Recent News

library, traditionally, collection of books used for reading or study, or the building or room in which such a collection is kept. The word derives from the Latin liber, “book,” whereas a Latinized Greek word, bibliotheca, is the origin of the word for library in German, Russian, and the Romance languages.

From their historical beginnings as places to keep the business, legal, historical, and religious records of a civilization, libraries have emerged since the middle of the 20th century as a far-reaching body of information resources and services that do not even require a building. Rapid developments in computers, telecommunications, and other technologies have made it possible to store and retrieve information in many different forms and from any place with a computer and a telephone connection. The terms digital library and virtual library have begun to be used to refer to the vast collections of information to which people gain access over the Internet, cable television, or some other type of remote electronic connection.

This article provides a history of libraries from their founding in the ancient world through the latter half of the 20th century, when both technological and political forces radically reshaped library development. It offers an overview of several types of traditional libraries and explains how libraries collect, organize, and make accessible their collections. Further discussion of the application of the theory and technology of information science in libraries and related fields is included in the article information processing.

The changing role of libraries

Libraries are collections of books, manuscripts, journals, and other sources of recorded information. They commonly include reference works, such as encyclopaedias that provide factual information and indexes that help users find information in other sources; creative works, including poetry, novels, short stories, music scores, and photographs; nonfiction, such as biographies, histories, and other factual reports; and periodical publications, including magazines, scholarly journals, and books published as part of a series. As home use of records, CD-ROMs, and audiotapes and videotapes has increased, library collections have begun to include these and other forms of media, too.

Britannica Quiz

Ancient Libraries and Archives Quiz

Libraries were involved early in exploiting information technologies. For many years libraries have participated in cooperative ventures with other libraries. Different institutions have shared cataloging and information about what each has in its collection. They have used this shared information to facilitate the borrowing and lending of materials among libraries. Librarians have also become expert in finding information from on-line and CD-ROM databases.

As society has begun to value information more highly, the so-called information industry has developed. This industry encompasses publishers, software developers, on-line information services, and other businesses that package and sell information products for a profit. It provides both an opportunity and a challenge to libraries. On the one hand, as more information becomes available in electronic form, libraries no longer have to own an article or a certain piece of statistical information, for example, to obtain it quickly for a user. On the other hand, members of the information industry seem to be offering alternatives to libraries. A student with her own computer can now go directly to an on-line service to locate, order, and receive a copy of an article without ever leaving her home.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content.

Subscribe Now

Although the development of digital libraries means that people do not have to go to a building for some kinds of information, users still need help to locate the information they want. In a traditional library building, a user has access to a catalog that will help locate a book. In a digital library, a user has access to catalogs to find traditional library materials, but much of the information on, for example, the Internet can not be found through one commonly accepted form of identification. This problem necessitates agreement on standard ways to identify pieces of electronic information (sometimes called meta-data) and the development of codes (such as HTML [Hypertext Markup Language] and SGML [Standard Generalized Markup Language]) that can be inserted into electronic texts.

For many years libraries have bought books and periodicals that people can borrow or photocopy for personal use. Publishers of electronic databases, however, do not usually sell their product, but instead they license it to libraries (or sites) for specific uses. They usually charge libraries a per-user fee or a per-unit fee for the specific amount of information the library uses. When libraries do not own these resources, they have less control over whether older information is saved for future use—another important cultural function of libraries. In the electronic age, questions of copyright, intellectual property rights, and the economics of information have become increasingly important to the future of library service.

Increased availability of electronic information has led libraries, particularly in schools, colleges, and universities, to develop important relationships to their institutions’ computer centres. In some places the computer centre is the place responsible for electronic information and the library is responsible for print information. In some educational institutions librarians have assumed responsibility for both the library collection and computer services.

As technology has changed and allowed ever new ways of creating, storing, organizing, and providing information, public expectation of the role of libraries has increased. Libraries have responded by developing more sophisticated on-line catalogs that allow users to find out whether or not a book has been checked out and what other libraries have it. Libraries have also found that users want information faster, they want the full text of a document instead of a citation to it, and they want information that clearly answers their questions. In response, libraries have provided Selective Dissemination of Information (SDI) services, in which librarians choose information that may be of interest to their users and forward it to them before the users request it.

The changes in libraries outlined above originated in the United States and other English-speaking countries. But electronic networks do not have geographic boundaries, and their influence has spread rapidly. With Internet connections in Peking (Beijing), Moscow, and across the globe, people who did not have access to traditional library services now have the opportunity to get information about all types of subjects, free of political censorship.

As libraries have changed, so, too, has the role of the librarian. Increasingly librarians have assumed the role of educator to teach their users how to find information both in the library and over electronic networks. Public librarians have expanded their roles by providing local community information through publicly accessible computing systems. Some librarians are experts about computers and computer software. Others are concerned with how computer technologies can preserve the human cultural records of the past or assure that library collections on crumbling paper or in old computer files can still be used by people many centuries in the future.

The work of librarians has also moved outside library walls. Librarians have begun to work in the information industry as salespeople, designers of new information systems, researchers, and information analysts. They also are found in such fields as marketing and public relations and in such organizations as law firms, where staffs need rapid access to information.

Although libraries have changed significantly over the course of history, as the following section demonstrates, their cultural role has not. Libraries remain responsible for acquiring or providing access to books, periodicals, and other media that meet the educational, recreational, and informational needs of their users. They continue to keep the business, legal, historical, and religious records of a civilization. They are the place where a toddler can hear his first story and a scholar can carry out her research.

Leigh S. Estabrook

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a virtual space, or both. A library’s collection can include printed materials and other physical resources in many formats such as DVD, CD and cassette as well as access to information, music or other content held on bibliographic databases.

A library, which may vary widely in size, may be organized for use and maintained by a public body such as a government; an institution such as a school or museum; a corporation; or a private individual. In addition to providing materials, libraries also provide the services of librarians who are trained and experts at finding, selecting, circulating and organizing information and at interpreting information needs, navigating and analyzing very large amounts of information with a variety of resources.

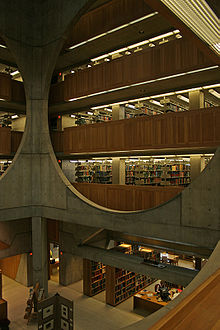

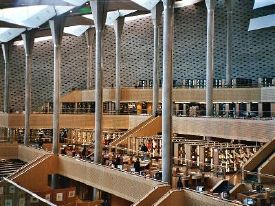

Library buildings often provide quiet areas for studying, as well as common areas for group study and collaboration, and may provide public facilities for access to their electronic resources; for instance: computers and access to the Internet. The library’s clientele and services offered vary depending on its type: users of a public library have different needs from those of a special library or academic library, for example. Libraries may also be community hubs, where programs are delivered and people engage in lifelong learning. Modern libraries extend their services beyond the physical walls of a building by providing material accessible by electronic means, including from home via the Internet.

The services that libraries offer are variously described as library services, information services, or the combination «library and information services», although different institutions and sources define such terminology differently.

Etymology[edit]

The term library is based on the Latin word liber for ‘book’ or ‘document’, contained in Latin libraria ‘collection of books’ and librarium ‘container for books’. Other modern languages use derivations from Ancient Greek βιβλιοθήκη (bibliothēkē), originally meaning ‘book container’, via Latin bibliotheca (cf. French bibliothèque or German Bibliothek).[1]

History[edit]

The history of libraries began with the first efforts to organize collections of documents.[2] The first libraries consisted of archives of the earliest form of writing—the clay tablets in cuneiform script discovered in Sumer, some dating back to 2600 BC. Private or personal libraries made up of written books appeared in classical Greece in the 5th century BC. In the 6th century, at the very close of the Classical period, the great libraries of the Mediterranean world remained those of Constantinople and Alexandria.

