Hello, how are you?

A man slowly cracks his eyes open and yawns, sitting up in bed.

A mare groans as she gets out of bed.

Opening a window, a man’s head popped out.

Opening a window, a mare’s head popped out.

Both sigh, before saying, «Morning!»

Bright, sunny daylight lies outside.

A man stands in a kitchen, yawns as he makes his breakfast.

A mare sits patiently at a table, yawning.

They sing, «La la la la da la~,» in their hearts.

A yellow woman cheers as she eats her breakfast, a man smiling and doing the same across the table from her.

A mare looks over a scroll as she eats some toast.

A mare sleeps soundly in her dark room, happily dreaming.

«Hello, how are you?»

An unassuming neighborhood sprawled out before the dark sky. The sun was not yet risen, and all in the small town that housed this neighborhood was bathed in the light of street lamps and little else. This neighborhood, this block, was not overly grandiose. For all intents and purposes, it was just as average as any small town neighborhood found in the modern world of 2018. But in this neighborhood was a particular boy.

He was young, 19 years old in fact, and a fairly plain boy. Some may call him cute, others unattractive; he tried not to let appearance bother him, though. His hair was thick yet short, barely close to touching his eyes, and dyed a light, silvery blue with gold fringes. His other features were what pegged him as plain, however. He bore glasses, and a clean shaven face. His eyes, sparking with contemplation, were a hazel green.

He wore a light gray hoodie with a design of a particularly well-known wolf known as Sif on the back, blue skinny jeans so worn at the bottom that the tail-end of the legs were torn, but only at the very endges, just above his black, steel-toed hiking boots, with a belt coupled with a buckle on it with the symbol of the Inquisition from Dragon Age.

This young man was, very clearly, a gamer. And he was currently walking the streets of this neighborhood, as he had done for the past 4 years of his life. He had an unreadable expression on his face, but it was clear in his eyes that his mind was elsewhere.

It seems pretty quiet tonight, er, today. He thought himself, tilting his head up to look at the smoky black expanse of sky. …I wonder how much longer it is ’till the sun rises. He frowned lightly. Can’t really see the horizon that well with those huge ass trees covering the western horizon. His mouth returned to a normal, flat line as he shrugged to himself and kept walking. Well, I’ll just have to wait ’till later to see the glorious sun, I guess.

His thoughts jumped from one to the next, ranging from whether he would eat later in the morning to what game or video he’d watch or play in the afternoon. And then, he noticed a person, particularly a well-dressed, black haired and pony tailed woman, right on the corner of the street. The boy hummed in thought. Bit weird. It’s not that often I see people out and about this early. Much less so well dressed. He squinted his eyes. Huh. Is she a cosplayer or something? Those are pretty rare around this town.

Curious, he walked towards her. She seemed to be watching the sky above, as if waiting for something. When he drew close enough, she looked to him and smiled, her masquerade mask hiding most of her posh looking pale face.

«Hello, my boy. How are you this fine, crisp morning?» she asked genially, smiling. The boy smiled back.

«Good, good, just out for a walk. It’s kinda my thing,» he answered, coming to a stop in front of her, stuffing his hands into his pockets. «Can I ask what you’re doing out here so early?»

Her smile widened. «Well, I happen to have a spare pencil someone gave me during my journalism debut at a convention, but I didn’t want to just toss it away, because it looked fairly expensive. So I’ve been wandering around, hoping someone will take it off my hands so I can finally get some rest.»

The boy raised a brow. «Huh. Can I see it? Ya got me curious now.»

«Certainly,» she dug into her fine, red Victorian coat pocket and pulled out a stylish pencil. «Here you are!» The young man took it, looking it over with a fair degree of interest and awe. It was a black and yellow pencil, but with what seemed to be Anglo-Saxon runes carved in gold script into each side. It was sharpened to a fine point, the eraser looked unused and untarnished, and overall it seemed almost…otherworldly. «I take it you like it?» The boy looked up at her, realizing he’d been staring at it for a mite too long.

«Oh, uh, yeah, it looks pretty frickin’ awesome,» he said with a nod. The woman’s cherry red lips curled into a large smile.

«Well, would you like to have it, then?» She asked. «In return, you can give me a hug.»

The youth gave her a quizzical look. «A hug?» She nodded. «That’s kinda…unusual, to ask.»

She giggled daintily behind a hand. «Well, us ladies like to be hugged from time to time, especially from strapping young men like you!»

The boy blushed, but eventually calmed down and shrugged. «Eh, alright then.» Thus, he took a step toward her and wrapped his arms around her in a brief hug. She giggled again and returned the gesture, and then they released each other.

«Well, that concludes our deal, my boy,» she said, smile turning mischievous. She gave him a two fingered salute as he raised a brow, before he was hit with a wave of drowsiness, and all he managed to say was a mumbled, «Wha-?» before he collapsed to the pavement. The woman giggled once more, twirling a cane that appeared in her hand out of nowhere. «Another successful trade!»

The youth felt as if he were in a dream, for all was black. All he heard were whispers and mutters and murmurs. Never was he able to make out a word or string together a sentence. It was just as if he were walking through a crowd as a criminal, but he didn’t recall ever committing any crimes.

He grew worried after what seemed ten minutes.

Afraid after twenty.

Then, just as he was about to try and wake himself up with an old trick he had learned, the voices all stopped. Kaleidoscopes of colors flashed through his mind, so quickly and so brightly that it should have blinded him, and it only hurt more when his eyes were met with utter darkness again, and then the light returned.

Finally, he felt himself start to wake up after the light once again went to darkness.

The young man awoke blearily to the sounds of nature all around him, like he had been camping. But…wasn’t I just walking around the block? He rubbed the sleep from his eyes and they promptly widened as he noted the greenery all around him. Trees of various kinds, shrubs and bushes and flowerbeds, all of it dazzled him with the beauty of nature. He wasn’t sure how, but despite his mind telling him this had to be a dream, his heart assured him it was real.

It was only made more apparent when he felt a small leather bound notebook impact his head and bounce off to the side of his lap, followed by the same pencil he’d obtained from that woman and a piece of paper that fluttered down to his other side. He slowly grabbed the paper, and opened it up to see a letter.

Hello, my boy.

Let me be the first to welcome you to your new escape from Earth, your new home, Equestria. To clarify things so you don’t go all loopy like some other folks I’ve Displaced; yes, you are not dreaming, and yes, this is real. Deny it all you want, that won’t change.

Now, onto your new abilities as a Displaced. That little pencil I gave you earlier? It’s enchanted with strong magic. Essentially, you can write on any surface, anything at all, and whatever you write will come into being. Well, with some side-effects. For one, go with something too big, like, «I become a God,» or anything that could change your biology or spirit, and the magical backlash will very likely kill you. So try to be careful with that. Of course, there are some exceptions, but knowing your studious nature, I’m sure you’d rather figure those out for yourself. The pencil is also indestructible and will always stay sharp.

The magic of the pencil will essentially draw on your power, your will and mana pool, which will grow with repeated exercise, just like muscles. Also, it’ll only work for you, and any sentences already written, whilst they can be erased, the effects cannot be undone without a special ritual you’ll get later.

I’d recommend starting small, but hey, your life, dear boy. Anywho, have fun~!

-Trader

The boy stared at the small page for a long time. Slowly, he clenched it and placed it in his coat pocket, and picked up the pencil. He slowly tightened his grip on it as he closed his emerald green eyes and took several long, deep breaths. Then, he opened them, and got to his feet. He then looked to the sunny sky peeking out from the canopy, and spoke.

«…Well… Guess my ideas of having a bit of an adventure finally came true, huh, bro?» He let out a breathless chuckle. «…At least it’s in this world, eh?»

With that, he began to walk through the forest, towards his new life.

TOEFL Success Read the passage to review the vocabulary you have learned. Answer the questions that follow.

