|

|

This article uses bare URLs, which are uninformative and vulnerable to link rot. Please consider converting them to full citations to ensure the article remains verifiable and maintains a consistent citation style. Several templates and tools are available to assist in formatting, such as Reflinks (documentation), reFill (documentation) and Citation bot (documentation). (August 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

First edition |

|

| Author | Barry Unsworth |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Hutchinson |

|

Publication date |

1967 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 224 pp |

The Greeks Have a Word For It is the second novel by Booker Prize-winning author Barry Unsworth published by Hutchinson in 1967. It has since been republished by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in 1993 and W. W. Norton & Company in 2002.[1] It has been praised for its ‘utterly convincing characterizations’.[2]

Background[edit]

It is set in Athens in the aftermath of the Greek Civil War and draws on the author’s own experiences teaching English as a foreign language, satirizing many members of the British Council in Athens.[3]

Plot introduction[edit]

Two men arrive in Athens on the same boat. Kennedy an Englishman intends to make a living teaching English and devises a scam to make money fast. Mitsos is returning to Greece after many years away but finds it impossible to escape the memories of the brutal deaths of his parents at the hands of fellow Greeks during the war and an opportunity arises to take revenge. The two men meet briefly as they disembark the boat but their stories then diverge only to come together at the end of the book with fatal results.[4][5]

References[edit]

- ^ «The Greeks Have a Word for It by Barry Unsworth».

- ^ http://books.wwnorton.com/books/detail.aspx?id=6939

- ^ «New English Readers — Morality Play».

- ^ «Powell’s Books | the World’s Largest Independent Bookstore».

- ^ «The Greeks Have a Word for it : Barry Unsworth : 9781857990027».

Novels by Barry Unsworth |

|---|

|

Usually, Professor Georgios Babiniotis would take pride in the fact that the Greek word “pandemic” – previously hardly ever uttered – had become the word on everyone’s lips.

After all, the term that conjures the scourge of our times offers cast-iron proof of the legacy of Europe’s oldest language. Wholly Greek in derivation – pan means all, demos means people – its usage shot up by more than 57,000% last year according to Oxford English Dictionary lexicographers.

But these days, Greece’s foremost linguist is less mindful of how the language has enriched global vocabulary, and more concerned about the corrosive effects of coronavirus closer to home. The sheer scale of the pandemic and the terminology spawned by its pervasiveness have produced fertile ground for verbal incursions on his mother tongue that Babiniotis thought he would never see.

“We have been deluged by new terms and definitions in a very short space of time,” he told the Observer. “Far too many of them are entering spoken and written Greek. On the television you hear phrases such as ‘rapid tests are being conducted via drive-through’, and almost all the words are English. It’s as if suddenly I’m hearing Creole.”

With nine dictionaries to his name, the octogenarian is the first to say that language evolves. The advent of the internet also posed challenges, he concedes, but he has never opposed adding new words that translated and conveyed technological advances. “I included them in the Lexicon,” he says of his magisterial 2,500-page dictionary of modern Greek language. “But where possible, I also insisted that if they could be replaced by Greek words they should. I came up with the word diadiktyo for the internet and am glad to say it has stuck.”

Almost no tongue has been spoken as continuously as Greek, used without respite in roughly the same geographical region for 40 centuries. Its influence, as the language of the New Testament and as a vehicle of thought for golden age playwrights, scientists and philosophers, helped it withstand the test of time.

But Babiniotis, a former education minister, worries that the resilience that has marked Greek’s long history is at risk of being eroded by an onslaught of English terms that now dominate everyday life. In the space of a year, he says, Greeks have had to get their heads, and tongues, around words such as “lockdown”, “delivery”, “click away”, “click-and-collect” and “curfew”.

As shopping restrictions in Greece were reinforced on Friday against a backdrop of infection rates rising again, click inside – a system allowing consumers to enter shops if they have made an appointment beforehand – was also introduced by officials desperate to keep the pandemic-hit retail sector going.

“There has to be some moderation,” Babiniotis sighs, lamenting that even government announcements are now replete with the terminology. “We have a very rich language. As the saying goes, ‘the Greeks must have a word for it.’ Lockdown, for example, could be perfectly easily translated.”

