When it comes to creating a compelling and effective document, one of the most important tools at your disposal is the font (also known as «typeface»).

Fonts do much more than improve—or hamper—the legibility of your piece. They set a tone. They’ve got personalities. They evoke feelings. As such, fonts can either reinforce or undermine your brand.

Because fonts are so important, you may want to change the default fonts in Microsoft Word. In this article, you’ll see, step-by-step how to add fonts to Microsoft Word so you can change the default fonts in your document.

You’ll also learn tips on where to find the best Microsoft Word fonts and how to choose the best ones for your document.

(Note: In the tutorials below, I use Microsoft Word for macOS. If you’re on Windows or a different version of Word, then your interface will look different.)

Why Use Premium Fonts in Your Microsoft Word Document?

When it comes to creating documents that get and keep your readers’ attention, fonts are some of your most powerful tools. The right fonts:

- reinforce your branding

- express the right tone

- direct the reader’s attention

- improve readability

You might be tempted to use free fonts for Microsoft Word in your next document. But remember, those built-in MS Word fonts are exactly the same fonts that everyone else is using. Or, you might find a free Microsoft Word fonts download. But free fonts are often not as well-designed as premium fonts.

You can easily add fonts to Microsoft Word from outstanding sources like Envato Elements or GraphicRiver. To be able to download unlimited fonts, then look to Envato Elements. You get access to thousands of fonts. Download as many as you need for one small subscription price.

For one-off projects, GraphicRiver is a great source of the best Microsoft Word fonts on a pay-per-use basis.

And lastly, use the tips above to choose and use fonts effectively in your document. The misuse and overuse of fonts are sure signs of an amateur.

How to Change Microsoft Word Default Font

Word comes with default fonts, but you can change the font to match your branding or to change the tone and personality of the document.

You’ll find that dozens of fonts are already built into Word, and you can replace the default fonts with those. And you can also add new fonts. We’ll talk about how to add fonts to Microsoft Word later in this post.

To change the Microsoft Word default font, you’ve got three options:

1. How to Change the Microsoft Word Default Font for a Block of Text

This is a quick method that’s good to use if you want to change the default font only for one or a few bits of text. Here are the steps:

Step 1. Select the Text

Step 2. Open the Font Selection Tool

Click on the Font selection tool on the ribbon. You must be on the Home tab to see the buttons for formatting text. The Microsoft Word fonts list opens.

Step 3. Find the font you wish to use.

The Microsoft Word fonts list shows the Theme Fonts, Recent Fonts, and All Fonts. Scroll down farther to see all the fonts available on your computer. This includes fonts that are built-in as well as fonts you’ve added, listed in alphabetical order. The fonts list also gives you a preview of what each font looks like.

Click on the font you wish to use. A triangle next to the font means there are further selections you can make.

Step 4. Change the Font Size

Go to the font-size button to change the font size.

Or, click the Increase Font Size or Decrease Font Size buttons to change the font size by increments.

Step 5. Change Other Text and Paragraph Settings

Use the other buttons on the ribbon to add emphasis (bold, italics, underline), change the font color, and apply other effects.

We’ve now changed the default font in Microsoft Word.

2. How to Replace the Default Font Based on Paragraph Style

By changing the font used for a paragraph style, the change is applied globally in your document for all text with that paragraph style. Use this if you want to change the default font for large sections of text.

Follow the steps on how to change the Microsoft Word default font for a paragraph style:

Step 1. Select the Text

Highlight text that’s representative of the paragraph style you want to re-format. Make sure it’s got the paragraph style you want to change.

In this example, I’ll replace the default font for the Normal paragraph style.

Step 2. Apply the Font Settings You Wish to Use

Follow the steps in Method 1 to change the font, font size, font color, and apply other settings. You may also want to change the paragraph settings, such as alignment, line spacing, etc.

Step 3. Apply the New Formatting to the Paragraph Style

With the cursor in the paragraph you’ve formatted, click on the Styles button on the ribbon. This opens the paragraph Styles selection.

The current paragraph style will be highlighted. In this case, it’s the Normal style. Right-click on the Normal style, then click on Update Normal to Match Selection.

All other paragraphs with the Normal style are updated with the new font and settings you made.

3. How to Change the Font Based on Paragraph Styles Button

This method has the same end-result as Method 2. It changes the default font for a specific paragraph style. The steps are slightly different, as you’ll see:

Step 1. Open the Styles Settings

Click on the Styles button on the ribbon. This displays the paragraph styles.

Step 2. Modify the Paragraph Style

Right-click on the style you wish to change. Click Modify…

The Modify Style dialog opens.

Change the font, font size, and other settings. The box shows a preview of what the paragraph will look like when the settings you chose are applied. If you’re happy with the way it looks, click OK.

The new font (and other settings) will be applied to all paragraphs with that paragraph style.

How to Add Fonts to Microsoft Word

Right out of the box, Microsoft Word comes with dozens of fonts built in. But what if you want to use a font and you don’t see it on the Microsoft Word fonts list?

In that case, you add the font to Microsoft Word. I’ll walk you through how to do that in this section:

Step 1. Find New Fonts

The first step is to find the font you want to use. There are many sources of custom fonts. One to consider is Envato Elements, where you can download an unlimited number of fonts for one small subscription price.

To find a font you like, log into your Envato Elements account.

On the search bar, click on the downward arrow, then select Fonts.

Type a keyword into the search bar, depending on what kind of font you’re looking for. Click the search icon. The most relevant results appear.

Refine the results by Categories, Spacing, Optimum Size, and Properties. You can also sort the results by popularity (Popular) and newness (New).

Click on a font image or name to see its details.

When you find a font you like, click on any of the Download buttons on the page.

The Add this file to a project dialog box pops up.

Select a project to add the font file to. Or, click Create new project to add it to a new project. For this example, I’ll add the font to my existing tutorial project. Click the Add & Download button.

The file manager opens (Finder, if you’re on macOS; File Explorer, if you’re on Windows). Specify where you want to save the font file on your computer. Click Save.

The font files are now saved on your computer as a zip file.

Double-click on the zip file to unzip it.

Double-click on the font file itself to open it. It’ll usually have an extension like OTF or TTF. Click Install Font.

This adds the font to your computer’s fonts library.

The new font should now appear in the All Fonts list in Microsoft Word. To confirm, click on the Fonts button on the ribbon and scroll down the list until you see the new font. If you don’t see it, you may have to restart your computer.

Now, follow any of the methods above to change the default font with the new one.

2 Types of Fonts

Now that you know how to add fonts to Microsoft Word and replace the default fonts in your document, it would help for you to know more about fonts. This will help you choose the best fonts for your Word document.

There are two basic types of fonts you can use in your documents:

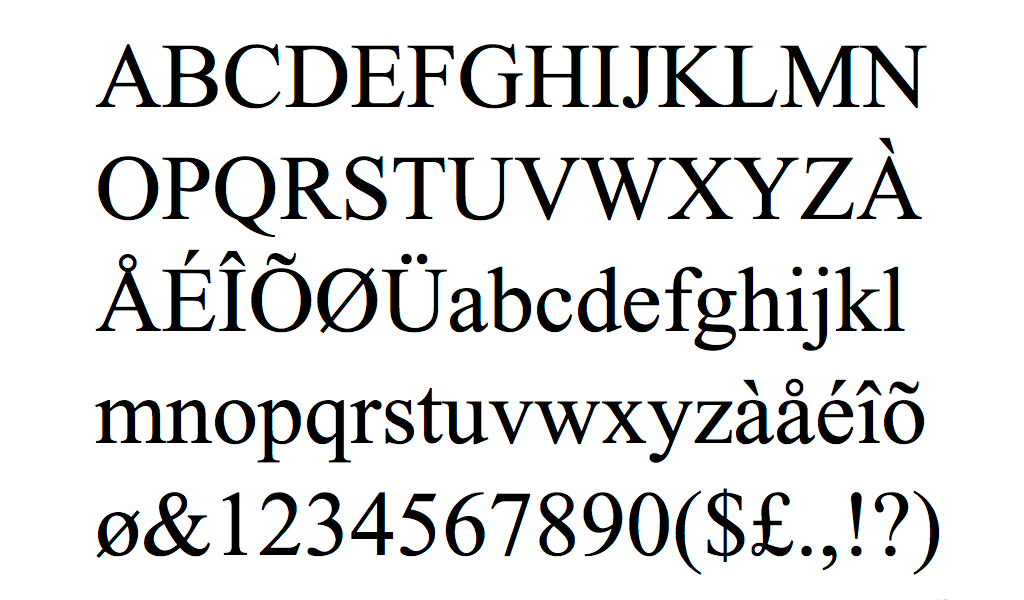

1. Serif Fonts

Serif fonts have little lines at the end of each stroke, like this:

Common examples of serif fonts include:

Various research studies have shown that, when it comes to printed matter, serif fonts are the easiest to read and result in the best comprehension.

