A museum ( mew-ZEE-əm; plural museums or, rarely, musea) is a building or institution that cares for and displays a collection of artifacts and other objects of artistic, cultural, historical, or scientific importance.[1] Many public museums make these items available for public viewing through displays that may be permanent or temporary.[2] The largest museums are located in major cities throughout the world, while thousands of local museums exist in smaller cities, towns, and rural areas. Museums have varying aims, ranging from the conservation and documentation of their collection, serving researchers and specialists, to catering to the general public. The goal of serving researchers is not only scientific, but intended to serve the general public.

There are many types of museums, including art museums, natural history museums, science museums, local history museums, and children’s museums. According to the International Council of Museums (ICOM), there are more than 55,000 museums in 202 countries.[3]

Etymology[edit]

The English «museum» comes from the Latin word, and is pluralized as «museums» (or rarely, «musea»). It is originally from the Ancient Greek Μουσεῖον (Mouseion), which denotes a place or temple dedicated to the muses (the patron divinities in Greek mythology of the arts), and hence was a building set apart for study and the arts,[4] especially the Musaeum (institute) for philosophy and research at Alexandria, built under Ptolemy I Soter about 280 BC.[5]

Purpose[edit]

The purpose of modern museums is to collect, preserve, interpret, and display objects of artistic, cultural, or scientific significance for the study and education of the public. From a visitor or community perspective, this purpose can also depend on one’s point of view. A trip to a local history museum or large city art museum can be an entertaining and enlightening way to spend the day. To city leaders, an active museum community can be seen as a gauge of the cultural or economic health of a city, and a way to increase the sophistication of its inhabitants. To a museum professional, a museum might be seen as a way to educate the public about the museum’s mission, such as civil rights or environmentalism. Museums are, above all, storehouses of knowledge.[citation needed] In 1829, James Smithson’s bequest, that would fund the Smithsonian Institution, stated he wanted to establish an institution «for the increase and diffusion of knowledge».[6]

Museums of natural history in the late 19th century exemplified the scientific desire for classification and for interpretations of the world. Gathering all examples for each field of knowledge for research and display was the purpose. As American colleges grew in the 19th century, they developed their own natural history collections for the use of their students. By the last quarter of the 19th century, scientific research in universities was shifting toward biological research on a cellular level, and cutting-edge research moved from museums to university laboratories.[7] While many large museums, such as the Smithsonian Institution, are still respected as research centers, research is no longer a main purpose of most museums. While there is an ongoing debate about the purposes of interpretation of a museum’s collection, there has been a consistent mission to protect and preserve cultural artifacts for future generations. Much care, expertise, and expense is invested in preservation efforts to retard decomposition in aging documents, artifacts, artworks, and buildings. All museums display objects that are important to a culture. As historian Steven Conn writes, «To see the thing itself, with one’s own eyes and in a public place, surrounded by other people having some version of the same experience, can be enchanting.»[8]

Museum purposes vary from institution to institution. Some favor education over conservation, or vice versa. For example, in the 1970s, the Canada Science and Technology Museum favored education over preservation of their objects. They displayed objects as well as their functions. One exhibit featured a historical printing press that a staff member used for visitors to create museum memorabilia.[9] Some museums seek to reach a wide audience, such as a national or state museum, while others have specific audiences, like the LDS Church History Museum or local history organizations. Generally speaking, museums collect objects of significance that comply with their mission statement for conservation and display. Apart from questions of provenance and conservation, museums take into consideration the former use and status of an object. Religious or holy objects, for instance, are handled according to cultural rules. Jewish objects that contain the name of God may not be discarded, but need to be buried.[10]

Although most museums do not allow physical contact with the associated artifacts, there are some that are interactive and encourage a more hands-on approach. In 2009, Hampton Court Palace, a palace of Henry VIII, in England opened the council room to the general public to create an interactive environment for visitors. Rather than allowing visitors to handle 500-year-old objects, however, the museum created replicas, as well as replica costumes. The daily activities, historic clothing, and even temperature changes immerse the visitor in an impression of what Tudor life may have been.[11]

Definitions[edit]

Major museum professional organizations from around the world offer some definitions as to what a museum is and their purpose. Common themes in all the definitions are public good and care, preservation, and interpretation of collections.

The International Council of Museums’ current definition of a museum (adopted in 2022): «A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing.»[12]

The Canadian Museums Association’s definition: «A museum is a non-profit, permanent establishment, that does not exist primarily for the purpose of conducting temporary exhibitions and that is open to the public during regular hours and administered in the public interest for the purpose of conserving, preserving, studying, interpreting, assembling and exhibiting to the public for the instruction and enjoyment of the public, objects and specimens or educational and cultural value including artistic, scientific, historical and technological material.»[13]

The United Kingdom’s Museums Association’s definition: «Museums enable people to explore collections for inspiration, learning and enjoyment. They are institutions that collect, safeguard and make accessible artifacts and specimens, which they hold in trust for society.»

While the American Alliance of Museums does not have a definition their list of accreditation criteria to participate in their Accreditation Program states a museum must: «Be a legally organized nonprofit institution or part of a nonprofit organization or government entity; Be essentially educational in nature; Have a formally stated and approved mission; Use and interpret objects or a site for the public presentation of regularly scheduled programs and exhibits; Have a formal and appropriate program of documentation, care, and use of collections or objects; Carry out the above functions primarily at a physical facility or site; Have been open to the public for at least two years; Be open to the public at least 1,000 hours a year; Have accessioned 80 percent of its permanent collection; Have at least one paid professional staff with museum knowledge and experience; Have a full-time director to whom authority is delegated for day-to-day operations; Have the financial resources sufficient to operate effectively; Demonstrate that it meets the Core Standards for Museums; Successfully complete the Core Documents Verification Program» [14]

Additionally a there is a legal definition of museum in United States legislation in the authorizing the establishment of the Institute of Museum and Library Services: «Museum means a public, tribal, or private nonprofit institution which is organized on a permanent basis for essentially educational, cultural heritage, or aesthetic purposes and which, using a professional staff: Owns or uses tangible objects, either animate or inanimate; Cares for these objects; and Exhibits them to the general public on a regular basis.» (Museum Services Act 1976) [15]

History[edit]

Ancient[edit]

One of the oldest museums known is Ennigaldi-Nanna’s museum, built by Princess Ennigaldi in modern Iraq at the end of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The site dates from c. 530 BC, and contained artifacts from earlier Mesopotamian civilizations. Notably, a clay drum label—written in three languages—was found at the site, referencing the history and discovery of a museum item.[16][17]

Ancient Greeks and Romans collected and displayed art and objects but perceived museums differently from modern day views. In the classical period the museums were the temples and their precincts which housed collections of votive offerings. Paintings and sculptures were displayed in gardens, forums, theaters, and bathhouses.[18] In the ancient past there was little differentiation between libraries and museums with both occupying the building and were frequently connected to a temple or royal palace. The Museum of Alexandria is believed to be one of the earliest museums in the world. While it connected to the Library of Alexandria it is not clear if the museum was in a different building from the library or was part of the library complex. While little was known about the museum it was an inspiration for museums during the early Renaissance period.[19] The royal palaces also functioned as a kind of museum outfitted with art and objects from conquered territories and gifts from ambassadors from other kingdoms allowing the ruler to display the amassed collections to guests and to visiting dignitaries.[20]

Also in Alexandria from the time of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (r. 285-246 BCE), was the first zoological park. At first used by Philadelphus in an attempt to domesticate African elephants for use in war, the elephants were also used for show along with a menagerie of other animals specimens including hartebeests, ostriches, zebras, leopards, giraffes, rhinoceros, and pythons.[19][21]

