|

|

This article uses bare URLs, which are uninformative and vulnerable to link rot. Please consider converting them to full citations to ensure the article remains verifiable and maintains a consistent citation style. Several templates and tools are available to assist in formatting, such as Reflinks (documentation), reFill (documentation) and Citation bot (documentation). (August 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

First edition |

|

| Author | Barry Unsworth |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Hutchinson |

|

Publication date |

1967 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 224 pp |

The Greeks Have a Word For It is the second novel by Booker Prize-winning author Barry Unsworth published by Hutchinson in 1967. It has since been republished by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in 1993 and W. W. Norton & Company in 2002.[1] It has been praised for its ‘utterly convincing characterizations’.[2]

Background[edit]

It is set in Athens in the aftermath of the Greek Civil War and draws on the author’s own experiences teaching English as a foreign language, satirizing many members of the British Council in Athens.[3]

Plot introduction[edit]

Two men arrive in Athens on the same boat. Kennedy an Englishman intends to make a living teaching English and devises a scam to make money fast. Mitsos is returning to Greece after many years away but finds it impossible to escape the memories of the brutal deaths of his parents at the hands of fellow Greeks during the war and an opportunity arises to take revenge. The two men meet briefly as they disembark the boat but their stories then diverge only to come together at the end of the book with fatal results.[4][5]

References[edit]

- ^ «The Greeks Have a Word for It by Barry Unsworth».

- ^ http://books.wwnorton.com/books/detail.aspx?id=6939

- ^ «New English Readers — Morality Play».

- ^ «Powell’s Books | the World’s Largest Independent Bookstore».

- ^ «The Greeks Have a Word for it : Barry Unsworth : 9781857990027».

Novels by Barry Unsworth |

|---|

|

You’ve probably heard the saying “the Greeks had a word for it” (sometimes given as “the Greeks have a word for it”).

But you may not be aware of how this enigmatic idiomatic expression got its start.

It was launched into our language with a splash on September 25, 1930, when a bawdy play titled The Greeks Had a Word for It opened on Broadway.

The play was written by the Missouri-born American playwright, poet and screenwriter Zoe Akins (1886-1958). And, she is generally given credit for coining the phrase.

Several of Akins’ plays had been produced prior to that night.

One of them — Declassée, starring Ethel Barrymore — was a big hit on Broadway in 1919.

In 1935, Akins won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama for her play The Old Maid (1935).

But her most remembered play (and play on words) is The Greeks Had a Word for It, a comedy about three young “gold diggers” on the hunt for wealthy men.

What was the “It” the Greeks had a word for?

Well, obviously, “It” is a reference to something you weren’t supposed to mention directly at the time.

I’m guessing you can figure “It” out. If not, here’s a hint…

In 1932, Twentieth Century Fox made a film version of the play, starring Joan Blondell, Madge Evans and Ina Claire.

The original title of the film was The Greeks Had a Word for Them.

Why the change?

Because the producers worried that the word “It” would be deemed too blatantly salacious by the censors who enforced the The Motion Picture Production Code of 1930 (a.k.a. the Hays Code), which was designed to prevent “obscenity” and violence in films.

So, initially, they changed “It” to “Them.”

But then even the revised title raised concerns, since some of the possible words for “Them” that people thought it meant could also be considered too vulgar.

Thus, the name of the film was ultimately changed to Three Broadway Girls.

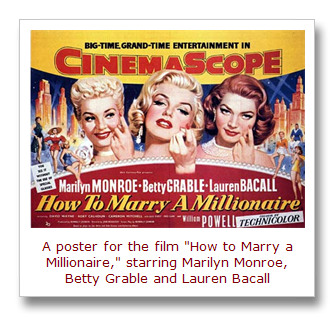

In 1953, Zoe Akins’ play The Greeks Had a Word for It was used as the basis for a much more famous film starring Marilyn Monroe, Betty Grable and Lauren Bacall.

It was titled How to Marry a Millionaire and it helped launch Marilyn into the top echelon of superstardom.

Although that film also avoided using Akins’ original play title, it revived interest in her and her plays.

As a result, she was hired as a scriptwriter for some of the most prestigious early dramatic series developed for television in the 1950s, including the Kraft Television Theatre and Screen Directors Playhouse.

Her phrase “the Greeks had a word for it” survived and outlived the stuffy censors of earlier decades.

It became a common saying that is still used for humorous effect.

What “It” refers to nowadays varies depending on the context and does not always mean something “obscene” – though typically “It” still does.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Post them on my quotations Facebook group.

Related reading and viewing…

About the Book

Do you ever search in vain for exactly the right word? Perhaps you want

to articulate the vague desire to be far away? Or you can’t quite convey

that odd urge to go outside and check to see if anyone is coming? Maybe

you’re struggling to say there’s just the right amount of something –

not too much, but not too little? While the English may not have a word

for it, the good news is that the Greeks, the Norwegians, the Dutch or

possibly the Inuit probably do.

Whether it’s mafan (a Mandarin word for when you just can’t be

bothered) or the Indonesian jayus (a joke so poorly told and so

unfunny that you can’t help but laugh), this delightful smorgasbord of

wonderful words from around the world will come to your rescue when the

English language fails. Part glossary, part amusing musings, but wholly

enlightening and entertaining, The Greeks Had a Word For It means

you’ll never again be lost for just the right word.

Dedication

For Sam, Abi and Rebecca,

and Lucy, Sophie and Tom

Foreword

Words are among the most important things in our lives – somewhere just

behind air, water and food. For a start, they’re the way we pass on our

thoughts from one to another and from generation to generation. Without

words, it’s hard to see how mankind could ever have evolved from

ape-like creatures grunting at the entrance to a cave and wondering

where they were going to find their next meal.

But words do more than that. They help us define our emotions, our

experiences and the things we see. Put a name to something and you have

started out on the road to understanding it.

