English is a beautiful language, and one of its many perks is the one-word sentences. One-word sentences — as the name suggests is a sentence with a single word, and which makes total sense.

One word sentences can be used in different forms. It could be in form of a question such as “Why?” It could be in form of a command such as “Stop!” Furthermore, it could be used as a declarative such as “Me.” Also, a one-word sentence could be used to show location, for example, “here.” It could also be used as nominatives e.g. “David.”

Actually, most of the words in English can be turned into one-word sentences. All that matters is the context in which they are used. In a sentence, there is usually a noun, and a verb. In a one-word sentence, the subject and the action of the sentence is implied in the single word, and this is why to understand one-word sentences, one has to understand the context in which the word is being used.

Saying only a little at all times is a skill most people want to learn; knowing when to use one-word sentences can help tremendously. However, you cannot use one-word sentences all the time so as robotic or come off as rude.

Here are common one-word sentences, and their meanings:

Here are common one-word sentences, and their meanings:

- Help: This signifies a call for help.

- Hurry: Used to ask someone to do something faster

- Begin: Used to signify the beginning of a planned event.

Basically, the 5 Wh-question words — where, when, why, who and what? can also stand as one-word sentences.

By Bizhan Romani

Dr. Bizhan Romani has a PhD in medical virology. When it comes to writing an article about science and research, he is one of our best writers. He is also an expert in blogging about writing styles, proofreading methods, and literature.

What does a conjunction do?Where is a conjunction used?What is a conjunction? Here we have answers to all these questions! Conjunctions, one of the English parts of speech, act as linkers to join different parts of a sentence. Without conjunctions, the expression of the complex ideas will seem odd as you will have to use…

Introduction An adverb is a word that modifies a sentence, verb, or adjective. An adverb can be a word or simply an expression that can even change prepositions, and clauses. An adverb usually ends only- but some are the same as their adjectives counterparts. Adverbs express the time, place, frequency, and level of certainty. The…

What is a noun?What are all types of nouns?How is a noun used in a sentence? A noun is referred to any word that names something. This could be a person, place, thing, or idea. Nouns play different roles in sentences. A noun could be a subject, direct object, indirect object, subject complement, object complement,…

What is a pronoun?How is a pronoun used in a sentence?What are all types of pronouns? A pronoun is classified as a transition word and a subcategory of a noun that functions in every capacity that a noun will function. They can function as both subjects and objects in a sentence. Let’s see the origin…

In the English language, sentence construction is quite imperative to understanding. A sentence can be a sequence, set or conglomerate of words that is complete in itself as it typically contains a subject, verb, object and predicate. However, this sentence regardless of its intent, would be chaotic if not constructed properly. Proper sentence construction helps…

Image by Ozzy Delaney on Flickr.com licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Here I’m going to highlight some of the simplest sentences in English. All of these sentences are only ONE word long! Sit back, relax, and enjoy; these are going to be some of the easiest English sentences you’ve ever learned. (It is about time something in English was easy, right?!)

One-word sentences in English come in a few different forms:

interrogatives or questions (example: Who?)

imperatives or commands (example: Stop!)

declaratives (example: Me.)

locatives (example: Here.)

nominatives (example: Jesse.)

In fact a lot of words in English can be one-word sentences, it all depends on the context.

A complete sentence, even a one-word sentence, needs to have a noun and a verb. In one-word sentences the subject (noun) or the action (verb) of the sentence is implied. That means it is understood in the context of the sentence (or the sentences around it) so that the subject and/or verb do not need to be stated explicitly.

Being brief and saying as much as you can in as few words as possible is something a lot of people want to do. Be careful though, sometimes you can sound robotic or rude if you use too many one-word sentences.

Here is a list of some common one-word sentences. I’m sure you already use some of these. Along side the one-word sentences I have written out what you could say, with more words, to mean the same thing.

Hi. (Hi there.)

Wait. (Please wait.)

Begin. (You may begin.)

Stop. (You need to stop.)

Hurry. (Hurry up please.)

