From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structural constraints on speakers’ or writers’ composition of clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraints, a field that includes domains such as phonology, morphology, and syntax, often complemented by phonetics, semantics, and pragmatics. There are currently two different approaches to the study of grammar: traditional grammar and theoretical grammar.

Fluent speakers of a language variety or lect have effectively internalized these constraints,[1] the vast majority of which – at least in the case of one’s native language(s) – are acquired not by conscious study or instruction but by hearing other speakers. Much of this internalization occurs during early childhood; learning a language later in life usually involves more explicit instruction.[2] In this view, grammar is understood as the cognitive information underlying a specific instance of language production.

The term «grammar» can also describe the linguistic behavior of groups of speakers and writers rather than individuals. Differences in scales are important to this sense of the word: for example, the term «English grammar» could refer to the whole of English grammar (that is, to the grammar of all the speakers of the language), in which case the term encompasses a great deal of variation.[3] At a smaller scale, it may refer only to what is shared among the grammars of all or most English speakers (such as subject–verb–object word order in simple declarative sentences). At the smallest scale, this sense of «grammar» can describe the conventions of just one relatively well-defined form of English (such as standard English for a region).

A description, study, or analysis of such rules may also be referred to as grammar. A reference book describing the grammar of a language is called a «reference grammar» or simply «a grammar» (see History of English grammars). A fully explicit grammar, which exhaustively describes the grammatical constructions of a particular speech variety, is called descriptive grammar. This kind of linguistic description contrasts with linguistic prescription, an attempt to actively discourage or suppress some grammatical constructions while codifying and promoting others, either in an absolute sense or about a standard variety. For example, some prescriptivists maintain that sentences in English should not end with prepositions, a prohibition that has been traced to John Dryden (13 April 1668 – January 1688) whose unexplained objection to the practice perhaps led other English speakers to avoid the construction and discourage its use.[4][5] Yet preposition stranding has a long history in Germanic languages like English, where it is so widespread as to be a standard usage.

Outside linguistics, the term grammar is often used in a rather different sense. It may be used more broadly to include conventions of spelling and punctuation, which linguists would not typically consider as part of grammar but rather as part of orthography, the conventions used for writing a language. It may also be used more narrowly to refer to a set of prescriptive norms only, excluding those aspects of a language’s grammar which are not subject to variation or debate on their normative acceptability. Jeremy Butterfield claimed that, for non-linguists, «Grammar is often a generic way of referring to any aspect of English that people object to.»[6]

Etymology[edit]

The word grammar is derived from Greek γραμματικὴ τέχνη (grammatikḕ téchnē), which means «art of letters», from γράμμα (grámma), «letter», itself from γράφειν (gráphein), «to draw, to write».[7] The same Greek root also appears in the words graphics, grapheme, and photograph.

History[edit]

The first systematic grammar of Sanskrit, originated in Iron Age India, with Yaska (6th century BC), Pāṇini (6th–5th century BC[8]) and his commentators Pingala (c. 200 BC), Katyayana, and Patanjali (2nd century BC). Tolkāppiyam, the earliest Tamil grammar, is mostly dated to before the 5th century AD. The Babylonians also made some early attempts at language description.[9]

Grammar appeared as a discipline in Hellenism from the 3rd century BC forward with authors such as Rhyanus and Aristarchus of Samothrace. The oldest known grammar handbook is the Art of Grammar (Τέχνη Γραμματική), a succinct guide to speaking and writing clearly and effectively, written by the ancient Greek scholar Dionysius Thrax (c. 170–c. 90 BC), a student of Aristarchus of Samothrace who founded a school on the Greek island of Rhodes. Dionysius Thrax’s grammar book remained the primary grammar textbook for Greek schoolboys until as late as the twelfth century AD. The Romans based their grammatical writings on it and its basic format remains the basis for grammar guides in many languages even today.[10] Latin grammar developed by following Greek models from the 1st century BC, due to the work of authors such as Orbilius Pupillus, Remmius Palaemon, Marcus Valerius Probus, Verrius Flaccus, and Aemilius Asper.

The grammar of Irish originated in the 7th century with the Auraicept na n-Éces. Arabic grammar emerged with Abu al-Aswad al-Du’ali in the 7th century. The first treatises on Hebrew grammar appeared in the High Middle Ages, in the context of Mishnah (exegesis of the Hebrew Bible). The Karaite tradition originated in Abbasid Baghdad. The Diqduq (10th century) is one of the earliest grammatical commentaries on the Hebrew Bible.[11] Ibn Barun in the 12th century, compares the Hebrew language with Arabic in the Islamic grammatical tradition.[12]

Belonging to the trivium of the seven liberal arts, grammar was taught as a core discipline throughout the Middle Ages, following the influence of authors from Late Antiquity, such as Priscian. Treatment of vernaculars began gradually during the High Middle Ages, with isolated works such as the First Grammatical Treatise, but became influential only in the Renaissance and Baroque periods. In 1486, Antonio de Nebrija published Las introduciones Latinas contrapuesto el romance al Latin, and the first Spanish grammar, Gramática de la lengua castellana, in 1492. During the 16th-century Italian Renaissance, the Questione della lingua was the discussion on the status and ideal form of the Italian language, initiated by Dante’s de vulgari eloquentia (Pietro Bembo, Prose della volgar lingua Venice 1525). The first grammar of Slovene was written in 1583 by Adam Bohorič.

Grammars of some languages began to be compiled for the purposes of evangelism and Bible translation from the 16th century onward, such as Grammatica o Arte de la Lengua General de Los Indios de Los Reynos del Perú (1560), a Quechua grammar by Fray Domingo de Santo Tomás.

From the latter part of the 18th century, grammar came to be understood as a subfield of the emerging discipline of modern linguistics. The Deutsche Grammatik of the Jacob Grimm was first published in the 1810s. The Comparative Grammar of Franz Bopp, the starting point of modern comparative linguistics, came out in 1833.

