“Aardvark.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/aardvark.

Contents

- 1 What is the first word in an English dictionary?

- 2 What is the last word in the dictionary?

- 3 What’s the 2nd word in the dictionary?

- 4 What is the first word in the U section of the dictionary?

- 5 What word takes 3 hours to say?

- 6 What word has all 26 letters in it?

- 7 What is the oldest swear word?

- 8 What is a word that begins with Z?

- 9 What is the shortest word in the world?

- 10 What does Second mean on TikTok?

- 11 What’s the longest word in the dictionary?

- 12 What is the third word?

- 13 What word starts with E?

- 14 What is G word?

- 15 What is the T word?

- 16 Is there a word with 1000 letters?

- 17 Is there a word without a vowel?

- 18 Is Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis the longest word?

- 19 What is the 27th letter in the alphabet?

- 20 What start with E and ends with E?

The aardvark is not mythical, like the phoenix, since it really exists, but it has its own urban myth. Ask anyone which word comes first in an English dictionary, and they will assuredly answer “aardvark“.

What is the last word in the dictionary?

‘Zyzzyva’ – a tropical beetle – has become the new last word in the Oxford English Dictionary with the latest quarterly update which added over 1,200 new words, phrases and senses. Until now, the last alphabetic entry in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) was zythum, a kind of malt beer brewed in ancient Egypt.

What’s the 2nd word in the dictionary?

The second word in the English dictionary is the word consisting of the double letters A A. The word AA is a basaltic lava that forms rough, jagged masses with a light frothy texture.

What is the first word in the U section of the dictionary?

Dictionary Scavenger Hunt

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Where does the Handbook of Style begin? | 999 |

| What is the first word in the r section of the dictionary? | R |

| What is the last word in the u section of the dictionary and what does it mean? | uvula:the small fleshy fingerlike part hanging down from the back part of the roof of the mouth. |

What word takes 3 hours to say?

protein titin

Note the ellipses. All told, the full chemical name for the human protein titin is 189,819 letters, and takes about three-and-a-half hours to pronounce. The problem with including chemical names is that there’s essentially no limit to how long they can be.

What word has all 26 letters in it?

An English pangram is a sentence that contains all 26 letters of the English alphabet. The most well known English pangram is probably “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog”. My favorite pangram is “Amazingly few discotheques provide jukeboxes.”

What is the oldest swear word?

Fart

Fart, as it turns out, is one of the oldest rude words we have in the language: Its first record pops up in roughly 1250, meaning that if you were to travel 800 years back in time just to let one rip, everyone would at least be able to agree upon what that should be called.

What is a word that begins with Z?

- zags.

- zany.

- zaps.

- zarf.

- zeal.

- zebu.

- zeda.

- zeds.

What is the shortest word in the world?

Eunoia

Eunoia, at six letters long, is the shortest word in the English language that contains all five main vowels. Seven letter words with this property include adoulie, douleia, eucosia, eulogia, eunomia, eutopia, miaoued, moineau, sequoia, and suoidea. (The scientific name iouea is a genus of Cretaceous fossil sponges.)

What does Second mean on TikTok?

“Second Time Around” is also an audio on TikTok, though it’s only used on less than 100 posts so far. It’s from the song “Second Time Around” by Quinn XCII. The song talks about asking for another chance after making a mistake.

What’s the longest word in the dictionary?

pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis

The longest word in any of the major English language dictionaries is pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis, a word that refers to a lung disease contracted from the inhalation of very fine silica particles, specifically from a volcano; medically, it is the same as silicosis.

What is the third word?

Everyone knows what the third word means. What is the third word? The answer is “energy”. The riddle says that the word ends in the letters g-r-y; it says nothing about the order of the letters.

What word starts with E?

5 letter words that start with E

- eager.

- eagle.

- eagre.

- eared.

- earls.

- early.

- earns.

- earth.

What is G word?

(humorous) Any word beginning with g that is not normally taboo but is considered (often humorously) to be so in the given context.

What is the T word?

t-word (plural t-words) (humorous) tax or taxes, treated as if it were taboo. quotations ▼ (euphemistic) The word tranny, regarded as offensive and taboo.

Is there a word with 1000 letters?

pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis

It’s a technical word referring to the lung disease more commonly known as silicosis.

