In the New Testament, the common word for God is the Greek word theos. Theos is the basis of the word theology, «the study of God.» Theos is used a number of different ways in the New Testament.

It Can Speak Of The True God

When the true God is spoken of, the word theos is used.

In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God [theos] and the Word was God (John 1:1).

It Can Refer To False Gods

The plural form of theos can refer to false Gods.

Indeed, even though there may be so-called gods [theos] in heaven or on earth — as in fact there are many gods and many lords (1 Corinthians 8:5)

The Greek word translated gods is the plural of theos.

The Word Also Can Mean Humans

Jesus used the word «gods» to refer to human rulers.

Jesus answered, «Is it not written in your law, «I said, you are gods’? If those to whom the word of God came were called «gods’-and the scripture cannot be annulled — can you say that the one whom the Father has sanctified and sent into the world is blaspheming because I said, «I am God’s Son (John 10:34-36).

Summary

Theos is the common word for God in the Greek New Testament. It normally refers to the true God. However it can also refer to false gods and even humans. The context must determine how it is to be understood.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

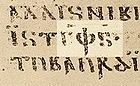

Earliest attestation of the Germanic word in the 6th-century Codex Argenteus (Mt 5:34)

The English word god comes from the Old English god, which itself is derived from the Proto-Germanic *ǥuđán. Its cognates in other Germanic languages include guþ, gudis (both Gothic), guð (Old Norse), god (Old Saxon, Old Frisian, and Old Dutch), and got (Old High German).

Etymology[edit]

The Proto-Germanic meaning of *ǥuđán and its etymology is uncertain. It is generally agreed that it derives from a Proto-Indo-European neuter passive perfect participle *ǵʰu-tó-m. This form within (late) Proto-Indo-European itself was possibly ambiguous, and thought to derive from a root *ǵʰeu̯- «to pour, libate» (the idea survives in the Dutch word, ‘Giet’, meaning, to pour) (Sanskrit huta, see hotṛ), or from a root *ǵʰau̯- (*ǵʰeu̯h2—) «to call, to invoke» (Sanskrit hūta). Sanskrit hutá = «having been sacrificed», from the verb root hu = «sacrifice», but a slight shift in translation gives the meaning «one to whom sacrifices are made.»

Depending on which possibility is preferred, the pre-Christian meaning of the Germanic term may either have been (in the «pouring» case) «libation» or «that which is libated upon, idol» — or, as Watkins[1] opines in the light of Greek χυτη γαια «poured earth» meaning «tumulus», «the Germanic form may have referred in the first instance to the spirit immanent in a burial mound» — or (in the «invoke» case) «invocation, prayer» (compare the meanings of Sanskrit brahman) or «that which is invoked».

Gaut[edit]

A significant number of scholars have connected this root with the names of three related Germanic tribes: the Geats, the Goths and the Gutar. These names may be derived from an eponymous chieftain Gaut, who was subsequently deified.[citation needed] He also sometimes appears in early Medieval sagas as a name of Odin or one of his descendants, a former king of the Geats (Gaut(i)), an ancestor of the Gutar (Guti), of the Goths (Gothus) and of the royal line of Wessex (Geats) and as a previous hero of the Goths (Gapt).

Wōdanaz[edit]

Some variant forms of the name Odin such as the Lombardic Godan may point in the direction that the Lombardic form actually comes from Proto-Germanic *ǥuđánaz. Wōdanaz or Wōđinaz is the reconstructed Proto-Germanic name of a god of Germanic paganism, known as Odin in Norse mythology, Wōden in Old English, Wodan or Wotan in Old High German and Godan in the Lombardic language. Godan was shortened to God over time and was adopted/retained by the Germanic peoples of the British isles as the name of their deity, in lieu of the Latin word Deus used by the Latin speaking Christian church, after conversion to Christianity.

