Since

the word is such a fundamental unit in both language and thought, let

us not try an exhaustive definition and concentrate instead on those

properties of words which are of greatest importance for linguistics:

-

A

word is a unity of meaning and form. -

A

word is composed of one or more morphemes which are the smallest

meaningful units. -

The

meaning of a word is a whole and not a sum of meanings of its

component morphemes. -

The

morphemes, and therefore the word, are made up of one or more spoken

sounds (or their graphic representations). -

A

word is made graphically and phonetically separate from other words

by spacing, intonation, and stress. Thus,

a number of formal

criteria

can be suggested. In writing, for instance, a word is something

which has a space on either side. But in speech, there is no exact

equivalent of this; we do not pause after every word when we speak.

Then one such criterion in writing is leaving a space and in oral

speech it is a potential pause which often coincides with the spaces

in writing. -

A

word, unlike a morpheme, is a minimum syntactically complete

structure (= a minimum complete utterance). Another

criterion is that words are the smallest units in a language that

can

be used alone as a sentence.

We can say Go.

Here.

Men.

We cannot use the bits of words as sentences, as with un

-,-ize, in-. -

There

are two classes of morphemes – those used to produce new words and

those used for linking words together in a syntactic unity. -

The

freedom of linking words together is limited by syntactic rules

which form a separate field of study. Yet

another criterion for word identification is in terms of minimal

unit of positional mobility

– which is simply a precise way of saying that the word is the

smallest unit which can be moved from one position to another in a

sentence – bits of words cannot be so moved. -

Words

are relatively stable in use, and therefore can be isolated and

fixed in dictionaries. Words

are the units which have fixed

internal structure.

Technically this characteristic is often referred to as internal

stability. If we want to insert fresh information into a sentence,

then it is between the words that this information goes and not

within them. Words are not interruptable.

Another

technique may be helpful in identifying separate words in a language,

namely the use of formulas of speech. One may say This

is a

… followed by various free forms such as pen,

book, house,

etc.

So

the word differs from the morpheme, on the one hand, and the

word-combination, on the other, and can be singled out in the flow of

speech as an independent unit.

We

can distinguish the following criteria of the word:

– the

phonetic criterion (pause, accent, intonation),

– the

acoustic identity of the word,

– the

criteria of separability, replaceability and displaceability,

– the

semantic criterion,

– the

criterion of isolatedness and reproducibility.

One

more problem that is connected with the problem of the definition of

the word is the existence of homonymous forms. In this case it is

difficult to say whether it is one word or different words. As an

example let’s take a sentence «Of

all the saws I ever saw I never saw a saw as that saw saws».

Here

we deal with two different words: the noun saw

and the verb saw,

because they have two different paradigms. Paradigm is the system of

the grammatical forms of a word. It means that though they are

identical in sound and spelling, they are different in meaning,

distribution (usage) and origin.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Word: The Definition & Criteria

In traditional grammar, word is the basic unit of language. Words can be classified according to their action and meaning, but it is challenging to define.

A word refers to a speech sound, or a mixture of two or more speech sounds in both written and verbal form of language. A word works as a symbol to represent/refer to something/someone in language to communicate a specific meaning.

Example : ‘love’, ‘cricket’, ‘sky’ etc.

«[A word is the] smallest unit of grammar that can stand alone as a complete utterance, separated by spaces in written language and potentially by pauses in speech.» (David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press, 2003)

Morphology, a branch of linguistics, studies the formation of words. The branch of linguistics that studies the meaning of words is called lexical semantics.

See More:

Online English Grammar Course

Free Online Exercise of English Grammar

There are several criteria for a speech sound, or a combination of some speech sounds to be called a word.

- There must be a potential pause in speech and a space in written form between two words.

For instance, suppose ‘ball’ and ‘bat’ are two different words. So, if we use them in a sentence, we must have a potential pause after pronouncing each of them. It cannot be like “Idonotplaywithbatball.” If we take pause, these sounds can be regarded as seven distinct words which are ‘I,’ ‘do,’ ‘not,’ ‘play,’ ‘with,’ ‘bat,’ and ‘ball.’ - Every word must contain at least one root. If you break this root, it cannot be a word anymore.

For example, the word ‘unfaithful’ has a root ‘faith.’ If we break ‘faith’ into ‘fa’ and ‘ith,’ these sounds will not be regarded as words. - Every word must have a meaning.

For example, the sound ‘lakkanah’ has no meaning in the English language. So, it cannot be an English word.

Four types of criteria are employed to set up word classes – syntactic, morphological, morpho-syntactic and semantic. (Semantic criteria have to do with meaning.) We begin with a brief explanation of morphological and morpho-syntactic criteria, which have to do with what is called inflectional morphology. Consider the English examples The tiger is smiling and The tigers are smiling. The contrast between tiger and tigers shows that tigers can be split into tiger and -s. Tiger is the stem and -s is the suffix added to the end of the stem. The stem tiger is a noun and the addition of -s does not affect this property. In contrast, the addition of -ish does affect it; tiger is a noun but tigerish is an adjective. In dictionaries of English, tigerish and tigers are treated differently. Tigerish is listed as a separate lexical item, that is, it might be listed in the same entry as tiger but appear in bold and with a short explanation of its meaning; tigers has no entry at all, since the makers of dictionaries assume that

users will know how to convert the singular form of a given noun to a plural form.

