Increasing your IELTS Vocabulary is essential for a higher Band Score, but what exactly is “IELTS Vocabulary” and which list should we trust?

I did a quick search on Google and it brought up probably the worst and most confusing list that I’ve ever seen in my life (see extract below).

So I asked Word List expert Sheldon Smith to help me learn more about where to find the best word lists for IELTS students.

Sheldon’s website is EAPFoundation.com and he creates the BEST topic-related vocabulary videos for IELTS students, so make sure that you go to his site for all the links in this blog, and subscribe to his YouTube channel.

In this blog he kindly shares with us his knowledge and experience of the most reliable word lists and how you can use them. He also answers some of my Members Academy students’ questions.

The 4 main lists are:

- The Academic Word List (AWL)

- The General Service List (GSL)

- The Academic Vocabulary List (AVL)

- The Academic Collocation List (ACL)

1. The Academic Word List (AWL)

What is the common mistake about using wordlists? (Pam)

The Academic Word List (AWL) is the most well-known word list. It existed without any real ‘competition’ for a long time, but it has also been criticised. This led to the emergence of other word lists.

The Academic Word List was intended to help reading, not writing. It includes complete word family information for each word, but these different word forms have different levels of frequency, and trying to study them all may end up wasting time and effort.

Many recent lists, therefore, do not include word family information, but instead show inflected forms, for example for ‘analyse’ we have only

- ‘analyses’

- ‘analysed’

- ‘analysing’

plus variant spellings (with ‘z’).

The word ‘analysis’ is considered to be separate.

Another problem with the AWL is that coverage varies across disciplines. It is supposed to be about 10% of academic texts, but for computer science it is 16%, while for biology it is 6.2%.

(This information is from a well-known article called Is There an “Academic Vocabulary”? by Ken Hyland and Polly Tse, published in TESOL Quarterly, June 2007).

2. The General Service List (GSL)

Another problem with the AWL for productive (i.e. writing) purposes is that it excludes the General Service List (GSL). For reading purposes, this is not a big problem, since most students will know most words in the GSL already.

For productive purposes, however, it is potentially an issue, since some of the words in the GSL are suitable for academic use.

Indeed some GSL words are more common in academic than general English (e.g. thus, suggest, likely), while some words are far less common (e.g. bad, big, know), and students studying academic English need to identify which are which in order to make the ‘vocabulary shift’ from general to academic.

To answer Pam’s question, one common mistake with word lists is only using the AWL, and thinking it is a perfect list. It is a good list, and has its advantages, but it also has drawbacks as shown above.

Another mistake is only studying single words, which in a way is the fault of word lists, most of which comprise only single words.

Another problem (not necessarily a mistake) is studying the whole word family, including less frequent members, which may not be an efficient use of time and effort.

3. Academic Vocabulary List (AVL)

What is the best wordlist for IELTS preparation? Why?

Since IELTS is not subject specific, a general academic list, which is intended for students studying any discipline, is more suitable than a subject-specific list.

The AWL is a general list, and may be the most helpful, since there are a lot of resource and practice materials available.

However, there are other general lists besides the AWL. One that I think is especially useful is the Academic Vocabulary List (AVL) is very useful. This is a more recent list, and, unlike the AWL, it does not exclude any list, meaning it covers words that might be considered ‘general’ words, but which are in fact more frequent in academic than non-academic writing.

For example, the following words are in the top 50 of the AVL but not in the AWL: control, develop, development, figure, however, human, provide, rate, relationship, report, suggest, practice.

4. The Academic Collocation List

Another general academic list I think is very useful is the Academic Collocation List (ACL).

It is important to understand how words combine with other words, and there is no other comprehensive list of collocations available.

The list is pretty huge, with 2469 collocations, though I recently spent a lot of time adding frequency information to the list, which is not officially sanctioned by the list creators, but I think is extremely useful.

An example of a terrible IELTS Word List

How to use word lists for IELTS

Why is it important to use these ‘official’ word lists?

None of them are actually ‘official’. Some of the more well-known ones are used as the basis for academic English courses, especially the AWL.

Each list has its critics who tell you not to use it. Generally, however, they are a good starting point.

It is important to use them. Otherwise, the words you choose to study come from one of two sources: either you select them, or a teacher chooses them.

If you select them, you really have no basis, except that you don’t know the meaning. Is it a common word? Is it worth studying? It is extremely difficult for you to know which words you should learn. This is why word lists are useful.

If a teacher chooses the words you should learn , a similar problem arises. A teacher may have a better ‘feel’ for which words to study, though essentially they are relying on intuition, and their intuition may be wrong.

I personally feel I have a good understanding of which words students will or will not know, which words are academic and useful for study, but I am continually surprised, and see words that I think are useful but which turn out to be rather low frequency in academic English.

What is the difference between all the word lists?

I’ve covered this above, but I’d like to highlight here the many different subject specific lists.

Anyone preparing for IELTS should realise that this is a stepping stone to university study. You will eventually specialise, and knowing academic words or technical words which are common in your discipline will also be important.

It’s also useful to remember that although word lists are the result of fairly rigorous research, not so much research has been done in how useful specific lists are. Some may be better than others.

Finally, word lists are just a tool. There are many useful words, general, academic and technical, which are not contained in word lists, and conversely some words in word lists that you will never end up needing or using.

Are there different lists for Spoken and Written English?

While most academic word lists are for written English, there are also word lists for spoken English. e.g. the Hard Science Spoken Word List (HSWL) or the Academic Spoken Word List (ASWL).

Generally, I don’t see these as so interesting or useful, since the ‘rules’ for academic speaking are not as strict as for academic writing. Words you can use in writing can be used in speaking, but the reverse is not true. For example, when giving a presentation (academic speaking), you can (and probably should) use basic transitions such as ‘So’ and ‘And’ and ‘But’ since they are clear and simple.

