WORD STRUCTURE IN MODERN ENGLISH

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of morphemes. Allomorphs.

II. Structural types of words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of stems. Derivational types of words.

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of Morphemes. Allomorphs.

There are two levels of approach to the study of word- structure: the level of morphemic analysis and the level of derivational or word-formation analysis.

Word is the principal and basic unit of the language system, the largest on the morphologic and the smallest on the syntactic plane of linguistic analysis.

It has been universally acknowledged that a great many words have a composite nature and are made up of morphemes, the basic units on the morphemic level, which are defined as the smallest indivisible two-facet language units.

The term morpheme is derived from Greek morphe “form ”+ -eme. The Greek suffix –eme has been adopted by linguistic to denote the smallest unit or the minimum distinctive feature.

The morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of form. A form in these cases a recurring discrete unit of speech. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words, not independently, although a word may consist of single morpheme. Even a cursory examination of the morphemic structure of English words reveals that they are composed of morphemes of different types: root-morphemes and affixational morphemes. Words that consist of a root and an affix are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word building known as affixation (or derivation).

The root-morpheme is the lexical nucleus of the word; it has a very general and abstract lexical meaning common to a set of semantically related words constituting one word-cluster, e.g. (to) teach, teacher, teaching. Besides the lexical meaning root-morphemes possess all other types of meaning proper to morphemes except the part-of-speech meaning which is not found in roots.

Affixational morphemes include inflectional affixes or inflections and derivational affixes. Inflections carry only grammatical meaning and are thus relevant only for the formation of word-forms. Derivational affixes are relevant for building various types of words. They are lexically always dependent on the root which they modify. They possess the same types of meaning as found in roots, but unlike root-morphemes most of them have the part-of-speech meaning which makes them structurally the important part of the word as they condition the lexico-grammatical class the word belongs to. Due to this component of their meaning the derivational affixes are classified into affixes building different parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives or adverbs.

Roots and derivational affixes are generally easily distinguished and the difference between them is clearly felt as, e.g., in the words helpless, handy, blackness, Londoner, refill, etc.: the root-morphemes help-, hand-, black-, London-, fill-, are understood as the lexical centers of the words, and –less, -y, -ness, -er, re- are felt as morphemes dependent on these roots.

Distinction is also made of free and bound morphemes.

Free morphemes coincide with word-forms of independently functioning words. It is obvious that free morphemes can be found only among roots, so the morpheme boy- in the word boy is a free morpheme; in the word undesirable there is only one free morpheme desire-; the word pen-holder has two free morphemes pen- and hold-. It follows that bound morphemes are those that do not coincide with separate word- forms, consequently all derivational morphemes, such as –ness, -able, -er are bound. Root-morphemes may be both free and bound. The morphemes theor- in the words theory, theoretical, or horr- in the words horror, horrible, horrify; Angl- in Anglo-Saxon; Afr- in Afro-Asian are all bound roots as there are no identical word-forms.

It should also be noted that morphemes may have different phonemic shapes. In the word-cluster please , pleasing , pleasure , pleasant the phonemic shapes of the word stand in complementary distribution or in alternation with each other. All the representations of the given morpheme, that manifest alternation are called allomorphs/or morphemic variants/ of that morpheme.

The combining form allo- from Greek allos “other” is used in linguistic terminology to denote elements of a group whose members together consistute a structural unit of the language (allophones, allomorphs). Thus, for example, -ion/ -tion/ -sion/ -ation are the positional variants of the same suffix, they do not differ in meaning or function but show a slight difference in sound form depending on the final phoneme of the preceding stem. They are considered as variants of one and the same morpheme and called its allomorphs.

Allomorph is defined as a positional variant of a morpheme occurring in a specific environment and so characterized by complementary description.

Complementary distribution is said to take place, when two linguistic variants cannot appear in the same environment.

Different morphemes are characterized by contrastive distribution, i.e. if they occur in the same environment they signal different meanings. The suffixes –able and –ed, for instance, are different morphemes, not allomorphs, because adjectives in –able mean “ capable of beings”.

Allomorphs will also occur among prefixes. Their form then depends on the initials of the stem with which they will assimilate.

Two or more sound forms of a stem existing under conditions of complementary distribution may also be regarded as allomorphs, as, for instance, in long a: length n.

II. Structural types of words.

The morphological analysis of word- structure on the morphemic level aims at splitting the word into its constituent morphemes – the basic units at this level of analysis – and at determining their number and types. The four types (root words, derived words, compound, shortenings) represent the main structural types of Modern English words, and conversion, derivation and composition the most productive ways of word building.

According to the number of morphemes words can be classified into monomorphic and polymorphic. Monomorphic or root-words consist of only one root-morpheme, e.g. small, dog, make, give, etc. All polymorphic word fall into two subgroups: derived words and compound words – according to the number of root-morphemes they have. Derived words are composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational morphemes, e.g. acceptable, outdo, disagreeable, etc. Compound words are those which contain at least two root-morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant. There can be both root- and derivational morphemes in compounds as in pen-holder, light-mindedness, or only root-morphemes as in lamp-shade, eye-ball, etc.

These structural types are not of equal importance. The clue to the correct understanding of their comparative value lies in a careful consideration of: 1)the importance of each type in the existing wordstock, and 2) their frequency value in actual speech. Frequency is by far the most important factor. According to the available word counts made in different parts of speech, we find that derived words numerically constitute the largest class of words in the existing wordstock; derived nouns comprise approximately 67% of the total number, adjectives about 86%, whereas compound nouns make about 15% and adjectives about 4%. Root words come to 18% in nouns, i.e. a trifle more than the number of compound words; adjectives root words come to approximately 12%.

But we cannot fail to perceive that root-words occupy a predominant place. In English, according to the recent frequency counts, about 60% of the total number of nouns and 62% of the total number of adjectives in current use are root-words. Of the total number of adjectives and nouns, derived words comprise about 38% and 37% respectively while compound words comprise an insignificant 2% in nouns and 0.2% in adjectives. Thus it is the root-words that constitute the foundation and the backbone of the vocabulary and that are of paramount importance in speech. It should also be mentioned that root words are characterized by a high degree of collocability and a complex variety of meanings in contrast with words of other structural types whose semantic structures are much poorer. Root- words also serve as parent forms for all types of derived and compound words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

In most cases the morphemic structure of words is transparent enough and individual morphemes clearly stand out within the word. The segmentation of words is generally carried out according to the method of Immediate and Ultimate Constituents. This method is based on the binary principle, i.e. each stage of the procedure involves two components the word immediately breaks into. At each stage these two components are referred to as the Immediate Constituents. Each Immediate Constituent at the next stage of analysis is in turn broken into smaller meaningful elements. The analysis is completed when we arrive at constituents incapable of further division, i.e. morphemes. These are referred to Ultimate Constituents.