To look at the figures, you’d think that we already have more than

enough words in English – estimates vary between five hundred thousand

and just over two million, depending on how you count them. And most

educated people use no more than twenty thousand words or so, which

means that we ought to have plenty to spare. Yet we’ve all had those

moments when we want to say something and we can’t find exactly the

right one. Words are like happy memories – you can never have enough

of them in your head.

And, maybe most important of all in these days of global interaction,

when we need to understand each other more than ever before, words say

something about us. If people need a word for a particular feeling, or

action, or experience, it suggests that they find it important in their

lives – the Australian Aboriginals, for instance, have a word that

conveys a sense of intense listening, of contemplation, of feeling at

one with history and with creation. In Spanish, there’s a word for

running one’s fingers through a lover’s hair, and in French one for the

sense of excitement and possibility that you may feel when you find

yourself in an unfamiliar place.

Words bring us together. They’re precious. And if they’re sometimes very

funny, too – well, how good is that?

Matters of the Heart

Physingoomai

(Ancient Greek)

Traditionally, sexual excitement as a result of eating garlic; but in a

modern sense, the use of inappropriate adornments to enhance sexual

attraction

THERE ARE SOME foreign words the English language clearly needs – the

case for them is so obvious that it hardly needs to be put. Others

require a little more advocacy on their behalf. Take, for example, the

Ancient Greek word physingoomai (fiz-in-goo-OH-mie).

It refers to someone who gets over-confident and sexually excited as a

result of eating garlic. Fighting cocks were frequently fed garlic and

onions before a bout because the Greeks – and later cockfight

aficionados – believed that it would make the birds fiercer. The idea is

that if men were to follow the example of the fighting cocks and gorge

on garlic before going on a date, there would be no holding them back.

Whether or not garlic makes men horny, it certainly makes them smelly

and thus less pleasant to be close to. As a result, even in these days

when programmes about cooking are all over the television and when

people seem more than happy to talk publicly about their sexual

preferences, it seems unlikely that it is a word that is going to be

used frequently outside the rather restricted world of cockfighting.

Even the Ancient Greeks don’t seem to have required it all that often,

since the word itself appears only once in the entire canon of Greek

literature, referring to some soldiers from the town of Megara in a

comedy by Aristophanes.

In the play, however excited the soldiers get, it’s apparent that they

are going to have serious difficulties persuading any self-respecting

Ancient Greek girls to kiss their garlic-reeking lips. The remedy they

have sought to increase their sexual potency at the same time greatly

reduces their ability to take advantage of it.

And there lies the clue to why physingoomai would be such a useful

term in English. Young men who douse themselves in the sort of cheap

aftershave that strips the lining from your nasal passages at first

whiff; middle-aged men wearing blue jeans so tightly belted around where

their waist used to be that their bellies sag opulently over the top;

women of a certain age wearing clothes that would have been daring on

their daughters – they are all, if they only knew it, falling into the

same trap as the Megaran soldiers.

The adornments they have chosen to boost their confidence and make them

more attractive to potential partners are exactly the things that will

put those partners off. Cheap aftershave, tight belts and sagging

bellies, and clothes that have been clearly stolen from your daughter’s

wardrobe can be as effective as a garlic overdose in keeping people at

arm’s length. Instead of whatever it was they were hoping for, those who

rely on them to enhance their sexual appeal are likely to suffer what we

might call a physingoomai experience. And there are few more

physingoomai experiences than showing off by using long words to try

to impress someone. Just talking about physingoomai could lead to the

most humiliating physingoomai experience of all.

Cafuné

(Brazilian Portuguese)

Closeness between two people – for example, to run one’s fingers

tenderly through someone’s hair

Think for a moment of the gentleness of affection. It needs a tone and a

language of its own – not the urgent, demanding words of love and

passion, but gentle, undemanding affection, the sort of love that asks

for nothing. It is often so diffident and unassuming that it may

sometimes seem to take itself – although never its object – for granted.

It may be the warm, safe, family feeling between a mother or father and

their child, or the love of grandparents for their grandchildren;

perhaps it is the closeness between two people that may some day turn

into love, or it may be the relaxed fondness that remains when the fire

of a passionate affair has burned low. Either way, it demands its own

expression.

In Brazil, they have a phrase that works – fazer cafuné em alguém

means to show affection of exactly that sort. More precisely, cafuné

(caf-OO-neh) often describes the act of running one’s fingers

through somebody’s hair – possibly lulling them to sleep, or possibly

simply expressing a drowsy fellow-feeling. Between two lovers, it might

contain the gentlest hint of a sexual promise, precisely capturing the

tender longing of the early days of a couple’s time together.

Our vocabulary for ideas, thoughts and abstractions comes mainly from Latin. Though it gave us directly only about 20% of the words we use day-to-day, Latin was the only written language in use before the renaissance, and it was the language of both faith and scholarship.

The story does not end there, however. Latin, in turn, was an evolution from a mixture of other dialects and languages, including a large helping from ancient Greece.

Why does this matter? It matters because a large budget of words in English are made up of Greek words, especially those terms used to describe ideas and concepts. People in most jobs may never need to use (or understand) the word “anthropomorphism,” for example. But if you go to college, rest assured that it will come up. If you know a little Greek, the word is not mysterious at all. “Anthropos” means “man” — as in mankind — and then “–morph” is a combining term meaning “having the shape of.” The “–ism” particle is, as you probably know, a flag for a belief system, practice or method of thinking. So this word means the practice of attributing human-like qualities to non-human entities, whether gods, animals or inanimate objects.

It’s fair to assume that you will not be learning Greek, especially ancient or New Testament Greek, any time soon. So the second best solution is to learn the meanings of these Greek-origin combination forms found so often in educated English writing. These are word particles that the Romans found useful to incorporate into Latin, and now, a couple of millennia later, they appear in English. They are called “morphemes,” and the study of them is one of the three areas embraced within the general heading of “grammar.” Here I’ve included them under “Vocabulary.”