During the complex christianization of the Germanic tribes of Europe, there were many linguistic influences upon the Christian missionaries. One example post downfall of the western Roman Empire are the missionaries from Rome led by Augustine of Canterbury. Augustine’s mission to the Saxons in southern Britain was conducted at a time when the city of Rome was a part of a Lombardic kingdom. The translated Bibles which they brought on their mission were greatly influenced by the Germanic tribes they were in contact with, chief among them being the Lombards and Franks. The translation for the word deus of the Latin Bible was influenced by the then current usage by the tribes for their highest deity, namely Wodan by Angles, Saxons, and Franks of north-central and western Europe, and Godan by the Lombards of south-central Europe around Rome. There are many instances where the name Godan and Wodan are contracted to God and Wod.[2] One instance is the wild hunt (a.k.a. Wodan’s wild hunt) where Wod is used.[3][4]

The earliest uses of the word God in Germanic writing is often cited to be in the Gothic Bible or Wulfila Bible, which is the Christian Bible as translated by Ulfilas into the Gothic language spoken by the Eastern Germanic, or Gothic, tribes. The oldest parts of the Gothic Bible, contained in the Codex Argenteus, are estimated to be from the fourth century. During the fourth century, the Goths were converted to Christianity, largely through the efforts of Bishop Ulfilas, who translated the Bible into the Gothic language in Nicopolis ad Istrum in today’s northern Bulgaria. The words guda and guþ were used for God in the Gothic Bible.

Influence of Christianity[edit]

God entered English when the language still had a system of grammatical gender. The word and its cognates were initially neuter but underwent transition when their speakers converted to Christianity, «as a means of distinguishing the personal God of the Christians from the impersonal divine powers acknowledged by pagans.»[5]: 15 However, traces of the neuter endured. While these words became syntactically masculine, so that determiners and adjectives connected to them took masculine endings, they sometimes remained morphologically neuter, which could be seen in their inflections: In the phrase, guþ meins, «my God,» from the Gothic Bible, for example, guþ inflects as if it were still a neuter because it lacks a final -s, but the possessive adjective meins takes the final -s that it would with other masculine nouns.[5]: 15

God and its cognates likely had a general, predominantly plural or collective sense prior to conversion to Christianity. After conversion, the word was commonly used in the singular to refer to the Christian deity, and also took on characteristics of a name.[5]: 15–16 [6]

Translations[edit]

The word god was used to represent Greek theos and Latin deus in Bible translations, first in the Gothic translation of the New Testament by Ulfilas. For the etymology of deus, see *dyēus.

Greek «θεός » (theos) means god in English. It is often connected with Greek «θέω» (theō), «run»,[7][8] and «θεωρέω» (theoreō), «to look at, to see, to observe»,[9][10] Latin feriae «holidays», fanum «temple», and also Armenian di-k` «gods». Alternative suggestions (e.g. by De Saussure) connect *dhu̯es- «smoke, spirit», attested in Baltic and Germanic words for «spook» and ultimately cognate with Latin fumus «smoke.» The earliest attested form of the word is the Mycenaean Greek te-o[11] (plural te-o-i[12]), written in Linear B syllabic script.

Capitalization[edit]

KJV of 1611 (Psalms 23:1,2): Occurrence of «LORD» (and «God» in the heading)

The development of English orthography was dominated by Christian texts. Capitalized, «God» was first used to refer to the Abrahamic God and may now signify any monotheistic conception of God, including the translations of the Arabic Allāh, Persian Khuda, Indic Ishvara and the Maasai Ngai.

In the English language, capitalization is used for names by which a god is known, including ‘God’. Consequently, its capitalized form is not used for multiple gods or when referring to the generic idea of a deity.[13][14]

Pronouns referring to a god are also often capitalized by adherents to a religion as an indication of reverence, and are traditionally in the masculine gender («He», «Him», «His» etc) unless specifically referring to a goddess.[15][16]

See also[edit]

- Anglo-Saxon paganism

- Allah (Arabic word)

- Bhagavan (Hindi word)

- El (deity) (Semitic word)

- Elohim

- Goddess

- Jumala (Finnish word)

- Khuda (Persian word)

- Names of God

- Tanri (Turkish word)

- Yahweh

- YHWH

References[edit]

- ^ Watkins, Calvert, ed., The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots, 2nd ed., Houghton Mifflin Co., 2000.

- ^ A New System of Geography, Or a General Description of the World by Daniel Fenning, Joseph Collyer 1765

- ^ See the chant in the Medieval and Early Modern folklore section of the Wikipedia entry for Wōden.

- ^ Northern Mythology, Comprising the Principal Popular Traditions and Superstitions of Scandinavia, North Germany and the Netherlands: Compiled from Original and Other Sources. In Three Volumes. North German and Netherlandish Popular Traditions and Superstitions, Volume 3, 1852

- ^ a b c Green, D. H. (1998). Language and History in the Early Germanic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521794237.