However, you should probably avoid these in your writing. Conversely, if you use ‘As a result’ and ‘In addition’ and ‘However’ in academic speaking, you will sound a bit formal, but there is nothing wrong with those words. No one will stop you and say, ‘Hey, you can’t use that word in your speaking.’

What is the best way to learn from these word lists?

I personally feel it is better to study words from reading (or listening) texts you already have, and identify useful words from some of the word lists.

However, this approach has its limitations. I know some courses might use lists such as GSL 2k or the AWL as a basis, and test students on any of those words. Therefore being proactive and studying unknown words in those lists might be helpful.

Also if you want to increase your vocabulary, and aren’t sure where to start, the lists are useful for that.

Is it better to learn a few words and use them well, or to learn many words in order to read faster and understand the listening better (active vs. passive knowledge)?

Ideally, both, by studying the more frequent words e.g. AWL or AVL in more depth for active use, but continuing to study less frequent words at least for recognition i.e. passive use, and generally ignoring the very low frequency words.

There are tools such as vocabulary profilers to help identify how frequent words are, but generally speaking, those in a recognised word list are frequent enough for students to be studying for active use.

How many words should I learn?

All of them! No, just kidding. I’ve mentioned the 8000-9000 range a few times, which comes from research (there is a useful article on this written by Schmitt and Schmitt called ‘A reassessment of frequency and vocabulary size in L2 vocabulary teaching’).

But there are different levels of knowing a word, and therefore different degrees of learning. Native speakers don’t know all the words in English, and the number they do know, which is impossible to measure anyway, is not useful.

I’ll share an anecdote to maybe explain this point. At university, I studied Mathematics, but I always wanted to be a writer so I spent most of my time reading novels and travel books. There were a lot of words I didn’t know and I would jot them down in a notebook and look them up.

One day when I was in my thirties I found one of these notebooks, which I had made when I was in my early twenties, and I looked through all these pages of words, and the thing is, I knew almost all of them, and was surprised I’d written them down and didn’t know them before. So I’m a native speaker, but in my twenties there were so many words I didn’t know, and I chose to study and learn to expand my vocabulary.

I’m pretty sure the average native speaker would not know many of the words I’d written down, since the average native speaker doesn’t read as much as I did, and doesn’t bother studying new words all that much.

So, forget about how many words you should learn, and focus instead on the conscious act of choosing to study new words when you encounter them, and slowly build up your vocabulary. You might feel like the tortoise competing against the hare. You might be far behind now, but keep going slowly step by step and you can catch up.

How can I remember new words and collocations? I often make a mistake in putting the wrong word in a full sentence. How can I use the words more accurately?

It’s important to study many aspects of a word, and which aspects depend on how you plan to use it. Many students just focus on meaning (often by translation). This is generally how they started learning vocabulary in school. This is fine if all you want to do with a word is recognise it when you read it, and for many words, that may be enough.

But if you want to use it, then you need to know how to pronounce it (to use it in speaking, also essential for listening), part of speech (n, v, adj, adv), other members of the word family, any special spelling rules, how it combines with other words (collocation), usage (e.g. followed by preposition ‘of’ or ‘with’ or ‘doing’ vs. ‘to do’), and whether it is academic or informal.

It is not easy studying this kind of information (a good dictionary will be essential), and you will still make mistakes when using the words.

Recording words in a vocabulary notebook is a good idea, with some of the information above (pronunciation, part of speech, usage and so on). You may encounter the words again when reading and want to add more information later.

Trying to use words you’ve recently studied is also helpful, and hopefully you can get feedback (for speaking, feedback could be a nod of understanding or look of puzzlement, for writing if you have a teacher they may identify errors, or you can explicitly ask, ‘Can you check these words, have I used them in the right way?’).

Short answer: Remembering and using vocabulary accurately takes a lot of time, and a lot of effort, and involves going beyond just the meaning of a word. You will always make mistakes, but the goal should be to expand your vocabulary and have mistakes decrease.

How can I use the memorized words naturally and avoid mechanism (being mechanical?)?

Yes, ‘being mechanical’ is the correct phrase – I think this is a good example of some of the points above, and also a good demonstration of what is called an ‘achievement strategy’.

Good language learners try to use words they know to express the meaning they want, while less able learners try to avoid words or phrases (or grammar structures) they are unsure of, which is called a ‘reduction strategy’.

By attempting to use phrases like ‘mechanism’ and ‘being mechanical’ you can receive feedback and correct errors.

Self noticing is also important, as you find words or phrases you are unsure of and hopefully take the time to check or ask how to use them properly.

You have probably heard this before, but reading more is the best way to learn new vocabulary, as long as you are being active. This is great not just for identifying new words to study, but also for reinforcing words you have already learned, if you encounter them again.

For example, you might forget whether ‘mechanism’ or ‘being mechanical’ is correct, but if you read a passage with either of these words in it you will pay attention and reinforce what you know about the words in a more natural way.

How can I choose the right words and collocations? And how can I group them?

I’ve been creating a series of videos recently on different common IELTS/TOEFL topics (physical health, environment, crime – see example below), using word lists, since it is known that it is easier to remember words if they are linked somehow, e.g. a common topic.

A different approach is how to choose words and collocations from a topic you are reading about. I would suggest using tools such as word list highlighters. It can be difficult to know which words to study, but if they are in a recognised word list, that should be a good start.

Going beyond those word lists can be important, as explained in the videos I’ve been making. Comfortable reading requires 8000-9000 words, while common word lists generally only take things to the 3000 word level.

If you can group words according to topic, that might help you to remember them. But if you are studying, for example, different word forms of ‘analyse’ (e.g. ‘analyst’, ‘analytic’, ‘analysis’) you are also grouping the words in a meaningful way.

