance handler

Skills[edit]

Management skills include:

- Political: used to build a power base and to establish connections.

- Interpersonal: used to communicate, motivate, mentor and delegate.

- Diagnostic: ability to visualize appropriate responses to a situation.

- Leadership: ability to communicate a vision and inspire people to embrace that vision.[74]

- cross-cultural leadership: ability to understand the effects of culture on leadership style.

- Behavioral: perception towards others, conflict resolution, time-management, self-improvement, stress management and resilience, patience, clear communication.[75]

Implementation of policies and strategies[edit]

- All policies and strategies must be discussed with all managerial personnel and staff.

- Managers must understand where and how they can implement their policies and strategies.

- An action plan must be devised for each department.

- Policies and strategies must be reviewed regularly.

- Contingency plans must be devised in case the environment changes.

- Top-level managers should carry out regular progress assessments.

- The business requires team spirit and a good environment.

- The missions, objectives, strengths and weaknesses of each department must be analyzed to determine their roles in achieving the business’s mission.

- The forecasting method develops a reliable picture of the business’s future environment.

- A planning unit must be created to ensure that all plans are consistent and that policies and strategies are aimed at achieving the same mission and objectives.

Policies and strategies in the planning process[edit]

- They give mid and lower-level managers a good idea of the future plans for each department in an organization.

- A framework is created whereby plans and decisions are made.

- Mid and lower-level management may add their own plans to the business’s strategies.

See also[edit]

- Certificate in Management Studies

- Engineering management

- Outline of business management

References[edit]

- ^ KATHRYN DILL. (2021, January 12). YOUR NEXT BOSS: MORE HARMONY, LESS AUTHORITY. Wall Street Journal. [1]

- ^ «What Is Evidence-Based Management? – Center for Evidence Based Management». Retrieved 2022-03-03.

- ^ DuBrin, Andrew J. (2009). Essentials of management (8th ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson Business & Economics. ISBN 978-0-324-35389-1. OCLC 227205643.

- ^ Waring, S.P., 2016. Taylorism transformed: Scientific management theory since 1945. UNC Press Books.

- ^ Mintzberg, Henry,. (2014). Manager l’essentiel : ce que font vraiment les managers … et ce qu’ils pourraient faire mieux. Paris: Vuibert. ISBN 978-2-311-40094-6.

- ^ Real Academia Española, Diccionario de la lengua española. «manejar | Diccionario de la lengua española» (in Spanish).

- ^ Xenophon (1734). «Oikonomikos. Oder Xenophon vom Haus-Wesen, aus der Griechischen- in die Teutsche Sprache übersetzet von Barthold Henrich Brockes, dem jüngern. Mit einer Vorrede S.T. Herrn Jo. Alb. Fabricii … Nebst den wenigen Stücken, die aus der Lateinischen Uebersetzung Ciceronis noch übrig».

- ^ «Home : Oxford English Dictionary».

- ^ SS Gulshan. Management Principles and Practices by Lallan Prasad and SS Gulshan. Excel Books India. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-93-5062-099-1.

- ^

Ann Viola Ulvin - ^ Deslandes G., (2014), “Management in Xenophon’s Philosophy : a Retrospective Analysis”, 38th Annual Research Conference, Philosophy of Management, 2014, July 14–16, Chicago

- ^

Prabbal Frank attempts to make a subtle distinction between management and manipulation: Frank, Prabbal (2007). People Manipulation: A Positive Approach (2 ed.). New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd (published 2009). pp. 3–7. ISBN 978-81-207-4352-6. Retrieved 2015-09-05.There is a difference between management and manipulation. The difference is thin […] If management is handling, then manipulation is skilful handling. In short, manipulation is skilful management. […] Manipulation is in essence leveraged management. […] It is an alive thing while management is a dead concept. It requires a proactive approach rather than a reactive approach. […] People cannot be managed.

- ^ Powell, Thomas C. (2001). «Competitive advantage: logical and philosophical considerations». Strategic Management Journal. 22 (9): 875–888. doi:10.1002/smj.173. ISSN 1097-0266.

- ^ Langfred, Claus (2000). «The paradox of self‐management: individual and group autonomy in work groups». Journal of Organizational Behavior. 21 (5): 563–585. doi:10.1002/1099-1379(200008)21:5<563::AID-JOB31>3.0.CO;2-H.

