Frequently Asked Questions

What is a word search?

A word search is a puzzle where there are rows of letters placed in the shape of a square, and there are words written forwards, backwards, horizontal, vertical or diagonal. There will be a list of words for the player to look for and the goal of the player is to find those words hidden in the word search puzzle, and highlight them.

How do I choose the words to use in my word search?

Once you’ve picked a theme, choose words that have a variety of different lengths, difficulty levels and letters. You don’t need to worry about trying to fit the words together with each other because WordMint will do that for you!

How are word searches used in the classroom?

Word search games are an excellent tool for teachers, and an excellent resource for students. They help to encourage wider vocabulary, as well as testing cognitive abilities and pattern-finding skills.

Because the word search templates are completely custom, you can create suitable word searches for children in kindergarten, all the way up to college students.

Who is a word search suitable for?

One of the common word search faq’s is whether there is an age limit or what age kids can start doing word searches. The fantastic thing about word search exercises is, they are completely flexible for whatever age or reading level you need.

Word searches can use any word you like, big or small, so there are literally countless combinations that you can create for templates. It is easy to customise the template to the age or learning level of your students.

How do I create a word search template?

For the easiest word search templates, WordMint is the way to go!

Pre-made templates

For a quick an easy pre-made template, simply search through WordMint’s existing 500,000+ templates. With so many to choose from, you’re bound to find the right one for you!

Create your own from scratch

- Log in to your account (it’s free to join!)

- Head to ‘My Puzzles’

- Click ‘Create New Puzzle’ and select ‘Word Search’

- Select your layout, enter your title and your chosen words

- That’s it! The template builder will create your word search template for you and you can save it to your account, export as a Word document or PDF and print!

How can I print my word search template?

All of our templates can be exported into Microsoft Word to easily print, or you can save your work as a PDF to print for the entire class. Your puzzles get saved into your account for easy access and printing in the future, so you don’t need to worry about saving them at work or at home!

Can I create a word search in other languages?

Word searches are a fantastic resource for students learning a foreign language as it tests their reading comprehension skills in a fun, engaging way.

We have full support for word search templates in Spanish, French and Japanese with diacritics including over 100,000 images.

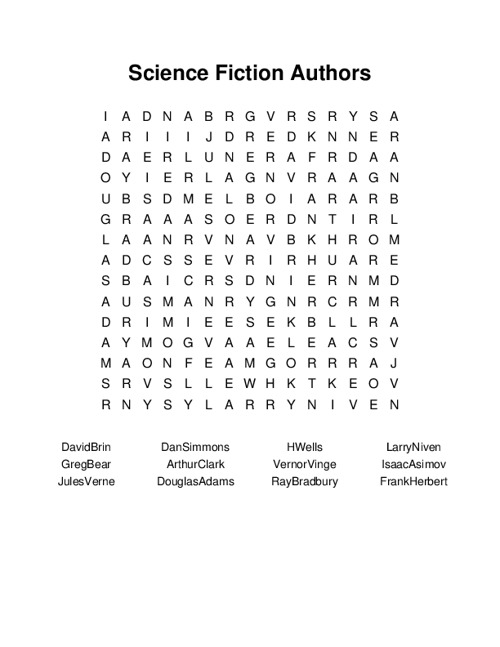

- Home»

- Word Search»

- Books & Literature»

- Science Fiction Authors

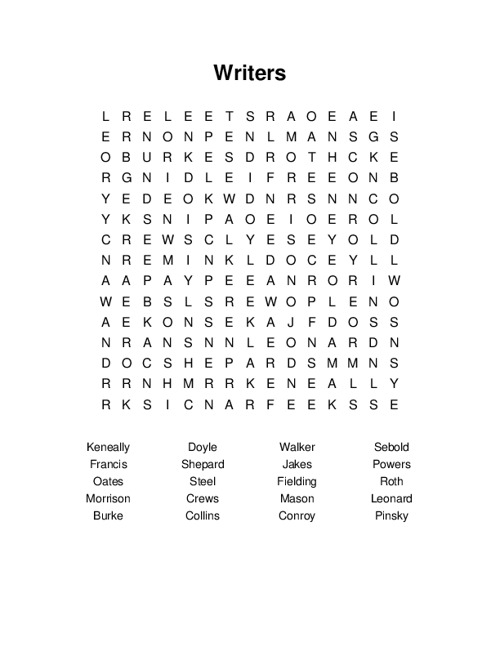

Download and print this Science Fiction Authors word search puzzle or play online.

