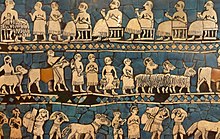

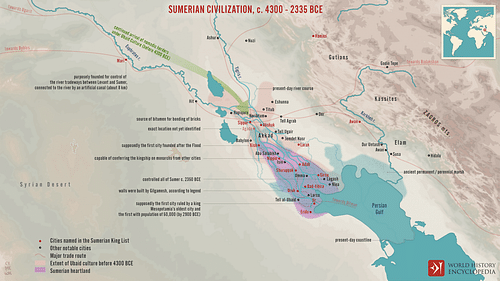

The ancient Sumerians of Mesopotamia were the oldest civilization in the world, beginning about 4000 BCE.

A civilization (UK English: civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of the state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

Civilizations are additionally characterized by other features, including agriculture, architecture, infrastructure, technological advancement, taxation, regulation, and specialization of labour.[3][4][5][7][8][9]

Historically, a civilization has often been understood as a larger and «more advanced» culture, in implied contrast to smaller, supposedly less advanced cultures.[2][4][5][10] In this broad sense, a civilization contrasts with non-centralized tribal societies, including the cultures of nomadic pastoralists, Neolithic societies, or hunter-gatherers; however, sometimes it also contrasts with the cultures found within civilizations themselves. Civilizations are organized densely-populated settlements divided into hierarchical social classes with a ruling elite and subordinate urban and rural populations, which engage in intensive agriculture, mining, small-scale manufacture and trade. Civilization concentrates power, extending human control over the rest of nature, including over other human beings.[11]

Civilization, as its etymology suggests, is a concept originally associated with towns and cities. The earliest emergence of civilizations is generally connected with the final stages of the Neolithic Revolution in West Asia, culminating in the relatively rapid process of urban revolution and state formation, a political development associated with the appearance of a governing elite.

History of the concept[edit]

The English word civilization comes from the 16th-century French civilisé («civilized»), from Latin civilis («civil»), related to civis («citizen») and civitas («city»).[12] The fundamental treatise is Norbert Elias’s The Civilizing Process (1939), which traces social mores from medieval courtly society to the Early Modern period.[13] In The Philosophy of Civilization (1923), Albert Schweitzer outlines two opinions: one purely material and the other material and ethical. He said that the world crisis was from humanity losing the ethical idea of civilization, «the sum total of all progress made by man in every sphere of action and from every point of view in so far as the progress helps towards the spiritual perfecting of individuals as the progress of all progress».[14]

Related words like «civility» developed in the mid-16th century. The abstract noun «civilization», meaning «civilized condition», came in the 1760s, again from French. The first known use in French is in 1757, by Victor de Riqueti, marquis de Mirabeau, and the first use in English is attributed to Adam Ferguson, who in his 1767 Essay on the History of Civil Society wrote, «Not only the individual advances from infancy to manhood but the species itself from rudeness to civilisation».[15] The word was therefore opposed to barbarism or rudeness, in the active pursuit of progress characteristic of the Age of Enlightenment.

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, during the French Revolution, «civilization» was used in the singular, never in the plural, and meant the progress of humanity as a whole. This is still the case in French.[16] The use of «civilizations» as a countable noun was in occasional use in the 19th century,[17] but has become much more common in the later 20th century, sometimes just meaning culture (itself in origin an uncountable noun, made countable in the context of ethnography).[18] Only in this generalized sense does it become possible to speak of a «medieval civilization», which in Elias’s sense would have been an oxymoron.

Already in the 18th century, civilization was not always seen as an improvement. One historically important distinction between culture and civilization is from the writings of Rousseau, particularly his work about education, Emile. Here, civilization, being more rational and socially driven, is not fully in accord with human nature, and «human wholeness is achievable only through the recovery of or approximation to an original discursive or prerational natural unity» (see noble savage). From this, a new approach was developed, especially in Germany, first by Johann Gottfried Herder and later by philosophers such as Kierkegaard and Nietzsche. This sees cultures as natural organisms, not defined by «conscious, rational, deliberative acts», but a kind of pre-rational «folk spirit». Civilization, in contrast, though more rational and more successful in material progress, is unnatural and leads to «vices of social life» such as guile, hypocrisy, envy and avarice.[16] In World War II, Leo Strauss, having fled Germany, argued in New York that this opinion of civilization was behind Nazism and German militarism and nihilism.[19]

Characteristics[edit]

Social scientists such as V. Gordon Childe have named a number of traits that distinguish a civilization from other kinds of society.[22] Civilizations have been distinguished by their means of subsistence, types of livelihood, settlement patterns, forms of government, social stratification, economic systems, literacy and other cultural traits. Andrew Nikiforuk argues that «civilizations relied on shackled human muscle. It took the energy of slaves to plant crops, clothe emperors, and build cities» and considers slavery to be a common feature of pre-modern civilizations.[23]

All civilizations have depended on agriculture for subsistence, with the possible exception of some early civilizations in Peru which may have depended upon maritime resources.[24][25]

The traditional «surplus model» postulates that cereal farming results in accumulated storage and a surplus of food, particularly when people use intensive agricultural techniques such as artificial fertilization, irrigation and crop rotation. It is possible but more difficult to accumulate horticultural production, and so civilizations based on horticultural gardening have been very rare.[26] Grain surpluses have been especially important because grain can be stored for a long time.

Research from the Journal of Political Economy contradicts the surplus model. It postulates that horticultural gardening was more productive than cereal farming. However, only cereal farming produced civilization because of the appropriability of yearly harvest. Rural populations that could only grow cereals could be taxed allowing for a taxing elite and urban development. This also had a negative effect on rural population, increasing relative agricultural output per farmer. Farming efficiency created food surplus and sustained the food surplus through decreasing rural population growth in favour of urban growth. Suitability of highly productive roots and tubers was in fact a curse of plenty, which prevented the emergence of states and impeded economic development. [27][28]

A surplus of food permits some people to do things besides producing food for a living: early civilizations included soldiers, artisans, priests and priestesses, and other people with specialized careers. A surplus of food results in a division of labour and a more diverse range of human activity, a defining trait of civilizations. However, in some places hunter-gatherers have had access to food surpluses, such as among some of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest and perhaps during the Mesolithic Natufian culture. It is possible that food surpluses and relatively large scale social organization and division of labour predates plant and animal domestication.[29]

Civilizations have distinctly different settlement patterns from other societies. The word «civilization» is sometimes defined as «‘living in cities‘».[30] Non-farmers tend to gather in cities to work and to trade.

Compared with other societies, civilizations have a more complex political structure, namely the state.[31] State societies are more stratified

[32] than other societies; there is a greater difference among the social classes. The ruling class, normally concentrated in the cities, has control over much of the surplus and exercises its will through the actions of a government or bureaucracy. Morton Fried, a conflict theorist and Elman Service, an integration theorist, have classified human cultures based on political systems and social inequality. This system of classification contains four categories[33]

- Hunter-gatherer bands, which are generally egalitarian.[34]

- Horticultural/pastoral societies in which there are generally two inherited social classes; chief and commoner.

- Highly stratified structures, or chiefdoms, with several inherited social classes: king, noble, freemen, serf and slave.

- Civilizations, with complex social hierarchies and organized, institutional governments.[35]

Economically, civilizations display more complex patterns of ownership and exchange than less organized societies. Living in one place allows people to accumulate more personal possessions than nomadic people. Some people also acquire landed property, or private ownership of the land. Because a percentage of people in civilizations do not grow their own food, they must trade their goods and services for food in a market system, or receive food through the levy of tribute, redistributive taxation, tariffs or tithes from the food producing segment of the population. Early human cultures functioned through a gift economy supplemented by limited barter systems. By the early Iron Age, contemporary civilizations developed money as a medium of exchange for increasingly complex transactions. In a village, the potter makes a pot for the brewer and the brewer compensates the potter by giving him a certain amount of beer. In a city, the potter may need a new roof, the roofer may need new shoes, the cobbler may need new horseshoes, the blacksmith may need a new coat and the tanner may need a new pot. These people may not be personally acquainted with one another and their needs may not occur all at the same time. A monetary system is a way of organizing these obligations to ensure that they are fulfilled. From the days of the earliest monetarized civilizations, monopolistic controls of monetary systems have benefited the social and political elites.

