Personal pronouns are used to refer to people from various perspectives: the first person (I, we), the second person (you), and the third person (she, he, they).

Table of Contents

- The Basics

- «I, Me, and My» in Japanese

- Expressing Identity And Social Context with Personal Pronouns

- Personal Pronouns Are Often Invisible

- First-Person Pronouns («I»)

- Second-Person Pronouns («You»)

- Third-Person Pronouns («He/She»)

- Plural Forms of Personal Pronouns

- Beyond The Basics

- 自分 as a Personal Pronoun

- Ways of Addressing Children

The Basics

Pronouns are words that stand in for other nouns. On this page, we’ll focus on personal pronouns, which are pronouns that refer to people.

Japanese has different types of personal pronouns depending on the point of view they indicate. This is just like English: «I» indicates the first person, «you» the second person, and «she» and «he» the third person.

«I, Me, and My» in Japanese

Grammatically speaking, there’s actually not much to say about Japanese personal pronouns because they’re quite simple! In fact, you can treat them just like other nouns.

For example, 私 is a Japanese first-person pronoun — a personal pronoun you use to talk about yourself. When a person named Jennifer introduces herself, she might say:

- 私はジェニファーです。

- I am Jennifer.

See how 私 is working as «I»? It’s pretty straightforward, and it works just like English. Now, what if Jennifer wants to say «me»?

- 私をジェニーと呼んでください。

- Please call me Jenny.

Just like that. To say both «I» and «me,» we can use the same ol’ 私. So…what about «my»?

- 私のニックネームです。

- It’s my nickname.

It’s still the same 私! The fact that personal pronouns don’t change their form is one of the differences with English personal pronouns. In English, «I» might become «me» and «they» might become «their» depending on their role within the sentence. In Japanese, on the other hand, it’s the job of particles to assign the grammatical role to the noun.

Now let’s go back to the previous examples and see what comes right after 私, to see which particles are assigning 私 its role.

私はジェニファーです。 — «I»

私をジェニーと呼んでください。 — «me»

私のニックネームです。 — «my»

は, を and の are all particles. In the first sentence, は is telling us that 私 is the topic. In the second, を shows us that 私 is the object of the sentence. In the third sentence, の is turning 私 into the possessive form — telling us that the nickname belongs to 私. So when you say «I,» «me,» or even «my,» you use different particles depending on what you want to say, and the first-person pronouns stay exactly as they are.

Expressing Identity And Social Context with Personal Pronouns

Though different from English pronouns in that they don’t change depending on their grammatical role, there are actually many more personal pronouns in Japanese than in English.

If we take the grammatical variations out of the equation, then there’s only one first-person and one second-person pronoun in most varieties of modern English: «I» and «you.» In Japanese, there’s 私, 僕, 俺… and a whole a lot more. And that’s just for first-person pronouns.

Pronoun choice is influenced by different social factors, including self-expression, the relationship between the speaker and the listener, and the formality of the situation. Take a look at these two sentences:

- 私は日本人です。

僕は日本人です。 - I am Japanese.

Both first-person pronouns, 私 and 僕, mean «I.» 私 is more neutral in terms of the gender nuance since it is used commonly, regardless of gender. However, 僕 is generally used by male speakers, or speakers who wish to highlight their masculine identity, or reject traditional feminine identities.

There are many different personal pronouns with different nuances like this. Later on this page, we’ll cover the most common ones! There are also regional and generational differences in personal pronoun uses. We will mainly introduce ones used in the Tokyo area, unless specified as another dialect.

Personal Pronouns Are Often Invisible

Another big difference between English and Japanese is that Japanese sentences manage to function without personal pronouns. This is because, unlike English, Japanese allows you to form sentences without specifying the subject or object. This means that you don’t use personal pronouns in Japanese as much as you do in English. For example, you can even omit the first-person pronoun when you introduce yourself.

- ジェニファーです。

- Jennifer.

Imagine you’re meeting someone for the first time and hear this sentence. Maybe this person is even shaking hands with you. It’s natural to assume that they’re talking about themselves, right? So in this context, what it means is:

- (私は) ジェニファーです。

- (I am) Jennifer.

In the same way, you don’t always say «you» in a sentence either.

- どこの出身ですか?

- Where from?

Suppose this question popped up in a one-on-one conversation, especially in the flow of getting to know each other. It’s obvious that they’re asking about you, even though there’s no mention of you in the sentence.

- (あなたは) どこの出身ですか?

- Where (are you) from?

See how the second-person pronoun あなた is omitted? Unless you’re changing the subject of the discussion, or there’s some other reason personal pronouns are needed for clarity, we often simply leave them out. Another reason behind this frequent omission it that the process of selecting the pronoun can be complicated. The choice is based on various social factors, and the second-person is particularly tricky because you are directly addressing the person for whom you need to select the pronoun. In fact, all Japanese second-person pronouns can be seen as «rude» these days, and it’s common to avoid using them in conversations like the ones above.

First-Person Pronouns («I»)

First-person pronouns are words that a speaker or a writer uses when they refer to themselves. So if you want to talk about yourself, you’d use a first-person pronoun.

- 私はベーコンが好きです。

- I like bacon.

Here’s a quick reference of the most common Japanese first-person pronouns.

| 私 (わたし/わたくし) | わたし expresses femininity when used in casual situations. In formal situations, it is gender-neutral and the most common choice. わたくし is a stiff version of わたし and has an elegant feel. |

| 僕 (ぼく) | 僕 is an earnest, polite pronoun with a somewhat masculine (or rather, boyish) feel, as well as connotations of being cultured. |

| 俺 (おれ) | 俺 is a pronoun with a strong masculine feel, which could sometimes be taken as vulgar. |

| うち | うち has become nationally popular relatively recently, mainly among young female speakers. It carries a feeling of unity. |

There are many more subtleties of nuance that are not covered in this list, and we go over them in more depth on our page about first-person pronouns. Check it out!

Second-Person Pronouns («You»)

Second-person pronouns are personal pronouns that a speaker uses to refer to their listener, and a writer uses to refer to their readers, just like «you» in English.

So if you want to refer to the person you’re talking to, you would use a second-person pronoun.

- あなたはベーコン好きですか?

- Do you like bacon?

Historically, Japanese second-person pronouns have always tended to lose politeness over time. Words that had an honorific feel in the past accumulated a feeling of directness from the moment they started to be used as second-person pronouns. And since being direct is generally considered impolite in Japanese culture, this increase in directness meant a reduction in politeness.

For example, 貴様 is a derogatory second-person pronoun that’s seen as «very rude» nowadays. However, the kanji 貴 (noble) and 様 (honorific title/name ender) show that it used to be a polite way to refer to others. Losing politeness like this is inevitable due to the nature of second-person pronouns, in that they are used to refer directly to the person you’re talking to.

These days, there is no second-person pronoun that is guaranteed to give a respectful impression. That’s why their use is often discouraged in conversation, especially when talking to your teacher or your boss, or other people to whom society expects you to be polite.

So how would you refer to them when you need to? Instead of using second-person pronouns, it’s common to use their names, or social or family roles.

Check out a quick reference of the most common second-person pronouns.

| 貴方 (あなた) | あなた is the standard choice in textbooks, just like 私. It’s a comparatively neutral second-person pronoun, but it can acquire different nuances depending on how it’s used. |

| 君 (きみ) | 君 has a range of nuances. Despite being described as «friendly» in dictionaries, it’s often associated with male supervisors talking to their subordinates, and may sound condescending or snobbish nowadays. Outside of hierarchical places, it expresses a literary or poetic nuance similar to 僕, and is often used in creative writing. |

| お前 (おまえ) | お前 is a second-person pronoun that’s masculine and rough — it’s often used for cussing! 😳 It could also be a way to show affection to close friends, partners, and family in a very casual manner. |

Again, this is a very simplified description of each, so if you’re interested in finding out more, please check out our page about second-person pronouns!

Third-Person Pronouns («He/She»)

Third-person pronouns are words like «he,» «she,» or «they.» They are personal pronouns that refer to someone other than «I» or «you» in conversations or narratives.

- 彼はベーコンが好き。

- He likes bacon.

Here’s a quick reference of the most common third-person pronouns.

| 彼 (かれ)/彼女 (かのじょ) | 彼 means «he» and 彼女 means «she.» However, they are used much less than their English equivalents — especially in conversation — to avoid sounding repetitive. They can also mean «boyfriend» and «girlfriend.» |

| こいつ/そいつ/あいつ | Basically, こいつ means «this person,» そいつ means «that person» and あいつ «that person over there.» They’re very casual words that are sort of like «this guy» or «that dude,» though they don’t indicate a particular gender. |

We talk about these third-persons more in-depth on our page about third-person pronouns. Check it out!

Plural Forms of Personal Pronouns

Now all the basic pronouns are covered, you might be wondering what the plural versions — like «we» and «they» — are? In Japanese, we use suffixes to make nouns plural, rather than having a separate plural form of the noun. To pluralize nouns for people, we commonly use 〜達 (たち), 〜等 (ら), 〜方 (がた) and 〜供 (ども). They all carry different nuances, and particularly levels of formality.