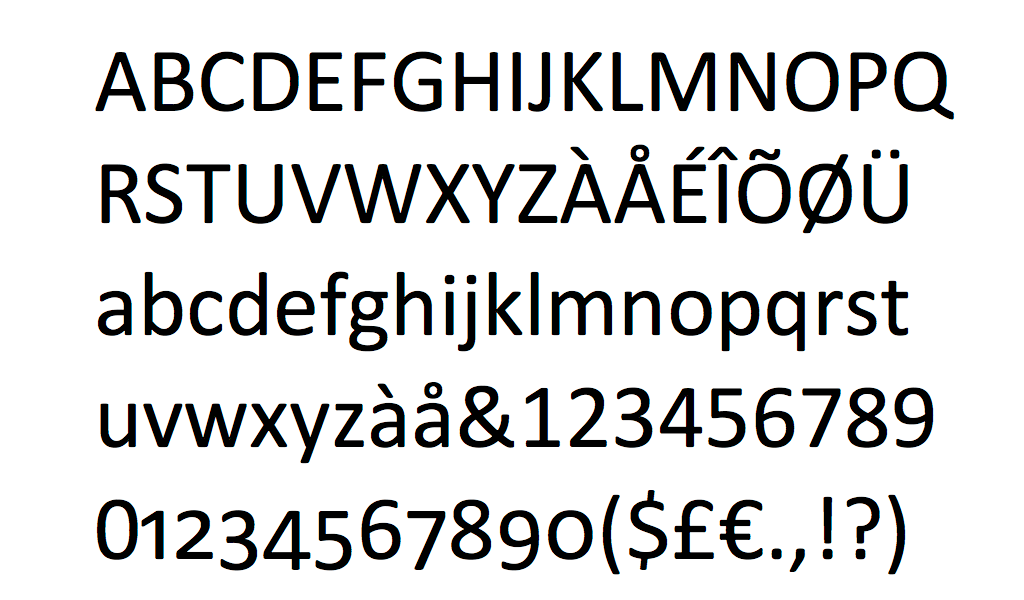

2. Sans Serif Fonts

As the name implies, sans serif fonts don’t have little lines at the end of each stroke (“sans” means “without” in French):

These are some of the most common sans serif fonts:

Citing research by the Software Usability Research Laboratory, Drew E. Whitman in his book Ca$vertising, noted that sans serif fonts are the most legible fonts to use on a computer screen. Specifically, Arial, Courier, and Verdana were considered the best for online reading.

But these studies were conducted when the resolution of online screens was still very low (below 100 dpi) compared to printed materials (300 dpi). As computer screen resolutions get closer to 300 dpi, serif fonts may prove to be legible both online and offline.

In the meantime, you can use both serif and sans serif fonts in one document—if you know how. Read on for tips on how to use combine fonts.

5 Tips on Using Typography Effectively in Your Word Documents

It’s easy to get carried away with fonts! You may find that having so many kinds of fonts available at your fingertips unleashes your creativity. Yet, as with most things, fonts can either enhance or sabotage your document.

Follow these tips to harness the power of typography:

1. Keep It Simple

When it comes to choosing fonts, legibility is of utmost importance. Sure, it’s easier than ever now for you to find the most creative and outrageous fonts. But if nobody can read your text, then they defeat their purpose. If you must use an ornate font, restrict it to one letter or word.

2. Stick to Two Fonts

A document that’s dripping with many different fonts makes it look amateurish, confusing, and incoherent. For best results, stick to a maximum of two fonts: one serif and one sans serif. (More on this in tip #4).

Remember, use formatting like bold, italics, underlines, different font sizes and colors to add emphasis and variety.

3. Match the Tone and Goals for the Document

Fonts have personality, so pick the ones that match the tone and goals of the document. For example, the fonts for a 16th birthday party invitation will be different from the ones in a financial business report.

When in doubt, pre-test the document. Show it to other people, especially those who are like the intended audience. Make sure they can comprehend the document, first, and that they respond favorably.

4. Choose Fonts Appropriate for the Document’s Intended Use

Whether the document will be printed out or consumed on a computer screen will also affect your choice of fonts.

If you’re making a printed document, use the sans serif font for headings and the serif font for body text. For a web-based document, switch it: Use a serif font for headings and sans serif for body text.

5. Use Handwritten, Cursive, and Decorative Fonts Sparingly

There are other font types that may not fit easily in either serif or sans serif categories. These include handwritten, cursive, and decorative fonts. Handwritten fonts, as the name says, look like they were written by hand. These are extremely popular and useful for adding a warm, personal touch on materials. They can range from casual to glamorous.

Cursive fonts are a kind of handwritten font that look like they’re written in longhand. Beware of using cursive and handwritten fonts because they can be difficult to read. Use them for short bits of text you want to emphasize.

You can easily find handwritten fonts in marketplaces like Envato Elements or GraphicRiver.

Decorative fonts have special effects or treatments. They may be serif or sans serif. And some handwritten fonts can be considered decorative as well.

Here’s a sampling of the decorative fonts available in Envato Elements:

5 Best Font Styles for 2020

Designers come up with new fonts every day. Below are five of the best and freshest Microsoft Word font styles we’re seeing for 2020, along with two fresh examples of each style:

1. Vintage Fonts

Vintage fonts evoke the aesthetic of times past. If you’re working on a document that’s about a specific time, you’re bound to find a font to match.

Anthique — Vintage Typeface

Anthique is reminiscent of handmade Victorian hand lettering but with a modern flavor. It works best for materials that relate to the early 1800s. The font includes three variations in TTF and OTF formats. It also supports multilingual characters.

Middle Class Script

Middle Class is a script font that’s evocative of the bold style of the ’60s and ’70s. It’s got a hand-drawn and layered style, and includes punctuation, common ligatures, and extra swashes (lines).

2. Brush Script Fonts

Brush script fonts are handwritten fonts that look like they were written with a brush, such as a calligraphy or a paintbrush. These are increasingly popular as brands want to add a personal touch to their materials.

Eberthany Brush Script

Eberthany is a modern brush script signature font that works for:

- social media posts

- logos

- wedding invitations

- labels

- quotes

- and more

It works best with software that supports OpenType fonts like Adobe Illustrator CS, Adobe Photoshop CC, Adobe InDesign, and Corel Draw.

Mistrully Brush Script

Mistrully is a stylish brush script that looks like natural handwriting. It comes with special swashes or handwritten lines that you can use to add emphasis. Mistrully works well for logos, social media posts, advertisements, product designs and labels, stationery, among others.

3. Font Duos

Font Duos take the guesswork out of choosing fonts that work well together. These two-for-one font packages are designed to complement each other. You only need to pick the font duo that aligns with your branding and the tone of the material you’re designing. Examples of font duos include:

Chiladepia — Font Duo

The Chiladepia Font Duo is made up of two handwritten fonts. One’s a cursive font and the other’s a sans serif font. This font duo would work well on a computer screen. Use the cursive font for titles or headers and the sans serif font for the rest of the document.

Perkin | Duo Font Pack

The Perkin Duo Font combines a bold sans serif and a serif font. The sans serif font is best for titles and headings, while the serif font works great for body text. This duo is ideal for printed materials.

4. 3D Decorative Fonts

3D decorative fonts look like they’re popping off the pages. These fonts are incredibly eye-catching. For that reason, they’re great for titles. But, they’re not the most legible fonts, so use them sparingly for short bits of text.

Ultra — Modern Font

If you’re creating a futuristic document, then consider the Ultra — Modern Font. It’s got a modern and futuristic style. This pack is actually made up of four font styles: regular, bold, 3D, and bold 3D. It also comes in both OTF and TTF formats.

Under Construction 3D Color Font

Under Construction is a stunning 3D decorative font to use on materials related to industry, construction, technology, and the like. Each letter looks like it floats on top of the page. It’s a color or SVG OpenType font, which works only in Photoshop CC 2017+, Illustrator CC 2018, and some Mac apps.

5. Tech Sans Serif Fonts

Tech sans serif fonts have gone a long way since the pixelized arcade fonts of the ‘80s. Many are also much more legible and modern. Below are two examples:

Azuria — Technology Science Font

The Azuria — Technology Science Font evokes technology, science, and outer space. Its metallic, 3D look would work well in video games, movie titles, and tech-related branding. The font includes all Latin letters from A-Z, numbers, and punctuation marks.