Theoretical frameworks[edit]

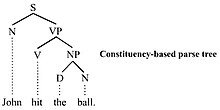

A generative parse tree: the sentence is divided into a noun phrase (subject), and a verb phrase which includes the object. This is in contrast to structural and functional grammar which consider the subject and object as equal constituents.[13][14]

Frameworks of grammar which seek to give a precise scientific theory of the syntactic rules of grammar and their function have been developed in theoretical linguistics.

- Dependency grammar: dependency relation (Lucien Tesnière 1959)

- Link grammar

- Functional grammar (structural–functional analysis):

- Danish Functionalism

- Functional Discourse Grammar

- Role and reference grammar

- Systemic functional grammar

- Montague grammar

Other frameworks are based on an innate «universal grammar», an idea developed by Noam Chomsky. In such models, the object is placed into the verb phrase. The most prominent biologically-oriented theories are:

- Cognitive grammar / Cognitive linguistics

- Construction grammar

- Fluid Construction Grammar

- Word grammar

- Construction grammar

- Generative grammar:

- Transformational grammar (1960s)

- Generative semantics (1970s) and Semantic Syntax (1990s)

- Phrase structure grammar (late 1970s)

- Generalised phrase structure grammar (late 1970s)

- Head-driven phrase structure grammar (1985)

- Principles and parameters grammar (Government and binding theory) (1980s)

- Generalised phrase structure grammar (late 1970s)

- Lexical functional grammar

- Categorial grammar (lambda calculus)

- Minimalist program-based grammar (1993)

- Stochastic grammar: probabilistic

- Operator grammar

Parse trees are commonly used by such frameworks to depict their rules. There are various alternative schemes for some grammar:

- Affix grammar over a finite lattice

- Backus–Naur form

- Constraint grammar

- Lambda calculus

- Tree-adjoining grammar

- X-bar theory

Development of grammar[edit]

Grammars evolve through usage. Historically, with the advent of written representations, formal rules about language usage tend to appear also, although such rules tend to describe writing conventions more accurately than conventions of speech.[15] Formal grammars are codifications of usage which are developed by repeated documentation and observation over time. As rules are established and developed, the prescriptive concept of grammatical correctness can arise. This often produces a discrepancy between contemporary usage and that which has been accepted, over time, as being standard or «correct». Linguists tend to view prescriptive grammar as having little justification beyond their authors’ aesthetic tastes, although style guides may give useful advice about standard language employment based on descriptions of usage in contemporary writings of the same language. Linguistic prescriptions also form part of the explanation for variation in speech, particularly variation in the speech of an individual speaker (for example, why some speakers say «I didn’t do nothing», some say «I didn’t do anything», and some say one or the other depending on social context).

The formal study of grammar is an important part of children’s schooling from a young age through advanced learning, though the rules taught in schools are not a «grammar» in the sense that most linguists use, particularly as they are prescriptive in intent rather than descriptive.

Constructed languages (also called planned languages or conlangs) are more common in the modern-day, although still extremely uncommon compared to natural languages. Many have been designed to aid human communication (for example, naturalistic Interlingua, schematic Esperanto, and the highly logic-compatible artificial language Lojban). Each of these languages has its own grammar.

Syntax refers to the linguistic structure above the word level (for example, how sentences are formed) – though without taking into account intonation, which is the domain of phonology. Morphology, by contrast, refers to the structure at and below the word level (for example, how compound words are formed), but above the level of individual sounds, which, like intonation, are in the domain of phonology.[16] However, no clear line can be drawn between syntax and morphology. Analytic languages use syntax to convey information that is encoded by inflection in synthetic languages. In other words, word order is not significant, and morphology is highly significant in a purely synthetic language, whereas morphology is not significant and syntax is highly significant in an analytic language. For example, Chinese and Afrikaans are highly analytic, thus meaning is very context-dependent. (Both have some inflections, and both have had more in the past; thus, they are becoming even less synthetic and more «purely» analytic over time.) Latin, which is highly synthetic, uses affixes and inflections to convey the same information that Chinese does with syntax. Because Latin words are quite (though not totally) self-contained, an intelligible Latin sentence can be made from elements that are arranged almost arbitrarily. Latin has a complex affixation and simple syntax, whereas Chinese has the opposite.

Education[edit]

Prescriptive grammar is taught in primary and secondary school. The term «grammar school» historically referred to a school (attached to a cathedral or monastery) that teaches Latin grammar to future priests and monks. It originally referred to a school that taught students how to read, scan, interpret, and declaim Greek and Latin poets (including Homer, Virgil, Euripides, and others). These should not be mistaken for the related, albeit distinct, modern British grammar schools.

A standard language is a dialect that is promoted above other dialects in writing, education, and, broadly speaking, in the public sphere; it contrasts with vernacular dialects, which may be the objects of study in academic, descriptive linguistics but which are rarely taught prescriptively. The standardized «first language» taught in primary education may be subject to political controversy because it may sometimes establish a standard defining nationality or ethnicity.

Recently, efforts have begun to update grammar instruction in primary and secondary education. The main focus has been to prevent the use of outdated prescriptive rules in favor of setting norms based on earlier descriptive research and to change perceptions about the relative «correctness» of prescribed standard forms in comparison to non-standard dialects. A series of metastudies have found that the explicit teaching of grammatical parts of speech and syntax has little or no effect on the improvement of student writing quality in elementary school, middle school of high school; other methods of writing instruction had far greater positive effect, including strategy instruction, collaborative writing, summary writing, process instruction, sentence combining and inquiry projects.[17][18][19]

The preeminence of Parisian French has reigned largely unchallenged throughout the history of modern French literature. Standard Italian is based on the speech of Florence rather than the capital because of its influence on early literature. Likewise, standard Spanish is not based on the speech of Madrid but on that of educated speakers from more northern areas such as Castile and León (see Gramática de la lengua castellana). In Argentina and Uruguay the Spanish standard is based on the local dialects of Buenos Aires and Montevideo (Rioplatense Spanish). Portuguese has, for now, two official standards, respectively Brazilian Portuguese and European Portuguese.