Recommended: Check out this Advance Word Search Maker to create commercial use printable puzzles.

Paper Version — Download and Print

PDF will include puzzle sheet and the answer key.

Edit

Print

PDF — Letter

PDF — A4

Play Online

Play Online — Press and hold left mouse button and drag to select the letters on the grid below

Puzzle Settings:

Grid

Difficulty

Sort alphabetically

Lowercase letters

Use word list letters

Regenerate

More Books & Literature Puzzles

-

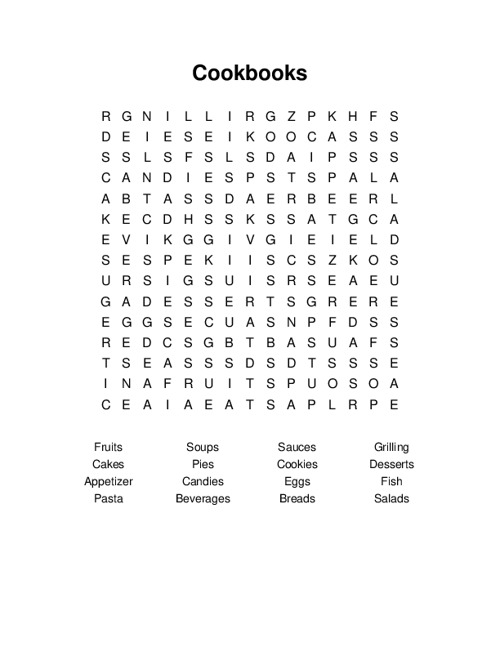

Cookbooks

-

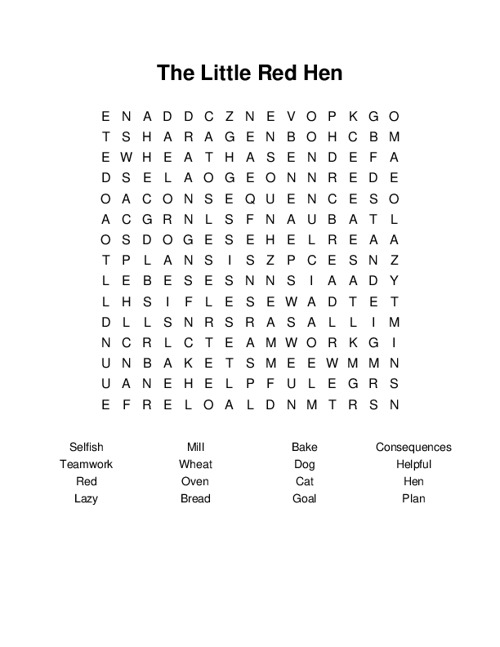

The Little Red Hen

-

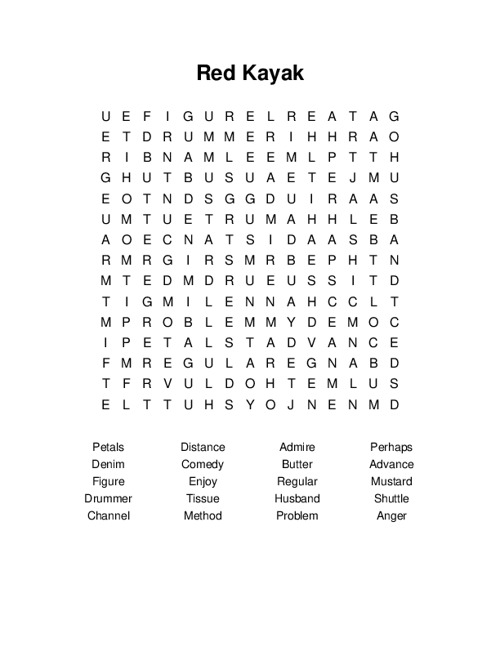

Red Kayak

-

Writers

Browse all Books & Literature Puzzles

WORDS LIST: David Brin, Dan Simmons, H Wells, Larry Niven, Greg Bear, Arthur Clark, Vernor Vinge, Isaac Asimov, Jules Verne, Douglas Adams, Ray Bradbury, Frank Herbert

Learn words with Flashcards and other activities

Other learning activities

Full list of words from this list:

-

analysis

abstract separation of something into its various parts

Teacher preparation

◆ Prepare the

Analysis Cards (Figure 1B), either as reusable stand-alones or handouts. -

analyze

break down into components or essential features

Students have

analyzed literature for years in English classes but just never thought, in most cases, of applying those skills to reading science. -

anthology

a collection of selected literary passages

This is true because science fiction stories, particularly the short form readily available in “Year’s Best”

anthologies in libraries (Hartwell 2005; Dozois 2005), speculate from known concepts. -

assess

estimate the nature, quality, ability or significance of

This can be an important lesson in

assessing the credibility of materials taken from the internet. -

assessment

the act of judging a person or situation or event

Figure 2

(p. 42) supplies a quick self-

assessment tool, to be applied before and after the activity. -

author

a person who writes professionally

Most science fiction

authors ask, “What if?” and speculate about what could happen if a certain aspect of science or technology existed—or did not exist. -

awareness

state of elementary or undifferentiated consciousness

[Note: Students should gain an

awareness of source, in terms of influences on the author and what the author wishes to convey through the story. -

brochure