Early[edit]

The old Ashmolean Museum building

Early museums began as the private collections of wealthy individuals, families or institutions of art and rare or curious natural objects and artifacts. These were often displayed in so-called «wonder rooms» or cabinets of curiosities. These contemporary museums first emerged in western Europe, then spread into other parts of the world.[22]

Public access to these museums was often possible for the «respectable», especially to private art collections, but at the whim of the owner and his staff. One way that elite men during this time period gained a higher social status in the world of elites was by becoming a collector of these curious objects and displaying them. Many of the items in these collections were new discoveries and these collectors or naturalists, since many of these people held interest in natural sciences, were eager to obtain them. By putting their collections in a museum and on display, they not only got to show their fantastic finds but also used the museum as a way to sort and «manage the empirical explosion of materials that wider dissemination of ancient texts, increased travel, voyages of discovery, and more systematic forms of communication and exchange had produced».[23]

One of these naturalists and collectors was Ulisse Aldrovandi, whose collection policy of gathering as many objects and facts about them was «encyclopedic» in nature, reminiscent of that of Pliny, the Roman philosopher and naturalist.[24] The idea was to consume and collect as much knowledge as possible, to put everything they collected and everything they knew in these displays. In time, however, museum philosophy would change and the encyclopedic nature of information that was so enjoyed by Aldrovandi and his cohorts would be dismissed as well as «the museums that contained this knowledge». The 18th-century scholars of the Age of Enlightenment saw their ideas of the museum as superior and based their natural history museums on «organization and taxonomy» rather than displaying everything in any order after the style of Aldrovandi.[25]

The first «public» museums were often accessible only by the middle and upper classes. It could be difficult to gain entrance. When the British Museum opened to the public in 1759, it was a concern that large crowds could damage the artifacts. Prospective visitors to the British Museum had to apply in writing for admission, and small groups were allowed into the galleries each day.[26] The British Museum became increasingly popular during the 19th century, amongst all age groups and social classes who visited the British Museum, especially on public holidays.[27]

The Ashmolean Museum, however, founded in 1677 from the personal collection of Elias Ashmole, was set up in the University of Oxford to be open to the public and is considered by some to be the first modern public museum.[28] The collection included that of Elias Ashmole which he had collected himself, including objects he had acquired from the gardeners, travellers and collectors John Tradescant the elder and his son of the same name. The collection included antique coins, books, engravings, geological specimens, and zoological specimens—one of which was the stuffed body of the last dodo ever seen in Europe; but by 1755 the stuffed dodo was so moth-eaten that it was destroyed, except for its head and one claw. The museum opened on 24 May 1683, with naturalist Robert Plot as the first keeper. The first building, which became known as the Old Ashmolean, is sometimes attributed to Sir Christopher Wren or Thomas Wood.[29]

The Louvre museum in 1853

In France, the first public museum was the Louvre Museum in Paris,[30] opened in 1793 during the French Revolution, which enabled for the first time free access to the former French royal collections for people of all stations and status. The fabulous art treasures collected by the French monarchy over centuries were accessible to the public three days each «décade» (the 10-day unit which had replaced the week in the French Republican Calendar). The Conservatoire du muséum national des Arts (National Museum of Arts’s Conservatory) was charged with organizing the Louvre as a national public museum and the centerpiece of a planned national museum system. As Napoléon I conquered the great cities of Europe, confiscating art objects as he went, the collections grew and the organizational task became more and more complicated. After Napoleon was defeated in 1815, many of the treasures he had amassed were gradually returned to their owners (and many were not). His plan was never fully realized, but his concept of a museum as an agent of nationalistic fervor had a profound influence throughout Europe.

Chinese and Japanese visitors to Europe were fascinated by the museums they saw there, but had cultural difficulties in grasping their purpose and finding an equivalent Chinese or Japanese term for them. Chinese visitors in the early 19th century named these museums based on what they contained, so defined them as «bone amassing buildings» or «courtyards of treasures» or «painting pavilions» or «curio stores» or «halls of military feats» or «gardens of everything». Japan first encountered Western museum institutions when it participated in Europe’s World’s Fairs in the 1860s. The British Museum was described by one of their delegates as a ‘hakubutsukan’, a ‘house of extensive things’ – this would eventually become accepted as the equivalent word for ‘museum’ in Japan and China.[31]

Modern[edit]

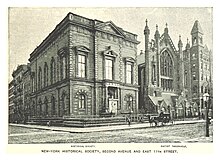

New-York Historical Society. Building erected in 1855-57 and served as the Society’s home until 1908

American museums eventually joined European museums as the world’s leading centers for the production of new knowledge in their fields of interest. A period of intense museum building, in both an intellectual and physical sense was realized in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (this is often called «The Museum Period» or «The Museum Age»). While many American museums, both natural history museums and art museums alike, were founded with the intention of focusing on the scientific discoveries and artistic developments in North America, many moved to emulate their European counterparts in certain ways (including the development of Classical collections from ancient Egypt, Greece, Mesopotamia, and Rome). Drawing on Michel Foucault’s concept of liberal government, Tony Bennett has suggested the development of more modern 19th-century museums was part of new strategies by Western governments to produce a citizenry that, rather than be directed by coercive or external forces, monitored and regulated its own conduct. To incorporate the masses in this strategy, the private space of museums that previously had been restricted and socially exclusive were made public. As such, objects and artifacts, particularly those related to high culture, became instruments for these «new tasks of social management».[32] Universities became the primary centers for innovative research in the United States well before the start of World War II. Nevertheless, museums to this day contribute new knowledge to their fields and continue to build collections that are useful for both research and display.[33]

Exhibiting human remains of Native Americans.

The late twentieth century witnessed intense debate concerning the repatriation of religious, ethnic, and cultural artifacts housed in museum collections. In the United States, several Native American tribes and advocacy groups have lobbied extensively for the repatriation of sacred objects and the reburial of human remains.[34] In 1990, Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which required federal agencies and federally funded institutions to repatriate Native American «cultural items» to culturally affiliate tribes and groups.[35] Similarly, many European museum collections often contain objects and cultural artifacts acquired through imperialism and colonization. Some historians and scholars have criticized the British Museum for its possession of rare antiquities from Egypt, Greece, and the Middle East.[36]

Management[edit]

Honours board listing Directors of a Museum

The roles associated with the management of a museum largely depend on the size of the institution.[37] Together, the Board and the Director establish a system of governance that is guided by policies that set standards for the institution. Documents that set these standards include an institutional or strategic plan, institutional code of ethics, bylaws, and collections policy. The American Alliance of Museums (AAM) has also formulated a series of standards and best practices that help guide the management of museums.

- Board of Trustees or Board of directors – The board governs the museum and is responsible for ensuring the museum is financially and ethically sound. They set standards and policies for the museum. Board members are often involved in fundraising aspects of the museum and represent the institution.[38] Some museum use the terms «directors» and «trustees» interchangeably but both are different legal instruments. A board of directors governs a nonprofit corporation, a board of trustees is responsible for governing a charitable trust, foundation, or endowment.[39] In the case of small museums and all volunteer museums, a board may be more hands-on in the day-to-day operations of the museum.[40]

- Director- The director is the face of the museum to the professional and public community. They communicate closely with the board to guide and govern the museum. They work with the staff to ensure the museum runs smoothly. According to museum professionals Hugh H. Genoways and Lynne M. Ireland, «Administration of the organization requires skill in conflict management, interpersonal relations, budget management and monitoring, and staff supervision and evaluation. Managers must also set legal and ethical standards and maintain involvement in the museum profession.»[38]

Curator and exhibit designer dress a mannequin for an exhibit.

