Asked by: Devon Legros

Score: 4.1/5

(25 votes)

Blues became a code word for a record designed to sell to black listeners. The origins of the blues are closely related to the religious music of Afro-American community, the spirituals.

Are there blues words?

blues Add to list Share. … Since the fourteenth century, the word blue has been used to mean «sad.» The noun blues came into use in the 1700s to describe a state of sadness or melancholy.

What is the true meaning of the blues?

“The blues” stems from the 17th-century English expression, “the blue devils,” which described the intense visual hallucinations of delirium tremens — the trembling and psychosis associated with alcohol withdrawal. Shortened over time to “the blues,” the phrase came to mean a state of emotional agitation or depression.

Why are the blues called blues?

The name of this great American music probably originated with the 17th-century English expression «the blue devils,» for the intense visual hallucinations that can accompany severe alcohol withdrawal. Shortened over time to «the blues,» it came to mean a state of agitation or depression.

How do you use the word blues?

Bliss sentence example

- Many also came with yearning of soul to enjoy the bliss of God. …

- Can you know the bliss of heaven without having never known pain? …

- We wish them a lifetime of wedded bliss together. …

- Reading takes me to eternal bliss where I don’t know where the current is going to take me.

31 related questions found

What is mean by blissed out?

US slang. 1 intransitive : to experience bliss or ecstasy Then he tells us that he longs to run away with Vicki, to marry her and bliss out forever on her good-natured sexiness.—

What does little bliss mean?

Bliss is a state of complete happiness or joy. … Another common association is heaven or paradise, as in eternal bliss. Bliss is from Middle English blisse, from Old English bliss, blīths.

What is the meaning of the word blues and why is it called this?

Etymology. The term Blues may have come from «blue devils», meaning melancholy and sadness; an early use of the term in this sense is in George Colman’s one-act farce Blue Devils (1798).

Where does the expression have the blues come from?

The noun blues, meaning “low spirits,” was first recorded in 1741 and may come from blue devil, a 17th-century term for a baleful demon, or from the adjective blue meaning “sad,” a usage first recorded in Chaucer’s Complaint of Mars (c. 1385).

Who coined the term the blues?

Growth of the blues (1920s onward)

One of the first professional blues singers was Gertrude «Ma» Rainey, who claimed to have coined the term blues. Classic female urban or vaudeville blues singers were popular in the 1920s, among them Mamie Smith, Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Victoria Spivey.

Where the blues is believed to have been born?

The blues grew up in the Mississippi Delta just upriver from New Orleans, the birthplace of jazz. Blues and jazz have always influenced each other, and they still interact in countless ways today. Unlike jazz, the blues didn’t spread out significantly from the South to the Midwest until the 1930s and ’40s.

Is Blues the mother of all music?

The blues are often referred to as the mother of modern musical forms. But where did the blues come from? The blues first grew out of the music of enslaved African Americans (and later African-American sharecroppers, railroad work gangs, and prison work gangs) and described life’s hardships.

Who is known as the father of the blues?

Today’s blog celebrates the career of W.C. Handy. Born in Florence, Alabama on November 16, 1873, William Christopher Handy became interested in music at an early age.

What does blues mean in slang?

noun – uncountable sadness or depression. Citation from “Dumped, But Not Down”, Psychology Today, Carlin Flora, July 01 2007 censored in hope of resolving Google’s penalty against this site. I’ve got the back-to-work blues. See more words with the same meaning: to be sad, disappointed.

What does the word blues mean *?

: a feeling of sadness or depression I’ve got (a case of) the blues.

How do you spell the word blues?

the blues, (used with a plural verb) depressed spirits; despondency; melancholy: This rainy spell is giving me the blues. (used with a singular verb)Jazz.

What’s the difference between having the blues and playing the blues?

The Blues as a Musical Influence and Sound

They are heard both in the singer’s voice and on the instruments playing the blues. Having the blues sound doesn’t necessarily make something “The Blues”. For example, a pop song could have blue notes while not being the blues.

What does catching the blues mean?

informal. to feel sad. SMART Vocabulary: related words and phrases. Feeling sad and unhappy.

What does the phrase I have a fit of the blues mean?

FIT OF THE BLUES. Meaning. Get in to depression, low in your spirits.

Why was Blues considered devil’s music?

Because the early bluesmen and women were the downtrodden illiterate descendants of slaves who were not seen as skilled enough to work as servants or in other reputable functions, blues was not considered respectable. To most blacks, blues was the Devil’s music. …

What does bliss mean in slang?

Extreme happiness; ecstasy. 2. The ecstasy of salvation; spiritual joy. Phrasal Verb: bliss out Slang.

What is the meaning of my bliss?

n. 1 perfect happiness; serene joy. 2 the ecstatic joy of heaven.

What does personal bliss mean?

Bliss may be defined as a natural direction you can take as a way to maximize your sense of joy, fulfillment, and purpose. Sometimes people equate bliss with being in a state of euphoria, but in reality, being blissful is the state you’re in when you’re doing what brings you a deep sense of joy.

How do you use blissed in a sentence?

Just look at the crosseyed blissed out look he gets every time he does it. I’m blissed out at the mountains striking and staggering hugeness. She was so blissed out that she could barely stand, but a moment of true happiness will do that.

What does feeling blissful mean?

If you’re blissful, you’re happy and at peace. You can never have too many blissful moments. If you’re feeling blissful, then you’re lucky. This is a word for total contentment and major happiness, along with a kind of Zen-like peace. … A blissful moment is full of joy and relaxation.

| Blues | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | 1860s,[2] Deep South, U.S. |

| Derivative forms |

|

| Subgenres | |

|

Subgenres

|

|

| Fusion genres | |

|

Fusion genres

|

|

| Regional scenes | |

|

Regional scenes

|

|

| Other topics | |

|

Blues is a music genre[3] and musical form which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s.[2] Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the African-American culture. The blues form is ubiquitous in jazz, rhythm and blues, and rock and roll, and is characterized by the call-and-response pattern, the blues scale, and specific chord progressions, of which the twelve-bar blues is the most common. Blue notes (or «worried notes»), usually thirds, fifths or sevenths flattened in pitch, are also an essential part of the sound. Blues shuffles or walking bass reinforce the trance-like rhythm and form a repetitive effect known as the groove.

Blues, as a genre, is also characterized by its lyrics, bass lines, and instrumentation. Early traditional blues verses consisted of a single line repeated four times. It was only in the first decades of the 20th century that the most common current structure became standard: the AAB pattern, consisting of a line sung over the four first bars, its repetition over the next four, and then a longer concluding line over the last bars. Early blues frequently took the form of a loose narrative, often relating the racial discrimination and other challenges experienced by African-Americans.[4]

Many elements, such as the call-and-response format and the use of blue notes, can be traced back to the music of Africa. The origins of the blues are also closely related to the religious music of the Afro-American community, the spirituals. The first appearance of the blues is often dated to after the ending of slavery and, later, the development of juke joints. It is associated with the newly acquired freedom of the former slaves. Chroniclers began to report about blues music at the dawn of the 20th century. The first publication of blues sheet music was in 1908. Blues has since evolved from unaccompanied vocal music and oral traditions of slaves into a wide variety of styles and subgenres. Blues subgenres include country blues, such as Delta blues and Piedmont blues, as well as urban blues styles such as Chicago blues and West Coast blues. World War II marked the transition from acoustic to electric blues and the progressive opening of blues music to a wider audience, especially white listeners. In the 1960s and 1970s, a hybrid form called blues rock developed, which blended blues styles with rock music.