What follows is a table of 95 morphemes that come to us from Greek, together with their meanings and examples of English words that contain them. The Greek word is also given, in the Greek alphabet (which you would do well to learn) and in our alphabet (called the Latin alphabet). If you master these morphemes, you will have the key to thousands of English terms. The table is paginated in groups of 20.

Greek Morphemes

| Meaning | Example | In English Usage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| acr- | height, summit, tip | ἄκρος (ákros) «high», «extreme» | acrobatics, acrophobia, acropolis |

| aero- | air, atmosphere | ἀήρ, ἀέρος (āḗr, āéros) «air» | aerobic, aerodynamic, aeronautics, aerosol |

| aesth- | feeling, sensation | αἰσθάνεσθαι ( aisthánesthai ) «to perceive» | aesthetics, anaesthetic |

| aether-, ether- | upper pure, bright air | αἴθειν ( aíthein ), αἰθήρ ( aithḗr ) | ether, ethereal |

| alg- | pain | ἄλγος ( álgos ), ἀλγεινός, ἀλγεῖν ( algeîn ), ἄλγησις ( álgēsis ) | analgesic, neuralgia, nostalgia |

| amph-, amphi- | both, on both sides of, both kinds | ἀμφί (amphí) «on both sides» | amphibious, amphitheatre |

| an-, a-, am-, ar- | not, without | ἀν-/ἀ- «not» | ambrosia, anaerobic, anhydrous, atheism, atypical |

| anem- | wind | ἄνεμος (ánemos) | anemometer, anemone |

| ant-, anti- | against, opposed to, preventive | ἀντί (antí) «against» | antagonize, antibiotic, antipodes |

| anthrop- | human | ἄνθρωπος (ánthrōpos) «man» | anthropology, misanthrope, philanthropy |

| archae-, arche- | ancient | ἀρχαῖος ( arkhaîos ) «ancient» from ἀρχή ( arkhḗ ) «rule» | archaeology, archaic |

| arct- | Relating to the North Pole | ἄρκτος (árktos) «bear» (Ursa Major), ἀρκτικός (arktikós) | Antarctica, Arctic Ocean |

| aster-, astr- | star, star-shaped | ἄστρον ( ástron ) «star» | aster, asterisk, asteroid, astrology, astronomy, astronaut |

| aut-, auto- | self; directed from within | αὐτός (autós) «self», «same» | autarchy, authentic, autism, autocracy, autograph, automatic, autonomy |

| bapt- | dip | βάπτειν (báptein) | baptism, baptize |

| bio-, bi- | life | βίος ( bíos ) «life» | biography, biohazard, biology |

| botan- | plant | βοτάνη, βότανον (botánē, bótanon) | botanist, botany |

| cardi- | heart | καρδιά (kardía) | cardiac, cardiology, electrocardiogram |

| caust-, caut- | burn | καυστός/καυτός (kaustós) | calm, caustic, cauterize, holocaust |

| chore- | relating to dance | χορεία ( khoreia ) «dancing in unison» | choreography, chorus |

| chrom- | color | χρῶμα (chrōma) | chromatic, chrome, chromosome, monochrome |

| chron- | time | χρόνος (chronos) | anachronism, chronic, chronicle, chronology, chronometer, synchronize |

| -cracy, -crat | government, rule, authority | κράτος (krάtos), κρατία (kratía) | aristocracy, autocrat, bureaucracy, democrat, plutocracy, technocrat, theocracy |

| crypt- | hidden | κρύπτειν ( kruptein ) «to hide» | apocryphal, cryptic, cryptography |

| dec- | ten | δέκα ( déka ) «ten» | decade, Decalogue, decathlon |

| dem- | people | δῆμος (dēmos) | demagogue, democracy, demography, epidemic |

| di- | two | δι- ( di- ) | diode, dipole |

| dia- | apart, through | διά (diá) | diagram, dialysis, diameter |

| dyna- | power | δύναμις (dúnamai) | dynamic, dynamite, dynamo, dynasty |

| ec- | out | ἐκ (ek) | eccentric, ecstasy, ecstatic |

| eco- | house | οἶκος (oikos) | ecology, economics, ecumenism |

| ep-, epi- | above, upon, outer | ἐπί (epi) | epicenter, epidemic, epitaph, epiphany |

| ethn- | people, race, tribe, nation | ἔθνος (ethnos) | ethnic, ethnicity |

| eu- | well, good | εὖ (eu) | euphoria, euthanasia, eulogy |

| ger- | old | γέρων, γέροντος (gérōn, gérontos) | geriatric, gerontocracy |

| gloss-, glot- | tongue | γλῶσσα (glóssa), γλωττίς (glōttís) | epiglottis, gloss, glossary, polyglot |

| glyph- | carve | γλύφειν (glúphein) | glyph, glyptograph, petroglyph |

| graph- | draw, write | γράφειν ( gráphein ) | autograph, graph, graphic, graphite, holograph, monograph, orthography, paragraph, photograph, telegraphy |

| gymn- | nude | γυμνός (gumnós) | gymnasium, gymnastics |

| hemi- | half | ἥμισυς (hēmisus) | hemicycle, hemisphere |

| heter- | different, other | ἕτερος (heteros) | heterodoxy, heterogeneous, heterosexual |

| hol- | whole | ὅλος (holos) | holistic, holography |

| hom- | same | ὁμός (homos) | homogeneous, homophone, homonym, homosexual |

| hydr- | water | ὕδωρ (hudōr) | dehydrate, hydrant, hydraulic, hydrogen, hydrolysis, hydrophily, hydrophobia, hydrous |

| hyp- | under | ὑπό (hupo) | hypoallergenic, hypodermic, hypothermia |

| hyper- | above, over | ὑπέρ (huper) | hyperactive, hyperbole |

| hypn- | sleep | ὕπνος (hupnos) | hypnosis, hypnotize |

| idi- | own, peculiarity | ἴδιος (ídios), «private, personal, one’s own» | idiom, idiosyncrasy, idiot |