Alternatively, you might want to study common adjective collocations e.g. with ‘analysis’: careful/critical/detailed/final/further/statistical analysis and that is another way to group them.

More help with IELTS Vocabulary Lists

- Sheldon’s Vocabulary Profiler (use this tool to analyse vocabulary in the text and identify which words are from different lists and highlighting them in a text – VERY useful)

- IELTS Vocabulary resources (links to the best websites)

- 28 ways to improve your IELTS Vocabulary

- How to learn vocabulary from IELTS texts

- Word formation practice for IELTS

- How vocabulary is the solution to your IELTS plateau

- How to use practice tests to improve your vocabulary.

- IELTS topics: crime (Band 9 model essay)

- How (not) to use idioms in IELTS

Do you need motivation, high-quality materials, a roadmap, feedback, guidance and an IELTS specialist teacher?

Join the Members Academy today.

Get instant access to all courses, challenges, boot camps, live classes, interactive and engaging classes, 1:1 support, and a friendly tight-knit community of like-minded learners to get you to Band 7+.

clicking here.

This message will disappear when then podcast has fully loaded.

There are many word lists for general and academic English study. This page gives information on

why word lists are important, then presents ideas about

how to use word lists.

There is a companion page in this section which gives

a detailed overview of the many different word lists available for academic English study.

Why are word lists important?

One reason word lists are important is they enable learners to narrow the focus of what to study.

English is estimated to have around 1 million words, with around 170,000 words in current use. The average native speaker knows between 20,000 and 35,000

words. These are daunting totals for learners of English. However, some words are more frequent than others. The most common 10 words in English account for

around 25% of language use (this figure is similar across all languages). The most frequent 100 words account for around 50%, while the most frequent

2000 words cover approximately 80% of words in texts. Word lists therefore provide students with an efficient way to focus on the vocabulary they need in

order to understand or produce texts.

Word lists are also important since they provide a clear starting point. Learners often know they need to improve their vocabulary, but do not know

where to begin, while teachers may not focus on vocabulary except in an incidental (i.e. accidental) way, for example when difficult words are encountered

in a text. Word lists enable students and teachers to decide which words in a text deserve particular attention, such as academic words, as well as

providing them with a list that can be worked through systematically.

Word lists also provide a clear end point. By knowing which words should be studied during a period of time (a week, a month, or an entire course),

it is possible to set vocabulary learning goals and measure vocabulary growth.

Academic word lists are important since academic words may be new

and challenging for students, but may not be taught by subject teachers. This is in contrast to

technical words, which, because of their importance and specialist nature,

are likely to be explained by teachers. Academic vocabulary is usually defined as words which are used more frequently in academic than in non-academic

English texts, and without word lists learners may be unsure of precisely which words are used more commonly in academic English.

Word lists are also important for teachers, since they enable them to analyse and modify texts for classroom use, and to design suitable courses.

In short, word lists allow students and teachers to:

- narrow the focus of what vocabulary to study;

- know where to start studying;

- know what the end point is;

- set vocabulary learning goals;

- assess vocabulary knowledge and growth;

- identify important words which may not be taught.

In addition, word lists allow teachers to:

- analyse texts;

- modify texts for classroom use;

- design courses.

How can word lists be used?

Word lists are most often used by teachers when designing courses or creating lessons. However, students studying independently

also have many options available for using lists to improve their vocabulary knowledge.

Word lists are often big, daunting lists, containing hundreds or thousands of words. One tip for using word lists is to break them

down into more manageable lists. Some lists are presented in this way, for example the

AWL (Academic Word List), which is divided into 10 lists (called sublists) of 60 words each (30 for the

final list). Many other lists are not divided into sublists; however, if the lists are ranked by frequency, students or teachers can divide up the lists

themselves, for example by creating a certain number of equal sized sublists (e.g. 10 sublists), or dividing the list into sublists of equal size

(e.g. 50 words in each). It is always best to start studying the most frequent words first, since these are the one which will be encountered most often.

If the list will be used to assess learning, it is important to ensure that it is fully covered, and there are two approaches to this.

The first and simplest is the series approach, which involves going through the list systematically, e.g. learning all words in sublist 1 of the AWL

before moving on to sublist 2. The second approach is the field approach, which involves learning words from the list as they

occur in reading or listening texts. The second approach is more suited to teachers, who can modify texts to ensure there is complete coverage of the list

in a course of study. Students, however, could also use the field approach, for example by keeping a record of which words they have

encountered in a text, though at a certain point, they would have to switch to a series approach to ensure they learn the remaining words, since the

number of new words from the list which occur in new texts will steadily decrease to zero or almost zero. For example, if you have learned 569 words in

the AWL, you may need to read dozens of texts before encountering the final word, which would not be an efficient use of time.

Whether studying words by a series or field approach, it is useful to assess knowledge of words, either formally through testing, or informally by

self-assessment. This can be done before, during or after learning. If self-assessing, the following scale could be used, which would then guide further study.

There are various reading activities that can be used to increase knowledge of vocabulary. They include jigsaw reading (students read different

parts of the same text, then share their knowledge), narrow reading (students read multiple texts on the same topic, then discuss or write about

the topic) and close reading (students read and reread texts to increase knowledge and understanding). These activities are more effective for

technical word lists, since if discussing a topic such as photosynthesis students will need to use relevant technical vocabulary in

order to describe it; however, if discussing a text which has the target words analyse, concept and data (from AWL sublist 1), students could

very well do this using other words, unless specifically directed to use them, e.g.: Summarise what you just read. Include these words in your summary:

analyse, concept, data.