Johannes Gutenberg’s ingenious use of movable type in his printing press had a wide range of effects on European societies. Most obviously, readers no longer had to decipher odd handwriting, with ambiguous lettering, in order to read a written work. Gutenberg gave each letter standard forms, a move that had connotations far beyond the printing business. The inscriptions on tombstones and roadside mileposts, for example, could now be standardized. The cost of books decreased. Even illiterate people benefited indirectly from the advent of this invention, as the general level of information in society increased. However, Gutenberg’s press was of limited use for languages that used picture-like symbols for writing instead of a phonetic system. Systems of symbolic pictographs, each of which denotes a word, require many thousands of characters to be cast into lead type by the printer. Phonetic systems, like the Latin alphabet, use the same few characters, recombined in thousands of ways to make different words.

Bonus Structure — Most obviously introduces an easyto-see effect and implies that lessclear effects will come later.

-

Anthropologist are now looking closer at cave paintings as a form of communication. Von Petzinger, a PhD student at the University of Victoria who has been studying prehistoric signs in European caves for a decade, says they suggest «the first glimmers of graphic communication» before the written word. Cave paintings acted as a precursor before the development of written word, as the development of a writing system had to come from some basic idea.

-

Written word emerges in around 3100 BCE in Sumer, Mesopotamia. This system of writing was called Cuneiform and was made by drawing marks in wet clay with a reed implement. In cuneiform, a stylus is pressed into soft clay to produce wedge-like mark that represent word-signs (pictographs) and, later, phonograms or (word-concepts).

-

Early cuneiform tablets were known as proto-cuneiform. At first, cuneiform was representational. A bull might be represented by a picture of a bull, and a pictograph of barley signified the word barley. The writings became abstract as it evolved to encompass more abstract concepts, eventually creating the writing system of Cuneiform. The evolution of Cuneiform occurred in stages. In stage one it was used for commercial transactions and the transactions were represented by tokens.

-

In the next stage, pictographs were drawn into wet clay, replacing the token method. With cuneiform, writers could tell stories, relate histories, and support the rule of kings. Furthermore, cuneiform was used to communicate and formalize legal systems, most famously Hammurabi’s Code.

The expansion of cuneiform began in the 3rd millennium, when the country of Elam in southwestern Iran adopted the system of writing. -

The Elamite version of cuneiform continued into the 1st millennium BCE. It also provided the Indo-European Persians with the model for creating a new simplified quasi-alphabetic cuneiform writing for the Old Persian language.

The Hurrians in northern Mesopotamia adopted a different form of cuneiform around 2000 BCE and passed it on to the Indo-European Hittites.

In the 2nd millennium cuneiform writing became a universal medium of written communication. -

The Egyptian characters were names hieroglyphs by the Greeks in about 500 BC, because this form of writing was used for holy texts. ‘Hieros’ and ‘Glypho’ mean ‘sacred’ and ‘engrave’ in Greek. The Egyptian scribe would use a fine reed pen to write on the smooth surface of the papyrus scroll.

-

The Indus script, although not deciphered yet, is known from its thousands of seals, carved in steatite or soapstone.

Usually the center of each seal has a realistic depiction of an animal, with a short line of formal symbols. The lack of longer scripts or texts suggests that this script was probably only used for trading and accountancy purposes. -

The last of the early civilizations to develop writing is China. Chinese characters are extremely difficult when printing, typewriting or word-processing because of the complex characters. Yet they have survived.

The non-phonetic Chinese script has been a crucial binding agent in China’s vast empire. Those who are often unable to speak each other’s language, have been able to communicate fluently in writing through Chinese script. -

The Olmec, are regarded as America’s first civilization, existed from about 1500 to 400 BC. They lived in what is known as the Olmec heartland, in Mexico on the southern tip of the Gulf of Mexico.

Cascajal Block, an ancient slab of writing which is thought to be the oldest known writing system in the Western Hemisphere. This block dates to the first millennia BC. The block shows linear arrangements of certain characters that appear to be depictions of tribal objects. -

Phoenician was the first major phonemic script. Compared to Cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs, it contained only about two dozen distinct letters. This script was simple enough that everyone could learn it. Because it recorded words phonetically, it could be used in any language, unlike the writing systems that were already existent. The script was spread by the Phoenicians across the Mediterranean.

-

In Greece, vowels were added to the script, giving rise to the first true alphabet. The Greeks took letters which did not represent sounds in Greek, and changed them to represent the vowels.With both vowels and consonants as explicit symbols in a single script, this made the script a true alphabet. In the early years, there were many variations of the Greek alphabet, and many alphabets evolved from this one.

-

The Romans in their turn developed the Greek alphabet to form letters suitable for the writing of Latin. Through the Roman empire the alphabet spread through Europe, and eventually through much of the world, as a standard system of writing

-

Cuneiform and its international prestige of the 2nd millennium had been exhausted by 500 BCE.

-

The Arabic alphabet is one of the most used writing systems in the world. It can be found in large parts of Africa and Western and Central Asia, as well as in smaller communities in East Asia, Europe, and the Americas. Although Arabic scripts are most common after creation of Islam in the 7th century CE, the origin of the Arabic alphabet lies goes further back.

-

The Nabataeans, who established a kingdom in modern-day Jordan, were Arabs. They wrote with a cursive Aramaic-derived alphabet that would eventually evolve into the Arabic alphabet.

Nabataean inscriptions continue to appear until the 4th century CE, coinciding with the first inscriptions in the Arabic alphabet. -

The writing system of the Mayan developed from the less sophisticated systems of the Olmec civilization. The Mayans began their writing system during the second half of the Middle Pre Classic period. The system of writing used by the Mayan people until the end of the 17th century, 200 years after the Spanish conquest of Mexico.

-

Ulfilas’ outstanding contribution to writing is his invention of the Gothic alphabet, which he created from Greek and Latin. Ulfilas invented the Gothic alphabet, a writing system, in the 4th century AD. The Gothic alphabet had 27 letters. The Gothic alphabet is similar to Greek and Latin, but there are differences in phonetic values and in the order of the letters.

-

In 700 BC the pressure of business caused the Egyptian scribes to develop a more abbreviated version of the hieratic script. Parts were still the same Egyptian hieroglyphs, established more than 2000 years before, but they are now so elided that the result looks like an entirely new script. Known as demotic (‘for the people’), it is harder to read than the earlier written versions of hieroglyphics.

Both hieroglyphics and demotic continue to be used until about 400 AD.

-

Manuscripts gained popularity in Italy in the 7th to 8th century. People began using them to create a neat and formal look with all capital letters. To emphasize the beginning of an important passage, first letter was written much larger than the rest of the text and in a grander style. The following letters were in smaller ordinary text. This distinction between capital and under case letters, is the same one we use today.

-

Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press in the 15th century. This invention furthered the ability to mass produce books and the rapid spread of knowledge throughout Europe.

Gutenberg’s invention was inspired by the Chinese monks who set ink into paper using a method known as block printing. Block printing is the process in which wooden blocks are coated with ink and pressed to sheets of paper. -

Charles Fenerty invented paper from wood pulp as early around 1841. He was concerned about the difficulty a local paper mill was having in obtaining an adequate supply of rags to make quality paper, so he created his own.

-

Today many teens communicate through emojis. Experts say emojis can help some teenagers express themselves. Nearly 40 percent of Millennials, or people between 18 and 34, say emojis and GIFs are a much better way to communicate their thoughts and feelings than words.

Writing is the physical manifestation of a spoken language. It is thought that human beings developed language c. 35,000 BCE as evidenced by cave paintings from the period of the Cro-Magnon Man (c. 50,000-30,000 BCE) which appear to express concepts concerning daily life. These images suggest a language because, in some instances, they seem to tell a story (say, of a hunting expedition in which specific events occurred) rather than being simply pictures of animals and people.