Restoration of a gilded mirror by Conservator.

Various positions within the museum carry out the policies established by the Board and the Director. All museum employees should work together toward the museum’s institutional goal. Here is a list of positions commonly found at museums:

- Curator – Curators are the intellectual drivers behind exhibits. They research the museum’s collection and topic of focus, develop exhibition themes, and publish their research aimed at either a public or academic audience. Larger museums have curators in a variety of areas. For example, The Henry Ford has a Curator of Transportation, a Curator of Public Life, a Curator of Decorative Arts, etc. Many art museums have curators dedicated to specific historic periods and geographic regions, such as American art and modern or contemporary art.[citation needed]

- Collections Management – Collections managers are primarily responsible for the hands-on care, movement, and storage of objects. They are responsible for the accessibility of collections and collections policy.

- Registrar – Registrars are the primary record keepers of the collection. They insure that objects are properly accessioned, documented, insured, and, when appropriate, loaned. Ethical and legal issues related to the collection are dealt with by registrars. Along with collections managers, they uphold the museum’s collections policy.[citation needed]

- Educator – Museum educators are responsible for educating museum audiences. Their duties can include designing tours and public programs for children and adults, teacher training, developing classroom and continuing education resources, community outreach, and volunteer management.[41] Educators not only work with the public, but also collaborate with other museum staff on exhibition and program development to ensure that exhibits are audience-friendly.

- Exhibit Designer – Exhibit designers are in charge of the layout and physical installation of exhibits. They create a conceptual design and then bring it to fruition in the physical space.[citation needed]

- Conservator – Conservators focus on object restoration. More than preserving the object in its present state, they seek to stabilize and repair artifacts to the condition of an earlier era.[42]

Other positions commonly found at museums include: building operator, public programming staff, photographer, librarian, archivist, groundskeeper, volunteer coordinator, preparator, security staff, development officer, membership officer, business officer, gift shop manager, public relations staff, and graphic designer.

At smaller museums, staff members often fulfill multiple roles. Some of these positions are excluded entirely or may be carried out by a contractor when necessary.

Protection[edit]

The cultural property stored in museums is threatened in many countries by natural disaster, war, terrorist attacks or other emergencies. To this end, an internationally important aspect is a strong bundling of existing resources and the networking of existing specialist competencies in order to prevent any loss or damage to cultural property or to keep damage as low as possible. International partner for museums is UNESCO and Blue Shield International in accordance with the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property from 1954 and its 2nd Protocol from 1999. For legal reasons, there are many international collaborations between museums, and the local Blue Shield organizations.[43][44]

Blue Shield has conducted extensive missions to protect museums and cultural assets in armed conflict, such as 2011 in Egypt and Libya, 2013 in Syria and 2014 in Mali and Iraq. During these operations, the looting of the collection is to be prevented in particular.[45]

Planning[edit]

The design of museums has evolved throughout history. However, museum planning involves planning the actual mission of the museum along with planning the space that the collection of the museum will be housed in. Intentional museum planning has its beginnings with the museum founder and librarian John Cotton Dana. Dana detailed the process of founding the Newark Museum in a series of books in the early 20th century so that other museum founders could plan their museums. Dana suggested that potential founders of museums should form a committee first, and reach out to the community for input as to what the museum should supply or do for the community.[46] According to Dana, museums should be planned according to community’s needs:

«The new museum … does not build on an educational superstition. It examines its community’s life first, and then straightway bends its energies to supplying some the material which that community needs, and to making that material’s presence widely known, and to presenting it in such a way as to secure it for the maximum of use and the maximum efficiency of that use.»[47]

The way that museums are planned and designed vary according to what collections they house, but overall, they adhere to planning a space that is easily accessed by the public and easily displays the chosen artifacts. These elements of planning have their roots with John Cotton Dana, who was perturbed at the historical placement of museums outside of cities, and in areas that were not easily accessed by the public, in gloomy European style buildings.[48]

Questions of accessibility continue to the present day. Many museums strive to make their buildings, programming, ideas, and collections more publicly accessible than in the past. Not every museum is participating in this trend, but that seems to be the trajectory of museums in the twenty-first century with its emphasis on inclusiveness. One pioneering way museums are attempting to make their collections more accessible is with open storage. Most of a museum’s collection is typically locked away in a secure location to be preserved, but the result is most people never get to see the vast majority of collections. The Brooklyn Museum’s Luce Center for American Art practices this open storage where the public can view items not on display, albeit with minimal interpretation. The practice of open storage is all part of an ongoing debate in the museum field of the role objects play and how accessible they should be.[49]

In terms of modern museums, interpretive museums, as opposed to art museums, have missions reflecting curatorial guidance through the subject matter which now include content in the form of images, audio and visual effects, and interactive exhibits. Museum creation begins with a museum plan, created through a museum planning process. The process involves identifying the museum’s vision and the resources, organization and experiences needed to realize this vision. A feasibility study, analysis of comparable facilities, and an interpretive plan are all developed as part of the museum planning process.

Some museum experiences have very few or no artifacts and do not necessarily call themselves museums, and their mission reflects this; the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles and the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, being notable examples where there are few artifacts, but strong, memorable stories are told or information is interpreted. In contrast, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. uses many artifacts in their memorable exhibitions.

Museums are laid out in a specific way for a specific reason and each person who enters the doors of a museum will see its collection completely differently to the person behind them- this is what makes museums fascinating because they are represented differently to each individual.[50]: 9–10

Financial uses[edit]

In recent years, some cities have turned to museums as an avenue for economic development or rejuvenation. This is particularly true in the case of postindustrial cities.[51] Examples of museums fulfilling these economic roles exist around the world. For example, the spectacular Guggenheim Bilbao was built in Bilbao, Spain in a move by the Basque regional government to revitalize the dilapidated old port area of that city. The Basque government agreed to pay $100 million for the construction of the museum, a price tag that caused many Bilbaoans to protest against the project.[52] Nonetheless, the gamble has appeared to pay off financially for the city, with over 1.1 million people visiting the museum in 2015. Key to this is the large demographic of foreign visitors to the museum, with 63% of the visitors residing outside of Spain and thus feeding foreign investment straight into Bilbao.[53] A similar project to that undertaken in Bilbao was also built on the disused shipyards of Belfast, Northern Ireland. Titanic Belfast was built for the same price as the Guggenheim Bilbao (and which was incidentally built by the same architect, Frank Gehry) in time for the 100th anniversary of the Belfast-built ship’s maiden voyage in 2012. Initially expecting modest visitor numbers of 425,000 annually, first year visitor numbers reached over 800,000, with almost 60% coming from outside Northern Ireland.[54] In the United States, similar projects include the 81, 000 square foot Taubman Museum of Art in Roanoke, Virginia and The Broad Museum in Los Angeles.