There was a certain mentality, he said, that had enabled English to flourish in places it shouldn’t be. “Ever more shops are carrying English-language signage as a way, I’m afraid, of having greater sales and outreach. Instead of artopoieio, Greek for bakery, we’re seeing shops calling themselves ‘bread factories’, while barbers are now ‘hairdressers’. Next we’ll have ‘hair stylists!’ It won’t stop.”

This is not the first time that a war of words has erupted over Greek. Arguments over the language, between proponents of change and traditionalists advocating a return to its Attic purity as a means of reviving the golden age, go back to the first century BC. Controversy continued through 400 years of Ottoman rule, becoming especially explosive in the run up to the war of independence in 1821.

The struggle over whether purist Greek, or katharevousa, officially inducted as the language of the state after the revolution, should prevail over demotiki, the commonly spoken vernacular, raged until 1976 when demotic officially replaced it.

“For Greeks, language has always been a sensitive issue,” says Babiniotis. “I know what I say troubles some, but it is the duty of a linguist to speak out.”

Babiniotis’s protestations have been fodder for cartoonists and the butt of debate. But he is not alone.

The emergence of “Greenglish” – Greek written with English letters – as an unofficial e-language since the arrival of the internet has also sparked alarm. Facebook groups have emerged, deploring the phenomenon. “A lot of youngsters use it to message one another because they think it’s easier,” says Susanna Tsouvala at the Polyglot Bookstore, which specialises in foreign language textbooks in central Athens. “Spelling’s easier and they don’t have to use the accents required in Greek, but ultimately it’s going to be our language’s loss.”

For many, book publishers have become the last line of defence. At Patakis, one of the country’s most established publishers, inclusion of foreign words in any work is carefully monitored. “Books are guardians of the language,” insists Elena Pataki, whose family-run firm publishes books for all ages. “We recently published a business book about family-owned enterprises and made a conscious choice to limit references to foreign terms.”

Babiniotis has a point, she says.

“Why should Greeks in their 90s have to understand English to go and shop? The pandemic has produced a global language for a global problem. My hope is when this is over, we’ll hit delete and forget all these words.”

You’ve probably heard the saying “the Greeks had a word for it” (sometimes given as “the Greeks have a word for it”).

But you may not be aware of how this enigmatic idiomatic expression got its start.

It was launched into our language with a splash on September 25, 1930, when a bawdy play titled The Greeks Had a Word for It opened on Broadway.

The play was written by the Missouri-born American playwright, poet and screenwriter Zoe Akins (1886-1958). And, she is generally given credit for coining the phrase.

Several of Akins’ plays had been produced prior to that night.

One of them — Declassée, starring Ethel Barrymore — was a big hit on Broadway in 1919.

In 1935, Akins won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama for her play The Old Maid (1935).

But her most remembered play (and play on words) is The Greeks Had a Word for It, a comedy about three young “gold diggers” on the hunt for wealthy men.

What was the “It” the Greeks had a word for?

Well, obviously, “It” is a reference to something you weren’t supposed to mention directly at the time.

I’m guessing you can figure “It” out. If not, here’s a hint…

In 1932, Twentieth Century Fox made a film version of the play, starring Joan Blondell, Madge Evans and Ina Claire.

The original title of the film was The Greeks Had a Word for Them.

Why the change?

Because the producers worried that the word “It” would be deemed too blatantly salacious by the censors who enforced the The Motion Picture Production Code of 1930 (a.k.a. the Hays Code), which was designed to prevent “obscenity” and violence in films.

So, initially, they changed “It” to “Them.”

But then even the revised title raised concerns, since some of the possible words for “Them” that people thought it meant could also be considered too vulgar.

Thus, the name of the film was ultimately changed to Three Broadway Girls.

