I

The term set expression is the most definite and the most suitable one in comparison with phraseology and idiom and phrase, because the first element points out the most important characteristics of these units, their stability and their ready made nature.

Every utterance is a patterned, rhythmed, segmented sequence of signals. On the lexical level, these signals building up the utterance are not exclusively words. Speakers may use larger blocks consisting of more than one word but functioning as a whole. These set expressions are extremely variegated structurally, functionally, semantically and stylistically. To this type may be referred expressive colloquialisms: a sight for sore eye, and also terms like: blank verse, direct object, political clichés: round-table conference, summit meeting and emotionally and stylistically neutral collocations: in front of, as well as, a great deal, give up, etc.

Even this list of expressions illustrates that the number of elements in set expressions as well as their reference to different parts of speech varies. Set expressions are contrasted to free phrases and semi-fixed combinations. All these are but different stages of restrictions imposed upon co-occurrence of words. What is often called idiom is nothing else but restrictions imposed upon the lexical filling of structural patterns which are specific for every language.

The restrictions may be independent on the ties existing in extra-linguistic reality between the objects spoken of and be conditioned by purely linguistic factors or have extra-linguistic causes in the history of the people. In free combinations the linguistic factors are chiefly connected with grammatical properties of words.

A free phrase permits substitution of any of its elements without semantic change in the other element or elements. This substitution is never unlimited.

In semi-fixed combinations we are not only able to say that such substitutes exist, but fix their boundaries by stating the semantic properties of words that can be used for substitution or even listing them. .g. the pattern consisting of the verb go followed by a preposition and a noun with no article before it (go to school, go to court) is used only with nouns of place where definite actions or functions are performed.

If substitution is only pronominal or restricted to a few synonyms for one of the members only, or impossible, i.e. if the elements of the phrase are always the same and make a fixed context for each other the word-group is a set expression. No substitution of any elements is possible in the following unchangeable set expressions, which differ in all other respects: red tape, first night, heads or tails, to hope for the best, as busy as a bee, to and fro. No substitution is possible because it would destroy the meaning of the euphonic and expressive qualities of the whole.

These set expressions are also interesting from the point of view of their informational characteristics, i.e. the sum total of information contained in the word-group is created by mutual interaction of elements.

E.g. Heads or tails – comes from the old custom of deciding a dispute which of two possible alternatives shall be followed by tossing a coin.

In a free phrase this correlation is different and each element has a much greater semantic independence. Each component may be substituted without affecting the meaning of the other

E.g. to cut bread, to cut cheese, to eat bread.

If we take an expression to cut a poor figure – practically no substitution is possible here without ruining the meaning: E.g. I had an uneasy fear that he might cut a poor figure beside all these clever Russian officers. He was not managing to cut much of a figure. – the only substitution that is possible here concerns adjectives: poor, much of, bad. That is why it refers to semi-fixed combinations.

In the example cut no ice (to have no influence) no substitution is possible.

The give up type presents great interest from the phraseological viewpoint. An almost unlimited number of such units may be formed by the use of the simpler verbs combined with elements that have been treated as adverbs, preposition-like adverbs, postposition of adverbial origin, postpositives, postpositive prefixes.

The verbs most frequent in these units are: bear, blow, break, bring, call, take, make turn, etc.

It is more common with the verbs denoting motion: go on, go by, go ahead, go down etc.

Only combinations forming integral wholes, the meaning of which is not readily derived from the meaning of the components, so that the lexical meaning of one of the components is strongly influenced by the presence of the other, are referred to set expressions.

II

There is a necessity to distinguish between a set expression and a compound word. One of the criteria is the formal integrity of words.

E.g. the word breakfast (it is a word because – he breakfasts not breaks fast)

It is impossible to distinguish all words on this basis. Some authors point out the syntactic function, but it is not specific for all set expressions.

Two types of substitution tests can be useful in showing the points of similarity and difference between words and set expressions. In the first procedure a whole set expression is replaced within a context by a synonymous word in such a way that the meaning of the utterance remains unchanged, e.g. he was in a brown study – he was gloomy.

In the second type of substitution test only an element of the set expression is replaced, e.g. as white as chalk – as white as milk(snow). In this second type it is the set expression that is retained, although its composition or referential meaning may change.

E.g. the set expression dead beat can be substituted by a single word exhausted. This possibility permits us to regard this set expression as a word equivalent. But there are cases when substitution is not possible.

E.g. red tape can be substituted only by a free phrase ‘rigid formality of official routine’.

The main point of difference between a word and a set expression is the divisibility of the latter into separately structured elements, which is contrasted to the structural integrity of words.

Although equivalent to words in being introduced into speech ready-made, a set expression is different from them because it can be resolved into words whereas words are resolved into morphemes. In compound words the process of integration is more advanced.

16. Set expressions.

©2015- 2023 pdnr.ru Все права принадлежат авторам размещенных материалов.

Подборка по базе: СРО 2 Арнольд.docx, В. И. Арнольд. Обыкновенные дифференциальные уравнения.pdf, Kempkens Arnold — Mala moja.pdf, В И Арнольд задачи для -5-15.pdf, Теория Арнольда Тойнби.docx

§ 9.3 CLASSIFICATION OF SET EXPRESSIONS

Many various lines of approach have been used, and yet the boundaries of this set, its classification and the place of phraseology in the vocabulary appear controversial issues of present-day linguistics.

The English and- the Americans can be proud of a very rich set of dictionaries of word-groups and idiomatic phrases. Their object is chiefly practical: colloquial phrases are considered an important characteristic feature of natural spoken English and a stumbling block for foreigners. The choice of entries is not clear-cut: some dictionaries of this kind include among their entries not only word combinations but also separate words interesting from the point of view of their etymology, motivation, or expressiveness, and, on the other hand, also greetings, proverbs, familiar quotations. Other dictionaries include grammatical information. The most essential theoretical problems remain not only unsolved but untackled except in some works on general linguistics. A more or less detailed grouping was given in’the books on English idioms by L.P. Smith and W. Ball. But even the authors themselves do not claim that their groupings should be regarded as classification. They show interest in the origin and etymology of the phrases collected and arrange them accordingly into phrases from sea life, from agriculture, from sports, from hunting, etc.

The question of classification of set expressions is main I y worked out in this country. Eminent Russian linguists, Academicians F.F. For-tunatov, A.A. Shakhmatov and others paved the way for serious syntactical analysis of set expressions. Many Soviet scholars have shown a great interest in the theoretical aspects of the problem. A special branch of linguistics termed phraseology came into being in this country. The most significant theories advanced for Russian phraseology are those by S.A. Larin and V.V. Vinogradov.

169

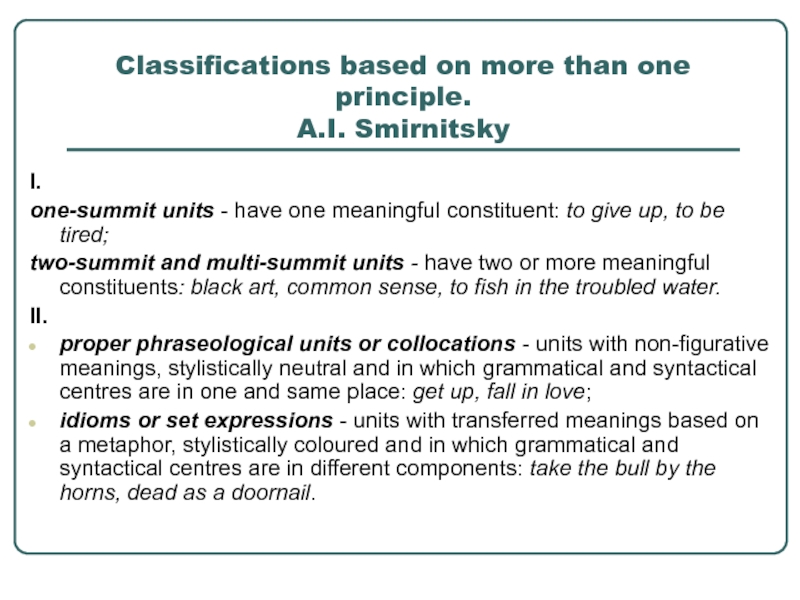

As to the English language, the number of works of our linguists devoted to phraseology is so great that it is impossible to enumerate them; suffice it to say that there exists a comprehensive dictionary of English phraseology compiled by A.V. Koonin. This dictionary sustained several editions and contains an extensive bibliography and articles on some most important problems. The first doctoral thesis on this subject was by N.N. Amosova (1963), then came the doctoral thesis by A.V. Koonin. The results were published in monographs (see the list given at the end of the book). Prof. A.I. Smirnitsky also devoted attention to this aspect in his book on lexicology. He considers a phraseological unit to be similar to the word because of the idiomatic relationships between its parts resulting in semantic unity and permitting its introduction into speech as something complete.

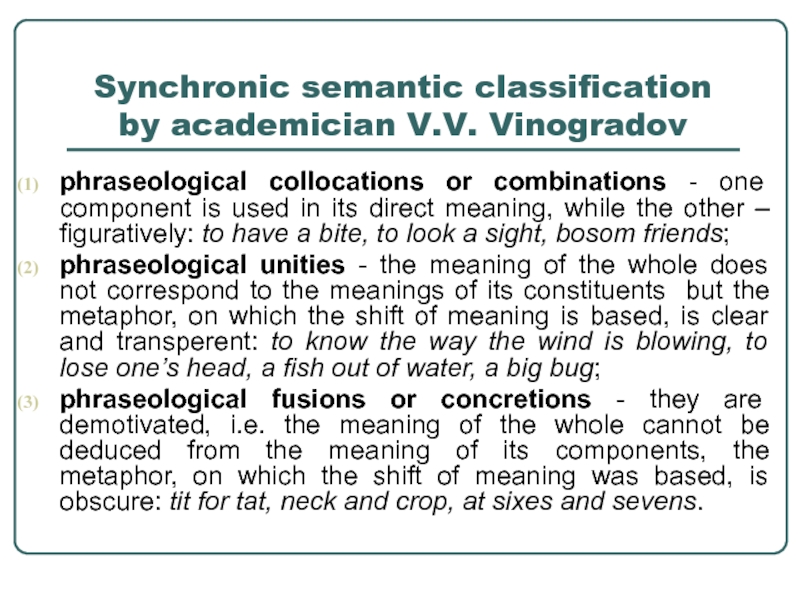

The influence his classification exercised is much smaller than that of V.V. Vinogradov’s. The classification of V.V. Vinogradov is syn-chronic. He developed some points first advanced by the Swiss linguist Charles Bally and gave a strong impetus to a purely lexicological treatment of the material. Thanks to him phraseological units were rigorously defined as lexical complexes with specific semantic features and classified accordingly. His classification is based upon the motivation of the unit, i.e. the relationship existing between the meaning of the whole and the meaning of its component parts. The degree of motivation is correlated with the rigidity, indivisibility and semantic unity of the expression, i.e with the possibility of changing the form or the order of components, and of substituting the whole by a single word. The classification is naturally developed for Russian phraseology but we shall illustrate it with English examples.

According to the type of motivation and the other above-mentioned features, three types of phraseological units are suggested: phraseological fusions, phraseological unities and phraseological combinations.

Phraseological fusions (e. g. tit for tat) represent as their name suggests the highest stage of blending together. The meaning of components is completely absorbed by the meaning of the whole, by its expressiveness and emotional properties. Phraseological fusions are specific for every language and do not lend themselves to literal translation into other languages.

Phraseological unities are much more numerous. They are clearly motivated. The emotional quality is based upon the image created by the whole as in to stick (to stand) to one’s guns, i.e. ‘refuse to change one’s statements or opinions in the face of opposition’, implying courage and integrity. The example reveals another characteristic of the type, namely the possibility of synonymic substitution, which can be only very limited. Some of these are easily translated and even international, e. g. to know the way the wind is blowing.