Suffixes such as -ish that derive new lexical items are derivational suffixes; suffixes that express grammatical information, such as ‘plural’, are inflectional suffixes. (The term comes from the Latin verb flectere ‘to bend’ and is connected with the idea that, in languages such as Russian

with a multitude of inflectional suffixes, nouns, verbs and adjectives have a basic form that is bent by the addition of a suffix.) There is one more property of inflectional suffixes: in the tiger clauses above, tiger combines with is smiling and tigers combines with are smiling. That is, there is linkage

between subject noun and verb. Traditionally, a distinction is drawn between agreement and government; these topics will be discussed in Chapter 9.

Morphological Criterion

The singular form criterion is used in the heading because what is at stake is simply whether a given word allows grammatical suffixes or not. This criterion is the least important of the four listed above and is more relevant to some languages than others. It is of the greatest interest with respect to languages such as Russian, in which nouns have different suffixes (‘endings’ in the traditional, informal terminology) depending on their relationship to the verb. Examples are given in (1).

(1) a. Sobaka lajala

dog barked

‘The dog barked.’

b. Koshka tsarapala sobaku

cat scratched dog

‘The cat scratched the dog.’

c. Petr dal sobake kost’

Peter gave dog bone

‘Peter gave the dog a bone.’

The noun sobaka in (1a) splits into the stem sobak- and the suffix -a, which here signals the animal doing the barking. In (1b), sobak- has its direct object suffix -u, which here marks the animal being scratched; in (1c), it has its oblique object suffix -e, which here marks the recipient of the bone. A few nouns in Russian take no suffixes, for example taksi (taxi), kofe (coffee) and kakadu (cockatoo). (Such nouns do not vary their shape and are called invariable words.) English does not have the same range of grammatical suffixes as Russian, but English nouns typically take a plural ending – fish –fishes, cat –cats and dog–dogs. (The -s represents different suffixes in speech – in cats it represents the initial sound of speed, in dogs the initial sound of zap.) Some nouns in English do not take a plural suffix – for example sheep, deer – and are said to be invariable.

Morpho-syntactic Criteria

These criteria have to do with inflectional suffixes, as described above in connection with the tiger examples, and the information signalled by them, and were developed on the basis of languages such as Classical Latin and Classical Greek. We looked at Russian examples above because Russian is not only very like Latin and Greek in its richness of inflectional suffixes but is also a living language. It will be helpful to take a further look at Russian before returning to English.

Examples (1a–c) show that nouns in Russian take different suffixes which signal the relationship between the nouns and the verb in a clause. (See Chapters 10 and 11 for a discussion of these relationships.) These relationships are known as case, and nouns are said to be inflected for the category of case. (‘Case’ derives from the Latin word for a fall, casus. The basic form of a noun, such as sobaka in (1a) – the subject form; see Chapter 8 – was thought of as upright, and the other forms were thought of as falling away from the subject form.) Other information is signalled by case suffixes in Indo-European languages. Consider (2).

(2) a. Sobaki lajut

dogs bark

‘The dogs are barking.’

(2) b. Petr dal kost’ sobakam

Peter gave bone to-dogs

‘Peter gave a bone to the dogs.’

In (2a), sobaki is the subject but also plural, and it has a different suffix, -i. In (2b), sobakam refers to the recipient and is plural and it too has a different suffix from the one in (1c), -am. That is, the case suffixes actually signal information about case and about number.

Verbs in Russian signal information about time, person and number, as illustrated in (3).

Examples (3a–d) all refer to an event of speaking about Moscow: (3a) and (3b) place that event in present time; the speaker, as it were, says ‘I am speaking to you now and they are speaking about Moscow’. Example (3d) presents the event in past time; the speaker can be imagined as saying ‘I am speaking to you now and at some before this they were speaking about Moscow’. Information about the time of an event is signalled by the difference in form between govorit and govorjat on the one hand and govorili on the other, the l in govorili indicating past time. Such differences in verbs are said to express tense.

Example (3a) contains govorit, and (3b) contains govorjat. Both are said to be in the third person; in the traditional scheme, first person is the speaker, at the centre of any piece of interaction by means of language; close to the centre is second person, the person(s) addressed by the speaker. Other participants, or other people or things talked about by the speaker, are third persons. The contrasts in form are said to express person. (The term ‘person’ is not entirely appropriate for animals or inanimate objects, but human beings tend to place human beings at the centre of their thinking about the world; typical conversation is taken to be by human beings about human beings.)

Returning to (3a) and (3b), (3a) presents the speaking as being done by one person, (3b) presents it as being done by more than one person. These contrasts are said to express number (as does a different set of contrasts in the shape of nouns, as illustrated in (1) and (2).

In the languages regarded as native to Europe (belonging mostly to the Indo-European and Finno-Ugric families), the words classed as nouns carry information about number and, in some languages, about case; words classed as verbs carry information about tense, person and number (and some other types of information not mentioned here – for a more detailed discussion, see Chapter 13). In traditional terms, nouns are inflected for case and number, and verbs are inflected for tense, person and number. In some languages, adjectives too are inflected for case and number. Adverbs and prepositions are typically not inflected, though some prepositions in the Celtic languages (Scottish and Irish Gaelic, Welsh and Breton (also Cornish in Cornwall and Manx in the Isle of Man) do have inflected forms as a result of historical change. It is as though in English the sequences to me and to you had coalesced into what were perceived as single words, tme and tyou (the latter probably pronounced chew).

English does not have the rich system of inflections possessed by languages such as Russian, but English nouns do take suffixes expressing number (cat and cats, child and children and so on), and English verbs do take suffixes expressing tense: pull and pulls vs pulled. There are of course nouns, such as mouse –mice, that express number by other means, and there are verbs, such as write –wrote, eat –ate, that express tense by other means. Person is expressed only by the -s suffix added to verbs in the present tense – pulls, writes and so on. Of course, English verbs cannot occur on their own in declarative clauses but require at least one noun phrase, which could consist of just a personal pronoun – I, you, he, she, it, we, they. To the extent that English verbs require a noun phrase, which is often a personal pronoun (in 65 per cent of clauses in spontaneous spoken English), we are entitled to regard person as a category intrinsic to the verb in English. (Non-personal pronouns, that is nouns, are by definition third person.)