Etymology[edit]

The term Blues may have originated from «blue devils,» meaning melancholy and sadness. An early use of the term in this sense is in George Colman’s one-act farce Blue Devils (1798).[5] The phrase blue devils may also have been derived from a British usage of the 1600s referring to the «intense visual hallucinations that can accompany severe alcohol withdrawal.»[6] As time went on, the phrase lost the reference to devils and came to mean a state of agitation or depression. By the 1800s in the United States, the term «blues» was associated with drinking alcohol, a meaning which survives in the phrase blue law, which prohibits the sale of alcohol on Sunday.[6]

In 1827, it was in the sense of a sad state of mind that John James Audubon wrote to his wife that he «had the blues.»[7] The phrase «the blues» was written by Charlotte Forten, then aged 25, in her diary on December 14, 1862. She was a free-born black woman from Pennsylvania who was working as a schoolteacher in South Carolina, instructing both slaves and freedmen, and wrote that she «came home with the blues» because she felt lonesome and pitied herself. She overcame her depression and later noted a number of songs, such as «Poor Rosy,» that were popular among the slaves. Although she admitted being unable to describe the manner of singing she heard, Forten wrote that the songs «can’t be sung without a full heart and a troubled spirit,» conditions that have inspired countless blues songs.[8]

Though the use of the phrase in African-American music may be older, it has been attested to in print since 1912, when Hart Wand’s «Dallas Blues» became the first copyrighted blues composition.[9][10] In lyrics, the phrase is often used to describe a depressed mood.[11]

Lyrics[edit]

American blues singer Ma Rainey (1886–1939), the «Mother of the Blues»

Early traditional blues verses often consisted of a single line repeated four times. However, the most common structure of blues lyrics today was established in the first few decades of the 20th century, known as the «AAB» pattern. This structure consists of a line sung over the first four bars, its repetition over the next four, and a longer concluding line over the last bars.[12] This pattern can be heard in some of the first published blues songs, such as «Dallas Blues» (1912) and «Saint Louis Blues» (1914). According to W.C. Handy, the «AAB» pattern was adopted to avoid the monotony of lines repeated three times.[13] The lyrics are often sung in a rhythmic talk style rather than a melody, resembling a form of talking blues.

Early blues frequently took the form of a loose narrative. African-American singers voiced their «personal woes in a world of harsh reality: a lost love, the cruelty of police officers, oppression at the hands of white folk, [and] hard times».[14] This melancholy has led to the suggestion of an Igbo origin for blues because of the reputation the Igbo had throughout plantations in the Americas for their melancholic music and outlook on life when they were enslaved.[15][16]

The lyrics often relate troubles experienced within African American society. For instance Blind Lemon Jefferson’s «Rising High Water Blues» (1927) tells of the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927:

Backwater rising, Southern peoples can’t make no time

I said, backwater rising, Southern peoples can’t make no time

And I can’t get no hearing from that Memphis girl of mine

Although the blues gained an association with misery and oppression, the lyrics could also be humorous and raunchy:[17]

Rebecca, Rebecca, get your big legs off of me,

Rebecca, Rebecca, get your big legs off of me,

It may be sending you baby, but it’s worrying the hell out of me.[18]

Hokum blues celebrated both comedic lyrical content and a boisterous, farcical performance style.[19] Tampa Red and Georgia Tom’s «It’s Tight Like That» (1928)[20] is a sly wordplay with the double meaning of being «tight» with someone, coupled with a more salacious physical familiarity. Blues songs with sexually explicit lyrics were known as dirty blues. The lyrical content became slightly simpler in postwar blues, which tended to focus on relationship woes or sexual worries. Lyrical themes that frequently appeared in prewar blues, such as economic depression, farming, devils, gambling, magic, floods and drought, were less common in postwar blues.[21]

The writer Ed Morales claimed that Yoruba mythology played a part in early blues, citing Robert Johnson’s «Cross Road Blues» as a «thinly veiled reference to Eleggua, the orisha in charge of the crossroads».[22] However, the Christian influence was far more obvious.[23] The repertoires of many seminal blues artists, such as Charley Patton and Skip James, included religious songs or spirituals.[24] Reverend Gary Davis[25] and Blind Willie Johnson[26] are examples of artists often categorized as blues musicians for their music, although their lyrics clearly belong to spirituals.

Form[edit]

The blues form is a cyclic musical form in which a repeating progression of chords mirrors the call and response scheme commonly found in African and African-American music. During the first decades of the 20th century blues music was not clearly defined in terms of a particular chord progression.[27] With the popularity of early performers, such as Bessie Smith, use of the twelve-bar blues spread across the music industry during the 1920s and 30s.[28] Other chord progressions, such as 8-bar forms, are still considered blues; examples include «How Long Blues», «Trouble in Mind», and Big Bill Broonzy’s «Key to the Highway». There are also 16-bar blues, such as Ray Charles’s instrumental «Sweet 16 Bars» and Herbie Hancock’s «Watermelon Man». Idiosyncratic numbers of bars are occasionally used, such as the 9-bar progression in «Sitting on Top of the World», by Walter Vinson.

| Chords played over a 12-bar scheme: | Chords for a blues in C: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

The basic 12-bar lyric framework of a blues composition is reflected by a standard harmonic progression of 12 bars in a 4/4 time signature. The blues chords associated to a twelve-bar blues are typically a set of three different chords played over a 12-bar scheme. They are labeled by Roman numbers referring to the degrees of the progression. For instance, for a blues in the key of C, C is the tonic chord (I) and F is the subdominant (IV).

The last chord is the dominant (V) turnaround, marking the transition to the beginning of the next progression. The lyrics generally end on the last beat of the tenth bar or the first beat of the 11th bar, and the final two bars are given to the instrumentalist as a break; the harmony of this two-bar break, the turnaround, can be extremely complex, sometimes consisting of single notes that defy analysis in terms of chords.

Much of the time, some or all of these chords are played in the harmonic seventh (7th) form. The use of the harmonic seventh interval is characteristic of blues and is popularly called the «blues seven».[29] Blues seven chords add to the harmonic chord a note with a frequency in a 7:4 ratio to the fundamental note. At a 7:4 ratio, it is not close to any interval on the conventional Western diatonic scale.[30] For convenience or by necessity it is often approximated by a minor seventh interval or a dominant seventh chord.

In melody, blues is distinguished by the use of the flattened third, fifth and seventh of the associated major scale.[31]

Blues shuffles or walking bass reinforce the trance-like rhythm and call-and-response, and they form a repetitive effect called a groove. Characteristic of the blues since its Afro-American origins, the shuffles played a central role in swing music.[32] The simplest shuffles, which were the clearest signature of the R&B wave that started in the mid-1940s,[33] were a three-note riff on the bass strings of the guitar. When this riff was played over the bass and the drums, the groove «feel» was created. Shuffle rhythm is often vocalized as «dow, da dow, da dow, da» or «dump, da dump, da dump, da»:[34] it consists of uneven, or «swung», eighth notes. On a guitar this may be played as a simple steady bass or it may add to that stepwise quarter note motion from the fifth to the sixth of the chord and back.

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

Hart Wand’s «Dallas Blues» was published in 1912; W.C. Handy’s «The Memphis Blues» followed in the same year. The first recording by an African American singer was Mamie Smith’s 1920 rendition of Perry Bradford’s «Crazy Blues». But the origins of the blues were some decades earlier, probably around 1890.[35] This music is poorly documented, partly because of racial discrimination in U.S. society, including academic circles,[36] and partly because of the low rate of literacy among rural African Americans at the time.[37]

Reports of blues music in southern Texas and the Deep South were written at the dawn of the 20th century. Charles Peabody mentioned the appearance of blues music at Clarksdale, Mississippi, and Gate Thomas reported similar songs in southern Texas around 1901–1902. These observations coincide more or less with the recollections of Jelly Roll Morton, who said he first heard blues music in New Orleans in 1902; Ma Rainey, who remembered first hearing the blues in the same year in Missouri; and W.C. Handy, who first heard the blues in Tutwiler, Mississippi, in 1903. The first extensive research in the field was performed by Howard W. Odum, who published an anthology of folk songs from Lafayette County, Mississippi, and Newton County, Georgia, between 1905 and 1908.[38] The first noncommercial recordings of blues music, termed proto-blues by Paul Oliver, were made by Odum for research purposes at the very beginning of the 20th century. They are now lost.[39]

Other recordings that are still available were made in 1924 by Lawrence Gellert. Later, several recordings were made by Robert W. Gordon, who became head of the Archive of American Folk Songs of the Library of Congress. Gordon’s successor at the library was John Lomax. In the 1930s, Lomax and his son Alan made a large number of non-commercial blues recordings that testify to the huge variety of proto-blues styles, such as field hollers and ring shouts.[40] A record of blues music as it existed before 1920 can also be found in the recordings of artists such as Lead Belly[41] and Henry Thomas.[42] All these sources show the existence of many different structures distinct from twelve-, eight-, or sixteen-bar.[43][44]

The social and economic reasons for the appearance of the blues are not fully known.[45] The first appearance of the blues is usually dated after the Emancipation Act of 1863,[36] between 1860s and 1890s,[2] a period that coincides with post-emancipation and later, the establishment of juke joints as places where African-Americans went to listen to music, dance, or gamble after a hard day’s work. This period corresponds to the transition from slavery to sharecropping, small-scale agricultural production, and the expansion of railroads in the southern United States. Several scholars characterize the development of blues music in the early 1900s as a move from group performance to individualized performance. They argue that the development of the blues is associated with the newly acquired freedom of the enslaved people.[47]