Is there a word without a vowel?

Words with no vowels. Cwm and crwth do not contain the letters a, e, i, o, u, or y, the usual vowels (that is, the usual symbols that stand for vowel sounds) in English.Shh, psst, and hmm do not have vowels, either vowel symbols or vowel sounds. There is some controversy whether they are in fact “words,” however.

Is Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis the longest word?

1 Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis (forty-five letters) is lung disease caused by the inhalation of silica or quartz dust.6 Incomprehensibilities set the record in the 1990s as the longest word “in common usage.” How many times have you used this twenty-one-letter term?

What is the 27th letter in the alphabet?

The ampersand often appeared as a character at the end of the Latin alphabet, as for example in Byrhtferð’s list of letters from 1011. Similarly, & was regarded as the 27th letter of the English alphabet, as taught to children in the US and elsewhere.

What start with E and ends with E?

Answer: The answer is ENVELOPE. It starts with E, ends with E and has only one letter in it, i.e, you can keep only one letter inside the envelope.

Everyone knows the word, but how many have ever seen the animal? The definition

medium-sized, nocturnal African mammal, Orycteropus afer, which has sparse hair, long ears, an elongated snout, strong burrowing limbs, and a thick tail, feeding solely on ants and termites

does not make the beast sound immediately prepossessing, yet some people find this Cyrano de Bergerac of the animal kingdom cute. (The wording of that Oxford English Dictionary definition could also suggest, somewhat surreally, that it is the critter’s tail which feeds solely on ants and termites).

The aardvark is not mythical, like the phoenix, since it really exists, but it has its own urban myth. Ask anyone which word comes first in an English dictionary, and they will assuredly answer “aardvark“. But it generally is not the first word in “the dictionary”.

And the first word in an English dictionary is…

That honour usually goes to the letter A, as in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). You might think a simple letter would be child’s play to define. In fact, the OED divides it into no fewer than 33 senses, including everyday meanings such as the musical note, and more technical ones such as A denoting a socio-economic grouping and A for Ångström.

Dozens of abbreviations follow before the next entry, the humble but indispensable indefinite article (aka “general determiner”) a. It is followed by numerous entries for a in different guises, such as in Bob Dylan’s “The times they are a-changin“, as a prefix (asexual), and as a Latin or Greek suffix (idea, data).

Finally, we strike gold with the first truly lexical entry. And it is? (A very muffled drumroll for) aa, meaning a stream or watercourse, last spotted in 1430 and marked as not only obsolete but rare. Several more curiosities, including some that may be useful for Scrabblists, intervene (aal, from Hindi, the Indian mulberry tree, aapa, from Urdu, meaning older sister) before we get back to our ant-eating, ground-digging mammal with its thirty-centimetre-long tongue.

Why “aardvark”?

South African Dutch, which became Afrikaans, is the language from which English borrowed aardvark, originally written as aardvarken. The aard- part is the Dutch word aarde, which means “earth” and comes from the same Germanic stock as the English word. (The connection between the two is easier to see in the medieval Dutch form of the word, which was ertha.) The -varken part means “pig”. And the animal is also called earth-hog and earth-pig in a loan translation.

Another sign of how English and Afrikaans are ultimately related can be seen in the word Apartheid. It meant literally “apart-ness”, and the -heid element matches the -hood of childhood, priesthood, and other “-hoods“.

Other Afrikaans words in World English

Afrikaans is an offshoot of Dutch, and is one of the most widely spoken of South Africa’s eleven official languages. Its gifts to World English include trek as a noun and verb, and commandeer. Commandeer is multiply borrowed, a bit like a parent’s car, in that it was borrowed from Afrikaans kommandeer, which borrowed it from Dutch commanderen, which borrowed it from French commander. Phew!

It rose to prominence in British English during the First Boer War of 1880-1881. It was originally used to mean “to force into military service”, as The Times reported on 5 February 1881:

The night previously the Boers had commandeered the natives…and compelled them to fight.

Its more metaphorical meaning of taking arbitrary possession of something came later:

The naïve claims put forward by the Boers to some special Providence—a process which a friendly German critic described as “commandeering the Almighty”.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, 1900.