The third group in this classification, the phraseological combinations, are not only motivated but contain one component used in its direct meaning while the other is used figuratively: meet the demand, meet the necessity, meet the requirements. The mobil-

170

ity of this type is much greater, the substitutions are not necessarily synonymical.

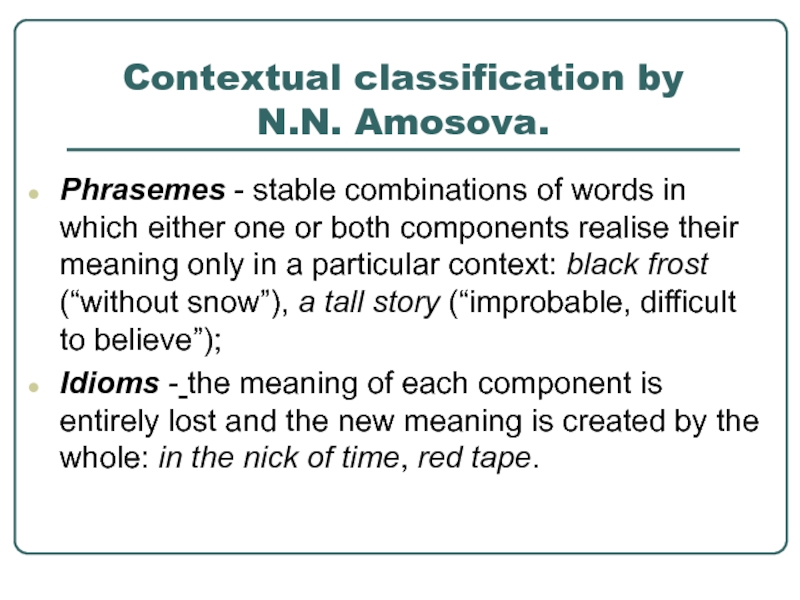

It has been pointed out by N.N. Amosova and A.V. Koonin that this classification, being developed for the Russian phraseology, does not fit the specifically English features.

N.N. Amosova’s approach is contextological. She defines phraseological units as units of fixed context. Fixed context is defined as a context characterized by a specific and unchanging sequence of definite lexical components, and a peculiar semantic relationship between them. Units of fixed context are subdivided into phra-semes and idioms. Phrasemes are always binary: one component has a phraseologically bound meaning, the other serves as the determining context (small talk, small hours, small change). In idioms the new meaning is created by the whole, though every element mtv have its original meaning weakened or even completely lost: in the nick of time ‘at the exact moment’. Idioms may be motivated or demotivated. A motivated idiom is homonymous to a free phrase, but this phrase is used figuratively: take the bull by the horns ‘to face dangers without fear’. In the nick of time is demotivated, because the word nick is obsolete. Both phrasemes and idioms may be movable (changeable) or immovable.

An interesting and clear-cut modification of V.V. Vinogradov’s scheme was suggested by T.V. Stroyeva for the German language. She divides the whole bulk of phraseological units into two classes: u n i t-i e s and combinations. Phraseological fusions do not constitute a separate class but are included into unities, because the criterion of motivation and demotivation is different for different speakers, depending on their education and erudition. The figurative meaning of a phraseological unity is created by the whole, the semantic transfer being dependent on extra-linguistic factors, i.e. the history of the people and its culture. There may occur in speech homonymous free phrases, very different in meaning (c /. jemandem den Kopf waschen ‘to scold sb’ — a phraseological unity and den Kopf waschen ‘to wash one’s head’ — a free phrase). The form and structure of a phraseological unity is rigid and unchangeable. Its stability is often supported by rhyme, synonymy, parallel construction, etc. Phraseological combinations, on the contrary, reveal a change of meaning only in one of the components and this semantic shift does not result in enhancing expressiveness.

A.V. Koonin is interested both in discussing fundamentals and in investigating special problems. His books, and especially the dictionary he compiled and also the dissertations of his numerous pupils are particularly useful as they provide an up-to-date survey of the entire field.

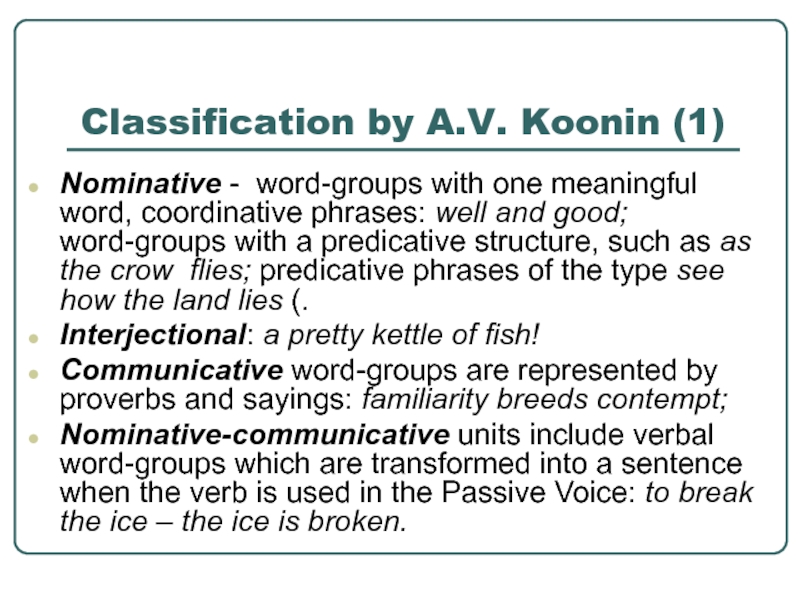

A.V. Koonin thinks that phraseology must develop as an independent linguistic science and not as a part of lexicology. His classification of phraseological units is based on the functions the units fulfill in speech. They may be

nominating (a bull in a china shop), interjectional (a pretty kettle of fishl), communicative (familiarity breeds contempt), or nominating-communicative (pull somebody’s leg). Further classification into subclasses depends on whether the units are changeable

171

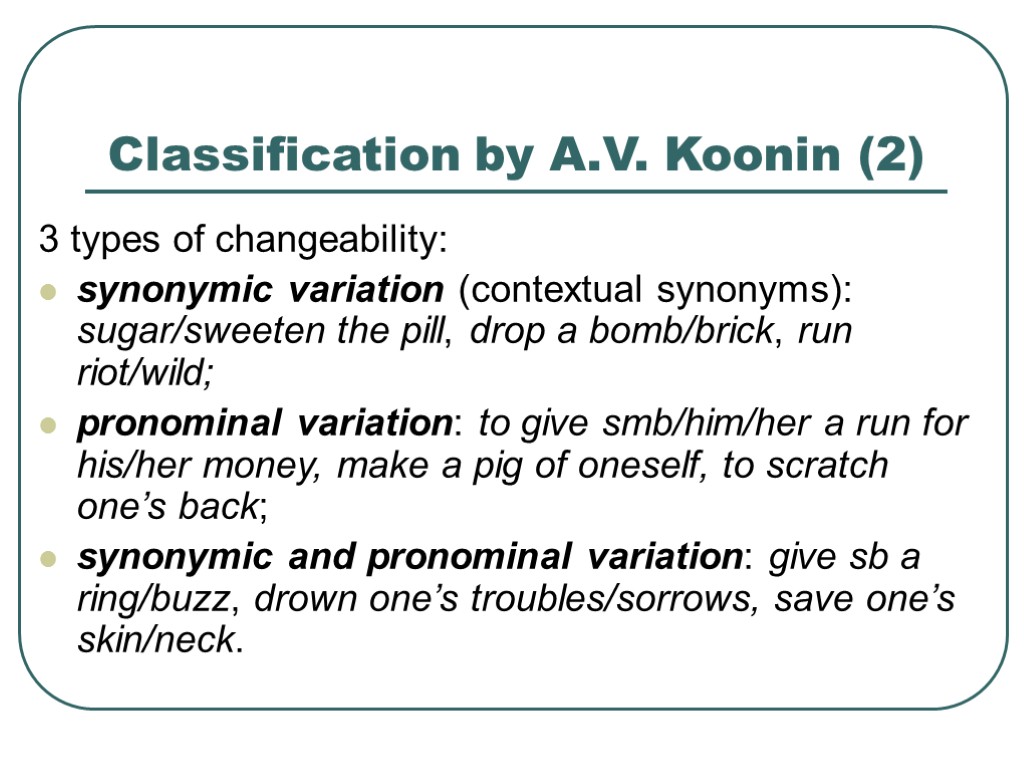

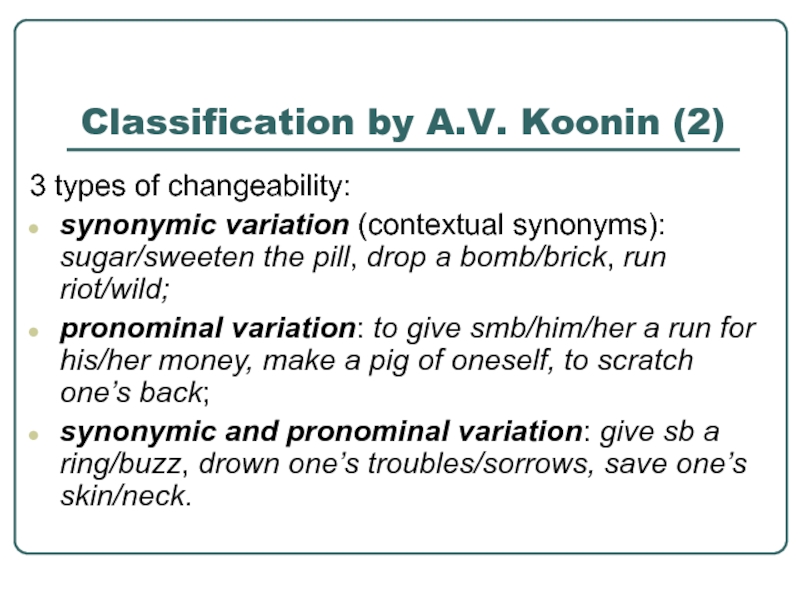

more generally, on the interdependence between the meaning of the elements and the meaning of the set expression. Much attention is devoted to different types of variation: synonymic, pronominal, etc.

After this brief review of possible semantic classifications, we pass on to a formal and functional classification based on the fact that a set expression functioning in speech is in distribution similar to definite classes of words, whereas structurally it can be identified with various types of syntagmas or with complete sentences.

We shall distinguish set expressions that are nominal phrases: the wot of the trouble’, verbal phrases: put one’s best foot forward; adjectival phrases: as good as gold; red as a cherry; adverbial phrases: from head to foot; prepositional phrases: in the course of; conjunctional phrases: as long as, on the other hand; interjectional phrases: Well, I never!Astereotyped sentence also introduced into speech as a ready-made formula may be illustrated by Never say die! ‘never give up hope’, take your time ‘do not hurry’.

The above classification takes into consideration not only the type of component parts but also the functioning of the whole, thus, tooth and nail is not a nominal but an adverbial unit, because it serves to modify a verb (e. g. fight tooth and nail); the identically structured lord and master is a nominal phrase. Moreover, not every nominal phrase is used in all syntactic functions possible for nouns. Thus, a bed of roses or a bed of nails and forlorn hope are used only predicatively.

Within each of these classes a further subdivision is necessary. The following list is not meant to be exhaustive, but to give only the principal features of the types.

I. Set expressions functioning like nouns:

N+N: maiden name ‘the surname of a woman before she was married’; brains trust ‘a committee of experts’ or ‘a number of reputedly well informed persons chosen to answer questions of general interest without preparation’, family jewels ‘shameful secrets of the CIA’ (Am. slang).

N’s+N: cat’s paw ‘one who is used for the convenience of a cleverer and stronger person’ (the expression comes from a fable in which a monkey wanting to eat some chestnuts that were on a hot stove, but not wishing to burn himself while getting them, seised a cat and holding its paw in his own used it to knock the chestnuts to the ground); Hob-son’s choice, a set expression used when there is no choice at all, when a person has to take what is offered or nothing (Thomas Hobson, a 17th century London stableman, made every person hiring horses take the next in order).