English adjectives are not associated with number or case, but many of them take suffixes signalling a greater quantity of some property (for example bigger) or the greatest quantity of some property (for example biggest). These morpho-syntactic properties of English words, signalling

information about tense, person and number, are presented in this chapter as relevant to the recognition of different word classes, but as we will see in Chapter 8 they are also relevant to linkage (agreement and government), as mentioned at the beginning of this chapter.

Syntactic Criteria

The syntactic criteria for word classes are based on what words a given word occurs with and the types of phrase in which a given word occurs. Syntactic criteria are the most important. They are important for English with its relative poverty of morpho-syntactic criteria, and they are crucial for the analysis of word classes in general because there are languages such as Mandarin Chinese which have practically no inflectional suffixes (such as plural endings); in contrast, all languages have syntax.

The recognition of syntactic criteria as central is a major step forward, but the application of these criteria is not straightforward. Consider the English words that are called nouns. They all have several properties in common, namely they can occur in various positions relative to the verb in a clause. Examples (4a–c) are instances of the [NON-COPULA, ACTIVE, DECLARATIVE] construction described in Chapter 3.

(4) a. The dog stole the turkey.

b. The children chased the dog.

c. The cook saved no scraps for the dog.

Dog occurs to the left of stole in (4a), to the right of chased in (4b), and to the right of saved in (4c) but separated from it by the intervening word for. Dog also occurs in a noun phrase and can be modified by a word such as the – The dog stole the turkey – or by an adjective – Hungry dogs stole the turkey – or by the and an adjective together – The hungry dogs stole the turkey.

All other nouns in English can occur to the left of the verb in an active declarative clause, but not all nouns combine with an article, or combine with articles in the same way as dog does. (This property of nouns has already been mentioned in Chapter 1 in connection with dependency relations and the idea that different nouns require or allow different types of word inside a noun phrase.) Dog stole the turkey is unacceptable (assuming Dog is not a proper name), whereas Ethel stole the turkey is not. The difficulty is that the class of English nouns is a very large class of words that do not all keep the same company (or, to use another metaphor, do not all behave in the same way). All nouns meet the criteria of occurring to the left of a verb in an active declarative clause, of occurring immediately to the right of a verb in an active declarative clause or of occurring to the right of a verb but preceded by a preposition. These are major criteria, but there are the minor criteria mentioned above, such as combining with an article, or being able to occur without an article, or not allowing a plural suffix (*Ethels). These split the class of nouns into subclasses.

A sufficiently detailed examination of the company kept by individual nouns would probably reveal that each noun has its own pattern of occurrence. Thanks to very large electronic bodies of data and the search power of computers, analysts are beginning to carry out such examinations and to find such individual patterns. For the purposes of analyzing syntax, however, it is not helpful to gather information about

individual nouns and it is impossible to produce a usable analysis of English syntax (or the syntax of any other language) with, say, 20,000 word classes. To analyse and discuss the general syntactic structure of clauses and sentences, we need fairly general classes, and analysts try to keep to major criteria plus those minor criteria that lead to relatively large classes of words. For other purposes, such as compiling a dictionary, smaller classes are required, down to information about individual words.

A concept that is central to discussion of word classes, and indeed to any class of items, linguistic or non-linguistic, is that of the central and peripheral members of a class. Consider the adjective tall in the examples in (5).

(5) a. a tall building

b. This building is tall.

c. a very tall building

d1. a taller building

d2. a more beautiful building

There are two criteria labelled ‘d’ because some adjectives take the comparative suffix -er while others do not allow that suffix but require more. Some adjectives, like tall, meet all the criteria in (5) and are central or prototypical members of the class. Some adjectives fail to meet all the criteria. Unique satisfies (5a–c), as in a unique building, This building is unique and a very unique building. (Publishers’ copy-editors might object to very unique, but the combination occurs regularly in speech and in informal writing and even in newspapers.) Unique does not combine with -er or more : *a uniquer building, *a more unique building. In the class of adjectives, unique is slightly less central than tall. Woollen meets even fewer criteria. A woollen cloak and This cloak is woollen are acceptable, but *a woollener cloak, *a more woollen cloak and *a very woollen cloak are not. Woollen is less central than unique, which in turn is less central than tall. Right at the edge of the class is asleep, which meets only one of the criteria in (5), namely (5b). The child is asleep is acceptable but not *the asleep child, *the very asleep child, *the more asleep child. On the other hand, asleep meets none of the criteria for nouns, verbs, prepositions or adverbs; it is a peripheral adjective.

Semantic Criteria : What Words Mean

There are no semantic criteria, aspects of the meaning of the different classes of words, that would enable us to decide whether any given word is a noun, adjective, verb, adverb or preposition. We must accept right here that meaning cannot be exploited in this way. The traditional definition of nouns as words denoting people, places or things does not explain why words such as anger, idea or death are classified as nouns. Race the noun and race the verb both denote an event, as do the verb transmit in They transmitted the concert live and the noun transmission in The live transmission of the concert.

On the other hand, this book is based on the view that grammar is interesting because it plays an essential role in the communication of coherent messages of all sorts. It has been demonstrated many times that humans cannot (easily) remember meaningless symbols such as random sequences of words or numbers, like telephone numbers and PIN numbers. Psycholinguists know that children cannot learn sequences of symbols without meaning. It would be surprising were there no parallels at all between patterns of grammar and semantic patterns; we abandon the traditional notion that classes of words can be established on the basis of what words denote, but careful analysis does bring out patterns. The analysis uses the ideal of central, prototypical members of word classes as opposed to peripheral members, and it focuses on what speakers and writers do with words rather than on the traditional dictionary meanings.