Written language, however, does not emerge until its invention in Sumer, southern Mesopotamia, c. 3500 -3000 BCE. This early writing was called cuneiform and consisted of making specific marks in wet clay with a reed implement. The writing system of the Egyptians was already in use before the rise of the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 BCE) and is thought to have developed from Mesopotamian cuneiform (though this theory is disputed) and came to be known as heiroglyphics.

The phoenetic writing systems of the Greeks («phoenetic» from the Greek phonein — «to speak clearly»), and later the Romans, came from Phoenicia. The Phoenician writing system, though quite different from that of Mesopotamia, still owes its development to the Sumerians and their advances in the written word. Independently of the Near East or Europe, writing was developed in Mesoamerica by the Maya c. 250 CE with some evidence suggesting a date as early as 500 BCE and, also independently, by the Chinese.

YouTube

Follow us on YouTube!

Writing & History

Writing in China developed from divination rites using oracle bones c. 1200 BCE and appears to also have arisen independently as there is no evidence of cultural transference at this time between China and Mesopotamia. The ancient Chinese practice of divination involved etching marks on bones or shells which were then heated until they cracked. The cracks would then be interpreted by a Diviner. If that Diviner had etched `Next Tuesday it will rain’ and `Next Tuesday it will not rain’ the pattern of the cracks on the bone or shell would tell him which would be the case. In time, these etchings evolved into the Chinese script.

History is impossible without the written word as one would lack context in which to interpret physical evidence from the ancient past. Writing records the lives of a people and so is the first necessary step in the written history of a culture or civilization. A prime example of this problem is the difficulty scholars of the late 19th/early 20th centuries CE had in understanding the Maya Civilization, in that they could not read the glyphs of the Maya and so wrongly interpreted much of the physical evidence they excavated. The early explorers of the Maya sites, such as Stephens and Catherwood, believed they had found evidence of an ancient Egyptian civilization in Central America.

This same problem is evident in understanding the ancient Kingdom of Meroe (in modern day Sudan), whose Meroitic Script is yet to be deciphered as well as the so-called Linear A script of the ancient Minoan culture of Crete which also has yet to be understood.

Love History?

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

The Sumerians first invented writing as a means of long-distance communication which was necessitated by trade.

The Invention of Writing

The Sumerians first invented writing as a means of long-distance communication which was necessitated by trade. With the rise of the cities in Mesopotamia, and the need for resources which were lacking in the region, long-distance trade developed and, with it, the need to be able to communicate across the expanses between cities or regions.

The earliest form of writing was pictographs – symbols which represented objects – and served to aid in remembering such things as which parcels of grain had gone to which destination or how many sheep were needed for events like sacrifices in the temples. These pictographs were impressed onto wet clay which was then dried, and these became official records of commerce. As beer was a very popular beverage in ancient Mesopotamia, many of the earliest records extant have to do with the sale of beer. With pictographs, one could tell how many jars or vats of beer were involved in a transaction but not necessarily what that transaction meant. As the historian Kriwaczek notes,

All that had been devised thus far was a technique for noting down things, items and objects, not a writing system. A record of `Two Sheep Temple God Inanna’ tells us nothing about whether the sheep are being delivered to, or received from, the temple, whether they are carcasses, beasts on the hoof, or anything else about them. (63)

In order to express concepts more complex than financial transactions or lists of items, a more elaborate writing system was required, and this was developed in the Sumerian city of Uruk c. 3200 BCE. Pictograms, though still in use, gave way to phonograms – symbols which represented sounds – and those sounds were the spoken language of the people of Sumer. With phonograms, one could more easily convey precise meaning and so, in the example of the two sheep and the temple of Inanna, one could now make clear whether the sheep were going to or coming from the temple, whether they were living or dead, and what role they played in the life of the temple. Previously, one had only static images in pictographs showing objects like sheep and temples. With the development of phonograms one had a dynamic means of conveying motion to or from a location.

Further, whereas in earlier writing (known as proto-cuneiform) one was restricted to lists of things, a writer could now indicate what the significance of those things might be. The scholar Ira Spar writes:

This new way of interpreting signs is called the rebus principle. Only a few examples of its use exist in the earliest stages of cuneiform from between 3200 and 3000 B.C. The consistent use of this type of phonetic writing only becomes apparent after 2600 B.C. It constitutes the beginning of a true writing system characterized by a complex combination of word-signs and phonograms—signs for vowels and syllables—that allowed the scribe to express ideas. By the middle of the Third Millennium B.C., cuneiform primarily written on clay tablets was used for a vast array of economic, religious, political, literary, and scholarly documents.

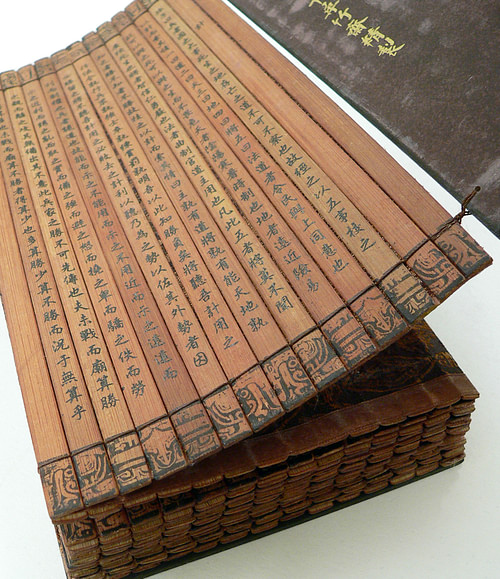

The Art of War by Sun-Tzu Coelacan (CC BY-SA)

Writing & Literature

This new means of communication allowed scribes to record the events of their times as well as their religious beliefs and, in time, to create an art form which was not possible before the written word: literature. The first writer in history known by name is the Mesopotamian priestess Enheduanna (2285-2250 BCE), daughter of Sargon of Akkad, who wrote her hymns to the goddess Inanna and signed them with her name and seal.

The so-called Matter of Aratta, four poems dealing with King Enmerkar of Uruk and his son Lugalbanda, were probably composed between 2112-2004 BCE (though only written down between 2017-1763 BCE). In the first of them, Enmerkar and The Lord of Aratta, it is explained that writing developed because the messenger of King Enmerkar, going back and forth between him and the King of the city of Aratta, eventually had too much to remember and so Enmerkar had the idea to write his messages down; and so writing was born.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, considered the first epic tale in the world and among the oldest extant literature, was composed at some point earlier than c. 2150 BCE when it was written down and deals with the great king of Uruk (and descendent of Enmerkar and Lugalbanda) Gilgamesh and his quest for the meaning of life. The myths of the people of Mesopotamia, the stories of their gods and heroes, their history, their methods of building, of burying their dead, of celebrating feast days, were now all able to be recorded for posterity. Writing made history possible because now events could be recorded and later read by any literate individual instead of relying on a community’s storyteller to remember and recite past events. Scholar Samuel Noah Kramer comments:

[The Sumerians] originated a system of writing on clay which was borrowed and used all over the Near East for some two thousand years. Almost all that we know of the early history of western Asia comes from the thousands of clay documents inscribed in the cuneiform script developed by the Sumerians and excavated by archaeologists. (4)

So important was writing to the Mesopotamians that, under the Assyrian King Ashurbanipal (r. 685-627 BCE) over 30,000 clay tablet books were collected in the library of his capital at Nineveh. Ashurbanipal was hoping to preserve the heritage, culture, and history of the region and understood clearly the importance of the written word in achieving this end. Among the many books in his library, Ashurbanipal included works of literature, such as the tale of Gilgamesh or the story of Etana, because he realized that literature articulates not just the story of a certain people, but of all people. The historian Durant writes:

Literature is at first words rather than letters, despite its name; it arises as clerical chants or magic charms, recited usually by the priests, and transmitted orally from memory to memory. Carmina, as the Romans named poetry, meant both verses and charms; ode, among the Greeks, meant originally a magic spell; so did the English rune and lay, and the German Lied. Rhythm and meter, suggested, perhaps, by the rhythms of nature and bodily life, were apparently developed by magicians or shamans to preserve, transmit, and enhance the magic incantations of their verse. Out of these sacerdotal origins, the poet, the orator, and the historian were differentiated and secularized: the orator as the official lauder of the king or solicitor of the deity; the historian as the recorder of the royal deeds; the poet as the singer of originally sacred chants, the formulator and preserver of heroic legends, and the musician who put his tales to music for the instruction of populace and kings.

