What is the scientific word for sound?

Acoustics is the interdisciplinary science that deals with the study of mechanical waves in gases, liquids, and solids including vibration, sound, ultrasound, and infrasound.

What are the 3 types of sound?

Sound waves fall into three categories: longitudinal waves, mechanical waves, and pressure waves.

What is a sound wave called?

A sound wave is called a longitudinal wave because compressions and rarefactions in the air produce it. The air particles vibrate parallel to the direction of propagation.

What is a sound wave in physics?

Sound is a mechanical wave that results from the back and forth vibration of the particles of the medium through which the sound wave is moving. The motion of the particles is parallel (and anti-parallel) to the direction of the energy transport. This is what characterizes sound waves in air as longitudinal waves.

What are the 7 properties of sound?

Rammdustries LLC is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

- 7 Characteristics Of Sound, and Why You Need To Know Them.

- Frequency.

- Amplitude.

- Timbre.

- Envelope.

- Velocity.

- Wavelength.

- Phase.

What is sound and its types?

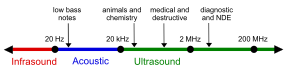

What are the types of sound? There are two types of sound, Audible and Inaudible. Inaudible sounds are sounds that the human ear cannot detect. The human ear hears frequencies between 20 Hz and 20 KHz. Sounds that are below 20 Hz frequency are called Infrasonic Sounds.

What are the 2 types of sound?

Sound has two basic forms: acoustic energy and mechanical energy. Each type of sound has to be tackled in their own way. Acoustic energy or sound is what we experience every day. It is in fact vibration of air (sound waves) which is transformed by the tympanic membrane in the ear of human to audible sounds.

What are the four types of sound?

Sound can be of different types—soft, loud, pleasant, unpleasant, musical, audible (can be heard), inaudible (cannot be heard), etc. Some sounds may fall into more than one category. For instance, the sound produced when an aeroplane takes off is both loud and unpleasant.

How do we make sound?

Sounds are made when objects vibrate. The vibration makes the air around the object vibrate and the air vibrations enter your ear. You hear them as sounds. You cannot always see the vibrations, but if something is making a sound, some part of it is always vibrating.

What is physical noise?

Physical noise is any sort of outside communication effort by someone or something, for example a loud noise that interrupts or distracts you. Semantic noise is the interference during the construction of a message, as when your professor uses unfamiliar words.

What is noise explain?

Noise is unwanted sound considered unpleasant, loud or disruptive to hearing. In experimental sciences, noise can refer to any random fluctuations of data that hinders perception of a signal.

How many English sounds do we have?

44

What are the 20 vowel sounds?

English has 20 vowel sounds. Short vowels in the IPA are /ɪ/-pit, /e/-pet, /æ/-pat, /ʌ/-cut, /ʊ/-put, /ɒ/-dog, /ə/-about. Long vowels in the IPA are /i:/-week, /ɑ:/-hard,/ɔ:/-fork,/ɜ:/-heard, /u:/-boot.

What are the 44 sounds?

Note that the 44 sounds (phonemes) have multiple spellings (graphemes) and only the most common ones have been provided in this summary.

- 20 Vowel Sounds. 6 Short Vowels. a. e. i. o. u. oo u. cat. leg. sit. top. rub. book. put. 5 Long Vowels. ai ay. ee ea. ie igh. oe ow. oo ue. paid. tray. bee. beat. pie. high. toe. flow. moon.

- 24 Consonant Sounds.

What are the 12 pure vowel sounds?

There are 12 pure vowels or monophthongs in English – /i:/, /ɪ/, /ʊ/, /u:/, /e/, /ə/, /ɜ:/, /ɔ:/, /æ/, /ʌ/, /ɑ:/ and /ɒ/. The monophthongs can be really contrasted along with diphthongs in which the vowel quality changes. It will have the same syllables and hiatus with two vowels.

What are the 11 vowel sounds in English?

These letters are vowels in English: A, E, I, O, U, and sometimes Y. It is said that Y is “sometimes” a vowel, because the letter Y represents both vowel and consonant sounds. In the words cry, sky, fly, my and why, letter Y represents the vowel sound /aɪ/.

What are the 8 diphthong sounds?

Why Wait? The Top 8 Common English Diphthong Sounds with Examples

- /aʊ/ as in “Town”

- /aɪ/ as in “Light”

- /eɪ/ as in “Play”

- /eə/ as in “Pair”

- /ɪə/ as in “Deer”

- /oʊ/ as in “Slow”

- /ɔɪ/ as in “Toy”

- /ʊə/ as in “Sure”

What are the 7 vowels?

In writing systems based on the Latin alphabet, the letters A, E, I, O, U, Y, W and sometimes others can all be used to represent vowels.

Which word has all 5 vowels?

Eunoia, at six letters long, is the shortest word in the English language that contains all five main vowels. Seven letter words with this property include adoulie, douleia, eucosia, eulogia, eunomia, eutopia, miaoued, moineau, sequoia, and suoidea.

Why is it called a vowel?

The word vowel ultimately comes from the Latin vox, meaning “voice.” It’s the source of voice and such words as vocal and vociferate. Consonant literally means “with sound,” from the Latin con- (“with”) and sonare (“to sound”). This verb yields, that’s right, the word sound and many others, like sonic and resonant.

What are the 8 vowels?

A, E, I, O, U and sometimes Y are the letters we define as vowels, but vowels can also be defined as speech sounds. While we have six letters we define as vowels, there are, in English, many more vowel sounds than that. For example consider the word pairs cat and car, or cook and kook.

What is the most used letter?

The top ten most common letters in the Concise Oxford English Dictionary, and the percentage of words they appear in, are:

- E – 11.1607%

- A – 8.4966%

- R – 7.5809%

- I – 7.5448%

- O – 7.1635%

- T – 6.9509%

- N – 6.6544%

- S – 5.7351%

Is 8 a long vowel?

The combination of the vowels “e” and “i” can result in the long a sound, e.g., eight, sleigh, neigh and weigh.

What is the most used consonant?

Three of the most common consonants of the English language are R, S and T. Every answer today is a word, name or phrase that contains each of the letters R, S and T exactly once, along with any number of vowels.

What is the longest word in English?

pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis

What is the least used word?

Least Common English Words

- abate: reduce or lesson.

- abdicate: give up a position.

- aberration: something unusual, different from the norm.

- abhor: to really hate.

- abstain: to refrain from doing something.

- adversity: hardship, misfortune.

- aesthetic: pertaining to beauty.

- amicable: agreeable.

What is the most used word in the world?

The

What are the 12 powerful words?

12 Powerful Words

- Trace – list in steps.

- Analyze – break apart.

- Infer – read between the lines.

- Evaluate – judge.

- Formulate – create.

- Describe – tell all about.