A synchronic morphological analysis is most effectively accomplished by the procedure known as the analysis into Immediate Constituents. ICs are the two meaningful parts forming a large linguistic unity.

The method is based on the fact that a word characterized by morphological divisibility is involved in certain structural correlations. To sum up: as we break the word we obtain at any level only ICs one of which is the stem of the given word. All the time the analysis is based on the patterns characteristic of the English vocabulary. As a pattern showing the interdependence of all the constituents segregated at various stages, we obtain the following formula:

un+ { [ ( gent- + -le ) + -man ] + -ly}

Breaking a word into its Immediate Constituents we observe in each cut the structural order of the constituents.

A diagram presenting the four cuts described looks as follows:

1. un- / gentlemanly

2. un- / gentleman / — ly

3. un- / gentle / — man / — ly

4. un- / gentl / — e / — man / — ly

A similar analysis on the word-formation level showing not only the morphemic constituents of the word but also the structural pattern on which it is built.

The analysis of word-structure at the morphemic level must proceed to the stage of Ultimate Constituents. For example, the noun friendliness is first segmented into the ICs: [frendlı-] recurring in the adjectives friendly-looking and friendly and [-nıs] found in a countless number of nouns, such as unhappiness, blackness, sameness, etc. the IC [-nıs] is at the same time an UC of the word, as it cannot be broken into any smaller elements possessing both sound-form and meaning. Any further division of –ness would give individual speech-sounds which denote nothing by themselves. The IC [frendlı-] is next broken into the ICs [-lı] and [frend-] which are both UCs of the word.

Morphemic analysis under the method of Ultimate Constituents may be carried out on the basis of two principles: the so-called root-principle and affix principle.

According to the affix principle the splitting of the word into its constituent morphemes is based on the identification of the affix within a set of words, e.g. the identification of the suffix –er leads to the segmentation of words singer, teacher, swimmer into the derivational morpheme – er and the roots teach- , sing-, drive-.

According to the root-principle, the segmentation of the word is based on the identification of the root-morpheme in a word-cluster, for example the identification of the root-morpheme agree- in the words agreeable, agreement, disagree.

As a rule, the application of these principles is sufficient for the morphemic segmentation of words.

However, the morphemic structure of words in a number of cases defies such analysis, as it is not always so transparent and simple as in the cases mentioned above. Sometimes not only the segmentation of words into morphemes, but the recognition of certain sound-clusters as morphemes become doubtful which naturally affects the classification of words. In words like retain, detain, contain or receive, deceive, conceive, perceive the sound-clusters [rı-], [dı-] seem to be singled quite easily, on the other hand, they undoubtedly have nothing in common with the phonetically identical prefixes re-, de- as found in words re-write, re-organize, de-organize, de-code. Moreover, neither the sound-cluster [rı-] or [dı-], nor the [-teın] or [-sı:v] possess any lexical or functional meaning of their own. Yet, these sound-clusters are felt as having a certain meaning because [rı-] distinguishes retain from detain and [-teın] distinguishes retain from receive.

It follows that all these sound-clusters have a differential and a certain distributional meaning as their order arrangement point to the affixal status of re-, de-, con-, per- and makes one understand —tain and –ceive as roots. The differential and distributional meanings seem to give sufficient ground to recognize these sound-clusters as morphemes, but as they lack lexical meaning of their own, they are set apart from all other types of morphemes and are known in linguistic literature as pseudo- morphemes. Pseudo- morphemes of the same kind are also encountered in words like rusty-fusty.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of Stems. Derivational types of word.

The morphemic analysis of words only defines the constituent morphemes, determining their types and their meaning but does not reveal the hierarchy of the morphemes comprising the word. Words are no mere sum totals of morpheme, the latter reveal a definite, sometimes very complex interrelation. Morphemes are arranged according to certain rules, the arrangement differing in various types of words and particular groups within the same types. The pattern of morpheme arrangement underlies the classification of words into different types and enables one to understand how new words appear in the language. These relations within the word and the interrelations between different types and classes of words are known as derivative or word- formation relations.

The analysis of derivative relations aims at establishing a correlation between different types and the structural patterns words are built on. The basic unit at the derivational level is the stem.

The stem is defined as that part of the word which remains unchanged throughout its paradigm, thus the stem which appears in the paradigm (to) ask ( ), asks, asked, asking is ask-; thestem of the word singer ( ), singer’s, singers, singers’ is singer-. It is the stem of the word that takes the inflections which shape the word grammatically as one or another part of speech.

The structure of stems should be described in terms of IC’s analysis, which at this level aims at establishing the patterns of typical derivative relations within the stem and the derivative correlation between stems of different types.

There are three types of stems: simple, derived and compound.

Simple stems are semantically non-motivated and do not constitute a pattern on analogy with which new stems may be modeled. Simple stems are generally monomorphic and phonetically identical with the root morpheme. The derivational structure of stems does not always coincide with the result of morphemic analysis. Comparison proves that not all morphemes relevant at the morphemic level are relevant at the derivational level of analysis. It follows that bound morphemes and all types of pseudo- morphemes are irrelevant to the derivational structure of stems as they do not meet requirements of double opposition and derivative interrelations. So the stem of such words as retain, receive, horrible, pocket, motion, etc. should be regarded as simple, non- motivated stems.

Derived stems are built on stems of various structures though which they are motivated, i.e. derived stems are understood on the basis of the derivative relations between their IC’s and the correlated stems. The derived stems are mostly polymorphic in which case the segmentation results only in one IC that is itself a stem, the other IC being necessarily a derivational affix.

Derived stems are not necessarily polymorphic.

Compound stems are made up of two IC’s, both of which are themselves stems, for example match-box, driving-suit, pen-holder, etc. It is built by joining of two stems, one of which is simple, the other derived.

In more complex cases the result of the analysis at the two levels sometimes seems even to contracted one another.