Rather more colourful is scoff, the informal noun for food. It is from Afrikaans schoff, representing Dutch schoft “quarter of a day”, hence the four meals in a day. The OED’s first quotation comes from the 1846 Swell’s Night Guide; or, a peep through The Great Metropolis, a rather louche guide for the man about town in search of interesting nightlife, including casual sex (plus ça change):

It vas hout-and-hout good scoff, and no flies.

(The spelling is not a mistake. It presumably mimics the speaker’s accent.)

And a word which demands a wider airing is stompie, a cigarette butt, or a partially-smoked cigarette, especially one stubbed out and kept for relighting later, as in South African playwright Athol Fugard’s

The whiteman stopped the bulldozer and smoked a cigarette… He threw me the stompie.

.

The Development of the English Dictionary

The Development of the English Dictionary

Although the printing press made standardising English spelling much easier, it was not until 130 year later with the arrival of the first English dictionary that people could confirm the formal correctness of a written word.

Dictionaries provided readily verifiable, written confirmation of the rules of English spelling.

Due to the development of the English dictionary, the Early Modern period saw a significant breakthrough in the standardisation of the English language.

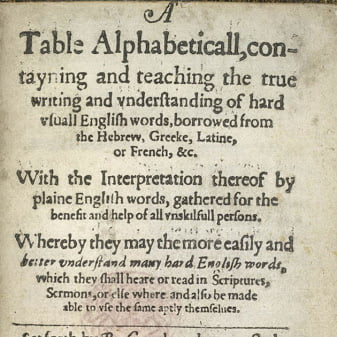

Robert Cawdrey’s A Table Alphabeticall

The first English dictionary, A Table Alphabeticall, was compiled by English school teacher, Robert Cawdrey and published in London in 1604. However, it was found rather unreliable.

The first edition of the dictionary was just 120 pages long and contained only 2,543 words, many of which were obscure.

The primary focus of Cawdrey’s work were those words he thought of as ‘hard’ for the general public because they had foreign roots. This meant that most common words were not included.

The first English dictionary, A Table Alphabeticall Robert Cawdrey, 1604 –Image source

Spelling Checks with Brief Definitions

Another problem for Cawdrey’s dictionary was that its definitions were very brief and often consisted of only one word, making it more a book of synonyms than a useful academic reference.

Although the reader could check their spelling using the dictionary, they had no way of finding out what the word actually meant or how it should be used.

Despite its shortcomings, Cawdrey’s A Table Alphabeticall proved quite popular, and ran into four editions. Each edition increased in length with the final edition in 1617 containing a total of 3,264 words.

The last surviving first edition of Cawdrey’s dictionary can be found in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, which is one of the oldest libraries in Europe.

Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language

It was not until 1755 when Samuel Johnson produced A Dictionary of the English Language that the dialect of London became the official English standard.

Johnson’s comprehensive dictionary took seven scholars eight years to complete. The resulting reference work listed 40,000 words and contained detailed definitions, illustrations and quotations to fully explain the background of each word and its usage.

This dictionary was a great achievement. Johnson spearheaded the idea of using literary quotations to aid in the definitions, making liberal use of Shakespeare and Milton.

Johnson’s personality also comes through in his reference work and it contains various reflections of his own right-wing political slant, along with humorous asides and even some of his own invented words.

1. Title page of Samuel Johnson’s ‘A Dictionary of the English Language’

2. Portrait of Samuel Johnson by Joshua Reynolds, 1772

Insights into Language Usage

Despite Johnson’s own opinions and idiosyncrasies coming through on every page, his dictionary proved hugely popular and was highly respected.

With Johnson’s reliable English dictionary, people could now find out exactly how to spell many common and uncommon words in the English language, as well as gain insight into their proper usage, historical background and literary use.

The official spellings and definitions of English words had at last been declared and the spelling of the English language had become standardised.

This standardisation helped push the English language towards the Late Modern period and the English language that we all know today.

Share your thoughts on the first English dictionary

Have you ever seen a copy of Cawdrey’s or Johnson’s dictionary?

Do you think the authors of the dictionary should include their own opinions and comments or stick to the facts?

What percentage of a language’s words do you think need to be included in a good dictionary?

Would you find literary quotations useful when looking up a new word?

