English

Alternative forms

- sexe (archaic)

- s’x, s*x (censored)

Pronunciation

- enPR: sĕks, IPA(key): /sɛks/

- Rhymes: -ɛks

- Homophone: secs

Etymology 1

From Middle English sexe (“gender”), from Old French sexe (“genitals; gender”), from Latin sexus (“gender; gender traits; males or females; genitals”), from Proto-Italic *seksus, from Proto-Indo-European *séksus, from *sek- (“to cut, cut off, sever”), thus meaning «section, division» (into male and female).

Usage for women influenced by Middle French le sexe (“women”) (attested in 1580). Usage for third and additional sexes calqued from French troisième sexe, referring to masculine women in 1817 and homosexuals in 1847. First used by Lord Byron and others in English in reference to Catholic clergy. Usage for sexual intercourse first attested in 1900 (in the writings of H.G. Wells).

Noun

sex (countable and uncountable, plural sexes)

- (countable) A category into which sexually-reproducing organisms are divided on the basis of their reproductive roles in their species.

-

The effect of the medication is dependent upon age, sex, and other factors.

- 1994, Valerie Harms, Uc Rodale Nat Aud Enviro, page 268:

- I would never have guessed […] that slime molds can have thirteen sexes.

-

- (countable) Another category, especially of humans and especially based on sexuality or gender roles.

-

1791 (date written), Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects, 1st American edition, Boston, Mass.: […] Peter Edes for Thomas and Andrews, […], published 1792, →OCLC:

-

Still there are some loop-holes out of which a man may creep, and dare to think and act for himself; but for a woman it is an herculean task, because she has difficulties peculiar to her sex to overcome, which require almost super-human powers.

-

- 1817, The works of Claudian, tr. into Engl. verse by A. Hawkins, page 43:

- «But now another sex, in arms, is brought, / And, realms to guard, are eunuchs able thought!»

- 1821, Lord Byron, Don Juan, Canto V, Stanza xxvi, line 148:

- A black old neutral personage

Of the third sex stept up.

- A black old neutral personage

- 1992, United States Naval Institute Proceedings (volume 118, page 23)

- I have encountered officers who believe a woman got a better assignment or somehow «got over» because of her sex.

-

- (countable) The members of such a category, taken collectively.

- 1671, John Milton, Samson Agonistes, 774:

- It was a weakness

In me, but incident to all our sex.

- It was a weakness

- 1780, Jeremy Bentham, Introduction to the Principles of Morals & Legislation, vi, §35:

- The sensibility of the female sex appears […] to be greater than that of the male.

- 1671, John Milton, Samson Agonistes, 774:

- (uncountable) The distinction and relation between these categories, especially in humans; gender.

- 2005 November 11, Guardian, 18:

- A lot of women now like men to pay for them on dates… We’ve dealt with the outdated view of sex underpinning this.

- 2005 November 11, Guardian, 18:

- (obsolete or literary, uncountable, with «the») Women; the human female gender and those who belong to it.

- 1789 November 3, Arthur Young, Travels… undertaken with a view of ascertaining the cultivation… of the kingdom of France, i, 220:

- The sex of Venice are undoubtedly of a distinguished beauty.

-

c. 1840, George Nelson, Reminiscenses:

-

I was not, however, better than my neighbors; the Sex had its charms for me as it had for others; But there always remained a sting, that time only wore away.

-

-

1862, Wilkie Collins, No Name:

-

Even the reptile temperament of Noel Vanstone warmed under the influence of the sex: he had an undeniably appreciative eye for a handsome woman, and Magdalen’s grace and beauty were not thrown away on him.

-

- 1789 November 3, Arthur Young, Travels… undertaken with a view of ascertaining the cultivation… of the kingdom of France, i, 220:

- (uncountable) Sexual activity, usually sexual intercourse unless preceded by a modifier.

-

1900, H. G. Wells, Love and Mr. Lewisham[1], London: Harper, page 144:

-

We marry in fear and trembling, sex for a home is the woman’s traffic, and the man comes to his heart’s desire when his heart’s desire is dead.

-

- 1929, D.H. Lawrence, Pansies, 57:

- If you want to have sex, you’ve got to trust

At the core of your heart, the other creature.

- If you want to have sex, you’ve got to trust

- 1934, translation of the Qur’an (23:5) by Abdullah Yusuf Ali

- (The believers … those … ) who abstain from sex

- 1962 June 7, The Listener, 1006/2:

- Why wasn’t Bond ‘more tender’ in his love-making? Why did he just ‘have sex’ and disappear?

- 1990, House of Cards, Season 1, Episode 3:

- It wouldn’t work with you… Sex, I mean. You’re… easy to be with. You’re… you’re not dangerous. You’re my best friend, John. I couldn’t have it on with my best friend, John. It would be embarrassing. Sorry. Honest.

-

- (countable, euphemistic or slang) Genitalia: a penis or vagina.

- 1664, Thomas Killigrew, Princess, ii, ii:

- Another ha’s gon through with the bargain… One that will find the way to her Sex, before you’le come to kissing her hand.

- 1938, David Gascoyne, Hölderlin’s Madness, 18:

- And the black cypresses strained upwards like the sex of a hanged man.

- 1993, Catherine Coulter, The Heiress Bride, page 354:

- She touched his sex with her hand.

- 2003 March 2, Daily News of New York, 2:

- And he put in a fake sex (penis) because he wanted to make the scene more real, more rude.

- 1664, Thomas Killigrew, Princess, ii, ii:

Usage notes

- Sometimes, sex and gender are distinguished.

Synonyms

- (divisions of organisms by reproductive role): gender (proscribed when referring to humans: see usage note)

- (copulation): See also Thesaurus:copulation

Hypernyms

- See species

Hyponyms

- (usual): See male and female

- (in some contexts): See bigender, transgender, genderless, intersex, genderfluid, homosexual, eunuch

- (jocular, now uncommon): See clergy

Derived terms

- anal sex

- battle of the sexes

- better than sex

- cross sex

- cross-sex

- cybersex

- desex

- electrosex

- fair sex

- fairer sex

- gendersex

- group sex

- have sex

- intercrural sex

- intersex

- leathersex

- nonpenetrative sex

- opposite sex

- oral sex

- penetrative sex

- phone sex

- safe sex

- safer sex

- sex abuse

- sex act

- sex activity

- sex addict

- sex addiction

- sex affair

- sex aid

- sex and shopping

- sex antagonism

- sex appeal

- sex assignment

- sex attractant

- sex awareness

- sex behavior

- sex behaviour

- sex bomb

- sex call

- sex cell

- sex change

- sex character

- sex characteristic

- sex chromatin

- sex chromosome

- sex circuit

- sex clinic

- sex complex

- sex compulsion

- sex conflict

- sex consciousness

- sex contrast

- sex correlation

- sex craving

- sex crime

- sex criminal

- sex determinant

- sex determination

- sex determiner

- sex difference

- sex discrimination

- sex disqualification

- sex distinction

- sex distribution

- sex divergence

- sex doll

- sex drive

- sex drug

- sex ed

- sex education

- sex educator

- sex emotion

- sex equality

- sex excitement

- sex experience

- sex exploitation

- sex feeling

- sex festival

- sex fiend

- sex film

- sex function

- sex game

- sex gene

- sex gland

- sex god

- sex goddess

- sex guru

- sex hair

- sex heredity

- sex hormone

- sex hygiene

- sex impulse

- sex industry

- sex instinct

- sex instruction

- sex interest

- sex intergrade

- sex joke

- sex killer

- sex kitten

- sex life

- sex love

- sex machine

- sex magazine

- sex man

- sex mania

- sex maniac

- sex manifestation

- sex manual

- sex morality

- sex mosaic

- sex movie

- sex novel

- sex object

- sex obsession

- sex offence

- sex offender

- sex offense

- sex on a stick

- sex on legs

- Sex on the Beach

- sex organ

- sex orgy

- sex pact

- sex partner

- sex party

- sex pest

- sex play

- sex power

- sex pride

- sex privilege

- sex problem

- sex question

- sex ratio

- sex reassignment surgery

- sex relation

- sex relationship

- sex repression

- sex reversal

- sex ring

- sex role

- sex scandal

- sex scene

- sex selection

- sex shop

- sex show

- sex slave

- sex slavery

- sex starvation

- sex stereotype

- sex stereotyping

- sex story

- sex surrogate

- sex symbol

- sex talk

- sex tape

- sex therapist

- sex therapy

- sex thrill

- sex tour

- sex tourism

- sex tourist

- sex toy

- sex trade

- sex union

- sex urge

- sex war

- sex warfare

- sex work

- sex worker

- sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll

- sex, lies, and videotape

- sex-abusing

- sex-alive

- sex-anger

- sex-angry

- sex-appeal

- sex-appealing

- sex-blind

- sex-chromosomal

- sex-conscious

- sex-crazed

- sex-determining

- sex-discriminating

- sex-discriminatory

- sex-emancipated

- sex-flow

- sex-free

- sex-hate

- sex-hatred

- sex-hungry

- sex-inertia

- sex-influenced

- sex-killing

- sex-kittenish

- sex-linked

- sex-longing

- sex-mad

- sex-negative

- sex-neutral

- sex-obsessed

- sex-positive

- sex-related

- sex-reversed

- sex-reversing

- sex-ridden

- sex-segregated

- sex-selective

- sex-smelling

- sex-specific

- sex-specificity

- sex-starved

- sex-transforming

- sex-typed

- sex-typing

- sexboat

- sexer

- sexercise

- sexful

- sexless

- sexlinked

- sexologist

- sexology

- sexpect

- sexpectation

- sexperiment

- sexpert

- sexploitation

- sexploration

- sexpot

- sexy

- succsex

- succsexful

- third sex

- unisex

- unsex

- vaginal sex

- weaker sex

- whimsical sex

- sexual

- sexualiation

- sexualise

- sexuality

- sexualization

- sexualize

- sexually

Descendants

- → Dutch: seks

- → German: Sex

- → Hindi: सेक्स (seks)