For example, to pluralize 私, which means «I,» you attach a suffix to the end of the pronoun:

私 + 達 = 私達

I + plural suffix = we

Beyond The Basics

自分 as a Personal Pronoun

Although 自分 is considered to be a reflexive pronoun like «oneself,» it is also used as a first-person and a second-person pronoun.

- 自分も、そう思います。

- I think so too.

This is an example of 自分 when it’s used as a first-person pronoun. While often associated with strict hierarchical systems, such those associated with military and sporting environments, it’s more gender-neutral than common first-person pronouns like 私, 俺 and 僕. For that reason, some people in the LGBTQ community prefer to use 自分 in the first person.

- 自分、何してんの?

- What are you doing?

Using 自分 in the second person (referring to your listener) is relatively common in the Kansai dialect. This use carries the nuance of «caring» as if approaching someone while trying to wear their shoes.

Ways of Addressing Children

As it’s all about perspective, personal pronouns are relative to the relationship between the speaker and the listener. In interactions with children, applying their perspective and sticking with it is common in Japanese. This is to help children understand who is being referring to.

For example, say that you’re a mom, and you’re talking to your child:

- ママもお腹すいたよ。

- I am hungry too.

(Literally: Mommy‘s hungry too.)

See how ママ (mom) can be used in the first person? This is similar to English, in which you can also say «Mommy’s hungry too,» right? However, this is not the full extent of it in Japanese. Dads, brothers, sisters, aunties, grandpa, grandma can do this to their little loved ones. And this goes even outside of the family — you can also refer to yourself with your social role.

- 先生の話聞いて。

- Listen to me.

(Literally: Listen to sensei.)

Teachers often refer to themselves as «sensei» when they talk to younger students.

You can address a child using a first-person pronoun to refer to them as well. For example, when talking to a boy who looks lost, you can say:

- 僕、迷子?

- Are you lost?

僕 is a first-person pronoun meaning «I,» but this isn’t someone wondering whether they, themselves, are lost. You can use 僕 to refer to little boys when talking to them directly, because it’s a pronoun they often use to refer to themselves. In the same way, when talking to little girls — especially those whose name you don’t know — you can use 私 to mean «you», as this is the first-person pronoun that girls are commonly taught to use.

- 私、いくつ?

- How old are you?

For reference, the pronouns of the Japanese language, and the posts which talked about them.

- Personal Pronouns

- First Person

- Second Person

- Third Person

- «It»

- Demonstrative Pronouns

- This, That, What

- Here, There, Where

- Plural Pronouns

- Object Pronouns

- Possessive Pronouns

- Personal Pronouns Chart

Personal Pronouns

First Person Pronouns

The following words can be used to say «I» in Japanese:

- watashi 私

- boku 僕

- ore 俺

- ore-sama 俺様 (anime trope, not used seriously.)

The above are the most common, but there are other first pronouns too.

Second Person Pronouns

The following words can be used to say «you» in Japanese:

- anata あなた

- kimi 君

- omae お前

- temee てめぇ

- kisama 貴様

There are immense differences between the words above.

Sometimes kono この means «you» when swearing. See kono yarou この野郎.

Third Person Pronouns

The following word can be used to say «he» in Japanese:

- kare 彼

And this is how you’d say «she» in Japanese:

- kanojo 彼女

Besides the above, the pronoun aitsu あいつ is sometimes used with a meaning similar to «he.»

The following demonstrating pronouns mean «this person,» «that person,» but can be understood as «me,» «you,» «»he,» or «she» depending on context.

- kono hito, sono hito, ano hito このひと, そのひと, あのひと

- kono ko, sono ko, ano ko この子, その子, あの子

- kocchi, socchi, acchi こっち, そっち, あっち

- kochira, sochira, achira こちら, そちら, あちら

- konata, sonata, anata こなた, そなた, あなた

- This anata means «he» and it’s archaic.

- The modern anata means «you» instead.

«It»

There’s no Japanese equivalent for the pronoun «it.» See the article «It» in Japanese for examples of how the functions of «it» in English translate to Japanese.

Demonstrative Pronouns

This, that, here, there, etc. in Japanese are expressed through the kosoado kotoba.

This, That, What

To say the nouns «this,» «that,» and «what» in Japanese:

- kore これ

- sore それ

- are あれ

- dore どれ

To say the adjectives «this,» «that,» and «what» in Japanese:

- kono この

- sono その

- ano あの

- dono どの

There are certain Japanese words like kou こう, konna こんあ, kochira こちら, and others. that also mean «this,» «that,» and «what,» each with a different nuance. See kosoado kotoba for details.

Here, There, Where

To say «this,» «there,» and «where» in Japanese:

- koko ここ

- soko そこ

- asoko あそこ

- doko どこ

Plural Pronouns

In Japanese, plurals don’t work the same way they do in English. In particular, Japanese has the so-called pluralizing suffixes tachi たち and ra ら, which can be combined with pronouns to form plural pronouns.

To say «we» in Japanese:

- watashitachi 私たち

- bokura 僕ら, bokutachi 僕達

- orera 俺ら, oretachi 俺達

To say «they» in Japanese:

- karera 彼ら

They. (he and the others) - kanojotachi 彼女たち

They. (she and the others)

To say «these» and «those» in Japanese:

- korera これら

- sorera それら

Object Pronouns

There are no words for «me,» «us,» «him,» «her,» and «them» in Japanese. There’s no distinction between subject pronouns and object pronouns in Japanese.

The only difference is in the usage of particles. This has been explained in simple sentences in Japanese. For example:

- watashi ga kare wo koroshita 私が彼を殺した

I killed him. - kare ga watashi wo koroshita 彼が私を殺した

He killed me.

Possessive Pronouns

There are no words for «my,» «his,» «her,» «their» in Japanese. There are no words for «mine,» «hers,» and «theirs» either.

Instead, the no の particle is used together with a pronoun to express what it possesses. For example:

- ore no kane 俺の金

My money. - anata no yume あなたの夢

Your dream. - kare no nozomi 彼の望み

His wish. - kanojotachi no kimochi

彼女たちの気持ち

Their feelings.

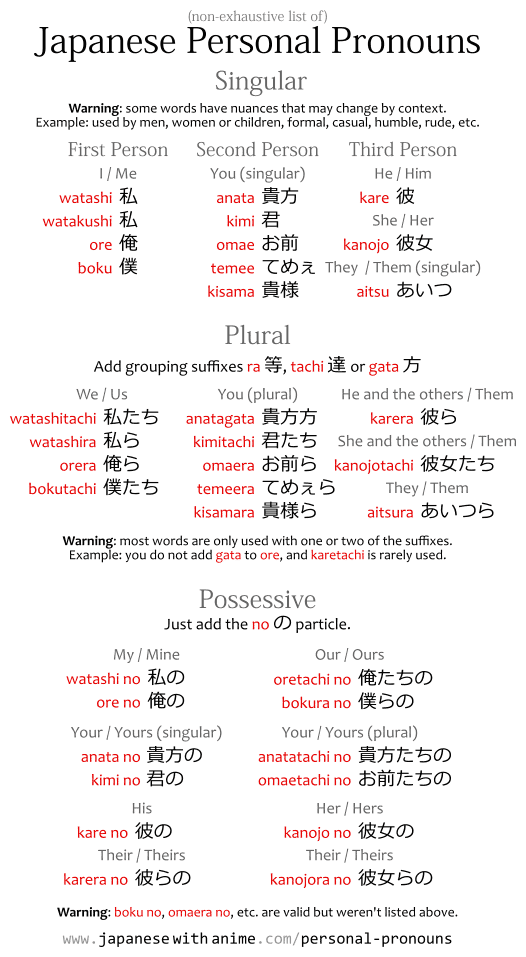

Personal Pronouns Chart

For reference, a chart with the personal pronouns:

Hello. I’m Kosuke!

Today, let’s learn how to say «he» and «she» in Japanese!

1. Summary

Basically, «he» and «she» are «かれ(kare)» and «かのじょ(kanojo)» in Japanese.

| English | Japanese | Romaji | Kanji |

|---|---|---|---|

| he | かれ | ka re | 彼 |

| she | かのじょ | ka no jo | 彼女 |

However, «かれ(kare)» and «かのじょ(kanojo)» also have the meaning «boyfriend» and «girlfriend» in Japanese.

Let’s check how to use «かれ(kare)» and «かのじょ(kanojo)» from this article!

As you can see from the table above, «かれ(kare)» means «he», and «かのじょ(kanojo)» means «she».

In English, «he» sometimes changes its form to «his» and «him».

Also, «she» sometimes becomes «her».

As we learned in the past article, regarding «I, my, me, and mine», in Japanese, we use particles with the pronouns.

| English | Japanese | Romaji | Kanji |

|---|---|---|---|

| he | かれ(は) | ka re (wa) | 彼(は) |

| his | かれの | ka re no | 彼の |

| him | かれを (かれに) |

ka re wo (ka re ni) |

彼を (彼に) |

| English | Japanese | Romaji | Kanji |

|---|---|---|---|

| she | かのじょ(は) | ka no jo (wa) | 彼女(は) |

| her (possessive case) |

かのじょの | ka no jo no | 彼女の |

| her (objective case) |

かのじょを (かのじょに) |

ka no jo wo (ka no jo ni) |

彼女を (彼女に) |

If you don’t know the particle «は(wa)», please check this:

If you don’t know the particle «の(no)», please check this:

If you don’t know the particle «を(wo)», please check this:

These particles can be used generally.