The Serbian variant of Serbo-Croatian is likewise divided; Serbia and the Republika Srpska of Bosnia and Herzegovina use their own distinct normative subvarieties, with differences in yat reflexes. The existence and codification of a distinct Montenegrin standard is a matter of controversy, some treat Montenegrin as a separate standard lect, and some think that it should be considered another form of Serbian.

Norwegian has two standards, Bokmål and Nynorsk, the choice between which is subject to controversy: Each Norwegian municipality can either declare one as its official language or it can remain «language neutral». Nynorsk is backed by 27 percent of municipalities. The main language used in primary schools, chosen by referendum within the local school district, normally follows the official language of its municipality. Standard German emerged from the standardized chancellery use of High German in the 16th and 17th centuries. Until about 1800, it was almost exclusively a written language, but now it is so widely spoken that most of the former German dialects are nearly extinct.

Standard Chinese has official status as the standard spoken form of the Chinese language in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Republic of China (ROC), and the Republic of Singapore. Pronunciation of Standard Chinese is based on the local accent of Mandarin Chinese from Luanping, Chengde in Hebei Province near Beijing, while grammar and syntax are based on modern vernacular written Chinese.

Modern Standard Arabic is directly based on Classical Arabic, the language of the Qur’an. The Hindustani language has two standards, Hindi and Urdu.

In the United States, the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar designated 4 March as National Grammar Day in 2008.[20]

See also[edit]

- Ambiguous grammar

- Constraint-based grammar

- Grammeme

- Harmonic Grammar

- Higher order grammar (HOG)

- Linguistic error

- Linguistic typology

- Paragrammatism

- Speech error (slip of the tongue)

- Usage (language)

- Usus

Notes[edit]

- ^ Traditionally, the mental information used to produce and process linguistic utterances is referred to as «rules». However, other frameworks employ different terminology, with theoretical implications. Optimality theory, for example, talks in terms of «constraints», while construction grammar, cognitive grammar, and other «usage-based» theories make reference to patterns, constructions, and «schemata»

- ^ O’Grady, William; Dobrovolsky, Michael; Katamba, Francis (1996). Contemporary Linguistics: An Introduction. Harlow, Essex: Longman. pp. 4–7, 464–539. ISBN 978-0-582-24691-1. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Holmes, Janet (2001). An Introduction to Sociolinguistics (second ed.). Harlow, Essex: Longman. pp. 73–94. ISBN 978-0-582-32861-7. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.; for more discussion of sets of grammars as populations, see: Croft, William (2000). Explaining Language Change: An Evolutionary Approach. Harlow, Essex: Longman. pp. 13–20. ISBN 978-0-582-35677-1. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Rodney Huddleston and Geoffrey K. Pullum, 2002, The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press, p. 627f.

- ^ Lundin, Leigh (23 September 2007). «The Power of Prepositions». On Writing. Cairo: Criminal Brief. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ Jeremy Butterfield, (2008). Damp Squid: The English Language Laid Bare, Oxford University Press, Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-957409-4. p. 142.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «Grammar». Online Etymological Dictionary. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ Ashtadhyayi, Work by Panini. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2013. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

Ashtadhyayi, Sanskrit Aṣṭādhyāyī («Eight Chapters»), Sanskrit treatise on grammar written in the 6th to 5th century BCE by the Indian grammarian Panini.

- ^ McGregor, William B. (2015). Linguistics: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-567-58352-9.

- ^ Casson, Lionel (2001). Libraries in the Ancient World. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-300-09721-4. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ G. Khan, J. B. Noah, The Early Karaite Tradition of Hebrew Grammatical Thought (2000)

- ^ Pinchas Wechter, Ibn Barūn’s Arabic Works on Hebrew Grammar and Lexicography (1964)

- ^ Schäfer, Roland (2016). Einführung in die grammatische Beschreibung des Deutschen (2nd ed.). Berlin: Language Science Press. ISBN 978-1-537504-95-7. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ Butler, Christopher S. (2003). Structure and Function: A Guide to Three Major Structural-Functional Theories, part 1 (PDF). John Benjamins. pp. 121–124. ISBN 9781588113580. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ Carter, Ronald; McCarthy, Michael (2017). «Spoken Grammar: Where are We and Where are We Going?». Applied Linguistics. 38: 1–20. doi:10.1093/applin/amu080.

- ^ Gussenhoven, Carlos; Jacobs, Haike (2005). Understanding Phonology (second ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. ISBN 978-0-340-80735-4. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools – A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York.Washington, DC:Alliance for Excellent Education.

- ^ Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 445–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.445

- ^ Graham, S., McKeown, D., Kiuhara, S., & Harris, K. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for students in the elementary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 879–896. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029185

- ^ «National Grammar Day». Quick and Dirty Tips. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

References[edit]

- Rundle, Bede. Grammar in Philosophy. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1979. ISBN 0-19-824612-9.

External links[edit]

Look up grammar in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

German Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Grammar from the Oxford English Dictionary

- Sayce, Archibald Henry (1911). «Grammar» . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grammar.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Grammar.

Educalingo cookies are used to personalize ads and get web traffic statistics. We also share information about the use of the site with our social media, advertising and analytics partners.

Download the app

educalingo

We’re talking about the struggle to drag a thought over from the mush of the unconscious into some kind of grammar, syntax, human sense; every attempt means starting over with language. starting over with accuracy.

Anne Carson

ETYMOLOGY OF THE WORD GRAMMAR

From Old French gramaire, from Latin grammatica, from Greek grammatikē ( tekhnē) the grammatical (art), from grammatikos concerning letters, from gramma letter.

Etymology is the study of the origin of words and their changes in structure and significance.

PRONUNCIATION OF GRAMMAR

GRAMMATICAL CATEGORY OF GRAMMAR

Grammar is a noun.

A noun is a type of word the meaning of which determines reality. Nouns provide the names for all things: people, objects, sensations, feelings, etc.

WHAT DOES GRAMMAR MEAN IN ENGLISH?