Next: Late Modern English

Attributions

- Volume Two of Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language title page. By Samuel Johnson 1709-1784 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

- Portrait of Samuel Johnson by Joshua Reynolds, 1772, commissioned for Henry Thrale’s Streatham Park gallery. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

I answered a similar question on Linguistics SE, which I will plagiarize in part here:

How etymological research is done has varied through time. In the case of the «New English Dictionary» (the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary), work started on it in 1857. Then:

[I]n January 1859, the Society issued their ‘Proposal for the publication of a New English Dictionary,’ in which the characteristics of the proposed work were explained, and an appeal made to the English and American public to assist in collecting the raw materials for the work, these materials consisting of quotations illustrating the use of English words by all writers of all ages and in all senses, each quotation being made on a uniform plan on a half-sheet of notepaper, that they might in due course be arranged and classified alphabetically and by meanings. This Appeal met with a generous response: some hundreds of volunteers began to read books, make quotations, and send in their slips to ‘sub-editors,’ who volunteered each to take charge of a letter or part of one, and by whom the slips were in tum further arranged, classified, and to some extent used as the basis of definitions and skeleton schemes of the meanings of words in preparation for the Dictionary.

An Appeal to the English-Speaking and English-Reading Public to Read Books and Make Extracts for The Philological Society’s New English Dictionary

One significant contributor to the early OED worth mentioning is William Chester Minor (1834 – 1920). He was insane, but he was also good at doing etymological research. His story, graphic in some parts, can be found here:

What made him so good, so prolific, was his method: Instead of copying quotations willy-nilly, he’d flip through his library and make a word list for each individual book, indexing the location of nearly every word he saw. These catalogues effectively transformed Minor into a living, breathing search engine. He simply had to reach out to the Oxford editors and ask: So, what words do you need help with?

The «Reading Programme» is still used by the OED, although the methodology is different. The books are still read all the same but here’s what happens next according to a freelance researcher for the OED:

I then consult OED Online to determine whether the word or phrase is in the Dictionary: if it is not, I submit it as a ‘not-in’, and if it is, I decide whether its form or context is important enough to warrant its submission. If it does qualify, I enter the information into tagged fields in an electronic file that has been set up in a standard format. When I have finished the reading, I submit the file to Oxford or New York, where the records are incorporated into OED‘s working database for consideration by the editors, along with thousands of paper citation slips, as they proceed through the current revision. Yes, some of my finds are still submitted as paper slips—a reminder of OED‘s long heritage—but, electronic or paper, I can hardly imagine a better job.

The quotations were collected in a machine readable format for the first time in 1989. The 1990 UK Reading Programme captured material electronically. (Note that the second edition of the Oxford English Dictionary came out in 1989.)

In addition to this, the OED now utilizes several online databases of texts, such as Early English Books Online, Eighteenth Century Collections Online, and some newspaper databases.

I have access (for now) to several of these paywalled databases through my college.

If you do your own research with databases (many people use the free Google Books), it’s often easy to find antedatings for pages that haven’t been updated for the third edition of the OED. Updates to the OED3 started in 2000 and continue to this day: it’s a huge dictionary and updating takes time.

See also:

- OED: Researching the Language

Although,

as we have seen from the preceding paragraph, there is as yet no

coherent doctrine in English lexicography, its richness and variety

are everywhere admitted and appreciated. Its history is in its way

one of the most remarkable developments in linguistics, and is

therefore worthy of special attention. In the following pages a short

outline of its various phases is given.

A

need for a dictionary or glossary has been felt in the cultural

growth of many civilised peoples at a fairly early period. The

history of dictionary-making for the English language goes as far

back as the Old English period where its first traces are found in

the form of glosses of religious books with interlinear translation

from Latin. Regular bilingual English-Latin dictionaries were already

in existence in the 15th century.

The

unilingual dictionary is a comparatively recent type. The first

unilingual English dictionary, explaining words by English

equivalents, appeared in 1604.

It

was meant to explain difficult words occurring in books. Its title

was “A Table Alphabeticall, containing and teaching the true

writing and understanding of hard usuall

English

words borrowed from the Hebrew, Greeke, Latine or French”. The

little volume of 120

pages

explaining about 3000

words

was compiled by one Robert Cawdrey, a schoolmaster. Other books

followed, each longer than the preceding one. The first attempt at a

dictionary including all the words of the language, not only the

difficult ones, was made by Nathaniel Bailey who in 1721

published

the first edition of his “Universal Etymological English

Dictionary”. He was the first to include pronunciation and

etymology.