According to Lawrence Levine, «there was a direct relationship between the national ideological emphasis upon the individual, the popularity of Booker T. Washington’s teachings, and the rise of the blues.» Levine stated that «psychologically, socially, and economically, African-Americans were being acculturated in a way that would have been impossible during slavery, and it is hardly surprising that their secular music reflected this as much as their religious music did.»[47]

There are few characteristics common to all blues music, because the genre took its shape from the idiosyncrasies of individual performers.[48] However, there are some characteristics that were present long before the creation of the modern blues. Call-and-response shouts were an early form of blues-like music; they were a «functional expression … style without accompaniment or harmony and unbounded by the formality of any particular musical structure».[49] A form of this pre-blues was heard in slave ring shouts and field hollers, expanded into «simple solo songs laden with emotional content».[50]

Blues has evolved from the unaccompanied vocal music and oral traditions of slaves imported from West Africa and rural blacks into a wide variety of styles and subgenres, with regional variations across the United States. Although blues (as it is now known) can be seen as a musical style based on both European harmonic structure and the African call-and-response tradition that transformed into an interplay of voice and guitar,[51][52] the blues form itself bears no resemblance to the melodic styles of the West African griots.[53][54] Additionally, there are theories that the four-beats-per-measure structure of the blues might have its origins in the Native American tradition of pow wow drumming.[55] Some scholars identify strong influences on the blues from the melodic structures of certain West African musical styles of the savanna and sahel. Lucy Durran finds similarities with the melodies of the Bambara people, and to a lesser degree, the Soninke people and Wolof people, but not as much of the Mandinka people.[56] Gerard Kubik finds similarities to the melodic styles of both the west African savanna and central Africa, both of which were sources of slaves.[57]

No specific African musical form can be identified as the single direct ancestor of the blues.[58] However the call-and-response format can be traced back to the music of Africa. That blue notes predate their use in blues and have an African origin is attested to by «A Negro Love Song», by the English composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, from his African Suite for Piano, written in 1898, which contains blue third and seventh notes.[59]

The Diddley bow (a homemade one-stringed instrument found in parts of the American South sometimes referred to as a jitterbug or a one-string in the early twentieth century) and the banjo are African-derived instruments that may have helped in the transfer of African performance techniques into the early blues instrumental vocabulary.[60] The banjo seems to be directly imported from West African music. It is similar to the musical instrument that griots and other Africans such as the Igbo[61] played (called halam or akonting by African peoples such as the Wolof, Fula and Mandinka).[62] However, in the 1920s, when country blues began to be recorded, the use of the banjo in blues music was quite marginal and limited to individuals such as Papa Charlie Jackson and later Gus Cannon.[63]

Blues music also adopted elements from the «Ethiopian airs», minstrel shows and Negro spirituals, including instrumental and harmonic accompaniment.[64] The style also was closely related to ragtime, which developed at about the same time, though the blues better preserved «the original melodic patterns of African music».[65]

The musical forms and styles that are now considered the blues as well as modern country music arose in the same regions of the southern United States during the 19th century. Recorded blues and country music can be found as far back as the 1920s, when the record industry created the marketing categories «race music» and «hillbilly music» to sell music by blacks for blacks and by whites for whites, respectively. At the time, there was no clear musical division between «blues» and «country», except for the ethnicity of the performer, and even that was sometimes documented incorrectly by record companies.[66][67]

Though musicologists can now attempt to define the blues narrowly in terms of certain chord structures and lyric forms thought to have originated in West Africa, audiences originally heard the music in a far more general way: it was simply the music of the rural south, notably the Mississippi Delta. Black and white musicians shared the same repertoire and thought of themselves as «songsters» rather than blues musicians. The notion of blues as a separate genre arose during the black migration from the countryside to urban areas in the 1920s and the simultaneous development of the recording industry. Blues became a code word for a record designed to sell to black listeners.[68]

The origins of the blues are closely related to the religious music of Afro-American community, the spirituals. The origins of spirituals go back much further than the blues, usually dating back to the middle of the 18th century, when the slaves were Christianized and began to sing and play Christian hymns, in particular those of Isaac Watts, which were very popular.[69] Before the blues gained its formal definition in terms of chord progressions, it was defined as the secular counterpart of spirituals. It was the low-down music played by rural blacks.[23]

Depending on the religious community a musician belonged to, it was more or less considered a sin to play this low-down music: blues was the devil’s music. Musicians were therefore segregated into two categories: gospel singers and blues singers, guitar preachers and songsters. However, when rural black music began to be recorded in the 1920s, both categories of musicians used similar techniques: call-and-response patterns, blue notes, and slide guitars. Gospel music was nevertheless using musical forms that were compatible with Christian hymns and therefore less marked by the blues form than its secular counterpart.[23]

Pre-war blues[edit]

The American sheet music publishing industry produced a great deal of ragtime music. By 1912, the sheet music industry had published three popular blues-like compositions, precipitating the Tin Pan Alley adoption of blues elements: «Baby Seals’ Blues», by «Baby» Franklin Seals (arranged by Artie Matthews); «Dallas Blues», by Hart Wand; and «The Memphis Blues», by W.C. Handy.[70]

Handy was a formally trained musician, composer and arranger who helped to popularize the blues by transcribing and orchestrating blues in an almost symphonic style, with bands and singers. He became a popular and prolific composer, and billed himself as the «Father of the Blues»; however, his compositions can be described as a fusion of blues with ragtime and jazz, a merger facilitated using the Cuban habanera rhythm that had long been a part of ragtime;[22][71] Handy’s signature work was the «Saint Louis Blues».

In the 1920s, the blues became a major element of African American and American popular music, also reaching white audiences via Handy’s arrangements and the classic female blues performers. These female performers became perhaps the first African American «superstars», and their recording sales demonstrated «a huge appetite for records made by and for black people.»[72] The blues evolved from informal performances in bars to entertainment in theaters. Blues performances were organized by the Theater Owners Bookers Association in nightclubs such as the Cotton Club and juke joints such as the bars along Beale Street in Memphis. Several record companies, such as the American Record Corporation, Okeh Records, and Paramount Records, began to record African-American music.

As the recording industry grew, country blues performers like Bo Carter, Jimmie Rodgers, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lonnie Johnson, Tampa Red and Blind Blake became more popular in the African American community. Kentucky-born Sylvester Weaver was in 1923 the first to record the slide guitar style, in which a guitar is fretted with a knife blade or the sawed-off neck of a bottle.[73] The slide guitar became an important part of the Delta blues.[74] The first blues recordings from the 1920s are categorized as a traditional, rural country blues and a more polished city or urban blues.

Country blues performers often improvised, either without accompaniment or with only a banjo or guitar. Regional styles of country blues varied widely in the early 20th century. The (Mississippi) Delta blues was a rootsy sparse style with passionate vocals accompanied by slide guitar. The little-recorded Robert Johnson[75] combined elements of urban and rural blues. In addition to Robert Johnson, influential performers of this style included his predecessors Charley Patton and Son House. Singers such as Blind Willie McTell and Blind Boy Fuller performed in the southeastern «delicate and lyrical» Piedmont blues tradition, which used an elaborate ragtime-based fingerpicking guitar technique. Georgia also had an early slide tradition,[76] with Curley Weaver, Tampa Red, «Barbecue Bob» Hicks and James «Kokomo» Arnold as representatives of this style.[77]

The lively Memphis blues style, which developed in the 1920s and 1930s near Memphis, Tennessee, was influenced by jug bands such as the Memphis Jug Band or the Gus Cannon’s Jug Stompers. Performers such as Frank Stokes, Sleepy John Estes, Robert Wilkins, Joe McCoy, Casey Bill Weldon and Memphis Minnie used a variety of unusual instruments such as washboard, fiddle, kazoo or mandolin. Memphis Minnie was famous for her virtuoso guitar style. Pianist Memphis Slim began his career in Memphis, but his distinct style was smoother and had some swing elements. Many blues musicians based in Memphis moved to Chicago in the late 1930s or early 1940s and became part of the urban blues movement.[78][79]

Bessie Smith, an early blues singer, known for her powerful voice

Urban blues[edit]

City or urban blues styles were more codified and elaborate, as a performer was no longer within their local, immediate community, and had to adapt to a larger, more varied audience’s aesthetic.[80] Classic female urban and vaudeville blues singers were popular in the 1920s, among them «the big three»—Gertrude «Ma» Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Lucille Bogan. Mamie Smith, more a vaudeville performer than a blues artist, was the first African American to record a blues song in 1920; her second record, «Crazy Blues», sold 75,000 copies in its first month.[81] Ma Rainey, the «Mother of Blues», and Bessie Smith each «[sang] around center tones, perhaps in order to project her voice more easily to the back of a room». Smith would «sing a song in an unusual key, and her artistry in bending and stretching notes with her beautiful, powerful contralto to accommodate her own interpretation was unsurpassed».[82]