The transition from simpler to more complex economies does not necessarily mean an improvement in the living standards of the populace. For example, although the Middle Ages is often portrayed as an era of decline from the Roman Empire, studies have shown that the average stature of males in the Middle Ages (c. 500 to 1500 CE) was greater than it was for males during the preceding Roman Empire and the succeeding Early Modern Period (c. 1500 to 1800 CE).[36][37] Also, the Plains Indians of North America in the 19th century were taller than their «civilized» American and European counterparts. The average stature of a population is a good measurement of the adequacy of its access to necessities, especially food, and its freedom from disease.[38]

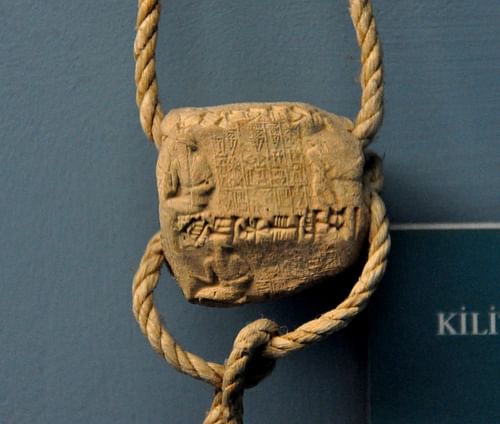

Writing, developed first by people in Sumer, is considered a hallmark of civilization and «appears to accompany the rise of complex administrative bureaucracies or the conquest state».[39] Traders and bureaucrats relied on writing to keep accurate records. Like money, the writing was necessitated by the size of the population of a city and the complexity of its commerce among people who are not all personally acquainted with each other. However, writing is not always necessary for civilization, as shown by the Inca civilization of the Andes, which did not use writing at all but except for a complex recording system consisting of knotted strings of different lengths and colors: the «Quipus», and still functioned as a civilized society.

Aided by their division of labour and central government planning, civilizations have developed many other diverse cultural traits. These include organized religion, development in the arts, and countless new advances in science and technology.

Throughout history, successful civilizations have spread, taking over more and more territory, and assimilating more and more previously uncivilized people. Nevertheless, some tribes or people remain uncivilized even to this day. These cultures are called by some «primitive», a term that is regarded by others as pejorative. «Primitive» implies in some way that a culture is «first» (Latin = primus), that it has not changed since the dawn of humanity, though this has been demonstrated not to be true. Specifically, as all of today’s cultures are contemporaries, today’s so-called primitive cultures are in no way antecedent to those we consider civilized. Anthropologists today use the term «non-literate» to describe these peoples.

Civilization has been spread by colonization, invasion, religious conversion, the extension of bureaucratic control and trade, and by introducing agriculture and writing to non-literate peoples. Some non-civilized people may willingly adapt to civilized behaviour. But civilization is also spread by the technical, material and social dominance that civilization engenders.

Assessments of what level of civilization a polity has reached are based on comparisons of the relative importance of agricultural as opposed to trading or manufacturing capacities, the territorial extensions of its power, the complexity of its division of labour, and the carrying capacity of its urban centres. Secondary elements include a developed transportation system, writing, standardized measurement, currency, contractual and tort-based legal systems, art, architecture, mathematics, scientific understanding, metallurgy, political structures, and organized religion.

Traditionally, polities that managed to achieve notable military, ideological and economic power defined themselves as «civilized» as opposed to other societies or human groupings outside their sphere of influence – calling the latter barbarians, savages, and primitives.

Cultural identity[edit]

«Civilization» can also refer to the culture of a complex society, not just the society itself. Every society, civilization or not, has a specific set of ideas and customs, and a certain set of manufactures and arts that make it unique. Civilizations tend to develop intricate cultures, including a state-based decision-making apparatus, a literature, professional art, architecture, organized religion and complex customs of education, coercion and control associated with maintaining the elite.

The intricate culture associated with civilization has a tendency to spread to and influence other cultures, sometimes assimilating them into the civilization (a classic example being Chinese civilization and its influence on nearby civilizations such as Korea, Japan and Vietnam). Many civilizations are actually large cultural spheres containing many nations and regions. The civilization in which someone lives is that person’s broadest cultural identity.[citation needed]

It is precisely the protection of this cultural identity that is becoming increasingly important nationally and internationally. According to international law, the United Nations and UNESCO try to set up and enforce relevant rules. The aim is to preserve the cultural heritage of humanity and also the cultural identity, especially in the case of war and armed conflict. According to Karl von Habsburg, President of Blue Shield International, the destruction of cultural assets is also part of psychological warfare. The target of the attack is often the opponent’s cultural identity, which is why symbolic cultural assets become a main target. It is also intended to destroy the particularly sensitive cultural memory (museums, archives, monuments, etc.), the grown cultural diversity, and the economic basis (such as tourism) of a state, region or community.[40][41][42][43][44][45]

Many historians have focused on these broad cultural spheres and have treated civilizations as discrete units. Early twentieth-century philosopher Oswald Spengler,[46] uses the German word Kultur, «culture», for what many call a «civilization». Spengler believed a civilization’s coherence is based on a single primary cultural symbol. Cultures experience cycles of birth, life, decline, and death, often supplanted by a potent new culture, formed around a compelling new cultural symbol. Spengler states civilization is the beginning of the decline of a culture as «the most external and artificial states of which a species of developed humanity is capable».[46]

This «unified culture» concept of civilization also influenced the theories of historian Arnold J. Toynbee in the mid-twentieth century. Toynbee explored civilization processes in his multi-volume A Study of History, which traced the rise and, in most cases, the decline of 21 civilizations and five «arrested civilizations». Civilizations generally declined and fell, according to Toynbee, because of the failure of a «creative minority», through moral or religious decline, to meet some important challenge, rather than mere economic or environmental causes.

Samuel P. Huntington defines civilization as «the highest cultural grouping of people and the broadest level of cultural identity people have short of that which distinguishes humans from other species».[47]

Complex systems[edit]

Another group of theorists, making use of systems theory, looks at a civilization as a complex system, i.e., a framework by which a group of objects can be analysed that work in concert to produce some result. Civilizations can be seen as networks of cities that emerge from pre-urban cultures and are defined by the economic, political, military, diplomatic, social and cultural interactions among them. Any organization is a complex social system and a civilization is a large organization. Systems theory helps guard against superficial and misleading analogies in the study and description of civilizations.

Systems theorists look at many types of relations between cities, including economic relations, cultural exchanges and political/diplomatic/military relations. These spheres often occur on different scales. For example, trade networks were, until the nineteenth century, much larger than either cultural spheres or political spheres. Extensive trade routes, including the Silk Road through Central Asia and Indian Ocean sea routes linking the Roman Empire, Persian Empire, India and China, were well established 2000 years ago when these civilizations scarcely shared any political, diplomatic, military, or cultural relations. The first evidence of such long-distance trade is in the ancient world. During the Uruk period, Guillermo Algaze has argued that trade relations connected Egypt, Mesopotamia, Iran and Afghanistan.[48] Resin found later in the Royal Cemetery at Ur is suggested was traded northwards from Mozambique.

Many theorists argue that the entire world has already become integrated into a single «world system», a process known as globalization. Different civilizations and societies all over the globe are economically, politically, and even culturally interdependent in many ways. There is debate over when this integration began, and what sort of integration – cultural, technological, economic, political, or military-diplomatic – is the key indicator in determining the extent of a civilization. David Wilkinson has proposed that economic and military-diplomatic integration of the Mesopotamian and Egyptian civilizations resulted in the creation of what he calls the «Central Civilization» around 1500 BCE.[49] Central Civilization later expanded to include the entire Middle East and Europe, and then expanded to a global scale with European colonization, integrating the Americas, Australia, China and Japan by the nineteenth century. According to Wilkinson, civilizations can be culturally heterogeneous, like the Central Civilization, or homogeneous, like the Japanese civilization. What Huntington calls the «clash of civilizations» might be characterized by Wilkinson as a clash of cultural spheres within a single global civilization. Others point to the Crusading movement as the first step in globalization. The more conventional viewpoint is that networks of societies have expanded and shrunk since ancient times, and that the current globalized economy and culture is a product of recent European colonialism.[citation needed]

History[edit]

The notion of human history as a succession of «civilizations» is an entirely modern one. In the European Age of Discovery, emerging Modernity was put into stark contrast with the Neolithic and Mesolithic stage of the cultures of many of the peoples they encountered.[50][obsolete source]

Urban Revolution[edit]

At first, the Neolithic was associated with shifting subsistence cultivation, where continuous farming led to the depletion of soil fertility resulting in the requirement to cultivate fields further and further removed from the settlement, eventually compelling the settlement itself to move. In major semi-arid river valleys, annual flooding renewed soil fertility every year, with the result that population densities could rise significantly.