Big

explanatory dictionaries were created in France and Italy before they

appeared for the English language. Learned academies on the continent

had been established to preserve the purity of their respective

languages. This was also the purpose of Dr Samuel Johnson’s famous

Dictionary published in 1755.1

The idea of purity involved a tendency to oppose change, and S.

Johnson’s Dictionary was meant to establish the English language in

its classical form, to preserve it in all its glory as used by J.

Dryden, A. Pope, J. Addison and their contemporaries. In conformity

with the social order of his time, S. Johnson attempted to “fix”

and regulate English. This was the period of much discussion about

the necessity of “purifying” and “fixing” English, and S.

Johnson wrote that every change was undesirable, even a change for

the best. When his work was accomplished, however, he had to admit he

had been wrong and confessed in his preface that “no dictionary of

a living tongue can ever be perfect, since while it is hastening to

publication, some

words

are budding and some falling away”. The most important innovation

of S. Johnson’s Dictionary was the introduction of illustrations of

the meanings of the words “by examples from the best writers»,

as had been done before him in the dictionary of the French Academy.

Since then such illustrations have become a “sine qua non” in

lexicography; S. Johnson, however, only mentioned the authors and

never gave any specific references for his quotations. Most probably

he reproduced some of his quotations from memory, not always very

exactly, which would have been unthinkable in modern lexicology. The

definitions he gave were often very ingenious. He was called “a

skilful definer”,

but sometimes he preferred to give way to sarcasm or humour and did

not hesitate to be partial in his definitions. The epithet he gave to

lexicographer,

for

instance, is famous even in our time: a

lexicographer was

‘a writer of dictionaries, a harmless drudge …’.

The

dictionary dealt with separate words only, almost no set expressions

were entered. Pronunciation was not marked, because S. Johnson was

keenly aware of the wide variety of the English pronunciation and

thought it impossible to set up a standard there; he paid attention

only to those aspects of vocabulary where he believed he could

improve linguistic usage. S. Johnson’s influence was tremendous. He

remained the unquestionable authority on style and diction for more

than 75

years.

The result was a lofty bookish style which received the name of

“Johnsonian” or “Johnsonese”.

As

to pronunciation, attention was turned to it somewhat later. A

pronouncing dictionary that must be mentioned first was published in

1780

by

Thomas Sheridan, grandfather of the great dramatist. In 1791

appeared

“The Critical Pronouncing Dictionary and Expositor of the English

Language” by John Walker, an actor. The vogue of this second

dictionary was very great, and in later publications Walker’s

pronunciations were inserted into S. Johnson’s text —

a

further step to a unilingual dictionary in its present-day form.

The

Golden Age of English lexicography began in the last quarter of the

19th century when the English Philological Society started work on

compiling what is now known as “The Oxford English Dictionary”

(OED), but was originally named “New English Dictionary on

Historical Principles”. It is still occasionally referred to as

NED.

The

purpose of this monumental work is to trace the development of

English words from their form in Old English, and if they were not

found in Old English, to show when they were introduced into the

language, and also to show the development of each meaning and its

historical relation to other meanings of the same word. For words and

meanings which have become obsolete the date of the latest occurrence

is given. All this is done by means of dated quotations ranging from

the oldest to recent appearances of the words in question. The

English of G. Chaucer, of the “Bible” and of W. Shakespeare is

given as much attention as that of the most modern authors. The

dictionary includes spellings, pronunciations and detailed

etymologies. The completion of the work required more than 75

years.

The result is a kind of encyclopaedia of language used not only for

reference purposes but also as a basis for lexicological research.

The

lexicographic concept here is very different from the prescriptive

tradition of Dr S. Johnson: the lexicographer is the objective

recorder of the language. The purpose of OED, as stated by its

editors, has nothing to do with prescription or proscription of any

kind.

The

conception of this new type of dictionary was born in a discussion at

the English Philological Society. It was suggested by Frederick

Furnivall, later its second titular editor, to Richard Trench, the

author of the first book on lexicology of the English language.