So once you remember them, you can use them for every noun in Japanese.

Let’s check example sentences for «kare» and «kanojo»!

Examples:

かれは あかるいです。

ka re wa a ka ru i de su

Meaning: «He is cheerful.»

If you don’t know the adjective «あかるい(akarui)», please check this:

かのじょは せがたかいです。

ka no jo wa se ga ta ka i de su

Meaning: «She is tall.»

If you don’t know how to say «tall» in Japanese, please check this:

かれの なまえは さすけです。

ka re no na ma e wa sa su ke de su

Meaning: «His name is Sasuke.»

なまえ: name

If you want to know how to introduce your name in Japanese, please check this:

かのじょの りょうりは おいしいです。

ka no jo no ryo u ri wa o i shi i de su

Meaning: «Her cooking is delicious.»

りょうり: cooking, dish, food, cuisine

If you want to know how to say «delicious» in Japanese, please check this:

かのじょは かれを たたいた。

ka no jo wa ka re wo ta ta i ta

Meaning: «She hit him.»

たたいた: hit (past tense)

ひとびとは かのじょを くのいちと よんだ。

hi to bi to wa ka no jo wo ku no i chi to yo n da

Meaning: «People called her Kunoichi.»

ひとびと: people

くのいち: Kunoichi (woman ninja)

よんだ: called

Like the examples above, please use «かれ(kare)» and «かのじょ(kanojo)» with particles, depending on the context.

In Japanese, «かれ(kare)» and «かのじょ(kanojo)» have the meaning of «boyfriend» and «girlfriend».

With this usage, sometimes we say «かれし(kareshi)» instead of «かれ(kare)».

Let’s check the examples!

Examples:

わたしの かれは つめたい。

wa ta shi no ka re wa tsu me ta i

Meaning: «My boyfriend is cold-hearted.»

If you want to know more about «つめたい(tsumetai)», please check this:

Like the example above, «かれ(kare)» can mean «boyfriend».

わたしの かれしは つめたい。

wa ta shi no ka re shi wa tsu me ta i

Meaning: «My boyfriend is cold-hearted.»

Like the example above, «かれ(kare)» and «かれし(kareshi)» have the same meaning.

かのじょは ねている。

ka no jo wa ne te i ru

Meaning: «My girlfriend is sleeping.»

ねている: is sleeping

If you want to know how to say «sleep» in Japanese, please check this:

Regarding this example, you can translate to «She is sleeping» instead of «My girlfriend is sleeping».

There is no way to know whether this «kanojo» is «she» or «girlfriend».

You need to judge it based on context.

«Kareshi» only has the meaning of «boyfriend».

So you can know the meaning without thinking about the context.

However, if «kare» is used, you need to judge the meaning from the context.

«He» is «kare» in Japanese!

«She» is «kanojo» in Japanese!

| English | Japanese | Romaji | Kanji |

|---|---|---|---|

| he | かれ | ka re | 彼 |

| she | かのじょ | ka no jo | 彼女 |

These words are used with Japanese particles!

«Kare» can also mean «boyfriend»!

«Kanojo» can also mean «girlfriend»!

I hope this article helps you to study Japanese!

Please enjoy studying Japanese!

She couldn’t talk to us anymore.

母が私達に語ることはもうないのだ。

こいつセルキーなんだ。ママと同じなんだ。

She was still not able to receive

Our Lord in Holy Communion.

それは御聖体の主イエズス様をまだいただけなかったことです。

She had been a bright, easygoing girl.

もともとは明るくのんびりした女の子でした。

She and the kids and her husband bobby.

娘と子供達娘の夫のボビーが。

And remember— she can’t swim.

She‘s an alumni from her high school dance club.

She is lured into threesome by his parents.

She‘s back home and she’s feeling better.

もう家に帰ってて具合も良くなってる。

What souvenir do you think she would like most?

She has higher demands for her dress.

She knows what she deserves.

She thanked himle agradeció.

カイシーホテル3*。

Oh, she in her late 30s? She a bad lil’.

Ohあいつ30代後半なのか?悪い女だな。

She is a little baby-faced girl with a body to die for.

彼女がのために死ぬために身体に少し童顔女の子です。

She is retiring at 30 years old and after a 6-year career.

彼女はで引退されます30歳と6年のキャリアの後。

She is to have CT examination

and blood test once in a month.

その後も一ヶ月に一度のCTと血液検査。

She is so energetic for traveling all over the world.

歳を超えても世界中を旅して回るエネルギーに驚かされました。

She is the name to know the birds related words.

幼い子供のようだった。

Pay attention to what she asks you about.

She thought, that she was happy.

She could not comprehend any question put to her.

She made me promise… transparency, teamwork.

Results: 167636,

Time: 0.0183

English

—

Japanese

Japanese

—

English

Japanese pronouns are words in the Japanese language used to address or refer to present people or things, where present means people or things that can be pointed at. The position of things (far away, nearby) and their role in the current interaction (goods, addresser, addressee, bystander) are features of the meaning of those words. The use of pronouns, especially when referring to oneself and speaking in the first person, vary between gender, formality, dialect and region where Japanese is spoken.

Use and etymologyEdit

In contrast to present people and things, absent people and things can be referred to by naming; for example, by instantiating a class, «the house» (in a context where there is only one house) and presenting things in relation to the present, named and sui generis people or things can be «I’m going home», «I’m going to Hayao’s place», «I’m going to the mayor’s place», «I’m going to my mother’s place» or «I’m going to my mother’s friend’s place». Functionally, deictic classifiers not only indicate that the referenced person or thing has a spatial position or an interactional role but also classify it to some extent. In addition, Japanese pronouns are restricted by a situation type (register): who is talking to whom about what and through which medium (spoken or written, staged or in private). In that sense, when a male is talking to his male friends, the pronoun set that is available to him is different from those available when a man of the same age talks to his wife and, vice versa, when a woman talks to her husband. These variations in pronoun availability are determined by the register.

In linguistics, generativists and other structuralists suggest that the Japanese language does not have pronouns as such, since, unlike pronouns in most other languages that have them, these words are syntactically and morphologically identical to nouns.[1][2] As functionalists point out, however, these words function as personal references, demonstratives, and reflexives, just as pronouns do in other languages.[3][4]

Japanese has a large number of pronouns, differing in use by formality, gender, age, and relative social status of speaker and audience. Further, pronouns are an open class, with existing nouns being used as new pronouns with some frequency. This is ongoing; a recent example is jibun (自分, self), which is now used by some young men as a casual first-person pronoun.

Pronouns are used less frequently in the Japanese language than in many other languages,[5] mainly because there is no grammatical requirement to include the subject in a sentence. That means that pronouns can seldom be translated from English to Japanese on a one-to-one basis.

The common English personal pronouns, such as «I», «you», and «they», have no other meanings or connotations. However, most Japanese personal pronouns do. Consider for example two words corresponding to the English pronoun «I»: 私 (watashi) also means «private» or «personal». 僕 (boku) carries a masculine impression; it is typically used by males, especially those in their youth.[6]

Japanese words that refer to other people are part of the encompassing system of honorific speech and should be understood within that context. Pronoun choice depends on the speaker’s social status (as compared to the listener’s) as well as the sentence’s subjects and objects.

The first-person pronouns (e.g., watashi, 私) and second-person pronouns (e.g., anata, 貴方) are used in formal contexts (however the latter can be considered rude). In many sentences, pronouns that mean «I» and «you» are omitted in Japanese when the meaning is still clear.[3]

When it is required to state the topic of the sentence for clarity, the particle wa (は) is used, but it is not required when the topic can be inferred from context. Also, there are frequently used verbs that imply the subject and/or indirect object of the sentence in certain contexts: kureru (くれる) means «give» in the sense that «somebody other than me gives something to me or to somebody very close to me.» Ageru (あげる) also means «give», but in the sense that «someone gives something to someone other than me.» This often makes pronouns unnecessary, as they can be inferred from context.

In Japanese, a speaker may only directly express their own emotions, as they cannot know the true mental state of anyone else. Thus, in sentences comprising a single adjective (often those ending in -shii), it is often assumed that the speaker is the subject. For example, the adjective sabishii (寂しい) can represent a complete sentence that means «I am lonely.» When speaking of another person’s feelings or emotions, sabishisō (寂しそう) «seems lonely» would be used instead. Similarly, neko ga hoshii (猫が欲しい) «I want a cat,» as opposed to neko wo hoshigatte iru (猫を欲しがっている) «seems to want a cat,» when referring to others.[7] Thus, the first-person pronoun is usually not used unless the speaker wants to put a special stress on the fact that they are referring to themselves or if it is necessary to make it clear.

In some contexts, it may be considered uncouth to refer to the listener (second person) by a pronoun. If it is required to state the second person, the listener’s surname, suffixed with -san or some other title (like «customer», «teacher», or «boss»), is generally used.