The derivational types of words are classified according to the structure of their stems into simple, derived and compound words.

Derived words are those composed of one root- morpheme and one or more derivational morpheme.

Compound words contain at least two root- morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant.

Derivational compound is a word formed by a simultaneous process of composition and derivational.

Compound words proper are formed by joining together stems of word already available in the language.

Теги:

Word structure in modern english

Реферат

Английский

Просмотров: 27684

Найти в Wikkipedia статьи с фразой: Word structure in modern english

1. What is Sentence Structure?

A sentence’s “structure” is the way its words are arranged.

In English, we have four main sentence structures: the simple sentence, the compound sentence, the complex sentence, and the compound-complex sentence. Each uses a specific combination of independent and dependent clauses to help make sure that our sentences are strong, informational, and most importantly, that they make sense!

2. Examples of Sentence Structures

In the examples, independent clauses are green, dependent clauses are purple, and conjunctions are orange. Here are examples of each type of sentence:

- The dog ran. Simple Sentence

- The dog ran and he ate popcorn. Compound sentence

- After the dog ran, he ate popcorn. Complex sentence

- After the dog ran, he ate popcorn and he drank a big soda. Compound-complex sentence

3. Parts of Sentence Structures

All forms of sentence structures have clauses (independent, dependent, or both), and some also have conjunctions to help join two or more clauses or whole sentences.

a. Independent Clause

Independent clauses are key parts of every sentence structure. An independent clause has a subject and a predicate and makes sense on its own as a complete sentence. Here are a few:

- The dog ate brownies.

- The dog jumped high.

- She ate waffles.

- He went to the library.

So, you can see that all of the clauses above are working sentences. What’s more, all sentences have an independent clause!

b. Dependent (Subordinate) Clause

A dependent clause is a major part of three of the four sentence structures (compound, complex, and compound-complex). It has a subject and a predicate; BUT, it can’t be a sentence. It provides extra details about the independent clause, and it doesn’t make sense on its own, like these:

- After he went to the party

- Though he ate hotdogs

- While he was at the dance

- If the dog eats chocolate

Each of the bullets above leaves an unanswered question. By itself, a dependent clause is just a fragment sentence (an incomplete sentence). So, it needs to be combined with an independent clause to be a sentence.

c. Conjunction

A conjunction is a word in a sentence that connects other words, phrases and clauses. Conjunctions are a big part of compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences. The most common conjunction that you know is “and.” Others are for, but, or, yet, and so. Conjunctions are important because they let us combine information, but still keep ideas separate so that they are easy to understand.

Here are two sentences, with and without conjunctions:

Incorrect: The girl ran to the ice cream truck then she ate ice cream.

Correct: The girl ran to the ice cream truck, and then she ate ice cream.

So, you can see that we need a conjunction for the sentence to be clear!

It is important to know that the word “then” is NOT a conjunction—it’s an adverb.

4. Types of Sentence Structures

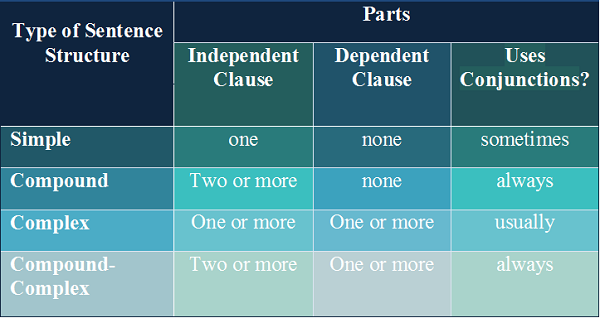

As mentioned, there are four main types of sentence structures: simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex. To begin, here is a simple chart that outlines the patterns of each type.

a. Simple sentence

A simple sentence has only one subject and one predicate—one independent clause. In fact, an independent clause itself is a simple sentence. Here are some examples:

- She jumped.

- The cheetah ran.

- He ran to the gas station.

- He ate dinner.

Simple sentences don’t have many details and they don’t really combine multiple ideas—they are simple!

b. Compound sentence

A compound sentence has at least two independent clauses. It uses a conjunction like “and” to connect the ideas. Here are some examples:

- The dog ate pizza but the cat drank apple juice.

- The dog ate pizza but the cat drank apple juice and the fish had eggs.

As you can see, a compound sentence allows us to share a lot of information by combining two or more complete thoughts into one sentence.

c. Complex sentence

A complex sentence has one independent clause and one or more dependent clauses. It sometimes uses conjunctions and other words to combine all of the clauses together.

- When he was on the airplane, the man bought cookies.

- When he was on the airplane, the man bought cookies, but not brownies.

A great way to make a sentence more detailed is by adding dependent clauses (which couldn’t be sentences on their own). So, complex sentences let us add information to simple sentences.

d. Compound-complex sentence

A compound-complex sentence has two or more independent clauses and at least one dependent clause—so, it uses conjunction(s) to combine two complete sentences and at least one incomplete sentence. Here is an example:

The girl smelled cookies, which were baking at home, so, she ran all the way there.

The result of combining the three clauses and the conjunction is a compound-complex sentence that is both informational and easy to understand. The independent clauses give the main information, and the dependent clause(s) give the details.

5. How to Avoid Mistakes

When it comes to making sure your sentence is clear and complete, having the right sentence structure is very important. A couple of common mistakes can happen when you forget how to use clauses or conjunctions in the right way, like run-on sentences and fragment sentences.

a. Run-on sentences

In simple terms, a run-on sentence is a sentence that is too long. For instance, if a writer forgets to use conjunctions, a sentence seems like it “runs on” for too long. For example:

The fox really liked pancakes, he ate them every day for breakfast, he couldn’t eat them without syrup and butter.

But, with the right conjunctions, this can be a normal compound sentence:

The fox really liked pancakes, so, he ate them every day for breakfast; but, he couldn’t eat them without syrup and butter.

As you can see, the new sentence is much easier to read and makes more sense.

b. Fragment (incomplete) sentences

A “fragment” is a small piece of something. So, a fragment sentence is just a piece of a sentence: it is missing a subject, a predicate, or an independent clause. It’s simply an incomplete sentence. Fragment sentences can happen when you forget an independent clause.

For instance, by itself, a dependent clause is just a fragment. Let’s use a couple of the dependent clauses from above:

- While he was at the dance What happened?