Catch. (Catch this.)

Here. (Here you go.)

Go! (Get going now!)

Help! (I need help!)

Eat. (Go ahead and eat.)

Yes. (Yes, that would be great.)

No. (No, thank you.)

Thank you. (Thank you, I really appreciate it.)

The wh-question words: Who? What? Where? When? Why? How?

A lot of swear words: Sh*t., F*ck., etc.

Do you have a favorite one-word sentence? Add to this list by posting a comment below! Thank you.

I am trying to find the name for the rather recent, I think, rhetorical device of one-word sentences used for emphasis and effect.

For example:

Columnist Ruth Marcus, writing for the Washington Post, wrote this of Hillary Clinton’s speaking fees:

“You don’t need any more! Just. Stop. Speaking. For. Pay.”

Columnist Michael Barone, writing in the Washington Examiner, wrote this about the chances of a contested Republican convention:

“I have bad news for those looking forward to a brokered convention. It. Isn’t. Going. To. Happen.”

Final example: Bob asks, «Are you ever going to stop using sentence fragments in your writing?»

Mary responds, «I. Don’t. Think. So.»

So, in the realm of rhetorical devices . . .

Repetition of a beginning word, phrase, or clause in consecutive sentences = Anaphora.

Insertion of conjunctions between every item in a series = Polysyndeton.

One. Word. Sentences. = ? ? ?

Can anyone help?

Footnote for anyone reading. From the related question, in terms of a search for the origin, really the best possibility which came to the fore was: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comic_book_guy. Possibly 1997. But the origin is still totally unclear, unfortunately; CBG could have been referring to something from the 80s, say.

It might sound a little outlandish, but you can form sentences with only one word. That’s right; you can write one word and then place a period (or exclamation mark) to close it. This article will explore some examples to help you understand them.

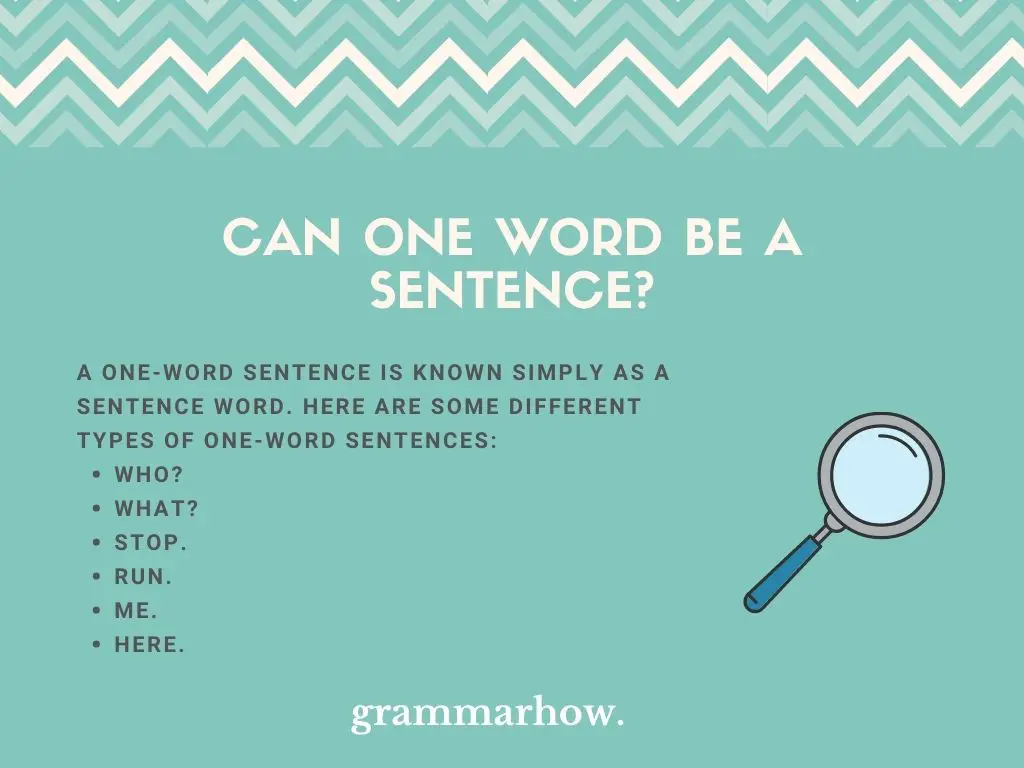

Can One Word Be A Sentence?