| is-, iso- | equal, same | ἴσος (ísos) | isometric, isomorphic, isosceles |

| kine-, cine- | movement, motion | κινεῖν ( kineîn ), κίνησις ( kínēsis ), κίνημα ( kínēma ) | cinema, kinesthetic, kinetic, telekinesis |

| klept- | steal | κλέπτειν ( kléptein) | kleptomania, kleptocracy |

| lith- | stone | λίθος (lithos) | megalith, Mesolithic, monolith, Neolithic |

| log-, -logy | word, reason, speech, thought | λόγος ( logos ), λογία ( logia ) | apology, dialogue, etymology, eulogy, logic, monologue, neologism, prologue, terminology, theology |

| macro- | long | μακρός (makrós) | macrobiotic, macroeconomics, macron |

| mania | mental illness, craziness | μανία (manίā) | kleptomania, mania, maniac, pyromania |

| meta- | above, among, beyond | μετά (metá) | metabolism, metamorphosis, metaphor, metaphysics, meteor, method |

| meter-, metr- | measure | μέτρον (métron) | barometer, diameter, isometric, meter, metronome, parameter, perimeter, symmetric, telemetry, thermometer |

| micro- | small | μικρός (mikrós) | microcosm, microeconomics, micrometer, microphone, microscope |

| mim- | repeat | μιμεῖσθαι ( mīmeîsthai ), μίμος ( mimos ) | mime, mimeograph, mimic, pantomime |

| mis- | hate | μισεῖν ( miseîn ) | misanthrope, misogynist, misotheism |

| mne- | memory | μνήμη (mnēmē) | amnesia, amnesty, mnemonic |

| mon- | alone, one | μόνος (mónos) | monarchy, monastery, monolith, monopoly, monotone |

| mor- | foolish, dull | μωρός (mōrós) | moron, oxymoron, sophomore |

| morph- | form, shape | μορφή (morphē) | amorphous, anthropomorphism, endomorph, metamorphosis, morpheme, morphology, polymorphic |

| myth- | story | μῦθος (mûthos) | myth, mythic, mythology |

| narc- | numb | νάρκη (narkē) | narcolepsy, narcosis, narcotic |

| naut- | ship | ναύτης ( nautes ) | astronaut, nautical |

| ne-, neo- | new | νέος (neos) | Neolithic, neologism, neonate, neophyte |

| necr- | dead | νεκρός (nekros) | necrophobia, necrotic |

| nom- | arrangement, law, order | νόμος (nomos) | astronomy, autonomous, gastronomy, metronome, numismatic, polynomial, taxonomy |

| -oid | like | -οειδής (-oeidēs) | asteroid, humanoid, organoid |

| olig- | few | ὀλίγος ( oligos ) | oligarchy, oligopoly |

| pan- | all | πᾶς, παντός (pas, pantos) | Pan-American, panacea, pandemic, pandemonium, panoply |

| path- | feeling, disease | πάθος (pathos) | antipathy, apathy, empathy, pathetic, pathology, sociopath, sympathy |

| peri- | around | περί (perí) | perimeter, period, periphery, periscope |

| pher-, phor- | bear, carry | φέρω ( pherō ), φόρος ( phoros ) | metaphor, pheromone |

| phil-, -phile | love, friendship | φιλέω (phileō) | bibliophile, philanthropy, philharmonic, philosophy |

| phob- | fear | φόβος (phobos) | acrophobia, claustrophobia, homophobia, hydrophobia |

| phos-, phot- | light | φῶς, φωτός ( phōs , phōtos ) | phosphor, phosphorus, photic, photo, photoelectric, photogenic, photograph, photosynthesis |

| physi- | nature | φύσις (phusis) | physics |

| plut- | wealth | πλοῦτος (ploutos) | plutocracy |

| pneu- | air, breath, lung | pnein, πνεῦμα (pneuma) | apnoea, pneumatic, pneumonia |

| pod- | foot | πούς, ποδός ( pous , podos ) | antipode, podiatry, tripod |

| pole-, poli- | city | πόλις (polis) | acropolis, cosmopolitan, metropolis, police, policy, politics |

| polem- | war | πόλεμος (polemos) | polemic, polemology |

| poly- | many | πολύς (polus) | polyandry, polygamy, polygon, polytheistic |

| pro- | before, in front of | πρό (pro) | prologue, prominent |

| prot- | first | πρῶτος (prōtos) | protagonist, protocol, protoplasm, prototype, protozoan |

| pseud- | false | ψευδής (pseudēs) | pseudonym |

| psych- | mind | ψυχή (psuchē) | psyche, psychiatry, psychology, psychosis |

| scop-, scept- | look at, examine, view, observe | σκέπτομαι, σκοπός (skeptomai, skopos) | horoscope, microscope, periscope, skeptic, stethoscope, telescope |

| soma- | body | σῶμα, σώματος (sōma, sōmatos) | psychosomatic, somatotype |

| soph- | wise | σοφός (sophos) | philosophy, sophistry, sophistication, sophomoric |

| syn-, sy-, syl-, sym- | with | σύν (sun) | symbol, symmetry, sympathy, synchronous, synonym |

| tele- | far, end | τῆλε (tēle) | telegram, telemetry, telepathy, telephone, telescope, television |

| xen- | foreign | ξένος (xenos) | xenogamy, xenophobia, xenon |

About the Book

Do you ever search in vain for exactly the right word? Perhaps you want to articulate the vague desire to be far away? Or you can’t quite convey that odd urge to go outside and check to see if anyone is coming? Maybe you’re struggling to say there’s just the right amount of something – not too much, but not too little? While the English may not have a word for it, the good news is that the Greeks, the Norwegians, the Dutch or possibly the Inuit probably do.