The Fatimids (r. 909–1171) also possessed many great libraries within their domains. The historian Ibn Abi Tayyi’ describes their palace library, which probably contained the largest collection of literature on earth at the time, as a «wonder of the world». Throughout history, along with bloody massacres, the destruction of libraries has been critical for conquerors who wish to destroy every trace of the vanquished community’s recorded memory. A prominent example of this can be found in the Mongol massacre of the Nizaris at Alamut in 1256 and the torching of their library, «the fame of which», boasts the conqueror Juwayni, «had spread throughout the world».[3]

The libraries of Timbuktu were established in the fourteenth century and attracted scholars from all over the world.[4]

Functions[edit]

Libraries may provide physical or digital access to material, and may be a physical location or a virtual space, or both. A library’s collection can include books, periodicals, newspapers, manuscripts, films, maps, prints, documents, microform, CDs, cassettes, videotapes, DVDs, Blu-ray Discs, e-books, audiobooks, databases, table games, video games and other formats. Libraries range widely in size, up to millions of items.

Libraries often provide quiet areas for studying, and they also often offer common areas to facilitate group study and collaboration. Libraries often provide public facilities for access to their electronic resources and the Internet. Public and institutional collections and services may be intended for use by people who choose not to—or cannot afford to—purchase an extensive collection themselves, who need material no individual can reasonably be expected to have, or who require professional assistance with their research.[5]

Services offered by a library are variously described as library services, information services, or the combination «library and information services», although different institutions and sources define such terminology differently. Organizations or departments are often called by one of these names.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12]

Organization[edit]

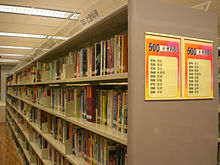

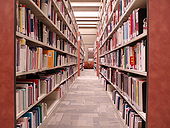

Library shelves in Hong Kong, showing numbers of the classification scheme to help readers locate works in that section

Most libraries have materials arranged in a specified order according to a library classification system, so that items may be located quickly and collections may be browsed efficiently.[13] Some libraries have additional galleries beyond the public ones, where reference materials are stored. These reference stacks may be open to selected members of the public. Others require patrons to submit a «stack request», which is a request for an assistant to retrieve the material from the closed stacks: see List of closed stack libraries.

Larger libraries are often divided into departments staffed by both paraprofessionals and professional librarians.

- Circulation (or Access Services) – Handles user accounts and the loaning/returning and shelving of materials.[14]

- Collection Development – Orders materials and maintains materials budgets.

- Reference – Staffs a reference desk answering questions from users (using structured reference interviews), instructing users, and developing library programming. Reference may be further broken down by user groups or materials; common collections are children’s literature, young adult literature, and genealogy materials.

- Electronic Library — Responsible for providing information to users via electronic means

- Technical Services – Works behind the scenes cataloging and processing new materials and deaccessioning weeded materials.

- Stacks Maintenance – Re-shelves materials that have been returned to the library after patron use and shelves materials that have been processed by Technical Services. Stacks Maintenance also shelf reads the material in the stacks to ensure that it is in the correct library classification order.

Basic tasks in library management include the planning of acquisitions (which materials the library should acquire, by purchase or otherwise), library classification of acquired materials, preservation of materials (especially rare and fragile archival materials such as manuscripts), the deaccessioning of materials, patron borrowing of materials, and developing and administering library computer systems.[15] More long-term issues include the planning of the construction of new libraries or extensions to existing ones, and the development and implementation of outreach services and reading-enhancement services (such as adult literacy and children’s programming). Library materials like books, magazines, periodicals, CDs, etc. are managed by Dewey Decimal Classification Theory and modified Dewey Decimal Classification Theory is more practical reliable system for library materials management.[16]

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has published several standards regarding the management of libraries through its Technical Committee 46 (TC 46),[17] which is focused on «libraries, documentation and information centers, publishing, archives, records management, museum documentation, indexing and abstracting services, and information science». The following is a partial list of some of them:[18]

- ISO 2789:2006 Information and documentation—International library statistics

- ISO 11620:1998 Information and documentation—Library performance indicators

- ISO 11799:2003 Information and documentation—Document storage requirements for archive and library materials

- ISO 14416:2003 Information and documentation—Requirements for binding of books, periodicals, serials, and other paper documents for archive and library use—Methods and materials

- ISO/TR 20983:2003 Information and documentation—Performance indicators for electronic library services

Usage[edit]

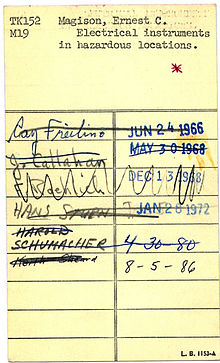

Until the advent of digital catalogues, card catalogues were the traditional method of organizing the list of resources and their location within a large library.

Some patrons may not know how to fully use the library’s resources. This can be due to individuals’ unease in approaching a staff member. Ways in which a library’s content is displayed or accessed may have the most impact on use. An antiquated or clumsy search system, or staff unwilling or untrained to engage their patrons, will limit a library’s usefulness. In the public libraries of the United States, beginning in the 19th century, these problems drove the emergence of the library instruction movement, which advocated library user education.[19] One of the early leaders was John Cotton Dana.[20] The basic form of library instruction is sometimes known as information literacy.[21]

Libraries should inform their users of what materials are available in their collections and how to access that information. Before the computer age, this was accomplished by the card catalogue—a cabinet (or multiple cabinets) containing many drawers filled with index cards that identified books and other materials. In a large library, the card catalogue often filled a large room.[citation needed]

The emergence of the Internet, however, has led to the adoption of electronic catalogue databases (often referred to as «webcats» or as online public access catalogues, OPACs), which allow users to search the library’s holdings from any location with Internet access.[22] This style of catalogue maintenance is compatible with new types of libraries, such as digital libraries and distributed libraries, as well as older libraries that have been retrofitted. Large libraries may be scattered within multiple buildings across a town, each having multiple floors, with multiple rooms housing their resources across a series of shelves called bays. Once a user has located a resource within the catalogue, they must then use navigational guidance to retrieve the resource physically, a process that may be assisted through signage, maps, GPS systems, or RFID tagging.[citation needed]

Finland has the highest number of registered book borrowers per capita in the world. Over half of Finland’s population are registered borrowers.[23] In the US, public library users have borrowed on average roughly 15 books per user per year from 1856 to 1978. From 1978 to 2004, book circulation per user declined approximately 50%. The growth of audiovisuals circulation, estimated at 25% of total circulation in 2004, accounts for about half of this decline.[24]

Relationship with the Internet[edit]

A library may make use of the Internet in a number of ways, from creating its own library website to making the contents of its catalogues searchable online. Some specialised search engines such as Google Scholar offer a way to facilitate searching for academic resources such as journal articles and research papers. The Online Computer Library Center allows anyone to search the world’s largest repository of library records through its WorldCat online database.[25] Websites such as LibraryThing and Amazon provide abstracts, reviews, and recommendations of books.[25] Libraries provide computers and Internet access to allow people to search for information online.[26] Online information access is particularly attractive to younger library users.[27][28][29][30][31]

Digitization of books, particularly those that are out-of-print, in projects such as Google Books provides resources for library and other online users. Due to their holdings of valuable material, some libraries are important partners for search engines such as Google in realizing the potential of such projects and have received reciprocal benefits in cases where they have negotiated effectively.[32] As the prominence of and reliance on the Internet has grown, library services have moved the emphasis from mainly providing print resources to providing more computers and more Internet access.[33] Libraries face a number of challenges in adapting to new ways of information seeking that may stress convenience over quality,[34] reducing the priority of information literacy skills.[35] The potential decline in library usage, particularly reference services,[36] puts the necessity for these services in doubt.