In 1920, the vaudeville singer Lucille Hegamin became the second black woman to record blues when she recorded «The Jazz Me Blues»,[83] and Victoria Spivey, sometimes called Queen Victoria or Za Zu Girl, had a recording career that began in 1926 and spanned forty years. These recordings were typically labeled «race records» to distinguish them from records sold to white audiences. Nonetheless, the recordings of some of the classic female blues singers were purchased by white buyers as well.[84] These blueswomen’s contributions to the genre included «increased improvisation on melodic lines, unusual phrasing which altered the emphasis and impact of the lyrics, and vocal dramatics using shouts, groans, moans, and wails. The blues women thus effected changes in other types of popular singing that had spin-offs in jazz, Broadway musicals, torch songs of the 1930s and 1940s, gospel, rhythm and blues, and eventually rock and roll.»[85]

Urban male performers included popular black musicians of the era, such as Tampa Red, Big Bill Broonzy and Leroy Carr. An important label of this era was the Chicago-based Bluebird Records. Before World War II, Tampa Red was sometimes referred to as «the Guitar Wizard». Carr accompanied himself on the piano with Scrapper Blackwell on guitar, a format that continued well into the 1950s with artists such as Charles Brown and even Nat «King» Cole.[74]

Boogie-woogie was another important style of 1930s and early 1940s urban blues. While the style is often associated with solo piano, boogie-woogie was also used to accompany singers and, as a solo part, in bands and small combos. Boogie-Woogie style was characterized by a regular bass figure, an ostinato or riff and shifts of level in the left hand, elaborating each chord and trills and decorations in the right hand. Boogie-woogie was pioneered by the Chicago-based Jimmy Yancey and the Boogie-Woogie Trio (Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson and Meade Lux Lewis).[86] Chicago boogie-woogie performers included Clarence «Pine Top» Smith and Earl Hines, who «linked the propulsive left-hand rhythms of the ragtime pianists with melodic figures similar to those of Armstrong’s trumpet in the right hand».[80] The smooth Louisiana style of Professor Longhair and, more recently, Dr. John blends classic rhythm and blues with blues styles.

Another development in this period was big band blues. The «territory bands» operating out of Kansas City, the Bennie Moten orchestra, Jay McShann, and the Count Basie Orchestra were also concentrating on the blues, with 12-bar blues instrumentals such as Basie’s «One O’Clock Jump» and «Jumpin’ at the Woodside» and boisterous «blues shouting» by Jimmy Rushing on songs such as «Going to Chicago» and «Sent for You Yesterday». A well-known big band blues tune is Glenn Miller’s «In the Mood». In the 1940s, the jump blues style developed. Jump blues grew up from the boogie woogie wave and was strongly influenced by big band music. It uses saxophone or other brass instruments and the guitar in the rhythm section to create a jazzy, up-tempo sound with declamatory vocals. Jump blues tunes by Louis Jordan and Big Joe Turner, based in Kansas City, Missouri, influenced the development of later styles such as rock and roll and rhythm and blues.[87] Dallas-born T-Bone Walker, who is often associated with the California blues style,[88] performed a successful transition from the early urban blues à la Lonnie Johnson and Leroy Carr to the jump blues style and dominated the blues-jazz scene at Los Angeles during the 1940s.[89]

1950s[edit]

The transition from country blues to urban blues that began in the 1920s was driven by the successive waves of economic crisis and booms that led many rural blacks to move to urban areas, in a movement known as the Great Migration. The long boom following World War II induced another massive migration of the African-American population, the Second Great Migration, which was accompanied by a significant increase of the real income of the urban blacks. The new migrants constituted a new market for the music industry. The term race record, initially used by the music industry for African-American music, was replaced by the term rhythm and blues. This rapidly evolving market was mirrored by Billboard magazine’s Rhythm & Blues chart. This marketing strategy reinforced trends in urban blues music such as the use of electric instruments and amplification and the generalization of the blues beat, the blues shuffle, which became ubiquitous in rhythm and blues (R&B). This commercial stream had important consequences for blues music, which, together with jazz and gospel music, became a component of R&B.[90]

After World War II, new styles of electric blues became popular in cities such as Chicago,[91] Memphis,[92] Detroit[93][94] and St. Louis. Electric blues used electric guitars, double bass (gradually replaced by bass guitar), drums, and harmonica (or «blues harp») played through a microphone and a PA system or an overdriven guitar amplifier. Chicago became a center for electric blues from 1948 on, when Muddy Waters recorded his first success, «I Can’t Be Satisfied».[95] Chicago blues is influenced to a large extent by Delta blues, because many performers had migrated from the Mississippi region.

Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon and Jimmy Reed were all born in Mississippi and moved to Chicago during the Great Migration. Their style is characterized by the use of electric guitar, sometimes slide guitar, harmonica, and a rhythm section of bass and drums.[96] The saxophonist J. T. Brown played in bands led by Elmore James and by J. B. Lenoir, but the saxophone was used as a backing instrument for rhythmic support more than as a lead instrument.

Little Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson (Rice Miller) and Sonny Terry are well known harmonica (called «harp» by blues musicians) players of the early Chicago blues scene. Other harp players such as Big Walter Horton were also influential. Muddy Waters and Elmore James were known for their innovative use of slide electric guitar. Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters were known for their deep, «gravelly» voices.

The bassist and prolific songwriter and composer Willie Dixon played a major role on the Chicago blues scene. He composed and wrote many standard blues songs of the period, such as «Hoochie Coochie Man», «I Just Want to Make Love to You» (both penned for Muddy Waters) and, «Wang Dang Doodle» and «Back Door Man» for Howlin’ Wolf. Most artists of the Chicago blues style recorded for the Chicago-based Chess Records and Checker Records labels. Smaller blues labels of this era included Vee-Jay Records and J.O.B. Records. During the early 1950s, the dominating Chicago labels were challenged by Sam Phillips’ Sun Records company in Memphis, which recorded B. B. King and Howlin’ Wolf before he moved to Chicago in 1960.[97] After Phillips discovered Elvis Presley in 1954, the Sun label turned to the rapidly expanding white audience and started recording mostly rock ‘n’ roll.[98]

In the 1950s, blues had a huge influence on mainstream American popular music. While popular musicians like Bo Diddley[93] and Chuck Berry,[99] both recording for Chess, were influenced by the Chicago blues, their enthusiastic playing styles departed from the melancholy aspects of blues. Chicago blues also influenced Louisiana’s zydeco music,[100] with Clifton Chenier[101] using blues accents. Zydeco musicians used electric solo guitar and cajun arrangements of blues standards.

In England, electric blues took root there during a much acclaimed Muddy Waters tour in 1958. Waters, unsuspecting of his audience’s tendency towards skiffle, an acoustic, softer brand of blues, turned up his amp and started to play his Chicago brand of electric blues. Although the audience was largely jolted by the performance, the performance influenced local musicians such as Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies to emulate this louder style, inspiring the British Invasion of the Rolling Stones and the Yardbirds.[102]

In the late 1950s, a new blues style emerged on Chicago’s West Side pioneered by Magic Sam, Buddy Guy and Otis Rush on Cobra Records.[103] The «West Side sound» had strong rhythmic support from a rhythm guitar, bass guitar and drums and as perfected by Guy, Freddie King, Magic Slim and Luther Allison was dominated by amplified electric lead guitar.[104][105] Expressive guitar solos were a key feature of this music.