This encouraged a secondary products revolution in which people used domesticated animals not just for meat, but also for milk, wool, manure and pulling ploughs and carts – a development that spread through the Eurasian Oecumene.

The Natufian culture in the Levantine corridor is the earliest case of the Neolithic Revolution, with the planting of cereal crops attested from c.11,000 BC.[51][52] The earliest neolithic technology and lifestyle were established first in Western Asia (for example at Göbekli Tepe, from about 9,130 BCE), later in the Yellow River and Yangtze basins in China (for example the Peiligang and Pengtoushan cultures), and from these cores spread across Eurasia. Mesopotamia is the site of the earliest civilizations developing from 7,400 years ago. This area has been identified as having «inspired some of the most important developments in human history including the invention of the wheel, the building of the earliest cities and the development of the written cursive script».[53]

Similar pre-civilized «neolithic revolutions» also began independently from 7,000 BCE in northwestern South America (the Norte Chico civilization)[54] and Mesoamerica.[55] The Black Sea area is a cradle of the European civilization. The site of Solnitsata (5500 BC — 4200 BC) is believed to be the oldest town in Europe — prehistoric fortified (walled) stone settlement (prehistoric city).[56][57][58][59] The first gold artifacts in the world appear from the 4th millennium BC, such as those found in a burial site from 4569 to 4340 BC and one of the most important archaeological sites in world prehistory – the Varna Necropolis near Lake Varna in Bulgaria, thought to be the earliest «well-dated» find of gold artifacts.[60]

The 8.2 Kiloyear Arid Event and the 5.9 Kiloyear Interpluvial saw the drying out of semiarid regions and a major spread of deserts.[61] This climate change shifted the cost-benefit ratio of endemic violence between communities, which saw the abandonment of unwalled village communities and the appearance of walled cities, associated with the first civilizations.

This «urban revolution» marked the beginning of the accumulation of transferable surpluses, which helped economies and cities develop. It was associated with the state monopoly of violence, the appearance of a soldier class and endemic warfare, the rapid development of hierarchies, and the appearance of human sacrifice.[62]

The civilized urban revolution in turn was dependent upon the development of sedentism, the domestication of grains, plants and animals, the permanence of settlements and development of lifestyles that facilitated economies of scale and accumulation of surplus production by certain social sectors. The transition from complex cultures to civilizations, while still disputed, seems to be associated with the development of state structures, in which power was further monopolized by an elite ruling class[63] who practiced human sacrifice.[62]

Towards the end of the Neolithic period, various elitist Chalcolithic civilizations began to rise in various «cradles» from around 3600 BCE beginning with Mesopotamia, expanding into large-scale kingdoms and empires in the course of the Bronze Age (Akkadian Empire, Indus Valley Civilization, Old Kingdom of Egypt, Neo-Sumerian Empire, Middle Assyrian Empire, Babylonian Empire, Hittite Empire, and to some degree the territorial expansions of the Elamites, Hurrians, Amorites and Ebla).

A later development took place independently in the Pre-Columbian Americas. Urbanization in the Norte Chico civilization in coastal Peru emerged about 3200 BCE;[64] the oldest known Mayan city, located in Guatemala, dates to about 750 BCE.[65] and Teotihuacan in Mexico was one of the largest cities in the world in 350 CE with a population of about 125,000.[66]

Axial Age[edit]

The Bronze Age collapse was followed by the Iron Age around 1200 BCE, during which a number of new civilizations emerged, culminating in a period from the 8th to the 3rd century BCE which Karl Jaspers termed the Axial Age, presented as a critical transitional phase leading to classical civilization.[67]

Modernity[edit]

A major technological and cultural transition to modernity began approximately 1500 CE in Western Europe, and from this beginning new approaches to science and law spread rapidly around the world, incorporating earlier cultures into the technological and industrial society of the present.[62][68]

Fall of civilizations[edit]

Civilizations are traditionally understood as ending in one of two ways; either through incorporation into another expanding civilization (e.g. as Ancient Egypt was incorporated into Hellenistic Greek, and subsequently Roman civilizations), or by collapsing and reverting to a simpler form of living, as happens in so-called Dark Ages.[69]

There have been many explanations put forward for the collapse of civilization. Some focus on historical examples, and others on general theory.

- Ibn Khaldūn’s Muqaddimah influenced theories of the analysis, growth, and decline of the Islamic civilization.[70] He suggested repeated invasions from nomadic peoples limited development and led to social collapse.

- Edward Gibbon’s work The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire is a well-known and detailed analysis of the fall of Roman civilization. Gibbon suggested the final act of the collapse of Rome was the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 CE. For Gibbon, «The decline of Rome was the natural and inevitable effect of immoderate greatness. Prosperity ripened the principle of decay; the cause of the destruction multiplied with the extent of conquest; and, as soon as time or accident had removed the artificial supports, the stupendous fabric yielded to the pressure of its own weight. The story of the ruin is simple and obvious; and instead of inquiring why the Roman Empire was destroyed, we should rather be surprised that it has subsisted for so long».[71]

- Theodor Mommsen in his History of Rome suggested Rome collapsed with the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE and he also tended towards a biological analogy of «genesis», «growth», «senescence», «collapse» and «decay».

- Oswald Spengler, in his Decline of the West rejected Petrarch’s chronological division, and suggested that there had been only eight «mature civilizations». Growing cultures, he argued, tend to develop into imperialistic civilizations, which expand and ultimately collapse, with democratic forms of government ushering in plutocracy and ultimately imperialism.

- Arnold J. Toynbee in his A Study of History suggested that there had been a much larger number of civilizations, including a small number of arrested civilizations, and that all civilizations tended to go through the cycle identified by Mommsen. The cause of the fall of a civilization occurred when a cultural elite became a parasitic elite, leading to the rise of internal and external proletariats.

- Joseph Tainter in The Collapse of Complex Societies suggested that there were diminishing returns to complexity, due to which, as states achieved a maximum permissible complexity, they would decline when further increases actually produced a negative return. Tainter suggested that Rome achieved this figure in the 2nd century CE.

- Jared Diamond in his 2005 book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed suggests five major reasons for the collapse of 41 studied cultures: environmental damage, such as deforestation and soil erosion; climate change; dependence upon long-distance trade for needed resources; increasing levels of internal and external violence, such as war or invasion; and societal responses to internal and environmental problems.

- Peter Turchin in his Historical Dynamics and Andrey Korotayev et al. in their Introduction to Social Macrodynamics, Secular Cycles, and Millennial Trends suggest a number of mathematical models describing collapse of agrarian civilizations. For example, the basic logic of Turchin’s «fiscal-demographic» model can be outlined as follows: during the initial phase of a sociodemographic cycle we observe relatively high levels of per capita production and consumption, which leads not only to relatively high population growth rates, but also to relatively high rates of surplus production. As a result, during this phase the population can afford to pay taxes without great problems, the taxes are quite easily collectible, and the population growth is accompanied by the growth of state revenues. During the intermediate phase, the increasing population growth leads to the decrease of per capita production and consumption levels, it becomes more and more difficult to collect taxes, and state revenues stop growing, whereas the state expenditures grow due to the growth of the population controlled by the state. As a result, during this phase the state starts experiencing considerable fiscal problems. During the final pre-collapse phases the overpopulation leads to further decrease of per capita production, the surplus production further decreases, state revenues shrink, but the state needs more and more resources to control the growing (though with lower and lower rates) population. Eventually this leads to famines, epidemics, state breakdown, and demographic and civilization collapse (Peter Turchin. Historical Dynamics. Princeton University Press, 2003:121–127; Andrey Korotayev et al. Secular Cycles and Millennial Trends. Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences, 2006).