- ^ Wood, Robert; Bandura, Albert (1989). «Social Cognitive Theory of Organizational Management». The Academy of Management Review. 14 (3): 361–384. doi:10.2307/258173. ISSN 0363-7425. JSTOR 258173.

- ^ Julie Zink, Ph D.; Zink, Julie (2017). «Chapter 1: Introducing Organizational Communication».

- ^ «Managerial Skills — 3 Types of Skills Each Manager Will Need». Entrepreneurs Box. 2021-06-06. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- ^ «Management is Universal Process and Phenomenon (Explained)». www.iedunote.com. 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- ^ Administration industrielle et générale – prévoyance organization – commandment, coordination – contrôle, Paris : Dunod, 1966

- ^

Jones, Norman L. (2013-10-02). «Chapter Two: Of Poetry and Politics: The Managerial Culture of Sixteenth-Century England». In Kaufman, Peter Iver (ed.). Leadership and Elizabethan Culture. Jepson Studies in Leadership. Palgrave Macmillan (published 2013). p. 17. ISBN 978-1-137-34029-0. Retrieved 2015-08-29.Mary Parker Follett, the ‘prophet of management’ reputedly defined management as the ‘art of getting things done through people.’ […] Whether or not she said it, Follett describes the attributes of dynamic management as being coactive rather than coercive.

- ^ Vocational Business: Training, Developing and Motivating People by Richard Barrett – Business & Economics – 2003. p. 51.

- ^

Compare: Holmes, Leonard (2012-11-28). The Dominance of Management: A Participatory Critique. Voices in Development Management. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. (published 2012). p. 20. ISBN 978-1-4094-8866-8. Retrieved 2015-08-29.Lupton’s (1983: 17) notion that management is ‘what managers do during their working hours’, if valid, could only apply to descriptive conceptualizations of management, where ‘management’ is effectively synonymous with ‘managing’, and where ‘managing’ refers to an activity, or set of activities carried out by managers.

- ^

Harper, Douglas. «management». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2015-08-29. – «Meaning ‘governing body’ (originally of a theater) is from 1739.» - ^

See for examples Melling, Joseph; McKinlay, Alan, eds. (1996). Management, Labour, and Industrial Politics in Modern Europe: The Quest for Productivity Growth During the Twentieth Century. Edward Elgar. ISBN 978-1-85898-016-4. Retrieved 2015-08-29. - ^

Compare:

Vasconcelos e Sá, Jorge (2012). There is no leadership: only effective management: Lessons from Lee’s Perfect Battle, Xenophon’s Cyrus the Great and the practice of the best managers in the world. Porto: Vida Economica Editorial. p. 19. ISBN 9789727886012. Retrieved 2020-01-22.[…] to ask what is leadership about […] is a false question. The right question is: what is effective management?

- ^ «Management Levels and Types | Boundless Management». courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- ^ Board of Directors: Duties & Liabilities Archived 2014-03-24 at the Wayback Machine. Stanford Graduate School of Business.

- ^ DeMars L. (2006). Heavy Vetting: Boards of directors now want to talk to would-be CFOs — and vice versa. CFO Magazine.

- ^ 2013 CEO Performance Evaluation Survey. Stanford Graduate School of Business.

- ^ Kleiman, Lawrence S. «Management and Executive Development.»Reference for Business:Encyclopedia of Business(2010): n.p. 25 Mar 2011. [2]

- ^ «AOM Placement Presentations».

- ^ «Four Ways to Be A Better Boss». www.randstadusa.com. Randstad USA. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ «The Role of HR in Uncertain Times» (PDF). Economist Intelligence Unit. Economist Intelligence Unit. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ Verity, J., Five benefits of walking the ‘shop floor’, People Puzzles, accessed 11 March 2023

- ^ MindTools, Achieving Quick Wins, accessed 11 March 2023

- ^ Kotter, J., The 8-Step Process for Leading Change, accessed 11 March 2023

- ^ Britt, H., 14 Ways To Improve Work-Life Balance, accessed 11 March 2023

- ^ Pfeffer J, Sutton RI (March 2006). Hard Facts, Dangerous Half-Truths And Total Nonsense: Profiting From Evidence-Based Management (first ed.). Boston, Mass: Harvard Business Review Press. ISBN 978-1-59139-862-2.

- ^ Spring B (July 2007). «Evidence-based practice in clinical psychology: what it is, why it matters; what you need to know». Journal of Clinical Psychology. 63 (7): 611–31. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.456.9970. doi:10.1002/jclp.20373. PMID 17551934.