a small booklet with information about a product or service

◆ Obtain science nonfiction such as articles from Discover, Popular Science, and Science News magazines, newspaper “science” columns,

brochures from varying sources, print versions of media broadcasts, or documentaries (ideally both current and older than 20 years) for students to analyze. -

connotation

an idea that is implied or suggested

This without a doubt annoys many scientists because the “fiction” label has the popular

connotations of “willingly false or misleading.” -

consensus

agreement in the judgment reached by a group as a whole

Teachers should provide the biographical information after students have reached a

consensus about the author. -

context

the set of facts or circumstances that surround a situation

As well, they should have an awareness of

context. -

creativity

the ability to bring something into existence

The opportunity for literacy skills

Science fiction is read not only for enjoyment, but because it digs into scientific concepts with imagination,

creativity, and a thorough appreciation of consequence. -

credible

capable of being believed

A wide variety is preferable to allow a comparison of

credible and some less credible sources while honing critical reading skills. -

database

an organized body of related information

Excellent searchable

database of science fiction, fantasy, and horror writers, with links to author sites and book reviews. -

equation

a mathematical statement that two expressions are the same

Another good example is The Cold

Equation by Tom Godwin (2000) that looks at the unalterable and potentially tragic constraints of space travel. -

evaluate

estimate the nature, quality, ability or significance of

When you

evaluate the quality of scientific information, do you consider both its source and the methods used to obtain it? -

excerpt

a passage selected from a larger work

Excerpts from science textbooks can also be used effectively.

-

extrapolation

an inference about the future based on known facts

Critical thinking blends with literacy in the interpretation and

extrapolation of ideas. -

fantasy

imagination unrestricted by reality

◆ Science Fiction and

Fantasy Writers of America (

www.sfwa.org): -

fascinate

attract; cause to be enamored

Fascinating look at the vocabulary that has come from science fiction.