- Support – back up with details.

- Explain – tell how.

What is the oldest word?

Mother, bark and spit are some of the oldest known words, say researchers. Continue reading → Mother, bark and spit are just three of 23 words that researchers believe date back 15,000 years, making them the oldest known words.

- Top Definitions

- Quiz

- Related Content

- Examples

- British

- Scientific

- Idioms And Phrases

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

noun

the sensation produced by stimulation of the organs of hearing by vibrations transmitted through the air or other medium.

mechanical vibrations transmitted through an elastic medium, traveling in air at a speed of approximately 1,087 feet (331 meters) per second at sea level.

the particular auditory effect produced by a given cause: the sound of music.

any auditory effect; any audible vibrational disturbance: all kinds of sounds.

a noise, vocal utterance, musical tone, or the like: the sounds from the next room.

a distinctive, characteristic, or recognizable musical style, as from a particular performer, orchestra, or type of arrangement: the big-band sound.

Phonetics.

- speech sound.

- the audible result of an utterance or portion of an utterance: the s-sound in “slight”;the sound of m in “mere.”

the auditory effect of sound waves as transmitted or recorded by a particular system of sound reproduction: the sound of a stereophonic recording.

the quality of an event, letter, etc., as it affects a person: This report has a bad sound.

the distance within which the noise of something may be heard.

mere noise, without meaning: all sound and fury.

Archaic. a report or rumor; news; tidings.

verb (used without object)

to make or emit a sound.

to give forth a sound as a call or summons: The bugle sounded as the troops advanced.

to be heard, as a sound.

to convey a certain impression when heard or read: to sound strange.

to give a specific sound: to sound loud.

to give the appearance of being; seem: The report sounds true.

Law. to have as its basis or foundation (usually followed by in): His action sounds in contract.

verb (used with object)

to cause to make or emit a sound: to sound a bell.

to give forth (a sound): The oboe sounded an A.

to announce, order, or direct by or as by a sound: The bugle sounded retreat.His speech sounded a warning to aggressor nations.

to utter audibly, pronounce, or express: to sound each letter.

to examine by percussion or auscultation: to sound a patient’s chest.

Verb Phrases

sound off, Informal.

- to call out one’s name, as at military roll call.

- to speak freely or frankly, especially to complain in such a manner.

- to exaggerate; boast: Has he been sounding off about his golf game again?

QUIZ

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE COMMON GRAMMAR DEBATES?

There are grammar debates that never die; and the ones highlighted in the questions in this quiz are sure to rile everyone up once again. Do you know how to answer the questions that cause some of the greatest grammar debates?

Which sentence is correct?

Idioms about sound

(that) sounds good (to me), (used when accepting a suggestion) I agree; yes; OK: “Shall we meet at my place at 3 tomorrow, and talk about it in more detail then?” “Sounds good.”

Origin of sound

1

First recorded in 1250–1300; (noun) Middle English soun, from Anglo-French (Old French son ), from Latin sonus; (verb) Middle English sounen, from Old French suner, from Latin sonāre, derivative of sonus

synonym study for sound

1. Sound, noise, tone refer to something heard. Sound and noise are often used interchangeably for anything perceived by means of hearing. Sound, however, is more general in application, being used for anything within earshot: the sound of running water. Noise, caused by irregular vibrations, is more properly applied to a loud, discordant, or unpleasant sound: the noise of shouting. Tone is applied to a musical sound having a certain quality, resonance, and pitch.

OTHER WORDS FROM sound

sound·a·ble, adjectiveun·sound·a·ble, adjective

Words nearby sound

soul music, soul-searching, soul sister, Soult, sou marqué, sound, soundalike, sound-and-light, sound-and-light show, sound as a bell, sound barrier

Other definitions for sound (2 of 5)

adjective, sound·er, sound·est.

free from injury, damage, defect, disease, etc.; in good condition; healthy; robust: a sound heart;a sound mind.

financially strong, secure, or reliable: a sound business;sound investments.

competent, sensible, or valid: sound judgment.

having no defect as to truth, justice, wisdom, or reason: sound advice.

following in a systematic pattern without any apparent defect in logic: sound reasoning.

of substantial or enduring character: sound moral values.

uninterrupted and untroubled; deep; sound sleep.

vigorous, thorough, or severe: a sound thrashing.

free from moral defect or weakness; upright, honest, or good; honorable; loyal.

having no legal defect: a sound title to property.

theologically correct or orthodox, as doctrines or a theologian.

adverb

Origin of sound

2

First recorded in 1150–1200; Middle English sund, Old English gesund (see y-); cognate with Dutch gezond, German gesund

OTHER WORDS FROM sound

sound·ly, adverbsound·ness, noun

Other definitions for sound (3 of 5)

verb (used with object)

to measure or try the depth of (water, a deep hole, etc.) by letting down a lead or plummet at the end of a line, or by some equivalent means.

to measure (depth) in such a manner, as at sea.

to examine or test (the bottom, as of the sea or a deep hole) with a lead that brings up adhering bits of matter.

to examine or investigate; seek to fathom or ascertain: to sound a person’s views.

to seek to elicit the views or sentiments of (a person) by indirect inquiries, suggestive allusions, etc. (often followed by out): Why not sound him out about working for us?

Surgery. to examine, as the urinary bladder, with a sound.

verb (used without object)

to use the lead and line or some other device for measuring depth, as at sea.

to go down or touch bottom, as a lead.

to plunge downward or dive, as a whale.

to make investigation; seek information, especially by indirect inquiries.

noun

Surgery. a long, slender instrument for sounding or exploring body cavities or canals.

Origin of sound

3

First recorded in 1300–50; Middle English sounden, from Old French sonder “to plumb,” derivative of sonde “sounding line,” of unknown origin

OTHER WORDS FROM sound

sound·a·ble, adjective

Other definitions for sound (4 of 5)

noun

a relatively narrow passage of water between larger bodies of water or between the mainland and an island: Long Island Sound.

an inlet, arm, or recessed portion of the sea: Puget Sound.

the air bladder of a fish.

Origin of sound

4

First recorded before 900; Middle English; Old English sund “act of swimming”; akin to swim

Other definitions for sound (5 of 5)

noun

The Sound, a strait between southwestern Sweden and Zealand, connecting the Kattegat and the Baltic. 87 miles (140 km) long; 3–30 miles (5–48 km) wide.

Danish Ø·re·sund [Danish œ—ruh-soon] /Danish ˈœ rəˌsʊn/ . Swedish Ö·re·sund [Swedish œ—ruh-soond] /Swedish ˈœ rəˌsʊnd/ .

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

Words related to sound

flawless, intact, robust, safe, sane, solid, stable, sturdy, thorough, vibrant, vigorous, accurate, correct, fair, judicious, precise, proper, prudent, rational, reliable

How to use sound in a sentence

-

If that sounds like you, don’t feel like you need to suffer to see gains.

