In English grammar, a head is the key word that determines the nature of a phrase (in contrast to any modifiers or determiners).

For example, in a noun phrase, the head is a noun or pronoun («a tiny sandwich«). In an adjective phrase, the head is an adjective («completely inadequate«). In an adverb phrase, the head is an adverb («quite clearly«).

A head is sometimes called a headword, though this term shouldn’t be confused with the more common use of headword to mean a word placed at the beginning of an entry in a glossary, dictionary, or other reference work.

Also Known As

head word (HW), governor

Examples and Observations

- «Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.»(Humphrey Bogart as Rick in Casablanca, 1942)

- «As the leader of all illegal activities in Casablanca, I am an influential and respected man.»(Sydney Greenstreet as Senor Ferrari in Casablanca, 1942)

- «The head of the noun phrase a big man is man, and it is the singular form of this item which relates to the co-occurrence of singular verb forms, such as is, walks, etc.; the head of the verb phrase has put is put, and it is this verb which accounts for the use of object and adverbial later in the sentence (e.g. put it there). In phrases such as men and women, either item could be the head.»(David Crystal, A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. Wiley-Blackwell, 2003)

Testing for Heads

«Noun phrases must contain a head. Most frequently this will be a noun or pronoun, but occasionally it can be an adjective or determiner. The heads of noun phrases can be identified by three tests:

1. They cannot be deleted.

2. They can usually be replaced by a pronoun.

3. They can usually be made plural or singular (this may not be possible with proper names).

Only test 1 holds good for all heads: the results for 2 and 3 depend on the type of head.» (Jonathan Hope, Shakespeare’s Grammar. Bloomsbury, 2003)

Determiners as Heads

«Determiners may be used as heads, as in the following examples:

Some arrived this morning.

I have never seen many.

He gave us two

Like third person pronouns these force us to refer back in the context to see what is being referred to. Some arrived this morning makes us ask ‘Some what?’, just as He arrived this morning makes us ask ‘Who did?’ But there is a difference. He stands in place of a whole noun phrase (e.g. the minister) while some is part of a noun phrase doing duty for the whole (e.g. some applications). . . .

«Most determiners occurring as heads are back-referring [that is, anaphoric]. The examples given above amply illustrate this point. However, they are not all so. This is especially the case with this, that, these, and those. For instance, the sentence Have you seen these before? could be spoken while the speaker is pointing to some newly built houses. He is then not referring ‘back’ to something mentioned, but referring ‘out’ to something outside the text [that is, exophora].»

(David J. Young, Introducing English Grammar. Taylor & Francis, 2003)

Narrower and Wider Definitions

«There are two main definitions [of head], one narrower and due largely to Bloomfield, the other wider and now more usual, following work by R.S. Jackendoff in the 1970s.

1. In the narrower definition, a phrase p has a head h if h alone can bear any syntactic function that p can bear. E.g. very cold can be replaced by cold in any construction: very cold water or cold water, I feel very cold or I feel cold. Therefore the adjective is its head and, by that token, the whole is an ‘adjective phrase.’

2. In the wider definition, a phrase p has a head h if the presence of h determines the range of syntactic functions that p can bear. E.g. the constructions into which on the table can enter are determined by the presence of a preposition, on. Therefore the preposition is its head and, by that token, it is a ‘prepositional phrase.'»

Asked by: Fred Wehner

Score: 5/5

(35 votes)

Also called headword, guide word. a word printed at the top of a page in a reference book indicating the first or last entry or article on that page.

What is a guide word example?

The definition of a guide word is a word printed at the top of a page indicating the first or last word entry on that page. An example of guide word is the word «hesitate» printed on a page in a dictionary with the word «hesitate» listed as the first word on the page.

What is guide word and entry word?

Guide Words: These are the words in bold at the top of each page that help to locate an entry word. • The first guide word is the first word on the page. • The second guide word is the last word on the page.

What is headword example?

The headword (or head) in a phrase is that word which is essential to the core meaning of the phrase. It is the word to which the phrase is reducible, for example: This environmentally-friendly car has been using additive-free petrol. CAR USES PETROL.

What is the headword meaning?

1 : a word or term placed at the beginning (as of a chapter or an entry in an encyclopedia)

45 related questions found

What is the headword part of speech?

headword. / (ˈhɛdˌwɜːd) / noun. a key word placed at the beginning of a line, paragraph, etc, as in a dictionary entry.

How you can identify a headword in a dictionary?

a word or phrase that is listed separately with its own definition, examples of use, etc. in a dictionary or similar book: The headwords are in bold dark blue type. «Hard line» is not covered under «line» but is a headword in its own right.

What Is a head words in NLP?

In linguistics, the head or nucleus of a phrase is the word that determines the syntactic category of that phrase. For example, the head of the noun phrase boiling hot water is the noun water. Analogously, the head of a compound is the stem that determines the semantic category of that compound.

What is head word in a sentence?

The head is the most important word in a phrase. All the other words in a phrase depend on the head. Words which are part of the phrase and which come before the head are called the pre-head. Words which are part of the phrase and which come after the head are called the post-head. … In a verb phrase, the head is a verb.

What do you mean by words?

1 : a sound or combination of sounds that has meaning and is spoken by a human being. 2 : a written or printed letter or letters standing for a spoken word. 3 : a brief remark or conversation I’d like a word with you.

What is the headword in the entry?

A headword, lemma, or catchword is the word under which a set of related dictionary or encyclopaedia entries appears. … The headword is used to locate the entry, and dictates its alphabetical position.

What are guide words typically used for?

At the top of each page are two large boldface words separated by a dot. These are called guide words. They show the alphabetical range of the entries on that page, and you can use them to help you find a word quickly.

How do guide words help you in using the dictionary?

Guide words appear on each page of a dictionary. They tell you the first word and last word on the page. The other words on the page come between the guide words in alphabetical order. … If one word is shorter, and there are no more letters to compare, then the shorter word comes first in alphabetical order.

What do you mean by guide?

1a : one that leads or directs another’s way needed a guide for the safari. b : a person who exhibits and explains points of interest The museum guide was very helpful. c : something that provides a person with guiding information used the stars as a guide to find their way back. d : signpost sense 1.

What do you call a person that guides?

leader. A person or thing that leads; directing, commanding, or guiding head, as of a group or activity.

What are the types of Concord in grammar?

- Agreement in terms of number (singular/plural) …

- Concord Relating to the nature of certain nouns. …

- Concord between subject and complement of a sentence. …

- Concord involving the principle of proximity.

- Concord between Determiners and the Nouns they Modify. …

- Concord Involving the Personal Pronouns in the Third Person.

What is Postmodifier example?

postmodifiers. DEFINITIONS1. the part of a noun group, adjective group, or verb group that comes after the most important word (the head) and adds information about it. For example in the noun group ‘the rules of the game’, the prepositional phrase ‘of the game’ is a postmodifier.

What are the examples of determiners?

Determiners in English

- Definite article : the.

- Indefinite articles : a, an.

- Demonstratives: this, that, these, those.

- Pronouns and possessive determiners : my, your, his, her, its, our, their.

- Quantifiers : a few, a little, much, many, a lot of, most, some, any, enough.

- Numbers : one, ten, thirty.

What is phrase in NLP?

The form of n-gram that takes center stage in NLP context analysis is the noun phrase. Noun phrases are part of speech patterns that include a noun. They can also include whatever other parts of speech make grammatical sense, and can include multiple nouns. Some common noun phrase patterns are: Noun.

What is corpus in NLP?

