Synonym: bias, complicated, confused, inclination, involved, leaning, mixed, prejudice. Antonym: brief, plain, simple. Similar words: complexity, sample, temple, comply, for example, implement, complaint, comply with. Meaning: [‘kɒmpleks] n. 1. a conceptual whole made up of complicated and related parts 2. a compound described in terms of the central atom to which other atoms are bound or coordinated 3. (psychoanalysis) a combination of emotions and impulses that have been rejected from awareness but still influence a person’s behavior 4. a whole structure (as a building) made up of interconnected or related structures. adj. complicated in structure; consisting of interconnected parts.

Random good picture Not show

(1) In a complex world,to insist upon simplicity is foolish.

(2) The company has a complex organizational structure.

(3) In this new book, Harrison brilliantly disentangles complex debates.

(4) He was an unusually complex man.

(5) Photosynthesis is a highly complex process.

(6) The task requires a good comprehension of complex instructions.

(7) The plot of the TV series is quite complex.

(8) Some monkeys have a very complex social hierarchy.

(9) This is a highly complex matter.

(10) The mechanics of the process are quite complex.

(11) It is a simple melody with complex harmonies.

(12) The structure of this protein is particularly complex.

(13) Later centuries saw the development of a complex transport system.

(14) The risks can be so complex that banks hire mathematicians to puzzle them out.

(15) He found his way through the complex maze of corridors.

(16) As the world becomes more complex, some things do, of course, standardize and globalize.

(17) His complex anger flamed afresh , and Ruth was in terror of him.

(18) The new sports complex is on target to open in June.

(19) He was studying the complex similarities and differences between humans and animals.

(20) The new sports complex has everything needed for many different activities.

(21) It is impossible to understand the complex nature of the human mind.

(22) He put over a complex and difficult business deal.

(23) The army is an extremely complex organism.

(24) It’s a useful introduction to an extremely complex subject.

(25) Buddhist ethics are simple but its practices are very complex to a western mind.

(26) His skill lies in his ability to communicate quite complex ideas very simply. Sentencedict.com

(27) Don’t keep on at him about his handwriting or he’ll get a complex.

(28) The pilot has to carry out a series of complex manoeuvres.

(29) The architect had produced a scale model of the proposed shopping complex.

(30) A careful driver will often stop talking before carrying out a complex manoeuvre.

More similar words: complexity, sample, temple, comply, for example, implement, complaint, comply with, compliance, implementation, complicated, complain about, accomplishment, accomplishments, flexible, flexibility, plea, plead, apple, purple, people, couple, principle, multiple, imply, a couple of, employ, simply, employee, employer.

Definition of Complex

difficult and complicated

Examples of Complex in a sentence

A complex problem surfaced during the faculty meeting when there were not enough staff members to serve food that day to the hundreds of customers who showed up.

🔊

Students in the algebra class struggled with the complex word problems because they had no idea how to solve them.

🔊

Due to the complex escape plan from the building, many people perished in the structure since they figure out which way to leave the building.

🔊

As the motorists were trying to proceed through the complex intersection, it was impossible to determine which lane belonged to which motorist.

🔊

Since the job training didn’t include CPR and first aid, a complex situation arose when the child began to choke on something.

🔊

Other words in the Difficulty category:

Most Searched Words (with Video)

Fact-checked by

Paul Mazzola

What is a complex sentence?

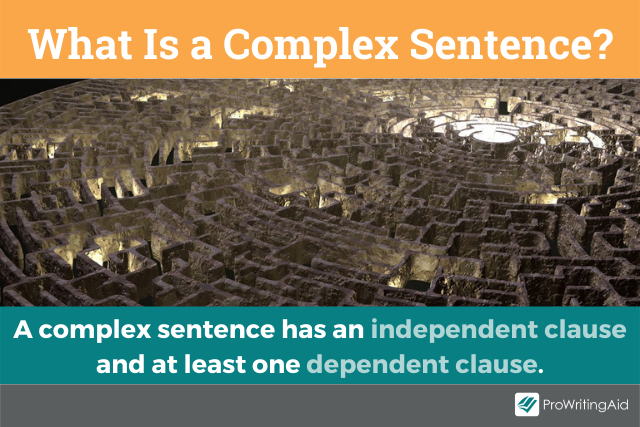

A complex sentence is one independent clause and at least one dependent clause joined by a subordinating conjunction. Complex sentences are one of the four basic types of sentences in the English language.

Complex sentences require at least three parts:

-

Independent clause

-

Subordinating conjunction

-

Dependent clause or clauses

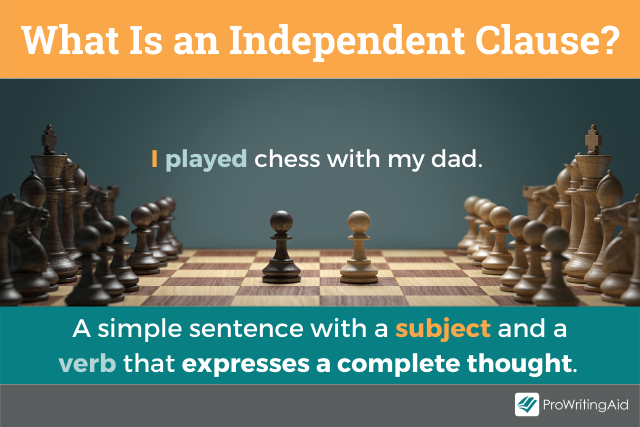

Independent clauses

In writing, entire ideas expressed using a noun and verb (a subject and predicate) create independent clauses. Independent clauses can be complete sentences on their own.