Of course, it’s possible to come across one word as a sentence. Here are some of the types that we will mention in this article:

- Interrogatives

- Imperatives

- Declaratives

- Locatives

- Nominatives

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Accusatives

- Exclamations

A one-word sentence is known simply as a sentence word. The above types are all the broader words we can use to describe specific types of sentence words. Each one offers a different way for us to use a one-word sentence when they apply.

Interrogatives

Interrogatives are the most common form of sentence words. We use them mainly as questions because they cover the most common words in English like “who,” “what,” and “where.” These words are all simple one-word sentences in the form of direct questions.

Here are some of the best interrogatives you can use:

- Who?

- What?

- Where?

- How?

- When?

- Why?

As you can see, each one is followed by a question mark. This shows that all interrogatives work best when we are directing them as a question toward someone.

It’s also common for the answer to be a sentence word, but it depends on the context. Most of the answers you can give to interrogative sentence words will apply to one of the other sections coming up in the article.

Imperatives

Imperatives are commanding words. We can use verbs to command someone to do something in the imperative case. It’s common for imperative sentences to have only one word because it shows the emphasis and need of someone to follow whatever command you are giving.

Since all imperatives are commands in the form of verbs, these examples should help you to understand them:

- Stop.

- Don’t.

- Leave.

- Go.

- Run.

- Walk.

- Work.

- Return.

Each of these verb forms allows us to give someone a command. The period after each one really emphasizes the need for someone to listen to what we have to say.

It can be easy for some people to ignore commands, which is why the imperative form exists. We can use these sentence words with a stern tone to show that we are only interested in someone listening to us (it’s usually for their own good).

Declaratives

Declaratives allow us to declare ourselves or someone else as an answer. We can use declaratives like “me” when we want to show that we are happy to declare ourselves or our actions in some way. Again, this mostly works when we are replying to specific questions.

There aren’t many good declaratives, but they’re still used. Here are some examples:

- Me.

- Aye.

It’s difficult to come up with many more legitimate declaratives. Some people might argue that “she” or “he” would work, but it’s not common for English speakers to use either of those pronouns as a sentence word.

That’s why “me” is the most appropriate declarative because it’s reasonable to expect someone to declare themselves as a candidate for something.

“Aye” also works because it’s a proclamation that we agree with something.

Locatives

Locatives are a more specific branch of sentence words we can use. They are word forms that always refer to locations. For example, we might say something like “here” or “there” when we are trying to show where something is happening. That’s how locatives work.

Locatives relate to locations, which these examples will make clear:

- Here.

- There.

- Everywhere.

- Nowhere.

- Home.

- Near.

- Far.

- Wherever.

- Somewhere.

As long as a position or place is mentioned in the sentence word, locatives work well. They work when replying to certain questions, so you might benefit from checking out the following examples:

- Where do you live?

- Here.

- Where were they last?

- There.

As you can see, we use them to reply to questions about someone or something’s location.

Nominatives

Nominatives are ways for us to nominate someone else. We can offer names, people, and things in the nominative case. It’s most common to see someone’s name as the nominative form when we are presenting a sentence word answer to a question.

Nominatives can cover anyone’s name, so we’ll include some examples to help you:

- Jane.

- John.

- Sarah.

- Stuart.

- Smith.

- Daniel.

- Craig.

- Lewis.

- Martin.

There are plenty of questions that could lead us to use a nominative form. For example, if someone asked us who completed a specific job, we could provide the name if we know the person that did it.

Technically, we can also provide names of items or objects rather than just people. It mostly refers to things that you can nominate or pick out as a culprit for something, which is why it works well in many different cases.