Library scholars have acknowledged that libraries need to address the ways that they market their services if they are to compete with the Internet and mitigate the risk of losing users.[37] This includes promoting the information literacy skills training considered vital across the library profession.[35][38][39] Many US based research librarians rely on the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy in order to guide students and faculty in research.[40] However, marketing of services has to be adequately supported financially in order to be successful. This can be problematic for library services that are publicly funded and find it difficult to justify diverting tight funds to apparently peripheral areas such as branding and marketing.[41]

The privacy aspect of library usage in the Internet age is a matter of growing concern and advocacy; privacy workshops are run by the Library Freedom Project which teach librarians about digital tools (such as the Tor network) to thwart mass surveillance.[42][43][44]

Librarians[edit]

Libraries are usually staffed by a combination of professionally trained librarians, paraprofessional staff sometimes called library technicians, and support staff. Some topics related to the education of librarians and allied staff include accessibility of the collection, acquisition of materials, arrangement and finding tools, the book trade, the influence of the physical properties of the different writing materials, language distribution, role in education, rates of literacy, budgets, staffing, libraries for specially targeted audiences, architectural merit, patterns of usage, the role of libraries in a nation’s cultural heritage, and the role of government, church or private sponsorship. Since the 1960s, issues of computerization and digitization have arisen.[2]

Types[edit]

Many institutions make a distinction between a circulating or lending library, where materials are expected and intended to be loaned to patrons, institutions, or other libraries, and a reference library where material is not lent out. Travelling libraries, such as the early horseback libraries of eastern Kentucky[45] and bookmobiles, are generally of the lending type. Modern libraries are often a mixture of both, containing a general collection for circulation, and a reference collection which is restricted to the library premises. Also, increasingly, digital collections enable broader access to material that may not circulate in print, and enables libraries to expand their collections even without building a larger facility. Lamba (2019) reinforced this idea by observing that «today’s libraries have become increasingly multi-disciplinary, collaborative and networked» and that applying Web 2.0 tools to libraries would «not only connect the users with their community and enhance communication but will also help the librarians to promote their library’s activities, services, and products to target both their actual and potential users».[46]

Academic libraries[edit]

Academic libraries are generally located on college and university campuses and primarily serve the students and faculty of that and other academic institutions. Some academic libraries, especially those at public institutions, are accessible to members of the general public in whole or in part. Library services are sometimes extended to the general public at a fee, some academic libraries create such services in order to enhance literacy levels in their communities.

Academic libraries are libraries that are hosted in post-secondary educational institutions, such as colleges and universities. Their main functions are to provide support in research, consultancy and resource linkage for students and faculty of the educational institution. Academic libraries house current, reliable and relevant information resources spread through all the disciplines which serve to assuage the information requirements of students and faculty. In cases where not all books are housed some libraries have E-resources, where they subscribe for a given institution they are serving, in order to provide backups and additional information that is not practical to have available as hard copies. Furthermore, most libraries collaborate with other libraries in exchange of books.

Specific course-related resources are usually provided by the library, such as copies of textbooks and article readings held on ‘reserve’ (meaning that they are loaned out only on a short-term basis, usually a matter of hours). Some academic libraries provide resources not usually associated with libraries, such as the ability to check out laptop computers, web cameras, or scientific calculators.

Academic libraries offer workshops and courses outside of formal, graded coursework, which are meant to provide students with the tools necessary to succeed in their programs.[47] These workshops may include help with citations, effective search techniques, journal databases, and electronic citation software. These workshops provide students with skills that can help them achieve success in their academic careers (and often, in their future occupations), which they may not learn inside the classroom.

The academic library provides a quiet study space for students on campus; it may also provide group study space, such as meeting rooms. In North America, Europe, and other parts of the world, academic libraries are becoming increasingly digitally oriented. The library provides a «gateway» for students and researchers to access various resources, both print/physical and digital.[48] Academic institutions are subscribing to electronic journals databases, providing research and scholarly writing software, and usually provide computer workstations or computer labs for students to access journals, library search databases and portals, institutional electronic resources, Internet access, and course- or task-related software (i.e. word processing and spreadsheet software). Some academic libraries take on new roles, for instance, acting as an electronic repository for institutional scholarly research and academic knowledge, such as the collection and curation of digital copies of students’ theses and dissertations.[49][50] Moreover, academic libraries are increasingly acting as publishers on their own on a not-for-profit basis, especially in the form of fully Open Access institutional publishers.[51]

Children’s libraries[edit]

A children’s library in Montreal, Quebec, Canada in 1943

Children’s libraries are special collections of books intended for juvenile readers and usually kept in separate rooms of general public libraries.[52] Some children’s libraries have entire floors or wings dedicated to them in bigger libraries while smaller ones may have a separate room or area for children. They are an educational agency seeking to acquaint the young with the world’s literature and to cultivate a love for reading. Their work supplements that of the public schools.[53][54]

Services commonly provided by public libraries may include storytelling sessions for infants, toddlers, preschool children, or after-school programs, all with an intention of developing early literacy skills and a love of books. One of the most popular programs offered in public libraries are summer reading programs for children, families, and adults.[55]

Another popular reading program for children is PAWS TO READ or similar programs where children can read to certified therapy dogs. Since animals are a calming influence and there is no judgment, children learn confidence and a love of reading. Many states have these types of programs: parents need simply ask their librarian to see if it is available at their local library.[56]

National libraries[edit]

A national or state library serves as a national repository of information, and has the right of legal deposit, which is a legal requirement that publishers in the country need to deposit a copy of each publication with the library. Unlike a public library, a national library rarely allows citizens to borrow books. Often, their collections include numerous rare, valuable, or significant works. There are wider definitions of a national library, putting less emphasis on the repository character.[57][58] The first national libraries had their origins in the royal collections of the sovereign or some other supreme body of the state.

Many national libraries cooperate within the National Libraries Section of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) to discuss their common tasks, define and promote common standards, and carry out projects helping them to fulfill their duties. The national libraries of Europe participate in The European Library which is a service of the Conference of European National Librarians (CENL).[59]

Public lending libraries[edit]

A public library provides services to the general public. If the library is part of a countywide library system, citizens with an active library card from around that county can use the library branches associated with the library system. A library can serve only their city, however, if they are not a member of the county public library system. Much of the materials located within a public library are available for borrowing. The library staff decides upon the number of items patrons are allowed to borrow, as well as the details of borrowing time allotted. Typically, libraries issue library cards to community members wishing to borrow books. Often visitors to a city are able to obtain a public library card.

Many public libraries also serve as community organizations that provide free services and events to the public, such as reading groups and toddler story time. For many communities, the library is a source of connection to a vast world, obtainable knowledge and understanding, and entertainment. According to a study by the Pennsylvania Library Association, public library services play a major role in fighting rising illiteracy rates among youths.[60] Public libraries are protected and funded by the public they serve.