The key move in the investigation of word classes is to accept that word classes must be defined on the basis of formal criteria – their morphological properties, their morpho-syntactic properties and their syntactic properties. Only when these formal patterns have been established can we move on to investigate the connection between meaning and word classes.

How do formal criteria and the concept of central members of a word class help the investigation of meaning? Interestingly, the traditional description of nouns as referring to persons, places and things turns out to be adequate for central nouns. Nouns such as girl, town and car combine with the and a, take the plural suffix -s, are modified by adjectives and occur to the left or the right of the verb in [NON-COPULA, ACTIVE DECLARATIVE] clauses. They also refer to observable entities such as people, places and things. What is significant is the combination of syntactic and morpho-syntactic properties with the semantic property of referring to people, places or things.

Many analysts argue that nouns such as anger, property and event do not denote things. However, these nouns do possess all or many of the syntactic and morpho-syntactic properties possessed by girl, town and car : a property, the properties, an interesting property, invent properties, This property surprised us and so on. Anger meets some of the major criteria – The anger frightened him [subject, and combination with the] but not *an anger. The fact that the major formal criteria for prototypical nouns apply to words such as property and anger is what justifies the latter being classed as nouns. On the assumption that these formal properties are not accidental, it also suggests that ‘ordinary speakers’ of English treat anger as though it denoted an entity.

A discussion of the linguistic and cognitive issues would be inappropriate here. What cannot be emphasised enough is that a word’s classification as noun, verb and so on is on the basis of formal criteria; the terms ‘noun’, ‘verb’ and so on are merely labels for classes which could be replaced by neutral labels such as ‘Class 1’, ‘Class 2’ and so on. Words apparently very diverse in meaning such as anger and dog share many major syntactic and morpho-syntactic properties, and this raises deep and interesting questions about how ‘ordinary speakers’ conceive the world. It leads to the unexpected conclusion that the traditional semantic definitions of word classes, while quite unsatisfactory as definitions, nonetheless reflect an important fact about language and how ordinary speakers understand the world around them.

The need for both formal and semantic criteria becomes quite clear in comparisons of two or more languages. Descriptions of Russian, say, contain statements about the formal properties of nouns and verbs in Russian; descriptions of English contain statements about nouns and verbs in English. But formal criteria do not allow the English words labelled ‘noun’ to be equated to the Russian words labelled ‘noun’; the formal criteria for the English word class are completely different from the formal criteria for the Russian word class. In spite of this, analysts and learners of Russian as a second language find no difficulty in talking of nouns in English and nouns in Russian and in equating the two. The basis for this behavior must be partly semantic; central nouns in Russian (according to the Russian formal criteria) denote persons, places and things, and so do central nouns in English.

Semantic Criteria : What Speaker do with Words

Even more important is what speakers and writers do with language. When they produce utterances, they perform actions. They act to produce sounds or marks on paper, but the purpose of producing the sounds (in many situations) is to draw the attention of their audience to some entity and to say something about it, to predicate a property of it. Examples of acts – let us use the generally accepted term ‘speech acts’ – are making statements, asking questions and issuing commands (in the broadest sense). These speech acts are prominent in and central to human communication and are allotted grammatical resources in every language – see Chapter 3 on constructions. Other acts are not so prominent

but are no less central to human communication and relate directly to the different parts of speech.

Two such speech acts are referring to entities and predicating properties of them. In English, the class of nouns, established on formal criteria, contains words denoting entities, and nouns enter into noun phrases, the units that speakers use when referring to entities. This is not to say that every occurrence of a noun phrase is used by a speaker to refer to something; nor is the difference between nouns and other word classes connected solely with referring; nonetheless, speakers require noun phrases in order to refer, and noun phrases can be used to refer only because they contain nouns.

The notion of predication as a speech act is prevalent in traditional grammar and is expressed in the formula of ‘someone saying something about a person or thing’. Predication has been largely ignored in discussions of speech acts, perhaps because it is always part of a larger act, making a statement or asking a question or issuing a command. In English, verbs, including BE, signal the performance of a predication.

Whether adjectives and adverbs are associated with a speech act is a question that has not received much discussion. It is interesting, however, that in traditional grammar adjectives are also labelled ‘modifiers’, a label which reflects the function of these words in clauses. Speakers and writers use verbs to make an assertion about something, and the assertion involves assigning a property to that something. They use adjectives not to make an assertion but merely to add to whatever information is carried by the head noun in a given noun phrase.

Explaining the different word classes or parts of speech in terms of speech acts offers a solution to one difficulty with the traditional definitions; the class of things is so wide that it can be treated as including events; even properties, which are said to be referred to by adjectives, can be thought of as things. In contrast, different speech acts correspond to different word classes. The speech-act explanation also provides a connection between word classes in different languages. Assuming that basic communicative acts such as referring and predicating are recognized by speakers of different languages (communication between speakers of different languages would otherwise be impossible), the words classed as nouns in descriptions of, say, Russian, and the words classed as nouns in descriptions of, say, English, have in common that speakers pick words from those classes when referring. Similarly, speakers and writers pick what are called verbs when predicating, adjectives when adding to the information carried by a noun (that is, when they perform the speech act of modifying) and adverbs when they add to the information carried by a verb or an adjective.

WORD FORMATION • Compounding/composition – Criteria of compounds. – Classification of compounds. • Secondary ways of word formation.