- If he eats chocolate Then what?

As you can see, each leaves an unanswered question. So, let’s complete them:

- While he was at the dance, the dog drank fruit punch.

- The dog will get a stomachache if he eats chocolate.

Here, we completed the fragment sentences by adding independent clauses (underlined), which made them into complex sentences.

Test your Knowledge

1.

Which type of sentence combines two independent clauses?

a.Compound sentence

b.Simple sentence

c.None of the above

d.All of the above

2.

Which type of sentence can have two or more independent and dependent clauses?

a.Simple sentence

b.Compound-complex sentence

c.Compound sentence

d.None of the above

3.

Add a conjunction or conjunctions to make the following sentence clearer: The dog and the cat loved to eat ice cream, they liked going fishing, searching for clovers.

a.The dog and the cat loved to eat ice cream, they liked going fishing, and searching for clovers.

b.The dog and the cat loved to eat ice cream, so they liked going fishing, searching for clovers.

c.The dog and the cat loved to eat ice cream, and they liked going fishing, searching for clovers.

d.The dog and the cat loved to eat popcorn, and they liked going fishing and searching for clovers.

4.

Add an independent clause to complete the following sentence: If the rabbit goes to the dentist,

a.and

b.and gets a sticker.

c.he will get his teeth cleaned.

d.and his teeth cleaned.

Welcome to the ELB Guide to English Word Order and Sentence Structure. This article provides a complete introduction to sentence structure, parts of speech and different sentence types, adapted from the bestselling grammar guide, Word Order in English Sentences. I’ve prepared this in conjunction with a short 3-video course, currently in editing, to help share the lessons of the book to a wider audience.

You can use the headings below to quickly navigate the topics:

- Different Ways to Analyse English Structure

- Subject-Verb-Object: Sentence Patterns

- Adding Additional Information: Objects, Prepositional Phrases and Time

- Alternative Sentence Patterns: Different Sentence Types

- Parts of Speech

- Nouns, Determiners and Adjectives

- Pronouns

- Verbs

- Phrasal Verbs

- Adverbs

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

- Clauses, Simple, Compound and Complex Sentences

- Simple Sentences

- Compound Sentences

- Complex Sentences

Different Ways to Analyse English Structure

There are lots of ways to break down sentences, for different purposes. This article covers the systems I’ve found help my students understand and form accurate sentences, but note these are not the only ways to explore English grammar.

I take three approaches to introducing English grammar:

- Studying overall patterns, grouping sentence components by their broad function (subject, verb, object, etc.)

- Studying different word types (the parts of speech), how their phrases are formed and their places in sentences

- Studying groupings of phrases and clauses, and how they connect in simple, compound and complex sentences

Subject-Verb-Object: Sentence Patterns

English belongs to a group of just under half the world’s languages which follows a SUBJECT – VERB – OBJECT order. This is the starting point for all our basic clauses (groups of words that form a complete grammatical idea). A standard declarative clause should include, in this order:

- Subject – who or what is doing the action (or has a condition demonstrated, for state verbs), e.g. a man, the church, two beagles

- Verb – what is done or what condition is discussed, e.g. to do, to talk, to be, to feel

- Additional information – everything else!

In the correct order, a subject and verb can communicate ideas with immediate sense with as little as two or three words.

- Gemma studies.

- It is hot.

Why does this order matter? We know what the grammatical units are because of their position in the sentence. We give words their position based on the function we want them to convey. If we change the order, we change the functioning of the sentence.

- Studies Gemma

- Hot is it

With the verb first, these ideas don’t make immediate sense and, depending on the verbs, may suggest to English speakers a subject is missing or a question is being formed with missing components.

- The alien studies Gemma. (uh oh!)

- Hot, is it? (a tag question)

If we don’t take those extra steps to complete the idea, though, the reversed order doesn’t work. With “studies Gemma”, we couldn’t easily say if we’re missing a subject, if studies is a verb or noun, or if it’s merely the wrong order.

The point being: using expected patterns immediately communicates what we want to say, without confusion.

Adding Additional Information: Objects, Prepositional Phrases and Time

Understanding this basic pattern is useful for when we start breaking down more complicated sentences; you might have longer phrases in place of the subject or verb, but they should still use this order.

| Subject | Verb |

| Gemma | studies. |

| A group of happy people | have been quickly walking. |

After subjects and verbs, we can follow with different information. The other key components of sentence patterns are:

- Direct Object: directly affected by the verb (comes after verb)

- Indirect Objects: indirectly affected by the verb (typically comes between the verb and a direct object)

- Prepositional phrases: noun phrases providing extra information connected by prepositions, usually following any objects

- Time: describing when, usually coming last

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object | Preposition Phrase | Time |

| Gemma | studied | English | in the library | last week. | |

| Harold | gave | his friend | a new book | for her birthday | yesterday. |

The individual grammatical components can get more complicated, but that basic pattern stays the same.

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object | Preposition Phrase | Time |

| Our favourite student Gemma | has been studying | the structure of English | in the massive new library | for what feels like eons. | |

| Harold the butcher’s son | will have given | the daughter of the clockmaker | an expensive new book | for her coming-of-age festival | by this time next week. |

The phrases making up each grammatical unit follow their own, more specific rules for ordering words (covered below), but overall continue to fit into this same basic order of components:

Subject – Verb – Indirect Object – Direct Object – Prepositional Phrase – Time

Alternative Sentence Patterns: Different Sentence Types

Subject-Verb-Object is a starting point that covers positive, declarative sentences. These are the most common clauses in English, used to describe factual events/conditions. The type of verb can also make a difference to these patterns, as we have action/doing verbs (for activities/events) and linking/being verbs (for conditions/states/feelings).

Here’s the basic patterns we’ve already looked at:

- Subject + Action Verb – Gemma studies.

- Subject + Action Verb + Object – Gemma studies English.

- Subject + Action Verb + Indirect Object + Direct Object – Gemma gave Paul a book.

We might also complete a sentence with an adverb, instead of an object:

- Subject + Action Verb + Adverb – Gemma studies hard.

When we use linking verbs for states, senses, conditions, and other occurrences, the verb is followed by noun or adjective phrases which define the subject.

- Subject + Linking Verb + Noun Phrase – Gemma is a student.

- Subject + Linking Verb + Adjective Phrase – Gemma is very wise.