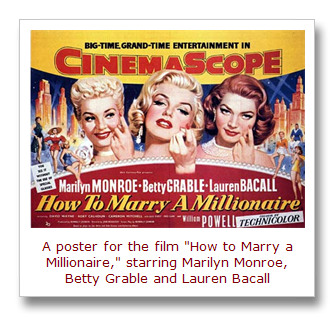

In 1953, Zoe Akins’ play The Greeks Had a Word for It was used as the basis for a much more famous film starring Marilyn Monroe, Betty Grable and Lauren Bacall.

It was titled How to Marry a Millionaire and it helped launch Marilyn into the top echelon of superstardom.

Although that film also avoided using Akins’ original play title, it revived interest in her and her plays.

As a result, she was hired as a scriptwriter for some of the most prestigious early dramatic series developed for television in the 1950s, including the Kraft Television Theatre and Screen Directors Playhouse.

Her phrase “the Greeks had a word for it” survived and outlived the stuffy censors of earlier decades.

It became a common saying that is still used for humorous effect.

What “It” refers to nowadays varies depending on the context and does not always mean something “obscene” – though typically “It” still does.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Post them on my quotations Facebook group.

Related reading and viewing…

Первое издание Первое издание |

|

| Автор | Барри Ансуорт |

|---|---|

| Страна | Соединенное Королевство |

| Язык | Английский |

| P ublisher | Hutchinson |

| Дата публикации | 1967 |

| Тип носителя | Печатный (Твердый переплет Бумажный переплет ) |

| Страницы | 224 |

У греков есть слово — второй роман лауреата Букеровской премии автора Барри Ансворта, опубликованный Хатчинсоном в 1967 году. С тех пор он был переиздан Weidenfeld Nicolson в 1993 году и W. W. Norton Company в 2002 году. Он получил высокую оценку за «совершенно убедительные характеристики».

Предпосылки

Действие происходит в Афинах после о гражданской войне в Греции и опирается на собственный опыт автора преподавания английского языка как иностранного, высмеивая многих членов Британского совета в Афинах.

Введение в сюжет

Двое мужчин прибывают в Афины на одной лодке. Кеннеди, англичанин, намеревается зарабатывать на жизнь преподаванием английского языка и изобретает мошенничество, чтобы быстро заработать деньги. Мицос возвращается в Грецию после многих лет отсутствия, но считает невозможным избавиться от воспоминаний о зверской смерти своих родителей от рук других греков во время войны, и появляется возможность отомстить. Двое мужчин ненадолго встречаются, выходя из лодки, но затем их истории расходятся, а в конце книги они сходятся воедино и приводят к фатальным результатам.

Ссылки

Our vocabulary for ideas, thoughts and abstractions comes mainly from Latin. Though it gave us directly only about 20% of the words we use day-to-day, Latin was the only written language in use before the renaissance, and it was the language of both faith and scholarship.

The story does not end there, however. Latin, in turn, was an evolution from a mixture of other dialects and languages, including a large helping from ancient Greece.

Why does this matter? It matters because a large budget of words in English are made up of Greek words, especially those terms used to describe ideas and concepts. People in most jobs may never need to use (or understand) the word “anthropomorphism,” for example. But if you go to college, rest assured that it will come up. If you know a little Greek, the word is not mysterious at all. “Anthropos” means “man” — as in mankind — and then “–morph” is a combining term meaning “having the shape of.” The “–ism” particle is, as you probably know, a flag for a belief system, practice or method of thinking. So this word means the practice of attributing human-like qualities to non-human entities, whether gods, animals or inanimate objects.

It’s fair to assume that you will not be learning Greek, especially ancient or New Testament Greek, any time soon. So the second best solution is to learn the meanings of these Greek-origin combination forms found so often in educated English writing. These are word particles that the Romans found useful to incorporate into Latin, and now, a couple of millennia later, they appear in English. They are called “morphemes,” and the study of them is one of the three areas embraced within the general heading of “grammar.” Here I’ve included them under “Vocabulary.”

What follows is a table of 95 morphemes that come to us from Greek, together with their meanings and examples of English words that contain them. The Greek word is also given, in the Greek alphabet (which you would do well to learn) and in our alphabet (called the Latin alphabet). If you master these morphemes, you will have the key to thousands of English terms. The table is paginated in groups of 20.