-

fiction

a literary work based on the imagination

The Science Teacher

38

Science

Fiction &

Scientific Literacy

Incorporating science fiction reading in the science classroom

February 2006

39

The term science fiction has become synonymous, in the media at least, for any discovery in science too inc -

fictional

related to or involving imaginative literary work

We are living in a world that seems science

fictional, and science fiction readers have the advantage of knowing the terrain. -

frustrate

hinder or prevent, as an effort, plan, or desire

Share the wonder

If there is anything

frustrating about writing an article

42 The Science Teacher

like this, it is that I am barely scratching the surface of what science fiction reading and writing can do to help students become scientifically literate—to develop the flexibility of thought and reasoned imagination they will need to succeed in our society. -

global warming

a rise in the average temperature of the earth’s atmosphere

By bringing science into the realm of individual lives as well as entire cultures, these stories are thought experiments about anything we can imagine, from

global warming to evolution. -

hone

sharpen with a whetstone

A wide variety is preferable to allow a comparison of credible and some less credible sources while

honing critical reading skills. -

incorporate

make into a whole or make part of a whole

The Science Teacher

38

Science Fiction &

Scientific Literacy

Incorporating science fiction reading in the science classroom

February 2006

39

The term science fiction has become synonymous, in the media at least, for any discovery in science too incredible or unexpected for the nonscientist to imagine. -

internet

a worldwide network of computer networks

Julie E. Czerneda

Science fiction

internet resources. -

links

a golf course that is built on sandy ground near a shore

Encourages reading, with extensive

links to science fiction sites of interest to librarians and young readers. -

nonfiction

prose writing that is not formed by the imagination

◆ Obtain science

nonfiction such as articles from Discover, Popular Science, and Science News magazines, newspaper “science” columns, brochures from varying sources, print versions of media broadcasts, or documentaries (ideally both current and old -

ongoing

currently happening

Developing scientific literacy is an

ongoing process. -

outer space

any location outside the Earth’s atmosphere

This short story, like all of the stories in the book, focuses on science and the future of work in orbit or

outer space. -

premise

a statement that is held to be true

What is the scientific

premise of this story? -

prepare

make ready or suitable or equip in advance

In many cases individuals most comfortable with the flood of new technologies and scientific discoveries and most able to see past the novelty to the potential for good or ill, have been

prepared by their choice of literature. -

provide

give something useful or necessary to

In this article I make a case for why science fiction should be a part of science curricula and I

provide an all-purpose activity to help teachers use science fiction in the classroom. -

resource

aid or support that may be drawn upon when needed

Science fiction internet

resources. -

science

a branch of study or knowledge involving the observation, investigation, and discovery of general laws or truths that can be tested systematically

The

Science Teacher

38

Science Fiction &

Scientific Literacy

Incorporating science fiction reading in the science classroom

February 2006

39

The term science fiction has become synonymous, in the media at least, for any discovery in science too inc -

science fiction

genre involving the imagined impact of technology on society

The Science Teacher

38

Science Fiction &

Scientific Literacy

Incorporating science fiction reading in the science classroom

February 2006

39

The term science fiction has become synonymous, in the media at least, for any discovery in science too inc -

scientific knowledge

knowledge accumulated by systematic study and organized by general principles

Focus class discussion of student results per article on credibility of source and assumptions by the various authors about the

scientific knowledge of readers. -

scientifically

with respect to science; in a scientific way

Share the wonder

If there is anything frustrating about writing an article

42 The Science Teacher

like this, it is that I am barely scratching the surface of what science fiction reading and writing can do to help students become

scientifically literate—to develop the flexibility of thought and reasoned imagination they will need to succeed in our society. -

short story

a brief but fully developed prose narrative

This

short story, like all of the stories in the book, focuses on science and the future of work in orbit or outer space. -

skill

an ability that has been acquired by training

The opportunity for literacy

skills

Science fiction is read not only for enjoyment, but because it digs into scientific concepts with imagination, creativity, and a thorough appreciation of consequence. -

source

the place where something begins

-

space travel

a voyage outside the Earth’s atmosphere

Another good example is The Cold Equation by Tom Godwin (2000) that looks at the unalterable and potentially tragic constraints of