- Peter Heather argues in his book The Fall of the Roman Empire: a New History of Rome and the Barbarians[72] that this civilization did not end for moral or economic reasons, but because centuries of contact with barbarians across the frontier generated its own nemesis by making them a more sophisticated and dangerous adversary. The fact that Rome needed to generate ever greater revenues to equip and re-equip armies that were for the first time repeatedly defeated in the field, led to the dismemberment of the Empire. Although this argument is specific to Rome, it can also be applied to the Asiatic Empire of the Egyptians, to the Han and Tang dynasties of China, to the Muslim Abbasid Caliphate and others.

- Bryan Ward-Perkins, in his book The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization,[73] argues from mostly archaeological evidence that the collapse of Roman civilization in western Europe had deleterious impacts on the living standards of the population, unlike some historians who downplay this. The collapse of complex society meant that even basic plumbing for the elite disappeared from the continent for 1,000 years. Similar impacts have been postulated for the Dark Age after the Late Bronze Age collapse in the Eastern Mediterranean, the collapse of the Maya, on Easter Island and elsewhere.

- Arthur Demarest argues in Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization,[74] using a holistic perspective to the most recent evidence from archeology, paleoecology, and epigraphy, that no one explanation is sufficient but that a series of erratic, complex events, including loss of soil fertility, drought and rising levels of internal and external violence led to the disintegration of the courts of Mayan kingdoms, which began a spiral of decline and decay. He argues that the collapse of the Maya has lessons for civilization today.

- Jeffrey A. McNeely has recently suggested that «a review of historical evidence shows that past civilizations have tended to over-exploit their forests, and that such abuse of important resources has been a significant factor in the decline of the over-exploiting society».[75]

- Thomas Homer-Dixon in The Upside of Down: Catastrophe, Creativity, and the Renewal of Civilization, where he considers that the fall in the energy return on investments. The energy expended to energy yield ratio is central to limiting the survival of civilizations. The degree of social complexity is associated strongly, he suggests, with the amount of disposable energy environmental, economic and technological systems allow. When this amount decreases civilizations either have to access new energy sources or they will collapse.

- Feliks Koneczny in his work «On the Plurality of Civilizations» calls his study the science on civilizations. He asserts that civilizations fall not because they must or there exist some cyclical or a «biological» life span and that there stil exist two ancient civilizations – Brahmin-Hindu and Chinese – which are not ready to fall any time soon. Koneczny claimed that civilizations cannot be mixed into hybrids, an inferior civilization when given equal rights within a highly developed civilization will overcome it. One of Koneczny’s claims in his study on civilizations is that «a person cannot be civilized in two or more ways» without falling into what he calls an «abcivilized state» (as in abnormal). He also stated that when two or more civilizations exist next to one another and as long as they are vital, they will be in an existential combat imposing its own «method of organizing social life» upon the other.[76] Absorbing alien «method of organizing social life» that is civilization and giving it equal rights yields a process of decay and decomposition.

Future[edit]

Political scientist Samuel Huntington has argued that the defining characteristic of the 21st century will be a clash of civilizations.[77] According to Huntington, conflicts between civilizations will supplant the conflicts between nation-states and ideologies that characterized the 19th and 20th centuries. These views have been strongly challenged by others like Edward Said, Muhammed Asadi and Amartya Sen.[78] Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris have argued that the «true clash of civilizations» between the Muslim world and the West is caused by the Muslim rejection of the West’s more liberal sexual values, rather than a difference in political ideology, although they note that this lack of tolerance is likely to lead to an eventual rejection of (true) democracy.[79] In Identity and Violence Sen questions if people should be divided along the lines of a supposed «civilization», defined by religion and culture only. He argues that this ignores the many others identities that make up people and leads to a focus on differences.

Cultural Historian Morris Berman argues in Dark Ages America: the End of Empire that in the corporate consumerist United States, the very factors that once propelled it to greatness―extreme individualism, territorial and economic expansion, and the pursuit of material wealth―have pushed the United States across a critical threshold where collapse is inevitable. Politically associated with over-reach, and as a result of the environmental exhaustion and polarization of wealth between rich and poor, he concludes the current system is fast arriving at a situation where continuation of the existing system saddled with huge deficits and a hollowed-out economy is physically, socially, economically and politically impossible.[80] Although developed in much more depth, Berman’s thesis is similar in some ways to that of Urban Planner, Jane Jacobs who argues that the five pillars of United States culture are in serious decay: community and family; higher education; the effective practice of science; taxation and government; and the self-regulation of the learned professions. The corrosion of these pillars, Jacobs argues, is linked to societal ills such as environmental crisis, racism and the growing gulf between rich and poor.[81]

Cultural critic and author Derrick Jensen argues that modern civilization is directed towards the domination of the environment and humanity itself in an intrinsically harmful, unsustainable, and self-destructive fashion.[82] Defending his definition both linguistically and historically, he defines civilization as «a culture… that both leads to and emerges from the growth of cities», with «cities» defined as «people living more or less permanently in one place in densities high enough to require the routine importation of food and other necessities of life».[83] This need for civilizations to import ever more resources, he argues, stems from their over-exploitation and diminution of their own local resources. Therefore, civilizations inherently adopt imperialist and expansionist policies and, to maintain these, highly militarized, hierarchically structured, and coercion-based cultures and lifestyles.

The Kardashev scale classifies civilizations based on their level of technological advancement, specifically measured by the amount of energy a civilization is able to harness. The scale is only hypothetical, but it puts energy consumption in a cosmic perspective. The Kardashev scale makes provisions for civilizations far more technologically advanced than any currently known to exist.

Non-human civilizations[edit]

The current scientific consensus is that human beings are the only animal species with the cognitive ability to create civilizations that has emerged on Earth. A recent thought experiment, the silurian hypothesis, however, considers whether it would «be possible to detect an industrial civilization in the geological record» given the paucity of geological information about eras before the quaternary.[84]

Astronomers speculate about the existence of communicating intelligent civilizations within and beyond the Milky Way galaxy, usually using variants of the Drake equation.[85] They also conduct searches for such intelligences – such as for technological traces, called «technosignatures».[86] The proposed proto-scientific field «xenoarchaeology» is concerned with the study of artifact remains of non-human civilizations to reconstruct and interpret past lives of alien societies if such get discovered and confirmed scientifically.[87][88]

See also[edit]

- Anarcho-primitivism

- Barbarian

- Christendom

- Civilizing mission

- Civilization state

- Colony

- Cradle of civilization

- Culture

- Future Shock

- Human history

- Intermediate Region

- Kardashev scale

- Law of Life

- List of medieval great powers

- Manichaeism

- Muslim world

- New Tribalism

- Outline of culture

- Role of Christianity in civilization

- Search for extraterrestrial intelligence

- Sedentism

- Society

- Western culture

- World population

- Zoroastrianism

References[edit]

- ^ «Chronology». Digital Egypt for Universities. University College London. 2000. Archived from the original on 16 March 2008.

- ^ a b Adams, Robert McCormick (1966). The Evolution of Urban Society. Transaction Publishers. p. 13. ISBN 9780202365947. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ a b Haviland, William; et al. (2013). Cultural Anthropology: The Human Challenge. Cengage Learning. p. 250. ISBN 978-1285675305. Archived from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Wright, Ronald (2004). A Short History anthropological. ISBN 9780887847066.

- ^ a b c Llobera, Josep (2003). An Invitation to Anthropology. Berghahn Books. pp. 136–137. ISBN 9781571815972. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (2001). Civilizations: Culture, Ambition, and the Transformation of Nature. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780743216500. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ a b Boyden, Stephen Vickers (2004). The Biology of Civilisation. UNSW Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9780868407661. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ a b Solms-Laubach, Franz (2007). Nietzsche and Early German and Austrian Sociology. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 115, 117, and 212. ISBN 9783110181098. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ a b AbdelRahim, Layla (2015). Children’s literature, domestication and social foundation : narratives of civilization and wilderness. New York. p. 8. ISBN 9780415661102. OCLC 897810261.