-

In many cases, this will come as no surprise—we use many apps precisely because they can take pictures or record a sound.

-

The content should not be stuffed, like in the old days of SEO, it should rather be a natural-sounding copy written in an informative style.

-

Now researchers think the sounds stop queens from fighting to the death.

-

For one thing, it sounds like the App Store will now support game-streaming services like Microsoft’s xCloud and Google’s Stadia.

-

Again, the difference can seem subtle and sound more like splitting hairs, but the difference is important.

-

And it must make sure that the platform of debate where we can freely exchange ideas is safe and sound.

-

“Gronkowski” itself never manages to sound more erotic than the name of a hearty Polish stew or a D-list WWE performer.

-

Girls in Peacetime Want to Dance is a different sound for you.

-

“You can imagine the sound of that gun on a Bronx street,” Chief of Detectives Robert Boyce says.

-

Sol laughed out of his whiskers, with a big, loose-rolling sound, and sat on the porch without waiting to be asked.

-

She was flushed and felt intoxicated with the sound of her own voice and the unaccustomed taste of candor.

-

Bells were pealing and tolling in all directions, and the air was filled with the sound of distant shouts and cries.

-

It will be remembered that pitch depends upon the rapidity of the sound waves or vibrations.

-

Miss Christabel blushed furiously and emitted a sound half between a laugh and a scream.

British Dictionary definitions for sound (1 of 5)

noun

- a periodic disturbance in the pressure or density of a fluid or in the elastic strain of a solid, produced by a vibrating object. It has a velocity in air at sea level at 0°C of 331 metres per second (741 miles per hour) and travels as longitudinal waves

- (as modifier)a sound wave

(modifier) of or relating to radio as distinguished from televisionsound broadcasting; sound radio

the sensation produced by such a periodic disturbance in the organs of hearing

anything that can be heard

a particular instance, quality, or type of soundthe sound of running water

volume or quality of sounda radio with poor sound

the area or distance over which something can be heardto be born within the sound of Big Ben

the impression or implication of somethingI don’t like the sound of that

phonetics the auditory effect produced by a specific articulation or set of related articulations

(often plural) slang music, esp rock, jazz, or pop

verb

to cause (something, such as an instrument) to make a sound or (of an instrument, etc) to emit a sound

to announce or be announced by a soundto sound the alarm

(intr) (of a sound) to be heard

(intr) to resonate with a certain quality or intensityto sound loud

(copula) to give the impression of being as specified when read, heard, etcto sound reasonable

(tr) to pronounce distinctly or audiblyto sound one’s consonants

(intr usually foll by in) law to have the essential quality or nature (of)an action sounding in damages

Derived forms of sound

soundable, adjective

Word Origin for sound

C13: from Old French soner to make a sound, from Latin sonāre, from sonus a sound

British Dictionary definitions for sound (2 of 5)

adjective

free from damage, injury, decay, etc

firm; solid; substantiala sound basis

financially safe or stablea sound investment

showing good judgment or reasoning; sensible; wisesound advice

valid, logical, or justifiablea sound argument

holding approved beliefs; ethically correct; upright; honest

(of sleep) deep; peaceful; unbroken

thorough; completea sound examination

British informal excellent

law (of a title, etc) free from defect; legally valid

constituting a valid and justifiable application of correct principles; orthodoxsound theology

logic

- (of a deductive argument) valid

- (of an inductive argument) according with whatever principles ensure the high probability of the truth of the conclusion given the truth of the premises

- another word for consistent (def. 5b)

adverb

soundly; deeply: now archaic except when applied to sleep

Derived forms of sound

soundly, adverbsoundness, noun

Word Origin for sound

Old English sund; related to Old Saxon gisund, Old High German gisunt

British Dictionary definitions for sound (3 of 5)

verb

to measure the depth of (a well, the sea, etc) by lowering a plumb line, by sonar, etc

to seek to discover (someone’s views, etc), as by questioning

(intr) (of a whale, etc) to dive downwards swiftly and deeply

med

- to probe or explore (a bodily cavity or passage) by means of a sound

- to examine (a patient) by means of percussion and auscultation

noun

med an instrument for insertion into a bodily cavity or passage to dilate strictures, dislodge foreign material, etc

Word Origin for sound

C14: from Old French sonder, from sonde sounding line, probably of Germanic origin; related to Old English sundgyrd sounding pole, Old Norse sund strait, sound 4; see swim

British Dictionary definitions for sound (4 of 5)

noun

a relatively narrow channel between two larger areas of sea or between an island and the mainland

an inlet or deep bay of the sea

the air bladder of a fish

Word Origin for sound

Old English sund swimming, narrow sea; related to Middle Low German sunt strait; see sound ³

British Dictionary definitions for sound (5 of 5)

noun

the Sound a strait between SW Sweden and Zealand (Denmark), linking the Kattegat with the Baltic: busy shipping lane; spanned by a bridge in 2000. Length of the strait: 113 km (70 miles). Narrowest point: 5 km (3 miles)Danish name: Øresund Swedish name: Öresund

Collins English Dictionary — Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition

© William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins

Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Scientific definitions for sound (1 of 2)

A type of longitudinal wave that originates as the vibration of a medium (such as a person’s vocal cords or a guitar string) and travels through gases, liquids, and elastic solids as variations of pressure and density. The loudness of a sound perceived by the ear depends on the amplitude of the sound wave and is measured in decibels, while its pitch depends on its frequency, measured in hertz.

The sensation produced in the organs of hearing by waves of this type. See Note at ultrasound.

Scientific definitions for sound (2 of 2)

A long, wide inlet of the ocean, often parallel to the coast. Long Island Sound, between Long Island and the coast of New England, is an example.

A long body of water, wider than a strait, that connects larger bodies of water.

The American Heritage® Science Dictionary

Copyright © 2011. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Other Idioms and Phrases with sound

In addition to the idioms beginning with sound

- sound as a bell

- sound bite

- sound off

- sound out

The American Heritage® Idioms Dictionary

Copyright © 2002, 2001, 1995 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

This article is about audible acoustic waves. For other uses, see Sound (disambiguation).

A drum produces sound via a vibrating membrane

In physics, sound is a vibration that propagates as an acoustic wave, through a transmission medium such as a gas, liquid or solid.

In human physiology and psychology, sound is the reception of such waves and their perception by the brain.[1] Only acoustic waves that have frequencies lying between about 20 Hz and 20 kHz, the audio frequency range, elicit an auditory percept in humans. In air at atmospheric pressure, these represent sound waves with wavelengths of 17 meters (56 ft) to 1.7 centimeters (0.67 in). Sound waves above 20 kHz are known as ultrasound and are not audible to humans. Sound waves below 20 Hz are known as infrasound. Different animal species have varying hearing ranges.