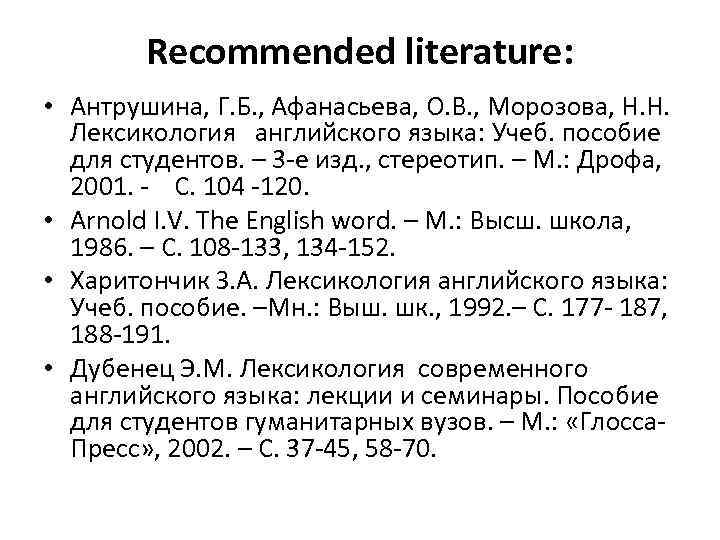

Recommended literature: • Антрушина, Г. Б. , Афанасьева, О. В. , Морозова, Н. Н. Лексикология английского языка: Учеб. пособие для студентов. – 3 -е изд. , стереотип. – M. : Дрофа, 2001. — С. 104 -120. • Arnold I. V. The English word. – M. : Высш. школа, 1986. – С. 108 -133, 134 -152. • Харитончик З. А. Лексикология английского языка: Учеб. пособие. –Мн. : Выш. шк. , 1992. – С. 177 — 187, 188 -191. • Дубенец Э. М. Лексикология современного английского языка: лекции и семинары. Пособие для студентов гуманитарных вузов. – М. : «Глосса. Пресс» , 2002. – С. 37 -45, 58 -70.

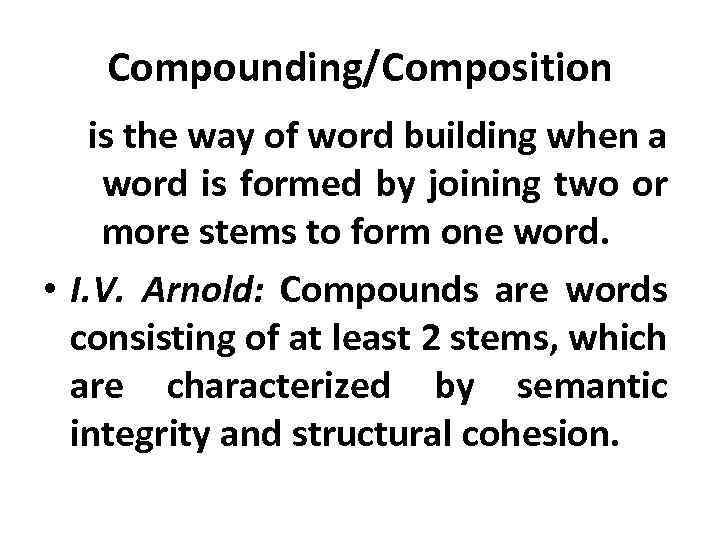

Compounding/Composition is the way of word building when a word is formed by joining two or more stems to form one word. • I. V. Arnold: Compounds are words consisting of at least 2 stems, which are characterized by semantic integrity and structural cohesion.

• R. S. Ginsburg distinguishes between 2 levels of analysis: derivational and morphemic. • E. g. to nickname, to baby-sit, to honeymoon • On the morphemic level these are compound words, • On the derivational level these are words created by either conversion (to nickname, to honeymoon) or by back formation (to babysit) => they are derivatives.

Compound words are characterized • by semantic integrity and structural cohesion. • Structurally compounds are characterized by the specific order of arrangement in which stems follow one another.

The lexical meaning of a compound • may be a sum of meanings of its constituents, i. e. they may be motivated, e. g. tablecloth, shoemaker, bookshelf; • the lexical meanings of the constituents may be fused together to create a new additive meaning, i. e. partially motivated, e. g. handbag – a bag to be carried in the hand -> additive meaning: a women’s bag to keep money and other stuff; flowerbed), • the meaning of a compound has nothing to do with the meanings of its constituents, i. e. nonmotivated or idiomatic, e. g. a sweet tooth, a chatter box.

Main features of compounds • The unity of stress; • Solid or hyphenated spelling; • Semantic unity; • Unity of morphological and syntactic functioning.

Criteria of compounds • Eugene Nider: Criteria for determining the word units in a language are of 3 types: phonological, morphological, and syntactic. • Charles Bally suggested the graphic criterion, • Otto Jesperson – the semantic criterion.

The phonological criterion • compound words are, as a rule, characterised by 1 main primary stress (and a secondary stress) in compound, while in free word combinations both components are stressed: • /blackboard — /black /board; • /laughing gas — /laughing /boys.

The morphological criterion • the structural integrity of compounds enables compounds to function as an inseparable unit and has 1 paradigm.

The syntactic criterion • The components of compounds can t have modifiers. E. g. compare: sky – blue (adj. ), but: blue sky -> very blue sky. • The semantic criterion • A combination of words refers to the number of concepts/notions = the number of words, a compound refers to 1 concept : Its colour; kind of colour.