Cyborg — Futuristic Technology Typeface

Cyborg is another futuristic tech font. Inspired by science fiction, it’s perfect for titles related to space, technology, and science. It comes in OTF, TTF, and WOFF formats.

Put Fonts to Work in Your Microsoft Word Document Today

As you’ve learned in this article, you don’t need to stick to the default fonts in Microsoft Word. Follow the steps outlined above to replace the default fonts with ones that are more appropriate to your document.

Now that you understand how to add fonts to Microsoft Word, you’re ready to start taking advantage of the unique look a professionally designed font can give your documents.

At Envato Elements and GraphicRiver we’ve got some of the best Microsoft Word fonts available. Take a look at our Microsoft Word fonts list today. Download your favorites for your next MS Word document.

Microsoft Word is the global standard for word processing. At the same time, it’s one of the most maddening applications to master, which is why this Geek School series is all about learning how to format documents in Word.

Word 2013 and a Little Perspective

Microsoft is far more than a typical staid word processor. Word is one of the most affordable and closest things you can get to your very own printing press. In fact, it is for all With Word, you can write textbooks, create full magazine and newspaper layouts with graphics, write a novel with indices, and much, much more. You can do in mere hours, what twenty years ago might have taken an entire editorial team days or even weeks.

Microsoft Word completely eliminates the aggravation of typos (in theory at least). There is no need to retype whole chapters in order to add or rearrange content. Instead you can add, move, or even remove complete sentence, paragraphs, and chapters in mere seconds!

Of course, we take this power for granted but we can tell you, it really beats using a typewriter (let alone movable type) – making a mistake using a typewriter meant stopping what you were doing, rolling the platen up to better expose your typo, and then either using an eraser to remove the offending characters, or carefully dabbing on White-Out and patiently blowing it dry. Then, of course, you’d have to roll the platen back to the line you were typing on, taking further care to make sure it all lined up perfectly.

If you can imagine how many daily typing errors you make then you can probably get an idea of how long it took to produce even simple documents. Needless-to-say, it paid to be accurate, and unless you were a really good typist, typing an essay or book report, could be a long arduous process. And forget about adding pictures into your document. Doing that kind of stuff at home was nearly impossible. Oh sure, you could include your illustrations and photos and then refer to them, but it wasn’t as simple and elegant as cut-copy-paste we’ve become so accustomed to.

Nevertheless, all this power and control does arrive with a fairly steep learning curve. It can be a pain to get the hang of and be fluent in effectively formatting eye-catching documents. Luckily, that’s where we come in – with How-To Geek School’s Formatting Documents with Microsoft Word 2013.

What We Will Cover

This series aims to introduce you to a large swath of Word 2013’s document formatting features through five lessons.

In this lesson, we first cover some Word basics like the Ribbon and page structure like tabs, margins, and indents. Additionally, we show you how to manipulate formatting marks or simply turn them on/off. Our first lesson concludes with an exploration of fonts, and finally templates.

Lesson 2 begins with paragraphs, specifically alignment, indentation, and line spacing. After that we move on to shading and borders, and then lists (bulleted, numbered, and multilevel). We’ll also briefly touch upon AutoCorrect options.

After that, Lesson 3 begins with a lengthy exploration of tables (inserting, drawing, formatting, etc.) and then we dive into other formatting options, including links, headers, footers, equations, and symbols.

Lesson 4’s primary focus will be illustrations and multimedia such as pictures, shapes, WordArt, and more. We move on from there to briefly cover working with more than one language.

Finally, in Lesson 5, we wrap up with styles and themes, covering the gamut, new styles, inspecting styles, managing and modifying, and lastly themes.

Before we do all that however, let’s take some time to orient ourselves with Word’s anatomy and layout.

The Ribbon

As you may be familiar, Microsoft employs a “Ribbon” interface throughout their products. These ribbons are prominent in Office and Windows 8 (File Explorer and WordPad).

Here we see the Ribbon in Word 2013, the application we’ll be using for all our work.

The Ribbon is further subdivided into tabs (Home, Insert, Design, etc.) and each tab is further broken down into sections (Clipboard, Font, Paragraph, etc.).

Each of these sections can be expanded by clicking the small arrow in the lower-right corner.

Here, if we click on the arrow on the “Font” section, it opens to the trusty “Font” dialog:

While some menus may open to dialogs, others may spawn panes that slide out from one side of the screen. Also, if you use a computer with a lower resolution screen and need more screen real estate, you can click the small arrow to the very far lower-right corner of the ribbon.

This will cause the Ribbon to collapse, giving you more vertical space to work with. To get the Ribbon back, simply click on a tab and it will spring back into view (you can pin it if you want it to stay open).

Alternatively, you can quickly hide/unhide the Ribbon by typing “CTRL + F1.”

Home is Where Word’s Heart is

We’ll take some time before diving into actual document formatting, to talk about the “Home” tab. Even if you never touch another part of Word for the rest of your life (fairly impossible but still), the Home tab contains its most essential functions and is vital to formatting your documents consistently well.

See here how the “Home” tab has a total of five sections: “Clipboard,” “Font,” “Paragraph,” “Styles,” and “Editing.”

Clipboard

“Clipboard” functions are pretty rudimentary; you should know them by now: cut, copy, paste. Most likely you use right-click menus to do many of your cut-copy-paste functions, or keyboard shortcuts: “CTRL + X”, “CTRL + C”, “CTRL + V,” respectively.

Opening the “Clipboard” pane however, reveals a goldmine of functionality that can actually prove quiet useful when formatting documents. The Word clipboard collects everything you cut or copy for later use. This is particularly useful if you need to paste several distinct passages of text and/or images throughout your document. You can simply place your pointer at the correct insertion point, open the “Clipboard” viewer and select the piece you want to paste.

Font

The “Font” section and applicable dialog should be pretty familiar to the majority of Word users. Even if you’re not a Word pro, you’ve used the font functions in Word every time you create a document. Each time you bold or italicize something, you’re employing font functions. So knowing your way around the “Font” section and dialog is an excellent approach to mastering Word’s formatting bells and whistles.

We’ll go further into depth on fonts and typefaces in this lesson, for now, take a little time to familiarize yourself with its various functions.

Paragraph

Important also is the “Paragraph” section, which lets you set critical formatting features such as indenting, line spacing, and page breaks. Further, adjusting paragraph controls lets you play with borders, shading, and turn paragraph marks on or off. We’ll talk more about this in Lesson 2.

Styles

Styles are a great way to manage the way your entire document’s headers, titles, and text quickly and easily. Rather than going through a document and adding or changing headers one by one, you can simply apply a style, and then make changes to it using the “Styles” section. We’ll go into styles a great deal more in our final lesson of this series.

The Page

Your page is where all the magic happens, it’s where you compose your masterpieces and as such, knowing your way around is essential. Let’s dive in by turning on the “Ruler” and then explain how to set tabs and margins.

To turn on the ruler, we’ll first click the “View” tab and in the “Show” section, check the box next to “Ruler.” Note the horizontal and vertical rulers that appear along the page edges.

If you want to work according to another measurement system, you can change it from “File” -> “Options” -> “Advanced.”

Tabs

With the ruler on, we can cover how to use tabs and set margins. The ruler is used to show to show the positions of tab stops and margins.

Tabs are used to position text by using the “Tab” key. This works better than spacing everything manually, and with most fonts, tabs are the surest way to make sure everything lines up properly.

Microsoft Word sets tabs by default to ½-inch intervals. When you hit “Tab,” the insertion point will automatically jump right (½-inch per tab).

You set tabs by clicking on the ruler to indicate where you want to place them. You’ll see a vertical dotted line allowing your more precise control over where they go.

You can set tabs in any section of the document, meaning the top of the page can have different tabs than the middle or the bottom. Basically, you can a different tabbing scheme on each and every line of your document if you need or desire.

Types of Tabs

There are several different kinds of tabs you can use. To pick the type, click the tab selector located at the far left-hand side of the screen as shown below.

Here we see a left tab, note all the text is aligned to the left.

And similarly, a right tab:

A center tab:

A decimal tab allow you to create columns of numbers and easily line them up by decimal point:

A vertical bar tab, which doesn’t act like a tab, allows you to demarcate text. It looks the same as if you typed | however the advantage is that you can grab the “bar tab” in the ruler and move them together.

You can exert more control over tabs by double-clicking on any one to bring up the tabs dialog window. Note here you can have more precise control over tab stop positions, alignment, and clearing them.

Margins

You can see your margins by making sure Word is viewed in “Print Layout.”

Here in this example, we see our left margin is set at two inches and our left is set at four inches, giving us two inches of horizontal printable area. The margin indicators are the bottom arrows, while top arrow is a hanging indent, which we’ll cover in the very next section.