Ns’+N: ladies’ man ‘one who makes special effort to charm or please women’.

N+prp+N: the arm of the law; skeleton in the cupboard.

N+A: knight errant (the phrase is today applied to any chivalrous man ready to help and protect oppressed and helpless people).

N+and+N: lord and master ‘husband’; all the world and his

172

wife (a more complicated form); rank and file ‘the ordinary working members of an organisation’ (the origin of this expression is military life, it denotes common soldiers); ways and means ‘methods of overcoming difficulties’.

A+N: green room ‘the general reception room of a theatre’ (it is said that formerly such rooms had their walls coloured green to relieve the strain on the actors’ eyes after the stage lights); high tea ‘an evening meal which combines meat or some similar extra dish with the usual tea’; forty winks ‘a short nap’.

N+subordinate clause: ships that pass in the night ‘chance acquaintances’.

II. Set expressions functioning like verbs: V+N: take advantage

V+and+V: pick and choose V+(one’s)+N+(prp): snap ones fingers at V+one+N: give one the bird ‘to fire sb’

V+subordinate clause: see how the land lies ‘to discover the state of affairs’.

III. Set expressions functioning like adjectives: A+and+A: high and mighty

(as)+A+as+N: as old as the hills, as mad as ahatter Set expressions are often used as predicatives but not attributively. In the latter function they are replaced by compounds.

IV. Set expressions functioning like adverbs:

A big group containing many different types of units, some of them with a high frequency index, neutral in style and devoid of expressiveness, others expressive.

N+N: tooth and nail

prp+N: by heart, of course, against the grain

adv+prp+N: once in a blue moon

prp+N+or+N: by hook or by crook

cj+clause: before one can say Jack Robinson

V. Set expressions functioning like prepositions: prp+N+prp: in consequence of

It should be noted that the type is often but not always characterised by the absence of article. Сf: by reason of : : on the ground of.

VI. Set expressions functioning like interjections:

These are often structured as imperative sentences: Bless (one’s) soul! God bless me! Hang it (all)!

This review can only be brief and very general but it will not be difficult for the reader to supply the missing links.

The list of types gives a clear notion of the contradictory nature of set expressions: structured like phrases they function like words.

There is one more type of combinations, also rigid and introduced into discourse ready-made but differing from all the types given above in so far as it is impossible to find its equivalent among the parts of speech. These are formulas used as complete utterances and syntactically shaped like sentences, such as the well-known American maxim Keep smiling! or the British Keep Britain tidy. Take it easy.

173

A.I. Smirnitsky was the first among Soviet scholars who paid attention to sentences that can be treated as complete formulas, such as How do you do? or I beg your pardon, It takes all kinds to make the world, Can the leopard change his spots? They differ from all the combinations so far discussed, because they are not equivalent to words in distribution and are semantically analysable. The formulas discussed by N.N. Amosova are on the contrary semantically specific, e. g. save your breath ‘shut up’ or tell it to the marines. As it often happens with set expressions, there are different explanations for their origin. (One of the suggested origins is tell that to the horse marines; such a corps being nonexistent, as marines are a sea-going force, the last expression means ‘tell it to someone who does not exist, because real people will not believe it’). Very often such formulas, formally identical to sentences are in reality used only as insertions into other sentences: the cap fits ‘the statement is true’ (e. g.: “He called me a liar.” “Well, you should know if the cap fits. ) Compare also: Butter would not melt in his mouth; His bark is worse than his bite.

§ 9.4 SIMILARITY AND DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A SET EXPRESSION AND A WORD

There is a pressing need for criteria distinguishing set expressions not only from free phrases but from compound words as well. One of these criteria is the formal integrity of words which had been repeatedly mentioned and may be best illustrated by an example with the word breakfast borrowed from W.L. Graff. His approach combines contextual analysis and diachronic observations. He is interested in gradation from free construction through the formula to compound and then simple word. In showing the borderline between a word and a formular expression, W.L. Graff speaks about the word breakfast derived from the set expression to break fast, where break was a verb with a specific meaning inherent to it only in combination with fast which means ‘keeping from food’. Hence it was possible to say: And knight and squire had broke their fast (W.Scott). The fact that it was a phrase and not a word is clearly indicated by the conjugation treatment of the verb and syntactical treatment of the noun. With an analytical language like English this conjugation test is, unfortunately, not always applicable.

It would also be misleading to be guided in distinguishing between set expressions and compound words by semantic considerations, there being no rigorous criteria for differentiating between one complex notion and a combination of two or more notions. The references of component words are lost within the whole of a set expression, no less than within a compound word. What is, for instance, the difference in this respect between the set expression point of view and the compound viewpoint? And if there is any, what are the formal criteria which can help to estimate it?

174

Alongside with semantic unity many authors mention the unity of syntactic function. This unity of syntactic function is obvious in the predicate of the main clause in the following quotation from J. Wain, which is a simple predicate, though rendered by a set expression: …the government we had in those days, when we (Great Britain) were the world’s richest country, didn’t give a damn whether the kids grew up with rickets or not …

This syntactic unity, however, is not specific for all set expressions.

Two types of substitution tests can be useful in showing us the points of similarity and difference between the words and set expressions. In the first procedure a whole set expression is replaced within context by a synonymous word in such a way that the meaning of the utterance remains unchanged, e. g. he was in a brown study → he mas gloomy. In the second type of substitution test only an element of the set expression is replaced, e. g. (as) white as chalk → (as) white as milk → (as) white as snow; or it gives me the blues → it gives him the blues → it gives one the blues. In this second type it is the set expression that is retained, although its composition or referential meaning may change.

When applying the first type of procedure one obtains a criterion for the degree of equivalence between a set expression and a word. One more example will help to make the point clear. The set expression dead beat can be substituted by a single word exhausted. E. g.: Dispatches, sir. Delivered by a corporal of the 33rd. Dead beat with hard riding, sir (Shaw). The last sentence may be changed into Exhausted with hard riding, sir. The lines will keep their meaning and remain grammatically correct. The possibility of this substitution permits us to regard this set expression as a word equivalent.

On the other hand, there are cases when substitution is not possible. The set expression red tape has a one word equivalent in Russian бюрократизм, but in English it can be substituted only by a free phrase. Thus, in the enumeration of political evils in the example below red tape, although syntactically equivalent to derivative nouns used as homogeneous members, can be substituted only by some free phrase, such as rigid formality of official routine. Cf. the following example:

BURGOYNE: And will you wipe out our enemies in London, too? SWINDON: In London! What enemies?

BURGOYNE (forcible): Jobbery and snobbery, incompetence and Red Tape … (Shaw).

The unity of syntactic function is present in this case also, but the criterion of equivalence to a single word cannot be applied, because substitution by a single word is impossible. Such equivalence is therefore only relative, it is not universally applicable and cannot be accepted as a general criterion for defining these units. The equivalence of words and set expressions should not be taken too literally but treated as a useful abstraction, only in the sense we have stated.

The main point of difference between a word and a set expression is the divisibility of the latter into separately structured elements which is contrasted to the structural integrity of words. Although equivalent to words in being introduced into speech ready-made, a set expression is different from them, because it can be resolved into words, whereas words are resolved 175

into morphemes. In compound words the process of integration is more advanced. The methods and criteria serving to identify compounds and distinguish them from phrases or groups of words, no matter how often used together, have been pointed out in the chapter on compounds.

Morphological divisibility is evident when one of the elements (but not the last one as in a compound word) is subjected to morphological change. This problem has been investigated by N.N. Amosova, A.V. Koonin and others.] N.N. Amosova gives the following examples:

He played second fiddle to her in his father’s heart (Galsworthy). … She disliked playing second fiddle (Christie). To play second fiddle ‘to occupy a secondary, subordinate position’.

It must be rather fun having a skeleton in the cupboard (Milne). I hate skeletons in the cupboard (Ibid.) A skeleton in the cupboard ‘a family secret’.

A.V. Koonin shows the possibility of morphological changes in adjectives forming part of phraseological units: He’s deader than a doornail; It made the night blacker than pitch; The Cantervilles have blue blood, for instance, the bluest in England.

It goes without saying that the possibility of a morphological change cannot regularly serve as a distinctive feature, because it may take place only in a limited number of set expressions (verbal or nominal).

The question of syntactic ties within a set expression is even more controversial. All the authors agree that set expressions (for the most part) represent one member of the sentence, but opinions differ as to whether this means that there are no syntactical ties within set expressions themselves. Actually the number of words in a sentence is not necessarily equal to the number of its members.

The existence of syntactical relations within a set expression can be proved by the possibility of syntactical transformations (however limited) or inversion of elements and the substitution of the variable member, all this without destroying the set expression as such. By a variable element we mean the element of the set expression which is structurally necessary but free to vary lexically. It is usually indicated in dictionaries by indefinite pronouns, often inserted in round brackets: make (somebody’s) hair stand on end ‘to give the greatest astonishment or fright to another person’; sow (one’s) wild oats ‘to indulge in dissipation while young’. The word in brackets can be freely substituted: make (my, your, her, the reader’s) hair stand on end.

The sequence of constant elements may be broken and some additional words inserted, which, splitting the set expression, do not destroy it, but establish syntactical ties with its regular elements. The examples are chiefly limited to verbal expressions, e.g. The chairman broke the ice → Ice was broken by the chairman; Has burnt his boats and … → Having burnt his boats he … Pronominal substitution is illustrated by the following example: “Hold your tongue, Lady L.” “Hold yours, my good fool.” (N. Marsh, quoted by N.N. Amosova)

All these facts are convincing manifestations of syntactical ties within

176

the units in question. Containing the same elements these units can change their morphological form and syntactical structure, they may be called changeable set expressions, as contrasted to stereotyped or unchangeable set expressions, admitting no change either morphological or syntactical. The examples discussed in the previous paragraph mostly belong to this second type, indivisible and unchangeable; they are nearer to a word than their more flexible counterparts. This opposition is definitely correlated with structural properties.

All these examples proving the divisibility and variability of set expressions throw light on the difference between them and words.

Слайд 1MODERN

ENGLISH LEXICOLOGY

Phraseology.

Set-expressions.

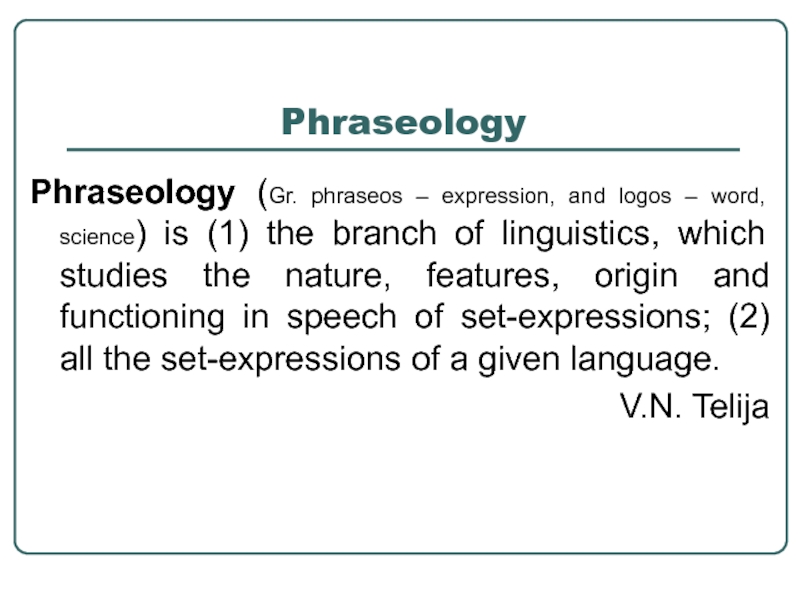

Слайд 2Phraseology

Phraseology (Gr. phraseos – expression, and logos – word, science)

is (1) the branch of linguistics, which studies the nature, features, origin and functioning in speech of set-expressions; (2) all the set-expressions of a given language.