There are many hands-on tools that students can use to identify and study words from word lists. These include:

- word list highlighters, such as

the AWL highlighter on this site, which allows for manipulation of sublists and creation of a gapfill activity, which can be used to test vocabulary knowledge; - the ACL mind map creator, which provides a useful way to explore collocations of individual words in the

ACL (Academic Collocation List); - a vocabulary profiler, which not only identifies words in different lists e.g. GSL vs. AWL,

but also shows percentages of words in each. - to have an effect on

- to contribute to (sth)

- to play a role in (sth)

- break down lists into smaller lists, and focus on studying the most frequent words first;

- ensure the list is fully covered by using a series approach (e.g. AWL sublist 1, then sublist 2);

- ensure the list is fully covered by using a field approach, e.g. by modifying texts (teachers) or keeping a record of which words have been encountered (students);

- test students on vocabulary knowledge (teachers) or self-assess in order to know which words to study in more detail (students);

- use communicative reading activities (esp. for technical word lists);

- use hands-on tools such as word list highlighters, the ACL mind map creator, or vocabulary profilers;

- study detailed information of a word, using a dictionary or other tools;

- keep a detailed vocabulary notebook.

The last item, a vocabulary profiler, is a useful tool for teachers, who can use it to grade texts to control the number of new or challenging words.

It is also for students, who can appraise their own writing and see how many words and what type they have used. For example,

since the AWL accounts for around 10% of words in academic texts, students can use a vocabulary profiler to see how close (or how far) their own writing

is from this target (though it should be emphasised that this is a rough guide, and not something they should aim for by forcing AWL words into their writing).

Unless a word is only needed for reading comprehension, it is going to be important for students to study

information about the word other than its definition before they can be confident that they ‘know’ the word. This includes

pronunciation (for comprehension while listening or use in speaking), word family information (for flexible use in writing or speaking, or recognition in

reading), and information about collocations and how the word is used in a sentence, for example:

For words in the AWL, much of this information can be gained from the

AWL finder (on this site). Often,

use of a dictionary will be essential.

It will also be important for students to use

vocabulary notebooks to record important information in order to review it later and

consolidate vocabulary knowledge. Notebooks could be physical or electronic. Students can return to their notebook to add more information about a word

if they encounter it again. Teachers can encourage notebook use by giving tests which allow students to access their notebooks.

In short, the following are useful ways students or teachers could use word lists:

Summary

In short, there are many

reasons word lists are important, ranging from narrowing the focus of what vocabulary to study to assessing

vocabulary knowledge and growth. In addition, although word lists may have a negative connotation, being linked to rote learning, there are many

useful and engaging activities that both teachers and students can use to focus on appropriate target vocabulary.

For more information on individual word lists, check out the

overview of word lists page, which includes a summary of the most important general, academic, and technical word lists.

References

Greene, J.W. and Coxhead, A. (2015) Academic Vocabulary for Middle School Students. Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Company.

Nation, I.S.P (2016) Making and Using Word Lists for Language Learning and Testing. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

GET FREE EBOOK

Like the website? Try the books. This extract from Unlock the Academic Wordlist: Sublists 1-3 contains all sublist 1 words, plus exercises, answers and more!

As students encounter new phrases and words they have not heard before, it might be a good idea to motivate the use of word lists. Yet, we do not want students to constantly translate or keep searching for words. In this post I will answer the question if you should use word lists and if so, how.

Estimated time to read this article: 8 minutes

Why word lists might not be a good idea

Let’s start with the obvious statement I posed in the title: Should you use word lists?

There are a lot of different ways to implement word lists in a lesson.

Some of the good, other ones maybe less so.

Keeping this in mind, what might be reasons NOT to use a word list?

1. Students translate words

Students have to understand the words and phrases they discuss both in their mother tongue as well as in the second language.

But we want them to primarily focus on the second language when we motivate them to speak in class.

The best way to get them to do this, is by making sure they start ‘thinking’ in English as soon as possible.

In other words: we do not want them to translate every single word while they work.

When word lists with translations are allowed, students might use those to constantly check how to say something, instead of automating the use of the English word.

2. Students lose their word lists

I might not be the most organised guy around, but students regularly surprise me with their attitude towards needed materials for a lesson.

«I forgot my dairy»

«I lost my notebook»

«I don’t have a pen»

-Sigh-

Anyhow, with this attitude it is no surprise students lose word lists constantly.

A way to organize this could be to have one notebook for all word lists.

But that assumes they bring that one notebook as well…

Key Take Away

Whenever you want to use word lists, make sure you think about ‘how’.

Seriously, is that all?

I know, I know.

I played Devil’s Advocate just now.

My point is: think about how to implement word lists.

Don’t just assume students keep track of difficult words themselves.

Or assume the word list in the back of the book is sufficient (it is not!)

But think about how to use word lists in a way they actually support the learning process of students.

In other words: How can you use word lists effectively?

How to make effective word lists

Just as a precaution: remember I do not pretend to have all the answers.

I simply share my ideas, inspired by colleagues, teachers and scholars.

Having said that, there are (at least) two things to keep an eye on when working with word lists:

-

1

Is the word list subject specific or cross-curricular?

-

2

Do you want to use translations or explanations?

Subject specific vs. cross-curricular

To answer the first question: that is entirely up to you of course. It is just something to be aware of.

Personally I only use subject specific word lists. Simply because cross-curricular ones need a lot more organizing.

Yet, for students this might be a good way to organize things. Instead of multiple word lists, they might only need one.

Translations vs. explanations

The second question is more interesting in my opinion.

Translating is something I think should be limited as much as possible.

Students should start ‘thinking’ in the second language as soon as possible and stop translating everything constantly.

Of course they have to know what a word means when they first encounter it, but soon after they should be able to use it.

In context. In the second language.

So asking students to explain what a word means, or provide example sentences to be used with these words, is a great way to help them remember the word.

That is also the reason we use Cambridge Dictionaries at our school: English to English, not to Dutch.

Key Take Away

There is not one ‘best’ way of working with word lists, but you do have to think about its purpose.

Do you want to provide scaffolding?

Do you want students to be able to explain the words?