Museums being used as a cultural economic driver by city and local governments has proven to be controversial among museum activists and local populations alike. Public protests have occurred in numerous cities which have tried to employ museums in this way. While most subside if a museum is successful, as happened in Bilbao, others continue especially if a museum struggles to attract visitors. The Taubman Museum of Art is an example of a museum which cost a lot (eventually $66 million) but attained little success, and continues to have a low endowment for its size.[55] Some museum activists also see this method of museum use as a deeply flawed model for such institutions. Steven Conn, one such museum proponent, believes that «to ask museums to solve our political and economic problems is to set them up for inevitable failure and to set us (the visitor) up for inevitable disappointment.»[51]

Funding[edit]

Officials blamed lack of funding resulting in a fire gutting Brazil’s Museu Nacional.[56]

Museums are facing funding shortages. Funding for museums comes from four major categories, and as of 2009 the breakdown for the United States is as follows: Government support (at all levels) 24.4%, private (charitable) giving 36.5%, earned income 27.6%, and investment income 11.5%.[57] Government funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, the largest museum funder in the United States, decreased by 19.586 million between 2011 and 2015, adjusted for inflation.[58][59] The average spent per visitor in an art museum in 2016 was $8 between admissions, store and restaurant, where the average expense per visitor was $55.[60] Corporations, which fall into the private giving category, can be a good source of funding to make up the funding gap. The amount corporations currently give to museums accounts for just 5% of total funding.[61] Corporate giving to the arts, however, was set to increase by 3.3% in 2017.[62]

Exhibition design[edit]

Painting arranged in groupings ‘Salon Style’

Most mid-size and large museums employ exhibit design staff for graphic and environmental design projects, including exhibitions. In addition to traditional 2-D and 3-D designers[63] and architects, these staff departments may include audio-visual specialists, software designers, audience research, evaluation specialists, writers, editors, and preparators or art handlers. These staff specialists may also be charged with supervising contract design or production services. The exhibit design process builds on the interpretive plan for an exhibit, determining the most effective, engaging and appropriate methods of communicating a message or telling a story. The process will often mirror the architectural process or schedule, moving from conceptual plan, through schematic design, design development, contract document, fabrication, and installation. Museums of all sizes may also contract the outside services of exhibit fabrication businesses.[64]

Left: «Cabinet of curiosities» style of exhibit, c.1890. Right: Contemporary history exhibit, 2016.

Some museum scholars have even begun to question whether museums truly need artifacts at all. Historian Steven Conn provocatively asks this question, suggesting that there are fewer objects in all museums now, as they have been progressively replaced by interactive technology.[65] As educational programming has grown in museums, mass collections of objects have receded in importance. This is not necessarily a negative development. Dorothy Canfield Fisher observed that the reduction in objects has pushed museums to grow from institutions that artlessly showcased their many artifacts (in the style of early cabinets of curiosity) to instead «thinning out» the objects presented «for a general view of any given subject or period, and to put the rest away in archive-storage-rooms, where they could be consulted by students, the only people who really needed to see them».[66] This phenomenon of disappearing objects is especially present in science museums like the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, which have a high visitorship of school-aged children who may benefit more from hands-on interactive technology than reading a label beside an artifact.[67]

Types[edit]

There is no definitive standard as to the set types of museums. Additionally, the museum landscape has become so varied, that it may not be sufficient to use traditional categories to comprehend fully the vast variety existing throughout the world. However, it may be useful to categorize museums in different ways under multiple perspectives. Museums can vary based on size, from large institutions, to very small institutions focusing on specific subjects, such as a specific location, a notable person, or a given period of time. Museums also can be based on the main source of funding: central or federal government, provinces, regions, universities; towns and communities; other subsidised; nonsubsidised and private.[68]

It may sometimes be useful to distinguish between diachronic museums — those that interpret the way in which its subject matter has developed and evolved through time (examples: Lower East Side Tenement Museum and Diachronic Museum of Larissa), and synchronic museums — those that interpret the way in which its subject matter exists at one point in time (examples: The Anne Frank House and Colonial Williamsburg). According to University of Florida’s Professor Eric Kilgerman, «While a museum in which a particular narrative unfolds within its halls is diachronic, those museums that limit their space to a single experience are called synchronic.»[69]

In her book Civilizing the Museum, author Elaine Heumann Gurian proposes that there are five categories of museums based on intention not content: object centered, narrative, client centered, community centered, and national.[70]

Museums can also be categorized into major groups by the type of collections they display, to include: fine arts, applied arts, craft, archaeology, anthropology and ethnology, biography, history, cultural history, science, technology, children’s museums, natural history, botanical and zoological gardens. Within these categories, many museums specialize further, e.g. museums of modern art, folk art, local history, military history, aviation history, philately, agriculture, or geology. The size of a museum’s collection typically determines the museum’s size, whereas its collection reflects the type of museum it is. Many museums normally display a «permanent collection» of important selected objects in its area of specialization, and may periodically display «special collections» on a temporary basis.[citation needed]

Major types[edit]

The following is a list to give an idea of the major museum types. While comprehensive it is not a definitive list.

- Agricultural

- Architecture

- Archaeological

- Art

- Design

- Biographical

- Children’s

- Community

- Encyclopedic

- Folk

- Historic house

- Historic site

- Living history

- Local

- Maritime

- Medical

- Memorial

- Natural history

- Open-air

- Science

- Virtual

Legal framework[edit]

Public vs. private[edit]

Private museums are organized by individuals and managed by a board and museum officers, but public museums are created and managed by federal, state, or local governments. A government can charter a museum through legislative action but the museum can still be private as it is not part of the government. The distinction regulates the ownership and legal accountability for the care of the collections.[39][71]

Non-profit vs. for-profit[edit]

Nonprofit means that an organization is classified as a charitable corporation and is exempt from paying most taxes and the money the organization earns is invested in the organization itself. Money made by a private, for-profit museum is paid to the museum’s owners or shareholders.

The nonprofit museum has a fiduciary responsibility in regards to the public, in essence the museum holds its collections and administers it for the benefit of the public. Collections of for-profit museums are legally corporate assets the museum administers for the benefit of the owners or shareholders.[39][71]

Run by trusts vs. corporations[edit]

A trust is a legal instrument where trustees manage the trust’s assets for the benefit of the museum following the specific wishes of the donor. This provides tax benefits for the donor, and also allows the donor to have control over how assets are distributed.

Corporations are legal entities and may acquire property in a way similar to how an individual can own property. Museums under incorporation are usually organized by a community or group of individuals. While a board of director’s loyalty is to the corporation, a board of trustee’s loyalty has to be loyal to the intention of the trust. The ramification is that a trust is far less flexible than a corporation.[72][73]

Current challenges[edit]

Decolonization[edit]

Moai figure at the British Museum

During the beginning of the 21st century, a growing global movement for the decolonization of museums has arisen.[74] Proponents of this movement argue that ‘museums are a box of things’ and do not represent complete stories; instead they show biased narratives based on ideologies, in which certain stories are intentionally disregarded.[50]: 9–18 Through this, people are encouraging others to consider this missing perspective, when looking at museum collections, as every object viewed in such environments was placed by an individual to represent a certain viewpoint, be it historical or cultural.[50]: 9–18

The 2018 report on the restitution of African cultural heritage[75] is a prominent example regarding the decolonization of museums and other collections in France and the claims of African countries to regain artifacts illegally taken from their original cultural settings.