Whether it’s mafan (a Mandarin word for when you just can’t be bothered) or the Indonesian jayus (a joke so poorly told and so unfunny that you can’t help but laugh), this delightful smorgasbord of wonderful words from around the world will come to your rescue when the English language fails. Part glossary, part amusing musings, but wholly enlightening and entertaining, The Greeks Had a Word For It means you’ll never again be lost for just the right word.

Dedication

For Sam, Abi and Rebecca,

and Lucy, Sophie and Tom

Foreword

Words are among the most important things in our lives – somewhere just behind air, water and food. For a start, they’re the way we pass on our thoughts from one to another and from generation to generation. Without words, it’s hard to see how mankind could ever have evolved from ape-like creatures grunting at the entrance to a cave and wondering where they were going to find their next meal.

But words do more than that. They help us define our emotions, our experiences and the things we see. Put a name to something and you have started out on the road to understanding it.

To look at the figures, you’d think that we already have more than enough words in English – estimates vary between five hundred thousand and just over two million, depending on how you count them. And most educated people use no more than twenty thousand words or so, which means that we ought to have plenty to spare. Yet we’ve all had those moments when we want to say something and we can’t find exactly the right one. Words are like happy memories – you can never have enough of them in your head.

And, maybe most important of all in these days of global interaction, when we need to understand each other more than ever before, words say something about us. If people need a word for a particular feeling, or action, or experience, it suggests that they find it important in their lives – the Australian Aboriginals, for instance, have a word that conveys a sense of intense listening, of contemplation, of feeling at one with history and with creation. In Spanish, there’s a word for running one’s fingers through a lover’s hair, and in French one for the sense of excitement and possibility that you may feel when you find yourself in an unfamiliar place.

Words bring us together. They’re precious. And if they’re sometimes very funny, too – well, how good is that?

Matters of the Heart

Physingoomai

(Ancient Greek)

Traditionally, sexual excitement as a result of eating garlic; but in a modern sense, the use of inappropriate adornments to enhance sexual attraction

THERE ARE SOME foreign words the English language clearly needs – the case for them is so obvious that it hardly needs to be put. Others require a little more advocacy on their behalf. Take, for example, the Ancient Greek word physingoomai (fiz-in-goo-OH-mie).

It refers to someone who gets over-confident and sexually excited as a result of eating garlic. Fighting cocks were frequently fed garlic and onions before a bout because the Greeks – and later cockfight aficionados – believed that it would make the birds fiercer. The idea is that if men were to follow the example of the fighting cocks and gorge on garlic before going on a date, there would be no holding them back.

Whether or not garlic makes men horny, it certainly makes them smelly and thus less pleasant to be close to. As a result, even in these days when programmes about cooking are all over the television and when people seem more than happy to talk publicly about their sexual preferences, it seems unlikely that it is a word that is going to be used frequently outside the rather restricted world of cockfighting. Even the Ancient Greeks don’t seem to have required it all that often, since the word itself appears only once in the entire canon of Greek literature, referring to some soldiers from the town of Megara in a comedy by Aristophanes.

In the play, however excited the soldiers get, it’s apparent that they are going to have serious difficulties persuading any self-respecting Ancient Greek girls to kiss their garlic-reeking lips. The remedy they have sought to increase their sexual potency at the same time greatly reduces their ability to take advantage of it.

And there lies the clue to why physingoomai would be such a useful term in English. Young men who douse themselves in the sort of cheap aftershave that strips the lining from your nasal passages at first whiff; middle-aged men wearing blue jeans so tightly belted around where their waist used to be that their bellies sag opulently over the top; women of a certain age wearing clothes that would have been daring on their daughters – they are all, if they only knew it, falling into the same trap as the Megaran soldiers.

The adornments they have chosen to boost their confidence and make them more attractive to potential partners are exactly the things that will put those partners off. Cheap aftershave, tight belts and sagging bellies, and clothes that have been clearly stolen from your daughter’s wardrobe can be as effective as a garlic overdose in keeping people at arm’s length. Instead of whatever it was they were hoping for, those who rely on them to enhance their sexual appeal are likely to suffer what we might call a physingoomai experience. And there are few more physingoomai experiences than showing off by using long words to try to impress someone. Just talking about physingoomai could lead to the most humiliating physingoomai experience of all.

Cafuné

(Brazilian Portuguese)

Closeness between two people – for example, to run one’s fingers tenderly through someone’s hair

Think for a moment of the gentleness of affection. It needs a tone and a language of its own – not the urgent, demanding words of love and passion, but gentle, undemanding affection, the sort of love that asks for nothing. It is often so diffident and unassuming that it may sometimes seem to take itself – although never its object – for granted. It may be the warm, safe, family feeling between a mother or father and their child, or the love of grandparents for their grandchildren; perhaps it is the closeness between two people that may some day turn into love, or it may be the relaxed fondness that remains when the fire of a passionate affair has burned low. Either way, it demands its own expression.

Читать дальше

Random House, 1 окт. 2015 г. — Всего страниц: 208

0 Отзывы

Google не подтверждает отзывы, однако проверяет данные и удаляет недостоверную информацию.

Do you ever search in vain for exactly the right word? Perhaps you want to articulate the vague desire to be far away. Or you can’t quite convey that odd urge to go outside and check to see if anyone is coming. Maybe you’re struggling to express there being just the right amount of something – not too much, but not too little. While the English may not have a word for it, the good news is that the Greeks, the Norwegians, the Dutch or possibly the Inuits probably do.

Whether it’s the Norwegian forelsket (that feeling of euphoria at the start of a love affair) or the Indonesian jayus (a joke so poorly told and so unfunny that you can’t help but laugh), this delightful smörgåsbord of wonderful words from around the world will come to the rescue when the English language fails. Part glossary, part amusing musings, but wholly enlightening and entertaining, The Greeks Had a Word For It means you’ll never again be lost for just the right word.