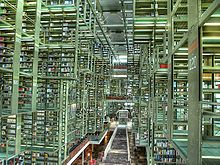

As the number of books in libraries have steadily increased since their inception, the need for compact storage and access with adequate lighting has grown. The stack system involves keeping a library’s collection of books in a space separate from the reading room. This arrangement arose in the 19th century. Book stacks quickly evolved into a fairly standard form in which the cast iron and steel frameworks supporting the bookshelves also supported the floors, which often were built of translucent blocks to permit the passage of light (but were not transparent, for reasons of modesty). The introduction of electric lights had a huge impact on lighting in libraries. The use of glass floors was largely discontinued, though floors were still often composed of metal grating to allow air to circulate in multi-story stacks. As more space was needed, a method of moving shelves on tracks (compact shelving) was introduced to cut down on otherwise wasted aisle space.

Library 2.0, a term coined in 2005, is the library’s response to the challenge of Google and an attempt to meet the changing needs of users by using Web 2.0 technology. Some of the aspects of Library 2.0 include, commenting, tagging, bookmarking, discussions, use of online social networks by libraries, plug-ins, and widgets.[61] Inspired by Web 2.0, it is an attempt to make the library a more user-driven institution.

Despite the importance ascribed to public libraries, their budgets are often cut by legislatures. In some cases, funding has dwindled so much that libraries have been forced to cut their hours and release employees.[62]

Reference libraries[edit]

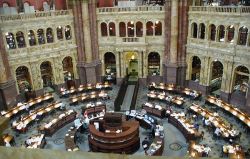

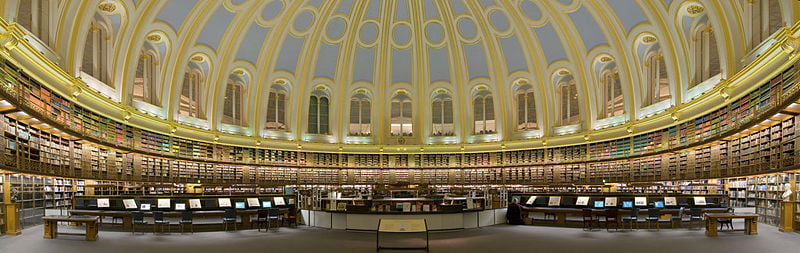

A reference library does not lend books and other items; instead, they can only be read at the library itself. Typically, such libraries are used for research purposes, for example at a university. Some items at reference libraries may be historical and even unique. Many lending libraries contain a «reference section», which holds books, such as dictionaries, which are common reference books, and are therefore not lent out.[63] Such reference sections may be referred to as «reading rooms», which may also include newspapers and periodicals.[64] An example of a reading room is the Hazel H. Ransom Reading Room at the Harry Ransom Center of the University of Texas at Austin, which maintains the papers of literary agent Audrey Wood.[65]

Research libraries[edit]

A research library is a collection of materials on one or more subjects.[66] A research library supports scholarly or scientific research and will generally include primary as well as secondary sources; it will maintain permanent collections and attempt to provide access to all necessary materials. A research library is most often an academic or national library, but a large special library may have a research library within its special field, and a very few of the largest public libraries also serve as research libraries. A large university library may be considered a research library; and in North America, such libraries may belong to the Association of Research Libraries.[67] In the United Kingdom, they may be members of Research Libraries UK (RLUK).[68] Particularly important collections in England may be designated by Arts Council England.[69]

A research library can be either a reference library, which does not lend its holdings, or a lending library, which does lend all or some of its holdings. Some extremely large or traditional research libraries are entirely reference in this sense, lending none of their materials; most academic research libraries, at least in the US and the UK, now lend books, but not periodicals or other materials. Many research libraries are attached to a parent organization and may serve only members of that organization. Examples of research libraries include the British Library, the Bodleian Library at Oxford University and the New York Public Library Main Branch on 42nd Street in Manhattan, State Public Scientific Technological Library of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Science.[70][71]

Digital libraries[edit]

Digital libraries are libraries that house digital resources. They are defined as an organization and not a service that provide access to digital works, have a preservation responsibility to provide future access to materials, and provides these items easily and affordably.[72] The definition of a digital library implies that «a digital library uses a variety of software, networking technologies and standards to facilitate access to digital content and data to a designated user community.»[73] Access to digital libraries can be influenced by several factors, either individually or together. The most common factors that influence access are: The library’s content, the characteristics and information needs of the target users, the library’s digital interface, the goals and objectives of the library’s organizational structure, and the standards and regulations that govern library use.[74] Access will depend on the users ability to discover and retrieve documents that interest them and that they require, which in turn is a preservation question. Digital objects cannot be preserved passively, they must be curated by digital librarians to ensure the trust and integrity of the digital objects.[75]

One of the biggest considerations for digital librarians is the need to provide long-term access to their resources; to do this, there are two issues requiring watchfulness: Media failure and format obsolescence. With media failure, a particular digital item is unusable because of some sort of error or problem. A scratched CD-ROM, for example, will not display its contents correctly, but another, unscratched disk will not have that problem. Format obsolescence is when a digital format has been superseded by newer technology, and so items in the old format are unreadable and unusable. Dealing with media failure is a reactive process, because something is done only when a problem presents itself. In contrast, format obsolescence is preparatory, because changes are anticipated and solutions are sought before there is a problem.[76]

Future trends in digital preservation include: Transparent enterprise models for digital preservation, launch of self-preserving objects, increased flexibility in digital preservation architectures, clearly defined metrics for comparing preservation tools, and terminology and standards interoperability in real time.[76]

Special libraries[edit]

Bookshelves at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. The top floor contains 180,000 volumes. Since 1977, all new acquisitions are frozen at −33 °F (−36 °C) to prevent the spread of insects and diseases.

Many private businesses and public organizations, including hospitals, churches, museums, research laboratories, law firms, and many government departments and agencies, maintain their own libraries for the use of their employees in doing specialized research related to their work. Depending on the particular institution, special libraries may or may not be accessible to the general public or elements thereof. In more specialized institutions such as law firms and research laboratories, librarians employed in special libraries are commonly specialists in the institution’s field rather than generally trained librarians, and often are not required to have advanced degrees in a specifically library-related field due to the specialized content and clientele of the library.

Special libraries can also include women’s libraries or LGBTQ libraries, which serve the needs of women and the LGBTQ community. Libraries and the LGBTQ community have an extensive history, and there are currently many libraries, archives, and special collections devoted to preserving and helping the LGBTQ community. Women’s libraries, such as the Vancouver Women’s Library or the Women’s Library @LSE are examples of women’s libraries that offer services to women and girls and focus on women’s history.

Some special libraries, such as governmental law libraries, hospital libraries, and military base libraries commonly are open to public visitors to the institution in question. Depending on the particular library and the clientele it serves, special libraries may offer services similar to research, reference, public, academic, or children’s libraries, often with restrictions such as only lending books to patients at a hospital or restricting the public from parts of a military collection. Given the highly individual nature of special libraries, visitors to a special library are often advised to check what services and restrictions apply at that particular library.

Special libraries are distinguished from special collections, which are branches or parts of a library intended for rare books, manuscripts, and other special materials, though some special libraries have special collections of their own, typically related to the library’s specialized subject area.

For more information on specific types of special libraries, see law libraries, medical libraries, music libraries, or transportation libraries.