In linguistics and NLP, corpus (literally Latin for body) refers to a collection of texts. Such collections may be formed of a single language of texts, or can span multiple languages — there are numerous reasons for which multilingual corpora (the plural of corpus) may be useful.

What is semantic NLP?

The semantic analysis of natural language content starts by reading all of the words in content to capture the real meaning of any text. It identifies the text elements and assigns them to their logical and grammatical role. … It also understands the relationships between different concepts in the text.

Does a dictionary indicate the idiomatic use of the headword?

A dictionary is a reference book about words and as such it describes the functioning of individual words (sometimes called lexical items). It does so by listing these words in alphabetical order in the form of headwords, the words listed as entries in the dictionary.

What is a headword count?

The headword count refers to the number of headwords a student needs to know in order to read the text with relative ease. The number of headwords is controlled to provide a challenging but accessible read. You can find the number of headwords for each level in a Reader series by checking the series page.

What are post modifiers?

In English grammar, a postmodifier is a modifier that follows the word or phrase it limits or qualifies. Modification by a postmodifier is called postmodification. There are many different types of postmodifiers, but the most common are prepositional phrases and relative clauses.

Table of Contents

- What is the head word in the first entry?

- What is a head Word example?

- What are the different meanings of head?

- Is Head present tense?

- What is the origin of Head?

- Why do we say heads up when we actually duck?

- What is the Old English word for head?

- Who is the head of the family?

- What are older family members called?

- Why father is head of the family?

- What is the oldest female in the family called?

- What is a female patriarch called?

- What is a female leader called?

- What is a female headed household called?

- Can female be considered household head?

- What is a male headed family called?

- What causes female-headed households?

- What is a female household?

- What is the most significant factor contributing to the high number of female headed households?

- What problems do female headed families face?

- What is land entitlement to woman?

- Why are female headed households at greatest risk for poverty?

- What is meant by gender?

- What are the 4 genders?

- What is gender example?

- What is gender roles and examples?

- What is gender language and examples?

- What is a common gender?

In linguistics, the head or nucleus of a phrase is the word that determines the syntactic category of that phrase. For example, the head of the noun phrase boiling hot water is the noun water. Analogously, the head of a compound is the stem that determines the semantic category of that compound.

What is the head word in the first entry?

A head is sometimes called a headword, though this term shouldn’t be confused with the more common use of headword to mean a word placed at the beginning of an entry in a glossary, dictionary, or other reference work.

What is a head Word example?

The headword (or head) in a phrase is that word which is essential to the core meaning of the phrase. It is the word to which the phrase is reducible, for example: This environmentally-friendly car has been using additive-free petrol. CAR USES PETROL.

What are the different meanings of head?

(Entry 1 of 3) 1 : the upper or anterior division of the animal body that contains the brain, the chief sense organs, and the mouth nodded his head in agreement. 2a : the seat of the intellect : mind two heads are better than one. b : a person with respect to mental qualities let wiser heads prevail.

Is Head present tense?

Word forms: plural, 3rd person singular present tense heads , present participle heading , past tense, past participle headed Head is used in a large number of expressions which are explained under other words in the dictionary.

Old English heafod “top of the body,” also “upper end of a slope,” also “chief person, leader, ruler; capital city,” from Proto-Germanic *haubid (source also of Old Saxon hobid, Old Norse hofuð, Old Frisian haved, Middle Dutch hovet, Dutch hoofd, Old High German houbit, German Haupt, Gothic haubiþ “head”), from PIE …

Why do we say heads up when we actually duck?

Because it means pay attention—Look out. It’s an easy way to get someone’s attention without overthinking to say something better. Duck would be perfect in some cases, but heads up has become synonymous with all other warning exclamations.

What is the Old English word for head?

hēafod

Who is the head of the family?

“Head of the family” is a term commonly used by family members to describe an authority position within their lineage. This paper describes family headship as reported by a representative sample of adult men and women.

What are older family members called?

An extended family is a family that extends beyond the nuclear family, consisting of parents like father, mother, and their children, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and cousins, all living in the same household.

Why father is head of the family?

A father is the head of the family. Every father has his own way of dealing with his family. He has responsibility for each member of the family, and this responsibility should be put into action in order to have a better result for the family.

What is the oldest female in the family called?

: a woman who rules or dominates a family, group, or state specifically : a mother who is head and ruler of her family and descendants Our grandmother was the family’s matriarch.

What is a female patriarch called?

matriarch Add to list Share. In any case, patriarch has come to mean the male head of a family or clan, while matriarch is used if the head of a family or clan is female.

What is a female leader called?

other words for female ruler monarch. ruler. consort. empress. regent.

What is a female headed household called?

Families are increasingly headed by women and in such cases are commonly referred to as female -headed, women -headed, or mother -headed families. The terms lone mother and single mother typically refer to the same family structure in different countries.

Can female be considered household head?

In most countries, women are not usually considered as heads of households unless no adult male is living permanently in the household.

What is a male headed family called?

A patriarch is a male leader. Your father might be the patriarch of your family, but your kid brother could be the patriarch of his club house. Although the noun patriarch specifically refers to a male head of the family, it can more generally refer to any older, respected male.

What causes female-headed households?

The number of female-headed households has increased dramatically in the recent half-century, especially in developing countries [6], due to divorce, spouse death, addiction or disability of husband, increased life expectancy among women, migration, or being abandoned by husband [7, 8].

What is a female household?

In the developed countries most female-headed households consist of women who are never married or who are divorced. The feminization of poverty – the process whereby poverty becomes more concentrated among Individuals living in female-headed households – is a key concept for describing FHH social and economic levels.

What is the most significant factor contributing to the high number of female headed households?

Hunger and food-insecurity are caused by poverty. Gender discrimination and, for many, racial/ethnic discrimination make women more likely to be poor. Female-headed households are more than twice as likely as all U.S. households to be poor (30.6 percent vs. 14.8 percent).

What problems do female headed families face?

2 Problems facing women- headed families are: poverty, economic insecurity, social, political, powerlessness, and health problems. While problems facing their children are: poverty, social, and health problems.

What is land entitlement to woman?

Section 6 of the Bill says that every woman farmer should have equal ownership of and inheritance rights over land acquired by her husband; his share of the family property; or his share of land transferred through a government land reform or resettlement scheme.

Why are female headed households at greatest risk for poverty?

Female headed households are most susceptible to poverty because they have fewer income earners to provide financial support within the household.

What is meant by gender?

Gender is used to describe the characteristics of women and men that are socially constructed, while sex refers to those that are biologically determined. People are born female or male, but learn to be girls and boys who grow into women and men.

What are the 4 genders?

The four genders are masculine, feminine, neuter and common.

What is gender example?

Gender is defined as the socially constructed roles and behaviors that a society typically associates with males and females. An example of gender is referring to someone who wears a dress as a female. One’s identity as female or male or as neither entirely female nor entirely male.

What is gender roles and examples?

What are gender roles? Gender roles in society means how we’re expected to act, speak, dress, groom, and conduct ourselves based upon our assigned sex. For example, girls and women are generally expected to dress in typically feminine ways and be polite, accommodating, and nurturing.

What is gender language and examples?

Another example of gendered language is the way the titles “Mr.,” “Miss,” and “Mrs.” are used. “Mr.” can refer to any man, regardless of whether he is single or married, but “Miss” and “Mrs.” define women by whether they are married, which until quite recently meant defining them by their relationships with men.