- ^ «god». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ θεωρέω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Dermot Moran, The Philosophy of John Scottus Eriugena: A Study of Idealism in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Palaeolexicon, Word study tool of ancient languages

- ^ Palaeolexicon, Word study tool of ancient languages

- ^ Webster’s New World Dictionary; «God n. ME < OE, akin to Ger gott, Goth guth, prob. < IE base * ĝhau-, to call out to, invoke > Sans havaté, (he) calls upon; 1. any of various beings conceived of as supernatural, immortal, and having special powers over the lives and affairs of people and the course of nature; deity, esp. a male deity: typically considered objects of worship; 2. an image that is worshiped; idol 3. a person or thing deified or excessively honored and admired; 4. [G-] in monotheistic religions, the creator and ruler of the universe, regarded as eternal, infinite, all-powerful, and all-knowing; Supreme Being; the Almighty»

- ^ Dictionary.com; «God /gɒd/ noun: 1. the one Supreme Being, the creator and ruler of the universe. 2. the Supreme Being considered with reference to a particular attribute. 3. (lowercase) one of several deities, esp. a male deity, presiding over some portion of worldly affairs. 4. (often lowercase) a supreme being according to some particular conception: the God of mercy. 5. Christian Science. the Supreme Being, understood as Life, Truth, Love, Mind, Soul, Spirit, Principle. 6. (lowercase) an image of a deity; an idol. 7. (lowercase) any deified person or object. 8. (often lowercase) Gods, Theater. 8a. the upper balcony in a theater. 8b. the spectators in this part of the balcony.»

- ^ The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge. The New York Times. 25 October 2011. ISBN 9780312643027. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

Pronoun references to a deity worshiped by people in the present are sometimes capitalized, although some writers use capitals only to prevent confusion: God helped Abraham carry out His law.

- ^ Alcoholic Thinking: language, culture, and belief in Alcoholics Anonymous. Greenwood Publishing Group. 1998. ISBN 9780275960490. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

Traditional biblical translations that always capitalize the word «God» and the pronouns, «He,» «Him,» and «His» in reference to God itself and the use of archaic forms such as «Thee,» «Thou,» and «Thy» are familiar.

External links[edit]

Look up God in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Use of guþ n the Gothic Bible.

- Use of guda n the Gothic Bible.

- Gothic language and its relation to other Germanic languages such as Anglish (English) and Saxon

r/etymology

Discussing the origins of words and phrases, in English or any other language.

Members

Online

Asked

6 years, 2 months ago

Viewed

233 times

Basically my question is the NT counterpart of this question: The name of God in ancient manuscripts

My question:

Which words are used for God in the oldest manuscripts of the New Testament?

asked Feb 3, 2017 at 14:29

5

The oldest manuscripts of the New Testament are all in Greek. Unlike Hebrew, Greek doesn’t have very many terms for God.

-

The Greek word for ‘God’ is θεός (Theos), which is used consistently throughout the New Testament.

-

The common Jewish reference ‘Lord’, frequently a substitute for God’s personal name יהוה (YHWH), is naturally rendered in Greek as κύριος (kurios), also meaning ‘lord’.

These two terms are the most common words used for God throughout the New Testament, as they are also prominent in the LXX (Septuagint) translation of the Old Testament.

Jesus commonly uses πατήρ (pater) in reference to God as ‘father’, but also uses Ἀββᾶ (Abba), which is a more intimate term common in Hebrew and Aramaic.

answered Feb 3, 2017 at 15:20

Steve can help♦Steve can help

5,4955 gold badges35 silver badges64 bronze badges

2

Bert wrote:

Iacobus wrote:

In the Greek text there are many cases of a singular anarthrous predicate nouns preceding the verb (e.g. Mark 6:49,11:32; John 4:19, 6:70, 8:44, 8:48, 9:17, 10:1, 10:13, 10:33, 12:6, 18:37). In these places, translators insert the indefinite article «a» before the predicate noun in order to bring out the quality or characteristic of the subject. Since the indefinite article is inserted before the predicate noun in such texts, with equal justification the indefinite article «a» is inserted before the anarthrous θεός in the predicate of John 1:1 to make it read «a god.» The Sacred Scriptures confirm the correctness of this rendering.Would you suggest translating ….ὁ θεος φῶς ἐστιν in 1 John 1:5 as ….God is a light?