Other blues artists, such as John Lee Hooker, had influences not directly related to the Chicago style. John Lee Hooker’s blues is more «personal», based on Hooker’s deep rough voice accompanied by a single electric guitar. Though not directly influenced by boogie woogie, his «groovy» style is sometimes called «guitar boogie». His first hit, «Boogie Chillen», reached number 1 on the R&B charts in 1949.[106]

By the late 1950s, the swamp blues genre developed near Baton Rouge, with performers such as Lightnin’ Slim,[107] Slim Harpo,[108] Sam Myers and Jerry McCain around the producer J. D. «Jay» Miller and the Excello label. Strongly influenced by Jimmy Reed, swamp blues has a slower pace and a simpler use of the harmonica than the Chicago blues style performers such as Little Walter or Muddy Waters. Songs from this genre include «Scratch my Back», «She’s Tough» and «I’m a King Bee». Alan Lomax’s recordings of Mississippi Fred McDowell would eventually bring him wider attention on both the blues and folk circuit, with McDowell’s droning style influencing North Mississippi hill country blues musicians.[109]

1960s and 1970s[edit]

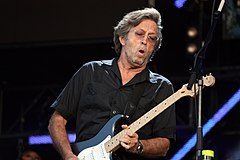

Blues legend B.B. King with his guitar, «Lucille»

By the beginning of the 1960s, genres influenced by African American music such as rock and roll and soul were part of mainstream popular music. White performers such as the Rolling Stones and the Beatles had brought African-American music to new audiences, within the U.S. and abroad. However, the blues wave that brought artists such as Muddy Waters to the foreground had stopped. Bluesmen such as Big Bill Broonzy and Willie Dixon started looking for new markets in Europe. Dick Waterman and the blues festivals he organized in Europe played a major role in propagating blues music abroad. In the UK, bands emulated U.S. blues legends, and UK blues rock-based bands had an influential role throughout the 1960s.[110]

Blues performers such as John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters continued to perform to enthusiastic audiences, inspiring new artists steeped in traditional blues, such as New York–born Taj Mahal. John Lee Hooker blended his blues style with rock elements and playing with younger white musicians, creating a musical style that can be heard on the 1971 album Endless Boogie. B. B. King’s singing and virtuoso guitar technique earned him the eponymous title «king of the blues». King introduced a sophisticated style of guitar soloing based on fluid string bending and shimmering vibrato that influenced many later electric blues guitarists.[111] In contrast to the Chicago style, King’s band used strong brass support from a saxophone, trumpet, and trombone, instead of using slide guitar or harp. Tennessee-born Bobby «Blue» Bland, like B. B. King, also straddled the blues and R&B genres. During this period, Freddie King and Albert King often played with rock and soul musicians (Eric Clapton and Booker T & the MGs) and had a major influence on those styles of music.

The music of the civil rights movement[112] and Free Speech Movement in the U.S. prompted a resurgence of interest in American roots music and early African American music. As well festivals such as the Newport Folk Festival[113] brought traditional blues to a new audience, which helped to revive interest in prewar acoustic blues and performers such as Son House, Mississippi John Hurt, Skip James, and Reverend Gary Davis.[112] Many compilations of classic prewar blues were republished by the Yazoo Records. J. B. Lenoir from the Chicago blues movement in the 1950s recorded several LPs using acoustic guitar, sometimes accompanied by Willie Dixon on the acoustic bass or drums. His songs, originally distributed only in Europe,[114] commented on political issues such as racism or Vietnam War issues, which was unusual for this period. His album Alabama Blues contained a song with the following lyric:

I never will go back to Alabama, that is not the place for me,

I never will go back to Alabama, that is not the place for me.

You know they killed my sister and my brother

and the whole world let them peoples go down there free

White audiences’ interest in the blues during the 1960s increased due to the Chicago-based Paul Butterfield Blues Band featuring guitarist Michael Bloomfield and singer/songwriter Nick Gravenites, and the British blues movement. The style of British blues developed in the UK, when musicians such as Cyril Davies, Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, Fleetwood Mac, John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers, the Rolling Stones, Animals, the Yardbirds, Aynsley Dunbar Retaliation,[115] Chicken Shack,[116] early Jethro Tull, Cream and the Irish musician Rory Gallagher performed classic blues songs from the Delta or Chicago blues traditions.

In 1963, LeRoi Jones, later known as Amiri Baraka, was the first to write a book on the social history of the blues in Blues People: The Negro Music in White America. The British and blues musicians of the early 1960s inspired a number of American blues rock performers, including Canned Heat, Janis Joplin, Johnny Winter, The J. Geils Band, Ry Cooder, and the Allman Brothers Band. One blues rock performer, Jimi Hendrix, was a rarity in his field at the time: a black man who played psychedelic rock. Hendrix was a skilled guitarist, and a pioneer in the innovative use of distortion and audio feedback in his music.[117] Through these artists and others, blues music influenced the development of rock music. Later in the 1960s, British singer Jo Ann Kelly started her recording career. In the US, from the 1970s, female singers Bonnie Raitt and Phoebe Snow performed blues.[118]

In the early 1970s, the Texas rock-blues style emerged, which used guitars in both solo and rhythm roles. In contrast with the West Side blues, the Texas style is strongly influenced by the British rock-blues movement. Major artists of the Texas style are Johnny Winter, Stevie Ray Vaughan, the Fabulous Thunderbirds (led by harmonica player and singer-songwriter Kim Wilson), and ZZ Top. These artists all began their musical careers in the 1970s but they did not achieve international success until the next decade.[119]

1980s to the present[edit]

Italian singer Zucchero is credited as the «Father of Italian Blues«, and is among the few European blues artists who still enjoy international success.[120]

Since the 1980s there has been a resurgence of interest in the blues among a certain part of the African-American population, particularly around Jackson, Mississippi and other deep South regions. Often termed «soul blues» or «Southern soul», the music at the heart of this movement was given new life by the unexpected success of two particular recordings on the Jackson-based Malaco label:[121] Z. Z. Hill’s Down Home Blues (1982) and Little Milton’s The Blues is Alright (1984). Contemporary African-American performers who work in this style of the blues include Bobby Rush, Denise LaSalle, Sir Charles Jones, Bettye LaVette, Marvin Sease, Peggy Scott-Adams, Mel Waiters, Clarence Carter, Dr. «Feelgood» Potts, O.B. Buchana, Ms. Jody, Shirley Brown, and dozens of others.

During the 1980s blues also continued in both traditional and new forms. In 1986 the album Strong Persuader announced Robert Cray as a major blues artist. The first Stevie Ray Vaughan recording Texas Flood was released in 1983, and the Texas-based guitarist exploded onto the international stage. John Lee Hooker’s popularity was revived with the album The Healer in 1989. Eric Clapton, known for his performances with the Blues Breakers and Cream, made a comeback in the 1990s with his album Unplugged, in which he played some standard blues numbers on acoustic guitar.

However, beginning in the 1990s, digital multitrack recording and other technological advances and new marketing strategies including video clip production increased costs, challenging the spontaneity and improvisation that are an important component of blues music.[122] In the 1980s and 1990s, blues publications such as Living Blues and Blues Revue were launched, major cities began forming blues societies, outdoor blues festivals became more common, and[123] more nightclubs and venues for blues emerged.[124] Tedeschi Trucks band and Gov’t Mule released blues rock albums. Female blues singers such as Bonnie Raitt, Susan Tedeschi, Sue Foley and Shannon Curfman recorded blues also.

In the 1990s, the largely ignored hill country blues gained minor recognition in both blues and alternative rock music circles with northern Mississippi artists R. L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough.[109] Blues performers explored a range of musical genres, as can be seen, for example, from the broad array of nominees of the yearly Blues Music Awards, previously named W.C. Handy Awards[125] or of the Grammy Awards for Best Contemporary and Traditional Blues Album. The Billboard Blues Album chart provides an overview of current blues hits. Contemporary blues music is nurtured by several blues labels such as: Alligator Records, Ruf Records, Severn Records, Chess Records (MCA), Delmark Records, NorthernBlues Music, Fat Possum Records and Vanguard Records (Artemis Records). Some labels are famous for rediscovering and remastering blues rarities, including Arhoolie Records, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings (heir of Folkways Records), and Yazoo Records (Shanachie Records).[126]

Musical impact[edit]

Blues musical styles, forms (12-bar blues), melodies, and the blues scale have influenced many other genres of music, such as rock and roll, jazz, and popular music.[127] Prominent jazz, folk or rock performers, such as Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, and Bob Dylan have performed significant blues recordings. The blues scale is often used in popular songs like Harold Arlen’s «Blues in the Night», blues ballads like «Since I Fell for You» and «Please Send Me Someone to Love», and even in orchestral works such as George Gershwin’s «Rhapsody in Blue» and «Concerto in F». Gershwin’s second «Prelude» for solo piano is an interesting example of a classical blues, maintaining the form with academic strictness. The blues scale is ubiquitous in modern popular music and informs many modal frames, especially the ladder of thirds used in rock music (for example, in «A Hard Day’s Night»). Blues forms are used in the theme to the televised Batman, teen idol Fabian Forte’s hit, «Turn Me Loose», country music star Jimmie Rodgers’ music, and guitarist/vocalist Tracy Chapman’s hit «Give Me One Reason».