- ^ Lilienfeld SO, Ritschel LA, Lynn SJ, Cautin RL, Latzman RD (November 2013). «Why many clinical psychologists are resistant to evidence-based practice: root causes and constructive remedies». Clinical Psychology Review. 33 (7): 883–900. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.008. PMID 23647856.

- ^ Waring, S.P., 2016, Taylorism transformed: Scientific management theory since 1945. UNC Press Books.

- ^

Giddens, Anthony (1981). A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism. Social and Politic Theory from Polity Press. Vol. 1. University of California Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-520-04490-6. Retrieved 2013-12-29.In the army barracks, and in the mass co-ordination of men on the battlefield (epitomised by the military innovations of Prince Maurice of Orange and Nassau in the sixteenth century) are to be found the prototype of the regimentation of the factory – as both Marx and Weber noted.

- ^ Ewan Ferlie, Laurence E. Lynn, Christopher Pollitt (2005) The Oxford Handbook of Public Management, p.30.

- ^ Kazin, Edwards, and Rothman (2010), 142. One of the oldest examples of a merit-based civil service system existed’ in the imperial bureaucracy of China.

- Tan, Chung; Geng, Yinzheng (2005). India and China: twenty centuries of civilization interaction and vibrations. University of Michigan Press. p. 128.

China not only produced the world’s first «bureaucracy», but also the world’s first «meritocracy»

- Konner, Melvin (2003). Unsettled: an anthropology of the Jews. Viking Compass. p. 217. ISBN 9780670032440.

China is the world’s oldest meritocracy

- Tucker, Mary Evelyn (2009). «Touching the Depths of Things: Cultivating Nature in East Asia». Ecology and the Environment: Perspectives from the Humanities: 51.

To staff these institutions, they created the oldest meritocracy in the world, in which government appointments were based on civil service examinations that drew on the values of the Confucian Classics

- Tan, Chung; Geng, Yinzheng (2005). India and China: twenty centuries of civilization interaction and vibrations. University of Michigan Press. p. 128.

- ^ Gomez-Mejia, Luis R.; David B. Balkin; Robert L. Cardy (2008). Management: People, Performance, Change, 3rd edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-07-302743-2.

- ^ Creel, 1974 pp. 4–5 Shen Pu-hai: A Chinese Political Philosopher of the Fourth Century B.C.

- ^ Creel, What Is Taoism?, 94

- Creel, 1974 p.4, 119 Shen Pu-hai: A Chinese Political Philosopher of the Fourth Century B.C.

- Creel 1964: 155–6

- Herrlee G. Creel, 1974 p.119. Shen Pu-Hai: A Secular Philosopher of Administration, Journal of Chinese Philosophy Volume 1.

- Paul R. Goldin, p.16 Persistent Misconceptions about Chinese Legalism. https://www.academia.edu/24999390/Persistent_Misconceptions_about_Chinese_Legalism_

- ^ Ewan Ferlie, Laurence E. Lynn, Christopher Pollitt 2005 p.30, The Oxford Handbook of Public Management

- ^ Herrlee G. Creel, 1974 p.119. «Shen Pu-Hai: A Secular Philosopher of Administration», Journal of Chinese Philosophy Volume 1.

- ^ Creel, «The Origins of Statecraft in China, I», The Western Chou Empire, Chicago, pp.9–27

- ^ Otto B. Van der Sprenkel, «Max Weber on China», History and Theory 3 (1964), 357.

- ^ a b Bodde, Derke. «China: A Teaching Workbook». Columbia University.

- ^ Full text of the Northcote-Trevelyan Report Archived 22 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Walker, David (2003-07-09). «Fair game». The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 2003-07-09.

- ^ Mark W. Huddleston; William W. Boyer (1996). The Higher Civil Service in the United States: Quest for Reform. University of Pittsburgh Pre. p. 15. ISBN 0822974738.

- ^ Rung, Margaret C. (2002). Servants of the State: Managing Diversity & Democracy in the Federal Workforce, 1933-1953. University of Georgia Press. pp. 8, 200–201. ISBN 0820323624.

- ^ Griffin, Ricky W. CUSTOM Management: Principles and Practices, International Edition, 11th Edition. Cengage Learning UK, 08/2014

- ^ a b c Gomez-Mejia, Luis R.; David B. Balkin; Robert L. Cardy (2008). Management: People, Performance, Change (3 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-07-302743-2.