Acoustics

Acoustics is the interdisciplinary science that deals with the study of mechanical waves in gasses, liquids, and solids including vibration, sound, ultrasound, and infrasound. A scientist who works in the field of acoustics is an acoustician, while someone working in the field of acoustical engineering may be called an acoustical engineer.[2] An audio engineer, on the other hand, is concerned with the recording, manipulation, mixing, and reproduction of sound.

Applications of acoustics are found in almost all aspects of modern society, subdisciplines include aeroacoustics, audio signal processing, architectural acoustics, bioacoustics, electro-acoustics, environmental noise, musical acoustics, noise control, psychoacoustics, speech, ultrasound, underwater acoustics, and vibration.[3]

Definition

Sound is defined as «(a) Oscillation in pressure, stress, particle displacement, particle velocity, etc., propagated in a medium with internal forces (e.g., elastic or viscous), or the superposition of such propagated oscillation. (b) Auditory sensation evoked by the oscillation described in (a).»[4] Sound can be viewed as a wave motion in air or other elastic media. In this case, sound is a stimulus. Sound can also be viewed as an excitation of the hearing mechanism that results in the perception of sound. In this case, sound is a sensation.

Physics

Experiment using two tuning forks oscillating usually at the same frequency. One of the forks is being hit with a rubberized mallet. Although only the first tuning fork has been hit, the second fork is visibly excited due to the oscillation caused by the periodic change in the pressure and density of the air by hitting the other fork, creating an acoustic resonance between the forks. However, if we place a piece of metal on a prong, we see that the effect dampens, and the excitations become less and less pronounced as resonance isn’t achieved as effectively.

Sound can propagate through a medium such as air, water and solids as longitudinal waves and also as a transverse wave in solids. The sound waves are generated by a sound source, such as the vibrating diaphragm of a stereo speaker. The sound source creates vibrations in the surrounding medium. As the source continues to vibrate the medium, the vibrations propagate away from the source at the speed of sound, thus forming the sound wave. At a fixed distance from the source, the pressure, velocity, and displacement of the medium vary in time. At an instant in time, the pressure, velocity, and displacement vary in space. Note that the particles of the medium do not travel with the sound wave. This is intuitively obvious for a solid, and the same is true for liquids and gases (that is, the vibrations of particles in the gas or liquid transport the vibrations, while the average position of the particles over time does not change). During propagation, waves can be reflected, refracted, or attenuated by the medium.[5]

The behavior of sound propagation is generally affected by three things:

- A complex relationship between the density and pressure of the medium. This relationship, affected by temperature, determines the speed of sound within the medium.

- Motion of the medium itself. If the medium is moving, this movement may increase or decrease the absolute speed of the sound wave depending on the direction of the movement. For example, sound moving through wind will have its speed of propagation increased by the speed of the wind if the sound and wind are moving in the same direction. If the sound and wind are moving in opposite directions, the speed of the sound wave will be decreased by the speed of the wind.

- The viscosity of the medium. Medium viscosity determines the rate at which sound is attenuated. For many media, such as air or water, attenuation due to viscosity is negligible.

When sound is moving through a medium that does not have constant physical properties, it may be refracted (either dispersed or focused).[5]

Spherical compression (longitudinal) waves

The mechanical vibrations that can be interpreted as sound can travel through all forms of matter: gases, liquids, solids, and plasmas. The matter that supports the sound is called the medium. Sound cannot travel through a vacuum.[6][7]

Waves

Sound is transmitted through gases, plasma, and liquids as longitudinal waves, also called compression waves. It requires a medium to propagate. Through solids, however, it can be transmitted as both longitudinal waves and transverse waves. Longitudinal sound waves are waves of alternating pressure deviations from the equilibrium pressure, causing local regions of compression and rarefaction, while transverse waves (in solids) are waves of alternating shear stress at right angle to the direction of propagation.

Sound waves may be viewed using parabolic mirrors and objects that produce sound.[8]

The energy carried by an oscillating sound wave converts back and forth between the potential energy of the extra compression (in case of longitudinal waves) or lateral displacement strain (in case of transverse waves) of the matter, and the kinetic energy of the displacement velocity of particles of the medium.

Longitudinal plane wave

Transverse plane wave

Longitudinal and transverse plane wave

A ‘pressure over time’ graph of a 20 ms recording of a clarinet tone demonstrates the two fundamental elements of sound: Pressure and Time.

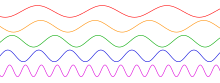

Sounds can be represented as a mixture of their component Sinusoidal waves of different frequencies. The bottom waves have higher frequencies than those above. The horizontal axis represents time.

Although there are many complexities relating to the transmission of sounds, at the point of reception (i.e. the ears), sound is readily dividable into two simple elements: pressure and time. These fundamental elements form the basis of all sound waves. They can be used to describe, in absolute terms, every sound we hear.

In order to understand the sound more fully, a complex wave such as the one shown in a blue background on the right of this text, is usually separated into its component parts, which are a combination of various sound wave frequencies (and noise).[9][10][11]

Sound waves are often simplified to a description in terms of sinusoidal plane waves, which are characterized by these generic properties:

- Frequency, or its inverse, wavelength

- Amplitude, sound pressure or Intensity

- Speed of sound

- Direction

Sound that is perceptible by humans has frequencies from about 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz. In air at standard temperature and pressure, the corresponding wavelengths of sound waves range from 17 m (56 ft) to 17 mm (0.67 in). Sometimes speed and direction are combined as a velocity vector; wave number and direction are combined as a wave vector.

Transverse waves, also known as shear waves, have the additional property, polarization, and are not a characteristic of sound waves.

Speed

U.S. Navy F/A-18 approaching the speed of sound. The white halo is formed by condensed water droplets thought to result from a drop in air pressure around the aircraft (see Prandtl–Glauert singularity).[12]

The speed of sound depends on the medium the waves pass through, and is a fundamental property of the material. The first significant effort towards measurement of the speed of sound was made by Isaac Newton. He believed the speed of sound in a particular substance was equal to the square root of the pressure acting on it divided by its density:

This was later proven wrong and the French mathematician Laplace corrected the formula by deducing that the phenomenon of sound travelling is not isothermal, as believed by Newton, but adiabatic. He added another factor to the equation—gamma—and multiplied

by

thus coming up with the equation

Since

the final equation came up to be

which is also known as the Newton–Laplace equation. In this equation, K is the elastic bulk modulus, c is the velocity of sound, and

Those physical properties and the speed of sound change with ambient conditions. For example, the speed of sound in gases depends on temperature. In 20 °C (68 °F) air at sea level, the speed of sound is approximately 343 m/s (1,230 km/h; 767 mph) using the formula v [m/s] = 331 + 0.6 T [°C]. The speed of sound is also slightly sensitive, being subject to a second-order anharmonic effect, to the sound amplitude, which means there are non-linear propagation effects, such as the production of harmonics and mixed tones not present in the original sound (see parametric array). If relativistic effects are important, the speed of sound is calculated from the relativistic Euler equations.

