Want to know all about the words Shakespeare invented? We’ve got you covered.

In all of his works – the plays, the sonnets and the narrative poems – Shakespeare uses 17,677 different words.

How Many Words Did Shakespeare Invent?

Across all of his written works, it’s estimated that words invented by Shakespeare number as many as 1,700. We say these are words invented by Shakespeare , though in reality many of these 1,700 words would likely have been in common use during the Elizabethan and Jacobean era, just not written down prior to Shakespeare using them in his plays, sonnets and poems. In these cases Shakespeare would have been the first known person to document these words in writing.

Historian Jonathan Hope also points out that Victorian scholars who read texts for the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary read Shakespeare’s texts more thoroughly than most, and cited him more often, meaning Shakespeare is often credited with the first use of words which can be found in other writers.

Examples Of Commonly Used Words Shakespeare Created

It is Shakespeare who is credited with creating the below list of words that we still use in our daily speech – some of them frequently.

accommodation

aerial

amazement

apostrophe

assassination

auspicious

baseless

bloody

bump

castigate

changeful

clangor

control (noun)

countless

courtship

critic

critical

dexterously

dishearten

dislocate

dwindle

eventful

exposure

fitful

frugal

generous

gloomy

gnarled

hurry

impartial

inauspicious

indistinguishable

invulnerable

lapse

laughable

lonely

majestic

misplaced

monumental

multitudinous

obscene

palmy

perusal

pious

premeditated

radiance

reliance

road

sanctimonious

seamy

sportive

submerge

suspicious

Along with these everyday words invented by Shakespeare, he also created a number of words in his plays that never quite caught on in the same way… Shakespearean words like ‘Armgaunt’, ‘Eftes’, ‘Impeticos’, ‘Insisture’, ‘Pajock’, ‘Pioned’ ‘Ribaudred’ and ‘Wappened’. We do have some ideas as to what these words may mean, though much is guesswork. Watch the video below for more insight into words Shakespeare invented that have been lost in the mists of time:

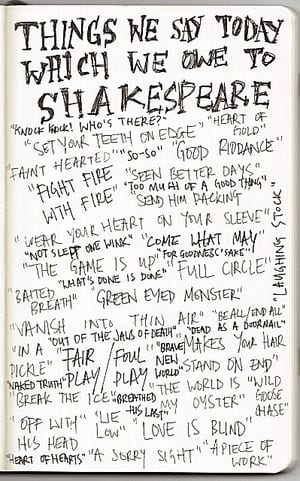

And it wasn’t just words that Shakespeare created, documented, or brought into common usage – he also put words together and created a host of new phrases. Read all about the phrases that Shakespeare invented here. And see our complete Shakespeare dictionary, which lists hundreds of commonly used Shakespeare’s words that arent; so common today, along with a simple definition.

Shakespeare words – see handwritten phrases and words Shakespeare invented

William Shakespeare used more than 20,000 words in his plays and poems, and his works provide the first recorded use of over 1,700 words in the English language. It is believed that he may have invented or introduced many of these words himself, often by combining words, changing nouns into verbs, adding prefixes or suffixes, and so on. Some words stuck around and some didn’t.

Although lexicographers are continually discovering new origins and earliest usages of words, below are listed words and definitions we still use today that are widely attributed to Shakespeare.