- ^

Rosenthal, Caitlin (2018). Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674988576. Retrieved 3 October 2020. - ^

Khurana, Rakesh (2010) [2007]. From Higher Aims to Hired Hands: The Social Transformation of American Business Schools and the Unfulfilled Promise of Management as a Profession. Princeton University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4008-3086-2. Retrieved 2013-08-24.When salaried managers first appeared in the large corporations of the late nineteenth century, it was not obvious who they were, what they did, or why they should be entrusted with the task of running corporations.

- ^ Groeger, Cristina V. (February 2018). «A «Good Mixer»: University Placement in Corporate America, 1890–1940″. History of Education Quarterly. 58 (1): 33–64. doi:10.1017/heq.2017.48. ISSN 0018-2680. S2CID 149037078.

- ^ Jacoby, S.M. (1985). «Employing Bureaucracy: Managers, Unions, and the Transformation of Work in American Industry, 1900-1945». Columbia University Press.

- ^ Cruikshank, L (1987). «A Delicate Experiment: The Harvard Business School, 1908-1945». Harvard Business School Press.

- ^ Groeger, Cristina V. (February 2018). «A «Good Mixer»: University Placement in Corporate America, 1890–1940″. History of Education Quarterly. 58 (1): 33–64. doi:10.1017/heq.2017.48. ISSN 0018-2680. S2CID 149037078.

- ^ Gilbreth, Lillian Moller. The Psychology of Management: The Function of the Mind in Determining, Teaching and Installing Methods of Least Waste – via Internet Archive.

- ^

Legge, David; Stanton, Pauline; Smyth, Anne (October 2005). «Learning management (and managing your own learning)». In Harris, Mary G. (ed.). Managing Health Services: Concepts and Practice. Marrickville, NSW: Elsevier Australia (published 2006). p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7295-3759-9. Retrieved 2014-07-11.The manager as bureaucrat is the guardian of roles, rules and relationships; his or her style of management relies heavily on working according to the book. In the Weberian tradition managers are necessary to coordinate the different roles that contribute to the production process and to mediate communication from head office to the shop floor and back. This style of management assumes a world view in which bureaucratic role is seen as separate from, and taking precedence over, other constructions of self (including the obligations of citizenship), at least for the duration if the working day.

- ^

Compare:

Ivanova, Galina Mikhailovna (17 July 2015). Raleigh, Donald J. (ed.). Labor Camp Socialism: The Gulag in the Soviet Totalitarian System. Translated by Flath, Carol A. (reprint ed.). Routledge (published 2015). ISBN 9781317466635. Retrieved 8 March 2021.The Gulag’s suspension of the development of productive forces was to have a long-term effect on the Soviet economy, and the master-slave production relations of the camps corrupted large sections of Soviet society. Hundreds of thousands of people who served as guards, managers, political workers, and so forth, in the Gulag system considered it completely normal to live off the daily exploitation of their fellow citizens […]. […] Furthermore, the nether regions of the camp economy incubated a special variety of Soviet manager and exploiter, who valued and nurtured everything except for the human being. This unique type of manager was to go to play a significant role in the economic policymaking of the Party and the government.

- ^

Kadar, Laszlo (February 2012). Such a Lucky Boy. Houston, Texas: Strategic Book Publishing (published 2012). p. 23. ISBN 9781612045825. Retrieved 8 March 2021.The ‘management’ of the camp [Mauthausen] did not care about the conditions of the ‘facilities.’ German SS (Schutzstaffel) was the management.

- ^

For example:

Hsing, You-tien (1993). Transnational Networks of Taiwanese Small Business and Chinese Local Governments: A New Pattern of Foreign Direct Investment. Vol. 2. Berkeley: University of California. p. 361. Retrieved 8 March 2021.Almost all the Taiwanese managers I interviewed stressed the importance of military-like management. The obligatory two year military service in Taiwan had well prepared these Taiwanese male managers with military style training techniques.

- ^

Peters, Thomas J. (1987). Thriving on Chaos: Handbook for a Management Revolution. Perennial Library. Vol. 7184. Knopf. ISBN 9780394560618. Retrieved 7 September 2020. - ^ Craig, S. (2009, January 29). Merrill Bonus Case Widens as Deal Struggles. Wall Street Journal. [3]

- ^

Manfred F.R. Kets de Vries: «The Dark Side of Leadership» – Business Strategy Review 14(3), Autumn p. 26 (2003). - ^ Jean-Louis Peaucelle (2015). Henri Fayol, the Manager. Routledge. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-1-317-31939-9.