Gender differences in spoken Japanese also create another challenge, as men and women refer to themselves with different pronouns. Social standing also determines how people refer to themselves, as well as how they refer to other people.

Japanese first-person pronouns by speakers and situations according to Yuko Saegusa, Concerning the First Personal Pronoun of Native Japanese Speakers (2009)

| Speaker | Situation | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | To friends | uchi 49% | First name 26% | atashi 15% |

| In the family | First name 33% | atashi 29% | uchi 23% | |

| In a class | watashi 86% | atashi 7% | uchi 6% | |

| To an unknown visitor | watashi 75% | atashi, first name, uchi 8% each | ||

| To the class teacher | watashi 66% | First name 13% | atashi 9% | |

| Male | To friends | ore 72% | boku 19% | First name 4% |

| In the family | ore 62% | boku 23% | uchi 6% | |

| In a class | boku 85% | ore 13% | First name, nickname 1% each | |

| To an unknown visitor | boku 64% | ore 26% | First name 4% | |

| To the class teacher | boku 67% | ore 27% | First name 3% |

| Speaker | Situation | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | To friends | uchi 39% | atashi 30% | watashi 22% |

| In the family | atashi 28% | First name 27% | uchi 18% | |

| In a class | watashi 89% | atashi 7% | jibun 3% | |

| To an unknown visitor | watashi 81% | atashi 10% | jibun 6% | |

| To the class teacher | watashi 77% | atashi 17% | jibun 7% | |

| Male | To friends | ore 87% | uchi 4% | watashi, jibun 2% each |

| In the family | ore 88% | boku, jibun 5% each | ||

| In a class | watashi 48% | jibun 28% | boku 22% | |

| To an unknown visitor | boku 36% | jibun 29% | watashi 22% | |

| To the class teacher | jibun 38% | boku 29% | watashi 22% |

List of Japanese personal pronounsEdit

The list is incomplete, as there are numerous Japanese pronoun forms, which vary by region and dialect. This is a list of the most commonly used forms. «It» has no direct equivalent in Japanese[3] (though in some contexts the demonstrative pronoun それ (sore) is translatable as «it»). Also, Japanese does not generally inflect by case, so, I is equivalent to me.

| Romaji | Hiragana | Kanji | Level of speech | Gender | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – I/me – | |||||

| watashi | わたし | 私 | formal/informal | both | In formal or polite contexts, this is gender neutral; in casual speech, it is typically only used by women. Use by men in casual contexts may be perceived as stiff. |

| watakushi | わたくし | 私 | very formal | both | The most formal personal pronoun. Outdated curriculums did not provide for any other kind of pronoun in everyday speech for foreigners, except for watakushi.[8] However, in modern student books, such a pronoun has been withdrawn from use.[9] |

| ware | われ | 我, 吾 | very formal | both | Used in literary style writing. Also used as rude second person in western dialects. |

| waga | わが | 我が | very formal | both | Means «my» or «our». Used in speeches and formalities; 我が社 waga-sha (our company) or 我が国 waga-kuni (our country). |

| ore | おれ | 俺 | informal | males | Frequently used by men.[10] Establishes a sense of «masculinity». Can be seen as rude depending on the context. Emphasises one’s own status when used with peers and with those who are younger or of lesser status. Among close friends or family, its use conveys familiarity rather than «masculinity» or superiority. It was used also by women until the late Edo period and still is in some dialects. Also oi in Kyushu dialect. |

| boku | ぼく | 僕 | formal/informal | males | Used by males of all ages; very often used by boys; can be used by females but then carries tomboyish or feminist connotations. Perceived as humble, but can also carry an undertone of «feeling young» when used by males of older age. Also used when casually giving deference; «servant» uses the same kanji (僕 shimobe). Can also be used as a second-person pronoun toward male children (English equivalent – «kid» or «squirt»). |

| washi | わし | 儂 | formal/informal | mainly males | Often used in western dialects and fictional settings to stereotypically represent characters of old age. Also wai, a slang version of washi in the Kansai dialect. |

| jibun | じぶん | 自分 | neutral | mainly males | Literally «oneself»; used as either reflexive or personal pronoun. Can convey a sense of distance when used in the latter way. Also used as casual second person pronoun in the Kansai dialect. |

| ore-sama | おれさま | 俺様 | informal | mainly (fictional) males | «My esteemed self», «Mr. I». Used in fiction by very self-important or arrogant characters,[11] or humorously. |

| atai | あたい | 私 | very informal | females | Slang version of あたし atashi.[12] |

| atashi | あたし | 私 | informal | females (but see notes) | A feminine pronoun that strains from わたし («watashi»). Rarely used in written language, but common in conversation, especially among younger women. It was formerly used by male members of the merchant and artisan classes in the Edo area and continues to be used by male rakugo performers. |

| atakushi | あたくし | 私 | informal | females | A feminine pronoun that strains from わたくし («watakushi»). |

| uchi | うち | 家, 内 | informal | mostly females | Means «one’s own». Often used in western dialects especially the Kansai dialect. Generally written in kana. Plural form uchi-ra is used by both genders. Singular form is also used by both sexes when talking about the household, e.g., «uchi no neko» («my/our cat»), «uchi no chichi-oya» («my father»); also used in less formal business speech to mean «our company», e.g., «uchi wa sandai no rekkāsha ga aru» («we (our company) have three tow-trucks»). |

| (own name) | informal | both | Used by small children and young women; considered cute and childish. | ||

| oira | おいら | 俺等, 己等 | informal | males | Similar to 俺 ore, but more casual. Evokes a person with a rural background, a «country bumpkin». |

| ora | おら | 俺等 | informal | both | Dialect in Kanto and further north. Similar to おいら oira, but more rural. Also ura in some dialects. |

| wate | わて | informal | all | Dated Kansai dialect. Also ate (somewhat feminine). | |

| shōsei | しょうせい | 小生 | formal, written | males | Used among academic colleagues. Lit. «your pupil».[13] |

| – you (singular) – | |||||

| (name and honorific) | formality depends on the honorific used | both | |||

| anata | あなた | 貴方, 貴男, 貴女 | formal/informal | both | The kanji are very rarely used. The only second person pronoun comparable to English «you», yet still not used as often in this universal way by native speakers, as it can be considered having a condescending undertone, especially towards superiors.[3][10][better source needed] For expressing «you» in formal contexts, using the person’s name with an honorific is more typical. More commonly, anata may be used when having no information about the addressed person; also often used as «you» in commercials, when not referring to a particular person. Furthermore, commonly used by women to address their husband or lover, in a way roughly equivalent to the English «dear». |

| anta | あんた | 貴方 | informal | both | Contraction of あなた anata.[12] Can express contempt, anger or familiarity towards a person. Generally seen as rude or uneducated when used in formal contexts. |

| otaku | おたく | お宅, 御宅 | formal, polite | both | A polite way of saying «your house», also used as a pronoun to address a person with slight sense of distance. Otaku/otakki/ota turned into a slang term referring to a type of geek/obsessive hobbyist, as they often addressed each other as otaku. |

| omae | おまえ | お前 | very informal | both | Similar to anta, but used by men with more frequency.[10] Expresses the speaker’s higher status or age, or a very casual relationship among peers. Often used with おれ ore.[10] Very rude if said to elders. Commonly used by men to address their wife or lover, paralleling the female use of «anata». |

| temē, temae | てめえ, てまえ |

手前 | rude and confrontational[12] | mainly males | Literal meaning «the one in front of my hand». Temē, a reduction of temae, is more rude. Used when the speaker is very angry. Originally used for a humble first person. The Kanji are seldom used with this meaning, as unrelated to its use as a pronoun, 手前 can also mean «before», «this side», «one’s standpoint» or «one’s appearance». |

| kisama | きさま | 貴様 | extremely hostile and rude | mainly males | Historically very formal, but has developed in an ironic sense to show the speaker’s extreme hostility / outrage towards the addressee. |

| kimi | きみ | 君 | informal | both | The kanji means «lord» (archaic) and is also used to write -kun.[14] Informal to subordinates; can also be affectionate; formerly very polite. Among peers typically used with 僕 boku.[10] Often seen as rude or assuming when used with superiors, elders or strangers.[10] |

| kika | きか | 貴下 | informal, to a younger person | both | |

| kikan | きかん | 貴官 | very formal, used to address government officials, military personnel, etc. | both | |

| on-sha | おんしゃ | 御社 | formal, used to the listener representing your company | both | Only used in spoken language. |

| ki-sha | きしゃ | 貴社 | formal, similar to onsha | both | Only used in written language as opposed to onsha. |

| – he / she – | |||||

| ano kata | あのかた | あの方 | very formal | both | Sometimes pronounced ano hou, but with the same kanji. 方 means «direction,» and is more formal by avoiding referring to the actual person in question. |

| ano hito | あのひと | あの人 | neutral | both | Literally «that person». |

| yatsu | やつ | 奴 | informal | both | A thing (very informal), dude, guy. |

| koitsu, koyatsu | こいつ, こやつ | 此奴 | very informal, implies contempt | both | Denotes a person or material nearby the speaker. Analogous to «he/she» or «this one». |