V.N. Telija

Слайд 3Phraseology

Фразеология – это наука о фразеологических единицах, т.е. об устойчивых

сочетаниях слов с осложненной семантикой, не образующихся по порождающим структурно-семантическим моделям переменных сочетаний.

А.В. Кунин

Слайд 4The development of Phraseology

Ch. Bally

U. Weinreich

A. Makkai

F.F. Fortunatov

A.A. Schachmatov

V.

V. Vinogradov

A.V. Kunin

A.I. Smirnitsky

N.N. Amosova

V.N. Telija

Слайд 5Set-expression

Set-expression is a word-group consisting of two or more words whose

combination is integrated as a unit with a specialized meaning of the whole.

Set-expressions are characterized by stability, i.e. their fixed and ready-made nature, and polylexicality, i.e. consisting of more than one lexical unit.

Слайд 6Terminological problem

Set-expressions are also called:

set phrase (V.V. Vinogradov, semantic approach);

idiom (N.N.

Amosova, contextual approach);

word-equivalent (A.I. Smirnitsky, functional approach);

phraseological unit (A.V. Kunin).

The differences in terminology reflect the differences in the main criteria used to distinguish between free word-groups and set-expressions.

Слайд 7The problem of differentiation of a free-phrase, semi-fixed phrases and set-expressions

There

are two major criteria for distinguishing between free phrases and set expressions: semantic and structural.

The semantic criterion realizes in possibility or impossibility to deduce the meaning of the whole word-group from the meanings of the constituents.

The structural criterion shows in possibility or impossibility of substitution in a word-group.

Слайд 8Free phrases, e.g. to play with a dog, are formed in

the flow of speech, contain elements in their individual direct meanings, have independent syntactic functions.

Слайд 9Semi-fixed combinations, e.g. to play with fire (“to do smth dangerously”)

are stable ready-made groups the elements of which have separate direct meaning but the whole has the transferred meaning and integral functions. In these combinations we are able to fix and even to list the substitutes existing: e.g. to go to school/market/courts, i.e. it is used only with nouns of place where definite actions are performed.

Слайд 10Set expressions: e.g. The French President refuses to play ball. (coll.

“to cooperate with the leader of the other country”).

These are ready-made stable word groups, elements make a fixed context for each other to form the whole, with one syntactic function and meaning that is not deduced from the components.

No substitution is possible apart from pronominal and synonymic ones:

She/he knows on which side her/his bread is buttered (pronominal substitution)

To stir/move a finger (synonymic substitution).

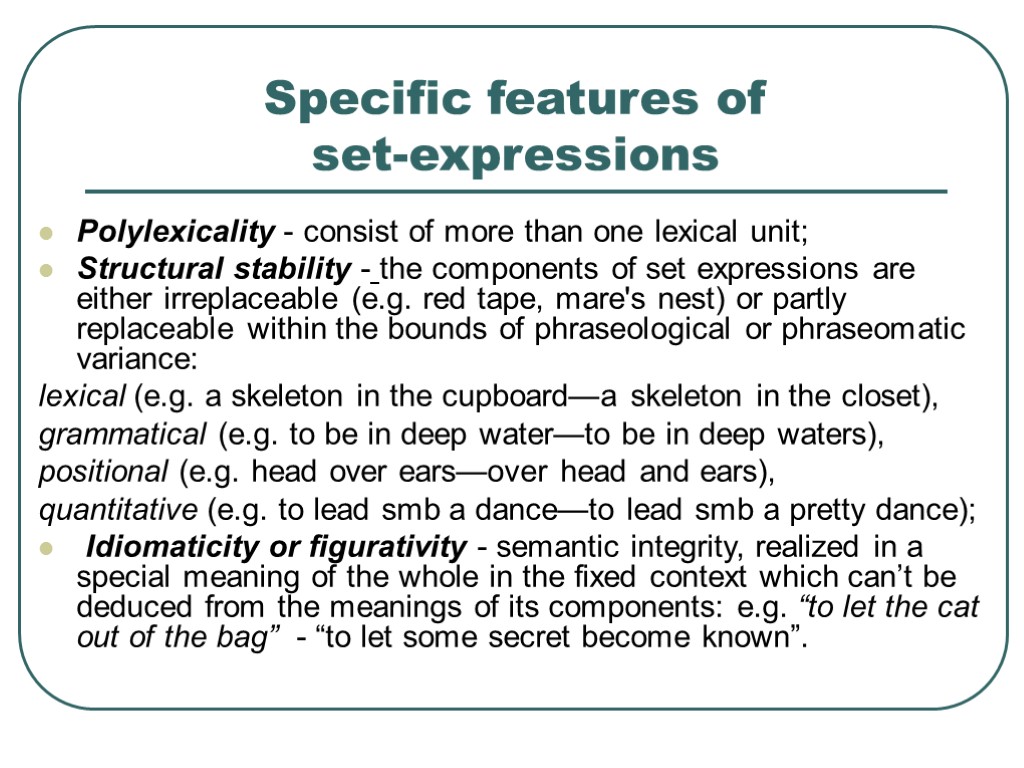

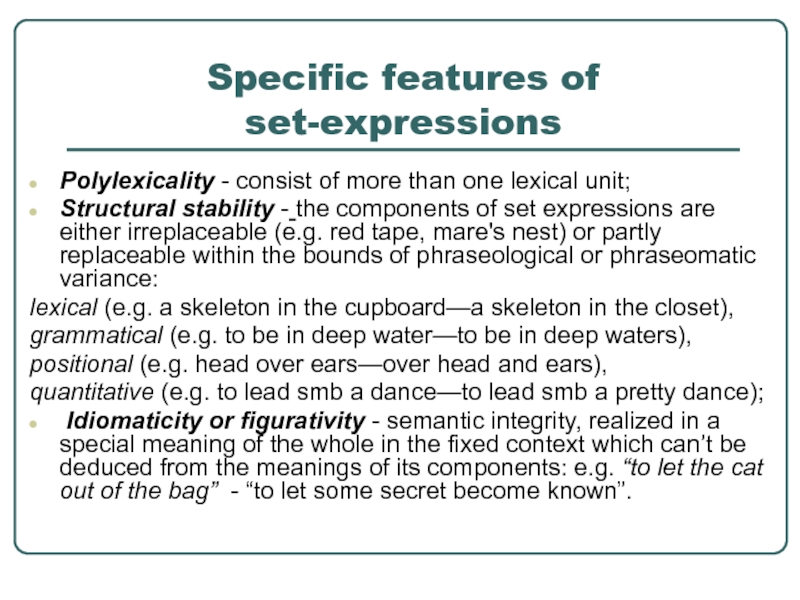

Слайд 11Specific features of

set-expressions

Polylexicality — consist of more than one lexical

unit;

Structural stability — the components of set expressions are either irreplaceable (e.g. red tape, mare’s nest) or partly replaceable within the bounds of phraseological or phraseomatic variance:

lexical (e.g. a skeleton in the cupboard—a skeleton in the closet),

grammatical (e.g. to be in deep water—to be in deep waters),

positional (e.g. head over ears—over head and ears),

quantitative (e.g. to lead smb a dance—to lead smb a pretty dance);

Idiomaticity or figurativity — semantic integrity, realized in a special meaning of the whole in the fixed context which can’t be deduced from the meanings of its components: e.g. “to let the cat out of the bag” — “to let some secret become known”.

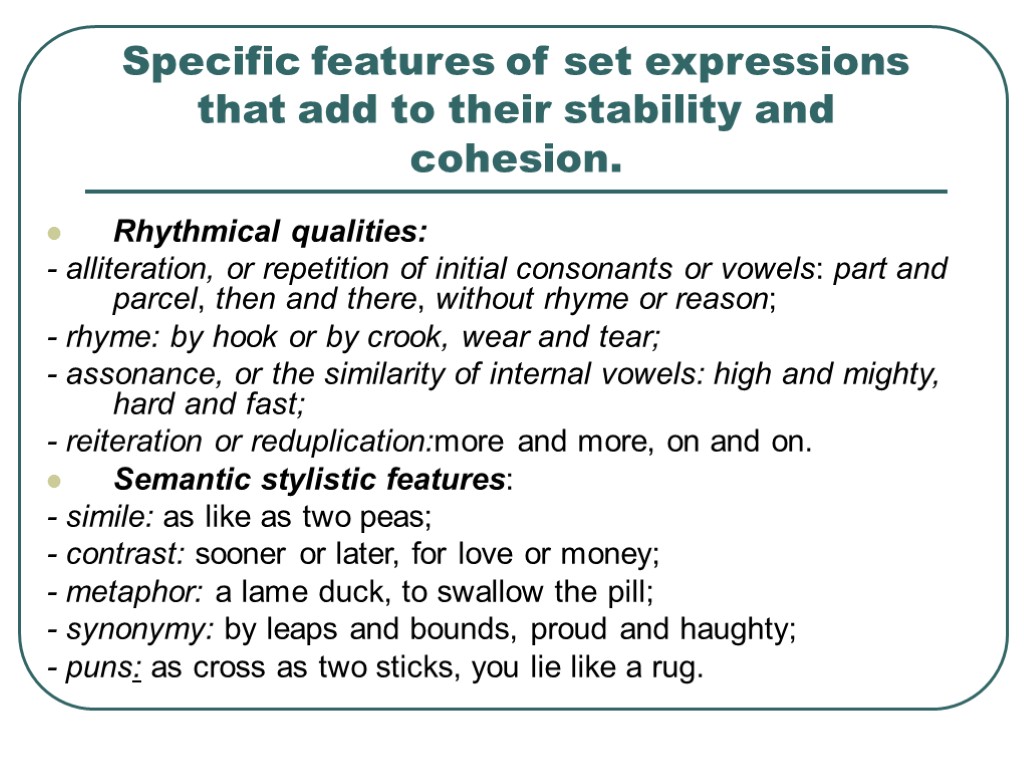

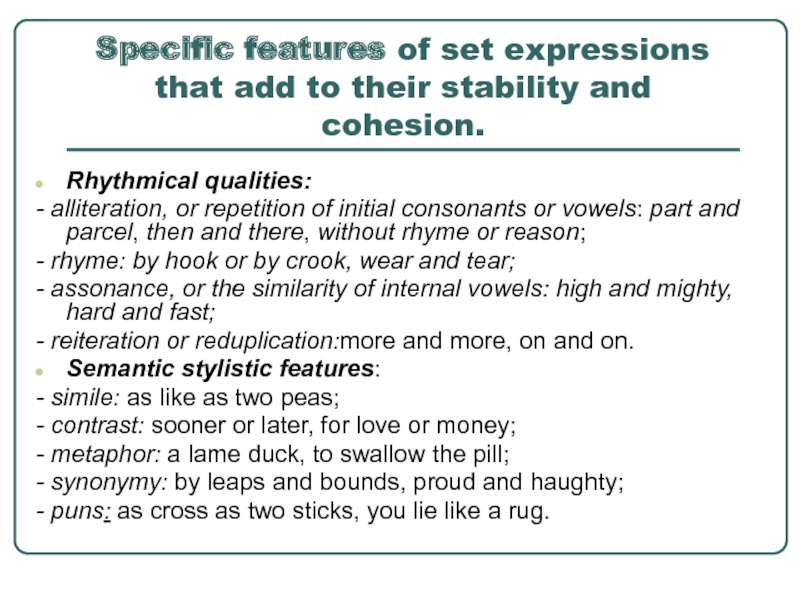

Слайд 12Specific features of set expressions that add to their stability and

cohesion.

Rhythmical qualities:

— alliteration, or repetition of initial consonants or vowels: part and parcel, then and there, without rhyme or reason;

— rhyme: by hook or by crook, wear and tear;

— assonance, or the similarity of internal vowels: high and mighty, hard and fast;

— reiteration or reduplication:more and more, on and on.