Adjectives

Adjectives are a common form in the English language. We use them as descriptive words, but it’s also common to see them as sentence words. However, it mostly only applies to informal situations when you want to use adjectives in this manner.

Here are a couple of examples to help you out:

- Pretty.

- Cute.

- Nice.

- Kind.

- Happy.

- Friendly.

- Incredible.

- Amazing.

- Brilliant.

- Gorgeous.

- Ugly.

- Grim.

While it’s easy to easy adjectives in the sentence word form, you might not be entirely sure how to use them correctly. Remember, it’s mostly an informal construct because you would be expected to use more words formally.

You might find it useful to also see a question and answer formation to see how this works:

- What do you think of this artwork?

- Gorgeous.

- How do you find her?

- Pretty.

As you can see, each of the adjective answers allows us to modify a specific noun listed in the question. For example, the first question asked about “artwork,” which we can modify with the responsive adjective “gorgeous.”

The second example used the noun “her,” and the descriptive word was “pretty.”

Adverbs

Adverbs are similar to adjectives. However, they usually include an “-ly” ending after the adjective and modify verbs. We can use adverbs to modify the verb that might have been presented in the previous question. If the question has no verb, an adverb cannot work.

These examples will help you make more sense of what adverbs can do:

- Calmly.

- Softly.

- Easily.

- Quickly.

- Gently.

- Nicely.

- Happily.

- Confidently.

- Rapidly.

- Cautiously.

- Barely.

You might also benefit from the following question and answer examples to help you figure it out:

- Would you take a look at this for me?

- Happily.

- How should I speak when giving the address?

- Confidently.

As you can see, we can only use adverb answers when someone has provided a verb for us to modify. In the first example, we are modifying the verb “look” with “happily” to show that we’re happy to take a look at what they’ve done.

The second example modifies the verb “speak” with “confidently” to show that we have a specific desire to listen to someone speak with a confident tone.

Accusatives

Accusatives are exactly what the name would suggest they are. We can use them to accuse someone specifically. The most common way for us to do this as a sentence word is by using object pronouns to point the finger toward someone you might have done something wrong.

If you don’t know what we mean, these examples will clear things up:

- Him.

- Her.

- Them.

- That.

- It.

- You.

- Me.

- Us.

Accusatives work well when someone has asked us for a culprit. If we know that someone has done something wrong (or even if we know that someone will be helpful to answer a question), we can use this form.

Here are some examples that should help you:

- Do you know who did it?

- Him.

- Who is the smartest person here?

- Her.

It doesn’t always have to refer to bad things. Sometimes, we can use the accusative form just to pick someone out from a crowd. It’s a quick way for us to respond to a question with a pronoun rather than an explanation.

Exclamations

Exclamations are another really common form of sentence words. A simple “yes” or “no” can apply when we are using exclamations. They are called exclamations because they allow someone to exclaim their answer to a question without more explanation.

Here are a couple of examples that will help you to figure it out:

- Yes.

- No.

- Maybe.

- Oh.

There are plenty of other exclamations in English, and some people will treat them more as interjections. For example, you might be familiar with ones like “huh” or “err.”

However, we didn’t want to include these ones because they’re not technically words that you can use in English. It’s always best to stick with ones that actually have definitions, which is why we thought it was reasonable to only include a handful.

Now you have all the necessary information to help you start using sentence words yourself. Exclamations tend to be one of the most common ways to do this without even thinking about it, so get to work!

Martin holds a Master’s degree in Finance and International Business. He has six years of experience in professional communication with clients, executives, and colleagues. Furthermore, he has teaching experience from Aarhus University. Martin has been featured as an expert in communication and teaching on Forbes and Shopify. Read more about Martin here.

That is dialogue, so pretty much anything goes. You goal should be to represent the character’s speech in an effective and non-distracting manner.

So this is fine.

In narrative, you should be more careful, but yes it can still be done.

Typically, a one word sentence is used for extreme emphasis and because it encapsulates a great deal. It «means more than it says.»