Shakespeare’s Words A-Z

Alligator: (n) a large, carnivorous reptile closely related to the crocodile

Romeo and Juliet, Act 5 Scene 1

Bedroom: (n) a room for sleeping; furnished with a bed

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act 2 Scene 2

Critic: (n) one who judges merit or expresses a reasoned opinion

Love’s Labour’s Lost, Act 3 Scene 1

Downstairs: (adv) on a lower floor; down the steps

Henry IV Part 1, Act 2 Scene 4

Eyeball: (n) the round part of the eye; organ for vision

Henry VI Part 1, Act 4 Scene 7

Fashionable: (adj) stylish; characteristic of a particular period

Troilus and Cressida, Act 3 Scene 3

Gossip: (v) to talk casually, usually about others

The Comedy of Errors, Act 5 Scene 1

Hurry: (v) to act or move quickly

The Comedy of Errors, Act 5 Scene 1

Inaudible: (adj) not heard; unable to be heard

All’s Well That Ends Well, Act 5 Scene 3

Jaded: (adj) worn out; bored or past feeling

Henry VI Part 2, Act 4 Scene 1

Kissing: (ppl adj) touching with the lips; exchanging kisses

Love’s Labour’s Lost, Act 5 Scene 2

Lonely: (adj) feeling sad due to lack of companionship

Coriolanus, Act 4 Scene 1

Manager: (n) one who controls or administers; person in charge

Love’s Labour’s Lost, Act 1 Scene 2

Nervy: (adj) sinewy or strong; bold; easily agitated

Coriolanus, Act 2 Scene 1

Obscene: (adj) repulsive or disgusting; offensive to one’s morality

Love’s Labour’s Lost, Act 1 Scene 1

Puppy dog: (n) a young, domestic dog

King John, Act 2 Scene 1

Questioning: (n) the act of inquiring or interrogating

As You Like It, Act 5 Scene 4

Rant: (v) to speak at length in inflated or extravagant language

Hamlet, Act 5 Scene 1

Skim milk: (n) milk with its cream removed

Henry IV Part 1, Act 2 Scene 3

Traditional: (adj) conventional; long-established, bound by tradition

Richard III, Act 3 Scene 1

Undress: (v) to remove clothes or other covering

The Taming of the Shrew, Induction Scene 2

Varied: (adj) incorporating different types or kinds; diverse

Titus Andronicus, Act 3 Scene 1

Worthless: (adj) having no value or merit; contemptible

The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Act 4 Scene 2

Xantippe: (n) shrewish wife of Socrates; figuratively, a bad-tempered woman

The Taming of the Shrew, Act 1 Scene 2

Yelping: (adj) uttering sharp, high-pitched cries

Henry VI Part 1, Act 4 Scene 2

Zany: (n) clown’s assistant; performer who mimics another’s antics

Love’s Labour’s Lost, Act 5 Scene 2

Inventors get a lot of love. Thomas Edison is held up as a tinkering genius. Steve Jobs is considered a saint in Silicon Valley. Hedy Lamar, meanwhile, may have been a Hollywood star but a new book makes clear her real legacy is in inventing the foundations of encryption. But while all these people invented things, it’s possible to invent something even more fundamental. Take Shakespeare: he invented words. And he invented more words—words that continue to shape the English language—than anyone else. By a long shot.

But what does it mean to “invent” words? How many words did Shakespeare invent? What kind of words? And which words are those exactly? Rather than just listing all the words Shakespeare invented, this post digs deeper into the how and the why (or “wherefore”) of Shakespeare’s literary creations.

How Many Words Did Shakespeare Invent?

1700! My, what a perfectly round number! Such a large and perfectly round number is misleading at best, and is more likely just wrong—there is in fact a bunch of debate about the accuracy of this number.

So who’s to blame for the uncertainty around the number of words Shakespeare invented? For starters, we can blame the Oxford English Dictionary. This famous dictionary (often called the OED for short) is famous, in part, because it provides incredibly thorough definitions of words, but also because it identifies the first time each word actually appeared in written English. Shakespeare appears as the first documented user of more words than any other writer, making it convenient to assume that he was the creator of all of those words.

In reality, though, many of these words were probably part of everyday discourse in Elizabethan England. So it’s highly likely that Shakespeare didn’t invent all of these words; he just produced the first preserved record of some of them. Ryan Buda, a writer at Letterpile, explains it like this:

But most likely, the word was in use for some time before it is seen in the writings of Shakespeare. The fact that the word first appears there does not necessarily mean that he made it up himself, but rather, he could have borrowed it from his peers or from conversations he had with others.

However, while Shakespeare might have been just the first person to write down some words, he definitely did create many words himself, plenty of which we still use to this day. The list a ways down below contains the 420 words that almost certainly originated from Shakespeare himself.

But all this leads to another question. What does it even mean to “invent” a word?

How Did Shakespeare Invent Words?

Some writers invent words in the same way Thomas Edison invented light bulbs: they cobble together bits of sound and create entirely new words without any meaning or relation to existing words. Lewis Carroll does in the first stanza of his “Jabberwocky” poem:

`Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

Carroll totally made up words like “brillig,” “slithy,” “toves,” and “mimsy”; the first stanza alone contains 11 of these made-up words, which are known as nonce words. Words like these aren’t just meaningless, they’re also disposable, intended to be used just once.

Shakespeare did not create nonce words. He took an entirely different approach. When he invented words, he did it by working with existing words and altering them in new ways. More specifically, he would create new words by:

- Conjoining two words

- Changing verbs into adjectives

- Changing nouns into verbs

- Adding prefixes to words

- Adding suffixes to words

The most exhaustive take on Shakespeare’s invented words comes from a nice little 874-page book entitled The Shakespeare Key by Charles and Mary Cowden Clarke. Here’s how they explain Shakespeare’s literary innovations:

Shakespeare, with the right and might of a true poet, and with his peculiar royal privilege as king of all poets, has minted several words that deserve to become current in our language. He coined them for his own special use to express his own special meanings in his own special passages; but they are so expressive and so well framed to be exponents of certain particulars in meanings common to us all, that they deserve to become generally adopted and used.

We can call what Shakespeare did to create new words “minting,” “coining” or “inventing.” Whatever term we use to describe it, Shakespeare was doing things with words that no one had ever thought to do before, and that’s what matters.

Shakespeare Didn’t Invent Nonsense Words

Though today readers often need the help of modern English translations to fully grasp the nuance and meaning of Shakespeare’s language, Shakespeare’s contemporary audience would have had a much easier go of it. Why? Two main reasons.

First, Shakespeare was part of a movement in English literature that introduced more prose into plays. (Earlier plays were written primarily in rhyming verse.) Shakespeare’s prose was similar to the style and cadence of everyday conversation in Elizabethan England, making it natural for members of his audience to understand.