These patterns all form positive, declarative sentences. Another pattern to note is Questions, or interrogative sentences, where the first verb comes before the subject. This is done by adding an auxiliary verb (do/did) for the past simple and present simple, or moving the auxiliary verb forward if we already have one (to be for continuous tense, or to have for perfect tenses, or the modal verbs):

- Gemma studies English. –> Does Gemma study English?

- Gemma is very wise. –> Is Gemma very wise?

For more information on questions, see the section on verbs.

Finally, we can also form imperative sentences, when giving commands, which do not need a subject.

- Study English!

(Note it is also possible to form exclamatory sentences, which express heightened emotion, but these depend more on context and punctuation than grammatical components.)

Parts of Speech

General patterns offer overall structures for English sentences, while the broad grammatical units are formed of individual words and phrases. In English, we define different word types as parts of speech. Exactly how many we have depends on how people break them down. Here, we’ll look at nine, each of which is explained below. Either keep reading or click on the word types to go to the sections about their word order rules.

- Nouns – naming words that define someone or something, e.g. car, woman, cat

- Pronouns – words we use in place of nouns, e.g. he, she, it

- Verbs – doing or being words, describing an action, state or experience e.g. run, talk, be

- Adjectives – words that describe nouns or pronouns, e.g. cheerful, smelly, loud

- Adverbs – words that describe verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, sentences themselves – anything other nouns and pronouns, basically, e.g. quickly, curiously, weirdly

- Determiners – words that tell us about a noun’s quantity or if it’s specific, e.g. a, the, many

- Prepositions – words that show noun or noun phrase positions and relationships, e.g. above, behind, in, on

- Conjunctions – words that connect words, phrases or clauses e.g. and, but

- Interjections – words that express a single emotion, e.g. Hey! Ah! Oof!

For more articles and exercises on all of these, be sure to also check out ELB’s archive covering parts of speech.

Noun Phrases, Determiners and Adjectives

Subjects and objects are likely to be nouns or noun phrases, describing things. So sentences usually to start with a noun phrase followed by a verb.

- Nina ate.

However, a noun phrase may be formed of more than word.

We define nouns with determiners. These always come first in a noun phrase. They can be articles (a/an/the – telling us if the noun is specific or not), or can refer to quantities (e.g. some, much, many):

- a dog (one of many)

- the dog in the park

- many dogs

After determiners, we use adjectives to add description to the noun:

- The fluffy dog.

You can have multiple adjectives in a phrase, with orders of their own. You can check out my other article for a full analysis of adjective word order, considering type, material, size and other qualities – but a starting rule is that less definite adjectives go first – more specific qualities go last. Lead with things that are more opinion-based, finish with factual elements:

- It is a beautiful wooden chair. (opinion before fact.)

We can also form compound nouns, where more than one noun is used, e.g. “cat food”, “exam paper”. The earlier nouns describe the final noun: “cat food” is a type of food, for cats; an “exam paper” is a specific paper. With compound nouns you have a core noun (the last noun), what the thing is, and any nouns before it describe what type. So – description first, the actual thing last.

Finally, noun phrases may also include conjunctions joining lists of adjectives or nouns. These usually come between the last two items in a list, either between two nouns or noun phrases, or between the last two adjectives in a list:

- Julia and Lenny laughed all day.

- a long, quick and dangerous snake

Pronouns

We use pronouns in the place of nouns or noun phrases. For the most part, these fit into sentences the same way as nouns, in subject or object positions, but don’t form phrases, as they replace a whole noun phrase – so don’t use describing words or determiners with pronouns.

Pronouns suggest we already know what is being discussed. Their positions are the same as nouns, except with phrasal verbs, where pronouns often have fixed positions, between a verb and a particle (see below).

Verbs

Verb phrases should directly follow the subject, so in terms of parts of speech a verb should follow a noun phrase, without connecting words.

As with nouns and noun phrases, multiple words may make up the verb component. Verb phrases depend on your tenses, which follow particular forms – e.g. simple, continuous, perfect and perfect continuous. The specifics of verb phrases are covered elsewhere, for example the full verb forms for the tenses are available in The English Tenses Practical Grammar Guide. But in terms of structure, with standard, declarative clauses the ordering of verb phrases should not change from their typical tense forms. Other parts of speech do not interrupt verb phrases, except for adverbs.

The times that verb phrases do change their structure are for Questions and Negatives.

With Yes/No Questions, the first verb of a verb phrase comes before the subject.

- Neil is running. –> Is Neil running?

This requires an auxiliary verb – a verb that creates a grammatical function. Many tenses already have an auxiliary verb – to be in continuous tenses (“is running”), or to have in perfect tenses (have done). For these, to make a question we move that auxiliary in front of the subject. With the past and present simple tenses, for questions, we add do or did, and put that before the subject.

- Neil ran. –> Did Neil run?

We can also have questions that use question words, asking for information (who, what, when, where, why, which, how), which can include noun phrases. For these, the question word and any noun phrases it includes comes before the verb.

- Where did Neil Run?

- At what time of day did Neil Run?

To form negative statements, we add not after the first verb, if there is already an auxiliary, or if there is not auxiliary we add do not or did not first.

- Neil is running. –> Neil is not

- Neil ran. Neil did not

The not stays behind the subject with negative questions, unless we use contractions, where not is combined with the verb and shares its position.

- Is Neil not running?

- Did Neil not run?

- Didn’t Neil run?

Phrasal Verbs

Phrasal verbs are multi-word verbs, often with very specific meanings. They include at least a verb and a particle, which usually looks like a preposition but functions as part of the verb, e.g. “turn up“, “keep on“, “pass up“.

You can keep phrasal verb phrases all together, as with other verb phrases, but they are more flexible, as you can also move the particle after an object.

- Turn up the radio. / Turn the radio up.

This doesn’t affect the meaning, and there’s no real right or wrong here – except with pronouns. When using pronouns, the particle mostly comes after the object:

- Turn it up. NOT Turn up it.

For more on phrasal verbs, check out the ELB phrasal verbs master list.

Adverbs

Adverbs and adverbial phrases are really tricky in English word order because they can describe anything other than nouns. Their positions can be flexible and they appear in unexpected places. You might find them in the middle of verb phrases – or almost anywhere else in a sentence.