Greek Morphemes

| Meaning | Example | In English Usage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| acr- | height, summit, tip | ἄκρος (ákros) «high», «extreme» | acrobatics, acrophobia, acropolis |

| aero- | air, atmosphere | ἀήρ, ἀέρος (āḗr, āéros) «air» | aerobic, aerodynamic, aeronautics, aerosol |

| aesth- | feeling, sensation | αἰσθάνεσθαι ( aisthánesthai ) «to perceive» | aesthetics, anaesthetic |

| aether-, ether- | upper pure, bright air | αἴθειν ( aíthein ), αἰθήρ ( aithḗr ) | ether, ethereal |

| alg- | pain | ἄλγος ( álgos ), ἀλγεινός, ἀλγεῖν ( algeîn ), ἄλγησις ( álgēsis ) | analgesic, neuralgia, nostalgia |

| amph-, amphi- | both, on both sides of, both kinds | ἀμφί (amphí) «on both sides» | amphibious, amphitheatre |

| an-, a-, am-, ar- | not, without | ἀν-/ἀ- «not» | ambrosia, anaerobic, anhydrous, atheism, atypical |

| anem- | wind | ἄνεμος (ánemos) | anemometer, anemone |

| ant-, anti- | against, opposed to, preventive | ἀντί (antí) «against» | antagonize, antibiotic, antipodes |

| anthrop- | human | ἄνθρωπος (ánthrōpos) «man» | anthropology, misanthrope, philanthropy |

| archae-, arche- | ancient | ἀρχαῖος ( arkhaîos ) «ancient» from ἀρχή ( arkhḗ ) «rule» | archaeology, archaic |

| arct- | Relating to the North Pole | ἄρκτος (árktos) «bear» (Ursa Major), ἀρκτικός (arktikós) | Antarctica, Arctic Ocean |

| aster-, astr- | star, star-shaped | ἄστρον ( ástron ) «star» | aster, asterisk, asteroid, astrology, astronomy, astronaut |

| aut-, auto- | self; directed from within | αὐτός (autós) «self», «same» | autarchy, authentic, autism, autocracy, autograph, automatic, autonomy |

| bapt- | dip | βάπτειν (báptein) | baptism, baptize |

| bio-, bi- | life | βίος ( bíos ) «life» | biography, biohazard, biology |

| botan- | plant | βοτάνη, βότανον (botánē, bótanon) | botanist, botany |

| cardi- | heart | καρδιά (kardía) | cardiac, cardiology, electrocardiogram |

| caust-, caut- | burn | καυστός/καυτός (kaustós) | calm, caustic, cauterize, holocaust |

| chore- | relating to dance | χορεία ( khoreia ) «dancing in unison» | choreography, chorus |

| chrom- | color | χρῶμα (chrōma) | chromatic, chrome, chromosome, monochrome |

| chron- | time | χρόνος (chronos) | anachronism, chronic, chronicle, chronology, chronometer, synchronize |

| -cracy, -crat | government, rule, authority | κράτος (krάtos), κρατία (kratía) | aristocracy, autocrat, bureaucracy, democrat, plutocracy, technocrat, theocracy |

| crypt- | hidden | κρύπτειν ( kruptein ) «to hide» | apocryphal, cryptic, cryptography |

| dec- | ten | δέκα ( déka ) «ten» | decade, Decalogue, decathlon |

| dem- | people | δῆμος (dēmos) | demagogue, democracy, demography, epidemic |

| di- | two | δι- ( di- ) | diode, dipole |

| dia- | apart, through | διά (diá) | diagram, dialysis, diameter |

| dyna- | power | δύναμις (dúnamai) | dynamic, dynamite, dynamo, dynasty |

| ec- | out | ἐκ (ek) | eccentric, ecstasy, ecstatic |

| eco- | house | οἶκος (oikos) | ecology, economics, ecumenism |

| ep-, epi- | above, upon, outer | ἐπί (epi) | epicenter, epidemic, epitaph, epiphany |