«Blues singing is about emotion. Its influence on popular singing has been so widespread that, at least among males, singing and emoting have become almost identical—it is a matter of projection rather than hitting the notes.»[128]

—Robert Christgau, 1972

Early country bluesmen such as Skip James, Charley Patton, Georgia Tom Dorsey played country and urban blues and had influences from spiritual singing. Dorsey helped to popularize Gospel music.[129] Gospel music developed in the 1930s, with the Golden Gate Quartet. In the 1950s, soul music by Sam Cooke, Ray Charles and James Brown used gospel and blues music elements. In the 1960s and 1970s, gospel and blues were merged in soul blues music. Funk music of the 1970s was influenced by soul; funk can be seen as an antecedent of hip-hop and contemporary R&B.

R&B music can be traced back to spirituals and blues. Musically, spirituals were a descendant of New England choral traditions, and in particular of Isaac Watts’s hymns, mixed with African rhythms and call-and-response forms. Spirituals or religious chants in the African-American community are much better documented than the «low-down» blues. Spiritual singing developed because African-American communities could gather for mass or worship gatherings, which were called camp meetings.

Edward P. Comentale has noted how the blues was often used as a medium for art or self-expression, stating: «As heard from Delta shacks to Chicago tenements to Harlem cabarets, the blues proved—despite its pained origins—a remarkably flexible medium and a new arena for the shaping of identity and community.»[130]

Before World War II, the boundaries between blues and jazz were less clear. Usually, jazz had harmonic structures stemming from brass bands, whereas blues had blues forms such as the 12-bar blues. However, the jump blues of the 1940s mixed both styles. After WWII, blues had a substantial influence on jazz. Bebop classics, such as Charlie Parker’s «Now’s the Time», used the blues form with the pentatonic scale and blue notes.

Bebop marked a major shift in the role of jazz, from a popular style of music for dancing to a «high-art», less-accessible, cerebral «musician’s music». The audience for both blues and jazz split, and the border between blues and jazz became more defined.[131][132]

The blues’ 12-bar structure and the blues scale was a major influence on rock and roll music. Rock and roll has been called «blues with a backbeat»; Carl Perkins called rockabilly «blues with a country beat». Rockabillies were also said to be 12-bar blues played with a bluegrass beat. «Hound Dog», with its unmodified 12-bar structure (in both harmony and lyrics) and a melody centered on flatted third of the tonic (and flatted seventh of the subdominant), is a blues song transformed into a rock and roll song. Jerry Lee Lewis’s style of rock and roll was heavily influenced by the blues and its derivative boogie-woogie. His style of music was not exactly rockabilly but it has been often called real rock and roll (this is a label he shares with several African American rock and roll performers).[133][134]

Many early rock and roll songs are based on blues: «That’s All Right Mama», «Johnny B. Goode», «Blue Suede Shoes», «Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin On», «Shake, Rattle, and Roll», and «Long Tall Sally». The early African American rock musicians retained the sexual themes and innuendos of blues music: «Got a gal named Sue, knows just what to do» («Tutti Frutti», Little Richard) or «See the girl with the red dress on, She can do the Birdland all night long» («What’d I Say», Ray Charles). The 12-bar blues structure can be found even in novelty pop songs, such as Bob Dylan’s «Obviously Five Believers» and Esther and Abi Ofarim’s «Cinderella Rockefella».

Early country music was infused with the blues.[135] Jimmie Rodgers, Moon Mullican, Bob Wills, Bill Monroe and Hank Williams have all described themselves as blues singers and their music has a blues feel that is different, at first glance at least, from the later country-pop of artists like Eddy Arnold. Yet, if one looks back further, Arnold also started out singing bluesy songs like ‘I’ll Hold You in My Heart’. A lot of the 1970s-era «outlaw» country music by Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings also borrowed from the blues. When Jerry Lee Lewis returned to country music after the decline of 1950s style rock and roll, he sang with a blues feel and often included blues standards on his albums.

In popular culture[edit]

The music of Taj Mahal for the 1972 movie Sounder marked a revival of interest in acoustic blues.

Like jazz, rock and roll, heavy metal music, hip hop music, reggae, country music, Latin music, funk, and pop music, blues has been accused of being the «devil’s music» and of inciting violence and other poor behavior.[136] In the early 20th century, the blues was considered disreputable, especially as white audiences began listening to the blues during the 1920s.[71] In the early twentieth century, W.C. Handy was the first to popularize blues-influenced music among non-black Americans.

During the blues revival of the 1960s and 1970s, acoustic blues artist Taj Mahal and Texas bluesman Lightnin’ Hopkins wrote and performed music that figured prominently in the critically acclaimed film Sounder (1972). The film earned Mahal a Grammy nomination for Best Original Score Written for a Motion Picture and a BAFTA nomination.[137] Almost 30 years later, Mahal wrote blues for, and performed a banjo composition, claw-hammer style, in the 2001 movie release Songcatcher, which focused on the story of the preservation of the roots music of Appalachia.

Perhaps the most visible example of the blues style of music in the late 20th century came in 1980, when Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi released the film The Blues Brothers. The film drew many of the biggest living influencers of the rhythm and blues genre together, such as Ray Charles, James Brown, Cab Calloway, Aretha Franklin, and John Lee Hooker. The band formed also began a successful tour under the Blues Brothers marquee. 1998 brought a sequel, Blues Brothers 2000 that, while not holding as great a critical and financial success, featured a much larger number of blues artists, such as B.B. King, Bo Diddley, Erykah Badu, Eric Clapton, Steve Winwood, Charlie Musselwhite, Blues Traveler, Jimmie Vaughan, and Jeff Baxter.

In 2003, Martin Scorsese made significant efforts to promote the blues to a larger audience. He asked several famous directors such as Clint Eastwood and Wim Wenders to participate in a series of documentary films for PBS called The Blues.[138] He also participated in the rendition of compilations of major blues artists in a series of high-quality CDs. Blues guitarist and vocalist Keb’ Mo’ performed his blues rendition of «America, the Beautiful» in 2006 to close out the final season of the television series The West Wing.

The blues was highlighted in season 2012, episode 1 of In Performance at the White House, entitled «Red, White and Blues». Hosted by Barack and Michelle Obama, the show featured performances by B.B. King, Buddy Guy, Gary Clark Jr., Jeff Beck, Derek Trucks, Keb Mo, and others.[139]

See also[edit]

- List of blues festivals

- List of blues musicians

- List of blues standards

References[edit]

- ^ «BBC – GCSE Bitesize: Origins of the blues». BBC. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c «The Historical Roots of Blues Music». African American Intellectual History Society. May 9, 2018. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- ^ Kunzler’s dictionary of jazz provides two separate entries: «blues», and the «blues form», a widespread musical form (p. 131). Kunzler, Martin (1988). Jazz-Lexicon. Hamburg: Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag.

- ^ «Honoring Jazz: An Early American Art Form». www.civilrightsmuseum.org. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ The «Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé» provides this etymology of blues and cites Colman’s farce as the first appearance of the term in the English language; see «Blues» (in French). Centre Nationale de Ressources Textuelles et Lixicales. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- ^ a b Devi, Debra (2013). «Why Is the Blues Called the ‘Blues’?» Huffington Post, 4 January 2013. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ Rhodes, Richard (2006). John James Audubon: The Making of an American. Random House. p. 302. ISBN 9780375713934.

- ^ Paul Oliver (1969), The Story of the Blues, Barrie & Rockliff, page 8.

- ^ Davis, Francis (1995). The History of the Blues. New York: Hyperion.

- ^ Partridge, Eric (2002). A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-29189-7.

- ^ Bolden, Tony (2004). Afro-Blue: Improvisations in African American Poetry and Culture. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02874-8.

- ^ Ferris, p. 230.

- ^ Handy, W.C. Father of the Blues: An Autobiography. Ed. Arna Bontemps. New York: Macmillan, 1941. p. 143.

- ^ Ewen, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Blesh, Rudi; Janis, Harriet Grossman (1958). They All Played Ragtime: The True Story of an American Music. Sidgwick & Jackson. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-4437-3152-2.

- ^ Thomas, James G. Jr. (2007). The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Ethnicity. University of North Carolina Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-8078-5823-3.

- ^ Komara, p. 476.

- ^ From Big Joe Turner’s «Rebecca», a compilation of traditional blues lyrics

- ^ Moore, Allan F. (2002). The Cambridge Companion to Blues and Gospel Music. Cambridge University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-521-00107-6.

- ^ «Photographic image of record label» (JPG). Wirz.de. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ Oliver, p. 281.

- ^ a b Morales, p. 277.

- ^ a b c Humphrey, Mark A. In Nothing but the Blues. pp. 107–149.

- ^ Calt, Stephen; Perls, Nick; Stewart, Michael. Ten Years of Black Country Religion 1926–1936 (LP back cover notes). New York: Yazoo Records. L-1022. Archived from the original on October 2, 2008.