There are many different types of adverbs, with different purposes, which are usually broken down into degree, manner, frequency, place and time (and sometimes a few others). They may be single words or phrases. Adverbs and adverb phrases can be found either at the start of a clause, the end of a clause, or in a middle position, either directly before or after the word they modify.

- Graciously, Claire accepted the award for best student. (beginning position)

- Claire graciously accepted the award for best student. (middle position)

- Claire accepted the award for best student graciously. (end position)

Not all adverbs can go in all positions. This depends on which type they are, or specific adverb rules. One general tip, however, is that time, as with the general sentence patterns, should usually come last in a clause, or at the very front if moved for emphasis.

With verb phrases, adverbs often either follow the whole phrase or come before or after the first verb in a phrase (there are regional variations here).

For multiple adverbs, there can be a hierarchy in a similar way to adjectives, but you shouldn’t often use many adverbs together.

The largest section of the Word Order book discusses adverbs, with exercises.

Prepositions

Prepositions are words that, generally, demonstrate relationships between noun phrases (e.g. by, on, above). They mostly come before a noun phrase, hence the name pre-position, and tend to stick with the noun phrase they describe, so move with the phrase.

- They found him [in the cupboard].

- [In the cupboard,] they found him.

In standard sentence structure, prepositional phrases often follow verbs or other noun phrases, but they may also be used for defining information within a noun phrases itself:

- [The dog in sunglasses] is drinking water.

Conjunctions

Conjunctions connect lists in noun phrases (see nouns) or connect clauses, meaning they are found between complete clauses. They can also come at the start of a sentence that begins with a subordinate clause, when clauses are rearranged (see below), but that’s beyond the standard word order we’re discussing here. There’s more information about this in the article on different sentence types.

As conjunctions connect clauses, they come outside our sentence and word type patterns – if we have two clauses following subject-verb-object, the conjunction comes between them:

|

Subject |

Verb |

Object |

Conjunction |

Subject |

Verb |

Object |

|

He |

washed |

the car |

while |

she |

ate |

a pie. |

Interjections

These are words used to show an emotion, usually something surprising or alarming, often as an interruption – so they can come anywhere! They don’t normally connect to other words, as they are either used to get attention or to cut off another thought.

- Hey! Do you want to go swimming?

- OH NO! I forgot my homework.

Clauses and Simple, Compound and Complex Sentences

While a phrase is any group of words that forms a single grammatical unit, a clause is when a group of words form a complete grammatical idea. This is possible when we follow the patterns at the start of this article, for example when we combine a subject and verb (or noun phrase and verb phrase).

A single clause can follow any of the patterns we’ve already discussed, using varieties of the word types covered; it can be as simple a two-word subject-verb combo, or it may include as many elements as you can think of:

- Eric sat.

- The boy spilt blue paint on Harriet in the classroom this morning.

As long as we have one main verb and one main subject, these are still single clauses. Complete with punctuation, such as a capital letter and full stop, and we have a complete sentence, a simple sentence. When we combine two or more clauses, we form compound or complex sentences, depending on the clauses relationships to each other. Each type is discussed below.

Simple Sentences

A sentence with one independent clause is what we call a simple sentence; it presents a single grammatically complete action, event or idea. But as we’ve seen, just because the sentence structure is called simple it does not mean the tenses, subjects or additional information are simple. It’s the presence of one main verb (or verb phrase) that keeps it simple.

Our additional information can include any number of objects, prepositional phrases and adverbials; and that subject and verb can be made up of long noun and verb phrases.

Compound Sentences

We use conjunctions to bring two or more clauses together to create a compound sentence. The clauses use the same basic order rules; just treat the conjunction as a new starting point. So after one block of subject-verb-object, we have a conjunction, then the next clause will use the same pattern, subject-verb-object.

- [Gemma worked hard] and [Paul copied her].

See conjunctions for another example.

A series of independent clauses can be put together this way, following the expected patterns, joined by conjunctions.

Compound sentences use co-ordinating conjunctions, such as and, but, for, yet, so, nor, and or, and do not connect the clauses in a dependent way. That means each clause makes sense on its own – if we removed the conjunction and created separate sentences, the overall meaning would remain the same.

With more than two clauses, you do not have to include conjunctions between each one, e.g. in a sequence of events:

- I walked into town, I visited the book shop and I bought a new textbook.

And when you have the same subject in multiple clauses, you don’t necessarily need to repeat it. This is worth noting, because you might see clauses with no immediate subject:

- [I walked into town], [visited the book shop] and [bought a new textbook].

Here, with “visited the book shop” and “bought a new textbook” we understand that the same subject applies, “I”. Similarly, when verb tenses are repeated, using the same auxiliary verb, you don’t have to repeat the auxiliary for every clause.

What about ordering the clauses? Independent clauses in compound sentences are often ordered according to time, when showing a listed sequence of actions (as in the example above), or they may be ordered to show cause and effect. When the timing is not important and we’re not showing cause and effect, the clauses of compound sentences can be moved around the conjunction flexibly. (Note: any shared elements such as the subject or auxiliary stay at the front.)

- Billy [owned a motorbike] and [liked to cook pasta].

- Billy [liked to cook pasta] and [owned a motorbike].

Complex Sentences

As well as independent clauses, we can have dependent clauses, which do not make complete sense on their own, and should be connected to an independent clause. While independent clauses can be formed of two words, the subject and verb, dependent clauses have an extra word that makes them incomplete – either a subordinating conjunction (e.g. because, when, since, if, after and although), or a relative pronoun, (e.g. that, who and which).

- Jim slept.

- While Jim slept,

Subordinating conjunctions and relative pronouns create, respectively, a subordinate clause or a relative clause, and both indicate the clause is dependent on more information to form a complete grammatical idea, to be provided by an independent clause:

- While Jim slept, the clowns surrounded his house.

In terms of structure, the order of dependent clauses doesn’t change from the patterns discussed before – the word that comes at the front makes all the difference. We typically connect independent clauses and dependent clauses in a similar way to compound sentences, with one full clause following another, though we can reverse the order for emphasis, or to present a more logical order.

- Although she liked the movie, she was frustrated by the journey home.

(Note: when a dependent clause is placed at the beginning of a sentence, we use a comma, instead of another conjunction, to connect it to the next clause.)

Relative clauses, those using relative pronouns (such as who, that or which), can also come in different positions, as they often add defining information to a noun or take the place of a noun phrase itself.

- The woman who stole all the cheese was never seen again.