Well, according to Philip B. Harner (previously quoted): «. . . anarthrous predicate preceding the verb, are PRIMARILY qualitative in meaning.» So, not always is there understood an «a». For further explanation, read the following, quoted from the 11/15/75 Watchtower (especially noting the fifth paragraph down from the question).

«Questions from Readers

• Does the rendering of John 1:1 in the New World Translation violate rules of Greek grammar or conflict with worship of only one God?

The New World Translation renders John 1:1 as follows: “In the beginning the Word was, and the Word was with God, and the Word was a god.” Some have objected to the translation “a god,” which appears in the final clause of this verse. They claim that the translators were wrong in putting an “a” in there before “god.” Is this really a mistranslation?

While the Greek language has no indefinite article corresponding to the English “a,” it does have a definite article ho, often rendered into English as “the.” For example, ho Khristos´, “the Christ,” ho Ky´ri·os, “the Lord,” ho The·os´, literally, “the God.”

Frequently, though, nouns occur in Greek without the article. Grammarians refer to these nouns as “anarthrous,” meaning “used without the article.” Interestingly, in the final part of John 1:1, the Greek word for “god,” the·os´, does not have the definite article ho before it. How do translators render such anarthrous Greek nouns into English?

Often they add the English indefinite article “a” to give proper sense to the passage. For example, in the concluding portion of John 9:17 the Greek text literally states, according to the interlinear literal translation by clergyman Alfred Marshall, D.Litt: “And he said[,] — A prophet he is.” There is no definite article before the Greek word for “prophet” here. The translator, therefore, rendered the word as “a prophet,” as do many other English translations.—Authorized Version, New American Standard Bible, also translations by Charles B. Williams and William F. Beck.

This does not mean, however, that every time an anarthrous noun occurs in the Greek text it should appear in English with the indefinite article. Translators render these nouns variously, at times even with a “the,” understanding them as definite, though the definite article is missing. At Matthew 27:40, for instance, several English Bible versions have the phrase “the Son of God,” though the Greek word for “son” is without the definite article.

What about John 1:1? Marshall’s interlinear translation of it reads: “In [the] beginning was the Word, and the Word was with — God, and God was the Word.” As noted above, no “the” appears before “God” in the final clause of this verse. The New World Bible Translation Committee chose to insert the indefinite article “a” there. This helps to distinguish “the Word,” Jesus Christ, as a god, or divine person with vast power, from the God whom he was “with,” Jehovah, the Almighty. Some persons familiar with Greek claim that in doing so the translators violated an important rule of Greek grammar. Why so?

The problem, they say, is word order. Back in 1933 Greek scholar E. C. Colwell published an article entitled “A Definite Rule for the Use of the Article in the Greek New Testament.” In it he wrote: “A definite predicate nominative has the article when it follows the verb; it does not have the article when it precedes the verb. . . . A predicate nominative which precedes the verb cannot be translated as an indefinite or a ‘qualitative’ noun solely because of the absence of the article; if the context suggests that the predicate is definite, it should be translated as a definite noun in spite of the absence of the article.”

At John 1:1 the anarthrous predicate noun the·os´ does precede the verb, the Greek word order being literally: “God [predicate] was [verb] the Word [subject].” Concerning this verse Colwell concluded: “The opening verse of John’s Gospel contains one of the many passages where this rule suggests the translation of a predicate as a definite noun.” Thus some scholars claim that the only really correct way to translate this clause is: “And the Word was God.”

Do these statements of Colwell prove that “a god” is a mistranslation at John 1:1? Perhaps you noticed this scholar’s wording that an anarthrous predicate noun that precedes the verb should be understood as definite “if the context suggests” that. Further along in his argument Colwell stressed that the predicate is indefinite in this position “only when the context demands it.” Nowhere did he state that all anarthrous predicate nouns that precede the verb in Greek are definite nouns. Not any inviolable rule of grammar, but context must guide the translator in such cases.