- ^ «Management Roles | Principles of Management». courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ «Top 7 Behavioral Skills to Develop Within your Employees». ProSky — Learn Skills, Do Projects, Get Hired by Amazing Companies. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

External links[edit]

The purpose of this chapter is to:

- 1) Give you an overview of the evolution of management thought and theory.

- 2) Provide an understanding of management in the context of the modern-day world in which we reside.

The History of Management

The concept of management has been around for thousands of years. According to Pindur, Rogers, and Kim (1995), elemental approaches to management go back at least 3000 years before the birth of Christ, a time in which records of business dealings were first recorded by Middle Eastern priests. Socrates, around 400 BC, stated that management was a competency distinctly separate from possessing technical skills and knowledge (Higgins, 1991). The Romans, famous for their legions of warriors led by Centurions, provided accountability through the hierarchy of authority. The Roman Catholic Church was organized along the lines of specific territories, a chain of command, and job descriptions. During the Middle Ages, a 1,000 year period roughly from 476 AD through 1450 AD, guilds, a collection of artisans and merchants provided goods, made by hand, ranging from bread to armor and swords for the Crusades. A hierarchy of control and power, similar to that of the Catholic Church, existed in which authority rested with the masters and trickled down to the journeymen and apprentices. These craftsmen were, in essence, small businesses producing products with varying degrees of quality, low rates of productivity, and little need for managerial control beyond that of the owner or master artisan.

The Industrial Revolution, a time from the late 1700s through the 1800s, was a period of great upheaval and massive change in the way people lived and worked. Before this time, most people made their living farming or working and resided in rural communities. With the invention of the steam engine, numerous innovations occurred, including the automated movement of coal from underground mines, powering factories that now mass-produced goods previously made by hand, and railroad locomotives that could move products and materials across nations in a timely and efficient manner. Factories needed workers who, in turn, required direction and organization. As these facilities became more substantial and productive, the need for managing and coordination became an essential factor. Think of Henry Ford, the man who developed a moving assembly line to produce his automobiles. In the early 1900s, cars were put together by craftsmen who would modify components to fit their product. With the advent of standardized parts in 1908, followed by Ford’s revolutionary assembly line introduced in 1913, the time required to build a Model T fell from days to just a few hours (Klaess, 2020). From a managerial standpoint, skilled craftsmen were no longer necessary to build automobiles. The use of lower-cost labor and the increased production yielded by moving production lines called for the need to guide and manage these massive operations (Wilson, 2015). To take advantage of new technologies, a different approach to organizational structure and management was required.

The Scientific Era – Measuring Human Capital

With the emergence of new technologies came demands for increased productivity and efficiency. The desire to understand how to best conduct business centered on the idea of work processes. That is, managers wanted to study how the work was performed and the impact on productivity. The idea was to optimize the way the work was done. One of the chief architects of measuring human output was Frederick Taylor. Taylor felt that increasing efficiency and reducing costs were the primary objectives of management. Taylor’s theories centered on a formula that calculated the number of units produced in a specific time frame (DiFranceso and Berman, 2000). Taylor conducted time studies to determine how many units could be produced by a worker in so many minutes. He used a stopwatch, weight measurement scale, and tape measure to compute how far materials moved and how many steps workers undertook in the completion of their tasks (Wren and Bedeian, 2009). Examine the image below – one can imagine Frederick Taylor standing nearby, measuring just how many steps were required by each worker to hoist a sheet of metal from the pile, walk it to the machine, perform the task, and repeat, countless times a day. Beyond Taylor, other management theorists including Frank and Lilian Gilbreth, Harrington Emerson, and others expanded the concept of management reasoning with the goal of efficiency and consistency, all in the name of optimizing output. It made little difference whether the organization manufactured automobiles, mined coal, or made steel, the most efficient use of labor to maximize productivity was the goal.

The necessity to manage not just worker output but to link the entire organization toward a common objective began to emerge. Management, out of necessity, had to organize multiple complex processes for increasingly large industries. Henri Fayol, a Frenchman, is credited with developing the management concepts of planning, organizing, coordination, command, and control (Fayol, 1949), which were the precursors of today’s four basic management principles of planning, organizing, leading, and controlling.