Since 1868, several monolithic human figures known as Moai have been removed from Easter Island and put in display in major Western museums such as the National Museum of Natural History, the British Museum, the Louvre and the Royal Museums of Art and History. Several demands have been made by Easter Island residents for the return of the Moai.[76] The figures are seen as ancestors and family or the soul by the Rapa Nui and hold deep cultural value to their people.[77] Other examples include the Gweagal Shield, thought to be a very significant shield taken from Botany Bay in April 1770[78] or the Parthenon marble sculptures, which were taken from Greece by Lord Elgin in 1805.[79] Successive Greek governments have unsuccessfully petitioned for the return of the Parthenon marbles.[79] Another example among many others is the so-called Montezuma’s headdress in the Museum of Ethnology, Vienna, which is a source of dispute between Austria and Mexico.[80]

Laura Van Broekhoven, director of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, United Kingdom, stated in 2020 that «ethnographic museums should redress their coloniality. They should be a pluriverse that shows the rich diversity of ways of being and knowing, not centering whiteness as the only way of being. Museums ought to allow for everyone to understand each other better.»[81]

Labor issues and unionization[edit]

Workers rallying at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Background

The past few years has seen a unionizing movement. US museums workers have initiated dialogs about labor and collective organizing in the cultural sector. In 2019 the workers in multiple museums voted to form unions with more protesting to press for a fair contract and against unfair labor practices.[82] During that year over 3,000 cultural workers anonymously started to share their salaries online through a pay transparency spreadsheet.[83]

The Marciano Art Foundation, a museum established by co-founders of Guess clothing, Maurice Marciano and Paul Marciano closed indefinitely in November 2019 after workers attempted to unionize.[84][85] The Marciano Foundation released a statement a month later that the closure was permanent.[86]

In the country of Georgia 40 employees were fired May 2022 as part of a restructuring. The newly formed union, the Georgian Trade Union of Science, Education, and Culture Workers said in a statement they said the employees were fired illegally and the reorganization was «carried out by the employer in an untransparent and maladministered manner» and that the organization will «definitely fight to the end to protect the rights of employees.» Fired senior curator Maia Pataridze said the new management mentioned her social media posts criticizing the government.[87][88] Among those fired was union chair, Nikoloz Tsikaridze, a senior researcher and archaeologist who associated the discharging of himself and other museum staff was for forming a union, and said that Thea Tsulukiani, the Georgia Minister of Culture had ‘punished’ them.[89][90]

- History

In the United States, labor unrest within the arts and cultural sector go back at least nearly a century to 1933 when a New York based collective of artists eventually known as the Artist’s Union used collective bargaining for state relief for unemployed artists.[91]

In 1971 administrative staff at New York’s Museum of Modern Art formed the organization «Professional and Staff Association of the Museum of Modern Art» (PASTA), the first union of professional employees, as opposed to maintenance and service people, at a privately‐financed museum. The contract negotiated would provide a wage increase, protection against termination without cause, and direct access to trustees and policy-making processes at the museum. While there was some interest from workers at other museums at the time, for the next fifty years there was little change in museums adding union representation of their professional employees.[83][92]

Sustainability and climate change[edit]

Increasingly museums have been responded to the ongoing climate crisis through enacting sustainable museum practices, and exhibitions highlighting the issues surrounding climate change and the Anthropocene.

See also[edit]

Museums portal

- Audio tour

- Cell phone tour

- Computer Interchange of Museum Information

- Exhibition history

- Ennigaldi-Nanna’s museum, world’s first museum

- International Council of Museums

- International Museum Day (18 May)

- List of museums

- List of largest art museums

- List of most-visited museums

- List of most visited art museums

- List of most-visited museums by region

- .museum

- Museum education

- Museum fatigue

- Museum label

- Museum shop

- Public memory

- Science tourism

- Types of museums

- Virtual Library museums pages

References[edit]

- ^ See Wiktionary definition, Collins English dictionary definition, Oxford English Dictionary definition

- ^ Edward Porter Alexander, Mary Alexander; Alexander, Mary; Alexander, Edward Porter (September 2007). Museums in motion: an introduction to the history and functions of museums. Rowman & Littlefield, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7591-0509-6. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ «How many museums are there in the world?». ICOM. 31 May 2018. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- ^ Findlen, Paula (1989). «The Museum: its classical etymology and renaissance genealogy». Journal of the History of Collections. 1 (1): 59–78. doi:10.1093/jhc/1.1.59.

- ^ Dunn, Jimmy. «Ptolemy I Soter, The First King of Ancient Egypt’s Ptolemaic Dynasty». Tour Egypt. Archived from the original on 4 October 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- ^ «James Smithson Society». Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Steven Conn, «Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876–1926», 1998, The University of Chicago Press, 65.

- ^ Steven Conn, «Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876–1926», 1998, The University of Chicago Press, 262.

- ^ Babian, Sharon, CSTM: A History of the Canada Science and Technology Museum, pp. 42–45

- ^ «Holy Museology». Jewish Museum of Switzerland. 31 May 2022.

- ^ Lipschomb, Suzannah, «Historical Authenticity and Interpretive Strategy at Hampton Court Palace,» The Public Historian 32, no.3, August 2010, pp. 98–119.

- ^ «ICOM approves a new museum definition». International Council of Museums. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ «About Museums — Association of Manitoba Museums». www.museumsmanitoba.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ «Eligibility». American Alliance of Museums. 25 January 2018. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ «2 CFR § 3187.3 — Definition of a museum». LII / Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Wilkens, Alasdair (25 May 2011). «The story behind the world’s oldest museum, built by a Babylonian princess 2,500 years ago». io9. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ Manssour, Y. M.; El-Daly, H. M.; Morsi, N. K. «The Historical Evolution of Museums Architecture» (PDF): 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ van Buren, E. Douglas (1922). «Museums and Raree Shows in Antiquity». Folklore. 33 (4): 337–53. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1922.9720240. JSTOR 1256361. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b Genoways, Hugh; Andrei, Mary Anne, eds. (2008). Museum Origins: Readings in early museum history and philosophy. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-1-59874-197-1.

- ^ «Museums in the Ancient Mediterranean». World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Hubbell, H. M. (1935). «Ptolemy’s Zoo». The Classical Journal. 31 (2): 68–76. JSTOR 3290815. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Chang Wan-Chen, A cross-cultural perspective on musealization: the museum’s reception by China and Japan in the second half of the nineteenth century in Museum and Society, vol 10, 2012.

- ^ Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1994),3.

- ^ Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1994),62.

- ^ Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1994),393–397.

- ^ The British Museum, » Admission Ticket to the British Museum» https://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/archives/a/admission_ticket_to_the_britis.aspx Archived 13 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 4/3/14.

- ^ «History of the British Museum». British Museum. Archived from the original on 12 April 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ Swann, Marjorie (2001), Curiosities and Texts: The Culture of Collecting in Early Modern England, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

- ^ H. E. Salter and Mary D. Lobel (editors) Victoria County History A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3 1954 Pages 47–49 Archived 8 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «History of Louvre». History of Louvre. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ Chang Wan-Chen, A cross-cultural perspective on musealization: the museum’s reception by China and Japan in the second half of the nineteenth century in Museum and Society, vol. 10, 2012.

- ^ Bennett, Tony (1995). The Birth of the Museum. New York: Routledge Press. pp. 6, 8, 24. ISBN 0-415-05388-9.

- ^ «Museum». Encyclopedica Britannica. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Gulliford, Andrew (1992). «Curation and Repatriation of Sacred and Tribal Artifacts». The Public Historian. 14 (3): 25. doi:10.2307/3378225. JSTOR 3378225.

- ^ «The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA)». National Park Service. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Duthie, Emily (2011). «The British Museum: An Imperial Museum in a Post-Imperial World». Public History Review. 18: 12–25. doi:10.5130/phrj.v18i0.1523.

- ^ American Association of Museums, «The Accreditation Commission’s Expectations Regarding Governance.» p. 1. Archived 19 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Hugh H. Genoways and Lynne M. Ireland, Museum Administration: An Introduction, (Lanham: AltaMira, 2003), 3.