Grammar

In linguistics, grammar is the set of structural rules governing the composition of clauses, phrases, and words in any given natural language. The term refers also to the study of such rules, and this field includes morphology, syntax, and phonology, often complemented by phonetics, semantics, and pragmatics.

Definition of grammar in the English dictionary

The first definition of grammar in the dictionary is the branch of linguistics that deals with syntax and morphology, sometimes also phonology and semantics. Other definition of grammar is the abstract system of rules in terms of which a person’s mastery of his native language can be explained. Grammar is also a systematic description of the grammatical facts of a language.

WORDS THAT RHYME WITH GRAMMAR

Synonyms and antonyms of grammar in the English dictionary of synonyms

SYNONYMS OF «GRAMMAR»

The following words have a similar or identical meaning as «grammar» and belong to the same grammatical category.

Translation of «grammar» into 25 languages

TRANSLATION OF GRAMMAR

Find out the translation of grammar to 25 languages with our English multilingual translator.

The translations of grammar from English to other languages presented in this section have been obtained through automatic statistical translation; where the essential translation unit is the word «grammar» in English.

Translator English — Chinese

文法

1,325 millions of speakers

Translator English — Spanish

gramática

570 millions of speakers

English

grammar

510 millions of speakers

Translator English — Hindi

व्याकरण

380 millions of speakers

Translator English — Arabic

نَحْو

280 millions of speakers

Translator English — Russian

грамматика

278 millions of speakers

Translator English — Portuguese

gramática

270 millions of speakers

Translator English — Bengali

grammalogue

260 millions of speakers

Translator English — French

grammaire

220 millions of speakers

Translator English — Malay

Grammalogue

190 millions of speakers

Translator English — German

Grammatik

180 millions of speakers

Translator English — Japanese

文法

130 millions of speakers

Translator English — Korean

문법

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Javanese

Grammalogue

85 millions of speakers

Translator English — Vietnamese

ngữ pháp

80 millions of speakers

Translator English — Tamil

grammalogue

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Marathi

ग्रॅमामेल

75 millions of speakers

Translator English — Turkish

grammalogue

70 millions of speakers

Translator English — Italian

grammatica

65 millions of speakers

Translator English — Polish

gramatyka

50 millions of speakers

Translator English — Ukrainian

граматика

40 millions of speakers

Translator English — Romanian

gramatică

30 millions of speakers

Translator English — Greek

γραμματική

15 millions of speakers

Translator English — Afrikaans

grammatika

14 millions of speakers

Translator English — Swedish

grammatik

10 millions of speakers

Translator English — Norwegian

grammatikk

5 millions of speakers

Trends of use of grammar

TENDENCIES OF USE OF THE TERM «GRAMMAR»

The term «grammar» is very widely used and occupies the 9.828 position in our list of most widely used terms in the English dictionary.

FREQUENCY

Very widely used

The map shown above gives the frequency of use of the term «grammar» in the different countries.

Principal search tendencies and common uses of grammar

List of principal searches undertaken by users to access our English online dictionary and most widely used expressions with the word «grammar».

FREQUENCY OF USE OF THE TERM «GRAMMAR» OVER TIME

The graph expresses the annual evolution of the frequency of use of the word «grammar» during the past 500 years. Its implementation is based on analysing how often the term «grammar» appears in digitalised printed sources in English between the year 1500 and the present day.

Examples of use in the English literature, quotes and news about grammar

10 QUOTES WITH «GRAMMAR»

Famous quotes and sentences with the word grammar.

I think most people agree there is a component of skill in art making; you have to learn grammar before you learn how to write.

I demand that my books be judged with utmost severity, by knowledgeable people who know the rules of grammar and of logic, and who will seek beneath the footsteps of my commas the lice of my thought in the head of my style.

My father was an autodidact. It wasn’t a middle-class house. Shopkeepers are aspirant. He paid for me to go to private school. He was denied an education — he had a horrible childhood. He got a place at a grammar school and wasn’t allowed to go.

What that book does for me is give me the tools in the same way that I had the tools when I learned the regular scales or the alphabet. If you give me the tools, the syntax, and the grammar, it still doesn’t tell me how to write Ulysses.

His eyes so dim, so wasted each limb, that, heedless of grammar, they all cried, that’s him!

We’re talking about the struggle to drag a thought over from the mush of the unconscious into some kind of grammar, syntax, human sense; every attempt means starting over with language. starting over with accuracy.

In my grammar school years back in the 1920s I used my ten-cents-a-week allowance for Saturday matinees of Douglas Fairbanks movies. All that swashbuckling and leaping about in the midst of the sails of ships!

Going to a grammar school, you mixed with all sorts of different types and I used to listen to how they talked. When I did my imitations, I could sound like someone really rough, or I could sound like a cabinet minister.

It’s really difficult for me. Language, I am sorry that I haven’t. I think I just always expected that you learn a word in place of a word and when I discovered how difficult the grammar was and learning that was very discouraging for me.

Grammar is a piano I play by ear. All I know about grammar is its power.

10 ENGLISH BOOKS RELATING TO «GRAMMAR»

Discover the use of grammar in the following bibliographical selection. Books relating to grammar and brief extracts from same to provide context of its use in English literature.

1

The Blue Book of Grammar and Punctuation: An Easy-to-Use …

The Blue Book of Grammar and Punctuation is filled with easy-to-understand rules,real-world examples, dozens of reproducible exercises, and pre- and post-tests.

2

The Only Grammar Book You’ll Ever Need: A One-Stop Source …

The Only Grammar Book You’ll Ever Need is the ideal resource for everyone who wants to produce writing that is clear, concise, and grammatically excellent.

Susan Thurman, Larry Shea, 2003

3

A Grammar Book for You and I— Oops, Me!: All the Grammar …

Correct English usage as it’s never been taught before: lucidly, memorably, and humorously — for all ages.

4

Grammar: A Student’s Guide

This introductory guide to grammar explains one hundred basic grammatical terms.