| soitsu, soyatsu | そいつ, そやつ | 其奴 | very informal, implies contempt | both | Denotes a person or material nearby the listener. Analogous to «he/she» or «that one». |

| aitsu, ayatsu | あいつ, あやつ | 彼奴 | very informal, implies contempt | both | Denotes a person or (less frequently) material far from both the speaker and the listener. Analogous to «he/she» or «that one». |

| – he – | |||||

| kare | かれ | 彼 | formal (neutral) and informal (boyfriend) | both | Can also mean «boyfriend». Formerly 彼氏 kareshi was its equivalent, but this now always means «boyfriend».[citation needed] Literally meaning «that one», in classical Japanese it could mean «he», «she», or «it».[15] |

| – she – | |||||

| kanojo | かのじょ | 彼女 | formal (neutral) and informal (girlfriend) | both | Originally created in the 19th century as an equivalent to female pronouns in European languages. Initially pronounced kano onna, it literally means «that female».[16] Can also mean «girlfriend».[17] |

| – we (see also list of pluralising suffixes, below) – | |||||

| ware-ware | われわれ | 我々 | formal | both | Mostly used when speaking on behalf of a company or group. |

| ware-ra | われら | 我等 | informal | both | Used in literary style. ware is never used with -tachi. |

| hei-sha | へいしゃ | 弊社 | formal and humble | both | Used when representing one’s own company. From a Sino-Japanese word meaning «low company» or «humble company». |

| waga-sha | わがしゃ | 我が社 | formal | both | Used when representing one’s own company. |

| – they (see also list of pluralising suffixes, below) – | |||||

| kare-ra | かれら | 彼等 | common in spoken Japanese and writing | both |

Archaic personal pronounsEdit

| Romaji | Hiragana | Kanji | Meaning | Level of speech | Gender | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| asshi | あっし | 私 | I | males | Slang version of watashi. From the Edo period. | |

| sessha | せっしゃ | 拙者 | I | males | Used by samurai during the feudal ages (and often also by ninja in fictionalised portrayals). From a Sino-Japanese word meaning «one who is clumsy». | |

| wagahai | わがはい | 我が輩, 吾輩 | I | males | Literally «my fellows; my class; my cohort», but used in a somewhat pompous manner as a first-person singular pronoun. | |

| soregashi | それがし | 某 | I | males | Literally «So-and-so», a nameless expression. Similar to sessha. | |

| warawa | わらわ | 妾 | I | females | Literally «child». Mainly used by women in samurai families. Today, it is used in fictional settings to represent archaic noble female characters. | |

| wachiki | わちき | I | females | Used by geisha and oiran in Edo period. Also あちき achiki and わっち wacchi. | ||

| yo | よ | 余, 予 | I | males | Archaic first-person singular pronoun. | |

| chin | ちん | 朕 | We | both | Used only by the Emperor, mostly before World War II. | |

| maro | まろ | 麻呂, 麿 | I | males | Used as a universal first-person pronoun in ancient times. Today, it is used in fictional settings to represent Court noble male characters. | |

| onore | おのれ | 己 | I or you | males | The word onore, as well as the kanji used to transcribe it, literally means «oneself». It is humble when used as a first person pronoun and hostile (on the level of てめえ temee or てまえ temae) when used as a second person pronoun. | |

| kei | けい | 卿 | you | males | Second person pronoun, used mostly by males. Used among peers to denote light respect, and by a superior addressing his subjects and retainers in a familiar manner. Like 君 kimi, this can also be used as an honorific (pronounced as きょう kyou), in which case it’s equivalent to «lord/lady» or «sir/dame». | |

| nanji | なんじ | 汝, less commonly also 爾 | you, often translated as «thou» | both | Spelled as なむち namuchi in the most ancient texts and later as なんち nanchi or なんぢ nanji. | |

| onushi | おぬし | 御主, お主 | you | both | Used by elders and samurai to talk to people of equal or lower rank. Literally means «master». | |

| sonata | そなた | 其方 (rarely used) | you | both | Originally a mesial deictic pronoun meaning «that side; that way; that direction»; used as a lightly respectful second person pronoun in previous eras, but now used when speaking to an inferior in a pompous and old-fashioned tone. | |

| sochi | そち | 其方 (rarely used) | you | both | Similar to そなた sonata. Literally means «that way». (Sochira and kochira, sometimes shortened to sotchi and kotchi, are still sometimes used to mean roughly «you» and «I, we», e.g. kochira koso in response to thanks or an apology means literally «this side is the one» but idiomatically «no, I (or we) thank/apologise to you»; especially common on the telephone, analogous to phrases like «on this end» and «on your end» in English. Kochira koso is often translated as «me/us, too» or «likewise» – it is certainly a reciprocation gesture, but sometimes a little more.) |

SuffixesEdit

Suffixes are added to pronouns to make them plural.

| Romaji | Hiragana | Kanji | Level of speech | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tachi | たち | 達 | informal; examples:

|

Also can be attached to names to indicate that person and the group they are with (Ryuichi-tachi = «Ryuichi and friends»). |

| kata, gata |

かた, がた |

方 | formal (ex. あなた方, anata-gata) | More polite than 達 tachi. gata is the rendaku form. |

| domo | ども | 共 | humble (ex. 私ども, watakushi-domo) | Casts some aspersion on the mentioned group, so it can be rude. domo is the rendaku form. |

| ra | ら | 等 | informal (ex. 彼ら, karera. 俺ら, ore-ra. 奴ら, yatsu-ra. あいつら, aitsu-ra) | Used with informal pronouns. Frequently used with hostile words. Sometimes used for light humble as domo (ex. 私ら, watashi-ra). |

Demonstrative and interrogative pronounsEdit

Demonstrative words, whether functioning as pronouns, adjectives or adverbs, fall into four groups. Words beginning with ko- indicate something close to the speaker (so-called proximal demonstratives). Those beginning with so- indicate separation from the speaker or closeness to the listener (medial), while those beginning with a- indicate greater distance (distal). Interrogative words, used in questions, begin with do-.[3]

Demonstratives are normally written in hiragana.

| Romaji | Hiragana | Kanji | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| kore | これ | 此れ | this thing / these things (near speaker) |

| sore | それ | 其れ | that thing / those things (near listener) |

| are | あれ | 彼れ | that thing / those things (distant from both speaker and listener) |

| dore | どれ | 何れ | which thing(s)? |

| kochira or kotchi | こちら / こっち | 此方 | this / here (near speaker) |

| sochira or sotchi | そちら / そっち | 其方 | that / there (near listener) |

| achira or atchi | あちら / あっち | 彼方 | that / there (distant from both speaker and listener) |

| dochira or dotchi | どちら / どっち | 何方 | what / where |

For more forms, see Japanese demonstratives on Wiktionary.

Other interrogative pronouns include 何 なに nani «what?» and 誰 だれ dare «who(m)?».

ReflexiveEdit

Japanese has only one word corresponding to reflexive pronouns such as myself, yourself, or themselves in English. The word 自分 (jibun) means «one’s self» and may be used for human beings or some animals. It is not used for cold-blooded animals or inanimate objects.[3][better source needed]

See alsoEdit

- Gender differences in spoken Japanese

- Japanese honorifics

ReferencesEdit

- ^ Noguchi, Tohru (1997). «Two types of pronouns and variable binding». Language. 73 (4): 770–797. doi:10.1353/lan.1997.0021. S2CID 143722779.

- ^ Kanaya, Takehiro (2002). 日本語に主語はいらない Nihongo ni shugo wa iranai [In Japanese subjects are not needed]. Kodansha.

- ^ a b c d e f Akiyama, Nobuo; Akiyama, Carol (2002). Japanese Grammar. Barron’s Educational. ISBN 0764120611.

- ^ Ishiyama, Osamu (2008). Diachronic Perspectives on Personal Pronouns in Japanese (Ph.D.). State University of New York at Buffalo.

- ^ Maynard, Senko K: «An Introduction to Japanese Grammar and Communication Strategies», page 45. The Japan Times, 4th edition, 1993. ISBN 4-7890-0542-9

- ^ «The many ways to say «I» in Japanese | nihonshock». nihonshock.com. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ Hatasa, Yukiko Abe; Hatasa, Kazumi; Makino, Seiichi (2014). Nakama 1: Japanese Communication Culture Context. Cengage Learning. p. 314. ISBN 9781285981451.

- ^ Nechaeva L.T. «Japanese for beginners», 2001, publishing house «Moscow Lyceum», ISBN 5-7611-0291-9

- ^ Maidonova S.V. «Complete Japanese course», 2009, Publishing house «Astrel», ISBN 978-5-17-100807-9

- ^ a b c d e f 8.1. Pronouns Archived 22 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine sf.airnet.ne.jp Retrieved on October 21, 2007

- ^ Maynard, Senko K. (2016). Fluid orality in the discourse of Japanese popular culture. Amsterdam. p. 226. ISBN 978-90-272-6713-9. OCLC 944246641.

- ^ a b c Personal pronouns in Japanese Japan Reference. Retrieved on October 21, 2007

- ^ «Language Log » Japanese first person pronouns». languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu.