These questions influence the way you work with word lists.

Student or teacher generated word lists?

Another thing to keep in mind is who actually creates the word lists?

Teacher or student?

Actually, both are okay.

But (again) only if you think about the how and why.

In other words: in what situations is it better for a teacher to provide a word list?

This can be in various occasions like:

- Text heavy subjects like biology or geography, when starting with a new topic

- As a reminder of words that can be used while working on the homework

- A summary of the important words studied in this section.

Just like there are good reasons to provide a teacher- generated word list, there are various reason to ask students to create their own.

- More personalized: students write down the words they personally find hard

- More creativity: You can ask different students for explanations and clarifications

- In one place: Word lists can be kept with their regular notes

Scaffolding with word lists

With scaffolding you provide structure to help students improve.

Word lists can be used as a scaffolding tool as well.

For example: students can be provided with a word bank of academic words they can/have to use in order to introduce CALP in the classroom (or at least to trigger the use of more ‘advanced’ language)

Another way of scaffolding is by providing word lists accompanied by tasks. The purpose of these word lists would be to lower the language barrier in order for students to be able to complete the subject related task that might be a challenge otherwise.

3 activities to implement word lists

Okay, enough ideas and theoretical knowledge, let’s talk practical lesson ideas!

These three ways of using word lists are used at various moments in a lesson and are both student as well as teacher generated.

1. Brainstorm

The brainstorm activity is … well, a brainstorm activity.

You ask your students to write down everything they down related to a certain topic.

The main reason to do this is to activate prior knowledge, the brainstorms can also be used in a follow-up task.

Practical example: I write all of my blog posts after a brainstorm.

It was suggested in the CLIL Community students could even further enhance the brainstorms by adding adverbs, verbs, etc.

Mentioning these specific additions is again a form of scaffolding by the way.

This can be done at the beginning of a new lesson to see what students still remember, but also at the beginning of a new topic to see if anyone can link it to knowledge they already posses.

2. Scan the chapter/Scrambled word

Both favorites of mine: I use one of these activities whenever I start a new chapter.

Students scan the chapter for difficult words and write these down. Whenever I discuss these words during the lessons that follow, they have to complete the word lists.

Obviously, they forget this quite often. That is why I go back to this word list at the end of the chapter and ask students to complete it.

This is quite often a moment of realization for them: they notice the words they did not know before but do know now.

Another way to finish up at the end of the chapter might be providing a crossword puzzle with all of the difficult words that should have been in their word lists.

That way there are certainly motivated to figure them out!

Scrambled word works the same way, but instead of asking them to find new words, I actually make a list of the most important words of the chapter, scramble these and provide the students with the list.

They have to find the original words, and we discuss those afterwards obviously.

3. Guess the topic

This is like a backwards-brainstorm.

Instead of dropping the topic and asking students to come up with the related phrases, students receive a couple of words and have to guess the topic of that lesson.

This is a great way to scaffold the prior knowledge, they might not realize the topic is related to so many different things.

Conclusion

Word lists are not evil.

But, they should be used to support the use of the second language, not as a translation tool.

And by using them for scaffolding or during activities, they are no longer the passive word lists that can be found in the books (hopefully) or on Google Translate (because…seriously?)

(«Iversen’s method»)

A word list technique is in its most common form a list of words in a target language with one translation of each word into another language, here called the base language. However, you can use short idiomatic word combinations instead of single words, or you can give more than one translation into the base language, and it will still be a word list. You can also add short morphological annotations, but there isn’t room for examples or long comments in a typical word list. Lists of complete sentences with translations are not word lists.

There are also word lists with just one language (frequency lists) or with more than two languages. The so called Swadesh lists (named after Morris Swadesh) contain corresponding lexical items from a number of languages, typical 100 or 200 items chosen among the most common words. Both these lists can be valuable for a language learner who wants to make sure that s(he) covers the basic vocabulary of a target language.

Dictionaries can be seen as sophisticated word lists, where the target items (lexemes) are put in alphabetical order, and where the semantic span of each lexeme is illustrated through the use of multiple translations, explanations and examples, sometimes even quotes. In addition good dictionaries give morphological information about both the target language and the base language words. However the amount of information in dictionaries varies, and the most basic pocket dictionaries are hardly more than alphabetized word lists.

Using word lists[]

The most conspicuous use of word lists is the one in text books for language learners, where the new words in each lesson are summarized with their translations. However they are also an important element of language guides used by tourists who don’t intend to learn the language of their destination, but who need to communicate with local people. In both cases the need to cover all possible meanings of each foreign word is minimized because only some of them are relevant in the context, — in contrast, a dictionary should ideally cover as much ground as possible because the context is unknown.

Using word lists outside those situations has been frowned upon for several reasons which will be discussed below. However they can be a valuable tool in the acquisition of vocabulary, together with other systems such as flash cards. The method that is described below was introduced by Iversen in the how-to-learn-all-languages forum as a refinement of the simple word lists, and it was invented because he found that simple word lists weren’t effective when used in isolation (except for recuperation of half forgotten vocabulary).

Links:

[Super-fast vocabulary learning techniques, many pages]

[Iversen’s thread in the forum ]

Methodology[]

One basic tenet of the method is that words shouldn’t be learnt one by one, but in blocks of 5-7 words. The reason is that being able to stop thinking about a word and yet being able to retrieve it later is an essential part of learning it, and therefore it should be trained already while learning the word in the first place. Normally people will learn a word and its translation by repetition: cheval horse, cheval horse, cheval horse… (or horse cheval cheval cheval cheval….), or maybe they will try to use puns or visual imagery to remember it. These techniques are still the ones to use with each word pair, but the new thing is the requirement that you learn a whole block of words in one go. The number seven has been chosen because most people have an immediate memory span of this size. However with a new language where you have problems even to pronounce the words or with very complicated words you may have to settle for 5 or even 4 words, — but not less than that.