5

Classical Japanese: A Grammar

In this carefully crafted volume, Michael Kort describes the wartime circumstances and thinking that form the context for the decision to use these weapons, surveys the major debates related to that decision, and provides a comprehensive …

Without question, this is the definitive grammar of the Hawaiian language.

Samuel H. Elbert, Mary Kawena Pukui, 2001

7

Oxford Modern English Grammar

This book has been written by a leading expert in the field, covers both British and American English, and makes use of the unrivalled language monitoring of Oxford’s English Dictionaries programme.

Help kids succeed in class and on tests with these fun, super-quick daily exercises that provide essential practice in math, reading and writting, social studies, and test taking—and help meet that standards.

Judith Bauer Stamper, 2003

This two-book series was written specifically for English language learners and covers all the basic grammar topics for beginners.

Anne Seaton, Y. H. Mew, 2007

10

A Coptic grammar: with chrestomathy and glossary : Sahidic …

Layton avoids all jargon and non-standard legal, scientific or magical texts, in order to provide a carefully explained grammar that is easy to use.

10 NEWS ITEMS WHICH INCLUDE THE TERM «GRAMMAR»

Find out what the national and international press are talking about and how the term grammar is used in the context of the following news items.

‘Least worst’ examples of bad grammar

Sir, – You have recently published a number of letters lamenting the decline in standards of grammar and English usage even among … «Irish Times, Jul 15»

The Most Common Grammar Mistakes

Grammar can be an intimidating roadblock if you lack confidence in your content development prowess, until you realize there are common … «Business 2 Community, Jul 15»

Wolverhampton Grammar School girls swing their way to success …

Girls at Wolverhampton Grammar School are swinging their way to success, with Year 8 Girls’ Rounders team being named National Schools … «expressandstar.com, Jul 15»

Grammar schools can destroy the class system

Last week’s first Conservative budget for nearly 20 years will help to secure Britain’s economic future and create a society that rewards … «The Times, Jul 15»

Mind your language: Brush up on grammar, Bombay high court …

The judges said: «Apart from bad grammar and several errors of language, the authority has filed an affidavit full of mistakes and it is reported … «Times of India, Jul 15»

Readers, meet Grammar Moses

Even before Jim Baumann was named managing editor of the paper almost three years ago, he used to issue treatises on grammar to the … «Chicago Daily Herald, Jul 15»

Strunk and Whites Macho Grammar Club

The sleek, no-frills esthetic of Modernism and the gray-flannel ’50s both influenced the utilitarian mindset that dictates the rules of usage in ‘The … «Daily Beast, Jul 15»

Introducing Grammar Moses, a new interactive column on all things …

For as long as I’ve been an editor at the Daily Herald — 25 years — I’ve been compelled to write grammar quizzes, issue diatribes on … «Chicago Daily Herald, Jul 15»

Don Ferguson’s Grammar Gremlins: You didn’t ‘seen’ anything

An otherwise well-spoken woman being interviewed on national television used «I seen» several times during the interview. Why is it that this is … «Knoxville News Sentinel, Jul 15»

Everyday Grammar: You Can Master Reported Speech

We often need to tell others what someone else said. There are two ways to do this. One is to say the same words and use quotation marks. «VOA Learning English, Jul 15»

REFERENCE

« EDUCALINGO. Grammar [online]. Available <https://educalingo.com/en/dic-en/grammar>. Apr 2023 ».

Download the educalingo app

Discover all that is hidden in the words on

grammar

Grammar refers to the way words are used, classified, and structured together to form coherent written or spoken communication.

Continue reading…

gram·mar

(grăm′ər)

n.

1.

a. The study of how words and their component parts combine to form sentences.

b. The study of structural relationships in language or in a language, sometimes including pronunciation, meaning, and linguistic history.

2.

a. The system of inflections, syntax, and word formation of a language.

b. The system of rules implicit in a language, viewed as a mechanism for generating all sentences possible in that language.

3.

a. A normative or prescriptive set of rules setting forth the current standard of usage for pedagogical or reference purposes.

b. Writing or speech judged with regard to such a set of rules.

4. A book containing the morphologic, syntactic, and semantic rules for a specific language.

5.

a. The basic principles of an area of knowledge: the grammar of music.

b. A book dealing with such principles.

[Middle English gramere, from Old French gramaire, alteration of Latin grammatica, from Greek grammatikē, from feminine of grammatikos, of letters, from gramma, grammat-, letter; see gerbh- in Indo-European roots.]

American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. Copyright © 2016 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

grammar

(ˈɡræmə)

n

1. (Grammar) the branch of linguistics that deals with syntax and morphology, sometimes also phonology and semantics

2. (Grammar) the abstract system of rules in terms of which a person’s mastery of his native language can be explained

3. (Grammar) a systematic description of the grammatical facts of a language

4. (Grammar) a book containing an account of the grammatical facts of a language or recommendations as to rules for the proper use of a language

5. (Grammar)

a. the use of language with regard to its correctness or social propriety, esp in syntax: the teacher told him to watch his grammar.

b. (as modifier): a grammar book.

6. the elementary principles of a science or art: the grammar of drawing.

[C14: from Old French gramaire, from Latin grammatica, from Greek grammatikē (tekhnē) the grammatical (art), from grammatikos concerning letters, from gramma letter]

ˈgrammarless adj

Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged, 12th Edition 2014 © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1994, 1998, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2014

gram•mar

(ˈgræm ər)

n.

1. the study of the way the sentences of a language are constructed, esp. the study of morphology and syntax.

2. these features or constructions themselves: English grammar.

3. an account of these features; a set of rules accounting for these constructions: a grammar of English.

4. (in generative grammar) a device, as a set of rules, whose output is all the sentences that are permissible in a given language, while excluding those that are not permissible.

5. the exposition or establishment of rules based on norms of correct and incorrect language usage; prescriptive grammar.

6. knowledge or usage of the preferred or prescribed forms in speaking or writing: His grammar was terrible.

7. the elements of any science, art, or subject.