Book of the Dead Papyrus Mark Cartwright (CC BY-NC-SA)

The Alphabet

The role of the poet in preserving heroic legends would become an important one in cultures throughout the ancient world. The Mesopotamian scribe Shin-Legi-Unninni (wrote 1300-1000 BCE) would help preserve and transmit The Epic of Gilgamesh. Homer (c. 800 BCE) would do the same for the Greeks and Virgil (70-19 BCE) for the Romans. The Indian epic Mahabharata (written down c. 400 BCE) preserves the oral legends of that region in the same way the tales and legends of Scotland and Ireland do. All of these works, and those which came after them, were only made possible through the advent of writing.

The early cuneiform writers established a system which would completely change the nature of the world in which they lived. The past, and the stories of the people, could now be preserved through writing. The Phoenicians’ contribution of the alphabet made writing easier and more accessible to other cultures, but the basic system of putting symbols down on paper to represent words and concepts began much earlier. Durant notes:

The Phoenicians did not create the alphabet, they marketed it; taking it apparently from Egypt and Crete, they imported it piecemeal to Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos, and exported it to every city on the Mediterranean; they were the middlemen, not the producers, of the alphabet. By the time of Homer the Greeks were taking over this Phoenician – or the allied Aramaic – alphabet, and were calling it by the Semitic names of the first two letters, Alpha, Beta; Hebrew Aleph, Beth.

Early writing systems, imported to other cultures, evolved into the written language of those cultures so that the Greek and Latin would serve as the basis for European script in the same way that the Semitic Aramaic script would provide the basis for Hebrew, Arabic, and possibly Sanskrit. The materials of writers have evolved as well, from the cut reeds with which early Mesopotamian scribes marked the clay tablets of cuneiform to the reed pens and papyrus of the Egyptians, the parchment of the scrolls of the Greeks and Romans, the calligraphy of the Chinese, on through the ages to the present day of computerized composition and the use of processed paper.

In whatever age, since its inception, writing has served to communicate the thoughts and feelings of the individual and of that person’s culture, their collective history, and their experiences with the human condition, and to preserve those experiences for future generations.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

When do you capitalize a word?

The capitalization of a word (meaning its first letter is in the upper case) often depends upon its context and placement within a sentence. While there are some words that are always capitalized no matter where they appear in a sentence—such as “proper” nouns and adjectives, as well as the first-person pronoun I—most words are only capitalized if they appear at the beginning of a sentence.

Determining when to capitalize words in the titles of creative or published works (such as novels, films, essays, plays, paintings, news headlines, etc.) can be very difficult because there is no single, generally accepted rule to follow. However, there are some standard conventions, which we’ll discuss a little further on.

Capitalizing the first word of a sentence

The first word of a sentence is always capitalized. This helps the reader clearly recognize that the sentence has begun, and we make it clear that the sentence has ended by using terminal punctuation marks (e.g., periods, exclamation points, or question marks).

We also capitalize the first letter of a sentence that is directly quoted within another sentence. This is known as direct speech. For example:

- John said, “You’ll never work in this city again!”

- Mary told him, “We should spend some time apart,” which took him by surprise.

- The other day, my daughter asked, “Why do I have to go to school, but you don’t?”

Sometimes, a portion of a larger statement will be quoted as a complete sentence on its own; this is especially common in journalistic writing. To preserve capitalization conventions, we still usually capitalize the first letter of the quoted speech (if it functions as a complete independent sentence), but we surround the capital letter in brackets to make it clear that the change was made by the person using the quotation. For instance:

- The president went on to say, “[W]e must be willing to help those less fortunate than ourselves.”

Note that we do not capitalize the first word in the quotation if it is a word, phrase, or sentence fragment incorporated into the natural flow of the overall sentence; we also do not set it apart with commas:

- My brother said he feels “really bad” about what happened.

- But I don’t want to just “see how things go”!

Trademarks beginning with a lowercase letter

Sometimes, a trademark or brand name will begin with a lowercase letter immediately followed by an uppercase letter, as in iPhone, eBay, eHarmony, etc. If writers decide to begin a sentence with such a trademarked word, they may be confused about whether to capitalize the first letter since it is at the beginning of a sentence, or to leave the first letter in lowercase since it is specific to the brand name. Different style guides have different requirements, but most guides recommend rewording the sentence to avoid the issue altogether:

- «iPhone sales continue to climb.» (not technically wrong, but not ideal)

- “Sales for the iPhone continue to climb.” (correct and recommended)

Proper Nouns

Proper nouns are used to identify a unique person, place, or thing (as opposed to common nouns, which identify generic or nonspecific people or things). A proper noun names someone or something that is one of a kind; this is signified by capitalizing the first letter of the word, no matter where it appears in a sentence.

The most common proper nouns are names of people, places, or events:

- “Go find Jeff and tell him that dinner is ready.”

- “I lived in Cincinnati before I moved to New York.”

- “My parents still talk about how great Woodstock was in 1969.”

Proper nouns are similarly used for items that have a commercial brand name. In this case, the object that’s being referred to is not unique in itself, but the brand it belongs to is. For example:

- “Pass me the Frisbee.”

- “I’ll have a Pepsi, please.”

- “My new MacBook is incredibly fast.”

The names of organizations, companies, agencies, etc., are all proper nouns as well, so the words that make up the name are all capitalized. However, unlike the nouns of people or places, these often contain function words (those that have only grammatical importance, such as articles, conjunctions, and prepositions), which are not capitalized. For example:

- “You’ll have to raise your query with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.”

- “I’ve been offered a teaching position at the University of Pennsylvania.”

- “Bay Area Rapid Transit workers continue their strike for a fifth consecutive day.”

These are often made into acronyms and initialisms, which we’ll discuss a bit later.

Appellations

Appellations are additional words added to a person’s name. These may be used to indicate respect for a person (known as honorifics) or to indicate a person’s profession, royalty, rank, etc. (known as titles). Some appellations are always abbreviated before a person’s name, such as Dr. (short for Doctor), Mr. (short for Mister), and Mrs. (originally a shortened form of Mistress), and some may be used in place of a person’s name altogether (such as Your Honor, Your Highness, or Your Majesty).

Appellations are considered a “part” of the person’s name and are also capitalized in writing as a proper noun. For example:

- “Dr. Spencer insists we perform a few more tests.”

- “I intend to ask Professor Regan about her dissertation on foreign policy.”

- “Prince William is adored by many.”

- “Please see if Mr. Parker and Mrs. Wright will be joining us this evening.”

- “I have no further questions, Your Honor.”

Normal words can also function as appellations after a person’s name to describe his or her appearance, personality, or other personal characteristics; these are formally known as epithets. They are usually accompanied by function words (especially the article the), which are not capitalized. For example:

- Alexander the Great

- Ivan the Terrible

- Charles the Bald

Proper Adjectives

Proper adjectives are formed from proper nouns, and they are also capitalized. They are often made from the names of cities, countries, or regions to describe where something comes from or to identify a trait associated with that place, but they can also be formed from the names of people. For example:

|

Proper Noun |

Proper Adjective |

Example Sentence |

|---|---|---|

|

Italy |

Italian |

I love Italian food. |

|

China |

Chinese |

How much does this Chinese robe cost? |

|

Christ |

Christian |

In Europe, you can visit many ancient Christian churches. |

|

Shakespeare |

Shakespearean |

He writes in an almost Shakespearean style. |

Sometimes, a word that began as a proper adjective can lose its “proper” significance over time, especially when formed from the name of a fictional character. In these cases, the word is no longer capitalized. Take the following sentence:

- “He was making quixotic mistakes.”