- ^ «old boy». Kanjidict.com. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ Haruo Shirane (2005) Classical Japanese: A Grammar. Columbia University Press. p. 256

- ^ «彼女とは».

- ^ «he». Kanjidict.com. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

External linksEdit

- Japan Reference: Personal pronouns in Japanese

- sci.lang.japan FAQ: Japanese pronouns

Personal pronouns do exist in Japanese, although their use is quite different from English. Native Japanese speakers choose pronouns according to the context, their gender and age, but also to whom they are addressing: the person’s gender, age and social status, with a wide range of politeness levels.

If the context is clear, personal pronoun is usually omitted. They are however necessary to communicate in Japanese language, or to understand speech nuances when watching movies, dramas or anime. We will introduce the most commonly used and the most useful personal pronouns for beginners.

I: Watashi

You will avoid many mistakes and quid pro quos in using watashi (私) to talk about yourself regardless of the situation, your gender or your age.

A more formal version is watakushi (私), favored by politicians. It can be altered in atashi when used by (very young) women.

Elderly people sometimes say washi (儂) or ware (我).

Some pronouns are customarily used by men only:

- Boku (僕) is favored by boys and younger men, but grown men can also say it to express a form of modesty;

- Ore (俺) is used among a group of peers, and / or by lower social status men. If followed by -sama (様), an honorific suffix, it shows a strong ego and marks a great impoliteness.

If you watch historical movies or dramas, you might have heard sessha (拙者), widely used by samurai characters.

In any case, if you are unsure on how to translate «I», just say «watashi.» Depending on the situation, the other translations can be perceived as strange, inappropriate or even very rude.

You: Anata

In Japanese language classes, the term anata (あなた, or more informal an’ta あんた; the kanji 貴方 are seldom used nowadays) is often introduced as the Japanese «you.» However, its use can be tricky as:

- It means «darling» in the context of a couple;

- If used alone to call out someone, it can be rude.

You should use anata only if you don’t know the name of the person you are talking to. The best way to address another person is to preferably say their name (or first name if you are friends) followed by the honorific suffix -san instead of «anata.» For example, for «mister Tanaka,» you will say Tanaka-san’ (田中さん). Using the other person’s social position or occupation is also appropriate: If Mister Tanaka is a doctor, you can call him Tanaka-sensei (田中先生), if he is an athlete competing for the Olympic Games 🏅 you can call him Tanaka-senshu (田中選手, «champion» Tanaka).

The honorific suffixes don’t mark gender, so you can use them for a man as well as for a woman. Thus Tanaka-san’ can also mean «Miss» or «Madame Tanaka.»

From less formal to vulgar, «you» can also be translated as:

- Kimi (きみ, seldom 君), usually when addressing young people;

- Omae (おまえ);

- Temee (てめえ, from 手前 / てまえ temae).

He / She: Kare /Kanojo

When talking about another person, you can use the pronouns kare (彼) for boys and men, and kanojo (彼女) for girls and women.

Bear in mind, however, that these pronouns are often used to talk about one’s boyfriend or girlfriend!

A more polite way of speaking consists in using konohito (この人), literally «this person.» The part corresponding to «this» can vary according to the physical and / or social distance between you and the person you are talking about (sono その, for an intermediate distance, and ano あの for a further distance). The kanji can be replaced by 方 kata which is a very formal way of talking. Hito and kata can be used for men as well as for women.

Saying their name followed by an honorific suffix is also totally appropriate.

We: Watashi-tachi

Simply add tatchi (達) after the personal pronoun for «I» to create the plural form:

- Watashi-tatchi (私たち);

- Atashi-tatchi (あたし達);

- Boku-tatchi (僕たち); and,

- Ore-tatchi (俺たち).

Note that ware becomes ware-ware (我々). It is also possible to say bokura (僕ら).

You (plural): Anata-tatchi

In the same way as»we,» just add tatchi (達) to anata to create the plural form:

- Anata-tatchi (あなた達), or an’ta-tatchi (あんた達);

- Kimi-tatchi (きみ達); and,

- Omae-tatchi (おまえ達).

If you are referring to a group of persons, and that you know at least one of them, you can use their name. For example, «Mister Tanaka & co» can be translated Tanaka-san-tatchi (田中さんたち).

They: Kare-tatchi / Kanojo-tatchi

It is the same construction as «we» and «you»: kare-tatchi (彼達) and kanojo-tatchi (彼女達).

There is also karera (彼ら) for «them» designating men.

To learn more on this topic: an article from Nikkei provides a comprehensive table of the personal pronouns that have been or are still in use in Japanese language. Many are not in use anymore, such as: warawa, soregashi or maro.

Most of Japanese people don’t expect foreigners to speak or understand Japanese, but if you want to try communicating in Miyazaki’s language make sure to carefully choose your words to impress them in a good way!

- Words

- Sentences

Definition of she

- (pn, adj-no) he; she; that person

- you

-

(pn, adj-no) that gentleman (lady); he; she

あの方たちに大変うれしいです。

I am very pleased to meet them.

- (n) this way; here

- the person in question; he; she; him; her

- since (a time in the past); prior to (a time in the future)

- (pn, adj-no) me

- you

-

(n) companion; other party (side); he; she; they

先方が電話にお出になりました。

Your party is on the line. - destination

- person in front

-

(n) servant (esp. a samurai’s attendant)

「あいつはいい奴だ」と皆が異口同音に言う。

He’s a nice guy — that’s unanimous. - chivalrous man (c. Edo period)

- cubed tofu (often served cold)

- kite shaped like a footman

- Edo-period hairstyle worn by samurai’s attendants

- enslavement (of a woman; Edo-period punishment for her own or her husband’s crime)

- (pn) he; she; him; her

- (pn, adj-no) fellow; guy; chap

- thing; object

- (derogatory or familiar) he; she; him; her

- (n) the said person; he; she; same person

- (pn) she; her

-

(adj-no) her

それは彼女のですね。

It is hers, is it not? -

girl friend; girlfriend; sweetheart

僕の彼女はカナダへいってしまった。

My girlfriend has gone to Canada.

-

(pn, adj-no) he; she; that guy

あいつが僕のことを「ばかなやつ」っていったんだよ。

He called me a stupid boy.

- (pn) (derogatory or familiar) he; she; him; her

- (n) samurai’s attendant (in a var. of origami)

- type of popular song accompanied by dance from the Edo period

- (n) fellow; guy; chap

- he; him; she; her

Words related to she

Sentences containing she

Pronouns in the Japanese language are used less frequently than they would be in many other languages, mainly because there is no grammatical requirement to explicitly mention the subject in a sentence. So, pronouns can seldom be translated from English to Japanese on a one-on-one basis.

Most of the Japanese pronouns are not pure: they have other meanings. In English the common pronouns have no other meaning: for example, «I», «you», and «they» have no use except as pronouns. But in Japanese the words used as pronouns have other meanings: for example, 私 means «private» or «personal»; 僕 means «manservant».

The words Japanese speakers use to refer to other people are part of the more encompassing system of Japanese honorifics and should be understood within that frame. The choice of pronoun will depend on the speaker’s social status compared to the listener, the subject, and the objects of the statement.

The first person pronouns (e.g. watashi, 私) and second person pronouns (e.g. anata, 貴方) are used in formal situations. In many sentences, when an English speaker would use the pronouns «I» and «you», they are omitted in Japanese. Personal pronouns can be left out when it is clear who the speaker is talking about.

When it is required to state the topic of the sentence for clarity, the particle wa (は) is used, but it is not required when the topic can be inferred from context. Also, there are frequently used verbs that can indicate the subject of the sentence in certain circumstances: for example, kureru (くれる) means «give», but in the sense of «somebody gives something to me or somebody very close to me»; while ageru (あげる) also means «give», but in the sense of «someone gives something to someone (usually not me)». Sentences consisting of a single adjective (often those ending in -shii) are often assumed to have the speaker as the subject. For example, the adjective sabishii can represent a complete sentence meaning «I am lonely.»

Thus, the first person pronoun is usually only used when the speaker wants to put a special stress on the fact that they are referring to themself, or if it is necessary to make it clear. In some situations it can be considered uncouth to refer to the listener (second person) by a pronoun. If it is required to state the second person explicitly, the listener’s surname suffixed with -san or some other title (like «customer», «teacher», or «boss») is generally used.

Gender differences in spoken Japanese also bring about another challenge as men and women use different pronouns to refer to themselves. Social standing also determines how a person refers to themselves, as well as how a person refers to the person they are talking to.

List of Japanese pronouns[]

The following list is incomplete. There are numerous such pronoun forms that exist in Japanese, which vary by region, dialect, and so forth. This is a list of the most commonly used forms. «It» has no direct equivalent in Japanese.Note that Japanese doesn’t generally inflect by case, so, e.g., I is equivalent to me but not myself.

| Romaji | Hiragana | Kanji | Level of speech | Gender | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| — Me — | ||||||

| watashi | わたし | 私 | formal, informal (Women) | both | Derived in the 18th century from the first person pronoun 私 (watakushi).