Richard Trench read before the society his paper “On Some

Deficiencies in our English Dictionaries», and that was how the

big enterprise was started. At once the Philological Society set to

work to gather the material, volunteers offered to help by collecting

quotations. Dictionary-making became a sort of national enterprise. A

special committee prepared a list of books to be read and assigned

them to the volunteers, sending them also special standard slips for

quotations. By 1881

the

number of readers was 800,

and

they sent in many thousands of slips. The tremendous amount of work

done by these volunteers testifies to the keen interest the English

take in their language.

The

first part of the Dictionary appeared in 1884

and

the last in 1928.

Later

it was issued in twelve volumes and in order to accommodate new words

a three volume Supplement was issued in 1933.

These

volumes were revised in the seventies. Nearly all the material of the

original Supplement was retained and a large body of the most recent

accessions to the English language added.

The

principles, structure and scope of “The Oxford English Dictionary»,

its merits and demerits are discussed in the most comprehensive

treaty by L.V. Malakhovsky. Its prestige is enormous. It is

considered superior to corresponding major dictionaries for other

languages. The Oxford University Press published different abridged

versions. “The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical

Principles” formerly appeared in two volumes, now printed on

thinner paper it is bound in one volume of 2,538

pages.

It differs from the complete edition in that it contains a smaller

number of quotations. It keeps to all the main principles of

historical presentation and covers not only the current literary and

colloquial English but also its previous stages. Words are defined

and illustrated with key quotations.

“The

Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English” was first published

in 1911,

i.e.

before the work on the main version was completed. It is not a

historical dictionary but one of current usage. A still shorter form

is “The Pocket Oxford Dictionary”.

Another

big dictionary, also created by joined effort of enthusiasts, is

Joseph Wright’s “English Dialect Dictionary”. Before this

dictionary could be started upon, a thorough study of English

dialects had to be completed. With this aim in view W.W. Skeat,

famous for his “Etymological English Dictionary” founded the

English Dialect Society as far back as 1873.

Dialects

are of great importance for the historical study of the language. In

the 19th century they were very pronounced though now they are almost

disappearing. The Society existed till

1896

and

issued 80

publications,

mostly monographs.

Curiously

enough, the first American dictionary of the English language was

compiled by a man whose name was also Samuel Johnson. Samuel Johnson

Jr., a Connecticut schoolmaster, published in 1798

a

small book entitled “A School Dictionary”. This book was followed

in 1800

by

another dictionary by the same author, which showed already some

signs of Americanisation. It included, for instance, words like

tomahawk

and

wampum,

borrowed

into English from the Indian languages.

It was Noah Webster, universally considered to be the father of

American

lexicography, who emphatically broke away from English idiom, and

embodied in his book the specifically American usage of his time.

His great work, “The American Dictionary of the English Language»,

appeared

in two volumes in 1828

and

later sustained numerous revised and enlarged editions. In many

respects N.

Webster

follows the lead of Dr S. Johnson (the British lexicographer). But he

has also improved and corrected many of S. Johnson’s etymologies

and his definitions are often more exact. N.

Webster

attempted to simplify the spelling and pronunciation that were

current in the USA of the period. He devoted many years to the

collection of words and the preparation of more accurate definitions.

N.

Webster

realised the importance of language for the development of a nation,

and devoted his energy to giving the American English the status of

an independent language, distinct from British English. At that time

the idea was progressive as it helped the unification of separate

states into one federation. The tendency became reactionary later on,

when some modern linguists like H. Mencken shaped it into the theory

of a separate American language, not only different from British

English, but surpassing it in efficiency and therefore deserving to

dominate and supersede all the languages of the world. Even if we

keep within purely linguistic or purely lexical concepts, we shall

readily see that the difference is not so great as to warrant

American English the rank of a separate language, not a variant of

English (see p. 265).

The

set of morphemes is the same. Some words have acquired a new meaning

on American soil and this meaning has or has not penetrated into

British English. Other words kept their earlier meanings that are

obsolete and not used in Great Britain. As civilisation progressed

different names were given to new inventions on either side of the

Atlantic. Words were borrowed from different Indian languages and

from Spanish. All these had to be recorded in a dictionary and so

accounted for the existence of specific American lexicography. The

world of today with its ever-growing efficiency and intensity of

communication and personal contacts, with its press, radio and

television creates conditions which tend to foster not an isolation

of dialects and variants but, on the contrary, their mutual

penetration and integration.