What is a common gender?

in English, a noun that is the same whether it is referring to either gender, such as cat, people, spouse. in some languages, such as Latin, a noun that may be masculine or feminine, but not neuter.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In linguistics, the head or nucleus of a phrase is the word that determines the syntactic category of that phrase. For example, the head of the noun phrase boiling hot water is the noun (head noun) water. Analogously, the head of a compound is the stem that determines the semantic category of that compound. For example, the head of the compound noun handbag is bag, since a handbag is a bag, not a hand. The other elements of the phrase or compound modify the head, and are therefore the head’s dependents.[1] Headed phrases and compounds are called endocentric, whereas exocentric («headless») phrases and compounds (if they exist) lack a clear head. Heads are crucial to establishing the direction of branching. Head-initial phrases are right-branching, head-final phrases are left-branching, and head-medial phrases combine left- and right-branching.

Basic examples[edit]

Examine the following expressions:

-

-

- big red dog

- birdsong

-

The word dog is the head of big red dog since it determines that the phrase is a noun phrase, not an adjective phrase. Because the adjectives big and red modify this head noun, they are its dependents.[2] Similarly, in the compound noun birdsong, the stem song is the head since it determines the basic meaning of the compound. The stem bird modifies this meaning and is therefore dependent on song. Birdsong is a kind of song, not a kind of bird. Conversely, a songbird is a type of bird since the stem bird is the head in this compound. The heads of phrases can often be identified by way of constituency tests. For instance, substituting a single word in place of the phrase big red dog requires the substitute to be a noun (or pronoun), not an adjective.

Representing heads[edit]

Trees[edit]

Many theories of syntax represent heads by means of tree structures. These trees tend to be organized in terms of one of two relations: either in terms of the constituency relation of phrase structure grammars or the dependency relation of dependency grammars. Both relations are illustrated with the following trees:[3]

The constituency relation is shown on the left and the dependency relation on the right. The a-trees identify heads by way of category labels, whereas the b-trees use the words themselves as the labels.[4] The noun stories (N) is the head over the adjective funny (A). In the constituency trees on the left, the noun projects its category status up to the mother node, so that the entire phrase is identified as a noun phrase (NP). In the dependency trees on the right, the noun projects only a single node, whereby this node dominates the one node that the adjective projects, a situation that also identifies the entirety as an NP. The constituency trees are structurally the same as their dependency counterparts, the only difference being that a different convention is used for marking heads and dependents. The conventions illustrated with these trees are just a couple of the various tools that grammarians employ to identify heads and dependents. While other conventions abound, they are usually similar to the ones illustrated here.

More trees[edit]

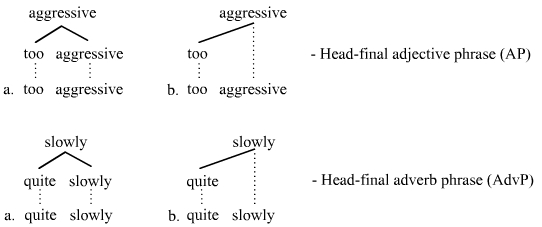

The four trees above show a head-final structure. The following trees illustrate head-final structures further as well as head-initial and head-medial structures. The constituency trees (= a-trees) appear on the left, and dependency trees (= b-trees) on the right. Henceforth the convention is employed where the words appear as the labels on the nodes. The next four trees are additional examples of head-final phrases:

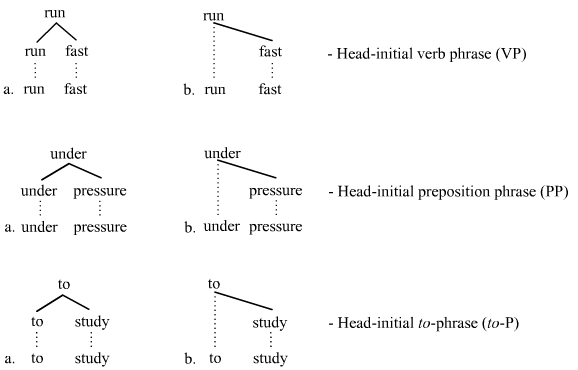

The following six trees illustrate head-initial phrases:

And the following six trees are examples of head-medial phrases:

The head-medial constituency trees here assume a more traditional n-ary branching analysis. Since some prominent phrase structure grammars (e.g. most work in Government and binding theory and the Minimalist Program) take all branching to be binary, these head-medial a-trees may be controversial.

X-bar trees[edit]

Trees that are based on the X-bar schema also acknowledge head-initial, head-final, and head-medial phrases, although the depiction of heads is less direct. The standard X-bar schema for English is as follows:

This structure is both head-initial and head-final, which makes it head-medial in a sense. It is head-initial insofar as the head X0 precedes its complement, but it is head-final insofar as the projection X’ of the head follows its specifier.

Head-initial vs. head-final languages[edit]

Some language typologists classify language syntax according to a head directionality parameter in word order, that is, whether a phrase is head-initial (= right-branching) or head-final (= left-branching), assuming that it has a fixed word order at all. English is more head-initial than head-final, as illustrated with the following dependency tree of the first sentence of Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis:

The tree shows the extent to which English is primarily a head-initial language. Structure is descending as speech and processing move from left to right. Most dependencies have the head preceding its dependent(s), although there are also head-final dependencies in the tree. For instance, the determiner-noun and adjective-noun dependencies are head-final as well as the subject-verb dependencies. Most other dependencies in English are, however, head-initial as the tree shows. The mixed nature of head-initial and head-final structures is common across languages. In fact purely head-initial or purely head-final languages probably do not exist, although there are some languages that approach purity in this respect, for instance Japanese.

The following tree is of the same sentence from Kafka’s story. The glossing conventions are those established by Lehmann. One can easily see the extent to which Japanese is head-final:

A large majority of head-dependent orderings in Japanese are head-final. This fact is obvious in this tree, since structure is strongly ascending as speech and processing move from left to right. Thus the word order of Japanese is in a sense the opposite of English.

Head-marking vs. dependent-marking[edit]

It is also common to classify language morphology according to whether a phrase is head-marking or dependent-marking. A given dependency is head-marking, if something about the dependent influences the form of the head, and a given dependency is dependent-marking, if something about the head influences the form of the dependent.

For instance, in the English possessive case, possessive marking (‘s) appears on the dependent (the possessor), whereas in Hungarian possessive marking appears on the head noun:[5]

| English: | the man‘s house | |

| Hungarian: | az ember ház-a (the man house-POSSESSIVE) |

Prosodic head[edit]

In a prosodic unit, the head is the part that extends from the first stressed syllable up to (but not including) the tonic syllable. A high head is the stressed syllable that begins the head and is high in pitch, usually higher than the beginning pitch of the tone on the tonic syllable. For example:

The ↑bus was late.

A low head is the syllable that begins the head and is low in pitch, usually lower than the beginning pitch of the tone on the tonic syllable.

The ↓bus was late.

See also[edit]

- Branching

- Constituent

- Dependency grammar

- Head-driven phrase structure grammar

- Head directionality parameter

- Head-marking language

- Phrase

- Phrase structure grammar

Notes[edit]

- ^ For a good general discussion of heads, see Miller (2011:41ff.). However, take note Miller miscites Hudson’s (1990) listing of Zwicky’s criteria of headhood as if these were Matthews’.

- ^ Discerning heads from dependents is not always easy. The exact criteria that one employs to identify the head of a phrase vary, and definitions of «head» have been debated in detail. See the exchange between Zwicky (1985, 1993) and Hudson (1987) in this regard.

- ^ Dependency grammar trees similar to the ones produced in this article can be found, for instance, in Ágel et al. (2003/6).

- ^ Using the words themselves as the labels on the nodes in trees is a convention that is consistent with bare phrase structure (BPS). See Chomsky (1995).