Employees and the Organization

With the increased demand for production brought about by scientific measurement, conflict between labor and management was inevitable. The personnel department, forerunner of today’s human resources department, emerged as a method to slow down the demand for unions, initiate training programs to reduce employee turnover, and to acknowledge workers’ needs beyond the factory floor. The idea that to increase productivity, management should factor the needs of their employees by developing work that was interesting and rewarding burst on the scene (Nixon, 2003) and began to be part of management thinking. Numerous management theorists were starting to consider the human factor. Two giants credited with moving management thought in the direction of understanding worker needs were Douglas McGregor and Frederick Herzberg. McGregor’s Theory X factor was management’s assumption that workers disliked work, were lazy, lacked self-motivation, and therefore had to be persuaded by threats, punishment, or intimidation to exert the appropriate effort. His Theory Y factor was the opposite. McGregor felt that it was management’s job to develop work that gave the employees a feeling of self-actualization and worth. He argued that with more enlightened management practices, including providing clear goals to the employees and giving them the freedom to achieve those goals, the organization’s objectives and those of the employees could simultaneously be achieved (Koplelman, Prottas, & Davis, 2008).

Frederick Herzberg added considerably to management thinking on employee behavior with his theory of worker motivation. Herzberg contended that most management driven motivational efforts, including increased wages, better benefits, and more vacation time, ultimately failed because while they may reduce certain factors of job dissatisfaction (the things workers disliked about their jobs), they did not increase job satisfaction. Herzberg felt that these were two distinctly different management problems. Job satisfaction flowed from a sense of achievement, the work itself, a feeling of accomplishment, a chance for growth, and additional responsibility (Herzberg, 1968). One enduring outcome of Herzberg’s work was the idea that management could have a positive influence on employee job satisfaction, which, in turn, helped to achieve the organization’s goals and objectives.

The concept behind McGregor, Herzberg, and a host of other management theorists was to achieve managerial effectiveness by utilizing people more effectively. Previous management theories regarding employee motivation (thought to be directly correlated to increased productivity) emphasized control, specialized jobs, and gave little thought to employees’ intrinsic needs. Insights that considered the human factor by utilizing theories from psychology now became part of management thinking. Organizational changes suggested by management thinkers who saw a direct connection between improved work design, self-actualization, and challenging work began to take hold in more enlightened management theory.

The Modern Era

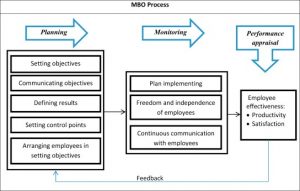

Koontz and O’Donnell (1955) defined management as “the function of getting things done through others (p. 3). One commanding figure stood above all others and is considered the father of modern management (Edersheim, (2007). That individual was Peter Drucker. Drucker, an author, educator, and management consultant is widely credited with developing the concept of Managing By Objective or MBO (Wren & Bedeian, 2009). Management by Objective is the process of defining specific objectives necessary to achieve the organization’s goals. The beauty of the MBO concept was that it provided employees a clear view of their organization’s objectives and defined their individual responsibilities. For example, let’s examine a company’s sales department. One of the firm’s organizational goals might be to grow sales (sometimes referred to as revenue) by 5% the next fiscal year. The first step, in consultation with the appropriate people in the sales department, would be to determine if that 5% goal is realistic and attainable. If so, the 5% sales growth objective is shared with the entire sales department and individuals are assigned specific targets. Let’s assume this is a regional firm that has seven sales representatives. Each sales rep is charged with a specific goal that, when combined with their colleagues, rolls up to the 5% sales increase. The role of management is now to support, monitor, and evaluate performance. Should a problem arise, it is management’s responsibility to take corrective action. If the 5% sales objective is met or exceeded, rewards can be shared. This MBO cycle applies to every department within an organization, large or small, and never-ending.

The MBO Process

Drucker’s contributions to modern management thinking went far beyond the MBO concept. Throughout his long life, Drucker argued that the singular role of business was to create a customer and that marketing and innovation were its two essential functions. Consider the Apple iPhone. From that single innovation came thousands of jobs in manufacturing plants, iPhone sales in stores around the globe, and profits returned to Apple, enabling them to continue the innovation process. Another lasting Drucker observation was that too many businesses failed to ask the question “what business are we in?” (Drucker, 2008, p. 103). On more than one occasion, a company has faltered, even gone out of business, after failing to recognize that their industry was changing or trying to expand into new markets beyond their core competency. Consider the fate of Blockbuster, Kodak, Blackberry, or Yahoo.