The graphic criterion • everything written in one word or hyphenated is considered a compound and the words written separately are elements of a combination e. g. a tall boy – a tallboy

Classifications of compounds • Compounds may be classified in accordance with different principles: • -part of speech reference: Noun honeymoon, Verb to babysit, Adjective power-happy; • -the way components are joined: • neutral compounds (without a linking element) to window-shop; • morphological compounds (with a linking element) handicraft; • syntactical compounds free-for-all, do-or-die, here-and-now;

— the syntactic relations between the stems (coordination or subordination) • compounds fall into coordinative and subordinative. • In coordinative compounds the constituents are semantically and structurally equal. The coordinative compounds may be subdivided into • 1. additive actor – manager, secretary –stenographer • 2. reduplicative tic-tic, hash-hash • 3. words with varied rhythmic form of the same stem: willy- nilly, tic-toc, drip – drop.

• In subordinative compounds the components are neither semantically nor structurally equal. • Their relation is based on the domination of 1 component over the other. The 2 nd component is usually a structural and semantic center of a compound, e. g. ship – wreck, inn – keeper, tooth – brush

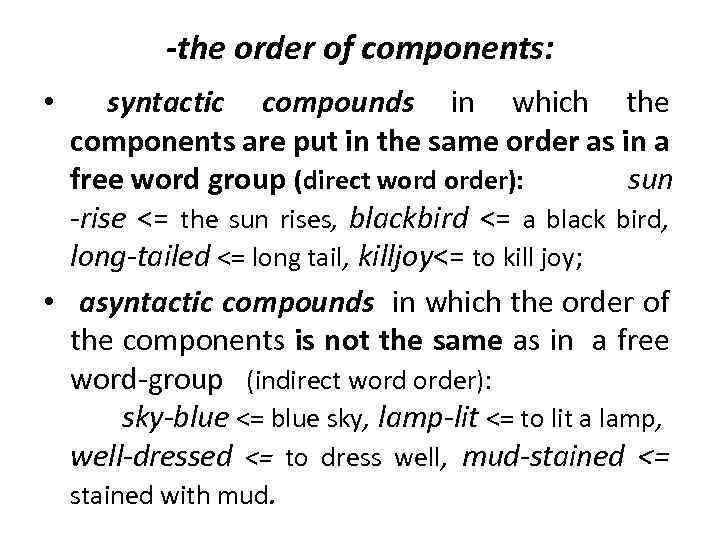

-the order of components: syntactic compounds in which the components are put in the same order as in a free word group (direct word order): sun -rise <= the sun rises, blackbird <= a black bird, long-tailed <= long tail, killjoy<= to kill joy; • asyntactic compounds in which the order of the components is not the same as in a free word-group (indirect word order): sky-blue <= blue sky, lamp-lit <= to lit a lamp, well-dressed <= to dress well, mud-stained <= stained with mud. •

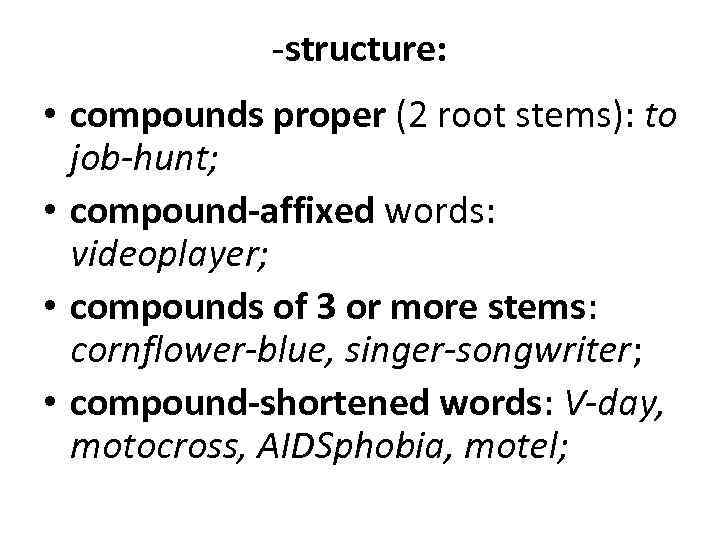

-structure: • compounds proper (2 root stems): to job-hunt; • compound-affixed words: videoplayer; • compounds of 3 or more stems: cornflower-blue, singer-songwriter; • compound-shortened words: V-day, motocross, AIDSphobia, motel;

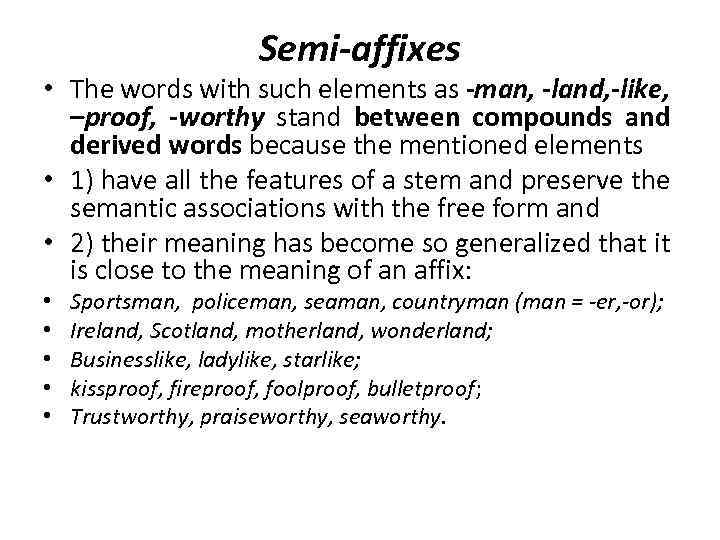

Semi-affixes • The words with such elements as -man, -land, -like, –proof, -worthy stand between compounds and derived words because the mentioned elements • 1) have all the features of a stem and preserve the semantic associations with the free form and • 2) their meaning has become so generalized that it is close to the meaning of an affix: • • • Sportsman, policeman, seaman, countryman (man = -er, -or); Ireland, Scotland, motherland, wonderland; Businesslike, ladylike, starlike; kissproof, fireproof, foolproof, bulletproof; Trustworthy, praiseworthy, seaworthy.