- ^ a b c Latham, Kiersten F.; Simmons, John E. (2014). Foundations of Museum Studies: Evolving Systems of Knowledge Illustrated Edition. Libraries Unlimited. p. 9. ISBN 978-1610692823.

- ^ Pierce, Dennis (November–December 2018). «The Quest for Excellence: Small museums really do have the resources to pursue accreditation» (PDF). Museum. American Alliance of Museum: 16–26. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Roberts, Lisa C. (1997). From Knowledge to Narrative: Educators and the Changing Museum. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 2.

- ^ University of Rochester, «Museum Job Descriptions». Archived 5 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cf. e.g. Marilyn E. Phelan: Museum Law: A Guide for Officers, Directors, and Counsel. 2014, p. 419 ff.

- ^ «ICOM and the International Committee of the Blue Shield». ICOM. Archived from the original on 23 March 2020.

- ^ Peter Stone Inquiry: Monuments Men. In: Apollo – The International Art Magazine. 2 February 2015; Mehroz Baig: When War Destroys Identity. In: Worldpost. 12 May 2014; Fabian von Posser: Welterbe-Stätten zerbombt, Kulturschätze verhökert. (German) In: Die Welt. 5 November 2013.

- ^ Dana, John Cotton. The New Museum (Woodstock, VT: The Elm Tree Press, 1917), 25.

- ^ Dana, John Cotton. The New Museum (Woodstock, VT: The Elm Tree Press, 1917), 32.

- ^ Dana, John Cotton. The Gloom of the Museum. (Woodstock, VT: The Elm Tree Press, 1917), 12.

- ^ «Turning Museums Inside-Out with Beautiful Visible Storage». Atlas Obscura. 24 September 2014. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ a b c Procter, Alice (2020). The whole Picture: the colonial story of the art in our museums and why we need to talk about it. England: Cassel. ISBN 978-1-78840-221-7.

- ^ a b Conn, Steven (2010). Do Museums Still Need Objects?. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 17.

- ^ Riding, Alan (24 June 1997). «A Gleaming New Guggenheim for Grimy Bilbao». The New York Times. p. C9.

- ^ «Guggenheim Bilbao Annual Report 2015» (PDF). Guggenheim Bilbao. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ Smyth, Jamie (16 June 2013). «Northern Ireland Focus: Titanic Success Raises Hopes For Tourism». Financial Times.

- ^ Wallis, David (20 March 2014). «Start-Up Success Isn’t Enough to Found a Museum». The New York Times. p. F6.

- ^ «Brazil museum fire: Funding cuts blamed as icon is gutted». BBC News. 3 September 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Bell, Ford W. “How Are Museums Supported Nationally in the U.S.?” Archived 10 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine Embassy of the United States of America, 2012.. Accessed 26 March 2017.

- ^ “National Endowment for the Arts 2011 Annual Report.” Archived 10 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine National Endowment for the Arts, 2012. Accessed 26 February 2017.

- ^ “National Endowment for the Arts 2015 Annual Report.” Archived 11 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine National Endowment for the Arts, 2016.. Accessed 26 February 2017.

- ^ Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) Archived 19 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine, “Art Museums by the Numbers 2016.” AAMD.org,. Accessed 26 February 2017.

- ^ Stubbs, Ryan and Henry Clapp. “Public Funding for the Arts: 2015 Update.” Archived 26 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine Grantmakers in the Arts, GIA Reader, vol. 26, no. 3, Fall 2015.. Accessed 26 February 2017.

- ^ «Sponsorship Spending on the Arts to Grow 3.3 Percent in 2017». ESP Sponsorship Report. ESP Properties, LLC. 13 February 2017. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Barbieri, Loris; Fuoco, Fabrizio; Bruno, Fabio; Muzzupappa, Maurizio (2022). «Exhibit supports for sandstone artifacts designed through topology optimization and additive manufacturing techniques». Journal of Cultural Heritage. 55: 329–338. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2022.04.008. S2CID 248439991.

- ^ Taheri, Babak; Jafari, Aliakbar; O’Gorman, Kevin (2014). «Keeping your audience: Presenting a visitor engagement scale» (PDF). Tourism Management. 42: 321–329. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2013.12.011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ Conn, Steven (2010). Do Museums Still Need Objects?. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 26.

- ^ Canfield Fisher, Dorothy (1927). Why Stop Learning?. New York: Harcourt. pp. 250–251.

- ^ Conn, Steven (2010). Do Museums Still Need Objects?. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 265.

- ^ Ginsburgh, Victor; Mairesse, François (1997). «Defining a Museum: Suggestions for an Alternative Approach». Museum Management and Curatorship. Routledge. 16: 15–33. doi:10.1016/S0260-4779(97)00003-4.

- ^ Kilgerman, Eric. Sites of the Uncanny: Paul Celan, Specularity and the Visual Arts Archived 8 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, p. 255 (2007).

- ^ Heumann Gurian, Elaine (17 May 2006). The Collected Writings of Elaine Heumann Gurian. Taylor & Francis. pp. 48–56.

- ^ a b Malaro, Marie C.; DeAngelis, Ildiko (2012). A Legal Primer on Managing Museum Collections, Third Edition. Smithsonian Books. p. 8. ISBN 978-1588343222.

- ^ Latham, Kiersten F.; Simmons, John E. (2014). Foundations of Museum Studies: Evolving Systems of Knowledge Illustrated Edition. Libraries Unlimited. p. 11. ISBN 978-1610692823.

- ^ Malaro, Marie C.; DeAngelis, Ildiko (2012). A Legal Primer on Managing Museum Collections, Third Edition. Smithsonian Books. pp. 6–9. ISBN 978-1588343222.

- ^ Brennan, Bridget (10 May 2019). «The battle at the British Museum for a ‘stolen’ shield that could tell the story of Captain Cook’s landing». ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Felwine Sarr, Bénédicte Savoy: «Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle». Paris 2018; «The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics» (Download French original and English version, pdf, http://restitutionreport2018.com/ Archived 15 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bartlett, John (16 November 2018). «‘Moai are family’: Easter Island people to head to London to request statue back». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Bartlett, John (16 November 2018). «‘Moai are family’: Easter Island people to head to London to request statue back». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Nicholas (2018). «A Case of Identity: The Artefacts of the 1770 Kamay (Botany Bay) Encounter». Australian Historical Studies. 49:1: 4–27. doi:10.1080/1031461X.2017.1414862. S2CID 149069484. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2020 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ a b «How the Parthenon Lost Its Marbles». History Magazine. 28 March 2017. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ «Mexico and Austria in dispute over Aztec headdress». prehist.org. 22 November 2012. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ «Keynote Speaker: Laura Van Broekhoven». decolonizingmuseums.com. 16 December 2020. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ Wagley, Catherine (25 November 2019). «Museum Workers Across the Country Are Unionizing. Here’s What’s Driving a Movement That’s Been Years in the Making». Artnet News. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ a b Small, Zachary (21 February 2022). «U.S. Museums See Rise in Unions Even as Labor Movement Slumps». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ Miranda, Carolina A. (6 November 2019). «Marciano Art Foundation announces it won’t reopen in wake of layoffs following union drive». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ MIRANDA, CAROLINA A. (8 November 2019). «What’s next for nonprofit museums after the closing of the Marciano Art Foundation?». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «MOCA will voluntarily recognize new employee union; Marciano closure is permanent». Los Angeles Times. 7 December 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ Dafoe, Taylor (2 June 2022). «State-Run Museums in Georgia Abruptly Fired 40 Employees, Allegedly in Retribution for Forming a Union». Artnet News. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ «Georgia Museums Respond to Unionization Push by Brazenly Firing Dozens of Employees». Widewalls. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ «Georgian culture minister accused of purging critics from National Museum». OC Media. 26 May 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ «Union vows to fight «unlawful mass dismissal» of Georgian National Museum employees». Agenda.ge. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ Monroe, Gerald M. (1972). «The Artists Union of New York». Art Journal. 32 (1): 17–20. doi:10.2307/775601. ISSN 0004-3249. JSTOR 775601.