In fresh water the speed of sound is approximately 1,482 m/s (5,335 km/h; 3,315 mph). In steel, the speed of sound is about 5,960 m/s (21,460 km/h; 13,330 mph). Sound moves the fastest in solid atomic hydrogen at about 36,000 m/s (129,600 km/h; 80,530 mph).[13][14]

Sound pressure level

| Sound measurements | |

|---|---|

|

Characteristic |

Symbols |

| Sound pressure | p, SPL,LPA |

| Particle velocity | v, SVL |

| Particle displacement | δ |

| Sound intensity | I, SIL |

| Sound power | P, SWL, LWA |

| Sound energy | W |

| Sound energy density | w |

| Sound exposure | E, SEL |

| Acoustic impedance | Z |

| Audio frequency | AF |

| Transmission loss | TL |

|

|

|

|

Sound pressure is the difference, in a given medium, between average local pressure and the pressure in the sound wave. A square of this difference (i.e., a square of the deviation from the equilibrium pressure) is usually averaged over time and/or space, and a square root of this average provides a root mean square (RMS) value. For example, 1 Pa RMS sound pressure (94 dBSPL) in atmospheric air implies that the actual pressure in the sound wave oscillates between (1 atm

As the human ear can detect sounds with a wide range of amplitudes, sound pressure is often measured as a level on a logarithmic decibel scale. The sound pressure level (SPL) or Lp is defined as

- where p is the root-mean-square sound pressure and

is a reference sound pressure. Commonly used reference sound pressures, defined in the standard ANSI S1.1-1994, are 20 µPa in air and 1 µPa in water. Without a specified reference sound pressure, a value expressed in decibels cannot represent a sound pressure level.

Since the human ear does not have a flat spectral response, sound pressures are often frequency weighted so that the measured level matches perceived levels more closely. The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) has defined several weighting schemes. A-weighting attempts to match the response of the human ear to noise and A-weighted sound pressure levels are labeled dBA. C-weighting is used to measure peak levels.

Perception

A distinct use of the term sound from its use in physics is that in physiology and psychology, where the term refers to the subject of perception by the brain. The field of psychoacoustics is dedicated to such studies. Webster’s 1936 dictionary defined sound as: «1. The sensation of hearing, that which is heard; specif.: a. Psychophysics. Sensation due to stimulation of the auditory nerves and auditory centers of the brain, usually by vibrations transmitted in a material medium, commonly air, affecting the organ of hearing. b. Physics. Vibrational energy which occasions such a sensation. Sound is propagated by progressive longitudinal vibratory disturbances (sound waves).»[15] This means that the correct response to the question: «if a tree falls in the forest with no one to hear it fall, does it make a sound?» is «yes», and «no», dependent on whether being answered using the physical, or the psychophysical definition, respectively.

The physical reception of sound in any hearing organism is limited to a range of frequencies. Humans normally hear sound frequencies between approximately 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz (20 kHz),[16]: 382 The upper limit decreases with age.[16]: 249 Sometimes sound refers to only those vibrations with frequencies that are within the hearing range for humans[17] or sometimes it relates to a particular animal. Other species have different ranges of hearing. For example, dogs can perceive vibrations higher than 20 kHz.

As a signal perceived by one of the major senses, sound is used by many species for detecting danger, navigation, predation, and communication. Earth’s atmosphere, water, and virtually any physical phenomenon, such as fire, rain, wind, surf, or earthquake, produces (and is characterized by) its unique sounds. Many species, such as frogs, birds, marine and terrestrial mammals, have also developed special organs to produce sound. In some species, these produce song and speech. Furthermore, humans have developed culture and technology (such as music, telephone and radio) that allows them to generate, record, transmit, and broadcast sound.

Noise is a term often used to refer to an unwanted sound. In science and engineering, noise is an undesirable component that obscures a wanted signal. However, in sound perception it can often be used to identify the source of a sound and is an important component of timbre perception (see above).

Soundscape is the component of the acoustic environment that can be perceived by humans. The acoustic environment is the combination of all sounds (whether audible to humans or not) within a given area as modified by the environment and understood by people, in context of the surrounding environment.

There are, historically, six experimentally separable ways in which sound waves are analysed. They are: pitch, duration, loudness, timbre, sonic texture and spatial location.[18] Some of these terms have a standardised definition (for instance in the ANSI Acoustical Terminology ANSI/ASA S1.1-2013). More recent approaches have also considered temporal envelope and temporal fine structure as perceptually relevant analyses.[19][20][21]

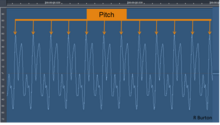

Pitch

Figure 1. Pitch perception

Pitch is perceived as how «low» or «high» a sound is and represents the cyclic, repetitive nature of the vibrations that make up sound. For simple sounds, pitch relates to the frequency of the slowest vibration in the sound (called the fundamental harmonic). In the case of complex sounds, pitch perception can vary. Sometimes individuals identify different pitches for the same sound, based on their personal experience of particular sound patterns. Selection of a particular pitch is determined by pre-conscious examination of vibrations, including their frequencies and the balance between them. Specific attention is given to recognising potential harmonics.[22][23] Every sound is placed on a pitch continuum from low to high. For example: white noise (random noise spread evenly across all frequencies) sounds higher in pitch than pink noise (random noise spread evenly across octaves) as white noise has more high frequency content. Figure 1 shows an example of pitch recognition. During the listening process, each sound is analysed for a repeating pattern (See Figure 1: orange arrows) and the results forwarded to the auditory cortex as a single pitch of a certain height (octave) and chroma (note name).

Duration

Figure 2. Duration perception

Duration is perceived as how «long» or «short» a sound is and relates to onset and offset signals created by nerve responses to sounds. The duration of a sound usually lasts from the time the sound is first noticed until the sound is identified as having changed or ceased.[24] Sometimes this is not directly related to the physical duration of a sound. For example; in a noisy environment, gapped sounds (sounds that stop and start) can sound as if they are continuous because the offset messages are missed owing to disruptions from noises in the same general bandwidth.[25] This can be of great benefit in understanding distorted messages such as radio signals that suffer from interference, as (owing to this effect) the message is heard as if it was continuous. Figure 2 gives an example of duration identification. When a new sound is noticed (see Figure 2, Green arrows), a sound onset message is sent to the auditory cortex. When the repeating pattern is missed, a sound offset messages is sent.