Semantic stylistic features:

— simile: as like as two peas;

— contrast: sooner or later, for love or money;

— metaphor: a lame duck, to swallow the pill;

— synonymy: by leaps and bounds, proud and haughty;

— puns: as cross as two sticks, you lie like a rug.

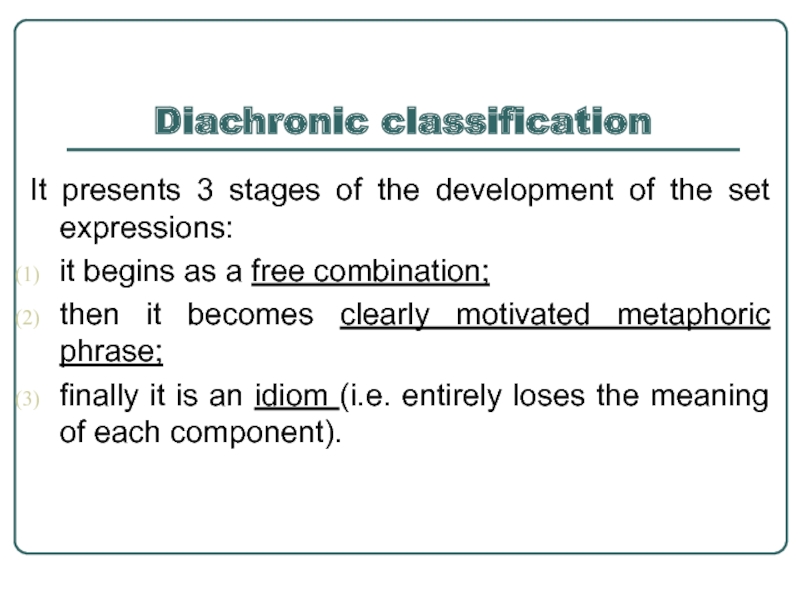

Слайд 14Diachronic classification

It presents 3 stages of the development of the

set expressions:

it begins as a free combination;

then it becomes clearly motivated metaphoric phrase;

finally it is an idiom (i.e. entirely loses the meaning of each component).

Слайд 15”Thematic” classification by L.P. Smith and W. Ball

They suggest groups

of set expressions used by sailors, fishermen, soldiers, hunters and associated with their occupations; groups of set expressions associated with domestic and wild animals and birds, agriculture and cooking, sports, arts

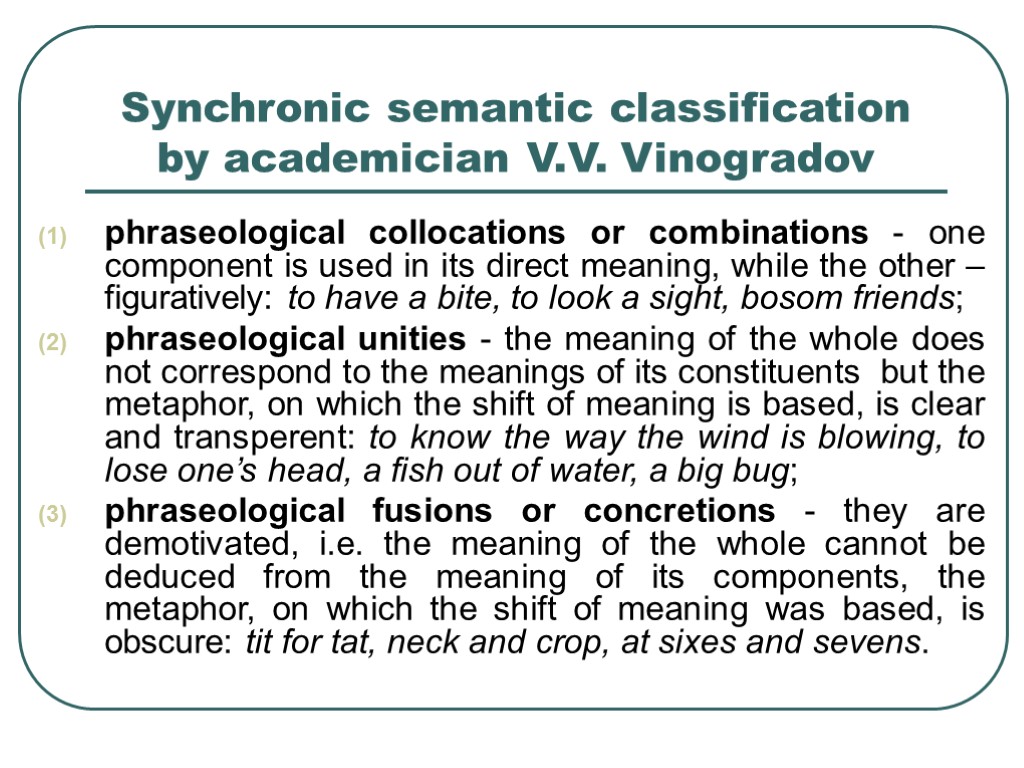

Слайд 16Synchronic semantic classification by academician V.V. Vinogradov

phraseological collocations or combinations

— one component is used in its direct meaning, while the other – figuratively: to have a bite, to look a sight, bosom friends;

phraseological unities — the meaning of the whole does not correspond to the meanings of its constituents but the metaphor, on which the shift of meaning is based, is clear and transperent: to know the way the wind is blowing, to lose one’s head, a fish out of water, a big bug;

phraseological fusions or concretions — they are demotivated, i.e. the meaning of the whole cannot be deduced from the meaning of its components, the metaphor, on which the shift of meaning was based, is obscure: tit for tat, neck and crop, at sixes and sevens.

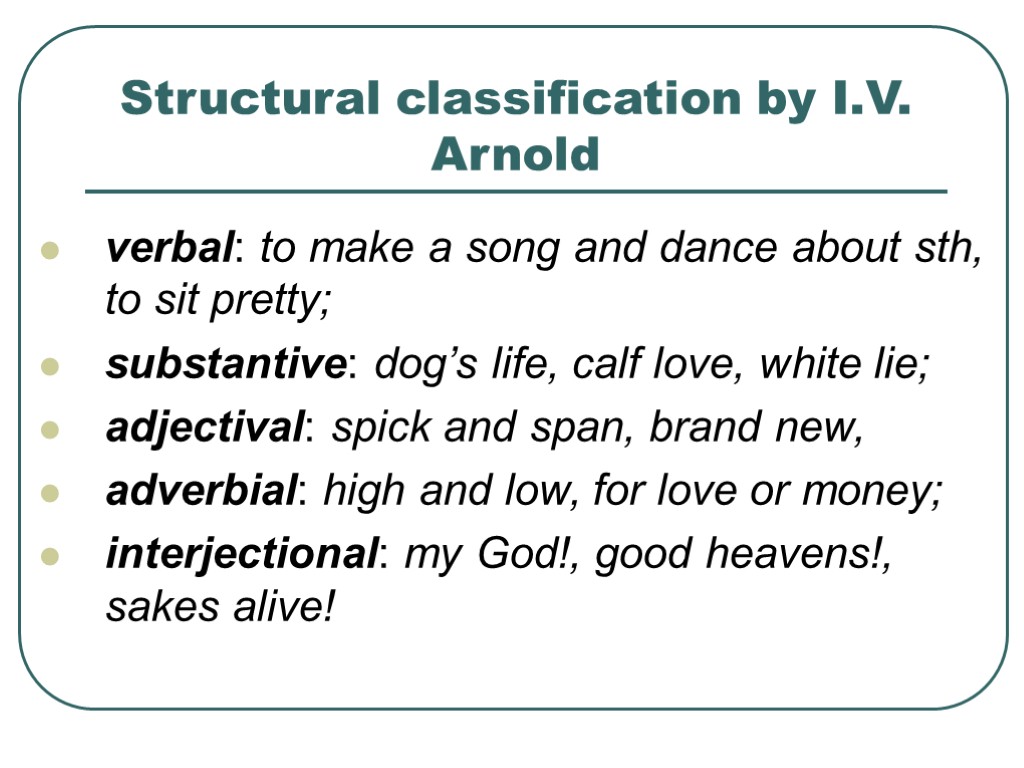

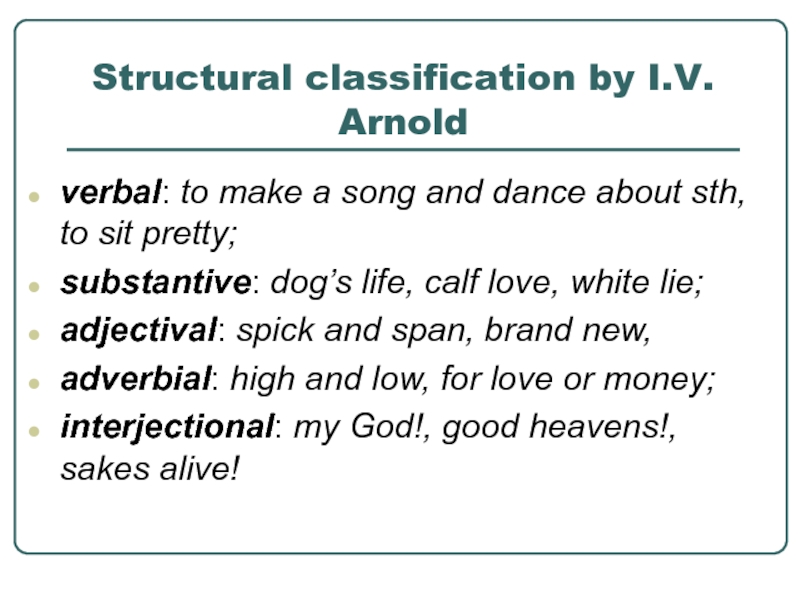

Слайд 17Structural classification by I.V. Arnold

verbal: to make a song and dance

about sth, to sit pretty;

substantive: dog’s life, calf love, white lie;

adjectival: spick and span, brand new,

adverbial: high and low, for love or money;

interjectional: my God!, good heavens!, sakes alive!

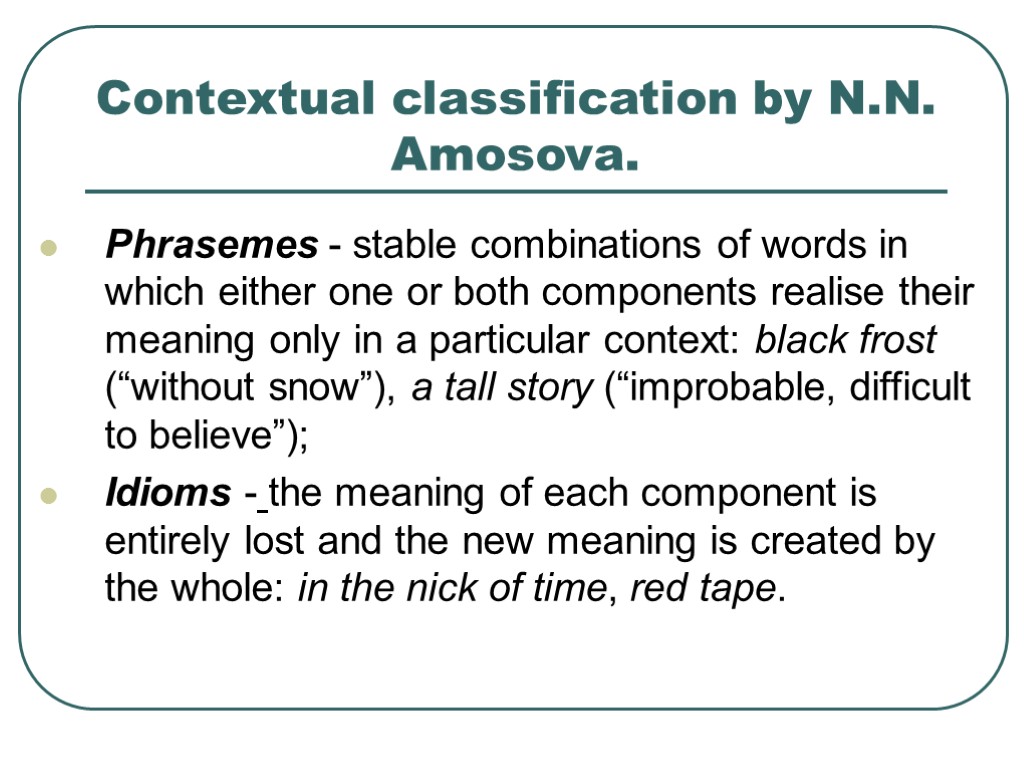

Слайд 18Contextual classification by N.N. Amosova.