In addition, the words he created were comprehensible intuitively because, once again, they were often built on the foundations of already existing words, and were not just unintelligible combinations of sound. Take “congreeted” for example. The prefix “con” means with, and “greet” means to receive or acknowledge someone.

It therefore wasn’t a huge stretch for people to understand this line:

That, face to face and royal eye to eye.

You have congreeted.(Henry V, Act 5, Scene 2)

Shakespeare also made nouns into verbs. He was the first person to use friend as a verb, predating Mark Zuckerberg by about 395 years.

And what so poor a man as Hamlet is

May do, to express his love and friending to you(Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 5)

Other times, despite his proclivity for making compound words, Shakespeare reached into his vast Latin vocabulary for loanwords.

His heart fracted and corroborate.

(Henry V, Act 2, Scene 1)

Here the Latin word fractus means “broken.” Take away the –us and add in the English suffix –ed, and a new English word is born.

New Words Are Nothing New

Shakespeare certainly wasn’t the first person to make up words. It’s actually entirely commonplace for new words to enter a language. We’re adding new words and terms to our “official” dictionaries every year. In the past few years, the Merriam-Webster dictionary has added several new words and phrases, like these:

- bokeh

- elderflower

- fast fashion

- first world problem

- ginger

- microaggression

- mumblecore

- pareidolia

- ping

- safe space

- wayback

- wayback machine

- woo-woo

So inventing words wasn’t something unique to Shakespeare or Elizabethan England. It’s still going on all the time.

But Shakespeare Invented a Lot of New Words

So why did Shakespeare have to make up hundreds of new words? For starters, English was smaller in Shakespeare’s time. The language contained many fewer words, and not enough for a literary genius like Shakespeare. How many words? No one can be sure. One estimates, one from Encyclopedia Americana, puts the number at 50,000-60,000, likely not including medical and scientific terms.

During Shakespeare’s time, the number of words in the language began to grow. Edmund Weiner, deputy chief editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, explains it this way:

The vocabulary of English expanded greatly during the early modern period. Writers were well aware of this and argued about it. Some were in favour of loanwords to express new concepts, especially from Latin. Others advocated the use of existing English words, or new compounds of them, for this purpose. Others advocated the revival of obsolete words and the adoption of regional dialect.

In Shakespeare’s collected writings, he used a total of 31,534 different words. Whatever the size of the English lexicon at the time, Shakespeare was in command of a substantial portion of it. Jason Kottke estimates that Shakespeare knew around 66,534 words, which suggests Shakespeare was pushing the boundaries of English vocab as he knew it. He had to make up some new words.

The Complete List of Words Shakespeare Invented

Compiling a definitive list of every word that Shakespeare ever invented is impossible. But creating a list of the words that Shakespeare almost certainly invented can be done. We generated list of words below by starting with the words that Shakespeare was the first to use in written language, and then applying research that has identified which words were probably in everyday use during Shakespeare’s time. The result are 420 bona fide words minted, coined, and invented by Shakespeare, from “academe” to “zany”:

- academe

- accessible

- accommodation

- addiction

- admirable

- aerial

- airless

- amazement

- anchovy

- arch-villain

- auspicious

- bacheolorship

- barefaced

- baseless

- batty

- beachy

- bedroom

- belongings

- birthplace

- black-faced

- bloodstained

- bloodsucking

- blusterer

- bodikins

- braggartism

- brisky

- broomstaff

- budger

- bump

- buzzer

- candle holder

- catlike

- characterless

- cheap

- chimney-top

- chopped

- churchlike

- circumstantial

- clangor

- cold-blooded

- coldhearted

- compact

- consanguineous

- control

- coppernose

- countless

- courtship

- critical

- cruelhearted

- Dalmatian

- dauntless

- dawn

- day’s work

- deaths-head

- defeat

- depositary

- dewdrop

- dexterously

- disgraceful

- distasteful

- distrustful

- dog-weary

- doit (a Dutch coin: ‘a pittance’)