A good example comes from the Stephen King story «The Mangler.» In which an evil industrial laundry folder catches someone’s arm and begins to pull them in.

(those things actually are called manglers)

In any case, even after they pull the plug its still running, crushing this guy’s arm.

So his friend runs and gets the fire axe.

The line is:

The axe came down. Twice.

There is a lot contained in that single word at the end there. An entire motion. It means he wrenched the axe free of his bleeding screaming friend, and brought it down again.

And that is the utility of single word sentences.

edit- rereading it, I’m actually not sure your example was dialogue, but my comments stand.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A sentence word (also called a one-word sentence) is a single word that forms a full sentence.

Henry Sweet described sentence words as ‘an area under one’s control’ and gave words such as «Come!», «John!», «Alas!», «Yes.» and «No.» as examples of sentence words.[1] The Dutch linguist J. M. Hoogvliet described sentence words as «volzinwoorden».[2] They were also noted in 1891 by Georg von der Gabelentz, whose observations were extensively elaborated by Hoogvliet in 1903; he does not list «Yes.» and «No.» as sentence words. Wegener called sentence words «Wortsätze».[3]

Single-word utterances and child language acquisition[edit]

One of the predominant questions concerning children and language acquisition deals with the relation between the perception and the production of a child’s word usage. It is difficult to understand what a child understands about the words that they are using and what the desired outcome or goal of the utterance should be.[4]

Holophrases are defined as a «single-word utterance which is used by a child to express more than one meaning usually attributed to that single word by adults.»[5] The holophrastic hypothesis argues that children use single words to refer to different meanings in the same way an adult would represent those meanings by using an entire sentence or phrase. There are two opposing hypotheses as to whether holophrases are structural or functional in children. The two hypotheses are outlined below.

Structural holophrastic hypothesis[edit]

The structural version argues that children’s “single word utterances are implicit expressions of syntactic and semantic structural relations.” There are three arguments used to account for the structural version of the holophrastic hypothesis: The comprehension argument, the temporal proximity argument, and the progressive acquisition argument.[5]

- The comprehension argument is based on the idea that comprehension in children is more advanced than production throughout language acquisition. Structuralists believe that children have knowledge of sentence structure but they are unable to express it due to a limited lexicon. For example, saying “Ball!” could mean “Throw me the ball” which would have the structural relation of the subject of the verb. However, studies attempting to show the extent to which children understand syntactic structural relation, particularly during the one-word stage, end up showing that children “are capable of extracting the lexical information from a multi-word command,” and that they “can respond correctly to a multi-word command if that command is unambiguous at the lexical level.”[5] This argument therefore does not provide evidence needed to prove the structural version of the holophrastic hypothesis because it fails to prove that children in the single-word stage understand structural relations such as the subject of a sentence and the object of a verb.[5]

- The temporal proximity argument is based on the observation that children produce utterances referring to the same thing, close to each other. Even the utterances aren’t connected, it is argued that children know about the linguistic relationships between the words, but cannot connect them yet.[5] An example is laid out below:

→ Child: «Daddy» (holding pair of fathers pants)

- → Child

-

-

- «Bai» (‘bai’ is the term the child uses for any item of clothing)

-

The usage of ‘Daddy’ and ‘Bai’ used in close proximity are seen to represent a child’s knowledge of linguistic relations; in this case the relation is the ‘possessive’.[6] This argument is seen as having insufficient evidence as it is possible that the child is only switching from one way to conceptualize pants to another. It is also pointed out that if the child had knowledge of linguistic relationships between words, then the child would combine the words together, instead of using them separately.[5]

- Finally, the last argument in support of structuralism is the progressive acquisition argument. This argument states that children progressively gain new structural relations throughout the holophrastic stage. This is also unsupported by the research.[5]

Functional holophrastic hypothesis[edit]

Functionalists doubt whether children really have structural knowledge, and argue that children rely on gestures to carry meaning (such as declarative, interrogative, exclamative or vocative). There are three arguments used to account for the functional version of the holophrastic hypothesis: The intonation argument, the gesture argument, and the predication argument.[5]

- The intonation argument suggests that children use intonation in a contrastive way. Researchers have established through longitudinal studies that children have knowledge of intonation and can use it to communicate a specific function across utterances.[7][8][9] Compare the two examples below:

→ Child: «Ball.» (flat intonation) — Can mean «That is a ball.»