- ^ See Nichols (1986).

References[edit]

- Chomsky, N. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- Corbett, G., N. Fraser, and S. McGlashan (eds). 1993. Heads in Grammatical Theory. Cambridge University Press.

- Hudson, R. A. 1987. Zwicky on heads. Journal of Linguistics 23, 109–132.

- Miller, J. 2011. A critical introduction to syntax. London: Continuum.

- Nichols, J. 1986. Head-marking and dependent-marking grammar. Language 62, 56-119.

- Zwicky, A. 1985. Heads. Journal of Linguistics 21, pp. 1–29.

- Zwicky, A. 1993. Heads, bases and functors. In G. Corbett, et al. (eds) 1993, 292–315.

Abbreviation

A reduced version of a

word, phrase, or sentence. Abbreviations are societal slangs.

Absolute

universals Traits,

patterns, or characteristics that occur in all languages.

Acronym

A word that is created

by taking the initial letters of some or all of the words in a phrase

or name and pronouncing them as a word; the

initial letters of some or all the words in a phrase or title and

pronouncing them as a word. This kind of word-formation is common in

names of organizations, military, and scientific terminology.

Adjective

A lexical category

that designates a property or attribute of an entity; it can often

have comparative and superlative degrees and functions as the head of

an adjective phrase

Adverb

A lexical category

that typically denotes a property of the actions, sensations, and

states designated by verbs.

Affix

A bound morpheme that

attaches to a root morpheme; a morpheme that does not belong to a

lexical category and is always bound; bound morpheme, including

prefixes, suffixes, and infixes.

Affixation

The formation of words

by adding derivational affixes to different types of bases; the

process that attaches an affix to a base.

Agglutinating

language A language

where words are formed by adding several morphemes one after the

other, e.g., (Tatar) bala (child) — bala+lar (children)—bala+lar+ga

(to the children)

Allomorph

A variation of a

morpheme; variants of a morpheme ( e. g., [- s], [- z], and [- .z]

are allomorphs of the English plural morpheme).

Allophone

A variation of a

phoneme; a sound representing a given phoneme in certain contexts;

the sounds that make up a phoneme. Allophones are usually in

complementary distribution and phonetically similar.

Ambiguity

More than one meaning

derivable from an utterance.

Amelioration

The process in which

the meaning of a word becomes more favorable; the shift of a word’s

meaning over time from neutral or negative to positive.

Anomaly

Deviation from

expected meaning.

Antonyms

Words or phrases that

have opposite meanings.

Aphesis/

aphaeresis Loss

of one or more letters at the beginning of a word:

story

(history), cello

(violoncello), and phone

(telephone).

Apocopy

Loss of one or more

letters at the end of a word:

ad (advertisement).

Applied

linguistics A

discipline that focuses on practical issues involving the learning

and teaching of foreign/ second languages.

Assimilation

Adjusting in the way a

sound is made so that it becomes similar to some other sound or

sounds near it. A

partial or total conformation to the phonetical, graphical, and

morphological standards of the receiving language and its semantic

system.

Backformation

A word-formation

process that creates a new word by removing a real or supposed affix

from another word in the language; coining

a new word from an older word which is mistakenly taken as its

derivative; the dropping of a peripheral part of a word which is

wrongly analyzed as a suffix.

Base

The form to which an

affix is added; any form to which affixes are appended in

word-formation.

Blend

(blending) A word

formed by joining together chunks of two pre-existing words; a

word-forming process where a new lexeme is produced by combining the

shortened forms of two or more words in such a way that their

constituent parts are identifiable.

Borrowing

(cf.

loan word) Adopting of

linguistic elements, such as morphemes or words of another language;

adopting lexical units or other aspects of one language into another.

Bound

morpheme A morpheme

that must be attached to another element; a morpheme which is always

appended to some other linguistic item because it is incapable of

being used on its own as a word, e.g., -ish. –en, etc.

Bound

root morpheme A

non-affix morpheme that cannot stand alone

Broadening

Change in a word’s

meaning over time to more general or inclusive

Calque

A concept is borrowed but is rendered using the words of the language

doing the borrowing.

Case

ending A marker on a

noun to indicate its grammatical function in a sentence.

Clipping

A process of

word-formation which shortens a polysyllabic word by deleting one or

more syllables, thus retaining only a part of the stem, e.g., lab

(laboratory); word-formation where a long word is shortened to one or

two syllables.

Clitic

A morpheme that is

like a word in terms of its meaning and function, but is unable to

stand alone as an independent form for phonological reasons.

Cliticization

The process where

morphemes act like

words in terms of their meaning or function, but they are unable to

stand alone by themselves: I’m, he’s, etc.

Closed

class (Cf.

Open class) Category

of words that do not accept new members (determiners, auxiliary

verbs, and conjunctions, among others)

Cognates

Words of different

languages which are somehow related in meaning and pronunciation

because they come from a common historical source. Words (with the

same basic meaning) descended from a common ancestor; two, deux

(French), and zwei (German) are cognates (Denham & Lobeck)

Coining

(neologism) Creating a

word.

Collocations

are frequently

occurring sequences of words; the occurrence of two or more words

within a short space of each other in a corpus.

Comparative

method A method where

the systematic comparison of two or more philogenically-related and

non-related languages with the aim of finding the similarities and

differences between or among them; technique of linguistic analysis

that compares lists of related words in a selection of languages to

find cognates, or words descended from a common ancestor

Complementary

pair Two antonyms

related in such a way that the negation of one is the meaning of the

other, e. g., alive means not dead. Cf. gradable pair, relational

opposites.

Complex

word A word that

contains two or more morphemes.

Componential

analysis Analysis

in terms of components; the

representation of a word’s intension in terms of smaller semantic

components called features.

Compositional

semantics The subfield

of semantics where the meanings of the whole sentences are determined

from the meanings of the words in them by the syntactic structure of

the sentence.

Compound

A word composed of two

or more words.

Compounding

Combining one or more words into a single word; a word-forming

process which coins new words not by means of affixation but by

combining two or more free morphemes.

Connotative

meaning/connotation The

personal aspect of lexical meaning, often emotional associations

which a lexeme brings to mind (Crystal, 2005); the set of

associations that a word’s use can evoke.

Constituent

A syntactic unit in a

phrase structure tree; a natural grouping of words in a sentence; one

or more words that make up a syntactic unit; group of words that

forms a larger syntactic unit

Content

words Words with

lexical meanings (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs)

Contrastive

analysis (CA) The

prediction that a contrastive analysis of structural differences

between two or more languages will allow individuals to identify

areas of contrast and predict where there will be some difficulty and

errors on the part of a second-language learner.

Contrastive

lexicology A branch of

linguistics that studies the relation between etymologically related

words and word-combinations in different languages. It deals with the

contrastive analysis of the lexicon, lexico-semantic relationships,

thesauri of entire vocabularies, classification of lexical

hierarchies, and taxonomic structure of specialized terminology

Conversion

A word-formation

process with zero derivation; a

common way to convert one part of speech to another using a form that

represents one part of speech in the position of another without

changing the form of the word at all.

Corpus

linguistics is the

creation and analysis of (normally large, computerized) corpora of

language composed of actual texts (speech and writing), and their

application to problems in descriptive and applied linguistics.

Data

mining Complex methods

of retrieving and using information from immense and varied sources

of data through the use of advanced statistical tools.

Dead

metaphor A metaphor

that is so common that it goes unnoticed as a metaphor

Deep

structure Any phrase

structure tree generated by the phrase structure rules of a

transformational grammar.