- domineering

- downstairs

- dwindle

- East Indies

- embrace

- employer

- employment

- enfranchisement

- engagement

- enrapt

- epileptic

- equivocal

- eventful

- excitement

- expedience

- expertness

- exposure

- eyedrop

- eyewink

- fair-faced

- fairyland

- fanged

- fap

- far-off

- farmhouse

- fashionable

- fashionmonger

- fat-witted

- fathomless

- featureless

- fiendlike

- fitful

- fixture

- fleshment

- flirt-gill

- flowery

- fly-bitten

- footfall

- foppish

- foregone

- fortune-teller

- foul mouthed

- Franciscan

- freezing

- fretful

- full-grown

- fullhearted

- futurity

- gallantry

- garden house

- generous

- gentlefolk

- glow

- go-between

- grass plot

- gravel-blind

- gray-eyed

- green-eyed

- grief-shot

- grime

- gust

- half-blooded

- heartsore

- hedge-pig

- hell-born

- hint

- hobnail

- homely

- honey-tongued

- hornbook

- hostile

- hot-blooded

- howl

- hunchbacked

- hurly

- idle-headed

- ill-tempered

- ill-used

- impartial

- imploratory

- import

- in question

- inauspicious

- indirection

- indistinguishable

- inducement

- informal

- inventorially

- investment

- invitation

- invulnerable

- jaded

- juiced

- keech

- kickie-wickie

- kitchen-wench

- lackluster

- ladybird

- lament

- land-rat

- laughable

- leaky

- leapfrog

- lewdster

- loggerhead

- lonely

- long-legged

- love letter

- lustihood

- lustrous

- madcap

- madwoman

- majestic

- malignancy

- manager

- marketable

- marriage bed

- militarist

- mimic

- misgiving

- misquote

- mockable

- money’s worth

- monumental

- moonbeam

- mortifying

- motionless

- mountaineer

- multitudinous

- neglect

- never-ending

- newsmonger

- nimble-footed

- noiseless

- nook-shotten

- obscene

- ode

- offenseful

- offenseless

- Olympian

- on purpose

- oppugnancy

- outbreak

- overblown

- overcredulous

- overgrowth

- overview

- pageantry

- pale-faced

- passado

- paternal

- pebbled

- pedant

- pedantical

- pendulous

- pignut

- pious

- please-man

- plumpy

- posture

- prayerbook

- priceless

- profitless

- Promethean

- protester

- published

- puking (disputed)

- puppy-dog

- pushpin

- quarrelsome

- radiance

- rascally

- rawboned

- reclusive

- refractory

- reinforcement

- reliance

- remorseless

- reprieve

- resolve

- restoration

- restraint

- retirement

- revokement

- revolting

- ring carrier

- roadway

- roguery

- rose-cheeked

- rose-lipped

- rumination

- ruttish

- sanctimonious

- satisfying

- savage

- savagery

- schoolboy

- scrimer

- scrubbed

- scuffle

- seamy

- self-abuse

- shipwrecked

- shooting star

- shudder

- silk stocking

- silliness

- skim milk

- skimble-skamble

- slugabed

- soft-hearted

- spectacled

- spilth

- spleenful

- sportive

- stealthy

- stillborn

- successful

- suffocating

- tanling

- tardiness

- time-honored

- title page

- to arouse

- to barber

- to bedabble

- to belly

- to besmirch

- to bet

- to bethump

- to blanket

- to cake

- to canopy

- to castigate

- to cater

- to champion

- to comply

- to compromise

- to cow

- to cudgel

- to dapple

- to denote

- to dishearten

- to dislocate

- to educate

- to elbow

- to enmesh

- to enthrone

- to fishify

- to glutton

- to gnarl

- to gossip

- to grovel

- to happy

- to hinge

- to humor

- to impede

- to inhearse

- to inlay

- to instate

- to lapse

- to muddy

- to negotiate

- to numb

- to offcap

- to operate

- to out-Herod

- to out-talk

- to out-villain

- to outdare

- to outfrown

- to outscold

- to outsell

- to outweigh

- to overpay

- to overpower

- to overrate

- to palate

- to pander

- to perplex

- to petition

- to rant

- to reverb

- to reword

- to rival

- to sate

- to secure

- to sire

- to sneak

- to squabble

- to subcontract

- to sully

- to supervise

- to swagger

- to torture

- to un muzzle

- to unbosom

- to uncurl

- to undervalue

- to undress

- to unfool

- to unhappy

- to unsex

- to widen

- tortive

- traditional

- tranquil

- transcendence

- trippingly

- unaccommodated

- unappeased

- unchanging

- unclaimed

- unearthy

- uneducated

- unfrequented

- ungoverned

- ungrown

- unhelpful

- unhidden

- unlicensed

- unmitigated

- unmusical

- unpolluted

- unpublished

- unquestionable

- unquestioned

- unreal

- unrivaled

- unscarred

- unscratched

- unsolicited

- unsullied

- unswayed

- untutored

- unvarnished

- unwillingness

- upstairs

- useful

- useless

- valueless

- varied

- varletry

- vasty

- vulnerable

- watchdog

- water drop

- water fly

- well-behaved

- well-bred

- well-educated

- well-read

- wittolly

- worn out

- wry-necked

- yelping

- zany

Words That Shakespeare Invented – Resource List

- 10 Words Shakespeare Never Invented – Merriam-Webster does a great job dismantling myths. This article, in particular, tells you which words Shakespeare probably didn’t invent.

- 40 Words You Can Trace Back To William Shakespeare – Buzzfeed disregards the “never invented” words from Merriam, but does add a disclaimer: “That doesn’t necessarily mean he invented every word.”

- Invented Words – This page was the center of a disputatious brouhaha with the aforementioned Buzzfeed. As it stands, however, Google likes to deliver this as a top result when you search for “Words Shakespeare Invented.”

- 20 Words We Owe to Shakespeare – I like the way that the author of this article draws a parallel between Shakespeare and the LOL generation.