Most common first person pronoun, used by both genders in every occasion that requires politeness but it’s used in more casual contexts by women. |

|

| watakushi | わたくし | 私

厶 (archaic variant) |

very formal | both | The most formal polite version of I, me.

Used in extremely formal settings where high respect and politeness is required. Originally was read as «し» using the kanji 厶 and was just used in its On’yomi form. It had the same meaning as the modern chinese word, «Private» (opposite of 公, public), and still is when read in its old form, some words use it like 私費 (しひ) «Private money«. It appeared first to refer to indivuals (as shortened sense of «private individual») in the written style (as in Chinese) during the Muromachi period. From the Edo period, the word changed to refer to one’s personal things, to one’s own thoughts to finally refer to oneself. Eventually, it slowly replaced 我 (ware). Possible compound of the pronoun 我 (わ, i, me) with the word 宅 (たくHousehold) and the «厶» (し Private) adjective to possibly mean «one’s household». While it’s almost certain that the ‘wa’ in watakusi comes from 我 (wa; i,me), it was a term formerly considered humbling and initially used by women |

|

| Ware | われ (あ,あれ、わ) |

|

very formal | mostly males. | One of the oldest pronouns from old japanese, polite and rigid, very old fashioned.

It uses the same kanji as for Chinese «I, me», wo. It used to be read as «Wa»,»A» and «Are», until the Heian period when it just became «Ware». It comes from the ancient japanese pronoun 我 (WA, i,us) and the suffix れ (re, humbling) It was the most common first person pronoun until the Edo period, where it was slowly phased out by «Watashi». Today its use as first person pronoun in conversations is extremely rare, restricted to literal writing (古文) where it’s the most common first person pronoun, old songs, quotes, poetry and fiction. In fiction, characters using Ware are gods, kings and immortal beings of great importance and power. The 吾 writing of «ware», although has the same meaning and reading, it’s more archaic and literal, 我 is more common and is used instead. There was distintion in the reading of 吾 and 我, in the ancient history, 我 corresponded to ‘WA’ while 吾 corresponded to ‘A’, both ancient pronouns that stopped being used in the Kamakura and Heian periods respectively, however, the 吾 kanji remained in use in the form of わが (wa-ga, my/our), and it seems that 吾 was most often paired with verbs and it established a personal connection with the verb (so to indicate something that afflicts the person), while 我 was used as well to indicate ‘WA-GA’, it was used with nouns only, and established a formal but still affectionate connection with the noun (so to indicate that the noun used with is something that the speaker is familiar with), this difference in usage, comes from the obsolete ancient japanese pronoun ‘あが (A-GA, my), that could also mean ‘I’ as あ (吾) indicated that a person had an informal and personal connection with the noun verb, in expressions like あがきみ (my lord or ‘my dear you’). The plural forms (我々、我等) are used normally. |

|

| Wa-ga | わが | 我が、吾が | Very formal and old fashioned, somewhat boastful. | Mostly males. | Means «my» or «our» .

It uses the reading of the Old Japanese first person pronoun «Wa» (I, me) and the «ga» particle that was the old possessive particle in old japanese. It’s comparable to the modern ”私の” or «私達の”. Today used in speeches, short statements and formalities, however, since the expression is literary, the expression wa-ga is used only in fixed phrases and expressions with the most common examples being:

Expressions like 我が本 (my book) are not used unless it’s in a fictional character that fits the role of a incantation or demon lord that uses the pronoun 我 (われ)instead of 私. |

|

| Aga | あが | 吾が | literary, formely humble and polite | both | It means «my», variant of «Wa-ga» , literal and archaic.

It indicated a personal and informal connection with the noun or verb the speaker refers to, it could also mean ‘I’. It went in disuse during the medieval era, where it was replaced by «Ware/Wa-ga» (我). It’s still used in literal style (古文), in expressions such as

|

|

| ore | おれ | 俺 | informal | exclusively males | Meaning «I, me», Almost exclusively used by men.

One of the oldest pronouns in japanese still being used. Originally, like in Chinese,俺 was a second person pronoun, similar in use like 爾 (Namuti) that was similarly used to refer to lessers. From the Kamakura period, 俺 started to be used as a first person pronoun in the west japan. It was freely used by both genders with no class restriction until the Edo Period, when it started to fall from women’s speech and became exclusive to men. It can be seen as rude depending on the situation. Establishes a sense of masculinity. Used with peers or those younger or of lesser status, indicating one’s own status. Among close friends or family, its usage is a sign of familiarity rather than masculinity or superiority. |

|

| Ore-sama | おれさま | 俺様 | very pompous and rude | pompous and arrogant males | It means «I, me».

It’s a very pompous and arrogant first person pronoun, combining the masculine pronoun 俺 (I,me) and the polite suffix 様 (most respectable). Literally it would mean «Most respectable me/ My magnificent self». Its usage is restricted in fiction, where it’s used by very arrogant, narcissistic and overly confident male characters. The only time it’s used in real life is as self-mocking joke. Used intentionally it would be extremely unpolite and pompous. |

|

| boku | ぼく | 僕 | informal and humble | males and rarely females (boyish) | Also meaning «I». Used in giving a sense of casual deference, uses the same kanji for servant (僕, shimobe), especially a male one, from a Sino-Japanese word. | |

| washi | わし | 儂,私 | informal | old males | Western japanese dialect variant of «Watashi», commonly used in Kansai and Kyouto by the elderly.

Originally very common in the 18th century used by women to refer to their friends or in informal contexts. Eventually it was used by both genders of Kansai. It’s becoming old fashioned, now it’s commonly used in fictitious creations to stereotypically represent old male characters. |

|

| atai | あたい | 私 | very informal | females | Kansai slang of あたし atashi. | |

| atashi | あたし | 私 | informal | females | Often considered cute. Rarely used in written language, but common in conversation, especially among younger women. | |

| atakushi | あたくし | 私 | formal | females | This pronoun is rare, and usually its use is in fiction by snobby/upperclass women. | |

| uchi | うち | 家 | informal | mostly young girls | Means one’s own. Often used in the Kansai and Kyūshū dialects. Uses the same kanji for house (家, uchi). | |

| (own name) | informal | mostly children and young girls | Used by small children and young girls, considered cute. | |||

| oira | おいら | 俺 | informal | both | Slang version of «Ore». May give off sense of more country bumpkin. | |

| ora | おら | 俺 | informal | both | Dialect in Kanto and further north. Gives off sense of country bumpkin. Used among children influenced by main characters in Dragon Ball and Crayon Shin-chan. | |

| — You — | ||||||

| anata | あなた | 貴方, 貴男, 貴女 | formal/informal | both | Literal translation of «you»

The kanji is rarely used. It is not used as much, since, when speaking to someone directly, the name of the addressee is better. When not knowing the name of the person or a stranger, it’s better to omit pronouns. Originally it meant «that direction, that place over there», from older 彼方(Kanata, that direction). |

Commonly used by women to address their husband or lover, in a way roughly equivalent to the English «dear». |

| anta | あんた | informal | both | Slang version of «anata». Slightly more rude and informal. Often expresses anger or contempt towards a person. Generally seen as rude or uneducated. | ||

| otaku | おたく | お宅, 御宅 | formal, polite | both | Polite form of saying «your house», also used as a pronoun to address a person with slight sense of distance but polite. Otaku/Otakku/Otaki/Otakki turned into a slang referring to some type of Otaku/geek/obsessive hobbyist, as they often addressed each other as Otaku. | |

| omae | おまえ

おまへ (historical) |

御前

お前 |

very informal, historically polite. | mainly males. | Extremely informal pronoun, almost exclusively used by men, normally used by higher social class or status to lesser peers. It’s rough and sometimes degoratory, especially when used towards elders, teachers or in situations that require politeness and respect. Often used with おれ ore. In case of using it between close friends or a lover, it carries familiarity and closeness.

Historically it was a polite term to address others, it still carries its old meaning in shrines under the reading ごぜん or おんまえ. It literally means «the honorable one in front of me» |

|

| Temae | てまえ | 手前 | rude and derogatory | mainly males. | Extremely informal and derogatory, unlike Omae, Temae is used to deliberately be rude and insulting to someone.

Historically it was a normal pronoun to address someone in a group. It literally means «The one in front of my hand». |

|

| Temee | てめえ | rude and confrontational | mainly males | Temee, a version of temae that is more rude. Used when the speaker is very angry and carries a tone of hostility. | ||

| kisama | きさま | 貴様 | extremely hostile and rude.

Very polite and formal (formerly) |

mainly males. | Second person pronoun,»You».

It literally means «Most respectable and worthy of respect individual», it was comparable to a modern ”貴方様» Historically, similar to Omae, before the Edo period (1600 CE-1850 CE) it was a very formal and polite pronoun to address superiors and nobles or individuals that required great respect and politeness. It slowly devolved to a common pronoun to refer to others with respect, to a generic pronoun to finally a very disrespectful pronoun used nowadays just in fights and between enemies or to just insult. The original meaning of the word has been twisted in ironizing and insulting the listener’s honor and reputation, resulting in an extremely hostile and insulting pronoun. |

|

| kimi | きみ | 君 | informal | both | Informal pronoun to address others of lower status, it carries familiarity and can also be affectionate; formerly very polite.