THE GREEKS HAVE

A WORD FOR IT

BARRY UNSWORTH

THE GREEKS HAVE

A WORD FOR IT

1

At eleven o’clock in the morning the steamer entered the bay and made for the harbour. Kennedy and most of the other passengers came up on deck, to lean on the rail, acknowledge the fact of their arrival. Mrs Pouris didn’t though, and Kennedy thought this strange, after her patriotic sentiments during the voyage. Perhaps she had left her packing too late. One of the sailors began to attach strings of bunting to the mast, the Greek colours, white and blue. This was Piraeus then, the port of Athens; the usual installations, a few chimneys with industrial plumage, tawny hills beyond. He was glad to have arrived.

As the ship slowed, the breeze dropped and Kennedy felt a prickle of sweat on his upper lip. He had always been prone to sweating, and here, though still only the end of April, it was very hot. The sky, a pure blue earlier, had whitened and glazed in mid-morning and the water of the bay was the colour of oiled gunmetal. The ship’s wake was healed almost before foam showed.

‘Soon be on the old terra firma again,’ Kennedy remarked to several of the nearer passengers, none of whom quite looked at him and none of whom replied. He took out a handkerchief, somewhat discoloured, and wiped his mouth and palms. Then he walked forward a few paces, keeping near the rail, and stopped again on the covered part of the deck. From here he looked round once more for Mrs Pouris. Where could she have got to? She had not yet given him her address in Athens.

They were coming into their moorings now, to the accompaniment of much shouting from officers and crew, who continued to lack, in this final phase, the air of quiet authority which might, for an Englishman at least, have induced confidence in their management; contriving to look expert without suggesting competence. The sense of this, not however highly articulated, since most of Kennedy’s feelings remained in the undergrowth, the sense of potential disaster on the boat, had given him a certain pleasure throughout the voyage.

A small unshaven man in a white yachting cap jumped up and down on the quay, shouting. He made a gesture as if to ward the ship off. Kennedy had not had time to learn any Greek, but he observed with delight that a mistake had been made. There was a grinding noise as the ship scraped against the wall of the dock. That would cost more than his fare to put right, anyway. All breakdowns and untoward events, hitches in procedure, pleased him in some degree, aligning his personal irresponsibility with that of the cosmos.

A small group of people stood waiting below the ship, unmoving, gazing upwards, waiting to unload on the arriving voyagers their accumulated emotions. Around them swarmed those who might make money, conceivably: touts, pimps, porters, taxi-drivers, the agents for hotels. The gang-plank was down and the first passengers had begun to leave the ship. One or other group, the still or the mobile, would claim most of these, for whom landing meant a renewal of love or obligation. But not for him, Kennedy knew, with a faint, involuntary contempt. No one was going to profit in either way from his arrival. … Suddenly he saw Mrs Pouris getting off the ship. ‘Mrs Pouris!’ he called, smiling at her back, then again more loudly, ‘Mrs Pouris!’ But she did not look round, seemed in fact to accelerate. Surely she must have heard?

He glanced down over the side. The engines had stopped, water slapped against the hulk. He counted five oranges bobbing about in the dirty water. ‘Will passengers please leave the ship now,’ said a voice on the loudspeaker. Turning his head, Kennedy saw the pale young Greek standing alone at the rail quite close. He had been alone throughout the voyage. Kennedy had seen him occasionally in the bar and on deck, always alone, but had not spoken to him, concentrated as he had been on Mrs Pouris, whose eyes were the colour of raisins, who smelled of hot silk and lotions not immediately nameable. Each evening he had slipped through the barrier into the first-class section of the ship, to pace with Mrs Pouris up and down the deck. And now she had fled — there was no other word for it. She had received, perhaps, a warning, read a horoscope? Or, Kennedy wondered uneasily, perhaps he had not been sufficiently delicate in the insinuation of his poverty?

He had just decided to speak to the Greek when the latter glanced round at him and smiled, so there was a moment of what seemed recognition between them, something acknowledged in common. This was encouraging and Kennedy returned the smile promptly and on a larger scale. Perhaps something yet could be salvaged. His was a face constructed, it would seem, for smiling, broad, high cheek-boned, the wide mouth notched as it were for gradations of glee, curving up towards freckles and very round blue eyes. The eyes did not change much, whatever the degrees recorded below, and they had a lingering boldness of regard.

‘Bit of a crush down there,’ Kennedy said, hoping the other understood English. ‘Ce n’est pas encore possible de sortir,’ he added haltingly. A lot of them knew a bit of French. He had learned his as an army clerk at S.H.A.P.E. headquarters in Paris, before certain dealings had led to his dishonourable discharge. ‘No sense in going down there yet, c’est pas la peine …’

‘I understand English,’ the Greek said. He had a small oval face and very beautiful dark eyes. And he spoke English perfectly, without a trace of accent. One might just as well wait,’ he said. This linguistic accomplishment was unexpected, disconcerting, hinting at a familiarity with Kennedy’s countrymen, a faculty of assessment, that might be inconvenient. Kennedy paused, somewhat warily.

‘Just coming back from your holidays then?’ he said at last, in a congratulatory tone.

‘No, I have come for a visit. I am Greek, but I have been living in England for several years.’ He turned to look over the side again, at the passengers still descending. They were predominantly Greek. Speaking in loud tones, using their elbows freely, they jostled for precedence. It seemed to him that he remembered this fractiousness, this way of seeking in every occasion small personal triumphs. He was back among his people, many of whom were carrying huge Italian dolls wrapped in polythene.

‘That explains why you speak English so well,’ observed Kennedy, taking out his handkerchief. ‘It will be good to get on to terra firma again, won’t it?’ he added.

‘Les passagers sont priés …’ began the loudspeaker. Time was getting short.

‘Where are you staying?’ Kennedy asked. ‘Have you got somewhere to stay?’

‘Oh yes, I am going to live at my cousin’s house in Kifissia. That is near Athens, a suburb really.’