Later

on, the title “International Dictionary of the English Language”

was adopted, and in the latest edition not Americanisms but words not

used in America (Britishisms) are marked off.

N.

Webster’s

dictionary enjoyed great popularity from its first editions. This

popularity was due not only to the accuracy and clarity of

definitions but also to the richness of additional information of

encyclopaedic

character,

which had become a tradition in American lexicography. As a

dictionary N.

Webster’s

book aims to treat the entire vocabulary of the language providing

definitions, pronunciation and etymology. As an encyclopaedia it

gives explanations about things named, including scientific and

technical subjects. It does so more concisely than a full-scale

encyclopaedia, but it is worthy of note that the definitions are as a

rule up-to-date and rigorous scientifically.

Soon

after N.

Webster’s

death two printers and booksellers of Massachusetts,

George and Charles Merriam, secured the rights of his dictionary from

his family and started the publication of revised single volume

editions under the name “Merriam-Webster”. The staff working for

the modern editions is a big institution numbering hundreds of

specialists in different branches of human activity.

It

is important to note that the name “Webster” may be attached for

publicity’s sake by anyone to any dictionary. Many publishers

concerned with their profits have taken this opportunity to issue

dictionaries called “Webster’s”. Some of the books so named are

cheaply-made reprints of old editions, others are said to be entirely

new works. The practice of advertising by coupling N.

Webster’s

name to a dictionary which has no connection with him, continues up

to the present day.

A

complete revision of N.

Webster’s

dictionary is achieved with a certain degree of regularity. The

recent “Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the

English Language” has called forth much comment, both favourable

and unfavourable. It has been greatly changed as compared with the

previous edition, in word selection as well as in other matters. The

emphasis is on the present-day state of the language. The number of

illustrative quotations is increased. To accommodate the great number

of new words and meanings without increasing the bulk of the volume,

the editors excluded much encyclopaedic material.

The

other great American dictionaries are the “Century Dictionary»,

first completed in 1891;

“Funk

and Wagnalls New Standard Dictionary», first completed in 1895;

the

“Random House Dictionary of the English Language», completed

in 1967;

“The

Heritage Illustrated Dictionary of the English Language», first

published in 1969,

and

C.L. Barnhart’s et al. “The World Book Dictionary” presenting a

synchronic review of the language in the 20th century. The first

three continue to appear in variously named subsequent editions

including abridged versions. Many small handy popular dictionaries

for office, school and home use are prepared to meet the demand in

reference books on spelling, pronunciation, meaning and usage.

An

adequate idea of the dictionaries cannot be formed from a mere

description and it is no substitute for actually using them. To

conclude we would like to mention that for a specialist in

linguistics and a teacher of foreign languages systematic work with a

good dictionary in conjunction with his reading is an absolute

necessity.

Lexicography

is an important branch of linguistics which covers the theory and

practice of compiling dictionaries.

The

history of lexicography goes back to Old

English where its first traces are

found in the form of glosses of religious books with interlinear

translation from Latin. Regular bilingual English-Latin

dictionaries already existed in the 15th

century.

The

first unilingual English dictionary, explaining words appeared in

1604. It was «A table

alphabetical, containing and teaching the true writing and

understanding of hard usual English words borrowed from the Hebrew,

Greece, Latin or French». This dictionary of 120 pages

explaining about 3000 words was compiled by Robert

Cawdrey, a schoolmaster. Robert

Cawdrey’s Table Alphabetical was the first single-language

English dictionary ever published.

Etymological

Dictionary

Nathaniel

Bailey published the first edition of

Universal Etymological English

Dictionary

in 1721. It was the first

to include pronunciation and etymology. It was a little over 900

pages long. In compiling his dictionary, Bailey borrowed greatly from

John Kersey’s Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum (1706), which in turn

drew from the later editions of Edward Phillips’s The New World of

English Words. Like Kersey’s dictionary, Bailey’s dictionary was one

of the first monolingual English dictionaries to focus on defining

words in common usage, rather than just difficult words.