On a normal document, the left and right margins default to one-inch and 6 ½ inches. This means on a regular 8.5 x 11 sheet of paper, you will have one-inch margins where print will not appear, giving you 6.5 inches of horizontal printable area.

To move margins and the hanging indent, hover over each one with the mouse pointer until it changes to arrows and then drag them to the size you desire.

If you simply grab the left margin, it will leave the hanging indent behind.

And on that note, let’s briefly discuss indents in a bit more detail.

Indents

Indents are used to position the paragraph with margins or within the columns in a table.

You can tweak your margins further depending on what you’re writing. For example, you can create a “first line indent.” This is more of an old school style wherein the first line of each paragraph will be indented.

This is a more traditional way of formatting paragraphs, allowing you to denote where new paragraphs begin in a single-spaced document. Today, text is usually formatted in a block style with a double space between paragraphs.

A second line, or “hanging indent,” will automatically indent every line after the first one. One confusing part with indents is you can move them outside of the margin, which is counterintuitive unless you consider that a printer can print outside the margins, and is limited only by the width of the paper.

There’s not a whole lot to master when it comes to tabs, margins, and indents. That said, it pays to understand how they work so you can get more precise results in your documents. And it gives you a better understanding of why a documents looks the way it does or more importantly, why it may not look the way you want it to look.

Formatting marks

Before we proceed any further, we should point out that you might be noticing now that in some of our screenshots, there are formatting marks that show paragraphs, spaces, tabs, and others. To see the tabs and other text-formatting marks in the document select the ¶ (paragraph) symbol here on the “Paragraph” section on the “Home” tab.

To choose which formatting marks are seen, you can select them in Word “Options.” To open the options dialog, first click on the “File” tab and then choose “Options.” Finally, under “Display” you will see that you can select formatting options that always appear.

For example, if you want to turn off all the formatting marks except paragraphs and spaces, you would select only those two. Then you can turn off all or individual formatting marks in the “Paragraph” section.

Formatting marks are very important for creating clean, consistently formatted documents and they don’t show up in the final, printed document, plus you can turn them on or off as needed, so learn to use them to your advantage.

Fonts vs. Typefaces

Typefaces and fonts will be a routine part of your daily document formatting unless you’re happy with one single font for every document you write. Good font use is very important as it can allow you to better express yourself and get your point across. For that reason, you want to at least understand the very basics of how they work and what font is appropriate where and why.

For the sake of clarification, a “typeface” is basically the way a collection of letters, numbers, and symbols looks across its entirety. Here we see the Times New Roman typeface, which will have the same characteristics no matter which font you use. In other words, Times looks like Time, whether it is bolded, italicized, or whatever formatting you apply to it.

A font may be understood as the entire collection of typefaces. For example, Times New Roman and all its various forms (bold, italic, bold italic) is a “font family.” Each of the variations (regular, bold, italic, and bold italic) within the family is a font:

For the sake of simplicity, rather than split hairs and confuse you with talk of typefaces and fonts, we’ll just refer to everything type-related as a font.

Serif fonts

There are two types of fonts you should understand.

First, there are so-called serif fonts; serifs are those little bits that stick out from a letter as in the example below.

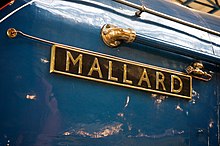

In many cases, a serif font will look best in formal of official documents. One of those most immediately identifiable and iconic examples of a serif font is seen on the New York Times masthead:

Sans serif

Conversely, a sans serif font will obviously not have serifs, hence the “sans” part. Here you see the Arial font, which is one of Windows’ default fonts.

Sans serif fonts are widely used in advertising and logos because they often tend to look new and modern. Without a doubt the most notable sans serif font is Helvetica, upon which Arial is obviously based. You can find dozens of examples of Helvetica-derived fonts in modern culture. Check out Microsoft, Target, and Panasonic for just a few examples.

You can add different fonts to Windows, and by extension Word, by downloading them from the web.

If you want to read up more about typefaces and fonts, Microsoft provides more information its typography homepage.

Point size

Point size relates to the size of the font, leading, and other page items. It is not connected to any established unit of measurement. In typography, a point is the smallest whole unit of measurement.

For most fonts in Word, the smallest point size is 8 points tall. The smallest lines and other graphic objects can have is a point size of 1. Here are some example of various point sizes:

Font Styles and Effects

You can apply various font styles and effects from the “Font” tab on the “Home” ribbon.

You can access further font effects from the full font dialog accessible by clicking the arrow in the bottom right corner.

You have a whole range of effects, including colors and different underline styles you can apply.

Before we end this lesson, we should take a moment to briefly acquaint you with templates, since they can often make short work of complex layouts.

Templates are pre-configured documents, like a resume or business cards that you can use to speed creating forms. There are templates for pretty much anything you can think of.

The goal of Microsoft Word is twofold: (1) provide sets of themes and styles so that the Word user can create professional-looking documents and (2) give the user the ability to create documents of graphic-designer quality by providing tools and pre-configured set of objects from which the user can select.

When you open Microsoft Word or click on the “New” from the “File” tab, the first screen it shows you are the templates available to you, either already included with the program, or available for quick download. If you don’t immediately see what you want, try “suggested searches” or use the search box.

Right-click on any template and you can “Preview” or “Create” the template. You can also pin a preferred template so it is always available at the top of the list.

Creating a template will cause it to open if it is stored locally on your computer, or it will download if it isn’t. Note that some these templates, such as the gift certificate pictured below are offered by third-party sites, so they may not all be free.

If you decide you want to purchase a third-party template, you will be provided with further instructions on how to do so.

After you pick a template, it will open as a new document, and you can fill it in and tweak it to your liking. We see here the template for the “Basic Resume.”

Note how Word will automatically fill in your name and the template provides instructions on how to use it. In reality, this template is really nothing more than a table (discussed in Lesson 3) with a Theme (discussed in Lesson 5) applied to it.

When you are done filling out the template, you can then save it as a new document. You can also take a template, make changes to it, and then save it as a new template. Let’s say for example, that you wanted to apply a different style to our “Basic Resume.” You’d simply need to open the template, affect the changes you want, and then save it as a new template.

There’s a whole lot to discover with templates. Best of all, you don’t have to worry about creating every single document on your own. Need a quick business card or invitations to your retirement party? Word templates make quick work of a lot of formatting headaches, leaving you time to actually design something you’ll be happy with!

Coming up Next…

That concludes our lesson for today, you should now have a fairly firm grasp on Word’s layout, tabs, margins, indents, fonts, and templates.

Tomorrow we’ll go over how to change the appearance and behavior of paragraphs on your pages, shading and borders, as well as introduce you to lists and all their various parts!

READ NEXT

- › HoloLens Now Has Windows 11 and Incredible 3D Ink Features

- › How Long Do CDs and DVDs Last?

- › Google Chrome Is Getting Faster

- › This New Google TV Streaming Device Costs Just $20

- › How to Adjust and Change Discord Fonts

- › Liquid Metal vs. Thermal Paste: Is Liquid Metal Better?

From left to right: a Ming serif typeface with serifs in red, a Ming serif typeface and an East Asian gothic sans-serif typeface

In typography and lettering, a sans-serif, sans serif, gothic, or simply sans letterform is one that does not have extending features called «serifs» at the end of strokes.[1] Sans-serif typefaces tend to have less stroke width variation than serif typefaces. They are often used to convey simplicity and modernity or minimalism.

Sans-serif typefaces have become the most prevalent for display of text on computer screens. On lower-resolution digital displays, fine details like serifs may disappear or appear too large. The term comes from the French word sans, meaning «without» and «serif» of uncertain origin, possibly from the Dutch word schreef meaning «line» or pen-stroke.[2] In printed media, they are more commonly used for display use and less for body text.

Before the term «sans-serif» became common in English typography, a number of other terms had been used. One of these outmoded terms for sans-serif was gothic, which is still used in East Asian typography and sometimes seen in typeface names like News Gothic, Highway Gothic, Franklin Gothic or Trade Gothic.

Sans-serif typefaces are sometimes, especially in older documents, used as a device for emphasis, due to their typically blacker type color.