Translations

See also

- female

- gender

- gendersex

- intersexed

- male

- missexed

- missexing

- sex up

- sexuality

- third sex

- unsex

Verb

sex (third-person singular simple present sexes, present participle sexing, simple past and past participle sexed)

- (zoology, transitive) To determine the sex of (an animal).

-

1878 January 19, Spirit of the Times, 659/2:

-

If we sex the cattle, which is the only way to get at their value, we shall have… 400 cows, 200 yearling heifers.

-

-

2007, Clive Roots, Domestication, page 75:

-

The ability to sex birds invasively through laparoscopy initially solved that problem, but now it is even easier and less stressful on the birds through testing the DNA of their feathers or blood.

-

-

2013, David J Patterson; Michael T. Smith, Beef Heifer Development, An Issue of Veterinary Clinics: Food Animal Practice,, Elsevier Health Sciences, →ISBN:

-

Semen usually is sexed at 90% accuracy, and the sexes of calves at birth almost always are in that statistical range if averaged over […]

-

-

- (chiefly US, colloquial, transitive) To have sex with.

-

2007, Mickey Hess, Icons of hip hop : an encyclopedia of the movement, music, and culture. 2, Greenwood Publishing Group, →ISBN, page 427:

-

He shows some glimpses, but most of the released singles are about flossing, partying, and sexing women.

-

- 2009, HoneyB,, Single Husbands, Grand Central Publishing (→ISBN):

- Sex with Ivory had gotten better than sexing his wife. Herschel laughed with Ivory, cried with Ivory. They dreamt aloud together. Unlike Nikki, Ivory believed in him. Every man needed a woman who believed in him.

-

2012, Janice Jones, His Woman, His Wife, His Widow, Urban Books, →ISBN:

-

«Do you ever think about how you’re betraying your client while you’re sexing his wife?»

-

-

2014, Jerrold S. Greenberg; Clint E. Bruess; Sara B. Oswalt, Exploring the Dimensions of Human Sexuality, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, →ISBN, page 731:

-

Wosick-Correa, K. R., 81 Joseph, L. J. Sexy ladies sexing ladies: Women as consumers in strip clubs. Journal of Sex Research, 45, 3 (July 2008), 201-216.

-

-

2014, Anya Nicole, Judgment Day, Urban Books, →ISBN:

-

His body shook uncontrollably as he imagined another man sexing his wife.

-

-

2015, Pimpin’ Ken, The Art of Human Chess: A Study Guide to Winning, →ISBN, page 117:

-

The last thing a jealous husband wants to think about is another man sexing his wife when he’s dead and gone.

-

-

2016, Nisa Santiago, Killer Dolls — Part 3, Melodrama Publishing, →ISBN:

-

Sexing his wife anally would remind him of having sex with Baron.

-

-

2019, Michael Jean Nystrom-Schut, Foundations of Philosophy: The Basics of the Balance (Volume Iil), AuthorHouse, →ISBN:

-

The neighbor guy, I just came to understand, is sexing the lady across the street from him. He’s got a girlfriend. She is married. While I don’t think that is particularly cool, I also don’t think it is any of my business either.

-

-

- (chiefly US, colloquial, intransitive) To have sex.

-

1921 August 20, Burke, Kenneth, letter to Malcolm Cowley:

-

Our baby is eighteen months old now, and cries when we sex

-

-

Synonyms

- (to have sex): do it, get it on, have sex; see also Thesaurus:copulate

Derived terms

- missex

- sex up

Translations

Further reading

- Oxford English Dictionary, «sex, n.1«, 2008.

- Oxford English Dictionary, «sex, v.«, 2008.

Etymology 2

From sect.

Noun

sex (plural sexes)

- (obsolete) Alternative form of sect.

Further reading

- Oxford English Dictionary, «sex, n.2«, 2008.

- «sex» in Raymond Williams, Keywords (revised), 1983, Fontana Press, page 283.

Anagrams

- Xes, exs., sXe

Czech

Alternative forms

- sexus (rare)

Etymology

Borrowed from Latin sexus.

Pronunciation

- IPA(key): [ˈsɛks]

- Hyphenation: sex

Noun

sex m inan

- sex (sexual intercourse)

- Synonym: See also soulož

Declension

- bisexualita

- bisexuál

- bisexuální

- heterosexualita

- heterosexuál

- heterosexuální

- homosexualismus

- homosexualita

- homosexuál

- homosexuální

- sexismus

- sexista

- sexistický

- sexovat

- sexualita

- sexualizace

- sexualizovat

- sexuální

- sexuolog

- sexuologický

- sexuologie

- transsexualismus

- transsexualita

- transsexuál

- transsexuální

Further reading

- sex in Kartotéka Novočeského lexikálního archivu

- sex in Slovník spisovného jazyka českého, 1960–1971, 1989

- sex in Internetová jazyková příručka

Danish

Etymology

From English sex.

Pronunciation

- Homophone: seks

Noun

sex c

- (uncountable) Sexual intercourse, sex.

Derived terms

- analsex

- gruppesex

- oralsex

- sexet (adjective)

- seksualitet c

- seksuel (adjective)

Dutch

Noun

sex m (uncountable)

- (proscribed) Alternative spelling of seks

Usage notes

- Certain magazines use sex instead of seks, since the correct spelling is regarded more neutral and official, and the other more exciting.

Icelandic

| < 5 | 6 | 7 > |

|---|---|---|

| Cardinal : sex Ordinal : sjötti |

||

Etymology 1

From Old Norse sex, from Proto-Germanic *sehs.[1] Cognates include Faroese seks and Danish seks.

Pronunciation

- IPA(key): [sɛks], [sɛxs]

- Rhymes: -ɛks, -ɛxs

- (regional) IPA(key): [sɛɣs]

Numeral

sex

- six

Derived terms

- klukkan sex

- sexa

Etymology 2

Borrowed from English sex, from Middle English sexe, from Old French sexe, from Latin sexus.[1]

Pronunciation

- IPA(key): [sɛks]

- Rhymes: -ɛks

Noun

sex n (genitive singular sex, nominative plural sex)

- sex, sexual intercourse

Declension

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ásgeir Blöndal Magnússon — Íslensk orðsifjabók, 1st edition, 2nd printing (1989). Reykjavík, Orðabók Háskólans, page 808. (Available on Málið.is under the “Eldra mál” tab.)

Interlingua

Etymology

From Old Norse sex, from Proto-Germanic *sehs, from Proto-Indo-European *swéḱs (“six”).

Numeral

sex

- six

Latin

| 60 | ||

| [a], [b] ← 5 | VI 6 |

7 → |

|---|---|---|

| Cardinal: sex Ordinal: sextus Adverbial: sexiēs, sexiēns Multiplier: sexuplus, sexuplex, sextuplus, seplex Distributive: sēnī Fractional: sextāns |

Alternative forms

- Symbol: VI

Etymology

From Proto-Italic *seks, from Proto-Indo-European *swéḱs.

Cognates include Sanskrit षष् (ṣaṣ), Old Armenian վեց (vecʿ), Ancient Greek ἕξ (héx), and Old English six (English six).

Pronunciation

- (Classical) IPA(key): /seks/, [s̠ɛks̠]

- (Ecclesiastical) IPA(key): /seks/, [sɛks]

Numeral

sex (indeclinable)

- six; 6

-

c. 52 BCE, Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico 2.5:

- Ibi praesidium ponit et in altera parte fluminis Q.Titurium Sabinum legatum cum sex cohortibus relinquit;

- Over that river was a bridge: there he places a guard; and on the other side of the river he leaves Quintus Titurius Sabinus, his legate, with six cohorts.