| ethn- | people, race, tribe, nation | ἔθνος (ethnos) | ethnic, ethnicity |

| eu- | well, good | εὖ (eu) | euphoria, euthanasia, eulogy |

| ger- | old | γέρων, γέροντος (gérōn, gérontos) | geriatric, gerontocracy |

| gloss-, glot- | tongue | γλῶσσα (glóssa), γλωττίς (glōttís) | epiglottis, gloss, glossary, polyglot |

| glyph- | carve | γλύφειν (glúphein) | glyph, glyptograph, petroglyph |

| graph- | draw, write | γράφειν ( gráphein ) | autograph, graph, graphic, graphite, holograph, monograph, orthography, paragraph, photograph, telegraphy |

| gymn- | nude | γυμνός (gumnós) | gymnasium, gymnastics |

| hemi- | half | ἥμισυς (hēmisus) | hemicycle, hemisphere |

| heter- | different, other | ἕτερος (heteros) | heterodoxy, heterogeneous, heterosexual |

| hol- | whole | ὅλος (holos) | holistic, holography |

| hom- | same | ὁμός (homos) | homogeneous, homophone, homonym, homosexual |

| hydr- | water | ὕδωρ (hudōr) | dehydrate, hydrant, hydraulic, hydrogen, hydrolysis, hydrophily, hydrophobia, hydrous |

| hyp- | under | ὑπό (hupo) | hypoallergenic, hypodermic, hypothermia |

| hyper- | above, over | ὑπέρ (huper) | hyperactive, hyperbole |

| hypn- | sleep | ὕπνος (hupnos) | hypnosis, hypnotize |

| idi- | own, peculiarity | ἴδιος (ídios), «private, personal, one’s own» | idiom, idiosyncrasy, idiot |

| is-, iso- | equal, same | ἴσος (ísos) | isometric, isomorphic, isosceles |

| kine-, cine- | movement, motion | κινεῖν ( kineîn ), κίνησις ( kínēsis ), κίνημα ( kínēma ) | cinema, kinesthetic, kinetic, telekinesis |

| klept- | steal | κλέπτειν ( kléptein) | kleptomania, kleptocracy |

| lith- | stone | λίθος (lithos) | megalith, Mesolithic, monolith, Neolithic |

| log-, -logy | word, reason, speech, thought | λόγος ( logos ), λογία ( logia ) | apology, dialogue, etymology, eulogy, logic, monologue, neologism, prologue, terminology, theology |

| macro- | long | μακρός (makrós) | macrobiotic, macroeconomics, macron |

| mania | mental illness, craziness | μανία (manίā) | kleptomania, mania, maniac, pyromania |

| meta- | above, among, beyond | μετά (metá) | metabolism, metamorphosis, metaphor, metaphysics, meteor, method |

| meter-, metr- | measure | μέτρον (métron) | barometer, diameter, isometric, meter, metronome, parameter, perimeter, symmetric, telemetry, thermometer |

| micro- | small | μικρός (mikrós) | microcosm, microeconomics, micrometer, microphone, microscope |

| mim- | repeat | μιμεῖσθαι ( mīmeîsthai ), μίμος ( mimos ) | mime, mimeograph, mimic, pantomime |

| mis- | hate | μισεῖν ( miseîn ) | misanthrope, misogynist, misotheism |

| mne- | memory | μνήμη (mnēmē) | amnesia, amnesty, mnemonic |

| mon- | alone, one | μόνος (mónos) | monarchy, monastery, monolith, monopoly, monotone |

| mor- | foolish, dull | μωρός (mōrós) | moron, oxymoron, sophomore |

| morph- | form, shape | μορφή (morphē) | amorphous, anthropomorphism, endomorph, metamorphosis, morpheme, morphology, polymorphic |

| myth- | story | μῦθος (mûthos) | myth, mythic, mythology |

| narc- | numb | νάρκη (narkē) | narcolepsy, narcosis, narcotic |

| naut- | ship | ναύτης ( nautes ) | astronaut, nautical |

| ne-, neo- | new | νέος (neos) | Neolithic, neologism, neonate, neophyte |

| necr- | dead | νεκρός (nekros) | necrophobia, necrotic |

| nom- | arrangement, law, order | νόμος (nomos) | astronomy, autonomous, gastronomy, metronome, numismatic, polynomial, taxonomy |