-

-

- → Child: «Ball?» (rising inflection) — Can mean «Where is the ball?»

-

- However, it has been noted by Lois Bloom that there is no evidence that a child intends for intonation to be contrastive, it is only that adults are able to interpret it as such.[10] Martyn Barrett contrasts this with a longitudinal study performed by him, where he illustrated the acquisition of a rising inflection by a girl who was a year and a half old. Although she started out using intonation randomly, upon acquisition of the term «What’s that» she began to use rising intonation exclusively for questions, suggesting knowledge of its contrastive usage.[11]

- The gesture argument establishes that some children use gesture instead of intonation contrastively. Compare the two examples laid out below:

→ Child: «Milk.» (points at milk jug) — could mean “That is milk.”

-

-

- → Child: «Milk.» (open-handed gesture while reaching for a glass of milk) — could mean “I want milk.”

-

- Each use of the word ‘milk’ in the examples above could have no use of intonation, or a random use of intonation, and so meaning is reliant on gesture. Anne Carter observed, however, that in the early stages of word acquisition children use gestures primarily to communicate, with words merely serving to intensify the message.[12] As children move onto multi-word speech, content and context are also used alongside gesture.

- The predication argument suggests that there are three distinct functions of single word utterances, ‘Conative’, which is used to direct the behaviour of oneself or others; ‘Expressive’, which is used to express emotion; and referential, which is used to refer to things.[13] The idea is that holophrases are predications, which is defined as the relationship between a subject and a predicate. Although McNeill originally intended this argument to support the structural hypothesis, Barrett believes that it more accurately supports the functional hypothesis, as McNeill fails to provide evidence that predication is expressed in holophrases.[5]

Single-word utterances and adult usage[edit]

While children use sentence words as a default strategy due to lack of syntax and lexicon, adults tend to use sentence words in a more specialized way, generally in a specific context or to convey a certain meaning. Because of this distinction, single word utterances in children are called ‘holophrases’, while in adults, they are called ‘sentence words’. In both the child and adult use of sentence words, context is very important and relative to the word chosen, and the intended meaning.

Sentence word formation[edit]

Many sentence words have formed from the process of devaluation and semantic erosion. Various phrases in various languages have devolved into the words for «yes» and «no» (which can be found discussed in detail in yes and no), and these include expletive sentence words such as «Well!» and the French word «Ben!» (a parallel to «Bien!»).[14]

However, not all word sentences suffer from this loss of lexical meaning. A subset of sentence words, which Fonagy calls «nominal phrases», exist that retain their lexical meaning. These exist in Uralic languages, and are the remainders of an archaic syntax wherein there were no explicit markers for nouns and verbs. An example of this is the Hungarian language «Fecske!», which transliterates as «Swallow!», but which has to be idiomatically translated with multiple words «Look! A swallow!» for rendering the proper meaning of the original, which to a native Hungarian speaker is neither elliptical nor emphatic. Such nominal phrase word sentences occur in English as well, particularly in telegraphese or as the rote questions that are posed to fill in form data (e.g. «Name?», «Age?»).[14]

Sentence word syntax[edit]

A sentence word involves invisible covert syntax and visible overt syntax. The invisible section or «covert» is the syntax that is removed in order to form a one word sentence. The visible section or «overt» is the syntax that still remains in a sentence word.[15] Within sentence word syntax there are 4 different clause-types: Declarative (making a declaration), exclamative (making an exclamation), vocative (relating to a noun), and imperative (a command).

| Overt | Covert | |

|---|---|---|

| Declarative | ‘That is excellent!’

|

‘Excellent!’

|

| Exclamative | ‘That was rude!’

|

‘Rude!’

|

| Vocative | ‘There is Mary!’

|

‘Mary!’

|

| Imperative | ‘You should leave!’

|

‘Leave!’

|

| Locative | ‘The chair is here.’

|

‘Here.’

|

| Interrogative | ‘Where is it?’

|

‘Where?’

|

The words in bold above demonstrate that in the overt syntax structures, there are words that can be omitted in order to form a covert sentence word.