- Words and Phrases Coined by Shakespeare – This is a lengthy and straightforward list that mostly contains phrases rather than individual words.

- 21 everyday phrases that come straight from Shakespeare’s plays – This is a helpful resource due to the explanation of each phrase.

Words, words, words.

(Hamlet Act 2, Scene 2)

What do you like to do in your spare time? Us… well, we get our reading heads on, light the fire, pour a glass of malmsy and work our way through our most-favourite plays and sonnets by William Shakespeare, pulling out some of our most-favourite words along the way. To share with you all, of course. Just because.

So, here you go. 50 words that appear in Shakespeare’s texts that we love for no particular reason at all. We hope you enjoy slotting some kicky-wickys, noddles, welkins and buzzers into your every day conversations (go on, we know you can do it).

1. Hiems (n.)

The personification of Winter, this word is used twice by Shakespeare, in Love’s Labour’s Lost (‘This side is Hiems, Winter, this Ver, the Spring; the one maintained by the owl, the other by the cuckoo. Ver, begin.) and A Midsummer Night’s Dream (‘And on old Hiems’ thin and icy crown.’).

2. Malmsey (n.)

A sweet, fortified wine (‘Nay then, two treys, and if you grow so nice, Metheglin, wort, and malmsey: well run, dice!’ Love’s Labour’s Lost).

Don’t we look pretty when good old Hiems brings us snow?

3. Sneap (n.)

Snub, reproof, rebuke (‘My lord, I will not undergo this sneap without reply.’ Henry IV, Part II).

4. Sluggardiz’d (v.)

To be made into an idler (‘I rather would entreat thy company To see the wonders of the world abroad, Than, living dully sluggardized at home’ The Two Gentlemen of Verona).

5. Puissance (n.)

Meaning power, or might (‘Cousin, go draw our puissance together.’ King John).

William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, 1623 (Munro First Folio). Photographer: Pete Le May.

6. Mobbled (adj.)

With face muffled up, veiled (‘But who, O who had seen the mobbled queen’ (Hamlet).

9. Egregious (adj.)

Remarkably good or great (of things) / striking, significant (of events and utterances) – ‘Except..thou do give to me egregious Ransome’ Henry V.

10. Consanguineous (adj.)

Of the same blood, related by blood, akin; of or pertaining to those so related (‘Am not I consanguineous? am I not of her blood?’ Twelfth Night).

11. Caper (v.)

To dance with joy, to leap with delight (‘No, sir, it is legs and thighs. Let me see thee caper. Ha! Higher! Ha! Ha! Excellent!’ Twelfth Night).

12. Expiate (v.)

To bring to an end (‘When in thee time’s furrows I behold, Then look I death my days should expiate.’ Sonnet 22).

13. Mated (adj.)

Bewildered, confused (‘I think you are all mated, or stark mad.’ The Comedy of Errors).

14. Foison (n.)

Abundance, plenty, profusion (‘All things in common nature should produce Without sweat or endeavour: treason, felony, Sword, pike, knife, gun, or need of any engine, Would I not have; but nature should bring forth, Of its own kind, all foison, all abundance, To feed my innocent people.’ The Tempest).

15. Guileful (adj.)

Full of guile, deceitful, devious, as spoken in Henry VI, Part I – ‘Amongst the soldiers this is muttered: That here you maintain several factions, And whilst a field should be dispatched and fought, You are disputing of your generals. One would have ling’ring wars, with little cost; Another would fly swift, but wanteth wings; A third thinks, without expense at all, By guileful fair words peace may be obtained. Awake, awake, English nobility! Let not sloth dim your honours new-begot.’

16. Bacchanal (n.)

Dance in honour of Bacchus, the God of Wine – ‘Shall we dance now the Egyptian Bacchanals, And celebrate our drink?’ (Antony and Cleopatra).

‘Unbind my hands, I’ll pull them off myself,

Yea, all my raiment to my petticoat.’

– Bianca, The Taming of Shrew

Evelyn Miller as Bianca in Maria Gaitanidi’s The Taming of the Shrew in 2020 in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse. Photographer: Johan Persson.

17. Raiment (n.)

Clothing, vestments (as mentioned in The Taming of the Shrew). Clothes are also referred to as ‘Habiliments’ in the same play.

18. Welkin (n.)

The apparent arch or vault of heaven overhead; the sky, the firmament. As stated in Richard II (‘Amaze the welkin with your broken staves’), The Taming of the Shrew (‘Thy hounds shall make the welkin answer them.’) and Twelfth Night (‘But we shall make the welkin dance indeed?’).

19. Gamesome (adj.)

Sportive, merry, playful (‘For thou art pleasant, gamesome, passing courteous, But slow in speech’ The Taming of the Shrew).

20. Noddle (n.)

The back of the head (‘Doubt not her care should be To comb your noddle with a three-legged stool.’ The Taming of the Shrew).

21. Fleshment (n.)

The excitement associated with a successful beginning (‘And, in the fleshment of this dread exploit, Drew on me here again.’ King Lear).