Phrasemes — stable combinations of words

in which either one or both components realise their meaning only in a particular context: black frost (“without snow”), a tall story (“improbable, difficult to believe”);

Idioms — the meaning of each component is entirely lost and the new meaning is created by the whole: in the nick of time, red tape.

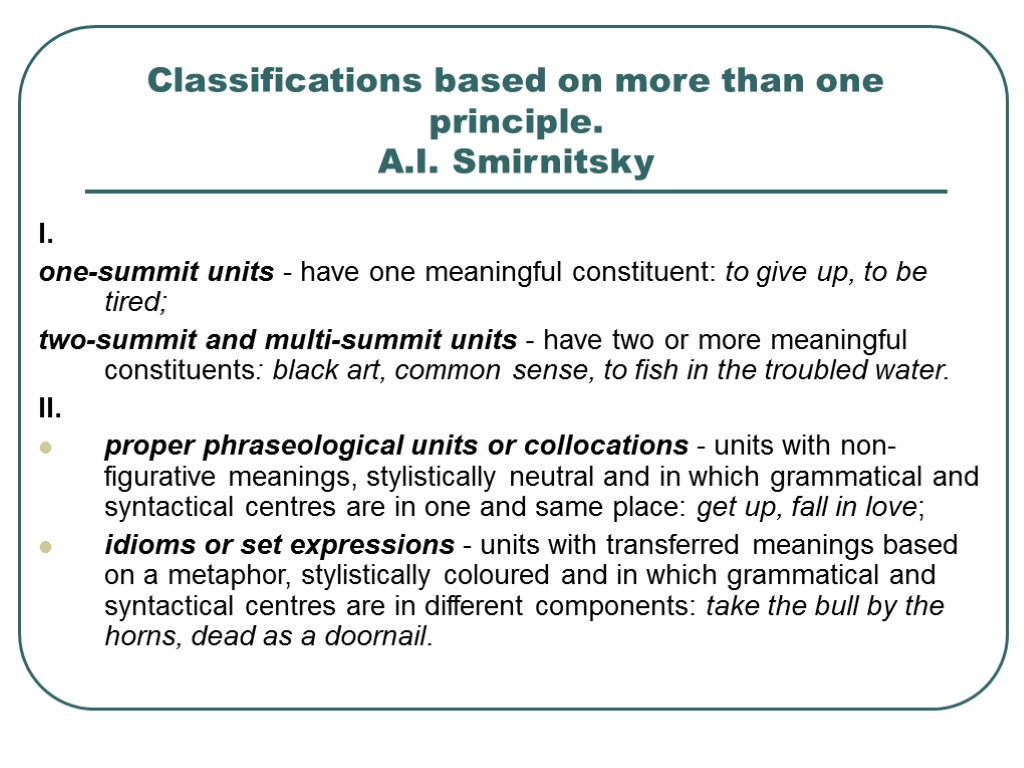

Слайд 19Classifications based on more than one principle.

A.I. Smirnitsky

I.

one-summit units — have

one meaningful constituent: to give up, to be tired;

two-summit and multi-summit units — have two or more meaningful constituents: black art, common sense, to fish in the troubled water.

II.

proper phraseological units or collocations — units with non-figurative meanings, stylistically neutral and in which grammatical and syntactical centres are in one and same place: get up, fall in love;

idioms or set expressions — units with transferred meanings based on a metaphor, stylistically coloured and in which grammatical and syntactical centres are in different components: take the bull by the horns, dead as a doornail.

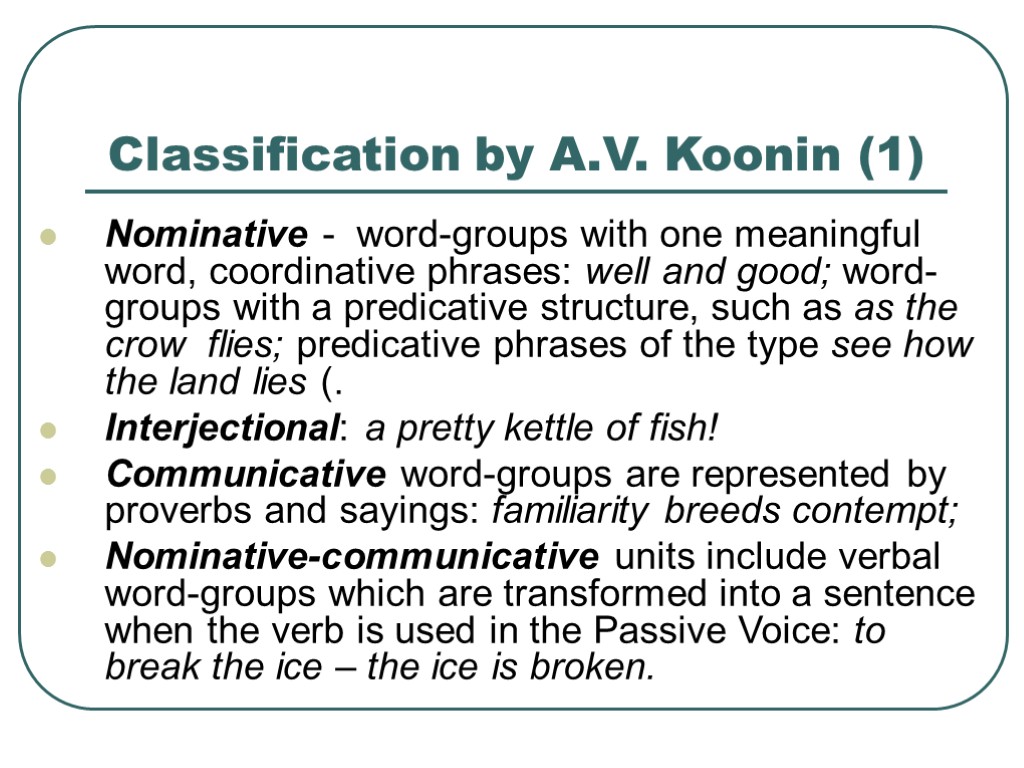

Слайд 20Classification by A.V. Koonin (1)

Nominative — word-groups with one meaningful

word, coordinative phrases: well and good; word-groups with a predicative structure, such as as the crow flies; predicative phrases of the type see how the land lies (.

Interjectional: a pretty kettle of fish!

Communicative word-groups are represented by proverbs and sayings: familiarity breeds contempt;

Nominative-communicative units include verbal word-groups which are transformed into a sentence when the verb is used in the Passive Voice: to break the ice – the ice is broken.

Слайд 21Classification by A.V. Koonin (2)

3 types of changeability:

synonymic variation (contextual synonyms):

sugar/sweeten the pill, drop a bomb/brick, run riot/wild;

pronominal variation: to give smb/him/her a run for his/her money, make a pig of oneself, to scratch one’s back;

synonymic and pronominal variation: give sb a ring/buzz, drown one’s troubles/sorrows, save one’s skin/neck.

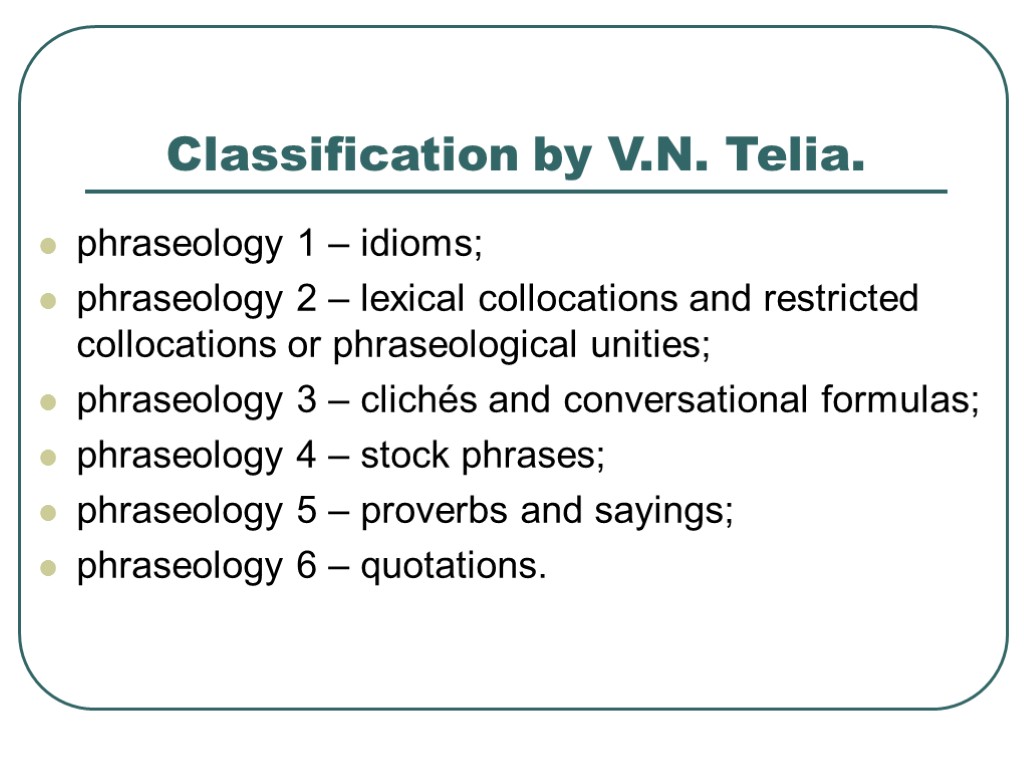

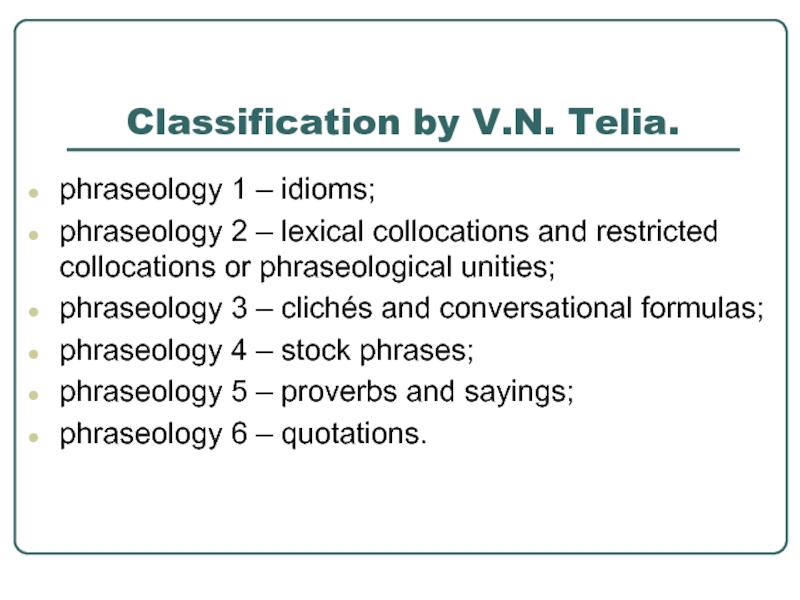

Слайд 22Classification by V.N. Telia.

phraseology 1 – idioms;

phraseology 2 – lexical collocations

and restricted collocations or phraseological unities;

phraseology 3 – clichés and conversational formulas;

phraseology 4 – stock phrases;

phraseology 5 – proverbs and sayings;

phraseology 6 – quotations.