- ^ Glueck, Grace (26 September 1971). «MOMA Gets a Taste of PASTA». The New York Times. pp. Section D, Page 24. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

Further reading[edit]

- Aronsson, Peter., and Gabriella Elgenius. National Museums and Nation-Building in Europe 1750-2010 : Mobilization and Legitimacy, Continuity and Change. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2015.

- Bennett, Tony (1995). The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05387-7. OCLC 30624669.

- Conn, Steven (1998). Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876–1926. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-11493-7.

- Cuno, James (2013). Museums Matter: In Praise of the Encyclopedic Museum. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-10091-3.

- Findlen, Paula (1996). Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20508-1.

- Marotta, Antonello (2010). Contemporary Milan. ISBN 978-88-572-0258-7.

- Murtagh, William J. (2005). Keeping Time: The History and Theory of Preservation in America. New York: Sterling Publishing Company. ISBN 0-471-47377-4.

- Rentzhog, Sten (2007). Open air museums: The history and future of a visionary idea. Stockholm and Östersund: Carlssons Förlag / Jamtli. ISBN 978-91-7948-208-4

- Simon, Nina K. (2010). The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz: Museums 2.0

- van Uffelen, Chris (2010). Museumsarchitektur (in German). Potsdam: Ullmann. ISBN 978-3-8331-6033-2. – also available in English: Contemporary Museums – Architecture History Collections. Braun Publishing. 2010. ISBN 978-3-03768-067-4.

- Yerkovich, Sally (2016). A Practical Guide to Museum Ethics. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-3164-1.

- «The Museum and Museum Specialists: Problems of Professional Education, Proceedings of the International Conference, 14–15 November 2014» (PDF). St. Petersburg: The State Hermitage Publishers. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

External links[edit]

Media related to Museums at Wikimedia Commons

- International Council of Museums

- Museums of the World

- VLmp directory of museums

- Museums at Curlie

Europe

It was during the second half of the 19th century that museums began to proliferate in Europe; civic pride and the free education movement were among the causes of this development. About 100 opened in Britain in the 15 years before 1887; some 50 museums were established in Germany in the five years from 1876 to 1880; and, with the opening of the magnificent Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna in 1891, most of the imperial Habsburg collections were finally housed and displayed in one place. This was also a period of innovation. The Liverpool Museums in England, for example, began circulating specimens to schools for educational purposes; panoramas and habitat groups were used to facilitate interpretation. As first gas lighting and then electric lighting became available, museums extended their hours into the evenings to provide service to those unable to visit during the day.

South America

The increase in the number of museums was not, however, a peculiarity of Europe or North America. In South America particularly, new museums were founded both in the capital cities and in the provinces. Some of these were provided by universities, as in the case of the Geological Museum in Lima, Peru (1891), or the Geographical and Geological Museum at São Paulo, Brazil (1895). Others were created by provincial bodies: the regional museums at Córdoba (1887) and Gualeguaychu (1898), both in Argentina, and at Ouro Prêto, Brazil (1876); the Hualpen Museum in Chile (1882); and the Municipal Museum and Library at Guayaquil, Ecuador (1862). New specialist national museums also appeared in certain countries, while at Tigre, in Argentina, a maritime museum was founded in 1892. Early in the following century, memorial museums were created, including those dedicated to Bartolomé Mitre, a former president of Argentina, in Buenos Aires (1906) and to Simón Bolívar in Caracas, Venezuela (1911).

Asia

By this time the Indian Museum, in Kolkata, and what is now the National Museum, in Jakarta, were well-established institutions in Asia, but a number of new museums were appearing as well. In Japan a museum to encourage industry and the development of natural resources was opened in 1872; this provided the basis for the present-day Tokyo National Museum and National Science Museum (also in Tokyo). Although some learned-society museums existed in China in the late 19th century, the first museum in the strict sense of the word was the Nantong Museum in Jiangsu province, founded in 1905, to be followed within a decade by the National Museum of Chinese History in Beijing (the museum merged with the Museum of the Chinese Revolution in 2003 to create the National Museum of China) and the Beijiang Museum in Tianjin (now Tianjin Natural History Museum). The collections established in the Grand Palace at Bangkok in 1874 eventually became the Bangkok National Museum. The National Museum of Sri Lanka, in Colombo, opened to the public in 1877; the Sarawak Museum (now in Malaysia) opened in 1891; and the Peshawar Museum, in Pakistan, opened in 1907.

Africa

In central and southern Africa, museums were founded early in the 20th century. Zimbabwe’s national museums at Bulawayo and Harare (then known as Salisbury) were founded in 1901, the Uganda Museum originated in 1908 from collections assembled by the British District Commissioners, and the National Museum of Kenya (now part of the National Museums of Kenya) in Nairobi was commenced by the East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society in 1909. Mozambique’s first museum, the Alvaro de Castro Natural History Museum in Maputo, was founded in 1913. Meanwhile in North Africa the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (founded 1835) had been relocated to its new building in 1902, and certain of the collections had been transferred to form two new institutions: the Museum of Islamic Art (1903) and the Coptic Museum (1908). In South Africa there was steady museum development in a number of the provinces—for example, in Grahamstown (1837), Port Elizabeth (1856), Bloemfontein (1877), Durban (1887), Pretoria (1893), and Pietermaritzburg (1903).

The history of museums is a long one. The existence of Homo Sapiens is linked with art and art is a way of linking people with other people. In addition, the desire to create and share what is created is closely affiliated with the desire to collect. The creator, the collector, the viewer, and the artwork are all parts of one equation, and the museum is the blackboard on which it is written.

Museums today are diverse but we can all roughly understand what makes a museum: exhibiting, collecting, preserving, and researching humanity’s cultural heritage. With this in mind, we are ready to explore the history of museums. Our narration will start with prehistoric cave paintings, go through historical, scientific, and art museums, reach the 21st century, and end with a prediction for the future.

Before The History Of Museums: Prehistory

It is possible to trace the first point in the history of museums back to the prehistoric period. Cave paintings such as in Altamira involved basic elements of exhibiting art.

This public display of artistic creation and its symbolism could have had a variety of functions. Above all, however, it could have created a sense of commonness amongst the community sharing the space. This common visual art would only be one aspect of a common culture and heritage of these early civilizations. Of course, this is a hypothetical scenario.

Classical Antiquity

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

The English word ‘museum’ has its origins in ancient Greece. The Greek word (Μουσεῖον) referred to sites devoted to the cult of the nine Muses (patron deities of the arts). With time, the word came to describe a place devoted to the study of art and finally gained its current meaning.

In Classical antiquity, art was displayed everywhere; from public temples and buildings to houses of wealthy individuals. During the 5th century BCE on the Propylaia of the Athenian Acropolis one could visit the pinacotheke; a public exhibition of paintings on various religious themes.

Furthermore, Panhellenic sanctuaries like the ones in Delphi and Olympia were filled with art of every form. In many ways, these sanctuaries were the ancient predecessors of the museum. Visitors from all parts of the Greek world visited and experienced the exhibited art. Much like national museums, these spaces played a major part in fashioning a common cultural and religious identity while promoting ideas of Greekness.