Denominal

A word ‘derived from

a noun’, e.g. childish (from the noun child) is a

denominal

adjective.

Denotation

The set of entities to

which a word or expression refers (also called its referents or

extension) (Cf.

Connotation).

Derivation

(morphology) An

affixational process that forms a word with a meaning and/ or

category distinct from that of its base; A word-formation process

that is used to create new vocabulary items, or lexemes, e.g.,

build+er=builder.

Derivation

(syntax) The process

whereby a syntactic structure is formed by syntactic operations such

as Merge and Move.

Derivational

affix An affix that

attaches to a morpheme or word to form a new word.

Derivational morpheme A

morpheme that attaches to a morpheme or word to form a new word.

Derived

word The form that

results from the addition of a derivational morpheme

Descriptive

lexicology A branch of

linguistics that studies the lexicon and lexico-semantic

relationships of a certain language at

a given stage of its development.

Descriptive

linguistics A study

that observes and catalogs languages;

a study that documents

and describes what people say, sign and write, and the grammatical,

lexical and phonological systems they use to do so

Determiner

(det) A functional

category that serves as the specifier of a noun ( e. g., a,

the, and these).

Deverbal

A word ‘derived from

a verb’, e.g. supporter

(from the verb support)

is a deverbal noun.

Dialect

A language variety

that is systematically different from another variety of the same

language and spoken by a socially identifiable subgroup of some

larger speech community.

Dialect atlas A book

of dialect maps showing the areas where specific dialectal

characteristics occur in the speech of the region.

Dialectology

The study of regional

differences in language.

Differential

meaning

The meaning of the semantic component that serves to distinguish one

word from all others containing identical morphemes.

Dissimilation

Process causing two

neighboring sounds to become less alike with respect to some feature.

Distinctive

Describes linguistic

elements that contrast.

Distribution

of a word

The

position of a word in relation to other neighbouring words.

Distributional

meaning The meaning of

a word is considered as the sum total of what it contributes to all

the utterances in which it appears.

Emoticon

A typographic symbol

or combination of symbols used to convey emotion:

Entailment The

relationship between two sentences where the truth of one necessarily

implies the truth of the other; inclusion of one aspect of a word’s

or sentence’s meaning in the meaning of another word or sentence

Enclitics

Clitics which are

attached to the end of the host.

Endocentric

compound A compound

word in which one member identifies the general class to which the

meaning of the entire word belongs.

Epenthesis

The insertion of a

sound inside a word, e.g., dresses [dresiz].

Eponym

A word taken from a

proper name, such as John

for “toilet” (I am going to the john); word that comes from the

name of a person associated with it; the

term which stands for an ordinary common noun derived from a proper

noun, the name of a person, or place.

Etymeme

A bound base that has

etymological relevance ( e. g., — ceive in receive).

Etymology

The history of words;

the study of the history of words.

Etymological

doublets Two words of

the same language which were derived from the same basic word by

different routes.

Etymological

triplets Three words

of the same language which were derived from the same basic word by

different routes.

Euphemism

A word or phrase that replaces a taboo word or is used to avoid

reference to certain acts or subjects.

Exocentric

compound A

compound whose meaning does not follow from the meaning of its parts

(e.g., redneck).

Extension

The referential part

of the meaning of an expression; the referent of a noun phrase. Folk

etymology (False etymology) merely

associates together words which resemble each other in sound and show

a real or fancied similarity of meaning, but which are not at all

related in their origin” (Greenough & Kittredge, 1967, p.145).

Free

morpheme Morpheme that

can stand alone as a word; a morpheme capable of occurring on its

own, such as a word.

Functional

category One of the

categories of function words, including determiner, auxiliary,

complementizer, and preposition. Cf. lexical category and phrasal

category.

Functional

affixes Affixes that

serve to convey grammatical meaning.

Function

word A word mainly

serving a grammatical function in a sentence; a word that does not

have clear lexical meaning but has a grammatical function; function

words include conjunctions, prepositions, articles, auxiliaries,

complementizers, and pronouns. Cf. closed class.

Gapping

The syntactic process

of deletion in which subsequent occurrences of a verb are omitted in

similar contexts.

General

lexicology A branch

of general linguistics

that studies vocabulary irrespective of the specific features of any

particular language and the meaning of words and word-combinations in

isolation and in context.

Grammatical

categories Traditionally

called “parts of speech”; also called syntactic categories;

expressions of the same grammatical category can generally substitute

for one another without loss of grammaticality, e. g., noun phrase,

verb phrase.

Grammatical

meaning

The component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual

forms of different words.

Grammatical

valency

The aptness of a word to appear in specific grammatical (or rather

syntactic) structures (Ginsburg et

al.).

Head

(of a compound) The

rightmost word. It generally indicates the category and general

meaning of the compound.

Head

(of a phrase) The

central word of a phrase whose lexical category defines the type of

phrase, e. g., the noun man is the head of the noun phrase the man

who came to dinner; the verb wrote

is the head of the verb phrase wrote

a letter to his mother;

the adjective red is the head of the adjective phrase very bright

red; word whose syntactic category determines the category of the

phrase

Headword

The form of the word

which appears at the beginning of its dictionary entry. It is

normally uninflected and often gives syllabic information.

Heteronyms

Different words spelled the same (i. e., homographs) but pronounced

differently.

Historical

and comparative linguistics The

branch of linguistics that deals with how languages change, what

kinds of changes occur, and why they occur.

Homographs

Words spelled

identically, and pronounced the same or differently; words that have

the same spelling, different meanings, and different pronunciations.

Homonyms

Two or more words that

are pronounced and/ or written the same way; words with the same

sound and spelling but different, unrelated meanings

Homophones

Words that do not

share the same spellings or meanings but sound the same

Hyponyms

Words whose meanings

are specific instances of a more general word; word whose meaning is

included, or entailed, in the meaning of a more general word (tulip/

flower)

Hypothesis

A theoretical

statement that proposes how several constructs relate to one another

Ideogram

A symbol that

represents an idea

Idiolect

An individual’s way

of speaking, reflecting that person’s grammar; the unique form of a

language represented in an individual user’s mind and attested in

their discourse.

Idiom/

idiomatic phrase An

expression whose meaning does not conform to the principle of

compositionality, that is, may be unrelated to the meaning of its

parts; collocation of words or phrases with non-literal meaning; it

has a transferred meaning, e.g., kick

the bucket (die).

Indo-European

The language

reconstructed by linguists which is assumed to be the ancestor of

most European languages; the descriptive name given to the ancestor

language of many modern language families, including Germanic,

Slavic, and Romance. Also called Proto– Indo- European.

Infix

A bound morpheme that

is inserted in the middle of a word or stem; an affix placed inside a

root.

Inflectional

affix An affix that

adds grammatical information to an existing word.

Inflectional

morpheme Bound

grammatical morpheme that is affixed to a word according to rules of

syntax, e. g., third- person singular verbal suffix — s.

Initialism

A word formed from the

initial letters of a group of words.

Internal

change The process

which substitutes one non-morphemic part for another to mark a

grammatical contrast.

Interpreting

The process of

translating from and into spoken or signed language.

Intertextuality

(Tool of Inquiry)

Isogloss

Geographical boundary

of a particular linguistic feature

Jargon

Special words peculiar

to the members of a profession or group;specialized

vocabulary associated with a trade or profession, sport, game, etc.,

e. g., airstream mechanism for phoneticians. Cf. argot.

Jargon

aphasia Form of

aphasia in which phonemes are substituted, resulting in nonsense

words; often produced by people who have Wernicke’s aphasia.