Скачать материал

Скачать материал

- Сейчас обучается 268 человек из 64 регионов

- Сейчас обучается 396 человек из 63 регионов

Описание презентации по отдельным слайдам:

-

1 слайд

Main types of set expressions in Modern English

-

2 слайд

Set expressions

The word «phraseology“ has very different meanings in this country and in Great Britain or the United States. In Soviet linguistic literature the term has come to be used for the whole ensemble of expressions where the meaning of one element is dependent on the other, irrespective of the structure and properties of the unit (V.V. Vinogradov); with other authors it denotes only such set expressions which, as distinguished from idioms, do not possess expressiveness or emotional colouring (A.I. Smirnitsky), and also vice versa: only those that are imaginative, expressive and emotional.N.N. Amosova overcomes the subjectiveness of the two last mentioned approaches when she insists on the term being applicable only to what she calls fixed context units, i.e. units in which it is impossible to substitute any of the components without changing the meaning not only of the whole unit but also of the elements that remain intact. O.S. Ahmanova has repeatedly insisted on the semantic integrity of such phrases prevailing over the structural separateness of their elements. A.V. Koonin lays stress on the structural separateness of the elements in a phraseological unit, on the change of meaning in the whole as compared with its elements taken separately and on a certain minimum stability.

-

3 слайд

Set expressions

*All these authors use the same word «phraseology» to denote the branch of linguistics studying the word groups they have in mind.

In English and American linguistics the situation is very different. No special branch of study exists, and the term «phraseology» is a stylistic one meaning, according to Webster’s dictionary, ‘mode of expression, peculiarities of diction, i.e. choice and arrangement of words and phrases characteristic of some author or some literary work.

*The word «idiom» is even more polysemantic. The English use it to denote a mode of expression peculiar to a language, without differentiating between the grammatical and lexical levels. It may also mean a group of words whose meaning it is difficult or impossible to understand from the knowledge of the words considered separately. Moreover, «idiom» may be synonymous to the words «language» or «dialect», denoting a form of expression peculiar to a people, a country, a district, or to one individual. There seems to be no point in enumerating further possibilities. The word «phrase» is no less polysemantic.

*The term set expression is on the contrary more definite and self-explanatory, because the first element points out the most important characteristic of these units, namely, their stability, their fixed and ready-made nature. The word «expression» suits our purpose, because it is a general term including words, groups of words and sentences, so that both ups and downs and that’s a horse of another colour are expressions. -

4 слайд

Set expressions

Set expressions have sometimes been called «word equivalents», and it has been postulated by A.I. Smirnitsky that the vocabulary of a language consists of words and word equivalents (word-groups), similar to words in so far as they are not created in speech but introduced into the act of communication ready-made. It is most important to keep in mind that here equivalence means only this and nothing more.

Set expressions are contrasted to free phrases and semi fixed combinations. All these are but different stages of restrictions imposed upon co occurrence of words, upon the lexical filling of structural patterns which are specific for even’ language. The restrictions may be independent of the ties existing in extralinguistic reality between the objects spoken of and be conditioned by purely linguistic factors, or have extralinguistic causes in the history of the people. In free combinations the linguistic factors are

chiefly connected with grammatical properties of words. -

5 слайд

Set expressions

If substitution is only pronominal, or restricted to a few synonyms for one of the members only, or impossible, i.e. if the elements of the phrase are always the same and make a fixed context for each other, the word-group is a set expression.

According to the type of motivation and the other above-mentioned features, three types of phraseological units are suggested: phraseological fusions, phraseological unities and phraseological combinations.

Phraseological fusions (e. g. tit for tat)

represent as their name suggests the highest stage of blending together. The meaning of components is completely absorbed by the meaning of the whole, by its expressiveness and emotional properties. Phraseological fusions are specific for every language and do not lend themselves to literal translation into other languages.

Phraseological unities

are much more numerous. They are clearly motivated. The emotional quality is based upon the image created by the whole as in to stick (to stand) to one’s guns, i.e. ‘refuse to change one’s statements or opinions in the face of opposition’, implying courage and integrity. The example reveals another characteristic of the type, namely the possibility of synonymic substitution, which can be only very limited. Some of these are easily translated and even international, e. g. to know the way the wind is blowing.

The third group in this classification, the phraseological combinations, are not only motivated but contain one component used in its direct meaning while the other is used figuratively: meet the demand, meet the necessity, meet the requirements. The mobility of this type is much greater, the substitutions are not necessarily synonymical. -

6 слайд

Set expressions

It has been pointed out by N.N. Amosova and A.V. Koonin that this classification, being developed for the Russian phraseology, does not fit the specifically English features.

N.N. Amosova’s approach is contextological. She defines phraseological units as units of fixed context. Fixed context is defined as a context characterized by a specific and unchanging sequence of definite lexical components, and a peculiar semantic relationship between them. Units of fixed context are subdivided into phrasemes and idioms. Phrasemes are always binary: one component has a phraseologically bound meaning, the other serves as the determining context (small talk, small hours, small change). In idioms the new meaning is created by the whole, though every element it has its original meaning weakened or even completely lost: in the nick of time ‘at the exact moment’. Idioms may be motivated or demotivated. A motivated idiom is homonymous to a free phrase, but this phrase is used figuratively: take the bull by the horns

‘to face dangers without fear’. In the nick of time is

demotivated, because the word nick is obsolete.

Both phrasemes and idioms may be movable

(changeable) or immovable. -

7 слайд

Set expressions

An interesting and clear-cut modification of V.V. Vinogradov’s scheme was suggested by T.V. Stroyeva for the German language. She divides the whole bulk of phraseological units into two classes: u n i t-i e s and combinations. Phraseological fusions do not constitute a separate class but are included into unities, because the criterion of motivation and demotivation is different for different speakers, depending on their education and erudition. The figurative meaning of a phraseological unity is created by the whole, the semantic transfer being dependent on extra-linguistic factors, i.e. the history of the people and its culture. There may occur in speech homonymous free phrases, very different in meaning (c /. jemandem den Kopf waschen ‘to scold sb’ — a phraseological unity and den Kopf waschen ‘to wash one’s head’ — a free phrase). The form and structure of a phraseological unity is rigid and unchangeable. Its stability is often supported by rhyme, synonymy, parallel construction, etc. Phraseological combinations, on the contrary, reveal a change of meaning only in one of the components and this semantic shift does not result in enhancing expressiveness. -

8 слайд

Set expressions

A.V. Koonin is interested both in discussing fundamentals and in investigating special problems. His books, and especially the dictionary he compiled and also the dissertations of his numerous pupils are particularly useful as they provide an up-to-date survey of the entire field.

A.V. Koonin thinks that phraseology must develop as an independent linguistic science and not as a part of lexicology. His classification of phraseological units is based on the functions the units fulfill in speech. They may be nominating (a bull in a china shop), interjectional (a pretty kettle of fish), communicative (familiarity breeds contempt), or nominating-communicative (pull somebody’s leg). Further classification into subclasses depends on whether the units are changeable more generally, on the interdependence between the meaning of the elements and the meaning of the set expression. Much attention is devoted to different types of variation: synonymic, pronominal, etc.

After this brief review of possible semantic classifications, we pass on to a formal and functional classification based on the fact that a set expression functioning in speech is in distribution similar to definite classes of words, whereas structurally it can be identified with various types of syntagmas or with complete sentences. -

9 слайд

Set expressions

We shall distinguish set expressions that are nominal phrases: the wot of the trouble’, verbal phrases: put one’s best foot forward; adjectival phrases: as good as gold; red as a cherry; adverbial phrases: from head to foot; prepositional phrases: in the course of; conjunctional phrases: as long as, on the other hand; interjectional phrases: Well, I never! A stereotyped sentence also introduced into speech as a ready-made formula may be illustrated by Never say die! ‘never give up hope’, take your time ‘do not hurry’.

The above classification takes into consideration not only the type of component parts but also the functioning of the whole, thus, tooth and nail is not a nominal but an adverbial unit, because it serves to modify a verb (e. g. fight tooth and nail); the identically structured lord and master is a nominal phrase. Moreover, not every nominal phrase is used in all syntactic functions possible for nouns. Thus, a bed of roses or a bed of nails and forlorn hope are used only predicatively.

Within each of these classes a further subdivision is necessary. The following list is not meant to be exhaustive, but to give only the principal features of the types. -

10 слайд

Set expressions

The number of works of our linguists devoted to phraseology is so great that it is impossible to enumerate them; suffice it to say that there exists a comprehensive dictionary of English phraseology compiled by A.V. Koonin. This dictionary sustained several editions and contains an extensive bibliography and articles on some most important problems. The first doctoral thesis on this subject was by N.N. Amosova (1963), then came the doctoral thesis by A.V. Koonin. The results were published in monographs. Prof. A.I. Smirnitsky also devoted attention to this aspect in his book on lexicology. He considers a phraseological unit to be similar to the word because of the idiomatic relationships between its parts resulting in semantic unity and permitting its introduction into speech as something complete.

The influence his classification exercised is much smaller than that of V.V. Vinogradov’s. The classification of V.V. Vinogradov is synchronic. He developed some points first advanced by the Swiss linguist Charles Bally and gave a strong impetus to a purely lexicological treatment of the material. Thanks to him phraseological units were rigorously defined as lexical complexes with specific semantic features and classified accordingly. His classification is based upon the motivation of the unit, i.e. the relationship existing between the meaning of the whole and the meaning of its component parts. The degree of motivation is correlated with the rigidity, indivisibility and semantic unity of the expression, i.e with the possibility of changing the form or the order of components, and of substituting the whole by a single word. The classification is naturally developed for Russian phraseology but we shall illustrate it with English examples. -

11 слайд

Set expressions

N+N , N’s+N , Ns’+N, N+prp+N ,N+A , N+and+N

A+N , N+subordinate clause

Set expressions functioning like nouns

V+N, V+and+V, V+(one’s)+N+(prp), V+one+N, V+subordinate clause

Set expressions functioning like verbs

A+and+A , (as)+A+as+NSet expressions functioning like adjectives

N+N , prp+N, adv+prp+N, prp+N+or+N, cj+clause

Set expressions functioning like adverbs

prp+N+prp

Set expressions functioning like prepositions

Set expressions functioning like interjections

Types of set expressions -

12 слайд

Set expressions

I. Set expressions functioning like nouns:

N+N: maiden name ‘the surname of a woman before she was married’; brains trust ‘a committee of experts’ or ‘a number of reputedly well informed persons chosen to answer questions of general interest without preparation’, family jewels ‘shameful secrets of the CIA’ (Am. slang).

N’s+N: cat’s paw ‘one who is used for the convenience of a cleverer and stronger person’ (the expression comes from a fable in which a monkey wanting to eat some chestnuts that were on a hot stove, but not wishing to burn himself while getting them, seised a cat and holding its paw in his own used it to knock the chestnuts to the ground); Hob-son’s choice, a set expression used when there is no choice at all, when a person has to take what is offered or nothing (Thomas Hobson, a 17th century London stableman, made every person hiring horses take the next in order). -

13 слайд

Set expressions

Ns’+N: ladies’ man ‘one who makes special effort to charm or please women’.

N+prp+N: the arm of the law; skeleton in the cupboard.

N+A: knight errant (the phrase is today applied to any chivalrous man ready to help and protect oppressed and helpless people).

N+and+N: lord and master ‘husband’; all the world and his wife (a more complicated form); rank and file ‘the ordinary working members of an organisation’ (the origin of this expression is military life, it denotes common soldiers); ways and means ‘methods of overcoming difficulties’.

A+N: green room ‘the general reception room of a theatre’ (it is said that formerly such rooms had their walls coloured green to relieve the strain on the actors’ eyes after the stage lights); high tea ‘an evening meal which combines meat or some similar extra dish with the usual tea’; forty winks ‘a short nap’.