- Whoever stole all the cheese is going to be caught one day.

In this example, the relative clause could be treated, in terms of position, in the same way as a noun phrase, taking the place of an object or the subject:

- We will catch whoever stole the cheese.

For more information on this, check out the ELB guide to simple, compound and complex sentences.

That’s the end of my introduction to sentence structure and word order, but as noted throughout this article there are plenty more articles on this website for further information. And if you want a full discussion of these topics be sure to check out the bestselling guide, Word Order in English Sentences, available in eBook on this site and from all major retailers in paperback format.

Get the Complete Word Order Guide

This article is expanded upon in the bestselling grammar guide, Word Order in English Sentences, available in eBook and paperback.

If you found this useful, check out the complete book for more.

English sentence structure refers to the different ways in which you can use word order and parts of speech to form sentences. Learning how to vary sentence structure in your writing and speech can also get you one step closer to English fluency! In today’s guide, we will look at sentence structure rules in English, the basic types of sentence structure, and how to vary your sentences in both English writing and speech. So, let’s get started!

What Is Sentence Structure in English?

If you’ve spent any amount of time studying English, you know that sentences can get pretty long and complicated. However, at their core, most English sentences adhere to specific sentence structure rules. More specifically, the basic sentence structure in English depends on two important elements: the subject and the predicate. Additionally, sentences can contain one or more objects, indirect objects, and complements.

- Subject – The subject of a sentence is the person, place, thing, or idea that is performing an action.

- The man laughed.

- Predicate – The predicate is the part of a sentence that contains the main verb and any modifying words or clauses.

- The man laughed.

- Object – The object is the person, place, thing, or idea that receives the action in a sentence.

- The man bought a newspaper.

- Indirect Object – The indirect object of a sentence signifies to whom or for whom an action is done.

- The man bought a newspaper for me.

- Complement – The complement refers back to the subject of a sentence. In order for a sentence to contain a complement, there must also be a linking verb.

- The man is a good person.

What are Clauses in English?

To fully understand sentence structure in English, you must also understand the role of clauses. There are two primary types of clauses in English: independent clauses (main clauses) and dependent clauses (subordinating clauses). An independent clause must contain a subject and a verb (predicate). Therefore, an independent clause can work independently from any other clause. Multiple independent clauses can even be linked together using a coordinating conjunction or a semicolon. For example:

- The woman worked.

- The woman liked her job, but she really wanted a promotion.

- Even though the job was great, the woman decided to quit.

- The woman quit her job and she never looked back.

- The woman quit her job; it was the best decision she ever made.

Alternatively, a dependent clause cannot stand on its own. In other words, a dependent clause depends on the presence of an independent clause to form a complete sentence. A dependent clause always begins with a subordinating conjunction or a relative pronoun. For example:

- The boy walked to school because he missed the bus.

- Since he was late for school, the boy couldn’t use his favorite seat.

- The teacher scolded him when he arrived.

- After that day, the boy felt embarrassed, because he was known as the boy who was late for school.

4 Types of Sentences in English

Now that you know the basic terms for different parts of a sentence, it’s time to start making sentences! There are four basic types of sentences that you can create: simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex.

- Simple Sentence – A simple sentence has one subject and one predicate. In other words, it is made up of one independent clause.

- The girl borrowed a book.

- Compound Sentence – A compound sentence has at least two subjects and two verbs. This means that a compound sentence has two independent clauses joined by a comma and a coordinating conjunction.

- I really love this author, but I don’t have time to read her new book.

- Complex Sentence – A complex sentence has one independent clause and at least one dependent clause.

- We laughed while we walked to the library.

- Compound-Complex Sentence – A compound-complex sentence has at least two independent clauses and at least one dependent clause.

- Since I couldn’t find my car keys, my roommate drove me to work, and I was very grateful.

How to Form a Simple Sentence in English

Ok, so we’ve covered a lot of information so far. Now you know the basic parts of a sentence, the two main types of clauses that make up English sentences, and the different types of sentences you can make. So, now let’s practice making some simple sentences!

Fortunately, sentence structure exercises don’t have to be tedious. Let’s begin with some of the most basic sentence forms to help get you started!

Subject-Verb

| Independent Clause | |

| Subject | Predicate |

| Verb | |

| Isabella | walks. |

| The dog | plays. |

| We | laugh. |

Can you think of some other examples? Simply replace any of the words in the “subject” column with a noun, noun phrase, or pronoun. Then, replace the word in the “verb” column with a verb that agrees with the subject. It’s that easy! Now let’s start adding some new elements:

Subject–Verb–Object

| Independent Clause | ||

| Subject | Predicate | |

| Verb | Object | |

| He | sees | a tree. |

| My teacher | reads | the book. |

| I | carried | my bag. |

Subject–Verb–Adjective

| Independent Clause | ||

| Subject | Predicate | |

| Verb | Adjective | |

| The man | feels | happy. |

| The painting | looks | creepy. |

| She | is | kind. |

Subject–Verb–Adverb

| Independent Clause | ||

| Subject | Predicate | |

| Verb | Adverb | |

| They | walk | quickly. |

| He | stares | intensely. |

| We | performed | well. |

How to Vary Sentence Structure

Needless to say, only using simple sentences (like those outlined above) will let you express very basic thoughts, attitudes, and information — but not much else. Therefore, you will need to vary your speech and writing patterns to include compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences. However, when it actually comes to varying sentence structure, thinking about the kind of sentence you want to make doesn’t help very much. In fact, it can make the process a lot more confusing than it needs to be.

Instead, focus on sentence length. Whether you’re writing or speaking, try to sprinkle in a mixture of short, medium, and long sentences. This will guarantee that you use more than one type of sentence structure.

Another great way to vary sentence structure is to include transition words. These words help your sentences sound more varied and give multiple statements a sense of continuity. Here are a few common transition words that you can put in the beginning or middle of sentences:

- And

- But

- However

- Therefore

- Moreover

- Thus

- Although

- Because

- Yet

Finally, remember to use different verb tenses. This doesn’t mean that you should suddenly switch from past to present, and then back to the past again. This might sound confusing. Instead, you should try to mix in different English tenses that make sense in the context of your speech or writing.