- ^ «Reverend Gary Davis». 2009. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ Corcoran, Michael. «The Soul of Blind Willie Johnson». Austin American-Statesman. Archived from the original on October 30, 2005. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ Brozman, Bob (2002). «The Evolution of the 12-Bar Blues Progression». Archived from the original on May 25, 2010. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ Charters, Samuel. In Nothing but the Blues. p. 20.

- ^ Fullman, Ellen. «The Long String Instrument» (PDF). MusicWorks. Issue 37, Fall 1987. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 25, 2008.

- ^ «A Jazz Improvisation Almanac, Outside Shore Music Online School». Archived from the original on September 11, 2012.

- ^ Ewen, p. 143.

- ^ Kunzler, p. 1065.

- ^ Pearson, Barry. In Nothing but the Blues. p. 316.

- ^ Hamburger, David (2001). Acoustic Guitar Slide Basics. ISBN 978-1-890490-38-6.

- ^ Evans, David. In Nothing but the Blues. p. 33.

- ^ a b Kunzler, p. 130.

- ^ Bastin, Bruce. In Nothing but the Blues. p. 206.

- ^ Evans, David. In Nothing but the Blues. pp. 33–35.

- ^ Cowley, John H. In Nothing but the Blues. p. 265.

- ^ Cowley, John H. In Nothing but the Blues. pp. 268–269.

- ^ «Lead Belly Foundation». Archived from the original on January 23, 2010. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ Oliphant, Dave. «Henry Thomas». The Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ Garofalo, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Oliver, p. 3.

- ^ Bohlman, Philip V. (1999). «Immigrant, Folk, and Regional Music in the Twentieth Century». The Cambridge History of American Music. David Nicholls, ed. Cambridge University Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-521-45429-2.

- ^ a b Levine, Lawrence W. (1977). Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom. Oxford University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-19-502374-9.

- ^ Southern, p. 333.

- ^ Garofalo, p. 44.

- ^ Ferris, p. 229.

- ^ Morales, p. 276. Morales attributed this claim to John Storm Roberts in Black Music of Two Worlds, beginning his discussion with a quote from Roberts: «There does not seem to be the same African quality in blues forms as there clearly is in much Caribbean music.»

- ^ «Call and Response in Blues». How to Play Blues Guitar. Archived from the original on October 10, 2008. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- ^ Charters, Samuel. In Nothing but the Blues. p. 25.

- ^ Oliver, p. 4.

- ^ «Music: Exploring Native American Influence on the Blues».

- ^ Durán, Lucy (2013). «POYI! Bamana jeli music, Mali and the blues». Journal of African Cultural Studies. 25 (2): 211–246. doi:10.1080/13696815.2013.792725. S2CID 191563534.

- ^ «Afropop Worldwide | Africa and the Blues: An Interview with Gerhard Kubik».

- ^ Vierwo, Barbara; Trudeau, Andy (2005). The Curious Listener’s Guide to the Blues. Stone Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-399-53072-2.

- ^ Scott (2003). From the Erotic to the Demonic: On Critical Musicology. Oxford University Press. p. 182.

A blues idiom is hinted at in «A Negro Love-Song», a pentatonic melody with blue third and seventh in Coleridge-Taylor’s African Suite of 1898, before the first blues publications.

- ^ Steper, Bill (1999). «African-American Music from the Mississippi Hill Country: «They Say Drums Was a-Calling»«. APF Reporter. Archived from the original on September 6, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ^ Chambers, Douglas B. (2009). Murder at Montpelier: Igbo Africans in Virginia. University Press of Mississippi. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-60473-246-7.

- ^ Charters, Samuel. In Nothing but the Blues. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Charters, Samuel. In Nothing but the Blues. p. 16.

- ^ Garofalo, p. 44. «Gradually, instrumental and harmonic accompaniment were added, reflecting increasing cross-cultural contact.» Garofalo cited other authors who also mention the «Ethiopian airs» and «Negro spirituals».

- ^ Schuller, cited in Garofalo, p. 27.

- ^ Garofalo, pp. 44–47: «As marketing categories, designations like race and hillbilly intentionally separated artists along racial lines and conveyed the impression that their music came from mutually exclusive sources. Nothing could have been further from the truth… In cultural terms, blues and country were more equal than they were separate.» Garofalo claimed that «artists were sometimes listed in the wrong racial category in record company catalogues.»

- ^ Wolfe, Charles. In Nothing but the Blues. pp. 233–263.

- ^ Golding, Barrett. «The Rise of the Country Blues». NPR. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- ^ Humphrey, Mark A. In Nothing but the Blues. p. 110.

- ^ Garofalo, p. 27. Garofalo cited Barlow in «Handy’s sudden success demonstrated [the] commercial potential of [the blues], which in turn made the genre attractive to the Tin Pan Alley hacks, who wasted little time in turning out a deluge of imitations.» (Parentheticals in Garofalo.)

- ^ a b Garofalo, p. 27.

- ^ Lynskey, Dorian (February 16, 2021). «The forgotten story of America’s first black superstars». Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ «Kentuckiana Blues Society». Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ a b Clarke, p. 138.

- ^ Clarke, p. 141.

- ^ Clarke, p. 139.

- ^ Calt, Stephen; Perls, Nick; Stewart, Michael. The Georgia Blues 1927–1933 (LP back cover notes). New York: Yazoo Records. L-1012.

- ^ Kent, Don (1968). 10 Years In Memphis 1927–1937 (vinyl back cover). New York: Yazoo Records. L-1002.

- ^ Calt, Stephen; Perls, Nick; Stewart, Michael (1970). Memphis Jamboree 1927–1936 (vinyl back cover). New York: Yazoo Records. L-1021.

- ^ a b Garofalo, p. 47.

- ^ Hawkeye Herman. «Blues Foundation homepage». Blues Foundation. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- ^ Clarke, p. 137.

- ^ Stewart-Baxter, Derrick (1970). Ma Rainey and the Classic Blues Singers. New York: Stein & Day. p. 16.

- ^ Steinberg, Jesse R.; Fairweather, Abrol (eds.) (2011). Blues: Thinking Deep About Feeling Low. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. p. 159.

- ^ Harrison, Daphne Duval (1988). Black Pearls: Blues Queens of the ’20s. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. 8.

- ^ Oliver, Paul. Boogie Woogie Trio (vinyl back cover). Copenhagen: Storyville. SLP 184.

- ^ Garofalo, p. 76.

- ^ Komara, p. 120.

- ^ Humphrey, Mark A. In Nothing but the Blues. pp. 175–177.

- ^ Pearson, Barry. In Nothing but the Blues. pp. 313–314.

- ^ Komara, p. 118.

- ^ Humphrey, Mark. A. In Nothing but the Blues. p. 179.

- ^ a b Herzhaft, p. 53.

- ^ Pierson, Leroy (1976). Detroit Ghetto Blues 1948 to 1954 (LP back cover notes). St. Louis: Nighthawk Records. 104.

- ^ Humphrey, Mark A. In Nothing but the Blues. p. 180.

- ^ Howlin’ Wolf & Jimmy Reed interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1969)

- ^ Humphrey, Mark A. In Nothing but the Blues. p. 187.

- ^ Pearson, Barry. In Nothing but the Blues. p. 342.

- ^ Herzhaft, p. 11.

- ^ Herzhaft, p. 236.

- ^ Herzhaft, p. 35.

- ^ Palmer (1981), pp. 257–259.

- ^ Komara, p. 49.

- ^ «Blues». Encyclopedia of Chicago. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ Bailey, C. Michael (October 4, 2003). «West Side Chicago Blues». All About Jazz. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ Bjorn, Lars (2001). Before Motown. University of Michigan Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-472-06765-7.

- ^ Herzhaft, p. 116.

- ^ Herzhaft, p. 188.

- ^ a b «Hill Country Blues». Msbluestrail.org. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ O’Neal, Jim. In Nothing but the Blues. pp. 347–387.

- ^ Komara, Edward M. (2006). Encyclopedia of the Blues. Routledge. p. 385.

- ^ a b Komara, p. 122.

- ^ Komara, p. 388.

- ^ O’Neal, Jim. In Nothing but the Blues. p. 380.

- ^ Aynsley Dunbar Retaliation Retrieved 9 November 2022

- ^ Stan Webb’s Chickenshack Beginnings Stanwebb.co.uk. Retrieved 4 November 2022

- ^ Garofalo, pp. 224–225.

- ^ «Phoebe Snow San Francisco Bay Blues». AllMusic. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Komara, p. 50.

- ^ Dicaire, David (2001). More Blues Singers: Biographies of 50 Artists from the Later 20th Century. McFarland. pp. 232–248. ISBN 9780786410354.