N+subordinate clause: ships that pass in the night ‘chance acquaintances’. -

14 слайд

Set expressions

II.Set expressions functioning like verbs: V+N: take advantage

V+and+V: pick and choose V+(one’s)+N+(prp): snap ones fingers at V+one+N: give one the bird ‘to fire sb’

V+subordinate clause: see how the land lies ‘to discover the state of affairs’.

III.Set expressions functioning like adjectives:

A+and+A: high and mighty

(as)+A+as+N: as old as the hills, as mad as a hatter

Set expressions are often used as predicatives but not attributively. In the latter function they are replaced by compounds.

IV.Set expressions functioning like adverbs:

A big group containing many different types of units, some of them with a high frequency index, neutral in style and devoid of expressiveness, others expressive.

N+N: tooth and nail

prp+N: by heart, of course, against the grain

adv+prp+N: once in a blue moon

prp+N+or+N: by hook or by crook

cj+clause: before one can say Jack Robinson

VI. Set expressions functioning like prepositions:

prp+N+prp: in consequence of

It should be noted that the type is often but not always characterised by the absence of article. Сf: by reason of : : on the ground of. -

15 слайд

Set expressions

VI.Set expressions functioning like interjections:

These are often structured as imperative sentences: Bless (one’s) soul! God bless me! Hang it (all)!

This review can only be brief and very general but it will not be difficult for the reader to supply the missing links.

The list of types gives a clear notion of the contradictory nature of set expressions: structured like phrases they function like words.

There is one more type of combinations, also rigid and introduced into discourse ready-made but differing from all the types given above in so far as it is impossible to find its equivalent among the parts of speech. These are formulas used as complete utterances and syntactically shaped like sentences,

such as the well-known American maxim

Keep smiling! or the British Keep Britain tidy.

Take it easy. -

16 слайд

Set expressions

A.I. Smirnitsky was the first among Soviet scholars who paid attention to sentences that can be treated as complete formulas, such as How do you do? or I beg your pardon, It takes all kinds to make the world, Can the leopard change his spots? They differ from all the combinations so far discussed, because they are not equivalent to words in distribution and are semantically analysable. The formulas discussed by N.N. Amosova are on the contrary semantically specific, e. g. save your breath ‘shut up’ or tell it to the marines. As it often happens with set expressions, there are different explanations for their origin. (One of the suggested origins is tell that to the horse marines; such a corps being nonexistent, as marines are a sea-going force, the last expression means ‘tell it to someone who does not exist, because real people will not believe it’). Very often such formulas, formally identical to sentences are in reality used only as insertions into other sentences: the cap fits ‘the statement is true’ (e. g.: “He called me a liar.” “Well, you should know if the cap fits. ) Compare also: Butter would not melt in his mouth; His bark is worse than his bite.

(information was taken from : I. Arnold, The lexicology of contemporary English)

Найдите материал к любому уроку, указав свой предмет (категорию), класс, учебник и тему:

6 209 832 материала в базе

- Выберите категорию:

- Выберите учебник и тему

- Выберите класс:

-

Тип материала:

-

Все материалы

-

Статьи

-

Научные работы

-

Видеоуроки

-

Презентации

-

Конспекты

-

Тесты

-

Рабочие программы

-

Другие методич. материалы

-

Найти материалы

Другие материалы

Презентация по экономической теории «Финансы. Кто я?»

- Учебник: «Экономика. Базовый и углублённый уровни (в 2-х частях) 10-11 классы», Лукашенко М.А., Пашковская М.В., Ионова Ю.Г., Потапова О.Н., Рубин Ю.Б., Соболева И.А., Михненко П.А., Турчанинова Е.В.

- Тема: Раздел (модуль) 12. Финансовая система

- 01.01.2021

- 1222

- 3

- 01.01.2021

- 1337

- 10

- 01.01.2021

- 2967

- 53

- 01.01.2021

- 2286

- 1

- 31.12.2020

- 4530

- 4

- 31.12.2020

- 4411

- 0

Вам будут интересны эти курсы:

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Правовое обеспечение деятельности коммерческой организации и индивидуальных предпринимателей»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Управление персоналом и оформление трудовых отношений»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Методика написания учебной и научно-исследовательской работы в школе (доклад, реферат, эссе, статья) в процессе реализации метапредметных задач ФГОС ОО»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Организация научно-исследовательской работы студентов в соответствии с требованиями ФГОС»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Экскурсоведение: основы организации экскурсионной деятельности»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Финансы: управление структурой капитала»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Источники финансов»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Корпоративная культура как фактор эффективности современной организации»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Деятельность по хранению музейных предметов и музейных коллекций в музеях всех видов»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Риск-менеджмент организации: организация эффективной работы системы управления рисками»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Политология: взаимодействие с органами государственной власти и управления, негосударственными и международными организациями»

MODERN ENGLISH LEXICOLOGY Phraseology. Set-expressions.

Phraseology Phraseology (Gr. phraseos – expression, and logos – word, science) is (1) the branch of linguistics, which studies the nature, features, origin and functioning in speech of set-expressions; (2) all the set-expressions of a given language. V.N. Telija

Phraseology Фразеология – это наука о фразеологических единицах, т.е. об устойчивых сочетаниях слов с осложненной семантикой, не образующихся по порождающим структурно-семантическим моделям переменных сочетаний. А.В. Кунин

The development of Phraseology Ch. Bally U. Weinreich A. Makkai F.F. Fortunatov A.A. Schachmatov V. V. Vinogradov A.V. Kunin A.I. Smirnitsky N.N. Amosova V.N. Telija

Set-expression Set-expression is a word-group consisting of two or more words whose combination is integrated as a unit with a specialized meaning of the whole. Set-expressions are characterized by stability, i.e. their fixed and ready-made nature, and polylexicality, i.e. consisting of more than one lexical unit.

Terminological problem Set-expressions are also called: set phrase (V.V. Vinogradov, semantic approach); idiom (N.N. Amosova, contextual approach); word-equivalent (A.I. Smirnitsky, functional approach); phraseological unit (A.V. Kunin). The differences in terminology reflect the differences in the main criteria used to distinguish between free word-groups and set-expressions.

The problem of differentiation of a free-phrase, semi-fixed phrases and set-expressions There are two major criteria for distinguishing between free phrases and set expressions: semantic and structural. The semantic criterion realizes in possibility or impossibility to deduce the meaning of the whole word-group from the meanings of the constituents. The structural criterion shows in possibility or impossibility of substitution in a word-group.

Free phrases, e.g. to play with a dog, are formed in the flow of speech, contain elements in their individual direct meanings, have independent syntactic functions.

Semi-fixed combinations, e.g. to play with fire (“to do smth dangerously”) are stable ready-made groups the elements of which have separate direct meaning but the whole has the transferred meaning and integral functions. In these combinations we are able to fix and even to list the substitutes existing: e.g. to go to school/market/courts, i.e. it is used only with nouns of place where definite actions are performed.

Set expressions: e.g. The French President refuses to play ball. (coll. “to cooperate with the leader of the other country”). These are ready-made stable word groups, elements make a fixed context for each other to form the whole, with one syntactic function and meaning that is not deduced from the components. No substitution is possible apart from pronominal and synonymic ones: She/he knows on which side her/his bread is buttered (pronominal substitution) To stir/move a finger (synonymic substitution).

Specific features of set-expressions Polylexicality — consist of more than one lexical unit; Structural stability — the components of set expressions are either irreplaceable (e.g. red tape, mare’s nest) or partly replaceable within the bounds of phraseological or phraseomatic variance: lexical (e.g. a skeleton in the cupboard—a skeleton in the closet), grammatical (e.g. to be in deep water—to be in deep waters), positional (e.g. head over ears—over head and ears), quantitative (e.g. to lead smb a dance—to lead smb a pretty dance); Idiomaticity or figurativity — semantic integrity, realized in a special meaning of the whole in the fixed context which can’t be deduced from the meanings of its components: e.g. “to let the cat out of the bag” — “to let some secret become known”.

Specific features of set expressions that add to their stability and cohesion. Rhythmical qualities: — alliteration, or repetition of initial consonants or vowels: part and parcel, then and there, without rhyme or reason; — rhyme: by hook or by crook, wear and tear; — assonance, or the similarity of internal vowels: high and mighty, hard and fast; — reiteration or reduplication:more and more, on and on. Semantic stylistic features: — simile: as like as two peas; — contrast: sooner or later, for love or money; — metaphor: a lame duck, to swallow the pill; — synonymy: by leaps and bounds, proud and haughty; — puns: as cross as two sticks, you lie like a rug.

Principles of classification

Diachronic classification It presents 3 stages of the development of the set expressions: it begins as a free combination; then it becomes clearly motivated metaphoric phrase; finally it is an idiom (i.e. entirely loses the meaning of each component).

”Thematic” classification by L.P. Smith and W. Ball They suggest groups of set expressions used by sailors, fishermen, soldiers, hunters and associated with their occupations; groups of set expressions associated with domestic and wild animals and birds, agriculture and cooking, sports, arts

Synchronic semantic classification by academician V.V. Vinogradov phraseological collocations or combinations — one component is used in its direct meaning, while the other – figuratively: to have a bite, to look a sight, bosom friends; phraseological unities — the meaning of the whole does not correspond to the meanings of its constituents but the metaphor, on which the shift of meaning is based, is clear and transperent: to know the way the wind is blowing, to lose one’s head, a fish out of water, a big bug; phraseological fusions or concretions — they are demotivated, i.e. the meaning of the whole cannot be deduced from the meaning of its components, the metaphor, on which the shift of meaning was based, is obscure: tit for tat, neck and crop, at sixes and sevens.

Structural classification by I.V. Arnold verbal: to make a song and dance about sth, to sit pretty; substantive: dog’s life, calf love, white lie; adjectival: spick and span, brand new, adverbial: high and low, for love or money; interjectional: my God!, good heavens!, sakes alive!

Contextual classification by N.N. Amosova. Phrasemes — stable combinations of words in which either one or both components realise their meaning only in a particular context: black frost (“without snow”), a tall story (“improbable, difficult to believe”); Idioms — the meaning of each component is entirely lost and the new meaning is created by the whole: in the nick of time, red tape.

Classifications based on more than one principle. A.I. Smirnitsky I. one-summit units — have one meaningful constituent: to give up, to be tired; two-summit and multi-summit units — have two or more meaningful constituents: black art, common sense, to fish in the troubled water. II. proper phraseological units or collocations — units with non-figurative meanings, stylistically neutral and in which grammatical and syntactical centres are in one and same place: get up, fall in love; idioms or set expressions — units with transferred meanings based on a metaphor, stylistically coloured and in which grammatical and syntactical centres are in different components: take the bull by the horns, dead as a doornail.

Classification by A.V. Koonin (1) Nominative — word-groups with one meaningful word, coordinative phrases: well and good; word-groups with a predicative structure, such as as the crow flies; predicative phrases of the type see how the land lies (. Interjectional: a pretty kettle of fish! Communicative word-groups are represented by proverbs and sayings: familiarity breeds contempt; Nominative-communicative units include verbal word-groups which are transformed into a sentence when the verb is used in the Passive Voice: to break the ice – the ice is broken.

Classification by A.V. Koonin (2) 3 types of changeability: synonymic variation (contextual synonyms): sugar/sweeten the pill, drop a bomb/brick, run riot/wild; pronominal variation: to give smb/him/her a run for his/her money, make a pig of oneself, to scratch one’s back; synonymic and pronominal variation: give sb a ring/buzz, drown one’s troubles/sorrows, save one’s skin/neck.

Classification by V.N. Telia. phraseology 1 – idioms; phraseology 2 – lexical collocations and restricted collocations or phraseological unities; phraseology 3 – clichés and conversational formulas; phraseology 4 – stock phrases; phraseology 5 – proverbs and sayings; phraseology 6 – quotations.