The word quixotic was originally a proper adjective derived from the name “Don Quixote,” a fictional character who was prone to foolish, grandiose behavior. Through time, it has come to mean “foolish” in its own right, losing its association to the character. As such, it is no longer capitalized in modern English.

Another example is the word gargantuan. Once associated with the name of a giant in the 16th-century book Gargantua, it has come to mean “huge” in daily use. Since losing its link with the fictional monster, it is no longer capitalized:

- “The couple built a gargantuan house.”

Other capitalization conventions

While proper nouns, proper adjectives, and the first word in a sentence are always capitalized, there are other conventions for capitalization that have less concrete rules.

Reverential capitalization

Traditionally, words for or relating to the Judeo-Christian God or to Jesus Christ are capitalized, a practice known as reverential capitalization. This is especially common in pronouns, though it can occur with other nouns associated with or used as a metaphor for God. For example:

- “Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy Name.”

- “We must always model our actions on the Lord’s will, trusting in His plan and in the benevolence of the Almighty.”

However, this practice is one of style rather than grammatical correctness. It is becoming slightly less common in modern writing, especially in relation to pronouns, and many modern publications (even some editions of the Bible) tend not to capitalize pronouns associated with God or Jesus Christ (though nouns such as “the Lamb” or “the Almighty” still tend to be in uppercase).

Finally, note that when the word god is being used to describe or discuss a deity in general (i.e., not the specific God of Christian or Jewish faith), it does not need to be capitalized. Conversely, any name of a specific religious figure must be capitalized the same way as any other proper noun, as in Zeus, Buddha, Allah, Krishna, etc.

Acronyms and Initialisms

Acronyms and initialisms are abbreviations of multiple words using just their initial letters; like the initials of a person’s name, these letters are usually capitalized. Acronyms are distinguished by the fact that they are read aloud as a single word, while initialisms are spoken aloud as individual letters rather than a single word. (However, because the two are so similar in appearance and function, it is very common to simply refer to both as acronyms.)

Acronyms

Because acronyms are said as distinct words, they are usually (but not always) written without periods. In some cases, the acronym has become so common that the letters aren’t even capitalized anymore.

For example:

- “Scientists from NASA have confirmed the spacecraft’s location on Mars.” (acronym of “National Aeronautics and Space Administration”)

- “The officer went AWOL following the attack.” (acronym of “Absent Without Leave”)

- “I need those documents finished A.S.A.P.” (acronym or initialism of “As Soon As Possible”; also often written as ASAP, asap, and a.s.a.p.)

- “His scuba equipment turned out to be faulty.” (Scuba is actually an acronym of “self-contained underwater breathing apparatus,” but it is now only written as a regular word.)

It’s worth noting that in British English, it is becoming increasingly common to write acronyms of well-known organizations with only the first letter capitalized, as in Nafta (North American Free Trade Agreement) or Unicef (United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund), while initialisms, such as UN or UK, are still written in all capital letters.

Initialisms

Like acronyms, it is most common to write initialisms without periods. However, in American English, it is also common to include periods between the letters of some initialisms. This varies between style guides, and it is generally a matter of personal preference; whether you use periods in initialisms or not, be sure to be consistent.

Here are some examples of common initialisms (some with periods, some without):

- “I grew up in the US, but I’ve lived in London since my early 20s.” (initialism of “United States”)

- “It took a long time, but I’ve finally earned my Ph.D.” (initialism of “Philosophiae Doctor,” Latin for “Doctor of Philosophy”)

- “I need to go to an ATM to get some cash.” (initialism of “Automated Teller Machine”)

- “The witness claimed to have seen a U.F.O. fly over the field last night.” (initialism of “Unidentified Flying Object”)

Notice that the h in Ph.D. remains lowercase. This is because it is part of the same word as P (Philosophiae); it is spoken aloud as an individual letter to help make the initialism distinct. While this mix of uppercase and lowercase letters in an initialism is uncommon, there are other instances in which this occurs. Sometimes, as with Ph.D., the lowercase letters come from the same word as an uppercase letter; other times, the lowercase letter represents a function word (a conjunction, preposition, or article). For example:

- AmE (American English)

- BrE (British English)

- LotR (Lord of the Rings)

- DoD (Department of Defense)

Finally, there are two initialisms that are always in lowercase: i.e. (short for the Latin id est, meaning “that is”) and e.g. (short for the Latin exempli gratia, meaning “for example”). The only instance in which these initialisms might be capitalized is if they are used at the beginning of a sentence, but doing so, while not grammatically incorrect, is generally considered aesthetically unappealing and should be avoided.

Abbreviations in conversational English

In conversational writing, especially with the advent of text messages and online messaging, many phrases have become shortened into informal abbreviations (usually initialisms, but occasionally said aloud as new words). They are usually written without periods and, due to their colloquial nature, they are often left in lowercase. While there are thousands of conversational abbreviations in use today, here are just a few of the most common:

- LOL (short for “Laugh Out Loud,” said as an initialism or sometimes as a word [/lɑl/])

- OMG (short for “Oh My God.” Interestingly, the first recorded use of this initialism was in a letter from Lord John Fisher to Winston Churchill in 1917.)

- BTW (short for “By The Way”)

- BRB (short for “Be Right Back”)

- BFF (short for “Best Friend Forever”)

- IDK (short for “I Don’t Know”)

- FWIW (short for “For What It’s Worth”)

- FYI (short for “For Your Information”)

- IMHO (short for “In My Humble/Honest Opinion”)

- P2P (short for “Peer-To-Peer,” with the word To represented by the number 2, a homophone)

- TLC (short for “Tender Loving Care”)

- TL;DR (short for “Too Long; Didn’t Read”)

- TTYL (short for “Talk To You Later”)

Because these are all very informal, they should only be used in conversational writing.

What to capitalize in a title or headline

There is much less standardization regarding how to capitalize titles or article headlines; different style guides prescribe different rules and recommendations.

That said, it is generally agreed that you should capitalize the first and last word of the title, along with any words of semantic significance—that is, nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs—along with proper nouns, proper adjectives, acronyms, and initialisms. “Function words,” those that primarily add grammatical meaning rather than anything substantial (prepositions, articles, and conjunctions), are generally left in lowercase. This convention is sometimes known as title case, and some style guides recommend following it without exception, even for longer function words like between or upon.

For example:

- “New Regulations for Schools Scoring below National Averages”

- “An Analysis of the Differences between Formatting Styles”

- “President to Consider Options after Results of FBI Investigation”

- “Outrage over Prime Minister’s Response to Corruption Charges”

Some words can pose problems because they can in some instances be prepositions and in other instances be adverbs. For example, in the phrasal verb take off, off is functioning adverbially to complete the meaning of the verb, so it would be capitalized in a title:

- “Home Businesses Taking Off in Internet Age”

- “Home Businesses Taking off in Internet Age”

Another group of words that often gives writers problems is the various forms of the verb to be, which conjugates as is, am, are, was, were, been, and being. Because many of its forms are only two or three letters, writers are often inclined not to capitalize them; however, because to be is a verb, we should always capitalize it when using title case:

- “Determining Who Is Responsible for the Outcome” (correct)

- “Determining Who is Responsible for the Outcome” (incorrect)

Capitalizing words longer than three letters

Function words are usually not capitalized in title case, but longer function words (such as the conjunctions because or should or the prepositions between or above) are often considered to add more meaning than short ones like or or and. Because of this, it is a common convention is to capitalize function words that have more than three letters in addition to “major” words like nouns and verbs. Here’s how titles following this convention look:

- “New Regulations for Schools Scoring Below National Averages”

- “An Analysis of the Differences Between Formatting Styles”

- “President to Consider Options After Results of FBI Investigation”

- “Outrage Over Prime Minister’s Response to Corruption Charges”

Some style guides specify that only function words that are longer than four letters should be capitalized. Following this convention, the first three examples would remain the same, but the word over in the fourth example would remain lowercase. However, the “longer than three letters” rule is much more common.