The Greek text of the Christian Scriptures has many examples of this type of predicate noun where other translators into English have added the indefinite article “a.” Consider, for example, Marshall’s interlinear translation of the following verses: “Says to him the woman: Sir, I perceive that a prophet [predicate] art [verb] thou [subject].” (John 4:19) “Said therefore to him—Pilate: Not really a king [predicate] art [verb] thou [subject]? Answered—Jesus: Thou sayest that a king [predicate] I am [verb, with subject included].”—John 18:37.

Did you notice the expressions “a prophet,” “a king” (twice)? These are anarthrous predicate nouns that precede the verb in Greek. But the translator rendered them with the indefinite article “a.” There are numerous examples of this in English versions of the Bible. For further illustration consider the following from the Gospel of John in The New English Bible: “A devil” (6:70); “a slave” (8:34); “a murderer . . . a liar” (8:44); “a thief” (10:1); “a hireling” (10:13); “a relation” (18:26).

Alfred Marshall explains why he used the indefinite article in his interlinear translation of all the verses mentioned in the two previous paragraphs, and in many more: “The use of it in translation is a matter of individual judgement. . . . We have inserted ‘a’ or ‘an’ as a matter of course where it seems called for.” Of course, neither Colwell (as noted above) nor Marshall felt that an “a” before “god” at John 1:1 was called for. But this was not because of any inflexible rule of grammar. It was “individual judgement,” which scholars and translators have a right to express. The New World Bible Translation Committee expressed a different judgment in this place by the translation “a god.”

Certain scholars have pointed out that anarthrous predicate nouns that precede the verb in Greek may have a qualitative significance. That is, they may describe the nature or status of the subject. Thus some translators render John 1:1: “The Logos was divine,” (Moffatt); “the Word was divine,” (Goodspeed); “the nature of the Word was the same as the nature of God,” (Barclay); “the Word was with God and shared his nature,” (The Translator’s New Testament).

Does the idea that Jesus Christ is “a god” conflict with the Scriptural teaching that there is only one God? (1 Cor. 8:5, 6) Not at all. At times the Hebrew Scriptures employ the term for God, ’elo·him´, with reference to mighty creatures. At Psalm 8:5, for example, we read: “You also proceeded to make him [man] a little less than godlike ones.” (Hebrew, ’elohim´; “a god,” New English Bible, Jerusalem Bible) The Greek Septuagint Version renders ?elo·him´ here as “angels.” The Jewish translators of this version saw no conflict with monotheism in applying the term for God to created spirit persons. (Compare Hebrews 2:7, 9.) Similarly, Jews of the first century C.E. found no conflict with their belief in one God at Psalm 82, though verses 1 and 6 of this psalm utilize the word ’elo·him´ (the·oi´, plural of the·os´, Septuagint) with reference to human judges.—Compare John 10:34-36.»»

Did you know that in Greek, the original language of the New Testament, two different Greek words are used to refer to the word of God? One is logos, and the other is rhema.

Understanding the meaning of these two Greek words can help us know and experience God in a deeper way. That’s why we’re taking some time in this post to discuss logos and rhema and their importance to our Christian lives.

The more commonly known of these two Greek words is logos. In the New Testament, logos is used to refer to the constant, written word, which is recorded in the Bible. How incredible it is that we human beings can have God’s written word in our hands!

When we read the written word, we can learn about God and know His ways, His salvation, and His plan for mankind. Without the logos, we would have no way to know God’s purpose, or our place in that purpose. We would be left to wonder or guess what His intention is. But we have to thank God for giving us the Bible, which communicates to us who He is and what He desires.

Knowing about God objectively is certainly a wonderful thing, but we can go further to know God on a personal level and experience Him subjectively. This is where rhema comes in.

The Greek word rhema

The lesser-known of these two Greek words is rhema, which is used to refer to the instant, personal speaking of God.

Our God isn’t silent; He’s a speaking God. His written word is a record of His speaking. But that’s not all. He continues to speak today, and He wants to speak directly to us.

It’s by the rhema word that we can know God subjectively, in our personal experience. Now let’s take a closer look at how we can receive this rhema from God.

Logos plus rhema

Both logos and rhema are crucial to our Christian life. God uses His logos Word to speak His rhema word to us. And God’s living, instant speaking always corresponds with and never contradicts His written Word.

So the more we read the written Word, even storing it up in us by memorizing and musing over it, the more God can speak instant words to us. His instant words in any given situation guide us and turn us to Him when we take heed to them.