Loudness

Figure 3. Loudness perception

Loudness is perceived as how «loud» or «soft» a sound is and relates to the totalled number of auditory nerve stimulations over short cyclic time periods, most likely over the duration of theta wave cycles.[26][27][28] This means that at short durations, a very short sound can sound softer than a longer sound even though they are presented at the same intensity level. Past around 200 ms this is no longer the case and the duration of the sound no longer affects the apparent loudness of the sound. Figure 3 gives an impression of how loudness information is summed over a period of about 200 ms before being sent to the auditory cortex. Louder signals create a greater ‘push’ on the Basilar membrane and thus stimulate more nerves, creating a stronger loudness signal. A more complex signal also creates more nerve firings and so sounds louder (for the same wave amplitude) than a simpler sound, such as a sine wave.

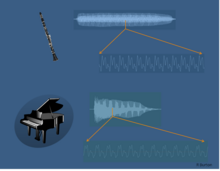

Timbre

Figure 4. Timbre perception

Timbre is perceived as the quality of different sounds (e.g. the thud of a fallen rock, the whir of a drill, the tone of a musical instrument or the quality of a voice) and represents the pre-conscious allocation of a sonic identity to a sound (e.g. “it’s an oboe!»). This identity is based on information gained from frequency transients, noisiness, unsteadiness, perceived pitch and the spread and intensity of overtones in the sound over an extended time frame.[9][10][11] The way a sound changes over time (see figure 4) provides most of the information for timbre identification. Even though a small section of the wave form from each instrument looks very similar (see the expanded sections indicated by the orange arrows in figure 4), differences in changes over time between the clarinet and the piano are evident in both loudness and harmonic content. Less noticeable are the different noises heard, such as air hisses for the clarinet and hammer strikes for the piano.

Texture

Sonic texture relates to the number of sound sources and the interaction between them.[29][30] The word texture, in this context, relates to the cognitive separation of auditory objects.[31] In music, texture is often referred to as the difference between unison, polyphony and homophony, but it can also relate (for example) to a busy cafe; a sound which might be referred to as cacophony.

Spatial location

Spatial location represents the cognitive placement of a sound in an environmental context; including the placement of a sound on both the horizontal and vertical plane, the distance from the sound source and the characteristics of the sonic environment.[31][32] In a thick texture, it is possible to identify multiple sound sources using a combination of spatial location and timbre identification.

Frequency

Ultrasound

Approximate frequency ranges corresponding to ultrasound, with rough guide of some applications

Ultrasound is sound waves with frequencies higher than 20,000 Hz. Ultrasound is not different from audible sound in its physical properties it just cannot be heard by humans. Ultrasound devices operate with frequencies from 20 kHz up to several gigahertz.

Medical ultrasound is commonly used for diagnostics and treatment.

Infrasound

Infrasound is sound waves with frequencies lower than 20 Hz. Although sounds of such low frequency are too low for humans to hear, whales, elephants and other animals can detect infrasound and use it to communicate. It can be used to detect volcanic eruptions and is used in some types of music.[33]

See also

- Sound sources

- Earphones

- Musical instrument

- Sonar

- Sound box

- Sound reproduction

- Sound measurement

- Acoustic impedance

- Acoustic velocity

- Characteristic impedance

- Mel scale

- Particle acceleration

- Particle amplitude

- Particle displacement

- Particle velocity

- Phon

- Sone

- Sound energy flux

- Sound impedance

- Sound intensity level

- Sound power

- Sound power level

- General

- Acoustic theory

- Beat

- Doppler effect

- Echo

- Infrasound — sound at extremely low frequencies

- List of unexplained sounds

- Musical tone

- Resonance

- Reverberation

- Sonic weaponry

- Sound synthesis

- Soundproofing

- Structural acoustics

References

- ^ Fundamentals of Telephone Communication Systems. Western Electrical Company. 1969. p. 2.1.

- ^ ANSI S1.1-1994. American National Standard: Acoustic Terminology. Sec 3.03.

- ^ Acoustical Society of America. «PACS 2010 Regular Edition—Acoustics Appendix». Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ ANSI/ASA S1.1-2013

- ^ a b «The Propagation of sound». Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Is there sound in space? Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine Northwestern University.

- ^ Can you hear sounds in space? (Beginner) Archived 2017-06-18 at the Wayback Machine. Cornell University.

- ^ «What Does Sound Look Like?». NPR. YouTube. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ a b Handel, S. (1995). Timbre perception and auditory object identification Archived 2020-01-10 at the Wayback Machine. Hearing, 425–461.

- ^ a b Kendall, R.A. (1986). The role of acoustic signal partitions in listener categorization of musical phrases. Music Perception, 185–213.

- ^ a b Matthews, M. (1999). Introduction to timbre. In P.R. Cook (Ed.), Music, cognition, and computerized sound: An introduction to psychoacoustic (pp. 79–88). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT press.

- ^ Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (19 August 2007). «A Sonic Boom». Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ «Scientists find upper limit for the speed of sound». Archived from the original on 2020-10-09. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- ^ Trachenko, K.; Monserrat, B.; Pickard, C. J.; Brazhkin, V. V. (2020). «Speed of sound from fundamental physical constants». Science Advances. 6 (41): eabc8662. arXiv:2004.04818. Bibcode:2020SciA….6.8662T. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abc8662. PMC 7546695. PMID 33036979.

- ^ Webster, Noah (1936). Sound. In Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (Fifth ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: The Riverside Press. pp. 950–951.

- ^ a b Olson, Harry F. Autor (1967). Music, Physics and Engineering. Dover Publications. p. 249. ISBN 9780486217697.

- ^ «The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language» (Fourth ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company. 2000. Archived from the original on June 25, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ Burton, R.L. (2015). The elements of music: what are they, and who cares? Archived 2020-05-10 at the Wayback Machine In J. Rosevear & S. Harding. (Eds.), ASME XXth National Conference proceedings. Paper presented at: Music: Educating for life: ASME XXth National Conference (pp. 22–28), Parkville, Victoria: The Australian Society for Music Education Inc.

- ^ Viemeister, Neal F.; Plack, Christopher J. (1993), «Time Analysis», Springer Handbook of Auditory Research, Springer New York, pp. 116–154, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-2728-1_4, ISBN 9781461276449

- ^ Rosen, Stuart (1992-06-29). «Temporal information in speech: acoustic, auditory and linguistic aspects». Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 336 (1278): 367–373. Bibcode:1992RSPTB.336..367R. doi:10.1098/rstb.1992.0070. ISSN 0962-8436. PMID 1354376.

- ^ Moore, Brian C.J. (2008-10-15). «The Role of Temporal Fine Structure Processing in Pitch Perception, Masking, and Speech Perception for Normal-Hearing and Hearing-Impaired People». Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology. 9 (4): 399–406. doi:10.1007/s10162-008-0143-x. ISSN 1525-3961. PMC 2580810. PMID 18855069.

- ^ De Cheveigne, A. (2005). Pitch perception models. Pitch, 169-233.

- ^ Krumbholz, K.; Patterson, R.; Seither-Preisler, A.; Lammertmann, C.; Lütkenhöner, B. (2003). «Neuromagnetic evidence for a pitch processing center in Heschl’s gyrus». Cerebral Cortex. 13 (7): 765–772. doi:10.1093/cercor/13.7.765. PMID 12816892.

- ^ Jones, S.; Longe, O.; Pato, M.V. (1998). «Auditory evoked potentials to abrupt pitch and timbre change of complex tones: electrophysiological evidence of streaming?». Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 108 (2): 131–142. doi:10.1016/s0168-5597(97)00077-4. PMID 9566626.

- ^ Nishihara, M.; Inui, K.; Morita, T.; Kodaira, M.; Mochizuki, H.; Otsuru, N.; Kakigi, R. (2014). «Echoic memory: Investigation of its temporal resolution by auditory offset cortical responses». PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e106553. Bibcode:2014PLoSO…9j6553N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106553. PMC 4149571. PMID 25170608.

- ^ Corwin, J. (2009), The auditory system (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-28, retrieved 2013-04-06

- ^ Massaro, D.W. (1972). «Preperceptual images, processing time, and perceptual units in auditory perception». Psychological Review. 79 (2): 124–145. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.468.6614. doi:10.1037/h0032264. PMID 5024158.

- ^ Zwislocki, J.J. (1969). «Temporal summation of loudness: an analysis». The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 46 (2B): 431–441. Bibcode:1969ASAJ…46..431Z. doi:10.1121/1.1911708. PMID 5804115.

- ^ Cohen, D.; Dubnov, S. (1997), «Gestalt phenomena in musical texture», Journal of New Music Research, 26 (4): 277–314, doi:10.1080/09298219708570732, archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-11-21, retrieved 2015-11-19

- ^ Kamien, R. (1980). Music: an appreciation. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 62

- ^ a b Cariani, Peter; Micheyl, Christophe (2012). «Toward a Theory of Information Processing in Auditory Cortex». The Human Auditory Cortex. Springer Handbook of Auditory Research. Vol. 43. pp. 351–390. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-2314-0_13. ISBN 978-1-4614-2313-3.

- ^ Levitin, D.J. (1999). Memory for musical attributes. In P.R. Cook (Ed.), Music, cognition, and computerized sound: An introduction to psychoacoustics (pp. 105–127). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT press.

- ^ Leventhall, Geoff (2007-01-01). «What is infrasound?». Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. Effects of ultrasound and infrasound relevant to human health. 93 (1): 130–137. doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2006.07.006. ISSN 0079-6107. PMID 16934315.

External links

Wikiquote has quotations related to Sound.

Wikibooks has more on the topic of: Sound

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sound.

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Eric Mack (20 May 2019). «Stanford scientists created a sound so loud it instantly boils water». CNET.

- Sounds Amazing; a KS3/4 learning resource for sound and waves (uses Flash)

- HyperPhysics: Sound and Hearing

- Introduction to the Physics of Sound

- Hearing curves and on-line hearing test

- Audio for the 21st Century Archived 2009-01-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Conversion of sound units and levels

- Sound calculations

- Audio Check: a free collection of audio tests and test tones playable on-line

- More Sounds Amazing; a sixth-form learning resource about sound waves

A disturbance that transfers energy from place to place

the ability to do work

the material through which a wave travels

waves that require a medium through which to travel

A repeated back-and-forth or up-and-down motion

a wave in which the particles of the medium move perpendicularly to the direction the wave is traveling

The high points of a transverse wave

The lowest part of a transverse wave.

the areas where the particles in a longitudinal wave are close together

the part of a longitudinal wave where the particles of the medium are far apart

Sets found in the same folder

Other sets by this creator

Recommended textbook solutions

Human Resource Management

15th Edition•ISBN: 9781337520164John David Jackson, Patricia Meglich, Robert Mathis, Sean Valentine

249 solutions

Introductory Astronomy

3rd Edition•ISBN: 9780321820464Abe Mizrahi, Edward E. Prather, Gina Brissenden, Jeff P. Adams

429 solutions

Other Quizlet sets

Sound is all about vibrations.

The source of a sound vibrates, bumping into nearby air molecules which in turn bump into their neighbours, and so forth. This results in a wave of vibrations travelling through the air to the eardrum, which in turn also vibrates. What the sound wave will sound like when it reaches the ear depends on a number of things such as the medium it travels through and the strength of the initial vibration.

In the following activities, students will use simple materials to create, visualize and feel sound waves, investigate vibration and its role in producing sound, and make their own percussion instruments.

List of Activities:

Sound = Vibration, Vibration, Vibration

Sound Map

Telephone Lines

Modelling a Sound Wave

Speaking Involves Air, Vibration and Muscle

Feeling the Vibes!

Exploring Pitch and Volume

Musical Bottles

Whirly Tubes

Weight a Minute

Boomwhacker Orchestra

Homemade Kazoo

Rainsticks

Bullfrog Caller

Bullroarer

Spoons on Strings

Objectives

-

Describe how sound is produced.

-

Understand how our inner ear contributes to hearing.

-

List some properties of sound.

-

Describe what pitch is and how it varies.

Materials

-

See individual activities for materials.

Background

Sound is a type of energy made by vibrations. When an object vibrates, it causes movement in surrounding air molecules. These molecules bump into the molecules close to them, causing them to vibrate as well. This makes them bump into more nearby air molecules. This “chain reaction” movement, called sound waves, keeps going until the molecules run out of energy. As a result, there is a series of molecular collisions as the sound wave passes through the air, but the air molecules themselves don’t travel with the wave. As it is disturbed, each molecule just moves away from a resting point but then eventually returns to it.

Pitch and Frequency

If your ear is within range of such vibrations, you hear the sound. However, the vibrations need to be at a certain speed in order for us to hear them. For example, we would not be able to hear the slow vibrations that are made by waving our hands in the air. The slowest vibration human ears can hear is 20 vibrations per second. That would be a very low-pitched sound. The fastest vibration we can hear is 20,000 vibrations per second, which would be a very high-pitched sound. Cats can hear even higher pitches than dogs, and porpoises can hear the fastest vibrations of all (up to 150,000 times per second!). The number of vibrations per second is referred to as an object’s frequency, measured in Hertz (Hz).

Pitch is related to frequency, but they are not exactly the same. Frequency is the scientific measure of pitch. That is, while frequency is objective, pitch is completely subjective. Sound waves themselves do not have pitch; their vibrations can be measured to obtain a frequency, but it takes a human brain to map them to that internal quality of pitch.