Digital libraries[edit]

In the 21st century, there has been increasing use of the Internet to gather and retrieve data. The shift to digital libraries has greatly impacted the way people use physical libraries. Between 2002 and 2004, the average American academic library saw the overall number of transactions decline approximately 2.2%.[77] Libraries are trying to keep up with the digital world and the new generation of students that are used to having information just one click away. For example, the University of California Library System saw a 54% decline in circulation between 1991 and 2001 of 8,377,000 books to 3,832,000.[78][79]

These facts might be a consequence of the increased availability of e-resources. In 1999–2000, 105 ARL university libraries spent almost $100 million on electronic resources, which is an increase of nearly $23 million from the previous year.[80] A 2003 report by the Open E-book Forum found that close to a million e-books had been sold in 2002, generating nearly $8 million in revenue.[81] Another example of the shift to digital libraries can be seen in Cushing Academy’s decision to dispense with its library of printed books—more than 20,000 volumes in all—and switch over entirely to digital media resources.[82]

A 2001 discussion paper exploring changing use of libraries reported decreased library usage by undergraduate students, who had become more used to retrieving information from the Internet than a traditional library. Finding information by simply searching the Internet is seen as easier and faster than reading an entire book. In a survey conducted by NetLibrary, 93% of undergraduate students said that finding information online made more sense to them than going to the library. Three-quarters said they did not have enough time to go to the library. While the retrieving information from the Internet may be efficient and time-saving than visiting a traditional library, research showed that undergraduates are most likely searching only .03% of the entire web.[83]

In the mid-2000s, Swedish company Distec invented a library book vending machine known as the GoLibrary, that offers library books to people where there is no branch, limited hours, or high traffic locations such as El Cerrito del Norte BART station in California.[84]

Associations[edit]

The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) is the leading international association of library organizations. It is the global voice of the library and information profession, and its annual conference provides a venue for librarians to learn from one another.[85]

Library associations in Asia include the Indian Library Association (ILA),[86] Indian Association of Special Libraries and Information Centers (IASLIC),[87] Bengal Library Association (BLA), Kolkata,[88] Pakistan Library Association,[89] the Pakistan Librarians Welfare Organization,[90] the Bangladesh Association of Librarians, Information Scientists and Documentalists, the Library Association of Bangladesh, and the Sri Lanka Library Association (founded 1960).

National associations of the English-speaking world include the American Library Association, the Australian Library and Information Association, the Canadian Library Association, the Library and Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa, and the Research Libraries UK (a consortium of 30 university and other research libraries in the United Kingdom). Library bodies such as CILIP (formerly the Library Association, founded 1877) may advocate the role that libraries and librarians can play in a modern Internet environment, and in the teaching of information literacy skills.[38][91] The Nigerian Library Association is the recognized group for librarians working in Nigeria. It was established in 1962 in Ibadan.

Public library advocacy is support given to a public library for its financial and philosophical goals or needs. Most often this takes the form of monetary or material donations or campaigning to the institutions which oversee the library, sometimes by advocacy groups such as Friends of Libraries and community members. Originally, library advocacy was centered on the library itself, but current trends show libraries positioning themselves to demonstrate they provide «economic value to the community» in means that are not directly related to the checking out of books and other media.[92]

Protection[edit]

Libraries are considered part of the cultural heritage and are one of the primary objectives in many state and domestic conflicts and are at risk of destruction and looting. Financing is often carried out by robbing valuable library items. National and international coordination regarding military and civil structures for the protection of libraries is operated by Blue Shield International and UNESCO. From an international perspective, despite the partial dissolution of state structures and very unclear security situations as a result of the wars and unrest, robust undertakings to protect libraries are being carried out. The topic is also the creation of «no-strike lists», in which the coordinates of important cultural monuments such as libraries have been preserved.[93][94][95][96]

See also[edit]

- Document management system

- Libraries in fiction

- Library anxiety

- Library portal

- Trends in library usage

- List of libraries

References[edit]

- ^ Pfeifer, Wolfgang (1989). Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Deutschen. A-G. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. p. 166. ISBN 3-05-000641-2.

- ^ a b «The history of libraries». Britannica. May 2020. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ Virani, Shafique N. (1 April 2007). The Ismailis in the Middle Ages. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195311730.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-531173-0. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ Singleton, Brent D. (2004). «African Bibliophiles: Books and Libraries in Medieval Timbuktu». Libraries & Culture. 39 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1353/lac.2004.0019. JSTOR 25549150. S2CID 161645561. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ Howard, Jennifer (Fall 2019). «The Complicated Role of the Public LIbrary». Humanities: the Magazine of the National Endowment of the Humanities. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ «Library & Information Service». Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ «Types of Library and Information Service». Management Decision. 24 (2): 8–24. 1 February 1986. doi:10.1108/eb001400. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ «A quick guide to services provided by Library & Information Services» (PDF). James Cook University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ «Reference and Information Service». Rutgers University Libraries. 27 April 2000. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Marshall, Joanne Gard; Sollenberger, Julia; et al. (2013). «The value of library and information services in patient care: results of a multisite study». Journal of the Medical Library Association. 101 (1): 38–46. doi:10.3163/1536-5050.101.1.007. PMC 3543128. PMID 23418404.

- ^ Government of Tasmania (29 January 2021). «COVID Safe Workplace Guidelines: Library and other information services industry» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ «Information and research services principles». National and State Libraries Australia. 29 March 2019. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ «Library classification». britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ Morris, V. & Bullard, J. (2009). Circulation Services. In Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences (3rd ed.).

- ^ Stueart, Robert; Moran, Barbara B.; Morner, Claudia J. (2013). Library and information center management (Eighth ed.). Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited. ISBN 978-1-59884-988-2. OCLC 780481202.

- ^ Bhattacharjee, Pijush Kanti (2010). «Modified Dewey Decimal Classification Theory for Library Materials Management». International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology. 1 (3): 292–94. Archived from the original on 17 January 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ «ISO – Technical committees – TC 46 – Information and documentation». ISO.org. Archived from the original on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- ^ «ISO – ISO Standards – TC 46 – Information and documentation». ISO.org. Archived from the original on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- ^ Weiss, S.C. (2003). «The origin of library instruction in the United States, 1820–1900». Research Strategies. 19 (3/4): 233–43. doi:10.1016/j.resstr.2004.11.001.

- ^ Mattson, K. (2000). «The librarian as secular minister to democracy: The life and ideas of John Cotton Dana». Libraries & Culture. 35 (4): 514–34.

- ^ Robinson, T.E. (2006). «Information literacy: Adapting to the media age». Alki. 22 (1): 10–12.

- ^ Sloan, B; White, M.S.B. (1992). «Online public access catalogs». Academic and Library Computing. 9 (2): 9–13. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000003734.

- ^ Pantzar, Katja (September 2010). «The humble Number One: Finland». This is Finland. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ Galbi, Douglas (29 July 2007). «Book Circulation Per U.S. Public Library Iser Since 1856». GALB. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ a b Grossman, Wendy M. (21 January 2009). «Why you can’t find a library book in your search engine». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Mostafa, J (2005). «Seeking Better Web Searches». Scientific American. 292 (2): 51–57. Bibcode:2005SciAm.292b..66M. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0205-66. PMID 15715393.