Distribution cross-linguistically[edit]

Other languages use sentence words as well.

- In Japanese, a holophrastic or single-word sentence is meant to carry the least amount of information as syntactically possible, while intonation becomes the primary carrier of meaning.[16] For example, a person saying the Japanese word e.g. «はい» (/haɪ/) = ‘yes’ on a high level pitch would command attention. Pronouncing the same word using a mid tone, could represent an answer to a roll-call. Finally, pronouncing this word with a low pitch could signify acquiescence: acceptance of something reluctantly.[16]

| High tone pitch | Mid tone pitch | Low tone pitch |

|---|---|---|

| Command attention | Represent an answer to roll-call | Signify acquiescence acceptance of something reluctantly |

- Modern Hebrew also exhibits examples of sentence words in its language, e.g. «.חַם» (/χam/) = «It is hot.» or «.קַר» (/kar/) = «It is cold.».

References[edit]

- ^ Henry Sweet (1900). «Adverbs». A New English Grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 127. ISBN 978-1-4021-5375-4.

- ^ Jan Noordegraaf (2001). «J. M. Hoogvliet as a teacher and theoretician». In Marcel Bax; C. Jan-Wouter Zwart; A. J. van Essen (eds.). Reflections on Language and Language Learning. John Benjamins B.V. p. 24. ISBN 978-90-272-2584-9.

- ^ Giorgio Graffi (2001). 200 Years of Syntax. John Benjamins B.V. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-58811-052-7.

- ^ Hoff, Erika (2009). Language Development. Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 167.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Barrett, Martyn, D. (1982). «The holophrastic hypothesis: Conceptual and empirical issues». Cognition. 11: 47–76. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(82)90004-x.

- ^ Rodgon, M.M. (1976). Single word usage, cognitive development and the beginnings of combinatorial speech. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Dore, J. (1975). «Holophrases, speech acts and language universals». Journal of Child Language. 2: 21–40. doi:10.1017/s0305000900000878.

- ^ Leopold, W.F. (1939). Speech Development of a Bilingual Child: A Linguist’s Record. Volume 1: Vocabulary growth in the first two years. Evanston, ill: Northwestern University Press.

- ^ Von Raffler Engel, W. (1973). «The development from sound to phoneme in child language». Studies of Child Language Development.

- ^ Bloom, Lois (1973). One word at a time: The use of single word utterances before syntax. The Hague: Mouton.

- ^ Barrett, M.D (1979). Semantic Development during the Single-Word Stage of Language Acquisition (Unpublished doctoral thesis).

- ^ Carter, Anne :L. (1979). «Prespeech meaning relations an outline of one infant’s sensorimotor morpheme development». Language Acquisition: 71–92.

- ^ David, McNeill (1970). The Acquisition of Language: The Study of Developmental Psycholinguistics.

- ^ a b Ivan Fonagy (2001). Languages Within Language. John Benjamins B.V. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-927232-82-1.

- ^ Carnie, Andrew (2012). Syntax: a generative introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 496.

- ^ a b Hirst, D. (1998). Intonation systems: a survey of twenty languages. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. p. 372.

.

.

.

I’m elbow-deep in judging entries in a national contest for unpublished authors right now. And in so doing, it’s easy to see which writers use fragments, single words, and one-line paragraphs because they’ve seen it in published books and thought it looked cool—but it isn’t a natural part of their voice/style as a writer—and for which ones it flows naturally. Because when it’s something that is natural and comfortable for the author, the reader won’t even notice it.