- ^ Bolesti, Maria (2013). Barbarism and Its Discontents. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804785372. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Mann, Michael (1986). The Sources of Social Power. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–41.

- ^ Sullivan, Larry E. (2009). The SAGE Glossary of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. SAGE Publications. p. 73. ISBN 9781412951432. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ It remains the most influential sociological study of the topic, spawning its own body of secondary literature. Notably, Hans Peter Duerr attacked it in a major work (3,500 pages in five volumes, published 1988–2002). Elias, at the time a nonagenarian, was still able to respond to the criticism the year before his death. In 2002, Duerr was himself criticized by Michael Hinz’s Der Zivilisationsprozeß: Mythos oder Realität (2002), saying that his criticism amounted to hateful defamation of Elias, through excessive standards of political correctness. Der Spiegel 40/2002 Archived 28 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Albert Schweitzer. The Philosophy of Civilization, trans. C.T. Campion (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1987), p. 91.

- ^ Cited after Émile Benveniste, Civilisation. Contribution à l’histoire du mot (Civilisation. Contribution to the history of the word), 1954, published in Problèmes de linguistique générale, Éditions Gallimard, 1966, pp. 336–345 (translated by Mary Elizabeth Meek as Problems in general linguistics, 2 vols., 1971).

- ^ a b Velkley, Richard (2002). «The Tension in the Beautiful: On Culture and Civilization in Rousseau and German Philosophy». Being after Rousseau: Philosophy and Culture in Question. The University of Chicago Press. pp. 11–30.

- ^ E.g. in the title A narrative of the loss of the Winterton East Indiaman wrecked on the coast of Madagascar in 1792; and of the sufferings connected with that event. To which is subjoined a short account of the natives of Madagascar, with suggestions as to their civilizations by J. Hatchard, L.B. Seeley and T. Hamilton, London, 1820.

- ^ «Civilization» (1974), Encyclopædia Britannica 15th ed. Vol. II, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 956. Retrieved 25 August 2007. Using the terms «civilization» and «culture» as equivalents are controversial[clarification needed] and generally rejected so that for example some types of culture are not normally described as civilizations.

- ^ «On German Nihilism» (1999, originally a 1941 lecture), Interpretation 26, no. 3 edited by David Janssens and Daniel Tanguay.

- ^ «Athens». Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

Ancient Greek Athenai, historic city and capital of Greece. Many of classical civilization’s intellectual and artistic ideas originated there, and the city is generally considered to be the birthplace of Western civilization

- ^ Brown, Thomas J. (1975). «The Athenian furies : observations on the major factors effecting politics in modern Greece, 1973-1974». Virtual Press.

Greece is a picturesque country on the southern tip of the Balkan Peninsula straddling the always-blue Agean, Ionian and Adriatic Seas. Considered by many to be the cradle of Western Civilization and the birthplace of democracy, her ancient past has long been the source and inspiration of Western thought.

- ^ Gordon Childe, V., What Happened in History (Penguin, 1942) and Man Makes Himself (Harmondsworth, 1951).

- ^ Nikiforuk, Andrew (2012). The Energy of Slaves: Oil and the new servitude. Greystone Books.

- ^ Moseley, Michael. «The Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization: An Evolving Hypothesis». The Hall of Ma’at. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ^ Moseley, Michael (1975). The Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization. Menlo Park: Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8465-4800-3.

- ^ Hadjikoumis; Angelos, Robinson; and Sarah Viner-Daniels (Eds) (2011), «Dynamics of Neolithisation in Europe: Studies in honour of Andrew Sherratt» (Oxbow Books)

- ^ Kiggins, Sheila. «Study sheds new light on the origin of civilization». Phys.org. Archived from the original on 18 April 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Mayshar, Joram; Moav, Omer; Pascali, Luigi (2022). «The Origin of the State: Land Productivity or Appropriability?». Journal of Political Economy. 130 (4): 1091–1144. doi:10.1086/718372. S2CID 244818703. Archived from the original on 17 April 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Mann, Charles C. (June 2011). «Göbekli Tepe». National Geographic. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ Tom Standage (2005), A History of the World in 6 Glasses, Walker & Company, 25.

- ^ Grinin, Leonid E; et al., eds. (2004). The Early State and its Alternatives and Analogues. Ichitel.

- ^ Bondarenko, Dmitri; et al. (2004). «Alternatives to Social Evolution». In Grinin, Leonid E; et al. (eds.). The Early State and its Alternatives and Analogues. Ichitel.

- ^ Bogucki, Peter (1999), «The Origins of Human Society» (Wiley Blackwell)

- ^ DeVore, Irven, and Lee, Richard (1999) «Man the Hunter» (Aldine)

- ^ Beck, Roger B.; Linda Black; Larry S. Krieger; Phillip C. Naylor; Dahia Ibo Shabaka (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, Ill.: McDougal Littell. ISBN 978-0-395-87274-1.

- ^ Steckel, Richard H. (4 January 2016). «New Light on the ‘Dark Ages’«. Social Science History. 28 (2): 211–229. doi:10.1017/S0145553200013134. S2CID 143128051.

- ^ Koepke, Nikola; Baten, Joerg (1 April 2005). «The biological standard of living in Europe during the last two millennia». European Review of Economic History. 9 (1): 61–95. doi:10.1017/S1361491604001388. hdl:10419/47594. JSTOR 41378413.

- ^ Leutwyler, Kristen. «American Plains Indians had Health and Height». Scientific American. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Pauketat, Timothy R. (2004). Ancient Cahokia and the Mississippians. Cambridge University Press. p. 169. ISBN 9780521520669.

- ^ Corine Wegener, Marjan Otter: Cultural Property at War: Protecting Heritage during Armed Conflict. In: The Getty Conservation Institute, Newsletter 23.1, Spring 2008.

- ^ Eden Stiffman: Cultural Preservation in Disasters, War Zones. Presents Big Challenges. In: The Chronicle Of Philanthropy, 11 May 2015.

- ^ Hans Haider Missbrauch von Kulturgütern ist strafbar. In: Wiener Zeitung, 29 June 2012.

- ^ «Karl von Habsburg auf Mission im Libanon» (in German). 28 April 2019. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ «The ICRC and the Blue Shield signed a Memorandum of Understanding, 26 February 2020». 26 February 2020. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ Friedrich Schipper: «Bildersturm: Die globalen Normen zum Schutz von Kulturgut greifen nicht» (German – The global norms for the protection of cultural property do not apply), In: Der Standard, 6 March 2015.

- ^ a b Spengler, Oswald, Decline of the West: Perspectives of World History (1919)

- ^ Huntington, Samuel P. (1997). The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Simon and Schuster. p. 43. ISBN 9781416561248. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Algaze, Guillermo, The Uruk World System: The Dynamics of Expansion of Early Mesopotamian Civilization (Second Edition, 2004) (ISBN 978-0-226-01382-4)

- ^ Wilkinson, David (Fall 1987). «Central Civilization». Comparative Civilizations Review. Vol. 17. pp. 31–59. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ Carneiro, Robert L. (21 August 1970). «A Theory of the Origin of the State». Science. 169 (3947): 733–738. doi:10.1126/science.169.3947.733. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17820299. S2CID 11536431. Archived from the original on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

Explicit theories of the origin of the state are relatively modern […] the age of exploration, by making Europeans aware that many peoples throughout the world lived, not in states, but in independent villages or tribes, made the state seem less natural, and thus more in need of explanation.

- ^ Moore, Andrew M. T.; Hillman, Gordon C.; Legge, Anthony J. (2000). Village on the Euphrates: From Foraging to Farming at Abu Hureyra.(Oxford University Press).

- ^ Hillman, Gordon; Hedges, Robert; Moore, Andrew; Colledge, Susan; Pettitt, Paul (27 July 2016). «New evidence of Lateglacial cereal cultivation at Abu Hureyra on the Euphrates». Holocene. 11 (4): 383–393.

- ^ Milton-Edwards, Beverley (May 2003). «Iraq, past, present and future: a thoroughly-modern mandate?». History & Policy. United Kingdom: History & Policy. Archived from the original on 8 December 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Haas, Jonathan; Creamer, Winifred; Ruiz, Alvaro (December 2004). «Dating the Late Archaic occupation of the Norte Chico region in Peru». Nature. 432 (7020): 1020–1023. Bibcode:2004Natur.432.1020H. doi:10.1038/nature03146. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15616561. S2CID 4426545.