- Ibi praesidium ponit et in altera parte fluminis Q.Titurium Sabinum legatum cum sex cohortibus relinquit;

-

8 CE, Ovid, Metamorphoses 2.17–18:

- haec super inposita est caeli fulgentis imago, signaque sex foribus dextris totidemque sinistris

- Above these was placed an image of the shining sky, and six signs [of the zodiac] on the doorways to the right and the same number on the left.

- haec super inposita est caeli fulgentis imago, signaque sex foribus dextris totidemque sinistris

-

405 CE, Jerome, Vulgate Exodus 16:26:

- sex diebus colligite in die autem septimo sabbatum est Domino idcirco non invenietur

- Six days ye shall gather it; but on the seventh day, which is the sabbath, in it there shall be none.

- sex diebus colligite in die autem septimo sabbatum est Domino idcirco non invenietur

-

Descendants

- Balkan Romance:

- Aromanian: shasi, shase, sheasi, shease

- Istro-Romanian: șåse

- Megleno-Romanian: șasi

- Romanian: șase

- Dalmatian:

- si

- Italo-Romance:

- Corsican: sei

- Italian: sei

- Neapolitan: séje

- Tarantino: sèje

- Sicilian: sei

- North Italian:

- Emilian: sē, siē

- Friulian: sîs

- Istriot: seije

- Ladin: sies

- Ligurian: sêi

- Lombard: sees

- Piedmontese: ses

- Romansch: sis, seis, ses

- Venetian: sei

- Gallo-Romance:

- Old French: sis

- Middle French: six

- French: six (see there for further descendants)

- Norman: six

- Walloon: shijh

- → Middle English: sice, sis

- English: sice, sise, size

- → Japanese: サイス (saisu)

- English: sice, sise, size

- Middle French: six

- Old French: sis

- Occitano-Romance:

- Catalan: sis

- Old Occitan: seis

- Occitan: sièis

- Ibero-Romance:

- Aragonese: seis

- Old Leonese:

- Asturian: seis, seyes

- Mirandese: seis

- Old Galician-Portuguese: seis, seys

- Galician: seis

- Portuguese: seis, seys, seix

- Kabuverdianu: sais

- Papiamentu: seis

- Spanish: seis

- → Aklanon: sais

- → Cebuano: sayis

- → Tagalog: sais

- Insular Romance:

- Sardinian: ses

See also

- Appendix:Latin cardinal numerals

References

- sex in Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short (1879) A Latin Dictionary, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- sex in Charlton T. Lewis (1891) An Elementary Latin Dictionary, New York: Harper & Brothers

- sex in William Smith, editor (1854, 1857) A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, volume 1 & 2, London: Walton and Maberly

Middle English

Etymology 1

Noun

sex

- sex

- a. 1382, Bible (Wycliffite), Genesis, Chapter vi, Verse 19:

- Of all þingez hauyng soule of eny flesch: two þou schalt brynge in to þe ark, þat male sex & female […]

- a. 1382, Bible (Wycliffite), Genesis, Chapter vi, Verse 19:

Etymology 2

From Old English seax.

Noun

sex

- Alternative form of sax

Etymology 3

From Old English sex, alternative form of six.

Numeral

sex

- Alternative form of six

Norwegian Bokmål

Etymology

From English sex, from Latin sexus.

Noun

sex m (definite singular sexen, uncountable)

- sex (sexual intercourse)

Derived terms

- sexliv

References

- “sex” in The Bokmål Dictionary.

- “sex” in Det Norske Akademis ordbok (NAOB).

Norwegian Nynorsk

Etymology

From English sex, from Latin sexus.

Noun

sex m (definite singular sexen, uncountable)

- sex (sexual intercourse)

Derived terms

- sexliv

References

- “sex” in The Nynorsk Dictionary.

Old English

Pronunciation

- IPA(key): /seks/

Noun

sex n (Late West Saxon)

- Alternative form of seax (“shortsword, dagger, knife”)

Old Frisian

| < 5 | 6 | 7 > |

|---|---|---|

| Cardinal : sex | ||

Etymology

From Proto-Germanic *sehs.

Numeral

sex

- six.

Descendants

- North Frisian:

- Föhr-Amrum, Mooring and Wiedingharde: seeks

- Helgoland: sös

- Sylt: soks

- Saterland Frisian: säks

- West Frisian: seis

Old Norse

| 60[a], [b], [c] | ||

| ← 5 | 6 | 7 → |

|---|---|---|

| Cardinal: sex Ordinal: sétti |

Etymology

From Proto-Germanic *sehs, whence also Old English six (English six), Old Frisian sex, Old Saxon sehs, Middle Dutch sesse (Dutch zes), Old High German sehs (German sechs), Gothic 𐍃𐌰𐌹𐌷𐍃 (saihs). Ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *swéḱs, cognate with Sanskrit षष् (ṣaṣ), Old Armenian վեց (vecʿ), Ancient Greek ἕξ (héx).

Numeral

sex

- (cardinal number) six

Descendants

- Icelandic: sex

- Faroese: seks

- Norn: siks

- Norwegian Bokmål: seks

- Norwegian Nynorsk: seks

- Old Swedish: sæx, siæx

- Swedish: sex

- Old Danish: sæx

- Danish: seks

- Elfdalian: sjäks

- Old Gutnish: siex

- Gutnish: siex, sex

References

- sex in Geir T. Zoëga (1910) A Concise Dictionary of Old Icelandic, Oxford: Clarendon Press

Pennsylvania German

| < 5 | 6 | 7 > |

|---|---|---|

| Cardinal : sex Ordinal : sext |

||

Alternative forms

- sechs

Etymology

Compare German sechs, Dutch zes, English six.

Pronunciation

- IPA(key): /sɛk͡s/

Numeral

sex

- six

Romanian

Etymology

Borrowed from Latin sexus.

Pronunciation

- IPA(key): /seks/

- Rhymes: -eks

Noun

sex n (plural sexe or sexuri)

- gender, sex

- sex, sexual intercourse

Usage notes

- The common plural form is sexe; sexuri is regional.

Declension

Declension of sex

| singular | plural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| indefinite articulation | definite articulation | indefinite articulation | definite articulation | |

| nominative/accusative | (un) sex | sexul | (niște) sexe | sexele |

| genitive/dative | (unui) sex | sexului | (unor) sexe | sexelor |

| vocative | sexule | sexelor |

Derived terms

- sexul slab

- sexul tare

Slovak

Etymology

Derived from English sex, from Latin sexus.

Pronunciation

- IPA(key): /ˈsɛks/

Noun

sex m inan (genitive singular sexu, nominative plural sexy, genitive plural sexov, declension pattern of dub)

- sex (intercourse, sexual activity)

Declension

Derived terms

- sexi, sexy (adjective)

- sexuálny (adjective)

- sexuálne (adverb)

- sexuálnosť f

References

- sex in Slovak dictionaries at slovnik.juls.savba.sk

Swedish

| < 5 | 6 | 7 > |

|---|---|---|

| Cardinal : sex Ordinal : sjätte |

||

Pronunciation

- IPA(key): /sɛks/

- Homophone: säcks (in accents that don’t distinguish short e and ä)

Etymology 1

Inherited from Old Swedish sæx, siæx, from Old Norse sex, from Proto-Germanic *sehs, from Proto-Indo-European *swéḱs (“six”).

Numeral

sex

- six

Coordinate terms

Cardinal numbers from 0 to 99

Cardinal numbers from 100 onward

Derived terms

- sexa

- sjätte

- sjättedel

See also

- noll, ett, två, tre, fyra, fem, sex, sju, åtta, nio, tio, elva, tolv

Etymology 2

Borrowed from English sex, from Latin sexus.

Noun

sex n (uncountable)

- sex (intercourse, sexual activity)

- att ha sex ― to have sex

Declension

| Declension of sex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncountable | ||||

| Indefinite | Definite | |||

| Nominative | sex | sexet | — | — |

| Genitive | sex | sexets | — | — |

Synonyms

- samlag, ligg

Uzbek

sex on Uzbek Wikipedia

Etymology

Borrowed from Russian цех (cex), from Polish cech, from Middle High German zëch(e); see modern German Zeche.

Noun

sex (plural sexlar)

- shop, section (of a factory)

Declension

Noun

The couple didn’t know what the sex of their baby would be.

How do you tell the sex of a hamster?

discrimination on the basis of sex

Her mom talked to her about sex.

She doesn’t like all the sex and violence in movies.

Recent Examples on the Web

Eventually, the sexes synced up and plenty of babies were produced, but the implications were eye-opening.

—

Lifestyle factors like smoking and excessive alcohol or drug use, age, and body weight can also undermine the ability to conceive in both sexes.