Let’s look at how this could happen. For example, let’s say you’re at work or school and something happens that makes you very upset. The more you think about it, the more bothered you are. As you let all your thoughts about it swirl around in your mind, you begin to feel spiritually deadened. All of a sudden, Romans 8:6, a verse you had read before, pops into your head: “The mind set on the flesh is death, but the mind set on the spirit is life and peace.”

Immediately you realize, “No wonder I’m so dead! I’ve been setting my mind on my flesh. I need to turn back to the Lord to set my mind on Him.” So you begin to pray, “Lord, I turn back to You. I set my mind on You in my spirit right now. Thank You, Lord, when my mind is set on my spirit, it’s life and peace!”

As you turn to the Lord in your spirit, you’re saved from being consumed by your negative thoughts, and you’re ushered into enjoying life and peace from God.

How did all this happen? The Lord used the constant, written word (logos) you’d previously read and memorized to speak an instant and personal word to you (rhema) in your particular situation. The Lord’s instant speaking strengthened you to turn to Him and supplied you right where you were.

The functions of the rhema word

The rhema word does more than help us in particular situations. It also imparts life into us and washes us so we can grow in the divine life and be inwardly transformed. By imparting life into us and washing us, the rhema word works out God’s purpose in us.

Let’s look at two verses where we can see this.

1. Rhema imparts life to us

John 6:63 says:

“It is the Spirit who gives life; the flesh profits nothing; the words which I have spoken to you are spirit and are life.”

Note 3 in the New Testament Recovery Version on the words clearly explains the difference between logos and rhema and how the Lord’s words impart the divine life to us:

“The Greek word for words, here and in v. 68, is rhema, which denotes the instant and present spoken word. It differs from logos (used for Word in 1:1), which denotes the constant word. Here the words follows the Spirit. The Spirit is living and real, yet He is very mysterious, intangible, and difficult for people to apprehend; the words, however, are substantial. First, the Lord indicated that for giving life He would become the Spirit. Then He said that the words He speaks are spirit and life. This shows that His spoken words are the embodiment of the Spirit of life. He is now the life-giving Spirit in resurrection, and the Spirit is embodied in His words. When we receive His words by exercising our spirit, we get the Spirit, who is life.”

The Spirit gives us life through His rhema words, which the Lord said are spirit and life. So how can we receive life from the Spirit? The key for us to receive the Lord’s rhema words is that we must exercise our spirit when we come to the Bible.

The best way to exercise our spirit is by prayer. By praying with the Word, we contact the Spirit in the Word. Then the words on the page are no longer simply black and white letters; they become rhema, and are spirit and life to us. This is how the Word of God feeds us and supplies us with life for our growth in Christ.

2. Rhema washes us

Ephesians 5:26 says:

“That He might sanctify her, cleansing her by the washing of the water in the word.”

Washing in this verse doesn’t refer to the washing away of sins by the blood of Jesus. Instead, it’s the washing of the water in the word, or rhema. Note 4 in the New Testament Recovery Version on word explains:

“The Greek word denotes an instant word. The indwelling Christ as the life-giving Spirit is always speaking an instant, present, living word to metabolically cleanse away the old and replace it with the new, causing an inward transformation. The cleansing by the washing of the water of life is in the word of Christ. This indicates that in the word of Christ there is the water of life.”

To be washed from our sins, we need the redeeming blood of Christ. But we need to realize we must also be washed inwardly from the old things of our natural life. This happens by the washing of the water of the living, instant, present rhema word. Through that cleansing away of the old and replacing with the new, we’re inwardly changed, or transformed.

We need to receive rhema

So we need to open ourselves to the Lord dwelling in our spirit who speaks His instant word to us. By receiving this instant word, life is imparted into us, and we’re washed inwardly.

Going back to the example we used before, the verse suddenly popping into your head wasn’t a coincidence; it was the Lord speaking to you. When you receive that word, you’re not only helped to turn back to the Lord, but life is imparted into you, and inwardly you’re washed from losing your temper.

Certainly God wants us to read, study, and memorize His written word. But even more, He wants us to receive His instant, living speaking. Let’s all regularly read and pray with the logos so the Lord can speak rhema words to impart life into us and wash us for the fulfillment of His marvelous purpose and plan.

If you don’t have a New Testament of your own and you live in the US, you can order a free copy of the New Testament Recovery Version here.

Subscribe to receive the latest posts