22. Sceptered (adj.)

Invested with royal authority.

‘This royal throne of kings, this sceptred isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise,

This fortress built by Nature for herself

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in the silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands,–

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England.

– Richard II

Richard II, Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, 2019. Photographer: Ingrid Pollard.

23. Gratulate (v.)

Greet, welcome, salute (‘To gratulate thy plenteous bosom.’ Timon of Athens).

24. Peregrinate (v.)

Travel or wander from place to place (‘Too peregrinate, as I may call it.’ Love’s Labour’s Lost).

25. Kicky-wicky (n.)

Girl-friend, wife (‘That hugs his kicky-wicky here at home’ All’s Well That Ends Well).

26. Bawcock (n.)

Fine fellow, good chap (‘I’fecks, Why, that’s my bawcock.’ The Winter’s Tale).

27. Buzzer (n.)

Rumour-monger, gossiper (‘And wants not buzzers to infect his ear With pestilent speeches of his father’s death’ Hamlet).

28. Gallimaufry (n.)

Complete mixture, every sort, a medley, hotchpotch (‘He loves the gallimaufry’ The Merry Wives of Windsor).

29. Garboil (n.)

Trouble, disturbance, commotion, as Antony says to Cleopatra, ‘She’s dead, my queen. Look here, at thy sovereign leisure read The garboils she awaked. At last, best, See when and where she died.’

30. Miching (adj.)

Sneaking, sulking, lurking – ‘Marry, this is miching mallecho. That means mischief.’ (Hamlet).

31. Meed (n.)

Reward, prize, recompense (‘If you are hired for meed, go back again, And I will send you to my brother Gloucester’ Richard III).

32. Affy (v.)

To have confidence or trust in (‘Marcus Andronicus, so I do affy, In they uprightness and integrity’ Titus Andronicus).

33. Candle-waster (n.)

One who wastes candles by sitting up all night, probably not a reveller, as some have supposed, but a nocturnal student; a bookworm.

‘Bring me a father that so loved his child,

Whose joy of her is overwhelm’d like mine,

And bid him speak of patience;

Measure his woe the length and breadth of mine

And let it answer every strain for strain,

As thus for thus and such a grief for such,

In every lineament, branch, shape, and form:

If such a one will smile and stroke his beard,

Bid sorrow wag, cry ‘hem!’ when he should groan,

Patch grief with proverbs, make misfortune drunk

With candle-wasters; bring him yet to me,

And I of him will gather patience.’

– Much Ado About Nothing

Maybe candle-wasters could be found in our Sam Wanamaker Playhouse! Photographer: Pete Le May.

34. Questant (n.)

Seeker, searcher, someone engaged in a quest.

‘No, no, it cannot be; and yet my heart

Will not confess he owes the malady

That doth my life besiege.

Farewell, young lords;

Whether I live or die, be you the sons

Of worthy Frenchmen: let higher Italy,—

Those bated that inherit but the fall

Of the last monarchy,—see that you come

Not to woo honour, but to wed it; when

The bravest questant shrinks, find what you seek,

That fame may cry you loud: I say, farewell.’

– All’s Well That Ends Well

35. Lief (adv.)

Readily, willingly. Rosalind in As You Like It tells Orlando ‘I had as lief be woo’d of a snail.’

36. Urchin-snouted (adj.)

Having a nose like that of a hedgehog, or having a goblin-like, demoniac snout (‘But this foul, grim, and urchin-snouted boar’ Venus and Adonis).

37. Gambold (n.)

Frolic, entertainment, pastime – ‘Marry, I will; let them play it. Is not a comonty a Christmas gambold or a tumbling-trick?’ is from the prologue of The Taming of the Shrew.

38. Bluster (n.)

Storm, tempest, rough blast (‘We have landed in ill time. The skies look grimly And threaten present blusters.’ The Winter’s Tale).

39. Kirtle (n.)

Dress, gown. As Falstaff says to Doll in Henry IV, Part II ‘What stuff wilt have a kirtle of? I shall receive money o’Thursday; shalt have a cap tomorrow.’

40. Carcanet (n.)

A jewelled necklace – from Sonnet 52, ‘Like stones of worth they thinly placed are, Or captain jewels in the carcanet.’

41. Pell-mell (adv., adj., n.)

Confused and / or disorderly mass (‘Advance your standards, and upon them, lords; Pell-mell, down with them!’ Love’s Labour’s Lost).

42. Pother (n.)

Fuss, uproar, commotion – ‘Let the great gods, That keep this dreadful pother o’er our heads’ (King Lear).

43. Relume (v.)

Relight, rekindle, burn afresh. Othello says to himself ‘I know not where is that Promethean heat That can thy light relume.’

44. Frampold (adj.)

Disagreeable, bad-tempered, moody. ‘She leads a very frampold life with him,’ says Mistress Quickly to Falstaff in The Merry Wives of Windsor.

45. Younker (n.)

Fashionable young man, fine young gentleman. (‘Those will make the younker madder.’ say the Witches in Macbeth).