—

This latest update from NORC considered all sexes, ages, races and educational backgrounds for its year-long effort to calculate the percentage of the population living with obesity.

—

Both sexes laugh more with others than when alone.

—

Nearly every species includes lotharios (of both sexes) that sneak around doing their best to hide their gallivanting from their social partners.

—

Historians of science are well-versed in the ways fields traditionally filled with men have misunderstood and even demonized the bodies of other sexes and genders.

—

Women seem to be more aware of their weakness than men, making up more than 70% of research volunteers, though the deficit appears equally in both sexes.

—

Disadvantage ‘shifts the curve’ Klump says her lab’s research doesn’t show whether being from a disadvantaged background influences boys or girls more; direct comparison between the two sexes isn’t perfect since genetic risk comes into play at different stages of puberty for girls and boys.

—

But bring the kids anyway to this daftly sexed-up production.

—

To make matters all the more thirsty, that poster’s genitalia-like woodlands surround a smooching couple who appear to be a sexed-up version of beastiality tale Beauty and The Beast.

—

The preppy East Coast label has collaborated with everyone from Sacai and Supreme to Vetements, but West’s topper was a fresh foil for her typically sexed-up take on sportswear.

—

Yandy’s ark of offerings is evidence that pretty much any animal can be sexed up, although not all animals are equally alluring.

—

The most sexed-up take on the look saw one guy swaggering down the runway like a cheeky gunslinger.

—

Wills is officially headed to paradise, or, at least, sexed-up Bachelor Nation spin-off series Bachelor In Paradise, as People announced.

—

The classic look would often get sexed up with spit curls that lay slicked to the forehead, at the nape of the neck, or in front of the ear, thanks to the influence of Josephine Baker.

—

Each walleye harvested by the tribes is measured and sexed.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘sex.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Sex is the trait that determines whether a sexually reproducing organism produces male or female gametes.[1][2] Male plants and animals produce small mobile gametes (spermatozoa, sperm, pollen), while females produce larger, non-motile ones (ova, often called egg cells).[3] Organisms that produce both types of gametes are called hermaphrodites.[2][4] During sexual reproduction, male and female gametes fuse to form zygotes, which develop into offspring that inherit traits from each parent.

Males and females of a species may have physical similarities (sexual monomorphism) or differences (sexual dimorphism) that reflect various reproductive pressures on the respective sexes. Mate choice and sexual selection can accelerate the evolution of physical differences between the sexes.

The terms male and female typically do not apply in sexually undifferentiated species in which the individuals are isomorphic (look the same) and the gametes are isogamous (indistinguishable in size and shape), such as the green alga Ulva lactuca. Some kinds of functional differences between gametes, such as in fungi,[5] may be referred to as mating types.[6]

The sex of a living organism is determined by its genes. Most mammals have the XY sex-determination system, where male mammals usually carry an X and a Y chromosome (XY), whereas female mammals usually carry two X chromosomes (XX). Other chromosomal sex-determination systems in animals include the ZW system in birds, and the X0 system in insects. Various environmental systems include temperature-dependent sex determination in reptiles and crustaceans.[7]

Sexual reproduction

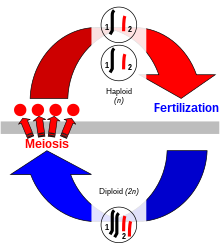

The life cycle of sexually reproducing organisms cycles through haploid and diploid stages

Sexual reproduction is a process exclusive to eukaryotes in which organisms produce offspring that possess a selection of the genetic traits of each parent. Genetic traits are contained within the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of chromosomes. The cells of eukaryotes have a set of paired homologous chromosomes, one from each parent, and this double-chromosome stage is called «diploid». During sexual reproduction, diploid organisms produce specialized haploid sex cells called gametes via meiosis,[8] each of which has a single set of chromosomes. Meiosis involves a stage of genetic recombination via chromosomal crossover, in which regions of DNA are exchanged between matched pairs of chromosomes, to form new chromosomes each with a new and unique combination of the genes of the parents. Then the chromosomes are separated into single sets in the gametes. Each gamete in the offspring thus has half of the genetic material of the mother and half of the father.[9] The combination of chromosomal crossover and fertilization, bringing the two single sets of chromosomes together to make a new diploid zygote, results in new organisms that contain different sets of the genetic traits of each parent.

In animals, the haploid stage only occurs in the gametes, the haploid cells that are specialized to fuse to form a zygote that develops into a new diploid organism. In plants, the diploid organism produces haploid spores by meiosis that are capable of undergoing repeated cell division to produce multicellular haploid organisms. In either case, gametes may be externally similar (isogamy) as in the green alga Ulva or may be different in size and other aspects (anisogamy).[10] The size difference is greatest in oogamy, a type of anisogamy in which a small, motile gamete combines with a much larger, non-motile gamete.[11]

By convention, the larger gamete (called an ovum, or egg cell) is considered female, while the smaller gamete (called a spermatozoon, or sperm cell) is considered male. An individual that produces exclusively large gametes is female, and one that produces exclusively small gametes is male.[12] An individual that produces both types of gametes is a hermaphrodite. In some cases, hermaphrodites are able to self-fertilize and produce offspring on their own, without the need for a partner.

Animals

Most sexually reproducing animals spend their lives as diploid, with the haploid stage reduced to single-cell gametes.[13] The gametes of animals have male and female forms—spermatozoa and egg cells. These gametes combine to form embryos which develop into new organisms.

The male gamete, a spermatozoon (produced in vertebrates within the testes), is a small cell containing a single long flagellum which propels it.[14]

Spermatozoa are extremely reduced cells, lacking many cellular components that would be necessary for embryonic development. They are specialized for motility, seeking out an egg cell and fusing with it in a process called fertilization.

Female gametes are egg cells. In vertebrates, they are produced within the ovaries. They are large, immobile cells that contain the nutrients and cellular components necessary for a developing embryo.[15] Egg cells are often associated with other cells which support the development of the embryo, forming an egg. In mammals, the fertilized embryo instead develops within the female, receiving nutrition directly from its mother.

Animals are usually mobile and seek out a partner of the opposite sex for mating. Animals which live in the water can mate using external fertilization, where the eggs and sperm are released into and combine within the surrounding water.[16] Most animals that live outside of water, however, use internal fertilization, transferring sperm directly into the female to prevent the gametes from drying up.

In most birds, both excretion and reproduction are done through a single posterior opening, called the cloaca—male and female birds touch cloaca to transfer sperm, a process called «cloacal kissing».[17] In many other terrestrial animals, males use specialized sex organs to assist the transport of sperm—these male sex organs are called intromittent organs. In humans and other mammals, this male organ is the penis, which enters the female reproductive tract (called the vagina) to achieve insemination—a process called sexual intercourse. The penis contains a tube through which semen (a fluid containing sperm) travels. In female mammals, the vagina connects with the uterus, an organ which directly supports the development of a fertilized embryo within (a process called gestation).

Because of their motility, animal sexual behavior can involve coercive sex. Traumatic insemination, for example, is used by some insect species to inseminate females through a wound in the abdominal cavity—a process detrimental to the female’s health.

Plants

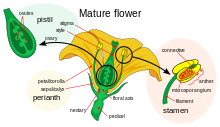

Flowers contain the sexual organs of flowering plants, usually containing both male and female parts.

Like animals, land plants have specialized male and female gametes.[18][19] In seed plants, male gametes are produced by reduced male gametophytes that are contained within hard coats, forming pollen. The female gametes of seed plants are contained within ovules. Once fertilized, these form seeds which, like eggs, contain the nutrients necessary for the initial development of the embryonic plant.

Female (left) and male (right) cones contain the sex organs of pines and other conifers.

The flowers of flowering plants contain their sexual organs. Flowers are usually hermaphroditic, containing both male and female sexual organs. The female parts, in the center of a flower, are the pistils, each unit consisting of a carpel, a style and a stigma. Two or more of these reproductive units may be merged to form a single compound pistil, the fused carpels forming an ovary. Within the carpels are ovules which develop into seeds after fertilization. The male parts of the flower are the stamens: these consist of long filaments arranged between the pistil and the petals that produce pollen in anthers at their tips. When a pollen grain lands upon the stigma on top of a carpel’s style, it germinates to produce a pollen tube that grows down through the tissues of the style into the carpel, where it delivers male gamete nuclei to fertilize an ovule that eventually develops into a seed.

Some hermaphroditic plants are self-fertile, but plants have evolved multiple different self-incompatibility mechanisms to avoid self-fertilization, involving sequential hermaphroditism, molecular recognition systems and morphological mechanisms such as heterostyly.[20]: 73, 74

In pines and other conifers, the sex organs are produced within cones that have male and female forms. Male cones are smaller than female ones and produce pollen, which is transported by wind to land in female cones. The larger and longer-lived female cones are typically more durable, and contain ovules within them that develop into seeds after fertilization.