Capitalizing hyphenated compounds

When a compound word features a hyphen, there are multiple ways to capitalize it in a title. Because compound words always serve as nouns or adjectives (or, rarely, verbs), we always capitalize the first part of the compound. What is less straightforward is whether to capitalize the word that comes after the hyphen. Some style guides recommend capitalizing both parts (so long as the second part is a “major” word), while others recommend only capitalizing the first part. For example:

- “How to Regulate Self-Driving Cars in the Near Future”

- “Eighteenth-century Warship Discovered off the Coast of Norway”

Certain style guides are very specific about how to capitalize hyphenated compounds, so if your school or employer uses a particular guide for its in-house style, be sure to follow its requirements. Otherwise, it is simply a matter of personal preference whether hyphenated compounds should be capitalized in full or in part; as always, just be consistent.

Compounds with articles, conjunctions, and prepositions

Some multiple-word compounds are formed with function words (typically the article the, the conjunction and, or the preposition in) between two other major words. While capitalizing the major words in the compound is optional and up to the writer’s personal preference, the function words will always be in lowercase:

- “Are Brick-and-Mortar Stores Becoming Obsolete?”

- “Prices of Over-the-counter Medications Set to Rise”

- “Business Tycoon Appoints Daughter-In-Law as New CEO”

The only exception to this rule is when writers choose to capitalize every word in the title.

Start case

To eliminate the possible confusion caused by short “substance” words (e.g., forms of to be), long function words (e.g., because or beneath), and hyphenated compounds, some publications choose to simply capitalize every word in a title, regardless of the “types” of words it may contain. This is sometimes known as “start case” or “initial case.” For instance:

- “New Regulations For Schools Scoring Below National Averages”

- “An Analysis Of The Differences Between Formatting Styles”

- “President To Consider Options After Results Of FBI Investigation”

- “Outrage Over Prime Minister’s Response To Corruption Charges”

This is especially common in journalism and online publications, but it is usually not recommended for academic or professional writing.

Sentence case

“Sentence case” refers to titles in which only the first word has a capital letter, the same way a sentence is capitalized. (Again, proper nouns, proper adjectives, acronyms, and initialisms remain capitalized.) As with start case, sentence case is useful because it eliminates any possible confusion over which words should be capitalized. Titles following this convention look like this:

- “New regulations for schools scoring below national averages”

- “An analysis of the differences between formatting styles”

- “President to consider options after results of FBI investigation”

- “Outrage over Prime Minister’s response to corruption charges”

Sentence case is not typically recommended by academic or professional style guides, though this is not always true. Some magazine and news publications use the style for their headlines as well, as do many websites.

Capitalizing subtitles

When a piece of work has both a main title and a secondary subtitle (separated by a colon), we apply the same capitalization rules to both—that is, the same types of words will be in uppercase or lowercase depending on which style is being used. We also capitalize the first word after the colon, treating the subtitle as its own. For example:

- The Secret Agent: A Simple Tale

- Terminator 2: Judgment Day

- Angela’s Ashes: A Memoir

- Vanity Fair: A Novel without a Hero (sometimes written as Vanity Fair: A Novel Without a Hero due to the preference of capitalizing words longer than three letters)

This convention is also true in academic essays, whose subtitles tend to be longer and more detailed, giving the reader a brief explanation of what the essay is about:

- From the Television to the Supermarket: How the Rise of Modern Advertising Shaped Consumerism in America

- True Crimes: A Look at Criminal Cases That Inspired Five Classic Films

Note that if the main title is written in sentence case, then we only capitalize the first word of the subtitle (after the colon):

- In their shoes: Women of the 1940s who shaped public policy

However, this style is generally only used when a title appears in a list of references in an essay’s bibliography (individual style guides will have specific requirements for these works cited pages).

Alternate titles

Sometimes a subtitle acts as an alternate title; in this case, the two are often separated with a semicolon or a comma, followed by a lowercase or (though the specific style is left to the writer’s or publisher’s discretion). However, the alternate title is still capitalized the same way as the main title, with the first word after or being capitalized even if it is a short function word. For example:

- Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus

- Moby-Dick; or, The Whale

- Twelfth Night, or What You Will

- Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Capitalizing headings

Headings are titles that identify or introduce a specific section within a larger academic essay or business document. In general, headings will be capitalized in the same manner as the document’s title, usually having the first and last word capitalized as well as any nouns, adjectives, adverbs, and verbs (and, depending on the style guide being followed, any prepositions or conjunctions longer than three letters).

Sometimes a written work will have multiple subheadings of sections that belong within a larger heading. It is common for subheadings to be written in sentence case, but most style guide have specific requirements for when this can be done (for instance, if the subheading is the third or more in a series of headings), if at all.

Deciding how to capitalize a title

Ultimately, unless your school or employer follows one specific style guide, it is a matter of preference to decide how the title is formatted. No matter which style you adopt, the most important thing is to be consistent throughout your body of writing.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

Word divider |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In punctuation, a word divider is a form of glyph which separates written words. In languages which use the Latin, Cyrillic, and Arabic alphabets, as well as other scripts of Europe and West Asia, the word divider is a blank space, or whitespace. This convention is spreading, along with other aspects of European punctuation, to Asia and Africa, where words are usually written without word separation.[1][better source needed]

In computing, the word delimiter is used to refer to a character that separates two words.

In character encoding, word segmentation depends on which characters are defined as word dividers.

History[edit]

In Ancient Egyptian, determinatives may have been used as much to demarcate word boundaries as to disambiguate the semantics of words.[2] Rarely in Assyrian cuneiform, but commonly in the later cuneiform Ugaritic alphabet, a vertical stroke 𒑰 was used to separate words. In Old Persian cuneiform, a diagonally sloping wedge 𐏐 was used.[3]

As the alphabet spread throughout the ancient world, words were often run together without division, and this practice remains or remained until recently in much of South and Southeast Asia. However, not infrequently in inscriptions a vertical line, and in manuscripts a single (·), double (:), or triple (⫶) interpunct (dot) was used to divide words. This practice was found in Phoenician, Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin, and continues today with Ethiopic, though there whitespace is gaining ground.

Scriptio continua[edit]

The early alphabetic writing systems, such as the Phoenician alphabet, had only signs for consonants (although some signs for consonants could also stand for a vowel, so-called matres lectionis). Without some form of visible word dividers, parsing a text into its separate words would have been a puzzle. With the introduction of letters representing vowels in the Greek alphabet, the need for inter-word separation lessened. The earliest Greek inscriptions used interpuncts, as was common in the writing systems which preceded it, but soon the practice of scriptio continua, continuous writing in which all words ran together without separation became common.

Types[edit]

None[edit]

Alphabetic writing without inter-word separation, known as scriptio continua, was used in Ancient Egyptian. It appeared in Post-classical Latin after several centuries of the use of the interpunct.

Traditionally, scriptio continua was used for the Indic alphabets of South and Southeast Asia and hangul of Korea, but spacing is now used with hangul and increasingly with the Indic alphabets.

Today Chinese and Japanese are the most widely-used scripts consistently written without punctuation to separate words, though other scripts such as Thai and Lao also follow this writing convention. In Classical Chinese, a word and a character were almost the same thing, so that word dividers would have been superfluous. Although Modern Mandarin has numerous polysyllabic words, and each syllable is written with a distinct character, the conceptual link between character and word or at least morpheme remains strong, and no need is felt for word separation apart from what characters already provide. This link is also found in the Vietnamese language; however, in the Vietnamese alphabet, virtually all syllables are separated by spaces, whether or not they form word boundaries.

Space[edit]

Space is the most common word divider, especially in Latin script.