The Merry Wives of Windsor, Globe Theatre, 2019. Photographer: Helen Murray.

46. Germen (n.)

Seed, life-forming elements.

‘Blow, wind, and crack your cheeks! Rage, blow,

You cataracts and hurricanes, spout

Till you have drenched the steeples, drowned the cocks!

You sulphurous and thought-executing fires,

Vaunt-couriers to oak-cleaving thunderbolts,

Singe my white head; and thou all-shaking thunder,

Smite flat the thick rotundity of the world,

Crack nature’s mould, all germens spill at once

That make ingrateful man.’

– King Lear

47. Raze (v.)

To destroy completely (‘I’ll find a day to massacre them all And raze their faction and their family’ Titus Andronicus).

48. Ostent (n.)

Appearance; air; mein (‘Like one well studied in a sad ostent’ The Merchant of Venice).

49. Thrasonical (adj.)

Bragging; boastful; vainglorious. Quote from As You Like It – ‘There was never any thing so sudden but the fight of two rams and Caesar’s thrasonical brag of ‘I came, saw, and overcame’.’

50. Atomy (n.)

Atom, mote, speck, or mite, tiny being (‘It is as easy to count atomies as to resolve the propositions of a lover.’ As You Like It).

FINIS.

WE STILL NEED YOUR DONATIONS

After the most challenging year in our charity’s history, we still need our supporters to help us recover.

Please donate to help fund the future of Shakespeare’s Globe.

DONATE

Skip to content

William Shakespeare has made a great contribution to the English language. What role did Shakespeare play in the development of vocabulary? Shakespeare invented words by changing common words into nouns, verbs, or adjectives. As you can observe, some of Shakespeare words have either prefixes or suffixes. So, how many words did Shakespeare invent? There are more than 1700 words created by Shakespeare that we can see in his writings.

William Shakespeare may have invented thousands of words, however, some argued that some of these words might not have been invented by him. Instead, this list of Shakespeare vocabulary was actually first written on his works. Most scholars argued that these words which are credited to Shakespeare might have been spoken first. This contraversial topic may be a great idea for a thesis. Our thesis writers can help you handle it. Do you know what words did Shakespeare invent? Here, we will give you some of these words with its corresponding meanings.

Do You Know Some Shakespeare Words And Meanings?

Here are 50 words invented by Shakespeare. If you’d like to improve your writing skills, we advise you to learn and use them. Each word has its corresponding meaning. These words Shakespeare created has been used in one of his plays:

- Accommodation – means adaptation, adjustment, or compromise. Used in “Measure for Measure” – “For all the accommodations that thou bear’st Are nursed by baseness.”

- Addiction – meaning obsession or dependence. This is a common word that is usually used in celebrity news. However, it was first used in “Othello” – “what sport and revels his addiction leads him”

- Agile – means capable of moving instantly or easily. Can be found in “Romeo and Juliet” – “His agile arm beats down their fatal points.”

- Allurement – refers to enticement, appeal, or attraction. It was used in “All’s Well That Ends Well” – “one Diana, to take heed of the allurement of one Count Rousillon”.

- Antipathy – this is one of the words coined by Shakespeare that means to hate or dislike. Used in “King Lear” – “No contraries hold more antipathy Than I”.

- Arch-villain – by adding the prefix “arch-”: Shakespeare created this word that means a very mean person. He used this in “Timon of Athens” – “yet an arch-villain keeps him company”.

- Assassination – this term is used to describe a violent murder or killing. It was observed in “Macbeth” – “if the assassination could trammel up the consequence”.

- Bedazzled – this word was first used to describe the gleam of sunlight. But presently it is used for marketing rhinestone-embellished jeans. Has been used in “The Taming of the Shrew” – “my mistaking eyes, that have been so bedazzled with the sun”.

- Belongings – refers to possessions or properties. This is one of the words made by Shakespeare that can be seen in “Measure for Measure” – “thy belongings are not thine own”.

- Catastrophe – refers to disaster or the spectacular event that started the outcome of the story. You can read this in “King Lear” – “he comes, like the catastrophe of the old comedy.”

- Cold-blooded – most often this word is used to depict serial killers and vampires. But it was first used in “King John” – “Thou cold-blooded slave, hast thou not spoke”.

- Critical – very significant or prone to criticism. It was used in “Othello” – “For I am nothing, if not critical.”

- Demonstrate – to display, show, or present something. Also used in “Othello” – “this may help to thicken other proofs That do demonstrate thinly.”

- Dexterously – skillfully created or done with accuracy. Can be found in “Twelfth Night” – “Dexterously, good madonna.”

- Dire – means dreadful, miserable, or ominous. Used in “Comedy of Errors” – “To bear the extremity of dire mishap!”

- Dishearten – means to disappoint or dismay. The opposite or hearten is first used in “Henry V” – lest he, by showing it, should dishearten his army”

- Dislocate – means to make it out of place. This is shown in “King Lear” – “to dislocate and tear Thy flesh and bones.”