Because seed plants are immobile, they depend upon passive methods for transporting pollen grains to other plants. Many, including conifers and grasses, produce lightweight pollen which is carried by wind to neighboring plants. Some flowering plants have heavier, sticky pollen that is specialized for transportation by insects or larger animals such as hummingbirds and bats, which may be attracted to flowers containing rewards of nectar and pollen. These animals transport the pollen as they move to other flowers, which also contain female reproductive organs, resulting in pollination.

Fungi

Mushrooms are produced as part of fungal sexual reproduction

Most fungi reproduce sexually and have both haploid and diploid stages in their life cycles. These fungi are typically isogamous, lacking male and female specialization: haploid fungi grow into contact with each other and then fuse their cells. In some of these cases, the fusion is asymmetric, and the cell which donates only a nucleus (and not accompanying cellular material) could arguably be considered «male».[21] Fungi may also have more complex allelic mating systems, with other sexes not accurately described as male, female, or hermaphroditic.[22]

Some fungi, including baker’s yeast, have mating types that create a duality similar to male and female roles. Yeast with the same mating type will not fuse with each other to form diploid cells, only with yeast carrying the other mating type.[23]

Many species of higher fungi produce mushrooms as part of their sexual reproduction. Within the mushroom, diploid cells are formed, later dividing into haploid spores. The height of the mushroom aids in the dispersal of these sexually produced offspring.[citation needed]

Sexual systems

A sexual system is a distribution of male and female functions across organisms in a species.[24]

Animals

Approximately 95% of animal species have separate male and female individuals, and are said to be gonochoric. About 5% of animal species are hermaphroditic.[24] This low percentage is due to the very large number of insect species, in which hermaphroditism is absent.[25] About 99% of vertebrates are gonochoric, and the remaining 1% that are hermaphroditic are almost all fishes.[26]

Plants

The majority of plants are bisexual,[27]: 212 either hermaphrodite (with both stamens and pistil in the same flower) or monoecious.[28][29] In dioecious species male and female sexes are on separate plants.[30] About 5% of flowering plants are dioecious, resulting from as many as 5000 independent origins.[31] Dioecy is common in gymnosperms, in which about 65% of species are dioecious, but most conifers are monoecious.[32]

Evolution of sex

Different forms of anisogamy:

A) anisogamy of motile cells, B) oogamy (egg cell and sperm cell), C) anisogamy of non-motile cells (egg cell and spermatia).

Different forms of isogamy:

A) isogamy of motile cells, B) isogamy of non-motile cells, C) conjugation.

It is generally accepted that isogamy was ancestral to anisogamy[33] and that anisogamy evolved several times independently in different groups of eukaryotes, including protists, algae, plants, and animals.[25] The evolution of anisogamy is synonymous with the origin of male and the origin of female.[34] It is also the first step towards sexual dimorphism[35] and influenced the evolution of various sex differences.[36]

However, the evolution of anisogamy has left no fossil evidence[37] and until 2006 there was no genetic evidence for the evolutionary link between sexes and mating types.[38] It is unclear whether anisogamy first led to the evolution of hermaphroditism or the evolution of gonochorism.[27]: 213

But a 1.2 billion year old fossil from Bangiomorpha pubescens has provided the oldest fossil record for the differentiation of male and female reproductive types and shown that sexes evolved early in eukaryotes.[39]

The original form of sex was external fertilization. Internal fertilization, or sex as we know it, evolved later[40] and became dominant for vertebrates after their emergence on land.[41]

Sex-determination systems

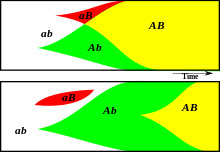

Sex helps the spread of advantageous traits through recombination. The diagrams compare the evolution of allele frequency in a sexual population (top) and an asexual population (bottom). The vertical axis shows frequency and the horizontal axis shows time. The alleles a/A and b/B occur at random. The advantageous alleles A and B, arising independently, can be rapidly combined by sexual reproduction into the most advantageous combination AB. Asexual reproduction takes longer to achieve this combination because it can only produce AB if A arises in an individual which already has B or vice versa.

The biological cause of an organism developing into one sex or the other is called sex determination. The cause may be genetic, environmental, haplodiploidy, or multiple factors.[25] Within animals and other organisms that have genetic sex-determination systems, the determining factor may be the presence of a sex chromosome. In plants that are sexually dimorphic, such as Ginkgo biloba,[20]: 203 the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha or the dioecious species in the flowering plant genus Silene, sex may also be determined by sex chromosomes.[42] Non-genetic systems may use environmental cues, such as the temperature during early development in crocodiles, to determine the sex of the offspring.[43]

Sex determination is often distinct from sex differentiation. Sex determination is the designation for the development stage towards either male or female while sex differentiation is the pathway towards the development of the phenotype.[44]

Genetic

XY sex determination

Humans and most other mammals have an XY sex-determination system: the Y chromosome carries factors responsible for triggering male development, making XY sex determination mostly based on the presence or absence of the Y chromosome. It is the male gamete that determines the sex of the offspring.[45] In this system XX mammals typically are female and XY typically are male.[25] However, individuals with XXY or XYY are males, while individuals with X and XXX are females.[7] Unusually, the platypus, a monotreme mammal, has ten sex chromosomes; females have ten X chromosomes, and males have five X chromosomes and five Y chromosomes. Platypus egg cells all have five X chromosomes, whereas sperm cells can either have five X chromosomes or five Y chromosomes.[46]

XY sex determination is found in other organisms, including insects like the common fruit fly,[47] and some plants.[48] In some cases, it is the number of X chromosomes that determines sex rather than the presence of a Y chromosome.[7] In the fruit fly individuals with XY are male and individuals with XX are female; however, individuals with XXY or XXX can also be female, and individuals with X can be males.[49]

ZW sex determination

In birds, which have a ZW sex-determination system, the W chromosome carries factors responsible for female development, and default development is male.[50] In this case, ZZ individuals are male and ZW are female. It is the female gamete that determines the sex of the offspring. This system is used by birds, some fish, and some crustaceans.[7]

The majority of butterflies and moths also have a ZW sex-determination system. Females can have Z, ZZW, and even ZZWW.[51]

XO sex determination

In the X0 sex-determination system, males have one X chromosome (X0) while females have two (XX). All other chromosomes in these diploid organisms are paired, but organisms may inherit one or two X chromosomes. This system is found in most arachnids, insects such as silverfish (Apterygota), dragonflies (Paleoptera) and grasshoppers (Exopterygota), and some nematodes, crustaceans, and gastropods.[52][53]

In field crickets, for example, insects with a single X chromosome develop as male, while those with two develop as female.[54]

In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, most worms are self-fertilizing hermaphrodites with an XX karyotype, but occasional abnormalities in chromosome inheritance can give rise to individuals with only one X chromosome—these X0 individuals are fertile males (and half their offspring are male).[55]

ZO sex determination

In the Z0 sex-determination system, males have two Z chromosomes whereas females have one. This system is found in several species of moths.[56]

Environmental

For many species, sex is not determined by inherited traits,[citation needed] but instead by environmental factors such as temperature experienced during development or later in life.[citation needed]

In the fern Ceratopteris and other homosporous fern species, the default sex is hermaphrodite, but individuals which grow in soil that has previously supported hermaphrodites are influenced by the pheromone antheridiogen to develop as male.[57] The bonelliidae larvae can only develop as males when they encounter a female.[25]

Sequential hermaphroditism

Clownfishes are initially male; the largest fish in a group becomes female

Some species can change sex over the course of their lifespan, a phenomenon called sequential hermaphroditism.[58] Teleost fishes are the only vertebrate lineage where sequential hermaphroditism occurs. In clownfish, smaller fish are male, and the dominant and largest fish in a group becomes female; when a dominant female is absent, then her partner changes sex.[clarification needed] In many wrasses the opposite is true—the fish are initially female and become male when they reach a certain size.[59] Sequential hermaphroditism also occurs in plants such as Arisaema triphyllum.