Classification[edit]

For the purposes of type classification, sans-serif designs are usually divided into three or four major groups, the fourth being the result of splitting the grotesque category into grotesque and neo-grotesque.[3][4]

Grotesque[edit]

This group features most of the early (19th century to early 20th) sans-serif designs. Influenced by Didone serif typefaces of the period and sign painting traditions, these were often quite solid, bold designs suitable for headlines and advertisements. The early sans-serif typefaces often did not feature a lower case or italics, since they were not needed for such uses. They were sometimes released by width, with a range of widths from extended to normal to condensed, with each style different, meaning to modern eyes they can look quite irregular and eccentric.[5][6] Grotesque typefaces have limited variation of stroke width (often none perceptible in capitals). The terminals of curves are usually horizontal, and many have a spurred «G» and an «R» with a curled leg. Capitals tend to be of relatively uniform width. Cap height and ascender height are generally the same to produce a more regular effect in texts such as titles with many capital letters, and descenders are often short for tighter line spacing.[7] Most avoid having a true italic in favor of a more restrained oblique or sloped design, although at least some sans-serif true italics were offered.[8][9]

Examples of grotesque typefaces include Akzidenz-Grotesk, Venus, News Gothic, Franklin Gothic and Monotype Grotesque. Akzidenz Grotesk Old Face, Knockout, Grotesque No. 9 and Monotype Grotesque are examples of digital fonts that retain more of the eccentricities of some of the early sans-serif types.[10][11][12][13]

According to Monotype, the term «grotesque» originates from Italian: grottesco, meaning «belonging to the cave» due to their simple geometric appearance.[14] The term arose because of adverse comparisons that were drawn with the more ornate Modern Serif and Roman typefaces that were the norm at the time.[15]

Neo-grotesque[edit]

Neo-grotesque designs appeared in the mid-twentieth century as an evolution of grotesque types. They are relatively straightforward in appearance with limited stroke width variation. Similar to grotesque typefaces, neo-grotesques often feature capitals of uniform width and a quite ‘folded-up’ design, in which strokes (for example on the ‘c’) are curved all the way round to end on a perfect horizontal or vertical. Helvetica is an example of this. Unlike earlier grotesque designs, many were issued in large families from the time of release.

Neo-grotesque type began in the 1950s with the emergence of the International Typographic Style, or Swiss style. Its members looked at the clear lines of Akzidenz-Grotesk (1898) as an inspiration for designs with a neutral appearance and an even colour on the page. In 1957 the release of Helvetica, Univers, and Folio, the first typefaces categorized as neo-grotesque, had a strong impact internationally: Helvetica came to be the most used typeface for the following decades.[16][b]

Other, later neo-grotesques include Unica, Imago and Rail Alphabet, and in the digital period Arial, Acumin, San Francisco and Roboto.[18][19][20][21][22][23]

Geometric[edit]

Geometric sans-serif typefaces are based on geometric shapes, like near-perfect circles and squares.[24] Common features are a nearly-circular capital ‘O’, sharp and pointed uppercase ‘N’ vertices, and a «single-storey» lowercase letter ‘a’. The ‘M’ is often splayed and the capitals of varying width, following the classical model.

The geometric sans originated in Germany in the 1920s.[25] Two early efforts in designing geometric types were made by Herbert Bayer and Jakob Erbar, who worked respectively on Universal Typeface (unreleased at the time but revived digitally as Architype Bayer) and Erbar (circa 1925).[26] In 1927 Futura, by Paul Renner, was released to great acclaim and popularity.[27]

Geometric sans-serif typefaces were popular from the 1920s and 1930s due to their clean, modern design, and many new geometric designs and revivals have been developed since.[c] Notable geometric types of the period include Kabel, Semplicità, Bernhard Gothic, Nobel and Metro; more recent designs in the style include ITC Avant Garde, Brandon Grotesque, Gotham, Avenir, Product Sans and Century Gothic. Many geometric sans-serif alphabets of the period, such as those authored by the Bauhaus art school (1919–1933) and modernist poster artists, were hand-lettered and not cut into metal type at the time.[29]

A separate inspiration for many types described «geometric» in design has been the simplified shapes of letters engraved or stenciled on metal and plastic in industrial use, which often follow a simplified structure and are sometimes known as «rectilinear» for their use of straight vertical and horizontal lines. Designs which have been called geometric in principles but not descended from the Futura, Erbar and Kabel tradition include Bank Gothic, DIN 1451, Eurostile and Handel Gothic, along with many of the typefaces designed by Ray Larabie.[30][31]

Humanist[edit]

Humanist sans-serif typefaces take inspiration from traditional letterforms, such as Roman square capitals, traditional serif typefaces and calligraphy. Many have true italics rather than an oblique, ligatures and even swashes in italic. One of the earliest humanist designs was Edward Johnston’s Johnston typeface from 1916, and, a decade later, Gill Sans (Eric Gill, 1928).[32] Edward Johnston, a calligrapher by profession, was inspired by classic letter forms, especially the capital letters on the Column of Trajan.[33]

Humanist designs vary more than gothic or geometric designs.[34] Some humanist designs have stroke modulation (strokes that clearly vary in width along their line) or alternating thick and thin strokes. These include most popularly Hermann Zapf’s Optima (1958), a typeface expressly designed to be suitable for both display and body text.[35] Some humanist designs may be more geometric, as in Gill Sans and Johnston (especially their capitals), which like Roman capitals are often based on perfect squares, half-squares and circles, with considerable variation in width. These somewhat architectural designs may feel too stiff for body text.[32] Others such as Syntax, Goudy Sans and Sassoon Sans more resemble handwriting, serif typefaces or calligraphy.

Frutiger, from 1976, has been particularly influential in the development of the modern humanist sans genre, especially designs intended to be particularly legible above all other design considerations. The category expanded greatly during the 1980s and 1990s, partly as a reaction against the overwhelming popularity of Helvetica and Univers and also due to the need for legible computer fonts on low-resolution computer displays.[36][37][38][39] Designs from this period intended for print use include FF Meta, Myriad, Thesis, Charlotte Sans, Bliss, Skia and Scala Sans, while designs developed for computer use include Microsoft’s Tahoma, Trebuchet, Verdana, Calibri and Corbel, as well as Lucida Grande, Fira Sans and Droid Sans. Humanist sans-serif designs can (if appropriately proportioned and spaced) be particularly suitable for use on screen or at distance, since their designs can be given wide apertures or separation between strokes, which is not a conventional feature on grotesque and neo-grotesque designs.

Other or mixed[edit]

Rothbury, an early modulated sans-serif typeface from 1915. The strokes vary in width considerably.

Due to the diversity of sans-serif typefaces, many do not exactly fit into the above categories. For example, Neuzeit S has both neo-grotesque and geometric influences, as does Hermann Zapf’s URW Grotesk. Whitney blends humanist and grotesque influences, while Klavika is a geometric design not based on the circle. Sans-serif typefaces intended for signage, such as Transport and Highway Gothic (both used on road signs), may have unusual features to enhance legibility and differentiate characters, such as a lower-case ‘L’ with a curl or ‘i’ with serif under the dot.[40]

Modulated sans-serifs[edit]

A particular subgenre of sans-serifs is those such as Rothbury, Britannic, Radiant, and National Trust with obvious variation in stroke width. These have been called ‘modulated’ or ‘stressed’ sans-serifs. They are nowadays[when?] often placed within the humanist genre, although they predate Johnston which started the modern humanist genre. These may take inspiration from sources outside printing such as brush lettering or calligraphy.[41]

History[edit]

Letters without serifs have been common in writing across history, for example in casual, non-monumental epigraphy of the classical period. However, Roman square capitals, the inspiration for much Latin-alphabet lettering throughout history, had prominent serifs. While simple sans-serif letters have always been common in «uncultured» writing and sometimes even in epigraphy, such as basic handwriting, most artistically-authored letters in the Latin alphabet, both sculpted and printed, since the Middle Ages have been inspired by fine calligraphy, blackletter writing and Roman square capitals. As a result, printing done in the Latin alphabet for the first three hundred and fifty years of printing was «serif» in style, whether in blackletter, roman type, italic or occasionally script.

The earliest printing typefaces which omitted serifs were not intended to render contemporary texts, but to represent inscriptions in Ancient Greek and Etruscan. Thus, Thomas Dempster’s De Etruria regali libri VII (1723), used special types intended for the representation of Etruscan epigraphy, and in c. 1745, the Caslon foundry made Etruscan types for pamphlets written by Etruscan scholar John Swinton.[42] Another niche used of a printed sans-serif letterform from 1786 onwards was a rounded sans-serif script typeface developed by Valentin Haüy for the use of the blind to read with their fingers.[43][44][45]

-

A 12th-century[46] Medieval Latin inscription in Italy featuring sans-serif capitals

Developing popularity[edit]

An inscription at the neoclassical grotto at Stourhead in the west of England dated to around 1748 (replica shown),[d] one of the first to use sans-serif letterforms since the classical period[49][50][e][f]

An early 1810 «neoclassical» use of sans-serif capitals to represent antiquity, by William Gell[45][51]

Towards the end of the eighteenth century neoclassicism led to architects increasingly incorporating ancient Greek and Roman designs in contemporary structures. Historian James Mosley, the leading expert on early revival of sans-serif letters, has found that architect John Soane commonly used sans-serif letters on his drawings and architectural designs.[48][52] Soane’s inspiration was apparently the inscriptions dedicating the Temple of Vesta in Tivoli, Italy, with minimal serifs.[48] These were then copied by other artists, and in London sans-serif capitals became popular for advertising, apparently because of the «astonishing» effect the unusual style had on the public. The lettering style apparently became referred to as «old Roman» or «Egyptian» characters, referencing the classical past and a contemporary interest in Ancient Egypt and its blocky, geometric architecture.[48][53]

Mosley writes that «in 1805 Egyptian letters were happening in the streets of London, being plastered over shops and on walls by signwriters, and they were astonishing the public, who had never seen letters like them and were not sure they wanted to».[42] A depiction of the style (as an engraving, rather than printed from type) was shown in the European Magazine of 1805, described as «old Roman» characters.[49][54] However, the style did not become used in printing for some more years.[g] (Early sans-serif signage was not printed from type but hand-painted or carved, since at the time it was not possible to print in large sizes. This makes tracing the descent of sans-serif styles hard, since a trend can arrive in the dated, printed record from a signpainting tradition which has left less of a record or at least no dates.)

The inappropriateness of the name was not lost on the poet Robert Southey, in his satirical Letters from England written in the character of a Spanish aristocrat.[56][57] It commented: «The very shopboards must be … painted in Egyptian letters, which, as the Egyptians had no letters, you will doubtless conceive must be curious. They are simply the common characters, deprived of all beauty and all proportion by having all the strokes of equal thickness, so that those which should be thin look as if they had the elephantiasis.»[58][48] Similarly, the painter Joseph Farington wrote in his diary on 13 September 1805 of seeing a memorial[h] engraved «in what is called Egyptian Characters«.[59][48]

Around 1816, the Ordnance Survey began to use ‘Egyptian’ lettering, monoline sans-serif capitals, to mark ancient Roman sites. This lettering was printed from copper plate engraving.[49][45]

Entry into printing[edit]

Around 1816, William Caslon IV produced the first sans-serif printing type in England for the Latin alphabet, a capitals-only face under the title ‘Two Lines English Egyptian’, where ‘Two Lines English’ referred to the typeface’s body size, which equals to about 28 points.[60][61] Although it is known from its appearances in the firm’s specimen books, no uses of it from the period have been found; Mosley speculates that it may have been commissioned by a specific client.[62][i]

A second hiatus in interest in sans-serif appears to have lasted for about twelve years, until Vincent Figgins’ foundry of London issued a new sans-serif in 1828.[64][65][66] David Ryan felt that the design was «cruder but much larger» than its predecessor, making it a success.[67] Thereafter sans-serif capitals rapidly began to be issued from London typefounders.

Much imitated was the Thorowgood «grotesque» face of the early 1830s. This was arrestingly bold and highly condensed, quite unlike the classical proportions of Caslon’s design, but very suitable for poster typography and similar in aesthetic effect to the (generally wider) slab serif and «fat faces» of the period. It also added a lower-case. The term «grotesque» comes from the Italian word for cave, and was often used to describe Roman decorative styles found by excavation, but had long become applied in the modern sense for objects that appeared «malformed or monstrous».[7] The term «grotesque» became commonly used to describe sans-serifs.

Similar condensed sans-serif display typefaces, often capitals-only, became very successful.[48] Sans-serif printing types began to appear thereafter in France and Germany.[68][69]

-

Specimen by William Caslon IV showing his Two Lines English Egyptian sans-serif, the first general-purpose «sans-serif» printing type ever.[70] Cut in only one size, it was apparently not promoted with any prominence.

-

The largest type in this image is the second sans-serif type known, published by Figgins in 1828.[66]

-

Sample image of condensed sans-serifs from the Figgins foundry of London in an 1845 specimen-book. Much less influenced by classical models than the earliest sans-serif lettering, these faces became extremely popular for commercial use.[71]

A few theories about early sans-serifs now known to be incorrect may be mentioned here. One is that sans-serifs are based on either «fat face typefaces» or slab-serifs with the serifs removed.[72][73] It is now known that the inspiration was more classical antiquity, and sans-serifs appeared before the first dated appearance of slab-serif letterforms in 1810.[45] The Schelter & Giesecke foundry also claimed during the 1920s to have been offering a sans-serif with lower-case by 1825.[74][75] Wolfgang Homola dated it in 2004 to 1882 based on a study of Schelter & Giesecke specimens;[76] Mosley describes this as «thoroughly discredited»; even in 1986 Walter Tracy described the claimed dates as «on stylistic grounds … about forty years too early».[45][77]

Sans-serif lettering and typefaces were popular due to their clarity and legibility at distance in advertising and display use, when printed very large or small. Because sans-serif type was often used for headings and commercial printing, many early sans-serif designs did not feature lower-case letters. Simple sans-serif capitals, without use of lower-case, became very common in uses such as tombstones of the Victorian period in Britain.

The first use of sans-serif as a running text has been proposed to be the short booklet Feste des Lebens und der Kunst: eine Betrachtung des Theaters als höchsten Kultursymbols (Celebration of Life and Art: A Consideration of the Theater as the Highest Symbol of a Culture),[78] by Peter Behrens, in 1900.[79]

-

Simple sans-serif capitals on a late-nineteenth-century memorial, London

-

Italic capitals from the Caslon specimen of 1841

-

Sans-serif type in both upper- and lower-case on a 1914 poster

Twentieth-century sans-serifs[edit]

Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries sans-serif types were viewed with suspicion by many printers, especially those of fine book printing, as being fit only for advertisements (if that), and to this day[when?] most books remain printed in serif typefaces as body text.[81] This impression would not have been helped by the standard of common sans-serif types of the period, many of which now seem somewhat lumpy and eccentrically-shaped. In 1922, master printer Daniel Berkeley Updike described sans-serif typefaces as having «no place in any artistically respectable composing-room.»[82] By 1937 he stated that he saw no need to change this opinion in general, though he felt that Gill Sans and Futura were the best choices if sans-serifs had to be used.[83]

Through the early twentieth century, an increase in popularity of sans-serif typefaces took place as more artistic sans-serif designs were released. While he disliked sans-serif typefaces in general, the American printer J.L. Frazier wrote of Copperplate Gothic in 1925 that «a certain dignity of effect accompanies … due to the absence of anything in the way of frills», making it a popular choice for the stationery of professionals such as lawyers and doctors.[84] As Updike’s comments suggest, the new, more constructed humanist and geometric sans-serif designs were viewed as increasingly respectable, and were shrewdly marketed in Europe and America as embodying classic proportions (with influences of Roman capitals) while presenting a spare, modern image.[85][86][87][88][89] Futura in particular was extensively marketed by Bauer and its American distribution arm by brochure as capturing the spirit of modernity, using the German slogan «die Schrift unserer Zeit» («the typeface of our time») and in English «the typeface of today and tomorrow»; many typefaces were released under its influence as direct clones, or at least offered with alternate characters allowing them to imitate it if desired.[90][91][92][93]

Grotesque sans-serif revival and the International Typographic Style[edit]

A 1969 poster exemplifying the trend of the 1950s and 1960s: solid red colour, simplified images and the use of a grotesque face. This design, by Robert Geisser, appears to use Helvetica.

In the post-war period, an increase of interest took place in «grotesque» sans-serifs.[94][95][96] Writing in The Typography of Press Advertisement (1956), printer Kenneth Day commented that Stephenson Blake’s eccentric Grotesque series had returned to popularity for having «a personality sometimes lacking in the condensed forms of the contemporary sans cuttings of the last thirty years.»[28] Leading type designer Adrian Frutiger wrote in 1961 on designing a new face, Univers, on the nineteenth-century model: «Some of these old sans-serifs have had a real renaissance within the last twenty years, once the reaction of the ‘New Objectivity’ had been overcome. A purely geometrical form of type is unsustainable.»[97] Of this period in Britain, Mosley has commented that in 1960 «orders unexpectedly revived» for Monotype’s eccentric Monotype Grotesque design: «[it] represents, even more evocatively than Univers, the fresh revolutionary breeze that began to blow through typography in the early sixties» and «its rather clumsy design seems to have been one of the chief attractions to iconoclastic designers tired of the … prettiness of Gill Sans».[42][98]

By the 1960s, neo-grotesque typefaces such as Univers and Helvetica had become popular through reviving the nineteenth-century grotesques while offering a more unified range of styles than on previous designs, allowing a wider range of text to be set artistically through setting headings and body text in a single family.[5][99][100][101][102] The style of design using asymmetric layouts, Helvetica and a grid layout extensively has been called the Swiss or International Typographic Style.