- Emphasis – it means giving attention to something or making it prominent. Can be seen in “Antony and Cleopatra” – “Be choked with such another emphasis!”

- Eventful – it is used to describe a momentous or exciting moment. It was expressed in “As You Like It” – “that ends this strange eventful history”

- Eyeballs – is another word for the eyes. Used in “As You Like It” – “Your bugle eyeballs, nor your cheek of cream,”

- Emulate – means to copy or imitate something. Can be read in “Merry Wives of Windsor” – “I see how thine eye would emulate the diamond”.

- Exist – means to obtain a reality. Used in “King Lear” – “From whom we do exist and cease to be;”

- Extract – means to withdraw, eliminate, draw out. This is depicted in “Henry V” – “Could out of thee extract one spark of evil”.

- Fashionable – it means stylish or trendy. Centuries ago it was used in “Troilus and Cressida” – “For time is like a fashionable host”.

- Frugal – refers to a person who is economical, thrifty, stingy. It was used in “Merry Wives of Windsor” – “I was then frugal of my mirth”.

- Half-blooded – having a relationship with one parent only. First used in “King Lear” – “Half-blooded fellow, yes.”

- Hot-blooded – being passionate or showing extreme feelings. Also used in “King Lear” – “the hot-blooded France, that dowerless took our youngest born”.

- Hereditary – something that you have inherited, congenital. This is evident in “Antony and Cleopatra” – “Hereditary, rather than purchased”.

- Horrid – means horrible or dreadful. One of the common Shakespeare words that was used in “Hamlet” – “cleave the general ear with horrid speech“.

- Impertinent – refers to being insolent, irrelevant, disrespectful. This is apparent in “Tempest” – “the suit is impertinent to myself”.

- Inaudible – refers to being silent or imperceptible. Was first expressed in “All’s Well That Ends Well” – on our quick’st decrees the inaudible and noiseless foot of Time”.

- Jovial – means being happy, cheerful, or jolly. Is used in “Macbeth” – “Be bright and jovial among your guests”.

- Ladybird – refers to a small, round beetle. But during Shakespeare’s time, it does not probably refer to the beetle, but rather it could mean “sweetheart”. It was mentioned in “Romeo and Juliet” – “What, lamb! What, ladybird!”.

- Manager – meaning the administrator or the person who runs the company. It was used to depict as such in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” – “Where is our usual manager of mirth?”.

- Meditate – means to ponder, contemplate, or think. This is expressed in “Twelfth Night” – “I will meditate the while upon some horrid message”.

- Modest – means shy, moderate, or humble. It is used in “Coriolanus” – “but hunt With modest warrant”.

- Multitudinous – it means “a lot” or “too many”. Used in “Macbeth” – “this my hand will rather the multitudinous seas in incarnadine”.

- Mutiny – refers to revolution, uprising, or resistance. Is it found in “Julius Caesar” – “To such a sudden flood of mutiny”.

- New-fangled – it is used for describing the latest or the newest. Used in “Love’s Labour’s Lost” – “I no more desire a rose than wish a snow in May’s new-fangled mirth”.

- Obscene – means something indecent, immoral, or offensive. Can be observed in “Richard II” – “show so heinous, black, obscene a deed!”

- Pageantry – one of the words that Shakespeare created to describe a lavish show. It was described in “Pericles, Prince of Tyre” – “that you aptly will suppose what pageantry”.

- Pedant – someone who is perfectionist or formalist. It is used in “Twelfth Night” – “like a pedant that keeps a school”.

- Pell-mell – means something disordered, clutter, or in chaos. Used in “Love’s Labour’s Lost” – “Pell-mell, down with them!”

- Premeditated – something that is planned, intended, or deliberate. From “Henry V” – “have on them the guilt of premeditated and contrived murder”.

- Reliance – refers to assurance or dependence. From “Timon of Athens” – “And my reliances on his fracted dates”.

- Scuffle – refers to a brawl or a fight. It was first introduced in “Antony and Cleopatra” – “His captain’s heart, which in the scuffles of great fights”.

- Submerged – means immerse, sink, or underwater. This is used in “Antony and Cleopatra” – “So half my Egypt were submerged and made”.

- Swagger – means someone who is bragging or boasting. It was used in “Henry V” – “a rascal that swaggered with me last night”.

- Uncomfortable – feeling awkward or uneasy. This word was mentioned in “Romeo and Juliet” – “Uncomfortable time, why camest thou now”.

- Vast – something that is ample, very large or wide in range. Used in “Timon of Athens” – “with his great attraction Robs the vast sea”.

We hope that you have learned something from this Shakespeare words list. Knowing how many words did Shakespeare invented will make us wonder, is it also possible that we could create our new words and be understood?

Undeniably, whether or not he was the first to write down this list of words Shakespeare invented, he is still responsible for making them popular.

Even today, Shakespeare’s writings still continue to live on in our culture and tradition. It’s probably because his influence has become an important part in the development of our English language. It seems that Shakespeare’s writings have been deeply implanted in our culture, making it hard to image having a modern literature without his influence.