Conclusion

When it comes to sentence structure in English, it can feel like there’s a lot of ground to cover. You need to have a basic understanding of English grammar, vocabulary, parts of speech, clauses, as well as the different parts of a sentence. Fortunately, with time and practice, all of these sentence structure rules and terms will start to come naturally to you!

We hope you found this guide on English sentence structure useful! If you’d like to hear a native English speaker using varied sentence structures, be sure to subscribe to the Magoosh Youtube channel today!

A sentence is a group of words that expresses a complete thought and contains a subject and a predicate. The most basic sentence structure consists of only one clause. However, many sentences have one main clause and one or more subordinate clauses.

The standard order of words in an English sentence is subject + verb + object. While this sounds simple, it may be difficult to identify the subject(s), verb(s), and object(s), depending on the structure and complexity of the sentence. There are four types of sentence structure: (1) simple, (2) compound, (3) complex, and (4) compound-complex.

Types of sentence structures

| Sentence structure type | Sentence parts | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Simple Sentence |

Independent clause |

I like animals. |

| Compound Sentence |

Independent clause + coordinating |

I like animals, |

| Complex Sentence |

Independent clause + |

I like animals |

|

Compound-Complex Sentence |

Independent clause + |

I like animals |

Sentence Structures in Academic Writing

Simple Sentence Structure

A simple sentence is the most basic sentence structure and consists of a single independent clause.

Types of clauses

An independent clause expresses a full thought. Only independent clauses can function as complete sentences.

- Example

- The proposed system has the advantage of a wide scope.

I went shopping last weekend.

The cat is sleeping by the window.

In contrast, a dependent clause does not express a full thought and cannot function as a complete sentence.

- Example

- which was developed over three months

even though I was tired

because the weather is sunny

A dependent clause starts with either a relative pronoun or subordinating conjunction.

Common subordinating conjunctions

because, since, once, although, if, until, unless, why, while, whether, than, that, in order to

Common relative pronouns

that, which, who, whom, whoever, whomever

Subject of a sentence

The subject is whatever is performing the action of the sentence. This is the first of the two basic components of a sentence.

- Example

- This study investigated the relationship between the personal traits and clinical parameters.

- Example

- Dolly made a cake for the party.

Predicate of a sentence

The predicate contains the verb (the action) and can include further clarifying information.

- Example

- This study investigated the relationship between the personal traits and clinical parameters.

- Example

- Mary gave her sheep a bath.

Direct and Indirect Objects

The direct object is the person, thing, or idea that receives an action.

- Example

- This study investigated the relationship between the personal traits and clinical parameters.

- Example

- Dolly made a cake.

The indirect object is the person, thing, or idea for which an action is being done.

- Example

- The national lab offered us an opportunity to work on an exciting new project.

- Example

- Mary gave her sheep a bath.

Transitive vs. Intransitive Verbs

A transitive verb is the action the subject takes on a direct object.

- Example

- We fabricated a composite.

Here, “we” is the subject, “fabricated” is the transitive verb, and “a composite” is the direct object.

An intransitive verb is a verb that does not have to be followed by an object. Intransitive verbs can function as predicates all on their own.

- Example

- We arrived.

We arrived early.

- Example

- I always eat.

I always eat before work.

“We” and “I” are the subjects; “arrived” and “eat” are intransitive verbs.

Subject Complement

A subject complement complements the subject by renaming or describing it. Subject complements always follow a linking verb, which is often a form of the verb “to be.”

- Example

- The material is a gold composite.

“Gold composite” renames the subject “the material.”

- Example

- Charlotte is very pretty.

“Pretty” describes the subject “Charlotte.”

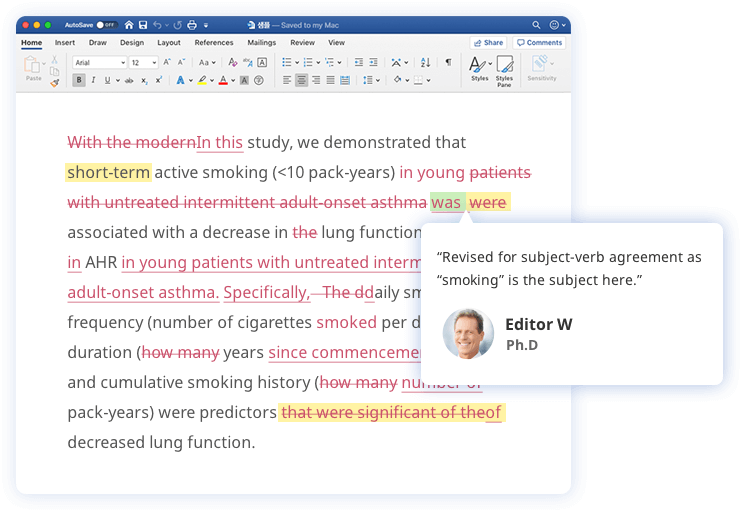

Get professional proofreading and expert feedback on any document!

-

Academic papers

-

Admissions essays

-

CVs/resumes

-

Business reports

-

Blog and website content

-

Personal essays

Compound Sentence Structure

A compound sentence is composed of two or more independent clauses connected by a coordinating conjunction or semicolon. Note that US English conventions dictate that coordinating conjunctions must be used with a comma when joining independent clauses.

Structure of a Compound Sentence: Independent clause + coordinating conjunction (or semicolon) + independent clause

List of coordinating conjunctions: and, but, yet, or, nor, for, so

- Example

- The material is a gold composite, and it was fabricated in clean room no. 45.

- Example

- Glenda usually eats before work, but today she could not.

- Example

- The proposed system has the advantage of a wide scope; it uses a novel algorithm that expands the range by a factor of ten.

Complex Sentence Structure

A complex sentence is composed of an independent clause and a dependent clause.

Structure of a Complex Sentence: Independent clause + subordinating conjunction (or relative pronoun) + dependent clause

- Example

- We built a new system because the previous model had to be narrowed in scope.

- Example

- Sarah will buy a train ticket if her flight is cancelled.

Compound-Complex Sentence Structure

A compound-complex sentence is composed of two or more independent clauses and one or more dependent clauses.

Structure of a Compound-Complex Sentence: Independent clause + subordinating conjunction + dependent clause + coordinating conjunction + independent clause

- Example

- The first method failed because it caused the wires to melt, but the second method succeeded in bending the wires without causing the same issue.

- Example

- Sarah’s flight took off before she started driving to the airport, so she drove to the train station instead.