‘I’m not fixed up yet,’ Kennedy said, ‘I’m looking for a place to stay, just for a few days.’

‘There are some good hotels and not expensive, particularly in the neighbourhood of Omonia Square.’

‘To tell you the truth, old boy,’ Kennedy said, in a confidential manner, ‘I’m a bit short at the moment. Just for the next few days you know, till my money comes through. Even a cheap hotel …’

The other said nothing to this.

‘I thought from the first moment I saw you,’ Kennedy said, ‘that you were an understanding fellow. My name is Kennedy, by the way, Bryan Kennedy.’

‘Mitsos, Stavros Mitsos.’

‘Put it there,’ said Kennedy. He boosted his smile. ‘I’ve heard that the Greeks are a hospitable people,’ he said.

‘They are considered to be so,’ Mitsos replied. ‘I think it is time to be getting off the boat now,’ he added. He took a few steps towards the stairway leading to the lower deck.

‘Just a minute,’ Kennedy said, falling into step beside him. He hardly knew himself why he was thus persisting with such an obviously unpromising subject. It was not as though he were without immediate cash, even. But the flight of Mrs Pouris had inflamed his predatory instinct, he

was possessed by a vindictive desire to make a touch before he got off the boat. ‘I know you are a complete stranger,’ he said, ‘but I’ve got something here I’d like you to see.’ He fumbled in the inside pocket of his jacket and produced after a moment a frayed leather wallet. ‘I have several testimonials here,’ he said. ‘This one is from the Bishop of Jarrow, written in his own hand. Read it. I think you will be impressed.’

‘There is hardly time now,’ Mitsos said politely. He looked up at the pleasantly smiling face of the Englishman, striving as he did so to keep his impression general, preserve the other’s humanity, not succumb to the details of the features, the configuration of the nostrils, the large-pored skin, the shine of perspiration round the mouth. It had been increasingly difficult for him lately to spread his scrutiny over the whole area of anything without becoming helplessly impaled on the details. The man was very tall, well over six feet, and broad-shouldered. He had short untidy hair the colour of wet straw. His round blue eyes had a delinquent fixity of regard and his green tweed suit was too heavy, quite unsuitable for this weather. A man, on the whole, difficult to place. But no words or gestures he went in for now could redeem the gross haste with which he had revealed his needs to a stranger.

Mitsos left the rail and moved towards the head of the stairway. ‘They will be swilling the decks down,’ he said, ‘and they will swill us too, if we do not hurry.’ And in fact sailors had appeared with buckets of water. Reluctantly Kennedy restored the wallet to its place in his bosom and they descended the stairs together to collect their luggage from outside the purser’s office; Kennedy a single battered suitcase held together by a strap, and the Greek two rather sumptuous cream-coloured grips. He was a frail, small-boned person and had some difficulty in getting down the gang-plank with these. Kennedy did not offer to help. Immediately they were off the boat Mitsos began to look around for a taxi.

‘I was wondering,’ Kennedy said, without much hope, ‘whether you might lend me a small sum of money, to tide me over. Two or three pounds, say. Say three pounds. On the strength of that testimonial, which you are quite at liberty to read. I have several others from Justices of the Peace, Members of Parliament, and so on.’ His hand strayed towards his wallet. He had every confidence in the impact of these documents on any person who could be persuaded to read them, since he had written them himself, had expended, in fact, much labour on their composition. ‘Let me see,’ he said, ‘in drachmas that would be …’

Mitsos said, ‘I can’t lend you anything, I’m afraid. I am not carrying much ready money with me.’

‘I see, yes,’ Kennedy said. ‘Never mind, old boy. Just a thought.’

‘I’m sorry. You can come with me in the taxi to Athens, if that suits you.’

‘Really? No, but look here …’ Kennedy hoisted his suitcase, gave the dock a comprehensive survey in the hope of seeing even now some sign of Mrs Pouris. But they seemed to be the only passengers left.

A man detached himself from a group standing near the dock gates and approached them. ‘Oriste, kyrie?’ he said. ‘Taxi.’ He took their luggage and they followed him through the gates and out into the crowded street. Trolley wires netted the sky overhead and yellow trolley-buses trundled past continually. The glare of the sun on white buildings hurt Kennedy’s eyes and he was confused by the shouts of men selling peanuts and lottery tickets and by the loud conversations between passing pedestrians.

‘I’ve heard that word before, that word “kyrie”,’ he said. ‘In masses.’ He did not attend masses, but knew this word meant God, in whom he believed with a certain resentful clammine passed through his mind without any sense of impiety how marvellous it would be if he could have claimed divine authorship for one of his testimonials. ‘Noisy, isn’t it?’ he said.

‘Greeks like noise, generally speaking,’ Mitsos replied. ‘Though I do not, myself.’

The taxi-driver opened the door for them and his golden molars flashed. ‘Oriste,’ he said again.

‘Now I think I must discuss the price with him,’ Mitsos said.

Rapid Greek ensued. Kennedy stood by. His was a resilient and essentially optimistic nature. Now he declined to consider the wounding behaviour of Mrs Pouris and the lesser rebuff he had received from Mitsos, and he suddenly felt delighted to be here and grateful to the thin-necked person with the carrying voice, whose face he had not properly seen, who had put him on to Greece; grateful to the impulse that had lasted long enough to set him down here, listening to an argument about a taxi fare conducted in an unintelligible tongue.