8. a book treating such elements.

[1325–75; < Old French gramaire < Latin grammatica < Greek grammatikḕ (téchnē) grammatical (art)]

Random House Kernerman Webster’s College Dictionary, © 2010 K Dictionaries Ltd. Copyright 2005, 1997, 1991 by Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.

Grammar

the aspect of grammar that deals with inflections and word order.

1. an ambiguity of language.

2. a word, phrase, or sentence that can be interpreted variously because of uncertainty of grammatical construction rather than ambiguity of the words used, as “John met his father when he was sick.” Also amphibologism, amphiboly. — amphibological, amphibolous, adj.

a lack of grammatical sequence or coherence, as “He ate cereal, fruit, and went to the store.” Also anacoluthia. — anacoluthic, adj.

the substitution of one grammatical case for another, e.g., use of the nominative where the vocative would normally occur. — antiptotic, adj.

the clause that expresses the consequence in a conditional sentence. Cf. protasis.

Medicine. a neurological defect resulting in an inability to use words in grammatical sequence.

1. the study of the principles by which a language or languages function in producing meaningful units of expression.

2. knowledge of the preferred forms of expression and usage in language. See also linguistics. — grammarian, n. — grammatical, adj.

1. Rare. the principles of the study of grammar followed by a grammarian.

2. excessive emphasis upon the fine points of grammar and usage, especially as a shibboleth; dedication to the doctrine of correctness; grammatism.

a principle or a point of grammar.

excessively pedantic behavior about grammatical standards and principles. — grammatist, n.

arrangement of thoughts by subordination in grammatical construction. Cf. parataxis. — hypotactic, adj.

Rare. a word or phrase that violates the rules of grammar. — ingrammatically, adj.

1. a declension, conjugation, etc. that provides all the inflectional forms and serves as a model or example for all others.

2. any model or example. — paradigmatic, paradigmatical, adj.

arrangement of thoughts as coordinate units in grammatical construction. Cf. hypotaxis. — paratactic, adj.

referring to the ability in some languages to use function words instead of inflections, as “the hair of the dog” for “dog’s hair.” — periphrasis, n.

a clause containing the condition in a conditional sentence. Cf. apodosis. See also drama; wisdom and foolishness. — protatic, adj.

a violation of conventional usage and grammar, as “I are sixty year old.” — solecist, n. — solecistic, solecistical, adj.

the use of a word or expression to perform two syntactic functions, especially to apply to two or more words of which at least one does not agree in logic, number, case, or gender, as in Pope’s line “See Pan with flocks, with fruits Pomona crowned.” — sylleptic, sylleptical, adj.

the practice of using a grammatical construction that conforms with meaning rather than with strict regard for syntax, such as a plural form of a verb following a singular subject that has a plural meaning.

the grammatical principles by which words are used in phrases and sentences to construct meaningful combinations. — syntactic, syntactical, adj.

-Ologies & -Isms. Copyright 2008 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

grammar

The way in which elements of a language are put together to make sentences, or the study of the structure of a language.

Dictionary of Unfamiliar Words by Diagram Group Copyright © 2008 by Diagram Visual Information Limited

Most people think of themselves as grammar rebels, seeing the rules as strict, basic and arbitrary. But grammar is actually complex, not to mention essential: Incorrect grammar can cause confusion and change the way you’re perceived (or even keep you from landing a job).

That’s why a grammar checker is essential if writing is part of your workday — even if that’s just sending emails. Here’s what else you should know about grammar:

What is grammar in English?

At a high level, the definition of grammar is a system of rules that allow us to structure sentences. It includes several aspects of the English language, like:

Parts of speech (verbs, adjectives, nouns, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, modifiers, etc.)

Clauses (e.g. independent, dependent, compound)

Punctuation (like commas, semicolons, and periods — when applied to usage)

Mechanics of language (like word order, semantics, and sentence structure)

Grammar’s wide scope can make proofreading difficult. And the dry, academic conversations that often revolve around it can make people’s eyes glaze over. But without these grammatical rules, chaos would ensue. So even if you aren’t a fan (and who really is?), it’s still important to understand.

Types of grammar (and theories)

As long as there have been rules of grammar, there have been theories about what makes it work and how to classify it. For example, American linguist Noam Chomsky posited the theory of universal grammar. It says that common rules dictate all language.

In his view, humans have an innate knowledge of language that informs those rules. That, he reasoned, is why children can pick up on complex grammar without explicit knowledge of the rules. But grammarians still debate about whether this theory holds true.

There are also prescriptive and descriptive grammar types:

Prescriptive grammar is the set of rules people should follow when using the English language.

Descriptive grammar is how we describe the way people are using language.

Another theory emerges from these types of English grammar: primacy of spoken language. It says language comes from the spoken word, not writing — so that’s where you’ll find answers to what’s grammatically correct. Though not everyone agrees with that theory, either.

How did grammar become what it is today?

Grammar has been in a constant state of evolution, starting with the creation of the first textbook on the subject in about 100 BC by the Greeks (termed the Greek grammatikē). The Romans later adapted their grammar to create Latin grammar (or Latin grammatica), which spread out across Europe to form the basis for languages like Spanish and French. Eventually, Latin grammar became the basis of the English model in the 11th century. The rules of grammar (as well as etymology) changed with the times, from Middle English in the 15th century, to what we know today.

Another consequence of grammatical changes has been the development of various areas of linguistic study, like phonology (how languages or dialects organize their sounds) and morphology (how words are formed how and their relationships work).

The ancient grammar rules have changed as people have tested alternative ways to use language. Authors, for example, have broken the rules to various levels of success:

- Shakespeare ended sentences with prepositions: “Fly to others that we know not of.”

- Jane Austen used double negatives: “When Mr. Collins said any thing of which his wife might reasonably be ashamed, which certainly was not unseldom, she involuntarily turned her eye on Charlotte.”

- William Faulkner started sentences with conjunctions: “But before the captain could answer, a major appeared from behind the guns.”