Another basic tenet is that you should learn the target language words with their translations first, but immediately after you should practice the opposite connection: from base language to target language. And a third important tenet is that you MUST do at least one repetition round later, preferably more than one. Without this repetition your chances of keeping the words in your long time memory will be dramatically reduced.

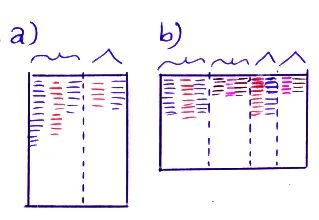

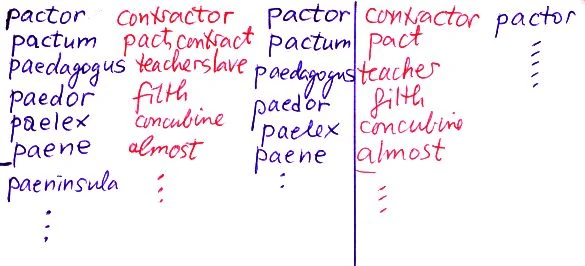

This is the practical method: Take a sheet of paper and fold it once (a normal sheet of paper is too cumbersome, and besides you need too many words to fill it out). If you have a very small handwriting you can draw lines to divide it as shown as b) below, otherwise divide it into two columns as shown under a). The narrow columns are for repetition (see below). Lefthanders may invert the order of the columns if that feels more comfortable. Blue: target language, red: base language. Curvy top: original column, triangle top: repetition column

Now take 5-7 words from your source and write them under each other in the leftmost third of the left column. Don’t write their translations yet, but use any method in your book to memorize the meanings of these 5-7 words (repetition, associations), — if you want to scribble something then use a separate sheet. Only write the translations when you are confident that you can write translations for all the words in one go. And use a different color for the translations because this will make it easier to take a selective glance at your lists later. If you do fail one item then look it up in your source, but wait as long as possible to write it down — postponement is part of the process that forces your brain to move the word into longterm memory.

OK, now study these words and make sure that you remember all the target language words that correspond to the translations. When you are confident that you know the original target words for every single translation you cover the target column and ‘reconstruct’ its content from the translations. Once again: If you do fail one item then look it up in your source, but wait as long as possible to write it down (for instance you could do it together with the next block) — the postponement is your guarantee that you can recall the word instead of just keeping it in your mind. So now you have three columns inside the leftmost column, and you are ready to proceed to the next block of 5-7 words. Continue this process until the column is full.

There isn’t room for long expressions, but you can of course choose short word combinations instead of single words. It may also be worth adding a few morphological annotations, but this will vary with the language. For instance you could put a marker for femininum or neuter at the relevant nouns in a German wordlist, — but leave out masculinum because most nouns are masculine and you need only to mark those that aren’t. Likewise it might be a good idea to indicate the consonant changes used for making aorists in Modern Greek, but only when they aren’t self evident. In Russian you should always try to learn both the imperfective and the corresponding perfective verb while you are at it, and so forth. You can’t and you shouldn’t try to cram everything into your word lists, but try to find out what is really necessary and skip the details and the obvious.

Sources[]

You can get your words from several kinds of sources. When you are a newbie you will probably have to look up many words in anything you read in the target language. If you write down the words you look up then these informal notes could be an excellent source, — even more so because you have a context here, and it would be a reasonable assumption that words you already have met in your reading materials stand a good chance of turning up again and again in other texts. Later, when you already have learned a lot of words, you can try to use dictionaries as a source. This is not advisable for newbies because most of the unknown words for them just are meaningless noise, but when you already know part of the vocabulary of the language (and have seen, but forgotten countless words) chances are that even new unknown words somehow strike a chord in you, and then it will be much easier to remember them. You can use both target language dictionaries and base language dictionaries, — or best: do both types and find out what functions best for you.

Repetition[]

As mentioned above repetition is an indispensable part of the process, and it should be done the next day (preferably) or just later on the same day. The repetition can of course be done in several ways, but in the two layouts above there are special columns for this purpose, — it is easier to keep track of your repetitions when they are on the same sheets as the original wordlists. However these column are only subdivided in two parts, one for the words in the base language, the other for the target language words. So you copy 5-7 base language words from the original wordlist, cover the source area and try to remember the original target language words. If you can’t then feel free to peek, but — as usual — don’t write anything before you can write all 5-7 words in one go. An example with Latin and English words:

Addendum ccccccc

The combined layout was the one I developed when I had used three-column wordlists for a year or so and found out that I had a tendency to postpone the revision — having it on the same sheet as the original list would show me exactly how far I had done the revision, and I would only have to rummage around with one sheet. And for wordlists based on dictionaries or premade wordlists (for instance from grammars) it is still the best layout. But I have since come to the conclusion that it isn’t the most logical way to do the revision for wordlists based on texts, especially those which I had studied intensively and maybe even copied by hand. Here the smart way to work is to go back to the original text (or the copy) and read it slowly and attentively while asking myself if I know and really understood each and every word. I had put a number of words on a wordlist because I didn’t know them so if I now could understand them without problems in the context then I would clearly have learnt something — and I would also get the satisfaction of being able to read at least one text freely in the target language. If a certain word still didn’t appear as crystal clear to me then it would just have to go into my next wordlist for that language. So now I have dropped the repetition columns for text based wordlists.

Then what about later repetitions? After all, flash cards, anki and goldlists all operate with later repetitions. Personally I believe more in doing a proper job in the first round (where there actually are several ‘micro-repetitions’ involved), but it may still be worth once in a while to peruse an old wordlist. My advice here is: write the foreign words down, but only with translation if you feel that a certain word isn’t absolutely well-known — which will happen with time no matter which technique you have used. The format doesn’t matter, but writing is better than just reading — and paradoxically it will also feel more relaxed because you don’t have to concentrate as hard when you have something concrete like pencil and paper to work with.