The museum-like spaces of the Greek antiquity did not seek to rationally categorize and exhibit their collections. Besides, these were not systematic collections in the modern sense. For these reasons, they were not museums in the modern use of the word.

At the time, art was inseparable from religion as well as daily life. In contrast, the modern museum tends to do the exact opposite. It tends to ‘musealize’ objects, i.e. take them out of their original context and see them as isolated from their historical conditions. In short, a modern museum is a space where an object becomes an artwork by simply being exhibited.

Aristotle And The Lyceum

In the 340s BCE, the Greek philosopher traveled to the island of Lesbos with his disciple Theophrastus. There, they collected, studied, and classified botanical specimens setting the fundaments of empirical methodology. In this way, the concept of a systematic collection – a prerequisite for the modern museum – was created. For this reason, many argue that the history of museums begins with Aristotle.

Aristotle’s philosophical school/community of philosophers was the Lyceum. The school, located in Athens, contained a mouseion. This was the first place where a collection was linked with research in the form of the study of biology. The mouseion also included a library indicating its close relationship with learning.

Mouseion Of Alexandria

A direct successor to Lyceum’s mouseion was the Mouseion of Alexandria. Ptolemy Soter founded it as a research institute around 280 BCE. Like the Lyceum, it was a community of scholars both academic and religious, organized around a shrine to the Muses.

An organic part of the mouseion was the library of Alexandria, mostly known for its enormous collection of books; the largest in antiquity. It is possible that the Alexandrians also collected other objects (botanical and zoological specimens).

Museums In Ancient Rome

The expansionism that turned Rome from a city-state into a vast empire brought a great influx of art. Looted statues and paintings from every corner of the empire found their place as decoration in Roman public architecture.

The Greek sculptures, now found everywhere in the city of Rome, created an unprecedented effect. In the words of art-historian Jerome Pollitt, “Rome became a museum of Greek art.”

This was the first-time art was used for purely decorative/aesthetic purposes out of its religious context. This was the beginning of the division between religion and art.

Next to the public display of art for power projection, there was also a private form of exhibiting and collecting. Wealthy members of the Roman elite collected artworks and displayed them in their Pinakothecae (picture galleries). These were rooms filled with paintings and/or painted walls. Although they were inside private residencies, they were publicly accessible. Through a Pinakothece, the owner hoped to accumulate prestige and gain the esteem of his fellow citizens.

Art Renewal In The Renaissance

During the Renaissance, scholars became fascinated with classical antiquity. With the renewed interest in the philosophy of Aristotle arrived a familiarization with empirical methodology. At first, this entailed the collection of specimens from nature and their study. Very quickly it evolved into collections of objects from all around Europe.

The most outstanding Renaissance collection of antiquities was that of Cosimo de’ Medici in 15th century Florence. Cosimo’s descendants kept growing the collection until it was bequeathed to the public in the 18th century.

Nevertheless, in 1582, a floor in Uffizi palace – filled with paintings of the Medici family – opened to the public.

The Cabinet Of Curiosities

The age of the explorers and the opening of the new world to Europeans broadened the scope of collections. Collectors – mainly amateurs and scholars – stored their acquisitions in cabinets, drawers, cases, and others. As time passed, every new collection was more systematic and ordered than the previous one.

These collections became known under different names throughout Europe. In English, they were most commonly called Cabinets of Curiosities.

By the 17th century, the Cabinets of Curiosities would also be called museums. The term was first used to describe the collection of Lorenzo de’ Medici during the 15th century. This was the conscious choice of scholars deeply invested in the study of classical antiquity and the Alexandrine tradition.

Both artificalia (man-made objects) and naturalia (natural made objects/specimens) were included in the cabinets with little distinction. The artificalia (usually coins, medals, and other small objects) were used to facilitate antiquarian studies. The naturalia were used for the promotion of “natural sciences.” Many times Curiosities Cabinets attempted to create a replica of reality in miniature.

Parallel to the Cabinets of Curiosities were the gallerias. There, collectors exhibited collections of sculpture and/or painting. Although the cabinet of curiosities was a means towards accumulating prestige, the gallerias were more important in that regard. Especially Greek and Roman sculpture was considered of higher importance and was an asset for every ruler. Naturally, the galleria was also called as museo.

Enlightenment And 18th Century Museums

The history of museums may not begin with the Enlightenment but it is a product of the Age of Reason.

John Tradescant (1570-1638), a British naturalist, had created a large collection of artifacts and natural specimens. After facing financial hardships, Tradescant sold his collection to Elias Ashmole who had already a considerable collection of his own. Finally, Ashmole (1617-1692) donated his collection to the University of Oxford in 1675.

This collection became the nucleus of the Ashmolean Museum, the first university museum. The Ashmolean included a laboratory and its main goals were the preservation of the collection and the promotion of natural sciences and research.

The Ashmolean was also the first public museum because it was publicly accessible. Visitors paid an entrance fee and entered the museum one by one, where they were shown through the collection by a keeper. Unlike a Cabinet of Curiosities, the Ashmolean laid claim to a rational form of collecting and organizing its collection. Thus, it was a real museum in the modern sense.

During 18th century Europe, a series of private collections began opening to the public and taking the shape of a museum. The British Museum was established in 1753, the Museum Fridericianum in Kassel opened in 1779, while the Uffizi in Florence became available to the public in 1743. European capitals and monarchs were now competing in a race to establish their museums. By the first decades of the 19th century, the museum was a well-established institution.

Museums at this point remained closely related to scholarly research and learning. However, they were mostly tools in a game of power between Europe’s monarchs. A great collection was an effective way of projecting power. It was also a way of declaring the cultural supremacy of a state as embodied by its monarch.

The Louvre: The Royal Collection

Perhaps the most important event in the history of museums occurred in 18th century France.

In 1793, the Revolutionary government nationalized the King’s property and declared The Louvre palace a public institution under the name Museum Francais. It had already become an art museum of the royal art collection when King Luis XIV moved to the Versailles.

For the first time, the royal collection was available for all to see. The people of Paris entered and roamed in the first truly public museum in history. At the same time, the Louvre became the first truly national museum. The museum did not belong to any king or any member of the aristocracy. As the National Committee declared, this was the property of the people of France; a monument to the glory of the French nation and its history.

Worth noting is that the Louvre was open to the people and free of charge, in contrast to its preceding museums. As part of the government’s education program, the Louvre aimed at ‘civilizing’ the citizens. This was not a new tendency. The museums discussed in the previous section had similar goals. However, the Louvre was the first museum to express this ideal so effectively.

Museums And Nationalism

It is no coincidence that the modern museum appears at the same time with imperialism and nationalism. The national museum had the power to convert the treasures and luxuries of the monarchy into the treasured heritage of the nation. After The Louvre, every nation aspiring to be respected sought to represent itself through a national museum. Thus, museums became part of a nation’s struggle to understand, shape, and promote itself.

In general, the museum was only one of the institutions (e.g. universities) that the modern state saw as important for the civilizing process of its body of citizens. The idea was that by looking at ‘good’ and ‘virtuous’ art, the citizens would also become virtuous and good. From that point forward, the museum would be an institution able to shape the value system of the public. What is more, state art museums would become proof of a state’s political virtue and/or superiority.

Art Museums and the US

While large public museums were taking over Europe, things were different on the other side of the Atlantic. Museums in America were not publicly owned (except for the Smithsonian founded in 1846).