Although

Bailey put the word «etymological» in his title, he gives

definitions for many words without also trying to give the word’s

etymology. A very high percentage of the etymologies he does give are

consistent with what’s in today’s English dictionaries.

In

1727, Bailey published a supplementary volume entitled The Universal

Etymological English Dictionary, Volume II. Volume II, almost 900

pages, has some duplication or overlap with the primary volume, but

mostly consists of extra words of lesser circulation.

Explanatory

dictionary

The

first big explanatory

dictionary «A

Dictionary of the English Language in

Which the Words are Deduced from Their Originals and Illustrated in

Their General Significations by Examples from the Best Writers: In 2

vols.» was complied by Dr Samuel

Johnson and published in 1755.

The

most important innovation

of S. Johnson’s Dictionary was the introduction of illustrations of

the meanings of the words by examples

from the best writers (around 114,000

quotations). Pronunciation

was not marked,

because S. Johnson was sure of the wide variety

of the English pronunciation and

thought it was impossible to set up a

standard there. He paid attention only to

those aspects of vocabulary where he believed he could improve

linguistic usage. S. Johnson’s

influence was tremendous. He remained the unquestionable authority

for more than 75 years. When it came out the book was huge, not just

in scope but also in size. Johnson himself pronounced the book “Vasta

mole superbus” (“Proud in its great bulk”).

The

completion of the work required more than 75 years. The first part of

the dictionary appeared in 1884 and the last in 1928. Later it was

issued in twelve volumes

in order to hold new words

a three volume Supplement was issued in 1933.

The

Concise Oxford Dictionary of current

English was first published in 1911. It is not a historical

dictionary but of current usage. A still shorter form is The

Pocket Oxford Dictionary. The new

enlarged version of OED was issued in 22 volumes 1994.

With

descriptions for approximately 750,000 words, the Oxford English

Dictionary is the world’s most comprehensive single-language print

dictionary according to the Guiness

Book of World Records.Two Russian

borrowings glasnost

and perestroika

were included in it. This publication was followed by a two- volume

Supplement to hold new words.

English

Dialect Dictionary

Another

big dictionary is Joseph Wright’s

«English Dialect Dictionary».

Before this dictionary could be started upon, a

thorough study of English dialects had to

be completed. The English Dialect Dictionary, being the complete

vocabulary of all dialect words still in use, or known to have been

in use during the last two hundred years; founded on the publications

of the English Dialect Society and on a large amount of material

never before printed was published by Oxford University Press in 6

volumes between 1898 and 1905. Its compilation and printing was

funded privately by Joseph Wright, a self-taught philologist at the

University of Oxford.

Due

to the scale of the work, 70,000 entries, and the period in which the

information was gathered, it is regarded as a standard work in the

historical study of dialect. Wright marked annotations and

corrections in a cut-up and rebound copy of the first edition; this

copy is among Wright’s papers in the Bodleian Library at the

University of Oxford.

Pronouncing

dictionary

The

first pronouncing dictionary was published in 1780 by Thomas

Sheridan, an Irish stage actor,

educator and a major proponent of the elocution movement. He is the

grandfather of the great dramatist. The title page of the dictionary

says «A complete dictionary of the English language with regard

to sound and meaning. One main object of which is to establish a

plain and permanent standard of pronunciation to which is prefixed a

prosodial grammar.»

In

1791 there appeared The Critical

Pronouncing Dictionary and Expositor of the English Language

by John Walker, an actor.

Oxford

English Dictionary

The

Golden Age of English lexicography

began in the last quarter of the 19th century when the English

Philological Society started work on compiling The

Oxford English Dictionary (OED) which

was originally named New English

Dictionary on Historical Principles

(NED). It is still referred to as either OED or NED.

The

objective of

this dictionary was and still is to trace the

development of English words from their

form in Old English.

If the word was not found

in Old English, it was shown when

it was introduced into the language. For words and meanings which

have become obsolete the date of the latest

occurrence is provided. The dictionary

includes spellings,

pronunciations and detailed etymologies.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

The Development of the English Dictionary

The Development of the English Dictionary

![By Samuel Johnson 1709-1784 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Johnson_Dictionary3.jpg The First English Dictionary - Samuel Johnson](http://www.myenglishlanguage.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Johnson-Dictionary.jpg)