Here is a wonderful succession of simple sentences (each an independent clause) from Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis:

I’m in the midst of getting out of bed. Just have patience for a short moment! Things are not going so well as I thought. But things are all right.

Things certainly are not going well for Kafka’s protagonist because Gregor Samsa has turned into a “monstrous verminous bug.”

Dependent clauses

Dependent clauses, also called the subordinate clause, have a noun and verb but fail to express a complete thought. In these sentences penned by Kafka, the dependent clauses are underlined:

-

No matter how hard he threw himself onto his right side, he always rolled again onto his back.

-

If I were to try that with my boss, I’d be thrown out on the spot.

-

Because the lodgers sometimes also took their evening meal at home in the common living room, the door to the living room stayed shut on many evenings.

These examples have nouns and verbs, but they are not complete thoughts. If all Kafka had written was, “No matter how hard he threw himself onto his right side,” you would have no idea what was happening to Gregor Samsa.

If left by themselves, dependent clauses are sentence fragments.

Complex sentence examples

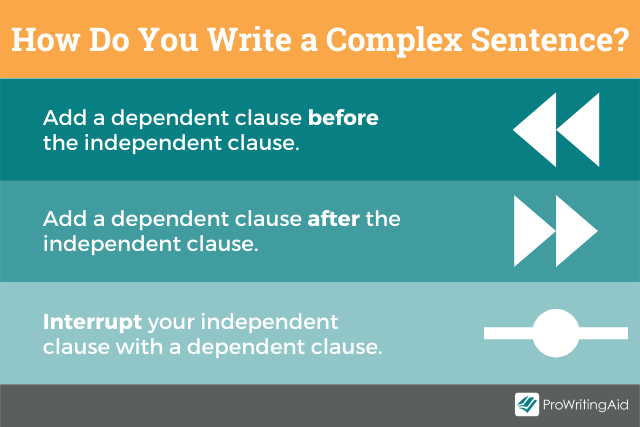

You can write complex sentences in a few different ways. Here are some rules to help you construct complex sentences:

-

Dependent Clause + Independent Clause (comma splits the clause)

-

Independent Clause + Dependent Clause (comma usually does not split the clause)

Here are four examples of complex sentences where the dependent clause comes first:

-

When I was a child, I love playing baseball.

-

As you may know, writing with correct English grammar can be challenging.

-

Since summer is around the corner, we all bought new bathing suits.

-

Because she was late for work, she was frustrated.

Here are those same four examples with the independent clause first:

-

I enjoyed playing baseball when I was a child.

-

Writing with correct English grammar can be challenging, as you may know.

-

We all bought new bathing suits since summer is around the corner.

-

She was frustrated because she was late for work.

Complex sentence conjunctions

In complex sentences, dependent clauses are linked to independent clauses with subordinating conjunctions. These are words that couple the two clauses together.

In many cases, these subordinating words come after the independent clause and just before the dependent clause like here:

But that would be extremely embarrassing and suspicious, because during his five years’ service Gregor hadn’t been sick even once.

Many words operate as subordinating conjunctions. They often cluster around concepts like comparisons, time, reason, and conditions.

| Concept | Conjunction |

|---|---|

| Adding information about a person | who, whose, whoever, whom, whomever |

| Adding information about a thing | which, at |

| Condition | if, unless, as long as |

| Contrast | than, rather than, as much as, although, though, even though, while, whereas |

| Introducing reported information | that, whether, how |

| Manner | as |

| Place | where |

| Purpose | so that, only if, even if, provided that |

| Reason | because, since, as |

| Time | now that, when, whenever, as soon as, while, as, once, until, after, before, by the time |

These are just some common subordinating conjunctions. This list is not exhaustive. Dozens and dozens of words and phrases can serve to join the dependent clause to the independent clause.

Complex sentences clauses

In addition to subordinating conjunctions, complex sentences can use three types of clauses, called subordinating clauses:

-

Adjective clause

-

Noun clause

-

Adverb clause

These take the place of adjectives, nouns, and adverbs.

Examples of adjective clauses working as dependent clauses in complex sentences might be:

-

The thief who had taken the pony was found guilty by the jury.

-

The apartment that felt drafty even in spring needed remodeling.

Examples of noun clauses working as dependent clauses in complex sentences might be:

-

Whoever added the eraser to a pencil was very clever.

-

While on vacation, we can do whatever we like.

Examples of adverb clauses working as dependent clauses in complex sentences might be:

-

Although we played well, we lost the baseball game.

-

Whether we liked it or not, we lost by many runs.

Issues writing complex sentences

Kafka was a master of language; he had unwritten permission (from generations of readers) to violate all the “rules” of writing. You do not. When crafting your sentences, be careful to avoid traps with complex sentences.

-

Losing sight of your main idea – Using punctuation, adding subordinating conjunctions, and tacking on streams of dependent clauses, you fall in love with making ever-longer sentences that crush the soul of your intent.

-

Writing run-on sentences – Forgetting to use either punctuation or subordinating conjunctions, you run the dependent clause right into the independent clause.

-

Confusing compound sentences with complex sentences – Compound sentences use one of the seven coordinating conjunctions (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so; FANBOYS) to link independent clauses, while complex sentences use one of many (seemingly countless!) subordinating conjunctions to connect the independent clause with the dependent clause.

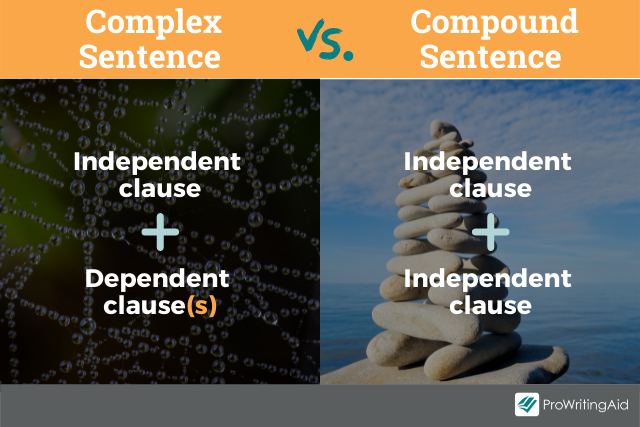

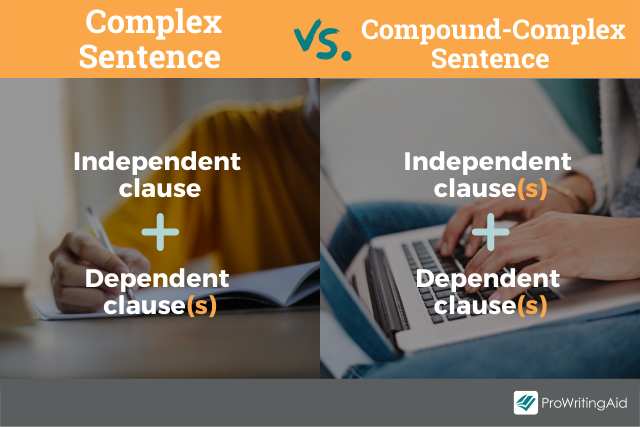

Four types of sentences

In addition to complex sentences, there are three other types of sentences. Here are the four basic sentence types you have in the English language.

-

Simple sentence – One independent clause (one subject, one predicate)

-

Complex sentence – One independent clause, subordinating conjunction, and one or more dependent clauses

-

Compound sentence – Two or more independent clauses, often linked by coordinating conjunctions (FANBOYS)

-

Compound-complex sentence – Two or more independent clauses and at least one dependent clause

The different types of sentences have their own sentence structure.

What is a Complex Sentence?

In English language the sentences are classified into several categories depending on their function, structure etc. There are mainly four types of sentence structures. Each sentence structure uses a specific combination of independent clauses, also called main clauses, and dependent clauses also called subordinate clauses. A complex sentence is one among these four sentence structures. An independent clause can stand alone as a sentence, but a dependent clause even though it has a subject and a verb cannot stand alone as a sentence and must be linked to the independent clause by a subordinate conjunction.

Prerequisites to comprehend this article

For grasping the contents of this article, it’s essential that you have sufficient knowledge of the following grammatical terms:

- Sentences

- Sentence Structure

- Subject

- Simple subject

- Complete subject

- Compound subject

- Predicate

- Simple predicate

- Complete predicate

- Compound predicate

- Object

- Direct object

- Indirect object

- Object to preposition

- Clauses

- Dependent clauseaka Subordinate clause

- Adverb clause aka Adverbial clause

- Adjective clause aka Relative clause

- Noun clause aka Content clause

- Independent clause aka Coordinate clause/Main clause/Principal clause

- Dependent clauseaka Subordinate clause

- Linking words aka Connectives

- Subordinating conjunctions

- Subordinating conjunctions of Comparison

- Subordinating conjunctions of Concession

- Subordinating conjunctions of Contrast

- Subordinating conjunctions of Manner

- Subordinating conjunctions of Place

- Subordinating conjunctions of Reason

- Subordinating conjunctions of Time

- Relative pronouns

- Relative adverbs

- Subordinating conjunctions

- Verb

- Finite verb

- Nonfinite verb

A complex sentence is a sentence that consists of an independent clause and one or more dependent clauses. We use complex sentences to show the relationship between two ideas and indicate which of the two ideas is more important.

Example:

- I opened my eyes. I heard the alarm ringing.

Given above are two simple sentences or in other words two independent clauses. Reading these sentences, we can only guess the relation between the two ideas. But by combining these two ideas into a complex sentence, the idea of these two simple sentences can be made specifically clear as shown below:

- I opened my eyes when I heard the alarm ringing.

Now the idea is noticeably clear. By adding the subordinate conjunction, “when” we transformed the independent clause, ” I heard the alarm ringing”, to a dependent clause it cannot stand alone. It is dependent on the other independent clause, “I heard the alarm ringing”. Not only the meaning of the ideas became clear; but it has also highlighted the importance of the independent clause,” I opened my eyes.”

From the above example, it is evident that simple sentences are not able to express the relationship between two ideas explicitly, and complex sentences are essential for this purpose. The subordinate conjunctions help complex sentences for performing this function.

There are a lot of subordinate conjunctions in English language to show different types of relationships like Time, Place, Concession, Comparison, Condition, Manner, Reason etc. Relative pronoun and relative adverb also connect the clauses and indicate some specific relation. Depending on the context we must choose suitable subordinate conjunctions, so that the relationship between the ideas will be clear. Some of the most common subordinate conjunctions, relative pronoun, and relative adverb are given below, along with examples of complex sentences, so that we may get an idea of how these subordinate conjunctions and other connective words are used.

Examples of complex sentences using different types of subordinate conjunctions:

1. Subordinate conjunction of Time

- After he had a nap, he began to watch a film on the TV.

(In this complex sentence, “After he had a nap “is the dependent clause. This is connected to the independent clause,” he began to watch a film on the TV,” with the subordinate conjunction, “after” that shows the time.)

Some other common subordinate conjunctions which show “time” are:

Before

As long as

As soon as

Till

Since

2. Subordinate conjunction of Place

- This is the school where I studied.

(In this complex sentence, ” where I studied. “is the dependent clause. This is connected to the independent clause,” This is the school.” with the subordinate conjunction, “where”, that shows the place.)

“Wherever” is another commonly used subordinate conjunctions which shows “place”.

3. Subordinate conjunction of Concession

- Though it was raining, she went out.

(In this complex sentence, ” Though it was raining “is the dependent clause. This is connected to the independent clause,” she went out.” with the subordinate conjunction, “though”, that shows concession.)

Some other common subordinate conjunctions which show “concession” are:

Although

Even though

4. Subordinate conjunction of Comparison

- My brother smarter than I am.

(In this complex sentence, ” than I am “is the dependent clause. This is connected to the independent clause,” My brother smarter.” with the subordinate conjunction, “than” that shows comparison.)

Some other common subordinate conjunctions which show “Comparison ” are:

Rather than

As much as

Whereas

5. Subordinate conjunction of Condition

- If my only son goes to USA, I will be lonely.

(In this complex sentence, ” If my only son goes to USA” is the dependent clause. This is connected to the independent clause,”, I will be lonely.” with the subordinate conjunction, ” if”, that shows condition.)

Some other common subordinate conjunctions which show “condition ” are:

Only if

Unless

Provided that

6. Subordinate conjunction of Manner

- The husband and wife looked each other as though they are going to start an altercation.

(In this complex sentence, “as though they are going to start an altercation” is the dependent clause. This is connected to the independent clause, ” I will be lonely ” with the subordinate conjunction, “as though“, that shows manner.)

Some other common subordinate conjunctions which show “manner” are:

As

As if

Note: When we talk about an unreal situation, we use past tense after “as if” and “as though”. Then we can use ” were “with she, he, and I.

Example:

- He treats me as if I were a small child.

7. Subordinate conjunction of Reason

She never scolds her naughty little brother because she loves him so much.

(In this complex sentence, “ because she loves him so much. ” is the dependent clause. This is connected to the independent clause, “She never scolds her naughty little brother ” with the subordinate conjunction, “because “, that shows reason.)

Some other common subordinate conjunctions which show “reason ” are:

Since

As

So that

8. Relative Pronoun

A Relative Pronoun is a pronoun used to connect a subordinate clause (relative clause) to the main clause. Like any other pronoun it has the grammatical function of a noun, and acts as the subject/ object of the relative clause.

Example:

She is the girl who sits next to me in the class

(In this complex sentence, ” who sits next to me in the class ” is the dependent clause (relative clause). This is connected to the independent clause, ” She is the girl” with the Relative Pronoun, “who “, which is the subject of the dependent clause too.)

The five common relative pronouns are:

Who

Whom

which

Whose

That

9. Relative Adverb

A Relative adverb is an adverb used to connect a subordinate clause (relative clause) to the main clause. Like many other adverbs, it modifies a verb.

Example:

I love the village where I was born.

The Relative Adverbs are:

Where

When

Why

Structure, Order and Punctuation of Complex Sentence.

Structure: As already stated above a complex sentence consists of an independent clause/main clause, and one or more dependent clauses/subordinate clauses connected to the main clause using subordinate conjunction. The dependent clause may be adverbial clause, adjective clause/Relative clause, or noun clause.

Order: The order of the clauses in a complex sentence is flexible. We can structure the sentence with either the dependent clause first or the independent clause first without any change in meaning.

Punctuation: When the dependent clause is placed first, it is general followed by a comma. But when the independent clause comes first, usually comma is not required.

Examples:

Before you eat anything with your hand, you must wash your hand thoroughly.

In the above sentence, “before you eat anything with your hand “is a dependent clause. It is an adverbial clause of time. It is at the beginning of the sentence, so it is followed by a comma. The same sentence is rewritten below, in which the independent clause is written first. Then no comma is placed.

You must wash your hand thoroughly before you eat anything with your hand.

The bird that is singing so sweetly is a koel

In the above sentence, “that is singing so sweetly” is the dependent clause. Here it is an adjective/ relative clause.

I know that he is lying.

In the above sentence, “that he is lying” is the dependent clause. Here it is a noun clause as it is the object of the verb, “know”.

A complex sentence can add variety and depth to our writing. From the above article, when we use simple sentence, it is difficult to convey the ideas explicitly. But when we use complex sentences, we can convey cause and effect, progression of events etc., clearly, with the help of subordinate clauses, selecting most suitable subordinate conjunctions.

The

complex sentence is a polypredicative construction built on the

principle of subordination (hypotaxis). In paradigmatic presentation,

the derivational history of the complex sentence is as follows: two

or more base sentences are clausalized and joined into one

construction; one of them performs the role of a matrix in relation

to the others, the insert sentences. The matrix base sentence becomes

the principal clause of the complex sentence and the insert sentences

become its subordinate clauses, e.g.: The team arrived. + It caused a

sensation. à When the team arrived, it caused a sensation.

The

minimal complex sentence includes two clauses: the principal one and

the subordinate one. This is the main type of complex sentences,

first, in terms of frequency, and, second, in terms of its

paradigmatic status, because a complex sentence of any volume can be

analyzed into a combination of two-clause complex sentence units.

The

principal clause positionally dominates the subordinate clause, which

is embedded into it: even if the principal clause is incomplete and

is represented by just one word, the subordinate clauses fill in the

open positions, introduced by the principal clause, in the underlying

simple sentence pattern, e.g.: What you see is what you get — What

you see (the subject) is (the predicate) what you get (the object).