Temperature-dependent sex determination

Many reptiles, including all crocodiles and most turtles, have temperature-dependent sex determination. In these species, the temperature experienced by the embryos during their development determines their sex.[25] In some turtles, for example, males are produced at lower temperatures than females; but Macroclemys females are produced at temperatures lower than 22 °C or above 28 °C, while males are produced in between those temperatures.[60]

Haplodiploidy

Other insects,[clarification needed] including honey bees and ants, use a haplodiploid sex-determination system.[61] Diploid bees and ants are generally female, and haploid individuals (which develop from unfertilized eggs) are male. This sex-determination system results in highly biased sex ratios, as the sex of offspring is determined by fertilization (arrhenotoky or pseudo-arrhenotoky resulting in males) rather than the assortment of chromosomes during meiosis.[62]

Sex ratio

A sex ratio is the ratio of males to females in a population. As explained by Fisher’s principle, for evolutionary reasons this is typically about 1:1 in species which reproduce sexually.[63][64] However, many species deviate from an even sex ratio, either periodically or permanently. Examples include parthenogenic species, periodically mating organisms such as aphids, some eusocial wasps, bees, ants, and termites.[65]

The human sex ratio is of particular interest to anthropologists and demographers. In human societies, sex ratios at birth may be considerably skewed by factors such as the age of mother at birth[66] and by sex-selective abortion and infanticide. Exposure to pesticides and other environmental contaminants may be a significant contributing factor as well.[67] As of 2014, the global sex ratio at birth is estimated at 107 boys to 100 girls (1,000 boys per 934 girls).[68].

Sex differences

Anisogamy is the fundamental difference between male and female.[69][70] Richard Dawkins has stated that it is possible to interpret all the differences between the sexes as stemming from this.[71]

Sex differences in humans include a generally larger size and more body hair in men, while women have larger breasts, wider hips, and a higher body fat percentage. In other species, there may be differences in coloration or other features, and may be so pronounced that the different sexes may be mistaken for two entirely different taxa.[72]

Sexual dimorphism

In many animals and some plants, individuals of male and female sex differ in size and appearance, a phenomenon called sexual dimorphism.[73] Sexual dimorphism in animals is often associated with sexual selection—the mating competition between individuals of one sex vis-à-vis the opposite sex.[72] In many cases, the male of a species is larger than the female. Mammal species with extreme sexual size dimorphism tend to have highly polygynous mating systems—presumably due to selection for success in competition with other males—such as the elephant seals. Other examples demonstrate that it is the preference of females that drives sexual dimorphism, such as in the case of the stalk-eyed fly.[74]

Females are the larger sex in a majority of animals.[73] For instance, female southern black widow spiders are typically twice as long as the males.[75] This size disparity may be associated with the cost of producing egg cells, which requires more nutrition than producing sperm: larger females are able to produce more eggs.[76][73]

Sexual dimorphism can be extreme, with males, such as some anglerfish, living parasitically on the female. Some plant species also exhibit dimorphism in which the females are significantly larger than the males, such as in the moss genus Dicranum[77] and the liverwort genus Sphaerocarpos.[78] There is some evidence that, in these genera, the dimorphism may be tied to a sex chromosome,[78][79] or to chemical signalling from females.[80]

In birds, males often have a more colorful appearance and may have features (like the long tail of male peacocks) that would seem to put them at a disadvantage (e.g. bright colors would seem to make a bird more visible to predators). One proposed explanation for this is the handicap principle.[81] This hypothesis argues that, by demonstrating he can survive with such handicaps, the male is advertising his genetic fitness to females—traits that will benefit daughters as well, who will not be encumbered with such handicaps.

Sexual characteristics

Sex differences in behavior

The sexes across gonochoric species usually differ in behavior. In most animal species females invest more in parental care,[82] although in some species, such as some coucals, the males invest more parental care.[83] Females also tend to be more choosy for who they mate with,[84] such as most bird species.[85] Males tend to be more competitive for mating than females.[34]

See also

- Mating type

- Sexing

- Sex allocation

- Sex and gender distinction

- Sex assignment

- Sex organ

References

- ^ Stevenson A, Waite M (2011). Concise Oxford English Dictionary: Book & CD-ROM Set. OUP Oxford. p. 1302. ISBN 978-0-19-960110-3. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

Sex: Either of the two main categories (male and female) into which humans and most other living things are divided on the basis of their reproductive functions. The fact of belonging to one of these categories. The group of all members of either sex.

- ^ a b Purves WK, Sadava DE, Orians GH, Heller HC (2000). Life: The Science of Biology. Macmillan. p. 736. ISBN 978-0-7167-3873-2. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

A single body can function as both male and female. Sexual reproduction requires both male and female haploid gametes. In most species, these gametes are produced by individuals that are either male or female. Species that have male and female members are called dioecious (from the Greek for ‘two houses’). In some species, a single individual may possess both female and male reproductive systems. Such species are called monoecious («one house») or hermaphroditic.

- ^ Royle NJ, Smiseth PT, Kölliker M (9 August 2012). Kokko H, Jennions M (eds.). The Evolution of Parental Care. Oxford University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-19-969257-6.

The answer is that there is an agreement by convention: individuals producing the smaller of the two gamete types-sperm or pollen- are males, and those producing larger gametes-eggs or ovules- are females.

- ^ Avise JC (18 March 2011). Hermaphroditism: A Primer on the Biology, Ecology, and Evolution of Dual Sexuality. Columbia University Press. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-0-231-52715-6. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ Moore D, Robson JD, Trinci AP (2020). 21st Century guidebook to fungi (2 ed.). Cambridge University press. pp. 211–228. ISBN 978-1-108-74568-0.

- ^ Kumar R, Meena M, Swapnil P (2019). «Anisogamy». In Vonk J, Shackelford T (eds.). Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_340-1. ISBN 978-3-319-47829-6.

Anisogamy can be defined as a mode of sexual reproduction in which fusing gametes, formed by participating parents, are dissimilar in size.

- ^ a b c d Hake L, O’Connor C. «Genetic Mechanisms of Sex Determination | Learn Science at Scitable». www.nature.com. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ Alberts et al. (2002), «V. 20. Meiosis», U.S. NIH, V. 20. Meiosis Archived 25 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alberts et al. (2002), U.S. National Institutes of Health, «V. 20. The Benefits of Sex Archived 22 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine».

- ^ Gilbert (2000), «1.2. Multicellularity: Evolution of Differentiation». 1.2.Mul Archived 8 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, NIH.

- ^ Allaby M (29 March 2012). A Dictionary of Plant Sciences. OUP Oxford. p. 350. ISBN 978-0-19-960057-1.

- ^ Gee, Henry (22 November 1999). «Size and the single sex cell». Nature. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ Alberts et al. (2002), «3. Mendelian genetics in eukaryotic life cycles», U.S. NIH, 3. Mendelian/eukaryotic Archived 2 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Alberts et al. (2002), «V.20. Sperm», U.S. NIH, V.20. Sperm Archived 29 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Alberts et al. (2002), «V.20. Eggs», U.S. NIH, V.20. Eggs Archived 29 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Alberts et al. (2002), «V.20. Fertilization», U.S. NIH, V.20. Fertilization Archived 19 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Ritchison, G. «Avian Reproduction». Eastern Kentucky University. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- ^ Gilbert SF (2000). «Gamete Production in Angiosperms». Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-243-6.

- ^ Dusenbery DB (2009). Living at Micro Scale: The Unexpected Physics of Being Small. Harvard University Press. pp. 308–326. ISBN 978-0-674-03116-6.

- ^ a b Judd, Walter S.; Campbell, Christopher S.; Kellogg, Elizabeth A.; Stevens, Peter F.; Donoghue, Michael J. (2002). Plant systematics, a phylogenetic approach (2 ed.). Sunderland MA, US: Sinauer Associates Inc. ISBN 0-87893-403-0.

- ^ Nick Lane (2005). Power, Sex, Suicide: Mitochondria and the Meaning of Life. Oxford University Press. pp. 236–237. ISBN 978-0-19-280481-5.

- ^ Watkinson SC, Boddy L, Money N (2015). The Fungi. Elsevier Science. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-12-382035-8. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Matthew P. Scott; Paul Matsudaira; Harvey Lodish; James Darnell; Lawrence Zipursky; Chris A. Kaiser; Arnold Berk; Monty Krieger (2000). Molecular Cell Biology (Fourth ed.). WH Freeman and Co. ISBN 978-0-7167-4366-8.14.1. Cell-Type Specification and Mating-Type Conversion in Yeast Archived 1 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Leonard, J. L. (22 August 2013). «Williams’ Paradox and the Role of Phenotypic Plasticity in Sexual Systems». Integrative and Comparative Biology. 53 (4): 671–688. doi:10.1093/icb/ict088. ISSN 1540-7063. PMID 23970358.

- ^ a b c d e f Bachtrog D, Mank JE, Peichel CL, Kirkpatrick M, Otto SP, Ashman TL, et al. (July 2014). «Sex determination: why so many ways of doing it?». PLOS Biology. 12 (7): e1001899. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001899. PMC 4077654. PMID 24983465.

- ^ Kuwamura T, Sunobe T, Sakai Y, Kadota T, Sawada K (1 July 2020). «Hermaphroditism in fishes: an annotated list of species, phylogeny, and mating system». Ichthyological Research. 67 (3): 341–360. doi:10.1007/s10228-020-00754-6. ISSN 1616-3915. S2CID 218527927.