The pitch of a sound is largely determined by the mass (weight) of the vibrating object. Generally, the greater the mass, the more slowly it vibrates and the lower the pitch. However, the pitch can be altered by changing the tension or rigidity of the object. For example, a heavy E string on an instrument can be made to sound higher than a thin E string by tightening the tuning pegs, so that there is more tension on the string.

Nearly all objects, when hit, struck, plucked, strummed or somehow disturbed, will vibrate. When these objects vibrate, they tend to vibrate at a particular frequency or set of frequencies. This is known as the natural frequency of the object. For example, if you ‘ping’ a glass with your finger, the glass will produce a sound at a pitch that is its natural frequency. It will make this same sound every time. This sound can be changed, however, by altering the vibrating mass of the glass. For example, adding water causes the glass to get heavier (increase in mass) and thus harder to move, so it tends to vibrate more slowly and at a lower pitch.

What is Sound?

When we hear something, we are sensing the vibrations in the air. These vibrations enter the outer ear and cause our eardrums to vibrate (or oscillate). Attached to the eardrum are three tiny bones that also vibrate: the hammer, the anvil, and the stirrup. These bones make larger vibrations within the inner ear, essentially amplifying the incoming vibrations before they are picked up by the auditory nerve.

The properties of a sound wave change when it travels through different media: gas (e.g. air), liquid (e.g. water) or solid (e.g. bone). When a wave passes through a denser medium, it goes faster than it does through a less-dense medium. This means that sound travels faster through water than through air, and faster through bone than through water.

When molecules in a medium vibrate, they can move back and forth or up and down. Sound energy causes the molecules to move back and forth in the same direction that the sound is travelling. This is known as a longitudinal wave. (Transverse waves occur when the molecules vibrate up and down, perpendicular to the direction that the wave travels).

Speaking (as well as hearing) involves vibrations. To speak, we move air past our vocal cords, which makes them vibrate. We change the sounds we make by stretching those vocal cords. When the vocal cords are stretched we make high sounds and when they are loose we make lower sounds. This is known as the pitch of the sound.

The sounds we hear every day are actually collections of simpler sounds. A musical sound is called a tone. If we strike a tuning fork, it gives off a pure tone, which is the sound of a single frequency. But if we were to sing or play a note on a trumpet or violin, the result is a combination of one main frequency with other tones. This gives each musical instrument its characteristic sound.

Fun Facts!

- The speed of sound is around 1,230 kilometres per hour (or 767 miles per hour).

- The loud noise you create by cracking a whip occurs because the tip is moving so fast it breaks the speed of sound!

Vocabulary

amplification: The process of increasing or making stronger.

compression: The process of squeezing together or closer.

frequency: A measure of the number of vibrations per second.

Hertz: The metric unit for frequency (1 Hertz (Hz) = 1 vibration per second).

longitudinal wave: A wave with particles vibrating in the same direction that the wave is travelling.

medium: A material (solid, liquid or gas) that is used or travelled through.

molecule: A particle made up of particular atoms.

oscillation: Vibration.

percussion instrument: Any musical object that produces a sound when hit with an implement, shaken, rubbed, or scraped, or by any other action which causes the object to vibrate in a rhythmic manner.

pitch: The quality of the actual note behind a sound, such as G sharp; a subjective definition of sounds as high or low in tone.

pressure: Applied force.

rarefaction: The process of spreading apart, or decompressing.

resonance: The tendency of an object to vibrate at its maximum wave size (amplitude) at a certain frequency.

tension: A tightening stress force related to stretching an object.

tone: The quality of sound (e.g. dull, weak, strong).

transverse wave: A wave with particles vibrating perpendicular to the direction that the wave is travelling; this type or wave is not produced in air, like longitudinal sound waves.

vibration: Repetitive motion of an object around its resting point; the backbone of sound.

Other Resources

Science World | YouTube | Sound

Science World | YouTube| The Sound Show

Canada Science and Technology Museum |Strin-o-lin

Online Tuning Forks

Artists Helping Children: Arts & Crafts | Musical Instrument Crafts for Kids

Science Kids at Home | What is Sound?

To purchase Boomwhackers:

Long & McQuade Musical Instruments

Boreal Science

I do not mean «Phonaesthetics» or euphony or cacophony which carry a value judgement. Words have an audio ‘pattern’, mostly unique and different from other words. This is the unique audio «finger-print» of the word, which does not carry a un/pleasant connotation — it is simply the sound of a (particular word) being spoken. I am looking for the definition or term for the sound of word/s. Does such a term exist? I used to think it was «nomenclature».

asked Apr 21, 2014 at 20:18

4

Most dictionaries will only give equivalents to the following two definitions…

phonology

1:The system of contrastive relationships among the speech sounds that constitute the fundamental components of a language.

2:The study of phonological relationships within a language or between different languages.

But here are almost 3000 written instances of…

the phonology of the word [some word being discussed]…

I think that’s enough to establish that it’s a valid «neutral» term to use in this way.

answered Apr 21, 2014 at 21:08

FumbleFingersFumbleFingers

137k45 gold badges282 silver badges501 bronze badges

1

It is called a signifier.

1 Linguistics A linguistic unit or pattern, such as a succession of speech sounds, written symbols, or gestures, that conveys meaning; a linguistic sign.

The signifier of the concept «tree» is, in English, the string of speech sounds (t), (r), and (ē); in German, (b), (ou), and (m).

2 the phonological or orthographic sound or appearance of a word that can be used to describe or identify something

According to Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure:

The sign (signe) is described as a «double entity», made up of the signifier, or sound image (signifiant), and the signified, or concept (signifié).

The sound image is a psychological, not a material concept, belonging to the system. Both components of the linguistic sign are inseparable.

answered Apr 22, 2014 at 0:13

ermanenermanen

59k34 gold badges159 silver badges291 bronze badges

2

The characteristic sound associated with a word when it is spoken correctly is its pronunciation .

answered Apr 21, 2014 at 21:24

Gary’s StudentGary’s Student

6,7412 gold badges23 silver badges35 bronze badges

answered Apr 21, 2014 at 20:54

Third NewsThird News

7,43816 silver badges28 bronze badges

Are you talking about the absolute simplest form of words?

Morpheme: A morphological unit of a language that cannot be further divided (e.g., in, come, -ing, forming incoming).

This isn’t the sound of words, but the sounds that make up words.

The word for sounds of a word is: Phonology (see @FumbleFingers’ answer) which is the branch of linguistics concerned with the systematic organization of sounds in languages.

An interesting field that delves into this is Morphophonology as it is a branch of linguistics which studies the interaction between morphological and phonological or phonetic processes.

answered Apr 21, 2014 at 21:30

TuckerTucker

2,82713 silver badges24 bronze badges