| -oid | like | -οειδής (-oeidēs) | asteroid, humanoid, organoid |

| olig- | few | ὀλίγος ( oligos ) | oligarchy, oligopoly |

| pan- | all | πᾶς, παντός (pas, pantos) | Pan-American, panacea, pandemic, pandemonium, panoply |

| path- | feeling, disease | πάθος (pathos) | antipathy, apathy, empathy, pathetic, pathology, sociopath, sympathy |

| peri- | around | περί (perí) | perimeter, period, periphery, periscope |

| pher-, phor- | bear, carry | φέρω ( pherō ), φόρος ( phoros ) | metaphor, pheromone |

| phil-, -phile | love, friendship | φιλέω (phileō) | bibliophile, philanthropy, philharmonic, philosophy |

| phob- | fear | φόβος (phobos) | acrophobia, claustrophobia, homophobia, hydrophobia |

| phos-, phot- | light | φῶς, φωτός ( phōs , phōtos ) | phosphor, phosphorus, photic, photo, photoelectric, photogenic, photograph, photosynthesis |

| physi- | nature | φύσις (phusis) | physics |

| plut- | wealth | πλοῦτος (ploutos) | plutocracy |

| pneu- | air, breath, lung | pnein, πνεῦμα (pneuma) | apnoea, pneumatic, pneumonia |

| pod- | foot | πούς, ποδός ( pous , podos ) | antipode, podiatry, tripod |

| pole-, poli- | city | πόλις (polis) | acropolis, cosmopolitan, metropolis, police, policy, politics |

| polem- | war | πόλεμος (polemos) | polemic, polemology |

| poly- | many | πολύς (polus) | polyandry, polygamy, polygon, polytheistic |

| pro- | before, in front of | πρό (pro) | prologue, prominent |

| prot- | first | πρῶτος (prōtos) | protagonist, protocol, protoplasm, prototype, protozoan |

| pseud- | false | ψευδής (pseudēs) | pseudonym |

| psych- | mind | ψυχή (psuchē) | psyche, psychiatry, psychology, psychosis |

| scop-, scept- | look at, examine, view, observe | σκέπτομαι, σκοπός (skeptomai, skopos) | horoscope, microscope, periscope, skeptic, stethoscope, telescope |

| soma- | body | σῶμα, σώματος (sōma, sōmatos) | psychosomatic, somatotype |

| soph- | wise | σοφός (sophos) | philosophy, sophistry, sophistication, sophomoric |

| syn-, sy-, syl-, sym- | with | σύν (sun) | symbol, symmetry, sympathy, synchronous, synonym |

| tele- | far, end | τῆλε (tēle) | telegram, telemetry, telepathy, telephone, telescope, television |

| xen- | foreign | ξένος (xenos) | xenogamy, xenophobia, xenon |

About the Book

Do you ever search in vain for exactly the right word? Perhaps you want to articulate the vague desire to be far away? Or you can’t quite convey that odd urge to go outside and check to see if anyone is coming? Maybe you’re struggling to say there’s just the right amount of something – not too much, but not too little? While the English may not have a word for it, the good news is that the Greeks, the Norwegians, the Dutch or possibly the Inuit probably do.

Whether it’s mafan (a Mandarin word for when you just can’t be bothered) or the Indonesian jayus (a joke so poorly told and so unfunny that you can’t help but laugh), this delightful smorgasbord of wonderful words from around the world will come to your rescue when the English language fails. Part glossary, part amusing musings, but wholly enlightening and entertaining, The Greeks Had a Word For It means you’ll never again be lost for just the right word.

Dedication

For Sam, Abi and Rebecca,

and Lucy, Sophie and Tom

Foreword

Words are among the most important things in our lives – somewhere just behind air, water and food. For a start, they’re the way we pass on our thoughts from one to another and from generation to generation. Without words, it’s hard to see how mankind could ever have evolved from ape-like creatures grunting at the entrance to a cave and wondering where they were going to find their next meal.