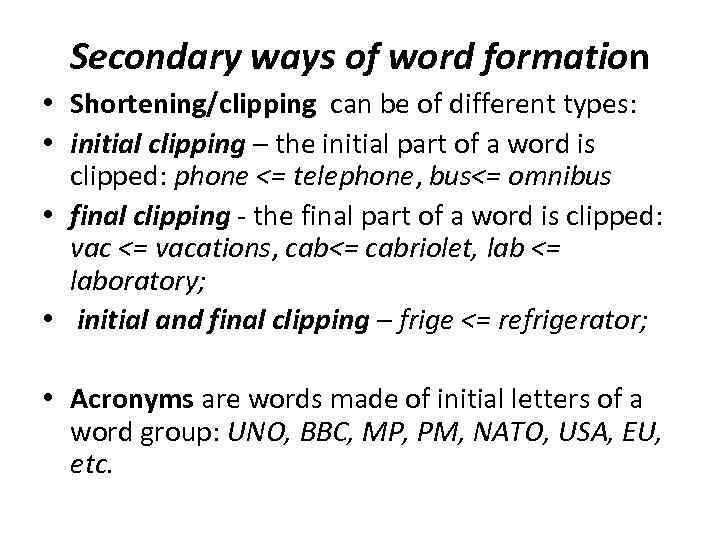

Secondary ways of word formation • Shortening/clipping can be of different types: • initial clipping – the initial part of a word is clipped: phone <= telephone, bus<= omnibus • final clipping — the final part of a word is clipped: vac <= vacations, cab<= cabriolet, lab <= laboratory; • initial and final clipping – frige <= refrigerator; • Acronyms are words made of initial letters of a word group: UNO, BBC, MP, PM, NATO, USA, EU, etc.

Blending • is a way to combine elements of two words to create one, so it includes 2 word building processes: clipping and composition: smog<= smoke + fog, brunch<= breakfast + lunch, Oxbridge<= Oxford + Cambridge; edutainment <= education + entertainment, slanguage <= slang +language, • medicare <= medical care; • •

Back-formation/reversion • is such a way of word building when a new word is produces not by adding an affix to a stem but by subtracting an affix. • It is normally used to create a verb from a noun: • beggar => to beg, • burglar => to burgle, • baby-sitter => to baby-sit, • television =>to televise.

Stress and sound interchange: • import- to import, export – to export, conduct –to conduct; • sing-song, bleed-blood, feed – food. • Lexicalization • is a process of turning a word form into a separate lexical unit: Customs, arms, irons, glasses.

Sound imitation/onomatopoeia • is a way of coining a word by imitating different sounds produced in nature by animals: bark, croak, miaow; people: giggle, gargle, groan; things: crack, etc; • Reduplication – • doubling a stem, either without phonetic changes: bye-bye, or with variation of a root sound: ping-pong, riff-raff (the disreputable elements of society), dilly -dally (wasting time)

• -structure: compounds proper (2 root stems): to job-hunt; • compound-affixed words: videoplayer; • compounds of 3 or more stems: cornflowerblue, singer-songwriter; • compound-shortened words: V-day, motocross, AIDSphobia, motel;

The definition of morphology, word, morpheme. Criteria for the division of morpheme. An average english word model

- The definition of morphology

- The definition of morpheme

- The definition of word

- An average English word model

- Criteria for the division of morpheme

- Morphology is the branch of linguistics that studies the structure of words.

- = the study of how words are built

- = set of morphemes + the rules of how they are combined

- How words are put together out of smaller pieces morphemes

e.g. Replayed consists of re+play+ed

- The morpheme is a meaningful segmental component of the word; the morpheme is formed by phonemes; as a meaningful component of the word it is elementary(i.e. indivisible into smaller segments as regards its significative function)

- The word is nominative unit of language; it is formed by morphemes; it enters the lexicon of language as its elementary component (i.e. A component indivisible into smaller segments as regards its nominative function); together with other nominative units the word is used for the formation of the sentence- a unit of information in the communication process

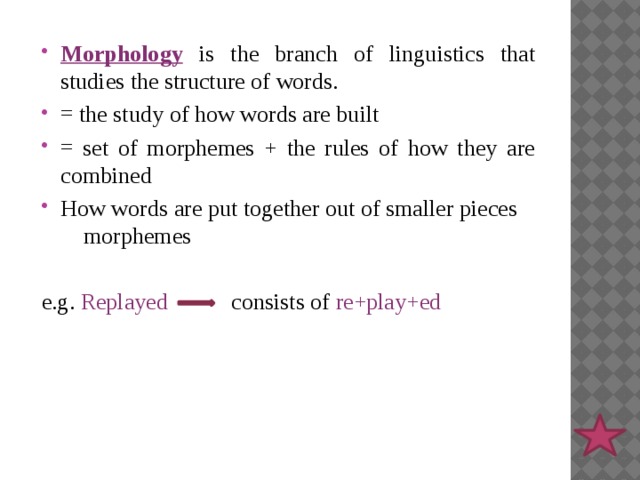

The abstract complete morphemic model of the common English word is the following:

‘ prefix + root + lexical suffix + grammatical suffix’

e.g. prefabricated — W = {[Pr + (R + L)] +Gr};

inheritors — W = {[(Pr + R) +L] + Gr}

* the symbols St for stem, R for root, Pr for prefix, L for lexical suffix, Gr for grammatical suffix