Management theories continued to evolve with additional concepts being put forth by other innovative thinkers. Henry Mintzberg is remembered for blowing holes in the idea that managers were iconic individuals lounging in their offices, sitting back and contemplating big-picture ideas. Mintzberg observed that management was hard work. Managers were on the move attending meetings, managing crises, and interacting with internal and external contacts. Further, depending on the exact nature of their role, managers fulfilled multiple duties including that of spokesperson, leader, resource allocator, and negotiator (Mintzberg, 1973). In the 1970s, Tom Peters and Robert Waterman traveled the globe exploring the current best management practices of the time. Their book, In Search of Excellence, spelled out what worked in terms of managing organizations. Perhaps the most relevant finding was their assertion that culture counts. They found that the best managed companies had a culture that promoted transparency, openly shared information, and effectively managed communication up and down the organizational hierarchy (Allison, 2014). The well managed companies Peterson and Waterman found were built in large part on the earlier managerial ideas of McGregor and Herzberg. Top-notch organizations succeeded by providing meaningful work and positive affirmation of their employees’ worth.

Others made lasting contributions to modern management thinking. Steven Covey’s The Seven Habits of Highly Successful People, Peter Senge’s The Fifth Discipline, and Jim Collins and Jerry Porras’s Built to Last are among a pantheon of bestselling books on management principles. Among the iconic thinkers of this era was Michael Porter. Porter, a professor at the Harvard Business School, is widely credited with taking the concept of strategic reasoning to another level. Porter tackled the question of how organizations could effectively compete and achieve a long-term competitive advantage. He contended that there were just three ways a firm could gain such advantage: 1) a cost-based leadership – become the lowest cost producer, 2) valued-added leadership – offer a differentiated product or service for which a customer is willing to pay a premium price, and 3) focus – compete in a niche market with laser-like fixation (Dess & Davis, 1984). Name a company that fits these profiles: How about Walmart for low-cost leadership. For value-added leadership, many think of Apple. Focus leadership is a bit more challenging. What about Whole Foods before being acquired by Amazon? Porter’s thinking on competition and competitive advantage has become timeless principles of strategic management still used today. Perhaps Porter’s most significant contribution to modern management thinking is the connection between a firm’s choice of strategy and its financial performance. Should an organization fail to select and properly execute one of the three basic strategies, it faces the grave danger of being stuck in the middle – its prices are too high to compete based on price or its products lack features unique enough to entice customers to pay a premium price. Consider the fate of Sears and Roebuck, J.C. Penny, K-Mart, and Radio Shack, organizations that failed to navigate the evolving nature of their businesses.

The 21st Century

Managers in the 21st century must confront challenges their counterparts of even a few years ago could hardly imagine. The ever-growing wave of technology, the impact of artificial intelligence, the evolving nature of globalization, and the push-pull tug of war between the firm’s stakeholder and shareholder interests are chief among the demands today’s managers will face.

Technology

Much has been written about the exponential growth of technology. It has been reported that today’s iPhone has more than 100,000 times the computing power of the computer that helped land a man on the moon (Kendall, 2019). Management today has to grapple with the explosion of data now available to facilitate business decisions. Data analytics, the examination of data sets, provides information to help managers better understand customer behavior, customer wants and needs, personalize the delivery of marketing messages, and track visits to online web sites. Developing an understanding of how to use data analytics without getting bogged down will be a significant challenge for the 21st century manager. Collecting, organizing, utilizing data in a logical, timely, and cost-effective manner is creating an entirely new paradigm of managerial competence. In addition to data analytics, cybersecurity, drones, and virtual reality are new, exciting technologies and offer unprecedented change to the way business is conducted. Each of these opportunities requires a new degree of managerial competence which, in turn, creates opportunities for the modern-day manager.

Artificial Intelligence

Will robots replace workers? To be sure, this has already happened to some degree in many industries. However, while some jobs will be lost to AI, a host of others will emerge, requiring a new level of management expertise. AI has the ability to eliminate mundane tasks and free managers to focus on the crux of their job. Human skills such as empathy, teaching and coaching employees, focusing on people development and freeing time for creative thinking will become increasingly important as AI continues to develop as a critically important tool for today’s manager.