Semantically, the two clauses are interconnected and form a

semantico-syntactic unity: the existence of either of them is

supported by the existence of the other.

The

dominant positional status of the principal clause does not mean that

it expresses the central informative part of the communication: any

clause of a complex sentence can render its rheme or its theme. As in

a simple sentence, in a neutral context the preceding part renders

the starting point of communication, the theme, and the following

part, placed near the end of the sentence, renders the most important

information, the rheme, cf.: What he likes most about her is her

smile. — Her smile is what he likes most about her. In the first

sentence the principal part is rhematic, and in the second sentence

the subordinate clause. Besides the clause-order, as with word-order

in general, there are other means of expressing the correlative

informative value of clauses in complex sentences, such as

intonation, special constructions, emphatic particles and others.

The

informative value of a principal clause may be reduced to the mere

introduction of a subordinate clause; for example, the principal

clause can perform the “phatic” function, i.e. the function of

keeping up the conversation, of maintaining the immediate

communicative connection with the listener, e.g.: I think you are a

great parent; in this sentence, the basic information is rendered by

the rhematic subordinate clause, while the principal clause is

phatic, specifying the speaker’s attitude to the information.

Different

types of complex sentences are distinguished, first of all, on the

basis of their subordinate clause types. Subordinate clauses are

classified on two mutually complementary bases: on the functional

principle and on the categorial principle.

According

to the functional principle, subordinate clauses are divided on the

analogy (though, not identity) of the positional parts of the simple

sentence that underlies the structure of the complex sentence. E.g.:

What you see is what you get. — What you see (the subject, the

subject subordinate clause) is what you get (the object, the object

subordinate clause).

According

to the categorial principle, subordinate clauses are divided by their

inherent nominative properties; there is certain similarity (but,

again, not identity) with the part-of-speech classification of words.

Subordinate clauses can be divided into three categorial-semantic

groups: substantive-nominal, qualification-nominal and adverbial.

Substantive-nominal subordinate clauses name an event as a certain

fact, e.g.: What you do is very important; cf.: What is very

important? Qualification-nominal subordinate clauses name a certain

event, which is referred, as a characteristic to some substance,

represented either by a word or by another clause, e.g.: Where is the

letter that came today?; cf.: What letter? Adverbial subordinate

clauses name a certain event, which is referred, as a characteristic

to another event, to a process or a quality, e.g.: I won’t leave

until you come.

The

two principles of subordinate clause classification are mutually

complementary: the categorial features of clauses go together with

their functional sentence-part features similar to the categorial

features of words going together with their functional

characteristics. Thus, subordinate clauses are to be classified into

three groups: first, clauses of primary nominal positions, including

subject, predicative and object clauses; second, clauses of secondary

nominal positions, including various attributive clauses; and third,

clauses of adverbial positions.

The

classification of clauses is sustained by the subdivision of

functional connective words, which serve as sentence subordinators

(or subordinating clausalizers), transforming the base sentences into

subordinate clauses of various types.

Subordinating

connectors are subdivided into two basic types: pronominal words and

pure conjunctions. Pronominal connective words occupy a notional

position in the derived sentence; for example, some of them replace a

certain antecedent (i.e. a word or phrase to which the connector

refers back) in the principal clause, e.g.: The man whom I met

yesterday surprised me. Pure subordinate conjunctions do not occupy a

notional position in the derived sentence, e.g.: She said that she

would come early. Some connectors are bifunctional, i.e. used both as

conjunctions and as conjunctive substitutes, cf.: She said that she

would come early; Where is the letter that came today?

Semantically,

subordinators (both conjunctions and conjunctive substitutes) are

subdivided in correspondence with the categorial type of the

subordinate clauses which they introduce: there are

substantive-nominal and qualification-nominal clausalizers

(conjunctions and pronominal words), which introduce the event-fact,

and adverbial clausalizers (conjunctions), showing relational

characteristics of events. Some connective words can be used both as

nominal connectors and as adverbial connectors, cf.: Do you know when

they are coming? (What do you know?) – We’ll meet when the new

house is finished (When shall we meet?).

Together

with these, the zero subordinator should be named, whose

polyfunctional status is similar to the status of the subordinator

that, cf.: She said that she would come early. – She said Ø she

would come early; This is the issue that I planned to discuss with

you. – This is the issue Ø I planned to discuss with you.

Clauses

of primary nominal positions, including subject, predicative and

object clauses, are interchangeable with each other, cf.: What you

see is what you get; What you get is what you see; You’ll be

surprised at what you see. The subject clause regularly expresses the

theme of a complex sentence, and the predicative clause regularly

expresses its rheme. The subject clause may express the rheme of the

sentence, if it is introduced by the anticipatory ‘it’, e.g.: It

is true that he stole the jewels. The subject clause in such complex

sentences is at the same time appositive. The status of the object

clause is most obvious in its prepositional introduction (as in the

example above). Sometimes it is mixed with other functional

semantics, determined by the connectors, in particular, with

adverbial relational meanings, e.g.: Do you know when they are

coming? A separate group of object clauses are those presenting the

chunks of speech and mental activity processes, traditionally

discussed under the heading “the rules of reported speech”, e.g.:

She said she would come early; Do you mean you like it?

Clauses

of secondary nominal positions, including various attributive

clauses, fall into two major groups: “descriptive” attributive

clauses and “restrictive” (“limiting”) attributive clauses.

The descriptive attributive clause exposes some characteristic of the

antecedent (i.e. its substantive referent) as such, while the

restrictive attributive clause performs a purely identifying role,

singling out the referent of the antecedent in the situation, cf.: I

know a man who can help us (descriptive attributive clause); This is

the man whom I met yesterday (restrictive attributive clause). Some

descriptive attributive clauses are attributive only in form, but

semantically, they present a new event which somehow continues the

chain of events reflected by the sentence as a whole; these complex

sentences can be easily transformed into compound sentences, e.g.: We

caught a breeze that took us gently up the river. à We caught a

breeze and it took us gently up the river. Appositive clauses, a

subtype of attributive clauses, define or elucidate the meaning of

the substantive antecedent of abstract semantics, represented by such

nouns as ability, advice, attempt, decision, desire, impulse,

promise, proposal, etc, or by an indefinite or demonstrative pronoun,

or by an anticipatory ‘it’, e.g.: I had the impression that she

was badly ill; It was all he could do not to cry; It is true that he

stole the jewels. The unique role of the subjective anticipatory

appositive construction, as has been mentioned, consists in the fact

that it is used as a universal means of rheme identification in the

actual division of the sentence.

Clauses

of adverbial positions make up the most numerous and the most

complicated group of subordinate clauses, reflecting the intricacy of

various relations between events and processes. The following big

groups of adverbial clauses can be distinguished. First, clauses of

time and clauses of place render the semantics of temporal and

spatial localization. Local identification is primarily determined by

subordinators: it may be general, expressed by the conjunctions when

and where, or particularizing, expressed by such conjunctions as

while, since, before, no sooner than, from where, etc., e.g.: I

jumped up when she called; Sit where you like; I won’t leave until

you come. Second, clauses of manner and comparison give a

qualification to the action or event rendered by the principal

clause, e.g.: Profits are higher than they were last year; Her lips

moved soundlessly, as if she were rehearsing. The syntactic semantics

of manner is expressed by subordinate appositive clauses introduced

by phrases with the broad-meaning words way and manner, e.g.: George

writes the way his father did. Third, the most numerous group,

adverbial clauses of different circumstantial semantics includes

“classical” subordinate clauses of attendant event, condition,

cause (reason), result (consequence), concession, and purpose. E.g.:

I am tired because I have worked all day; He spoke loudly so that all

could hear him; If we start off now, we’ll arrive there by dinner;

Even if the fault is all his, I must find a way to help him; He was

so embarrassed that he could hardly understand her; etc. Cases of

various ‘transferred’ and mixed syntactic semantics are also

common in this group of clauses; e.g.: Whatever happens, she won’t

have it her own way; the subordinate clause expresses circumstantial

(concessive) semantics mixed with non-circumstantial

(substantive-nominal) semantics. Fourth, a separate group of

adverbial clauses is formed by subordinate clauses which function as

parenthetical enclosures, inserted into composite syntactic

constructions by a loose connection. Parenthetical predicative

insertions can be either subordinative or coordinative, exposed by

either a subordinating connector or a coordinative connector (cf.:

inner cumulative connections in equipotent and dominational phrases;

see Unit 19), e.g.: As far as I remember, the man was very much

surprised to see me there; They used to be, and this is no longer a

secret, very close friends. Semantically, parenthetical clauses may

be of two types: “introductory”, expressing different modal

meanings (as in the first example above), and “deviational”,

expressing commenting insertions of varied semantic character (the

second example above).

As

the classification shows, the only notional position the subordinate

clause can not occupy is the position of the predicate; this fact

stresses once again the unique function of the predicate as the

organizing centre of the sentenc

The

clauses of a complex sentence can be connected with one another more

or less closely. The degree (intensity) of syntactic closeness

between the clauses reflects the degree of mutual dependence of their

proposemic content. For example, the primary subordinate clauses, the

subject clause and the predicative clause, are so closely connected

with the principal clause that without them the principal clause

cannot exist as a syntactic unit. The loose connections between the

principal clause and the parenthetical enclosure make it possible to

segregate the principal clause as an independent syntactic

construction. Thus, all types of subordinative clausal connections

are syntactically either obligatory or optional.

This

distinction was used by the Russian linguist N. S. Pospelov to

introduce another classification of complex sentences: he defined

complex sentences with obligatory subordinate clauses as “one-member

sentences” and complex sentences with optional subordinate clauses

as “two-member sentences”. These two types of complex sentences

can also be described as “monolithic” and “segregative”

sentence structures correspondingly. The following complex sentences

are syntactically monolithic: first, complex sentences with subject

and predicative clauses, e.g.: What the telegram said was clear (*…

was clear would be semantically and constructionally deficient); The

telegram was what I expected from you (*The telegram was…); second,

complex sentences in which the subordinate clauses perform the

functions of complements, required by the obligatory valency of the

predicate (usually, object clauses and adverbial clauses), e.g.: Tell

me what you know about it (cf.: *Tell me…); Put the pen where

you’ve taken it from; third, complex sentences with correlative

connections, for example, with double connectors, e.g.: The more he

thought about it, the more he worried; complex sentences with

restrictive attributive clauses are monolythic, because they are

based on a correlation scheme too, e.g.: It was the kind of book that

all children admire; finally, the fourth type of monolithic complex

sentences is formed by complex sentences with the subordinate clause

in preposition to the principal clause, e.g.: As far as I remember,

the man was very much surprised to see me there (cf.: *As far as I

remember…); Even if the fault is all his, I must find a way to help

him.

Segregative

complex sentences are those with most of the adverbial clauses,

parenthetical clauses and descriptive attributive clauses in

postposition to the principal clause, e.g.: The man was very much

surprised to see me there, as far as I remember (cf.: The man was

very much surprised to see me); She wore a hat which was decorated

with flowers (сf.: She wore a hat).

More

than two clauses may be combined in one complex sentence. Subordinate

clauses may be arranged by parallel or consecutive subordination.

Subordinate clauses immediately referring to one principal clause are

subordinated “in parallel’ or “co-subordinated”. Parallel

subordination may be both homogeneous and heterogeneous: in

homogeneous parallel constructions, the subordinate clauses perform

similar functions, they are connected with each other coordinatively

and depend on the same element in the principal clause (or, the

principal clause in general), e.g.: He said that it was his business

and that I’d better stay off it; in heterogeneous parallel

constructions, the subordinate clauses mostly refer to different

elements in the principal clause, e.g.: The man whom I saw yesterday

said that it was his business. Consecutive subordinative

constructions are formed when one clause is subordinated to another

in a string of clauses, e.g.: I don’t know why she said that she

couldn’t come at the time that I suggested. There are three

consecutively subordinated clauses in this sentence; they form a

hierarchy of three levels of subordination. This figure shows the

so-called depth of subordination perspective, one of the essential

syntactic characteristics of the complex sentence. In the previous

examples, the depth of subordination perspective can be estimated as

1.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

There are four categories of sentences: simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex. Each type of sentence has its own essential ingredients.

For the complex sentence, those ingredients are an independent clause and at least one dependent clause.

As you continue reading, I’ll show you how you can mix those two ingredients (the independent and dependent clauses) in different ways to whip up complex sentences.

What are Complex Sentences?

A complex sentence is a sentence that contains an independent clause and a dependent clause. Here’s an example of a complex sentence:

Because my pizza was cold, I put it in the microwave.

This sentence has an independent clause (“I put it in the microwave”) and a dependent clause (“Because my pizza was cold”) so it’s a complex sentence.

Before we get further into examples of complex sentences, let’s do a quick refresher on clauses.

What are Independent and Dependent Clauses?

A clause is a group of words that contains a subject and a verb.

The difference between independent and dependent clauses is this: an independent clause can stand alone as a sentence and a dependent clause cannot.

What Is an Independent Clause?

An independent clause is a simple sentence. Those two terms, independent clause and simple sentence, mean the same thing.

An independent clause includes a subject and a verb, and expresses a complete thought—just like a simple sentence does.

An independent clause makes sense on its own. In these examples, the subjects and verbs are in bold.

- I had a rough start to my birthday today.

- I slept through my alarm.

- My boss was angry about my subsequent late arrival.

- Someone stole my lunch from the office fridge!

- No one even brought a cake to celebrate my birthday.

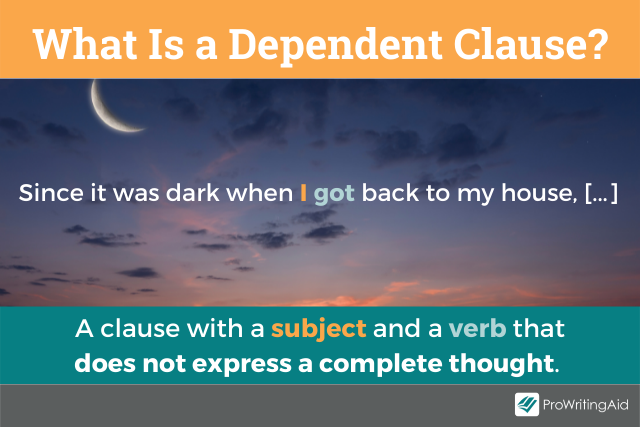

What Is A Dependent Clause?

A dependent clause also contains a subject and a verb, but does not express a complete thought.

It depends on connection to an independent clause to make sense. Another name for a dependent clause is subordinate clause.

A dependent clause often starts with a subordinating conjunction, a word which establishes a relationship between the information in the subordinating clause and the independent clause it is connected to.

These relationships include cause/effect, time, place, condition, comparison, and concession.

In these examples of dependent clauses, the subjects and verbs are in bold, and the subordinating conjunctions are highlighted.

- Because I left work late

- Since it was dark when I got back to my house

- While I was careful to observe my surroundings

- As soon as I opened the door

Did you notice the difference between these examples and the independent clauses?

With the independent clauses, we know what’s happening by the end of the sentence. This poor person, let’s call her Joanne, has had a lousy day.

With the dependent clauses, we are “left hanging,” and it seems as if Joanne’s day may have gotten even worse!

I wish we could find out if she at least got home safely on her forgotten birthday!

Actually, I think I have a solution. We can use those dependent clauses as one of the ingredients in our about-to-be-created complex sentences. Then we’ll get the complete story.

How to Create Complex Sentences

Complex sentences include an independent and at least one dependent clause.

Though the dependent clause cannot stand alone as a sentence, it does add to the meaning of the independent clause.

In a complex sentence, the independent and dependent clauses can be put together in a variety of ways. For example:

Dependent followed by independent: In this format, put a comma after the dependent clause.

- Because I left work late, I just wanted to get home and relax.

(The dependent clause tells us why Joanne wanted to get home)

Independent followed by dependent: In this format, no comma is needed.

- I was feeling extra stressed and tired since it was dark when I got back to my house.

(The dependent clause tells us why Joanne was extra stressed and tired)

Dependent both before and after independent: In this format, a comma is required after the first dependent clause.

- While I was careful to observe my surroundings, I almost tripped walking up to my door since I couldn’t see in the darkness.

(The dependent clause establishes a relationship of contrast with the independent clause)

Two dependents followed by an independent clause: In this format, put a comma after each dependent clause.

- As soon as I opened the door, and after I had kicked off my shoes, I had a sense that someone was in my house.

(The dependent clauses tell us when Joanne experienced that sense)

Do you see how those ingredients work together to create a complete thought?

While the independent clause doesn’t need the dependent clause to survive as a sentence, the dependent clause adds to the meaning of that dependent clause.

Here are a couple more examples to let you know what ultimately happened at the end of Joanne’s lousy day.

Take notice of their respective structures—the order of the independent (IC) and dependent clauses (DC), and where the commas (if needed) appear.

- I continued to walk down the hallway even though I was quite scared. (IC-DC)

- After letting out what I thought was an intimidating yell, I was greeted by five of my close friends yelling “Surprise!” (DC, IC)

- We all had a good laugh because of my lame attempt to scare away the “bad guys.” (IC-DC)

- Since my friends gifted me with a lovely surprise and chocolate cake, even though my birthday started out terribly, it ended in the best way possible. (DC, DC, IC)

Happy Birthday Joanne! To celebrate, I’ll show you one more way to structure a complex sentence.

Using A Dependent Clause to Interrupt an Independent Clause in a Complex Sentence

All the examples so far have shown complex sentences that include an independent clause and a dependent clause placed one after the other in one order or another.

But sometimes, a dependent clause can be put right in the middle of an independent clause. In this format, the dependent clause should be surrounded with commas.

In these examples, the dependent clause is in bold. If you remove it from the sentence, you’re left with an independent clause.

- The dog, because he was so friendly, was adopted quickly.

- The meal, even though it was exceptional, was expensive.

- The students, whatever their skill levels, all showed improvement.

What’s The Difference Between Complex and Compound Sentences?

While a complex sentence includes an independent and at least one dependent clause, a compound sentence includes two independent clauses.

In a compound sentence, the independent clauses can either be joined with a semicolon or with a comma + coordinating conjunction combination.

Examples of Compound Sentences Using Semicolons

A semicolon has the combined power of both a period and a comma. It is strong enough to create a stop—a distinction—between two independent clauses, but is more gentle than a period.

The semicolon doesn’t create a full stop; it maintains a connection between the clauses, which is where you see its comma function.

You would use a semicolon when your independent clauses are closely related and you don’t want to create a full stop between them.

- I took a walk today; the fresh autumn air was invigorating.

- The leaves created a rainbow of colors; the foliage was enchanting.

- I returned home feeling both calm and energized; the beauty of nature is truly special.

Examples of Compound Sentences Using Coordinating Conjunctions + Comma

Coordinating conjunctions connect words, phrases, or clauses that are of equal value, such as two independent clauses.

Each of those clauses can stand on its own as a sentence.

The seven coordinating conjunctions are and, but, or, nor, so, yet, for.

A coordinating conjunction + comma combination has the power to connect—to hold together—two independent clauses.

A comma alone isn’t enough and produces an error called a comma splice.

In each of the following examples, the coordinating conjunction + comma combination is in bold.

- I ordered a salad ,but I really wanted a big bowl of spaghetti.

- The spaghetti smelled so good ,and I can’t stop thinking about it.

- I’m going back to that restaurant ,so I can order what I really want.

A compound sentence, unlike a complex sentence, only includes independent clauses. It does not include any dependent clauses.

What’s The Difference Between Complex and Compound-Complex Sentences?

The compound-complex sentence includes at least two independent clauses (remember: the complex sentence only has one) and one or more dependent clauses.

Examples of Compound-Complex Sentences

In these examples, the independent clauses are in bold.

- After I ordered my spaghetti, I felt happy, and I couldn’t wait to sit down and eat!

- I think I could eat pasta every day, even though I probably shouldn’t, and I would enjoy every bite.

- Because I want to eat healthy and since I’ve satisfied my craving, I’ll get back to salad tomorrow, but I’ll probably be back for more spaghetti before too long!

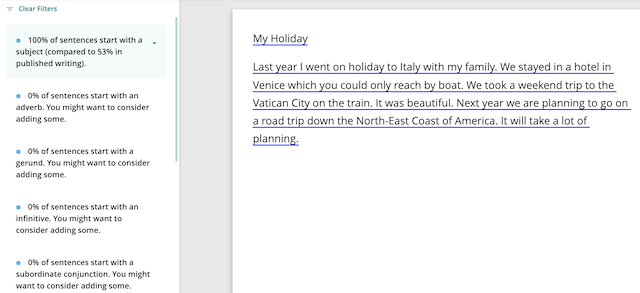

How Complex Sentences Help Your Writing

Adding variety to your sentence structure is important to good writing. If you rely too much on one style of sentence, your work will become monotonous and take on a droning effect. No one wants that!

By understanding how complex sentences work, you can add them to your work with confidence.

And if you need a boost for your confidence while you’re still practicing, run your work through ProWritingAid’s Sentence Structure Report.

It will help you see where your sentence structure may be repetitive and offer suggestions for how to add some variety.

Although the example below provides some really interesting details, the structure is repetitive, in fact, all the sentences start with a subject.

Including complex and varied sentence structures is essential if you want to keep your reader’s attention.

Try the Sentence Structure report with a free ProWritingAid account.

As a writer, it’s important to understand the tools of your trade. Sentence structure is one of those tools.

Take the time to notice how other writers use simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences in their work.

Observe and learn as you read and then be inspired!

Are you prepared to write your novel? Download this free book now:

The Novel-Writing Training Plan

So you are ready to write your novel. Excellent. But are you prepared? The last thing you want when you sit down to write your first draft is to lose momentum.

This guide helps you work out your narrative arc, plan out your key plot points, flesh out your characters, and begin to build your world.