- ^ Corradini, Elena (November 2006). «Teenagers analyse their public library». New Library World. 107 (11): 481–498. doi:10.1108/03074800610713307. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ «Youth Matters» (PDF). The National Archives. July 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Nippold, M.A.; Duthie, J.K. & Larsen, J. (2005). «Literacy as a Leisure Activity: Free-time preferences of Older Children and Young Adolescents». Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 36 (2): 93–102. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2005/009). PMID 15981705.

- ^ Snowball, Clare (February 2008). «Enticing Teenagers into the Library». Library Review. Emerald Group Publishing. 57 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1108/00242530810845035. hdl:20.500.11937/6057.

- ^ Museums, Libraries and Archives, Department of Culture, Media and Sport & Laser Foundation (June 2006). A Research Study of 14–35-year olds for the Future Development of Public Libraries (PDF) (Report). MLA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Darnton, Robert (12 February 2009). «Google & the Future of Books». New York Review of Books. Vol. 56, no. 2. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Garrod, Penny (30 April 2004). «Public Libraries: the changing face of the public library». Ariadne (39). Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Abram, Stephen; Luther, Judy (1 May 2004). «Born with the Chip: the next generation will profoundly impact both library service and the culture within the profession». Library Journal. Archived from the original on 14 September 2013.

- ^ a b Bell, S. (15 May 2005). «Backtalk: don’t surrender library values». Library Journal. Archived from the original on 12 June 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ Novotny, Eric (September 2002). «Reference service statistics and assessment» (PDF). Pennsylvania State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Vrana, R., and Barbaric, A. (2007). «Improving visibility of public libraries in the local community: a study of five public libraries in Zagreb, Croatia». New Library World; 108 (9/10), pp. 435–44.

- ^ a b CILIP (2010). «An introduction to information literacy». CILIP. London. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ Kenney, B. (15 December 2004). «Googlizers vs. Resistors: library leaders debate our relationship with search engines». Library Journal. Archived from the original on 8 June 2005. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ^ DMUELLER (9 February 2015). «Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education». Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL). Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ Hood, David; Henderson, Kay (2005). «Branding in the United Kingdom Public Library Service». New Library World. 106 (1): 16–28. doi:10.1108/03074800510575320. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ «SCREW YOU, FEDS! Dozen or more US libraries line up to run Tor exit nodes». Theregister.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ «Libraries, Tor, Freedom and Resistance». Library Freedom Project at Kilton Library. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015.

- ^ Macrina, Alison (2015). «Accidental Technologist: The Tor Browser and Intellectual Freedom in the Digital Age». Reference & User Services Quarterly. 54 (4): 17. doi:10.5860/rusq.54n4.17. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015.

- ^ «The Amazing Story of Kentucky’s Horseback Librarians (10 Photos)». Archive Project. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ Lamba, Manika (2019). «Marketing of academic health libraries 2.0: a case study». Library Management. 40 (3/4): 155–177. doi:10.1108/LM-03-2018-0013. S2CID 70170037. Archived from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ «St. George Library Workshops». utoronto.ca. 9 August 2018. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Dowler, Lawrence (1997). Gateways to knowledge: the role of academic libraries in teaching, learning, and research. ISBN 0-262-04159-6

- ^ «The Role of Academic Libraries in Universal Access to Print and Electronic Resources in the Developing Countries, Chinwe V. Anunobi, Ifeyinwa B. Okoye». Unllib.unl.edu. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ «TSpace». utoronto.ca. Archived from the original on 17 December 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ «Library Publishing, or How to Make Use of Your Opportunities». LePublikateur. 21 May 2018. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ Lars Aarsgaard, John Dunne, Kathy East, Leikny Haga Indergaard, Susanne Kruger, Ulga Maeots, Rita Schmitt, and Ivanka Stricevic. (2003). «The background text to the Guidelines for Children’s library services» (PDF). IFLA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Modell, David A. (1920). «Children’s Libraries» . In Rines, George Edwin (ed.). Encyclopedia Americana.

- ^ L.O., Aina (2004). Library and Information Science Text for Africa. Ibadan, Nigeria: Third World Information Services Ltd. p. 31. ISBN 9783283618.

- ^ Udomisor, I., Udomisor, E., & Smith, E. (2013). Management of Communication Crisis in a Library and Its Influence on Productivity. In Information and Knowledge Management (Vol. 3, No. 8, pp. 13–21)

- ^ «Paws to read». Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ Line, Maurice B.; Line, J. (1979). «Concluding notes». National libraries, Aslib, pp. 317–18

- ^ Lor, Peter Johan; Sonnekus, Elizabeth A.S. (December 1995). «Guidelines for Legislation for National Library Services». IFLA. Archived from the original on 13 August 2006. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ «About CENL». The Conference of European National Librarians (CENL). Archived from the original on 2 April 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ Celano, D., & Neumann, S.B. (2001). The role of public libraries in children’s literacy development: An evaluation report. Pennsylvania, PA: Pennsylvania Library Association.

- ^ Cohen, L.B. (2007). «A Manifesto for our time». American Libraries. 38: 47–49.

- ^ Jaeger, Paul T.; Bertot, John Carol; Gorham, Ursula (January 2013). «Wake Up the Nation: Public Libraries, Policy Making, and Political Discourse». The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy. 83 (1): 61–72. doi:10.1086/668582. JSTOR 10.1086/668582. S2CID 145670348.

- ^ Ehrenhaft, George; Howard Armstrong, William; Lampe, M. Willard (August 2004). Barron’s pocket guide to study tips. Barron’s Educational Series. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-7641-2693-2. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Champneys, Amian L. (2007). Public Libraries. Jeremy Mills Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-905217-84-7. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ «Audrey Wood: An Inventory of Her Collection at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center». Harry Ransom Center: The University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Young, Heartsill (1983). ALA Glossary of Library and Information Science. Chicago: American Library Association. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-8389-0371-1. OCLC 8907224.

- ^ «Association of Research Libraries (ARL) :: Member Libraries». arl.org. 2012. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ «RLUK: Research Libraries UK». RLUK. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ «Designated Collections». Arts Council England. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ «SPSTL SB RAS». www.spsl.nsc.ru. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ «Our Story». Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Chowdhury, G.G.; Foo, C. (2012). Digital Libraries and Information Access: research perspectives. Chicago: Neal-Schuman. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-1-55570-914-3. OCLC 869282690.

- ^ Chowdhury & Foo (2012), pp. 3–4.

- ^ Chowdhury & Foo (2012), p. 49.

- ^ Borgman, Christine L. (2007). Scholarship in the digital age: information, infrastructure, and the Internet. Cambridge: MIT Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-262-02619-2. OCLC 181028448.

- ^ a b Chowdhury & Foo (2012), p. 211.

- ^ Applegate, Rachel (2008). «Whose Decline? Which Academic Libraries are «Deserted» in Terms of Reference Transactions?». Reference & User Services Quarterly. 48 (2): 176–89. doi:10.5860/rusq.48n2.176. JSTOR 20865037.

- ^ «University of California Library Statistics» (PDF). July 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ «University of California Library Statistics» (PDF). July 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Blixrud, Julia C (2002). «Measures for Electronic Use: The ARL E-Metrics Project» (PDF). p. 74. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

The 105 ARL libraries reporting cost figures spent almost $100 million on electronic resources out of their materials expenditures budget and the figures would be far higher if the expenses for the infrastructure and personnel could be factored into the totals

- ^ Striphas, Ted (2009). The Late Age of Print: Everyday Book Culture From Consumerism to Control. Columbia University Press.