Traditional spacing examples from the 1911 Chicago Manual of Style[4]

Vertical lines[edit]

Ancient inscribed and cuneiform scripts such as Anatolian hieroglyphs frequently used short vertical lines to separate words, as did Linear B. In manuscripts, vertical lines were more commonly used for larger breaks, equivalent to the Latin comma and period. This was the case for Biblical Hebrew (the paseq) and continues with many Indic scripts today (the danda).

Interpunct, multiple dots, and hypodiastole[edit]

| arma·virvmqve·cano·troiae·qvi·primvs·ab·oris italiam·fato·profvgvs·laviniaqve·venit litora·mvltvm·ille·et·terris·iactatvs·et·alto vi·svpervm·saevae·memorem·ivnonis·ob·iram |

| The Latin interpunct |

The Ethiopic double interpunct

As noted above, the single and double interpunct were used in manuscripts (on paper) throughout the ancient world. For example, Ethiopic inscriptions used a vertical line, whereas manuscripts used double dots (፡) resembling a colon. The latter practice continues today, though the space is making inroads. Classical Latin used the interpunct in both paper manuscripts and stone inscriptions.[5] Ancient Greek orthography used between two and five dots as word separators, as well as the hypodiastole.

Different letter forms[edit]

In the modern Hebrew and Arabic alphabets, some letters have distinct forms at the ends and/or beginnings of words. This demarcation is used in addition to spacing.

Vertical arrangement[edit]

Nastaʿlīq used for Urdu (written right-to-left)

The Nastaʿlīq form of Islamic calligraphy uses vertical arrangement to separate words. The beginning of each word is written higher than the end of the preceding word, so that a line of text takes on a sawtooth appearance. Nastaliq spread from Persia and today is used for Persian, Uyghur, Pashto, and Urdu.

Pause[edit]

In finger spelling and in Morse code, words are separated by a pause.

Unicode[edit]

For use with computers, these marks have codepoints in Unicode:

- U+007C | VERTICAL LINE (|, |, |)

- U+00B7 · MIDDLE DOT (·, ·, ·)

- U+1361 ፡ ETHIOPIC WORDSPACE

See also[edit]

- Whitespace

- Sentence spacing

- Speech segmentation

- Zero-width non-joiner

- Zero-width space

- Substitute blank

- Underscore

References[edit]

- ^ (Saenger 2000)

- ^ «Determinatives are a most significant aid to legibility, being readily identifiable word dividers.» (Ritner 1996:77)

- ^ King, Leonard William (1901). Assyrian Cuneiform. New York: AMS Press. p. 42.

- ^ University of Chicago Press (1911). Manual of Style: A Compilation of Typographical Rules Governing the Publications of The University of Chicago, with Specimens of Types Used at the University Press (Third ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago. p. 101.

this line is spaced.

- ^ (Wingo 1972:16)

Further reading[edit]

- Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William, eds. (1996). The World’s Writing Systems. Oxford University Press.

- Knight, Stan (1996). «The Roman Alphabet». In Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (eds.). The World’s Writing Systems. Oxford University Press.

- Ritner, Robert (1996). «Egyptian Writing». In Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (eds.). The World’s Writing Systems. Oxford University Press.

- Saenger, Paul (2000). Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4016-X.

- Wingo, E. Otha (1972). Latin Punctuation in the Classical Age. Mouton. p. 16.

The greatest difference between success and failure is not the lack of ideas, but their implementation. We all think of the next-big-thing over a dozen times a day, but the ability create that ‘big thing’ is what defines us. Same is the case with writers, we have great stories and arguments rummaging through our head, but when it comes to jotting them down, you don’t know where to begin. You are stuck with thoughts like ‘where do I even begin?’, ‘how to start a paragraph?’, ’Do I even have a great idea?’

Table of Contents

- Writing Help With Sentence Starters

- Why You Need to Know about Different Words to Start a Paragraph?

- List of Suitable Words to Start an Essay

- List of Transition Words to Begin a Paragraph that Show Contrast

- Body Paragraph Starters to Add Information

- Paragraph Starter Words Showing Cause

- Words to Start a Sentence for Emphasis

- Sentence Starters for Rare Ideas

- Paragraph Starter Words for Common Ideas

- Inconclusive Topic Sentence Starters

- How to Start a Sentence that Shows Evidence

- Paragraph Starters That Focus On the Background

- Words that Present Someone Else’s Evidence or Ideas

- Words for Conclusive Paragraph Starters

- Tips for Selecting the Right Words to Start Sentences

- FAQ

Paragraph starter words provide assistance in getting that head start with your writing. Following is all the information you require regarding different ways to start a paragraph.

Writing Help With Sentence Starters

Whether you are looking for the right words to start a body paragraph in an essay or the right words to effectively conclude your ideas, there are plenty of effective ways to successfully communicate your ideas. Following are the three main types of words you can use to start your paragraph:

Begin with Adverbs

Too much of anything is nauseating, including adverbs. All those ‘ly’ words in a sentence can get pretty overwhelming pretty fast. But when effectively added to the beginning of a sentence, it can help transition, contradict or even conclude information in an impactful manner. For instance, ‘consequently’ is a great transition word, ‘conversely’ helps include a counter argument and ‘similarly’ enables you to break an idea into two paragraphs. The trick to using adverbs as sentence starters is to limit them to just one or two in a paragraph and to keep switching between them.

Synonyms for ‘However’

If only there was a penny for every time most writers use the word ‘however,’ there’d be a shortage of islands to privately own on this planet; and perhaps on a few more planets too. Anyhow, nobody’s got those pennies to spare! Might as well opt for other, equally effective substitutes! Some good options include:

- Alternatively

- Nonetheless

- Nevertheless

- Despite this

Why You Need to Know about Different Words to Start a Paragraph?

The simplest answer to this question is to mainly improve your writing. The beginning of a paragraph helps set the mood of the paragraph. It helps determine the W’s of writing (When, Why, What, Who, Where) you are trying to address. Following are some ways learning the paragraph starter words can be assistive in writing great essays:

- Sentence starters help the resist the typical format of using subject-verb structure for sentences.

- Transition words help you sound more eloquent and professional.

- They help differentiate your writing from the informal spoken language.

- They help transition your thoughts more effectively.

List of Suitable Words to Start an Essay

- The central theme

- This essay discusses

- Emphasized are

- Views on

List of Transition Words to Begin a Paragraph that Show Contrast

- Instead

- Comparatively

- However

- Otherwise

- Conversely

- Still

- On the contrary

- On the other hand

- Nevertheless

- Different from

- Besides

- Other than

- Outside of

- Whereas

Body Paragraph Starters to Add Information

- Moreover

- Furthermore

- Additionally

- Again

- Coupled with

- Correspondingly

- Similarly

- Identically

- Whereas

- Likewise

- Not only

Paragraph Starter Words Showing Cause

- Singularly

- Particularly

- Otherwise

- Unquestionably

- Generally speaking

- Consequently

- For the most part

- As a result

- Undoubtedly

- In this situation

- Otherwise

- Hence

- Ordinarily

Words to Start a Sentence for Emphasis

- Admittedly

- Certainly

- Granted

- Above all

- As a rule

- Chiefly

Sentence Starters for Rare Ideas

- Rarely

- Not many

- Uncommonly

- Seldom

- A few

Paragraph Starter Words for Common Ideas

- The majority

- More than

- Many

- Numerous

- Almost all

- Usually

- Mostly

- Several

Inconclusive Topic Sentence Starters

- There is limited evidence

- Maybe

- Perhaps

- Debatably

- For the lack of evidence

How to Start a Sentence that Shows Evidence

- The result

- Therefore

- Predictably

- The connection

- Considerably

- With regard to

- It can be seen

- Subsequently

- As a result

- The relationship

- Hence

- After examining

- The convergence

- Apparently

- Effectively

Paragraph Starters That Focus On the Background

- Customarily

- Originally

- Earlier

- In the past

- Prior to this

- Historically

- Over time

- The traditional interpretation

- Up until now

- Initially

- Conventionally

- Formerly

Words that Present Someone Else’s Evidence or Ideas

- As explained by

- According to

- With regard to

- Based on the ideas of

- As demonstrated by

- As disputed by

- As stated by

- As mentioned by

Words for Conclusive Paragraph Starters

- In conclusion

- Obviously

- Finally

- Overall

- As expressed

- Thus

- Lastly

- Therefore

- As a result

- All in all

- In essence

- By and large

- To sum up

- On balance

- Overall

- In any case

- All things considered

- In other words

Tips for Selecting the Right Words to Start Sentences

Evidently, there are hundreds of starter words to select from. Qualified assignments writers can give you hundreds of them. How do you determine which of these essay starters will be the most impactful? Word selection mainly depends on the type of ideas being shared. Are you about to enter a counter argument or plan to introduce a new idea? Before you can begin hunting for the right words to start a new paragraph, do the following three steps:

- Determine what the previous paragraph discussed.