Cultural norms shape grammar rules, too. The Associated Press, for example, recognized they as a singular pronoun in 2017. But before that, English grammar teachers the world over broke out their red pens to change it to he or she.

Yes, American grammar has a longstanding tradition of change — borrowing words from other languages and testing out different forms of expression — which could explain why many find it confusing. Although most people no longer call early education “grammar school,” it’s still an important topic of study. And as more people have access to updated information about the subject, it’s become easier to follow the rules.

Five authors on grammar

If anyone appreciates the role of grammar, it’s writers:

→”Ill-fitting grammar are like ill-fitting shoes. You can get used to it for a bit, but then one day your toes fall off and you can’t walk to the bathroom.” – novelist Jasper Fforde

→“The greater part of the world’s troubles are due to questions of grammar.” – philosopher Michel de Montaigne

→“And all dared to brave unknown terrors, to do mighty deeds, to boldly split infinitives that no man had split before — and thus was the Empire forged.” – novelist Douglas Adams

→“Grammar is a piano I play by ear. All I know about grammar is its power.” – American writer Joan Didion

Six examples of grammar rules

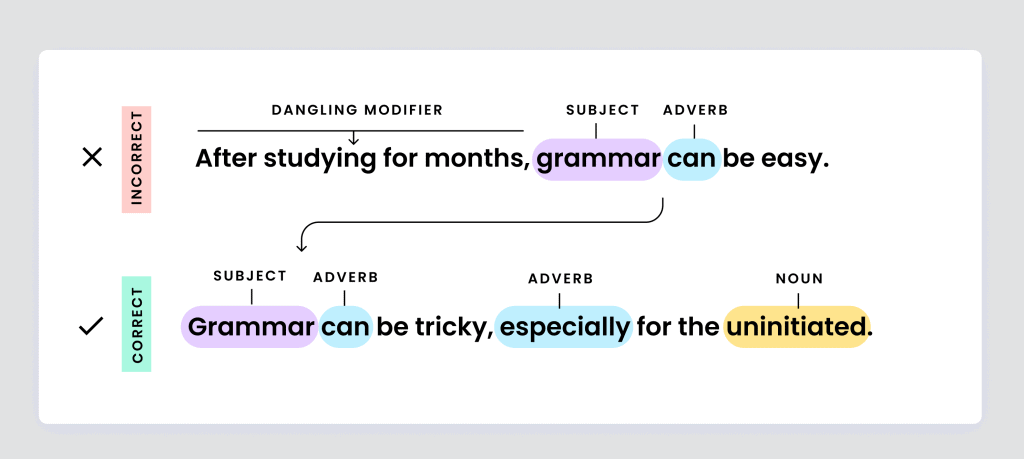

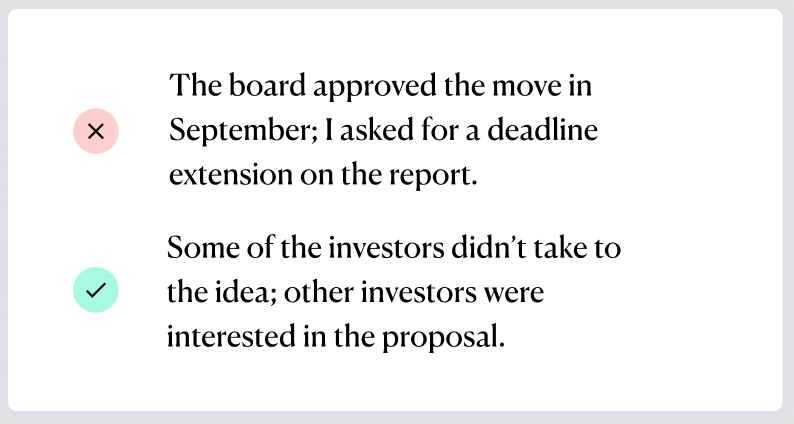

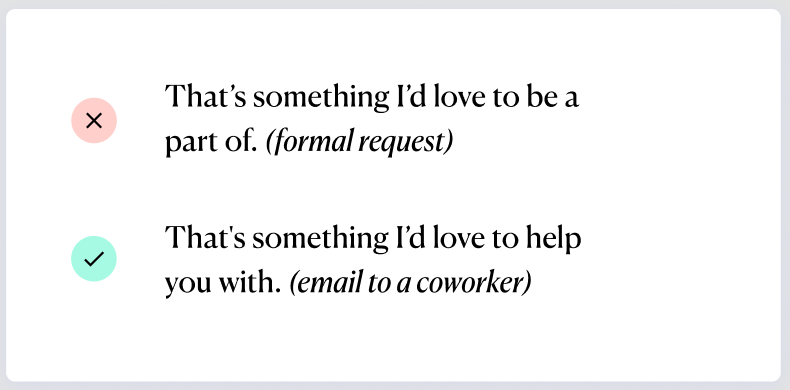

Here are six common grammar mistakes (and example sentences) to help you improve your writing:

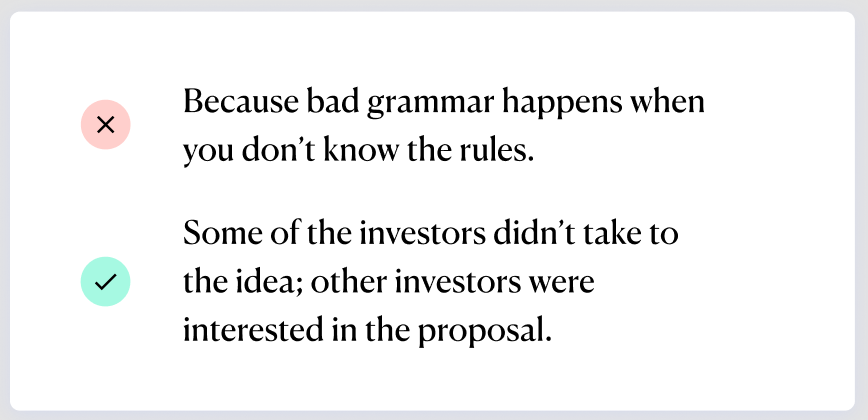

Semicolon use: Semicolons are typically used to connect related ideas — but often a new sentence (instead of a semicolon) is more fitting.