space travel. -

speculate

reflect deeply on a subject

Most science fiction authors ask, “What if?” and

speculate about what could happen if a certain aspect of science or technology existed—or did not exist. -

stereotype

a conventional or formulaic conception or image

Students examine their own preconceptions, which can be useful to reveal

stereotypes. -

story

a record or narrative description of past events

This short

story, like all of the stories in the book, focuses on science and the future of work in orbit or outer space. -

unalterable

not capable of being changed

Another good example is The Cold Equation by Tom Godwin (2000) that looks at the

unalterable and potentially tragic constraints of space travel. -

underlying

in the nature of something though not readily apparent

Students prepare by analyzing a work of science fiction and examining the

underlying science idea in terms of the attitude and knowledge conveyed through the story about the author, following this with research on the author. -

vocabulary

a language user’s knowledge of words

Fascinating look at the

vocabulary that has come from science fiction.

Created on December 28, 2010

(updated December 28, 2010)

/Vocabulary

Shift into hyperspace and set your blasters to stun. Practice your vocabulary with these sci-fi words.

-

|

see definition»

a robot that looks like a person

-

|

see definition»

reducing, canceling, or protecting against the effect of gravity

-

|

see definition»

a handheld weapon similar to a gun that fires bolts of energy instead of physical projectiles

-

|

see definition»

science fiction dealing with future urban societies dominated by computer technology

-

|

see definition»

a bionic human

-

|

see definition»

originating, existing, or occurring outside the earth or its atmosphere

-

|

see definition»

a fictional space in which extraordinary events happen

-

|

see definition»

a substance that causes the comic-book character Superman to become weak when he is exposed to it

-

|

see definition»

an imaginary creature in books, movies, etc., that lives on or comes from the planet Mars

-

|

see definition»

a theoretical reality that includes a possibly infinite number of parallel universes

-

|

see definition»

the whole or a portion of physical reality determinable by a usually four-dimensional coordinate system

-

|

see definition»

a spacecraft designed for interstellar travel

-

|

see definition»

being above the human : DIVINE

-

|

see definition»

a hypothetical device that permits travel into the past and future

-

|

see definition»

a mysterious flying object in the sky that is sometimes assumed to be a spaceship from another planet

-

|

see definition»

the highest possible speed

-

|

see definition»

a hypothetical structure of space-time envisioned as a tunnel connecting points that are separated in space and time

Return to Week 4: Space Launch page

Practice these words and more with Puku, the award-winning app for kids ages 8-12. Make your own vocab lists to line up with tests and curriculum — subscribe now!

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

Galaxies far, far away. Extraterrestrial lifeforms. Extraordinary futures for humanity, brimming with impossible-seeming technologies, from space travel to artificial intelligence. These are the dazzling, dizzying, reality-defying worlds of science fiction.

But, for as much as science fiction stretches our imagination, the genre is more down-to-earth than you may realize. Many of its writers created or helped popularize originally far-out words that have become part of our daily vocabulary—words based on ideas that are much older than you may think.

What’s more, many of the ideas these sci-fi terms name have since become science fact! Well, we’re still working on that whole time travel thing, but that term is a great place for us to start in our roundup of 10 words we owe to the science fiction universe.

time travel

While the concept of time travel (“hypothetical transport through time into the past or the future”) has been featured in literature as early as, scholars argue, the ancient Indian epic poem the Mahabharata, H. G. Wells gave the English language the much-used terminology on the subject.

In 1894, Wells used the term time travelling (British English spelling uses two Ls) in an essay, “Time Travelling: Possibility or Paradox.” A year later, in his novella The Time Machine, Wells explored time travel in more detail as an unnamed protagonist (known as the Time Traveller) moves backwards and forwards in time, encountering the mythical species of the Eloi and the Morlocks on his way.Time travel as a noun and time-travel as a verb appeared by the early 1900s.

robotics

While the noun robotics is commonplace today, it wasn’t back in 1941 when sci-fi master Isaac Asimov coined the term in a short story published in Astounding Science Fiction and Fact. It took another 20 years before the term really took off, but by the 1980s, robotics had firmly planted itself in the English language.