Globalization

Globalization has been defined as the interdependence of the world’s economies and has been on a steady march forward since the end of World War II. As markets mature, more countries are moving from the emerging ranks and fostering a growing middle class of consumers. This rising new class has the purchasing power to acquire goods and services previously unattainable, and companies around the globe have expanded outside their national borders to meet those demands. Managing in the era of globalization brought a new set of challenges. Adapting to new cultures, navigating the puzzle of different laws, tariffs, import/export regulations, human resource issues, logistics, marketing messages, supply chain management, currency, foreign investment, and government intervention are among the demands facing the 21st century global manager. Despite these enormous challenges, trade among the world’s nations has grown at an unprecedented rate. World trade jumped from around 20% of world GDP in 1960 to almost 60% in 2017.

Trade as a Percent of Global GDP

Despite its stupendous growth, globalization has its share of critics. Chief among them is that globalization has heightened the disparity between the haves and the have-nots in society. Opponents of globalization argue that in many cases, jobs have been lost to developing nations with lower prevailing wage rates. Additionally, inequality has worsened with the wealthiest consuming a disproportionate percent of the world’s resources (Collins, 2015). Proponents counter that on the macro level, globalization creates more jobs than are lost, more people are lifted out of poverty, and expansion globally enables companies to become more competitive on the world stage.

Since the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States in 2016 and Great Britain’s decision to exit the European Union, the concept of nationalism has manifested in many nations around the globe. Traditional obstacles to expanding outside one’s home country plus a host of new difficulties such as unplanned trade barriers, blocked acquisitions, and heightened scrutiny from regulators have added to the burdens of managing in the 21st century. The stage has been set for a new generation of managers with the skills to deal with this new, complex business environment. In the 20th century, the old command and control model of management may have worked. However, today, with technology, artificial intelligence, globalization, nationalism, and multiple other hurdles, organizations will continue the move toward a flatter, more agile organizational structure run by managers with the appropriate 21st century skills.

Stakeholder versus Shareholder

What is a stakeholder in a business, and what is a shareholder? The difference is important. Banton (2020) noted that shareholders, by owning even a single share of stock, has a stake in the company. The shareholder first view was put forth by the economist Milton Friedman (1962) who stated that “There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it engages in open and free competition, without deception or fraud” (p. 133). In other words, maximize profits so long as the pursuit of profit is done so legally and ethically. An alternate view is that a stakeholder has a clear interest in how the company performs, and this interest may stem from reasons other than the increase in the value of their share(s) of stock. Edward Freeman (1999), a philosopher and academic advanced his stakeholder theory contending that the idea was the success of an organization relied on its ability to manage a complex web of relationships with several different stakeholders. These stakeholders could be an employee, a customer, an investor, a supplier, the community in which the firm operates, and the government that collects taxes and stipulates the rules and regulations by which the company must operate. Which theory is correct? According to Emiliani (2001), businesses in the United States typically followed the shareholder model, while in other countries, firms tend to follow the stakeholder model. Events in the past decade have created a shift toward the shareholder model in the United States. The financial crisis of 2008/2009, global warming, the debate between globalization and nationalism, the push for green energy, a spate of natural disasters, and the world-wide impact of health crises such as AIDS, Ebola, the SARS virus and the Coronavirus have fostered a move toward a redefinition of the purpose of a corporation. In the coming decades, those companies that thrive and grow will be the ones that invest in their people, society, and the communities in which they operate. The managers of the 21st century must build on the work of those that proceeded them. Managers in the 21st century would do well if they heeded the words famously used by Isaac Newton who said “If I have seen a little further, it is because I stand on the shoulders of giants” (Harel, 2012).

Critical Thinking Questions

In what way has the role of manager changed in the past twenty years?

With the historical perspective of management in mind, reflect on changes you foresee in the manager’s role in the next 20 years?

Reflect on some of the significant issues you have witnessed in the past few years. Among thoughts to consider are global warming, green energy, global health crisis, globalization, nationalism, national debt, or an issue of your choosing. What role do you see business and management playing in effectively dealing with that specific issue?

For each of these answers you should provide three elements.

- General Answer. Give a general response to what the question is asking, or make your argument to what the question is asking.

- Outside Resource. Provide a quotation from a source outside of this textbook. This can be an academic article, news story, or popular press. This should be something that supports your argument. Use the sandwich technique explained below and cite your source in APA in text and then a list of full text citations at the end of the homework assignment of all three sources used.

- Personal Story. Provide a personal story that illustrates the point as well. This should be a personal experience you had, and not a hypothetical. Talk about a time from your personal, professional, family, or school life. Use the sandwich technique for this as well, which is explained below.

Use the sandwich technique: