Sentences with the word Theory?

Theory

Examples

- «the professor’s lectures were so abstruse that students tended to avoid them»; «a deep metaphysical theory«; «some recondite problem in historiography»

- «there was no agreement between theory and measurement»; «the results of two tests were in correspondence»

- «an economic theory alien to the spirit of capitalism»; «the mysticism so foreign to the French mind and temper»; «jealousy is foreign to her nature»

- «he is alone in the field of microbiology»; «this theory is altogether alone in its penetration of the problem»; «Bach was unique in his handling of counterpoint»; «craftsmen whose skill is unequaled»; «unparalleled athletic ability»; «a breakdown of law unparalleled in our history»

- «his theory is an amalgam of earlier ideas»

- «his theory is the antithesis of mine»

- «The same laws apply to you!»; «This theory holds for all irrational numbers»; «The same rules go for everyone»

- «This theory lends itself well to our new data»

- «assorted sizes»; «his disguises are many and various»; «various experiments have failed to disprove the theory«; «cited various reasons for his behavior»

- «the authorship of the theory is disputed»

- «a beautiful child»; «beautiful country»; «a beautiful painting»; «a beautiful theory«; «a beautiful party»

- «the stock market crashed on Black Friday»; «a calamitous defeat»; «the battle was a disastrous end to a disastrous campaign»; «such doctrines, if true, would be absolutely fatal to my theory«- Charles Darwin; «it is fatal to enter any war without the will to win it»- Douglas MacArthur; «a fateful error»

- «a casual (or cursory) inspection failed to reveal the house’s structural flaws»; «a passing glance»; «perfunctory courtesy»; «In his paper, he showed a very superficial understanding of psychoanalytic theory«

- «did you catch that allusion?»; «We caught something of his theory in the lecture»; «don’t catch your meaning»; «did you get it?»; «She didn’t get the joke»; «I just don’t get him»

- «fossils provided further confirmation of the evolutionary theory«

- «creationism denies the theory of evolution of species»

- «he offered a persuasive defense of the theory«

- «We have developed a new theory of evolution»

- «economic theory«

- «an empirical basis for an ethical theory«; «empirical laws»; «empirical data»; «an empirical treatment of a disease about which little is known»

- «according to quantum theory only certain energy levels are possible»

- «They popularized coffee in Washington State»; «Relativity theory was vulgarized by these authors»

- «This theory still holds»

- «Her shoes won’t hold up»; «This theory won’t hold water»

- «holism holds that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts»; «holistic theory has been applied to ecology and language and mental states»

- «a scientific hypothesis that survives experimental testing becomes a scientific theory«; «he proposed a fresh theory of alkalis that later was accepted in chemical practices»

- «ideological application of a theory«; «the drama’s symbolism was very ideological»

- «the inner logic of Cubism»; «the internal contradictions of the theory«; «the intimate structure of matter»

- «to start with a theory of unlimited freedom is to end up with unlimited despotism»- Philip Rahv; «the limitless reaches of outer space»

- «linguistic theory«

- «his explanation was a misappropriation of sociological theory«

- «an outstanding fact of our time is that nations poisoned by anti semitism proved less fortunate in regard to their own freedom»; «a new theory is the most prominent feature of the book»; «salient traits»; «a spectacular rise in prices»; «a striking thing about Picadilly Circus is the statue of Eros in the center»; «a striking resemblance between parent and child»

- «This new theory owes much to Einstein’s Relativity theory«

- «a hard theory to put into practice»; «differences between theory and praxis of communism»

- «the principle of superposition is the basis of the wave theory of light»

- «probabilistic quantum theory«

- «He proposed a new plan for dealing with terrorism»; «She proposed a new theory of relativity»; «The candidate projects himself as a moderate and a reformer»

- «a redemptive theory about life»- E.K.Brown

- «a simplistic theory of the universe»; «simplistic arguments of the ruling party»

- «a synoptic presentation of a physical theory«

- «theories can incorporate facts and laws and tested hypotheses»; «true in fact and theory«

- «the architect has a theory that more is less»; «they killed him on the theory that dead men tell no tales»

- «totalitarian theory and practice»; «operating in a totalistic fashion»

- «unburdened by an overarching theory«- Alex Inkeles

- «he seems to have been wholly unread in political theory«- V.L.Parrington

- «an untested drug»; «untested theory«; «an untried procedure»

The words “theory” and “theorem” sound very similar to one another. And they are often used in similar fields, but what exactly is the difference between the two of them? In this article, we’ll analyse what separates the two, and what are some examples of each of them.

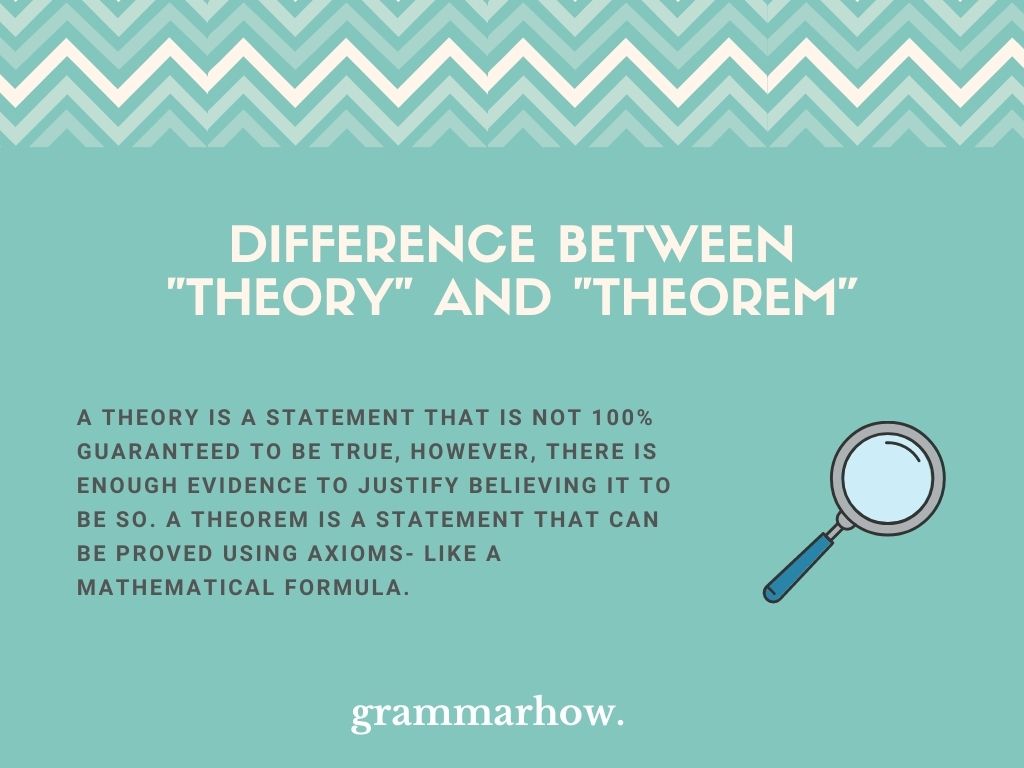

What Is The Difference Between “Theory” And “Theorem”?

A theory is a statement that is not 100% guaranteed to be true, however, there is enough evidence to justify believing it to be so. A Theorem is a statement that can be proved using axioms- like a mathematical formula.

For example, we have the THEORY of evolution. But Pythagoras THEOREM.

What Is A Theory?

When you hear the word “theory”, it can make people feel rather passionate, with phrases such as “that’s only a theory”. And yes, a theory is a statement that is not entirely guaranteed to be true. However, for a statement to become a theory, there does need to be some kind of evidence.

Some theories, such as evolution, are very difficult to prove. Due to our lack of time travel. However, the evidence from fossils and the consent of the scientific community is proof enough that it’s an idea that should be taken seriously.

A theory that is lacking in evidence is a hypothesis.

Hypothesis Vs Theory Vs Law – Difference Explained

In science, there are three common terms that some people get mixed up. These terms are “hypothesis”, “theory”, and “law”. Let me illustrate with an example.

Let’s say you’re on a walk and your metal detector finds a box, and within it is an old-looking photograph of Winston Churchill talking to Hitler. You might come up with a hypothesis that Churchill tried to stop the war via negotiations.

If you give the evidence to historians, they might gather more evidence, and agree. This then becomes a theory.

If you then invent a time machine and travel to find the theory to be true, you could call it a fact. In science, “facts” are sometimes called “laws”.

“In Theory” – What The Common Idiom Means

One phrase that you might have heard is “in theory”. This is not completely in line with the scientific use of the word, yet it does merge into it.

When someone says “in theory”, they refer to what should be but probably isn’t. For example, if I’m waiting for a bus, I might say “In theory, the bus will be here in 5 minutes. But knowing the current system, it will probably be closer to ten”.

Examples Of Popular Theories

Let’s take a look at some common theories that you might be familiar with.

- Black Holes

Nobody has ever seen one in real life, they’d be dead if they did. But black holes are tears in a space that suck everything into them, including light.

- Evolution

To put it bluntly, evolution is the idea that we evolved from apes to become human. It states that all living things started as microorganisms.

- Relativity

Einstein’s theory that time moves slower if you move faster.

- Gravity

The concept that gravity is part of the earth, and it’s the reason why things fall to the centre when you drop them.

4 Sentences That Use The Word “Theory”

- “I am a Christian, but I still think the theory of evolution still holds true. I can’t accept that all of that evidence is for nothing”

- “I have a theory that my brother is scared of cats and that’s why he doesn’t want to come round my house. But I might be wrong?”

- “Scientists are coming up with a new theory about why our skin starts to wrinkle when we get older. If their research goes well, they could end up finding a cure for ageing

- “The police had a theory about who killed all those people. But there was still not enough evidence for a conviction”.

Theorem

What Is A Theorem?

A theorem might sound similar to a theory, however, the two are unrelated.

A theorem is a fact proved via a chain of reasoning. When you combine arguments to come to a conclusion, the final conclusion is a theorem. IF all of the facts in the argument are true, then the theorem must also be true. However, as we’ll see later, whether the facts are true or not can be disputed.

A quick example of a theorem….

- Each person will want 2 cans of coke at the party.

- 5 people are coming to the party tomorrow.

- 2 times 5 is 10

- Therefore, I will need 10 cans of coke for the party tomorrow.

4 Sentences That Use The Word “Theorem”

- “When I was at school, I remember learning all about Pythagoras theorem. It was incredibly dull, but now that I’m an adult, I’m glad I learnt about it”

- “I started believing in God when I looked at Descartes Ontological Theorem. It just all clicked into place and started to make sense to me once I had finished reading his work”

- “All mathematics is just a string of philosophical theorems. Unlike other forms of philosophy however, there is no way we can question mathematics”

- “My maths teacher tried to teach us this new theorem that he had discovered. But we didn’t understand it because we were all twelve”.

Examples Of Common Theorems

And now, here are three theorems that you may be familiar with.

Pythagoras Theorem

a2+b2=c2

This is the idea that if you make squares from all three sides of a right-angled triangle, the area of the two shorter sides will add up to the area of the longest side.

Descartes Ontological Theorem.

God is perfect. Existence is better than non-existence. Therefore God exists.

The area of a circle.

Take the length from the middle of the circle to the edge and square it. Multiply that number by pi. And you have the area of the circle.

Conclusion

And that is the difference between a theory and a theorem. Hopefully, now you have a slightly better idea about how the two are separate and next time you need to, you’ll know which phrase to use.

As a general rule of thumb, science tends to prefer theories. However, mathematics tends to prefer theorems. But there are plenty of examples that break this rule.

The question you need to ask yourself is “have I deduced this from other facts? Or have I seen evidence towards this fact?”

Martin holds a Master’s degree in Finance and International Business. He has six years of experience in professional communication with clients, executives, and colleagues. Furthermore, he has teaching experience from Aarhus University. Martin has been featured as an expert in communication and teaching on Forbes and Shopify. Read more about Martin here.

Synonym: attitude, conception, explanation, hypothesis, idea, impression, inference, judgment, opinion, speculation, supposition, thought, view. Antonym: practice. Similar words: theoretical, more or less, theology, the other day, in the open, theological, story, history. Meaning: [‘θɪːrɪ /’θɪərɪ] n. 1. a well-substantiated explanation of some aspect of the natural world; an organized system of accepted knowledge that applies in a variety of circumstances to explain a specific set of phenomena 2. a tentative theory about the natural world; a concept that is not yet verified but that if true would explain certain facts or phenomena 3. a belief that can guide behavior.

Random good picture Not show

1. The human species, according to the best theory I can form of it, is composed of two distinct races, the man who borrows, and the man who lends.

2. In theory, the scheme sounds fine.

3. The biologist advanced a new theory of life.

4. We decided to test the theory experimentally.

5. She supports her theory with copious evidence.

6. This theory makes sense of an otherwise inexplicable phenomenon.

7. Later,findings verified the scientist’s theory.

8. Did you ever swallow the conspiracy theory about Kennedy?

9. No serious historian today accepts this theory.

10. It was a theory unsupported by evidence.

11. Some scientists have rejected evolutionary theory.

12. These new facts make the theory improbable.

13. Freudian theory has had a great influence on psychology.

14. The experiment confirmed my theory.

15. In theory, basketball is a non-contact sport.

16. The theory is not yet scientifically established.

17. Einstein’s theory marked a new epoch in mathematics.

18. Recent research seems to corroborate his theory.

19. Most of us don’t hold with his theory.

20. We found further scientific evidence for this theory.

21. Are you able to verify your account/allegation/report/theory?

22. I subscribe wholeheartedly to this theory.

22. Sentencedict.com try its best to gather and build good sentences.

23. Huxley was an exponent of Darwin’s theory of evolution.

24. The theory is irreconcilable with the facts.

25. Natural selection is a key element of Darwin’s theory of evolution.

26. Both quantum mechanics and chaos theory suggest a world constantly in flux.

27. One theory about the existence of extraterrestrial life rests on the presence of carbon compounds in meteorites.

28. What are the reasons for his rejection of the theory?

29. Radio signals received from the galaxy’s centre back up the black hole theory.

30. A scientist must produce evidence in support of a theory.

More similar words: theoretical, more or less, theology, the other day, in the open, theological, story, history, factory, category, territory, inventory, in memory of, from memory, laboratory, regulatory, conciliatory.

This means several things. It can be a scientific term that means a set of statements made to explain an event. It can mean the study of analysis as opposed to practice. It can be a belief or principle. Here are some examples of each.

- I have a theory about how that machine works, but it’s not tested.

- He studied Music Theory in school.

- In theory, this should work.

- The police staked out the house on the theory that criminals return to the scene of their crime.

I know the theory of attentive listening but I’m useless at the practice.

An example is: I have a theory that you don’t have a dictionary on hand or are just exceedingly lazy.

Many scientists accept the theory that the universe is growing larger.

Darwin spent more than twenty years working on his theory of evolution.

The scientific theory took many years to develop.

A hypothesis is an assumption, an idea that is proposed for the sake of argument so that it can be tested to see if it might be true.

In the scientific method, the hypothesis is constructed before any applicable research has been done, apart from a basic background review. You ask a question, read up on what has been studied before, and then form a hypothesis.

A hypothesis is usually tentative; it’s an assumption or suggestion made strictly for the objective of being tested.

A theory, in contrast, is a principle that has been formed as an attempt to explain things that have already been substantiated by data. It is used in the names of a number of principles accepted in the scientific community, such as the Big Bang Theory. Because of the rigors of experimentation and control, it is understood to be more likely to be true than a hypothesis is.

In non-scientific use, however, hypothesis and theory are often used interchangeably to mean simply an idea, speculation, or hunch, with theory being the more common choice.

Since this casual use does away with the distinctions upheld by the scientific community, hypothesis and theory are prone to being wrongly interpreted even when they are encountered in scientific contexts—or at least, contexts that allude to scientific study without making the critical distinction that scientists employ when weighing hypotheses and theories.

The most common occurrence is when theory is interpreted—and sometimes even gleefully seized upon—to mean something having less truth value than other scientific principles. (The word law applies to principles so firmly established that they are almost never questioned, such as the law of gravity.)

This mistake is one of projection: since we use theory in general to mean something lightly speculated, then it’s implied that scientists must be talking about the same level of uncertainty when they use theory to refer to their well-tested and reasoned principles.

The distinction has come to the forefront particularly on occasions when the content of science curricula in schools has been challenged—notably, when a school board in Georgia put stickers on textbooks stating that evolution was «a theory, not a fact, regarding the origin of living things.» As Kenneth R. Miller, a cell biologist at Brown University, has said, a theory «doesn’t mean a hunch or a guess. A theory is a system of explanations that ties together a whole bunch of facts. It not only explains those facts, but predicts what you ought to find from other observations and experiments.”

While theories are never completely infallible, they form the basis of scientific reasoning because, as Miller said «to the best of our ability, we’ve tested them, and they’ve held up.»

- approach

- argument

- assumption

- code

- concept

- doctrine

- idea

- ideology

- method

- philosophy

- plan

- position

- premise

- proposal

- provision

- rationale

- scheme

- speculation

- suspicion

- system

- thesis

- understanding

- base

- basis

- codification

- conditions

- conjecture

- dogma

- feeling

- foundation

- grounds

- guess

- guesswork

- hunch

- impression

- outlook

- postulate

- presentiment

- presumption

- shot

- stab

- supposal

- supposition

- surmise

- theorem

- formularization

- suppose

- systemization

On this page you’ll find 89 synonyms, antonyms, and words related to theory, such as: approach, argument, assumption, code, concept, and doctrine.

Roget’s 21st Century Thesaurus, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by the Philip Lief Group.

TRY USING theory

See how your sentence looks with different synonyms.

How to use theory in a sentence

“Our prosecutors have all too often inserted themselves into the political process based on the flimsiest of legal theories,” Barr went on.

THE STUNNING HYPOCRISY OF BILL BARRANDREW PROKOPSEPTEMBER 17, 2020VOX

In retrospect, the Falco looks like it might have been a simple corporate diversion to throw curious types off the GSX-R trail—a conspiracy theory that unravels when you factor in that the GSX-R had already been introduced earlier that year.

22 OF THE WEIRDEST CONCEPT MOTORCYCLES EVER MADEBY JOHN BURNS/CYCLE WORLDSEPTEMBER 10, 2020POPULAR-SCIENCE

SYNONYM OF THE DAY

OCTOBER 26, 1985

WORDS RELATED TO THEORY

- acceptance

- accepting

- assuming

- belief

- conjecture

- expectation

- fancy

- guess

- hunch

- hypothesis

- inference

- posit

- postulate

- postulation

- premise

- presumption

- presupposition

- shot

- shot in the dark

- sneaking suspicion

- stab

- supposal

- supposition

- surmise

- suspicion

- theorization

- theory

- brasses

- chutzpah

- cockiness

- conceits

- imperiousness

- insolence

- nerves

- presumptions

- prides

- sasses

- self-importances

- antecedent

- assumption

- authority

- axiom

- backbone

- background

- backing

- base

- bedrock

- cause

- center

- chief ingredient

- core

- crux

- data

- dictum

- essence

- essential

- evidence

- explanation

- footing

- fundamental

- hard fact

- heart

- infrastructure

- justification

- keynote

- keystone

- law

- nexus

- nucleus

- postulate

- premise

- presumption

- presupposition

- principal element

- principle

- proof

- reason

- root

- rudiment

- sanction

- security

- source

- substratum

- support

- theorem

- theory

- underpinning

- warrant

- assumption

- concept

- credence

- credo

- creed

- doctrine

- dogma

- faith

- fundamental

- gospel

- gospel truth

- hypothesis

- idea

- ideology

- law

- opinion

- postulate

- precept

- principle

- say-so

- tenet

- theorem

- theory

- abstraction

- apprehension

- approach

- big idea

- brain wave

- brainchild

- conceit

- conception

- conceptualization

- consideration

- fool notion

- hypothesis

- image

- impression

- intellection

- notion

- perception

- slant

- supposition

- theory

- thought

- twist

- view

- wrinkle

- abstractions

- apprehensions

- approaches

- big ideas

- brain waves

- brainchilds

- conceits

- conceptions

- conceptualization

- considerations

- fool notions

- hypotheses

- images

- impressions

- intellections

- notions

- perceptions

- slants

- suppositions

- theories

- thoughts

- twists

- views

- wrinkles

Roget’s 21st Century Thesaurus, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by the Philip Lief Group.

A theory is a rational type of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the results of such thinking. The process of contemplative and rational thinking is often associated with such processes as observational study or research. Theories may be scientific, belong to a non-scientific discipline, or no discipline at all. Depending on the context, a theory’s assertions might, for example, include generalized explanations of how nature works. The word has its roots in ancient Greek, but in modern use it has taken on several related meanings.

In modern science, the term «theory» refers to scientific theories, a well-confirmed type of explanation of nature, made in a way consistent with the scientific method, and fulfilling the criteria required by modern science. Such theories are described in such a way that scientific tests should be able to provide empirical support for it, or empirical contradiction («falsify») of it. Scientific theories are the most reliable, rigorous, and comprehensive form of scientific knowledge,[1] in contrast to more common uses of the word «theory» that imply that something is unproven or speculative (which in formal terms is better characterized by the word hypothesis).[2] Scientific theories are distinguished from hypotheses, which are individual empirically testable conjectures, and from scientific laws, which are descriptive accounts of the way nature behaves under certain conditions.

Theories guide the enterprise of finding facts rather than of reaching goals, and are neutral concerning alternatives among values.[3]: 131 A theory can be a body of knowledge, which may or may not be associated with particular explanatory models. To theorize is to develop this body of knowledge.[4]: 46

The word theory or «in theory» is sometimes used erroneously by people to explain something which they individually did not experience or test before.[5] In those instances, semantically, it is being substituted for another concept, a hypothesis. Instead of using the word «hypothetically», it is replaced by a phrase: «in theory». In some instances the theory’s credibility could be contested by calling it «just a theory» (implying that the idea has not even been tested).[6] Hence, that word «theory» is very often contrasted to «practice» (from Greek praxis, πρᾶξις) a Greek term for doing, which is opposed to theory.[6] A «classical example» of the distinction between «theoretical» and «practical» uses the discipline of medicine: medical theory involves trying to understand the causes and nature of health and sickness, while the practical side of medicine is trying to make people healthy. These two things are related but can be independent, because it is possible to research health and sickness without curing specific patients, and it is possible to cure a patient without knowing how the cure worked.[a]

Ancient usage[edit]

The English word theory derives from a technical term in philosophy in Ancient Greek. As an everyday word, theoria, θεωρία, meant «looking at, viewing, beholding», but in more technical contexts it came to refer to contemplative or speculative understandings of natural things, such as those of natural philosophers, as opposed to more practical ways of knowing things, like that of skilled orators or artisans.[b] English-speakers have used the word theory since at least the late 16th century.[7] Modern uses of the word theory derive from the original definition, but have taken on new shades of meaning, still based on the idea of a theory as a thoughtful and rational explanation of the general nature of things.

Although it has more mundane meanings in Greek, the word θεωρία apparently developed special uses early in the recorded history of the Greek language. In the book From Religion to Philosophy, Francis Cornford suggests that the Orphics used the word theoria to mean «passionate sympathetic contemplation».[8] Pythagoras changed the word to mean «the passionless contemplation of rational, unchanging truth» of mathematical knowledge, because he considered this intellectual pursuit the way to reach the highest plane of existence.[9] Pythagoras emphasized subduing emotions and bodily desires to help the intellect function at the higher plane of theory. Thus, it was Pythagoras who gave the word theory the specific meaning that led to the classical and modern concept of a distinction between theory (as uninvolved, neutral thinking) and practice.[10]

Aristotle’s terminology, as already mentioned, contrasts theory with praxis or practice, and this contrast exists till today. For Aristotle, both practice and theory involve thinking, but the aims are different. Theoretical contemplation considers things humans do not move or change, such as nature, so it has no human aim apart from itself and the knowledge it helps create. On the other hand, praxis involves thinking, but always with an aim to desired actions, whereby humans cause change or movement themselves for their own ends. Any human movement that involves no conscious choice and thinking could not be an example of praxis or doing.[c]

Formality[edit]

Theories are analytical tools for understanding, explaining, and making predictions about a given subject matter. There are theories in many and varied fields of study, including the arts and sciences. A formal theory is syntactic in nature and is only meaningful when given a semantic component by applying it to some content (e.g., facts and relationships of the actual historical world as it is unfolding). Theories in various fields of study are expressed in natural language, but are always constructed in such a way that their general form is identical to a theory as it is expressed in the formal language of mathematical logic. Theories may be expressed mathematically, symbolically, or in common language, but are generally expected to follow principles of rational thought or logic.

Theory is constructed of a set of sentences that are entirely true statements about the subject under consideration. However, the truth of any one of these statements is always relative to the whole theory. Therefore, the same statement may be true with respect to one theory, and not true with respect to another. This is, in ordinary language, where statements such as «He is a terrible person» cannot be judged as true or false without reference to some interpretation of who «He» is and for that matter what a «terrible person» is under the theory.[11]

Sometimes two theories have exactly the same explanatory power because they make the same predictions. A pair of such theories is called indistinguishable or observationally equivalent, and the choice between them reduces to convenience or philosophical preference.

The form of theories is studied formally in mathematical logic, especially in model theory. When theories are studied in mathematics, they are usually expressed in some formal language and their statements are closed under application of certain procedures called rules of inference. A special case of this, an axiomatic theory, consists of axioms (or axiom schemata) and rules of inference. A theorem is a statement that can be derived from those axioms by application of these rules of inference. Theories used in applications are abstractions of observed phenomena and the resulting theorems provide solutions to real-world problems. Obvious examples include arithmetic (abstracting concepts of number), geometry (concepts of space), and probability (concepts of randomness and likelihood).

Gödel’s incompleteness theorem shows that no consistent, recursively enumerable theory (that is, one whose theorems form a recursively enumerable set) in which the concept of natural numbers can be expressed, can include all true statements about them. As a result, some domains of knowledge cannot be formalized, accurately and completely, as mathematical theories. (Here, formalizing accurately and completely means that all true propositions—and only true propositions—are derivable within the mathematical system.) This limitation, however, in no way precludes the construction of mathematical theories that formalize large bodies of scientific knowledge.

Underdetermination[edit]

A theory is underdetermined (also called indeterminacy of data to theory) if a rival, inconsistent theory is at least as consistent with the evidence. Underdetermination is an epistemological issue about the relation of evidence to conclusions.

A theory that lacks supporting evidence is generally, more properly, referred to as a hypothesis.

Intertheoretic reduction and elimination[edit]

If a new theory better explains and predicts a phenomenon than an old theory (i.e., it has more explanatory power), we are justified in believing that the newer theory describes reality more correctly. This is called an intertheoretic reduction because the terms of the old theory can be reduced to the terms of the new one. For instance, our historical understanding about sound, «light» and heat have been reduced to wave compressions and rarefactions, electromagnetic waves, and molecular kinetic energy, respectively. These terms, which are identified with each other, are called intertheoretic identities. When an old and new theory are parallel in this way, we can conclude that the new one describes the same reality, only more completely.

When a new theory uses new terms that do not reduce to terms of an older theory, but rather replace them because they misrepresent reality, it is called an intertheoretic elimination. For instance, the obsolete scientific theory that put forward an understanding of heat transfer in terms of the movement of caloric fluid was eliminated when a theory of heat as energy replaced it. Also, the theory that phlogiston is a substance released from burning and rusting material was eliminated with the new understanding of the reactivity of oxygen.

Versus theorems[edit]

Theories are distinct from theorems. A theorem is derived deductively from axioms (basic assumptions) according to a formal system of rules, sometimes as an end in itself and sometimes as a first step toward being tested or applied in a concrete situation; theorems are said to be true in the sense that the conclusions of a theorem are logical consequences of the axioms. Theories are abstract and conceptual, and are supported or challenged by observations in the world. They are ‘rigorously tentative’, meaning that they are proposed as true and expected to satisfy careful examination to account for the possibility of faulty inference or incorrect observation. Sometimes theories are incorrect, meaning that an explicit set of observations contradicts some fundamental objection or application of the theory, but more often theories are corrected to conform to new observations, by restricting the class of phenomena the theory applies to or changing the assertions made. An example of the former is the restriction of classical mechanics to phenomena involving macroscopic length scales and particle speeds much lower than the speed of light.

The theory–practice gap[edit]

Theory is often distinguished from practice. The question of whether theoretical models of work are relevant to work itself is of interest to scholars of professions such as medicine, engineering, and law, and management.[12]: 802

This gap between theory and practice has been framed as a knowledge transfer where there is a task of translating research knowledge to be application in practice, and ensuring that practitioners are made aware of it academics have been criticized for not attempting to transfer the knowledge they produce to practitioners.[12]: 804 [13] Another framing supposes that theory and knowledge seek to understand different problems and model the world in different words (using different ontologies and epistemologies) . Another framing says that research does not produce theory that is relevant to practice.[12]: 803

In the context of management, Van de Van and Johnson propose a form of engaged scholarship where scholars examine problems that occur in practice, in an interdisciplinary fashion, producing results that create both new practical results as well as new theoretical models, but targeting theoretical results shared in an academic fashion.[12]: 815 They use a metaphor of «arbitrage» of ideas between disciplines, distinguishing it from collaboration.[12]: 803

Scientific[edit]

In science, the term «theory» refers to «a well-substantiated explanation of some aspect of the natural world, based on a body of facts that have been repeatedly confirmed through observation and experiment.»[14][15] Theories must also meet further requirements, such as the ability to make falsifiable predictions with consistent accuracy across a broad area of scientific inquiry, and production of strong evidence in favor of the theory from multiple independent sources (consilience).

The strength of a scientific theory is related to the diversity of phenomena it can explain, which is measured by its ability to make falsifiable predictions with respect to those phenomena. Theories are improved (or replaced by better theories) as more evidence is gathered, so that accuracy in prediction improves over time; this increased accuracy corresponds to an increase in scientific knowledge. Scientists use theories as a foundation to gain further scientific knowledge, as well as to accomplish goals such as inventing technology or curing diseases.

Definitions from scientific organizations[edit]

The United States National Academy of Sciences defines scientific theories as follows:

The formal scientific definition of «theory» is quite different from the everyday meaning of the word. It refers to a comprehensive explanation of some aspect of nature that is supported by a vast body of evidence. Many scientific theories are so well established that no new evidence is likely to alter them substantially. For example, no new evidence will demonstrate that the Earth does not orbit around the sun (heliocentric theory), or that living things are not made of cells (cell theory), that matter is not composed of atoms, or that the surface of the Earth is not divided into solid plates that have moved over geological timescales (the theory of plate tectonics) … One of the most useful properties of scientific theories is that they can be used to make predictions about natural events or phenomena that have not yet been observed.[16]

From the American Association for the Advancement of Science:

A scientific theory is a well-substantiated explanation of some aspect of the natural world, based on a body of facts that have been repeatedly confirmed through observation and experiment. Such fact-supported theories are not «guesses» but reliable accounts of the real world. The theory of biological evolution is more than «just a theory.» It is as factual an explanation of the universe as the atomic theory of matter or the germ theory of disease. Our understanding of gravity is still a work in progress. But the phenomenon of gravity, like evolution, is an accepted fact.[15]

The term theory is not appropriate for describing scientific models or untested, but intricate hypotheses.

Philosophical views[edit]

The logical positivists thought of scientific theories as deductive theories—that a theory’s content is based on some formal system of logic and on basic axioms. In a deductive theory, any sentence which is a logical consequence of one or more of the axioms is also a sentence of that theory.[11] This is called the received view of theories.

In the semantic view of theories, which has largely replaced the received view,[17][18] theories are viewed as scientific models. A model is a logical framework intended to represent reality (a «model of reality»), similar to the way that a map is a graphical model that represents the territory of a city or country. In this approach, theories are a specific category of models that fulfill the necessary criteria. (See Theories as models for further discussion.)

In physics[edit]

In physics the term theory is generally used for a mathematical framework—derived from a small set of basic postulates (usually symmetries, like equality of locations in space or in time, or identity of electrons, etc.)—which is capable of producing experimental predictions for a given category of physical systems. One good example is classical electromagnetism, which encompasses results derived from gauge symmetry (sometimes called gauge invariance) in a form of a few equations called Maxwell’s equations. The specific mathematical aspects of classical electromagnetic theory are termed «laws of electromagnetism», reflecting the level of consistent and reproducible evidence that supports them. Within electromagnetic theory generally, there are numerous hypotheses about how electromagnetism applies to specific situations. Many of these hypotheses are already considered adequately tested, with new ones always in the making and perhaps untested.

Regarding the term «theoretical»[edit]

Certain tests may be infeasible or technically difficult. As a result, theories may make predictions that have not been confirmed or proven incorrect. These predictions may be described informally as «theoretical». They can be tested later, and if they are incorrect, this may lead to revision, invalidation, or rejection of the theory.

[19]

Mathematical[edit]

In mathematics the use of the term theory is different, necessarily so, since mathematics contains no explanations of natural phenomena, per se, even though it may help provide insight into natural systems or be inspired by them. In the general sense, a mathematical theory is a branch of or topic in mathematics, such as Set theory, Number theory, Group theory, Probability theory, Game theory, Control theory, Perturbation theory, etc., such as might be appropriate for a single textbook.

In the same sense, but more specifically, the word theory is an extensive, structured collection of theorems, organized so that the proof of each theorem only requires the theorems and axioms that preceded it (no circular proofs), occurs as early as feasible in sequence (no postponed proofs), and the whole is as succinct as possible (no redundant proofs).[d] Ideally, the sequence in which the theorems are presented is as easy to understand as possible, although illuminating a branch of mathematics is the purpose of textbooks, rather than the mathematical theory they might be written to cover.

Philosophical[edit]

A theory can be either descriptive as in science, or prescriptive (normative) as in philosophy.[20] The latter are those whose subject matter consists not of empirical data, but rather of ideas. At least some of the elementary theorems of a philosophical theory are statements whose truth cannot necessarily be scientifically tested through empirical observation.

A field of study is sometimes named a «theory» because its basis is some initial set of assumptions describing the field’s approach to the subject. These assumptions are the elementary theorems of the particular theory, and can be thought of as the axioms of that field. Some commonly known examples include set theory and number theory; however literary theory, critical theory, and music theory are also of the same form.

Metatheory[edit]

One form of philosophical theory is a metatheory or meta-theory. A metatheory is a theory whose subject matter is some other theory or set of theories. In other words, it is a theory about theories. Statements made in the metatheory about the theory are called metatheorems.

Political[edit]

A political theory is an ethical theory about the law and government. Often the term «political theory» refers to a general view, or specific ethic, political belief or attitude, thought about politics.

Jurisprudential[edit]

In social science, jurisprudence is the philosophical theory of law. Contemporary philosophy of law addresses problems internal to law and legal systems, and problems of law as a particular social institution.

Examples[edit]

Most of the following are scientific theories. Some are not, but rather encompass a body of knowledge or art, such as Music theory and Visual Arts Theories.

- Anthropology: Carneiro’s circumscription theory

- Astronomy: Alpher–Bethe–Gamow theory — B2FH Theory — Copernican theory — Newton’s theory of gravitation — Hubble’s law — Kepler’s laws of planetary motion Ptolemaic theory

- Biology: Cell theory — Chemiosmotic theory — Evolution — Germ theory — Symbiogenesis

- Chemistry: Molecular theory — Kinetic theory of gases — Molecular orbital theory — Valence bond theory — Transition state theory — RRKM theory — Chemical graph theory — Flory–Huggins solution theory — Marcus theory — Lewis theory (successor to Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory) — HSAB theory — Debye–Hückel theory — Thermodynamic theory of polymer elasticity — Reptation theory — Polymer field theory — Møller–Plesset perturbation theory — density functional theory — Frontier molecular orbital theory — Polyhedral skeletal electron pair theory — Baeyer strain theory — Quantum theory of atoms in molecules — Collision theory — Ligand field theory (successor to Crystal field theory) — Variational transition-state theory — Benson group increment theory — Specific ion interaction theory

- Climatology: Climate change theory (general study of climate changes) and anthropogenic climate change (ACC)/ global warming (AGW) theories (due to human activity)

- Computer Science: Automata theory — Queueing theory

- Cosmology: Big Bang Theory — Cosmic inflation — Loop quantum gravity — Superstring theory — Supergravity — Supersymmetric theory — Multiverse theory — Holographic principle — Quantum gravity — M-theory

- Economics: Macroeconomic theory — Microeconomic theory — Law of Supply and demand

- Education: Constructivist theory — Critical pedagogy theory — Education theory — Multiple intelligence theory — Progressive education theory

- Engineering: Circuit theory — Control theory — Signal theory — Systems theory — Information theory

- Film: Film theory

- Geology: Plate tectonics

- Humanities: Critical theory

- Jurisprudence or ‘Legal theory’: Natural law — Legal positivism — Legal realism — Critical legal studies

- Law: see Jurisprudence; also Case theory

- Linguistics: X-bar theory — Government and Binding — Principles and parameters — Universal grammar

- Literature: Literary theory

- Mathematics: Approximation theory — Arakelov theory — Asymptotic theory — Bifurcation theory — Catastrophe theory — Category theory — Chaos theory — Choquet theory — Coding theory — Combinatorial game theory — Computability theory — Computational complexity theory — Deformation theory — Dimension theory — Ergodic theory — Field theory — Galois theory — Game theory — Gauge theory — Graph theory — Group theory — Hodge theory — Homology theory — Homotopy theory — Ideal theory — Intersection theory — Invariant theory — Iwasawa theory — K-theory — KK-theory — Knot theory — L-theory — Lie theory — Littlewood–Paley theory — Matrix theory — Measure theory — Model theory — Module theory — Morse theory — Nevanlinna theory — Number theory — Obstruction theory — Operator theory — Order theory — PCF theory — Perturbation theory — Potential theory — Probability theory — Ramsey theory — Rational choice theory — Representation theory — Ring theory — Set theory — Shape theory — Small cancellation theory — Spectral theory — Stability theory — Stable theory — Sturm–Liouville theory — Surgery theory — Twistor theory — Yang–Mills theory

- Music: Music theory

- Philosophy: Proof theory — Speculative reason — Theory of truth — Type theory — Value theory — Virtue theory

- Physics: Acoustic theory — Antenna theory — Atomic theory — BCS theory — Conformal field theory — Dirac hole theory — Dynamo theory — Landau theory — M-theory — Perturbation theory — Theory of relativity (successor to classical mechanics) — Gauge theory — Quantum field theory — Scattering theory — String theory — Quantum information theory

- Psychology: Theory of mind — Cognitive dissonance theory — Attachment theory — Object permanence — Poverty of stimulus — Attribution theory — Self-fulfilling prophecy — Stockholm syndrome

- Public Budgeting: Incrementalism — Zero-based budgeting

- Public Administration: Organizational theory

- Semiotics: Intertheoricity – Transferogenesis

- Sociology: Critical theory — Engaged theory — Social theory — Sociological theory – Social capital theory

- Statistics: Extreme value theory

- Theatre: Performance theory

- Visual Arts: Aesthetics — Art educational theory — Architecture — Composition — Anatomy — Color theory — Perspective — Visual perception — Geometry — Manifolds

- Other: Obsolete scientific theories

See also[edit]

- Falsifiability

- Hypothesis testing

- Physical law

- Predictive power

- Testability

- Theoretical definition

Notes[edit]

- ^ See for example Hippocrates Praeceptiones, Part 1. Archived 12 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The word theoria occurs in Greek philosophy, for example, that of Plato. It is a statement of how and why particular facts are related. It is related to words for θεωρός «spectator», θέα thea «a view» + ὁρᾶν horan «to see», literally «looking at a show». See for example dictionary entries at Perseus website.

- ^ The LSJ cites two passages of Aristotle as examples, both from the Metaphysics and involving the definition of natural science: 11.1064a17, «it is clear that natural science (φυσικὴν ἐπιστήμην) must be neither practical (πρακτικὴν) nor productive (ποιητικὴν), but speculative (θεωρητικὴν)» and 6.1025b25, «Thus if every intellectual activity [διάνοια] is either practical or productive or speculative (θεωρητική), physics (φυσικὴ) will be a speculative [θεωρητική] science.» So Aristotle actually made a three way distinction between practical, theoretical and productive or technical—or between doing, contemplating or making. All three types involve thinking, but are distinguished by what causes the objects of thought to move or change.

- ^ Succinct in this sense refers to the whole collection of proofs, and means that any one proof contains no embedded stages that are equivalent to parts of proofs of later theorems.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Schafersman, Steven D. «An Introduction to Science».

- ^ National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine (2008). Science, evolution, and creationism. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0309105866. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^ McMurray, Foster (July 1955). «Preface to an Autonomous Discipline of Education». Educational Theory. 5 (3): 129–140. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5446.1955.tb01131.x.

- ^ Thomas, Gary (2007). Education and theory : strangers in paradigms. Maidenhead: Open Univ. Press. ISBN 9780335211791.

- ^ What is a Theory?. American Museum of Natural History.

- ^ a b David J Pfeiffer. Scientific Theory vs Law. Science Journal (on medium.com). 30 January 2017

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «theory». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ^ Cornford, Francis Macdonald (8 November 1991). From religion to philosophy: a study in the origins of western speculation. Princeton University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-691-02076-1.

- ^ Cornford, Francis M. (1991). From Religion to Philosophy: a study in the origins of western speculation. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 200. ISBN 0-691-02076-0.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (1945). History of Western Philosophy.

- ^ a b Curry, Haskell, Foundations of Mathematical Logic

- ^ a b c d e Van De Ven, Andrew H.; Johnson, Paul E. (1 October 2006). «Knowledge for Theory and Practice». Academy of Management Review. 31 (4): 802–821. doi:10.5465/amr.2006.22527385. ISSN 0363-7425.

- ^ Beer, Michael (1 March 2001). «Why Management Research Findings Are Unimplementable: An Action Science Perspective». Reflections: The SoL Journal. 2 (3): 58–65. doi:10.1162/152417301570383.

- ^ National Academy of Sciences, 1999

- ^ a b «AAAS Evolution Resources».

- ^ Science, Evolution, and Creationism. National Academy of Sciences. 2008. doi:10.17226/11876. ISBN 978-0-309-10586-6.

- ^ Suppe, Frederick (1998). «Understanding Scientific Theories: An Assessment of Developments, 1969–1998» (PDF). Philosophy of Science. 67: S102–S115. doi:10.1086/392812. S2CID 37361274. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ^ Halvorson, Hans (2012). «What Scientific Theories Could Not Be» (PDF). Philosophy of Science. 79 (2): 183–206. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.692.8455. doi:10.1086/664745. S2CID 37897853. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ^ Bradford, Alina (25 March 2015). «What Is a Law in Science?». Live Science. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ Kneller, George Frederick (1964). Introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: J. Wiley. p. 93.

Sources[edit]

- Davidson Reynolds, Paul (1971). A primer in theory construction. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Guillaume, Astrid (2015). « Intertheoricity: Plasticity, Elasticity and Hybridity of Theories. Part II: Semiotics of Transferogenesis », in Human and Social studies, Vol.4, N°2 (2015), éd.Walter de Gruyter, Boston, Berlin, pp. 59–77.

- Guillaume, Astrid (2015). « The Intertheoricity : Plasticity, Elasticity and Hybridity of Theories », in Human and Social studies, Vol.4, N°1 (2015), éd.Walter de Gruyter, Boston, Berlin, pp. 13–29.

- Hawking, Stephen (1996). A Brief History of Time (Updated and expanded ed.). New York: Bantam Books, p. 15.

- James, Paul (2006). Globalism, Nationalism, Tribalism: Bringing Theory Back In. London, England: Sage Publications.

- Matson, Ronald Allen, «Comparing scientific laws and theories», Biology, Kennesaw State University.

- Popper, Karl (1963), Conjectures and Refutations, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, UK, pp. 33–39. Reprinted in Theodore Schick (ed., 2000), Readings in the Philosophy of Science, Mayfield Publishing Company, Mountain View, California, USA, pp. 9–13.

- Zima, Peter V. (2007). «What is theory? Cultural theory as discourse and dialogue». London: Continuum (translated from: Was ist Theorie? Theoriebegriff und Dialogische Theorie in der Kultur- und Sozialwissenschaften. Tübingen: A. Franke Verlag, 2004).

External links[edit]

- «How science works: Even theories change», Understanding Science by the University of California Museum of Paleontology.

- What is a Theory?