Other names[edit]

Three sans-serif «italics». News Gothic has an oblique.[j] Gothic Italic no. 124, an 1890s grotesque, has a true italic resembling Didone serifs of the period.[8] Seravek, a modern humanist typeface, has a more organic italic which is less folded-up.

Early[edit]

- Egyptian: The name of Caslon’s first general-purpose sans-serif printing type; also documented as being used by Joseph Farington to describe seeing the sans-serif inscription on John Flaxman’s memorial to Isaac Hawkins Brown in 1805,[48] though today[when?] the term is commonly used to refer to slab serif, not sans-serif.

- Antique: Particularly popular in France;[42] some families such as Antique Olive, still carry the name.

- Grotesque: Popularised by William Thorowgood of Fann Street Foundry from around 1830.[7][64][74] The name came from the Italian word ‘grottesco’, meaning ‘belonging to the cave’. In Germany, the name became Grotesk.

- Doric: Used by the Caslon foundry in London

- Gothic: Popular with American type founders. Perhaps the first use of the term was due to the Boston Type and Stereotype Foundry, which in 1837 published a set of sans-serif typefaces under that name. It is believed that those were the first sans-serif designs to be introduced in America.[103] The term probably derived from the architectural definition, which is neither Greek nor Roman,[104] and from the extended adjective term of «Germany», which was the place where sans-serif typefaces became popular in the 19th to 20th centuries.[105] Early adopters for the term includes Miller & Richard (1863), J. & R. M. Wood (1865), Lothian, Conner, Bruce McKellar. Although the usage is now[when?] rare in the English-speaking world, the term is commonly used in Japan and South Korea; in China they are known by the term heiti (Chinese: 黑體), literally meaning «black type», which is probably derived from the mistranslation of Gothic as blackletter typeface, even though actual blackletter typefaces have serifs.

Recents[edit]

- Lineale, or linear: The term was defined by Maximilien Vox in the VOX-ATypI classification to describe sans-serif types. Later, in British Standards Classification of Typefaces (BS 2961:1967), lineale replaced sans-serif as classification name.

- Simplices: In Jean Alessandrini’s désignations préliminaries (preliminary designations), simplices (plain typefaces) is used to describe sans-serif on the basis that the name ‘lineal’ refers to lines, whereas, in reality, all typefaces are made of lines, including those that are not lineals.[106]

- Swiss: It is used as a synonym to sans-serif, as opposed to roman (serif). The OpenDocument format (ISO/IEC 26300:2006) and Rich Text Format can use it to specify the sans-serif generic typeface («font family») name for the font files used in a document.[107][108][109] Presumably refers to the popularity of sans-serif grotesque and neo-grotesque types in Switzerland.

- Industrial: Used to refer to grotesque and neo-grotesque sans-serifs that are not based on «artistic» principles, as humanist, geometric and decorative designs normally are.[77][110]

Gallery[edit]

This gallery presents images of sans-serif lettering and type across different times and places from early to recent. Particular attention is given to unusual uses and more obscure typefaces, meaning this gallery should not be considered a representative sampling.

-

Dublin 1848, caps-only heading with crossed V-form ‘W’

-

Corset advertisement using multiple grotesque typefaces, United States, 1886

-

Light sans-serif being used for text, Germany, 1914

-

German propaganda poster, 1914

-

Small art-nouveau flourishes on ‘v’ and ‘e’. Ljubljana, 1916.

-

Italic, Dublin, 1916

-

Nearly monoline and stroke-modulated sans; Austrian war bond poster, 1916

-

Broad block capitals. Hungarian film poster, 1918.

-

Monoline sans-serif with art-nouveau influenced tilted ‘e’ and ‘a’. Embedded umlaut at top left for tighter linespacing.

-

Art Deco thick block inline sans-serif capitals, inner details kept very thin. France, 1920s.

-

Artistic sans-serif keeping curves to a minimum (the line ‘O Governo do Estado’), Brazil, 1930

-

Lightly modulated sans-serif lettering on a 1930s poster, pointed stroke endings suggesting a brush

-

Geometric sans-serif capitals, with sharp points on ‘A’ and ‘N’. Australia, 1934.

-

Dwiggins’ Metrolite and Metroblack typefaces, geometric types of the style popular in the 1930s

-

Stencilled lettering apparently based on Futura Black, 1937

-

A 1940s American poster. The curve of the ‘r’ is a common feature in grotesque typefaces, but the ‘single-storey’ ‘a’ is a classic feature of geometric typefaces from the 1920s onwards.

-

1952 Jersey holiday events brochure, using the popular Gill Sans-led British style of the period

-

Swiss-style poster using Helvetica, 1964. Tight spacing characteristic of the period.

-

Ultra-condensed industrial sans-serif in the style of the 1960s; Berlin, 1966

-

Neo-grotesque type, Switzerland, 1972: Helvetica or a close copy. Irregular baseline may be due to using transfers.

-

Tightly-spaced ITC Avant Garde; 1976

-

Governmental poster using Univers, 1980

-

Anti-nuclear poster, 1982

-

1997 film festival poster, Ankara

See also[edit]

- East Asian sans-serif typeface

- Emphasis (typography)

- List of sans serif typefaces

- San Serriffe, an April Fools’ joke by the newspaper The Guardian

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ The original metal type of Akzidenz-Grotesk did not have an oblique; this was added in the 1950s, although many sans-serif obliques of the period are similar.

- ^ Digital publishing expert Florian Hardwig describes the main features of neo-grotesques as being «consistent details and even text colour.»[17]

- ^ In this period and since, some sources have distinguished the nineteenth-century «grotesque/gothic» designs from the «sans-serifs» (those now categorised as humanist and geometric both) of the twentieth, or used some form of classification that emphasises a different between the groups.[28]

- ^ The inscription was destroyed by mistake in 1967, and had to be replicated from historian James Mosley’s photographs.[47][48]

- ^ Mosley’s book on early sans-serifs The Nymph and the Grot is named for the sculpture.[49] The name is a dual reference, also to «grotesque» being coincidentally a term also applied to early sans-serif typefaces, although Mosley suggests that the design does not seem to be a direct source of modern sans-serifs.

- ^ The corporate typeface of the National Trust of the United Kingdom, which manages Stourhead, was loosely designed by Paul Barnes based on the inscription.

- ^ Apparently based on traditions in his field of work, master sign-painter James Callingham writes in his textbook «Sign Writing and Glass Embossing» (1871) that «What one calls San-serif, another describes as grotesque; what is generally known as Egyptian, is some times called Antique, though it is difficult to say why, seeing that the letters so designated do not date farther back than the close of the last century. Egyptian is perhaps as good a term as could be given to the letters bearing that name, the blocks being characteristic of the Egyptian style of architecture. These letters were first used by sign-writers at the close of the last century, and were not introduced in printing till about twenty years later. Sign-writers were content to call them “block letters,” and they are sometimes so-called at the present day; but on their being taken in hand by the type founders, they were appropriately named Egyptian. The credit of having introduced the ordinary square or san-serif letters also belongs to the sign-writer, by whom they were employed half a century before the type founder gave them his attention, which was about the year 1810.»[55][48]

- ^ to Isaac Hawkins Browne in the chapel of Trinity College, Cambridge

- ^ The matrices used to cast the type also survive, although at least some characters were recut slightly later. Historian John A. Lane, who has examined surviving Caslon specimens and the matrices, suggests that the design is actually slightly earlier and may date to around 1812-4, noting that it appears in some undated but apparently earlier specimens.[63]

- ^ News Gothic’s oblique was actually designed later than the original design, although many nineteenth-century sans-serifs are similar.

References[edit]

- ^ «sans serif» in The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th edn., 1992, Vol. 10, p. 421.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford University Press. 2022.

- ^ Childers; Griscti; Leben (January 2013). «25 Systems for Classifying Typography: A Study in Naming Frequency» (PDF). The Parsons Journal for Information Mapping. The Parsons Institute for Information Mapping. V (1). Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ Baines, Phil; Haslam, Andrew (2005), Type and Typography, Laurence King Publishing, p. 51, ISBN 9781856694377, retrieved 23 May 2014

In British Standards Classification of Typefaces (BS 2961:1967), the following are defined:

Grotesque: Lineale typefaces with 19th-century origins. There is some contrast in thickness of strokes. They have squareness of curve, and curling close-set jaws. The R usually has a curled leg and the G is spurred. The ends of the curved strokes are usually oblique. Examples include the Stephenson Blake Grotesques, Condensed Sans No. 7, Monotype Headline Bold.