Memorization techniques and annotations[]

When you write the words in a word list you shouldn’t aim for completeness. If a word has many meanings then you may choose 1 or 2 among them, but filling up the base language column with all sorts of special meanings is not only unaesthetic, but it will also hinder your memorization. Learn the core meaning(s), then the rest are usually derived from it and you can deal with them later. Any technique that you would use to remember one word is of course valid: if you have a ‘funny association’ then OK (but take care that you don’t spend all your time inventing such associations), images are also OK and associations to other words in the same or other languages are OK. The essential thing in the kind of wordlist I propose here is not how you do the actual memorization, but that you are forced to do it several times in a row because of the use of groups, and that you train the recall mechanism both ways.

It will sometimes be a good idea to include simple morphological or syntactical indications. For instance English preposition with verbs, because you cannot predict them. Such combinations therefore should be learnt as unities. For the same reason I personally always learn Russian verbs in pairs, i.e. an imperfective and the corresponding perfective verb(s) together. With strong verbs in Germanic languages you can indicate the past tense vowel (strong verbs change this), and likewise you can indicate what the aorist of Modern Greek verbs look like — mostly one consonant is enough. There is one little trick you should notice: if you take a case like gender in German, then you have to learn it with each noun because the rules are complicated and there are too many exceptions. However most nouns are masculine, so it is enough to mark the gender at those that are feminine or neuter, preferably with a graphical sign (as usual Venus for femininum, and I use a circle with an X over to mark the neutrum). This is a general rule: don’t mark things that are obvious.

Arguments against using word lists[]

Finally: which are the arguments against the methodical use of word lists in vocabulary learning?

One argument has been that languages are essentially idiomatic, and that learning single words therefore is worthless if not downright detrimental. There is a number of very common words in any language where word lists aren’t the best method because they have too many grammatical and idiomatic quirks, — however you will meet these words so often that you will learn them even without the help of word lists. On the other hand most words have a welldefined semantic core use (or a limited number of well defined meanings), and for these words the word list method is a fast and reliable way to learn the basics.

Another argument is that some people need a context to remember words. For these people the solution is to use word lists based on words culled from the books they read.

A third argument is that the use of translations should be avoided at any costs because you should avoid coming in the situation that you formulate all your thoughts in your native language and then translate them into the target language. But this argument is erroneous: the more words you know the smaller the risk that your attempts to think and talk in the target language fail so that you are forced to think in your native language.

A fourth argument: word lists is a method based entirely on written materials, and many people need to hear words to remember them. This problem is more difficult to solve, — you could in principle have lists where the target words were given entirely as sounds (or as sounds with undertexts), but you would have serious problems finding such lists or making them yourself. But listening to isolated spoken words is in itself a dubious procedure because you hear an artificial pronunciation and not the one used in ordinary speech. However the same argument could be raised against any other use of written sources, except maybe listening-reading techniques.

A fifth argument: there is a motivational problem insofar that many people prefer learning languages in a social context, and working with word lists is normally a solitary occupation. It might be possible to invent a game between several persons based upon word lists, but it would not be more attractive or effective than the forced dialogs and drills used in normal language teaching.

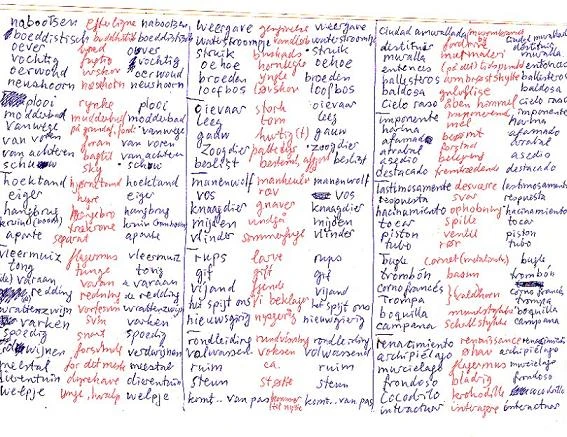

Finally an example based on Dutch-Danish and Spanish-Danish (based on an older layout without repetition columns):

Alternatives[]

Of course there are alternatives to wordlists: the most extreme is the exclusive use of graded texts as the most vehement adherents of the natural method propose. I don’t understand their motives, but respect their bravery. However I do understand the unorganized use of dictionaries plus genuine texts, but frankly I think there is room for improvement in that method.

Finally, there are well-structured alternatives like paperbased flashcards and electronic versions of these, all based on the notion of ‘spaced repetition’: Anki, Supermemo. However I can’t give advice concerning these systems because I haven’t tried them myself.

Main source for this article at Iversen’s Guide to Learning Languages (HTLAL forum)

One of the most popular ways of tackling deliberate vocabulary learning is word lists — the brand new Cambridge Dictionary +Plus feature has some great resources to help learners get on top of new lexis.

Building a healthy second-language vocabulary involves a range of actions. Things like reading regularly, watching videos, and practising speaking with friends can provide opportunities for incidental vocabulary learning. But students will also benefit from time spent on deliberate learning of new words and phrases.

In this article Matthew Ellman, ELT Trainer at Cambridge University Press, introduces the benefits of using word lists to teach vocabulary. Matthew also provides tips and practical examples to get you started with this teaching and learning tool.

1. Prioritisation

Students need to be able to prioritise which vocabulary they learn. The most frequent words in the language cover most of the words on an average page. So students at the lowest levels should aim to build up a vocabulary of the 3000 most frequent items. Cambridge Dictionary +Plus tags word lists with the level (beginner, intermediate, advanced, native speaker) so students know they are learning the vocabulary that is most useful to them. This helps students to prioritise their vocabulary learning accordingly.