- ^ Martin, Stephen (April 3, 2008). «Malaco Records to be honored with blues trail marker» (PDF). Mississippi Development Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008. Retrieved August 28, 2008.

- ^ Aldin, Mary Katherine. In Nothing but the Blues. p. 130.

- ^ «Blues – By Category». About.com. Archived from the original on October 13, 2006. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- ^ «Blues Venues». About.com. Archived from the original on December 21, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- ^ «Blues Music Awards information». Archived from the original on April 29, 2006. Retrieved November 25, 2005.

- ^ «Blues Record Labels». About.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved October 15, 2010./

- ^ Jennifer Nicole (August 15, 2005). «The Blues: The Revolution of Music». Archived from the original on September 6, 2008. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (June 15, 1972). «A Power Plant». Newsday. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ Phil Petrie. «History of gospel music». Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ Comentale, Edward (2013). Sweet Air. Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-252-07892-7.

- ^ a b «The Influence of the Blues on Jazz» (PDF). Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- ^ Peter van der Merwe (2004). Roots of the Classical: The Popular Origins of Western Music. Oxford University Press. p. 461. ISBN 978-0-19-816647-4.

- ^ «The Blues Influence On Rock & Roll». Archived from the original on April 4, 2007. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- ^ «History of Rock and Roll». Zip-Country Homepage. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ^ «Country music». Columbia College Chicago. 2007–2008. Archived from the original on June 2, 2008. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ^ Curiel, Jonathan (August 15, 2004). «Muslim roots of the blues / The music of famous American blues singers reaches back through the South to the culture of West Africa». SFGATE. Archived from the original on September 5, 2005. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ Sounder IMDb. Retrieved February 11, 2007. Archived May 30, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «The Blues» (2003) (mini) at IMDb

- ^ «Red, White and Blues». PBS.org. Archived from the original on July 24, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

Bibliography[edit]

- Barlow, William (1993). «Cashing In: 1900-1939». In Dates, Jannette L.; Barlow, William (eds.). Split Image: African Americans in the Mass Media (2nd ed.). Howard University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-88258-178-1.

- Bransford, Steve (2004). «Blues in the Lower Chattahoochee Valley» Southern Spaces.

- Clarke, Donald (1995). The Rise and Fall of Popular Music. St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-0-312-11573-9.

- Lawrence Cohn, ed. (1993). Nothing but the Blues: The Music and the Musicians. Abbeville Publishing Group (Abbeville Press, Inc.). ISBN 978-1-55859-271-1.

- Dicaire, David (1999). Blues Singers: Biographies of 50 Legendary Artists of the Early 20th Century. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0606-7.

- Ewen, David (1957). Panorama of American Popular Music. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-648360-1.

- Ferris, Jean (1993). America’s Musical Landscape. Brown & Benchmark. ISBN 978-0-697-12516-3.

- Garofalo, Reebee (1997). Rockin’ Out: Popular Music in the USA. Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-13703-9.

- Herzhaft, Gérard; Harris, Paul; Debord, Brigitte (1997). Encyclopedia of the Blues. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 978-1-55728-452-5.

- Komara, Edward M. (2006). Encyclopedia of the Blues. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92699-7.

- Kunzler, Martin (1988). Jazz Lexikon (in German). Rohwolt Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN 978-3-499-16316-6.

- Morales, Ed (2003). The Latin Beat. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81018-3.

- Oliver, Paul; Wright, Richard (1990). Blues Fell This Morning: Meaning in the Blues. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37793-5.

- Palmer, Robert (1981). Deep Blues. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-49511-5.

- Schuller, Gunther (1968). Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504043-2.

- Southern, Eileen (1997). The Music of Black Americans. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-03843-9.

- Curiel, Jonathan (August 15, 2004). «Muslim Roots of the Blues». SFGate. Archived from the original on September 5, 2005. Retrieved August 24, 2005.

Further reading[edit]

- Abbott, Lynn and Doug Seroff. The Original Blues: The Emergence of the Blues in African-American Vaudeville, 1889–1926. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2019.

- Brown, Luther. «Inside Poor Monkey’s», Southern Spaces, June 22, 2006.

- Dixon, Robert M.W.; Godrich, John (1970). Recording the Blues. London: Studio Vista. 85 pp. SBN 289-79829-9.

- Oakley, Giles (1976). The Devil’s Music: A History of the Blues. London: BBC. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-563-16012-0.

- Keil, Charles (1991) [1966]. Urban Blues. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-42960-1.

- Oliver, Paul (1998). The Story of the Blues (new ed.). Northeastern University Press. ISBN 978-1-55553-355-7.

- Oliver, Paul (1965). Conversation with the Blues, Volume 1. New York: Horizon Press. ISBN 978-0-8180-1223-5.

- Rowe, Mike (1973). Chicago Breakdown. Eddison Press. ISBN 978-0-85649-015-6.

- Titon, Jeff Todd (1994). Early Downhome Blues: A Musical and Cultural Analysis (2nd ed.). University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4482-3.

- Welding, Peter; Brown, Toby, eds. (1991). Bluesland: Portraits of Twelve Major American Blues Masters. New York: Penguin Group. 253 + [2] pp. ISBN 0-525-93375-1.

External links[edit]

- Blues at Curlie

- The American Folklife Center’s Online Collections and Presentations

- The Blue Shoe Project – Nationwide (U.S.) Blues Education Programming

- «The Blues», documentary series by Martin Scorsese, aired on PBS

- The Blues Foundation

- The Delta Blues Museum (archived 12 June 1998)

- The Music in Poetry – Smithsonian Institution lesson plan on the blues, for teachers

- American Music: Archive of artist and record label discographies

MEANING

The blues is a melancholic music of black American folk origin, usually employing a basic 12-bar chorus, the tonic, subdominant, and dominant chords, frequent minor intervals, and blue notes.

It originated in the southern United States towards the end of the 19th century, developing from African American folk songs such as the work songs chanted on plantations, spirituals and hollers. In the 1940s, as African Americans migrated to cities in large numbers, the blues found a wider audience and gave rise to rhythm and blues and rock and roll.

ORIGIN

The adjective blue has long been used to signify, of a person, the heart, a feeling, etc., depressed, sorrowful, miserable. It was originally a metaphorical use of blue meaning, of the skin, bruised, as in the expression black and blue, discoloured by bruises. This is explicit in the first known instance of this usage, which is found in Merlin, a Middle-English metrical version of the French romance Estoire de Merlin, completed in the first half of the 15th century by Henry Lovelich, a London skinner; this romance tells that after Arthur’s time a great plague gave rise to the name of “Bloye breteyne” (= “Blue Britain”) because the British people’s “hertes bothe blw and blak they were” (= “hearts both blue and black they were”) with sorrow.

The English poet Geoffrey Chaucer (circa 1342-1400) used the metaphor in The compleynt of Mars (circa 1385):

Ye lovers, that lye in any drede,

Fleeth, lest wikked tonges yow espye.

Lo, yond the sunne, the candel of jelosye!

Wyth teres blewe and with a wounded herte

Taketh your leve.

in contemporary English:

You lovers that are in fear, flee, lest wicked tongues discover you. Behold the sun yonder, the candle of jealousy! With blue tears and with wounded heart, take your leave.

The adjective blue is also used to signify, of a period, event, circumstance, etc., depressing, dismal. In The Short French Dictionary (3rd edition – London, 1690), the Swiss-born lexicographer Guy Miège (1644-circa 1718) wrote:

’Twill be a blue day for him, ce Jour là lui sera fatal [= that day will be fatal to him].

Blue is also taken as the colour of the plague and other harmful things. The English playwright, poet and critic John Dryden (1631-1700) wrote the following in All for love; or, The world well lost (London, 1678):

Now, my best Lord, in Honor’s name, I ask you,

For Manhood’s sake, and for your own dear safety,

Touch not these poison’d Gifts,

Infected by the Sender, touch ’em not,

Miriads of bluest Plagues lye underneath ’em.

These uses of blue and the belief that mental depression was caused by demonic possession gave rise to the term (the) blue devil(s), meaning, literally, malignant demon(s) causing despondency, and, metaphorically, despondency itself. The author of A Dissertation upon Laughter, published in The Grand Magazine of Magazines; or, A Public Register of Literature and Amusement (London) of September 1750, wrote, probably jocularly, of these demons:

[Laughter] is a most healthful exercise, gives briskness to the blood’s motion, makes a proper and lively distribution of the animal spirits, and is a more powerful exorcism of those blue devils, which too often possess our poor mortal fabric, than what can be performed by a conclave of cardinals.