But words do more than that. They help us define our emotions, our experiences and the things we see. Put a name to something and you have started out on the road to understanding it.

To look at the figures, you’d think that we already have more than enough words in English – estimates vary between five hundred thousand and just over two million, depending on how you count them. And most educated people use no more than twenty thousand words or so, which means that we ought to have plenty to spare. Yet we’ve all had those moments when we want to say something and we can’t find exactly the right one. Words are like happy memories – you can never have enough of them in your head.

And, maybe most important of all in these days of global interaction, when we need to understand each other more than ever before, words say something about us. If people need a word for a particular feeling, or action, or experience, it suggests that they find it important in their lives – the Australian Aboriginals, for instance, have a word that conveys a sense of intense listening, of contemplation, of feeling at one with history and with creation. In Spanish, there’s a word for running one’s fingers through a lover’s hair, and in French one for the sense of excitement and possibility that you may feel when you find yourself in an unfamiliar place.

Words bring us together. They’re precious. And if they’re sometimes very funny, too – well, how good is that?

Matters of the Heart

Physingoomai

(Ancient Greek)

Traditionally, sexual excitement as a result of eating garlic; but in a modern sense, the use of inappropriate adornments to enhance sexual attraction

THERE ARE SOME foreign words the English language clearly needs – the case for them is so obvious that it hardly needs to be put. Others require a little more advocacy on their behalf. Take, for example, the Ancient Greek word physingoomai (fiz-in-goo-OH-mie).

It refers to someone who gets over-confident and sexually excited as a result of eating garlic. Fighting cocks were frequently fed garlic and onions before a bout because the Greeks – and later cockfight aficionados – believed that it would make the birds fiercer. The idea is that if men were to follow the example of the fighting cocks and gorge on garlic before going on a date, there would be no holding them back.

Whether or not garlic makes men horny, it certainly makes them smelly and thus less pleasant to be close to. As a result, even in these days when programmes about cooking are all over the television and when people seem more than happy to talk publicly about their sexual preferences, it seems unlikely that it is a word that is going to be used frequently outside the rather restricted world of cockfighting. Even the Ancient Greeks don’t seem to have required it all that often, since the word itself appears only once in the entire canon of Greek literature, referring to some soldiers from the town of Megara in a comedy by Aristophanes.

In the play, however excited the soldiers get, it’s apparent that they are going to have serious difficulties persuading any self-respecting Ancient Greek girls to kiss their garlic-reeking lips. The remedy they have sought to increase their sexual potency at the same time greatly reduces their ability to take advantage of it.

And there lies the clue to why physingoomai would be such a useful term in English. Young men who douse themselves in the sort of cheap aftershave that strips the lining from your nasal passages at first whiff; middle-aged men wearing blue jeans so tightly belted around where their waist used to be that their bellies sag opulently over the top; women of a certain age wearing clothes that would have been daring on their daughters – they are all, if they only knew it, falling into the same trap as the Megaran soldiers.

The adornments they have chosen to boost their confidence and make them more attractive to potential partners are exactly the things that will put those partners off. Cheap aftershave, tight belts and sagging bellies, and clothes that have been clearly stolen from your daughter’s wardrobe can be as effective as a garlic overdose in keeping people at arm’s length. Instead of whatever it was they were hoping for, those who rely on them to enhance their sexual appeal are likely to suffer what we might call a physingoomai experience. And there are few more physingoomai experiences than showing off by using long words to try to impress someone. Just talking about physingoomai could lead to the most humiliating physingoomai experience of all.

Cafuné

(Brazilian Portuguese)

Closeness between two people – for example, to run one’s fingers tenderly through someone’s hair

Think for a moment of the gentleness of affection. It needs a tone and a language of its own – not the urgent, demanding words of love and passion, but gentle, undemanding affection, the sort of love that asks for nothing. It is often so diffident and unassuming that it may sometimes seem to take itself – although never its object – for granted. It may be the warm, safe, family feeling between a mother or father and their child, or the love of grandparents for their grandchildren; perhaps it is the closeness between two people that may some day turn into love, or it may be the relaxed fondness that remains when the fire of a passionate affair has burned low. Either way, it demands its own expression.