Langue

in structural

linguistics, the set of organizing principles of signs, including

rules of combination

Lexeme

A word in the sense of

an item of vocabulary that can be listed in the dictionary. A lexeme

is a lexical item; the smallest contrastive unit in a semantic system

(Crystal).

Lexical

ambiguity A word or a

phrase that has more than one meaning;

ambiguity as a result

of homonyms

Lexical

category A general

term for the word- level syntactic categories of noun, verb,

adjective, and adverb. These are the categories of content words like

man, run, large, and rapidly, as opposed to functional category words

such as the

and and.

Cf. functional category, phrasal category, open class.

Lexical

decision Task of

subjects in psycholinguistic experiments who on presentation of a

spoken or printed stimulus must decide whether it is a word or not.

Lexical

gap Possible but

non-occurring words; forms that obey the phono-tactic rules of a

language yet have no meaning, e. g., blick

in English. Lexical

gaps occur in a language when it lacks a word for a concept (which

may be expressed lexically in another language).

Lexical

semantics The subfield

of semantics concerned with the meanings of words and the meaning

relationships among words; a study of the conventions of word

meaning.

Lexical

valency

The aptness of a word to appear in various combinations (Ginzburg et

al.)

Lexicographer

One who edits or works

on a dictionary.

Lexicography

The editing or making

of a dictionary.

Lexicology

The study of the

lexicon, or word-stock, its meaning, the relations among lexemes, the

structure of lexemes,

their etymology and lexical units, and relations between lexicology

and other areas of the language: phonology, morphology, phraseology,

lexicography, and syntax.

Lexicon

Our mental dictionary;

stores information about words and the lexical rules we use to build

them.

Lingua

franca A language

common to speakers of diverse languages that can be used for

communication and commerce; a language used as a medium of

communication between speakers of different languages.

Linguistic

competence Unconscious

knowledge of grammar that allows us to produce and understand a

language.

Linguistic

relativity A theory

that language and culture influence or perhaps even determine each

other.

Linguistics

the scientific study

of language.

Linguistic

theory A theory of the

principles that characterize all human languages; the “laws of

human language.”

Linguistic

universal Characteristic

shared by all human languages.

Loan

translations Compound

words or expressions whose parts are translated literally into the

borrowing language, e. g., marriage of convenience from French

mariage de convenance.

Also called calque.

Loan

word A word in one

language whose origins are in another language; a word borrowed into

a language from another language.

Macron

A short straight line

placed above a vowel to indicate that it is pronounced long.

Malapropism

Use of the wrong word which resembles phonologically the intended

word; type of production error by which a speaker uses a semantically

incorrect word in a place of phonetically similar word without being

aware of the mistake.

Marked

In a gradable pair of

antonyms, the word that is not used in questions of degree, e. g.,

low

is the marked number of the pair high/

low because we

ordinarily ask How high

is the mountain? not

How low is the

mountain?; in a

masculine/ feminine

pair, the word that contains a derivational morpheme, usually the

feminine word, e. g., princess is marked, whereas prince is unmarked

(Cf. unmarked)

Markedness

Opposition in meaning that differentiates between the typical meaning

of a word and its “ marked” meaning or opposite (right is

unmarked, and left is marked).

Mass

nouns Nouns that

cannot ordinarily be enumerated, e. g., bread, meat, and milk (Cf.

count nouns).

Mental

lexicon The dictionary

that is in the speaker’s mind; it contains a list of words as well

as rules that help to coin words that are not listed.

Meronymy

A part– whole

relationship between lexemes.

Metaphor

Non-literal meaning of

one word or phrase describes another word or phrase.

Metonymy

Description of

something in terms of some-thing with which it is closely associated.

Mixed

metaphor A metaphor

that comprises parts of different metaphors: hit the nail on the

jackpot com-bines hit the nail on the head and hit the jackpot

(Denham & Lobeck).

Monomorphemic

word A word that

consists of one morpheme.

Morph

Any concrete

realization of a morpheme.

Morpheme

Smallest unit of

linguistic meaning or function; a minimal unit of meaning or function

in a language.

Morphological

motivation

The relationship between morphemes.

Morphological

rules Rules for

combining morphemes to form stems and words.

Morphological

typology Classification

of languages according to common morphological structures.

Morphology

The study of the

structure of words; it also includes the rules of word-formation; the

study of how languages combine morphemes to make words; the

systematic patterning of meaningful word parts, including prefixes

and suffixes; study of the system of rules underlying our knowledge

of the structure of words.

Motivation

The relationship existing between the phonemic or morphemic

composition and structural pattern of the word, on the one hand, and

its meaning on the other (Arnold).

Mutually

intelligible Language

varieties that can be understood by speakers of the two (or more)

varieties.

Narrowing

Change in words’

meanings over time to more specific meanings.

Negation

Causing a statement to

have the opposite meaning by inserting not between Aux and V

Neologism

A newly coined word

which is intended to gain or appears to be gaining common currency in

the language.

Notional

meaning A meaning when

a word expresses ideas, concepts, images, and feelings.

Nyms

Meaning relationships

among words— antonyms, synonyms, homonyms, etc.

Onomatopoeia/

onomatopoeic A word

that mirrors an aspect of its meaning; words whose pronunciations

suggest their meaning; the

naming of a thing or action by a vocal imitation of the sound

associated with it, e.g., e.g.

cuckoo is onomatopoeic.

Open

form class The class

of lexical content words; a category of words that commonly adds new

words, e. g., nouns, adjectives, adverbs, and verbs; a category of

words that accepts new members (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and

adverbs).

Overgeneralization

Application of a

grammatical rule more broadly than it is generally applied.

Paradigm A set of

forms derived from a single root morpheme; the system of grammatical

forms characteristic of a word, e. g., take, takes, taken, took,

taking; or woman, women, woman’s, and women’s.

Parole

In structural

linguistics, the physical utterance itself; the use of a sign or a

set of signs. Part of

speech Classification

of a word according to its form and function.

Philosophical

semantics The subfield

of semantics that is concerned with logical properties of language.

Phonetical

motivation

When there is a certain similarity between the sound-form of a word

and its meaning when speech sounds may suggest spatial and visual

dimensions, shape, and size.

Phrase A

syntactic unit (NP, VP, etc.) headed by a syntactic category ( N, V,

etc.); a syntactic constituent headed by a lexical category, i.e. a

noun, adjective, verb, adverb or preposition, e.g., with hospitality

(noun phrase).

Phraseology

A subfield of

lexicology that studies phraseological units.

Phraseological

unit A stable

combination of words with complete or partial transferred meaning

Phrase

structure A system of

rules that organizes words into larger units or phrases.

Phrenology

A pseudoscience, the

practice of which is determining personality traits and intellectual

ability by examination of the bumps on the skull. Its contribution to

neurolinguistics is that its methods were highly suggestive of the

modular theory of brain structure.

Pictogram

A picture or symbol

that represents an object or idea; a form of writing in which the

symbols resemble the objects represented; a non-arbitrary form of

writing.

Pidgin

A simple but

rule-governed language developed for communication among speakers of

mutually unintelligible languages, often based on one of those

languages.

Pluralia

tantum refers to a

noun that is morphologically plural but semantically singular

(trousers).

Polymorphemic

Words consisting of

more than one morpheme.

Polysemy

A semantic process

whereby a lexeme assumes two or more related meanings. Pragmatics

The study of language

use in context; the study of how context and situation affect

meaning; study of the meanings of sentences in context (utterance

meaning).

Praxis

is educational jargon

for ‘practice’ or ‘enaction,’ from the Greek verb prattein,

‘to do.’