Neo-grotesque: Lineale typefaces derived from the grotesque. They have less stroke contrast and are more regular in design. The jaws are more open than in the true grotesque and the g is often open-tailed. The ends of the curved strokes are usually horizontal. Examples include Edel/Wotan, Univers, Helvetica.

Humanist: Lineale typefaces based on the proportions of inscriptional Roman capitals and Humanist or Garalde lower-case, rather than on early grotesques. They have some stroke contrast, with two-storey a and g. Examples include Optima, Gill Sans, Pascal.

Geometric: Lineale typefaces constructed on simple geometric shapes, circle or rectangle. Usually monoline, and often with single-storey a. Examples include Futura, Erbar, Eurostile. - ^ a b Shinn, Nick (2003). «The Face of Uniformity» (PDF). Graphic Exchange. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Coles, Stephen. «Helvetica alternatives». FontFeed (archived). Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c Berry, John. «A Neo-Grotesque Heritage». Adobe Systems. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ a b Specimens of type, borders, ornaments, brass rules and cuts, etc. : catalogue of printing machinery and materials, wood goods, etc. American Type Founders Company. 1897. p. 340. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ «Italic Gothic». Fonts in Use. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ Hoefler & Frere-Jones. «Knockout». Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Hoefler & Frere-Jones. «Knockout sizes». Hoefler & Frere-Jones.

- ^ «Knockout styles». Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Lippa, Domenic (14 September 2013). «10 favourite fonts». The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ «Grotesque Sans». Monotype. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ Greta, P (21 August 2017). «What Are Grotesque Fonts? History, Inspiration and Examples». Creative Market Blog. Creative Market. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ Meggs 2011, pp. 376–377.

- ^ @hardwig (16 June 2019). «The mid-20th century saw a reappraisal of these classic sans serif forms. Fueled by modernist ideas, they were rethought and redrawn, now with consistent details and even text color. Transferred into systematic families of numerous weights and widths, the neo-grotesque became an essential ingredient of the International Typographic Style» (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Adi Kusrianto. Pengantar Tipografi. Elex Media Komputindo. p. 66. ISBN 978-979-27-8132-8.

- ^ Lagerkvist, Love (18 May 2017). «American Football». Fonts In Use. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

Imago [is] a relatively obscure neo-grotesk released by Berthold in the early ’80s.

- ^ Slimbach, Robert. «Using Acumin». Acumin microsite. Adobe Systems. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ Twardoch; Slimbach; Sousa; Slye (2007). Arno Pro (PDF). San Jose: Adobe Systems. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Coles, Stephen. «New Additions: November 2015». Identifont. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ «Fontshop lists: Neo-grotesque». FontShop. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Ulrich, Ferdinand. «A short intro to the geometric sans». FontShop. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ Ulrich, Ferdinand. «Types of their time – A short history of the geometric sans». FontShop. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Kupferschmid, Indra. «On Erbar and Early Geometric Sans Serifs». CJ Type. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ Meggs 2011, pp. 339–340.

- ^ a b Day, Kenneth (1956). The Typography of Press Advertisement. pp. 86–8.

- ^ Kupferschmid, Indra (6 January 2012). «True Type of the Bauhaus». Fonts in Use. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Tselentis, Jason (28 August 2017). «Typodermic’s Raymond Larabie Talks Type, Technology & Science Fiction». How. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Kupferschmid, Indra. «Some type genres explained». kupferschrift (blog). Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ a b Tracy 1986, pp. 86–90.

- ^ Nash, John. «In Defence of the Roman Letter» (PDF). Journal of the Edward Johnston Foundation. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Blackwell, written by Lewis (2004). 20th-century type (Rev. ed.). London: Laurence King. p. 201. ISBN 9781856693516.

- ^ Lawson 1990, pp. 326–330.

- ^ Berry, John D. (22 July 2002). «Not Your Father’s Sans Serif». Creative Pro. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ Berry, John D. (5 August 2002). «The Human Side of Sans Serif». Creative Pro. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ Coles, Stephen. «Questioning Gill Sans». Typographica. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ Kupferschmid, Indra. «Gill Sans Alternatives». Kupferschrift. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ Calvert, Margaret. «New Transport». A2-TYPE. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ Coles, Stephen. «Identifont blog Feb 15». Identifont. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d Mosley, James (6 January 2007), The Nymph and the Grot, an update, archived from the original on 10 June 2014, retrieved 10 June 2014

- ^ «Perkins School for the Blind». Perkins School for the Blind. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Johnston, Alastair. «Robert Grabhorn Collection on the History of Printing». San Francisco Public Library. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Mosley, James. «Comments on Typophile thread — «Unborn: sans serif lower case in the 19th century»«. Typophile (archived). Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Le Pogam, Pierre-Yves (2005). De la » Cité de Dieu » au » Palais du Pape «. Rome: École française. p. 375. ISBN 978-2728307296.

- ^ Barnes, Paul. «James Mosley: A Life in Objects». Eye. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mosley 1999, p. 1–19.

- ^ a b c d Mosley 1999.

- ^ John L Walters (2 September 2013). Fifty Typefaces That Changed the World: Design Museum Fifty. Octopus. pp. 1913–5. ISBN 978-1-84091-649-2.

- ^ Gell, William (1810). The Itinerary of Greece. London. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Mosley, James. «The sanserif: the search for examples». Mnémosyne: Base documentaire de l’ésad d’Amiens. ESAD Amiens. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ Alexander Nesbitt (1998). The History and Technique of Lettering. Courier Corporation. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-486-40281-9.

- ^ L. Y. (1805). «To the Editor of the European Magazine». European Magazine. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Callingham, James (1871). Sign Writing and Glass Embossing. pp. 54–55.

- ^ L. Parramore (13 October 2008). Reading the Sphinx: Ancient Egypt in Nineteenth-Century Literary Culture. Springer. pp. 22–3. ISBN 978-0-230-61570-0.

- ^ Jason Thompson (30 April 2015). Wonderful Things: A History of Egyptology 1: From Antiquity to 1881. The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 251–2. ISBN 978-977-416-599-3.

- ^ Southey, Robert (1808). Letters from England: by Don Manual Alvarez Espriella. D. & G. Bruce, print. pp. 274–5.

- ^ Farington, Joseph; Greig, James (1924). The Farington Diary, Volume III, 1804-1806. London: Hutchinson & Co. p. 109. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Tracy, Walter (2003). Letters of credit : a view of type design. Boston: David R. Godine. ISBN 9781567922400.

- ^ Tam, Keith (2002). Calligraphic tendencies in the development of sanserif types in the twentieth century (PDF). Reading: University of Reading (MA thesis). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ Simon Loxley (12 June 2006). Type: The Secret History of Letters. I.B.Tauris. pp. 36–8. ISBN 978-1-84511-028-4.

- ^ «The Song of the Sans Serif». The Centre for Printing History and Culture. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ a b Mosley, James; Shinn, Nick. «Two Lines English Egyptian (comments on forum)». Typophile. Archived from the original on 14 March 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

[T]he Figgins ‘Sans-serif’ types (so called) are well worth looking at. In fact it might be said to be that with these types the Figgins typefoundry brought the design into typography, since the original Caslon Egyptian appeared only briefly in a specimen and has never been seen in commercial use. One size of the Figgins Sans-serif appears in a specimen dated 1828 (the unique known copy is in the University Library, Amsterdam).…It is a self-confident design, which in the larger sizes abandons the monoline structure of the Caslon letter for a thick-thin modulation which would remain a standard model through the 19th century, and can still be seen in the ATF Franklin Gothic. Note that there is no lower-case. That would come, after 1830, with the innovative condensed ‘Grotesque’ of the Thorowgood foundry, which provided a model for type that would get large sizes into the lines of posters. It gave an alternative name to the design, and both the new features – the condensed proportions and the addition of lower-case – broke the link with Roman inscriptional capitals…But the antiquarian associations of the design were still there, at least in the smaller sizes, as the specimen of the Pearl size (four and three quarters points) of Figgins’s type shows. It uses the text of the Latin inscription prepared for the rebuilt London Bridge, which was opened on 1 August 1831.

- ^ Lane, John A.; Lommen, Mathieu; de Zoete, Johan (1998). Dutch Typefounders’ Specimens from the Library of the KVB and other collections in the Amsterdam University Library with histories of the firms represented. De Graaf. p. 15. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

Figgins 1828 [is] one of two known copies, but with the first known appearance of the world’s second sans-serif type, not in the other copy

- ^ a b Barnes, Paul; Schwartz, Christian. «Original Sans Collection: Read the Story». Commercial Classics. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Ryan, David (2001). Letter Perfect: The Art of Modernist Typography, 1896-1953. Pomegranate. ISBN 978-0-7649-1615-1.