In the Chelsea Potter it had all begun. He had been standing there with a Guinness on a crowded Friday, wondering who to ring up. He had felt rich but chastened, with over seventy pounds in his pockets, commission from selling encyclopaedias from door to door to American service families, a job for which he had shown aptitude but which he had lost two days before through smelling of drink and making fairly determined overtures to some of the wives — the one with whom he had been most successful had subsequently complained. And then this voice from further down the bar: ‘You want to go to Greece, old man. I would, if I were single. Marvellous climate, bloody marvellous, four thousand years of history. Four thousand bloody years of history. They’re all dying to learn English over there. They need it, you see, being a commercial nation. Anyone could go over there and get a good living. You only have to be English.’ Which Kennedy indubitably was. There and then, watching the froth on his Guinness subside, he had thought, why not? Scraps of myth had come into his mind, culled from his haphazard but abundant reading; garlanded heifers and raped nymphs, marble columns, angular e’s. He would go. He would be a tutor. Amazingly his resolve had held, long enough for him to write his testimonials, get his ticket, look at summer suits without buying one; long enough to steer him through the people who would have liked to help him spend what remained of the seventy pounds. What remained of it reposed at that moment in his hip pocket.

Negotiation ceased, and they got in. The taxi shot forward, narrowly missing a group of small crop-haired boys playing with pebbles in the gutter, and inserted itself into the stream of traffic. Down the long straight road to Athens small box-like houses were strung out, many of their walls bearing advertisements for macaroni or Fixe beer. For some time they skirted a glittering sea. Numerous sections of the road were under repair and thunderous with drills. Half-naked men toiled in the dust which swirled up under the wheels of cars and buses. The taxi-driver drove nonchalantly, at great speed, one hand only on the wheel, the other arm outstretched along the seat. From time to time he turned his head completely round to make some comment. Kennedy felt frightened, and to lessen this feeling did not look at the road ahead at all, but only out of his nearside window. For this reason he did not see the Parthenon till Mitsos told him to look, and whatever he had been expecting it was not this delicate railing of pillars suspended above the noon haze of the approaching city, too remote to be quite believed in as a structure. Not that Kennedy had given much thought to the Parthenon beforehand; he was not much interested in monuments, but he decided now on a demonstration, possibly flattering to Mitsos, from whom he still had some small hopes of gain.

He said, ‘I’ve read a lot about it, of course, but …’ craning his head forward to look again. Mitsos watched him curiously. His pleasure and interest seemed genuine. Now he had slumped right down in his seat, twisting his large head to get a better view. No Greek would willingly have adopted so ungainly an attitude. Mitsos had never understood this physical carelessness of the English. His own body insisted on graceful reclinations. And what was this greed for an alien past?

The taxi proceeded more slowly now, among the thicker traffic of the city. They came out into Omonia Square. The fountains were playing there and the pavements were crowded. They went round the outer rim of the hub, selected finally the spoke of Stadion Street. Mitsos looked out of the window at rows of tall hoardings concealing, it seemed, areas of demolition. What had been there he cou

ld not now remember, though he struggled to do so, and this small failure caused him something like despair. Every lapse of memory or recognition seemed to threaten the purpose of his return, formed suddenly after so many years, his desire to readopt the city.

‘Where can I put you down?’ he asked.

Kennedy had been experiencing some disillusionment, travelling down this spacious but quite ordinary avenue with its shops and cinemas and restaurants. Though what he had been expecting he could not say. He glared sideways at Mitsos’ watch, conveniently exposed just now. Twelve-fifteen nearly. An awkward time. He felt thirsty. From the top pocket of his jacket he took a folded piece of paper. ‘This is where I want to go,’ he said, passing the paper to Mitsos. The address of the Cultural Centre was the only one of any use he had in Athens and he had made up his mind to go there first of all.

‘Ah, yes,’ Mitsos said. ‘That will be quite easy. The taxi will go up Vassilis Sofias. We can put you down quite close. A few minutes’ walk.’

‘Splendid,’ Kennedy said. ‘Perhaps I can give you a ring in a day or two? I don’t know anybody here.’

‘Athens is like a village, in some ways. We shall be sure to meet.’

‘Yes, but if I had your phone number …’

‘Here we are,’ Mitsos said. ‘This is where you must get out.’ He spoke to the taxi-driver and the taxi drew into the kerb and stopped. Kennedy disentangled his long legs from below the front seat and seized his suitcase.

‘Thanks again, old boy,’ Kennedy said. ‘We shall be seeing some more of each other, I daresay.’

‘I hope so. That is your way up, through there.’

Kennedy scrambled out and then leaned back into the taxi, extending his hand. They shook hands solemnly. Looking back as the taxi gathered speed again, Mitsos saw the Englishman standing tall and irresolute, holding his suitcase, his unseasonable green tweed suit patterned with the shadows cast by one of the acacias that lined the avenue. So much for that. He wondered about Kennedy for a few moments, then he forgot him completely. He stared out of the taxi window, rigidly holding off the sense of unreality that threatened to descend on him in the absence of familiar landmarks. I am coming home, he told himself.

Первое издание |

|

| Автор | Барри Ансуорт |

|---|---|

| Страна | объединенное Королевство |

| Язык | английский |

| Издатель | Hutchinson |

|

Дата публикации |

1967 |

| Тип СМИ | Печать (в твердой и мягкой обложке ) |

| Страницы | 224 стр. |

Греки Есть слово является вторым романом Букер выигрывающей автора Ансуорт опубликованного Hutchinson в 1967 г. С тех пор переиздана Вейденфельд & Николсон в 1993 году и WW Norton & Company в 2002 году получил высокую оценку за его «совершенно убедительные характеристики».

Задний план

Действие книги происходит в Афинах после Гражданской войны в Греции и основано на собственном опыте автора преподавания английского языка как иностранного , высмеивая многих членов Британского совета в Афинах.

Введение в сюжет

Двое мужчин прибывают в Афины на одной лодке. Кеннеди, англичанин, намеревается зарабатывать на жизнь преподаванием английского языка и изобретает мошенничество, чтобы быстро заработать деньги. Мицос возвращается в Грецию после многих лет отсутствия, но считает невозможным избавиться от воспоминаний о зверской смерти своих родителей от рук других греков во время войны, и появляется возможность отомстить. Двое мужчин ненадолго встречаются при высадке из лодки, но затем их истории расходятся, только чтобы сойтись в конце книги с фатальными результатами.