- ^ «Books: «An Outdated Technology?»«. The Late Age of Print. 4 September 2009. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Troll, Denise A. (9 January 2001). «How and Why are Libraries Changing?». Digital Library Federation. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ «Library-a-Go-Go comes to El Cerrito del Norte BART Station | bart.gov». www.bart.gov. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ «International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA)». ifla.org. 2012. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ «Welcome to Indian Library Association». Ilaindia.net. Archived from the original on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ «Welcome to Indian Association of Special Libraries and Information Centers». Iaslic1955.org.in. 3 September 1955. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ «Bengal Library Association». Blacal.org. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ «Pakistan Library Association». Pla.org.pk. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ «Pakistan Librarians Welfare Organization». Librarianswelfare.org. Archived from the original on 10 June 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ Rowlands, Ian; Nicholas, David; Williams, Peter; Huntington, Paul; Fieldhouse, Maggie; Gunter, Barrie; Withey, Richard; Jamali, Hamid R.; Dobrowolski, Tom; Tenopir, Carol (2008). «The Google generation: the information behaviour of the researcher of the future». ASLIB Proceedings. 60 (4): 290–310. doi:10.1108/00012530810887953.

- ^ Miller, Ellen G. (2009). «Hard Times = A New Brand of Advocacy». Georgia Library Quarterly. 46 (1). Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Isabelle-Constance von Opalinski: Schüsse auf die Zivilisation. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung., (German), 20 August 2014.

- ^ Peter Stone: Monuments Men: protecting cultural heritage in war zones. In: Apollo – The International Art Magazine. 2 Februar 2015.

- ^ Corine Wegener, Marjan Otter: Cultural Property at War: Protecting Heritage during Armed Conflict. In: The Getty Conservation Institute, Newsletter. 23.1, Spring 2008.

- ^ Eden Stiffman: Cultural Preservation in Disasters, War Zones. Presents Big Challenges. In: The Chronicle of Philanthropy. 11 May 2015.

Further reading[edit]

- Barnard, T.D.F. (ed.) (1967). Library Buildings: design and fulfilment; papers read at the Week-end Conference of the London and Home Counties Branch of the Library Association, held at Hastings, 21–23 April 1967. London: Library Association (London and Home Counties Branch)

- Belanger, Terry. Lunacy & the Arrangement of Books, New Castle, Del.: Oak Knoll Books, 1983; 3rd ptg 2003, ISBN 978-1-58456-099-9

- Bieri, Susanne & Fuchs, Walther (2001). Bibliotheken bauen: Tradition und Vision = Building for Books: traditions and visions. Basel: Birkhäuser ISBN 3-7643-6429-7

- Buschman, John.(2022). “Of Architects and Libraries: A Simple Discourse Analysis.” The Library Quarterly (Chicago) 92.3: 296–310.

- Copeland, Andrea J. (2015) Libraries Archived 1 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine, International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition). ISBN 978-0-08097-086-8

- Ellsworth, Ralph E. (1973). Academic Library Buildings: a guide to architectural issues and solutions. 530 pp. Boulder: Associated University Press

- Fraley, Ruth A. & Anderson, Carol Lee (1985). Library Space Planning: how to assess, allocate, and reorganize collections, resources, and physical facilities. New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers ISBN 0-918212-44-8

- Herrera-Viedma, E.; Lopez-Gijon, J. (2013). «Libraries’ Social Role in the Information Age». Science. 339 (6126): 1382. Bibcode:2013Sci…339.1382H. doi:10.1126/science.339.6126.1382-a. PMID 23520092.

- Irwin, Raymond (1947). The National Library Service [of the United Kingdom]. London: Grafton & Co. x, 96 p.

- Lewanski, Richard C. (1967). Library Directories [and] Library Science Dictionaries, in Bibliography and Reference Series, no. 4. 1967 ed. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Clio Press. N.B.: Publisher also named as the «American Bibliographical Center».

- Robert K. Logan with Marshall McLuhan. The Future of the Library: From Electric Media to Digital Media. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Mason, Ellsworth (1980). Mason on Library Buildings. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press ISBN 0-8108-1291-6

- Monypenny, Phillip, and Guy Garrison (1966). The Library Functions of the States [i.e. the US]: Commentary on the Survey of Library Functions of the States, [under the auspices of the] Survey and Standard Committee [of the] American Association of State Libraries. Chicago: American Library Association. xiii, 178 p.

- Murray, Suart A.P. (2009). The Library an Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8389-0991-1.

- Orr, J.M. (1975). Designing Library Buildings for Activity; 2nd ed. London: Andre Deutsch ISBN 0-233-96622-6

- Pettegree, Andrew; der Weduwen, Arthur (2021). The Library: A Fragile History. London: Profile Books. ISBN 9781788163422.

- Thompson, Godfrey (1973). Planning and Design of Library Buildings. London: Architectural Press ISBN 0-85139-526-0

External links[edit]

- Libraries at Curlie

- LIBweb—Directory of library servers in 146 countries via WWW

- Centre for the History of the Book, hss.ed.ac.uk

- Libraries: Frequently Asked Questions, ibiblio.org

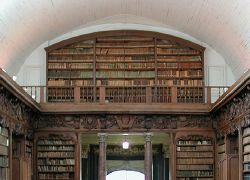

Reading room of the library at the University of Graz, in Austria.

A community library in Ethiopia

In a traditional sense, a library is a large collection of books, and can refer to the place in which the collection is housed. Today, the term can refer to any collection, including digital sources, resources, and services. The collections can be of print, audio, and visual materials in numerous formats, including maps, prints, documents, microform (microfilm/microfiche), CDs, cassettes, videotapes, DVDs, video games, e-books, audiobooks and many other electronic resources.

The places where this material is stored can range from public libraries, subscription libraries, private libraries, and can also be in digital form, stored on computers or accessible over the internet. The term has acquired a secondary meaning: «a collection of useful material for common use.» This sense is used in fields such as computer science, mathematics, statistics, electronics and biology.

A library is organized for use and maintained by a public body, an institution, a corporation, or a private individual. Public and institutional collections and services may be intended for use by people who choose not to — or cannot afford to — purchase an extensive collection themselves, who need material no individual can reasonably be expected to have, or who require professional assistance with their research. In addition to providing materials, libraries also provide the services of librarians who are experts at finding and organizing information and at interpreting information needs. Libraries often provide a place of silence for studying, and they also often offer common areas to accommodate for group study and collaboration. Libraries often provide public facilities to access to their electronic resources and the Internet. Modern libraries are increasingly being redefined as places to get unrestricted access to information in many formats and from many sources. They are extending services beyond the physical walls of a building, by providing material accessible by electronic means, and by providing the assistance of librarians in navigating and analyzing tremendous amounts of information with a variety of digital tools.

Contents

- 1 Early history

- 1.1 Libraries in the Hellenic world and Rome

- 1.2 Ancient Chinese libraries

- 1.3 Libraries and Islam

- 1.4 Medieval Christian libraries

- 1.5 Southeast Asian libraries

- 1.6 Early modern libraries

- 2 Types

- 2.1 Public libraries

- 2.2 Living libraries

- 2.3 Academic libraries

- 3 Organization

- 3.1 Management

- 3.2 Standardization

- 4 Library use

- 4.1 Shift to digital libraries

- 5 Lists of libraries

- 6 See also

- 7 References

- 8 External links

- 8.1 Directories of libraries

- 8.2 Other resources

Early history

The first libraries mainly consisted of published records, housed in a particular type of library, called archives. Archaeological findings from the ancient city-states of Sumer have revealed temple rooms full of clay tablets in cuneiform script. These archives were made up almost completely of the records of commercial transactions or inventories, with only a few documents devoted to theological matters, historical records or legends. Things were much the same in the government and temple records on papyrus of Ancient Egypt.