2. Recall

Words need to be recalled from memory to be useful. That’s why quizzes are so helpful when it comes to making new vocabulary sink in. By testing themselves on word lists, learners discover which items on the word list they need to study further. They can see how much progress they’re making and spend valuable study time on the words that really need attention.

3. Multimedia

Pictures and audio provide additional learning support to students. The quizzes in Cambridge Dictionary +Plus include both audio and pictures to help students with vocabulary recall, and to ensure that students recognise not just the written form of new words, but also how they sound.

4. Personalisation

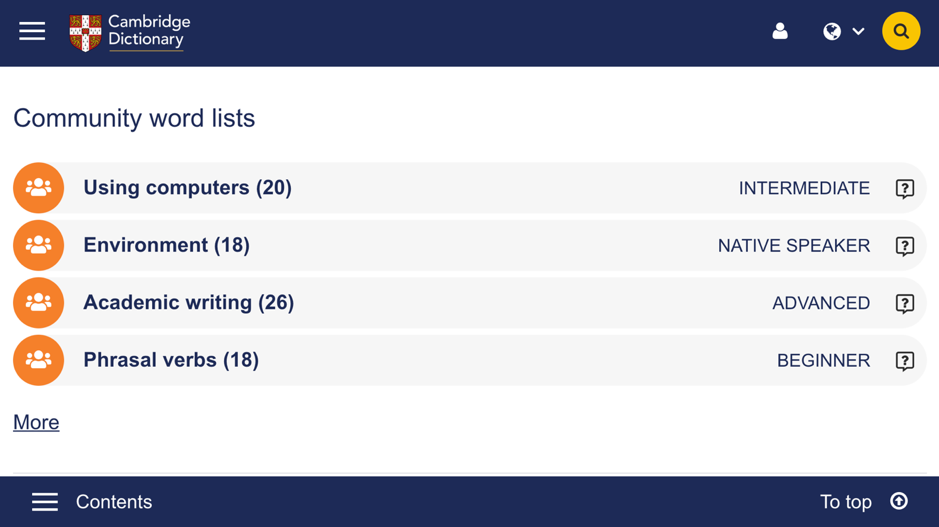

A crucial step towards making new vocabulary stick is for students to relate the words to people, places and things that they know and are important to them. Similarly, students should also work the other way around and learn the words that are most relevant to their lives. Generating new, personalised word lists is an important task, therefore, and Cambridge Dictionary +Plus allows encourages this with community word lists. Other users of Dictionary +Plus mark their own word lists as public to allow others to use them. In this way, students can learn new vocabulary from other students across the globe!

How to use word lists in the classroom

Now that I have established the benefits of learning with word lists, how can you use them in the classroom? Let’s say that your students are doing a reading task in class and you want to find out what vocabulary they are finding difficult. Why not ask your students to make a note of the words they are struggling with from the text as they are reading? Then ask your students to read out one word each and as a class create a Dictionary +Plus word list. As a bite-sized activity you could have a class quiz with your new word list. This will be a quick, interactive and useful vocabulary lesson which will certainly help your learners remember the vocabulary.

Using word lists for revision or homework

Of course, word lists are not only a great learning tool for the classroom. You can set word lists as homework or they can be used by students for revision purposes. Encourage your students to create word lists from tricky vocabulary discovered in the classroom and test themselves at home as part of their homework. They can return to their word lists when studying for in-class tests or larger exams. The word lists will be tailored to the student’s individual pain points and will subsequently be a highly valuable vocabulary resource.

Alternatively, why not create a word list and share the link, or download and print the word list for your students to study at home? For example, if your next lesson will be looking at language used when travelling, share a word list similar to the ‘words about travel’ word list created by us at Cambridge. Your students can look at this vocabulary in their own time to prepare for the following lesson.

A crucial leg up

It’s vital that learners further develop word knowledge, particularly how and when to use new words.

lexical competence must be understood as competence for use rather than just knowledge of word meaning

(Ooi & Kim-Seoh, 1996).

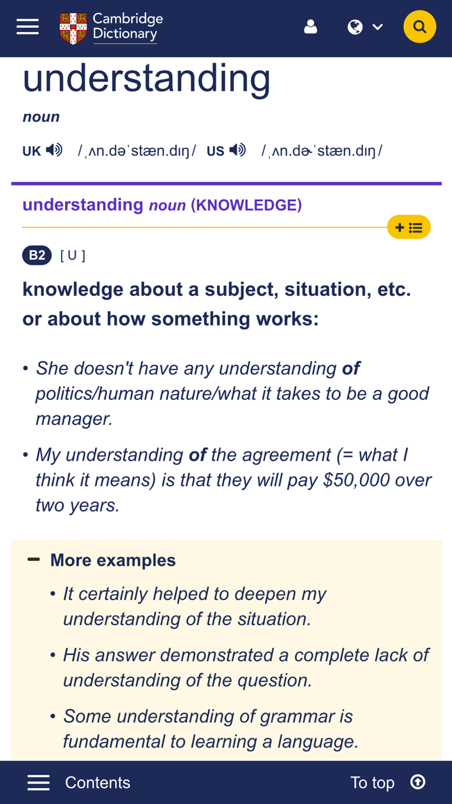

The Cambridge Dictionary word entries include examples of how words are used in context, in addition to their meanings. These examples are taken directly from the Cambridge English corpus and further deepen the learners competence of language for use.

Word lists provide a crucial leg up, helping learners get acquainted with new vocabulary and really cement new words through recognition and use.

Watch this short video to learn more about Cambridge Dictionary +Plus:

<span data-mce-type=”bookmark” style=”display: inline-block; width: 0px; overflow: hidden; line-height: 0;” class=”mce_SELRES_start”></span>

If you enjoyed this article, check out Averil Coxhead’s article about the Focus on vocabulary in speaking in English for Academic Purposes