Predicate

Syntactically, the

verb phrase (VP) in the clause [NP VP].

Prefix

An affix that is

attached to the beginning of a morpheme or stem; an affix that

attaches to the beginning of a root; an affix that goes before the

stem.

Preposition

(P) The syntactic

category, also lexical category, that heads a prepositional phrase.

Prepositional

object The grammatical

relation of the noun phrase that occurs immediately below a

prepositional phrase (PP) in deep structure.

Prepositional

phrase (PP) The

syntactic category, also phrasal category, consisting of a

preposition and a noun phrase.

Principle

of compositionality A

principle of semantic interpretation that states that the meaning of

a word, phrase, or sentence depends both on the meaning of its

components (morphemes, words, phrases) and how they are combined

structurally.

Proclitics

Clitics which are

attached to the beginning of the host.

Productive

Refers to

morphological rules that can be used freely and apply to all forms to

create new words, e. g., the addition to an adjective of —

ish meaning “ having

somewhat of the quality,” such as newish

and

tallish.

Qualitative

research Research that

is done in a natural setting, involving intensive holistic data

collection through observation at a very close personal level without

the influence of prior theory and contains mostly verbal analysis

(Perry, 2011, p. 257).

Quantitative

research A study that

uses numerical data with emphasis on statistics to answer the

research questions.

Reduplication

A morphological

process of forming new

words by repeating the entire free morpheme (total reduplication) or

a part of it (partial reduplication):

wishy- washy, teensy- weensy, etc.

Reference

deals with the relationship between linguistic elements, words,

sentences, etc., and the non-linguistic world of experience (Palmer).

Referent

The object,

relationship, and class of objects outside world to which a word

refers. Regional

dialect A dialect

spoken in a specific geographic area that may arise from, and is

reinforced by, that area’s integrity.

Regionalism

A feature that

distinguishes one regional dialect from others

Register

Manner of speaking or

writing style adopted for a particular audience (e. g., formal versus

informal); a stylistic variant of a language appropriate to a

particular social setting; also called style; language style

appropriate to a particular social setting; a way of using the

language in certain contexts and situations, often varying according

to formality of expression, choice of vocabulary and degree of

explicitness.

Register

tones Level tones;

high, mid, or low tones.

Relational

opposites Pair of

antonyms in which one describes a relationship between two objects

and the other describes the same relationship when the two objects

are reversed.

Retronym

An expression that

would once have been redundant, but which societal or technological

changes have made non-redundant.

Root

The morpheme at the

core of a word to which affixes are added.

Root

morpheme A morpheme to

which an affix can be attached.

Second

language acquisition (SLA, L2 acquisition) The

acquisition of another language or languages after first language

acquisition is under way or completed.

Semantic

features A notational

device for expressing the presence or absence of semantic properties

by pluses and minuses; the smallest component of meaning in a word;

classifications of meaning that can be expressed in terms of binary

features [+/–], such as [+/– human], [+/– animate], [+/–

count].

Semantic

fields Basic

classifications of meaning under which words are stored in our mental

lexicons.

Semantic

motivation

The co-existence of direct and figurative meanings of the same word

within the same synchronous system (Arnold).

Semantic

properties The

components of meaning of a word, e. g., “old” is a semantic

property of man, woman,

wine, story, and

movie.

Semantic

shift Change in the

meaning of words over time.

Semantics

The study of the

linguistic meaning of morphemes, words, phrases, and sentences; the

study of the meanings of words and sentences; the study of meaning

communicated through language; system of rules underlying our

knowledge of word and sentence meaning.

Semasiology

The science of meanings or sense development (of words); the

explanation of the development and changes of the meanings of words

(Encyclopedia).

Semiotics

The study of sign

systems; the use of sign systems.

Sense

deals with the complex

system of relationships that hold between the linguistic elements

themselves and is concerned with extralinguistic relations (Palmer).

Sentence

semantics The subfield

of semantics that studies the meanings of the sentences and meaning

relations between the sentences.

Shift

in connotation Change

in words’ general meanings over time.

Shift

in denotation Complete

change in words’ meanings over time.

Sign

The abstract link that

connects sound and idea.

Signification

The process of

creating and interpreting symbols.

Signified

In structural

linguistics, the concept, idea, or meaning of the signifier.

Signifier

In structural

linguistics, a spoken or signed word or a word on a page.

Simile

Comparison, usually of

two unlike things, in order to create a non-literal image.

Slang

An informal word or

expression that has not gained complete acceptability and is used by

a particular group; a

word and a phrase used

in casual speech, often invented and spread by close- knit social or

age groups, and fast changing.

Social

dialect A dialect

spoken by a particular social class (e. g., Cockney English) that is

perpetuated by the integrity of the social class (Cf. regional

dialect).

Sociolinguistics

The study of the

relationship between language and society; study of how language

varies over space (by region, ethnicity, social class, etc.).

Special

lexicology A

branch of general linguistics that studies words and

word-combinations, and describes the vocabulary and vocabulary units

of a particular language.

Spoonerism

Slip of the tongue, an

exchange error; a type of speech error where by accident (or

sometimes by design, one suspects) initial sounds in syllables of

neighboring words swap places, e.g., lighting

a fire — fighting a liar

Stem

The base to which one

or more affixes are attached to create a more complex form that may

be another stem or a word. Cf.

root, affix.

Structural

ambiguity The

phenomenon in which the same sequence of words has two or more

meanings based on different phrase structure analyses; ambiguity that

results from two or more possible grammatical structures assignable

to an utterance, e. g., He saw a boy with a telescope.

Structure

dependent (1) A

principle of Universal

Grammar that states

that the application of transformational

rules is determined by

phrase structure properties, as opposed to structureless sequences of

words or specific sentences; (2) the way children construct rules

using their knowledge of syntactic structure irrespective of the

specific words in the structure or their meaning (Fromkin &

Hummel, p. 669).

Style

Situation dialect, e.

g., formal speech, casual speech; also called register.

Subject

Syntactically, the

noun phrase (NP) in the clause [NP VP]

Submersion

method Educating

nonnative speakers of a language in that language, without systematic

accommodations to their native language.

Suffix

An affix that is

attached to the end of a morpheme or stem; an affix that attaches to

the end of a root.

Suppletion

A morphological process that replaces one morpheme with an entirely

different morpheme to indicate a grammatical contrast.

Suppletive

forms A term used to

refer to inflected morphemes in which the regular rules do not apply.

Syncope

The

loss of one or more

letters in the interior of a word:

specs

(spectacles).

Synesthesia

Metaphorical language

in which one kind of sensation is described in terms of another; for

example, a smell may be described as sweet or a color as loud

Synonyms

Words with the same or

nearly the same meaning; words that have similar meanings

Syntax

The rules of sentence

formation; the component of the mental grammar that rep-resents

speakers’ knowledge of the structure of phrases and sentences; the

study of how words combine into larger units.

Taxeme

The basic feature of

arrangement of morphemes.

Theoretical

linguistics builds

theories about the nature and limits of grammatical, lexical and

phonological systems.

Tree

diagram A graphical

representation of the linear and hierarchical structure of a phrase

or sentence; a phrase structure tree.

Typology

The comparative study of significant structural similarities and

differences among languages

Underextension

Use of words to apply

to things more narrowly than their actual meaning.

Valency

A lexico-syntactic property which involves the relationship between,

on the one hand, the different subclasses of a word-class (such as a

verb) and, on the other, the different structural environments

required by the subclasses, these environments varying both in the

number and in the type of elements (Allerton).