It’s used in romantic songs or to love interests/proposals. Rude when used with superiors, elders or strangers. The kanji means lord (archaic) and it’s the same kanji for the honorific —kun. |

|

| kika | きか | 貴下 | informal, to a younger person | both | Informal you, used in older japanese to politely address a subordinate, now used by older men to younger subjects.

It literally means «the respectable one that is below (me)» |

|

| on-sha | おんしゃ | 御社 | formal, used to the listener representing your company | both | It means «Respectable company» , used in business settings by a person addressing one’s company in a polite manner. | |

| ki-sha | きしゃ | 貴社 | formal, similar to «onsha» | both | It means «Most honorable company» that is used in more polite and formal settings to address another’s company. | |

| — He / She — | ||||||

| ano kata | あのかた | あの方 | very formal | both | It means «That individual» (human being) in a honorific and polite manner. | |

| ano hito | あのひと | あの人 | formal/informal | both | Literally «that person». | |

| yatsu | やつ | 奴 | informal | both | An informal way to address other males, sometimes it’s derogatory. | |

| koitsu | こいつ | 此奴 | very informal, implies contempt | both | Denotes a person or material nearby the speaker. Analogous to «this one». | |

| soitsu | そいつ | 其奴 | very informal, implies contempt | both | Denotes a person or material nearby the listener. Analogous to «he/she», «it» or «this/that one». | |

| aitsu | あいつ | 彼奴 | very informal, implies contempt | both | Denotes a person or (less frequently) material far from both the speaker and the listener. Analogous to «he/she» or «that one». | |

| — He — | ||||||

| kare | かれ | 彼 | formal (neutral) and informal (boyfriend) | both | It’s the literal translation of «He».

It can also mean boyfriend. Formerly 彼氏 kareshi was its equivalent but now always means boyfriend. Kare in Old Japanese, was the demonstrative pronoun instead of あれ which was a first person pronoun. |

|

| — She — | ||||||

| kanojo | かのじょ | 彼女 | formal (neutral) and informal (girlfriend) | both | Literal translation of «she».

It can also mean girlfriend. |

|

| — We — | ||||||

| hei-sha | へいしゃ | 弊社 | formal and humble | both | Used when representing one’s own company. From a Sino-Japanese word meaning «low company» or «humble company». | |

| waga-sha | わがしゃ | 我が社 | Formal and polite, somewhat grand and old fashioned. | both | It means «my company», used by a CEO to give a speech in a formal and rigid tone.

It comes from the archaic Old Japanese first person pronoun, «Wa» (我、i, me) and the old japanese possessive particle, Ga(が). |

|

| — They — | ||||||

| kare-ra | かれら | 彼等 | common in spoken Japanese and writing | both | It means «They» in a informal tone. | |

| — Notable Others — | ||||||

| Ware-Ware | われわれ | 我々 | Very Formal | mostly males | It uses the old japanese first person pronoun, «Ware».

It is used when speaking on behalf of a company or group. It’s very old fashioned and rigid, used in extremely formal occasions. It can be compared to an old fashioned version of «Watakushi». |

|

| Ware-ra | われ・ら | 我等 吾等 | Very formal | Mostly males | It means «We», but in an old fashioned and formal tone. It can be used in formal business settings as alternative to watakushi. |

| Romaji | Hiragana | Kanji | Meaning | Level of speech | Gender | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| — Archaic Pronouns — | ||||||

| A | あ | 吾

安(man’yōgana) 阿 (man’yōgana) |

i, me | informal | both | First person pronoun from Proto-japanese and used in Old Japanese.

It was used until the Heian period, when it was replaced by Ware. It’s still used in literary style and fictional settings. It may have come from the usage of 阿 in chinese, that was a prefix attached to people’s names and things, to indicate familiarity and closeness. After the Heian period, it was only used in the fossilized form of あが (my) |

| Are | あれ | 吾

安礼 (man’yōgana) 阿例 (man’yōgana) |

i,me | informal | both | First person pronoun from Proto-japanese, long form of «A» (I,me).

It was used until the Heian period, when it was replaced by Ware. Later it became a demonstrative pronoun (that) replacing Kare. It’s still used in literary style as pronoun and fictional settings. Its fusion with ‘WARE’ may have depended on the pronuncation of the ‘P to W row sound change’, a phenomen in which the ‘P’ row of hiragana (today H) shifted pronuncation first to ‘PH’, then to ‘B’ then to ‘W’, this pronuncation change affected the vowels (even ‘A’) as they came to be pronounced different as well, like お became ‘WO’ until the 11th century, when the sound ‘WO’ dissapeared, and あれ became just ‘WARE’ |

| Wa | わ |

(man’yōgana) |

we (ancient)

i,me |

formal | First person pronoun from Proto-japanese, short form of 我 (ware i,me).

In the Nara period was used as plural pronoun or sometimes reflexively. It’s still used in its fossilized form of «wa-ga» (My, our) in extremely formal settings. It’s still used as pronoun in literary style and fictional settings. |

|

| Na | な | 汝 | you | informal | Archaic second person pronoun from proto-japanese, short form of nare (you, なれ)

It fell from use in Heian period. Sometimes it was used as reflexive first person pronoun. See Onore 己 |

|

| Nare | なれ | 汝

奈礼 (man’yōgana) |

you | informal | Archaic second person pronoun from proto-japanese, long form of na (you, な)

It fell from use in Heian period, replaced by nanji. It had the same usage of お前 today. |

|

| I | い | 汝 | you | informal and archaic. | males | Archaic second person pronoun from Old japanese, that was used to those lesser in social scale or age.

Short form of «Imashi». Comparable to modern お前. Sometimes derogatory. |

| mashi | まし | 汝 | you | informal | Archaic second person pronoun from Old japanese, that was used to those lesser in social scale or age.

Sometimes derogatory. |

|

| Imashi | いまし | 汝 | you | informal | males | Archaic second person pronoun, that was used to those lesser in social scale or age but it’s slightly more polite.

Evolution of «i» (you) and «mashi» (you). |

| Mimashi | みまし | 汝 | you | formal | both | Archaic second person pronoun, most formal and polite form of «I» (You) used in medieval era.

Comparable to 貴方 (you, formal). |

| Unu | うぬ | 己

汝 |

you (derogatory)

myself (humble) |

informal | both | Ancient slang of Proto-japanese おの (Myself, Oneself).

It was mainly used as second person pronoun to those equal or lesser. It was used as insulting and rude pronoun to call others. Rarely, it was used as reflexive and humble first person pronoun (see 己, onore) It can use the plurazing 等 (-ra) |

| asshi | あっし | 私 | I | informal | males | Slang form of Watashi (i,me) rarely used in regional dialects by artisans in Kansai. |

| sessha | せっしゃ | 拙者 | I | Polite and humble. | males | Humble first person pronoun, Used by samurais during the feudal ages. Its meaning is «Clumsy one».

Used nowadays in literal writing, and in fiction it stereotypically represents ninjas and samurai characters. |

| waga-hai | わがはい | 我が輩,吾輩 | I,me | Formal, Arrogant | mostly males | Formal, archaic and highly pompous first person pronoun, it carries a tone of arrogance and egotistical.

Literally «my fellows; my class; my cohort». Its most famous use is in the novel «I am a cat, 吾輩は猫である。» emphatizing a cat’s own pride. Similar to 俺様, but more archaic. It comes from a classic chinese «We, us» pronoun that was adopted by japanese nobles and lords as a way to emphatize their social status over others. |

| soregashi | それがし | 某 | I,me | humble and polite | both | Ancient first person pronoun, used by Samurai until the Edo period.

It means «Unknown person». It was first humble and polite, but it became a rude pronoun. |

| nanigashi | なにがし | 某

何某 |

me, myself | humble and polite | both | Old first person pronoun, used by samurai.

It means «(Who’s that) unknown person». It was at first a humbling and polite first person pronoun, that over time became rough and rude and became archaic around the late 1800’s. |

| Warawa | わらわ | 妾 | I | humble | women | Ancient first person singular pronoun, used historically by women, wives and daughters of a Samurai.

It is humble and polite. The kanji is the old female archaic kanji for «Child» and corresponds to «Concubine» today. |

| yo | よ | 余, 予 | I | pompous and formal. | males | Archaic first-person singular pronoun, quite pompous and old fashioned. It was used by nobles and lords.

It first appeared as first person pronoun in the Heian Period, as equivalent to 吾 (ware) used regardless of status, gender or age. It was used by nobles, scholars and high ranking samurai until the Meiji Period. In fiction is used by kingly characters. Its modern use is quite limited, but can be used in the expression «余は満足じゃ(I am most pleased!)» as joke. |

| chin | ちん | 朕 | I | Formal and royal. | males | Used only by the emperor, mostly before World War II.

The kanji comes from Chinese, that was adopted by the japanese emperor as his exclusive first person pronoun and was passed down as tradition until 1946. |

| maro | まろ | 麻呂麿 | I, me | formal and old fashioned | Males | Extremely old and archaic first person pronoun, used from Heian period, as equivalent to 我 and 吾.