Robotics means “the use of computer-controlled robots to perform manual tasks, especially on an assembly line.” The word is based on, of course, robot. Robot is also coinage. It entered English in 1922 based on the Czech robot.

Robot comes from Czech author Karel Čapek’s 1920 play, R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots. It is based on such Czech words as robota, “compulsory labor,” and robotník meaning “worker.” In Čapek’s play, robots were artificially made, mass-produced workers.

zero-g

Zero gravity is the condition in which the apparent effect of gravity is zero, and objects float if they aren’t tied down to something larger and more sturdy, like the wall of a spaceship.

The term is found as early as 1915, and its abbreviated form, zero-g, in 1950. But, it was the great science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke who helped bring the terms into the popular imagination with novels The Sands of Mars (1951) and Islands in the Sky (1952).

This concept of zero-g also took root with advances in flight and space exploration in the 1960s.

warp speed

If you’re traveling in a spacecraft at a (very hypothetical) speed faster than light, you’re moving at warp speed. This term was popularized by Star Trek the 1960-70.Warp speed draws on earlier references to warps—metaphorical twists—in time and space during interstellar travel in science fiction. Dating back to science fiction in the 1950s, a time warp, for instance, would allow movement back and forth in time or suspend the passage of time. (Again, extremely hypothetical stuff.)

Since Star Trek, warp speed has spread as term for “an extremely rate of speed” more generally. Buckle up.

droid

Droid, or a robot in human-like form, is a shortened form of android—which actually was used as early as the 1700s, meaning “an automaton in the form of a human being.” The word is based on a Greek andros, meaning “man.”Droid appeared in the 1950s in sci-fi short stories, but it was the 1977 blockbuster Star Wars that brought droid into mainstream usage, thanks in parts to such unforgettable droids as C-3PO and R2-D2.

alien

Alien ultimately comes to English from the Latin alienus, meaning “belonging to others, unnatural, unusual, foreign.” When it first entered English in the 1300s, it referred to an outsider, someone born in another country, or someone who is unfamiliar.

It was not until the late 1920s that alien took on its sci-fi meaning of “an intelligent being from another planet.” Similarly, when earthling first entered English in the late-1500s, it meant someone who lived on earth, not in heaven. Only in the mid-1800s did it take on the sci-fi meaning of a person who is from Earth, not another planet.

nanotechnology

In science fiction, nanites are self-replicating nanorobots, or robots built on the nanoscale. That’s very small: nano- is a measurement on the order of one billionth (10−9).

A term dating back to the 1970s, nanotechnology is technology built for applications on such a scale—of atoms and molecules—to create computer chips and other microscopic devices, especially in medicine.

Perhaps one of the first writers to imagine nanotechnology was the Russian Nikolai Leskov, who wrote an 1881 story featuring a tiny, mechanical steel flea and describes magnification up to 5,000,000 times.

clone

When clone first entered English in 1903, it was used in the context of botany, for genetically identical plants. It comes from the Greek klon, meaning “twig.”

Later, clone took on the sci-fi sense of “artificially duplicated person” thanks to Alvin Toffler’s 1970 book Future Shock. While ethics have deterred the real-life cloning of people, in the 1980s, scientists started seriously discussing cloning animals, and in 1996 the first mammal clone was created in the form of a sheep named Dolly.

cyberpunk

The second half of the 20th century saw the birth of the cyberpunk sci-fi subgenre. Often set in industrial dystopias, cyberpunk features plots related to computing, hackers, and large corrupt corporations.