Verb

phrase A verb together

with its complements and modifiers; the predicate of the sentence is

a verb phrase (Koln & Funk, 2012).

Word

A

minimal free form; the

smallest linguistic unit capable of standing meaningfully on its own.

Word-formation

The process of coining new words from existing ones.

References

Aitchison,

J. (1987). Words

in the mind. Oxford,

UK: Basil Blackwell Inc.

Algeo, J., & Pyles, T.

(2010). The origins and

development of the English language

(6th ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth.

Allerton, D. J. (2005). Valency

grammar. In K. Brown (Ed.), The

Encyclopedia of

language and linguistics

(pp. 4878–4886). Kidlington, UK: Elsevier Science.

Arnold, I. (1986). The

English word. Moscow:

Visshaya Shkola.

Austin, J. L. (1975). How

to do things with words.

(2nd ed.). London, UK: Clarendon Press.

Ayers, D. (1986). English

words. Tucson, AZ: The

University of Arizona Press.

Barber, C. (1964). The

story of speech and language.

New York, NY: Thomas Y. Crowell Company.

Baugh, A., & Cable, T.

(1993). A history of

the English language

(4th

ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice.

Bauer,

L. (1983). English

word-formation.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bauer, L.

(2008). ‘Les composés exocentriques de l’anglais’ in Dany

Amiot (ed.), La

composition dans uneperspective typologique.

Arras: Artois Presses Université, 35-47.

Bauer, L., &

Nation, P. (1993). Word families. International

Journal of Lexicography, 6(4),

253-279.

Blake, W. (1793). Two

sunflowers move in the yellow room. Retrieved from

http://www.portablepoetry.com/poems/william_blake/ah_sunflower.html

Bloomfield,

L. (1935). Language.

London: Allen & Unwin.

Boguslavsky, I., Cardeñosa, J.,

& Gallardo, C. (2009). A novel approach to creating disambiguated

multilingual dictionaries. Retrieved from Academic Search Complete.

Burchfield, R. (1986).

Supplement to the

Oxford English

Dictionary. New York,

NY: Oxford University

Press.

Cabré, M.T. (1992). Terminology:

Theory, methods, and applications.

Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing.

Cowie, A.P. (2001). Phraseology:

Theory, analysis, and application.

New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Crystal, D. (2003). The

Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language

(2nd

ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Denham, K., & Lobeck, A.

(2011). Linguistics

for everyone: An Introduction.

Boston, MA: Wadsworth,

Cengage Learning

De Saussure, F. (1959). Course

in general linguistics.

(W. Baskin, Trans.). New York, NY: Philosophical Library.

Dictionary. (2002). Funk

& Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia.

Retrieved from Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia database.

Doroszewski, W. (1973). Elements

of lexicology and semiotics.

Mouton: Polish Scientific Publishers.

Elgin, S. (1979). What

is linguistics?

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Encyclopedia.

(2011). Columbia

electronic encyclopedia

(6th ed.). Retrieved from Academic

Search Complete.

Firbas, J. (1992). Functional

sentence perspective in written and spoken communication.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Fries, C. C. (1957). The

Structure of English: An introduction to the construction of English

sentences. London,

England: Longmans, Green.

Fromkin, V., Rodman, R., Hyams,

N., & Hummel, K. (2010). An

introduction to language

(4th Canadian ed.). Toronto, ON: Nelson/Thompson.

Gardiner, A.H.

(1922).

The

definition of the word and the sentence. The

British Journal of Psychology,

12(4),

352-361. DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1922.tb00067.x

Ginzburg, R. S., Khidekel,

S.S., Knyazeva,

G.Y, Sankin,

A.A. (1979). A

course in modern English lexicology

(2nd

Ed.). Moscow:

Visshaya Shkola.

Glaser, R. (2001). The stylistic

potential of phraseological units in the light of genre analysis. In

A.P. Cowie (Ed.), Phraseology:

Theory, analysis, and application

(pp. 125-143). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Greenough, J., Kittredge, G.

(1967). Folk etymology. In D. E. Hayden, E.P. Alworth, & G.Tate

(Eds), Classics in

Linguistics (pp.144-154).

New York, NY: Philosophical Library.

Grondelaers, S., & Geeraerts,

D. (2003). Towards a pragmatic model of cognitive onomasiology. In

Cuyckens, H., Dirven, R., Taylor, J. (eds.). Cognitive

approaches to cognitive semantics.

Berlin, Germany, 67-92.

Halliday, M.A.K., Yallop, C.

(2007). Lexicology: A

short introduction.

Great Britain: Cromwell Press.

Hendrickson, R. (2008). Word

and phrase origins

(4th

ed.). New York, NY: Checkmark Books.

Hobbs, J. (1999). Homophones

and homographs (3rd

ed.). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Hurford, J., Heasley, B., Smith,

M. (2007). Semantics

(2nd

ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Introducing ‘tebowing.’

(2011). Retrieved from

http://sports.yahoo.com/nfl/blog/shutdown_corner/post/Introducing-Tebowing-It-8217-s-like-planking-?urn=nfl-wp10549

Jackson, H. (1991). Words

and their meaning.

London, England: Longman.

Jackson, H., & Ze Amvela.

(2007). Words, meaning,

and vocabulary: An introduction to modern English lexicology (2nd

ed.). London, England: Continuum.

Jesperson, O. (1938). Growth

and structure of the English Language.

Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Kolln, M., Funk, R. (2012).

Understanding English

grammar (9th

ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Longman.

Krapp, J. (1925). The

English language in America (Vol.1).

New York, NY: Frederick Ungar.

Кunin, А.V. (1972). English

phraseology. Мoscow,

RF.

Кunin, А.V. (1996). A

course in English phraseology.

Мoscow, RF.

Lakoff, G., & Turner, M.

(1989). More than cool

reason: A field guide to poetic metaphor.

Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lehman, C. (n.d.). Lexicography.

Retrieved from

http://www.christianlehmann.eu/ling/ling_meth/ling_description/lexicography/index.html

Leroy, M. (1967). Main

trends in modern linguistics.

(G. Price, Trans.). Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: California

University Press.

Linsky, L. (Ed.). (1972).

Semantics and the

philosophy of language.

Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Lipka, L. (2002). English

lexicology: Lexical structure, word semantics and word-formation.

Tübingen,

Germany: Narr.

The living Webster:

Encyclopedic dictionary of the English language.

(1977). Chicago, IL: The English Language Institute of America.

Lyons, J. (1977). Semantics.

Cambridge: University Press.

Meillet

A. (1926). Linguistique

historique et linguistique generate.

Paris:

Librairie Ancienne Honore Champion.

Menken,

H. L. (1921). The

American Language. New

York, NY: Alfred A.Knopf.

Menner,

R. (1936). The conflicts of homophones in English. Language,

12, 229-244.

Morehead, P. (Ed.). (1978). The

New American Roget’s

College Thesaurus. New

York, NY: Signet

Murphy, M.L. (2006). Antonomy and

incompatibility. In K. Allan, Concise

encyclopedia of semantics

(pp.25-28). Oxford, UK: Elsevier.

Murphy,

M. L. (2003). Semantic

relations and the lexicon.

Cambridge, UK: University Press.

Murphy, P. (2011). The technical

aspects of technicality. International

Journal of Evidence and Proof, 15,

144-160.

doi:10.1350/ijep.2011.15.2.374

Newmeyer, F. (1980). Linguistic

theory in America. New

York, NY: Academic Press.

Nist, A. (1966). A

structural history of English.

New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

O’Grady, W., Archibald, J.,

Aronoff, M., & Rees-Miller, J. (2001). Contemporary