- ^ Kennett, Douglas J.; Winterhalder, Bruce (2006). Behavioral Ecology and the Transition to Agriculture. University of California Press. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-0-520-24647-8. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ^ Maugh II, Thomas H. (1 November 2012). «Bulgarians find oldest European town, a salt production center». The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Survival of Information: the earliest prehistoric town in Europe

- ^ Squires, Nick (31 October 2012). «Archaeologists find Europe’s most prehistoric town». The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Nikolov, Vassil. «Salt, early complex society, urbanization: Provadia-Solnitsata (5500-4200 BC) (Abstract)» (PDF). Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ La Niece, Susan (senior metallurgist in the British Museum Department of Conservation and Scientific Research) (15 December 2009). Gold. Harvard University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-674-03590-4. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ De Meo, James (2nd Edition), «Saharasia»

- ^ a b c Watts, Joseph; Sheehan, Oliver; Atkinson, Quentin D.; Bulbulia, Joseph; Gray, Russell D. (4 April 2016). «Ritual human sacrifice promoted and sustained the evolution of stratified societies». Nature. 532 (7598): 228–231. Bibcode:2016Natur.532..228W. doi:10.1038/nature17159. PMID 27042932. S2CID 4450246.

- ^ Carniero, R.L. (Ed) (1967), «The Evolution of Society: Selections from Herbert Spencer’s Principles of Sociology», (Univ. of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1967), pp. 32–47, 63–96, 153–165.

- ^ Mann, Charles C. (2006) [2005]. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Vintage Books. pp. 199–212. ISBN 1-4000-3205-9.

- ^ Olmedo Vera, Bertina (1997). A. Arellano Hernández; et al. (eds.). The Mayas of the Classic Period. Mexico City, Mexico: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes (CONACULTA). p. 26 ISBN 978-970-18-3005-5.

- ^ Sanders, William T.; Webster, David (1988). «The Mesoamerican Urban Tradition». American Anthropologist. 90 (3): 521–546. doi:10.1525/aa.1988.90.3.02a00010. ISSN 0002-7294. JSTOR 678222.

- ^ Tarnas, Richard (1993). The Passion of the Western Mind: Understanding the Ideas that Have Shaped Our World View (Ballantine Books)

- ^ Ferguson, Niall (2011). Civilization.

- ^ Toynbee, Arnold (1965) «A Study of History» (OUP)

- ^ Massimo Campanini (2005), Studies on Ibn Khaldûn Archived 28 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Polimetrica s.a.s., p. 75

- ^ Gibbon, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, 2nd ed., vol. 4, ed. by J. B. Bury (London, 1909), pp. 173–174. Chapter XXXVIII: Reign Of Clovis. Part VI. General Observations On The Fall Of The Roman Empire In The West.

- ^ Peter J. Heather (1 December 2005). The Fall Of The Roman Empire: A New History Of Rome And The Barbarians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515954-7. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ Bryan Ward-Perkins (7 September 2006). The Fall of Rome: And the End of Civilization. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280728-1. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ Demarest, Arthur (9 December 2004). Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization. ISBN 978-0-521-53390-4.

- ^ McNeely, Jeffrey A. (1994) «Lessons of the past: Forests and Biodiversity» (Vol 3, No 1 1994. Biodiversity and Conservation)

- ^ Koneczny, Feliks (1962) On the Plurality of Civilizations, Posthumous English translation by Polonica Publications, London ASIN B0000CLABJ. Originally published in Polish, O Wielości Cywilizacyj, Gebethner & Wolff, Kraków 1935.

- ^ Huntington, Samuel P., The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, (Simon & Schuster, 1996)

- ^ Asadi, Muhammed (22 January 2007). «A Critique of Huntington’s «Clash of Civilizations»«. Selves and Others. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ^ Inglehart, Ronald; Pippa Norris (March–April 2003). «The True Clash of Civilizations». Global Policy Forum. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ^ Berman, Morris (2007), Dark Ages America: the End of Empire (W.W. Norton)

- ^ Jacobs, Jane (2005), Dark Age Ahead (Vintage)

- ^ Jensen, Derrick (2006), «Endgame: The Problem of Civilization», Vol 1 & Vol 2 (Seven Stories Press)

- ^ Jensen, Derrick (2006), «Endgame: The Problem of Civilization», Vol 1 (Seven Stories Press), p. 17

- ^ Schmidt, Gavin A.; Frank, Adam (10 April 2018). «The Silurian Hypothesis: Would it be possible to detect an industrial civilization in the geological record?». arXiv:1804.03748 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ Westby, Tom; Conselice, Christopher J. (15 June 2020). «The Astrobiological Copernican Weak and Strong Limits for Intelligent Life». The Astrophysical Journal. 896 (1): 58. arXiv:2004.03968. Bibcode:2020ApJ…896…58W. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab8225. S2CID 215415788.

- ^ Socas-Navarro, Hector; Haqq-Misra, Jacob; Wright, Jason T.; Kopparapu, Ravi; Benford, James; Davis, Ross; TechnoClimes 2020 workshop participants (1 May 2021). «Concepts for future missions to search for technosignatures». Acta Astronautica. 182: 446–453. arXiv:2103.01536. Bibcode:2021AcAau.182..446S. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2021.02.029. ISSN 0094-5765. S2CID 232092198. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ McGee, Ben W. (1 November 2010). «A call for proactive xenoarchaeological guidelines – Scientific, policy and socio-political considerations». Space Policy. 26 (4): 209–213. Bibcode:2010SpPol..26..209M. doi:10.1016/j.spacepol.2010.08.003. ISSN 0265-9646.

- ^ McGee, B. W. (1 December 2007). «Archaeology and Planetary Science: Entering a New Era of Interdisciplinary Research». AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 2007: P41A–0203. Bibcode:2007AGUFM.P41A0203M. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

Bibliography[edit]

- Ankerl, Guy (2000) [2000]. Global communication without universal civilization. INU societal research. Vol. 1: Coexisting contemporary civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. Geneva: INU Press. ISBN 978-2-88155-004-1.

- Brinton, Crane; et al. (1984). A History of Civilization: Prehistory to 1715 (6th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-389866-8.

- Casson, Lionel (1994). Ships and Seafaring in Ancient Times. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-1735-5.

- Chisholm, Jane; Anne Millard (1991). Early Civilization. illus. Ian Jackson. London: Usborne. ISBN 978-1-58086-022-2.

- Collcutt, Martin; Marius Jansen; Isao Kumakura (1988). Cultural Atlas of Japan. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-1927-4.

- Drews, Robert (1993). The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04811-6.

- Edey, Maitland A. (1974). The Sea Traders. New York: Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0-7054-0060-2.

- J. Currie Elles (1908). The influence of commerce on civilization: the Joseph Fisher lecture on commerce delivered at the University of Adelaide by J. Currie Elles esq., April 23rd, 1908 (1st ed.). Adelaide: W. K. Thomas & Co. Wikidata Q106369892.

- Fairservis, Walter A. Jr. (1975). The Threshold of Civilization: An Experiment in Prehistory. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-12775-0.

- Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (2000). Civilizations. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-90171-7.

- Ferrill, Arther (1985). The Origins of War: From the Stone Age to Alexander the Great. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-25093-8.

- Fitzgerald, C.P. (1969). The Horizon History of China. New York: American Heritage. ISBN 978-0-8281-0005-2.

- Fuller, J.F.C. (1954–1957). A Military History of the Western World. 3 vols. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto. ISBN 0-306-80304-6 (1987 reprint).

- From the Defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle of Waterloo. ISBN 0-306-80305-4 (1987 reprint).

- From the American Civil War to the End of World War II. ISBN 0-306-80306-2 (1987 reprint).

- Gowlett, John (1984). Ascent to Civilization. London: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-217090-1.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta (1968). Dawn of the Gods. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-1332-2.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta; David Trump (1993) [1976]. The Atlas of Early Man. London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-312-09746-2.

- Hicks, Jim (1974). The Empire Builders. New York: Time-Life Books.