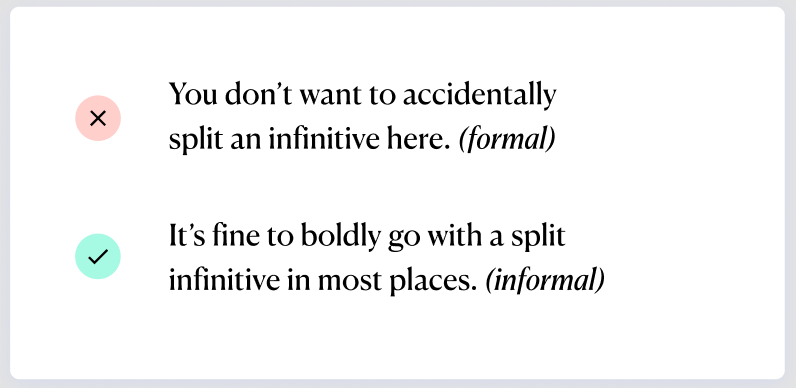

Ending a sentence with a preposition: Some used to consider it wrong to end with a preposition (e.g. to, of, with, at, from), but now it’s acceptable in most informal contexts.

Splitting infinitives: Avoid it in formal settings, otherwise, it’s fine.

Beginning a sentence with because: It’s ok as long as the sentence is complete.

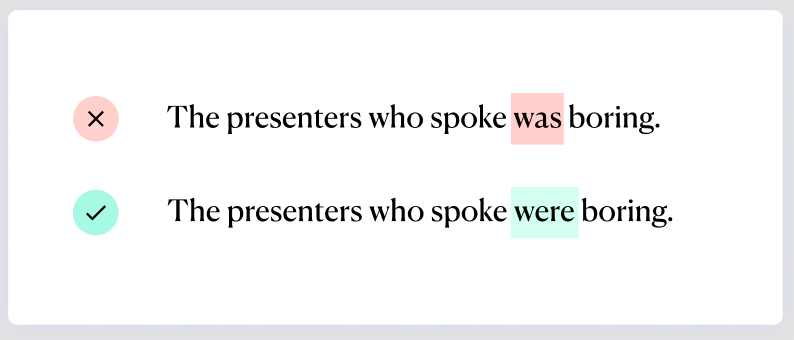

Subject-verb agreement: The verb of a sentence should match the subject’s plurality (or singularity).

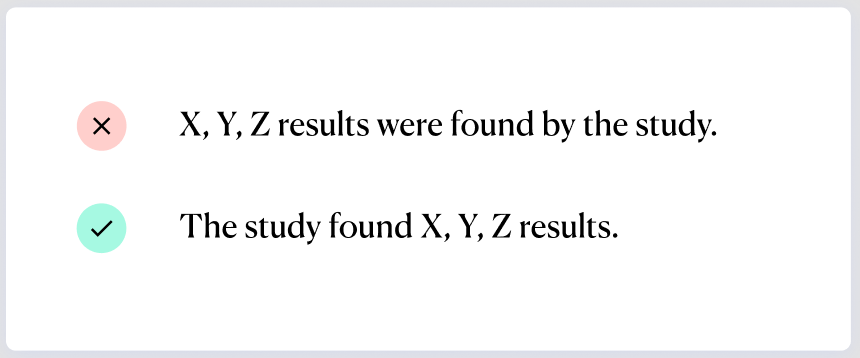

Passive voice: In general, use active voice — that means the subject acts upon the verb. In passive voice, the verb acts upon the subject, resulting in a weaker sentence.

1

a

: the study of the classes of words, their inflections (see inflection sense 2), and their functions and relations in the sentence

2

a

: the characteristic system of inflections (see inflection sense 2) and syntax of a language

b

: a system of rules that defines the grammatical structure of a language

3

b

: speech or writing evaluated according to its conformity to grammatical rules

appalled at the bad grammar of college students

4

: the principles or rules of an art, science, or technique

also

: a set of such principles or rules

Synonyms

Example Sentences

English grammar can be hard to master.

comparing English and Japanese grammar

comparing the grammars of English and Japanese

“Him and I went” is bad grammar.

I know some German, but my grammar isn’t very good.

Recent Examples on the Web

The feature allows users to invoke the AI to perform tasks such as autocompleting passages of text, brainstorming ideas, creating summaries of documents or simply fixing the spelling and grammar (which has suddenly become an ‘AI’ task in several.

—

English is the second language of most of her students, so vocabulary and grammar—the exact things QuilBot and Grammarly target—are still important assessment points.

—

But at this particular eruption of unrest in the spring of 2021—in Popayán, Colombia, a small city about 250 miles southwest of Bogotá—the basic grammar of protest and retaliation was about to take a harsh new shift.

—

These tools analyze the vocabulary and grammar content of lessons and help create a range of possible translations (so the app will accept learners’ responses when there are multiple correct ways to say something).

—

With access to artificial intelligence platforms that help with grammar, writing and more, teachers and kids alike must learn how to work with it to prepare for the future, said Culatta, whose organization offers training for teachers on using AI in classrooms.

—

Watch for spelling and grammar.

—

Maybe just a spelling or grammar check.

—

Benbow had produced the Black Language Podcast, about slang terms, grammar, and linguistics.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘grammar.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Etymology

Middle English gramere, from Anglo-French gramaire, modification of Latin grammatica, from Greek grammatikē, from feminine of grammatikos of letters, from grammat-, gramma — more at gram

First Known Use

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1a

Time Traveler

The first known use of grammar was

in the 14th century

Dictionary Entries Near grammar

Cite this Entry

“Grammar.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/grammar. Accessed 14 Apr. 2023.

Share

More from Merriam-Webster on grammar

Last Updated:

8 Apr 2023

— Updated example sentences

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged