Murray ventures out to find the word on the street.

What’s the Word on the Street? was a regular feature on Sesame Street from Season 38 to Season 45.

Murray Monster hosts this segment which precedes the corporate sponsor spots before each episode. Each segment begins with a shot of him saying, «Hi, I’m Murray from Sesame Street, and I’m looking for… the Word on the Street!» He then speaks with folks about what today’s word means and usually instructs the audience to «keep listening for the word today on Sesame Street!» The word is later featured in the «street scenes» and highlighted again as the Word of the Day.

Shalom Sesame and Plaza Sésamo have created their own versions of the segment.

In Season 46, the segment was removed and replaced with special cold opens for each episode of different Muppets introducing the topic of the day.

Segments

Season 38

- Squid (First: Episode 4135)

- Newspaper (First: Episode 4136)

- Dog (First: Episode 4137)

- Lazy (First: Episode 4138)

- Pumpernickel (First: Episode 4139)

- Ballet (First: Episode 4140)

- Tricycle (First: Episode 4141)

- Disappear (First: Episode 4142)

- Ticklish (First: Episode 4143)

- Frustrated (First: Episode 4144)

- Prepared (First: Episode 4145)

- Family (First: Episode 4146)

- Mystery (First: Episode 4147)

- Mail (First: Episode 4148)

- Predicament (First: Episode 4149)

- Windy (First: Episode 4150)

- Apology (First: Episode 4151)

- Gigantic (First: Episode 4152)

- Rhyme (First: Episode 4153)

- Amazing (First: Episode 4154)

- Expert (First: Episode 4155)

- Practice (First: Episode 4156)

- Pretend (First: Episode 4157)

- Sigh (First: Episode 4158)

- Angry (First: Episode 4159)

- Struggle (First: Episode 4160)

Season 39

- Octagon (First: Episode 4161)

- Pirouette (First: Episode 4162)

- Laundromat (First: Episode 4163)

- Compliment (First: Episode 4164)

- Insect (First: Episode 4165)

- Subtraction (First: Episode 4166)

- Toss (First: Episode 4167)

- Persistent (First: Episode 4168)

- Unanimous (First: Episode 4169)

- Rhythm (First: Episode 4170)

- Glockenspiel (First: Episode 4171)

- Half (First: Episode 4172)

- Disguise (First: Episode 4173)

- Curly (First: Episode 4174)

- Frightened (First: Episode 4175)

- Stuck (First: Episode 4176)

- Brush (First: Episode 4177)

- Cheer (First: Episode 4178)

- Penguin (First: Episode 4179)

- Mustache (First: Episode 4180)

- Friend (First: Episode 4181)

- Distract (First: Episode 4182)

- Cactus (First: Episode 4183)

- Scrumptious (First: Episode 4184)

- Robot (First: Episode 4185)

- Fabulous (First: Episode 4186)

Season 40

- Habitat (First: Episode 4187)

- Pair (First: Episode 4188)

- Pollinate (First: Episode 4189)

- Nature (First: Episode 4190)

- Season (First: Episode 4191)

- Quest (First: Episode 4192)

- Hibernate (First: Episode 4193)

- Surprise (First: Episode 4194)

- Brilliant (First: Episode 4195)

- Machine (First: Episode 4196)

- Crunchy (First: Episode 4197)

- Garden (First: Episode 4198)

- Camouflage (First: Episode 4199)

- Separate (First: Episode 4200)

- Metamorphosis (First: Episode 4201)

- Canteen (First: Episode 4202)

- Speedy (First: Episode 4203)

- Stumble (First: Episode 4204)

- Inspect (First: Episode 4205)

- Bones (First: Episode 4206)

- Miniature (First: Episode 4207)

- Booth (First: Episode 4208)

- Concentrate (First: Episode 4209)

- Spectacular (First: Episode 4210)

- Humongous (First: Episode 4211)

- Exquisite (First: Episode 4212)

Season 41

- Challenge (First: Episode 4213)

- Journal (First: Episode 4214)

- Comfort (First: Episode 4215)

- Cling (First: Episode 4216)

- Pasta (First: Episode 4217)

- Activate (First: Episode 4218)

- Investigate (First: Episode 4219)

- Appetite (First: Episode 4220)

- Binoculars (First: Episode 4221)

- Float (First: Episode 4222)

- Allergic (First: Episode 4223)

- Hexagon (First: Episode 4224)

- Accessory (First: Episode 4225)

- Arachnid (First: Episode 4226)

- Incognito (First: Episode 4227)

- Recipe (First: Episode 4228)

- Galoshes (First: Episode 4229)

- Identical (First: Episode 4231)

- Healthy (First: Episode 4232)

- Reporter (First: Episode 4233)

- Gem (First: Episode 4234)

- Celebration (First: Episode 4235)

- Volunteer (First: Episode 4236)

- Dozen (First: Episode 4237)

- Transportation (First: Episode 4238)

Season 42

- Engineer (First: Episode 4257)

- Experiment (First: Episode 4258)

- Liquid (First: Episode 4259)

- Observe (First: Episode 4260)

- Transform (First: Episode 4261)

- Baile (Dance) (First: Episode 4262)

- Fragile (First: Episode 4263)

- Exchange (First: Episode 4264)

- Include (First: Episode 4265)

- Empathy (First: Episode 4266)

- Embarrassed (First: Episode 4267)

- Fascinating (First: Episode 4268)

- Sibling (First: Episode 4269)

- Compare (First: Episode 4270)

- Ingredient (First: Episode 4271)

- Balance (First: Episode 4272)

- Amphibian (First: Episode 4273)

- Measure (First: Episode 4274)

- Stubborn (First: Episode 4275)

- Soggy (First: Episode 4276)

- Deciduous (First: Episode 4277)

- Senses (First: Episode 4278)

- Prickly (First: Episode 4279)

- Conflict (First: Episode 4280)

- Magnify (First: Episode 4281)

- Stupendous (First: Episode 4282)

Season 43

- Nibble (First: Episode 4301)

- Champion (First: Episode 4302)

- Remember (First: Episode 4303)

- Careful (First: Episode 4304)

- Patience (First: Episode 4305)

- Grimace (First: Episode 4306)

- Career (First: Episode 4307)

- Tool (First: Episode 4308)

- Proud (First: Episode 4309)

- Veterinarian (First: Episode 4310)

- Vote (First: Episode 4311)

- Brainstorm (First: Episode 4313)

- Paleontologist (First: Episode 4314)

- Splatter (First: Episode 4316)

- Amplify (First: Episode 4317)

- Reinforce (First: Episode 4318)

- Innovation (First: Episode 4319)

- Choreographer (First: Episode 4321)

- Attach (First: Episode 4322)

- Inflate (First: Episode 4324)

- Sculpture (First: Episode 4325)

- Vibrate (First: Episode 4326)

Season 44

- Jealous (First: Episode 4401)

- Respect (First: Episode 4402)

- Fragrance (First: Episode 4403)

- Sturdy (First: Episode 4404)

- Relax (First: Episode 4405)

- Texture (First: Episode 4407)

- Author (First: Episode 4408)

- Furious (First: Episode 4409)

- Impostor (First: Episode 4411)

- Courteous (First: Episode 4412)

- Strategy (First: Episode 4414)

- Translate (First: Episode 4415)

- Disappointed (First: Episode 4417)

- Adventure (First: Episode 4418)

- Unique (First: Episode 4419)

- Confidence (First: Episode 4421)

- Athlete (First: Episode 4423)

- Plan (First: Episode 4424)

- Imagination (First: Episode 4425)

- Absorb (First: Episode 4426)

Season 45

- Strenuous (First: Episode 4501)

- Repair (First: Episode 4502)

- Skin (First: Episode 4503)

- Flexible (First: Episode 4504)

- Enthusiastic (First: Episode 4505)

- Fiesta (First: Episode 4506)

- Diagram (First: Episode 4507)

- Ridiculous (First: Episode 4508)

- Astounding (First: Episode 4509)

- Coach (First: Episode 4510)

- Popular (First: Episode 4511)

- Empty (First: Episode 4512)

- Resist (First: Episode 4513)

- Awful (First: Episode 4514)

- Anxious (First: Episode 4515)

- Pattern (First: Episode 4516)

- Grouchy (First: Episode 4517)

- Friend (First: Episode 4518)

- Divide (First: Episode 4519)

- Artist (First: Episode 4520)

- Greeting (First: Episode 4521)

- Nimble (First: Episode 4522)

- Applause (First: Episode 4523)

- Technology (First: Episode 4524)

- Focus (First: Episode 4525)

- Explore (First: Episode 4526)

Behind the scenes

Chris Lange served as creative director and art director for the segments, Joey Mazzarino as the writer, Jolene Lew as producer, with music composed by Richard W. Meyer of Modern Music, and sound design by Dale Goulett of Wow & Flutter.[1]

Many of the segments were filmed in Brooklyn, New York City.[2]

Carly Tamer, a 6-year-old, was one of the kids in the segments; both the Sesame segment and Team Umizoomi (created by the creators of Blue’s Clues) where Tamer voiced a character, have the same sound crew.[3]

Sources

- ↑ Modern Music press release 9/7/07

- ↑ Brooklyn Daily Eagle 5/4/07

- ↑ Karen Forman, «Enjoying the ride to where talent takes her», Times Beacon Record, 16 October 2008.

See also

- What’s the Word on the Street? (book)

- Lehtšu la Lehono Word on the Street segment on Takalani Sesame

| Sesame Street | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Genre |

|

| Created by |

|

| Theme music composer |

|

| Opening theme | «Can You Tell Me How to Get to Sesame Street?» |

| Ending theme |

|

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language | English |

| No. of seasons | 53 |

| No. of episodes | 4,633[note 1] |

| Production | |

| Executive producers |

|

| Production locations |

|

| Running time |

|

| Production company | Sesame Workshop[note 2] |

| Release | |

| Original network |

|

| Picture format | NTSC (1969–2008) HDTV 1080i (2008–present) |

| Original release | November 10, 1969 – present |

Sesame Street is an American educational children’s television series that combines live-action, sketch comedy, animation and puppetry. It is produced by Sesame Workshop (known as the Children’s Television Workshop until June 2000) and was created by Joan Ganz Cooney and Lloyd Morrisett. It is known for its images communicated through the use of Jim Henson’s Muppets, and includes short films, with humor and cultural references. It premiered on November 10, 1969, to positive reviews, some controversy,[13] and high viewership. It has aired on the United States national public television provider PBS since its debut, with its first run moving to premium channel HBO on January 16, 2016, then its sister streaming service HBO Max in 2020. Sesame Street is one of the longest-running shows in the world.

The show’s format consists of a combination of commercial television production elements and techniques which have evolved to reflect changes in American culture and audiences’ viewing habits. It was the first children’s TV show to use educational goals and a curriculum to shape its content, and the first show whose educational effects were formally studied. Its format and content have undergone significant changes to reflect changes to its curriculum.

Shortly after its creation, its producers developed what came to be called the CTW Model (after the production company’s previous name), a system of planning, production and evaluation based on collaboration between producers, writers, educators and researchers. The show was initially funded by government and private foundations, but has become somewhat self-supporting due to revenues from licensing arrangements, international sales and other media. By 2006, independently produced versions («co-productions») of Sesame Street were broadcast in 20 countries. In 2001, there were over 120 million viewers of various international versions of Sesame Street; and by its 40th anniversary in 2009, it was broadcast in more than 140 countries.

Sesame Street was by then the 15th-highest-rated children’s television show in the United States. A 1996 survey found that 95% of all American preschoolers had watched it by the time they were three. In 2018, it was estimated that 86 million Americans had watched it as children. As of 2022, it has won 222 Emmy Awards and 11 Grammy Awards, more than any other children’s show.[14][15]

History

Sesame Street was conceived in 1966 during discussions between television producer Joan Ganz Cooney and Carnegie Foundation vice president Lloyd Morrisett. Their goal was to create a children’s television show that would «master the addictive qualities of television and do something good with them,»[16] such as helping young children prepare for school. After two years of research, the newly formed Children’s Television Workshop (CTW) received a combined grant of US$8 million ($59 million in 2021 dollars)[17] from the Carnegie Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the U.S. federal government to create and produce a new children’s television show.[18] The program premiered on public television stations on November 10, 1969.[19] It was the first preschool educational television program to base its contents and production values on laboratory and formative research.[20] Initial responses to the show included adulatory reviews, some controversy,[13] and high ratings.

I’ve always said of our original team that developed and produced Sesame Street: Collectively, we were a genius.

—Sesame Street creator Joan Ganz Cooney[21]

According to writer Michael Davis, by the mid-1970s the show had become «an American institution.»[22] The cast and crew expanded during this time, with emphasis on the hiring of women crew members and the addition of minorities to the cast. The show’s success continued into the 1980s. In 1981, when the federal government withdrew its funding, CTW turned to and expanded other revenue sources, including its magazine division, book royalties, product licensing, and foreign broadcast income.[23] Its curriculum has expanded to include more affective topics such as relationships, ethics and emotions. Many of its storylines have been inspired by the experiences of its writing staff, cast and crew—most notably, the 1982 death of Will Lee, who played Mr. Hooper;[24] and the marriage of Luis and Maria in 1988.[25]

By the end of the 1990s, the show faced societal and economic challenges, including changes in young children’s viewing habits, competition from other shows, the development of cable television, and a drop in ratings.[26] As the 21st century began, the show made major changes. Starting in 2002, its format became more narrative-focused and included ongoing storylines. After its 30th anniversary in 1999, due to the popularity of the Muppet Elmo, the show also incorporated a popular segment known as Elmo’s World.[27] In 2009, the show won the Outstanding Achievement Emmy for its 40 years on the air.[28]

In late 2015, in response to «sweeping changes in the media business»[29] and as part of a five-year programming and development deal, premium television service HBO began airing first-run episodes of Sesame Street. The episodes became available on PBS stations and websites nine months after they aired on HBO.[29] The deal allowed Sesame Workshop to produce more episodes—increasing from 18 to 35 per season—and to create a spinoff series with the Sesame Street Muppets, and a new educational series.[30]

At its 50th anniversary in 2019, Sesame Street had produced over 4,500 episodes, two feature-length movies (Follow That Bird in 1985 and The Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland in 1999), 35 TV specials, 200 home videos, and 180 albums.[15] Its YouTube channel has almost five million subscribers.[31] It was announced in October 2019 that first-run episodes will move to HBO Max beginning with the show’s 51st season in 2020.[32]

Format

From its first episode, Sesame Street’s format has utilized «a strong visual style, fast-moving action, humor, and music,» as well as animation and live-action short films.[33] When it premiered, most researchers believed that young children did not have long attention spans, and the show’s producers were concerned that an hour-long show would not hold their attention. At first, its «street scenes»—the action recorded on its set—consisted of character-driven interactions. Rather than ongoing stories, they were written as individual, curriculum-based segments interrupted by «inserts» of puppet sketches, short films and animations. This structure allowed producers to use a mixture of styles and characters, and to vary its pace, presumably keeping it interesting to young viewers. However, by season 20, research showed that children were able to follow a story—and the street scenes, while still interspersed with other segments, became evolving storylines.[34][35]

We basically deconstructed the show. It’s not a magazine format anymore. It’s more like the Sesame hour. Children will be able to navigate through it easier.

—Executive producer Arlene Sherman, speaking of the show’s restructuring in 2002[27]

On recommendations by child psychologists, the producers initially decided that the show’s human actors and Muppets would not interact because they were concerned it would confuse young children.[36] When CTW tested the new show, they found that children paid attention during the Muppet segments, and that their interest was lost during the «Street» segments.[37] They requested that Henson and his team create Muppets such as Big Bird and Oscar the Grouch to interact with the human actors, and the Street segments were re-shot.[38][39]

Sesame Street‘s format remained intact until the 2000s, when the changing audience required that producers move to a more narrative format. In 1998, the popular «Elmo’s World,» a 15-minute-long segment hosted by the Muppet Elmo, was created.[40] Starting in 2014, during the show’s 45th season, the producers introduced a half-hour version of the program.[41][42][43] The new version, which originally complemented the full-hour series, was broadcast weekday afternoons and streamed on the Internet.[41] In 2017, in response to the changing viewing habits of toddlers, the show’s producers decreased the show’s length from one hour to 30 minutes across all its broadcast platforms. The new version focused on fewer characters, reduced pop culture references «once included as winks for their parents», and focused «on a single backbone topic.»[44]

Educational goals

The Sesame Street signpost

Author Malcolm Gladwell said that «Sesame Street was built around a single, breakthrough insight: that if you can hold the attention of children, you can educate them.»[45] Gerald S. Lesser, the CTW’s first advisory board chair, went even further, saying that the effective use of television as an educational tool needed to capture, focus, and sustain children’s attention.[46] Sesame Street was the first children’s show to structure each episode, and the segments within them, to capture children’s attention, and to make, as Gladwell put it, «small but critical adjustments» to keep it.[47] According to CTW researchers Rosemarie Truglio and Shalom Fisch, it was one of the few children’s shows to utilize a detailed and comprehensive educational curriculum, garnered from formative and summative research.[48]

Sesame Street‘s creators and researchers formulated both cognitive and affective goals for the show. They initially focused on cognitive goals, while addressing affective goals indirectly, believing it would increase children’s self-esteem and feelings of competency.[49] One of their primary goals was preparing young children for school, especially children from low-income families,[50] using modeling,[51] repetition,[52] and humor.[46] They adjusted its content to increase viewers’ attention and the show’s appeal,[53] and encouraged older children and parents to «co-view» it by including more sophisticated humor, cultural references, and celebrity guests; by 2019, 80% of parents watched Sesame Street with their children, and 650 celebrities had appeared on the show.[15][54][55]

First Lady Barbara Bush participates with Big Bird in an educational taping of Sesame Street at United Studios, 1989.

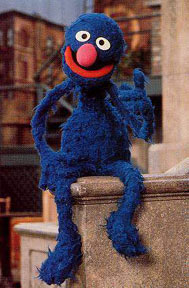

Deputy Secretary of State Antony Blinken meets Grover to discuss refugees at the United Nations in New York City, 2016.

During Sesame Street‘s first season, some critics felt that it should address more overtly such affective goals as social competence, tolerance of diversity, and nonaggressive ways of resolving conflict. The show’s creators and producers responded by featuring these themes in interpersonal disputes between its Street characters.[56] During the 1980s, the show incorporated real-life experiences of its cast and crew, including the death of Will Lee (Mr. Hooper) and the pregnancy of Sonia Manzano (Maria).[24] In later seasons, it addressed real-life disasters such as the September 11 terrorist attacks and Hurricane Katrina.[57]

In its first season, the show addressed its outreach goals by focusing on the promotion of educational materials used in preschool settings; and in subsequent seasons, by focusing on their development. Innovative programs were developed because their target audience, children and their families in low-income, inner-city homes, did not traditionally watch educational programs on television and because traditional methods of promotion and advertising were not effective with these groups.[58]

Starting in 2006, the Workshop expanded its outreach by creating a series of PBS specials and DVDs focusing on how military deployment affects the families of servicepeople.[59] Its outreach efforts also focused on families of prisoners, health and wellness, and safety.[60] In 2013, SW started Sesame Street in Communities, to help families dealing with difficult issues.[61]

Funding

As a result of Cooney’s initial proposal in 1968, the Carnegie Institute awarded her an $1 million grant to create a new children’s television program and establish the CTW,[16][18][62] renamed in June 2000 to Sesame Workshop (SW).

Nixon administration offials argued: we can get Sesame Street to reach poor kids by spending sixty-five cents. Why would we spend thousands of Dollars for Head Start?»[63]

Cooney and Morrisett procured additional multimillion-dollar grants from the U.S. federal government, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, CPB, and the Ford Foundation. Davis reported that Cooney and Morrisett decided that if they did not procure full funding from the beginning, they would drop the idea of producing the show.[64] As Lesser reported, funds gained from a combination of government agencies and private foundations protected them from the economic pressures experienced by commercial broadcast television networks, but created challenges in procuring future funding.[65]

After Sesame Street‘s initial success, its producers began to think about its survival beyond its development and first season and decided to explore other funding sources. From the first season, they understood that the source of their funding, which they considered «seed» money, would need to be replaced.[66] The 1970s were marked by conflicts between the CTW and the federal government; in 1978, the U.S. Department of Education refused to deliver a $2 million check until the last day of CTW’s fiscal year. As a result, the CTW decided to depend upon licensing arrangements with toy companies and other manufacturers, publishing, and international sales for their funding.[23]

In 1998, the CTW accepted corporate sponsorship to raise funds for Sesame Street and other projects. For the first time, they allowed short advertisements by indoor playground manufacturer Discovery Zone, their first corporate sponsor, to air before and after each episode. Consumer advocate Ralph Nader, who had previously appeared on Sesame Street, called for a boycott of the show, saying that the CTW was «exploiting impressionable children.»[19] In 2015, in response to funding challenges, it was announced that premium television service HBO would air first-run episodes of Sesame Street.[29] Steve Youngwood, SW’s Chief Operating Officer, called the move «one of the toughest decisions we ever made.»[67] According to The New York Times, the move «drew an immediate backlash.»[30] Critics claimed that it favored privileged children over less-advantaged children and their families, the original focus of the show. They also criticized choosing to air first-run episodes on HBO, a network with adult dramas and comedies.[30][68]

Production

Research

Producer Joan Ganz Cooney has stated, «Without research, there would be no Sesame Street.»[69]

In 1967, when she and her team began planning the show’s development, combining research with television production was, as she put it, «positively heretical.»[69] Its producers soon began developing what came to be called the CTW Model, a system of planning, production and evaluation that did not fully emerge until the end of the show’s first season.[70][note 3] According to Morrow, the Model consisted of four parts: «the interaction of receptive television producers and child science experts, the creation of a specific and age-appropriate curriculum, research to shape the program directly, and independent measurement of viewers’ learning.»[70]

Cooney credited the show’s high standard in research procedures to Harvard professors Gerald S. Lesser, whom CTW hired to design its educational objectives; and Edward L. Palmer, who conducted the show’s formative research and bridged the gap between producers and researchers.[71] CTW conducted research in two ways: in-house formative research that informed and improved production;[72] and independent summative evaluations, conducted by the Educational Testing Service (ETS) during the first two seasons, which measured its educational effectiveness.[20] Cooney said, «From the beginning, we—the planners of the project—designed the show as an experimental research project with educational advisers, researchers, and television producers collaborating as equal partners.»[73] She characterized the collaboration as an «arranged marriage.»[69]

Writing

Sesame Street has used many writers in its long history. As Peter Hellman wrote in his 1987 article in New York Magazine, «The show, of course, depends upon its writers, and it isn’t easy to find adults who could identify the interest level of a pre-schooler.»[24] Fifteen writers a year worked on the show’s scripts, but very few lasted longer than one season. Norman Stiles, head writer in 1987, reported that most writers would «burn out» after writing about a dozen scripts.[24] According to Gikow, Sesame Street went against the convention of hiring teachers to write for the show, as most educational television programs did at the time. Instead, Cooney and the producers felt that it would be easier to teach writers how to interpret curriculum than to teach educators how to write comedy.[74] As Stone stated, «Writing for children is not so easy.»[74] Long-time writer Tony Geiss agreed, stating in 2009, «It’s not an easy show to write. You have to know the characters and the format and how to teach and be funny at the same time, which is a big, ambidextrous stunt.»[75]

The show’s research team developed an annotated document, or «Writer’s Notebook,» which served as a bridge between the show’s curriculum goals and script development.[76] The notebook was a compilation of programming ideas designed to teach specific curriculum points,[77] provided extended definitions of curriculum goals, and assisted the writers and producers in translating the goals into televised material.[78] Suggestions in the notebook were free of references to specific characters and contexts on the show so that they could be implemented as openly and flexibly as possible.[79]

The research team, in a series of meetings with the writers, also developed «a curriculum sheet» that described the show’s goals and priorities for each season. After receiving the curriculum focus and goals for the season, the writers met to discuss ideas and story arcs for the characters, and an «assignment sheet» was created that suggested how much time was allotted for each goal and topic.[76][80] When a script was completed, the show’s research team analyzed it to ensure that the goals were met. Then each production department met to determine what each episode needed in terms of costumes, lights, and sets. The writers were present during the show’s taping, which for the first twenty-four years of the show took place in Manhattan, and after 1992, at the Kaufman Astoria Studios in Queens to make last-minute revisions when necessary.[81][82][83][note 4]

Media

Early in their history Sesame Street and the CTW began to look for alternative funding sources and turned to creating products and writing licensing agreements. They became, as Cooney put it, «a multiple-media institution.»[86] In 1970, the CTW created a «non-broadcast» division responsible for creating and publishing books and Sesame Street Magazine.[87] By 2019, the Sesame Workshop had published over 6,500 book titles.[31] The Workshop decided from the start that all materials their licensing program created would «underscore and amplify»[88][89] the show’s curriculum. In 2004, over 68% of Sesame Street‘s revenue came from licenses and products such as toys and clothing.[90][note 5] By 2008, the Sesame Street Muppets accounted for between $15 million and $17 million per year in licensing and merchandising fees, split between the Sesame Workshop and The Jim Henson Company.[91] By 2019, the Sesame Workshop had over 500 licensing agreements and had produced over 200 hours of home video.[15][31] There have been two theatrically released Sesame Street movies, Follow That Bird, released in 1985, and Elmo in Grouchland, released in 1999. In early 2019, it was announced that a third film, a musical co-starring Anne Hathaway and written and directed by Jonathan Krisel, would be produced.[92] In November 2019, Sesame Street announced a family friendly augmented reality application produced by Weyo in partnership with Sesame Workshop in honor of the show’s 50th anniversary.[93]

Jim Henson, the creator of the Muppets, owned the trademarks to those characters, and was reluctant to market them at first. He agreed when the CTW promised that the profits from toys, books, computer games, and other products were to be used exclusively to fund the CTW and its outreach efforts.[66][94] Even though Cooney and the CTW had very little experience with marketing, they demanded complete control over all products and product decisions.[88] Any product line associated with the show had to be educational and inexpensive, and could not be advertised during the show’s airings.[95] As Davis reported, «Cooney stressed restraint, prudence, and caution» in their marketing and licensing efforts.[95][note 6]

Director Jon Stone, talking about the music of Sesame Street, said: «There was no other sound like it on television.»[96] For the first time in children’s television, the show’s songs fulfilled a specific purpose and supported its curriculum.[97] In order to attract the best composers and lyricists, the CTW allowed songwriters like Joe Raposo, Sesame Street‘s first musical director, to retain the rights to the songs they wrote, which earned them lucrative profits and helped the show sustain public interest.[98] By 2019, there were 180 albums of Sesame Street music produced, and its songwriters had received 11 Grammys.[15][31] In late 2018, the SW announced a multi-year agreement with Warner Music Group to re-launch Sesame Street Records in the U.S. and Canada. For the first time in 20 years, «an extensive catalog of Sesame Street recordings» was made available to the public in a variety of formats, including CD and vinyl compilations, digital streaming, and downloads.[99]

Sesame Street used animations and short films commissioned from outside studios,[100] interspersed throughout each episode, to help teach their viewers basic concepts like numbers and letters.[101] Jim Henson was one of the many producers to create short films for the show.[100] Shortly after Sesame Street debuted in the United States, the CTW was approached independently by producers from several countries to produce versions of the show at home. These versions came to be called «co-productions.»[102] By 2001 there were over 120 million viewers of all international versions of Sesame Street,[103] and in 2006, there were twenty co-productions around the world.[104] By its 50th anniversary in 2019, 190 million children viewed over 160 versions of Sesame Street in 70 languages.[15][105] In 2005, Doreen Carvajal of The New York Times reported that income from the co-productions and international licensing accounted for $96 million.[90]

Musical

Sesame Street the Musical opened at Theatre Row off Broadway on September 8, 2022 and will run through to November 27, 2022.[106][107]

Cast, crew and characters

Shortly after the CTW was created in 1968, Joan Ganz Cooney was named its first executive director. She was one of the first female executives in American television. Her appointment was called «one of the most important television developments of the decade.»[108] She assembled a team of producers, all of whom had previously worked on Captain Kangaroo. Jon Stone was responsible for writing, casting, and format; Dave Connell took over animation; and Sam Gibbon served as the show’s chief liaison between the production staff and the research team.[109] Cameraman Frankie Biondo has worked on Sesame Street from its first episode in 1969.[110]

Jim Henson and the Muppets’ involvement in Sesame Street began when he and Cooney met at one of the curriculum planning seminars in Boston. Author Christopher Finch reported that Stone, who had worked with Henson previously, felt that if they could not bring him on board, they should «make do without puppets.»[18] Henson was initially reluctant, but he agreed to join Sesame Street to meet his own social goals. He also agreed to waive his performance fee for full ownership of the Sesame Street Muppets and to split any revenue they generated with the CTW.[91] As Morrow stated, Henson’s puppets were a crucial part of the show’s popularity and it brought Henson national attention.[111] Davis reported that Henson was able to take «arcane academic goals» and translate them to «effective and pleasurable viewing.»[112] In early research, the Muppet segments of the show scored high, and more Muppets were added during the first few seasons. Morrow reported that the Muppets were effective teaching tools because children easily recognized them, they were stereotypical and predictable, and they appealed to adults and older siblings.[113]

Sesame Street is best known for the creative geniuses it attracted, people like Jim Henson and Joe Raposo and Frank Oz, who intuitively grasped what it takes to get through to children. They were television’s answer to Beatrix Potter or L. Frank Baum or Dr. Seuss.

—Author Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point[114]

Although the producers decided against depending upon a single host for Sesame Street, instead casting a group of ethnically diverse actors,[115] they realized that a children’s television program needed to have, as Lesser put it, «a variety of distinctive and reliable personalities,»[116] both human and Muppet. Jon Stone, whose goal was to cast white actors in the minority,[24] was responsible for hiring the show’s first cast. He did not audition actors until Spring 1969, a few weeks before the five test shows were due to be filmed. Stone videotaped the auditions, and Ed Palmer took them out into the field to test children’s reactions. The actors who received the «most enthusiastic thumbs up» were cast.[117] For example, Loretta Long was chosen to play Susan when the children who saw her audition stood up and sang along with her rendition of «I’m a Little Teapot.»[117][118] Stone stated that casting was the only aspect of the show that was «just completely haphazard.»[89] Most of the cast and crew found jobs on Sesame Street through personal relationships with Stone and the other producers.[89] According to puppeteer Marty Robinson in 2019, longevity was common among the show’s cast and crew.[31]

According to the CTW’s research, children preferred watching and listening to other children more than to puppets and adults, so they included children in many scenes.[119] Dave Connell insisted that no child actors be used,[120] so these children were non-professionals, unscripted, and spontaneous. Many of their reactions were unpredictable and difficult to control, but the adult cast learned to handle the children’s spontaneity flexibly, even when it resulted in departures from the planned script or lesson.[121] CTW research also revealed that the children’s hesitations and on-air mistakes served as models for viewers.[122] According to Morrow, this resulted in the show having a «fresh quality,» especially in its early years.[120]

Reception

Ratings

When Sesame Street premiered on November 10, 1969, it aired on only 67.6% of American televisions, but it earned a 3.3 Nielsen rating, which totaled 1.9 million households.[123] By the show’s tenth anniversary in 1979, nine million American children under the age of 6 were watching Sesame Street daily. According to a 1993 survey conducted by the U.S. Department of Education, out of the show’s 6.6 million viewers, 2.4 million kindergartners regularly watched it. 77% of preschoolers watched it once a week, and 86% of kindergartners and first- and second-grade students had watched it once a week before starting school. The show reached most young children in almost all demographic groups.[124]

The show’s ratings significantly decreased in the early 1990s, due to changes in children’s viewing habits and in the television marketplace. The producers responded by making large-scale structural changes to the show.[125] By 2006, Sesame Street had become «the most widely viewed children’s television show in the world,» with 20 international independent versions and broadcasts in over 120 countries.[126] A 1996 survey found that 95% of all American preschoolers had watched the show by the time they were three years old.[127] In 2008, it was estimated that 77 million Americans had watched the series as children.[126] By the show’s 40th anniversary in 2009, it was ranked the fifteenth-most-popular children’s show on television, and by its 50th anniversary in 2019, the show had 100% brand awareness globally. In 2018, the show was the second-highest-rated program on PBS Kids.[128][105] In 2021, however, the Sesame Street documentary «50 Years of Sunny Days,» which was broadcast nationally on ABC, did not fare well in the ratings,[129] scoring only approximately 2.3 million viewers.[130]

Influence

As of 2001, there were over 1,000 research studies regarding Sesame Street‘s efficacy, impact, and effect on American culture.[71] The CTW solicited the Educational Testing Service (ETS) to conduct summative research on the show.[131] ETS’s two «landmark»[132] summative evaluations, conducted in 1970 and 1971, demonstrated that the show had a significant educational impact on its viewers.[133] These studies have been cited in other studies of the effects of television on young children.[131][note 7] Additional studies conducted throughout Sesame Street‘s history demonstrated that the show continued to have a positive effect on its young viewers.[note 8]

Sesame Street [is] perhaps the most vigorously researched, vetted, and fretted-over program on the planet. It would take a fork-lift to now to haul away the load of scholarly paper devoted to the series…

—Author Michael Davis[134]

Lesser believed that Sesame Street research «may have conferred a new respectability upon the studies of the effects of visual media upon children.»[135] He also believed that the show had the same effect on the prestige of producing shows for children in the television industry.[135] Historian Robert Morrow, in his book Sesame Street and the Reform of Children’s Television, which chronicled the show’s influence on children’s television and on the television industry as a whole, reported that many critics of commercial television saw Sesame Street as a «straightforward illustration for reform.»[136] Les Brown, a writer for Variety, saw in Sesame Street «a hope for a more substantial future» for television.[136]

Morrow reported that the networks responded by creating more high-quality television programs, but that many critics saw them as «appeasement gestures.»[137] According to Morrow, despite the CTW Model’s effectiveness in creating a popular show, commercial television «made only a limited effort to emulate CTW’s methods,» and did not use a curriculum or evaluate what children learned from them.[138] By the mid-1970s commercial television had abandoned their experiments with creating better children’s programming.[139] Other critics hoped that Sesame Street, with its depiction of a functioning, multicultural community, would nurture racial tolerance in its young viewers.[140] It was not until the mid-1990s that another children’s television educational program, Blue’s Clues, used the CTW’s methods to create and modify their content. The creators of Blue’s Clues were influenced by Sesame Street, but wanted to use research conducted in the 30 years since its debut. Angela Santomero, one of its producers, said, «We wanted to learn from Sesame Street and take it one step further.»[141]

Critic Richard Roeper said that perhaps one of the strongest indicators of the influence of Sesame Street has been the enduring rumors and urban legends surrounding the show and its characters, especially speculation concerning the sexuality of Bert and Ernie.[142][143]

Critical reception

Sesame Street was praised from its debut in 1969. Newsday reported that several newspapers and magazines had written «glowing» reports about the CTW and Cooney.[123] The press overwhelmingly praised the new show; several popular magazines and niche magazines lauded it.[144] In 1970, Sesame Street won twenty awards, including a Peabody Award, three Emmys, an award from the Public Relations Society of America, a Clio, and a Prix Jeunesse.[145] By 1995, the show had won two Peabody Awards and four Parents’ Choice Awards. It was the subject of a traveling exhibition by the Smithsonian Institution,[146] and a film exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.[147]

Sesame Street is … with lapses, the most intelligent and important program in television. That is not anything much yet.

—Renata Adler, The New Yorker, 1972[148]

Sesame Street was not without its detractors, however. The state commission in Mississippi, where Henson was from, operated the state’s PBS member station; in May 1970 it voted to not air Sesame Street because of its «highly [racially] integrated cast of children» which «the commission members felt … Mississippi was not yet ready for.»[149][150] According to Children and Television, Lesser’s account of the development and early years of Sesame Street, there was little criticism of the show in the months following its premiere, but it increased at the end of its first season and beginning of the second season.[151][note 9] Historian Robert W. Morrow speculated that much of the early criticism, which he called «surprisingly intense,»[13] stemmed from cultural and historical reasons in regards to, as he put it, «the place of children in American society and the controversies about television’s effects on them.»[13]

According to Morrow, the «most important» studies finding negative effects of Sesame Street were conducted by educator Herbert A. Sprigle and psychologist Thomas D. Cook during its first two seasons.[152] Social scientist and Head Start founder Urie Bronfenbrenner criticized the show for being too wholesome.[153] Psychologist Leon Eisenberg saw Sesame Street‘s urban setting as «superficial» and having little to do with the problems confronted by the inner-city child.[154] Head Start director Edward Zigler was probably Sesame Street‘s most vocal critic in the show’s early years.[155]

In spite of their commitment to multiculturalism, the CTW experienced conflicts with the leadership of minority groups, especially Latino groups and feminists, who objected to Sesame Street‘s depiction of Latinos and women.[156] The CTW took steps to address their objections. By 1971, the CTW hired Hispanic actors, production staff, and researchers, and by the mid-1970s, Morrow reported that «the show included Chicano and Puerto Rican cast members, films about Mexican holidays and foods, and cartoons that taught Spanish words.»[157] As The New York Times has stated, creating strong female characters «that make kids laugh, but not…as female stereotypes» has been a challenge for the producers of Sesame Street.[158] According to Morrow, change regarding how women and girls were depicted on Sesame Street occurred slowly.[159] As more female Muppet performers like Camille Bonora, Fran Brill, Pam Arciero, Carmen Osbahr, Stephanie D’Abruzzo, Jennifer Barnhart, and Leslie Carrara-Rudolph were hired and trained, stronger female characters like Rosita and Abby Cadabby were created.[160][161]

In 2002, Sesame Street was ranked number 27 on TV Guide’s 50 Greatest TV Shows of All Time.[162] Sesame Workshop won a Peabody Award in 2009 for its website, sesamestreet.org,[163] and the show was given Peabody’s Institutional Award in 2019 for 50 years of educating and entertaining children globally.[164] In 2013, TV Guide ranked the show number 30 on its list of the 60 best TV series.[165] As of 2021, Sesame Street has received 205 Emmy Awards, more than any other television series.[166]

See also

- List of accolades received by Sesame Street

- List of human Sesame Street characters

- List of songs from Sesame Street

- Sesame Street (comic strip)

- Sesame Street international co-productions

- The Not Too Late Show with Elmo

- Julia (Sesame Street)

- Mecha Builders

References

Informational notes

- ^ Season 44 (2013–2014) was the first time episodes were numbered in a seasonal order rather than the numerical and chronological fashion used since the show premiered. For example, episode 4401 means «the first episode of the 44th season», not «the 4401st episode» (it is in fact the 4328th episode).

- ^ Known as Children’s Television Workshop until 2000.

- ^ See Gikow, p. 155, for a visual representation of the CTW model.

- ^ Most of the first season was filmed at a studio near Broadway, but a strike forced their move to Teletape Studios. In the early days, the set was simple, consisting of four structures.[84] In 1982, Sesame Street began filming at Unitel Studios on 57th Street, but relocated to Kaufman Astoria Studios in 1993, when the producers decided they needed more space.[85]

- ^ See Gikow, pp. 280–285 for a list of many of the show’s products.

- ^ According to Parade Magazine in 2019, 1 million children played with Sesame Street toys daily.[15]

- ^ According to Edward Palmer and his colleague Shalom M. Fisch, these studies were responsible for securing funding for the show over the next several years.[133]

- ^ See Gikow, pp. 284–285; «G» Is for Growing: Thirty Years of Research on Children and Sesame Street, pp. 147–230.

- ^ See Lesser, pp. 175–201 for his response to the early critics of Sesame Street.

Citations

- ^ «Sesame Street season 1 End Credits (1969-70)». YouTube.com. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ «Sesame Street season 3 End Credits (1971-72)». YouTube.com. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ «Sesame Street season 4 End Credits (1972-73)». YouTube.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ «Sesame Street season 9 end credits (1977-78)». YouTube.com. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ «Sesame Street season 10 end credits (1978-79)». YouTube.com. Archived from the original on October 8, 2012. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ «Sesame Street season 12 end credits (1980-81)». YouTube.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ «Sesame Street season 24 (#3010) closing & funding credits (1992) [«Dancing City» debut]». YouTube.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ «Sesame Street — Season 25 End Credits (1993-1994)». YouTube.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ «Elmo Writes a Story — Sesame Street Full Episode (credits start at 55:37)». YouTube.com. Sesame Street. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ «Sesame Street Season 34 credits & fundings (version #1)». YouTube.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ «Elmo and Zoe Play the Healthy Food Game — Sesame Street Full Episodes (credits start at 52:50)». YouTube.com. Sesame Street. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ «PBS Kids Program Break (2006 WFWA-TV)». YouTube.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Morrow, p. 3

- ^ «Sesame Street Co-Founder Lloyd Morrisett Dies Aged 93». No. Virgin Radio UK. January 25, 2023. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wallace, Debra (February 6, 2019). «Big Bird Has 4,000 Feathers: 21 Fun Facts About Sesame Street That Will Blow Your Mind». Parade. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

- ^ a b Davis, p. 8

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. «Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–». Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c Finch, p. 53

- ^ a b Brooke, Jill (November 13, 1998). «‘Sesame Street’ Takes a Bow to 30 Animated Years». The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ a b Palmer & Fisch in Fisch & Truglio, p. 9

- ^ Gikow, p. 26

- ^ Davis, p. 220

- ^ a b O’Dell, pp. 73–74

- ^ a b c d e Hellman, Peter (November 23, 1987). «Street Smart: How Big Bird & Company Do It». New York Magazine. 20 (46): 52. ISSN 0028-7369. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ Borgenicht, p. 80

- ^ Davis, p. 320

- ^ a b Goodman, Tim (February 4, 2002). «Word on the ‘Street’: Classic children’s show to undergo structural changes this season». San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ Eng, Joyce (August 28, 2009). «Guiding Light, Sesame Street to Be Honored at Daytime Emmys». TV Guide. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c Pallotta, Frank; Stelter, Brian (August 13, 2015). «‘Sesame Street’ is heading to HBO». CNN.com. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c Steel, Emily (August 13, 2015). «‘Sesame Street’ to Air First on HBO for Next 5 Seasons». The New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Guthrie, Marisa (February 6, 2019). «50 Years of Sunny Days on ‘Sesame Street’: Behind the Scenes of TV’s Most Influential Show Ever». The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ Alexander, Julia (October 3, 2019). «HBO Max locks down exclusive access to new Sesame Street episodes». The Verge. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ O’Dell, p. 70

- ^ Morrow, p. 87

- ^ Gikow, p. 179

- ^ Fisch & Bernstein, p. 39

- ^ Gladwell, p. 105

- ^ Gladwell, p. 106

- ^ Fisch & Bernstein, pp. 39–40

- ^ Clash, p. 75

- ^ a b Dockterman, Eliana (June 18, 2014). «We’re Getting a Half-Hour Version of Sesame Street». Time. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ «PBS KIDS to Add New Half-hour SESAME STREET Program on Air and on Digital Platforms This Fall». PBS Pressroom. June 18, 2014. Archived from the original on February 5, 2022. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ Jensen, Elizabeth (June 17, 2014). «PBS Plans to Add a Shorter Version of ‘Sesame Street’«. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ Harwell, Drew (January 12, 2016). «Sesame Street, newly revamped for HBO, aims for toddlers of the Internet age». The Washington Post. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- ^ Gladwell, p. 100

- ^ a b Lesser, p. 116

- ^ Gladwell, p. 91

- ^ Fisch, Shalom M.; Rosemarie T. Truglio (2001). «Why Children Learn from Sesame Street». In Shalom M. Fisch; Rosemarie T. Truglio (eds.). «G» is for Growing: Thirty Years of Research on Children and Sesame Street. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. p. 234. ISBN 0-8058-3395-1.

- ^ Morrow, pp. 76, 106

- ^ Lesser, p. 46

- ^ Lesser, pp. 86–87

- ^ Lesser, p. 107

- ^ Lesser, p. 87

- ^ «‘Sesame Street’ Draws in Adults with Pop Culture Parodies». yahoo.com. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ Truglio, Rosemarie T.; Kotler, Jennifer A. (2013). «Language, Literacy, and Media: What’s the Word on Sesame Street?». In Gershoff, E. T.; Mistry, R. S.; Crosby, D. A. (eds.). Societal Contexts of Child Development: Pathways of Influence and Implications for Practice and Policy. pp. 188–202. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199943913.003.0012.

- ^ Huston, Aletha C; Daniel R. Anderson; John C. Wright; Deborah Linebarger; Kelly L. Schmidt (2001). «»Sesame Street Viewers as Adolescents: The Recontact Study». In Shalom M. Fisch; Rosemarie T. Truglio (eds.). «G» is for Growing: Thirty Years of Research on Children and Sesame Street. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. p. 133. ISBN 0-8058-3395-1.

- ^ Gikow, p. 165

- ^ Gikow, p. 181

- ^ Gikow, pp. 280–281

- ^ Gikow, pp. 286–293

- ^ Chandler, Michael Alison (October 6, 2017). «Sesame Street launches tools to help children who experience trauma, from hurricanes to violence at home». The Washington Post. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ Palmer & Fisch in Fisch & Truglio, p. 3

- ^ Melissa S. Kearney and Phillip B. Levine (2015). «Early Childhood Education by MOOC: Lessons from Sesame Street» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 8, 2015.

- ^ Davis, p. 105

- ^ Lesser, p. 17

- ^ a b Davis, p. 203

- ^ Guthrie, Marisa (February 6, 2019). «Where ‘Sesame Street’ Gets Its Funding — and How It Nearly Went Broke». The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Luckerson, Victor (August 13, 2019). «This Is Why HBO Really Wants Sesame Street». Time. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c Cooney in Fisch & Truglio, p. xi

- ^ a b Morrow, p. 68

- ^ a b Cooney in Fisch & Truglio, p. xii

- ^ Mielke in Fisch & Truglio, pp. 84–85

- ^ Borgenicht, p. 9

- ^ a b Gikow, p. 178

- ^ Gikow, p. 174

- ^ a b Lesser, p. 101

- ^ Morrow, p. 82

- ^ Palmer & Fisch in Fisch & Truglio, p. 10

- ^ Palmer & Fisch in Fisch & Truglio, p. 11

- ^ Lesser, Gerald S.; Joel Schneider (2001). «Creation and Evolution of the Sesame Street Curriculum». In Shalom M. Fisch; Rosemarie T. Truglio (eds.). «G» is for Growing: Thirty Years of Research on Children and Sesame Street. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. p. 28. ISBN 0-8058-3395-1.

- ^ Murphy, Tim (November 1, 2009). «How We Got to ‘Sesame Street’«. New York Magazine. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ «How to Get to ‘Sesame Street’ at the Apollo Theater». New York City Mayor’s Office. November 19, 2008. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Spinney, Caroll; Jason Milligan (2003). The Wisdom of Big Bird (and the Dark Genius of Oscar the Grouch): Lessons from a Life in Feathers. New York: Random House. p. 3. ISBN 0-375-50781-7.

- ^ Gikow, pp. 66–67

- ^ Gikow, pp. 206–207

- ^ Cherow-O’Leary in Fisch & Truglio, p. 197

- ^ Cherow-O’Leary in Fisch & Truglio, pp. 197–198

- ^ a b Davis, p. 205

- ^ a b c Davis, p. 195

- ^ a b Carvajal, Doreen (December 12, 2005). «Sesame Street Goes Global: Let’s All Count the Revenue». The New York Times. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ a b Davis, p. 5

- ^ Kit, Borys; Sandberg, Bryn Elise (February 6, 2019). «‘Sesame Street’ Movie’s Writer-Director Reveals Plot Details». The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ Damiani, Jesse. «Sesame Street Launches 50th Anniversary AR App». Forbes. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ Gikow, p. 268

- ^ a b Davis, p. 204

- ^ Gikow, p. 220

- ^ Gikow, p. 227

- ^ Davis, p. 256

- ^ «Warner Music Group Sesame Workshop Team up to Relaunch Sesame Street Records». Music Business Worldwide. November 27, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ a b Gikow, p. 236

- ^ Morrow, p. 89

- ^ Cole et al. in Fisch & Truglio, p. 148

- ^ Cole et al. in Fisch & Truglio, p. 147

- ^ Knowlton, Linda Goldstein and Linda Hawkins Costigan (producers) (2006). The World According to Sesame Street (documentary). Participant Productions.

- ^ a b Bradley, Diana (July 27, 2018). «Leaving the neighborhood: ‘Sesame Street’ muppets to travel across America next year». PR Weekly. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ «Sesame Street the Musical». sesamestreetmusical.com. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ «SESAME STREET MUSICAL — Rumours of a West End transfer». London Box Office. November 18, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ Davis, pp. 128–129

- ^ Davis, p. 147

- ^ Gikow, p. 15

- ^ Morrow, p. 93

- ^ Davis, p. 163

- ^ Morrow, pp. 94–95

- ^ Gladwell, p. 99

- ^ Lesser, p. 99

- ^ Lesser, p. 125

- ^ a b Borgenicht, p. 15

- ^ Davis, p. 172

- ^ Lesser, p. 127

- ^ a b Morrow, p. 84

- ^ Lesser, pp. 127–128

- ^ Gikow, p. 123

- ^ a b Seligsohn, Leo. (February 9, 1970). «Backstage at Sesame Street». New York Newsday. Quoted in Davis, p. 197.

- ^ Zill, Nicholas (2001). «Does Sesame Street Enhance School Readiness? Evidence from a National Survey of Children». «G» is for Growing: Thirty Years of Research on Children and Sesame Street. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. pp. 117–120. ISBN 0-8058-3395-1.

- ^ Weiss, Joanna (October 19, 2005). «New Character Joins PBS». The Boston Globe. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ a b Friedman, Michael Jay (April 8, 2006). «Sesame Street Educates and Entertains Internationally» (PDF). America.gov. U.S. Department of State Bureau of International Information Programs. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 15, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ Truglio, Rosemarie T; Shalom M. Fisch (2001). «Introduction». In Shalom M. Fisch; Rosemarie T. Truglio (eds.). «G» is for Growing: Thirty Years of Research on Children and Sesame Street. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. p. xvi. ISBN 0-8058-3395-1.

- ^ Guernsey, Lisa (May 23, 2009). «How Sesame Street Changed the World». Newsweek. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Magilo, Tony (April 27, 2021). «Ratings: ‘Sesame Street’ Documentary Does Not Bring Sunny Days to ABC». The Wrap. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Metcalf, Mitch (April 27, 2021). «UPDATED:SHOWBUZZDAILY’s Top 150 Monday Cable Originals and Network Finals». Showbuzz Daily. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Mielke in Fisch & Truglio, p. 85

- ^ Mielke in Fisch & Truglio, p. 88

- ^ a b Palmer & Fisch in Fisch & Truglio, p. 20

- ^ Davis, p. 357

- ^ a b Lesser, p. 235

- ^ a b Morrow, p. 122

- ^ Morrow, p. 127

- ^ Morrow, p. 130

- ^ Morrow, p. 132

- ^ Morrow, p. 124

- ^ Gladwell, p. 111

- ^ Roeper, Richard (2001). Hollywood Urban Legends: The Truth Behind All Those Delightfully Persistent Myths of Film, Television and Music. Franklin Lakes, New Jersey: Career Press. pp. 48–53. ISBN 1-56414-554-9.

- ^ «Bert and Ernie sexuality debate rages». BBC News. September 18, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ Morrow, pp. 119–120

- ^ Morrow, p. 119

- ^ Graeber, Laurel (August 18, 2011). «And a Frog Shall Lead Them: Henson’s Legacy». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 30, 2022 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ «WEEKENDER GUIDE». The New York Times. November 10, 1989. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 30, 2022 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Lesser, p. 165

- ^ «Mississippi Agency Votes for a TV Ban on ‘Sesame Street'». (May 3, 1970). The New York Times. Quoted in Davis, p. 202

- ^ «Mississippi Agency Votes for a TV Ban On ‘Sesame Street’«. The New York Times. May 3, 1970.

- ^ Lesser, pp. 174–175

- ^ Morrow, pp. 146–147

- ^ Kanfer, Stefan (November 23, 1970). «Who’s Afraid of Big, Bad TV?». Time. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ Morrow, p. 98

- ^ Morrow, p. 147

- ^ Morrow, pp. 157–158

- ^ Morrow, p. 155

- ^ Gikow, p. 142

- ^ Morrow, p. 156

- ^ Gikow, p. 143

- ^ Olivera, Monica (September 20, 2013). «Carmen Osbahr, the talented puppeteer behind Sesame Street’s «Rosita»«. NBC Universal. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ «TV Guide Names Top 50 Shows». CBS News. Associated Press. February 11, 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ «2009 Sesame Workshop». Peabody Awards. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ^ Turchiano, Danielle (April 18, 2019). «‘Barry,’ ‘Killing Eve,’ ‘Pose’ Among 2019 Peabody Winners». Variety. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ^ Fretts, Bruce; Roush, Matt (December 23, 2013). «TV Guide Magazine’s 60 Best Series of All Time». Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ^ «Joan Ganz Cooney: Co-Founder and Lifetime Honorary Trustee». Sesame Workshop. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

General and cited references

- Borgenicht, David (1998). Sesame Street Unpaved. New York: Hyperion Publishing. ISBN 0-7868-6460-5

- Clash, Kevin, Gary Brozek, and Louis Henry Mitchell (2006). My Life as a Furry Red Monster: What Being Elmo has Taught Me About Life, Love and Laughing Out Loud. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-7679-2375-8

- Davis, Michael (2008). Street Gang: The Complete History of Sesame Street. New York: Viking Penguin. ISBN 978-0-670-01996-0.

- Finch, Christopher (1993). Jim Henson: The Works, the Art, the Magic, the Imagination. New York: Random House. ISBN 9780679412038

- Fisch, Shalom M. and Rosemarie T. Truglio, Eds. (2001). «G» Is for Growing: Thirty Years of Research on Children and Sesame Street. Mahweh, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. ISBN 0-8058-3395-1

- Cooney, Joan Ganz, «Foreword», pp. xi–xiv.

- Palmer, Edward and Shalom M. Fisch, «The Beginnings of Sesame Street Research», pp. 3–24.

- Fisch, Shalom M. and Lewis Bernstein, «Formative Research Revealed: Methodological and Process Issues in Formative Research», pp. 39–60.

- Mielke, Keith W., «A Review of Research on the Educational and Social Impact of Sesame Street», pp. 83–97.

- Cole, Charlotte F., Beth A. Richman, and Susan A. McCann Brown, «The World of Sesame Street Research», pp. 147–180.

- Cherow-O’Leary, Renee, «Carrying Sesame Street into Print: Sesame Street Magazine, Sesame Street Parents, and Sesame Street Books», pp. 197–214.

- Gikow, Louise A. (2009). Sesame Street: A Celebration— Forty Years of Life on the Street. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. ISBN 978-1-57912-638-4.

- Gladwell, Malcolm (2000). The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. New York: Little, Brown, and Company. ISBN 0-316-31696-2

- Lesser, Gerald S. (1974). Children and Television: Lessons From Sesame Street. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-71448-2

- Morrow, Robert W. (2006). Sesame Street and the Reform of Children’s Television. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8230-3

- O’Dell, Cary (1997). Women Pioneers in Television: Biographies of Fifteen Industry Leaders. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-0167-2.

External links

- Official website

- Sesame Street at IMDb

- Sesame Street on Muppet Wiki

- Sesame Street at Curlie

- Sesame Street on PBSKids.org

- Sesame Street at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

- Abdelfatah, Rund; Ramtin Arablouei; et al. (September 15, 2022). «Getting to Sesame Street». Throughline. National Public Radio. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

Sesame Street Muppet Characters

Sesame Street Human Characters

Autistic Sesame Street Character

Original Sesame Street Characters

Orange Sesame Street Characters

Female Sesame Street Characters

Blue Sesame Street Characters

Sesame Street Characters (Muppets)

Here are the favorite characters of Sesame Street in order of popularity. Ranking is based on internet search results in the USA:

26. Gonger:

Gonger joined the cast in the 48th season after previously appearing in The Furchester Hotel. He works with Cookie Monster in the «Cookie Monster’s Foodie Truck» segment, taking food orders from children. The character of Gonger is performed by Warrick Brownlow-Pike.

25. Curly Bear:

She first appeared on Sesame Street in season 34. She is Baby Bear’s sister. Curly Bear, unlike other bears in the family, does not like porridge. But she’s definitely one of the cutest characters on Sesame Street.

24. Dorothy:

Dorothy isn’t actually a muppet character. But she should have been added to that list. Because she is a character we know from Elmo’s World series. Dorothy has a great imagination and can imagine Elmo as a different character each time. An excellent talent.

23. Baby Bear:

Baby Bear appears on Sesame Street in the 1990s. This sweet bear can’t pronounce R sounds correctly. As an art-loving bear and the older brother of Curly Bear, he made it to this list.

22. Prairie Dawn:

Prairie Dawn is one of the oldest characters on the show, having appeared on Sesame Street since season 2. Luckily, as a Muppet, she doesn’t age, which is a stroke of good luck for her. Prairie Dawn is known for writing and directing plays for her schoolmates in the Classic Sesame Street episodes. In the «Letter of the Day» episodes in seasons 33 and 35, she tries to stop Cookie Monster from eating the letter of the day, but of course, she never succeeds.

21. Rocco:

Rocco is a rock, but not just any rock — he’s Zoe’s beloved pet rock. Zoe is convinced that Rocco can talk and even has a life of his own. Elmo often reminds Zoe that Rocco is just a rock, but Zoe remains steadfast in her belief. In one episode, Cookie Monster almost mistook Rocco for a cookie and nearly ate him! Poor Rocco, he always seems to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

20. Rudy:

Rudy is a cute, orange-colored monster with small horns who made his first appearance on Sesame Street in season 47. He is Abby Cadabby’s stepbrother and quickly became a beloved character among fans. In his debut episode, «Hello Rudy» (4731), Rudy meets many of the Sesame Street residents for the first time and starts to explore the neighborhood. He’s known for his energetic and adventurous personality, and often joins his step-sister Abby in her magical adventures. Despite his mischievous streak, Rudy always tries to do the right thing and help his friends.

19. Two-Headed Monster:

«What would it be like to have two heads? One head saying ‘We have to go right,’ while the other argues, ‘No, you idiot, we’re going left!’ The Two-Headed Monster often appears behind a wall, as the puppeteers performing it are in a tricky situation. This character frequently demonstrates the meaning of words on Sesame Street.»

18. Julia:

Julia is undoubtedly one of Sesame Street’s most meaningful characters. She is a close friend of Elmo and Abby and is a girl with autism. She shows us that autism isn’t a disease, it’s just a little bit different. Julia is seen for the first time in episode 4715, «Meet Julia», and she has a toy bunny that she loves very much. You are amazing Julia and we are always with you!

17. Rosita:

Hola

16. Rubber Duckie:

Rubber Duckie is Ernie’s toy duck. It is often the main theme in Ernie’s songs and is more than just an ordinary toy; it’s his friend. However, it isn’t as close a friend as Bert is. As the famous Sesame Street song goes: ‘Oh, Rubber Ducky, you’re the one. You make bath time lots of fun…’ la la la laaaaaaa

15. Mr. Snuffleupagus:

His friends call him Snuffy. He has been a part of the Sesame Street character cast since Season 3 and gets along well with Big Bird. In the early seasons of the show, he was known by the human characters as an imaginary friend of Big Bird’s. It wasn’t until season 17 that Snuffy met adults for the first time, proving that he wasn’t just a figment of Big Bird’s imagination. Snuffy’s giant body requires two puppeteers to operate. We’re glad to have you with us, big friend!

14. Telly Monster:

Telly takes his name from the word ‘television.’ He was originally conceived as a monster addicted to TV. However, this was deemed pedagogically wrong and the character was changed. Telly gained popularity when Caroll Spinney, the performer for Big Bird, injured his foot and was unable to appear in the series. Telly is a Muppet who loves triangles and is often portrayed as insecure and anxious. He owns a hamster named Chuckie Sue. Telly’s enthusiastic demeanor is really endearing!

13. Murray Monster:

Murray was initially referred to as the ‘Orange Monster’ on the show. He hosted the ‘What’s the Word on the Street’ segment and also appeared in the segment ‘Murray Has a Little Lamb’ with his lamb named Ovejita. With changes to the show’s format after 2015, he moved away from the active Muppet cast of the series. We miss you, Murray. Maybe one day you will rejoin us.

12. Zoe:

Zoe is another orange monster from Sesame Street and has been a part of the cast since season 25. She loves ballet and dancing and is sometimes seen wearing a tutu. Zoe has an imaginary friendship with her rock named Rocco. She is an idol for preschool girls who love to dance and move.

11. Guy Smiley:

Guy Smiley is known for hosting game shows on Sesame Street. He is orange-gold in color and is one of the oldest characters in the series, having first appeared in 1969. Some of the shows he has hosted include: ‘What’s My Part?’, ‘Beat the Time’, ‘Name That Sound!’, ‘The Mr. and Mrs. Game’, ‘The Matching Game’, ‘Double Get Wordy’, ‘Hurry Up! You’re Running Out of Time!’, ‘The Big Trip’, ‘Estimation Vacation’, ‘The Waiting Game’, ‘Make it Fit’, and ‘What’s My Job?’ It’s always a pleasure to watch your shows, Guy!

10. Count von Count:

Normally, we’re all afraid of vampires, but this vampire is so cute that he’s changed the way we look at them. Count von Count, also known as The Count, was introduced to the series in season 4. Unlike other vampires, he doesn’t want blood; he just wants to count things constantly. Counting has become an obsession for him. While Sesame Street never officially confirms that he’s a vampire, it’s clear that he has some vampiric traits. One key difference is that he loves sunlight — after all, no one would want The Count to evaporate!

9. Abby Cadabby:

Abby Cadabby was added to the series in the 37th season. Her name comes from the word «abracadabra» used to perform magic. She gained popularity with the shows «Abby’s Flying Fairy School» and «Abby’s Amazing Adventures». Sometimes his spells caused problems and he struggled to restore everything. Some fans say that Abby is Elmo’s girlfriend. Abracadabra, Hocus Pocus, Zippity-zap!

8. Grover:

Another classic character of the street and has been on the scene since 1970. Grover has a versatile personality: Waiter Grover, Super Grover, Global Grover, Marshal Grover… Grover was very close friends with Kermit when he was cast. The main reasons kids love him are because of his amazing imagination and always helping someone.

7. Bert:

One of the most serious characters in the series. Ernie is his best friend. Bert has a very serious personality. Ernie, on the other hand, is the opposite of him, he is playful and always wants to have fun. The character clash between these two characters enables the development of funny events. His favorite motto is: Life is hard with Ernie, but life is harder without him.

6. Ernie:

One of the most entertaining and humorous characters of the series. Ernie is Bert’s best friend and also his roommate. When Bert is busy with something, Ernie always tries to seduce him. When Bert wants to sleep, he doesn’t let him sleep, but then Ernie sleeps. You know, sometimes we like to gently tease a dear friend. That’s the instinct in Ernie’s behavior. Ernie also likes Rubber Duckie and sings songs for him.

5. Oscar the Grouch:

The right word to describe him would be extraordinary. Oscar the Grouch lives in a trash can and never complains about it: because he loves trash. As you can see from his name, he has a grumpy personality. He and the grouch named Grundgetta became engaged but stopped planning to get married because they were afraid of being happy. Oscar also states that he doesn’t like Telly and Elmo. He’s like a grumpy old man and it’s impossible to please him!

4. Big Bird:

Big Bird is a big yellow bird. He has been in the series since the first episode. He is usually a muppet prone to misunderstandings. However, he does not complain about this situation. Because he accepts himself as he is and is at peace with himself. Definitely a good role model for kids! Its creator, Jim Henson, died in 1990.

3. Cookie Monster:

Cookie Monster is the always-hungry character of the street. He loves cookies, but not just any cookies. He has been known to eat letters, numbers, and even once tried to eat a rock. He makes a lot of noise while eating. Early in the series, his name was Alistair Cookie. Cookie Monster is one of Sesame Street’s most popular characters. However, it would be better if he had a slightly healthier diet.

2. Kermit the Frog:

Kermit the Frog is one of the old muppet characters of the series. He was the host of Sesame Street News Flash. And he sang the classic song «Being Green». Sesame Street didn’t own all the rights to it. Therefore, he did not become a permanent muppet on the street. Still, it was necessary to add the old friend to this list.

1. elmo:

He is number one on the list. Speaking in third person, Elmo is the most popular muppet character in the series. Kevin Clash contributed a lot in making him loved so much. After Clash, Ryan Dillon picked up where he left off. Elmo even has a show called «The Not-Too-Late Show with Elmo» that he currently hosts himself. «Elmo’s World» series is still an important segment for children with its old and new versions. He also starred in «Elmo the Musical». It’s hard to fit its popularity into the list here. After all, you all know him well.

Sesame Street Human Characters — Sesame Street Cast

We’ve compiled a list of the human characters of Sesame Street. Some characters on the list are not currently in active casting; however, we included them because they deserve respect. The list is in random order.

18. Mando:

Played by Ismael Crúz Cordova, Mando appeared in seasons 44 and 45. It was first added to the cast in episode 4404. This episode was about the Latin Festival and the Puerto Rico booth hosted by Mando.

17. Mr. Hooper (1969 — 1983)

Several generations grew up with him. He owned the candy store Hooper’s Store. His real name was Will Lee. Will Lee died in 1982. He said goodbye to the street in the 1839th episode. In order for Mr. Hooper’s death to not traumatize the children, it was explained in the following episodes that death and mourning are a natural flow of life. We miss you Mr. Hooper.

16. Gabi — Gabriela Rodriguez (1989 — 2013)

Her real name is Desiree Casado. Gabi is the daughter of Maria and Luis. She was born on Sesame Street in season 20. She was not included in the cast of the series after the 43rd season.

15. Bob — Bob Johnson (1969 — 2017)

His real name is Bob McGrath. He is one of the human characters in the casting of the series for the longest time. Bob is a music teacher on Sesame Street. He acted as a teacher for the Muppet characters. He took part in the 50th anniversary celebration but isn’t in the current cast.

14. Chris — Chris Robinson (2007 — ?)

The character of Chris is played by Chris Knowings. Chris has been in the cast of the series starting from season 38 to the present day. Because of the Muppets’ pranks, he often tries to deal with problems that he has to solve. He is also Gordon and Susan’s nephew.

13. Leela (2008 — 2015)

Leela is a woman of Indian descent. She is portrayed by Nitya Vidyasagar. Leela works in a laundromat in the series. She was a very popular character in the seasons she was in the casting. She also took part in Sesame Street’s 50th anniversary celebration.

12. Susan — Susan Robinson (1969 — 2017)

Loretta Long played the character of Susan on Sesame Street. Susan was a prominent character on the show, who worked at the Fix-It Shop and often acted as a mediator among the Muppet characters. She was part of the cast from the show’s early years until the 45th season.

11. Nina (2016 — ?)

The character is played by Suki Lopez. Nina owns a bike store on Sesame Street. She is Spanish. She is bilingual and highly intelligent. She solves the problems faced by muppets with her intelligence. She is one of the few human characters in the current cast (as of 2022).

10. David (1971 — 1989)

David was a cheerful and singing character who worked at Hooper’s Store for a while and later took over the store after Mr. Hooper’s death. He and Maria were lovers for a while, but Maria eventually married Luis. David’s last name was never mentioned on the show. Northern Calloway, who played the character, died two years after leaving the cast. He will always be remembered with respect for his contributions to Sesame Street.

9. Luis — Luis Rodriguez (1971 — 2017)