- ^ a b Kliman, Richard (2016). Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Biology. Vol. 2. Academic Press. pp. 212–224. ISBN 978-0-12-800426-5. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Sabath N, Goldberg EE, Glick L, Einhorn M, Ashman TL, Ming R, et al. (February 2016). «Dioecy does not consistently accelerate or slow lineage diversification across multiple genera of angiosperms». The New Phytologist. 209 (3): 1290–300. doi:10.1111/nph.13696. PMID 26467174.

- ^ Beentje H (2016). The Kew plant glossary (2 ed.). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Kew Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84246-604-9.

- ^ Leite Montalvão, Ana Paula; Kersten, Birgit; Fladung, Matthias; Müller, Niels Andreas (2021). «The Diversity and Dynamics of Sex Determination in Dioecious Plants». Frontiers in Plant Science. 11: 580488. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.580488. ISSN 1664-462X. PMC 7843427. PMID 33519840.

- ^ Renner, Susanne S. (2014). «The relative and absolute frequencies of angiosperm sexual systems: dioecy, monoecy, gynodioecy, and an updated online database». American Journal of Botany. 101 (10): 1588–1596. doi:10.3732/ajb.1400196. PMID 25326608.

- ^ Walas Ł, Mandryk W, Thomas PA, Tyrała-Wierucka Ż, Iszkuło G (2018). «Sexual systems in gymnosperms: A review» (PDF). Basic and Applied Ecology. 31: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.baae.2018.05.009. S2CID 90740232.

- ^ Kumar, Awasthi & Ashok. Textbook of Algae. Vikas Publishing House. p. 363. ISBN 978-93-259-9022-7.

- ^ a b Lehtonen J, Kokko H, Parker GA (October 2016). «What do isogamous organisms teach us about sex and the two sexes?». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1706). doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0532. PMC 5031617. PMID 27619696.

- ^ Togashi, Tatsuya; Bartelt, John L.; Yoshimura, Jin; Tainaka, Kei-ichi; Cox, Paul Alan (21 August 2012). «Evolutionary trajectories explain the diversified evolution of isogamy and anisogamy in marine green algae». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (34): 13692–13697. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10913692T. doi:10.1073/pnas.1203495109. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3427103. PMID 22869736.

- ^ Székely, Tamás; Fairbairn, Daphne J.; Blanckenhorn, Wolf U. (5 July 2007). Sex, Size and Gender Roles: Evolutionary Studies of Sexual Size Dimorphism. OUP Oxford. pp. 167–169, 176, 185. ISBN 978-0-19-920878-4.

- ^ Pitnick SS, Hosken DJ, Birkhead TR (21 November 2008). Sperm Biology: An Evolutionary Perspective. Academic Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-08-091987-4.

- ^ Sawada, Hitoshi; Inoue, Naokazu; Iwano, Megumi (7 February 2014). Sexual Reproduction in Animals and Plants. Springer. pp. 215–216. ISBN 978-4-431-54589-7.

- ^ Hörandl, Elvira; Hadacek, Franz (15 August 2020). «Oxygen, life forms, and the evolution of sexes in multicellular eukaryotes». Heredity. 125 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1038/s41437-020-0317-9. ISSN 1365-2540. PMC 7413252. PMID 32415185.

- ^ Riley Black, «Armored Fish Pioneered Sex As You Know It,» National Geographic, October 19, 2014, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/141019-fossil-fish-evolution-sex-fertilization Archived 23 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «43.2A: External and Internal Fertilization». Biology LibreTexts. 17 July 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ Tanurdzic M, Banks JA (2004). «Sex-determining mechanisms in land plants». The Plant Cell. 16 Suppl (Suppl): S61-71. doi:10.1105/tpc.016667. PMC 2643385. PMID 15084718.

- ^ Warner DA, Shine R (January 2008). «The adaptive significance of temperature-dependent sex determination in a reptile». Nature. 451 (7178): 566–8. Bibcode:2008Natur.451..566W. doi:10.1038/nature06519. PMID 18204437. S2CID 967516.

- ^ Beukeboom LW, Perrin N (2014). The Evolution of Sex Determination. Oxford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-19-965714-8.

- ^ Wallis MC, Waters PD, Graves JA (October 2008). «Sex determination in mammals—before and after the evolution of SRY». Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 65 (20): 3182–95. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-8109-z. PMID 18581056. S2CID 31675679.

- ^ Pierce, Benjamin A. (2012). Genetics: a conceptual approach (4th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-1-4292-3250-0. OCLC 703739906.

- ^ Kaiser VB, Bachtrog D (2010). «Evolution of sex chromosomes in insects». Annual Review of Genetics. 44: 91–112. doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163600. PMC 4105922. PMID 21047257.

- ^ Dellaporta SL, Calderon-Urrea A (October 1993). «Sex determination in flowering plants». The Plant Cell. 5 (10): 1241–51. doi:10.1105/tpc.5.10.1241. JSTOR 3869777. PMC 160357. PMID 8281039.

- ^ Fusco G, Minelli A (10 October 2019). The Biology of Reproduction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 306–308. ISBN 978-1-108-49985-9.

- ^ Smith CA, Katz M, Sinclair AH (February 2003). «DMRT1 is upregulated in the gonads during female-to-male sex reversal in ZW chicken embryos». Biology of Reproduction. 68 (2): 560–70. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.102.007294. PMID 12533420.

- ^ Majerus ME (2003). Sex Wars: Genes, Bacteria, and Biased Sex Ratios. Princeton University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-691-00981-0.

- ^ Bull JJ (1983). Evolution of sex determining mechanisms. p. 17. ISBN 0-8053-0400-2.

- ^ Thiriot-Quiévreux C (2003). «Advances in chromosomal studies of gastropod molluscs». Journal of Molluscan Studies. 69 (3): 187–202. doi:10.1093/mollus/69.3.187.

- ^ Yoshimura A (2005). «Karyotypes of two American field crickets: Gryllus rubens and Gryllus sp. (Orthoptera: Gryllidae)». Entomological Science. 8 (3): 219–222. doi:10.1111/j.1479-8298.2005.00118.x. S2CID 84908090.

- ^ Meyer BJ (1997). «Sex Determination and X Chromosome Dosage Compensation: Sexual Dimorphism». In Riddle DL, Blumenthal T, Meyer BJ, Priess JR (eds.). C. elegans II. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-532-3.

- ^ Handbuch Der Zoologie / Handbook of Zoology. Walter de Gruyter. 1925. ISBN 978-3-11-016210-3. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Tanurdzic M, Banks JA (2004). «Sex-determining mechanisms in land plants». The Plant Cell. 16 Suppl (Suppl): S61-71. doi:10.1105/tpc.016667. PMC 2643385. PMID 15084718.

- ^ Fusco G, Minelli A (10 October 2019). The Biology of Reproduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-108-49985-9.

- ^ Todd EV, Liu H, Muncaster S, Gemmell NJ (2016). «Bending Genders: The Biology of Natural Sex Change in Fish». Sexual Development. 10 (5–6): 223–241. doi:10.1159/000449297. PMID 27820936. S2CID 41652893.

- ^ Gilbert SF (2000). «Environmental Sex Determination». Developmental Biology. 6th Edition.

- ^ Charlesworth B (August 2003). «Sex determination in the honeybee». Cell. 114 (4): 397–8. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00610-X. PMID 12941267.

- ^ de la Filia A, Bain S, Ross L (June 2015). «Haplodiploidy and the reproductive ecology of Arthropods» (PDF). Current Opinion in Insect Science. 9: 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.cois.2015.04.018. hdl:20.500.11820/b540f12f-846d-4a5a-9120-7b2c45615be6. PMID 32846706. S2CID 83988416.

- ^ Fisher, R. A. (1930). The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 141–143 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Hamilton, W. D. (1967). «Extraordinary Sex Ratios: A Sex-ratio Theory for Sex Linkage and Inbreeding Has New Implications in Cytogenetics and Entomology». Science. 156 (3774): 477–488. Bibcode:1967Sci…156..477H. doi:10.1126/science.156.3774.477. JSTOR 1721222. PMID 6021675.

- ^ Kobayashi, Kazuya; Hasegawa, Eisuke; Yamamoto, Yuuka; Kazutaka, Kawatsu; Vargo, Edward L.; Yoshimura, Jin; Matsuura, Kenji (2013). «Sex ratio biases in termites provide evidence for kin selection». Nat Commun. 4: 2048. Bibcode:2013NatCo…4.2048K. doi:10.1038/ncomms3048. PMID 23807025.

- ^ «Trend Analysis of the sex Ratio at Birth in the United States» (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics.