The earliest discovered private archives were kept at Ugarit; besides correspondence and inventories, texts of myths may have been standardized practice-texts for teaching new scribes. There is also evidence of libraries at Nippur about 1900 BC and those at Nineveh about 700 BC showing a library classification system.[1] Another early organization system was in effect at Alexandria.[2]

Over 30,000 clay tablets from the Library of Ashurbanipal have been discovered at Nineveh,[3] providing modern scholars with an amazing wealth of Mesopotamian literary, religious and administrative work. Among the findings were the Enuma Elish, also known as the Epic of Creation,[4] which depicts a traditional Babylonian view of creation, the Epic of Gilgamesh,[5] a large selection of «omen texts» including Enuma Anu Enlil which «contained omens dealing with the moon, its visibility, eclipses, and conjunction with planets and fixed stars, the sun, its corona, spots, and eclipses, the weather, namely lightning, thunder, and clouds, and the planets and their visibility, appearance, and stations»,[6] and astronomic/astrological texts, as well as standard lists used by scribes and scholars such as word lists, bilingual vocabularies, lists of signs and synonyms, and lists of medical diagnoses.

Libraries in the Hellenic world and Rome

Private or personal libraries made up of non-fiction and fiction books (as opposed to the state or institutional records kept in archives) appeared in classical Greece in the 5th century BC. The celebrated book collectors of Hellenistic Antiquity were listed in the late 2nd century in Deipnosophistae:[7]

Polycrates of Samos and Pisistratus who was tyrant of Athens, and Euclides who was himself also an Athenian[8] and Nicorrates of Samos and even the kings of Pergamos, and Euripides the poet and Aristotle the philosopher, and Nelius his librarian; from whom they say our countryman[9] Ptolemæus, surnamed Philadelphus, bought them all, and transported them, with all those which he had collected at Athens and at Rhodes to his own beautiful Alexandria.[10]

All these libraries were Greek; the cultivated Hellenized diners in Deipnosophistae pass over the libraries of Rome in silence. By the time of Augustus there were public libraries near the forums of Rome: there were libraries in the Porticus Octaviae near the Theatre of Marcellus, in the temple of Apollo Palatinus, and in the Bibliotheca Ulpiana in the Forum of Trajan. The state archives were kept in a structure on the slope between the Roman Forum and the Capitoline Hill.

Private libraries appeared during the late republic: Seneca inveighed against libraries fitted out for show by illiterate owners who scarcely read their titles in the course of a lifetime, but displayed the scrolls in bookcases (armaria) of citrus wood inlaid with ivory that ran right to the ceiling: «by now, like bathrooms and hot water, a library is got up as standard equipment for a fine house (domus).[11] Libraries were amenities suited to a villa, such as Cicero’s at Tusculum, Maecenas’s several villas, or Pliny the Younger’s, all described in surviving letters. At the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum, apparently the villa of Caesar’s father-in-law, the Greek library has been partly preserved in volcanic ash; archaeologists speculate that a Latin library, kept separate from the Greek one, may await discovery at the site.

In the West, the first public libraries were established under the Roman Empire as each succeeding emperor strove to open one or many which outshone that of his predecessor. Unlike the Greek libraries, readers had direct access to the scrolls, which were kept on shelves built into the walls of a large room. Reading or copying was normally done in the room itself. The surviving records give only a few instances of lending features. As a rule, Roman public libraries were bilingual: they had a Latin room and a Greek room. Most of the large Roman baths were also cultural centers, built from the start with a library, a two room arrangement with one room for Greek and one for Latin texts.

Libraries were filled with parchment scrolls as at Library of Pergamum and on papyrus scrolls as at Alexandria: the export of prepared writing materials was a staple of commerce. There were a few institutional or royal libraries which were open to an educated public (such as the Serapeum collection of the Library of Alexandria, once the largest library in the ancient world),[2] but on the whole collections were private. In those rare cases where it was possible for a scholar to consult library books there seems to have been no direct access to the stacks. In all recorded cases the books were kept in a relatively small room where the staff went to get them for the readers, who had to consult them in an adjoining hall or covered walkway.

In the 6th century, at the very close of the Classical period, the great libraries of the Mediterranean world remained those of Constantinople and Alexandria. Cassiodorus, minister to Theodoric, established a monastery at Vivarium in the heel of Italy with a library where he attempted to bring Greek learning to Latin readers and preserve texts both sacred and secular for future generations. As its unofficial librarian, Cassiodorus not only collected as many manuscripts as he could, he also wrote treatises aimed at instructing his monks in the proper uses of reading and methods for copying texts accurately. In the end, however, the library at Vivarium was dispersed and lost within a century.

Through Origen and especially the scholarly presbyter Pamphilus of Caesarea, an avid collector of books of Scripture, the theological school of Caesarea won a reputation for having the most extensive ecclesiastical library of the time, containing more than 30,000 manuscripts: Gregory Nazianzus, Basil the Great, Jerome and others come studied there.

With education firmly in Christian hands, however, many of the works of classical antiquity were no longer considered useful.[citation needed] Old texts were washed off and the valuable parchment and papyrus were reused, forming palimpsests. As scrolls gave way to the new book-form, the codex was universally used for Christian literature. Old manuscript scrolls were cut apart and used to stiffen leather bindings.[citation needed]

Ancient Chinese libraries

A cabinet of books in the Tian Yi Chamber, the oldest extant library in China, dating to 1561.

The imperial library is the earliest known Chinese library, with history dating back to the Qin Dynasty. Han Chinese scholar Liu Hsiang established the first library classification system during the Han Dynasty,[12] and the first book notation system. At this time the library catalog was written on scrolls of fine silk and stored in silk bags.

Libraries and Islam

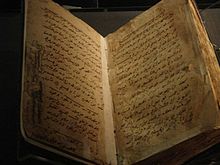

The centrality of the Qurʾān as the prototype of the written word in Islam bears significantly on the role of books within its intellectual tradition and educational system.[13] An early impulse in Islam was to manage reports of events, key figures and their sayings and actions. Thus, «the onus of being the last ‘People of the Book’ engendered an ethos of [librarianship]»[14] early on and the establishment of important book repositories throughout the Muslim world has occurred ever since.

Upon the spread of Islam, libraries in newly Islamic lands knew a brief period of expansion in the Middle East, North Africa, Sicily and Spain. Like the Christian libraries, they mostly contained books which were made of paper, and took a codex or modern form instead of scrolls; they could be found in mosques, private homes, and universities, from Timbuktu to Afghanistan and modern day Pakistan. In Aleppo, for example, the largest and probably the oldest mosque library, the Sufiya, located at the city’s Grand Umayyad Mosque, contained a large book collection of which 10,000 volumes were reportedly bequeathed by the city’s most famous ruler, Prince Sayf al-Dawla.[15] Ibn al-Nadim’s bibliography Fihrist demonstrates the devotion of medieval Muslim scholars to books and reliable sources; it contains a description of thousands of books circulating in the Islamic world circa 1000, including an entire section for books about the doctrines of other religions. Modern Islamic libraries for the most part do not hold these antique books; many were lost, destroyed by Mongols,[16] or removed to European libraries and museums during the colonial period.[17]