I recently read a historical romance in which the author employed a purposeful technique of dividing up complex sentences into incomplete fragments. It got to the point where not only was it noticeable, it was jarring and got to be annoying after awhile—because all she needed was a conjunction or a verb and they would be complete sentences which would have flowed much better.

When fragments, one-word sentences, or one-line paragraphs are forced, it’s obvious. So how do we make this part of our writer’s toolbox?

Not everyone will. This may not be a technique that will work for every author. Most of us who employ this technique may not even realize we’ve done it until we go back and re-read what we wrote during the revision process. And sometimes, what we think works well as a fragment may not work for readers—because they don’t have the whole story and backstory running through their head as they’re reading the way we do.

But when they work, they really work.

Fragments, one-word sentences, and one-line paragraphs are very handy when there’s something important, something vital happening—and the author needs to punch home a point. Fragments and one-word sentences work well after long sentences. One-line paragraphs work well to break up a page of long paragraphs of narrative.

Let’s look at the opening paragraphs of Ransome’s Quest:

- No moon. Wispy clouds hid most of the stars. He could not have asked for a more perfect night. Before him, the house glowed like a lantern atop the hill. Behind him, his men waited for his command.

Julia Witherington was back in Jamaica. Finally. The pirate paused a moment, trying to count the years—the ages, the epochs—he had been on the quest to strike back at Admiral Sir Edward Witherington.

Julia was married—and had brought her husband here with her. The inimitable Commodore William Ransome. The admiral’s favorite; the man he’d taken publicly in hand as son long before Ransome married the admiral’s daughter. The one man in the world the pirate hated almost as much as the admiral.

And from later in the book:

- “You owe me a pair of boots, Miss Ransome.” Salvador tossed the waterlogged ones back into the privy. Suresh bustled about him, helping the captain don fresh hose and boots, a neckcloth, waistcoat, and his gold braid–adorned coat.

Charlotte did not dare move throughout the proceeding. Once Salvador again resembled a Royal Navy commodore, he crossed to exit the cabin; but before he did, he turned and looked at her.

Here it came—the rebuke for her action. Would he yell? Be deadly calm like William?

“In that trunk, there”—he pointed to an ornate chest under the hammock she’d slept in—“you will find clothing you can borrow until yours dry.” He left the cabin, Suresh his silent shadow.

Strange man.

Unsure of when the pirate captain or his steward might return, Charlotte peeled out of her wet dress and crossed to kneel before the trunk. She lifted the lid, and a delicate scent of roses met her nose. Closing her eyes, she inhaled the scent, picturing herself in Lady Dalrymple’s rose garden again.

Sure, I could have made those all into complete sentences:

- There was no moon.

Julia Witherington was back in Jamaica, finally.

Julia was married—and had brought her husband, the inimitable Commodore William Ransome, here with her.

Captain Salvador was such a strange man.

But see how they lose their impact that way?

Sometimes, I fight with these fragments and one-liners. Sometimes, they do come out initially as the less impactful full sentences—but that’s what the revision process is for. Sometimes, I write the fragment and when I go back and re-read it later, it doesn’t even make any sense to me. But for the most part, when I’ve lost myself in the flow of the writing, these things happen naturally—because my writer’s voice has taken over and drowned out the internal editor that tells me shouldn’t/can’t/don’t/never.

But I have to go back to why I first started using this technique. I started using this technique because it came naturally to me. I love long, drawn out, complex sentences. But I can’t structure every sentence that way. And sometimes, I just need to quip. And that’s what a fragment or one-line paragraph is. It’s the punch line. It’s the quip. Even if it’s not meant to be funny—even if it’s meant to be jarring or suspenseful. It’s the slam of a door, the bang of a gun. The piece you want to stick out for your readers to remember.

Fragments. Love them, hate them. They’re here to stay.

Do you notice it when authors use fragments, one-word sentences, and one-line paragraphs? Does it ever get to a point where it’s so noticeable it takes you out of the story? As a writer, have you ever struggled with this technique or tried to implement it even if it didn’t feel natural?