- ^ Davis, Devra Lee; Gottlieb, Michelle and Stampnitzky, Julie; «Reduced Ratio of Male to Female Births in Several Industrial Countries» in Journal of the American Medical Association; April 1, 1998, volume 279(13); pp. 1018-1023

- ^ «CIA Fact Book». The Central Intelligence Agency of the United States. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007.

- ^ Whitfield J (June 2004). «Everything you always wanted to know about sexes». PLOS Biology. 2 (6): e183. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020183. PMC 423151. PMID 15208728.

One thing biologists do agree on is that males and females count as different sexes. And they also agree that the main difference between the two is gamete size: males make lots of small gametes—sperm in animals, pollen in plants—and females produce a few big eggs.

- ^ Pierce BA (2012). Genetics: A Conceptual Approach. W. H. Freeman. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4292-3252-4.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (2016). The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0-19-878860-7.

However, there is one fundamental feature of the sexes which can be used to label males as males, and females as females, throughout animals and plants. This is that the sex cells or ‘gametes’ of males are much smaller and more numerous than the gametes of females. This is true whether we are dealing with animals or plants. One group of individuals has large sex cells, and it is convenient to use the word female for them. The other group, which it is convenient to call male, has small sex cells. The difference is especially pronounced in reptiles and in birds, where a single egg cell is big enough and nutritious enough to feed a developing baby for. Even in humans, where the egg is microscopic, it is still many times larger than the sperm. As we shall see, it is possible to interpret all the other differences between the sexes as stemming from this one basic difference.

- ^ a b Mori, Emiliano; Mazza, Giuseppe; Lovari, Sandro (2017). «Sexual Dimorphism». In Vonk, Jennifer; Shackelford, Todd (eds.). Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–7. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_433-1. ISBN 978-3-319-47829-6. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Choe J (21 January 2019). «Body Size and Sexual Dimorphism». In Cox R (ed.). Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior. Vol. 2. Academic Press. pp. 7–11. ISBN 978-0-12-813252-4.

- ^ Wilkinson GS, Reillo PR (22 January 1994). «Female choice response to artificial selection on an exaggerated male trait in a stalk-eyed fly» (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 225 (1342): 1–6. Bibcode:1994RSPSB.255….1W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.574.2822. doi:10.1098/rspb.1994.0001. S2CID 5769457. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2006.

- ^ Drees BM, Jackman J (1999). «Southern black widow spider». Field Guide to Texas Insects. Houston, Texas: Gulf Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 31 August 2003. Retrieved 8 August 2012 – via Extension Entomology, Insects.tamu.edu, Texas A&M University.

- ^ Stuart-Smith J, Swain R, Stuart-Smith R, Wapstra E (2007). «Is fecundity the ultimate cause of female-biased size dimorphism in a dragon lizard?». Journal of Zoology. 273 (3): 266–272. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00324.x.

- ^ Shaw AJ (2000). «Population ecology, population genetics, and microevolution». In Shaw AJ, Goffinet B (eds.). Bryophyte Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 379–380. ISBN 978-0-521-66097-6.

- ^ a b Schuster RM (1984). «Comparative Anatomy and Morphology of the Hepaticae». New Manual of Bryology. Vol. 2. Nichinan, Miyazaki, Japan: The Hattori botanical Laboratory. p. 891.

- ^ Crum HA, Anderson LE (1980). Mosses of Eastern North America. Vol. 1. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-231-04516-2.

- ^ Briggs DA (1965). «Experimental taxonomy of some British species of genus Dicranum«. New Phytologist. 64 (3): 366–386. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1965.tb07546.x.

- ^ Zahavi A, Zahavi A (1997). The handicap principle: a missing piece of Darwin’s puzzle. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510035-8.

- ^ Kliman, Richard (14 April 2016). Herridge, Elizabeth J; Murray, Rosalind L; Gwynne, Darryl T; Bussiere, Luc (eds.). Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Biology. Vol. 2. Academic Press. pp. 453–454. ISBN 978-0-12-800426-5.

- ^ Henshaw, Jonathan M.; Fromhage, Lutz; Jones, Adam G. (28 August 2019). «Sex roles and the evolution of parental care specialization». Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1909): 20191312. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.1312. PMC 6732396. PMID 31455191.

- ^ «Sexual Selection | Learn Science at Scitable». www.nature.com. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ Reboreda, Juan Carlos; Fiorini, Vanina Dafne; Tuero, Diego Tomás (24 April 2019). Behavioral Ecology of Neotropical Birds. Springer. p. 75. ISBN 978-3-030-14280-3.

Further reading

- Arnqvist G, Rowe L (2005). Sexual conflict. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12217-5.

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3.

- Ellis H (1933). Psychology of Sex. London: W. Heinemann Medical Books. N.B.: One of many books by this pioneering authority on aspects of human sexuality.

- Gilbert SF (2000). Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates, Inc. ISBN 978-0-87893-243-6.

- Maynard-Smith J (1978). The Evolution of Sex. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29302-0.

External links

This audio file was created from a revision of this article dated 29 December 2022, and does not reflect subsequent edits.

- Human Sexual Differentiation Archived 9 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine by P. C. Sizonenko

-

Defenition of the word sex

- Either of two main divisions (either male or female) into which many organisms can be placed, according to reproductive function or organs.

- The act of sexual intercourse.

- arouse sexually

- either of the two categories (male or female) into which most organisms are divided; «the war between the sexes»

- tell the sex (of young chickens)

- the properties that distinguish organisms on the basis of their reproductive roles; «she didn’t want to know the sex of the foetus»

- all of the feelings resulting from the urge to gratify sexual impulses; «he wanted a better sex life»; «the film contained no sex or violence»

- activities associated with sexual intercourse; «they had sex in the back seat»

- the properties that distinguish organisms on the basis of their reproductive roles; «she didn»t want to know the sex of the foetus»

- stimulate sexually; «This movie usually arouses the male audience»

- activities associated with sexual intercourse

- the properties that distinguish organisms on the basis of their reproductive roles

- all of the feelings resulting from the urge to gratify sexual impulses

- either of the two categories (male or female) into which most organisms are divided

- stimulate sexually

Synonyms for the word sex

-

- arouse

- excite

- gender

- sex activity

- sexual activity

- sexual urge

- sexuality

- turn on

- wind up

Hyponyms for the word sex

-

- androgyny

- arousal

- autoeroticism

- autoerotism

- bestiality

- bisexuality

- bondage

- breeding

- carnal abuse

- carnal knowledge

- coition

- coitus

- conception

- congress

- conjugation

- copulation

- coupling

- facts of life

- femaleness

- feminineness

- foreplay

- gayness

- hermaphroditism

- heterosexualism

- heterosexuality

- homoeroticism

- homosexualism

- homosexuality

- intercourse

- lechery

- love

- love life

- lovemaking

- making love

- maleness

- masculinity

- mating

- outercourse

- pairing

- perversion

- pleasure

- procreation

- promiscuity

- promiscuousness

- queerness

- relation

- reproduction

- safe sex

- sex act

- sexual congress

- sexual intercourse

- sexual love

- sexual perversion

- sexual relation

- sexual union

- sleeping around

- stimulation

- straightness

- tempt

- union

- zooerastia

- zooerasty

Hypernyms for the word sex

-

- activity

- bodily function

- bodily process

- body process

- category

- class

- differentiate

- distinguish

- excite

- family

- feeling

- physiological property

- secern

- secernate

- separate

- severalise

- severalize

- shake

- shake up

- stimulate

- stir

- tell

- tell apart

See other words

-

- What is telo jelo

- The definition of bosun

- The interpretation of the word scurvy

- What is meant by bite

- The lexical meaning all

- The dictionary meaning of the word fish

- The grammatical meaning of the word twelve

- Meaning of the word pilot

- Literal and figurative meaning of the word penury

- The origin of the word argelia

- Synonym for the word algerium

- Antonyms for the word pa

- Homonyms for the word beso

- Hyponyms for the word osculum

- Holonyms for the word suavium

- Hypernyms for the word beijo

- Proverbs and sayings for the word kiso

- Translation of the word in other languages lebertran

- Top Definitions

- Quiz

- Related Content

- Examples

- British

- Scientific

- Idioms And Phrases

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

noun

the male, female, or sometimes intersex division of a species, especially as differentiated with reference to the reproductive functions or physical characteristics such as genitals, XX and XY chromosomes, etc.

a label assigned to a person at birth, usually male or female and sometimes intersex, and typically based on genital configuration.See Usage note at the current entry.

the sum of the structural and functional differences by which male, female, and sometimes intersex organisms are distinguished, or the phenomena or behavior dependent on these differences: These plants change sex depending on how much light they receive.

the sexual instinct or attraction drawing one organism toward another, or its manifestation in life and conduct: choosing a life partner based on sex.

sexual relations or activity, especially sexual intercourse: young kids learning about sex.

the genitals; genitalia: A towel was hiding his sex from view.

verb (used with object)