Perhaps the earliest recorded use of the term was in Bruce Bethke’s story “Cyberpunk,” published in 1983. One year earlier, William Gibson, an early and influential cyberpunk writer, coined the term cyberspace in a story he wrote for the popular sci-fi magazine Omni.

virus

Science fiction writers helped introduced the world to a new sense of virus: the computer virus. One of the earliest uses of this sense of virus comes from a 1970 short story by Gregory Benford in which a malevolent computer program called VIRUS infects computers via their modem connections.

Within the next several years, David Gerrold, Michael Crichton, and John Brunner had all published sci-fi novels featuring computer viruses, and from there, computers along with the viruses that aim to corrupt them became part of language and life beyond science fiction.

Brave New Words

- By Jeff Prucher

- March 31st 2009

We were pretty excited around here when Brave New Words won the Hugo Award. Now that Brave New Words is available in paperback we asked Jeff Prucher, freelance lexicographer and editor for the Oxford English Dictionary‘s science fiction project, to revisit the blog. Below are Prucher’s picks of words that may seem to come from science, but really originate in science fiction.

In no particular order:

1. Robotics. This is probably the most well-known of these, since Isaac Asimov is famous for (among many other things) his three laws of robotics. Even so, I include it because it is one of the only actual sciences to have been first named in a science fiction story (Liar!, 1941). Asimov also named the related occupation (roboticist) and the adjective robotic.

2. Genetic engineering. The other science that received its name from a science fiction story, in this case Jack Williamson’s novel Dragon’s Island, which was coincidentally published in the same year as Liar! The occupation of genetic engineer took a few more years to be named, this time by Poul Anderson.

3. Zero-gravity/zero-g. A defining feature of life in outer space (sans artificial gravity, of course). The first known use of “zero-gravity” is from Jack Binder (better known for his work as an artist) in 1938, and actually refers to the gravityless state of the center of the Earth’s core. Arthur C. Clarke gave us “zero-g” in his 1952 novel Islands in the Sky.

4. Deep space. One of the other defining features of outer space is its essential emptiness. In science fiction, this phrase most commonly refers to a region of empty space between stars or that is remote from the home world. E. E. “Doc” Smith seems to have coined this phrase in 1934. The more common use in the sciences refers to the region of space outside of the Earth’s atmosphere.

5. Ion drive. An ion drive is a type of spaceship engine that creates propulsion by emitting charged particles in the direction opposite of the one you want to travel. The earliest citation in Brave New Words is again from Jack Williamson (The Equalizer, 1947). A number of spacecraft have used this technology, beginning in the 1970s.

6. Pressure suit. A suit that maintains a stable pressure around its occupant; useful in both space exploration and high-altitude flights. This is another one from the fertile mind of E. E. Smith. Curiously, his pressure suits were furred, an innovation not, alas, replicated by NASA.

7. Virus. Computer virus, that is. Dave Gerrold (of “The Trouble With Tribbles” fame) was apparently the first to make the verbal analogy between biological viruses and self-replicating computer programs, in his 1972 story When Harlie Was One.

8. Worm. Another type of self-replicating computer program. So named by John Brunner in his 1975 novel Shockwave Rider.

9. Gas giant. A large planet, like Jupiter or Neptune, that is composed largely of gaseous material. The first known use of this term is from a story (“Solar Plexus”) by James Blish; the odd thing about it is that it was first used in a reprint of the story, eleven years after the story was first published. Whether this is because Blish conceived of the term in the intervening years or read it somewhere else, or whether it was in the original manuscript and got edited out is impossible to say at this point.

Errors made in this blog have been corrected, thank you to our sharp-eyed commenters.

Featured Image Credit: ‘Planet, Moon, Orbit, Solar Systen’, Image by LoganArt, CC0 Public Domain, via pixabay.

Jeff Prucher is a freelance lexicographer and an editor for the Oxford English Dictionary’s science fiction project. He lives in Berkeley with his family.

Our Privacy Policy sets out how Oxford University Press handles your personal information, and your rights to object to your personal information being used for marketing to you or being processed as part of our business activities.

We will only use your personal information to register you for OUPblog articles.

Or subscribe to articles in the subject area by email or RSS