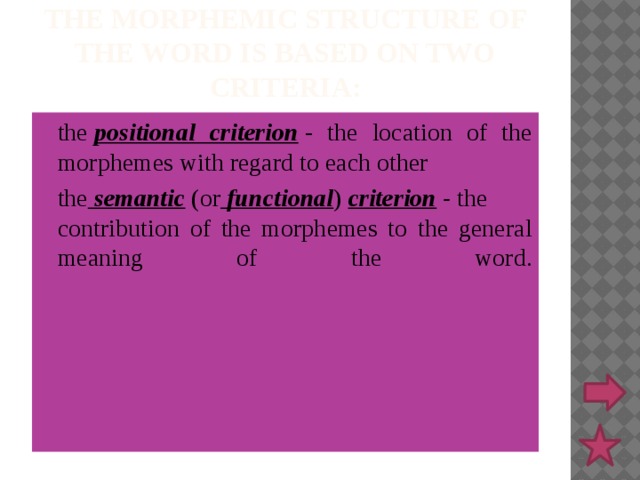

the morphemic structure of the word is based on two criteria:

- the positional criterion — the location of the morphemes with regard to each other

- the semantic (or functional ) criterion — the contribution of the morphemes to the general meaning of the word.

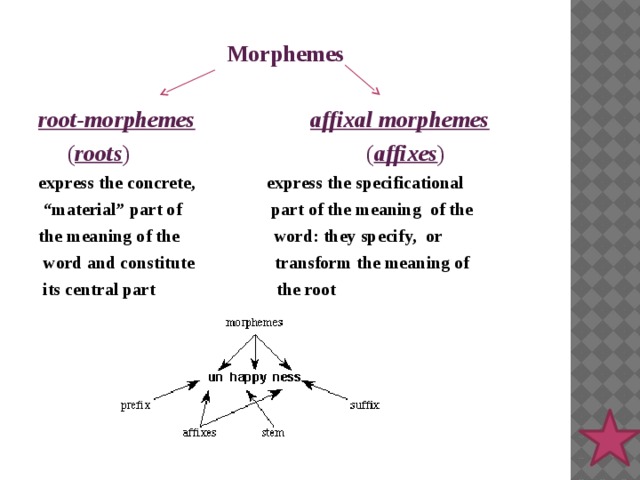

Morphemes

root-morphemes affixal morphemes

( roots ) ( affixes )

express the concrete, express the specificational

“ material” part of part of the meaning of the

the meaning of the word: they specify, or

word and constitute transform the meaning of

its central part the root

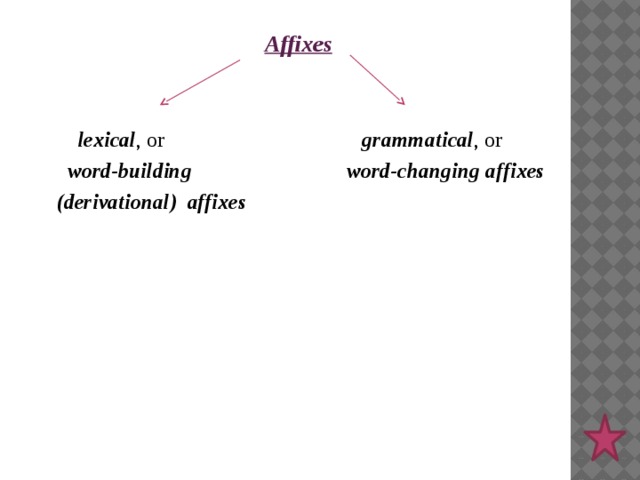

Affixes

lexical , or grammatical , or

word-building word-changing affixes

(derivational) affixes

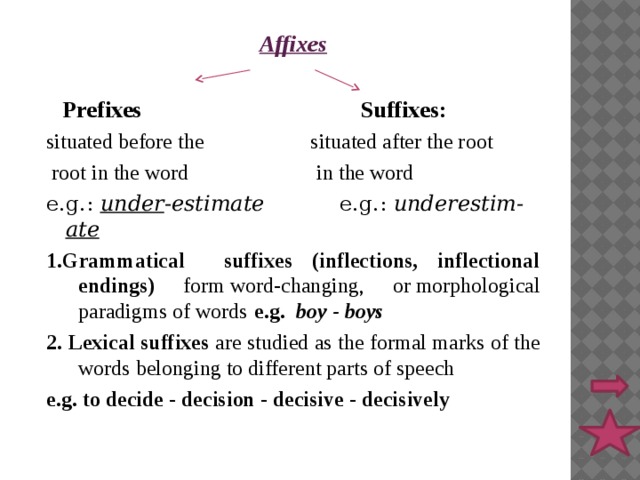

Affixes

Prefixes Suffixes:

situated before the situated after the root

root in the word in the word

e.g.: under -estimate e.g.: underestim- ate

1.Grammatical suffixes (inflections, inflectional endings) form word-changing, or morphological paradigms of words e.g. boy — boys

2. Lexical suffixes are studied as the formal marks of the words belonging to different parts of speech

e.g. to decide — decision — decisive — decisively

![The abstract complete morphemic model of the common English word is the following: ‘ prefix + root + lexical suffix + grammatical suffix’ e.g. prefabricated - W = {[Pr + (R + L)] +Gr}; inheritors - W = {[(Pr + R) +L] + Gr} * the symbols St for stem, R for root, Pr for prefix, L for lexical suffix, Gr for grammatical suffix](https://fsd.multiurok.ru/html/2017/07/02/s_595915a786ce0/img5.jpg)