- Hicks, Jim (1975). The Persians. New York: Time-Life Books.

- Johnson, Paul (1987). A History of the Jews. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-79091-4.

- Jensen, Derrick (2006). Endgame. New York: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 978-1-58322-730-5.

- Keppie, Lawrence (1984). The Making of the Roman Army: From Republic to Empire. Totowa, N.J.: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-0-389-20447-3.

- Korotayev, Andrey, World Religions and Social Evolution of the Old World Oikumene Civilizations: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2004. ISBN 0-7734-6310-0

- Kradin, Nikolay. Archaeological Criteria of Civilization. Social Evolution & History, Vol. 5, No 1 (2006): 89–108. ISSN 1681-4363.

- Lansing, Elizabeth (1971). The Sumerians: Inventors and Builders. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-036357-1.

- Lee, Ki-Baik (1984). A New History of Korea. trans. Edward W. Wagner, with Edward J. Shultz. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-61575-5.

- Nahm, Andrew C. (1983). A Panorama of 5000 Years: Korean History. Elizabeth, N.J.: Hollym International. ISBN 978-0-930878-23-8.

- Oliphant, Margaret (1992). The Atlas of the Ancient World: Charting the Great Civilizations of the Past. London: Ebury. ISBN 978-0-09-177040-2.

- Rogerson, John (1985). Atlas of the Bible. New York: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-1206-0.

- Sandall, Roger (2001). The Culture Cult: Designer Tribalism and Other Essays. Boulder, Colo.: Westview. ISBN 978-0-8133-3863-7.

- Sansom, George (1958). A History of Japan: To 1334. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0523-3.

- Southworth, John Van Duyn (1968). The Ancient Fleets: The Story of Naval Warfare Under Oars, 2600 B.C.–1597 A.D. New York: Twayne.

- Thomas, Hugh (1981). An Unfinished History of the World (rev. ed.). London: Pan. ISBN 978-0-330-26458-7.

- Yap, Yong; Arthur Cotterell (1975). The Early Civilization of China. New York: Putnam. ISBN 978-0-399-11595-0.

- Yurdusev, A. Nuri (2003). International Relations and the Philosophy of History. doi:10.1057/9781403938404. ISBN 978-1-349-40304-2.

External links[edit]

The Pyramid of the Moon in Tenochtitlán, Mexico. Building projects of this size require the social organization found in civilizations.

Civilization refers to a complex human society, in which people live in groups of settled dwellings comprising cities. Early civilizations developed in many parts of the world, primarily where there was adequate water available.

The causes of the growth and decline of civilizations, and their expansion to a potential world society, are complex. However, civilizations require not only external advances to prosper, but also the maintenance and development of good social and ethical relationships usually grounded in religious and spiritual norms.

Definition

The term «civilization» or «civilisation» comes from the Latin word civis, meaning «citizen» or «townsman.» By the most minimal, literal definition, a «civilization» is a complex society.

Anthropologists distinguish civilizations in which many of the people live in cities (and obtain their food from agriculture), from tribal societies, in which people live in small settlements or nomadic groups (and subsist by foraging, hunting, or working small horticultural gardens). When used in this sense, civilization is an exclusive term, applied to some human groups and not others.

«Civilization» can also mean a standard of behavior, similar to etiquette. Here, «civilized» behavior is contrasted with crude or «barbaric» behavior. In this sense, civilization implies sophistication and refinement.

Another use of the term «civilization» combines the meanings of complexity and sophistication, implying that a complex, sophisticated society is naturally superior to less complex, less sophisticated societies. This point of view has been used to justify racism and imperialism—powerful societies have often believed it was their right to «civilize,» or culturally dominate, weaker ones («barbarians»). This act of civilizing weaker peoples has been called the «White Man’s Burden.»

In a broader sense, «civilization» often refers to any distinct society, whether complex and city-dwelling, or simple and tribal. This usage is less exclusive and ethnocentric than the previous definitions, and is almost synonymous with culture. Thus, the term «civilization» can also describe the culture of a complex society, not just the society itself. Every society, civilization or not, has a specific set of ideas and customs, and a certain set of items and arts, that make it unique. Civilizations have more intricate cultures, including literature, professional art, architecture, organized religion, and complex customs associated with the elite.

Samuel P. Huntington, in his essay The Clash of Civilizations, defined civilization as «the highest cultural grouping of people and the broadest level of cultural identity people have short of that which distinguishes humans from other species.» In this sense, a Christian woman of African-American descent, living in the United States of America, would be, above all, considered a member of «Western civilization,» even though she identifies with many cultures.

Finally, «civilization» can refer to human society as a whole, as in the sentence «A nuclear war would wipe out civilization,» or «I’m glad to be safely back in civilization after being lost in the wilderness for three weeks.» It is also used in this sense to refer to a potential global civilization.

Problems with the term «civilization»

As discussed above, «civilization» has a variety of meanings, and its use can lead to confusion and misunderstanding. Moreover, the term carried a number of value-laden connotations. It might bring to mind qualities such as superiority, humaneness, and refinement. Indeed, many members of civilized societies have seen themselves as superior to the «barbarians» outside their civilization.

Many postmodernists, and a considerable proportion of the wider public, argue that the division of societies into «civilized» and «uncivilized» is arbitrary and meaningless. On a fundamental level, they say there is no difference between civilizations and tribal societies, and that each simply does what it can with the resources it has. In this view, the concept of «civilization» has merely been the justification for colonialism, imperialism, genocide, and coercive acculturation.

For these reasons, many scholars today avoid using the term «civilization» as a stand-alone term, preferring to use the terms urban society or intensive agricultural society, which are less ambiguous, and more neutral. «Civilization,» however, remains in common academic use when describing specific societies, such as the Maya Civilization.

Civilization and Culture

As noted above, the term «civilization» has been used almost synonymously with culture. This is because civilization and culture are different aspects of a single entity. Civilization can be viewed as the external manifestation, and culture as the internal character of a society. Thus, civilization is expressed in physical attributes, such as toolmaking, agriculture, buildings, technology, urban planning, social structure, social institutions, and so forth. Culture, on the other hand, refers to the social standards and norms of behavior, the traditions, values, ethics, morality, and religious beliefs and practices that are held in common by members of the society.

What characterizes civilization

Historically, societies referred to as civilizations have shared some or all of the following traits (Winks et al 1995, xii):

- Toolmaking, which permits the development of intensive agricultural techniques, such as the use of human power, crop rotation, and irrigation. This has enabled farmers to produce a surplus of food beyond what is necessary for their own subsistence.

- A significant portion of the population that does not devote most of its time to producing food. This permits a division of labor. Those who do not occupy their time in producing food may obtain it through trade, as in modern capitalism, or may have the food provided to them by the state, as in Ancient_Egypt. This is possible because of the food surplus described above.

- The gathering of these non-food producers into permanent settlements, called cities.

- Some form of ruling system or government. This can be a chiefdom, in which the chieftain of one noble family or clan rules the people; or a state society in which the ruling class is supported by a government or bureaucracy.

- A social hierarchy consisting of different social classes.

- A form of writing will have developed, so that communication between groups and generations is possible.

- The establishment of complex, formal social institutions such as organized religion and education, as opposed to the less formal traditions of other societies.

- Development of complex forms of economic exchange. This includes the expansion of trade and may lead to the creation of money and markets.

- A concept of a Higher being, though not necessarily through organized religion, by which a people may develop a common worldview that explains events and finds purpose.

- A concept of time, by which the society links itself to the past and looks forward to the future.

- A concept of leisure, permitting advanced development of the arts.

- Development of a faculty for criticism. This need not be the rationalism of the West, or any specific religious or political mechanism, but its existence is necessary for enabling the society to contemplate change from within rather than suffering attack and destruction from outside.

Based on these criteria, some societies, like that of Ancient Greece, are clearly civilizations, whereas others, like the Bushmen, are not. However, the distinction is not always so clear. In the Pacific Northwest of the United States, for example, an abundant supply of fish guaranteed that the people had a surplus of food without any agriculture. The people established permanent settlements, a social hierarchy, material wealth, and advanced art (most famously totem poles), all without the development of intensive agriculture. Meanwhile, the Pueblo culture of southwestern North America developed advanced agriculture, irrigation, and permanent, communal settlements such as Taos Pueblo. However, the Pueblo never developed any of the complex institutions associated with civilizations. Today, many tribal societies live in states and according to their laws. The political structures of civilization were superimposed on their way of life, and so they occupy a middle ground between tribal and civilized.