- Decide how the said paragraph will relate to the one before this?

- Now scan the appropriate list from the list to find a word that is best suited based on the purpose of the paragraph.

Keep the following tips in mind to make your paragraph starter words impactful and relevant:

- Always put a comma after every transition word in the beginning of a sentence.

- Add the subject of the sentence immediately after the comma.

- Avoid using the same transition word again and again. Opt for selecting different but suitable transition words.

- Don’t fret too much about using sentence starters during the first draft. It will be easier to add appropriate words during proofreading. Needless to say, always proofread your work to help make it flow better.

When looking for the right sentence starters for essays, make sure you are clear about the objective of every paragraph. What are you trying to tell? Is it an introductory paragraph or the body discussing ideas or contradictory information? The beginning of a paragraph should immediately reflect the ideas discussed within that paragraph. It might take some time, but with a little conscious effort and a lot of practice, using transition words would soon become second nature.

FAQ

What is a good word to start a paragraph?

The word you use to start a paragraph depends on the information you want to communicate. However, the right word to use should offer a smooth transition from the previous paragraph so readers can easily transition into the new section.

How do you start a paragraph example?

When writing essays that require evidence to support your claim, start your paragraph with the words like; For instance, For example, Specifically, To illustrate, Consider this, We can see this in, or This is evidence. That helps the reader to explain the ideas in the real world.

How to introduce a paragraph?

The best way to introduce a paragraph is by using a topic sentence that will briefly explain what you intend to discuss in the paragraph. Remember that the introduction of a paragraph is a topic sentence or the thesis of the entire essay.

How to start a second body paragraph transition words?

An essay shows the flow from the introduction to the last paragraph. Use transition words when writing a second body paragraph. By doing this, you show that the ideas in each section relate to each other.

What are some good words to start a conclusion paragraph?

Examples of words you can use are briefly, by and large, finally, after all, in any case, as a result, etc. After writing an engaging essay, ensure the conclusion paragraph is just as interesting by carefully selecting the types of words you will use.

What words to start a new paragraph?

You can begin with adverbs like Similarly, Consequently, or Conversely. Other words to start a new paragraph are: Nevertheless, That said, Alternately, At the same time, etc. Capture your readers’ attention by choosing the right words to use when starting a new paragraph.

The way you start a paragraph will determine the quality of your essay. Therefore, you need to be careful when choosing words to start a paragraph. The use of transition words to start a paragraph will make your text more engaging. These transition phrases will tell the reader that you know what you are doing.

Using the right keywords and phrases to start a new paragraph will link it to what you had said in the previous ones. We refer to these link phrases and words to as signposts. The reason is that they inform the reader when one point comes to an end and the beginning of the next one. The words or phrases also indicate the relationship between different points.

When you carefully use transition words to start a paragraph correctly, they will guide the tutors or examiners through your essay. Besides, these statements bolster the impression of a flowing, coherent, and logical piece of work. Here are some tips that will help you learn how to start an essay.

- Transition Words to Start a Paragraph

Transition words prompt the reader to establish relationships that exist between your ideas, especially when changing ideas. It is recommended to vary the transition words that you use in your text. Take time and think about the best transition words that will assist you in moving through the ideas you wish to put across. The most important thing is to help your readers get to understand the point that you are putting across. It is meaningless for students to produce academic papers that don’t flow well. For instance, you need different transition words to start a conclusion paragraph than what you use in body paragraphs and the introduction. Take time and make sure that all your points are flowing well within the text of the academic essay.

- Topic Sentences

You need to start with a topic sentence at ideas the beginning of ever paragraph. It gives you an exclusive opportunity to introduce what you will be discussing in the paragraph. The words that you use in the essay topic sentences should tell the reader of the ideas that you will be sharing in that paragraph. Remember each paragraph should carry a specific theme and this should be reflected in the topic sentences. You can use a transition phrase or word to elevate your topic sentence. It will tell the reader that you are now switching to a new idea.

- Organization

The way you organize your paper can also assist in boosting the transition of paragraphs. As you plan on the supporting ideas that you will include in your body paragraphs, you need to determine the orders that you will use to present them. Think about the best ways in which the ideas in each paragraph will build one another. You need to know whether there is a logical order that you need to follow. Try to re-arrange your ideas until you come up with the right order to present them. The transition words to start a body paragraph are very different from the introduction and conclusion.

- Relationships

In addition to how you write your academic essay, you can also enhance how you transition your paragraphs by discussing the relationships that exist between your ideas. For instance, as you end the first supporting paragraph, you can discuss how the idea will lead to the next body paragraphs. Assist the person reading your essay to understand the why you ordered your ideas the way you have done. What is the relationship between the first and second body paragraphs? Do not allow your readers to guess what you are thinking about or trying to communicate. The readers should also know how your ideas relate from the proper use of words to start a paragraph (see the picture below).

Examples of Transition Phrases and Words to Start a Paragraph

Transitions show how the paragraphs of your academic essay build of one another and work together. When you don’t use these transition words or phrases in your essay, it may end up having a choppy feeling. The readers may begin to struggle while trying to follow your thought train.

Due to this, you need to use paragraph transitions in all your essays. You have to make sure that you are choosing the right words to start a paragraph. In this section, we are going to look as some examples of sentence starters. You will discover that you choose the right transition words to start a body paragraph depending on what you are communicating. You may need transition words to show contrast, add to idea, show cause, or even add emphasis. Moreover, if you’re stuck with your paper and cannot find a motivation to write on, the sound use of words to start a paragraph may be your solution! So, here is a list of transition words that can help you in each category. You can use them as tips to get the right words to start a sentence and bring great expressions to the readers.

Transition Words and Phrases That Show Contrast

- Otherwise

- Instead

- Rather

- Comparatively

- Whereas

- However

- Conversely

- Still

- Nevertheless

- Yet

- On the other hand

- In comparison

- On the contrary

- Although

- In contrast

- Even though

- Different from

- Whereas

- Even though

- Other than

- Comparatively

- Besides

- Outside of

Transition Words and Phrases to Add to Idea

- Additionally

- For example

- Again

- Also

- Moreover

- In addition

- Coupled with

- Furthermore

- Similarly

- As well as

- In deed

- One other thing

- Correspondingly

- In fact

- Whereas

- Another reason

- Identically

- Along with

- Like wise

Transition Words and Phrases That Show Cause

- Accordingly

- Particularly

- Hence

- Singularly

- As a result

- Otherwise

- Usually

- Because

- Generally speaking

- Consequently

- Unquestionably

- For the most part

- Due to

- In this situation

- For this reason

- Undoubtedly or no doubt

- For this purpose

- Obviously

- Hence

- Of course

- Otherwise

- Ordinarily

Transition Words and Phrases That Add Emphasis

- As usual

- As a rule

- Above all admittedly

- Granted

- Especially

- Chiefly

- Certainly

- Assuredly