Читать дальше

О книге

Добавлена в библиотеку 22.08.2018

пользователем Elleroth

Размер fb2 файла: 323.20 KB

Объём: 100 страниц

4.64

Книгу просматривали 256 раз, оценку поставили 53 читателя

Аннотация

Do you ever search in vain for exactly the right word? Perhaps you want to

articulate the vague desire to be far away. Or you can’t quite convey that odd

urge to go outside and check to see if anyone is coming. Maybe you’re

struggling to express there being just the right amount of something – not too

much, but not too little. While the English may not have a word for it, the

good news is that the Greeks, the Norwegians, the Dutch or possibly the Inuits

probably do.

Whether it’s the German spielzeug (that instinctive feeling of ‘rightness’) or

the Indonesian jayus (a joke so poorly told and so unfunny that you can’t help

but laugh), this delightful smörgåsbord of wonderful words from around the

world will come to the rescue when the English language fails. Part glossary,

part amusing musings, but wholly enlightening and entertaining, The Greeks Had

a Word For It means you’ll never again be lost for just the right word.

Скачать или читать онлайн книгу The Greeks Had a Word for It: Words You Never Knew You Can’t Do Without

На этой странице свободной электронной библиотеки fb2.top любой посетитель может

читать онлайн бесплатно полную версию книги «The Greeks Had a Word for It: Words You Never Knew You Can’t Do Without» или скачать fb2

файл книги на свой смартфон или компьютер и читать её с помощью любой

современной книжной читалки. Книга написана автором Эндрю Тэйлор,

относится к жанру Языкознание, иностранные языки,

добавлена в библиотеку 22.08.2018 и доступна

полностью, абсолютно бесплатно и без регистрации.

С произведением «The Greeks Had a Word for It: Words You Never Knew You Can’t Do Without» , занимающим объем 100 печатных страниц,

вы наверняка проведете не один увлекательный вечер. В нашей онлайн

читалке предусмотрен ночной режим чтения, который отлично подойдет для тёмного

времени суток и чтения перед сном. Помимо этого, конечно же, можно читать

«The Greeks Had a Word for It: Words You Never Knew You Can’t Do Without» полностью в классическом режиме или же скачать всю книгу

целиком на свой смартфон в удобном формате fb2. Желаем увлекательного

чтения!

С этой книгой читают:

- Анатомия призраков

— Эндрю Тэйлор - Загадка Эдгара По

— Эндрю Тэйлор - Пэлем Гренвилл Вудхаус. О пользе оптимизма

— Александр Ливергант - Чисто по-русски

— Марина Королёва - Английский язык с Льюисом Кэрроллом — Through The Looking Glass

— Илья Франк, Льюис Кэрролл - Английский язык с Льюисом Кэрроллом — Приключения Алисы в Стране Чудес

— Илья Франк, Льюис Кэрролл - Спорные истины «школьной» литературы

— Григорий Яковлев - Пишут все! Как создавать контент, который работает

— Энн Хэндли - Рецензия на книгу: А. А. Реформатский. Из истории отечественной фонологии. — М., 1970. 527 стр.

— Лев Зиндер - Морфонологическая модификация основы слова и место ударения

— Вера Воронцова

Аннотация

Do you ever search in vain for exactly the right word? Perhaps you want to

articulate the vague desire to be far away. Or you can’t quite convey that odd

urge to go outside and check to see if anyone is coming. Maybe you’re

struggling to express there being just the right amount of something – not too

much, but not too little. While the English may not have a word for it, the

good news is that the Greeks, the Norwegians, the Dutch or possibly the Inuits

probably do.

Whether it’s the German spielzeug (that instinctive feeling of ‘rightness’) or

the Indonesian jayus (a joke so poorly told and so unfunny that you can’t help

but laugh), this delightful smörgåsbord of wonderful words from around the

world will come to the rescue when the English language fails. Part glossary,

part amusing musings, but wholly enlightening and entertaining, The Greeks Had

a Word For It means you’ll never again be lost for just the right word.