Early civilizations

Early human settlements were built mostly in river valleys where the land was fertile and suitable for agriculture. Easy access to a river or a sea was important, not only for food (fishing) or irrigation, but also for transportation and trade. Some of the earliest known civilizations arose in the Nile valley of Ancient Egypt, on the island of Crete in the Aegean Sea, around the Euphrates and Tigris rivers of Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley region of modern Pakistan, and in the Huang He valley (Yellow River) of China. The inhabitants of these areas built cities, created writing systems, learned to make pottery and use metals, domesticated animals, and created complex social structures with class systems.

Ancient Egypt

Both anthropological and archaeological evidence indicate the existence of a grain-grinding and farming culture along the Nile in the tenth millennium B.C.E. Evidence also indicates human habitation in the southwestern corner of Egypt, near the Sudan border, before 8000 B.C.E. Climate changes and/or overgrazing around 8000 B.C.E. began to desiccate the pastoral lands of Ancient Egypt, eventually forming the Sahara (around 2500 B.C.E.). Early tribes naturally migrated to the Nile River where they developed a settled agricultural economy, and a more centralized society. Domesticated animals had already been imported from Asia between 7500 B.C.E. and 4000 B.C.E. There is evidence of pastoralism and cultivation of cereals in the East Sahara in the seventh millennium B.C.E. The earliest known artwork of ships in Ancient Egypt dates to 6000 B.C.E.

The Ancient Pyramids of Egypt that still rise above the desert were designed with the intention that spirits of deceased rulers could more easily return to their bodies.

By 6000 B.C.E. Pre-dynastic Egypt (in the southwestern corner of Egypt) was herding cattle and constructing large buildings. Symbols on Gerzean pottery (around 4000 B.C.E.) resemble traditional Egyptian hieroglyph writing. In Ancient Egypt mortar (masonry) was in use by 4000 B.C.E., and ancient Egyptians were producing ceramic faience as early as 3500 B.C.E. There is evidence that ancient Egyptian explorers may have originally cleared and protected some branches of the ‘Silk Road.’ Medical institutions are known to have been established in Egypt since as early as around 3000 B.C.E. Ancient Egypt also gains credit for the tallest ancient pyramids, and the use of barges for transportation.

Egyptian religion permeated every aspect of life. It dominated life to such an extent that almost all the monuments and buildings that have survived are religious rather secular. The dominant concern of Egyptian religion was maintenance of the rhythm of life, symbolized by the Nile, and with preventing order from degenerating into chaos. Egyptians believed profoundly in an after-life, and much effort and wealth was invested in building funerary monuments and tombs for the rulers. The priests served the Gods but also performed social functions, including teaching, conducting religious rites and offering advice.

Arnold J. Toynbee claimed that of the 26 civilizations he identified, Egypt was unique in having no precursor or successor, although since Egypt bequeathed many ideas and concepts to the world it could be argued that human kind as a whole is the successor. Ancient Egyptian contributions to knowledge in the areas of mathematics, medicine, and astronomy continue to inform modern thought. While Egyptian religion no longer exists in its original form, both Judaism and Christianity acknowledge a certain indebtedness to Egypt.

Aegean civilizations

Aegean civilization is the general term for the prehistoric civilizations in Greece and the Aegean. The earliest inhabitants of Knossos, the center of Minoan Civilization on Crete, date back to the seventh millennium B.C.E. The Minoans flourished from approximately 2600 to 1450 B.C.E., when their culture was superseded by the Mycenaean culture, which drew upon the Minoans.

Based on depictions in Minoan art, Minoan culture is often characterized as a matrilineal society centered on goddess worship. Although there are also some indications of male gods, depictions of Minoan goddesses vastly outnumber depictions of anything that could be considered a Minoan god. There seem to be several goddesses including a Mother Goddess of fertility, a «Mistress of the Animals,» a protectress of cities, the household, the harvest, and the underworld, and more. They are often represented by serpents, birds, and a shape of an animal on the head. Though the notorious bull-headed Minotaur is a purely Greek depiction, seals and seal-impressions reveal bird-headed or masked deities. Minoan sacred symbols include the bull and its horns of consecration, the «labrys» (double-headed axe), the pillar, the serpent, the sun, and the tree.

The Aegean civilization developed three distinctive features:

- An indigenous writing system, which consisted of characters of which only a very small percentage were identical, or even obviously connected, with those of any other script.

- Aegean Art is distinguishable from those of other early periods and areas. While borrowing from other contemporary arts Aegean craftsman gave their works a new character, namely realism. The fresco-paintings, ceramic motifs, reliefs, free sculpture, and toreutic handiwork of Crete provide the clearest examples.

- Aegean Architecture: Aegean palaces are of two main types.

- First (and perhaps earliest in time), the chambers are grouped around a central court, being linked to one another in a labyrinthine complexity, and the greater oblongs are entered from a long side and are divided longitudinally by pillars.

- Second, the main chamber is of what is known as the megaron type, i.e. it stands free, isolated from the rest of the plan by corridors, is entered from a vestibule on a short side, and has a central hearth, surrounded by pillars and perhaps open to the sky. There is no central court, and other apartments form distinct blocks. In spite of many comparisons made with Egyptian, Babylonian and Hittite plans, both of these arrangements remain out of keeping with any remains of earlier or contemporary structures elsewhere.

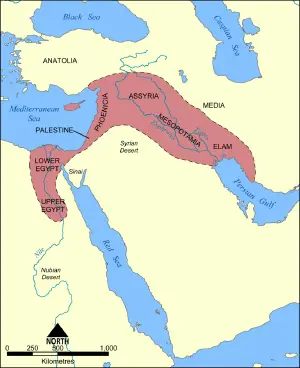

Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent is a historical region in the Middle East incorporating Ancient Egypt, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. Watered by the Nile, Jordan, Euphrates, and Tigris rivers and covering some 400-500,000 square kilometers, the region extends from the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea, around the north of the Syrian Desert, and through the Jazirah and Mesopotamia, to the Persian Gulf.

This map shows the extent of the Fertile Crescent.

The Fertile Crescent has an impressive record of past human activity. As well as possessing many sites which contain the skeletal and cultural remains of both pre-modern and early modern humans (e.g. at Kebara Cave in Israel), later Pleistocene hunter-gatherers and Epipalaeolithic semi-sedentary hunter-gatherers (the Natufians), this area is most famous for its sites related to the origins of agriculture. The western zone around the Jordan and upper Euphrates rivers gave rise to the first known Neolithic farming settlements, which date to around 9,000 B.C.E. (and includes sites such as Jericho). This region, alongside Mesopotamia, which lies to the east of the Fertile Crescent, between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, also saw the emergence of early complex societies during the succeeding Bronze Age. There is also early evidence from this region for writing, and the formation of state-level societies. This has earned the region the nickname «The Cradle of Civilization.»

As crucial as rivers were to the rise of civilization in the Fertile Crescent, they were not the only factor in the area’s precocity. The Fertile Crescent had a climate which encouraged the evolution of many annual plants, which produce more edible seeds than perennials, and the region’s dramatic variety of elevation gave rise to many species of edible plants for early experiments in cultivation. Most importantly, the Fertile Crescent possessed the wild progenitors of the eight Neolithic founder crops important in early agriculture (i.e. wild progenitors to emmer, einkorn, barley, flax, chick pea, pea, lentil, bitter vetch), and four of the five most important species of domesticated animals— cows, goats, sheep, and pigs—and the fifth species, the horse, lived nearby.

The religious writings of the Sumerian people, generally regarded as the first people living in Mesopotamia, are the oldest examples of recorded religion in existence. They practiced a polytheistic religion, with anthropomorphic gods or goddesses representing forces or presences in the world, much as in later Greek mythology. Many stories in the Sumerian religion appear homologous to those in other religions. For example, the Judeo-Christian account of the creation of man and Noah’s flood narrative closely resemble earlier Sumerian descriptions.

Indus Valley civilization